Psychiatrists must seek to make the most of the opportunity offered by the much overdue increase in Foundation Programme training posts in psychiatry,Footnote a while continuing to enhance the teaching of medical undergraduate students. We need to create good doctors who are highly professional, good communicators and sympathetic to psychosocial needs of all patients. We also need to improve recruitment to our own specialty.

Medical students prefer to learn general skills rather than specialised ones – this is a ‘strategic’ outlook that cuts their workload (Reference Kneale, Armstrong, Thompson and BrownKneale 1997). For a busy foundation year doctor, this problem is further magnified by the added pressure and responsibility of working and the steep learning curve that comes with it. Students’/trainees’ views must be balanced with the necessity to teach the fundamentals and principles of psychiatry, otherwise the care of the mentally ill will be compromised through lack of knowledge (Reference Davies and McGuireDavies 2000; Reference Oakley and OyebodeOakley 2008). Therefore, psychiatrists have a role in teaching all undergraduates generic skills, such as psychosocial aspects of patient care and the doctor–patient relationship, with emphasis on professionalism and good communication. However, as well as this, psychiatrists should appeal to and nurture the interests of psychiatrists of the future by including core psychiatric skills/knowledge in our teaching (Reference GhodseGhodse 2004).

Recruitment

There is a crisis in recruitment in psychiatry. Psychiatry is the least popular clinical specialty among medical students, in both the UK and most countries worldwide (Reference Rajagopal, Rehill and GodfreyRajagopal 2004). Sixth-form students are often interested in a future career in psychiatry, but something changes during the medical school years (Reference Maidment, Livingston and KatonaMaidment 2003). Only 3–4% of medical graduates express an interest in psychiatry as a career at the end of training – half the number required to fill consultant posts (in the UK, recruitment from overseas masks poor local recruitment) (Reference Brockington and MumfordBrockington 2002; Reference Lambert, Goldacre and TurnerLambert 2003). However, the great variation in the numbers entering psychiatry from different medical schools shows that good teaching can influence recruitment (Reference Lambert, Goldacre and TurnerLambert 2003; Reference GhodseGhodse 2004; Reference Paddock, Farooq and SarkarPaddock 2013).

Attitudes to psychiatry significantly improve during teaching programmes (Reference Baxter, Singh and StandenBaxter 2001; Reference Glynn, Reilly and AvalosGlynn 2006), but interest typically wains thereafter: one study reported a fall in interest from 10–11% to 3–4% within 1 year (Reference Tharyan, John and TharyanTharyan 2008). Students’ exposure to non-psychiatric specialties in the final year and their focus on what they think they will need immediately after qualifying are likely reasons (Reference Baxter, Singh and StandenBaxter 2001). Fortunately, psychiatry has started to be included in the foundation years for new doctors, thus increasing exposure (Reference CareyCarey 2000), and with the recent steps to increase the number of these posts, we have a wonderful opportunity to rectify the problems in recruitment. Quality of teaching is an important ‘modifiable’ influence on recruitment, especially for those with neutral views beforehand (Reference Niedermier, Bornstein and BrandemihlNiedermier 2006). Positive attitudes are promoted by direct patient contact, encouragement from consultants and seeing patients respond well to treatment (Reference McParland, Noble and LivingstoneMcParland 2003; Reference Oakley and OyebodeOakley 2008). If more psychiatry could also be taught in the final undergraduate year, then recruitment might improve further (Reference Baxter, Singh and StandenBaxter 2001). However, the creation of the extra foundation posts in psychiatry is even better.

Yet, there is more to recruitment than just teaching. Unfortunately, criticism or ‘bashing’Footnote b of psychiatry by other specialties is common (Reference Ajaz, David and BrownAjaz 2016; Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker 2016), which puts medical students off particular specialties (especially psychiatry), thus affecting recruitment (Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker 2016). One of us (S. N. S.) has been ridiculed by other clinicians for being a psychiatrist: ‘Who would want to deal with “psychos” by choice?’ They have assumed that he entered psychiatry as a ‘last resort’, having failed in other medical fields, or ‘to have an easy life as it doesn't take much hard work or brain-power’. Psychiatrists are often perceived as unscientific, confused thinkers, emotionally unstable and ineffective (Reference Dubugras, Mari and dos SantosDubugras 2007; Reference Ajaz, David and BrownAjaz 2016). They are portrayed negatively in the media (Reference Dubugras, Mari and dos SantosDubugras 2007). All this has an impact on recruitment by influencing students’ perceptions of psychiatry as a career. It is seen as too slow moving with few clear results/improvements, and ultimately psychiatrists have low status due to lack of respect shown by other specialties (Reference Brockington and MumfordBrockington 2002; Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker 2016).

A recent survey examining factors influencing career choices among a group of psychiatric trainees and medical students pointed to the powerful role (both positive and negative) of the consultant and role modelling (Reference Paddock, Farooq and SarkarPaddock 2013). Reference Shah, Brown, Eagles, Brown and EaglesShah et al (2011) also investigated factors influencing career choice among foundation trainees (Box 1). They found that the psychiatric rotation in the Foundation Programme could improve recruitment by giving trainees work experience in a field they might not otherwise have considered as a career. This in turn could increase the proportion who decided on psychiatry as their top choice of specialty.

BOX 1 What influences foundation trainees considering psychiatry as a career?

Positive factors

-

1 Experiences as medical students – finding psychiatric patients interesting, developing an aptitude for the specialty, undergraduate teaching

-

Influence of seniors – role modelling, encouragement, morale

-

Aspects of the work environment – patient contact, general pace of the specialty, team work

Negative factors

-

1 Perceived poor prognosis of psychiatric patients

-

Perceived unscientific basis of psychiatry

-

Negative comments made by other specialties

Stereotyping and stigma

Challenging negative stereotypes about psychiatry is a huge motivator for us to create ‘ambassadors of psychiatry’ through our teaching. Stereotyping is an efficient way of structuring knowledge – it is an effective strategy that cuts the cognitive workload, thus reducing uncertainty related to any novel stimulus (Reference TownsendTownsend 1979). It therefore appeals to ‘strategic’ students (to whom we return later in this article).

