The research we carried out was motivated by the new coronavirus (CoV) pandemic. This coronavirus is known as SARS–CoV–2, and the disease that causes it is known as COVID–19 (an acronym for “coronavirus disease”). COVID–19 is a rapidly spreading infectious disease that was first detected in December 2019 in China, specifically in Wuhan City, Hubei Province. There, an outbreak of pneumonia with an unknown cause attracted international attention due to its rapid spread and resistance to known medical treatments (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Horby, Hayden and Gao2020). The infection is highly contagious and transmitted through direct contact with the virus in the host’s respiratory tract. COVID–19 was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11th, 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020).

The situation that led to the coronavirus problem has prompted governments to intervene directly by enacting emergency measures that could prevent and, at the same time, slow the spread of COVID–19. One of the most important measures has been to isolate the population in their homes, avoiding all social contact and participation in public gatherings, along with encouraging strict hygiene measures, especially handwashing with soap and water. All these developments have taken place very quickly, and they were probably unimaginable before December 2019. Certainly, an in-depth study should be carried out on the stress the coronavirus problem may be producing in society as a whole. Messages of mass confinement in the home for an undefined period, along with government orders and decrees to stay at home and isolate themselves socially, are new to citizens, and it is difficult to know how they will react individually and collectively.

During the lockdown, there are restrictions on the movements of citizens, who must stay at home in order to keep an asymptomatic person from transmitting COVID–19 and, thus, protect the most vulnerable people. The virus can be transmitted before the infected person has symptoms, so that individual and collective behavior is beneficial in reducing the virus’s transmission and saving lives (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Heesterbeek, Klinkenberg and Hollingsworth2020). With this in mind, the Spanish government declares a state of alarm and prohibits people from going out on the streets from March 14th on, except to visit the doctor, go to essential jobs (e.g., health care), and take care of those who need it or buy supplies. As in Spain, Colombia adopted total confinement for the first time beginning on March 25th. However, the Chilean government used the strategy of applying mandatory quarantines in the communes, where the percentage of hospital care is at 90% of its capacity. In these three countries, the headlines summarize this quarantine campaign as “stay at home” and “we can stop this virus together”. The strategy is based on promoting collective action, with individual behavior being fundamental and necessary for success or for ultimately achieving the common good. Therefore, these are individual actions of commitment to the social or collective group, which can be one’s family, city or town, country, or the world.

From governments and public and private institutions, as well as the media, messages are being sent to the population to take an active individual stance in this pandemic situation and correctly follow the instructions contained in the messages that, using different rhetoric, refer to staying at home. Transparency, public commitment, and social action are three basic concepts that government messages should promote in a national and pandemic emergency situation (World Health Organization, 2007). The public health measures adopted must be based on the best scientific evidence available, in order to contain the spread of the disease or reduce its impact. Therefore, the message delivered must emphasize the importance of citizens’ behaviors and moral obligations in an attempt to create a social norm linked to specific behaviors such as hand washing, avoiding public gatherings, and isolating oneself at home. In short, isolation, quarantine, border control, and social distancing measures are basic actions used to control a pandemic (World Health Organization, 2007).

The COVID–19 pandemic and its rapid evolution require political intervention through effective and appropriate messages so that the population will follow their indications. These measures will produce rapid changes in citizens’ daily behavior and have important effects on their lives, including high personal and economic costs, emotional imbalance, and family problems (World Health Organization, 2018). The way the danger of contagion is communicated is critical, especially when the perception of risk occurs in a situation where the population does not yet seem to appreciate the devastating consequences the pandemic is causing globally. New social behaviors are fundamental and necessary in controlling the pandemic. For this reason, we think the analysis of the content of the messages offered to citizens is an important variable that requires a study that provides information about how to guide the population’s behavior in a new, stressful situation that limits personal freedom and can have negative personal, economic, and family consequences (Betsch et al., Reference Betsch, Wieler and Habersaat2020; Glik, Reference Glik2007; World Health Organization Europe, 2017).

The main aim of our research is to analyze the effects of different messages and relate them to moral behavior and personal decisions in a global health crisis like the COVID–19 pandemic. The aim is to identify which moral message best ensures the individual actions needed to face the virus’s spread. The aim is to link the problem of the public health emergency to the ethics and values of messages designed to promote a more effective social response that would mitigate the health problem (Jennings & Arras, Reference Jennings and Arras2008).

The research aimed to replicate the messages used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), which, within a public health framework, analyses the effect of moral messages on behavioral intentions during the COVID–19 pandemic. The design includes presenting a message elaborated in the format of a Facebook message (there are four messages, with one message randomly assigned to each participant) whose content reflects a moral tradition: Deontological ethics, utilitarianism, and promotion of virtue. Additionally, a control group is included where the message offers no moral information. Human behavior involves making choices that can sometimes have a moral dimension. The three moral messages represent a different theoretical line of research on moral behavior. We have not performed an exact replication. In our research, two modifications were made in the study design:

1. The question related to opinions about the most effective message to persuade someone to take steps to reduce the spread of coronavirus and stay at home was presented in the survey before the message received in the experimental condition. In the Everett et al. study (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), this question was presented after the messages. We aimed to test whether the Facebook message received produces any change in the participant’s previous opinion; if so, we would have prior evidence that the message has an effect.

2. The same sender of the message (a professor) was used in all the experimental conditions, given that its effect was trivial in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020); moreover, because it was not the target of our analysis, its possible effect was controlled for constancy.

Message Effect and Moral Behavior

Behavior can be explained by several factors, such as the individual’s value and belief systems from the early years of his/her socialization. These systems are continually reinforced by different messages from the social environment that point to behaviors that are considered good or bad. In this regard, public messages convey morally approved information and are therefore strong enough to reinforce behaviors that are considered positive or good (van Bavel et al., Reference van Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020). Messages convey an action pattern and aspects linked to the morality of doing, and they are learned and shared by individuals in a community. For this reason, it is advisable to use messages that are supported by endogroup norms, given that they will be more effective because they impact people’s sense of belonging (van Bavel et al., Reference van Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020). For example, during the avian flu outbreak at the beginning of the 21st century, Kelly and Hornik (Reference Kelly and Hornik2016) found that messages designed to prevent the transmission of the virus in the community were more effective than arguments focused on personal protection.

Researchers have studied whether the type of moral argument used in the message is related to its persuasiveness (Wheeler & Laham, Reference Wheeler and Laham2016). The results indicate that moral messages that focus on other people’s well-being are more effective than messages that focus on personal characteristics (Luttrell & Petty, Reference Luttrell and Petty2021). Along these lines, Luttrell et al. (Reference Luttrell, Philipp-Muller and Petty2019) note that messages with a moral connotation are more persuasive and more significantly affect attitudes than those that allude to a practical behavioral argument. The literature explains that this occurs because when morality is relevant to a particular issue, people follow the recommendations. After all, these concerns are related to their belief system. Thus, people tend to perform the expected behavior expressed in the message, especially when someone close to them may be affected. However, this could also be determined by the person’s fear of being perceived as selfish (van Bavel et al., Reference van Bavel, Baicker, Boggio, Capraro, Cichocka, Cikara, Crockett, Crum, Douglas, Druckman, Drury, Dube, Ellemers, Finkel, Fowler, Gelfand, Han, Haslam, Jetten and Willer2020) or the fact that a different action could challenge the basis of their emotional structure, which is highly valued in society (Wheeler & Laham, Reference Wheeler and Laham2016). Undoubtedly, social behavior patterns that seek to help others are determined by moral principles (Luttrell & Petty, Reference Luttrell and Petty2021).

Traditionally, consequentialism and deontological ethics are two theoretical ethical perspectives that have been used to explain moral decisions (Cejudo Córdoba, Reference Cejudo Córdoba2019; Kahane et al., Reference Kahane, Everett, Earp, Caviola, Faber, Crockett and Savulescu2018). Moral decisions will vary depending on the individual’s moral ground, and this is where the deontological perspective appears to have the most significant impact in the social area (Wheeler & Laham, Reference Wheeler and Laham2016).

Consequentialism, which judges whether an action is good or bad depending on the expected consequences, is described as a feature of utilitarianism. Thus, what is correct is defined as maximizing what is good, but what is good is defined independently of what is correct. Acting correctly means doing something for our wellbeing or the wellbeing of others. It has to do with producing the greatest possible good, that is, achieving the best consequences. Therefore, ethical behavior is based on seeking the greatest happiness or wellbeing for the greatest number of people. In this current context of public health risk and emergency, it would involve maximizing the population’s health (Bellefeur & Keeling, Reference Bellefeur and Keeling2016).

By contrast, deontological ethics propose that the moral value of a behavior should not only be judged by its consequences. In other words, one should act in a certain way because this behavior is morally correct, and not because it leads to a greater good. From this perspective, the right thing is defined independently of what is good. A person’s duty is to perform good behavior (and not bad), without prioritizing the consequences. Deontology is ethics of responsibility and duty. From a public health perspective, it is about acting to protect members of society.

The ethical virtue-based model is based on the concept of ideal qualities or traits that should govern behavior and define a good person by his or her virtues, e.g., charity, altruism, compassion, generosity, respect for others, empathy, trust in society. In short, the individual’s moral character promotes what is good (Goncalves & Santos, Reference Goncalves and Santos2017).

The Present Study

Our study focuses on what people think and feel about COVID–19 and the impact of different messages designed to activate public health behaviors. It was led by three research teams from three countries: Spain, Chile, and Colombia. The study covers a wide range of issues, such as anxiety, worry, moral behavior, the future of humanity, or coping with the pandemic, and it analyses the type of content in the most effective messages to persuade citizens to follow the government’s instructions to stay home and avoid contagion. Specifically, our study has three objectives.

