Introduction

Parents caring for a child with a skin condition can have demanding routines encompassing a range of additional responsibilities such as administering intensive treatments and attending regular hospital appointments (Ablett and Thompson, Reference Ablett and Thompson2016; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). Meeting the practical and psychological needs of their child can be time consuming and parents might have to draw upon their levels of resilience and self-compassion at the expense of their own psychological wellbeing or self-care (Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, Hobbs and Arthur2019; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). Parents and children affected by skin conditions have expressed a desire for greater access to psychological support and the opportunity to connect with other families with similar experiences (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022).

Mindfulness is being increasingly applied across a variety of healthcare settings and involves developing the ability to observe what is happening in the present moment, without judgement (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn1994). The approach has shown promise as an effective intervention for children with physical health conditions, and their parents (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2023; Ruskin et al., Reference Ruskin, Young, Sugar and Nofech-Mozes2021). For example, psychological flexibility and self-compassion could be important mechanisms to target with mindfulness-based approaches. Increasing openness to experience and kindness towards the self could help parents of children with skin conditions manage stress and feelings of uncertainty surrounding treatment and disease progression (e.g. Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). Indeed, there has been some evidence to suggest that levels of dispositional mindfulness could be associated with greater wellbeing in parents of children with psoriasis or eczema, and their children (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2021).

Many inflammatory skin conditions have been associated with increased levels of perceived stress (Balieva et al., Reference Balieva, Schut, Kupfer, Lien, Misery, Sampogna, von Euler and Dalgard2022). For children with skin conditions, there could be secondary beneficial outcomes from calmer parental interactions. Heapy et al. (Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022) delivered a mindful parenting intervention to parents of children with eczema and psoriasis and reported reductions in parental stress. However, mindful parenting is a time-intensive intervention, and future research could investigate alternative methods of delivery to reduce the demands placed on parents and limit time spent travelling (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022). To increase feasibility and make mindfulness more achievable for busy parents, there may be value in short, accessible interventions with an online delivery (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). The intensity of mindfulness sessions and amount of formal practice required could also be reduced and replaced with exercises that can fit into pre-existing daily routines (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). As such, mindfulness lends itself to a transtheoretical approach to the management of stress (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn1994).

The aims of this pilot study were to: (1) investigate whether delivering the ‘Living in the Present’ curriculum (The Present Courses, 2022) to a group of parents of children with skin conditions could reduce levels of parental stress and increase parent and child quality of life (QoL); and (2) determine acceptability of a novel mindfulness-based intervention (MBI). Participation in the Living in the Present curriculum was hypothesised to reduce levels of parenting stress and improve parent and child quality of life.

Method

Design

This study used mixed methods, including a single case experimental design (SCED) and qualitative exit interviews subjected to thematic analysis. SCED was used as the study examined a small group of parents over a set period, and measured target outcomes across each phase (Krasny-Pacini and Evans, Reference Krasny-Pacini and Evans2018; Morley, Reference Morley2018). By gathering and analysing data from a baseline period, SCEDs repeatedly measure behaviour in the presence and absence of an intervention, with each participant acting as their own control (Krasny-Pacini and Evans, Reference Krasny-Pacini and Evans2018). SCEDs make it possible to gather high-quality data with small populations to assess an intervention’s effectiveness using patient demographics rather than clinical impressions to guide practice (Krasny-Pacini and Evans, Reference Krasny-Pacini and Evans2018; Morley, Reference Morley2018). Studies piloting novel interventions with ‘atypical cases’ (i.e. samples who are not the intended targets) can benefit from this (Krasny-Pacini and Evans, Reference Krasny-Pacini and Evans2018; Morley, Reference Morley2018). SCED have been used previously to investigate mindful parenting for parents of children with skin conditions (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for adults with alopecia (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Cockayne and Thompson2023).

The SCED was an ‘A-B-A’ design, where phase ‘A’ was a 1-week baseline period, phase ‘B’ was an 8-session intervention delivered over 10 weeks, and phase ‘A’ consisted of a 1-week follow-up period (Morley, Reference Morley2018). The main outcome variable was a bespoke measure of parental stress related to parenting a child with a skin condition (Morley, Reference Morley2018). The criteria used to determine feasibility and acceptability was based on parental measures of stress and quality of life, including the suitability of measures, recruitment strategy, attendance/attrition, combined with qualitative questions surrounding how they interacted with the intervention (Sekhon et al., Reference Sekhon, Cartwright and Francis2017).

Participants

An advertisement was posted on social media. Ten parents took part in the intervention and completed study measures (Table 1). Of these parents, n=8 of their children (when aged 4 years or over) completed QoL measures. The mindfulness teacher (n=1) also took part in a qualitative exit interview.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants

Inclusion criteria

Parents were required to be over 18 years old and carer to a child (under 16 years), diagnosed with a skin condition. Children were required to be under 16 years and diagnosed with a skin condition.

