Introduction

Ageing and work

As the population of developed countries ages, many organisations will find themselves faced with the challenges associated with an ageing workforce. In 2014, 75.3 per cent of all 50–64 year olds in the United Kingdom (UK) were in some form of employment; this proportion has been steadily increasing since the early 1990s, indicating that more people are working into later life. A further 12.1 per cent of people past state pension age are engaged in the labour market (Office for National Statistics 2014). In response to the population changes, governments across Europe and beyond are increasing the age of retirement (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2014). As an example of policy change, the UK government has removed the default retirement age of 65 and increased the statutory pension age to 66, rising eventually to 69 or 70 in order to extend working lives and reduce economic burden.

Working until later life can have positive financial impacts on the economy, businesses and individuals (Brown, Orszag and Snower Reference Brown, Orszag and Snower2008). Similarly, there may be further benefits to the individual. A recent review found that continued work in later life has a role to play in promoting good physical and mental health (Staudinger et al. Reference Staudinger, Finkelstein, Calvo and Sivaramakrishnan2016). Other research has shown this can result in improved wellbeing (Hershey and Henkins Reference Hershey and Henkens2014) and, in some occupations, improved cognitive functioning (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Stachowski, Infurna, Faul, Grosch and Tetrick2014). However, many researchers argue that organisations are not well equipped to support an ageing workforce and have uncovered negative attitudes towards older workers and poor practice for supporting older workers, including a lack of formal performance appraisal measures (Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development 2011; Danson and Gilmore Reference Danson and Gilmore2012; VanDalen, Henkens and Wang Reference VanDalen, Henkens and Wang2015). One concern is that employers have not considered the impact health problems, which have previously been associated with older age and retirement, may have on the workplace (McNamara Reference McNamara2014). An example of this is dementia, which is most commonly considered a condition of later life, although it also affects younger people. This is often referred to as ‘early onset dementia’. The purpose of this paper is to report the findings of case study research which addresses the gap in knowledge about the work-related experiences of people diagnosed with dementia before their expected age of retirement.

Dementia in the workplace

Dementia is an umbrella term referring to a number of neurological disorders which cause a progressive decline in cognitive functioning. There are many different types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia and fronto-temporal dementia. Symptoms include memory impairment, reduced ability to learn new material, sensory impairments, speech and communication problems, and personality changes. Dementia most often occurs in people over the age of 65, however, it is estimated that around 40,000 people under the age of 65 in the UK currently have a diagnosis of dementia (Alzheimer's Society 2014). Younger people with dementia are more likely to be in employment when they receive their diagnosis as well as having other responsibilities such as mortgages, dependent children or ageing parents (Pipon-Young et al. Reference Pipon-Young, Lee, Jones and Guss2012). This, coupled with the recent policy changes relating to state pension age and the push for early diagnosis of dementia by national dementia strategies (Department of Health 2013; Scottish Government 2013), means that the number of people who are still in employment when they are diagnosed with dementia will rise (Harris Reference Harris2004).

A recent literature review reported a dearth of evidence concerning the experiences of people who develop dementia while in employment, and a widely held assumption that post-diagnosis employment was not possible (Ritchie et al. Reference Ritchie, Banks, Danson, Tolson and Borrowman2015). It is widely recognised that younger people with dementia are more likely to be in employment at the time of their diagnosis (e.g. Harris Reference Harris2004). Bentham and La Fontaine (Reference Bentham and La Fontaine2005), focusing on services for younger people with dementia in the UK, noted that it is not unusual for people with early symptoms of dementia to be made redundant or to be dismissed for incompetence before they are diagnosed. They found that some younger people with dementia wished to remain in employment, and suggested that efforts should be made to persuade employers to support people to retain appropriate employment and/or to recognise dementia as a reason for early retirement so that pension rights and other benefits are not affected.

Previous research has highlighted that getting a diagnosis of dementia can be a lengthy process, especially for a younger person (Harris Reference Harris2004; Roach et al. Reference Roach, Keady, Bee and Hope2008), and it is common in this period for a person with dementia to either leave work or go on sick leave before they have a diagnosis due to the stress associated with trying to cope in the workplace without knowing what is wrong (Chaplin and Davidson Reference Chaplin and Davidson2016; Ohman, Nygard and Borell Reference Ohman, Nygard and Borell2001). The interaction of undiagnosed dementia with an ever-stricter social security regime threatens increasing numbers with sanctions, loss of welfare payments and poverty. Furthermore, after receiving a diagnosis, the majority of people with dementia do not see returning to work as an option (Ohman, Nygard and Borell Reference Ohman, Nygard and Borell2001), stretching loss of income and financial disruption into the years ahead.

A number of authors highlight the need for occupational health professionals to be aware of the problems and to be proactive in helping people to gain a diagnosis and secure support to retain employment where possible (Chaston Reference Chaston2010; Martin Reference Martin2009; Mason Reference Mason2008). Similarly, Alzheimer's charities have recognised this and have begun to produce guidelines and advice for employers to support employees who develop dementia (e.g. Alzheimer's Society 2015a). However, there is a dearth of research focusing on the experiences of people with dementia in employment and the nature of help that may be required to support continued employment. It is thought that simple changes such as using memory aids, providing written information and quiet work areas could be useful (Ohman, Nygard and Borell Reference Ohman, Nygard and Borell2001); nevertheless, this would be dependent on the type of job the individual does.