First, we will check the persuasion level of the three moral messages and the control message in each of the three countries that participated in the study (Spain, Colombia, and Chile), focusing on two aspects: The behavioral intentions of the participants themselves and their beliefs about others’ behaviors. Four variables are measured in these two situations: The probability of washing their hands, participating in public gatherings, avoiding all social contact, and sharing the Facebook message they received. Our study uses the four types of messages used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), as well as four of its dependent variables; only the photo in the Facebook message has been changed. In our study, the person’s leadership in sending the message on Facebook was not manipulated because Everett’s study obtained an irrelevant effect. For all the messages, the sender is a university professor. Therefore, the study is carried out with participants from Spain, Colombia, and Chile, and the country variable is introduced in the design as a factor that could moderate the effect of the messages. The country of residence could be a source of differences because the pandemic’s development and the government guidelines could differ, thus affecting citizens’ attitudes and behaviors. Our research uses a control message that does not allude to any type of moral value or behavior and three moral messages to encourage people to stay at home and follow the hygiene and social isolation guidelines promoted by the government: A message that highlights the consequences of the conduct (utilitarianism), a message that refers to duty and responsibility (deontological ethics), and a message that emphasizes the positive trait of being a good and honest person (virtue-based ethics). An essential aspect of the studies carried out on human behavior during a pandemic and global health emergency is the novelty of this situation. It presents an opportunity to study classic behavioral variables in this new context of a global health risk, which may involve changes in the classic findings due to the introduction of the population’s individual and collective risk perception as a variable.

Participants’ opinions related to the second and third objectives are recorded before they read the Facebook message. The second objective is to analyze the participants’ degree of concern about the coronavirus problem. This objective includes analyzing a set of variables that contextualize the situation of concern perceived by the participants, such as country of residence, gender, age, or perception of global and personal threat.

The third objective is to analyze their views about the degree of effectiveness of three moral messages (deontological, utilitarian, and virtue-based) in reducing the spread of COVID–19 through the behavior of staying at home. This variable is the same one used by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), but in our study, it is presented before the Facebook messages because we want to find out the participants’ beliefs without the possible influence of the type of message received. In addition, this variable is used to test whether the message produces a change in participants’ opinions, that is, if the message designed in the study causes the participants to change their previous opinion about the moral message and, following the instructions in the message, value the measured variables of the probability of washing their hands, participating in public gatherings, staying at home/avoiding social contact, and forwarding the message to inform more people. Furthermore, we controlled that the participants in the sample correctly identified the profession of the sender of the message and, therefore, had actively read the message. To carry out the analysis, the participants who chose the option of the deontological message or the utilitarian message as the most effective message were divided, in each case, into three groups according to the message they received by chance. It was not possible to carry out this analysis with the ethical virtue message group because very few participants selected it as the most effective message. Finally, to verify whether receiving a message that matches the participants’ preferences produces a greater persuasion effect, the matches and non-matches are analyzed in the case of both the deontological message and the utilitarian message (Teeny et al., Reference Teeny, Siev, Briñol and Petty2021).

Method

Sample

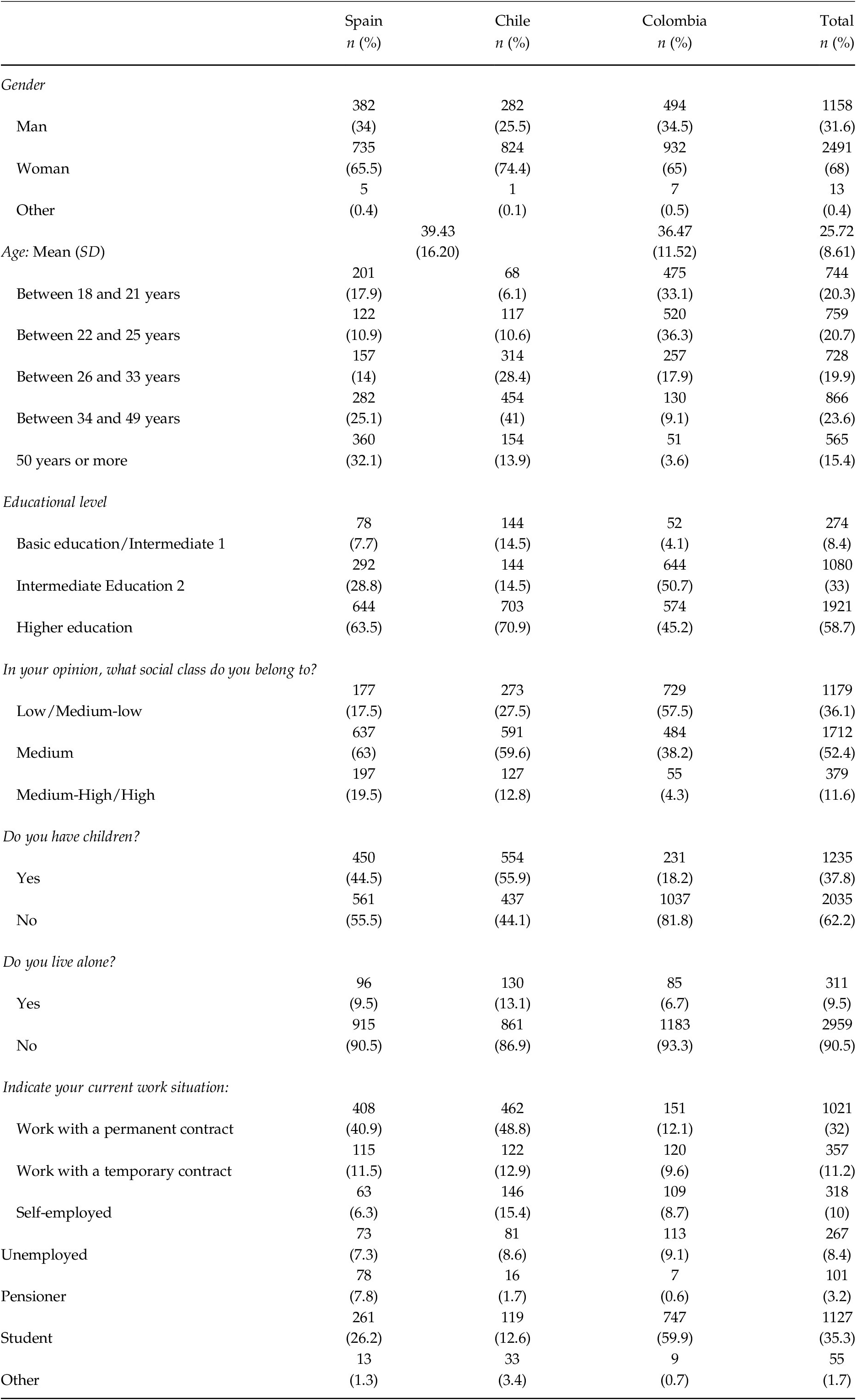

The study sample was a self-selected convenience sample composed of 3662 participants who currently reside in their country, Spain, Chile, or Colombia, 1,158 men (31.62%) and 2,491 women (68.02%), 13 other (0.4%), with a mean age of 33.17 years (SD =13.65, Mode = 22, Median = 29, minimum = 18, maximum = 94). For each country, the sample size was: Spain = 1,122, Chile = 1,107, and Colombia = 1,433. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and context variables for each country and the total. To analyze the sex variable, self-identified gender groups were used, such as man or woman (n = 3,649).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Context Variables for the Participants Surveyed

Instruments

Socio-demographic variables. Gender (man, woman, and other), age, having children (yes/no), living alone (yes/no), perceived social class (low/medium, medium, medium/high), and country of current residence, checking that it coincides with their nationality (Spain, Chile, or Colombia). Age was categorized in four levels: 18–21, 22–25, 26–33, 34–49, and 50 years or more.

Educational level. The declared level of education was divided into three levels: (a) Basic education (basic/initial/primary school) and intermediate education Grade 1 (EGB/ESO/junior high/polymodal/diversified); (b) intermediate education Grade 2 (FP/professional modules/high school/higher technical); and (c) higher education (bachelor’s degree/5-year university degree/master’s degree/teaching credential/ pre-doctorate/doctorate).

Work situation during the coronavirus problem. The employment situation was measured with seven categories: Work with a permanent contract, work with a temporary contract, self-employed, unemployed, pensioner, student, and other type of work or situation.

Perceived Social and Emotional Context: Degree of Concern, and Perceived Personal and Global Threat

Concern about the coronavirus problem. The degree of concern about the coronavirus problem has a response scale that ranges from not concerned at all (0) to quite concerned (10).

Perception of personal and global threat. The survey has two questions related to the perceived threat of the coronavirus: The perception of the degree of threat to the world population and the degree of perceived personal threat. The response scale ranges from no threat (0) to a high threat (7). This question is the same one used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020).

Opinions about the most effective moral message to persuade someone to take steps to reduce the spread of coronavirus and stay at home. This question is asked before performing the experimental manipulation with the moral messages and in the control group. It has three response options, and the participant must select one:

1. “We all need to stay home, no matter how difficult it is, because these sacrifices are nothing compared to the much worse consequences for everyone if we carry on as usual. Think about the consequences and stay home”.

2. “We all need to stay home, no matter how difficult it is, because that is what a good person would do. Think about the people you admire morally; what would they do? Be a good person and stay home”.

