Micronutrient requirements

The term ‘requirement’ has several meanings in nutritional science and these are often used interchangeably, especially when discussing micronutrients. The biological requirement refers to the amount of a nutrient required by the body for essential structural and metabolic functions. The dietary requirement refers to the amount of the nutrient in a typical diet that supplies sufficient of the nutrient to meet the biological requirement, and, when applied to a population, is the amount of the nutrient in a typical diet that supplies sufficient of the nutrient to meet the needs of the majority of the population for which the guidelines are set. In the UK this latter definition is referred to as the reference nutrient intake (RNI), in the USA/Canada as the RDA and in the EU as the population reference intake. Where there is insufficient evidence to determine a population dietary requirement for any nutrient, a value referred to as a safe intake in the UK or as an adequate intake in USA/Canada and EU is estimated. These values are known generically as dietary reference values (DRV) in the UK and EU and as dietary reference intakes in the USA/Canada. Most other national authorities developing dietary requirements for their populations use similar terminology, but often with subtle differences. For clarity in this paper, the terms RNI and DRV will be used to denote these various population terms except when referring to a specific set of national reference values, and the discussion will be limited to these three sets of DRV guidelines.

Development of dietary reference values

The definition and methods used to derive DRV are described in detail elsewhere(Reference Powers1). In brief, those for micronutrients are generally based on an estimate of an average biological requirement, an allowance for the bioavailability of the micronutrient from a diet typical of the population, and consideration of the variability of requirement between individuals, in order to derive an RNI that covers the needs of the majority (generally 97⋅5 %) of the population. Most DRV are developed separately for males and females, and for different ages in bands and, for females, by reproductive status.

The current micronutrient DRV for the UK population were first developed using these principles by the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy and published in 1991(2). Since that time, those for vitamins A, vitamin D, folate, calcium, sodium, iron, selenium and iodine have been reassessed by the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy and its successor, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, to take account of emerging research. However, new evidence did not lead to any revision of the DRV for these micronutrients, except for those for vitamin D, published in 2016(3). The Institute of Medicine (IoM) undertook the derivation of micronutrient dietary reference intakes for USA/Canada, published in a series of volumes from 1997 to 2001(4–7), with revised values for calcium and vitamin D in 2011(8) and for sodium and potassium in 2019(9). More recently, and consequently with a much larger evidence-base to call on, the European Food Safety Authority developed DRV for the EU in a rolling series of assessments for all the micronutrients, summarised in a Technical Report in 2017 (with an update in 2019 for sodium and chloride)(10).

Although there are subtle differences between the DRV developed by each of these three national authorities, the criteria on which they are based are remarkably similar. Table 1 provides, as an illustration, the criteria on which the DRV for eleven of the micronutrients were based for adults. These criteria fall into five main categories: (1) the amount of the micronutrient required to avoid the risk of deficiency, as defined by clinical signs or an accepted biochemical threshold; (2) the calculated amount of the micronutrient retained or turned over by the body plus any obligatory losses; (3) empirical data from balance or depletion–repletion studies, often based on biomarker assessments; (4) estimations of usual intake of assumed healthy people in the population, sometimes based on biochemical status markers and (5) the usual intakes of energy or protein, for those micronutrients required for the metabolism of those macronutrients. A sixth category, mooted strongly in the past 20 years, is an amount of the micronutrient that optimises function and health, at intakes above that needed to avoid overt deficiency. To date, however, a criterion of optimal health and disease risk reduction has only rarely been used for DRV development. This is discussed later for calcium and vitamin D.

Table 1. Criteria used in developing dietary reference values for eleven micronutrients: adults and children

* Developed and published by the Committee on the Medical Aspects of Food Policy 1991(2), unless otherwise stated.

† Developed and published by the Institute of Medicine in a series 1997–2001(4–7), unless otherwise stated.

‡ Developed and published by the European Food Safety Authority in a series 2013–2017(10).

§ Indicates whether body size is an intrinsic factor of the criterion.

** Published by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2016(3).

†† Developed and published by the Institue of Medicine 2011(8).

‡‡ Developed and published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019(9).

