INTRODUCTION

Extremist rhetoric and political violence is on the rise across Western democracies (Kalmoe and Mason Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022; Mudde Reference Mudde2019), and one result of these trends is that elected politicians increasingly face harassment in both online and offline spaces. But, the extent to which they are at risk of harm is arguably uneven. Certainly, violence against elected representatives generates an additional set of challenges to an already visible—and, arguably, vulnerable—position.

Findings from recent studies overwhelmingly demonstrate that politicians face meaningful levels of physical and psychological violence, comparable to or even exceeding levels reported by members of the general workforce (e.g., Bjørgo and Silkoset Reference Bjørgo and Silkoset2017; Bjørgo et al. Reference Bjørgo, Jupskås, Thomassen and Strype2022; Every-Palmer, Barry-Walsh, and Pathé Reference Every-Palmer, Barry-Walsh and Pathé2015; James et al. Reference James, Farnham, Sukhwal, Jones, Carlisle and Henley2017; Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2024; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Herrick, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2019). Furthermore, officeholders with experiences of violence are found to be more likely than their counterparts to consider exiting political office (Håkansson Reference Håkansson and Lajevardi2024; Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019), and many experience psychological problems, such as sleep difficulty and anxiety, following attacks (Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019; James et al. Reference James, Sukhwal, Farnham, Evans, Barrie, Taylor and Wilson2016). Across the globe, scholarship is finding a gendered dimension in the type and extent of harassment that politicians face, with women politicians being particularly vulnerable to some of the most damaging forms of aggression (Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020; Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018; Bjarnegård and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2023; Collignon and Rüdig Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Krook and Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2020; Mechkova and Wilson Reference Mechkova and Wilson2021; Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan Reference Rheault, Rayment and Musulan2019; Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Herrick, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2019).

As Western societies diversify, and racial minorities and immigrants are increasingly recruited and elected to political office, two significant questions arise: Do these individuals face higher levels of political violence compared to others? And does this violence disproportionately drive them out of political office? Some research has evaluated how individuals with multiple intersecting identities have been harassed, and has found that at least in online spaces, Muslim and Jewish women politicians are routinely exposed to sexist and racist rhetoric (Kuperberg Reference Kuperberg2021; Salehi et al. Reference Salehi, Pakzad, Lajevardi and Asad2023). But, surprisingly little attention has been paid to violence against politicians with minoritized backgrounds, and how their experiences compare to members of the majority group. Given the immense efforts it takes to recruit minority candidates—whether they be religious, racial, ethnic, or immigrant minorities (Black Reference Black2011; Juenke and Shah Reference Juenke and Shah2016; Mügge Reference Mügge2016), and given that members of these groups still remain underrepresented in politics across a number of Western countries (e.g., Auer, Portmann, and Tichelbaecker Reference Auer, Portmann and Tichelbaecker2023; Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Nyman and Vernby2021; Fraga, Juenke, and Shah Reference Fraga, Juenke and Shah2020; Phillips Reference Phillips2021), it remains critical to understand to what degree minoritized politicians also experience violent encounters once they assume elected office and the consequences thereof.

We make theoretical, empirical, and normative contributions to the study of the political inclusion of minoritized populations. Empirically, we turn our scholarly gaze to a group of elected officials whose experiences of political violence have been almost completely overlooked. Our study is the first to use a large-scale survey (

![]() $ N=23,000 $

) to study violence against politicians with immigrant backgrounds, and particularly women.Footnote

1 Focusing on Swedish municipal politicians with large samples of politicians with immigrant backgrounds, we examine their experiences of different forms of physical and psychological violence, as well as their considerations of exiting politics. Our results indicate that representatives with immigrant backgrounds face significantly more physical and psychological violence than representatives without such backgrounds, all else equal. These differences persist for both online and offline harm. Moreover, both women and men with immigrant backgrounds face more violence than their counterparts. Furthermore, we find that these high levels of violence disproportionately push immigrant background politicians out of politics. Most troubling from the perspective of democratic inclusion is the finding that this consequence is most pronounced for women immigrant background politicians. They are more likely than both men with immigrant backgrounds and nonimmigrant women to consider leaving politics because of violence.

$ N=23,000 $

) to study violence against politicians with immigrant backgrounds, and particularly women.Footnote

1 Focusing on Swedish municipal politicians with large samples of politicians with immigrant backgrounds, we examine their experiences of different forms of physical and psychological violence, as well as their considerations of exiting politics. Our results indicate that representatives with immigrant backgrounds face significantly more physical and psychological violence than representatives without such backgrounds, all else equal. These differences persist for both online and offline harm. Moreover, both women and men with immigrant backgrounds face more violence than their counterparts. Furthermore, we find that these high levels of violence disproportionately push immigrant background politicians out of politics. Most troubling from the perspective of democratic inclusion is the finding that this consequence is most pronounced for women immigrant background politicians. They are more likely than both men with immigrant backgrounds and nonimmigrant women to consider leaving politics because of violence.

Normatively, this research brings attention to the unequal treatment that immigrant background politicians face, and pinpoints an additional arena for concern. That immigrant background representatives experience disproportionate levels of violence exacerbates the already pronounced barriers present for minority representation. And, that it is women politicians with immigrant backgrounds who are more likely than their men counterparts to consider exiting politics as a result of political violence is deeply troubling for democratic societies, and reinforces patterns of underrepresentation and marginalization of an already excluded group in politics. The decision to exit politics in part due to experiences of abuse not only highlights a loss in quality that the democratic state suffers when intimidation and harassment are directed at those tasked with governing (see Daniele Reference Daniele2019). It also indicates the removal of important (and underrepresented) perspectives from the deliberative decision-making process, which can in turn effectively render those political interests ignored.

Together, these findings complicate traditional theories about the unobserved costs of minority representation, and suggest one additional factor (i.e., the risk of political violence) that immigrant background individuals may perceive as more costly when considering whether to enter or remain in politics. The finding that some of the most underrepresented segments of the population face such disproportionate levels of threat in electoral politics deeply challenges democratic norms and practices. And, they are all the more pressing considering the breadth of research showing that descriptive representatives pursue the substantive interests of underrepresented groups (Hayes and Hibbing Reference Hayes and Hibbing2017; Mügge, van der Pas, and van de Wardt Reference Mügge, van der Pas and van de Wardt2019; Stout, Tate, and Wilson Reference Stout, Tate and Wilson2021), increase political trust (Gay Reference Gay2002; Hinojosa, Fridkin, and Kittilson Reference Hinojosa, Fridkin and Kittilson2017), and mobilize them into politics (Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Wong, Bloeser, Fredrickson and LaForge2022; Zetterberg Reference Zetterberg2009).