Measures

Idiographic parental targets or goals

Parents identified one positive target (aspect related to parenting a child with a skin condition they wanted to improve) and one negative target (aspect related to parenting a child with a skin condition they wanted to reduce). Idiographic measures were the primary outcome variable and were collected via text message four times per week. An example text message was as follows:

Dear *Parent’s name*,

1. How much success have you had today with feeling calmer about *Child’s name* playing in sand, water, playing on grass, swimming, or visiting dusty environments?

2. How much stress did you feel today when asking *Child’s name* to stop scratching?

Please respond to each question on a scale from 0 to 100, with ‘0’ being ‘not at all’ and ‘100’ being ‘extremely frequently’. When replying please indicate question numbers (e.g. ‘Q1=75’, ‘Q2=55’).

Standardised measures

Parents provided demographic information including age, gender, ethnicity, geographic location, employment status, the type of skin condition their child had been diagnosed with, and the length of time they had experienced symptoms. Secondary outcomes included self-reported measures of mindfulness, parental stress, parental depression, parental anxiety, parental quality of life, and child quality of life (where the child was old enough) at four time points (baseline, pre-intervention, post-intervention, follow-up). The questionnaires were sent to participants at each time point and took approximately 15 minutes to complete via Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com; Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Intervention acceptability and feasibility was assessed with qualitative exit interviews.

The Interpersonal Mindfulness in Parenting scale (IEM-P; Duncan, Reference Duncan2007) was used to measure levels of parental mindfulness. The IEM-P assesses components of parent and child relationships on a 5-point Likert scale with 10 items across several factors in parenting, including ‘present-centered attention’, ‘present-centered emotional awareness’, ‘non-reactivity’, and ‘non-judgment’ (Duncan, Reference Duncan2007; Moreira and Canavarro, Reference Moreira and Canavarro2017). The Family Dermatology Life Quality Index (FDLQI: Basra et al.; Reference Basra, Sue-Ho and Finlay2007; Basra and Finlay, Reference Basra and Finlay2005; Basra and Finlay, Reference Basra and Finlay2007) was used to measure parental quality of life on a 4-point Likert scale with 10 items assessing the psychosocial impact and physical impact of a family member’s skin condition. The Parenting Stress Index 4-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, Reference Abidin1995) was used to measure parental stress across 36 items on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g. parental distress, parent–child interactions, child difficulty) (Abidin, Reference Abidin2012). The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams1999) was used to measure depression. The PHQ-9 consists of nine items assessing symptoms of depression corresponding with diagnostic criteria (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams1999). The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) consists of seven items to assess and screen for symptoms related to generalised anxiety disorder and was used to measure levels of anxiety in parents.

Child quality of life was assessed on a 4-point Likert scale using the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI: Lewis-Jones and Finlay, Reference Lewis-Jones and Finlay1995) (validated for children aged 4–16 years) with 10 items relating to the impact of a child’s skin condition on quality of life across several areas (e.g. schooling, holidays, treatment, sleep).

Finally, as one of the aims of this study was to determine acceptability of a novel mindfulness-based intervention, qualitative exit interviews were held with each parent individually after they had completed the Present curriculum. The mindfulness teacher who delivered the Present curriculum was also interviewed separately to allow for a richer discussion surrounding their observations as the group facilitator in terms of engagement from parents. The Elliott et al. (Reference Elliott, Slatick, Urman, Frommer and Rennie2001) Client Change was used to guide conversation towards assessing personal changes, and questions were modified to the context of parenting a child with a skin condition. All exit interviews were held online and lasted one hour. Participants were debriefed at the end of every interview; discussions were recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

Procedure

Registration

Upon registration, participants were asked to disclose if they had any significant or stressful life events, physical, or mental health conditions that might impact their ability to take part in the exercises. If any concerns were raised, the mindfulness teacher would meet with each parent to discuss their participation.

‘Living in the Present’

‘Living in the Present’ is a novel mindfulness curriculum developed for adults, based on mindfulness-based stress reduction and MBCT (The Present Courses, 2022; see Supplementary material). The Present introduces mindfulness into daily life and allows participants the flexibility to choose how they learn, as opposed to traditional MBIs that demand timed personal practices (The Present Courses, 2022). This curriculum was chosen to pilot with parents of children with skin conditions, as previous research has highlighted the daily pressures of care, which could make allocating time for personal mindfulness practice difficult and affect engagement (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). Therefore, introducing mindfulness through daily activities might make the intervention more achievable.

The course was led by an external, qualified mindfulness practitioner, trained to teach the Present by one of the intervention co-founders. Teaching costs were funded by a skin-related charity to cover delivery and fidelity checks (The Ichthyosis Support Group; https://www.ichthyosis.org.uk). The course was delivered online (via Zoom; Zoom Video Communications Inc., 2023) in eight group sessions over a period of 10 weeks (due to teacher availability), with each session lasting 1.5 hours (Thursday evenings, 19.00– 20.30 h GMT). Parents were given the option of attending with partners but were free to attend alone if preferred.

