On January 6, 2021, supporters of President Donald Trump illegally breached the U.S. Capitol in an attempt to prevent Congress from certifying then President-elect Biden’s election victory. Though extraordinary as an insurrection, these events reflect broader trends in right-wing radicalization in the United States (see Belew Reference Belew2019; Jardina Reference Jardina2019; Mudde Reference Mudde2017; Perliger Reference Perliger2020). The 2020 Homeland Threat Assessment suggested far-right extremists represent an urgent, long-overlooked security concern. While the most lethal incident in American history remains the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, far-right violence continues today in the forms of the “militia” movement (e.g., Oath Keepers and Three Percenters), white supremacist organizations (e.g., KKK, Proud Boys, and Attomwaffen Division), and mass shootings perpetrated by individuals steeped in far-right politics (e.g., Charleston, SC [2015], Pittsburgh, PA [2018], El Paso, TX, Poway, CA [2019], and Buffalo, NY [2022], among others).

An individual’s escalation to violence is rarely immediate, but rather the culmination of a gradual radicalization process whereby beliefs increasingly challenge the bounds of mainstream political debate (Bartlett and Miller Reference Bartlett and Miller2012; McCauley and Moskalenko Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2008, see also Horgan Reference Horgan2004; McCauley and Moskalenko Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2011; Moghaddam Reference Moghaddam2005; Taylor and Horgan Reference Taylor and Horgan2006). Mudde (Reference Mudde2019) distinguishes the “mainstream-right,” operating within prevailing democratic institutions, from the “radical-right,” which accepts the fundamentals of democracy while opposing core elements of liberal democracy, and the “extreme-right,” which rejects democracy and justifies violence. While very few individuals engage in extreme-right violence, many participate in nonviolent radical-right activism (e.g., disseminating radical messages and symbols, organized demonstrations, supporting radical political organizations), often beginning in otherwise apolitical “gateway” social spaces like clubs, festivals, or online platforms (Miller-Idriss Reference Miller-Idriss2020a). Beyond a stepping stone to the extreme-right, radical-right activities have direct consequences of distorting policy debates and undermining trust in democratic institutions.

Why do some communities in the contemporary United States exhibit greater participation in nonviolent radical-right action than others? We argue that communities bearing the costs of foreign wars undergo higher rates of right-wing radicalization. Fatalities among community members serving in foreign wars exacerbate war-related grievances and lead some to political ideologies, including on the far right, that delegitimize prevailing democratic institutions.

We investigate this claim empirically in one prominent “gateway” space—online social media—by examining publicly available user data from Parler, infamous as a platform for right-wing radicalization (Aliapoulios et al. Reference Aliapoulios, Bevensee, Blackburn, Bradlyn, De Cristofaro, Stringhini and Zannettou2021; Isaac and Browning Reference Isaac and Browning2020). We map war fatalities in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2003 to the deceased’s hometown. We aggregate both datasets to the county and census tract levels. We find a strong correlation between Parler video uploads and military fatalities, persistent across levels of analysis and covariate adjustment for a variety potential confounders, including partisanship, economic conditions, demographics, and military service. This analysis does not identify a causal effect of war fatalities on online radicalization. Rather, preliminary evidence consistent with the argument’s empirical implications motivates future research to further explain this relationship. The exploratory findings are important because the Parler data provide a unique opportunity to empirically investigate radical-right action which, though widespread and critical to radicalization processes, is not generally investigated and reported by law enforcement, government agencies, or media in ways conducive to systematic measurement.

EXPLAINING RIGHT-WING RADICALIZATION

We argue U.S. foreign military engagements, by imposing costs on communities, increase right-wing radicalization. Many young adults sent to fight abroad will not return, imposing an emotional toll on family and friends and generating gaps in community social and economic networks. Community members may assess the war’s achievements unfavorably relative to its costs, and oppose policies and politicians that support the war effort. Given the intensity of war-related grievances, some may go further, radicalizing into beliefs that challenge the legitimacy of prevailing democratic institutions.

Why might local war fatalities lead to right-wing radicalization, specifically? Belew (Reference Belew2019) highlights that U.S. military engagements predict surges in membership of far-right organizations as veterans “bring the war home,” and experts note military and law enforcement personnel are disproportionately represented in far-right political organizations and events (see Belew Reference Belew2019; Donnelly Reference Donnelly2021; Jackson Reference Jackson2020; Ware Reference Ware2019), including the Capitol insurrection (see Jones et al. Reference Jones, Doxsee, Hwang and Thompson2021; Miller-Idriss Reference Miller-Idriss2020b; Milton and Mines Reference Milton and Mines2021). Individuals with close connections to military personnel are most affected by war fatalities, and evidence suggests social proximity to the military is associated with radical right politics, for example, voting for far-right parties (Villamil, Turnbull-Dugarte, and Rama Reference Villamil, Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2021). Because political ideology is shaped predominantly by group attachments, individuals are far more likely to radicalize within their pre-existing political camp than within ideologies that contradict long-held beliefs (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017).