SWEDEN AS A CASE

Sweden is a suitable case for studying this question. The immigration patterns to Sweden have been similar to that of other European countries (e.g., Austria, Belgium, and Germany). During the postwar period, most immigrants were labor migrants from other European countries (Lundh and Ohlsson Reference Lundh and Ohlsson1999). As the demand for foreign labor decreased in the 1970s following the oil crises, migration policies became harsher across Europe (Lundh and Ohlsson Reference Lundh and Ohlsson1999). Since then, most immigrants have come to Sweden as refugees or on the basis of family reunification (Nilsson Reference Nilsson2004). Poland, Chile, Turkey, Iran, and India dominated as countries of origin during the 1970s–1980s. During the last decades since the 1990s, most immigrants have origins from Asian countries, including the Middle East, and the Balkans (Nilsson Reference Nilsson2004). Today, upwards 20% of the Swedish population is foreign born and one-third of Swedish residents have at least one parent who is foreign born (Statistics Sweden 2023). As we demonstrate in Figure A1 in the Supplementary Material, 26% of the Swedish population in 2010, and 28% in 2014, had an immigrant background (Statistics Sweden N.d.). Figure A2 in the Supplementary Material shows that about 16% of Swedish immigrants are from other Nordic countries. Visible minorities (e.g., immigrants from Africa, Asia, South America or former Yugoslavia) make up about 70% of the foreign-born population in 2010 and 2014 (Statistics Sweden N.d.).

In the political realm, egalitarianism and inclusion are largely unquestioned ideals, and all established political parties emphasize the importance of sociodemographic descriptive representation (Folke, Freidenvall, and Rickne Reference Folke, Freidenvall and Rickne2015). Nonetheless, immigrants in Sweden face numerous barriers in the labor market and are severely underrepresented both among the electorate and among elected politicians (e.g., Bäck and Soininen Reference Bäck and Soininen1998; Dahlstedt and Hertzberg Reference Dahlstedt and Hertzberg2007; Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Lindgren, Nicholson, and Oskarsson Reference Lindgren, Nicholson and Oskarsson2022; Lindgren and Österman Reference Lindgren and Österman2022; Vernby and Dancygier Reference Vernby and Dancygier2019). Much of this scholarship has demonstrated that their exclusion from politics is not for lack of resources, candidate supply, or political interest (Adman and Strömblad Reference Adman and Strömblad2015; Carlsson and Rooth Reference Carlsson and Rooth2007; Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Nyman and Vernby2021). Rather, discrimination by party gatekeepers appears to play an important role in perpetually excluding immigrants (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Nyman and Vernby2021). In Figure A1 in the Supplementary Material, we show that 16–17% of municipal politicians elected in 2010 and 2014 had an immigrant background (either as foreign born or as having at least one foreign-born parent). Among the politicians with immigrant backgrounds, about 48% of politicians elected in 2010 and 59% in 2014 are likely visible minorities (see Figure A2 in the Supplementary Material). Even though this is not on par with the share of immigrants in Sweden, this level of representation is relatively higher compared to many other Western European contexts (Bloemraad and Schönwälder Reference Bloemraad and Schönwälder2013).

Once they overcome the hurdles related to securing political office, significantly less is known about the violence and harm that immigrants and their descendants face as elected representatives. As immigration has rapidly and dramatically changed the makeup of the Swedish population in recent years, questions of the sociopolitical inclusion of those with immigrant backgrounds are of utmost importance. On the one hand, the rapid increase of immigrants in the Swedish population could be expected to lead to increased resistance and hostility from the dominant group. On the other hand, the political inclusion of immigrants is not lower in Sweden compared to other contexts. For example, in a comparative study of all EU member states, Weldon (Reference Weldon2006) notes that in Sweden, immigrants enjoy some political and voting rights prior to becoming citizens, and despite rather low levels of tolerance across the European countries in the sample, Sweden belongs to a category of countries with relatively higher levels of social and political tolerance. As such, any discrepancies found in the violence targeting politicians with immigrant backgrounds relative to politicians without such a background in Sweden are likely not exaggerated compared to other contexts.

Furthermore, Sweden is a society without significant cleavages along political or ethnic lines, which suggests that political violence is not expected to be particularly rampant compared to other cases. Nevertheless, elected officials in Sweden are increasingly experiencing threats in the course of their work (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021). Similar to other consolidated democracies, psychological violence such as threats and harassment is far more common than physical violence, and targets a substantial portion of Swedish politicians (see, e.g., Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019; Collignon and Rüdig Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Reference Collignon and Rüdig2021; Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Kosiara-Pedersen2024). In this vein, Erikson, Håkansson, and Josefsson (Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023) note that there has been an increase in the percent of Swedish politicians who report experiencing violence, harassment or threats from 20% in 2012 to 30% in 2018. Much of this abuse takes place online (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021). Except for the most high profile politicians such as party leaders and cabinet members, Swedish politicians generally manage their own social media accounts, email accounts, and other correspondence. This means that the politicians themselves (rather than their staff as in some other political systems) are the ones who regularly read and are exposed to offensive and threatening messages sent to them, and decide on how to handle them. In other words, for a significant share of Swedish politicians, handling violence exposure and its consequences is part of the itinerary (see Håkansson Reference Håkansson2024).

Sweden can thus be considered a case where violence likely targets politicians to a similar degree as comparable contexts, which makes findings regarding the difference in how politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds are targeted relevant beyond this case. Furthermore, contexts where violence is more prevalent in society may experience even more political violence than Sweden and the violence targeting immigrant background politicians in such contexts may be more severe.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH AND THEORETICAL EXPECTATIONS

It is well established that immigrants and other visible ethnic minorities are underrepresented in politics across most Western democracies (Auer, Portmann, and Tichelbaecker Reference Auer, Portmann and Tichelbaecker2023; Bird, Saalfeld, and Wust Reference Bird, Saalfeld and Wust2011; Bloemraad Reference Bloemraad2013; Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015), which marks a key deficit in political representation. The descriptive representation of historically marginalized groups has a particular symbolic value for fostering trust in the political system among members of marginalized groups, as well as for increasing their political legitimacy in society at large (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). On the flipside, the descriptive representation of minoritized groups has also been linked to explaining some voters’ preferences for majority candidates (Portmann Reference Portmann2022) and antipathy toward underrepresented candidates and policies (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Heath, Sanders and Sobolewska2015; Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2007; Lucas and Silber Mohamed Reference Lucas and Silber Mohamed2021).

