Seaweeds have been featured in the diets of Asian culture since ancient times(Reference Chapman and Chapman1). The nutritional and physiological effects of seaweeds have received much attention during the past decades. Seaweeds are rich in polysaccharides, minerals, vitamins and dietary fibre(Reference Ruperez2–Reference Lahaye5). Antioxidant and antimutagenic effects of dietary seaweeds have been reported in vitro (Reference Kwon and Nam6–Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Nakamura8) and in vivo studies(Reference Guo, Xu and Zhang9–Reference Yamamoto and Maruyama11). Polysaccharides(Reference Kwon and Nam6, Reference Guo, Xu and Zhang9, Reference Zhang, Li and Zhou12, Reference Zhao, Zhang and Qi13), proteins(Reference Hwang, Kwon and Kim14), antioxidants (e.g. ascorbate, glutathione and carotenoids)(Reference Burritt, Larkindale and Hurd15, Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Yano16), polyphenols(Reference Yuan and Walsh7) and extracts(Reference Yuan and Walsh7, Reference Yuan, Carrington and Walsh17) of seaweeds have been reported to have antioxidant, antitumour and chemoprotective activities.

In particular, the potential benefits of seaweed consumption for breast cancer treatment have been traced back to the ancient Egyptian ‘Ebers Papyrus’, which mentioned that seaweed was used to treat breast cancer(Reference Teas18). The putative protective effect of seaweed on breast cancer is in accord with the relatively low breast cancer rates in Japan(Reference Kamangar, Dores and Anderson19), where seaweed-rich diets are consumed and with the increasing breast cancer rates in Japanese women who emigrate(Reference LeMarchand, Kolonel and Nomura20) or consume a Western style diet(Reference Minami, Takano and Okuno21). Animal studies(Reference Yamamoto, Maruyama and Moriguchi10, Reference Maruyama, Watanabe and Yamamoto22, Reference Funahashi, Imai and Mase23) and in vitro studies(Reference Funahashi, Imai and Mase23–Reference Funahashi, Imai and Tanaka25) demonstrated the anticarcinogenic effects of seaweeds against mammary carcinogenesis. Iodine as well as other components of seaweeds have been suggested to act as antioxidants(Reference Winkler, Griebenow and Wonisch26) and induce apoptosis in human breast cancer cell lines(Reference Funahashi, Imai and Mase23). In an ecological study, the regions where iodine intake was low had higher breast cancer mortality rates(Reference Serra Majem, Tresserras and Canela27). However, few epidemiological studies have reported on the effects of seaweed consumption on breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in Korean women, with an age-standardised incidence rate of 31·1 per 100 000 persons in 2002(Reference Shin, Jung and Won28). Even though the incidence rate of breast cancer is lower than in Western countries(Reference Kamangar, Dores and Anderson19), this rate has been increasing in Korea(29). Seaweed is frequently consumed on a daily basis in a traditional Korean diet. According to the third Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (2005)(30), the daily intake of seaweed was 8·5 g/d (fresh+dry mass). Gim (Porphyra sp.), miyeok (Undaria pinnatifida; ‘wakame’ in Japan) and dashima (Laminaria sp.; ‘konbu’ in Japan) are common seaweeds, which constitute over 95 % of seaweed consumption in Korea(30). However, dashima (Laminaria sp.) is usually used for making broth (i.e. soaked in boiling water then removed), so that the actual intake is not substantial. Gim is a Korean style edible seaweed in the genus Porphyra. Gim (Porphyra sp.) looks like ‘nori’ in Japan, but sheets of gim are thinner than nori sheets. Seasoned roasted gim prepared with sesame oil and salts is the most common type of gim and it is consumed as a side dish. Gim is also used as wrappings, seasonings and condiments. Miyeok (U. pinnatifida) is the second most commonly consumed seaweed in Korea and is usually consumed as the form of soup or a side dish.

Despite high consumption of seaweeds in Asian countries, the association between seaweed consumption and breast cancer risk has been determined in limited epidemiological studies(Reference Key, Sharp and Appleby31). Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the association between the consumption of seaweed, specifically gim (Porphyra sp.) and miyeok (U. pinnatifida), and the risk of breast cancer in a case–control study among Korean women.

