1. Introduction

Consumers are increasingly demanding sustainability in the goods they purchase, and the production and retailing industries are responding to this demand. Eco-labels, which refer to some form of distinct identifying mark, are used to provide information to the consumer about the sustainability of the product and allow for products to be differentiated in the marketplace (Gutierrez et al., Reference Gutierrez, Chiu and Seva2020).

Willingness to pay (WTP) is defined as the maximum amount of money someone would be willing to part with to obtain a welfare improvement, here understood to be the environmental benefits associated with the eco-label. It serves as a common measure of demand and pricing for eco-labeled products. In general, WTP for eco-labeled goods is thought to be higher than nonlabeled goods because of this increase in environmental benefits (Lim & Reed, Reference Lim and Reed2020). This price premium provides an important incentive for producers and retailers to engage with eco-labeling schemes, as it offers the potential for price premia to offset the costs of more sustainable production (Blomquist et al., Reference Blomquist, Bartolino and Waldo2015) and to access to new markets, niche markets, or even markets perceived as “luxury” (Fuerst & Shimizu, Reference Fuerst and Shimizu2016).

There are numerous consumer characteristics which are believed to underpin the price premium and WTP for eco-labeled products that consumers have, and these provide important reference points for segmenting the market. These include gender, age, income, education, and many more (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Hutchinson and Longo2020). Of course, the key predictor of WTP for an eco-labeled good should be the strength of the purchasers’ desire to protect the environment. However, other factors may be at play.

As a form of response bias, social desirability bias refers to the tendency of research subjects to provide responses (in this case, WTP for eco-labeled goods) that are not representative of their actual opinions or behaviors in the “real world,” but more akin to answers deemed appropriate by their social reference group (Beretvas et al., Reference Beretvas, Meyers and Leite2002). Underlying this is a desire to look more attractive or superior to others (impression management) or to deceive themselves that they are “better” than they actually are (Larson, Reference Larson2019).

As pro-environmental behavior increases and is seen as a social norm (Shafiei & Maleksaeidi, Reference Shafiei and Maleksaeidi2020), it holds that people would like to portray themselves as eco-friendlier. If a customer feels compelled to purchase an expensive eco-labeled product in a public marketplace, for fear of exposing oneself as operating contrary to established norms, that represents a negative outcome for the consumer, who may not truly desire the product (at its current price), but it still continues to benefit the producer and the wider environment.

It is known that there is an “attitude–behavior” gap, particularly in the purchasing of green products, whereby customers may hold environmental attitudes but not demonstrating them in their choice of goods (Dhir et al., Reference Dhir, Sadiq, Talwar, Sakashita and Kaur2021) If such a gap persists between what a potential customer indicates in a research setting and their actual behavior in the marketplace, then producers and the environment both face detriment. Thus, determining this relationship is key to ensuring the continued uptake and success of eco-labeling schemes.

It follows that in studies of eco-labeled product choice and WTP for these products that social desirability may play a role—as a noted factor in marketing research generally (Larson, Reference Larson2019) and directly influencing responses to eco-labeled products by producing over-reported or inflated estimates (Brécard et al., Reference Brécard, Hlaimi, Lucas, Perraudeau and Salladarré2009; Cerri et al., Reference Cerri, Testa, Rizzi and Frey2019a).

A wide body of research has identified this relationship between social desirability bias and increasing WTP (Wheeler et al., Reference Wheeler, Gregg and Singh2019). However, there have been studies which have distinctly found the opposite, using both correlational and experimental investigation.

Gallardo and Wang (Reference Gallardo and Wang2013) found no such relationship between social desirability bias and WTP for eco-labeled fruit. Their method employed direct and indirect questioning techniques, which have been known to show a difference in attitudes to eco-friendly products, which is often attributed to social desirability bias (Klaiman et al., Reference Klaiman, Ortega and Garnache2016).

Sörqvist, Haga, and their collaborators also found no such relationship between social desirability bias and WTP for eco-labeled goods such as light bulbs (Sörqvist et al., Reference Sörqvist, Haga, Holmgren and Hansla2015a), bananas (Sörqvist et al., Reference Sörqvist, Haga, Langeborg, Holmgren, Wallinder, Nöstl and Marsh2015b), and raisins (Sörqvist et al., Reference Sörqvist, Marsh, Holmgren, Hulme, Haga and Seager2016b), culminating in robust evidence that social desirability bias and WTP for eco-labeled goods had nothing to do with one another (Sörqvist et al., Reference Sörqvist, Langeborg and Marsh2016a).