Sex differences in micronutrient requirements and dietary reference values

For the majority of micronutrients, the selected criterion for the biological requirement includes a component that is related to body size (Table 1), and because, on average, males and females differ in size, this automatically introduces the likelihood that adult micronutrient requirements differ by sex, and therefore that sex-specific DRV would be provided. However, relatively few of the adult DRV for vitamins and minerals developed by the Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy, IoM and European Food Safety Authority differ between men and women, and for those that do, this is mainly because the DRV were developed on the basis of the requirement expressed per unit body weight, or per intake of energy or protein. In such instances, the DRV for men is higher than for women when expressed on a unit weight daily basis, e.g. thiamin DRV when expressed in mg/d rather than mg/MJ. For a few micronutrients, the DRV for adult women is greater than that for men at certain ages, the most notable example being iron, which is higher in premenopausal women than men to cover losses during menstruation. The specific case of sex differences in requirements for calcium is discussed more fully later.

Similar considerations apply to children and adolescents. Micronutrient requirements for children and adolescents are generally based on those for adults with adjustments made for body size at each age (Table 1). For some micronutrients in the UK, an interpolation is made between the intake of the micronutrient from breast-milk in infancy and adult intake, using reference weight data to make allowance for size at different ages. In other instances, this is achieved by back extrapolation from adult values based on pro rata calculations, using median weights from reference data or, for some micronutrients in the USA/Canadian guidelines, metabolic weight (weight0⋅75) and a growth factor derived from the protein requirements for growth e.g.(4). The differences in body size between boys and girls throughout childhood and adolescence would indicate that there are sex differences in the dietary requirements for most micronutrients. However, as for adults, different DRV for boys and girls are only provided for some micronutrients, and often only for adolescence.

Pregnancy and lactation are times when sex differences in micronutrient dietary requirements would be anticipated because of the biological requirements for fetal growth and breast-milk production. An increment to the DRV for adolescent girls and premenopausal women is provided for some micronutrients to allow for these additional requirements, thereby adding to the sex differences in DRV. Where increments are provided (Table 2), these are based, in pregnancy, on fetal size or maternal tissue expansion and, in lactation, on the micronutrient content of breast-milk plus the breast-milk intake of breast-fed infants. However, for some micronutrients, there is evidence that such increments are not necessary because of physiological adaptive processes in the mother, such as enhanced intestinal absorption and renal conservation, or because the extra requirement is offset by reduction in needs elsewhere. An example of the former is calcium in pregnancy, when the calcium requirement for fetal growth is met by increases in maternal intestinal absorption and mobilisation of skeletal mineral (discussed in more detail later), and, of the latter, is iron in pregnancy, where the extra requirement for fetal growth is offset by cessation of menstruation in the mother.

Table 2. Criteria used in developing dietary reference values for eleven micronutrients: increments for pregnancy and lactation

* Developed and published by the Committee on the Medical Aspects of Food Policy 1991(2), unless otherwise stated.

† Developed and published by the Institute of Medicine in a series 1997–2001(4–7), unless otherwise stated.

‡ Developed and published by the European Food Safety Authority in a series 2013–2017(10).

§ Developed and published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019(9).

** Published by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 2016(3).

†† Developed and published by the Institute of Medicine 2011(8).

Requirements for calcium and vitamin D

Functional outcomes and disease risk reduction

As described earlier, there has been much interest in recent years in developing micronutrient DRV based on functional outcomes, intermediate health markers and disease risk reduction, especially where emerging research has suggested that greater amounts of the micronutrient might be required to prevent deficiency. Two interdependent micronutrients that have attracted much attention in this regard are calcium and vitamin D. Both are essential for skeletal growth and health, at all stages of the lifecourse from fetal life to old age. Classically, the requirements for these micronutrients have been based on their importance for the skeletal system. Calcium is a primary bone-forming mineral and 98–99 % body content of calcium is in the skeleton. Vitamin D, through its metabolites 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, is involved in the control of intestinal absorption, renal conservation and skeletal metabolism of calcium and other related minerals. However, 1–2 % calcium is widespread throughout the body, where it has essential cellular functions, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is important in the control of many genomic and other cellular processes. On this basis, the possibility that low intakes of calcium and/or poor vitamin D status are implicated in a wide range of non-skeletal conditions and chronic diseases has been proposed by many research groups and has been considered by the DRV Committees in recent years (Fig. 1). As there are known differences in the prevalence of many of these health outcomes between males and females, this might signal that the requirements for calcium and vitamin D may differ by sex. However, to date, the results of trials and other robust studies investigating these possibilities have either not indicated the anticipated health advantages, or, where there are links, these are generally not at calcium intakes or plasma 25(OH)D concentrations (the biomarker of vitamin D status) above those recommended on the basis of skeletal outcomes. As yet, none of the potential health outcomes listed in Fig. 1 has been used for DRV development, except for muscle weakness/falls for vitamin D e.g.(3).