Immigrants in Western Europe tend to participate less politically and report lower levels of political efficacy and inclusion (Adman and Strömblad Reference Adman and Strömblad2018; Bevelander and Pendakur Reference Bevelander and Pendakur2011; Esaiasson, Lajevardi, and Sohlberg Reference Esaiasson, Lajevardi and Sohlberg2024; Fennema and Tillie Reference Fennema and Tillie2001; Sohlberg, Agerberg, and Esaiasson Reference Sohlberg, Agerberg and Esaiasson2022). As such, despite facing institutional and societal barriers from running for political office,Footnote 2 once they run for and do win elected office, we know that anecdotally, minority political candidates and officials, particularly visible women of color, endure regular threats to their livelihoods (Farmer, Lee, and Day Reference Farmer, Lee and Day2022; Kleinfeld Reference Kleinfeld2022; Torelli Reference Torelli2022). Moreover, previous studies on violence against politicians in consolidated democracies find that psychological violence—such as harassment and attempts at frightening and threatening—is increasingly prevalent (Collignon and Rüdig Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020; Reference Collignon and Rüdig2021; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Herrick and Thomas. Reference Herrick and Thomas.2023). This body of work also notes that risks are not evenly distributed among politicians, and politicians’ individual characteristics predict their likelihood of violence exposure. For example, women and younger candidates suffer more harassment and intimidation in the United Kingdom (Collignon and Rüdig Reference Collignon and Rüdig2020), and U.S. mayors who are younger, female, in strong mayor systems and in larger cities experience more physical violence and psychological abuse (Thomas et al. Reference Thomas, Herrick, Franklin, Godwin, Gnabasik and Schroedel2019). We also know that harassment more often targets well-known, visible politicians (Gorrell et al. Reference Gorrell, Bakir, Roberts, Greenwood and Bontcheva2020; Rheault, Rayment, and Musulan Reference Rheault, Rayment and Musulan2019).

While it is often hypothesized that ethnic minority politicians face more and worse political violence than politicians of the dominant ethnicity (e.g., Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020), only a few empirical studies have begun to examine this claim. Kuperberg (Reference Kuperberg2021; Reference Kuperberg2022), for instance, analyzes online abuse directed at women MPs of various ethnicities in the United Kingdom and Israel, and finds that perpetrators mix racist and gendered tropes in abuse targeting ethnic minority women. Similarly, Erikson, Håkansson, and Josefsson (Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023) uncover testimonies from politicians of immigrant backgrounds about extensive racism targeting them online. Gorrell et al. (Reference Gorrell, Bakir, Roberts, Greenwood and Bontcheva2020) find that Muslim MPs in the United Kingdom are particularly targeted with racist rhetoric on Twitter, but the authors note that their sample of ethnic minority politicians is too small to draw general conclusions. A recent survey study with nine hundred U.S. mayors finds that white men experience fewer threats than men of color, women of color and white women (Herrick and Thomas Reference Herrick and Thomas2024). This study furthermore finds that women of color and white women experience significantly more gendered attacks than their men counterparts, but no differences in the frequency of gendered attacks on women of color and white women.

Social identity theory provides a lens through which to understand the potential for increased violence: immigrant background politicians symbolize a threat to the status quo, resulting in their becoming targets of violence for those who wish to maintain existing norms and hierarchies (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Jost and Sidanius1986). Ethnic minorities and individuals with immigrant backgrounds are often perceived as outsiders in politics, and their historical exclusion from politics continues to shape norms for politicians (Puwar Reference Puwar2004). Including immigrants in politics can be perceived as a direct challenge to the dominant political order, and may provoke aggressive means to maintain existing hierarchies. Additionally, immigrant background politicians’ outsider status renders them less likely to having access to resources and support from institutions and parties (e.g., Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Nyman and Vernby2021), and more likely to encounter a political landscape where their legitimacy is more scrutinized than their peers (Puwar Reference Puwar2004). This can render them more susceptible to political violence. For example, when political leaders invoke hateful rhetoric and underscore immigrant politicians’ lacking credibility or outsider status, this speech may foster negative sentiments, normalize hateful speech, and also encourage supporters to take action against the immigrant background politician (Byman Reference Byman2021). The effects of this violence are compounded for immigrant background politicians who have fewer entrenched support networks, which are essential for coping with and mitigating political violence, but also may result in their disproportionate experiences of social and political isolation.

Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020) argue that in order to evaluate how violence perpetuates political inequalities, researchers should investigate why, how, and with what impact underrepresented groups of politicians are attacked compared to hegemonic men. Hegemonic men in terms of ethnicity, age, and class dominate politics worldwide, though the specific configuration of hegemony takes on different shapes depending on the local context (Murray and Bjarnegård Reference Murray and Bjarnegård2024). Violence against marginalized groups of politicians can therefore be compared to violence targeting hegemonic men in order to discern whether, and in what ways, violence is biased (see also Krook and Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2020).

Based on what we know about levels of discrimination that people with immigrant backgrounds experience in various realms such as the labor market and political recruitment, we expect politicians with such backgrounds to experience more violence compared to those without immigrant backgrounds.

H1: Relative to their counterparts without immigrant backgrounds, politicians with immigrant backgrounds are more likely to be exposed to violence.

Furthermore, women ethnic minorities face marginalization based on two salient features of their identity: gender and race. Previous research on intersectionality highlights how multiple axes of exclusion and oppression intersect to heighten the vulnerability of people with several marginalized identities (Brewer Reference Brewer1999; Brown Reference Brown2014; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Hancock Reference Hancock2007). Scholarship is consistently demonstrating that disparities in sectors like health, labor market, education, politics, and more affect women of color the greatest (e.g., Brown and Lemi Reference Brown and Lemi2021; Cornelius, Smith, and Simpson Reference Cornelius, Smith and Simpson2002; Fraga and Hassell Reference Fraga and Hassell2021; Gershon et al. Reference Gershon, Montoya, Bejarano and Brown2019; Jordan, Lajevardi, and Waller Reference Jordan, Lajevardi and Waller2023; Lemi and Brown Reference Lemi and Brown2019; Malveaux Reference Malveaux1999; McLemore et al. Reference McLemore, Altman, Cooper, Williams, Rand and Franck2018). In particular, Brown (Reference Brown2014, 315) points out that “individuals with multiple subordinate group identities, namely, racial and ethnic minority women,” differ from their white majority counterparts when it comes to political mobilization, participation, and interest. There are mixed findings from European contexts about to what extent parties actively recruit immigrant origin women into politics (Bird Reference Bird2016; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Erzeel, Mügge and Damstra2014; Folke, Freidenvall, and Rickne Reference Folke, Freidenvall and Rickne2015; Jenichen Reference Jenichen2020). Studies from the United States find that women of color are indeed mobilizing into politics, though the costs of entry into politics remain high and they are less likely to be recruited to run for office (Bejarano and Smooth Reference Bejarano and Smooth2022; Shah, Scott, and Gonzalez Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Gonzalez Juenke2019). But, even once they are in office, women of color face high rates of marginalization, violence, and harassment (Brown and Gershon Reference Brown and Gershon2023; Dowe Reference Dowe2022; Herrick and Thomas Reference Herrick and Thomas2024; Norwood, Jones, and Bolaji Reference Norwood, Jones and Bolaji2021). We thus have reason to expect that women with immigrant backgrounds face particularly high risks of violence in politics.

H2: Women politicians with immigrant backgrounds will experience more violence than men politicians with immigrant backgrounds and women politicians without immigrant backgrounds.

