1. Introduction

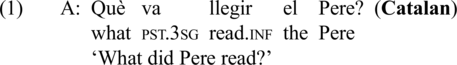

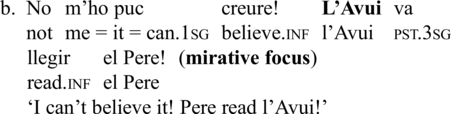

Cross-linguistic and comparative studies have shown that the pragmatic interpretation associated with narrow focus is an essential factor for its syntactic distribution. In null-subject Romance languages like Catalan, Spanish and Italian, the focus of the sentence is typically placed after the verb; however, focus fronting (FF) to a preverbal, left-peripheral position is possible when the narrow focus is associated with a corrective/contrastive or with a mirative interpretation, as illustrated by the contrast of acceptability between Example (1C), on the one hand, and Example (2a–2b), on the other (see, e.g. Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1998, López Reference López2009, Cruschina Reference Cruschina2021 and references therein).

The corrective focus in Example (2a) operates over a previous statement, correcting a focal alternative that is explicitly present in the immediate discourse. With mirative focus (cf. Example 2b), the set of focal alternatives evoked by narrow focus is pragmatically exploited in terms of a speaker’s expectations: the asserted proposition is presented as being more unlikely (and hence surprising) with respect to other alternative propositions; mirative focus can thus be defined as focus against expectations.

In most null-subject Romance languages, the availability of FF with corrective focus has long been recognized – more generally under the label of contrastive focus (see, e.g. Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997, López Reference López2009). The investigation into mirative focus is more recent (Cruschina Reference Cruschina2012), but the possibility of having FF with this pragmatic type of focus does not seem to be the subject of controversy (see Ledgeway Reference Ledgeway and Pescarini2009, Jones Reference Jones2013, Cruschina et al. Reference Cruschina, Giurgea and Remberger2015, Jiménez-Fernández Reference Jiménez-Fernández2015a Reference Jiménez-Fernández,b, Giurgea Reference Giurgea2016, and Cruschina Reference Cruschina2019, Reference Cruschina2021, Reference Cruschina and Aronoff2022a; see also other studies that do not use the term mirative but that do make reference to an interpretation of surprise and unexpectedness: Vallduví Reference Vallduví1992, Reference Vallduví and Kiss1995, Brunetti Reference Brunetti2004, Reference Brunetti, Dufter and Jacob2009, Paoli Reference Paoli, D’Alessandro, Ledgeway and Roberts2010 for Romance varieties, and Krifka Reference Krifka1995, Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann, Féry, Fanselow and Krifka2007, Reference Zimmermann2008, Hartmann & Zimmermann Reference Hartmann, Zimmermann, Schwabe and Winkler2007, Frey Reference Frey2010, Trotzke Reference Trotzke2017 for other languages).

Interestingly, it is with the type of narrow focus that is considered to be neutral or unmarked from a pragmatic viewpoint that the judgements reported in the literature about the availability of FF are more controversial. This is the case of information focus, which can be defined as the type of focus that introduces new information and gives rise to a contextually open set of alternatives. Information focus does not involve a direct contrast, either with a given alternative, as with corrective focus, or with more likely alternatives, as with mirative focus.

The controversies revolving around the syntactic distribution of information focus seem to mostly depend on the adopted methodology. On the one hand, work relying on the authors’ own intuitions claims that narrow focus must occur postverbally or sentence-finally, irrespective of its syntactic category. On the other hand, studies based on a quantitative method have shown that information focus can occur preverbally and is indeed accepted in this position. However, it has been pointed out that both lines of investigation, especially the latter, suffer from a number of methodological shortcomings related to the elicitation of information focus (Uth Reference Uth2014, Escandell Vidal & Leonetti Reference Escandell Vidal, Leonetti, Ruiz, Moreno and Lamas2019, Cruschina Reference Cruschina2021). To overcome these methodological problems, Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022) propose a new technique that aims to enhance the naturalness and reliability of elicited data with information focus: Questions with a Delayed Answer (QDA). This technique is based on the question-answer test to elicit information focus and is presented as an improvement of the Discourse Completion Task used in prosodic studies on the Romance languages (see Vanrell et al. Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Fliessbach and del Mar Vanrell2018). With QDA, some material is inserted between the question and the point in which the participant is asked to answer the question; because of this (short) distance, participants would spontaneously reply to the question with a full sentence instead of a fragment, which would otherwise be the most natural answer to a wh-question.

Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022) implemented QDA in both a production and an acceptability-judgement experiment on Catalan. In this paper, we expand our investigation in a comparative direction, reproducing these experiments in Spanish and in Italian with the same experimental design and material, modulo the language of the stimuli. The results are very similar in all three null-subject Romance languages, especially in the production experiments, and support the more traditional view of the postverbal placement of information focus. At the same time, however, the results of the acceptability-judgement experiments show that the distribution of information focus is not unequivocal and clear-cut. Information focus is indeed accepted in a preverbal position, although to a lesser extent than postverbal information focus and to varying degrees across the three Romance languages under investigation.

After a review of the methodological problems related to the elicitation of information focus in Section 2, in Section 3, we will present the solutions adopted by Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022), which are at the basis of all the experiments reported here. The experiments will be described in Sections 4 and 5. For comparative purposes, and for ease of exposition, we will present the experiments reported in Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022) on Catalan together with the experiments on Spanish and Italian, which are original to this paper, starting with the production experiments (Section 4) and then moving to the acceptability-judgement experiments (Section 5). In Section 6, we will then try to explain the differences across the three languages in the light of the hypothesis formulated in Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017), according to which Catalan and especially Italian are more restrictive than Spanish with respect to the mapping between syntax and information structure.

2. The Elicitation of Information Focus

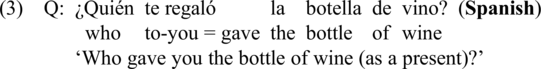

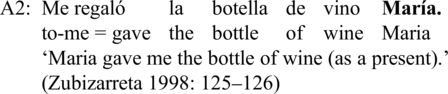

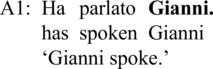

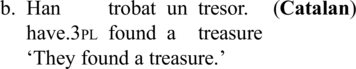

The first studies on the syntactic distribution of information focus were based on introspection, that is, on the intuitions and grammaticality judgements of the authors. According to these studies, in non-null subject Romance languages, information focus – often just called focus or non-contrastive focus – must occur in a postverbal position (see, e.g. Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1998, Ordóñez Reference Ordóñez2000, Büring & Gutiérrez-Bravo Reference Büring, Gutiérrez-Bravo and Bhloscaidh2001, Gutiérrez-Bravo Reference Gutiérrez-Bravo2006, Reference Gutiérrez-Bravo2008 on Spanish; Vallduví Reference Vallduví, Lorente, Alturo, Boix, Lloret and Payrató2001, Reference Vallduví, Solà, Lloret, Mascaró and Pérez-Saldanya2002, López Reference López2009 on Catalan; Benincà Reference Benincà and Renzi1988, Belletti & Shlonsky Reference Belletti and Shlonsky1995, Belletti Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004, Reference Belletti2009 on Italian). The syntactic effects of the postverbal placement of the focus are opaque in the case of focal direct objects since they would independently occur in a postverbal position but are more tangible with focal subjects that undergo subject inversion, as shown in Examples (3) and (4) for Spanish and Italian, respectively:Footnote 1

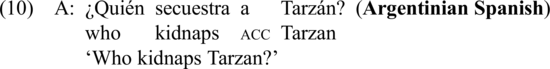

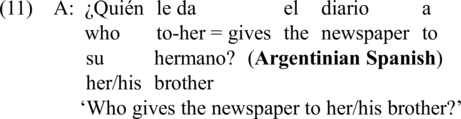

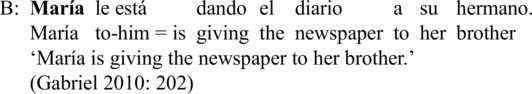

These data, however, have been challenged and disputed in a series of studies that have adopted a different methodology characterized by the use, increasingly common among linguists, of quantitative methods to provide insights into linguistic data and phenomena. With some exceptions,Footnote 2 most of these studies have reported a different view on the availability of FF with information focus, especially with respect to the position of the focal subjects (see Gabriel Reference Gabriel2010, Hoot Reference Hoot2012, Reference Hoot2016, Vanrell & Fernández-Soriano Reference Vanrell and Fernández-Soriano2013, Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Fliessbach and del Mar Vanrell2018, Jiménez-Fernández Reference Jiménez-Fernández2015a, Reference Jiménez-Fernández2015b, Leal et al. Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018; see Heidinger Reference Heidinger, Leonetti and Escandell-Vidal2021, Reference Heidinger2022 for a detailed overview on Spanish, and Frascarelli & Stortini Reference Frascarelli and Stortini2019 on Italian). This has led to the growth of contrasting views in the relevant literature that have been described in terms of a tension related to the source of the data: introspection versus quantitative analysis (see Uth & García García Reference Uth, García, García and Uth2018, Hoot & Leal Reference Hoot and Leal2020, Hoot et al. Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020, Cruschina Reference Cruschina2021, Heidinger Reference Heidinger2022).

This tension has been particularly noticeable in Spanish. Indeed, most quantitative studies on the syntactic distribution of information focus are on Spanish; some also deal with Catalan (e.g. Feldhausen & Vanrell Reference Feldhausen, del Mar Vanrell, Fuchs, Grice, Hermes, Lancia and Mücke2014, Vanrell & Fernández-Soriano Reference Vanrell and Fernández-Soriano2013); and a few are on Italian (e.g. Frascarelli & Stortini Reference Frascarelli and Stortini2019, Frascarelli et al. Reference Mara, Carella, Casentini, Balsemin, Caloi, Garzonio, Lamoure, Pinzin and Sanfelici2022, Ylinärä et al. Reference Ylinärä, Carella and Frascarelli2023). This may be due to an important difference between the languages, that is, the fact that in Spanish, the mapping between syntax and information structure is less transparent than in Italian and in Catalan. In this respect, Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) points out that in Spanish, the same order is compatible with different interpretations and focus readings, while in Italian and in Catalan, the mapping between syntax and information structure is more straightforward and univocal. On the basis of this difference, Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) defines Romance languages like Spanish as ‘permissive’, while Italian and Catalan fall within the group of the ‘restrictive’ Romance languages. As will be discussed in Section 6, our experimental results confirm this distinction.