Material and methods

Cases and controls

Cases and controls were recruited from October 2004 to June 2006 at Samsung Hospital of Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul, South Korea. All participants aged 30–65 years were examined by mammography to detect any possibility of breast cancer. Cases had histologically confirmed breast cancer. Subjects having any history of cancer (five cases) or having an estimated total energy intake < 2092 kJ/d ( < 500 kcal/d) or>16 736 kJ/d (>4000 kcal/d; sixteen cases and thirteen controls) were excluded from the study. Controls were patients visiting one of the dentistry, orthopedic surgery, general surgery, ophthalmology, dermatology, rehabilitation, obstetrics and gynecology or family medicine clinics within the same hospital. Cases and controls were matched by their age (within 2 years) and menopausal status (362 pairs). The present study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving the human subjects were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Hospital of Sungkyunkwan University. Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Data collection

Cases and controls were interviewed by trained interviewers with a questionnaire addressing patients' general characteristics, menstrual and reproductive history, family history of breast cancer, smoking and drinking habits, intake of multivitamins and the average time spent on exercising. Dietary data were collected by the quantitative FFQ, which were modified from the validated FFQ(Reference Kim, Lee and Ahn32), with visual aids such as food photographs and models for item-specific units. The FFQ was composed of 121 food items which included roasted gim (Porphyra sp.) and miyeok soup (U. pinnatifida). The gim used as wrappings, seasonings and condiments was not asked in the questionnaire. The amounts of foods consumed were asked in open-ended questions with standard units such as cup, bowl and piece etc. Subjects were asked by trained interviewers to recall their usual intake of the 121 food items over a period of 12 months beginning from 3 years before the time of the interview(Reference Willett33). All frequencies were standardised into ‘times/day’ by using the conversion factors 4·3 weeks/month and 30·4 d/month. Daily food intake was calculated with standardised frequency per day and the amount of food consumed. Detailed information on data collection has been presented in previous publications elsewhere(Reference Hong, Kim and Nam34, Reference Kim, Kim and Nam35).

The intake of gim and miyeok was calculated using standardised frequency per day and one portion per unit. One sheet of dried, roasted gim was 2 g in dry mass and one portion of miyeok soup was composed of 36 g of miyeok in fresh mass. Nutrient intakes adjusted for total energy intake by the residual method were used in all the analyses to avoid bias due to the simple relationship of nutrient intake with total energy intake.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Cases and their matched controls were compared by a paired t test for continuous variables and by the McNemar test for categorical variables. The quintiles of daily gim intake, consumption frequency of gim and daily miyeok intake were applied to the analyses. Since the variation of miyeok consumption frequency was not large, it could not be classified into quintile groups, thus, the quartiles of miyeok consumption frequency were applied to the analyses. In addition, the menopausal status-specific quintiles were used in the subgroup analysis of menopausal status. The general linear model and the Cochran–Mantel–Haenzel analysis were used to determine potential confounders among the controls. Conditional logistic regression analysis was applied to obtain the OR and corresponding 95 % CI. Three different models were applied to examine the associations of seaweed intake with the risk of breast cancer. Any variable was not adjusted in the first model. Variables which were significantly different between the cases and controls and showed significant linear trends across quintiles or quartiles of seaweed intake except dietary variables were adjusted in the second model. Dietary variables were additionally adjusted in the third model. The trend tests were conducted by treating the median values of each quintile as continuous variables in a multivariate model after inputting the median value of the controls into each dietary intake group. Daily intakes of gim and miyeok and the average consumption frequencies of gim and miyeok were also introduced as continuous variables, and the units were expressed in increments of 1 g/d and once per week, respectively.

Results

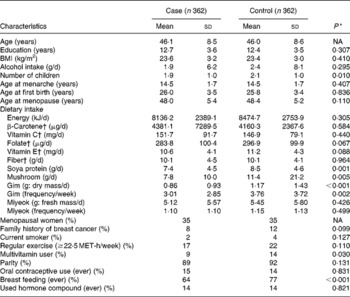

The characteristics of the breast cancer cases and the matched controls are presented in Table 1. Compared with the controls, the cases had lower proportions of multivitamin users and breast feeding and had fewer children. The cases consumed lower amounts of soya protein, mushrooms and gim (Porphyra sp.) than the controls. The frequency of gim intake was also lower in the cases than in the controls. However, the intake of miyeok and the average consumption frequency of miyeok did not differ between the cases and the controls.