Data analysis

Data analysis was led by a White, British Female (O.H.) with training from an experienced research team with experience in qualitative research, single case design, and mixed methods (A.R.T., K.S., H.P.).

Responses to the idiographic measures gathered on four occasions each week were assessed with graphical representations of data from the baseline and intervention phases. Using Microsoft Excel, the researcher visually assessed parents’ data collected with text messages to identify any trends in variation (Morley, Reference Morley2018). Tau-U is used for single case designs to examine data non-overlap in idiographic measures between intervention phases, with the following online programme: http://www.singlecaseresearch.org/calculators/tau-u (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Vannest, Davis and Sauber2011; Vannest et al., Reference Vannest, Parker, Gonen and Adiguzel2016).

Parental stress (PSI-SF), mindful parenting (IEM-P), parental quality of life (FDLQI), child quality of life (CDLQI), anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) were assessed with standardised measures; and Jacobson’s reliable change index (Jacobson and Traux, Reference Jacobson and Traux1991; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Roberts, Berns and McGlinchey1999) was used to determine if there had been any improvement or deterioration between study phases (baseline, pre-intervention, post-intervention, follow-up). Jacobson’s reliable change index was calculated using the ‘Leeds Reliable Change Calculator’ (Morley and Dowzer, Reference Morley and Dowzer2014), which assesses whether change is reliable or due to the degree of error in the measuring tool.

Qualitative data were analysed using NVivo 12 (released March 2018; https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home) and descriptive thematic analysis (Joffe, Reference Joffe, Harper and Thompson2012). The analysis allowed the consideration of existing research investigating the psychological impact of skin conditions, whilst accommodating new insights as to how a novel MBI could reduce the burden on families (Joffe, Reference Joffe, Harper and Thompson2012). Data were first coded with a line-by-line analysis, followed by complete coding of the entire dataset. Common patterns were identified, compared, and organised into themes.

Results

Attendance

Nine parents attended session one (S1: 90%), eight parents S2 and S3 (80%), nine parents S4 (90%), eight parents S5 (80%), nine parents S6 (90%), six parents S7 (60%), and eight parents attended S8 (80%). One parent could not stay for the duration of every session because of family and treatment responsibilities, but still attended (approximately 30–45 minutes).