The challenges and the tension brought by the quantitative studies have also to be viewed in relation to certain methodological tendencies and issues. On the one hand, the experimental and quantitative work in the investigation of the syntactic position of focus has been a natural reaction to the increasing interest in and tendency towards more natural data, moving away from the initial tendency of generative syntacticians to analyse idealized data that are exclusively based on the evidence of a single person’s judgements and generalized to a whole community of speakers. This new approach, whereby the empirical basis of the syntactic work is considered more carefully, has resulted not only in the adoption of quantitative methods of investigation but also in the special attention to different types of speakers identified by factors such as dialectal variation, bilingualism and acquisitional differences (see Muntendam Reference Muntendam2009, Reference Muntendam2013, Hoot Reference Hoot2012, Reference Hoot2016, Jiménez-Fernández Reference Jiménez-Fernández2015a Reference Jiménez-Fernández,b, Leal et al. Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018, Uth Reference Uth, García and Uth2018, Sánchez-Alvarado Reference Sánchez-Alvarado2018, Frascarelli & Stortini Reference Frascarelli and Stortini2019, Hoot & Leal Reference Hoot and Leal2020). On the other hand, quantitative methods, and the experimental design in particular, require a controlled study: the number of conditions, the elicitation technique or task, the nature of the stimuli, the annotation and coding of the results and the presence of possible confounding variables are all aspects of the experimental method that have to be defined very carefully. So, the use of more data, speakers and contexts in the search for more reliable results, which overtly contrasts with the direct introspection method, may end up adding levels of complexity that may ultimately make the data difficult to interpret and analyse unequivocally.

Based on these considerations, we believe that the experimental method is definitely worth pursuing, but it needs scrupulous reflections and a careful design. With the help of the QDA technique in our production and rating experiments, we will show that the discrepancies between introspection and experimental studies are the result of several factors, such as the distinction between production and rating, the specific methodological solutions adopted in the experimental studies and the gradience of the judgements. On the one hand, our experimental results point to a very strong preference for postverbal foci in production when only one option is generally produced. These results confirm the more traditional view coming from the introspection of individual scholars; we attribute the differences with the previous experimental studies to possible methodological shortcomings (cf. Section 2.1). On the other hand, the results of our grammaticality-judgement experiment, based on a rating task, point towards a certain degree of optionality and variation. The data from the rating experiment show that the strong preference to place the information focus postverbally does not imply the total exclusion of the preverbal option. Preverbal foci may also be accepted, even though this acceptability depends on the grammatical category of the focus and is subject to variation across the three languages. The gradience of the acceptability judgements is better reflected in the experimental studies rather than in the introspection analyses, especially in the case of Spanish. We will relate the language-specific variation to the distinction between restrictive and permissive languages (cf. Section 6).

In the next section, we review some of the methodological problems or controversial aspects that can be identified in the quantitative studies on the syntactic distribution of information focus. But before moving to this section, we would like to clarify and justify our terminological choices. Following a cartographic perspective, we assume that focalization always involves movement to a dedicated functional projection and that both preverbal focal objects and subjects are syntactically fronted to the left periphery of the sentence (i.e. in Spec/Foc, Rizzi Reference Rizzi and Haegeman1997; see Bocci Reference Bocci2013, Feldhausen & Vanrell Reference Feldhausen, del Mar Vanrell, Fuchs, Grice, Hermes, Lancia and Mücke2014, Reference Feldhausen and del Mar Vanrell2015, Hoot Reference Hoot2016 for evidence and discussion). Along the same lines, we assume that postverbal foci (vacuously) move to a dedicated focus projection in the left periphery of the vP, as proposed in Belletti (Reference Belletti and Rizzi2004). However, since these assumptions are not directly relevant for the purposes of this paper, and for the sake of simplicity and terminological consistency, in the discussion of the experimental conditions and results, we will use the descriptive term ‘preverbal’ to refer to all fronted foci. Similarly, we will use the descriptive term ‘postverbal’ to refer to foci that occur after the verb.

We are aware that the terms ‘preverbal’ and the ‘postverbal’ are not equivalent for subject and object foci, both from a syntactic and a pragmatic viewpoint. Preverbal focal objects appear in a prominent position, which involves a rearrangement of the word order. Preverbal focal subjects, by contrast, occur in a position that coincides with the basic order of the constituents – this is why preverbal focal subjects are often called ‘subjects in situ’ in other studies. For a subject, it is rather postverbal focalization that makes it more prominent and that requires the rearrangement of the sentential word order. This is certainly an important difference to bear in mind, but at the same time, it must be clear that we simply use the labels ‘postverbal focus’ and ‘preverbal focus’ to make reference to the linear position with respect to the verb, in a pre-theoretical fashion and independently of markedness considerations.

2.1. The question-answer test

Since a wh-question asks for new information (canonical questions at least do so; see Farkas Reference Farkas2020), the question-answer test has been used as the classical method to elicit information focus. Indeed, in crosslinguistic research ‘wh questions and their answers are the most widespread and most widely accepted test for focus’ (van der Wal Reference van der Wal2016: 265). This test relies on the assumption that the focus constituent in the answer corresponds to the wh-phrase in the question. The validity of this test is supported by semantic and prosodic analyses of focus (Paul [1880] Reference Paul1995, Halliday Reference Halliday1967, von Stechow Reference von Stechow and Abraham1990, Roberts [1996/1998], Reference Roberts2012, Schwarzschild Reference Schwarzschild1999, Krifka Reference Krifka, Féry and Sternefeld2001, Reference Krifka, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011, Reich Reference Reich2002, and Zimmermann & Onea Reference Zimmermann and Onea2011, among others); however, it should be handled with care when studying the syntax of information focus. Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022: Section 2) identify a number of potential problems of this test related to the following three empirical observations:

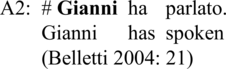

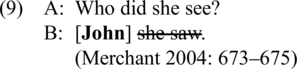

First of all, in line with the generalization in (5a), the question-answer test must be limited to congruent answers where the focus is the part of the answer that directly corresponds to the wh-phrase in the question, and the background in the answer is the same as the background in the question (see, e.g. von Stechow Reference von Stechow and Abraham1990, Krifka Reference Krifka, Féry and Sternefeld2001, Reference Krifka, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011, Reich Reference Reich2002). This restriction is needed to guarantee a narrow focus interpretation of the new part of the answer to a wh-question. Suppose the goal of the test is to elicit information focus, therefore, pragmatically felicitous but incongruent answers should be excluded because they do not necessarily feature a narrow focus, as in Examples (6)–(8) (from Cruschina & Mayol Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022: Section 2.1):

The answer in Example (6B) clearly addresses and resolves the issue opened in the question (Example 6A), but it is not a congruent answer because the DP an Italian clothing company does not directly correspond to the wh-constituent of the question and, thus, it does not count as a narrow focus. In the reply (Example 7B), the constituent John roughly corresponds to the wh-constituent of the question (Example 7A), providing the missing information. However, there is no full congruence between the question and the answer since Who in the question and John in the answer have different syntactic functions within their respective sentence, and the background of the reply does not match that of the question. In addition, if John in Example (7B) were prosodically marked as focus, the answer would not qualify as a felicitous answer. Let us finally consider the answer in Example (8B). Not only is this an appropriate and felicitous reply to the question in Example (8A), but we also have a direct correspondence between the wh-phrase in the question (Who) and the constituent in the answer that provides the missing information (John). As a matter of fact, however, the constituent John in Example (8B) is not a narrow focus but a contrastive topic in the sense of Büring (Reference Büring1997, Reference Büring2003, Reference Büring, Féry and Ishihara2016). Unlike focus, contrastive topic does not imply the exclusion of alternatives but suggests a continuation with reference to the other members of the set (John went to Siena, Mary went to Padua, Paul went to Venice, etc.), thus proving a partial answer to the question (Krifka Reference Krifka, Féry, Fanselow and Krifka2007). Contrastive topic is also prosodically different from focus, being marked by a specific pitch accent (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1972, Büring Reference Büring1997, Reference Büring2003).Footnote 3

In the analysis of information focus and in the discussion of the results, most of the quantitative studies do not contain sufficient details to fully understand if the data were selected or classified to take the congruence requirement of the question-answer test into account (but see Leal et al. Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018 and Hoot et al. Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020 for a systematic classification).

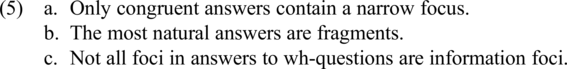

The observation in (5b) is generally recognized as a drawback of the question-answer test and has to do with the naturalness of the data. It is well-known that the most natural type of congruent answers to wh-questions are fragments (see Merchant Reference Merchant2004, Krifka Reference Krifka, Molnár and Winkler2006, among others). Fragment answers only contain the focus of the answer and feature the ellipsis of the background or given material that the fragment answer shares with the question:

Despite their naturalness, an elicited fragment is not useful in the study of the syntax of narrow focus because it makes it impossible to determine the position that information focus occupies within the sentence. In particular, it does not provide any decisive data in support or against the availability of preverbal information foci (see Brunetti Reference Brunetti2004 for an analysis of the position of information focus that encompasses ellipsis).

According to Example (5c), not all foci in answers to wh-questions are information foci. The question-answer test to elicit information focus is so common and widespread that often little attention is paid to possible methodological and/or contextual factors that might affect the interpretation of the focus in the answer. Based on previous observations by Uth (Reference Uth2014), Escandell Vidal & Leonetti (Reference Escandell Vidal, Leonetti, Ruiz, Moreno and Lamas2019: 208) and Cruschina (Reference Cruschina2021), Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022: 8) conclude that ‘the use of a focus to answer a wh-question is not per se a sufficient condition for the definition of information focus, in that not all foci in answers to questions are necessarily information foci; other types can also occur in this context’. In particular, Uth (Reference Uth2014) points out that, if images are used in a production task featuring the question-answer test, the answers may well encode a sense of obviousness or certainty that comes from the fact that the pictures illustrate the events of the questions, that is, the pictures overtly visualize the answers to the questions (see also Vanrell et al. Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Fliessbach and del Mar Vanrell2018). A picture-based elicitation task is indeed employed in most production studies on information focus (cf., e.g. Gabriel Reference Gabriel2007, Reference Gabriel2010, Vanrell & Fernández-Soriano Reference Vanrell and Fernández-Soriano2013, Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Fliessbach and del Mar Vanrell2018, Frascarelli & Stortini Reference Frascarelli and Stortini2019, Ylinärä et al. Reference Ylinärä, Carella and Frascarelli2023; see Sánchez-Alvarado Reference Sánchez-Alvarado2018 for discussion and for a different solution to this problem). A similar interpretative problem may also concern the use of video clips to guide the question-answer test, as in the production task described in Leal et al. (Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018) and Hoot et al. (Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020). These techniques featuring visual aids might have, therefore, compromised the speakers’ interpretation of the questions as genuine or canonical questions since they lack an important default assumption about canonical questions, namely, speaker ignorance, that is, the assumption that a speaker who asks a question does not know the answer (see Farkas Reference Farkas2020). Given this state of the common ground, where the speaker and the addressee of the question share the (visually presented) information about the answer, the question itself will be unexpected, and the neutrality of the answer will be undermined. In some cases, moreover, the context might have favoured a mirative interpretation of the focus in the answer and, therefore, a preverbal placement of the focus, which is indeed generally possible (see Cruschina & Mayol Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022: 8).