Despite this supposed confirmation, social desirability bias is still a concern for researchers in this area (Cai et al., Reference Cai, Xie and Aguilar2017; Harms & Linton, Reference Harms and Linton2016; Slapø & Karevold, Reference Slapø and Karevold2019; Taufique et al., Reference Taufique, Vocino and Polonsky2017; Testa et al., Reference Testa, Iraldo, Vaccari and Ferrari2015), and is still being offered as an explanation for results (Barker et al., Reference Barker, Wong, Jones and Russell2019; Vecchio et al., Reference Vecchio, Decordi, Grésillon, Gugenberger, Mahéo and Jourjon2017) or acknowledged as a limitation for studies of WTP for eco-labeled products (Sogari et al., Reference Sogari, Mora and Menozzi2016; Vecchio & Annunziata, Reference Vecchio and Annunziata2015).

Here, a quantitative approach is proposed, with the introduction of a measured variable for the social desirability bias of individual participants, which would allow for it to be properly observed and controlled for (Ventimiglia & MacDonald, Reference Ventimiglia and MacDonald2012). This is common in other fields such as health (Bidaki et al., Reference Bidaki, Majidi, Ahmadi, Bakhshi, Mohammadi, Mostafavi, Arababadi, Hadavi and Mirzaei2018; King et al., Reference King, Cespedes, Burden, Brady, Clement, Abbott, Baughman, Joyner, Clark and Pury2018), personality studies (Fernandez et al., Reference Fernandez, Woldgabreal, Guharajan, Day, Kiageri and Ramtahal2018), and research into illegal or undesirable behavior (McClanahan et al., Reference McClanahan, van der Linden and Ruggeri2019), arguably situations in which people would be most likely to mispresent themselves, but is rarely implemented as a research technique in these types of valuation studies (Cerri et al., Reference Cerri, Thøgersen and Testa2019b). Sörqvist et al. (Reference Sörqvist, Marsh, Holmgren, Hulme, Haga and Seager2016b) are one of the few examples of this method being directly applied to WTP for eco-labeled products. In conjunction with an incentive-compatible, demand-revealing experiment, such as a Vickrey auction (Vickrey, Reference Vickrey1961), it would clearly determine if high WTP values are directly a result of social desirability bias.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine if social desirability bias predicts a consumer’s WTP for eco-labeled goods. This was achieved through an experimental auction approach, using a self-selection sample of Northern Irish adult consumers. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is one of only a few papers to directly address this issue in WTP for eco-labeled goods, and the first does so in the context of an incentive compatible experimental auction.

This paper commenced with a discussion of the relevant background to the relationship between social desirability and eco-labels. Next, the methods used are presented, followed by the results and a discussion of the significance of these findings. The paper concludes with a discussion of the limitations of the study and suggests opportunities for future research.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