Idiographic measures

Visual analysis

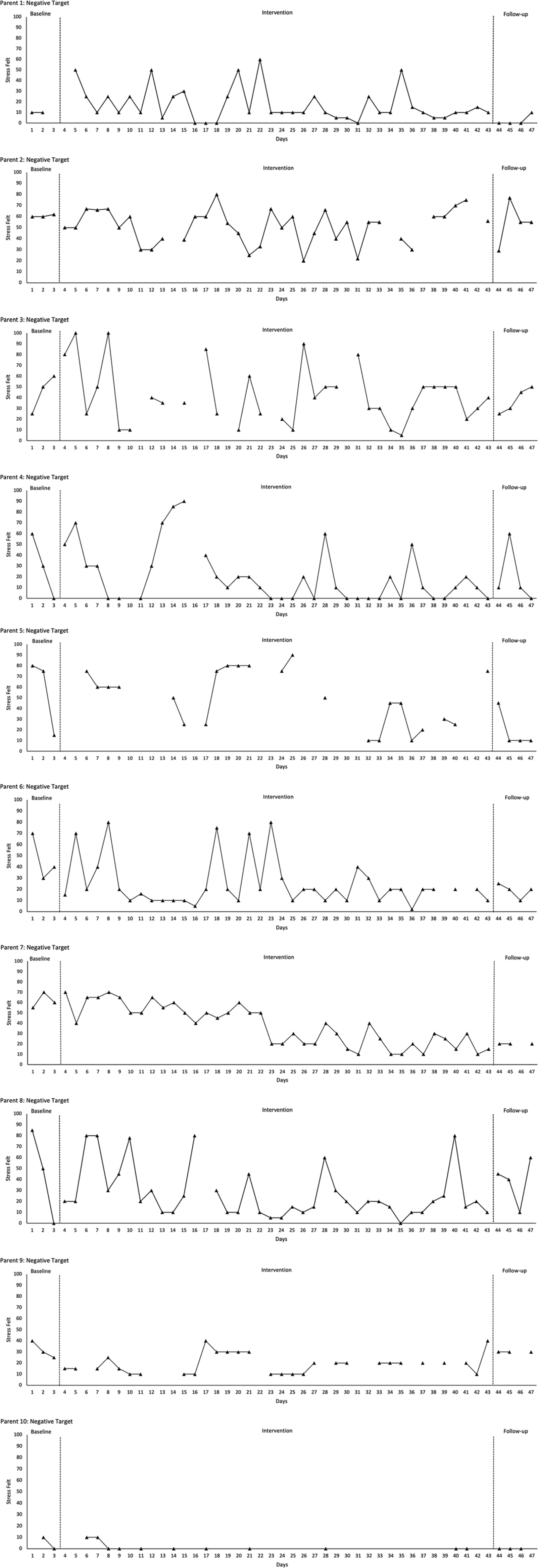

Data from each individual parent’s idiographic measure can be seen in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. There was variability in positive-framed parent scores across all intervention phases. Six parents (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8) showed upward trends in their levels of success related to parenting their child during the intervention period. However, half of the parents (1, 3, 5, 6, 8) showed baseline trends before the intervention phase began. Three parents (1, 7, 9) showed a stable trend across the intervention period. Two parents continued to show an upward trend in improvement at follow-up (5, 6), and five parents remained stable (1, 3, 4, 7, 9). Two parents (2, 8) showed downward trends at follow-up. One parent (10) scored 0 for most of the intervention phases and did not report any improvements, but demonstrated a floor effect across the baseline period, intervention and at follow-up. There was variability in negative-framed parent scores across all intervention phases. One parent (3) showed an upward trend at baseline. Eight parents (1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10) showed downward trends for their levels of parenting stress during the intervention phase. One parent (2) remained stable across the intervention phase. However, one parent (9) showed a slight upward trend across the intervention phase. Three parents continued to show downward trends at follow-up (4, 5, 6). Two parents remained stable at follow-up (7, 9). However, four parents (1, 2, 3, 8) showed upward trends at follow-up.

Figure 1. Positive targets: scores for success-framed idiographic parenting stress questions. Higher scores indicate greater success had (0–100).

Figure 2. Negative targets: scores for stress-framed idiographic parenting stress questions. Higher scores indicate greater stress felt (0–100).

Tau-U analysis

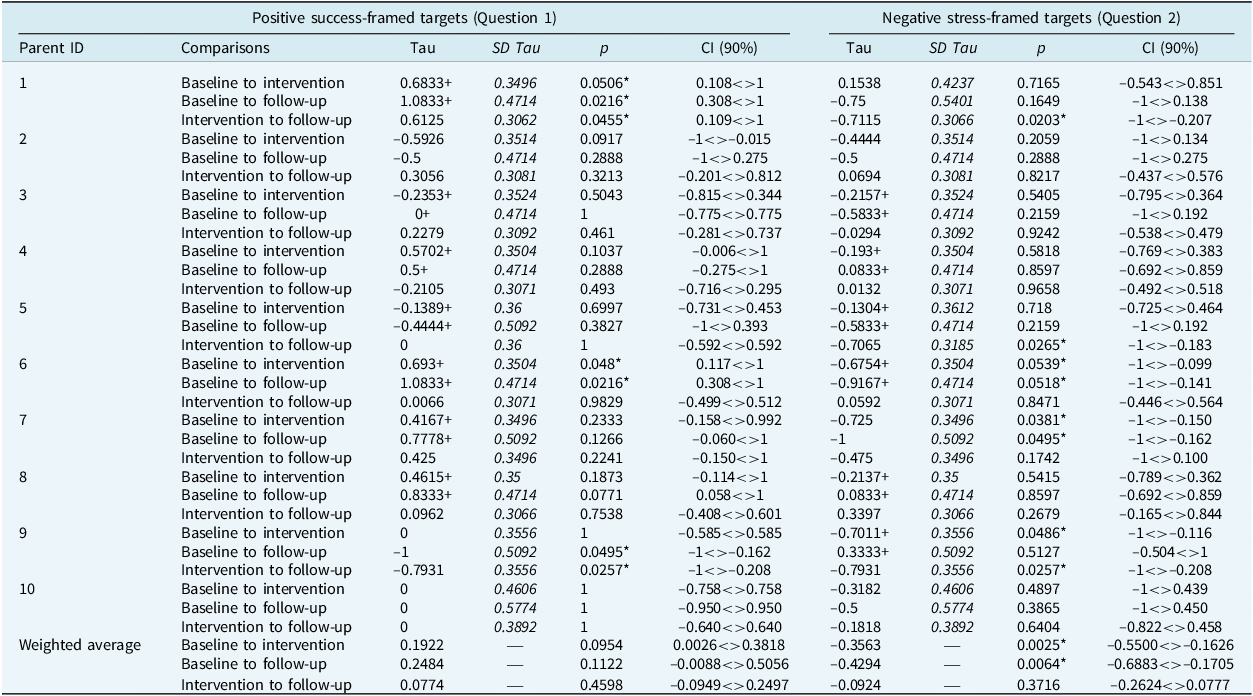

After visual analysis, baseline trends were corrected for (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Vannest, Davis and Sauber2011; Vannest et al., Reference Vannest, Parker, Gonen and Adiguzel2016) (Table 2). Three parents showed significant improvements in positive success-framed (Question 1) measures; one parent (1) showed improvement across all study phases from baseline to intervention, baseline to follow-up, and intervention to follow-up. One parent (6) showed a significant improvement from baseline to intervention, and baseline to follow-up. One parent (9) showed significant improvements from baseline to follow-up, and intervention to follow-up. There were no significant improvements in weighted averages for positive success-framed measures.