In an experimental study that targets a specific type of focus (e.g. information focus), it is therefore important to come up with an experimental design where the interpretation of the focus is controlled for and where special attention is paid to the possible methodological and contextual factors that might affect it.

2.2. The experimental design

Most studies on the distribution of focus have used acceptability-judgement tasks, which mainly aimed to assess the existing claims in the literature about the realization of focus. Other scholars, however, have adopted production tasks, especially when they were mostly – or additionally – interested in the prosodic realization (see Gabriel Reference Gabriel2007, Reference Gabriel2010, Feldhausen & Vanrell Reference Feldhausen, del Mar Vanrell, Fuchs, Grice, Hermes, Lancia and Mücke2014, Vanrell & Fernández-Soriano Reference Vanrell and Fernández-Soriano2013, Reference Vanrell, Fernández-Soriano, García and Uth2018, Sánchez-Alvarado Reference Sánchez-Alvarado2018, Frascarelli & Stortini Reference Frascarelli and Stortini2019; most of these studies used the discourse completion task, cf. Section 3). Even when the investigation only concerns the syntactic realization of information focus, production tasks are often considered to be preferable to acceptability judgements because they do not limit the possible responses to specific pre-determined structures chosen by the experimenters and may better reflect the speakers’ preferences in a specific context (Leal et al. Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018; see also Hoot & Leal Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020 and Hoot et al. Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020 for both production and acceptability-judgement tasks).

The subjects participating in a production task certainly have more freedom in their responses than in an acceptability-judgement experiment based on a rating task; this freedom, however, is often limited by specific instructions which, in fact, steer the answers towards less natural and spontaneous choices. This is what happens when fragment answers are being avoided (cf. 5b) because they will be irrelevant in the study of the focus position. To this end, the experimenters have often included precise instructions for the participants as to which constituents should be used in the answers; for example, the participants were explicitly asked to use complete sentences, repeating the same predicate or all constituents of the question (see, e.g. Gabriel Reference Gabriel2007, Reference Gabriel2010, Feldhausen & Vanrell Reference Feldhausen, del Mar Vanrell, Fuchs, Grice, Hermes, Lancia and Mücke2014, Vanrell & Fernández-Soriano Reference Vanrell and Fernández-Soriano2013, Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Fliessbach and del Mar Vanrell2018, Leal et al. Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018, Hoot et al. Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020):Footnote 4 , Footnote 5

These instructions not only have the drawback of hindering the most natural and spontaneous tendency to reply with a fragment, which was, in fact, a desideratum of the experimenters, but they were also inhibiting the recourse to the clitic-dislocation of the given constituents, which – with some minor differences across the Romance languages – is considered to be more or less obligatory in natural colloquial speech (see Mayol Reference Mayol2007, Cruschina Reference Cruschina2010, Reference Cruschina2022b, López Reference López2009, Villalba Reference Villalba2009, Reference Villalba2011, among others). Even when the repetition of the predicate is justified by the syntactic need of the task to determine the preverbal or postverbal position of the focus, it is known that the repeated use of given constituents may affect the realization of the focus, especially in the case of focal subjects (see, e.g. Gabriel Reference Gabriel2007, Reference Gabriel2010, Belletti & Shlonsky Reference Belletti and Shlonsky1995, Ordóñez Reference Ordóñez2000, Domínguez Reference Domínguez, Ionin, Ko and Nevins2002, Heidinger Reference Heidinger2013, Samek-Lodovici Reference Samek-Lodovici2015, Dufter & Gabriel Reference Dufter, Gabriel, Fischer and Gabriel2016, among others). The question arises of whether the participants would have produced a different order if they did not have to repeat all constituents in the question but had the freedom to resort to omission or clitic dislocation. The preverbal realization of the focal subject in the Examples (10)–(12) above could then be viewed as the consequence of a dislike for the VOS order over SVO. Note that although VOS is considered to be grammatical in Spanish (see Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1998, among others), the same order is less natural or at least controversial in Catalan and in Italian (see Belletti & Shlonsky Reference Belletti and Shlonsky1995, Ordóñez Reference Ordóñez2000, Gupton Reference Gupton, Lauchlan and Couto2017, Leonetti Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017; cf. also Section 6).Footnote 6 A comparison with different word orders and dislocation strategies would certainly be interesting, but at the same time, in an experiment that aims to investigate the distribution of focus, it would imply the addition of further complexity, a move that is not always desirable. This leads us to the next question about the design of the experiments: the experimental conditions.

In the research on the placement of focal constituents, the number of relevant factors is potentially high; depending on the original research hypotheses, these factors may include the syntactic category (subject, direct object, indirect object, adjunct), the type of verb (transitive, intransitive, unaccusative), or the lexical-semantic properties of the verb (e.g. motion, change of state, inherently reflexive, etc.) (cf., e.g. Frascarelli & Stortini Reference Frascarelli and Stortini2019, Frascarelli et al. Reference Mara, Carella, Casentini, Balsemin, Caloi, Garzonio, Lamoure, Pinzin and Sanfelici2022, Ylinärä et al. Reference Ylinärä, Carella and Frascarelli2023). One possible additional factor is the presence or the realization of other constituents, as we saw above, in relation to the position of focal subjects (cf. Examples (10)–(12)). We are aware that all these factors can play an important role in the distribution of focus, but we also believe that many factors can introduce complexity in the interpretation of the results and in the classification of the data for the analysis. To facilitate the interpretation of the data, we therefore decided to use the QDA technique in combination with an experimental design that involves a limited number of factors and conditions (cf. Sections 4 and 5).

3. Questions With a Delayed Answer (QDA) and How to Naturally Avoid Fragments

In this section, we report and discuss the solutions adopted by Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022) in their study of Catalan information focus to fully or partially overcome the methodological problems discussed in Section 2, both with respect to the question-answer test and the experimental design. It is important to emphasize that the same solutions have also been adopted in the original studies of the syntactic distribution of information focus in Spanish and in Italian that will be presented for the first time in Section 4.

The major problem with the question-answer test when studying the syntax of focus is that the most natural and spontaneous answers to wh-questions are fragments (cf. (5b) above). Complete sentences, which include at least the predicate, are, however, needed to determine the position of the focus within the sentence. To deal with this difficulty, the previous studies have tried to manipulate the answers, either by forcing the production of complete sentences with explicit instructions or by imposing pre-determined full sentences in rating tasks. Following Cruschina & Mayol (Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022), we address this problem in a different way: instead of imposing conditions in the form of instructions that would lead to non-fragment answers but that would, in fact, limit the freedom in the responses, we try to make non-fragment answers the most natural and spontaneous options by manipulating the context of the question. This objective can be achieved with the QDA elicitation technique.

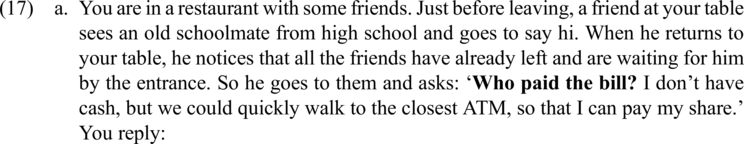

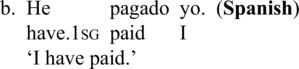

QDA is based on the same task used in the previous production studies on the elicitation of information focus, the discourse completion task, which, in turn, involves the question-answer test: a question is inserted at the end of a contextualized scenario, and the participants are asked to answer that question (see Vanrell et al. Reference Vanrell, Feldhausen, Astruc, Feldhausen, Fliessbach and del Mar Vanrell2018 for an overview). QDA is designed as an improved version of the discourse completion task, aiming to enhance the naturalness and reliability of the question-answer test. This technique consists of the insertion of some lexical material after the question that is asked in the first turn of dialogue in a role-playing situation, as shown in Examples (13) and (14). Within this contextualized scenario, the participant is then asked to answer the question:

This simple strategy overturns the preference for fragments over full sentences, favouring the spontaneous production of non-fragment answers.Footnote 7 Participants are not given answers to the questions and are free to produce the answer that they consider to be most fitting and appropriate in the given fictional context. Although this method is not fully equivalent to spontaneous, naturalistic speech, it has the advantage of showing how speakers realize focus when they are free to create a fictional answer that fits the context.

Given the distance between the answer and the question, created by the intervening lexical material, the ellipsis of the given information in the answer (cf. Section 2.2) proves less natural. The naturalness of the non-fragment answer is supported by the fact that the question under discussion is not maximally salient at the time in which the answer is uttered, and it is exactly in these contexts that non-fragment answers prove most natural, and the background material is expressed overtly (see Vallduví Reference Vallduví, Aloni and Dekker2016, Mayol & Vallduví Reference Mayol, Vallduví, Franke, Kompa, Liu, Mueller and Schwab2020).

From a methodological viewpoint, on the whole, the QDA technique offers significant advantages in the elicitation of informational focus, making the most of the question-answer test and without restricting the naturalness and spontaneity of the answers.

4. The Production Experiments

We used the QDA technique first in a production experiment and then in an acceptability-judgement experiment in all three languages: Catalan, Spanish and Italian. As will be discussed in the next sections, the design of the experiments and the choices adopted in the construction of the stimuli further contributed to tackling the methodological issues reviewed in Sections 2.1 and 2.2. Recall that we first carried out the experiments on Catalan (cf. Cruschina & Mayol Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022), but since the Spanish and Italian experiments were exactly the same, we here present them together. Following the introspection studies (cf. Section 2), for all our experiments, we hypothesized that focus would be expressed in postverbal position, regardless of the languages tested and of its grammatical function. Let us now start with the description and discussion of the production experiments.

4.1. Materials, procedure, participants and hypothesis

This experiment was carried out in three null-subject Romance languages, Catalan, Spanish and Italian, using the same material in the target language: 16 critical items and 16 filler items. As explained (cf. Section 3), all the critical items contained a QDA in order to make non-fragment answers more natural. The fillers included other types of questions, such as polar or alternative questions.