3. “We all need to stay home, no matter how difficult it is, because it is the right thing to do; it is our duty and responsibility to protect our families, friends, and neighbors. It is your duty to protect others and stay home”. This question is the same one used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020).

Experimental manipulation and variables measured. One of the four messages is randomly assigned to each participant: There are three moral messages and one control message without any moral indication. This task and the questions are the same as the ones used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020). The introduction to the messages is identical in all cases: “If my experience as a university professor has taught me anything, it is this: STAY HOME, even if you don’t feel sick. The coronavirus is contagious even before you have symptoms”. Next, and changing the paragraph, the sentence that identifies the condition of the experimental manipulation is introduced. Message 1, the deontological ethical message: “We all need to do this, no matter how difficult it is, because it is the right thing to do: It is our duty and responsibility to protect our families, friends, and neighbors. IT IS YOUR DUTY AND RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT OTHERS.” Message 2, the utilitarian ethical message: “We all need to do this, no matter how difficult it is, because these sacrifices are nothing compared to the much worse consequences for everyone if we carry on as usual. THINK ABOUT THE CONSEQUENCES”. Message 3, ethical virtue message: “We all need to do this, no matter how difficult it is, because it is what a good person would do. Think about the people you admire morally; what would they do? BE A GOOD PERSON”. Message 4, control message: “We all need to do this, no matter how difficult it is”. The messages looked like a Facebook message, including a picture of the sender. Next, there was a question to check that the recipient had read and understood the Facebook message: What is the sender’s job? The response options were presented randomly: Fire fighter, professor, police officer, and mechanic. Only the participants who responded with the correct choice of professor were included in the sample. After reading this Facebook message and taking its instructions into account, participants had to answer a few questions. They were presented with four questions about their own behavioral intentions, followed by the same four questions, but in this case referring to the behavior of someone who could see the same message and giving their opinion about how that person would act. The response scale in all cases ranged from extremely unlikely (1) to extremely likely (7). The questions are the following: How likely is it that you will always wash your hands whenever you enter work or come home, for at least 2 weeks, even if you don’t feel sick. Example of beliefs about other people’s behavior: “In your opinion, for a person who reads that Facebook message and takes its indications into account, how likely is it that…”). How likely is it that you will participate in public gatherings, for at least the next 2 weeks, even if you don’t feel sick now? How likely is it that you will stay home and avoid all social contact for at least the next two weeks, even if you don’t feel sick now? In addition, how likely is it that you will share the Facebook message you read on your social networks?

Procedure

The samples in our study completed an online survey voluntarily and anonymously. The data analyzed in this research were collected between March 25th and April 21st. This is a non-probabilistic sample. Before the survey began, participants agreed to collaborate in the study by confirming that they had read the information and had had the opportunity to ask questions in the emails provided in the welcome message. In this way, the ethical requirements suggested for research in the context of COVID–19 were met (Inchausti et al., Reference Inchausti, García-Poveda, Prado-Abril and Sánchez-Reales2020). The multi-centre research was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Tarapacá (Chile). The message distributed through different media to encourage participation in the study was the following: “HOW ARE YOU? University of Valencia (Spain), ESIC Business & Marketing School (Spain), the University of Tarapacá (Chile), and the University of Magdalena (Colombia) want to ask you. We are carrying out a study to understand how society as a whole feels and acts in the face of this unprecedented health and social crisis, and for this purpose, we need 15–25 minutes of your time. We need to receive many and diverse responses, and so we would appreciate it if you would help us to make the survey link go viral. If you can, please share it with all your WhatsApp and social network contacts. Thank you very much!”.

The survey was distributed through WhatsApp and other social networks (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn), as well as on the ResearchGate profiles of the team members. Furthermore, in Spain, the University of Valencia, and the University Pompeu Fabra collaborated by putting the link in the news section of their institutional websites, and the Association of Retired People of the University of Valencia (APRJUV) y la Asociación Española de Metodología de las Ciencias del Comportamiento (AEMCCO) distributed the link among all their members. A large number of university lecturers also directly collaborated in the survey’s dissemination. In Chile, the invitation was announced in the Network of Schools of Social Work belonging to universities of the Council of Deans of Chilean Universities, in a newspaper with electronic circulation in the city of Arica, in dance groups, and in groups of Scout leaders. In Colombia, the survey was sent via email through the University of Magdalena databases and by telephone.

The minimum sample size required for type I (α = .05) and type II (β = .20) statistical errors was calculated with an a priori power analysis (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009; Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, Pascual, Frias, van Krunckelsven and Murgui2008), and the effect size of the four messages was set to be small (f = 0.10) (estimated based on the results from Everett et al., Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020 with the four message conditions for an F-test of a univariate ANOVA with four groups). A priori statistical power analysis (four conditions, α = .05, 1 – β = .80, and f = 0.10) showed a minimum sample size of 1096 participants. The criterion for finalizing the data collection was that the three countries had to have a sample size of at least 1096 participants, after passing through the filter that the sender of the message had to be a professor. In the three countries, the sample size exceeded the minimum required (Spain = 1,122, Chile = 1,107, and Colombia = 1,433). If the sample size is set at 1,107 (the country with the lowest number of observations in our study), an a posteriori power analysis indicates that the F-test could detect the expected effect size of f = 0.10 (four conditions, α = .05, 1 – β = .80) with a power of .81. A sensitivity analysis with the entire study sample (N = 3622, α = .05, β = .20) showed that the main effect of the F-ratio of the four messages would have a high probability of detecting a very small effect size (f = 0.05).

An analysis of the survey follow-up indicates that the sample of participants who answered any of the questions is 5369. For the present research, we controlled that the participants completely answered the questions related to the effect of the messages because this is the variable with four groups (N = 3,622). There are some variables that were measured after the message, and on those questions, the sample size decreases. Participants who did not adequately select the profession of the sender of the message were eliminated from the final sample: in Spain n = 62, in Chile n = 93, and in Colombia n = 61.

Statistical Analysis

Correlation analyses, repeated-measures designs and between-group unifactorial, factorial, and multivariate (MANOVA) analysis of variance designs were applied. After the MANOVA, univariate analysis of variance designs are performed for variables that showed statistically significant multivariate global differences. The results of the statistically significant univariate tests are later studied by analyzing all the possible comparisons of pairs of means, using Bonferroni’s correction for the p-values of probability of the contrasts between the pairs of means. This type of correction was not carried out in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020). Effect size measures are noted next to the p-values for probability (Badenes-Ribera et al., Reference Badenes-Ribera, Frias-Navarro, Monterde-i-Bort and Pascual-Soler2015; Monterde-i-Bort et al., Reference Monterde-i-Bort, Pascual-Llobell and Frias-Navarro2006). The effect sizes are interpreted according to the values proposed by Cohen (Reference Cohen1988): Small effect size: d = 0.2, η2 = .01, r = .10; medium effect size: d = 0.5, η2 = .06, r = .30; and large effect size: d = 0.8, η2 = .14, r = .50. Cohen’s d was estimated with the JASP program based on the difference in means between the groups and the standard error of this difference. When analyzing the difference between two mean scores, Cohen’s d is used, and when it is an ANOVA with more than two groups, eta squared is used. The statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS v.26, JASP v.0.12.2 and GPower v.3.1.9.7 programs.

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF (Center for Open Science)Footnote 1

Results

Objective 1. Check the level of persuasion of the four messages (independent variable manipulated and randomly assigned) on the dependent variables of washing hands, participating in public gatherings, avoiding all social contact, and sharing the message received on Facebook. The effect of the messages is measured in two situations: (a) In terms of the behavioral intentions of the participants themselves; and (b) assessing the participants’ beliefs about the behavior of others. Thus, eight measured variables are used. In addition, our study also includes the factor of the participants’ country of residence: Spain, Colombia, and Chile, to find out whether the country of residence moderates the effect of the messages on the measured variables. It should be kept in mind that after collecting the data, it was verified that the three countries were in different situations with regard to the beginning of the quarantine: In Spain, it began on March 14th, in Colombia on March 24th (in both countries the lockdown was still in effect when the survey ended), and in Chile the government has not yet implemented a quarantine for the whole territory, although there is social alarm, and in certain areas there is an order to stay at home (as of April 25th). Therefore, we thought it was necessary to check whether there was an interaction effect, where the effect of the messages could be moderated by the participants’ country, given that the levels of national emergency are different. The design methodology is experimental because the message type variable is manipulated and randomly assigned to each participant. The sample sizes of the four message conditions are balanced: deontological n = 897, utilitarian n = 921, virtue-based n = 926, and the control group n = 918. By country of residence, the sample sizes are: Spain n = 1,122, Colombia n = 1,433, and Chile n = 1,107.

To analyze the effect of the messages’ interaction with the country of residence on the eight measured variables, a between-groups 4 x 3 multivariate factorial analysis of variance (MANOVA) was applied, with the factors being the messages (deontological, utilitarian, virtue-based, and control) and the countries (Spain, Colombia, and Chile).

The results of the MANOVA show that there is no interaction effect between the messages and the country, Λ (Wilks’ Lambda) = 0.987, F(48, 17,929.15)= 1, p = .474, η2 = .002. The principal effects of the message received, Λ, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.967, F(24, 10,566.41) = 5.20, p < .001, η2 = .011; and the country, Λ, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.901, F(16, 7286) = 19.309, p < .001, η2 = .051, are statistically significant.