Table 2. Tau-U results for each parent participant

* Significance at p<.05; +baseline trend corrected.

Half of the parents showed significant improvements in negative stress-framed (Question 2) measures; two parents (6, 7) showed significant improvement from baseline to intervention, and baseline to follow-up. One parent (9) showed a significant improvement from baseline to intervention, and intervention to follow-up. Two parents (1, 5) showed significant improvement in stress-framed measures from intervention to follow-up only. Weighted averages showed a significant improvement for negative stress-framed measures from baseline to intervention, and baseline to follow-up.

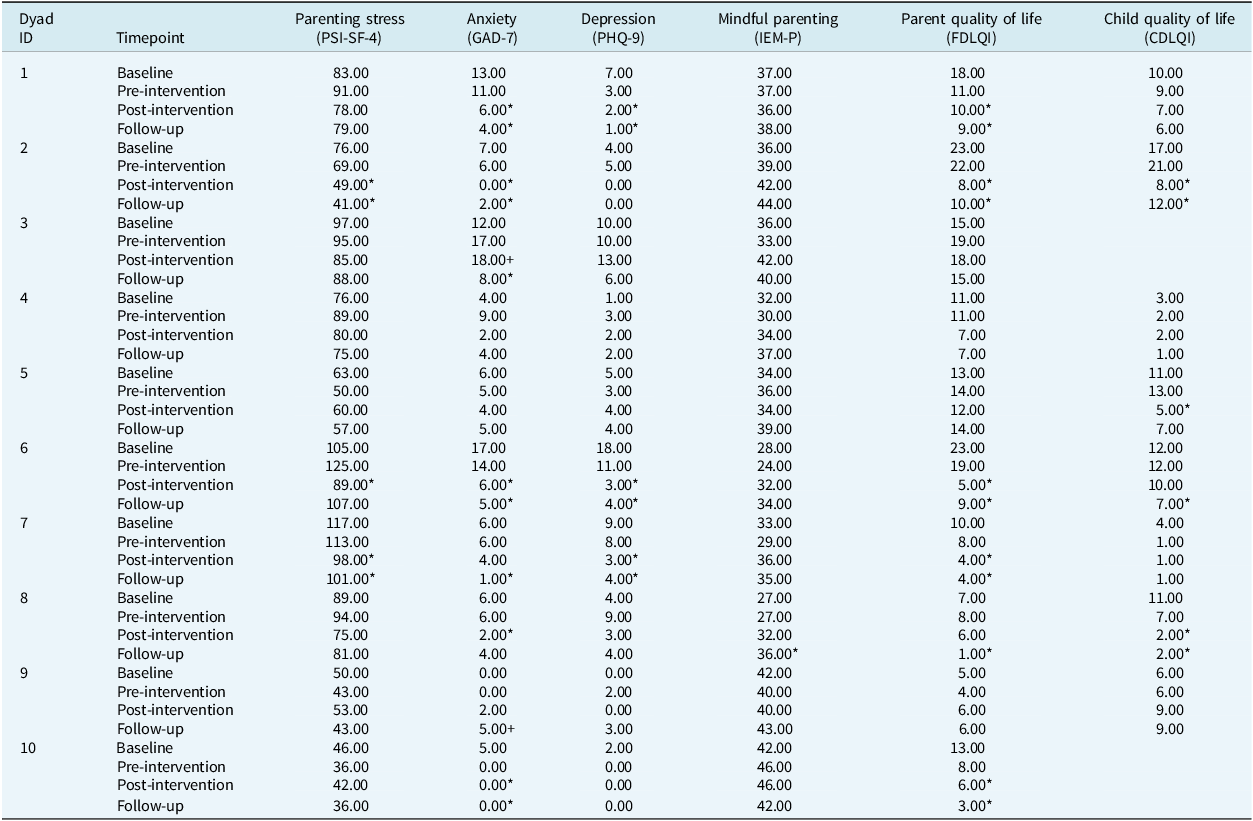

Standardised measures of QoL, stress, and mindfulness

Using the Leeds Reliable Change Calculator (Morley and Dowzer, Reference Morley and Dowzer2014), the following scores were used as clinical cut-off points to measure reliable change for standardised measures: IEM-P=9.41; PSI-SF-4=15.00; PHQ-9=6.00; GAD-7=4.00; FDLQI=6.15; CDLQI=5.08 (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022) (Table 3). Eight parents (1, 2, 3, 5, 6,7, 8) showed reliable improvement in at least one of the intervention phases. None of the parents showed improvement in mindful parenting from baseline to post-intervention, but parent 8 showed improvement at follow-up. Parents 2, 6 and 7 showed reliable improvement in parenting stress from baseline to post-intervention, and Parents 2 and 7 maintained to follow-up. Half of the parents (1, 2, 6, 8, 10) showed reliable improvements in anxiety from baseline to post-intervention. However, Parent 3 showed a reliable deterioration in anxiety from baseline to post-intervention. Six parents (1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 10) showed reliable improvements in anxiety from baseline to follow-up, and Parent 9 showed a reliable deterioration in anxiety from baseline to follow-up. Three parents (1, 6, 7) showed reliable improvements in depression from baseline to post-intervention and maintained from baseline to follow-up. Half of the parents (1, 2, 6, 7, 10) showed reliable improvements in QoL from baseline to post-intervention, and six parents (1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 10) showed reliable improvement from baseline to follow-up. Two parents (4, 9) did not show any improvements across the intervention phases.

Table 3. Scores at four time points for measures of parenting stress, anxiety, depression, mindfulness, parent quality of life, and child quality of life

* Reliable change from baseline to post-intervention, and baseline to follow-up. +Reliable deterioration from baseline to post-intervention, and baseline to follow-up. Range of questionnaire scores: PSI-SF-4 (36–180); GAD-7 (0–21); PHQ-9 (0–27); IEM-P (10–50); FDQLI (0–30); CDLQI (0–30). Higher scores indicate higher levels of parenting stress, anxiety, depression, and mindfulness. Higher scores indicate poorer parent and child quality of life.

