Introduction

Recent shifts in political support to populist parties worldwide have been linked to the changing policy preferences of so-called “left behind communities” (Goldstone and Diamond Reference Goldstone and Diamond2020). Goodwin and Heath (Reference Goodwin and Heath2016b) define the “left behind” demographic as working class, socially excluded, lacking in educational attainment, and ethnically white. Membership in this group has been shown to correlate with support for populist radical right parties (Arzheimer and Berning Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019). Studies have paid specific attention to how left behind voters comprised a primary part of the “Leave” coalition in the run-up to the United Kingdom’s 2016 referendum on European Union membership (Goodwin and Heath Reference Goodwin and Heath2016a; Reference Goodwin and Heath2016b) and Donald Trump’s electoral coalition in the 2016 United States Presidential election (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

What do left behind voters want, in terms of public policy change? What do they view as legitimate public policy? In survey research, these communities have been found to have anxiety about levels of migration and demand investment in public services, particularly health care (Becker, Fetzer, and Novy Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2017; Hameleers and Schmuck Reference Hameleers and Schmuck2017). Prominent commentators have argued that they support tightening immigration rules and increasing financial investment in their areas (Goodhart Reference Goodhart2017). However, what the left behind “want”—in terms of policy preferences—remains unclear. Recent survey research on policy preferences for Brexit has proved inconclusive (Hobolt, Tilley, and Leeper Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Leeper2022). Moreover, existing studies have been criticized for treating the left behind as a simplistic category because they ignore the methodological challenges of assessing their policy preferences (Bhambra Reference Bhambra2017). This article addresses the following research question: what are the preferences of left behind communities for policy change processes related to populist politics? In doing so, it addresses two challenges: emotional attachment and social stigmatization.

First, quantitative research has shown that the preferences of partisan political groups are difficult to assess due to emotional attachment. Survey research has shown the importance of “affective polarization,” defined as “emotional attachment to in-group partisans and hostility towards out-group partisans” (Dias and Lelkes Reference Dias and Lelkes2021; Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021, 1477). Affective polarization has been demonstrated to shape emotional attachment to Leave and Remain identities forged during the Brexit referendum (Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021). Such attachments generate psychological states like vicarious cognitive dissonance, which poses numerous challenges in preference measurement (Sorace and Hobolt Reference Sorace and Hobolt2021). For example, state-of-the-art conjoint survey experiment research on Brexit preferences finds that “neither [Leave or Remain partisan] side considered any of the available policy outcomes as adequately respecting the vote” (Hobolt, Tilley, and Leeper Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Leeper2022, 841). Such findings suggest the need to complement experimental research on preferences with qualitative work. Conjoint experimental research “forces” respondents to choose between preselected outcomes, which is “at odds with the descriptive logic of preference-related questions” (Ganter Reference Ganter2021, 2). Rich descriptive data may thus provide an important addition to experimental evidence.

Second, left behind communities are “hard to survey” in the sense of living in places that are stigmatized for poor economic and educational outcomes, creating problems with social desirability bias (Tourangeau et al. Reference Tourangeau, Edwards, Johnson, Walter and Bates2014). Publicly used labels like left behind produce social stigma, which generates mistrust of authority and isolating behaviors (Ellard-Gray et al. Reference Ellard-Gray, Jeffrey, Chobak and Crann2015). Stigmatized individuals are likely to be hard to persuade to be involved in research and hard to interview due to being labeled and associated feelings of negative stereotyping (Tourangeau et al. Reference Tourangeau, Edwards, Johnson, Walter and Bates2014). The stigma of being part of a community defined as left behind in public debate is also likely to make individuals harder to contact for these reasons. Obstacles to research with stigmatized populations have led scholars to advocate innovative methodological techniques, using nonprobability sampling and creative recruitment techniques (Ellard-Gray et al. Reference Ellard-Gray, Jeffrey, Chobak and Crann2015).