Continuing employment post-diagnosis of dementia could have many advantages for the individual and the wider organisation. Notwithstanding the financial benefits of continued employment, there may also be many social and psychological benefits for the individual. Much has been written about the problems associated with an unplanned early labour market exit in later life, including increased incidences of depression (Christ et al. Reference Christ, Lee, Fleming, LeBlanc, Arheart, Chung-Bridges, Caban and McCollister2007), lower wellbeing (Bender Reference Bender2012), a loss of identity (Gabriel, Gray and Goregaokar Reference Gabriel, Gray and Goregaokar2010) and loss of social networks (Lancee and Radl Reference Lancee and Radl2012). Continuing employment post-diagnosis could alleviate some of these potential issues at a difficult time in the person's life, allowing them time to adjust to their diagnosis and make plans for leaving employment at a later date. Similarly for employers, continuing employment prevents the immediate loss of skilled labour (Pejrova Reference Pejrova2014), helps to promote a good working environment within the company as co-workers perceive their colleagues being treated fairly (Hashim and Wok Reference Hashim and Wok2014) and may also promote the corporation as being socially responsible (Dibben et al. Reference Dibben, James, Cunningham and Smythe2002). Theory and practice recognises that employers adopt strategies to retain core workers during recession, structural market changes and individual challenges (Doeringer and Piore Reference Doeringer and Piore1985; Hakim Reference Hakim1990), so it might be expected that efforts would be made to accommodate workers who develop symptoms of dementia where the enterprise has invested in the development of their human capital and where they still display value to the operations of the business.

Policy landscape

Given the changes in policy relating to retirement age, it is timely to explore the employment-related experiences of people who develop long-term chronic conditions such as dementia. The World Health Organisation (2012) has declared dementia an international public health priority and many governments across Europe have developed their own dementia strategies or plans (e.g. Alzheimer Europe 2016; Department of Health 2013; Scottish Government 2013). The focus of these strategies is to implement policies which enable people with dementia to live well with the condition. Improving diagnosis rates, with a focus on earlier diagnosis, has been a starting point for many countries, as has improving the care of people with dementia post-diagnosis. Although employment for people with dementia is not explicitly addressed within these strategies, if a person with dementia is still in employment, accessing an early diagnosis and appropriate post-diagnostic support may allow them to continue employment. Much of contemporary policy in health and social care advocates a focus on the person with dementia. Accordingly, person-centred practice has become the service mantra and a feature of national dementia strategies and action plans (Department of Health 2013; Scottish Government 2013). Descriptions of person-centred approaches (McCormack Reference McCormack2004) highlight the importance of knowing the person in terms of who they are, their relationships with others and the contexts through which their personhood is articulated.

Employment and, even more significantly, welfare policies emphasise the centrality of ‘work’ to the lives and contributions of members of society (House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee 2015) so that, while discrimination and employment laws have an important role to play in framing the environment for how workers developing symptoms of dementia are treated by employers and co-workers, there may well be overwhelming concerns over the financial, social security and status implications of diagnosis. The complexity of the social security system, especially for those without a diagnosis in a flexible labour market, undoubtedly emphasises the importance of retaining a job where possible.

Theoretical perspectives

A lack of public understanding and the associated stigma of dementia are a challenge faced by society in implementing the policies relating to living well with dementia. Experiencing stigma can have an impact on the psychological wellbeing of the person with dementia (Swaffer Reference Swaffer2014) as well as the support and services they access (Milne Reference Milne2010). A person's sense of self is closely tied to their occupation, and their perception of who they are is closely tied to what they do (Ross and Buehler Reference Ross, Buehler, Brewer and Hewstone2004). Thus, when a person loses their job unexpectedly, they can suffer a loss of identity or sense of self. Furthermore, preserving identity in early stage dementia is thought to be linked closely to ‘being valued for what you do’ and ‘being valued for what you are’ (Steeman et al. Reference Steeman, Tournoy, Grypdonck, Godderis and De Casterlé2013), which highlights the value that continued employment may have to a person with dementia. For an individual who is still in employment, how they manage stigma will be important for their social and emotional wellbeing post-diagnosis. Stigma may result in a person being reluctant to disclose their diagnosis to their employer and they may worry about facing discrimination within the workplace. However, continuing employment post-diagnosis may be an opportunity to challenge this stereotype and associated stigma, by highlighting the skills and abilities the person has retained, as well as providing continued social support. Goffman's (Reference Goffman1963) theory on stigma states that an individual can develop a ‘spoiled identity’ as a result of being stigmatised. Link and Phelan (Reference Link and Phelan2001) further defined stigma as the co-occurrence of four components: labelling, stereotyping, separation and discrimination. The presence of stigma or perceived stigma in the workplace may influence an individual's decision to continue working. However, if stigmatisation could be addressed and myths dispelled, post-diagnostic employment could be beneficial for individuals and feel achievable for employers.

Population ageing and the rising numbers of people diagnosed with dementia, coupled with the policy imperative for longer working lives, provides the backdrop to this study. Furthermore, the implicit message in the literature of a possible ambivalence towards dementia as a disability and suggestions of inequality are morally troubling. These reasons, coupled with the knowledge that social isolation and a lack of stimulation amplify problems for individuals beyond those associated with the dementia trajectory alone (Shankar et al. Reference Shankar, Hamer, McMunn and Steptoe2013), confirm the need for this research.

Study aim

This study aimed to explore the employment-related experiences of people with dementia, and attitudes of employers and/or co-workers towards supporting people with dementia, in order to identify the potential for continued employment post-diagnosis.

Method

Case studies

Case study research involves an empirical investigation of a particular contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context using multiple sources of evidence (Robson Reference Robson1993; Yin Reference Yin2013). In this study, the phenomenon of interest was the experience of developing dementia during employment. The study was designed following consultation with people with dementia and their families who highlighted employment as an important and multifaceted issue for them following diagnosis. It was agreed that case study research was appropriate given the complexities associated with obtaining a diagnosis of dementia and working. It mattered to individuals that the study captured the experiences from their own perspective, close family and also of people in their workplace. Taking account of these stakeholder perspectives also aligned with recommendations in the literature (Baxter and Jack Reference Baxter and Jack2008) and contributed to the triangulation of data, promoting confidence in interpretation of findings.