Sex differences in calcium requirements and dietary reference values

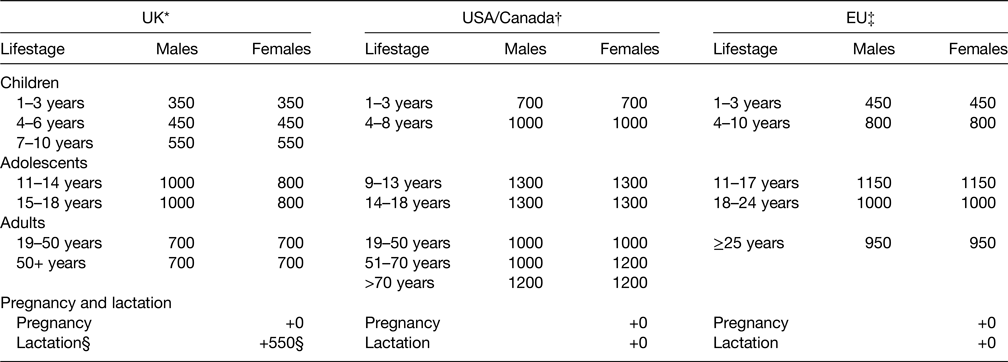

Because there is no recognised specific indicator or biomarker of calcium adequacy, bone mineral content (BMC), bone mineral density (BMD), bone health and fracture risk are considered the main health outcomes for this micronutrient, whereas DRV development is generally based on calcium retention estimated on theoretical grounds from reference data or measured empirically in balance studies. The factorial method is used for children and adolescence, whereby the calcium retention at each age required for skeletal mineral accretion is combined with estimates of calcium absorption from a diet typical of the population (usually about 30 % in Western countries) and losses in urine, faeces and sweat to provide an average dietary requirement on which the DRV are derived (Table 1). Calcium retention is estimated from reference BMC/BMD and growth data and from calcium balance studies. In theory, therefore, because boys are taller than girls on average at the same age, with bigger skeletons, there is an expectation of sex differences in skeletal calcium accretion and thus in the DRV for children and adolescents. To date, none of the three DRV Committees have recommended different calcium DRV for boys and girls, except by the UK for ages 11–18 years (Table 3). Averaged data are used at each age. This implies that more boys than girls will exceed the 97⋅5 percentile on the average distribution of requirements, meaning that the needs of more than 2⋅5 % of the tallest boys might not be met by the RNI (but fewer than 2⋅5 % of girls), whereas more girls than boys will fall under the 2⋅5 percentile on the average distribution, resulting in an overestimate of girls and an underestimate of boys with a requirement not met by the lower RNI (a risk indicator in the UK).

Table 3. Dietary reference values for calcium (mg/d)

* Reference nutrient intake, developed and published by the Committee on the Medical Aspects of Food Policy 1991(2) and re-evaluated and endorsed in 1998(14).

† RDA, developed and published by the Institute of Medicine 2011(8).

‡ Population reference intake, developed and published by the European Food Safety Authority 2015(41).

§ Lactation for 0–4 months and >4 months; indicated in 1998 that the increment ‘may not be necessary’(14).

Similar considerations pertain to the calcium requirements for adult men and women, with values based primarily on calcium retention from balance studies. Osteoporotic fracture risk and bone mineral loss increase in later life are greater among women than men, especially during the menopause. In the past, there was a presumption that this reflects a degree of calcium deficiency and therefore that calcium requirements increase with age and are greater in women. However, in general, the results of randomised trials and other studies have not borne this out e.g.(Reference Kahwati, Weber and Pan11,Reference Uusi-Rasi, Kärkkäinen and Lamberg-Allardt12) . Associations between BMC/BMD, fracture risk and customary diet within populations are inconsistent, and on a world-wide basis, populations with a lower risk of osteoporotic fracture are ones with lower customary calcium intake(Reference Prentice13). The evidence is further complicated by the fact that calcium is an antiresorptive agent i.e. it reduces the rate of bone resorption during bone remodelling cycles(Reference Prentice13). Increases in calcium intake, generally by using supplements, therefore produce a measurable but small increase in BMC and BMD for a period of time, a phenomenon known as a bone remodelling transient, but do not slow the rate of bone loss(Reference Prentice13). The use of calcium supplementation to reduce bone resorption at times of bone loss can, therefore, be considered more a pharmacological intervention than a correction of dietary deficiency. None of the three DRV Committees felt able to use BMC/BMD or fracture risk as criteria for setting DRV for calcium(2,8,14,15) . However, the IoM did include an increment above the young adult value for menopausal women of 200 mg Ca/d to ‘err on the side of caution’ in recognition of the effects of an increase in calcium intake on BMD at this stage of life, thereby introducing a sex difference in the USA/Canadian dietary reference intake(8). They also applied the same increment for both men and women >70 years of age (Table 3).