As a response to the above limitations, this article presents qualitative research into the policy preferences of left behind communities, using the UK during the implementation of Brexit in 2019 as an empirical field site. This approach addresses methodological difficulties associated with researching emotionally charged policy issues in stigmatized populations by using photo elicitation. Photo elicitation—a method uncommon in political science—is designed to surface the emotions of research subjects who are treated as participants in the research through engaging them in open-ended observational interviews in public spaces. Participants consider a photograph of a contentious issue and clarify their preferences in dialogue with researchers following reflection. The process of reaction and reflection allows participants to process emotions they have related to the subject (perhaps whether they voted to Leave or Remain) and express their preference in light of this reflection. When deployed in interviews involving direct observation and participant engagement, photo elicitation can uncover how participants describe their preferences on socially contentious issues, accounting for their complex feelings (Harper Reference Harper2002). The open-ended nature of photo elicitation interviews also avoids social pressures associated with stigmatized identities, enabling interviewees to respond in any way they choose (Ellard-Gray et al. Reference Ellard-Gray, Jeffrey, Chobak and Crann2015).

We conducted 418 interviews in five UK field sites, providing extensive qualitative data on post-Brexit preferences within left behind communities. We focused on the infamous claim that left behind communities voted for Brexit to improve investment in the National Health Service (NHS), a claim that was made and perpetuated by the “Leave” campaign advert: “We send the EU £350 million a week. Let’s fund our NHS instead.” The claim, despite being legally and financially false, was widely touted as a persuasive appeal to left behind communities’ positive attitudes toward the NHS (see Figure attached in Appendix).

The data show that research participants reacted negatively to the photo, using it to indicate distrust of politics and politicians. This distancing reaction allowed them to indicate how they view Brexit and health care as unrelated, despite the Leave campaign claims. Participants indicated ambitious policy preferences for investment in health care independently of Brexit. Participants were less clear about which sectors should be responsible for providing this investment (public, private, or voluntary sectors). However, we did not find that participants were using health care investment as a proxy for a policy preference of reducing immigration. These findings, we suggest, indicate that assumptions of a link between demands for state investment in health care and support for populist causes like Brexit within places labeled as left behind may be mistaken. We interpret the utility of photo elicitation as a method for enabling “positive marginality” in participants (Unger Reference Unger2000). Interviewees are able to reflect on the photo at length, reject the logic of elite policy prescriptions, and begin to articulate positive alternative preferences from their personal experiences of health care.

This article proceeds in four sections. First, we highlight how existing research characterizes the views and opinions of the left behind on Brexit and identify potential methodological shortcomings that have generated contestation over who the left behind are and what they want from Brexit. Second, we detail our innovative methodological approach and justify our decisions in terms of the timing, placement, and ethical approach to data collection in our fieldwork. Third, we detail our findings, linking together the six main themes collated in our fieldwork. Fourth, we discuss the implications of this research, the limitations of our approach, and the value of photo elicitation in accessing the policy preferences of stigmatized social groups.

What do Left Behind Communities Really Want?

Left behind communities have been identified as important political constituencies whose shifting policy demands influenced surprising electoral outcomes in the 2010s and volatility in democracy worldwide (Goldstone and Diamond Reference Goldstone and Diamond2020). Watson (Reference Watson2018, 28) notes “those who are deemed to belong to the left behind have been most readily identified as the constituency that tipped the scales in favor of the Leave camp” in the UK’s 2016 vote to Leave the European Union. Left behind constituencies have been conceptualized to include “low-skilled and less well-educated blue-collar workers and citizens who have been pushed to the margins not only by the economic transformation of [their] country over recent decades but also by the values that have come to dominate a more socially liberal media and political class” (Goodwin and Heath Reference Goodwin and Heath2016a, 331). Those classed as left behind are therefore marginalized both economically and culturally, and this marginalization, it is suggested, drives reactionary political beliefs.

Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) capture the possible policy preferences of the left behind through their “cultural backlash” thesis (cf. Schäfer Reference Schäfer2021). Long-term structural changes in gender equality, urban growth, and education, as well as increasing racial diversity, combine with period effects such as job losses in traditional manufacturing industries, migrant flows, economic instability, and terrorist atrocities to create a “backlash” (see also Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020). “Traditional social conservatives,” they suggest, “are clustered disproportionately in declining … communities based on manufacturing and agriculture” (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019, 45). Feeling they are left behind in the margins of society—geographically, economically, culturally—these individuals may become hardened in their beliefs due to a combination of threat perceptions, grievance at being economically marginalized, and elite and media framing by populist actors (McKay Reference McKay2019). These processes produce staunch authoritarian beliefs in a “strong” state and nationalistic opposition to immigration, combined with public investment in infrastructure, to counter “liberal” cultural values and economic globalization (Magni Reference Magni2020). Economic and cultural factors therefore combine to produce this backlash (Carreras, Carreras, and Bowler Reference Carreras, Carreras and Bowler2019), as left behind voters feel they have “nothing left to lose” in voting for more radical political options and against established parties (Demeter and Goyanes Reference Demeter and Goyanes2020).