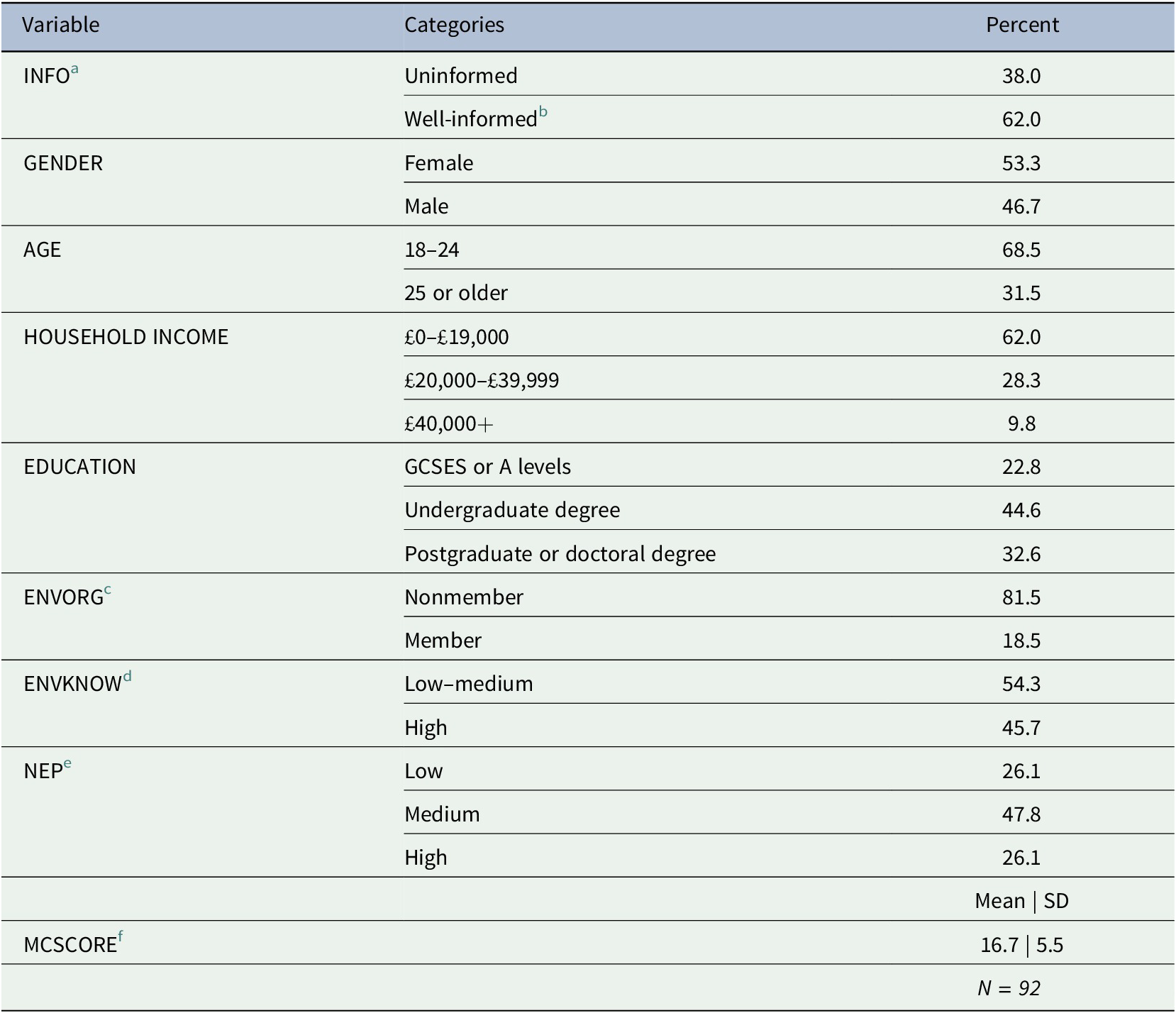

The target population was identified as a “Northern Irish consumer,” proposed to be a Northern Ireland resident of any gender aged between 18 and 65. Following ethical approval, participants were recruited from among staff and students of Queen’s University Belfast, using primarily volunteer self-selection and snowball sampling methods (Sharma, Reference Sharma2017). The final sample size was 92, and, as reported in Table 1, was fairly evenly balanced for gender, with most participants aged 18–24 (68.5%), largely educated to undergraduate level (44.6%), and mostly had an annual household income less than £20,000 (62%).

Table 1. Variables of interest and sample characteristics

a Treatment for information effects.

b See methods for a description of these treatments.

c Membership of an environmental organization.

d Self-rated knowledge of environmental issues.

e New Ecological Paradigm score.

f Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Bias score.

2.2 Design and Procedure

Recruited participants were assigned to cohorts of 20 and cross-matched for age and gender where possible. There were eight 1-hr-long laboratory sessions in total (expected sample size of 160), but with 25–50% no-shows in most cohorts, the realized sample size was 92.

The experiment constituted a second-price, sealed-bid Vickrey laboratory auction. Here, the highest bidder wins the auction, but pays the runner-up’s bid as their final price. Therefore, as the winner cannot influence the outcome of the auction by overbidding or underbidding, they are incentivized to bid only their true WTP (Milgrom, Reference Milgrom2021). Participants were further incentivized to bid their exact WTP by being informed that the auction winner would also have the value of the winning bid deducted from their participation fee of £20.