Stigma in psychiatry is encountered in negative views not only about psychiatrists, but also about their patients. Some have suggested that ‘the rejecting voices of others may bring greater disadvantage than the primary condition itself’ (Reference Thornicroft, Rose and KassamThornicroft 2007). Unfortunately, stigma is very common and it has an immense impact on patients and a negative influence on recruitment. Stigma is not explicitly addressed in undergraduate teaching, yet we have a duty to tackle it. The problem is magnified by the difficulty of assessing stigma.

Reference ByrneByrne (2000) points out that stigma (like beauty) is in the eye of the beholder. Many people get their information about mental illness from the mass media. Psychiatric disorders, their treatments and those who provide them are all subject to overwhelmingly negative portrayals in the print and broadcast media (Reference EdneyEdney 2004; Reference Wahl and FriedmanWahl 2004, Reference Wahl, Hanrahan and Karl2007). Many studies have found a definite connection between negative media portrayals of mental illness and the public's negative attitudes towards people with mental health problems (Reference Coverdale, Nairn and ClaasenCoverdale 2002; Reference OlsteadOlstead, 2002). Reference WahlWahl (1995) found that this negative media influence also extended to healthcare professionals. A Mind survey found that half of the respondents said that the media coverage had a negative effect on their own mental health (Reference Baker and MacphersonBaker 2000), but more worryingly, Mind's 1996 survey on stigma (Reference Read and BakerRead 1996) revealed that 50% of people with mental illnesses felt discriminated against by medical services, and this theme has been commented on again recently (Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker 2016). The impact of these stigmatising attitudes was further highlighted by Reference Thornicroft, Rose and KassamThornicroft (2007) and Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker (2016) . If parity of esteem between physical and mental health is lacking within medicine, then how can we expect it to exist outside? The stigmatising of psychiatrists and the mentally ill stimulates stigma in society and could discourage patients with mental health problems from seeking help for both mental and physical ill health (Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker 2016). Doctors with mental illness have high suicide rates due to denial and delays in seeking treatment because of the shame of stigma (Reference GrayGray 2002). Unfortunately, although attitudes appear to have improved in some areas more recently, there has not been enough improvement overall (Reference MindMind 2013; Reference Baker, Wessely and OpenshawBaker 2016).

Stigmatising attitudes develop in early childhood, so they are difficult to change. Increased knowledge and contact with mentally ill people challenge negative stereotypes, but one negative image can override the cumulative effects of many positive experiences (Reference ByrneByrne 2000). However, as Byrne stated, the starting point in tackling stigma is education, and there are a number of ways in which we can reduce stigma in our teaching of students and trainees. We should acknowledge and address stigma as a separate and important issue in its own right. Patients and carers should be involved in training healthcare professionals (Reference Walters, Raven and RosenthalWalters 2007). The more direct contact that students have with both patients and carers, the better. Patients’ narratives ‘normalise’ mental illness and allow patients to be seen as individuals. Students eventually learn that anyone can develop mental illness if there is enough stress, and this lowers the ‘them and us’ attitude (Reference GrayGray 2002). Home visits allow students to try to understand how a patient lives and behaves in their own environment, culture and context (Reference Walters, Raven and RosenthalWalters 2007; Reference Dogra, Anderson and EdwardsDogra 2008). Role-play in which students take on the part of patients can be a powerful experience that builds empathy and reduces stigma (Reference McNaughton, Ravitz and WadellMcNaughton 2008).

Reference SalterSalter (2003) recognised that the media are less interested in content, but rather in whether the information is interesting and sustains attention. So should we be playing the media at their own game, by making teaching interesting, but with positive images of mental illness and psychiatry (Reference EdneyEdney 2004)? In light of the growing use of social media and the internet, should we explicitly acknowledge the existence of stigma and prejudice in the media and use clips (both positive and negative) to encourage healthy discussion and debate in a safe environment? Should we not move with the times and make our teaching more relevant?

Ideal teaching practice

Role modelling, particularly of senior clinicians, is an important factor that determines career choice and attitudes, so we need to use this to our advantage (Reference Shah, Brown, Eagles, Brown and EaglesShah 2011; Reference Paddock, Farooq and SarkarPaddock 2013). We need to demonstrate not only what to do and how to do it, but also the right attitude. Ideal teaching practice should therefore counteract negative experiences, while building on positives. We need to be enthusiastic about teaching and try to create a relaxed, positive atmosphere with open questions and discussion based on interesting examples. Students might be matched with specific patients, to promote experiential learning. A ‘thinking aloud’ approach can aid decision-making and professionalism (Reference SkånérSkånér 2005; Reference Cross, Moore and MorrisCross 2006). Giving individualised feedback and also asking for feedback to adapt one's own teaching would continually enhance quality (Reference Sluijsmans, Brand-Gruwel and van MerrienboerSluijsmans 2003). A personal narrative explaining what it is like to live the life of a psychiatrist might be an effective way of improving recruitment, as the student or trainee could picture working in the profession themselves (Reference Hashmi, Talley and ParsaikHashmi 2014; Reference Berkhout, Helmich and TeunissenBerkhout 2015).

The essence of teaching ought to be to try to make students/trainees feel important (Fig. 1). Foster an environment conducive to learning by not causing students to feel that they are a burden, that their learning is interfering with patient care by intruding on privacy or encroaching on a clinician's time. Students/trainees need to be given achievable responsibilities to enable them to feel that they are contributing to patient care, and thus feel accountable and part of a team. Making juniors feel important motivates them to learn more than just how to pass assessments, by promoting deeper learning and professionalism.