In the design of the stimuli, we took specific measures to prevent the methodological problems discussed in the previous sections (cf. Section 2). Firstly, the scenarios were designed so as to guarantee a neutral interpretation of the focus (i.e. to elicit information focus). Efforts were made to construct the scenarios free of any contextual cues that could trigger a contextual accommodation of special meanings (e.g. mirative) in association with the focus constituent in the answer. Moreover, neither images nor videos were used in order to boost a canonical interpretation of the question and to avoid an obviousness answer. Our ultimate goal was to avoid that the focus in the answer could receive an interpretation other than information focus (cf. 5c). Secondly, few conditions were included in the experimental design. The factor ‘grammatical category’ was only manipulated according to two levels: subject versus object. To this end, only transitive verbs were included in our experimental stimuli. Accordingly, the 16 critical items featuring a QDA consisted of eight subject questions and eight object questions.

A total of 72 speakers participated in the production experiment: 20 native speakers of Catalan, 20 of Spanish and 32 of Italian. All participants received 15 euros in compensation for their time. All our Catalan participants (15 females, 5 males, mean age = 22) were also bilinguals with Spanish (as it is the case for almost all Catalan speakers); they declared that they spoke Catalan at home when growing up and considered Catalan to be their mother tongue. The Spanish participants (15 females, 5 males, mean age = 22.5) were originally from monolingual areas of Spain. Out of the 32 Italian participants (20 females, 12 males,Footnote 8 mean age = 39.7), 20 were from continental Italy, six from Sardinia and six from Sicily. We decided to have a larger sample of Italian participants, including speakers from Sardinia and Sicily, because it has been reported in the literature that these two varieties allow for FF with information focus, exactly in the question-answer context and in the absence of additional interpretative effects (see Jones Reference Jones1993, Reference Jones2013, Cruschina Reference Cruschina2012, Reference Cruschina, Giurgea and Remberger2015, Reference Cruschina2021). To control for a possible transfer from these two languages to the regional varieties of Italian spoken in the two islands, we kept the speakers who were originally from (and still living in) Sicily and Sardinia separate from the rest of the Italian speakers, who were from different other regions of the Italian Peninsula.

As for the procedure, each participant met online with an experimenter (there was an experimenter for each language who was also a native speaker of the variety under investigation) for an individual elicitation session. First, the experimenter asked participants some questions about their sociolinguistic background. Next, the task was explained. Participants were placed in a role-playing situation; they were told to imagine they were talking to someone they knew and that this person would ask them a question. Their task would be to answer the question as naturally as possible. After a short familiarization session, the experiment proper began. The context, including the question, was presented in written form and was also read aloud by the experimenter. The context always ended with a prompt for the participant to reply. Participants replied orally. The 32 items were presented in a pseudo-randomized order, alternating fillers and critical items. At the end, the experimenter briefed the participant about the goal of the study. Each session lasted approximately 20 minutes, and the video calls were recorded for subsequent analysis. All the materials for both experiments, as well as the results and the analysis code, are available at https://osf.io/xdh7r/.

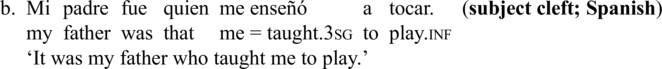

4.2. The results

We elicited a total of 1,152 answers (16 experimental items * 72 participants), which were transcribed and annotated. We excluded from the analysis fragment and non-congruent answers (cf. Section 2.1). As for fragment answers, only a small percentage (5.5%) qualified as such (Catalan: 24 fragments, 7.5%; Spanish: 13, 4.0%; Italian: 27, 5.27%), meaning that the experimental setup was largely successful in eliciting full sentences (i.e. sentences with at least a finite verb and the focus constituent). Since the participants spontaneously responded with full sentences instead of fragments without being explicitly instructed to do so, it was then easy to control for the congruence of the answer with respect to the question. We have thus only selected congruent answers for the analysis of the results, excluding both answers that did not directly address the issue opened by the question and those in which the background was not matching that of the question – e.g. when a different predicate was used (cf. Section 2.1; see also Leal et al. Reference Leal, Destruel and Hoot2018, Hoot & Leal Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020, Hoot et al. Reference Hoot, Leal and Destruel2020). As for non-congruent answers, we excluded 167 answers (Catalan: 80; Spanish: 45; Italian: 41) that did not directly address the question or whose background was not the same as the one in the question, such as the Spanish examples in Example (15), where we give between brackets the question that appeared in the context. In Example (15a), the speaker chooses to refuse to answer the question. In Example (15b), the speaker does not directly answer the question under discussion since she denies the presupposition that someone taught her to play the guitar. In Example (15c), although the speaker does address the question under discussion, the answer does not meet the congruency requirement since the background does not fully match the content in the question (see Cruschina & Mayol Reference Cruschina and Mayol2022 for further examples of non-congruent answers in Catalan).

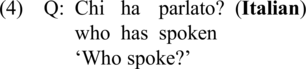

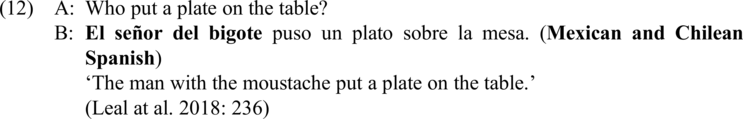

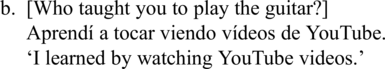

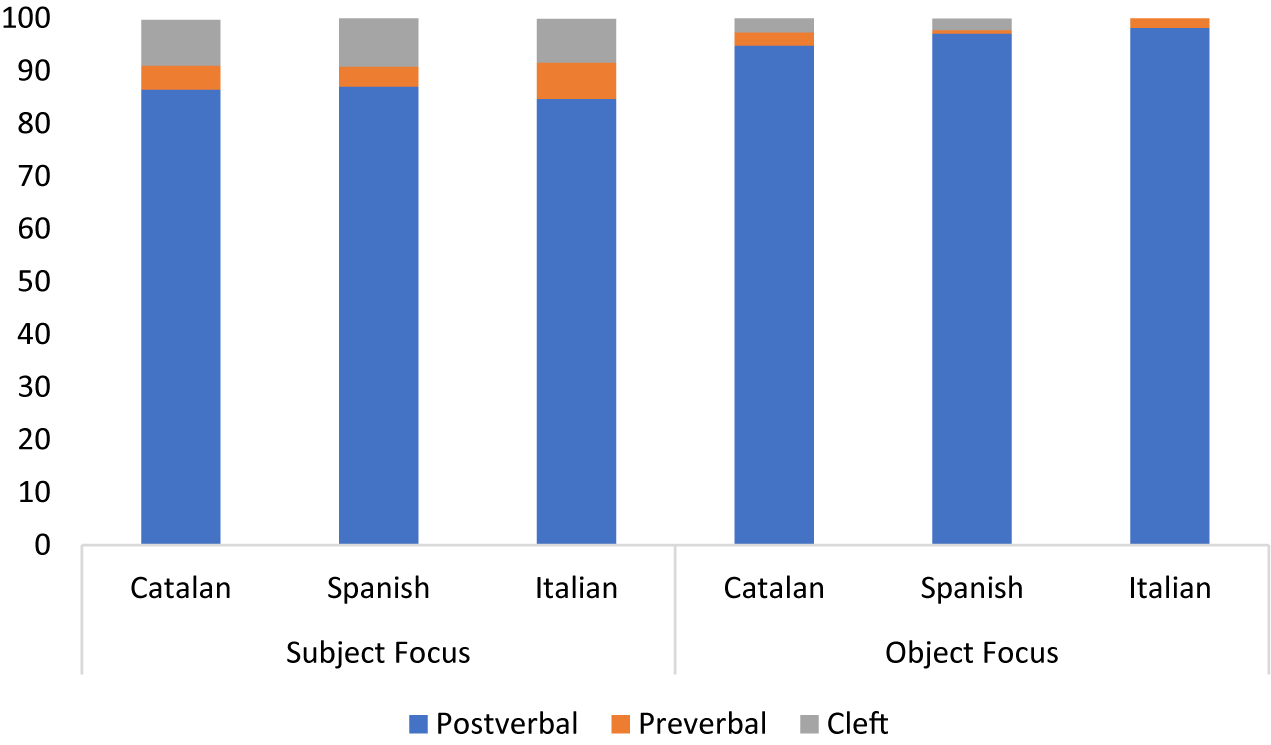

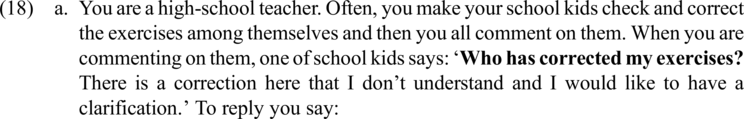

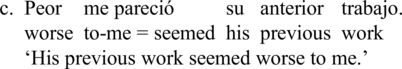

The remaining data set consisted of 935 full sentences (Catalan = 220; Spanish = 271; Italian = 444) that were congruent answers to the question in the context. They were coded according to whether the focus appeared in preverbal position, in postverbal position or whether a cleft had been used. The results, which can be seen in Table 1 and Figure 1, are very similar in all languages

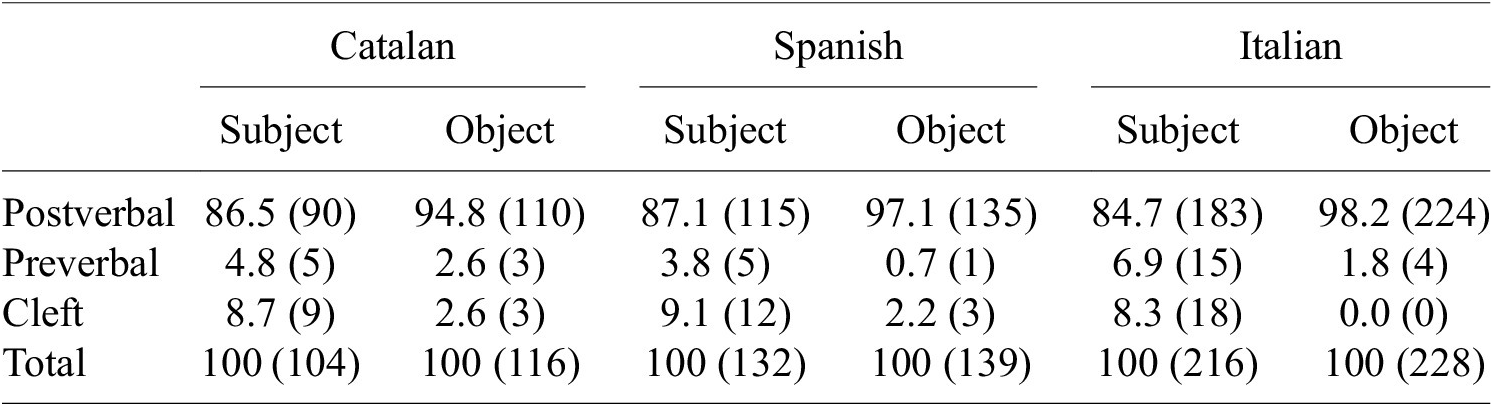

Table 1. Percentage (and counts) of elicited foci by language and construction

Figure 1. Results of the production experiments: % of elicited foci

.