Effects of the Type of Message Received

In the case of the type of message and the behavioral intentions (opinions referring to the self), the effect is statistically significant on the four measured variables. That is, there are overall differences between message types in terms of opinions about the probability of hand-washing, F(3, 3,650) = 20.63, p < .001, η2 = .017, participating in public gatherings, F(3, 3,650) = 8.10, p < .001, η2 = .007, staying at home and avoiding social contact, F(3, 3,650) = 9.37, p < .001, η2 = .008), and sharing the message, F(3, 3,650) = 20.19, p < .001, η2 = .016.

The results of participants’ beliefs about the actions of others (opinions about others) indicate that statistically significant differences are found in the variables of the probability of hand-washing, F(3, 3,650) = 13.97, p < .001, η2 = .011; staying at home, F(3, 2,934) = 8.37, p < .001, η2 = .007; and sharing the message, F(3, 3,650) = 5.21, p = .001, η2 = .004. On the variable of the probability that others will participate in public gatherings, no statistically significant effects are detected, F(3, 3,650) = 0.39, p = .759, η2 < .001.

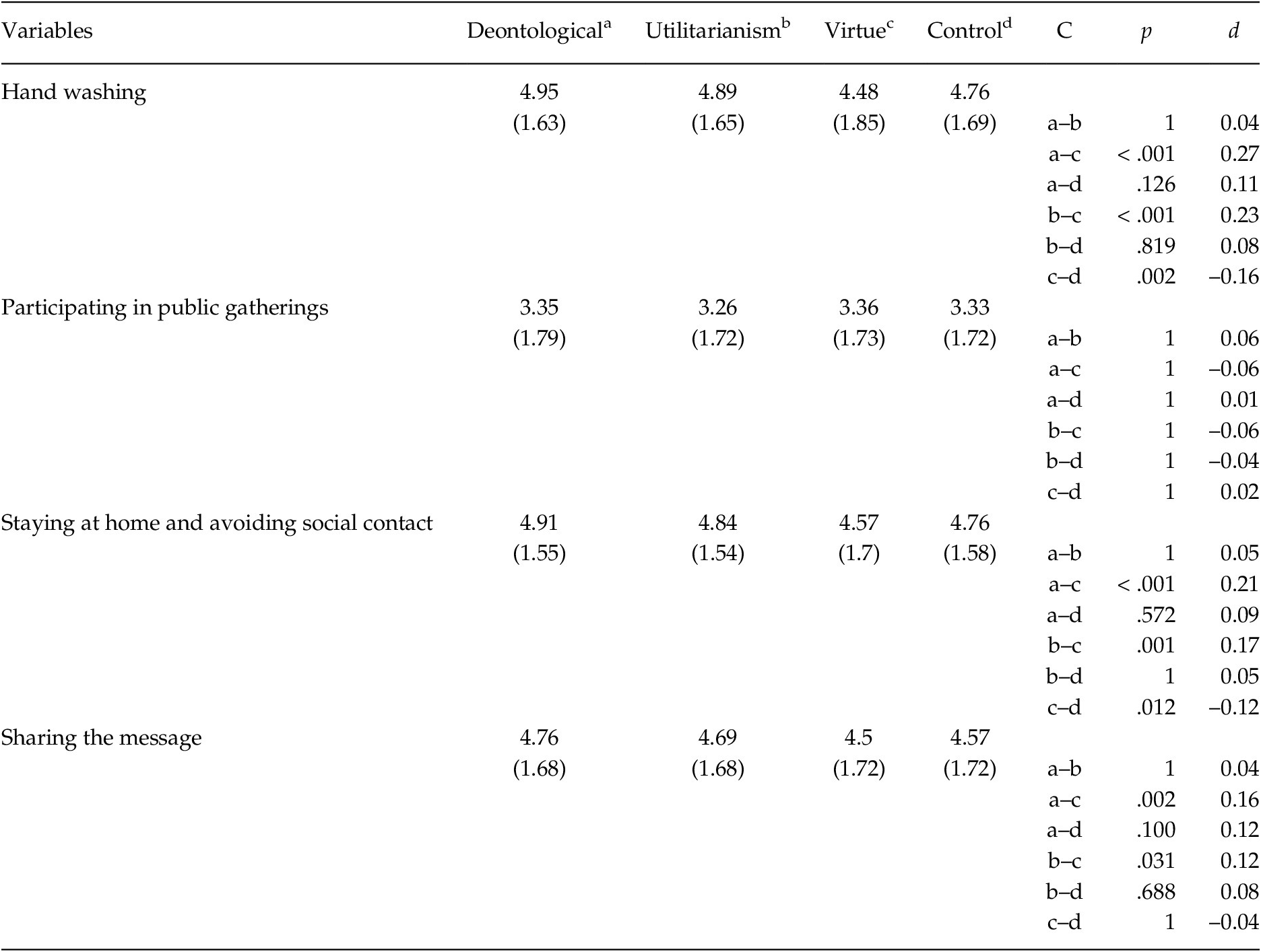

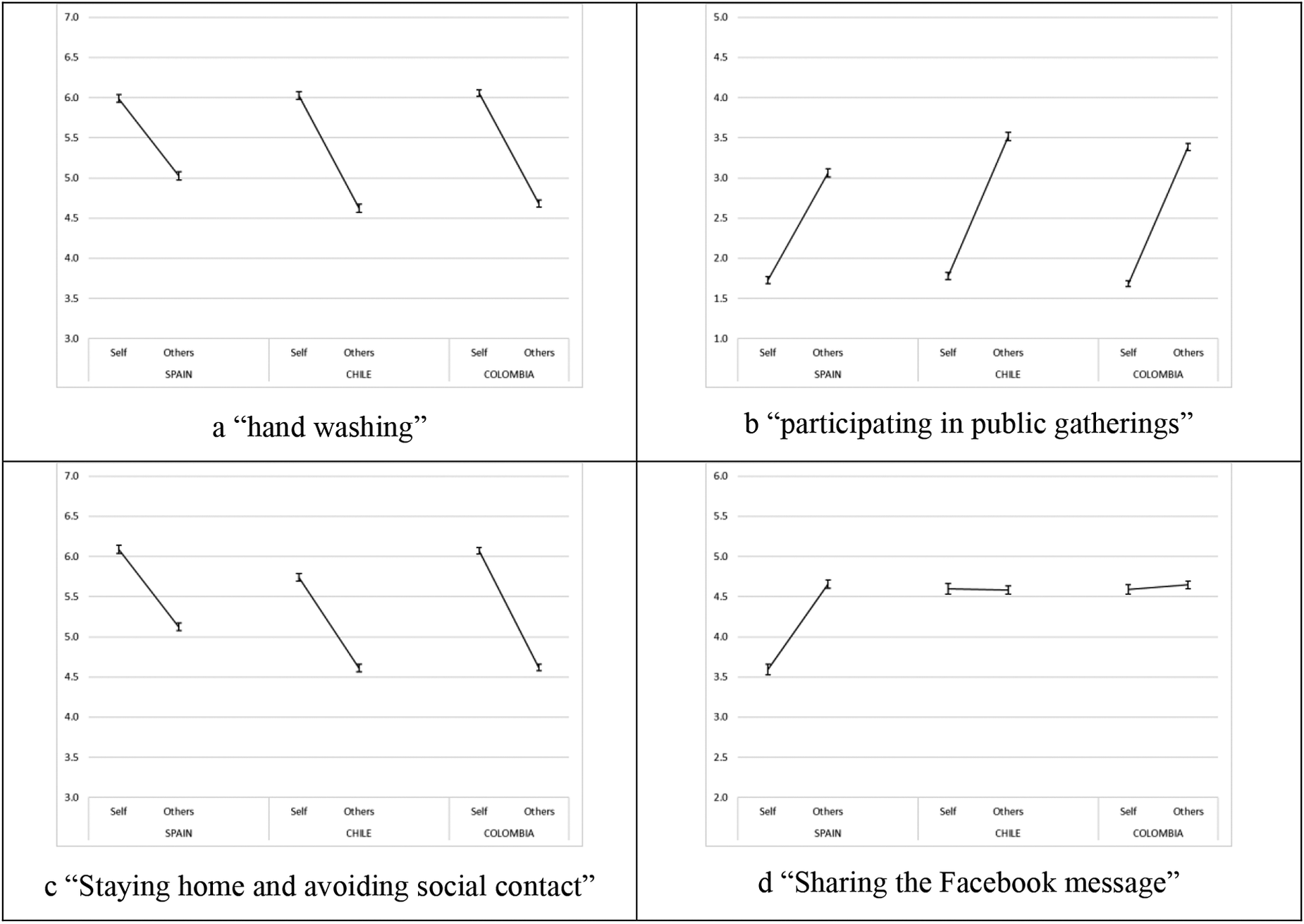

The results for the comparisons of pairs of means for the types of messages on each of the measured variables, referring to the two blocks of analysis, behavioral intentions, and beliefs about others’ behaviors, can be found in Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 1.

Table 2. Type of Messages. Behavioral Intentions (Opinions referring to the Self). Means, Standard Deviations, Comparisons, and Effect Size

Note. aComparisons = C. bBonferroni correction is used.

Table 3. Type of Message. Behavioral Beliefs (Opinions about Others). Means, Standard Deviations, Comparisons, and Effect Size

Note. aComparisons = C. bBonferroni correction is used.