FIG 1 Examples of how to make juniors feel important – a strategy for students and the first few weeks of foundation trainee placements (see online data supplement for references).

Assessments – limitations and solutions

Assessment motivates students to learn, but what should the real aim of teaching be – helping students to pass exams or enabling them to be better doctors/psychiatrists (to be competent and professional) (Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006)? If we are merely aiming for higher pass rates, we are limited by the validity of assessment (i.e. whether a test predicts that someone will become a good doctor). There is often a balance between validity and reliability (Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003) and also between what is ideal and what is feasible (Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012; Reference Hodges, Hollenberg and McNaughtonHodges 2014). Direct observation of students seeing real patients is valid, but not always practical, hence the use of simulated patients – actors trained to portray signs and symptoms (Reference Schuwirth and van der VleutenSchuwirth 2003; Reference DaveDave 2012). However, standardisation of simulation (Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003; Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006) can still cause problems.

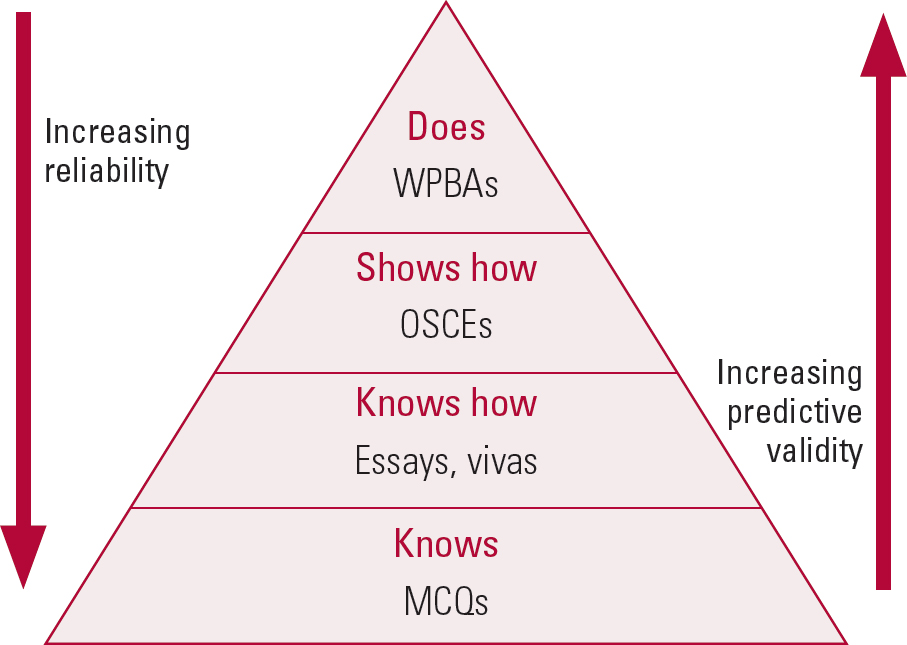

Miller's pyramid (Reference MillerMiller 1990) is a well-known framework for assessing clinical competence (Fig. 2). Reference NormanNorman (2005) has challenged the simplicity of this framework, and various authors have debated its usefulness: any single assessment (point measurement) implies a compromise on quality criteria, since one method can assess only a part of the pyramid (Reference NormanNorman 2005; Reference HodgesHodges 2006; Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012). Furthermore, performance is highly context dependent (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005), so any attempt at standardisation will only trivialise the assessment (Reference Norman, Van der Vleuten and De GraaffNorman 1991). A single method of assessment cannot cover all aspects of competencies of the layers of Miller's pyramid, so we need a blend of methods, including professional judgement (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005).

FIG 2 Miller's pyramid amended to show that single assessments often result in a trade-off between reliability and validity. MCQs, multiple choice questions; OSCEs, objective structured clinical examinations; WPBAs, workplace-based assessments.

A competency is the ability to handle a complex professional task by integrating the relevant cognitive, psychomotor and affective skills (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005). It involves knowledge, skills, problem-solving and attitudes (Reference Frank and DanoffFrank 2007). In medicine, it has been defined as ‘the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individuals and communities being served’ (Reference Epstein and HundertEpstein 2002). Too much emphasis on competence-as-knowledge risks creating ‘hidden incompetence’ – knowledge-smart doctors who have poor interpersonal and technical skills (Reference MillerMiller 1990; Reference HodgesHodges 2006).

The psychometric discourse on assessing clinical competence converts human behaviours into numbers (Reference HodgesHodges 2013). There has been a tendency to break down competence into smaller units or stable, measurable ‘traits’ that are assessed separately, on an assumption that the sum of these parts can equate to competent performance in an integrated whole (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005; Reference HodgesHodges 2013), but many have criticised this as ‘over-objectification’, ‘reductionism’ and ‘trivialisation’ (Reference HodgesHodges 2006; Reference Zibrowski, Singh and GoldszmidtZibrowski 2009; Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012). Reliability is relevant at the level of individual assessment tools, but not when heterogeneous sources of information are combined (Reference HodgesHodges 2013). Should we then be going beyond the psychometric discourse and single assessments of competence? Figure 3 outlines strategies that might be used to optimise assessment.

FIG 3 Strategies to optimise assessment (see online data supplement for references).