Each of the 16 case studies was based around an individual who has a diagnosis of dementia and was in paid employment or had left within the previous 18 months. The person with dementia (the participant) then nominated additional participants to inform the case study, including a family member or friend and a workplace representative.

Recruitment

A project reference group was established to support and inform the development of the project, including health-care professionals, representatives from employer organisations and research network volunteers from the Alzheimer's Society. The reference group supported recruitment of the study by acting as gatekeepers to a range of organisations. Recruitment occurred through a number of organisations including the Alzheimer's Society, Scottish Clinical Dementia Research Network, Alzheimer Scotland and the National Health Service. Potential participants were given written information about the study and either contacted the research team directly to volunteer or gave permission for their details to be passed to the research team to initiate contact. A member of the research team then contacted the participant to arrange an initial meeting to discuss the project before they made a decision to participate. Participants were requested to sign written consent forms and reassured that they may withdraw from the study at any time without explanation or redress. Interview times and venues were negotiated and interviewees were asked to verbally consent to the commencement of the audio recording at the start of the actual interview and could request cessation of recording at any point during the conversation. At the end of the interview, the participant with dementia was invited to provide contact information for a workplace representative to assist in the building of the case study. All participants were provided with written information sheets explaining the purpose of the study, detailing interview procedures and strategies to maintain confidentiality and their right to withdraw at any time. Opportunity to seek clarification was provided prior to obtaining written consent. Figure 1 shows the inclusion criteria for the case study participants.

Figure 1. Inclusion criteria for case study participants.

Data collection

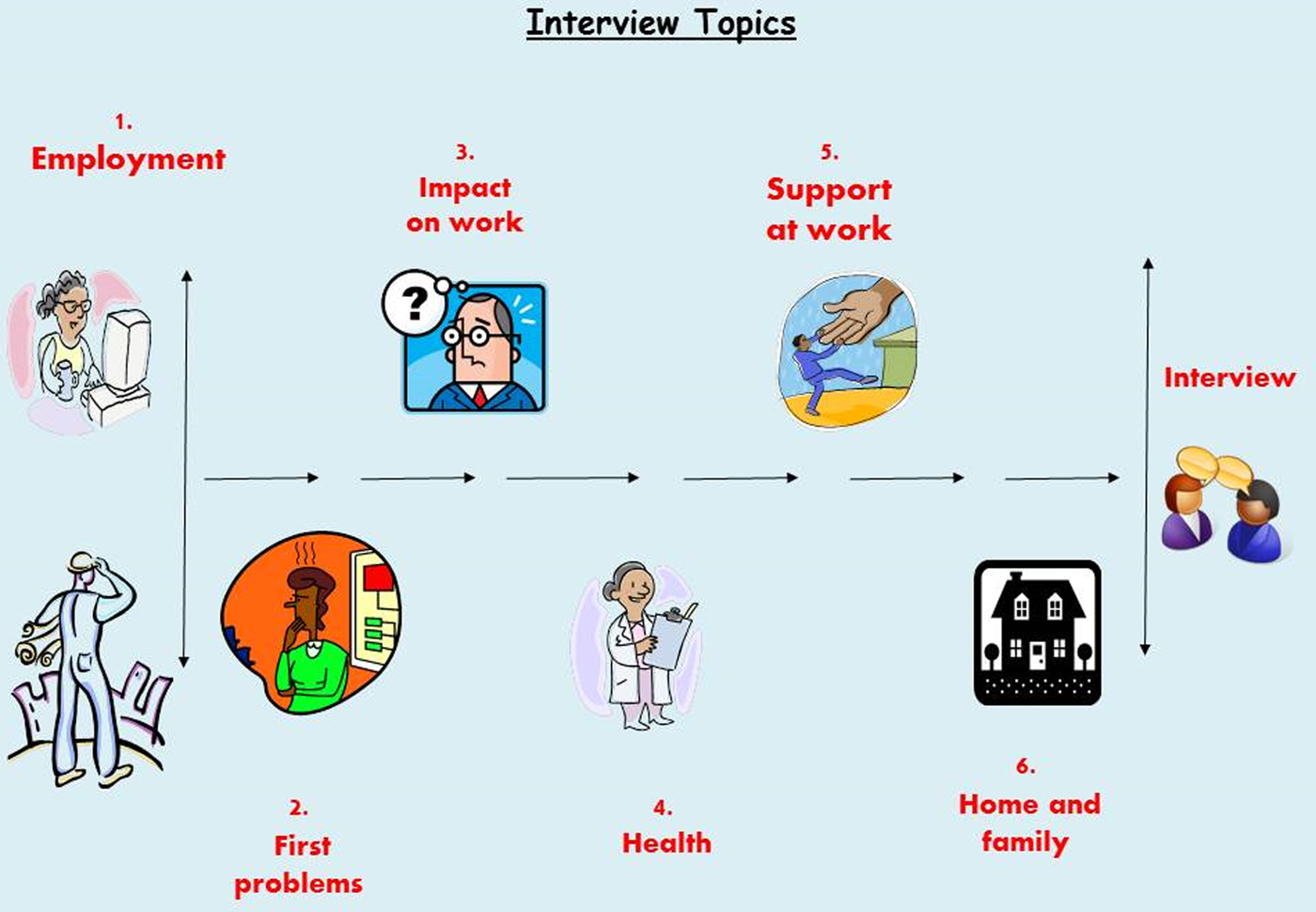

Data collection involved individual interviews with the person with dementia, their family members, a workplace representative and other relevant individuals, including health-care professionals. Because the situation in each case study is different, interviews were based around topics rather than an interview schedule. These topics were: (a) employment; (b) first problems; (c) impact on work; (d) health; (e) support at work; and (f) family and home life. Interviews with participants with dementia utilised an original visual tool (see Figure 2), printed on a laminated card, influenced by Timeline and Lifegrid approaches (Adriansen Reference Adriansen2012; Blane Reference Blane2003).