After having the rules of the auction explained to them, participants were simultaneously shown the test goods: two wooden kitchen spoons, one of which was eco-labeled and the other not. Both goods were identical in physical characteristics. Participants were invited to examine the goods, and then, depending on the cohort, exposed to one of two information treatments. Well-informed participants (62% of sample) were told that eco-labeled good was “made from wood from FSC-certified forests. This means that the forest it came from was managed in such a way to prevent negative impacts on local wildlife, water bodies, and air quality,” while uninformed participants (38% of sample) were only told that the eco-labeled good was “environmentally friendly and came from a sustainable forest.”

Following this, the auction began, administered via computers using the z-Tree software for economic experiments (Fischbacher, Reference Fischbacher2007). Bids for both goods were entered simultaneously, and this was repeated three times. As previously explained to participants, at the conclusion, one good and one of the three bids for it would be chosen at random as final and binding, further increasing the incentive compatibility of the experiment. Please consult Higgins et al. (Reference Higgins, Hutchinson and Longo2020) for a further description of the auction experiment method.

2.3 Measures

Following completion of the bidding, but before the results of the auction were revealed, participants completed a short onscreen questionnaire. They were first asked to provide details of their gender, income, age, education, and membership of an environmental organization. They were then asked to self-rate their environmental knowledge as either “I know a lot about environmental issues,” “I know a little about environmental issues,” or “I do not know anything about environmental issues.”

Next, participants were asked to measure their environmental consciousness using the Revised New Ecological Paradigm (NEP), a 15-statement scale answered on a 7-point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree (Dunlap et al., Reference Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig and Jones2000). This generates final scores out of 105 for each participant, which are divided into three quartiles. Those scoring in the upper quartile are coded as high, middle quartile as medium, and lower quartile as low in respect to their environmental consciousness.