Children 2, 5 and 8 showed reliable improvement in QoL from baseline to post-intervention, and children 2, 6 and 8 showed reliable improvement from baseline to follow-up. Children 1, 4, 7 and 9 did not show any reliable improvement across any of the intervention phases. The mean scores (out of a maximum score of 30) on impact of QoL for the entire group of children who completed questionnaires were as follows; baseline M=9.25 (moderate effect), pre-intervention M=8.88 (moderate effect), post-intervention M=5.5 (small effect), and follow-up M=5.62 (small effect).

Qualitative feedback

Three themes and seven subthemes were identified as central to describing n=9 parents’ experiences (n=1 parent could not attend the exit interview for personal reasons), and n=1 mindfulness teacher. Each theme will be discussed with supporting quotes, and pseudonyms assigned to protect participant identities. See Supplementary material for parental change ratings.

Theme 1: Noticing the benefits of mindfulness

Parents discussed observing positive outcomes in their daily lives following participation in the mindfulness course.

Shifts in parental mood and attitude

Parents described how mindfulness helped them cope more adaptively with the stresses associated with caring for their child’s skin condition:

‘I just felt more relaxed, and less stressed, and generally happier and more content.’ (Parent 3)

The mindfulness teacher also noticed visible differences:

‘The participants that attended regularly, you could visibly see less of a frenetic body language …’ (Teacher)

However, two parents described being more aware of their thoughts, as ‘a mixed blessing’ (Parent 4):

‘You’re not always going to notice happy feelings, so some things have made me a little bit down … I’ve noticed some things that I want to change … and maybe that’s a good thing because I’m being more present with myself and how I want to live.’ (Parent 8)

Two parents also reported noticing interactions with other people changing, which was seen as a positive and negative:

‘I started noticing what people were saying to me, it was like, “oh, this is nice, people are trusting me” … and then it got worse … all sorts of people were telling me all sorts of things … and I don’t know why, what changed?’ (Parent 4)

Healthier interactions with child

In some cases, parents noticed improved communication with their children:

‘I’m more mindful that I don’t want him getting upset … the communication has improved.’ (Parent 1)

‘Me and Charlie used to wind each other up and it would escalate … I can’t sit there and listen to him scratch, and he’d just keep scratching … so I’ve been trying to deal with it differently, rather than getting upset, because that then winds him up.’ (Parent 6)

Some parents described how interactions surrounding treatment had become more manageable, and they were ‘dealing with it better’ (Parent 3):

‘I now put less stress on my relationship with Evie so I don’t get as frustrated if she says no to things or she doesn’t want her medication, I try to be a bit more calm about it … I’m more mindful about our relationship.’ (Parent 7)

Theme 2: Acceptability of mindfulness exercises

Parents described how they felt about engaging in mindfulness and provided feedback on the different components of the intervention.