Table 1 General characteristics of the study subjects with or without breast cancer

(Mean values and standard deviations or proportions)

NA, not applicable; MET, metabolic equivalent.

* Two-sided; paired t test for continuous variables and McNemar test for categorical variables.

† All nutrients were total energy-adjusted by a residual method after log transformation.

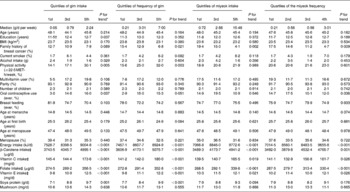

To determine any potential confounding factors, the distributions of selected characteristics of the control subjects were examined by using the quintiles of gim intake, frequency of gim intake and miyeok intake, as well as the quartiles of frequency of miyeok intake (Table 2). Education, physical activity and oral contraceptive use increased across the quintiles of gim intake in the controls. The proportion with a family history of breast cancer decreased across the quintiles of the frequency of gim intake, miyeok intake and the frequency of miyeok intake. The proportion of exercise increased across the quintiles of the gim intake frequency. The intakes of energy, β-carotene, vitamin C, folate and vitamin E increased across the quintiles of gim intake, the frequency of gim intake, miyeok intake and the frequency of miyeok intake. The intake of soya protein increased across the quintiles of gim intake and the frequency of gim intake. The variables showing significant trends according to the consumptions of gim and miyeok in Table 2 are adjusted as potential confounding factors in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 2 Selected characteristics of control subjects according to the quintiles of gim intake and miyeok intake

MET, metabolic equivalent.

* P values for the trends were determined by the general linear model for continuous variables and by the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for categorical variables.

† All variables except median and age were adjusted for age and values are expressed as a least square mean or percent.

‡ All nutrient consumptions were adjusted for total energy intake.

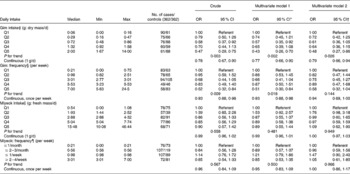

Table 3 Risk of breast cancer according to gim and miyeok consumption

(OR and 95 % CI; median, min and max values)

Min, Minimum; max, maximum; Q, quintile.

* All multivariate adjusted OR models included multivitamin supplement (yes/no), number of children and breast feeding (yes/no).

† In addition to covariates in multivariate model 1, dietary factors (quintiles of energy, β-carotene, vitamin C, folate, vitamin E, soya protein and mushrooms) were adjusted in multivariate model 2.

‡ The model for gim intake was additionally adjusted for education (years), exercise (yes/no) and oral contraceptive use (yes/no).

§ The model for miyeok intake was additionally adjusted for the family history of breast cancer (yes/no).

∥ The model for frequency of gim was additionally adjusted for family history of breast cancer (yes/no) and exercise (yes/no).

¶ The model for frequency of miyeok was additionally adjusted for family history of breast cancer (yes/no).

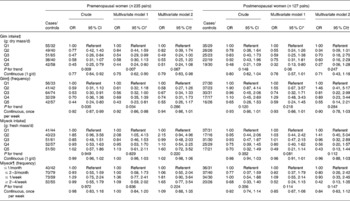

Table 4 Risk of breast cancer according to gim and miyeok consumption in premenopausal and postmenopausal women

(OR and 95 % CI)

Q, quintile.

* All multivariate adjusted OR models included multivitamin supplement (yes/no), number of children and breast feeding (yes/no).

† In addition to covariates in multivariate model 1, dietary factors (quintiles of energy as well as the intake of β-carotene, vitamin C, folate, vitamin E, soya protein and mushrooms) were adjusted in multivariate model 2.

‡ The model for gim intake was additionally adjusted for education (years), exercise (yes/no), oral contraceptive use (yes/no).

§ The model for miyeok intake was additionally adjusted for family history of breast cancer (yes/no).

∥ The model for frequency of gim was additionally adjusted for family history of breast cancer (yes/no) and exercise (yes/no).

¶ The model for frequency of miyeok was additionally adjusted for family history of breast cancer (yes/no).