OSCEs, OSLERs and CASCs

Objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) are more reliable and valid than traditional examinations (Reference Walters, Osborn and RavenWalters 2005; Reference Hodges, Hollenberg and McNaughtonHodges 2014). OSCE stations involve a simulated patient and an examiner, are mainly 7–10 minutes long and scoring is based on a task-specific checklist and a global rating scale (Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006). However, this still does not resolve the problem of poor correlation between undergraduate competence and postgraduate performance (Reference Rethans, Norcini and Barón-MaldonadoRethans 2002). This could be because the range of attributes that might be called on in clinical practice is much wider than can be assessed in OSCEs, therefore resulting in poor interrater reliability (Reference Mazor, Zanetti and AlperMazor 2007). Going through a long checklist in a short time is an artificial and high-pressure situation, not akin to the day-to-day assessments a psychiatrist usually undertakes. Reference NormanNorman (2005) described ‘shotgun behaviour induced by checklists’, leading to hidden incompetence and inappropriate behaviour (Reference HodgesHodges 2006). Longer stations (e.g. as in the objective structured long examination record or OSLER) might overcome the shortcomings of OSCEs by providing more time for reflection and explanation of complex cases, and they may be more akin to real life (Reference GleesonGleeson 1997; Reference Taghva, Bolhari and BahadorTaghva 2008; Reference Hodges, Hollenberg and McNaughtonHodges 2014).

The clinical assessment of skills and competencies (CASC) examination was introduced into postgraduate psychiatric assessment in 2008 (Reference ThompsonThompson 2009) and it is more context-rich (Reference Schuwirth and van der VleutenSchuwirth 2004) than the OSCE. A variety of settings and tools would give a fuller picture, but assessment is limited by cost and resources (Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012). However, does simply learning to pass exams mean that the learning of professionalism is overlooked?

WPBAs and teaching professionalism

In the past (when many of us were undergraduates), more emphasis was put on the lower two levels of Miller's pyramid (‘knows’ and ‘knows how’). OSCEs now target the third level (‘shows how’), but the development of less standardised, though still reliable, methods of practice-based assessment has led to calls to move assessment back into the real world of the workplace (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005). Workplace-based assessments (WPBAs) for doctors target the highest level (‘does’) by collecting information in everyday practice, thus improving validity. This method has filtered down to undergraduates (Reference Rethans, Norcini and Barón-MaldonadoRethans 2002; Reference Norcini, Blank and DuffyNorcini 2003, Reference Norcini and Burch2007; Reference Wilkinson and FramptonWilkinson 2004; Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006) and the mini clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX) is an example for foundation trainees (Reference Ram, Grol and RethansRam 1999; Reference Norcini, Blank and DuffyNorcini 2003).

We need to create a smooth transition from student life to professional life, by preparing our students for life as doctors. They need to know the relevance of factual information rather than becoming bogged down in its large volume (Reference Kneale, Armstrong, Thompson and BrownKneale 1997). They need consistent role models. Students need to realise what it is actually like to be a psychiatrist by shadowing more junior doctors (e.g. those on call). However, it is not always feasible to shadow junior doctors because of unpredictable clinical settings. In these situations, the powerful influence of consultants as role models can be utilised more often (Reference Shah, Brown, Eagles, Brown and EaglesShah 2011; Reference Paddock, Farooq and SarkarPaddock 2013).

Professionalism can be defined as one's professional identity as a doctor (Reference Roberts, Warner and HammondRoberts 2005). It involves ‘subordination of one's own interests to those of the patient’, i.e. humanistic values (Reference Roberts, Warner and HammondRoberts 2005). Professionalism (ethics and communication skills) helps doctors make decisions, especially in psychiatry (General Medical Council 2013; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2009, 2014). Psychiatry does not have simple tests of physical parameters for diagnosis. Psychiatrists need skills to engage a patient enough to obtain an accurate history – otherwise even vast knowledge will not allow us to make the right decisions. Certain issues of professionalism are particularly important to psychiatry – detaining/treating patients involuntarily, therapeutic alliances, boundaries, confidentiality, capacity, consent, working with the multidisciplinary team, interagency liaison (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2009, 2014; American Psychiatric Association 2013). Some of these can be easily taught/assessed, but some elements are more difficult.

Teaching professionalism varies owing to the complexity of its components and the limitations of assessment methods. It is learnt largely through an informal process of modelling (Reference JoubertJoubert 2006), social constructivism and collaborative learning (Reference Plaice, Heard and MossPlaice 2002; Reference JoubertJoubert 2006; Reference Mazor, Zanetti and AlperMazor 2007), but more explicit teaching is needed. One possibility is to use simulated patients (Reference McNaughton, Ravitz and WadellMcNaughton 2008). They can help to standardise assessment, yet add variety to the students’ learning experience, by enhancing communication skills in difficult situations, for example involving risk, intrusion and confidentiality (Reference McNaughton, Ravitz and WadellMcNaughton 2008; Reference DaveDave 2012). They provide safety in the face of an unpredictable learning environment. Observation is by facilitators/peers, but can be videotaped for self-reflection (Reference Ram, Grol and RethansRam 1999). Self-reflection and feedback from simulated patients and observers are important for effectiveness. Another possibility is problem-based learning. This method uses a clinical problem to stimulate self-directed learning, which is then discussed in a group, thus enhancing collaborative learning – important in professionalism (Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003; Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006).

The end point in assessments is often seen without an explanation of the route to get there. ‘Thinking aloud’ to the student in everyday clinical scenarios (Reference SkånérSkånér 2005; Reference Cross, Moore and MorrisCross 2006) might enable them to understand thought processes via a ‘decision-making tree’. Feedback is an essential component of assessment. Feedback should be holistic and not just factual, i.e. it should comment on all aspects of professionalism, such as liaising with staff, appearance, dress, punctuality, attitude, legible handwriting and appearing interested, enthusiastic and caring.

Role-modelling acts as a blueprint or gold standard for comparison (Reference Plaice, Heard and MossPlaice 2002; Reference JoubertJoubert 2006). Students and juniors should be encouraged to actively observe and discuss a clinician's professional behaviour and interactions with both patients and staff, and then to apply what they have learnt. Direct observation of students (e.g. as they explain diagnosis/prognosis/management) enables individualised feedback on professionalism (Reference Davies and McGuireDavies 2000; Reference GhodseGhodse 2004; Reference El-Sayeh, Budd and WallerEl-Sayeh 2006) and ought to form the bulk of the initial part of any placement. This, in conjunction with modelling, instils confidence and enhances performance for the rest of the placement, and the gains are ultimately far greater than the initial investment of time and effort.