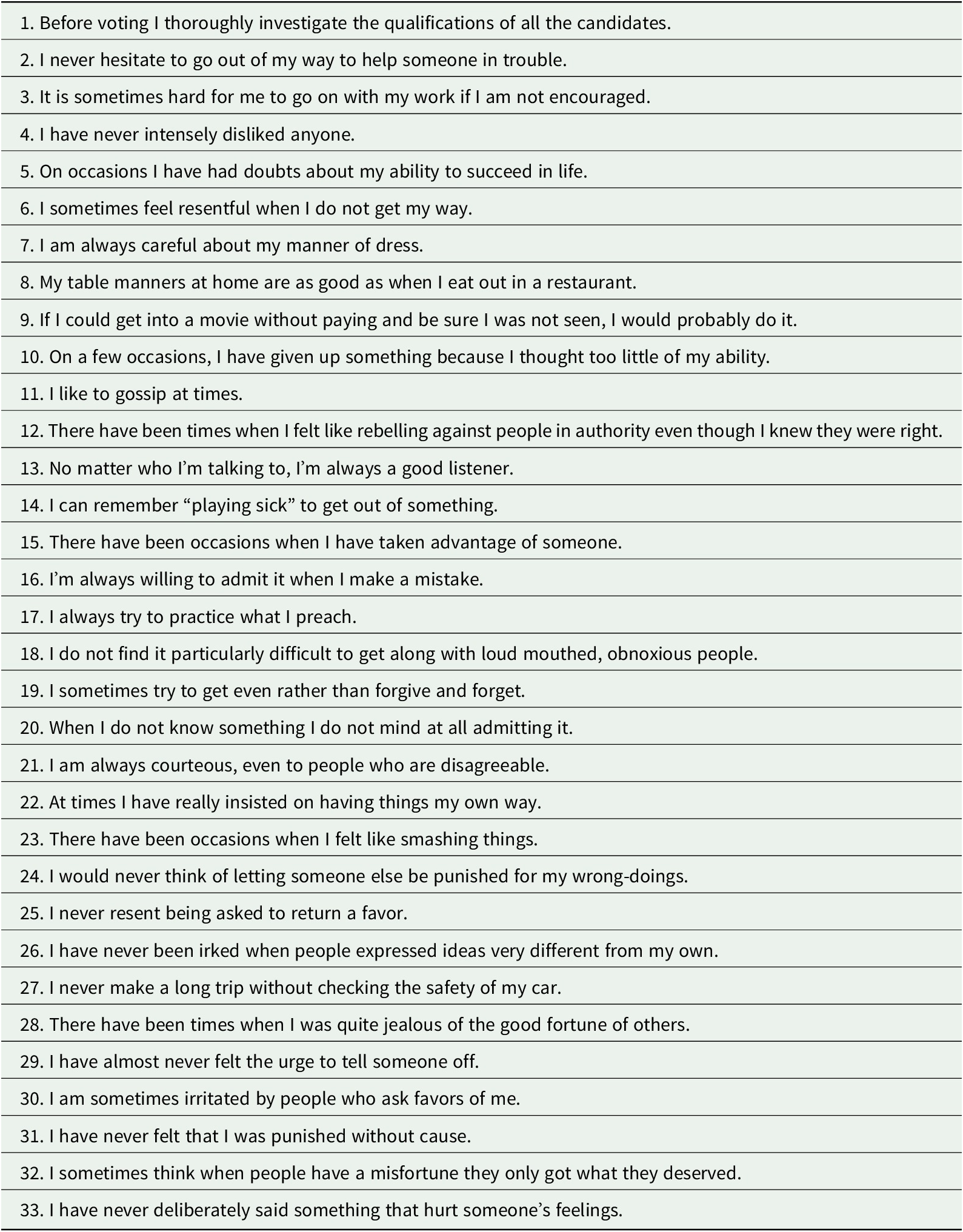

Finally, the participant’s vulnerability to social desirability biased was measured using the Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSCORE; Crowne & Marlowe, Reference Crowne and Marlowe1960). The participant answers 33 true or false questions (as described in Table 2), receiving a point for each response that is considered socially desirable. The higher this score, the more likely social desirability bias is occurring in that participant’s thoughts and behavior. Typically, the shorter forms of this scale are used (Sörqvist et al., Reference Sörqvist, Haga, Langeborg, Holmgren, Wallinder, Nöstl and Marsh2015b), but the long form was used here with the intention of increasing validity and reliability of the scale.

Table 2. Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale

The auction concluded with the private reveal of the winner, who received their randomly chosen good, and the final payment of the fee to participants, minus their randomly chosen bid in the case of the auction winner.

3. Results

The data from all 92 participants were retained for analysis. The characteristics of this sample are reported in the Methods section and in Table 1. The participants were mostly nonmembers of environmental organizations (81.5%), with low-to-medium environmental knowledge (54.3%) and a medium level of environmental consciousness (47.8%). The participants had a moderate level of social desirability bias (M = 16.7, SD = 5.5), with 6 participants having a low level, 57 having a medium level, and 29 having a high level.

Combining the bids for all three rounds for both goods showed a higher mean bid for the eco-labeled good (£1.83) than the standard good (£0.90), with the presence of an eco-label having a significant main effect on the bid offered (F(1, 550) = 111.61, p < .001). When social desirability was incorporated into the model, the eco-label continued to have significant main effect (F(1, 549) = 111.41, p < .001), but there was no effect of social desirability on the bid offered (F(1,549) = 0.01, p = .94).