This international trend is reflected in the UK (Sobolewska and Ford Reference Sobolewska and Ford2020). Panel survey research from the National Centre for Social Research in May and September 2016 found a close link between left behind demographic characteristics and propensity to vote Leave including low educational qualifications, income less than £1,200 per month, and living in social housing. Moreover, the study found the Leave vote closely associated with those struggling financially, believing Britain is “getting worse,” and perceiving themselves as working class (Swales Reference Swales2016, 7). Commentators have used similar statistics to make the case for economically progressive, yet socially conservative, policy agendas (Goodhart Reference Goodhart2017). Members of left behind communities, it is argued, interpret Brexit as representing demands for investment in their communities and reducing inward migration (Goodwin and Milazzo Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2017, 462). Such demands are linked attitudinally to evaluations of the NHS: “In regions where the share of suspected cancer patients waiting for treatment for less than 62 days is larger, the Vote Leave share is lower. By symmetry, where waiting times are longer, Vote Leave gains” (Becker, Fetzer, and Novy Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2017, 627). Clarke, Goodwin, and Whiteley (Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017, 83) show that, although negative attitudes toward immigration provided strong predictors of negative attitudes toward the EU, negative attitudes toward the NHS also predicted hostility toward the EU, albeit less strongly. Experimental survey research suggests campaign messages demanding action on anti-EU themes can “hold in place” Euroskeptic attitudes, crowding out pro-EU messaging (Goodwin, Hix, and Pickup Reference Goodwin, Hix and Pickup2018), thus firming up links between attitudes and Leave votes.

This quantitative research implies left behind groups’ policy preferences converge around a basic logic advocating (1) reducing immigration so as to (2) increase access to public goods, particularly health and specifically (in the UK) the NHS. However, an important limitation of this research is the use of attitudinal survey data as a proxy for policy preferences for a demographic that can be characterized as hard to survey (Tourangeau et al. Reference Tourangeau, Edwards, Johnson, Walter and Bates2014). Hard-to-survey groups are diverse but are commonly the subject of negative social stereotypes—or stigma—analyzed by the eminent sociologist Erving Goffman ([1963] Reference Goffman1990). Stigmatization can be defined as a process in which particular groups and individuals develop stigma as they are “subjected to shame, scorn, ridicule, or discrimination in their interactions with others” (Berry and Gunn Reference Berry, Gunn, Tourangeau, Edwards, Johnson, Wolter and Bates2014, 368). Stigmatization involves actors in a privileged position claiming a group or individual has an unexpected trait marking them as socially “abnormal.” As Goffman states,

While the stranger is before us, evidence can arise of his possessing an attribute that makes him different from others in the category of persons available for him to be, and of a less desirable kind. … He is thus reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one. ([1963] Reference Goffman1990, 12)

In the US and UK, left behind communities are situated in places that have been stigmatized by the media, legislators, and other elite actors as having voted for Brexit and Donald Trump because those voting outcomes “upend” popular preconceptions of how places characterized by high unemployment and poor educational outcomes ought to vote—namely, for progressive political parties or policy options supported by progressive parties, such as membership in the EU (McKenzie Reference Mckenzie2017a). In the UK, the Brexit vote led residents of postindustrial places to be stigmatized as “stupid, backward, old, anti-modern, parochial and xenophobic” (Browning Reference Browning2019, 236–7). Prominent media outlets launched investigations into how these places are at risk from right-wing extremism (Townsend Reference Townsend2021). White working-class groups in these places are labeled in legislative inquiries as “forgotten” (House of Commons Education Committee 2021) and named “The Left Behind” in mainstream television docudramas (Glynn Reference Glynn2019).