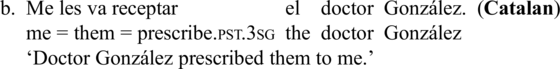

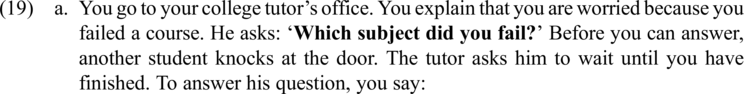

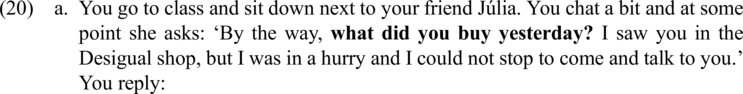

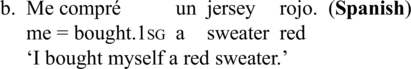

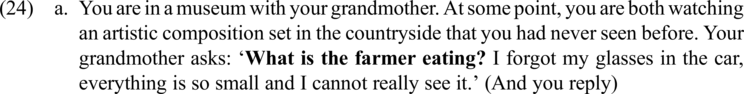

Participants overwhelmingly produced postverbal foci both with subjects (85.8% overall), as shown in Examples (16)–(18), and with objects (95.6% overall), as in Examples (19)–(21), along with a reduced number of preverbal foci, as in Examples (22)–(24), and of clefts, which will be discussed in Section 4.4.Footnote 9 , Footnote 10 Answers with a preverbal focus, be it the subject (cf. Examples (22) and (23)) or the object (cf. Example 24), were produced with main stress on the preverbal constituent.

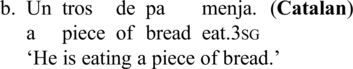

To obtain estimates for our predictors, we performed a mixed-effect logistic regression, using R (R Core Team 2013) and lme4 (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015), in which the dependent variable is the position of the focus: postverbal versus preverbal. We excluded clefts from the statistical analysis to concentrate on the preverbal/postverbal contrast, but clefts are briefly discussed in the next subsection. We entered grammatical function (subjects vs object), language (Catalan, Spanish and Italian) and their interaction as fixed effects, with Object as the reference level for grammatical function and Catalan as the reference level for language. The contrast scheme used for the predictors was treatment coding.Footnote 11 As random effects, we entered intercepts for subjects and items.Footnote 12 The results of this model can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of the results of a mixed model logistic regression for the production data. Rating by position (Preverbal, Postverbal) and grammatical function (Subject, Object)

As can be seen, the realization of preverbal subjects is not significantly higher than preverbal objects. The effect of language, as well as the interaction between order and language, was also not significant. While this failure to reject the null hypothesis should not be taken to confirm the absence of an effect, the absence of significant effects is consistent with our hypothesis. Almost all speakers, irrespective of their geographical precedence, overwhelmingly produced postverbal foci, not only with objects but also with subjects.

Remember that in the Italian experiment, we had 20 continental speakers, six speakers from Sicily and six speakers from Sardinia. Excluding the speakers from Sicily and Sardinian does not greatly alter the pattern obtained for the whole sample: the rate of postverbal subject foci was 92.4 overall and 92.9 for continental speakers; the rate of postverbal object foci was 98.2 overall and 100.0 for continental speakers. It is, however, interesting to note that 40% of all SV utterances and 100% of all OV sentences were produced by one speaker from Sicily (cf. Table 2, under Italian), who used preverbal foci in 67% of her overall production. This is indeed a relevant finding with respect to the hypothesis of a possible transfer from Sicilian (cf. Section 4.1), also because, in the preliminary sociolinguistic questionnaire, this speaker stated that Sicilian was the main language spoken at home during her childhood. At any rate, these data are not enough to support the transfer hypothesis beyond this individual case, given that all other five Sicilian speakers did not resort to preverbal foci so frequently. Further research, with more attention to sociolinguistic variables, is indeed necessary before any tenable claim on this issue can be made.

In conclusion, the results of our production experiment differ considerably from those in previous experimental studies. As proposed by introspective studies, we found a strong tendency to place the information focus postverbally for the three languages and the two grammatical categories under study.

4.3. Non-focal constituents

In this section, we discuss in more detail the sentences produced in the experiment. As mentioned, the QDA technique was largely successful in eliciting full sentences. However, it is important to point out that not all constituents were repeated in the answers. In their free production, the participants rarely repeated the given constituents in the question: independently of the preverbal or postverbal realization of the focus, the direct objects of subject questions were cliticized, frequently without the dislocation of the given argument, as shown in Example (25), while the subjects of object questions were generally omitted, as in Example (26):Footnote 13

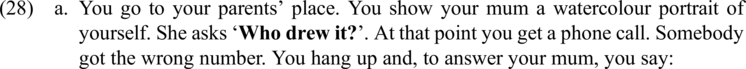

In several cases, when the subject or the object was already salient in the description of the scenario, it was already omitted or cliticized in the question. See the pronominalization (with a null pronoun in the original stimuli) of the subject in the object question in Example (27) and the cliticization of the direct object in the subject question in Example (28):

This kind of data confirmed that the repetition of the given material appearing in the question is infrequent in natural production, and at the same time, it contributed to the simplicity of the analysis, which did not have to be concerned with the intervention of given material in the answers as a possible confounding variable. This potential problem was also avoided in the acceptability-judgement experiment, given that the answers that were the target of the rating task were directly taken from the data elicited in the production tasks (cf. Section 5).

4.4. A note on clefts

Despite the fact that they qualify as congruent answers, we did not include clefts in our analysis. This choice was motivated by several considerations. First of all, we classified as ‘cleft’ different types of cleft constructions, including pseudo-clefts, for which it was not always obvious how to distinguish between the preverbal and postverbal position of the focus. Secondly, it has been shown that clefts as an answering strategy are sensitive to the syntactic category for the focus, being more frequent and common in answer to subject questions than with object questions (Belletti Reference Belletti, Brugè, Giusti, Munaro, Schweikert and Turano2005). Thirdly, there are significant differences in the syntactic shape and in the frequency of cleft constructions across Romance languages (De Cesare Reference De Cesare, Dufter and Stark2017). For all these reasons, we decided to keep clefts as a separate category in our analysis, a decision that was further motivated by the reduced number of clefted foci in our results (cf. Table 1).

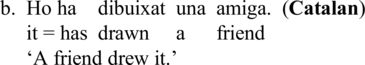

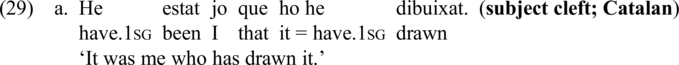

In this section, however, we briefly discuss the main differences across the three languages under consideration so as to provide an explanation for the different incidence in the production task. In Catalan and Spanish, only very few full subject clefts were produced, with either a postverbal or a preverbal focus, as shown in Example (29a) and (29b), respectively:

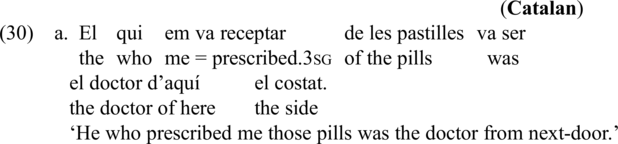

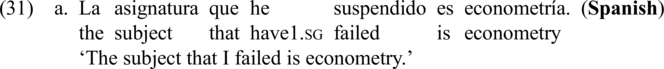

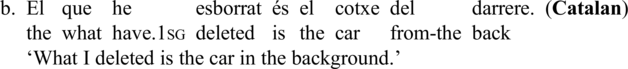

Most of the other clefts produced were, in fact, reduced clefts, with an elided pseudo-relative clause and limited to subject clefts (e.g. Catalan: He estat jo ‘It was me’, Spanish: Fue Paula ‘It was Paula’) or pseudo-clefts of the kind illustrated in Example (30) for subject clefts and in Example (31) for object clefts:

As for Italian, no pseudo-clefts were produced, and a radical asymmetry was found between subject (8.3%) and object (0.0%) clefts as answers to wh-questions. Most of the subject clefts (12 out of 18) were reduced clefts (e.g. È stato mio nonno/il mio vicino ‘It was my grandpa/my neighbour’). The remaining five clefts were full subject clefts. Given that neither full nor reduced clefts are readily available as an answering strategy for questions on the identification of the object (see Belletti Reference Belletti, Brugè, Giusti, Munaro, Schweikert and Turano2005), the observed asymmetry and the absence of object clefts are not unexpected. Note that the marginal number of object clefts produced in Catalan and Spanish were, in fact, pseudo-clefts (cf. Example 31).

5. The Acceptability-Judgement Experiments

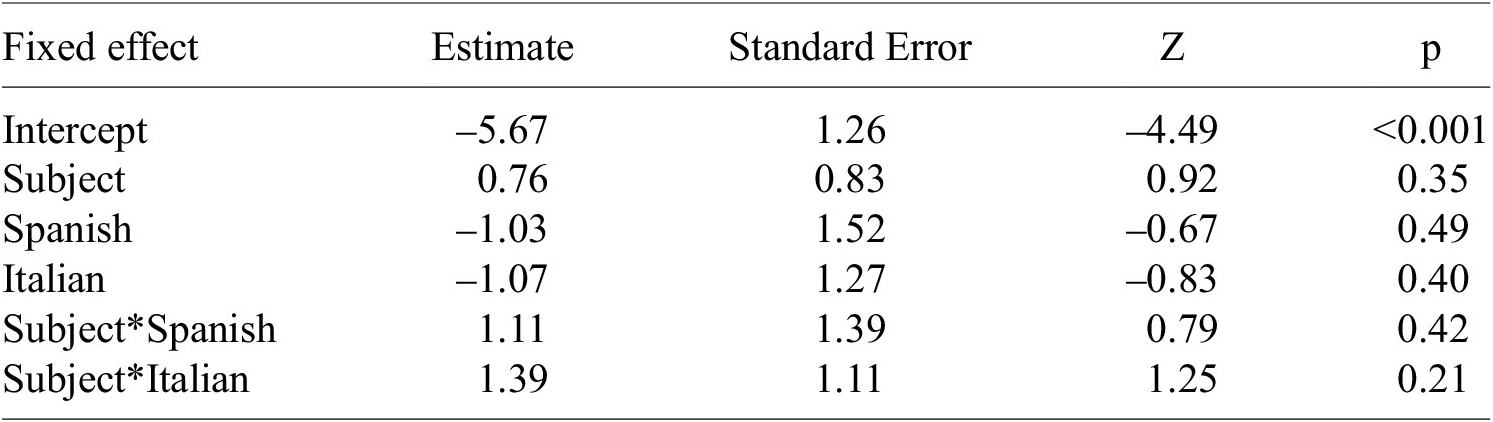

The production experiment showed a sizable preference for the postverbal placement of information focus. It was also observed that a reduced number of preverbal foci were produced in a somewhat larger proportion for subjects than objects. This difference was not statistically significant, but since much of the previous literature, especially with judgement tasks, has found preverbal subject focus to be acceptable (cf. Section 2), we decided to investigate the position of information focus further by means of an acceptability-judgement experiment. By asking participants to rate different options instead of producing only one form, we can gain more insight about the status of the dispreferred form in the production study (that is, the preverbal focus).