Bringing mindfulness into daily life

Parents discussed how they had incorporated mindful activities into everyday life, with a willingness to ‘try anything to help’ (Parent 6) their children:

‘The breathing techniques when I’m not able to get to sleep at night, because I’m thinking about what’s going on.’ (Parent 7)

‘I drive a lot to take the kids different places … so I’ve tried to just try to focus on the moment and notice what’s around me … not let my mind wander too far ahead.’ (Parent 8)

Preferences for different course components

However, opinions on mindfulness exercises were mixed; some parents did not respond well to some of the metaphors used for self-compassion:

‘There was quite a bit of stuff in there that I was kinda like “well, why?” … one of the activities was practising being more kind to more people … why do you think I’m not already kind to lots of people?’ (Parent 4)

‘The theory bit when [teacher] got in detail about the brain, some of the words I could hardly even read … I’m just not sure of the relevance.’ (Parent 5)

Suggestions for future interventions

Parents provided some useful suggestions for how mindfulness could be tailored, including reducing intensity:

‘What would have been really helpful … to have like two sessions of really quick wins, because finding an hour and a half every week is really tricky.’ (Parent 9)

Most parents favoured an online format. However, one parent described how they ‘miss body language’ (Parent 5). Importantly, another parent felt they would not have been able to participate in the intervention if it had been in-person:

‘I wouldn’t have taken part if I had to travel because of the resources, I could not have managed that with children.’ (Parent 10)

The mindfulness teacher also highlighted the benefits of online delivery:

‘We’ve got to keep it as accessible as possible … online in people’s own homes, is going to be more accessible and we couldn’t have got all these people together in a room because they’re all over the country.’ (Teacher)

Theme 3: Challenges of taking part in an intervention

Although the mindfulness sessions were generally well-received, parents highlighted barriers to participation.

Pros and cons of a group format

Most parents appreciated connecting with other parents:

‘Sitting there for a couple hours with people that were also going through something similar … because my husband doesn’t feel the same way, he doesn’t feel the burden and the worry for my son the way that I do, and to be with people that you could see that they were suffering with this, and the helplessness.’ (Parent 8)

However, some parents discussed finding it ‘hard to open up sometimes’ from feeling ‘self-conscious’ (Parent 6). Of note, one parent of a child with ichthyosis did not want to ‘burden’ other group members:

‘The other parents lives are totally different to mine, and I didn’t relate to some of them … so I didn’t share as much as I could have done, and I think it’s a very niche skin condition that my son has, and not very many people are familiar with [ichthyosis] so some of the struggles other people have are very different to what we go through as a family … you kind of guard and protect.’ (Parent 1)

Pressures of time limiting ability to immerse in mindfulness

One of the challenges faced by parents was finding time in their busy schedules to practise mindfulness, which appeared to be related to the significant burden of care:

‘I couldn’t do the full session, and an hour-long time was almost impossible in a busy life where ichthyosis does take over a lot of your time, so that was hard.’ (Parent 1)

The mindfulness teacher similarly reported one of the ‘obvious things was the difficulty of committing and attending the sessions regularly’:

‘There was quite a lot of challenge in the lives of the group, there was more than I normally would work with … so I think that perhaps had a bearing then on how much they felt they could take on.’ (Teacher)

An example of the pressures on parents was provided by one parent (3) who attributed their deterioration in anxiety as being a result of worry about their child with eczema starting nursery at the same time as the intervention:

‘We were going through a lot of changes with the nursery, so it’s been quite a stressful time for us … that’s not a reflection on the course.’ (Parent 3)

Treatment fidelity

Treatment fidelity was assessed with a modified version of the MBI fidelity checking tool (Kechter et al., Reference Kechter, Amaro and Black2019) adapted from the Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium (BCC) guidelines (Bellg et al., Reference Bellg, Borrelli, Resnick, Hecht, Minicucci, Ory, Ogedegbe, Orwig, Ernst and Czajkowski2004; Resnick et al., Reference Resnick, Bellg, Borrelli, Defrancesco, Breger, Hecht, Sharp, Levesque, Orwig, Ernst, Ogedegbe and Czajkowski2005). Two sessions were audio recorded and reviewed by one of the Present co-founders. Consensus was reached that the curriculum was being delivered as per protocol and met the requirements to confirm fidelity.

Discussion

This was a single case series investigation of the ‘Living in the Present’ mindfulness intervention with parents of children with skin conditions. Analysis of parental bespoke measures revealed three parents showed some significant improvements in positive success-framed measures, and half of the parents showed some significant improvements in negative stress-framed measures. For the standardised measures of QoL, eight parents and four children showed reliable improvements in at least one phase of the intervention. After completing the intervention, there were some improvements to children’s dermatology-related quality of life, and several parents reported improved outcomes in their children. For example, many parents found communication had improved, and there was less stress within the family unit from parents responding differently to situations (Albers et al., Reference Albers, Riksen-Walraven, Sweep and de Weerth2008; Portnoy et al., Reference Portnoy, Korchak, Foxall and Hurlston2023; Ruskin et al., Reference Ruskin, Campbell, Stinson and Ahola Kohut2018). For parents who noticed these changes, there was an increased sense of calmness within the parent–child relationship and less distress arising from the pressures of treatment (Albers et al., Reference Albers, Riksen-Walraven, Sweep and de Weerth2008; Van Gampelaere et al., Reference Van Gampelaere, Luyckx, Van Ryckeghem, Van Der Straaten, Laridaen, Goethals, Casteels, Vanbesien, Den Brinker, Cools and Goubert2019), and a reduction in conflict.