Calcium is essential for fetal growth and breast-milk production at amounts within the distribution of maternal calcium intakes(Reference Prentice, Glorieux, Pettifor and Juppner16). This raises the possibility that women of reproductive age have higher dietary calcium requirements during pregnancy and lactation than other adults. However, it has been recognised for many years that women in populations with a low calcium intake can have many cycles of pregnancy and lactation without apparent calcium deficiency or detriment to their long-term bone health(2,Reference Walker, Richardson and Walker17) . Physiological adaptations including increased intestinal calcium absorption, mobilisation of bone mineral and, in lactation, renal calcium conservation appear to provide sufficient calcium to meet these requirements without requiring greater dietary calcium intake by the mother(Reference Prentice, Glorieux, Pettifor and Juppner16,Reference Olausson, Goldberg and Laskey18) . This is discussed in more detail later.

Sex differences in vitamin D requirements and dietary reference values

Unlike other micronutrients, vitamin D can be synthesised in the skin by the action of UV light B contained in sunlight. A dietary source of vitamin D is required to maintain good vitamin D status when skin UV light B exposure is limited or sunlight contains little or no UV light B, such as during the winter in temperate countries. In such circumstances, certain population sub-groups are especially vulnerable to limited skin synthesis and poor vitamin D status. The provision of DRV for vitamin D is to achieve vitamin D sufficiency across the population in all groups. The biomarker of vitamin D status is the circulating metabolite 25(OH)D, and the concentration of 25(OH)D below which there is an increased risk of rickets and osteomalacia is used as the main criterion for DRV development for vitamin D, combined with judgements about other aspects of musculoskeletal health such as BMC/BMD, muscle strength, falls, fracture risk and calcium absorption. The dietary intake required to achieve the selected 25(OH)D concentration in the absence of UV light B skin exposure is then used to develop the DRV, using data from supplementation and dose-ranging studies. In general, these studies show that children, adolescents and older persons require similar dietary intakes of vitamin D over a period of time to achieve specific 25(OH)D concentrations with no indication of any difference by sex. Consequently, in each of the three sets of DRV, although different threshold values of 25(OH)D concentration may have been selected for DRV development resulting in different recommended intakes of vitamin D, the same values apply to both males and females and at all stages of the lifecourse except for infancy. The exception is that IoM added an increment to the dietary reference intake for both men and women >70 years, an approach ‘predicated on caution in the face of uncertainties’(8) relating to vitamin D intake and fracture risk in older adults.

The same considerations apply to women during pregnancy and lactation, and none of the three DRV committees considered that increasing the DRV above that of adults is necessary. However, recent studies suggest that there may be benefits of a higher dietary intake of vitamin D by women during pregnancy and lactation than those currently recommended to boost neonatal and infant vitamin D status, and potentially improve maternal and offspring health outcomes(Reference O'Callaghan, Hennessy and Hull19–Reference Kiely, Wagner and Roth21). This is a topic of current controversy(Reference Kiely, Wagner and Roth21) and is discussed more fully elsewhere(Reference Kiely22).

Sex-specific findings in Gambian and UK studies of calcium requirements

The Gambia, West Africa, has a diet typical of many around the world where milk and milk products are rarely consumed or are in short supply(Reference Prentice13). Calcium intakes in the resource-poor rural regions of The Gambia are very low, averaging three to four times less than those indicated by the DRV of the UK, USA/Canada and European Food Safety Authority(Reference Prentice23). The MRC Nutrition and Bone Health Group has conducted detailed studies over many years, to provide evidence of the health benefits for the people of The Gambia of a higher calcium intake(14,Reference Prentice, Jarjou and Cole24–Reference Prentice, Ginty and Stear39) . This has been through randomised, placebo controlled trials with long-term follow-up and longitudinal cohort studies, complemented by similar investigations using identical methods and technologies in Cambridge, UK. These have generally not demonstrated the anticipated benefits of higher calcium intakes but, instead, have shown some unforeseen, sex-specific effects with potential consequences for health.