Our acceptability-judgement experiments had a simple 2*2 factorial design, with only two factors with two levels each (1. syntactic category: subject vs object, 2. focus position: preverbal vs postverbal). These conditions were systematically crossed, allowing the examination of the interactions between factors (cf. Section 5.1). We used written stimuli in order to avoid the possible interference of factors related to prosody and prosodic variation, as well as the presentation of audio stimuli with marginal or unnatural prosodic contours. Our hypothesis is that postverbal foci will be rated higher than preverbal foci in the three languages and for both grammatical functions.

5.1. Materials, procedure, participants and hypothesis

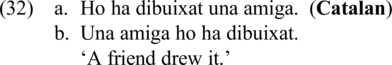

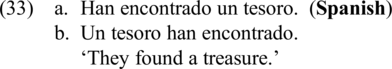

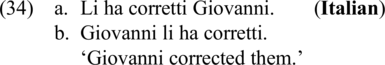

We carried out an acceptability-judgement study in which participants were asked to rate how natural a sentence was as an answer to a question with a 7-point Likert scale whose extremes were labelled as ‘impossible’ and ‘perfect’. We used the same stimuli as in the production experiment: a description of a context with a QDA, with the addition of an answer taken from the elicited data in the production experiment. Each answer was shown in two versions: with a preverbal focus and with a postverbal one, as shown in Examples (32)–(34) for Catalan, Spanish and Italian, which are answers to the questions in Examples (13), (14) and (18a), respectively. Recall that in the production experiment, participants mostly produced postverbal foci. This means that for this acceptability-judgement task, we have added a version of the answer with the alternative order (i.e. with a preverbal focus) that, in fact, was never – or almost never – produced in the first experiment. In line with the data from the production experiment (cf. Section 4.3), moreover, we consistently omitted or cliticized the non-focal argument of the sentence:Footnote 14

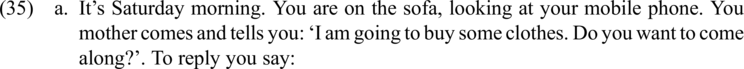

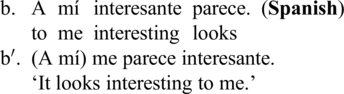

The experiment included 16 critical items: the QDA contexts from the production experiment (eight containing subject questions and eight with object questions) together with one answer with either a preverbal or a postverbal focus. Two lists were built so that each participant would only see one version of the answer. Each list also contained 16 fillers, which were also the same used in the production experiment. Since the fillers consisted of polar or alternative questions, they were only shown in one version, with no word order variation. Most of the fillers contained acceptable and felicitous answers, exactly as produced in the first experiment, but we also included a few fillers with answers that were either nonsensical, as in Example (35), or ungrammatical, as in Example (36) (the grammatical answer is shown in Example (36b’)). This was done for two reasons: on the one hand, to encourage participants to use the full scale and, on the other, to have a baseline to compare our items to fully unacceptable ones.

A total of 390 native speakers of Catalan, 197 native speakers of Peninsular Spanish and 200 native speakers of Italian took part in the experiment. Participants were recruited through Prolific (an online platform to recruit research participants for studies, surveys or experiments) or social networks, and the data were collected through Google Forms. First, participants read the instructions in which the procedure was explained. Then, each item was presented individually in a random order, and participants were asked to rate the degree of acceptability of each answer in the context in which it appeared. The task lasted 15 minutes approximately.

Before looking at the results, we would like to close this section with a brief discussion of the type of stimuli that can be used in a quantitative study (written vs auditory stimuli) and with a further justification of our choice to use written stimuli in the rating experiments. The majority of the previous studies that used acceptability judgements adopted written stimuli – with exception of Hoot (Reference Hoot2012, Reference Hoot2016), which had auditory stimuli. As observed by Escandell Vidal & Leonetti (Reference Escandell Vidal, Leonetti, Ruiz, Moreno and Lamas2019), prosodic cues are missing with written stimuli, making it difficult for the experiment to determine whether a sentence with an SVO order was interpreted as involving a marked initial focus subject (SVO) or rather a sentence with an unmarked SVO/(S)OV order (cf. Examples 32b, 33a, 34b), thus providing an explanation for the higher scores attributed to SVO as opposed with OVS, which only allows a focal reading of the object. This is indeed a shortcoming of written stimuli, but at the same time, it must be noted that the use of auditory stimuli would run into a number of risks. The prosodic features of the focal structure may distract the experimental participants or even shift their attention to the position of the pitch accents and to the acoustic realization of the prosodic contour. Different factors can influence these properties, including the type of focus and dialectal variation (see Prieto et al. Reference Prieto, Borràs-Comes, Cabré, Crespo-Sendra, Mascaró, Roseano, Sichel-Bazin, del Mar Vanrell, Frota and Prieto2015 and references therein; see also Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Bocci, Cruschina, Aboh, Schaeffer and Sleeman2015, Reference Bianchi, Bocci and Cruschina2016 on the prosodic differences between corrective and mirative focus in Italian). Note also that the use of auditory stimuli would involve the production of word order options – to be recorded before the experiment and presented to the participants as experimental stimuli – that are already known to be marginal or totally unacceptable, thus running the risk of sounding artificial and unnatural. For all these reasons, we decided to use written stimuli in our rating experiments.