Labeling communities in this way stigmatizes them by, first, obscuring their real characteristics. Bhambra (Reference Bhambra2017) highlights that left behind places are in fact racially diverse and that white people in these places have a socially privileged majority position compared with ethnic minority groups. Second, stigmatization imposes a negative image on those places as abnormal that implies assumptions about the policy preferences of individual residents. Both effects heighten the methodological problem of “social desirability bias.” Respondents may anticipate shame or discrimination by their town’s association with the left behind label and hesitate or lack confidence in articulating policy preferences (Bell and Bishai Reference Bell and Bishai2021).

To address the methodological problem of stigmatization, it is crucial to pay closer attention to nuances in research subjects’ responses and behaviors and what may be driving them. Qualitative research accounts more directly for these methodological problems by providing close observation on the preferences of communities living in left behind places through sustained ethnographic research (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Eribon Reference Eribon and Lucey2013; Gest Reference Gest2016; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016; McKenzie Reference Mckenzie2017a; Reference Mckenzie2017b; Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2019). This research shows how economic and cultural factors are mediated by conditions of social integration that influence support for the populist right and left (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020). A lack of social integration refers to subjective feelings of isolation and marginalization or low social status. Low social integration is associated with a lack of access to social goods associated with high social standing such as a clean environment, social security, and secure health care. Lack of social integration produces feelings of nostalgia for lost social benefits, but also distrust of elite authority (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020). In the US, Hochschild (Reference Hochschild2016) shows how communities in a deprived part of Louisiana support the right-wing populist Tea Party despite their economic deprivation and reliance on state support. Through life interviews and observation, she explains this “Great Paradox” by exploring how members of the community long for a clean environment and treatment for chronic illnesses they experience because of illegal levels of industrial pollution but simultaneously distrust elite “state” actors to improve these conditions. Right-wing Tea Party politicians capitalize on their distrust and nostalgia to influence their rejection of state support. Similar US-based studies focus on rural communities as left behind, highlighting a culture of “self-reliance,” which exacerbates unmet health needs (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2019).

In the UK, left behind places are less geographically isolated than are their US counterparts, but they similarly face social integration problems stemming from poor access to the welfare state (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow2019). McKenzie’s (Reference Mckenzie2017a; Reference Mckenzie2017b) ethnographic research in East London and Nottinghamshire is important for understanding the UK case. McKenzie (Reference Mckenzie2017a, 201) uncovers how “similarities in their reasoning around the referendum was overwhelming despite their different geographies and varied community identities.” Because of shared anger at their working-class positions and associated injustices, “Pro-Remain discourses simply made no sense to them as they were fundamentally dissociated from such reasoning on any economic, political or emotional level” (Reference Mckenzie2017a, 201, italics added; see also Agnisola, Weir, and Johnson Reference Agnisola, Weir and Johnson2019). McKenzie found the women she interacted with in particular “prioritized the politics that directly affected them and their families, such as the lack of housing, the shortage of places in local schools and the inadequacies of local health service provision” (Reference Mckenzie2017a, 204).

This article shares with these qualitative studies the spirit of James C. Scott’s insight: “You can’t explain human behavior behind the backs of the people who are being explained” (quoted in Wedeen Reference Wedeen2010, 259). However, whereas ethnographic work reveals the deep “habitus” of communities that voted Leave or backed Trump, we focus on addressing the methodological challenges of capturing policy preferences given the heightened stigmatization of these places. We define left behind communities as residents of places that are stigmatized by elite actors as harboring support for populist views due to those places having multiple forms of deprivation and a lack of educational attainment. Crucial to this definition is that left behind communities do not need to have voted for populist causes, nor do they need to satisfy the demographic criteria of “white working class” attributed by other studies. Rather, the definition highlights the stigmatization of place and points to the need for methodological innovation to address the effects of this stigmatization to gain rich data on residents’ policy preferences related to Brexit.