Parents identified positive changes after taking part in the intervention, including feeling calmer in the immediate days following a group session, which was corroborated by the mindfulness teacher. However, several parents described the challenges of having an increased awareness of unpleasant aspects of their lives. There is evidence to suggest that some people might encounter challenges during early attempts of mindfulness and struggle with varying types of discomfort (Farias and Wilkholm, Reference Farias and Wikholm2016; Lomas et al., Reference Lomas, Cartwright, Edginton and Ridge2015). Practising mindfulness is associated with psychological flexibility (Ruskin et al., Reference Ruskin, Campbell, Stinson and Ahola Kohut2018), and the ability to separate from negative thoughts rather than being caught up in them. Despite initial difficulties, mindfulness must be practised over time to change the impact of distressing inner experiences (Lomas et al., Reference Lomas, Cartwright, Edginton and Ridge2015). Unexpectedly, parents also reported how more people were conversing with them in public. It could be possible that this was happening previously, but they were noticing it more since developing an attitude shift towards acting with more awareness. Alternatively, it could be that parents began to appear more relaxed and open to new experiences, so might have been more likely to be approached by other people.

Two parents appeared to experience increased anxiety (3, 9). Parent 3 attributed their increased anxiety scores to experiencing stress as a family at the same time as the intervention. However, Parent 9 reportedly had no anxiety at baseline or pre-intervention, which increased post-intervention and at follow-up. One explanation for this could have been from an attentional focus developing, with parents engaging in more accurate reporting of physiological symptoms (Lomas et al., Reference Lomas, Cartwright, Edginton and Ridge2015). Importantly, neither parent spoke of their anxiety because of the intervention.

In terms of acceptability, the group format was generally well-received, as has been the case in other studies (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022). However, one parent of a child with severe ichthyosis felt it was more difficult to connect with other group members as rarer symptoms were involved and found making the time to attend sessions challenging. Most parents favoured an online format for saving on travel expenditures (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022), although the disadvantage of missing body language was raised. Most parents successfully incorporated mindfulness into daily routines; however, opinions on certain exercises were mixed (e.g. metaphors vs theory components). Parents provided suggestions to improve future interventions, including a reduction in the length and number of sessions. Despite previous feedback suggesting the need for less intensive/online sessions for parents of children with skin conditions (Heapy et al., Reference Heapy, Norman, Emerson, Murphy, Bögels and Thompson2022), finding time to attend sessions and carry out practices remained a challenge for some parents. Parents lacking time to practise could explain the variation in psychological outcomes (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Harris, Lenton, Warde, Gold, Gane and Seddon2021; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Shelton, Penny and Thompson2022).

Limitations

The study sample consisting entirely of mothers limits transferability, and those who volunteered were probably highly motivated to participate. Despite this study being a pilot investigation, the baseline and follow-up periods could have been lengthened to enable greater stability and limit baseline trends, alongside hours of practice and idiographic measures being collected daily. Although this was not possible for this study due to recruitment timelines and intervention availability, collecting these additional data would allow mindfulness to be robustly investigated. Future studies might seek to purposively sample fathers, to investigate caregiver roles. Additionally, although the mindfulness teacher was briefed on the nature of typical presenting problems associated with skin conditions by the research team, and this was a pilot study adopting a transtheoretical perspective to mindfulness, there would be merit in exploring adaptation in future interventional studies (e.g. support for skin specific issues and heightened distress).

Conclusion

The Living in the Present mindfulness curriculum has shown potential as an effective intervention for parents of children with skin conditions and could be feasible for reducing stress and improving QoL. However, it is important to remember the findings represent one curriculum, making it difficult to determine the efficacy of mindfulness for parents of children with skin conditions. MBIs require further intensive research with large sample sizes and control groups to robustly investigate outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465824000341

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (O.H.). The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of study participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mandy Aldwin-Easton, Liz Dale, and the Board of Trustees of the Ichthyosis Support Group for funding this research project and assisting with recruitment. Our sincere thanks to Tim Anfield and Sarah Silverton for supporting this study. We would also like to thank the British Skin Foundation, the Psoriasis Association, the Vitiligo Society, Patient Worthy, Beacon for Rare Diseases, HealthTalk.org, FIRST Foundation for Ichthyosis, the Ectodermal Dysplasia Society, Skin Care Cymru, the Eczema Society, and the Mindfulness Project for helping with recruitment.

Author contributions

Olivia Hughes: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Katherine Shelton: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Helen Penny: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Andrew Thompson: Conceptualization (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

Completed in partial fulfilment of a PhD studentship funded by Cardiff University School of Psychology and Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW). This research was supported by the Ichthyosis Support Group to fund the mindfulness teacher costs for delivering the intervention and fidelity checks.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was granted by Cardiff University (EC.22.04.26.6558RA3). The authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. All participants provided informed consent to participate in this research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.