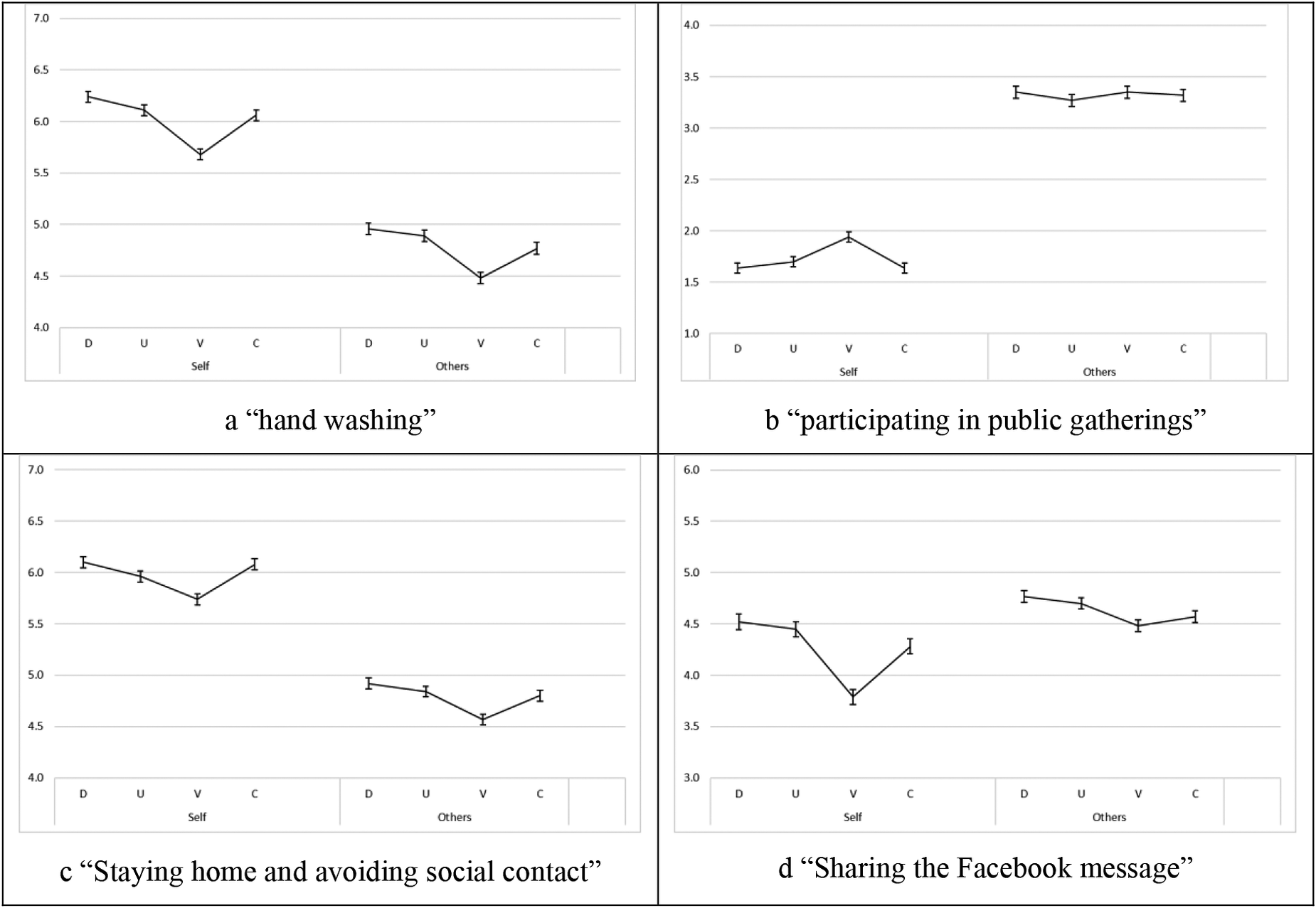

Figure 1. Type of Message. Behavioral Intentions (referring to the Self) and Behavioral Beliefs (referring to others).

Note. Variables: a = hand washing; b = participating in public gatherings; c = staying at home and avoiding social contact; d = sharing the Facebook message.

D = deontological; U = utilitarianism; V= virtue; C = control. Error bars show standard errors.

Comparisons of Pairs of Means: Behavioral Intentions

Analysis of comparisons of pairs of means among the four Facebook messages indicates a pattern of stable outcomes when the four public health variables and the participants’ behavioral intentions are analyzed. Thus, it is observed that participants who receive the message that refers to the ethical virtue of being a good person and staying at home are less likely to wash their hands, stay at home, avoid social contact, and share that message on Facebook, and they are more likely to participate in public gatherings. In addition, all the differences between the virtue-based message and the mean scores on the deontological message, the utilitarian message, and the control message are statistically significant. The rest of the between-group comparisons are not statistically significant (Table 2).

Therefore, a message based on the argument of the ethical virtue of the citizens is not recommended because the probability of carrying out behaviors compatible with hand washing, staying at home, and sharing the message received is lower, whereas the probability of participating in public gatherings is higher, compared to the other two moral messages (deontological and utilitarian) and even the control group. Figure 1 shows the estimated mean scores on the two dimensions of behavioral intentions and beliefs about the behavior of others.

Comparisons of Pairs of Means: Beliefs about Others’ Behavior

The results show that participants who read the message with content referring to ethical virtue obtained a lower score on the variables of probability of others’ washing their hands and the probability of others’ staying at home and avoiding social contact, in comparison with those who received the deontological, utilitarian, or control message. Regarding the probability that others will share the message, the findings reveal that the group that received the ethical virtue-based message scored lower than the groups with deontological and utilitarian messages. In the rest of the comparisons, the differences were not statistically significant (see Table 3 and Figure 1).

Effects of the Country of Residence

The analysis of the principal effect of the country of residence variable indicates that when assessing one’s own behavior (opinions referring to the self), statistically significant differences are detected in the variables of the probability of staying at home and avoiding social contact, F(2, 3,650) = 16.81, p < .001, η2 = .009, and sharing the message, F(2, 3,650) = 80.85, p < .001, η2 = .042. No statistically significant differences are obtained in the variables of the probability of hand washing, F(2, 3,650) = 0.58, p = .560, η2 < .001, and participating in public gatherings, F(2, 3,650) = 1.27, p = .281, η2 = .001.

The results for participants’ beliefs about the actions of others (opinions about others) indicate that statistically significant differences are found in the variables of the probability of hand washing, F(2, 3,650) = 18.97, p < .001, η2 = .010, participating in public gatherings, F(2, 3,650) = 20.43, p < .001, η2 = .011, and staying at home and avoiding social contact, F(2, 3,650) = 36.20, p < .001, η2 = .024. The variable of the probability of others sharing the message is not statistically significant, F(2, 3,650) = 0.664, p = .515, η2 < .001.