Research Methodology: Photo Elicitation

Our methodology answers the research question: what are the preferences of left behind communities for policy change processes related to populist politics? The policy change process we selected was the UK’s exit from the European Union (Brexit). The research methodology assumes, first, the need to collect thick descriptive data on policy preferences, and that a qualitative methodology is best suited to this task. Qualitative methodology provides the rich nuance of description of individual preferences that quantitative methodology does not capture. Second, for the communities in question, policy preferences may be emotionally entangled with populist figures and political campaigns (in this case, the Leave campaign for Brexit). The qualitative approach should therefore allow research participants to process any emotional entanglements with the populist campaign during the research. Third, left behind communities are not an objective category, but rather public discourse in Anglo-American countries stigmatizes them as being left behind for being associated with populist causes that go against normal progressive political preferences. The qualitative approach should be sensitive to issues of research participant engagement and recruitment that arise from the negative psychological consequences of stigmatization, including expectations of rejection and discrimination, which heightens respondent hesitancy (Frost Reference Frost2011).

We carefully considered how to allow participants to reflect on emotional entanglement with Brexit as a subject and, specifically, the Leave campaign. We also considered how to recruit and interview people with respect for the stigmatization of left behind places. We chose to use the methodological technique of photo elicitation to achieve these goals. Visual photo elicitation, a “soft” experimental method often used in qualitative studies of traumatic events (Lorenz Reference Lorenz2011), is useful for researching participant understandings of emotionally contentious issues. The “subtle function of graphic imagery,” exercises a compelling effect upon the informant, prodding latent memory, “to stimulate and release emotional statements” (Collier Reference Collier1957, 858, quoted in Harper Reference Harper2002). Compared with other methods seeking to minimize the emotional pull of a topic, for example semistructured interviews, photo elicitation seeks to bring emotive topics to the surface, prompting the participant to clarify what imperceptible, often suppressed feelings mean to them. Photo elicitation is often used for personal or autobiographical research using photos taken by participants, but, using photos with popular connotations, it can also be used for broader contentious issues about which participants may be uncomfortable speaking. Showing the participant an image related to the issue “connect[s] an individual to experiences or eras even if the images do not reflect the research subject’s actual lives” (Harper Reference Harper2002, 13). Therefore, our research design reveals the kind of emotive desires and preferences that some qualitative methods usually find more difficult to access. This is because such methods usually require considered reflection from the participant, whereas we recorded conversational reactions provoked by photo elicitation. Photo elicitation maximizes the confirmability of data on emotive topics by directing participants toward engaging their emotional understanding. It also deals with social desirability bias head-on; the presentation of a photo allows the participant to consider a stigmatized issue as an object rather than them being asked questions directly about that issue.

The Interviews

After they agreed to participate in a research project “about the NHS” via a street intercept recruitment method (see below), we offered participants the option to sit down at a table and showed them a photograph of the Brexit campaign bus with its implied promise to invest £350 million in the NHS (see Appendix). We chose this image as a symbol of the logic behind the (allegedly) legitimating narrative through which left behind communities support Brexit (both in the referendum and subsequent process of withdrawal). Photo elicitation uses symbols with relevant, but open-ended, meaning in relation to the topic to expand interview conversations to reflect on their emotional reactions (Harper Reference Harper2002). The image is a campaign slogan from the official Leave campaign that makes an explicit causal link between the process of leaving the EU and the (purported) outcome of doing so, with reference to public health care investment. Importantly, the slogan is not a personalized campaign promise because it does not make reference to a single politician or party. The slogan thus elicits a response at a conceptual level (the concept and logic of leaving and transition linked to the bus and the concept and logic of health investment linked to the monetary figure) that we could tap into by showing them the picture. Moreover, empirically, the picture did not have a “sell by date” at the time of the fieldwork because the leaving process was still ongoing and was uncertain in its outcome, so the image retained social and political relevance. Indeed, a statement by Prime Minister Theresa May in 2018 that she was committed to fulfilling the “funding pledge,” even though she herself backed Remain during the referendum (The Irish Times 2018), and polling data from October 2018 showing that 42% of the UK public and 61% of Leave voters “believed” the statement to be true (Stone Reference Stone2018), are testament to its enduring symbolic meaning.

To tap into this logic, but aware of the potential stigma attached to the Brexit topic, we asked participants generally what “comes to mind.” Based on their response, we sought to direct the conversation according to a framework that is intended to access participants’ understandings of legitimate post-Brexit health governance, thus getting them to describe their policy preferences in a loosely structured manner. This framework was adapted in each setting to local circumstances (Gest Reference Gest2016). Based upon the initial response of the participant—whether they highlighted Brexit, health, or didn’t recognize/understand the image—we asked further questions seeking to nudge the conversation toward expressing an understanding of legitimacy grounded in who a participant saw as being principally responsible or accountable for Brexit, health care, and the NHS.