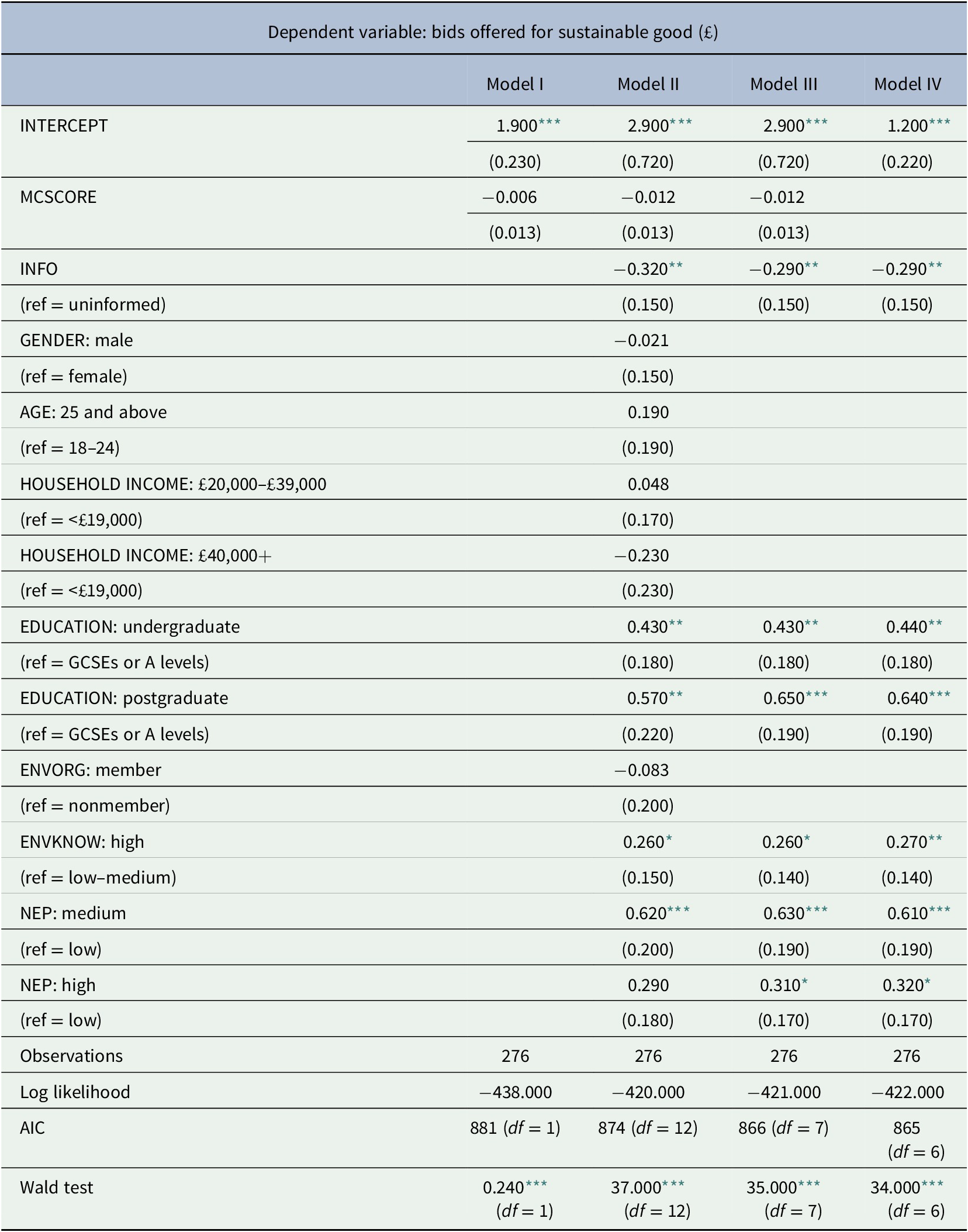

The results of the regression models are reported in Table 3. Using only the bids for the eco-labeled good, a Tobit model was estimated to explore the relationship between WTP and proneness to social desirability bias as measured by the MCSCORE. MCSCORE was not a significant predictor (β = −0.006) of WTP. The model was re-estimated using all predictor variables measured (Model II) and then with only the significant predictor variables (Model III). Across all three models, MCSCORE was a weak predictor and not significant. It was then dropped from the model (Model IV), and the Akaike Information Criterion score improved, indicating a better goodness of fit without the MCSCORE variable. The final model instead included the information treatment, and the education, environmental knowledge, and environmental consciousness of the participants.

Table 3. Tobit model results

* p < .1.

** p < .05.

*** p < .01.

4. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to determine if social desirability bias is a significant predictor of WTP for eco-labeled goods. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, it is only one of a few studies to address this relationship, and the first to provide confirmation through the use of an experimental auction approach, combined with the use of the full MCSCORE.

The results of this study show that, although people are willing to pay more for eco-labeled products, social desirability bias is a poor predictor of WTP for eco-labeled goods. In line with previous studies, social desirability bias does not seem to influence WTP for eco-labeled goods (Gallardo & Wang, Reference Gallardo and Wang2013; Sörqvist et al., Reference Sörqvist, Haga, Holmgren and Hansla2015a; Reference Sörqvist, Haga, Langeborg, Holmgren, Wallinder, Nöstl and Marsh2015b; Reference Sörqvist, Langeborg and Marsh2016a; Reference Sörqvist, Marsh, Holmgren, Hulme, Haga and Seager2016b). Instead, other factors emerge as much stronger predictors of WTP, including information provided by the label, and the levels of education, environmental knowledge, and environmental consciousness of the participants. Specifically, the last factor indicates that participants are indeed reflecting their concern for the environment in their choice and valuation of environmentally friendly goods.