Subjective judgement in assessment

Experienced clinicians rely on a gestalt impression, i.e. pattern recognition and subjective judgement, for clinical diagnosis (Reference HodgesHodges 2013; Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007). So is there a role for holistic supervisor (expert) judgements in student assessment, in the form of subjective global impressions over a specific time frame (Reference Bogo, Regehr and PowerBogo 2004; Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007; Reference GinsburgGinsburg 2011)? Diagnostic, contextual or interpersonal variables might be part of the authentic variability of real practice settings (Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007). Competence is not fixed/stable, but contextual, constructed and changeable and also at least partly subjective and collective (Reference HodgesHodges 2013). There have been calls for movement away from the purely psychometric model, with the re-examination of the value of subjectivity and judgement (Reference HodgesHodges 2006, Reference Hodges2013; Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007; Reference Gingerich, Regehr and EvaGingerich 2011).

Reliance on subjective information and judgement is seen by many as a ‘soft option’, biased or unfair (Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012; Reference HodgesHodges 2013) and therefore less reliable. Various authors have discussed ways of increasing the reliability of subjective judgements, for example by increasing the testing time (Reference Wass, Van der Vleuten and ShatzerWass 2001; Reference HodgesHodges 2013), appropriate sampling of raters and simulated patients (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005); increasing the number of judgements and ensuring the independence and diversity (heterogeneity) of raters and sources of information (Reference Eva and HodgesEva 2012; Reference HodgesHodges 2013); and improving training and performance standards for raters (Reference Malini Reddy and AndradeMalini Reddy 2010). However, trying to achieve complete objectivity will trivialise the assessment process (Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012).

Assessment of general professional competencies

General professional competencies include an ability to work in a team, metacognitive skills, professional behaviour and the ability to reflect/self-appraise (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005; Reference Hodges, Ginsburg and CruessHodges 2011). Multisource (‘360-degree’) assessments (Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007) can provide insight into trainees’ work habits, capacity for teamwork and interpersonal sensitivity (Reference Violato, Marini and ToewsViolato 1997; Reference Dannefer, Henson and BiererDannefer 2005), and it is most effective when it includes narrative comments (as well as statistical data) from credible sources, coupled with constructive feedback and mentoring (Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007). An example of how this might apply in practice is to undertake a ‘friends and family test’ to give a global/gestalt impression – i.e. ‘Would you send your friend or family member to this (future) doctor?’ If multiple impressions are collected from a wide range of raters (e.g. from the multidisciplinary team, patients and peers), integrated (‘jury model’) and a narrative feedback is added, this provides robust and valid information (Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007). Coupled with feedback and mentoring, this will stimulate learning and development (Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007; Reference Driessen, Overeem, Tartwijk van, Dornan, Mann and ScherpbierDriessen 2010; Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012).

Assessment of competencies needs to be increasingly based on qualitative, descriptive and narrative information, but the best way forward is to combine this with quantitative, numerical data (Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005). Competencies may be integrated for methods that are not as standardised (e.g. oral exams, mini-CEX). Multiple sources of information from various methods may be used to construct an overall judgement by triangulating information across these sources (Reference Epstein and HundertEpstein 2002; Reference HardenHarden 2002; Reference Van der Vleuten and SchuwirthVan der Vleuten 2005). Moreover, learning is facilitated when tasks are integrated (Reference Van MerrienboerVan Merrienboer 1997), and contextualisation (Reference HodgesHodges 2006) (vignette- and problem-based learning) enhances validity (Reference Jozefowicz, Koeppen and CaseJozefowic 2002). Portfolios and log books are increasingly used and they include evidence/documentation of, and self-reflection about, specific areas of a trainee's competence (Reference SnaddenSnadden 1999; Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003; Reference Driessen, van Tartwijk and van der VleutenDriessen 2007) and demonstrate professional development (Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007).

In the past, more emphasis was put on summative assessment (e.g. end-of-year exams), which favours strategic learners (Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003). In contrast, formative assessment is a more continuous and ‘low-stakes’ assessment that is more likely to be linked with qualitative assessment and regular feedback to guide learner development. Formative assessment encourages deeper learning by providing continuous/regular feedback, but it is time-consuming. Timely feedback from assessment enhances learning and identifies students’ strengths and weaknesses (Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003).

Summary

Assessment should use a diversity of methods, multisource feedback (self, peer, patient, carer, staff) and continuous assessment. It should be combined with regular and meaningful feedback to help students and trainees to learn and improve. Some elements of professionalism are not captured in exams, but we still have a duty to assess and teach them, especially in psychiatry. With the Foundation Programme, we need to ensure that workplace-based assessments are valid and meaningful, formative and coupled with feedback.

Strategic learners

Assessment plays a dominant role in student learning, but it can have both intended and unintended consequences. For example, end-of-year exams, which rely on recall of factual information, can lead to cramming and only surface-level learning (Reference Newble and JaegerNewble 1983; Reference EpsteinEpstein 2007).

Strategic learners are common in medicine. They are motivated (externally) by exams/assessments and might overlook professional values. Given the sheer volume of factual information to process in order to become a doctor, students feel overloaded and their learning becomes strategic. This approach often continues into the post-graduate years. To take more interest or study a topic in depth might mean failing something else, so tight is the balance. Reference Kneale, Armstrong, Thompson and BrownKneale (1997) attributed this growing problem to the increasing anonymity that students feel as medical schools become ever larger. They attend only if they know it will be part of their assessment – i.e. if attendance registers are taken or if a senior figure is present. They prefer exams (i.e. surface learning for short-term recall) rather than continuous assessments (Reference Kneale, Armstrong, Thompson and BrownKneale 1997) and study only for the parts of the course that are assessed (Reference Wass, Van der Vleuten and ShatzerWass 2001). Cutting corners results in a lack of meaningful understanding or a change in attitude due to cognitive restructuring. Prejudices regarding psychiatric professionals and patients therefore remain.