Our guiding rule in each interview was to encourage participants to express their understanding as fully as possible, again with awareness of potential stigma. We chose to adopt body language and a conversation style to “positively reinforce” participants’ line of thinking and encourage their “authentic” expression (“nondescript fieldwork clothes,” Cramer Reference Cramer2016, 27, relaxed casual demeanor, nodding, mirroring their mood, maintaining eye contact, laughing, asking ‘follow on’ questions). Our approach has the downside of being open to charges of “question bias” from a behavioral perspective. However, it has the advantage from a qualitative perspective of enabling positive engagement with our research participants such that we can claim to have elicited their emotionally informed understandings as well as accounting for methodological biases related to stigmatization (Cramer Reference Cramer2016, 29).

Interpreting Policy Preferences

Policy preferences were accessed by nudging participants to describe their ideas of responsibility and accountability for the policy promise shown in the photo. Focusing on responsibility and accountability in our interviews provided a way to understand the umbrella concept of legitimacy through which we inferred participants’ policy preferences (Schmidt and Wood Reference Schmidt and Wood2019), but we did not posit a preestablished definition of any terms we expected participants to use or a set of policy options. The framework was applied in a flexible manner because the goal of photo elicitation is to facilitate participants expressing their emotionally informed understandings. To ensure participants felt maximum freedom and safety in articulating their views, we did not record names, ask participants for demographic data, or record their responses on tape. Instead, we kept handwritten notes of all relevant information given by the participant, written immediately after each interview ended, and noted demographic data based on our perceptions of the participants and information they volunteered unprompted. Participants were given a “business card” as evidence of their participation with a participant ID and email they could contact for further information or to withdraw from the study (none did). We tested the method over two days in a deprived part of Sheffield, which led us to slightly alter how we implemented our working framework, nudging participants more indirectly toward the concepts of responsibility and accountability.

Participant Recruitment

Research on hard-to-reach groups that are likely to feel stigmatized must deal with challenges of participant recruitment. Good practice states the need to be visible within the physical communities of stigmatized groups to build trust (Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Büthe, Arjona, Arriola, Bellin, Bennett and Björkman2021). To achieve this, we used a street intercept recruitment method in four weeks of fieldwork across four sites, plus a two day pilot. Street intercept recruitment involves nonprobabilistic sampling, but researchers conducting this type of work “favour … street-intercept … over other methods because of the better access to otherwise underrepresented groups” (Buschmann Reference Buschmann2019, 859). To carry out this approach, we had to be transparent; participants had to be made aware, first, that we were conducting political research on the relationship between health care and Brexit. Therefore, we rejected the option of seeking to become participant observers in the communities we were studying, instead clearly identifying ourselves as University staff to research participants at street level. We chose to conduct the research in public spaces easily visible within communities, specifically malls and shopping precincts. This choice had the downside that participants might view us with suspicion as clear “outsiders” from the community (Cramer Reference Cramer2016, 34). However, the upside is that we were able to present the research more honestly and often engage participants in discussing our outsider status. Revealing our outsider status through University logos was thus an attempt at providing an “entry point” for potentially stigmatized participants to engage us as “human beings” (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016;).

Fieldwork

We conducted photo elicitation in four field sites and one two-day pilot in Sheffield. Field sites were selected to encompass stigmatized left behind places with a history of association with radical right-wing populist and nationalist politics. We chose two sites in Northern Ireland (Newry, Mourne and Down and Derry City and Strabane) and Northern England (Rotherham and Rochdale). We could have chosen sites in Scotland, which has a number of communities with relevant demographic profiles, but they are associated with more progressive nationalist politics. Our research methodology also required strong local community links, which we did not have in Scotland. Table 1 summarizes the fieldwork locations.

Table 1. Districts and Boroughs Chosen as Field Sites and Indicators of Their LBC Status

Note: *Compiled from: Office of National Statistics (ONS), Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA), and Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI).**Wards classed as left behind in UK towns (OCSI 2019) and percentage of Super Output Areas (SOAs) in 100 most deprived in Northern Ireland (NISRA 2017, 8).