Figure 2. Interview topics.

This tool was piloted with volunteers with dementia who welcomed the visual prompts based on iconic symbols, as this helped them to assemble thoughts during the interview process and direct the flow of the conversation. The visualisation of the topic enabled participants to have an idea of what was coming next, also pausing to refer to the topic card was a dignified way for the person to influence the pace and focus of the interview. Flexibility was inherent in the flow of the interview topics and sometimes individuals returned to topics several times, and the interviewer could encourage moving on to another topic either by a verbal prompt or pointing to another image.

Data analysis

All interviews were audio recorded with participants’ consent, then transcribed and anonymised prior to analysis. Each case study was analysed individually and full descriptions of the individual case studies are published elsewhere (Tolson et al. Reference Tolson, Ritchie, Danson and Banks2016). In order to explore the commonalities of experience of the participants, a thematic analysis was carried out across all the interviews included in the 16 case studies which is presented below. This followed Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six phases of thematic analysis. A coding schedule was developed after initial familiarisation of the data. This was then applied on a case-by-case basis, altering, revising and checking codes in a cyclical process. To promote rigour, two members of the research team were involved in this stage, in order to check agreement of the codes. Then, the research team met to discuss the codes and group them into emerging themes and consulted the project's Alzheimer's Society Research Network volunteers. These themes were then refined and developed until three overarching themes were clear in the data, each with a number of sub-themes. These themes are presented below.

Participants

Sixteen case studies were developed. Table 1 outlines the main characteristics for each participant and lists the relationship of the additional case study participants to the person with dementia. All participants were given a pseudonym to preserve anonymity.

Table 1. Overview of case study characteristics

All but one case study included a family member; however, there were issues with recruitment of workplace representatives in five case studies. Reasons for this varied, including the place of work having closed down so there were no contact details, and problems contacting and scheduling interviews with workplace representatives.

Findings

The analysis produced three themes in the data: Theme 1: Dementia as experienced in the workplace; Theme 2: Work keeps me well; and Theme 3: Wider impact of dementia in the workplace. Table 2 shows the development of these themes.

Table 2. Codes and theme development

Theme 1: Dementia as experienced in the workplace

Each case study presented a personal experience of dementia in the workplace. However, it was clear that employment was important to the participants and there were many shared experiences. This theme explores the experiences and implications of developing dementia whilst in employment, highlighting the supports which enabled continued employment but also the experiences of those who did not continue employment post-diagnosis.

Recognising dementia

The case studies highlighted the difficulties associated with the diagnosis of dementia, with six of the participants having long delays to their diagnosis. Emerging symptoms were often explained by situational factors or misdiagnosed as other disorders or mental health problems. During this period, many of the participants were continuing to work with awareness that ‘something was not right’ but with no understanding of what that might be.

So I've been stumbling around trying to make sense of it whilst, you know, professionals were going ‘oh it could be this, could be that’. (John, CS05, lecturer/journalist)

Throughout this period, employers were often aware of the problem their employee was having, although there was little consideration about the risks involved and little support offered to them. This potentially puts the person and other employees at unnecessary risk. Judgement of the participants’ abilities appeared to be based on their previous skills and abilities, with no understanding that there may be a serious underlying cause.

I phoned his immediate senior, who said yeah they had, they knew something was wrong but because he's got such knowledge of his craft … it was just like seen as an idiosyncrasy. (Phil's partner, CS16, off-shore safety inspector)

It was clear that in the pre-diagnosis period, little support was offered to the participants who were clearly struggling in their workplace. The longer the time period between the emergent symptoms and getting a diagnosis, the more likely it was that participants would have to go on sick leave before this was confirmed.

Symptoms experienced in the workplace

Participants reported a variety of symptoms which impacted on their employment, this included memory problems, problems with communication, visuo-spatial difficulties, and an impaired ability to learn and process information. The impact of the symptoms varied depending on the types of jobs and activities that the participants were employed to do. Some participants were able to cope with the symptoms they experienced in the workplace as they did not directly impact on their ability to carry out their job; for example, it may just take them longer to complete but their knowledge of the job was unimpaired.

That's why I'm comfortable at the moment carrying on working because I still know more than them [the team]. (Rose, CS08, team leader)

However, in many of the participants’ roles, their symptoms impacted directly on their ability to carry out their jobs; for example, the journalist found his communication skills were particularly affected which meant he was not able to perform well as a contributor on live radio programmes or the heavy goods vehicle (HGV) driver could not retain his licence post-diagnosis. This meant that, at an early stage, continued employment post-diagnosis was not possible for these participants in the jobs they were doing.

Leaving employment

The experience of leaving employment varied greatly between the participants; the majority who left did so after receiving their diagnosis, normally after being out of the workplace on sick leave for a period pre-diagnosis. However, two participants lost their jobs before their diagnosis because they were not performing well. In the cases where the participant was on sick leave when they received their diagnosis, returning to work was not given serious consideration by the employer, regardless of whether the participant wanted to return or not. Many of the organisations had a policy of offering redeployment or retirement in these situations. However, in the cases where this was available, participants felt that redeployment to a more suitable role was not seriously considered by their employers.

The first meeting we went to they said there were three options which were retirement, retirement due to ill health and redeployment but the redeployment, it was just mentioned and moved on. (Alison's husband, CS14, maternity care assistant)

Participants reported that they felt they had little control over the decisions for them to leave employment and many had long periods of uncertainty waiting for employers to make a decision about their future.

For all, leaving employment at this point was not something they had planned for and resulted in financial problems for many of the participants. However, for the two who lost their job before diagnosis, the immediate loss of income and difficulties in accessing benefits resulted in serious financial difficulties for their families and significant distress for the participant while going through the diagnostic process.