The apprenticeship model

The self-centred ‘classroom’ attitude to learning in order to pass exams or assessments can fail the newly qualified doctor: suddenly they have to know the answers – they cannot hide behind the ‘student’ label. In clinical practice the emphasis is on patient care and teamwork, so should we be assessing teamwork and collaboration (Committee on Quality of Health Care in America 2001; Reference Lingard, Hodges and LingardLingard 2012)? A ‘true apprenticeship model’ (living and working like a junior member of the field) is not part of undergraduate medical culture. Nursing students get a salary, feel valued/responsible, develop a sense of duty to the team and to patients, thus reducing selfish attitudes and promoting a smooth transition from student to professional: we must aim to achieve a similar model for medical students. We now have a chance to get this right for foundation trainees, who will indeed have more responsibilities than they had as students, and we need to foster their sense of belonging.

The role of assessment and feedback

If assessment is to drive learning, it should be formative, it should produce information that is both educational and meaningful to the learner, and it should be coupled with formative feedback in order to motivate students/trainees to engage in deeper learning (Reference Hattie and TimperleyHattie 2007; Reference ShuteShute 2008; Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012). Qualitative feedback (narrative information) adds to the meaningfulness of the information (Reference Sargeant, Armson and CheslukSargeant 2010).

We should not simply surrender to strategic learners by emphasising relevance to exams. We ought to go beyond this by considering Kolb's experiential learning cycle (Reference KolbKolb 1984; Reference Cross, Moore and MorrisCross 2006). A learner in a new situation processes their direct experience and new information by self-reflection, comparison with prior experiences/learning and feedback from others. A logical theory is then established that can be applied to further experiences by active experimentation and the cycle is repeated. Thus, reflection is used for self-direction – i.e. to plan new learning tasks or goals (Reference HodgesHodges 2006; Reference Van Merrienboer and SluijsmansVan Merrienboer 2009; Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012). Reflection is difficult, so clinical teachers should facilitate this integration by coaching or mentoring (supervision) (Reference HodgesHodges 2006; Reference Van der Vleuten, Schuwirth and DriessenVan der Vleuten 2012). This promotes progressive levels of deeper learning. Improving intrinsic motivation is a key factor in overcoming strategic learning and thus promoting deeper learning.

Are we strategic teachers?