An early trial by this group in lactating Gambian women, who were supplemented for 12 months from 2 weeks postpartum with 1000 mg Ca/d as calcium carbonate or placebo, was designed to determine the effect on maternal BMC/BMD, biochemical markers of bone turnover, breast-milk calcium content and infant growth(Reference Prentice, Jarjou and Cole24). No significant differences were observed between the mothers and infants in the supplemented and placebo groups for these outcomes. There was, however, evidence in both groups of mothers of bone mineral mobilisation in the first months postpartum with restoration later in lactation, in a similar way to lactating women in Cambridge(Reference Prentice, Jarjou and Cole24,Reference Laskey, Prentice and Hanratty25) . These findings added to the accumulating evidence at that time that bone mobilisation is a physiological aspect of lactation and that breast-milk calcium content is not responsive to maternal calcium intake(Reference Prentice26–Reference Prentice, Laskey, Jarjou, Bonjour and Tsang28). These studies formed part of the evidence that an increase in dietary calcium intake is not necessary during lactation(14). DRV for women developed since that time are the same as those for women and men of the same age (Table 3).

A subsequent trial of pregnant women, who were supplemented from 20 weeks of gestation to delivery with 1500 mg Ca/d as calcium carbonate or placebo, was designed to determine the effects of the higher calcium intake on maternal blood pressure and offspring size at birth, and on postpartum maternal and infant BMC/BMD, breast-milk calcium content and infant growth(Reference Jarjou, Prentice and Sawo29–Reference Goldberg, Jarjou and Cole31). None of the anticipated benefits were found, as there were no significant differences between the groups in maternal blood pressure, breast-milk calcium content or fetal and infant growth(Reference Jarjou, Prentice and Sawo29,Reference Goldberg, Jarjou and Cole31) . Unexpectedly, however, those women who had received the calcium supplement in pregnancy exhibited greater bone mobilisation postpartum than those in the placebo group(Reference Jarjou, Laskey and Sawo30). In a follow-up study of the mothers after approximately 5 years when the women were neither pregnant nor breast-feeding, we showed the expected restoration of BMC/BMD in the mothers in the placebo group but not in those who had received the calcium supplement(Reference Jarjou, Sawo and Goldberg32). This opens the possibility that, rather than a benefit, the increase in calcium intake during pregnancy may have had a negative effect on the mother's long-term bone health. To investigate this possibility, a further set of measurements after approximately 20 years has recently been completed, currently under analysis, to determine the impact of calcium supplementation in pregnancy on maternal bone health in mid-life.

Unexpected results have also emerged from follow-up studies of the offspring of these mothers during childhood and adolescence(Reference Prentice, Ward and Nigdikar33,Reference Ward, Jarjou and Prentice34) . These have demonstrated significant sex-specific effects of the maternal supplement on pre-pubertal child growth and bone development at age 8–12 years, such that those girls whose mothers had received the calcium supplement in pregnancy were shorter, lighter and with smaller bones with less bone mineral than girls whose mothers had been in the placebo group. The effects in the boys were the converse, with those whose mothers had received the pregnancy calcium supplement tending to be larger with greater bone mineral than boys whose mothers had been in the placebo group(Reference Ward, Jarjou and Prentice34). These effects on growth and bone development were associated with the corresponding sex-specific effects of the maternal supplement on offspring plasma insulin-like growth factor 1 concentration in mid-childhood(Reference Prentice, Ward and Nigdikar33). This suggested that the calcium carbonate supplement had altered the in utero programming of the offspring growth hormone–insulin-like growth factor 1 axis differently in boys and girls, an effect which might be expected to result in sex-specific effects on the timing of puberty and on adolescent growth of the offspring. This possibility is being investigated in continuing follow-up studies.