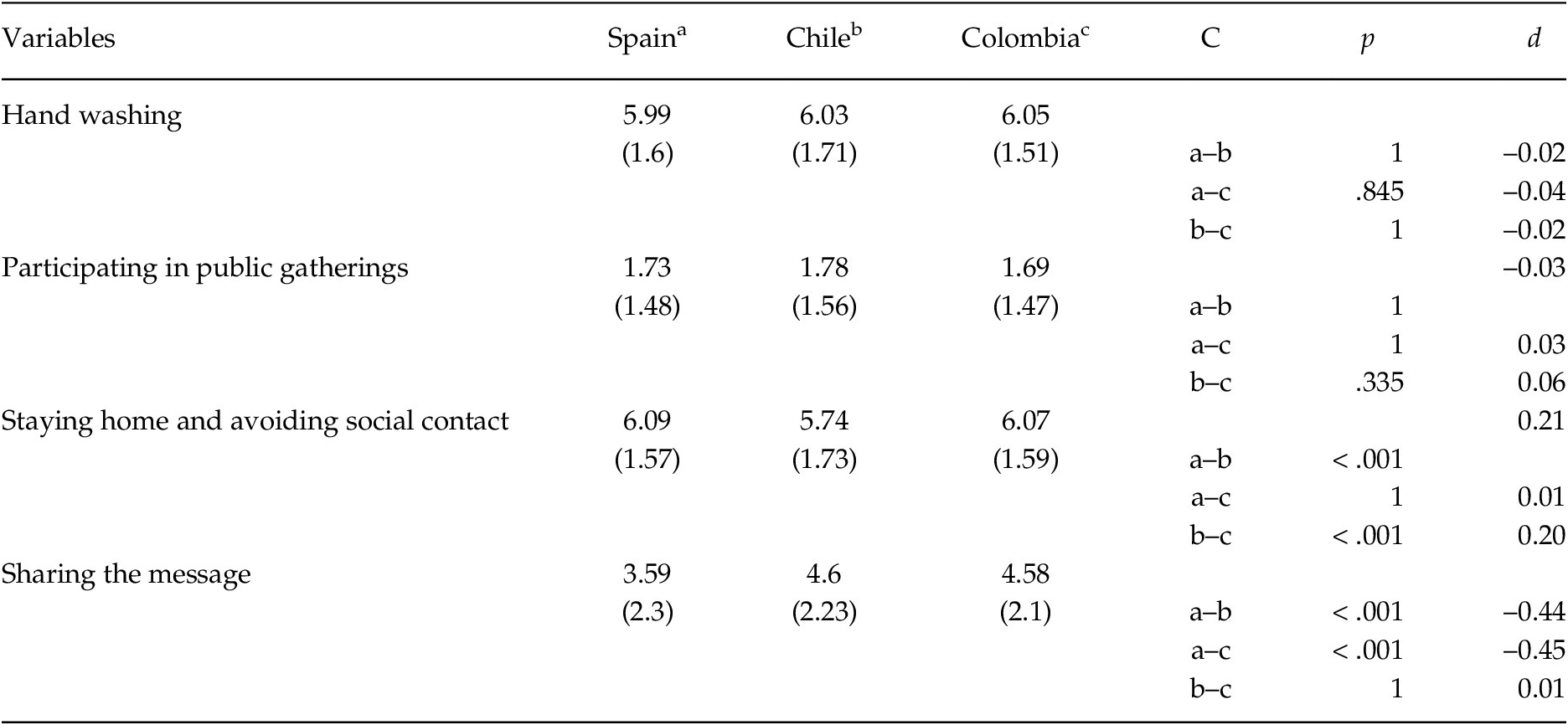

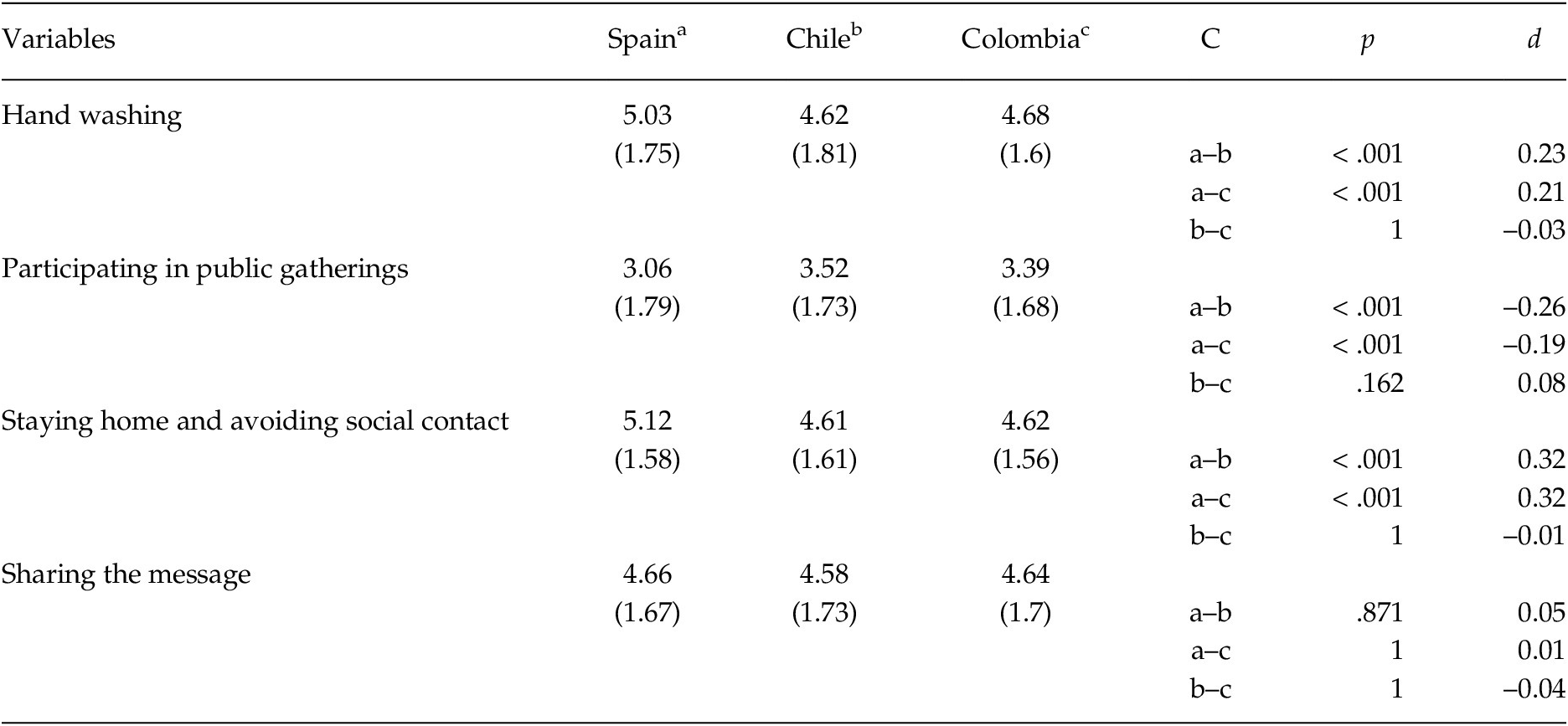

The results of the comparisons of pairs of means of the country variable in each of the measured variables, regarding the two blocks of analysis of behavioral intentions and beliefs about others’ behaviors, are shown in Tables 4 and 5 and Figure 2.

Table 4. Country of Residence. Behavioral Intentions (Opinions referring to the Self). Means, Standard Deviations, Comparisons, and Effect Size

Note. aComparisons = C. bBonferroni correction is used.

Table 5. Country of Residence. Behavioral Intentions (Opinions about others). Means, Standard Deviations, comparisons, and Effect Size

Note. aComparisons = C. bBonferroni correction is used.

Figure 2. Country of residence. Behavioral intentions (referring to the self) and behavioral beliefs (referring to others).

Note. Variables: a = hand washing; b = participating in public gatherings; c = staying at home and avoiding social contact; and d = sharing the Facebook message.

D = deontological; U = utilitarianism; V = virtue; C = control. Error bars show standard error.

Comparisons of Pairs of Means: Behavioral Intentions

The analysis of the comparisons of pairs of means of the three countries of residence shows that in the case of the probability of staying at home and avoiding social contact, the scores of the participants from Chile are lower than those of the participants from Spain and Colombia (Table 4). The difference between Colombia and Spain is not statistically significant. In the case of sharing the Facebook message, residents in Spain are less likely to share it than residents in Chile and Colombia, and the differences are statistically significant. The difference between Chile and Colombia is not statistically significant.

Figure 2 shows the estimated mean scores on the variables of behavioral intentions (opinions about self) and beliefs about others’ behavior (opinions about others) and the countries of residence.

Comparisons of Pairs of Means: Beliefs about Others’ Behavior

When analyzing the variable of beliefs about others’ behavior, the results of the analyses of the comparisons of pairs of means for the three countries of residence indicate that the participants from Spain obtain a higher mean score than Chile and Colombia on the variables of the probability of hand washing and staying at home and avoiding social contact, with statistically significant differences. In addition, participants who reside in Spain obtain a lower mean than Chile and Colombia on the variable of the probability that others will participate in public gatherings, with statistically significant differences. Therefore, in general, it can be observed that the Spanish participants state that they follow the recommendations of the government and health professionals to a greater extent, and they also believe to a greater extent that others are also acting in accordance with these guidelines (Table 5). There are no statistically significant differences between the groups’ means on the variable of sharing the Facebook message or any differences between the participants from Chile and Colombia on any of the variables.

Objective 2. Analyze participants’ degree of concern about the problem of COVID–19. The degree of concern about the coronavirus is analyzed taking into account the following variables: Country, gender by age, having children, living in a family or alone, perceived social class, educational level, and the perception of global threat and personal threat.

The degree of concern about the coronavirus problem was measured with a single item ranging from 1 to 10. The results indicate that participants in all three countries have a high level of concern, with the mean being 8 and the mode 10 (SD = 2.01, median = 8, minimum = 1, maximum = 10).

Because concern about the coronavirus pandemic is high in all three countries, and the highest percentage of agreement is obtained for the highest score on the response scale, this high degree of concern differs depending on where the participants live (unifactorial between-group design, F(2, 3,659) = 22.85, p < .001, η2 = .012. Specifically, participants from Chile have the highest mean score (n = 1,107, Mean = 8.30, SD = 1.95), and they differ significantly from Spain (n = 1,122, Mean = 7.99, SD = 1.80, p < .001, d = 0.17) and Colombia (n = 1,433, Mean = 7.76, SD = 2.17, p < .001, d = 0.26). The difference between Spain and Colombia is also statistically significant (p = .012, d = 0.11). In all cases, the magnitude of the differences is small.

With regard to the age variable, the results indicate that there is a positive and statistically significant relationship with the degree of concern, r = .128, p < .001, 95% CI [.10, .16], with a small effect size.

The results of the Sex x Age group factorial design (the age variable was divided into five groups) indicate that the interaction between sex and age on the degree of concern about the coronavirus is not statistically significant, F(4, 3639) = 1.97, p = .097, η2 = .002. Regarding the main effects, on the variable degree of concern about COVID–19, the difference between the mean scores of women (n = 2,491, Mean = 8.17, SD = 1.91) and men (n = 1,158, Mean = 7.66, SD = 2.15) is statistically significant, F(1, 3,639) = 53.36, p < .001, d = 0.26, with women obtaining the highest mean scores, with a small effect size. Differences are also detected in the degree of concern related to the age group variable, F(4, 3,639) = 20.75, p < .001, η2 = 022. Comparisons of the pairs of means indicate that differences are found between participants younger than 34 years old and those who are 34 years old or more, with Cohen’s d effect sizes ranging from a very small effect of 0.06 to a medium effect of 0.47 (between the 18–21 year-old group and the 50 or older group). It can be observed that the means of the three youngest groups do not differ from each other in a statistically significant way; nor do the means of the two oldest groups.

Regarding the degree of concern about the coronavirus pandemic and the variable of having children or not, it can be observed that participants who have children (n = 1,235, mean = 8.42, SD = 1.86) are more concerned than those who do not (n = 2,035, mean = 7.70, SD = 2.05), and the difference is statistically significant –unifactorial between-group design, F(1, 3,268) = 101.01, p < .001, d = 0.36–, with the magnitude of the difference being small-medium.

The difference between the scores for those living alone (n = 311, mean = 7.84, SD = 2.02) or living with someone else (n = 2,959, mean = 7.99, SD = 2.01) is not statistically significant –unifactorial between-group design, F(1, 3,268) = 1.64, p = .200, d = 0.08.