The four locations fall within the bounds of a “small-to-medium-sized” community, ranging from 75,000–300,000 residents (Cox and Longlands Reference Cox and Longlands2016, 6–7). All four areas can be classed as left behind communities based on the geographical presence of areas with high levels of multiple deprivations. In Newry, Mourne and Down and Derry City and Strabane, a high percentage of “Super Output Areas” (SOAs)—local socioeconomic units used in UK official statistical records—are listed in Northern Ireland’s 100 most deprived areas. Twenty-seven percent of SOAs in Derry and Strabane and 10% of Newry, Mourne and Down SOAs are listed, making them second and third only to Belfast. Both areas have a history of support for nationalist and radical right-wing political parties. Newry and Armagh parliamentary constituency elected the nationalist Sinn Féin party in 2017 and 2019, with the Euroskeptic right-wing Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) finishing second. The parliamentary constituency of Foyle, which encompasses Derry City and Strabane, elected a Sinn Féin Member of Parliament (MP) in 2017, and Sinn Féin and the DUP finished second and third behind the Social Democratic and Labour Party in 2015 and 2010.

Rochdale and Rotherham are more unequal in terms of the multiple deprivation index, with both towns also having prosperous suburban areas. Both Metropolitan Boroughs, however, have several wards explicitly classed as left behind (OCSI 2019). Deprivation is clustered around the center of the towns of Rochdale and Rotherham. Both towns have a history of support in national elections for the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and related nationalist parties. In Rochdale, UKIP finished second behind Labour in 2015, and UKIP’s successor, the Brexit Party, finished third in 2019. In Rotherham, UKIP finished second behind Labour in the 2015 general election and a 2012 by-election, and the Brexit Party finished third in 2019. In 2012 the radical right-wing British National Party finished third.

Last, our field sites are significantly affected by Brexit, both in general and in the specific area of health care. All four areas are highly reliant on EU structural funds (Rotherham and Rochdale) and/or access to an open border with the EU (Newry and Derry). They are also highly exposed to Brexit’s effects on health care. Given their high levels of multiple deprivations, all four sites have populations highly likely to be heavily reliant on the NHS and the local hospital with an Accident and Emergency department (see Appendix Table A). More detail on fieldwork protocols is available in the Appendix.

Reflexivity, Coding and Analysis

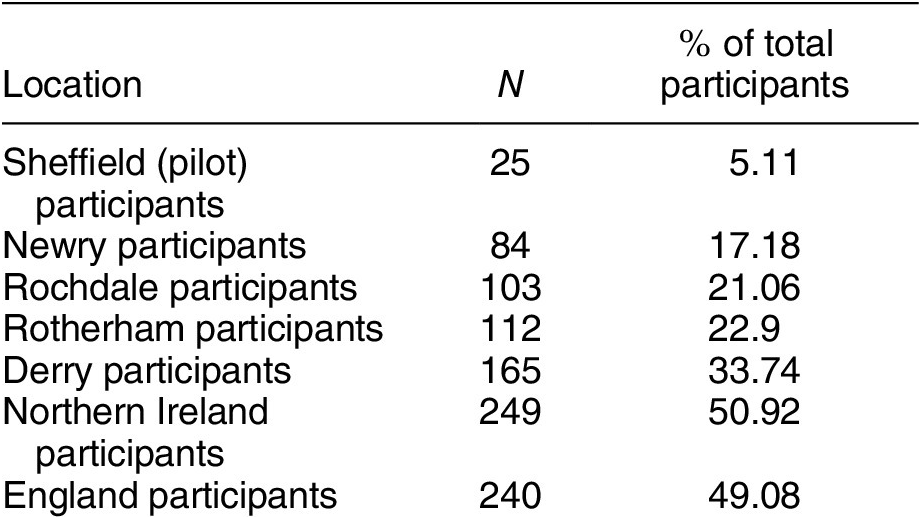

We conducted 418 interviews with a total of 489 participants. There was an even spread of participants across English and Northern Irish sites, with slightly fewer participants in Newry (first field site) and slightly more in Derry (last field site). We also conducted 22 pilot interviews over two days in Sheffield. Table 2, below, provides summary data on participants in each field site. The empirical analysis refers to percentages calculated for coded interviews rather than participants, as some interviews included more than one participant (for explanation see Appendix).