Furthermore, as Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020) recommend, it is imperative to consider potential gendered or intersectional differences in the consequences of political violence. A key question in this regard concerns whether violence deters its targets from maintaining their political roles, threatening minority politicians’ roles as descriptive representatives of already-marginalized and politically excluded groups (see e.g., Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020; Bjarnegård, Håkansson, and Zetterberg Reference Bjarnegård, Håkansson and Zetterberg2022; Erikson, Håkansson, and Josefsson Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023; Håkansson Reference Håkansson2021; Herrick and Franklin Reference Herrick and Franklin2019; Krook and Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2020). Politicians with immigrant backgrounds experience multiple forms of marginalization in politics. This could entail that violence has a more significant impact on immigrant background politicians’ sense of belonging in politics (see Hawkesworth Reference Hawkesworth2003; Puwar Reference Puwar2004), and a more severely discouraging impact. Previous work has found that perceived discrimination has an antidemocratic and politically demobilizing effect, as can be seen in studies in the United Kingdom (Oskooii Reference Oskooii2020), Canada (Bilodeau Reference Bilodeau2017), the United States (Oskooii Reference Oskooii2016), and elsewhere. Experiences of hostility and violence may similarly deter elite level political participation among individuals with an immigrant background.

Taken together, we argue that violence can have differential impacts for politicians with and without immigration backgrounds. Against the backdrop of immigrant background politicians’ experiences of various forms of discrimination in Swedish politics and wider society, violence can be more damaging to their political ambition than counterparts who, for example, have not experienced discrimination within their own party. Intersectionality theory would posit that such experiences are particularly likely to increase the marginalization of individuals with multiple subordinated group identities. Consequently, we hypothesize that violence in politics will prompt people with immigrant backgrounds, and especially women politicians, to be prone to leave politics.

H3: Relative to politicians without immigrant backgrounds, those politicians with immigrant backgrounds will be more inclined to consider leaving politics because of violence.

H4: Women politicians with immigrant backgrounds will be more inclined to consider exiting politics because of violence than will men politicians with immigrant backgrounds and women politicians without immigrant backgrounds.

DATA, CONCEPTS, AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

To evaluate levels of violence, we turn to survey data over other alternatives for multiple reasons. While surveys inevitably come with challenges related to reliability and consistency, given the varied interpretations respondents may have toward questions and concepts, there are no objective measures available for politicians’ exposure to violence. Political violence research often leans on media reports for documenting violent incidents. However, these reports have been shown to be inconsistent, often favoring certain types of incidents and focusing more on specific localities (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018; Von Borzyskowski and Wahman Reference Von Borzyskowski and Wahman2021). A growing literature on politician harassment draws from Twitter data, and while this might standardize definitions of harassment, hostility, and hate speech, such data do not capture the entirety of online abuse politicians experience. This is especially the case when one considers that direct threats which Twitter deletes, or hostile messages sent privately rather than publicly, are not available to researchers (see also Erikson, Håkansson, and Josefsson Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023). Moreover, social media datasets naturally do not capture offline violence.

For sensitive topics such as exposure to violence, self-reported data run the risk of underestimating the frequency, or unbalanced reporting across social groups (Traunmüller, Kijewski, and Freitag Reference Traunmüller, Kijewski and Freitag2019). Research on underreporting has found that lower education is correlated with more underreporting (Antecol and Cobb-Clark Reference Antecol and Cobb-Clark2004). Among Swedish politicians, there are no differences in the level of education between those with and without an immigrant background (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Nyman and Vernby2021). However, research in this area has also demonstrated that ethnic minorities and those with lower trust in the government are more likely to underreport violence exposure (Traunmüller, Kijewski, and Freitag Reference Traunmüller, Kijewski and Freitag2019). Similarly, criminology research shows that immigrants are less likely than others to report their crime victimization (Menjívar and Bejarano Reference Menjívar and Bejarano2004) and in particular victimization to violent crime (Gutierrez and Kirk Reference Gutierrez and Kirk2017). This would suggest that the violence reported by immigrant background politicians in our sample risks being underreported compared to the politicians without such backgrounds. Accordingly, we are more likely to underestimate than over-estimate the difference in violence exposure between immigrant background and nonimmigrant background politicians.

We use three waves of the Politicians’ Safety Survey (Politikernas Trygghetsundersökning, PTU), conducted in 2012, 2014, and 2016 by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (Brottsförebyggande rådet N.d.).Footnote 3 Each wave targets all thirteen thousand Swedish elected politicians, and has a response rate consistently above 60%. As a result, we have about 8,000 observations per wave and a total of 23,000 observations. Sample demographics closely align with the overall population of politicians in terms of party and gender (see Table A1 in the Supplementary Material). In order to obtain large enough samples of politicians with immigrant backgrounds that enable comparisons to politicians without immigrant backgrounds, we focus our analyses on the municipal level. This survey, crafted by criminologists under the Swedish government’s directive, aims to gauge the magnitude of violence and crime faced by Swedish politicians. It encompasses a broad spectrum of violent actions, spanning physical to psychological forms, and even bribe attempts (which we exclude). Importantly, respondents were instructed to report only perceived threatening incidents.

Following the WHO definition, we conceptualize violence as actions intended to cause either physical or psychological harm to the target. Inspired by categorizations of different forms of violence in feminist literature (Krook and Restrepo Sanín Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanín2016), we distinguish between five different forms of violence: (1) bodily violence (i.e., violence aimed at the target’s bodily integrity); (2) property damage (i.e., physical violence against the target’s property); (3) threats (i.e., threats against the target or their family); (4) harassment (i.e., intrusive or implicitly threatening actions); and (5) character assassination (i.e., spreading negative accounts of the target publicly).

Table 1 details these violent behaviors and their categorizations. As evident from the table, psychological violence, encompassing threats, harassment, and character assassination, is the predominant form experienced by Swedish municipal politicians, with online platforms being the primary venues for violence. Physical violence, encompassing bodily violence and property damage, also occur though more rarely. Each year, about 25% of Swedish municipal politicians experience at least one form of violence. On average, 48% of the violence exposed politicians have only experienced violence of one form, and 24% have experienced two forms of violence. In other words, experiencing multiple forms of violence is rare even among the violence exposed politicians.