The associations between seaweed and the risk of breast cancer are given in Table 3. A significant inverse association was found between the breast cancer risk and gim intake (OR, 0·47; 95 % CI, 0·29, 0·75 for the last quintile in comparison with the lowest quintile; P for trend, 0·003). The inverse association between breast cancer risk and gim intake was significant after adjusting for potential confounders such as multivitamin supplement, number of children, breast feeding, education, exercise and oral contraceptive use (OR, 0·43; 95 % CI, 0·26, 0·70 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·002). After an additional adjustment for the dietary potential confounders (quintiles of energy as well as consumption of β-carotene, vitamin C, folate, vitamin E, soya protein and mushrooms), the inverse association between breast cancer risk and gim intake remained (OR, 0·48; 95 % CI, 0·27, 0·86 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·026). In the analyses with continuous data, gim intake showed inverse associations with breast cancer risk in the three models. A consumption frequency of gim was also inversely associated with breast cancer risk (OR, 0·52; 95 % CI, 0·32, 0·84 for the last quintile; P for trend = 0·009). The inverse association of the consumption frequency of gim with the breast cancer risk remained after adjusting for potential confounders including a multivitamin supplement use, number of children, breast feeding, a family history of breast cancer and exercise (OR, 0·51; 95 % CI, 0·30, 0·84 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·018). However, after the additional adjustment for dietary potential confounders (quintiles of energy as well as intake of β-carotene, vitamin C, folate, vitamin E, soya protein and mushrooms), the inverse association between breast cancer risk and consumption frequency of gim was no longer significant (OR, 0·58; 95 % CI, 0·32, 1·04 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·144). In the analyses with the continuous data, the significant inverse associations between breast cancer risk and the consumption frequency of gim were found in the crude OR (OR, 0·93; 95 % CI, 0·88, 0·98) and in the multivariate model 1 (OR, 0·93; 95 % CI, 0·88, 0·98). Miyeok intake and the frequency of miyeok intake did not show any significant associations with the risk of breast cancer.

To evaluate if seaweed intake affects breast cancer risk differently according to menopausal status, the stratified associations were examined as in Table 4. Among premenopausal women, gim intake and the consumption frequency of gim were inversely associated with breast cancer risk (OR, 0·45; 95 % CI, 0·25, 0·79 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·009; OR, 0·44; 95 % CI, 0·24, 0·80 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·035). Additional adjustment for potential confounders except for dietary factors did not change these significant inverse associations between breast cancer risk and gim intake and the consumption frequency of gim (OR, 0·44; 95 % CI, 0·24, 0·80 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·007; OR, 0·43; 95 % CI, 0·23, 0·81 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·034). However, after additionally adjusting for dietary confounders, these inverse associations were no longer significant (OR, 0·51; 95 % CI, 0·24, 1·08 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·067; OR, 0·55; 95 % CI, 0·26, 1·17 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·286). In the analyses with continuous data, gim intake showed dose–response inverse associations with breast cancer risk in the three models among premenopausal women. Postmenopausal women showed similar inverse associations between breast cancer risk and gim intake, but only the multivariate model 1 (OR, 0·32; 95 % CI, 0·13, 0·80 for the last quintile; P for trend, 0·061) was statistically significant. NS associations were found between the risk of breast cancer and miyeok intake and the frequency of miyeok intake.

Discussion

Little evidence is available on the associations between seaweed consumption and breast cancer in epidemiologic studies(Reference Key, Sharp and Appleby31), even though the anticancer effects of seaweeds have been reported in vitro (Reference Kwon and Nam6–Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Nakamura8) and in vivo assays(Reference Guo, Xu and Zhang9–Reference Yamamoto and Maruyama11). In the present study, the inverse association between gim (Porphyra sp.) intake and breast cancer risk was found, but NS association was found between miyeok (U. pinnatifida) intake and breast cancer risk. These results suggest that the high intake of gim may reduce the risk of breast cancer.

Seaweeds have been frequently consumed in Asia for centuries(Reference Chapman and Chapman1). In Western countries, the consumption of seaweed products has increased during the past few decades(Reference Mabeau and Fleurence3). Korean people have consumed seaweeds on a daily basis. Gim is a dried seaweed; one sheet of gim is approximately 2 g. Koreans have eaten mostly dried and roasted gim. Miyeok is usually sold in the form of the dried type, but it is consumed after it is soaked in water. According to the third Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey (2005)(30), the average consumption frequencies of Korean adults for gim and miyeok were 4·5 times/week and 1·3 times/week, respectively. The average consumption frequency of gim for the cases (3·0 times/week) was lower than that of the controls (3·8 times/week) and that of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2005(30). The average intake of gim in the cases (0·86 g/d) was also lower than the controls (1·17 g/d). The highest quintile group of gim consumed one sheet of gim per d. The consumption frequencies of miyeok for the controls (1·1 time/week) and cases (1·1 time/week) were similar to the frequency of miyeok in Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2005(30). Controls showed higher consumptions of soya protein and mushrooms than the cases. The associations of soya protein and mushrooms with the risk of breast cancer were reported elsewhere(Reference Hong, Kim and Nam34, Reference Kim, Kim and Nam35).