Such possibilities have also been suggested by the results of supplementation trials and follow-up studies of pre-pubertal children in The Gambia(Reference Prentice, Dibba and Sawo35,Reference Ward, Cole and Laskey36) and of adolescents in Cambridge(Reference Ginty, Prentice and Laidlaw37). Gambian boys who participated in a supplementation trial at age 8–12 years, using 750 mg Ca/d calcium carbonate or placebo, entered their pubertal height spurt earlier if they had previously received the calcium supplement than boys in the placebo group(Reference Prentice, Dibba and Sawo35). As a result, the boys in the calcium group were taller in mid-adolescence compared to the placebo group, but they stopped growing earlier and were shorter in young adulthood, with similar effects on the timing of bone development(Reference Prentice, Dibba and Sawo35,Reference Ward, Cole and Laskey36) . No such effects were observed in the girls(Reference Prentice, Dibba and Sawo35,Reference Ward, Cole and Laskey36) . In Cambridge, 12–15 months of supplementation with 1000 mg Ca/d as calcium carbonate resulted in greater height and skeletal size but no effect on BMC after size-adjustment in 16–18-year-old boys compared to placebo, whereas the calcium supplement resulted in greater size-adjusted BMC but not stature in girls(Reference Stear, Prentice and Jones38,Reference Prentice, Ginty and Stear39) . In both Cambridge trials the calcium supplement was associated with an increase in the circulating concentration of insulin-like growth factor 1(Reference Ginty, Prentice and Laidlaw37). The effect of the calcium carbonate supplementation is likely to represent increased bone growth in the boys and a bone remodelling transient in the girls, similar to that described earlier for perimenopausal women. In both the Gambian and Cambridge studies, the girls may have been at a later stage of skeletal maturation than the boys at the start of the trials, which may account for some of the sex-specific differences observed. This is because there is a discordance between boys and girls in the timing of pubertal changes and in the cessation of linear growth caused by fusion of the epiphyses at the ends of long bones, with girls maturing at earlier ages than boys.

Studies such as these suggest the possibility that boys and girls may have subtly different calcium requirements, and that these may be influenced by maternal calcium intake during pregnancy, by changes in calcium intake during childhood and adolescence and by the timing of any intervention relative to the various hormonal and skeletal changes that occur between conception and adulthood. These effects may be due to alterations in the trajectories of growth, resulting in changes to the timing of the pubertal growth spurt and potentially affecting adult size and skeletal characteristics.

DRV are designed to meet the needs of healthy individuals, including pregnant women, when all other nutrient requirements are met, to prevent insufficiency. Calcium supplements are also prescribed medically to treat certain conditions, such as menopausal and age-related osteoporosis, usually as an adjunct to other medications. The WHO currently recommends pregnant women in populations with a low calcium intake to take a calcium supplement of 1500–2000 mg/d to prevent pre-eclampsia and its complications, based on the results of several randomised controlled trials(40). To date, there have been no studies to investigate whether this population-based recommendation has long-term consequences for maternal bone health or offspring growth and development similar to the effects observed in the Gambian studies.

Conclusions

Sex differences in micronutrient requirements that are reflected in DRV guidelines are mostly to cover differences in body size or macronutrient intakes, although often average values for males and females are given. To date, little account has been taken of more subtle effects on sex differences in growth and maturation rates, health vulnerabilities or in utero and other programming effects. Future research may allow more nuanced sex-specific guidelines. These need to consider potential disadvantages and harms as well as benefits of intakes of micronutrients above those currently consumed by apparently healthy people, and to evaluate possible long-term metabolic consequences on body systems not related to the primary outcome of interest. As studies by the MRC Nutrition and Bone Health Group of calcium requirements in The Gambia and Cambridge have suggested, more is not necessarily better. For the present, however, with the limited evidence available for most micronutrients, current DRV values provide the best estimate of population dietary requirements, thereby ensuring adequacy for the majority of individuals, and the provision of average DRV for males and females simplifies, and therefore strengthens, public health messages.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study participants and of all members and supporting staff, past and present, of the MRC Nutrition and Bone Health Group in Cambridge and the Calcium, Vitamin D and Bone Health Group in The Gambia.

Financial Support

The Gambian and Cambridge studies described in the present paper were supported by Medical Research Council (Programmes U105960371, U123261351 and MC-A760-5QX00) and the Department for International Development (DfID) under the MRC/DfID Concordat. Where there was additional funding for individual components of these studies, they are listed in the published papers cited.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authorship

The author had sole responsibility for all aspects of preparation of this paper.