Table 1. Five Forms of Violence against Politicians

EMPIRICAL APPROACH

Following the methodology outlined by Bardall, Bjarnegård, and Piscopo (Reference Bardall, Bjarnegård and Piscopo2020), we compare the frequency and nature of violence against politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds. Since it is prohibited under Swedish law to collect data on race or ethnicity, we use the PTU survey question regarding whether the respondent and their parents were born in Sweden or abroad. While this measure does not perfectly capture race or ethnicity, it indicates an important distinction between the crude groups of politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds. Because immigrants as well as their descendants often constitute equally visible minorities in terms of physical appearance and name, we probe the influence of immigrant background to understand the experiences of those individuals who have immigrated as well as those whose parents have immigrated to Sweden. We define politicians with an immigrant background as either being foreign born or having at least one foreign born parent. Our main dataset hence does not identify which country or region immigrant background politicians have immigrated from. We use Swedish registry data to describe the composition of the Swedish population and Swedish municipal politicians in Figures A1 and A2 in the Supplementary Material. These figures show that the share of politicians who are foreign born and have foreign-born parents are about equally large, and that roughly half of foreign-born politicians are visible minorities (i.e., excluding politicians from Northern, Western, and Eastern Europe and from North America and Oceania). While we cannot be certain that this perfectly mirrors our survey sample, we can reasonably assume that a substantial share of our sample of politicians with an immigrant background are visible minorities. Since the discrimination of people in Sweden with an immigrant background can be expected to be particularly severe for visible minorities (see, e.g., Osanami Törngren Reference Osanami Törngren2022), our definition of immigrant background is more likely to underestimate than overestimate the violence experienced by immigrant-background politicians.

We pool all three waves of survey data into a single dataset, and include fixed effects for survey waves in each model. We measure exposure to each of the five forms of violence, as well as a binary measure, which we refer to as “Violence (aggregate)” and which captures whether politicians have experienced any form of violence. We then estimate differences between those politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds. Building on Håkansson (Reference Håkansson2021), we include controls for individual level characteristics that have been identified as important predictors of politicians’ violence exposure in previous research, including age, gender, status as newcomer in politics and level of prominence (hierarchical level). We use fixed effects for 290 municipalities and 8 political parties in order to compare politicians from the same political party and the same municipality, and cluster standard errors at the municipal level. Table A1 in the Supplementary Material displays summary statistics.

RESULTS

Violence Targeting Immigrant Background Politicians

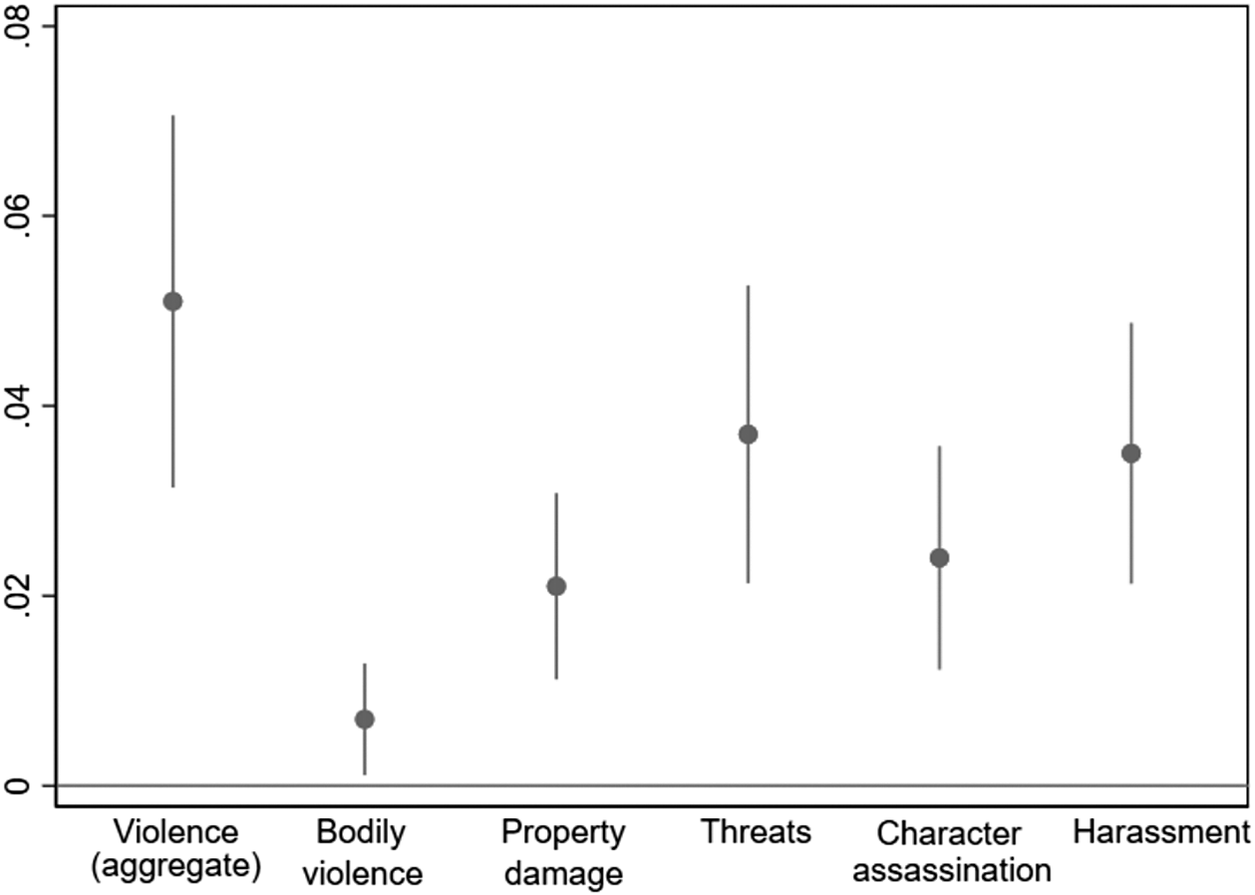

We begin by evaluating whether politicians with immigrant backgrounds face higher risks of violence, to test H1. Figure 1 presents coefficient plots from six multivariate OLS regressions depicting the relationship between our key independent variable—immigrant background—and any form of violence, as well as the five individual forms of violence. The corresponding regression analyses can be found in Table A2 in the Supplementary Material.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Violence against Politicians with and without an Immigrant Background

Note: The figure displays the size of the difference in exposure to violence between politicians with and without an immigrant background, with 95% confidence intervals. The zero-line indicates violence against politicians without an immigrant background, i.e., the control group. Positive estimates indicate that politicians with an immigrant background experience more violence, and negative that they experience less, compared to the control group. Models are specified as in Table A2 in the Supplementary Material. Data from PTU 2012, 2014, and 2016.

Several important takeaways can be gleaned from these analyses. First, politicians with immigrant backgrounds are consistently and significantly more likely than those politicians without immigrant backgrounds to report facing violence, confirming H1. In the aggregate, those with immigrant backgrounds are about 5 percentage points more likely than those without such backgrounds to suffer any form of harm. Given that at baseline, almost 19 percent of politicians without immigrant origins experience at least one form of violence, a 5 percentage point difference is of substantial importance. As Table A2 in the Supplementary Material denotes, this difference is not driven by structural factors such as in which parties or municipalities these immigrant background politicians are elected. Furthermore, the differences are robust to controlling for individual characteristics such as the politician’s age, gender, and newcomer status. Among politicians who advance similar agendas (i.e., represent the same party), are equally well-established as newcomers or long-term incumbents, hold equally prominent positions in the political hierarchy, and are of the same age and gender, politicians with immigrant backgrounds are significantly more likely to experience violence in Swedish politics.