Therefore, it would hold that the traditional theory about eco-labels is true: purchase behavior is positively and significantly related to internal desires to protect the environment, rather than any desire to deceive oneself or the experimenter based on the affirming social reference group. It could be argued then, that pro-environmental behavior, such as choosing eco-labeled goods, has moved from a perceived, injunctive, or subjective norm that is largely socially performative, to a collective or descriptive norm, that it is simply what is now done (Chung & Rimal, Reference Chung and Rimal2016).

An alternative explanation is that the auction experiment used here is entirely incentive-compatible and demand-revealing (Noussair et al., Reference Noussair, Robin and Ruffieux2004), and that the participants had no choice but to reveal their exact WTP, free from social desirability bias. Social desirability bias is based on the theory that there are risks to answering truthfully but very few rewards for doing so (Cerri et al., Reference Cerri, Testa, Rizzi and Frey2019a), but here, the participant anonymity, lack of outcome control, and the participant’s risk of losing a real-world financial endowment by bidding in a socially desirable way may have overridden this impulse to answer in a biased manner.

For researchers, these results may suggest that, while it is good practice to attempt to test and control for it, incentive compatible WTP studies, for eco-labeled products at least, are somewhat free from social desirability bias. Researchers can test and be assured of this by incorporating a measure of social desirability bias such as the MCSCORE.

For marketers, the findings may suggest that marketing campaigns relying on the influence of social norms to encourage purchase of eco-labeled or other green goods are perhaps not as efficient as previously thought and should instead focus on activating the environmental concern possessed by the potential customer, perhaps through information campaigns and the design of the product information and the label itself.

The authors propose the following limitations to the study. First, the sample size is rather small, but small samples are common in experimental research such as this and should be sufficient for a confirmatory study. The sample itself approximates a volunteer, self-selection sample made up mostly of students, but if anything, these are the people considered most likely to display social desirability bias (Hood & Back, Reference Hood and Back1971), lending weight to the theory that social desirability bias does not predict WTP for eco-labeled goods, even among this group of subjects.

Second, the findings for this good (wooden kitchen spoon) may not generalize to other goods. These particular goods were chosen as participants would have a high degree of familiarity with them, given that low product involvement (familiarity with use, attributes, and alternatives) can create inaccuracies in valuation (Park & Keil, Reference Park and Keil2019). However, these simple goods do provide a strong, bias-free foundation for valuation work.

Third, the use of the MCSCORE may not have been appropriate, due to either an overall lack of validity, or decreased validity in this particular application (Uziel, Reference Uziel2010). It may not truly capture the self-deception aspect of social desirability bias (Leite & Beretvas, Reference Leite and Beretvas2005). Crowne, one of the creators of the scale, was himself critical of its deployment as a control mechanism in experimental research and stated that any belief that it can decontaminate the research or its variables is flawed (Crowne, Reference Crowne1991). While concerns about the reliability and validity of this scale persists, particularly among male participants (Beretvas et al., Reference Beretvas, Meyers and Leite2002), it still consistently outperforms other scales in detecting social desirability bias (Vésteinsdóttir et al., Reference Vésteinsdóttir, Reips, Joinson and Thorsdottir2017).

Future research could repeat similar experiments, perhaps using a larger probability-based sample, for a wider range of eco-labeled goods with different eco-labeled types and using alternative scales of social desirability bias that are available (Uziel, Reference Uziel2010).

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the NI Department of Agriculture, Environmental and Rural Affairs for supporting the research through their generous Postgraduate Studentships.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authorship contributions

K.H. conceived and designed the study and carried out data analysis and data collection. A.L. and G.H. contributed to the experimental design and advised on the analysis. All authors contributed equally to the writing of the article.

Data availability statement

Please contact the corresponding author to access this dataset.

Comments

Comments to the Author: The paper is well developed and offers important insights to scholars. I suggest to add some caveats related to the use of only one product type (wooden kitchen spoons). I also advice Authors to better clarify the number of participants in each experimental session (92:8?) and its length.