Likewise, statistically significant differences were not detected between the groups on the variable of participants’ perceived social class and their degree of concern about the coronavirus –unifactorial between-group design, F(2, 3,267) = 1.00, p = .367, η2 < .001– or between the low/medium-low perceived social class (n = 1,179, mean = 7.97, SD = 2.12) and the medium social class group (n = 1712, mean = 8.01, SD = 1.98, p = .897, d = 0.02) and the upper/medium group (n = 379, mean = 7.84, SD = 1.82, p = .530, d = 0.06). Moreover, the means of the medium-class groups do not differ significantly from those of the medium-high/high class group (p = .333, d = 0.08).

Regarding the participants’ level of education, although the ANOVA results indicate that there are some statistically significant differences, F(2, 3,272) = 3.44, p = .032, η2 = .002, when comparisons are made by pairs of means and Bonferroni correction is applied, which is a more severe test, there are no statistically significant differences. The mean scores for the basic/intermediate–1 studies group (n = 274, mean = 8.16, SD = 1.98) versus the intermediate–2 studies group (n = 1,080, mean = 7.86, SD = 2.10) do not differ significantly (p = .080, d = 0.15); nor do they differ from the higher education group (n = 1921, mean = 8.02, SD = 1.96, p = .834, d = 0.07). The difference between the means of the intermediate–2 group and the higher education group is not statistically significant either (p = .107 d = –0.08).

A repeated-measures design is used to compare participants’ perception of whether the coronavirus problem is a threat to the world population (n = 3,399, mean = 6.28, SD = 1.080) or feels like a personal threat (mean = 5.13, SD = 1.46), and the difference between the mean scores is statistically significant, F(1, 3,398) = 2,677.62, p < .001, η2 = .441. The participants’ degree of concern is mainly about the threat the virus poses to the world population (a very high level because the mean is 6.28 out of 7), and they personally perceive a lower level of threat (score is 5.13).

An analysis of the correlations between the variables of age and the perception of the coronavirus threat to the global population, r = .082, p < .001, 95% CI [.05, .12], and the perception of personal threat, r = .131, p < .001, 95% CI [.10, .16], indicates that the relationships are positive and statistically significant, with a small effect size. That is, the older the subject, the greater the concern about the threat posed by the coronavirus problem, both globally and personally. The relationship between concern about the global population and personal threat is very strong and positive, r = .518, p < .001, 95% CI [.49, .54], with a large effect size.

Objective 3. Analyze opinions about the most effective moral message in reducing the spread of COVID–19, with regard to the behavior of staying home and the country. This objective allows us to control whether the message produces an effect.

Before viewing the Facebook message in the experimental task, which is the primary objective of our research, participants had to assess which of the three moral messages presented in the experimental task would be the most effective in keeping citizens confined at home. The order of presentation of the alternative messages to the participants was random. It is strongly observed in all three countries that the message referring to the virtue of the citizen (being a good person as a virtue or trait of good citizenship) is the one they think would be less effective in keeping people at home. In the three countries, the message chosen the most was deontological (54.53%), followed by utilitarianism (42.63%) and ethical virtue (2.84%).

In addition, our research design included this question before the experimental manipulation (in contrast to the study by Everett et al., Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), in order to test whether the Facebook messages have any effect. It should be noted that participants’ attentiveness to the message was controlled because they had to identify what the sender’s profession was. Participants who did not identify it correctly were eliminated from the sample. The results indicate that there was an effect of the Facebook message, specifically the ethical virtue message, along the same lines as the previous analysis of the effects of the message received, regardless of their prior opinions.

After identifying the two groups of participants who previously chose the utilitarian or deontological moral message as the most effective, these two groups were analyzed separately. For example, the group that selected the utilitarian message as the most effective response option was divided into three groups: Those who subsequently received the utilitarian moral message (U-U, match), those who received the ethical virtue message (U-V), and those who received the deontological moral message (U-D). If the Facebook message had any effect, statistically significant differences would be detected between these three groups, even though all these participants had chosen the utilitarian message as the most effective. The same analysis was performed with the group that chose the deontological moral message as the most effective.

In the case of the group of participants who chose the utilitarian message as the most effective message to convince citizens to stay at home, it is observed that the Facebook message had an effect, given that the group that received the Facebook message of virtue believe that they are less likely to wash their hands, stay at home, and share the message, whereas they are more likely to participate in social gatherings than the groups that received the utilitarian message and the deontological message. With regard to the opinions about the behavior of others, the results show that there was an effect of the Facebook message on the likelihood of another person washing their hands and staying at home because participants who received the virtue message thought these probabilities would be lower, compared to participants who received the utilitarian and deontological messages. In the case of the variables of the likelihood of meeting in public places and sharing the message, no statistically significant differences were detected.

Regarding the group that chose the deontological message as the most effective message to convince citizens to stay at home, it is observed that the Facebook message had an effect, given that the group that received the Facebook message of virtue believed that they would be less likely to wash their hands and share the message than the groups that received the utilitarian and deontological messages. Furthermore, with regard to the likelihood of staying at home, the group of subjects who received the virtue message differed from the group that received the deontological message. With regard to the likelihood of meeting socially, no statistically significant differences were detected between the participants in the three groups. Regarding their opinions about the behavior of others, the results are inconclusive because the effect of the Facebook message was not observed, given that the probabilities attributed to the variables measured did not change in a statistically significant way depending on whether one message or the other was received. Subsequently, the effect of the Facebook messages was analyzed with groups of messages formed at random.

In addition, the analysis also focused on the matches between the message chosen as having the most persuasive power and the subsequent Facebook message received with the same content (match), as well as the analysis of non-matches (no match between the content of the message chosen as having the most persuasive power and the content of the message received). The analyses were carried out independently for Facebook messages with deontological and utilitarian content. As mentioned above, the small number of people who selected the virtual message as the most persuasive made it impossible to analyze matches in the content. A between-groups design was used with two conditions: Match/non-match. In the case of the message with deontological content, results show that only the variables of the probability of always washing your hands (p = .005) and sharing this message (p = .003) show statistically significant differences, with a higher mean score when there is a match between the message rated as the most effective and the Facebook message received with the same content. In the case of the utilitarian message, the group with the content match obtained a higher mean score on the variables of the probability of always washing your hands (p = .034), the probability that you will share this message (p < .001), the probability that someone else will always wash their hands (p = .007), and the probability that someone else will stay at home and avoid social contact (p = .007). Therefore, a greater persuasion effect is observed when the contents match, but not consistently and with a different profile depending on whether the message chosen as having more persuasive power is the deontological or utilitarian message.

Discussion

In these first months of the study of COVID–19 when its genetics and biology are not yet completely defined, partly because of uncertainty due to incomplete or inaccurate data, replication studies verifying the robustness of the results are always important. Our research aimed to replicate the messages used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) to analyze the effect of moral messages on public health behavioral intentions during the COVID–19 pandemic. Our study uses the four types of messages used in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), as well as four of its dependent variables; only the photo of the Facebook message has been changed. In our study, the leadership figure who sent the message on Facebook was not manipulated because Everett’s study obtained an irrelevant effect. For all the messages, the sender is a university professor. In their conclusions, these authors defend the need to carry out replication studies and, thus, provide validity evidence to compare with their findings. The evidence from the two studies provides information that could be important in assessing what type of content is most effective in persuading citizens to adopt the behaviors recommended in messages designed to intervene in public health during a pandemic or health emergency. This information is accompanied by a description of the emotional and social context where the participants live because, among other variables, the citizens’ perception of the social situation of the pandemic and their concern, responsibility, and behavior have been analyzed.

First, starting with the primary objective of our study, our results consistently show that participants who receive the moral message referring to ethical virtue score lower on their behavioral intentions (opinions about their own behavior) related to the public health behaviors of washing their hands, staying at home and avoiding social contact, and sharing the Facebook message. In addition, this ethical virtue-based message scores higher on the likelihood of participating in public gatherings during the confinement period, and its scores differ from those of the moral messages of utilitarianism and deontology and from the comparison group message with no moral content, with small effect sizes, as predicted. Therefore, the first recommendation is to avoid using messages with content that refers to ethical virtue or to what a good person should do during a pandemic crisis like COVID–19 because these messages obtain lower scores on the probability that citizens will adopt the public health behaviors recommended in this type of situation. The work by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) highlights the positive effect of the deontological message compared to the virtue-based message in the case of the probability of engaging in hand washing. This message also has a positive effect on the probability of sending the message received, compared to the virtue-based message and the control group message. It should be noted that some of the effects detected in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) failed to pass the classical statistical significance level, and comparisons of pairs of means were not carried out by adjusting the alpha value (Anvari, Reference Anvari2020). The authors of the original study did not plan to apply the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Therefore, their results must be interpreted with caution, which makes it difficult to compare our findings.

Second, our findings indicate that in the case of beliefs about the effect of the messages and the behavior of others (opinions about others’ behavior), the differences between messages are minor and depend on the public health variable being analyzed. In the case of the probability of others washing their hands and staying at home and avoiding social contact, the pattern is the same as for behavioral intentions; that is, the effect of the virtue-based message scores lower than the messages of deontological morality, moral utilitarianism, and the control group. Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) also detect a greater effect on the beliefs of those who receive the deontological message than the effect of the virtue-based message on the behavior of hand washing. With regard to sharing the Facebook message, the group that receives the virtue-based message scores lower than the groups that receive deontological and utilitarian messages. On the variable of the probability of staying at home and avoiding social contact, there are no statistically significant differences.