Beyond the obvious implication that right-wing radicalization occurs in right-leaning communities, our argument suggests that among those with similar political orientation, communities that suffer higher wartime fatality rates will exhibit higher rates of radical-right action, such as sharing (mis)information or expressing support for radical ideas on social media.

Existing research links right-wing radicalization to economic insecurity and social isolation (Baccini and Weymouth Reference Baccini and Weymouth2021; Bolet Reference Bolet2021; Carreras, Irepoglu Carreras, and Bowler Reference Carreras, Irepoglu Carreras and Bowler2019; Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2018), demographic and cultural shifts in the population,Footnote 1 and elite polarization (Kydd Reference Kydd2021). We highlight an additional factor: the relationship between U.S. foreign military engagements and politics at home. The findings complement existing work linking military engagements and the radical right by emphasizing their influence on society more broadly, beyond (exclusively) those who serve. We show these consequences extend beyond right-wing voting behavior (e.g., Villamil, Turnbull-Dugarte, and Rama Reference Villamil, Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2021) to include radicalization.

Research exploring the impact of war casualties on political behavior and public opinion suggests they generate an initial “rally-around-the-flag” effect (Brody Reference Brody1991; Mueller Reference Mueller1973), but later turn the population against the war effort (Gartner and Segura Reference Gartner and Segura1998; Gartner, Segura, and Wilkening Reference Gartner, Segura and Wilkening1997; Kriner and Shen Reference Kriner and Shen2012), incumbent government and politicians (Gassebner, Jong-A-Pin, and Mierau Reference Gassebner, Jong-A-Pin and Mierau2008; Karol and Miguel Reference Karol and Miguel2007; Kibris Reference Kibris2011; Kriner and Shen Reference Kriner and Shen2007; Umit Reference Umit2021), and political engagement in general (Kriner and Shen Reference Kriner and Shen2009). Our findings suggest casualty-sensitivity may have further consequences for political radicalization.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To investigate our claims empirically, we explore the spatial correlation between right-wing radicalization, measured by the number of videos uploaded on Parler between January 1, 2020 and January 10, 2021, and the number of fatalities in the U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In our conceptual and theoretical framework, communities are networks of social relationships. Yet, data on key predictors are collected for administrative units defined in geographic rather than social space. To address this issue, we explore the data at two different levels of aggregation: county and census tracts.Footnote 2 To interrogate whether the observed positive correlation can be explained by other factors, we fit a series of normal linear models including covariate adjustment for potential confounders and conduct complementary sensitivity analyses.

Parler Videos

The full corpus of Parler data consists of nearly all public videos, and corresponding metadata files, uploaded between its launch in August 2018 and its removal from Amazon Web Services on January 10, 2021.Footnote 3 The metadata reference 1,032,523 videos, 58,680 of which both contain geolocation information and were uploaded from the United States. As Parler only gained widespread use in 2020—57,159 (97.41%) of U.S. videos were uploaded after January 1, 2020—we limit our analysis to the sample since the start of 2020.

Existing research shows Parler video uploads are associated with incidents of right-wing unrest (Karell et al. Reference Karell, Andrew, Edward and Edward2023), including the Capitol insurrection (Van Dijcke and Wright Reference Van Dijcke and Wright2021), supporting its validity as a measure of right-wing radicalization. Recording and uploading a video to social media requires greater effort compared to text posts to the same platform, and presents a higher risk of identification. As such, our measure is based on a more engaged and mobilized subset of users from the total user base.

Location

The empirical strategy requires that video uploads are assigned to users’ location of residence. In our manual review of 1% of uploaded videos, 27.62% contained footage of users filming video on televisions or computer screens, suggesting many are uploaded from users’ homes. One key challenge is videos uploaded at protests and rallies, possibly far from participants’ residence. To address this, we omit videos uploaded within 25 kilometers of a protest or riot recorded on the same day in the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED) (Raleigh et al. Reference Raleigh, Linke, Hegre and Karlsen2010).Footnote 4 Though reducing statistical efficiency, this reduces bias from including videos uploaded outside a user’s hometown.

The data lack personal identification information such that we are limited in the extent to which we can distinguish the number of unique users uploading videos from a particular location. To address this problem, we round longitude/latitude coordinates to varying degrees of specificity and drop duplicates: counting the number of unique (coarsened) locations rather than individual uploads. The results remain consistent across levels of aggregation.Footnote 5

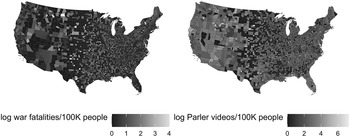

Figure 1 maps the number of video uploads and war fatalities, normalized by population, for counties in the contiguous 48 U.S. States.Footnote 6 Both variables are distributed throughout the country rather than concentrated in certain regions. Across all 3,222 counties, there are 1,529 with no fatalities and 879 with zero video uploads.Footnote 7 There are more counties with no fatalities and least one video uploaded (273) than those with at least one fatality and no videos uploaded (158). Figure 2 illustrates that the modal value for both variables is zero.