Second, this difference persists across each category of violence. To further unpack whether a specific form of violence drives the differences between politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds, we analyze five forms of violence separately. As can be seen in Figure 1 and in Table A2 in the Supplementary Material, estimates for all forms of violence are positive and statistically significant, indicating that the types of additional attacks that politicians with immigrant backgrounds sustain are multiple. The differences between politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds are largest for the categories of “threats” (3.7 percentage points) and “harassment” (3.5 percentage points) which are also the most common forms of violence against Swedish politicians overall. The same goes for “character assassination,” which immigrant background politicians are 2.4 percentage points more likely to experience. Furthermore, even the forms of violence that are comparatively rare in Sweden, such as bodily violence and property damage, are more common for politicians with immigrant backgrounds, with a 0.7 and 2.1 percentage points higher probability of experiencing such attacks, respectively.

Finally, our results reveal that politicians with immigrant backgrounds are significantly more likely to experience multiple forms of violence, compared to their counterparts (see Table A2 in the Supplementary Material, Model 7). This result persists, as Table A4 in the Supplementary Material also denotes, when we employ a zero-inflated negative binomial regression: politicians with immigrant backgrounds, as well as women politicians, are less likely than their counterparts to experience zero forms of violence. In other words, politicians with immigrant backgrounds are not only more likely to be targeted with violence at all, but also more likely to be targeted in multiple different ways.

Unpacking the Role of Gender

Next, we explore the impact of politicians’ background in combination with their gender to investigate H2, in Figure 2 and Table A5 in the Supplementary Material. Here, we compare the experiences of immigrant background politicians to nonimmigrant background politicians of their own gender group. Thus, these analyses compare the experiences of women with immigrant backgrounds to women without immigrant backgrounds, and men with immigrant backgrounds to men without immigrant backgrounds.

Figure 2. Violence against Women and Men with and without an Immigrant Background

Note: The figure displays the size of the difference in exposure to violence between politicians with and without an immigrant background, with 95% confidence intervals. The zero-line indicates violence against politicians without an immigrant background, i.e., the control group. See further description in the note of Figure 1. Circles report the violence exposure among women with an immigrant background relative to women without an immigrant background. Squares report the same for the group of men. Models are specified as in Table A5 in the Supplementary Material. Data from PTU 2012, 2014, and 2016.

For our aggregate measure of violence, we find that the baseline reporting of violence among men and women without immigrant backgrounds is gendered, at 16.8% and 23.8%, respectively. Moreover, we find that men with immigrant backgrounds are 5.9 percentage points more likely than men without immigrant backgrounds, and women with immigrant backgrounds are 4.3 percentage points more likely than women without immigrant backgrounds, to experience violence in the aggregate (see Table A5 in the Supplementary Material, Models 1 and 7).

We also evaluate each individual form of violence (see Table A5 in the Supplementary Material, Models 2–6 and 8–12). We find that men with immigrant backgrounds were significantly more likely than men without immigrant backgrounds to experience four of five types of violence probed; for example, property damage (2.4 percentage points), threats (3.7 percentage points), character assassination (3.5 percentage points), and harassment (4.4 percentage points). The results for women differ somewhat, largely due to the high baseline that exists for certain types of harms. We find that women with immigrant backgrounds were significantly more likely than women without immigrant backgrounds to experience three of five types of violence; that is, property damage (1.7 percentage points), threats (4 percentage points), and harassment (2.5 percentage points). Contrary to what we would have expected, though positive and large in substantive size, the coefficients for immigrant background among women did not rise to conventional levels of statistical significance for bodily violence and character assassination.

Importantly, we find that women and men with immigrant backgrounds are equally likely to experience more violence of all types examined compared to their nonimmigrant background gender counterparts. The estimate for the difference between minority and majority men is somewhat larger than for women for the aggregate violence exposure, driven by character assassination. However, the confidence intervals overlap and differences across gender are not of a substantially large size. Table A6 in the Supplementary Material also examines this question using a different modeling strategy: it employs an interaction term between woman politician and immigrant background, and confirms this finding. Within the group of women, those with immigrant backgrounds experience the most violence. But within the group of politicians with an immigrant background, women and men are at an equal risk of experiencing violence.

In this context, it is important to remember that our data merely capture the frequency of violence and not details regarding its character (cf. Erikson, Håkansson, and Josefsson Reference Erikson, Håkansson and Josefsson2023). We do not know based on the PTU data whether different tropes are used against women and men immigrant background politicians, for example. However, focusing specifically on the frequency of political violence, our results show that women and men politicians with immigrant backgrounds are at a similarly heightened risk of violence compared to those politicians without immigrant backgrounds, challenging our theory and expectations in H2. This indicates that perpetrators are equally motivated to wage violence on women and men politicians with an immigrant background.

Extensions and Additional Analyses

Next, we conduct several additional analyses to improve our understanding about the factors that may be driving the difference between how perpetrators target politicians with and without migration backgrounds.

Disaggregating between the “First” and “Second” Generation

We begin by disaggregating politicians by the type of immigration background: into individuals who have themselves immigrated to Sweden, and individuals who have at least one parent who immigrated to Sweden. On the one hand, descendants of immigrants may be easily identified, either because if they are descendants of visible minorities they are often also visible minorities, or because they have names that signal their immigrant backgrounds, or a combination of the two. On the other hand, previous research has identified differences in the political inclusion of first and second generation immigrants.

Research has consistently shown in multiple country contexts that second- (and in some cases even later-) generation descendants of immigrants hold more liberal political ideologies and exhibit lower trust in political institutions than their first-generation counterparts. In the United States, later generations are more politically liberal than first generation Latinos (Barreto and Pedraza Reference Barreto and Pedraza2009; Bejarano Reference Bejarano2014), and second-generation Latinos hold lower levels of political trust than first generation (Abrajano and Alvarez Reference Abrajano and Alvarez2010), simply because, as the authors put it “first-generation immigrants are generally more optimistic and enthusiastic about the economic opportunities that await them in their host country” (137). Similarly, in a review of political trust across 24 European countries, Maxwell (Reference Maxwell2010) finds lower overall levels of trust in Parliament and government satisfaction among second-generation individuals compared to their first-generation counterparts (Table 1).

A body of research across various national contexts, including in the United States and Western Europe, find that second-generation immigrants report higher levels of perceived discrimination compared to the first generation, often referred to as an “integration paradox” (e.g., Alanya, Baysu, and Swyngedouw Reference Alanya, Baysu and Swyngedouw2015; Esaiasson, Lajevardi, and Sohlberg Reference Esaiasson, Lajevardi and Sohlberg2024; Lajevardi et al. Reference Lajevardi, Oskooii, Walker and Westfall2020; Verkuyten Reference Verkuyten2016; Yazdiha Reference Yazdiha2019). This indicates that in many contexts political trust and optimism do not naturally increase with greater cultural and social integration within the host society. Nevertheless, others have instead found that descendants of immigrants have acculturated into the host society much more than the first generation because they have had more opportunities for equal contact with members of the host country, and therefore may be more culturally integrated (e.g., André and Dronkers Reference André and Dronkers2017; Lindemann Reference Lindemann2020; van Maaren and van de Rijt Reference van Maaren and van de Rijt2020).