5.2. The results

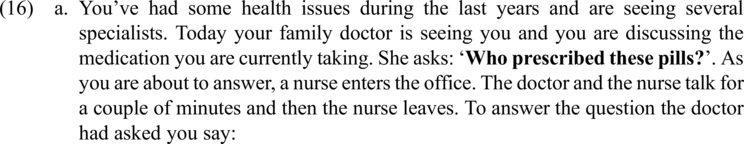

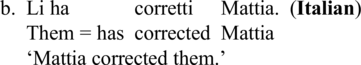

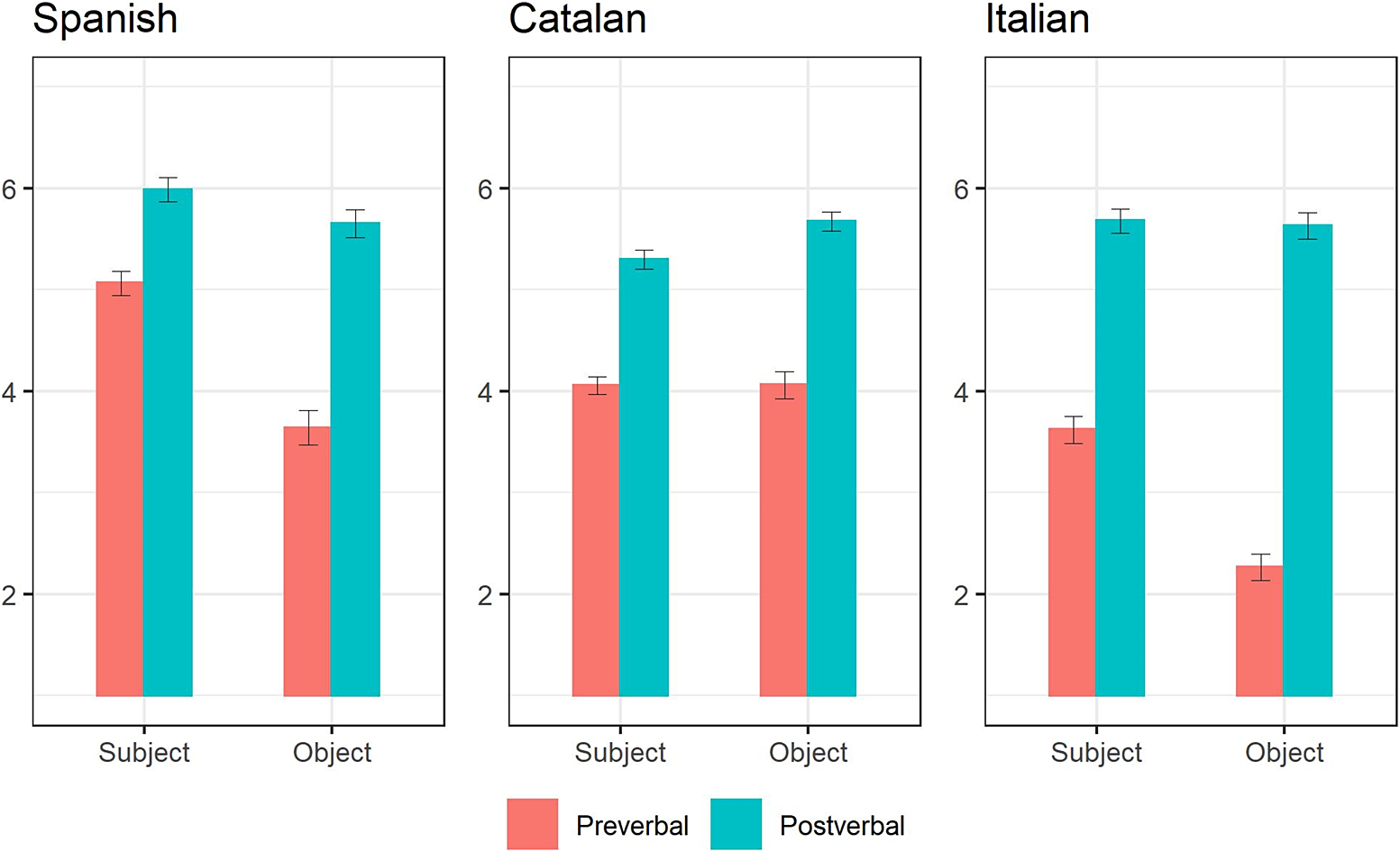

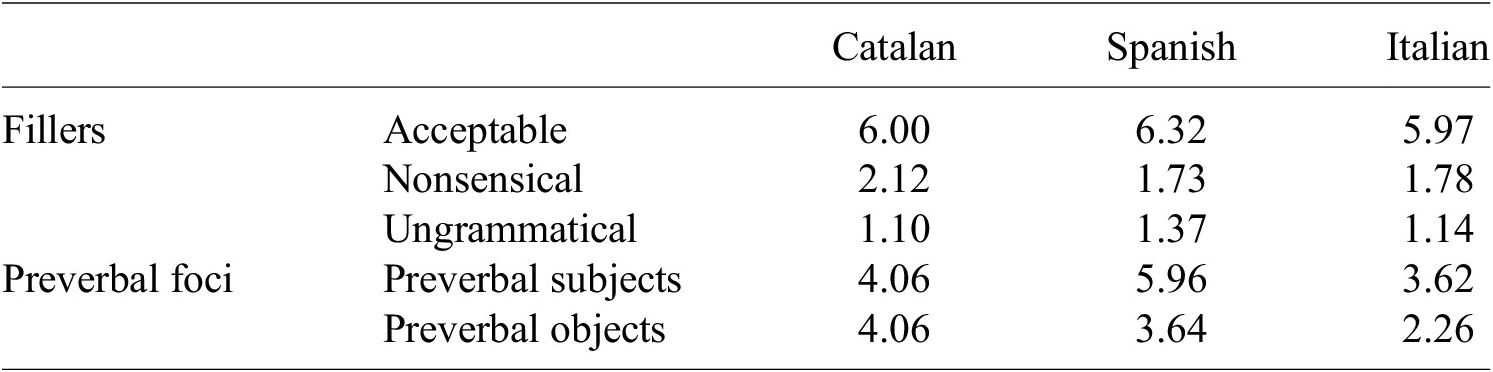

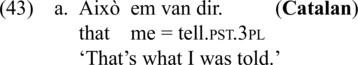

The results of the acceptability-judgement experiment, shown in Figure 2, largely confirm the findings of the production experiment: in all languages, postverbal focus is always preferred over the two types of preverbal focus, both in the case of subjects and objects. Postverbal foci receive similar ratings in the three languages and with respect to the two grammatical functions. In contrast, the ratings for the preverbal foci vary across language. In Catalan, there is no difference between the ratings of preverbal subjects and objects (both are 4.06), while both in Italian and Spanish, preverbal subjects are rated higher than objects (5.96 vs 3.64 for Spanish and 3.62 vs 2.26 for Italian). In addition, the mean ratings for both types of preverbal foci are higher in Spanish than in Italian, while the rating for Catalan is intermediate between the two other languages.Footnote 15

Figure 2. Results of the acceptability-judgement experiments: Average ratings of raw scores as a function of focus position and grammatical category across languages.

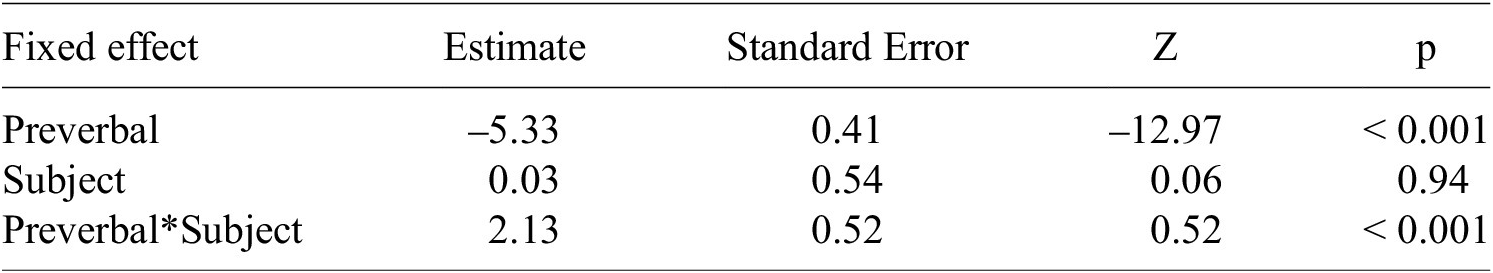

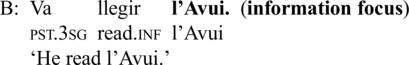

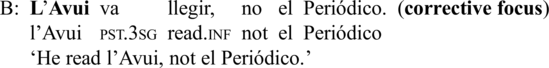

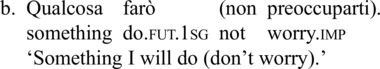

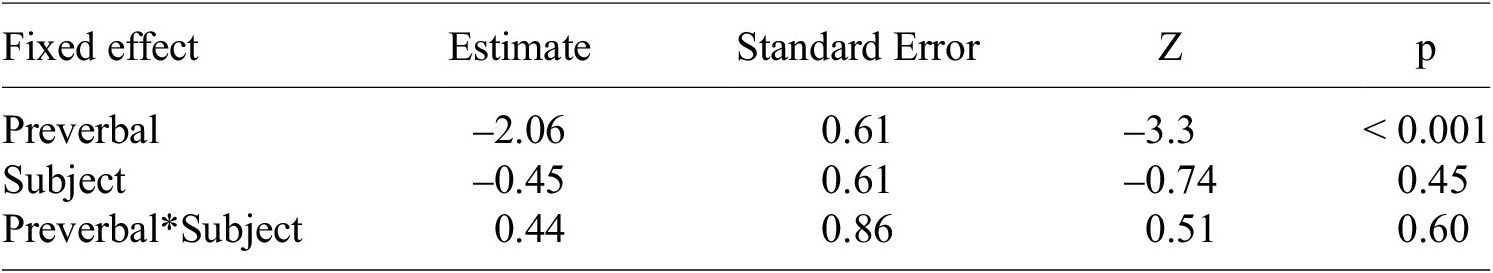

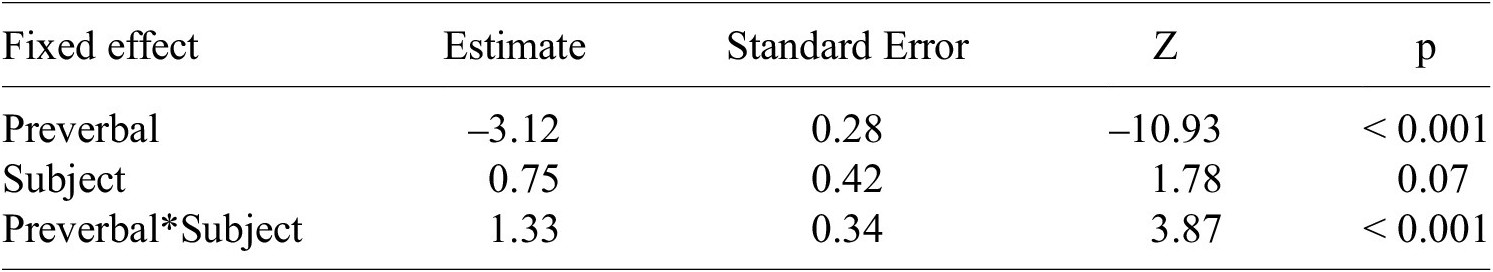

To test for the statistical significance of the data, we performed a mixed model ordinal regression for each of the three languages on the ratings, with grammatical function, position of the focus and their interaction as fixed effects, and participants and items as random effects.Footnote 16 In Catalan, the preverbal position significantly leads to lower ratings (β = –2.06, p < 0.001), but neither grammatical function (β = –0.45, p = 0.45) nor the interaction between the two effects is significant (β = 0.44, p = 0.60). In contrast, in Spanish, position of the focus and the interaction between position and grammatical function are significant (and the effect of grammatical function on its own is not). As in Catalan, the ratings of preverbal foci are significantly lower (β = –3.12, p < 0.001) than the ratings of postverbal foci. Unlike Catalan, however, in Spanish, the items with foci that were both subjects and preverbal received significantly higher ratings (β = 1.33, p < 0.001). Finally, in Italian, we find the same situation as in Spanish: the ratings of preverbal foci are significantly lower (β = –5.33, p < 0.001) than the scores assigned to postverbal foci, and the ratings of foci that are both subjects and preverbal are significantly higher (β = 2.13, p = 0.001) than those given to preverbal objects. Note that the effect of position for object is larger in Italian than in Spanish (–5.33 vs –3.12), which translates into lower ratings for preverbal foci in Italian than in Spanish. More details about the models for Catalan, Spanish and Italian can be found in the Appendix (cf. Tables A1, A2 and A3).

A striking result of this second task is that preverbal foci are not rated as unacceptable by our participants. Going back to the raw results, it is informative to compare the ratings of preverbal foci to the ratings of the fillers, as shown in Table 3 (see Examples (35) and (36) above for examples of nonsensical and ungrammatical fillers).

Table 3. Mean ratings of fillers by language and acceptability compared with the mean ratings for preverbal foci

It can be seen that both ungrammatical and nonsensical fillers obtain very low ratings. In contrast, sentences with preverbal foci received higher ratings, towards the middle of the scale, with the exception of preverbal objects in Italian. Thus, rather than being treated as unacceptable, sentences with preverbal foci are judged as marginally acceptable to some extent, particularly in the case for subjects. Interestingly, the three languages seem to form a continuum with respect to the degree of acceptability of those sentences: Spanish displays the highest degree (mean of 4.35), followed by Catalan (4.06) and Italian (2.94). In addition, two of the combinations of language and grammatical function clearly escape the area of what we have called marginal acceptability at both extremes of the scale: in Spanish, preverbal subjects are rated almost as high as postverbal subjects (5.06 vs 5.99), while, in Italian, preverbal objects are rated almost as low as the unacceptable fillers (2.26). Catalan, on the other hand, seems to be pretty happy with focus fronting of objects in information focus (4.06), more so than Spanish (3.64) or certainly Italian (2.26). Although postverbal focus is clearly preferred in Catalan, too, it is noteworthy that in this language, fronting the object is rated just as high as preverbal subjects (4.06).