Figure 1. Logged and Population-Normalized Geographic Distribution of Parler Videos and War Fatalities

Figure 2. Logged Distribution of Parler Videos and War Fatalities

Independent Variable and Controls

We measure communities’ fatalities in U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan using iCasualties.org data, which tracks fatalities reported by official military and civilian agencies. It records the deceased’s name, date, service branch, location, rank, age, and hometown. We match the hometown to corresponding location in the U.S. Board on Geographic Names for entities.Footnote 8

All models include demographic controls, including measures of population, split into the racial categories used by the U.S. census. We also include the number of refugees settled in a county and the change in the nonwhite population between 2019 and 2010, as scholars suggest increasing ethnic diversity and demographic change may encourage radicalization. We also control for economic factors, including income, which is correlated with right-wing support and military enlistment, and trade shocks, as many suggest globalization has led to right-wing radicalization. We control for Republican Party vote share, which correlates with right-wing radicalization and military service. We control for broadband access, since it likely drives social media usage.

To control for military participation, we aggregate official Army Enlistment data to the county level.Footnote 9 We also use U.S. Census and American Community Values data on the total number of people in each census unit that report military service. We split both variables into military service before or after 2001 to account for potential heterogeneous effects and control for an older generation’s participation in the military, as military participation in the United States is highly clustered within families across generations. We control for proximity to a military base, as the hypothesized relationship may be driven by areas with high military participation.

To ensure measures are on similar scales, nonwhite population change, median income, level of education, trade shocks, and Republican vote share are all normalized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. Population variables (including demographics and military participation) are logged sums of the number of individuals in each category. For detailed descriptive statistics on the independent and control variables, see Section 7 of the Supplementary Material.

RESULTS

Figure 3 plots the bivariate relationship between war fatalities and the log of Parler videos uploaded at the county level, normalized by population. While a number of counties that experience no war fatalities do have a large number of video uploads, there is a strong positive correlation overall, as indicated by the regression line.

Figure 3. Bivariate Correlation between War Fatalities and Parler Participation at the County Level

Note: Both variables are jittered and normalized by population, and the number of videos is logged. Figure includes least squares line and 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4 presents the results from both regressions.Footnote 10 The relationship between war fatalities and Parler videos uploaded is positive and statistically significant in both the county and tract-level analyses. To probe the robustness of these results to alternative model specifications with various combinations of control variables, we conduct an extreme bounds analysis and find that the positive association between Parler video uploads and war fatalities is consistent across over eight thousand model specifications. The coefficient size is often larger than that in the models presented here, and always statistically significant. To probe robustness to unobserved confounding, we conduct a sensitivity analysis, which suggests that the association with unobserved confounders would have to be 25 times the magnitude of association with Republican vote share in order to completely explain the correlation between Parler video uploads and war fatalities at the county level,Footnote 11 which we have little reason to believe is feasible.

Figure 4. Linear Models Regressing Parler Video Uploads (Logged) on the Number of Iraq and Afghanistan War Fatalities and Covariates

Note: The county model includes fixed effects and clusters standard errors at the state level. The tract model includes fixed effects and clusters standard errors at the county level. Horizontal bands indicate 95% confidence intervals. Variables are grouped by color into categories: military participation, demographics, income, and general controls.

CONCLUSION

This research note complements existing explanations of right-wing radicalization in the United States with attention to the impact of foreign military engagements on radicalization at home. The findings show a strong correlation between areas in the United States whose residents have died in overseas wars and the level of participation in a radical-right social media website. The results are remarkably robust, and hold even when controlling for military participation. Beyond issues of racial animus, economic anxiety, or military participation itself, the harmful domestic repercussions of foreign military interventions are associated with right-wing radicalization in the United States. Future research should probe how demographics, economics, and the costs of wars interact to fuel the far right.

Many studies have focused on the determinants of voting for the far right or participating in far-right terrorism. Within these two poles lie a variety of nonviolent radical activism within a process of radicalization. The Parler data allow us to examine a common “gateway” form of radical-right activism, critical to the radicalization process, yet typically difficult to observe systematically. The findings show that these phenomena, largely thought of as driven by domestic factors, may have important international components.

Radicalism, including in response to foreign wars, can take a variety of forms. While we focus here on right-wing radicalization, these dynamics are not necessarily unique to the right. Further research is required to investigate whether there exists a similar association between war costs and left-wing radicalization. Future research may also investigate possible moderating factors unexplored here.Footnote 12 Is the association between war fatalities and radicalization weaker in economically prosperous areas? Our argument implies the rise of the far right in the United States may follow a different pattern than in Europe, where participation in overseas military engagements is much lower. Future research may explore common and divergent predictors of radicalization in Europe and the United States.

A key limitation to the analysis here is the imperfect mapping between the conceptualization of community as social network and the units of observation restricted to geographically defined units for which data are collected. The evidence presented motivates future research needed to interrogate further the theoretical mechanisms proposed, operating through social space.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055423000904.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4GLPII.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gregoire Phillips for substantial contributions to an earlier draft. We also thank Christopher Blair, Anna Meier, Meg Guliford, James Fearon, and seminar participants at Washington University in St. Louis, Perry World House, and the Workshop on Conflict Dynamics for helpful comments.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.