I've not had any money since September last year. (Mary, CS13, office manager)

Experiences varied greatly for all those participants who had left employment; however, it is clear that the support received could have been improved to assist the process of leaving employment and dealing with the associated paperwork for pensions and benefits. A number of the participants felt they had left employment on bad terms, either feeling pushed out or that they could have been better supported, which meant they experienced disappointment and resentment towards how their working life ended.

I'm desperately disappointed, humiliated and I've never been back to the place since, not to visit at all because I just felt I was squeezed out really. (Tom, CS10, projectionist)

Participants who had been on sick leave for a period before leaving employment felt that the communication from their employers was poor which contributed to their negative feelings about the process of leaving employment.

I was sat at home and no decisions made until much later on when they suddenly said ‘we're going to retire you’. (Edward, CS06, judge)

Leaving employment was not an easy process for any of the participants, and their experiences indicate that appropriate support for leaving employment was not available.

Supporting continued employment

The Equality Act 2010 (UK Government 2010) states that employers have a duty to make reasonable adjustments to the job description or work environment of an employee with a disability to allow them to retain or access employment. There was no direct mention of the Equality Act 2010 within the case studies; however, there were many examples of adjustments to participants’ roles with the aim of supporting their continued employment. Adjustments to the participants’ working patterns were common. Other common adjustments were the use of memory cues; for example, the use of calendars, diaries and mobile phones. Other case studies saw the participant having a change in their job description reflected in a reduction of the tasks they were required to do or the number of hours they worked. Successful adjustments which supported participants to continue working were often based on a good understanding of dementia, which for many came from attending a dementia-awareness session.

Something that we did notice that whenever he came to stairs he always seemed to hesitate and he was really concentrating and we weren't aware of that until the nurse came in and says no, he can't, he can't see straight lines … and the nurse gave us some hints and tips and how to do things (Paul's line manager, CS04, council officer)

This helped employers understand the specific difficulties their employee was facing and working together with the employee, and in some cases their families, they were able to develop well-placed and supportive adjustments. These adjustments focused on facilitating and retaining the skills the person with dementia had rather than focusing on what they could no longer do.

It was about looking at what she was capable of rather than looking at what she couldn't do. (Joan's line manager, CS12, head of business support)

A strong support network was important for all of the participants in the case studies, regardless of whether they continued or left work. Family members were an important source of support in all of the cases. They were important in the process of getting a diagnosis, often being the people who instigated the first trip to the general practitioner regarding changes they had noticed, and also communicating what adjustments might be required with the employers. Work colleagues were also an essential source of support. This included having close friends in the workplace, supportive colleagues and a good relationship with their line manager where they felt supported and understood.

I always made sure that if he needed help I would be there. I didn't want to be too over-compensating for him because he'd need to do it his self. (Paul's work colleague, CS04, council officer)

Support from family and work colleagues was integral to supporting the participants when they continued employment and to ensuring that the adjustments made worked well.

Theme 2: Work and wellbeing

This theme explores the impact of the employment situation on the physical, social and emotional wellbeing of the participants. The sub-themes discussed here are: managing symptoms better, staying connected and it was a relief to stop.

Managing symptoms better

Participants felt that employment provided challenges they would not have without working. This in turn fostered the belief that work was preserving their functioning or ability to manage their symptoms.

The more I do, the longer I'll keep some sort of good function there. (Joan, CS12, head of business support)

Other participants felt that the routine of working was beneficial for them, either in the routine of getting up and going to work each day or within the workplace following a set routine to carry out work tasks. Overall, the participants who continued working felt that, by doing so, it was helping them cope with their diagnosis and manage their symptoms. It is not clear from this information what is influencing the participants’ perception that work keeps them well, there may be many other factors involved which keeps them well enough to work, rather than work itself delivering the benefit. What this does show, nevertheless, is that the participants placed a value on being able to continue working.

Staying connected

For the seven participants who did continue working, although adapting to their diagnosis was difficult, it was viewed as a way of keeping connected with their social networks and allowing for some continuity in their lives at a time when many other things were changing.

What kept me going was, see the guys that I worked with, an absolutely fantastic group of guys, couldn't ask for better honestly and I think that's what really kept me going because even when I was off, the banter, I totally missed the banter. (Chris, CS09, engineer)

In contrast, participants who left work found it difficult to access age-appropriate services and, because so many of their social networks were linked to their workplace, leaving work had resulted in them losing contact with a lot of friends, especially for male participants. This had a negative effect on their social and psychological wellbeing, with many people feeling under-stimulated and isolated at home.

You feel quite remote you know because you've been taken out the work environment you know, meeting your mates every day and having a laugh and you know maybe have them for a beer at the weekends or something. I've lost track of my, they've moved away and I've lost track of my mates when I got diagnosed. (Michael, CS02, HGV driver)

This issue around feeling socially isolated particularly may link more widely to a loss of identity from leaving employment. For many participants, their identity was closely linked to their employment. The loss of work resulted in changes to the participants’ way of life and a period of adjustment.

I was babysitting for money when I was about 11; so I've been working since I was 11 but in paid work since I was 15. So it's a huge part of my life and you know that culture of work ethic and everything, so that took a bit of getting used not going to work. (Anna, CS07, nurse)

It was clear from the data that employment had a wider benefit to the participants in the study beyond financial remuneration. There were clear differences in outcome for the participants who continued employment and those who did not in terms of their social connections.

It was a relief to stop

It was clear that continued employment was not the best option for all of the participants. There was evidence that working was having a negative impact on participants’ wellbeing in three of the case studies, especially those who had a long delay to their diagnosis and little support in the workplace.

When she came in from her work she was stressed out every single day but when she stopped going to her work she was a lot better. (Myra's husband, CS15, office manager)

Participants reported increased stress as they attempted to continue performing in their job without support or understanding why they were struggling, and expressed relief at leaving work.