To sum up, the acceptability-judgement experiment corroborated the main result from the production experiment: postverbal foci are preferred to preverbal foci in any of the combinations we tested. In addition, giving speakers the chance to rate all the different options also helped to paint a more complex picture of the distribution of preverbal foci. A focal interpretation of the preverbal constituent is available to some extent, particularly for subjects in Spanish, less so in Catalan, where both preverbal subjects and objects obtained marginal ratings, and even less so in Italian, where preverbal objects are unacceptable. The next section explores a way of making sense of this difference regarding how different languages map information structure to syntax.

6. Restrictive and Permissive Languages

Romance languages display an SVO order in canonical sentences and use variants of this word order to convey different informational values, as we saw for the different values of focus fronting (cf. Section 1). There is, however, significant variation in how available and productive these non-canonical orders are, which points to different ways of mapping information structure to syntax. In particular, Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) distinguishes two groups of languages within the Romance family: what he calls ‘restrictive’ and ‘permissive’ languages. Restrictive languages include Catalan, Italian and French, while permissive languages include Spanish, European Portuguese and Romanian.

Restrictive languages have a straightforward mapping between syntax and information structure: marked orders are only allowed for specific informational partitions, and specific informational partitions tend to be expressed through marked orders. This results in the avoidance of complex sentences without informational partitions; instead, clefts, dislocations or frontings are used to separate the focal and non-focal segments of an utterance. Another consequence is that wide-focus readings are restricted and incompatible with most non-canonical orders. In contrast, in permissive languages, the mapping between syntax and information structure is less transparent. The same order is compatible with different interpretations, such as narrow- or wide-focus readings, and it is possible that a marked order does not encode a clear informational partition.

Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) describes three phenomena in which the differences between the two groups of languages most clearly surface: the acceptability of constructions with subject inversion, the grammaticality of VSO and the productivity of non-focus fronting constructions (see also Leonetti Reference Leonetti, Lahousse and Marzo2014).

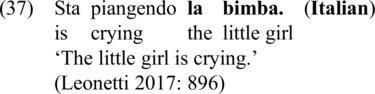

As for subject inversion, although it is possible in both groups of languages, its acceptability is subject to less constraints in permissive languages. For instance, in Spanish, inversions with unergative verbs can more easily receive a wide-focus interpretation. In Catalan and Italian, subject inversion with some unergative verbs, as in Example (37), would most likely be interpreted with narrow focus on the subject:

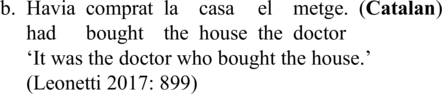

A similar situation is also found with VOS sentences. In Catalan and Italian, this order encodes a clear topic-focus partition in which the postverbal subject is interpreted as narrow focus.

In addition, both languages often prefer a structure with less postverbal material in which the object is cliticized or dislocated.

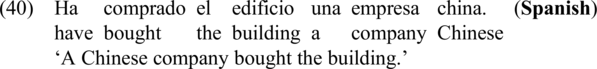

In Spanish, this strategy is much less frequent, and VOS sentences, such as Example (40), are compatible not only with narrow focus on the subject (Zubizarreta Reference Zubizarreta1998, Reference Zubizarreta, Bosque and Demonte1999: 125, 4233) but also with a wide focus reading (Leonetti Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017: 900–901).Footnote 17

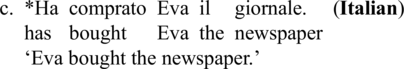

An even more striking difference concerns the grammaticality of VSO orders. While they are available in Spanish, they are not in Catalan and Italian as shown in Example (41).Footnote 18

Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) takes this contrast to be a consequence of the different behaviours of permissive and restrictive languages. In Spanish, a VSO sentence usually receives a wide-focus interpretation, so this would be an example of a marked order surfacing in a context without informational partitions. This state of affairs is not permitted in restrictive languages; an informational partition is required for a marked VSO order, but none is possible with two postverbal constituents.

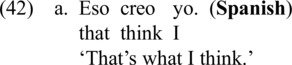

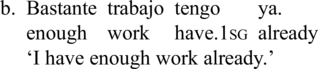

Finally, non-focal fronting also sets apart the two groups of languages. In this construction, a non-focal element is fronted (and unlike dislocations, it does not display a resumptive clitic). The fronted constituent usually contains an anaphoric element, a comparative or a quantifier, as shown in Example (42) for Spanish. This construction is also available in Catalan and Italian, as shown in Examples (43) and (44), but it is certainly less productive than in Spanish. According to Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017: Sections 3.2.1–3.2.2), for example, the counterparts of Example (42c) in Catalan and Italian are unacceptable:

Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) does not discuss the realization of information focus in permissive and restrictive languages. However, our experimental data fit nicely into the described pattern. While all three languages show a strong tendency to resort to a dedicated word order with a more transparent information-structure partition for focal subjects (i.e. VS), Spanish is more permissive than Catalan and Italian in also allowing a narrow-focus interpretation of the subject in an SV order.Footnote 19 In fact, instead of a dichotomy between restrictive and permissive languages, our data point towards a continuum from more permissive to less permissive languages, where Catalan is less permissive than Spanish but more permissive than Italian in allowing a focal interpretation of preverbal subjects (cf. Figure 2, Section 5).

This continuum is clear if we simply look at the general mean scores of preverbal foci from our acceptability-judgement experiments (Spanish: 4.35, Catalan: 4.06, Italian: 2.94), but it is even more evident when the effects of the grammatical function are taken into account. These results show that the ratings of the preverbal foci vary across languages depending on whether the focus is a subject or an object (Spanish: 5.96 for preverbal subjects vs 3.64 for preverbal objects, Catalan: 4.06 for both preverbal subjects and preverbal objects, Italian: 3.62 for preverbal subjects vs 2.26 for preverbal objects). The grammatical category is irrelevant in Catalan, where there is no difference between the ratings of preverbal subjects and objects, but it has significant effects in Spanish and Italian, where preverbal subjects are rated higher than objects. This difference with respect to the sensitivity to the grammatical category of the focus is not captured by Leonetti’s (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017) distinction between permissive and restrictive Romance languages, and it is certainly an interesting result that we will investigate further in future work.Footnote 20 At the same time, it is worth noticing that it reflects a long-standing and independent observation in the relevant literature about the general syntactic behaviour of Catalan, where information-structure conditions seem to be the most relevant factor in determining the surface word order (see Vallduví Reference Vallduví1992, Reference Vallduví and Kiss1995, who defines Catalan as a ‘discourse configuration language’).

7. Conclusions

This paper has explored the realization of information focus in three Romance languages: Catalan, Spanish and Italian. Using a new methodology that greatly improves the naturalness of full sentences as answers to wh-questions, we show that information foci are preferably realized in a postverbal position in the three languages, in support of previous theoretical proposals, mostly based on introspection. The findings about the production of information focus are corroborated by an acceptability-judgement task: postverbal foci are always rated higher than preverbal foci. At the same time, however, the observation coming from more recent experimental studies that a focal interpretation of the preverbal constituent in answers to questions is possible finds a reflex in the data from our rating experiment. This interpretation is especially available with preverbal subjects in Spanish, showing an important difference between the three languages. Thus, the preverbal position of foci cannot totally be excluded and the extent to which they are acceptable varies from language to language: they are rated higher in Spanish, followed by Catalan and with Italian in the third place. We interpreted this difference in the light of the hypothesis that was independently formulated in Leonetti (Reference Leonetti, Dufter and Stark2017), according to which Catalan and Italian are more restrictive than Spanish with respect to the mapping between syntax and information structure. Instead of a binary distinction, we propose a continuum from more permissive to more restrictive languages, according to which Italian is more restrictive than Catalan.

In addition to empirical matters, this article contributes to methodological issues. Our experimental method allowed us to address and explore central questions that cannot otherwise be answered with traditional and less refined methods of data collection. In this study, we investigated the validity of the traditional and of the experimental methods adopted so far, but we also investigated the possible causes of the differences between production and rating tasks and the sources of the crosslinguistic differences. Although we believe that our experimental approach and empirical proposal are on the right track to explain both large- and small-scale differences in acceptability across the languages that we examined, we are aware that we have only begun to scratch the surface of the potentialities that experimental syntax offers to shed light on these questions. In particular, from a theoretical perspective, it will be necessary to provide a deeper characterization of restrictive and permissive languages that is able to explain the optionality of focus movement. This question is addressed in Bianchi & Bocci (Reference Bianchi, Bocci and Piñón2012), who propose the alternative spellout approach, according to which FF always takes place and what is optional is where the moved constituent is pronounced: either in its base position, yielding in-situ focus or in its landing site, giving rise to FF. Following Bobaljik & Wurmbrand (Reference Bobaljik and Wurmbrand2012), Bianchi’s (Reference Bianchi2019) refines further the alternative spellout approach to explain the optionality of FF in Italian, which in her analysis is regulated by soft constraints that operate at the interface between LF (Logical Form) and PF (Phonological Form).Footnote 21 In future work, we would like to apply and adapt this approach to the data presented in this paper in order to account not only for the optionality of movement but also for the gradience of the judgements that emerged in our rating experiment, thus providing a more principled explanation of the distinction between restrictive and permissive languages.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and detailed suggestions, which helped us to improve this paper during the stages of the reviewing process. We are also grateful to Valentina Bianchi and Giuliano Bocci for their useful comments on a previous draft of this paper and to Jordi de la Vega for his assistance with the experiments. This research was partly supported by project EXPEDIS (PID2021-122779NB-I00), funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ‘ERDF A way of making Europe’. This article is dedicated to the memory of Manuel Leonetti, who has been a true inspiration to us for many years, both for his work on focus and information structure and for his passion and enthusiasm as a linguist.

Appendix

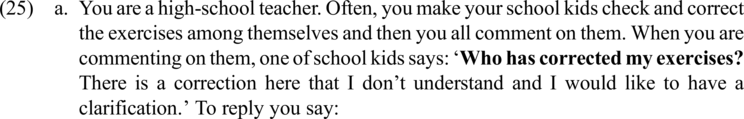

Table A1. Summary of a mixed model ordinal regression for the Catalan acceptability data. Rating by position (Preverbal, Postverbal) and grammatical function (Subject, Object). Model: rating ~ position * grammaticalFunction + (position|items) + (position * grammar|participants)

Table A2. Summary of a mixed model ordinal regression for the Spanish acceptability data. Rating by position (Preverbal, Postverbal) and grammatical function (Subject, Object). Model: rating ~ position * grammaticalFunction + (position|items) + (position * grammar|participants)

Table A3. Summary of a mixed model ordinal regression for the Italian acceptability data. Rating by position (Preverbal, Postverbal) and grammatical function (Subject, Object). Model: rating ~ position * grammaticalFunction + (position|items) + (position * grammar|participants)