Seaweeds are rich in proteins, polysaccharides, minerals and vitamins(Reference Ruperez2–Reference Lahaye5). The contents of protein for dried gim ranged from 29·0 to 38·6 %, while the protein content for dried miyeok was 13·5 %(36). High dietary fibre content attributes to the high content of indigestible polysaccharides in the algal cell wall. Seaweeds contained higher amounts of both macrominerals (Na, K, Ca, Mg) and trace elements (Fe, Zn, Mn, Cu) than those from edible land plants(Reference Ruperez2). Vitamins A, B12, and C, β-carotene, pantothenate, folate, riboflavin and niacin in algae are higher than in fruits and vegetables from regular land cultivars(Reference Kanazawa37, Reference Ishii, Susuki and Koyanagi38).

The amount of gim intake showed an inverse dose–response association with the risk of breast cancer in our present study. To investigate whether seaweeds differently affect the risk of breast cancer by menopause, a stratification analysis was performed according to menopausal status. The inverse associations of gim intake with breast cancer risk did not differ between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Since the number of postmenopausal women was smaller than the number of premenopausal women, the associations of gim intake with breast cancer risk were not statistically significant among postmenopausal women, but the associations were consistent with premenopausal women. These results suggest that gim has a protective effect on breast cancer risk and this effect may not differ between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. In a prospective study by Key et al. (Reference Key, Sharp and Appleby31), the consumption frequency of sea vegetables was not associated with the risk of breast cancer (relative risk, 0·89; 95 % CI, 0·69, 1·16 for ≥ 5/week in comparison with ≤ 1/week), but the diet information was from mail surveys and they asked about consumption frequencies of nineteen foods and drinks. In addition, the frequencies of sea vegetables were ‘once or less per week’, ‘two to four times per week’ and ‘five or more times per week’. Thus, in order to determine the association between sea vegetables and breast cancer risk, other kinds of valid dietary assessment methods needed to be introduced.

The antitumour activity of Porphyra sp. has been studied in vitro (Reference Kwon and Nam6, Reference Guo, Xu and Zhang9, Reference Zhao, Zhang and Qi13, Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Yano16) and in vivo (Reference Yamamoto, Maruyama and Moriguchi10, Reference Yamada, Yamada and Fukuda4, Reference Zhang, Li and Zhou12) assays. Polysaccharides produced by the red algae Porphyra sp. such as porphyran and Porphyra yezoensis polysaccharide have been reported to have immunoregulatory, antioxidant and antitumour activities(Reference Kwon and Nam6, Reference Guo, Xu and Zhang9, Reference Zhang, Li and Zhou12, Reference Zhao, Zhang and Qi13). Porphyran inhibited cancer cell growth by decreasing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in AGS gastric cancer cell lines(Reference Kwon and Nam6). Porphyra yezoensis polysaccharide had a protective effect on chemical toxicity, which may be related to free radical scavenging, thus increasing superoxide dismutase activity in mice(Reference Guo, Xu and Zhang9). A protein from the red algae also had chemoprotective effects on acetaminophen-induced liver injury in rats(Reference Hwang, Kwon and Kim14). In addition, extracts from red algae were reported to have antioxidant and antiproliferative activities, which were positively associated with the total polyphenol contents(Reference Yuan and Walsh7), carotenoids(Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Yano16) and chlorophyll(Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Yano16).

Miyeok intake did not show any significant associations with the risk of breast cancer in the present study, a finding which may be due to the low consumption frequency and low variation in miyeok intake among the subjects. However, U. pinnatifida (miyeok) has been reported to suppress mammary tumour growth in rats(Reference Funahashi, Imai and Tanaka25), while fucoidan and fucoxanthin from U. pinnatifida has antitumour(Reference Maruyama, Tamauchi and Iizuka39, Reference Hosokawa, Kudo and Maeda40) and antioxidant activities(Reference Kang, Kim and Kwon41). Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate the relationship between miyeok intake and breast cancer risk in other research settings including areas with a large variation of miyeok intake.