It was really the very understanding [line manager] and myself had a conversation about it and it was agreed that I would desist, that I would stop, though I have to confess it was a huge relief to me to be able to go ‘oh, enough is enough’. (John, CS01, lecturer)

In these situations, stopping work was the best option for the participants’ health and wellbeing. Performing poorly at work impacted on the participants’ confidence and they felt they were no longer able to continue. However, on reflection two of the three participants felt that with the correct support they could have continued working in some capacity.

Theme 3: Wider impact of dementia in the workplace

This theme examines the perspectives of the employer and the specific challenges that they faced when they were supporting a person with dementia in the workplace.

Doing the best we can

The employers who participated in the case studies expressed a desire to want to do the best they could to support their employees. This is in contrast to the proposition discussed previously that many participants felt they had left employment on bad terms, and that they could have been supported better. For most employers, they felt they had done the best they could by their employee and this involved showing compassion to their employees and treating them with respect, with pre-existing relationships at the centre of this.

Yeah, I'm your line manager, but then at the same time I'm more concerned about your own personal wellbeing and obviously in doing that I'll do my role as a manager, but also your friend. (John's line manager, CS01, lecturer)

It is important to note that an employer perspective was not included in all of the case studies. In these cases, employers either did not respond to invitations to participate or the participant themselves did not feel comfortable asking their employer to participate because of the circumstances surrounding them leaving employment. No employers had previous experience of supporting an employee with dementia so there was a feeling that they were learning as they went, revealing a lack of understanding of dementia, and importantly what the employee with dementia might be capable of. This inexperience was highlighted in a number of cases where, although the participant and/or family felt that the person could continue working in some capacity, there was a contrast with the employer's view that early retirement was the best option for the employee.

Do they want to offer her something else? Do they know the implications that are going to go with that? Is it easier for them to just to pension her off? (Myra's husband, CS15, office manager)

However, in the cases where the participants continued employment, the employers accessed support from existing disability management processes and dementia-awareness training which helped them discuss and implement appropriate adjustments. One example was the use of a health passport which is explained in the following quote:

[The health passport] is just an opportunity for him to be open and honest and tell me how work, how is his condition is affecting his work, so it can you know instigate a two-way conversation so if we need to make some adjustments then we can and at least I'm fully cognisant of his condition. (Jack's line manager, CS05, telephone engineer)

The majority of employers interviewed did not know where to access support external to their organisation, such as training or guidance on employment of a person with dementia.

I mean it would've been good if there had been some sort of expert there that you're able to pick up the phone and ask. (Jim's Human Resources representative, CS03, engineer)

These conflicting views between employers and workers of the optimal path for employees post-diagnosis may suggest a structural issue arising from power and other relations within the workplace but there was insufficient evidence or cases to reveal any systematic evidence to confirm or deny this speculation.

Protecting business needs

The employers also highlighted the challenges faced when trying to balance supporting their employee with dementia with running a successful business. At times maintaining the employee within the workforce had associated costs; for example, many participants acknowledged they were not performing at the same levels as they had before but, with the exception of one participant, their salary remained the same despite adjustments to job descriptions and working patterns. In many cases, the business absorbed these costs. It is of note that, in the majority of cases, employees who continued working were employed in a large organisation (over 250 employees). The exception to this was a small family business where the costs appeared to come secondary to the need to support their family member.

We didn't want to stop him doing it so we thought if we lose £20, £30, £100 what the hell does it matter you know, as long as he is keeping as, as, as much of his faculties going as he can but it, it's difficult you know ’cause your business head is saying you can't do this ’cause you're losing money here. (Ken's brother, CS11, shop owner)

When asked about preparing for the future or monitoring the person with dementia, very few of the line managers had thought about this. Again, this may reflect the lack of understanding of dementia and a support need for employers in the future.

I think I need to have that conversation with him just to say you know how, if, if there is a deterioration, whether it just be temporary or a gradual, how am I going to be best sort of informed. (Jack's line manager, CS05, telephone engineer)

This lack of forward planning may reflect a lack of understanding about the progressive nature of dementia, but may also be related to the fact that it is potentially a difficult situation for a line manager to confront so they were not comfortable talking about it.

Impact on colleagues

By extension, another issue that was highlighted within the case studies was the impact that having a colleague diagnosed with dementia had on co-workers. As well as experiencing increased workloads, there was an emotional impact on colleagues and line managers who worked with the participants. This included feelings of guilt over not spotting the signs of dementia in their colleague, worry about their own health as a result of learning about their colleague's diagnosis, and shock and sympathy for their colleague.

I would have liked to have thought that I was the one that recognised it you know. It's quite a complicated little thing when you, when you get into the, the different scenarios that could've transpired, did transpire etc. and how reflective you become and that after you look back you know. (John's line manager, CS01, lecturer)

There was also stress related to supporting a colleague with dementia, especially in the early stages pre-diagnosis when the problems were emerging and there was no understanding of what was causing the problem. At times this caused conflicts within the workplace, causing increased stress for the person with dementia, and those working with them.

It affected my mental health a bit because you do start to think ‘gosh, is it me’ and am I being unfair and am I doing, so it's horrendous for Myra and it's devastating for her family but it did have a big impact on everybody else. It has been really, really difficult. (Myra's line manager, CS15, office manager)

This shows the wide impact an employee being diagnosed with dementia can have in the workplace and highlights the need for support on some level for all the employees involved.

Discussion

The findings revealed that continued employment post-diagnosis of dementia is possible; however, this was not a common experience across all 16 case studies. There are a number of factors which need to be considered in supporting people with dementia with employment and this can be complex to manage. It was clear from the data that there were differences in the outcomes of those who continued working and those who left after diagnosis in terms of their overall wellbeing and support they received. This highlights the need for appropriate support for those diagnosed with dementia both to continue employment and to facilitate a supported exit from employment if necessary.

Employment-related support for people with dementia

This study has shown that, when well-supported, many people with dementia can continue working, and by continuing in a job they have done for many years they are retaining their skills and continuing to contribute economically and socially to society.