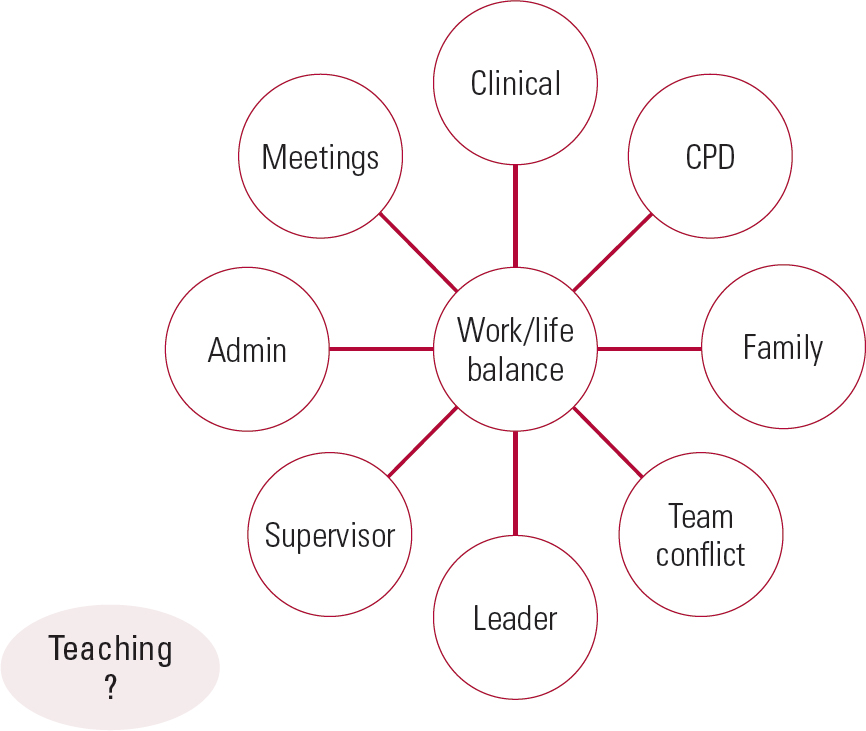

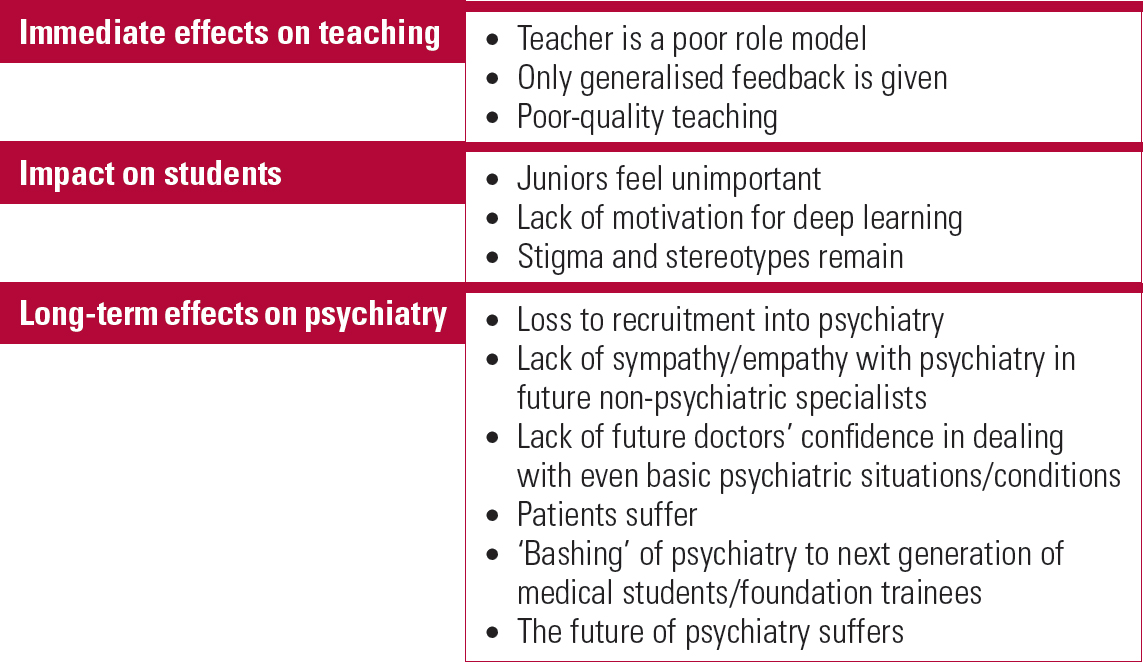

We can't help thinking that many of us might in fact be ‘strategic teachers’, such is the juggling act we find ourselves in. We face barriers to teaching, such as lack of time, resources, funding and recognition (Fig. 4). Are we in essence merely ‘good enough’ teachers, as opposed to good teachers? If so, what example is this setting our students and what impact is it having (Fig. 5)?

FIG 4 Strategic teachers – how do we fit teaching in? CPD, continuing professional development.

FIG 5 Potential negative effects of strategic teaching.

Improving the motivation to learn

Motivation can be extrinsic or intrinsic. Strategic learners are motivated extrinsically (e.g. by assessment). Intrinsic motivation is mediated by student factors (e.g. previous experience, desire to achieve and curiosity to learn) and enhanced by maximising the learning environment, relevance (e.g. immediate needs/future career) and good teachers (Reference MarkertMarkert 2001).

Maslow's hierarchy of needs indicates that students’/trainees’ non-clinical needs must be met first in order to increase their motivation to learn (Reference MaslowMaslow 1943). In essence, we can achieve this by making them feel important (i.e. promoting feelings of trust, belonging and self-esteem), as well as attending to their basic physiological needs (e.g. physical safety and comfort). However, this can be difficult owing to lack of facilities in the community (e.g. designated space and IT resources) and wards that can be chaotic and dangerous (Reference Parsell and BlighParsell 2001). Therefore, ground rules must be clear and involve mutual respect and trust. Regular dialogue to ensure that a positive learning environment is being maintained is essential. Pastoral issues must not be neglected (Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006; Reference El-Sayeh, Budd and WallerEl-Sayeh 2006).

Self-regulated learning

Improving motivation is linked to promotion of self-regulated learning (SRL). SRL is a complex and highly individual process (Reference Sitzmann and ElySitzmann 2011; Reference Zumbrunn, Tadlock and RobertsZumbrunn 2011), which is essential for life-long learning as a healthcare professional (Reference SandarsSandars 2009). Factors known to stimulate SRL are social support, the opportunity for guided and independent practice, with the support of feedback and stimulation of reflective practice, and the opportunity to make errors and learn from them (Reference Sitzmann and ElySitzmann 2011; Reference Berkhout, Helmich and TeunissenBerkhout 2015). It is also influenced by the student's specific goals (Reference ZimmermanZimmerman 2008; Reference Berkhout, Helmich and TeunissenBerkhout 2015). It should be maximised by offering students more tailored learning opportunities and support based on recognising each learner's needs, personal goals and narrative (Reference SandarsSandars 2009; Reference Berkhout, Helmich and TeunissenBerkhout 2015). Perhaps this could be aligned to future career aims (Reference Hashmi, Talley and ParsaikHashmi 2014). If students cannot relate to external goals set by the curriculum, it will deter SRL (Reference Berkhout, Helmich and TeunissenBerkhout 2015). Therefore, as Reference Wass, Van der Vleuten and ShatzerWass et al (2001) note, ‘assessment is the most appropriate engine on which to harness the curriculum’. Formative assessments provide benchmarks to orient the learner and reinforce their intrinsic motivation to learn (Reference FriedmanFriedman 2000). However, infrequent summative exams (often at the end of a training block) do not give opportunities to link the results with feedback or inform students’ learning needs (Reference Schuwirth and van der VleutenSchuwirth 2006).

Making the most of the learning environment

The uniqueness of the psychiatric setting should be used to its best advantage (Reference Parsell and BlighParsell 2001; Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006). Working within a multidisciplinary team and involving patients and carers/relatives enables students to understand different points of view. This is essential to becoming a psychiatrist (Reference Davies and McGuireDavies 2000). Arranging a mix between general versus specialised and in-patient versus community settings will give students the broadest view of psychiatry with which to make an informed career choice or develop sympathetic attitudes to the field (Reference GhodseGhodse 2004). Home visits are an effective way of reducing stigma towards patients (Reference Walters, Raven and RosenthalWalters 2007). Ward rounds can be made more useful by highlighting teaching points and giving students tasks to keep them active. Smaller groups enhance collaborative learning and team work (Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003; Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006), and one-to-one teaching and feedback are tailored, adaptable and instil enthusiasm as well as enabling modelling (Reference Parsell and BlighParsell 2001; Reference Sweet, Hutly and TaylorSweet 2003; Reference Cantillon, Hutchinson and WoodCantillon 2006; Reference Cross, Moore and MorrisCross 2006). ‘Hot-seating’, allowing students to see patients alone in clinic before seeing them together, enables experiential learning (Reference KolbKolb 1984; Reference Kneale, Armstrong, Thompson and BrownKneale 1997). However, this is not always feasible, due to time constraints and shortage of rooms.