We examine potential differences across generations in Figure 3. It compares foreign born politicians to politicians without immigrant backgrounds (circles), and politicians with foreign born parents to politicians without immigrant backgrounds (squares). The corresponding regression analyses, which include the same controls as Table A2 in the Supplementary Material, can be found in Table A7 in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 3. Type of Migration Background and Violence

Note: The figure displays the size of the difference in exposure to violence between politicians with and without an immigrant background, with 95% confidence intervals. The zero-line indicates violence against politicians without an immigrant background, i.e., the control group. See further description in Figure 1. Circles report the violence exposure among politicians who have immigrated to Sweden relative to the control group, and squares report the violence exposure among politicians whose parents have immigrated to Sweden relative to the control group. Models are specified as in Table A7 in the Supplementary Material. Data from PTU 2012, 2014, and 2016.

Our results indicate that politicians from both groups similarly experience more violence than politicians without immigrant backgrounds. Driven by the subcategory of harassment, politicians whose parents immigrated to Sweden appear to experience slightly more violence in the aggregate than politicians who immigrated themselves, and two forms of violence (bodily violence and harassment) lose statistical significance for the politicians who have immigrated themselves but not for those who have an immigrant parent.

On the whole, perpetrators’ excessive targeting of politicians with immigrant backgrounds seems to apply about equally to first and second generation migrants. The results suggest that perpetrators assess and treat politicians differently based on signals of immigrant background, such as physical appearance and name, rather than actual characteristics, like language skills, that likely differ between first and second generation immigrants. This indicates that immigrant background politicians’ experiences of political violence are affected by their racial and ethnic identities, rather than any purported lack of integration or assimilation on their part—a notion that is also easily refuted by their active participation in electoral politics. Together, this evidence suggests that racial discrimination acts as a primary catalyst for the violence encountered by politicians with immigrant backgrounds, independent of generational status or efforts to participate in the civic fabric of society.

Exploratory Analysis: How Geography Matters for Experiences of Harm

Next, we conduct an exploratory analysis and consider briefly whether geography matters for shaping experiences of political violence. Average estimates could be hiding considerable heterogeneity about where politicians with migrant backgrounds are most at risk. Accordingly, we estimate the difference in violence against politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds across different types of municipalities. Our first analysis, found in Table A8 in the Supplementary Material shows that the difference in violence exposure is the most pronounced in medium-sized cities (difference of 7 percentage points), followed by smaller cities and rural communities (4 percentage points), and large cities (3 percentage points). The estimated risk of violence is higher for those with immigrant backgrounds than those without immigrant backgrounds in all types of municipalities. But in large cities, the difference between politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds is not statistically significant, which might be attributable to the lower number of observations.

We also consider whether representing municipalities with a larger immigrant population shields representatives with immigrant backgrounds from exposure to violence. Extant work has found that ethnic enclaves allow immigrant newcomers to “bond” with those who also have immigrant backgrounds (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973), and in turn, have a positive mobilizing effects into politics (Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022). Here, it could be that being an elected representative in an area with larger shares of foreign born residents could render immigrant background politicians to facilitate contact with constituents they are more likely to descriptively represent, and might reduce the likelihood of conflict. In Table A9 in the Supplementary Material, we examine whether the direction, size, and prediction power of the gap in violence exposure between politicians with and without an immigrant background varies in municipalities with varying shares of foreign-born inhabitants. Using the quartiles as cut-off points, we find positive estimates ranging between 3.7 and 6.4 percentage points for all four groups of municipalities, with only estimates in the third quartile not reaching traditional levels of statistical significance. Figure A3 in the Supplementary Material investigates these patterns further, and demonstrates that there does not appear to be any systematic variation. Hence, we conclude that the share of foreign born in the municipality does not seem to have a noteworthy impact on the relative violence exposure of immigrant background politicians compared to nonimmigrant background politicians.

EXAMINING THE ANTIDEMOCRATIC IMPACTS OF POLITICAL VIOLENCE

Last, we investigate H3 and H4 and focus on the impact of the heightened risks facing immigrant background politicians. The PTU survey asks respondents whether they have considered leaving politics as a consequence of violence in politics.Footnote 5 This question is posed to all survey respondents regardless of whether they have experienced violence or not. This allows us to analyze how violence affects political systems in a broader sense than impacts on the direct targets. We test H3 by analyzing whether politicians with immigrant backgrounds are more likely to consider exiting politics as a consequence of violence in Table 2. We first test whether there is a difference between politicians with and without immigrant backgrounds in the full sample.

Table 2. Considering Leaving Politics because of Violence

Note: Survey item: “Have you at any point during the previous year, due to exposure and/or worrying considered leaving all political assignments?” The Constant reports the average share of politicians without an immigrant background who considered leaving politics. The coefficient for Immigrant background reports the difference between politicians with and without an immigrant background in percentage points. Young is defined as below 35 years, and Newcomer as serving one’s first term. Woman is a dichotomous variable for the politician’s gender. Data from PTU 2012, 2014, and 2016. Standard errors clustered at 290 municipalities. ***

![]() $ p<0.01 $

; **

$ p<0.01 $

; **

![]() $ p<0.05 $

; *

$ p<0.05 $

; *

![]() $ p<0.1. $

$ p<0.1. $

As shown in Table 2, Models 1–3, this consequence is indeed more likely for politicians with immigrant backgrounds than for those without.Footnote 6 In the general population of politicians in our sample (Model 1), those with immigrant backgrounds are 3.5 percentage points more likely than the baseline to consider leaving all political assignments due to either exposure or worry about violence, and women politicians (with or without an immigrant background) are 1.9 percentage points more likely.

Next, when we rerun the analysis and restrict the sample of politicians to only those who have reported experiencing violence, the difference between politicians with and without an immigrant background reveals even starker disparities. This analysis, reported in Table A11 in the Supplementary Material, reveals that politicians with an immigrant background, after facing violence, are notably more inclined than their nonimmigrant counterparts to contemplate abandoning their political roles. Specifically, we find that among all violence-affected politicians, immigrant background individuals are 5.4 percentage points more likely to consider exiting politics than are their counterparts. This trend persists across gender lines. When we restrict the sample only to women politicians, immigrant background politicians are 8 percentage points more likely than their counterparts to considering departure (Model 2), and when we limit the sample to only men politicians, immigrant background politicians are 4.7 percentage points more likely to consider departure. When juxtaposed with the baseline findings in Table 2, which considered all politicians irrespective of their direct exposure to violence, the heightened vulnerability of violence-exposed politicians, particularly those with an immigrant background, becomes even more evident.