Third, in the three countries that participated in the research, the results show that in terms of behavioral intentions, Chilean citizens say that they stay home less than those in Spain and Colombia. These data are consistent with the fact that in Chile the government has not decreed a compulsory lockdown. In the case of sharing messages about the coronavirus problem and public health behaviors, Spanish citizens would share them the least, compared to Chile and Colombia. With regard to beliefs about others’ behavior, participants from Spain have a greater belief, compared to those from Chile and Colombia, that others will wash their hands and stay at home to avoid social contact and avoid participating in public gatherings.

Fourth, and contextualizing the participants’ emotional state of fear, it can be observed that, in general, all the participants in our research are very concerned about the COVID–19 problem. The variables of sex, age, and having children moderate this result. Women have a higher level of concern than men. From approximately 34 years of age and up, the level of concern increases, and it is greater if they have children. No systematic differences were detected for the variables of living alone or in company, perceived social class, or educational level. With regard to the country, participants in Chile feel a greater degree of concern, followed by Spain and Colombia. Chile is the only country whose population has not received a lockdown order. Given that information about the pandemic is available globally, Chileans may feel somewhat less protected because their country is not taking social isolation measures to control the spread of COVID–19. One interesting result to analyze is that Chile had the highest means on concern about COVID, but the means were lower on taking measures to fight the disease. The high concern could be determined by the messages communicated daily by the government and the media related to the seriousness of the virus (Tariq, Reference Tariq, Undurraga, Castillo Laborde, Vogt-Geisse, Luo, Rothenberg and Chowell2021). The low concern of the population about adopting self-care measures could be explained by the fact that, at the time of the study, restrictive health regulations had only been decreed in three of its sixteen regions, and they were not strictly controlled (Ochoa-Rosales et al., Reference Ochoa-Rosales, González-Jaramillo, Vera-Calzaretta and Franco2020). In addition, physical distancing and the use of masks in public spaces were recommendations rather than obligations.

Fifth, participants express great concern about whether this health pandemic is a global or personal threat, with the global threat being of greater concern. Again, concern about the global pandemic and about their personal situation increases with age.

And sixth, we recorded participants’ views about the moral message that would be most effective in reducing the spread of COVID–19. However, unlike in the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), in our design the question was asked before the experimental manipulation of the four messages. Participants from all three countries felt that the virtue-based message would be the least effective in persuading citizens to adopt hygiene and confinement behaviors. In addition, the participants’ responses in all three countries rate the deontological message as the most effective, followed closely by the utilitarian message, and at a great distance, the virtue-based message. Perhaps this very homogeneous distribution of the data, where the virtue-based message is selected very little, can explain why the control group does not differ in any case from the deontological and utilitarian arguments; that is, the participants with the control message activate their preference for the deontological or utilitarian message. In the study by Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020), the virtue-based message is also hardly selected, but the order of the other two moral messages is inverted. In their sample with US citizens, the message based on ideas about the consequences of the behavior or utilitarianism was chosen more. Although it can be argued that much of Western society is governed by individualistic norms, it is widely recognized that Hispanic-American culture is strongly tied to socialization behavior, with an emphasis on community responsibility (Oyserman et al., Reference Oyserman, Coon and Kemmelmeier2002; Raeff et al., Reference Raeff, Greenfield and Quiroz2000). In sum, the results indicate that participants’ personal opinions about the effectiveness of the messages are highly consistent with the findings about the effects of moral messages because the virtue-based message was the least effective in increasing the likelihood of carrying out public health behaviors.

During the planning phase of our study, we established that the expected effect sizes on the measured variables would be small, and therefore it was necessary to collect a very large sample of participants so that the analyses would have sufficient statistical sensitivity. In fact, the results of Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) warned of this situation, and our findings confirmed it. It should be kept in mind that in this pandemic and national emergency scenario, identifying a small effect size may have considerable importance in terms of practical significance because the magnitude of an effect does not determine the value the effect has (Pek & Flora, Reference Pek and Flora2018; Rosenthal, Reference Rosenthal, Cooper and Hedges1994; Rosnow & Rosenthal, Reference Rosnow and Rosenthal1989). Therefore, the magnitude or impact of an effect should be assessed according to its practical significance and research context (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin1999). Identifying the type of content that should be included and emphasized in messages from governments and professionals or the media to persuade the population to stay at home, avoid social contact, and change all their life routines, probably worsening their economic and psychological health, can be quite important because it is a question of saving thousands of lives by reducing the incidence of the disease and its consequences. As Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) point out, “in the context of a public health crisis, even changing the behavior of a small percentage of individuals can save lives, and small changes in framing of messages are a cheaply-implemented tool that could be readily implemented on communications platforms”. In addition, the effectiveness of the messages’ content can be generalized when the confinement ends and governments have to re-send messages to citizens to adopt specific behaviors so that the return to daily life is done properly and does not cause further problems or stress in the population. In the study by Awad et al. (Reference Awad, Dsouza, Shariff, Rahwan and Bonnefon2020) on moral decisions, conducted with 42 countries and a sample of 70,000 participants, small effect sizes of 0.10 are observed when dealing with moral dilemmas in situations of sacrificing one person to save many lives. From other areas, classic studies also obtain small effect sizes (Lipsey & Wilson, Reference Lipsey and Wilson1993). The meta-analytic review by Richard et al. (Reference Richard, Bond and Stokes-Zoota2003) on effect sizes in social psychology research reveal that a third of the effects published are small (mean r = .10), as in minimal increases in the value of a commodity (mean r = .12), the higher a person’s credibility, the more persuasive that person will be (mean r = .10), information about a speaker’s credibility has less impact if it is delayed (r = .13), or people attribute their failures to bad luck (mean r = .10). As Funder and Ozer (Reference Funder and Ozer2019) point out, “smaller effect sizes are not merely worth taking seriously. They are also more believable”, and they add that “in our view, enough experience has already accumulated to make one suspect that small effect sizes from large N studies are the most likely to reflect the true state of nature”. Furthermore, it is worth reflecting on the fact that, although the size of the effect is small quantitatively, if the effect appears systematically in different situations and environments, it is likely that some type of valuable information is being transmitted.

Ultimately, behavioral science and non-pharmacological treatments or public health measures are also important and effective measures for controlling the pandemic because they reduce contact in the population and, therefore, the likelihood of transmission of the virus (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Laydon, Nedjati-Gilani, Imai, Ainslie, Baguelin, Bhatia, Boonyasiri, Cucunubá, Cuomo-Dannenburg, Dighe, Dorigatti, Fu, Gaythorpe, Green, Hamlet, Hinsley, Okell, van Elsland and Ghani2020; Lunn et al., Reference Lunn, Belton, Lavin, McGowan, Timmons and Robertson2020). Isolation measures for mitigation or suppression purposes are especially relevant to contain the pandemic when no effective vaccine or drug has been tested in clinical trials (González-Jaramillo et al., Reference González-Jaramillo, González-Jaramillo, Gómez-Restrepo, Palacio-Acosta, Gómez-López and Franco2020). As Garfin et al. (Reference Garfin, Silver and Holman2020) point out, “health care providers can provide critical information and make concrete suggestions while seeking to temper hysteria that may thwart overall public health efforts to effectively combat the COVID–2019 outbreak” (p. 357).

Behavioral science can also help to control the problem of COVID–19, and our study is carried out from this social and psychological perspective. These non-pharmacological measures are implemented to contain the spread of the virus and gain time to activate an effective healthcare plan, prepare an antiviral drug, and produce a vaccine to stop COVID–19. Furthermore, the end of confinement also requires public institutions and professionals to communicate new messages that can activate the participation of citizens who will have to follow their instructions in order to avoid new outbreaks of the disease and ease the transition to daily life. The knowledge acquired now about citizens’ attitudes and behaviors will be essential in developing more effective action guidelines if they are needed in other future pandemic scenarios.

One of the main limitations of our study is a possible bias in selecting the sample of participants. This is a voluntary, self-selected sample that may consist of people interested in the subject of COVID–19 with greater access to the Internet, and so it probably does not represent the entire population in terms of sex, age, and the geographical distribution of the participants by country. However, this type of social research is difficult to carry out using probabilistic sampling. In addition, as Everett et al. (Reference Everett, Colombatto, Chituc, Brady and Crockett2020) state, strong heterogeneity is expected among the measured variables, and, moreover, various socio-demographic variables can moderate the effect of the messages. Their analysis would require samples that identify each condition of the variables with a sufficient number of observations, and interaction effects might occur that are quite difficult to analyze and interpret.

For all these reasons, we think it is necessary to carry out direct and conceptual replications of the constructs analyzed in order to provide more evidence with which to build solid and generalizable knowledge. Despite the limitations, we think our results contribute valuable information that can help to generate and plan future research and provide evidence about the most effective type of moral content in messages designed to activate public health behaviors during a global crisis like the COVID–19 pandemic. Healthcare decisions need action guidelines based on the best evidence currently available.

Our study provides results that can help to more effectively craft public health messages delivered through social media. There are many variables involved in modifying behavior, and our research provides evidence about the type of moral message and behavioral intentions. Institutional messages aimed at promoting public health behaviors are necessary in a pandemic situation. Their objective is to communicate the actions that should be taken by the population, and they must be communicated effectively. Our recommendation is to use deontological and utilitarian or non-moral content, but without referring to the ethical virtue of the individual. Therefore, social cooperation stands out as being fundamental for the survival of humanity. In addition, having this information can help to better manage messages in different stages of COVID–19 (e.g., “flattening the curve”), as well as in future public health crises.