Their role in service provision might mean that foundation doctors have less flexibility to visit other services for a broader experience of psychiatry. Yet, it is essential to take a longer-term approach and to allow flexibility for a varied experience, as this ought to improve recruitment to, or at least a better understanding of, our field.

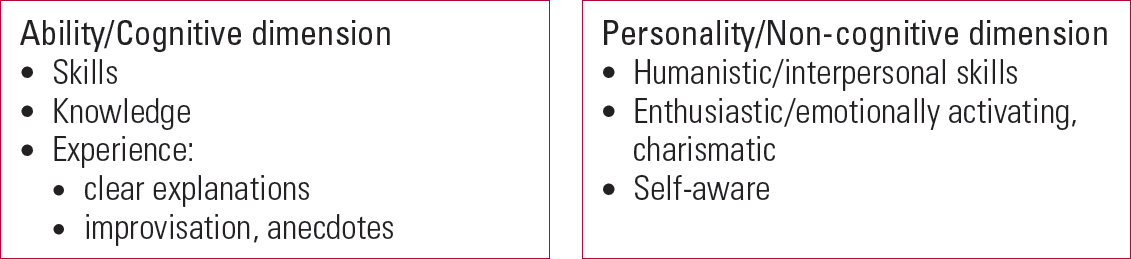

Teachers’ characteristics influence students’ learning and motivation. We were inspired by those who were enthusiastic and caring. Good teachers create an atmosphere in which students are motivated by intrinsic drives – identifying with and then modelling enthusiasm (Reference MarkertMarkert 2001). The literature points out that the characteristics of good clinical teachers broadly fall into two dimensions: Reference Beishuizen, Hof and van PuttenBeishuizen (2001) identifies them as the ability and personality dimensions, whereas Reference Sutkin, Wagner and HarrisSutkin (2008) describes them in terms of cognitive and non-cognitive dimensions (Fig. 6). Although skills and characteristics in the personality/non-cognitive dimension are difficult to teach, they need more emphasis, as they dominate the literature on good medical teaching.

FIG 6 Characteristics of good teachers in two dimensions (Reference Beishuizen, Hof and van PuttenBeishuizen 2001; Reference MarkertMarkert 2001; Reference Sutkin, Wagner and HarrisSutkin 2008).

Conclusions

With the recently proposed increase in the number of foundation posts in psychiatry in the UK, we have an excellent opportunity to address problems in psychiatry such as stigma, recruitment and holistic care. However, we need to attend to the basics and turn to the literature on teaching, medical education and psychiatry in order to do this.

We have to motivate medical students and trainee doctors with good teaching and a variety of methods to promote active learning, thus overcoming the culture of strategic learning. As teachers, we need to be knowledgeable, but humanistic qualities need more emphasis. We must also give and receive regular feedback, adapt to students’ needs, maximise the learning environment and make students feel important. This will improve deeper learning, enhance professionalism and reduce prejudice against psychiatry. It might even improve recruitment to the field.

More specifically, we should promote positive attitudes towards psychiatry in all students and juniors, even if they do not want to become psychiatrists. This will help to address stigma against psychiatrists and also against our patients. We must remember that students with neutral views are the most likely to have their attitudes modified by good teaching (Reference Baxter, Singh and StandenBaxter 2001). We should try to identify students who show enthusiasm for psychiatry and should try to maintain their interest until they make their career choices. This could be achieved by mentoring them over time, involving them in research projects and audits, setting up psychiatry interest groups and campaigning for more exposure to psychiatry in the final undergraduate year.

Although the validity of assessment methods is increasing (and can be improved further by triangulation of methods), they still do not accurately predict who will become a good doctor. Should we design assessments to better suit our needs in trying to create more holistic doctors or to improve recruitment into psychiatry? Should this be achieved by using assessment to improve learning and linking it more closely to the curriculum? Is this an issue to be tackled by curriculum designers? In the meantime, we need to teach students to go beyond just passing exams or assessments. Most importantly, we should look at ourselves and the examples we set. We, as influential individuals, have a huge bearing on the future of psychiatry. We must look beyond our own short-term interest and goals and consider the bigger picture.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The short-term effect of current undergraduate teaching programmes in psychiatry tends to be:

-

a increased negative attitudes to psychiatry

-

b enhanced neutral views to psychiatry

-

c increased recruitment to psychiatry

-

d significantly improved attitudes to psychiatry

-

e not much change in attitudes to psychiatry.

-

-

2 In undergraduates with neutral attitudes to psychiatry, a modifiable factor most likely to improve recruitment is:

-

a the quality of teaching

-

b the variety of the learning environment

-

c exposure to psychiatric patients

-

d multidisciplinary teaching rather than teaching by psychiatrists

-

e being taught by junior doctors.

-

-

3 The typical rate of decay of initial improvement in attitudes to psychiatry after an undergraduate teaching programme is reported to be:

-

a a twofold reduction over 3 years

-

b a threefold reduction over 1 year

-

c a fivefold reduction over 5 years

-

d very little decay over 3 months

-

e negligible change in the first year.

-

-

4 The phenomenon described by Kneale as creating a barrier against deeper learning and conveying messages beyond exams/assessment is:

-

a experiential learning

-

b the hierarchy of needs – e.g. self-actualisation

-

c stigma against psychiatry

-

d strategic learning

-

e ‘bashing’ or belittling of psychiatry by other specialties.

-

-

5 According to the educational literature, students’ intrinsic motivation to learn (i.e. achieve deeper learning) is most likely to be improved by their teachers’:

-

a experience

-

b humanistic/interpersonal skills

-

c sound, subject-specific knowledge base

-

d use of improvisation

-

e structured approach to teaching.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | d | 2 | a | 3 | b | 4 | d | 5 | b |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.