Furthermore, we test whether there is also such a difference within the group of politicians who have not experienced violence in the previous year (see Table A12 in the Supplementary Material). Here, Models 1–3 indicate that immigrant background politicians, who had not been exposed to violence over the past year, were still more likely than their peers to consider leaving politics as a result of worrying about violence. This tells us something about how awareness about increased risks for politicians with immigrant backgrounds may be spilling over to their colleagues and rendering politicians with immigrant backgrounds to feel more vulnerable even if they have not personally been targeted. Collectively, these findings reinforce the notion that immigrant background politicians bear a disproportionate brunt leading them to be more likely to consider a departure from politics as a result of political violence, providing support for H3.Footnote 7

Perhaps most importantly, the consequences of political violence are distinctly raced and, arguably, also gendered among the group of politicians with immigrant backgrounds. First, the impact on political ambition is about equally large for women and men politicians with immigrant backgrounds when we compare them to their nonimmigrant background gender counterparts (Models 2 and 3). In other words, violence poses a risk to descriptive diversity across both gender groups. Turning to Model 4 in Table 2, we examine only those politicians with immigrant backgrounds, and find that women with immigrant backgrounds are 2.8 percentage points more likely than their immigrant men counterparts (the baseline) to consider leaving politics because of violence. These findings extend what we have learned from extant scholarship, namely that Swedish women are more likely than men to be driven out of politics as a result of violence (Håkansson Reference Håkansson2024). These results not only corroborate these earlier findings (see Model 1), but also indicate that these patterns are also mirrored among immigrant background politicians. In line with H4, women with immigrant backgrounds are more likely to consider leaving politics than both women without immigrant backgrounds and men with immigrant backgrounds. The most sobering fact emerges when one considers who these women represent: women politicians with immigrant backgrounds in Sweden are the closest proxies to women of color in the political realm, a group already grappling with underrepresentation and inadequate political resources. It is a significant concern for democratic political systems when those most underrepresented become the most susceptible to the disengaging effects of political violence.

CONCLUSION

Violence that targets politicians in the course of their work has severe implications for democracy, as violence constitutes an undue intervention in the course of political work. When specifically directed at politicians of marginalized identities, the danger is amplified, as it further alienates and marginalizes them from the political sphere (Krook and Sanín Reference Krook and Sanín2020). Whereas previous research has identified gendered forms of violence directed at women in politics, this study demonstrates that another group of marginalized politicians—namely, those with immigrant backgrounds—likewise is at a severe disadvantage induced by violence.

Our results indicate that immigrant background politicians are at a significantly higher risk of violence than those politicians without immigrant backgrounds, and this applies equally to women and men. We furthermore find that experiences of political violence have severe consequences for descriptive representation. Violence-exposed immigrant background politicians are more likely than their counterparts to consider prematurely departing from elected office. This finding is not limited to just those who experience violence firsthand. Rather, the mere threat or fear of violence induces similar considerations.

Finding such discrepancies between violence targeting politicians with and without an immigrant background in Sweden has implications beyond this case. The migration patterns to Sweden mirror those of many European countries who all struggle to include immigrated citizens politically and socially. Our findings suggest that similar patterns in violence against politicians are likely found in other contexts as well. It should also be noted that these results were found during a time period that does not capture the increased tensions following the large inflow of refugees in 2016. Anti-immigrant rhetoric and support for the far-right has increased in Sweden—and elsewhere—after our study period, leading us to expect that the situation may have deteriorated since.

Together, this research has pressing implications for the costs of minority representation. The election of minority candidates certainly helps to ameliorate descriptive representation gaps, which, as extant research has repeatedly demonstrated, are vast in Western democracies along the lines of race, migration status, and gender among political elites (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Lindgren, Oskarsson and Vernby2015; Folke and Rickne Reference Folke and Rickne2016; Hughes Reference Hughes2013; Martin and Blinder Reference Martin and Blinder2021; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2020). But, this research helps to show the ways in which the supply—and particularly the retention—of willing candidates from marginalized groups, such as those with immigrant backgrounds, may be restricted by the violence that targets them. Given that minorities in Sweden and the US report feeling they would be less welcome among other politicians if they were to pursue a political career (Lajevardi, Mårtensson, and Vernby Reference Lajevardi, Mårtensson and Vernby2024), future research should examine whether the risk of political violence may be deterring some potential candidates from seeking elected office among latent candidates.

This work arguably presents new avenues for future research. For example, we encourage future research to investigate potential differences in violence exposure among politicians with migrant origins from different regions, visible versus non-visible minorities, and to what extent and in what ways race, ethnic, and immigrant backgrounds shape the experiences of political violence in distinct ways (see Herrick and Thomas Reference Herrick and Thomas2024). Research in this area may also be able to highlight whether immigrant enclaves affect the level of violence waged on politicians with immigrant backgrounds (see, e.g., Andersson et al. Reference Andersson, Lajevardi, Lindgren and Oskarsson2022; Bhatti and Hansen Reference Bhatti and Hansen2016; Fieldhouse and Cutts Reference Fieldhouse and Cutts2008).

Moreover, our analyses of the intersection of immigration background and gender raise further questions about how political violence might affect the political candidacies of other underrepresented groups in politics. For example, our analyses consistently find that young politicians report higher levels of political violence, across the board. For those scholars concerned with the underrepresentation of young people among political elites, this may be a finding worthy of future research (see ongoing work by Anlar Reference Anlar2022). Preliminary interaction analyses we conducted suggest that experiences of young politicians do not differ based on their migration background, but more detailed research is needed on this topic.

Finding that immigrant background politicians are more likely to experience violence, and to be targeted in multiple different ways, than their counterparts without such backgrounds underscores a pervasive atmosphere of insecurity among immigrant background politicians. That immigrant background women bear the brunt of these consequences demonstrates the ways in which experiences of political violence are not uniform for elected representatives, and how these women harbor multiple axes of exclusion that make them particularly vulnerable to weighing an exit from political office as a result of violence. Together, these findings indicate that the shadow of violence looms over a broad spectrum of politicians of historically underrepresented groups and magnifies their collective sense of vulnerability.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542400100X.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EW2GV5. Limitations on data availability are discussed in the Supplementary Material.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We have received helpful comments from many colleagues, including Per Adman, Michal Grahn, Lutz Gschwind, Gina Gustavsson, Cassandra Engeman, Moa Mårtensson, Camilla Reuterswärd, Kåre Vernby, and participants of the Polsek seminar at the Department of Government at Uppsala University. We thankfully recognize advice from Olle Folke and Karl Oskar Lindgren in particular. Finally, the comments from the editors and three anonymous reviewers significantly contributed to improving this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

This research was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Board 2017/440. The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board, Uppsala and certificate numbers are provided in the Supplementary Material. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the principles concerning research with human participants laid out in APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research (2020).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.