The chemopreventive effects of seaweed on breast cancer have been studied with regard to the relationship between iodine and breast cancer. Seaweeds contain high quantities of iodine in several chemical forms. Even though gim (Porphyra) contains less iodine than dashima (Laminaria) and miyeok (Undaria)(Reference Nagataki42), gim (Porphyra) is also a major dietary source of iodine among the Koreans. A significant positive association was found between the region where iodine intake was low and breast cancer mortality rates in Spain(Reference Serra Majem, Tresserras and Canela27). Tissue iodine levels in the tissue of breast cancer patients were lower than in normal tissues or in benign breast tumours(Reference Kilbane, Ajjan and Weetman43). Iodine acts as an antioxidant and antiproliferative agent, which contributes to the integrity of the normal mammary gland(Reference Eskin, Grotkowski and Connolly44). The addition of seaweeds (Laminaria, Porphyra tenera and wakame: miyeok) to the diet and iodine supplement showed a suppressive effect on the development and size of both benign and cancer neoplasias in animal studies(Reference Yamamoto, Maruyama and Moriguchi10, Reference Funahashi, Imai and Tanaka25, Reference Teas, Harbison and Gelman45, Reference Garcia-Solis, Alfaro and Anguiano46).

Taken together, these results indicate that the protective effect of gim on the risk of breast cancer may be attributed to the antioxidant and antitumour activities of gim components such as polysaccharides, protein, polyphenol, carotenoids(Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Yano16), chlorophyll(Reference Okai, Higashi-Okai and Yano16) and iodine, etc.

Despite the benefits of seaweeds in human health, seaweeds may contain trace and ultra-trace elements with human toxicological potential. The mean contents of arsenic, Pb, Cd, and Hg in Porphyra sp. that were produced in Korea, Japan and Italy were assessed as harmless(Reference Dawczynski, Schafer and Leiterer47, Reference Caliceti, Argese and Sfriso48). However, arsenosugars detected in Porphyra seaweed were metabolised to dimethylarsinic acid in human bodies that is more toxic than arsenosugars(Reference Wei, Li and Zhang49). Moreover, brown seaweeds are known as primary accumulators for arsenic(Reference Dawczynski, Schafer and Leiterer47, Reference Caliceti, Argese and Sfriso48, Reference Almela, Algora and Benito50). Thus, the heavy metal contamination of seaweed should be controlled and considered to protect consumers from potential health risks.

To date, this is the first epidemiologic study to determine the direct association of the consumptions of gim and miyeok with the risk of breast cancer. Nevertheless, limitations of the study need to be considered when interpreting the findings. The present study was a hospital-based case–control study, thus, there is a restriction in generalising the results to the general population(Reference Breslow and Day51). One of the potential biases in a case–control study is that cases can change their diet after the diagnosis and treatment of a disease(Reference Breslow and Day51). However, in the present study, all the cases were interviewed before diagnosis or within one week after diagnosis so that dietary changes for cases or differential recall biases are not substantial. The selection of an appropriate control group may be problematic(Reference Breslow and Day51). Although the cases and controls were recruited from the same hospital, the diets of those who participated in the study may differ from those who did not participate. Another limitation is that the FFQ used in the present study asked the intakes of roasted gim and miyeok soup, which are the most frequently consumed forms of gim and miyeok in Korea, so that gim that was consumed as a condiment and miyeok that was consumed as a side dish were not tracked in the questionnaire. Moreover, besides gim and miyeok, other seaweeds such as pare (Enteromorpha compressa) and dashima (Laminaria) are frequently consumed in certain areas of Korea. Thus, to elucidate the associations of seaweed with the risk of breast cancer, detailed questionnaires for estimating seaweed consumption are needed.

In conclusion, a high intake of gim was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer among Korean women. These results suggest that gim may reduce the risk of breast cancer. Further studies are necessary to examine these findings in other large-sized epidemiological studies.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Korea Ministry of Science and Technology (grant no. M10418020002-08N1802-00 210). M. K. K. designed and supervised the execution of the study and Y. J. Y. performed the data analyses and wrote manuscript with S.-J. N. In addition, G. K. contributed to the data preparation. All the authors participated in the interpretation of the results and in the editing of the manuscript. None of the authors had a personal or financial conflict of interest.