While there was evidence of the specific supports that were helpful in assisting people with dementia to continue working, there was no clear consensus. What was deemed appropriate support was linked to the type of employment, the symptoms the person experienced and the resources the company had to provide support. This highlights the need to have a person-centred approach to supporting continued employment, in line with the recommendations for post-diagnostic support (e.g. Scottish Government 2013).

Although the specific supports used varied, it appeared that employers who successfully facilitated their employee to continue working adopted a person-centred approach to assessing their needs and abilities, and drew on existing disability management policies in the absence of policies which specifically addressed dementia. Employers who take a proactive attitude towards health and disability in the workplace are commonly more successful in retaining their employees who experience health problems. In these organisations, timely workplace adjustments, guided by vocational rehabilitation advice, are most effective at supporting employees with health problems (Waddell, Burton and Kendall Reference Waddell, Burton and Kendall2008). Such actions might be expected where there was a high degree of occupational and enterprise-specific skills pre-diagnosis, as the embodiment of these within the employee could well represent significant human capital investment and continuing value to the employer (Doeringer and Piore Reference Doeringer and Piore1985; Pollert Reference Pollert1988). This approach appeared to be successful in a number of the case studies where organisations supported their employee to continue working, with the focus very much on what they can still do, rather than what they cannot.

Workplace education and dementia-awareness sessions were found to be useful to those organisations which did promote continued employment by supporting colleagues to understand the abilities, challenges and how best to support their co-worker. While no previous research has evaluated the usefulness of workplace dementia-awareness sessions, there is growing evidence for the positive outcome associated with mental health education in the workplace (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Koehn, White, Harder, Schultz, Williams-Whitt, Warje, Dionne, Koehoorn and Pasca2016).

Nevertheless, in some occupations continued employment in the same work was not possible for health and safety reasons; for example, the HGV driver could no longer drive and the nurse recognised it was not safe for her to continue practising. It was also clear from the findings that delays in the diagnosis process proved a barrier for continuing employment for many. The challenges of getting a timely diagnosis of dementia have been widely reported (e.g. Hayo Reference Hayo2015; Johannessen and Möller Reference Johannessen and Möller2011; Mendez Reference Mendez2006). However, for an individual who is still in work, this can be crucial to whether continued employment is possible. The UK Equality Act (UK Government 2010) prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities. Yet, without a diagnosis of dementia, individuals may not be able to benefit from the provision of the Act. The findings revealed just that: the longer it took to get a diagnosis, the more likely it was that the individual had left work or gone on sick leave due to the increased stress and pressure of trying to cope with the symptoms experienced without the appropriate support. Similar to the findings of the Ohman, Nygard and Borell (Reference Ohman, Nygard and Borell2001) study, after receiving a diagnosis, it was more likely that this triggered the process of early retirement rather than returning to work with support.

The majority of the participants who left, including the two people on sick leave, felt they would have been able to continue working in some capacity but did not have the opportunity. Previous research has shown that younger people with dementia often face challenges in how other people view their abilities and they can be thought of as unable to continue with their normal activities (Clemerson, Walsh and Isaac Reference Clemerson, Walsh and Isaac2014). In the present study, when employers were not fully aware of the capabilities of the person with dementia and the supports available to them, then facilitating continued employment was not considered.

Although the employers’ perspective was to balance a desire to do the best for their employees with the needs of the business, it was clear that a lack of knowledge and experience with dementia for the employers meant that the opportunity for continued employment was not always considered fully. Large organisations with the internal resources and developed disability management policies appeared to adapt to supporting an employee with dementia by adopting a general disability management approach, focused on the abilities the person retained. There is little research evidence on how small and medium-sized enterprises support employees with health problems and disabilities, highlighting the need for more support and external services which can be accessed by these organisations (Waddell, Burton and Kendall Reference Waddell, Burton and Kendall2008).

Leaving employment had a wider impact on the psychological, social and emotional wellbeing of the participants. Those participants who felt they had no control over leaving work, either because their illness meant that it was not possible to continue and no support was offered or because they felt pushed out by their employers, were more likely to have financial problems and have fewer activities and social arrangements organised for their retirement. Previous research has indicated that having control over the decision to retire is important for wellbeing in retirement. If retirement is perceived to be forced, either due to reaching statutory retirement age or through ill health, there is a negative impact on wellbeing (Hershey and Henkins Reference Hershey and Henkens2014). Although the aim of this research was to investigate the potential for continued employment, it has highlighted that continued employment is not possible or appropriate for every individual with dementia and appropriate support for leaving work and adjusting to retirement is just as important as supporting continued employment post-diagnosis.

Theoretical implications

There were clear benefits to the participants and their families in this study of continuing employment. Much of this related to the idea that employment provided a challenge, a way of staying connected and of feelings of doing something useful and worthwhile. For many of the participants, continuing employment helped them to address the stereotype of dementia being associated with older age, therefore reducing the stigma they experienced. However, other participants did experience stigma which left them feeling isolated and this had a negative impact on their wellbeing. It is clear from the data presented here that how the participants responded to stigma was important for their continued wellbeing. Goffman (Reference Goffman1963), in his book Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, states that withdrawing from society is a common way of dealing with stigma, but can lead to isolation, anxiety and depression. This was evident in some cases where losing employment compounded their spoiled identity, becoming further stigmatized by leaving the labour market. The participants’ response in these situations was to withdraw from their previous social lives and activities, which had a further negative impact on overall wellbeing.

Other responses to stigma listed by Goffman include using it as a learning experience, highlighting other skills and abilities to compensate, or joining self-help groups and clubs to foster a sense of belonging (Goffman Reference Goffman1963). The case study examples supported this also, where participants stayed engaged within their community either through continued employment or volunteering. In these instances, there were clear benefits to the participants, both in terms of their feelings about their diagnosis, and for their wellbeing. For many, although their employers felt they were doing the best they could for the individual after their diagnosis, stigma of dementia may explain why the option of redeployment was not considered as an option for continuing employment. This may stem from a lack of understanding of dementia within the general population, which needs to be addressed to create an enabling environment for continued employment.

Where this research may be important is by challenging the public perceptions of dementia. People with dementia are commonly labelled and stereotyped negatively which does not accurately portray the experience of dementia (Swaffer Reference Swaffer2014). However, by continuing employment, the participants in this study have demonstrated that they are still able to make a contribution to work and to society, and by doing so they are addressing the stereotypes of dementia and showing that people with dementia can continue to live well post-diagnosis.

Policy implications

This analysis links to current policy promoting the ‘living well with dementia’ agenda (e.g. Scottish Government 2013). The findings highlight some of the issues surrounding employment for people with dementia which have not previously been considered in policy documentation. Future policy revisions should be cognisant of this to ensure that practitioners are aware of the implications of maintaining employment for a person with dementia and that the appropriate person-centred support plan is developed should the individual with dementia wish to continue working. This will become all the more important in coming years as policies relating to increased retirement age are implemented with the potential of more people developing dementia while still in the workforce. Moreover, the World Alzheimer Report 2016 makes a strong call to improve health care for people with dementia (Alzheimer's Disease International 2016). Reflecting on the results presented here, it is argued that for people with early onset dementia especially, this should include improved occupational health provision.

Similarly, it is not just dementia-focused policy which needs to address the issues raised in this article; government initiatives, such as the recent UK Government publication Fuller Working Lives (Department of Work and Pensions 2014), should address the wider implications of supporting an employee with age-related disorders in the workplace and ensure employers are equipped to support and identify employees who develop dementia whilst still in work. Strategies such as ‘dementia friends’ and ‘dementia-friendly communities’ (Alzheimer's Society 2015b, 2016) go some way to increasing awareness of dementia within the community and businesses; however, similar education and awareness-raising initiatives targeting employers may be useful.

Strengths and limitations

Previous studies which report on the employment of people with dementia have not focused on the support required to continue working, instead prioritising first symptoms and problems experienced and the process of leaving work (Chaplin and Davidson Reference Chaplin and Davidson2016; Ohman, Nygard and Borell Reference Ohman, Nygard and Borell2001). A key strength of this research is the case study design which gathered data from differing perspectives on the same situation. This approach allowed for fuller understanding of each situation, acknowledging that a person being diagnosed with dementia will also have an impact on the people close to them. However, it is limited by a workplace representative not being included in every case study. There were a variety of reasons for this, including the person with dementia having no contact with their previous workplace, and there were challenges in some cases trying to engage with workplace participants with busy work schedules. The researchers are aware that the experiences uncovered within this study are unique to the participants in the case studies and make no claims of generalisation. However, the strength of this research has been to establish that issues surrounding employment for people with dementia are an important and timely area of research. The depth and quality of information gathered in each case study is testament to the willingness of participants to share their experiences. Further investigation of the issues needs to be carried out, including developing a deeper understanding of the factors which support continued employment, as well as how employment and exit from employment may be managed as the disease progresses.

Ethical issues

Given the sensitivity of the topic of discussion, a number of ethical considerations needed to be addressed from the outset of the study. It was unclear how willing people would be to discuss their experiences, and especially to facilitate access to a workplace representative. If the person with dementia was still in employment, allowing a researcher access to the workplace would mean that, firstly, they would have to disclose their diagnosis but, secondly, it could potentially highlight problems in their performance or the researcher could become privy to information about their employment that they were not aware of, such as their manager disclosing that their employment would be terminated. In order to safeguard against the potentiality of disclosing sensitive information between the case study participants, the procedure stated that workplace interviews were only conducted once all contact with the participant and their family was concluded. Additionally, safeguards were needed to manage the distress which could potentially be caused by discussing the sensitive topics of getting diagnosed, employment (or loss of), and the impact on family and finances, both for the researchers and the participants in the form of debriefing and signposting to services if required. Despite the complex ethical issues which had to be addressed, this study demonstrated that, in the correct and supported circumstances, it is possible to engage people with dementia and their families in topics which are of a sensitive nature.

Conclusion

This study is the first to reveal the profound impact that employment-related issues have on the lives of people with dementia. It is clear that continued employment post-diagnosis can be beneficial for people with dementia; however, this may be complex to support. Incorporating the views of people with dementia, their family members and workplace representatives within the case studies provided a rich description of each unique situation. The implications of this research are wide ranging, and these findings have the potential to influence future policy and practice relating to the employment of people with dementia post-diagnosis. Practitioners involved in diagnosis and post-diagnostic support, employers and employment support organisations need to be aware of the potential for continued employment in order to ensure that appropriate support is available to facilitate both continued employment and the process of leaving employment. Given the current policy environment, this research is timely in realising the potential impact an ageing workforce may have on society. From a theoretical perspective, supporting continued employment may be protective to an individual's identity and challenge the stigma associated with dementia. The increasing casualisation and flexibility of the labour market means that, for many, loss of a long-term position can mean enforced exclusion and isolation from employment and income. Retention with their existing employer can help to avoid some of the negative impacts of the onset of dementia, as this research has revealed; for others in the peripheral labour market or in self-employment, society needs to develop different means of support for those where working is still possible and promotes wellbeing. Further research is required to understand fully the problems relating to the employment of people with dementia. In particular, research is required to strengthen the evidence for workplace supports identified in this study and to understand how an employee can be supported over time in the workplace as their dementia progresses.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by an Alzheimer's Society Research Grant (Number 180, PG-2012-199). The authors wish to thank the Alzheimer's Society for their funding and support for the project. The authors are grateful to the interviewees for their time and participation in the project and for their permission to publish extracts from the interviews. The authors report no conflicts of interest.