Table 2. Summary of Interview Participants

We generated an analytic coding framework inductively, by hand. We identified six themes including: the truth of the claim on the bus, distrust in politicians, responsibility, need for frontline NHS resources, link between NHS and Brexit, and anti-immigration sentiment. We coded each interview using color coding, in collaborative Google Drive documents. Here, we report findings from all six themes. We developed the analysis iteratively, consulting the literature, team members, and coded data. Each theme was further refined to produce the analysis below.

Analysis: “Brexit Means Brexit.” But What Does Brexit Mean?

Our analysis developed the initially coded themes into six analytical themes that use our data to explain how the left behind communities view a legitimate Brexit in the context of health governance. These themes are “lies, distrust, and ‘bullshit”’; “trustworthiness of politicians”; “responsibility”; “ambition for the NHS”; “disconnection between the NHS and Brexit”; and “immigration.” We generated descriptive statistical data based on the collaborative coding to summarize each theme (see Appendix).

This section argues that the photo elicitation method enabled participants to distance themselves from formal politics and begin to independently articulate policy preferences for health care investment, justified using their own personal experiences. We explain these responses using the concept of positive marginality (Unger Reference Unger2000). Positive marginality refers to the cognitive process through which stigmatized groups can reinterpret stigma positively by rejecting the logic of elite policy positions (emphasizing their “marginality”) and then beginning to articulate distinct policy preferences through their own personal experiences of the policy issue—in this case, health.

Lies, Distrust and “Bullshit”

Our first theme relates to antipolitical sentiment, distrust of politicians, and the narrative of “bullshit.” Existing literature argues that left behind communities support Brexit out of distrust in elites who advocated remaining in the EU (Evans and Menon Reference Evans and Menon2017), but we found more skeptical reactions to the Leave campaign than this literature would suggest. Specifically, we found a range of participants reacted to the photo immediately upon seeing it by pointing at the picture and stating bluntly “lies” and “bullshit.” This runs counter to the Brexit literature’s focus on left behind communities supporting Leave as a backlash against elite Remainer institutions.

The majority of our participants (in 59% of interviews) reacted explicitly to the claim on the bus. Of these participants, 30% reacted by immediately identifying the bus image as untrue. Upon being shown the card, people reacted with, for example, “a pack of lies” (70B), “Farage, lies, deceit, it’s all wrong!” (74B), “it’s all lies” (76B), “a complete lie and the figure is ridiculous” (65A), and “lies and deceit” (41B). Participants mocked the bus: “[pointing to the bus] is that Mr Frottage [sic] in the driving seat?! With Mr Johnson! [laughing]” (66B), whereas some more judiciously posed their reaction as a question: “it’s not true, is it?” (25B). A small number were more aggressive, stating bluntly “They [the Leave campaign] should take responsibility—criminal responsibility” (55B). In Northern Ireland, a small but notable group of participants used the particularly strong words “bullshit” and “bollocks” (4%), whereas in England the word “bollocks” featured 6%. Two in Newry called it “‘bullshit’ and that everyone knew it at the time” and “absolute bullshit,” whereas others used combinations of words to similar effect—“a complete hoax,” “manipulation,” “a load of old crap.” Overall, of interviews including reactions centring on the bus, in Northern Ireland 82% had a negative reaction, compared with 77% negative reactions in England.

We found the bus prompted skepticism and anger toward the Leave campaign. Such reactions address, on the one hand, to the ability of photo elicitation to evoke strong emotional responses, and in this respect we can see the method worked successfully. We would also expect a study showing participants a photograph closely related to politics to easily feed partisan political or ideological cues (although the bus picture did not include any other identifying markers of politics, such as parliament, or either of the main political parties). Importantly for our purposes though, the photo did not elicit the emotional response existing literature suggests—that is, expressions of support coupled with distrust toward elite Remainers. Perhaps influenced by subsequent media coverage of the £350 million promise and its outing as a falsehood, participants’ emotions—particularly those who openly said that they voted to Leave (despite us not requesting such information)—were notably visceral in their condemnation of the promise and distrust in those who advocated it. Of our interviews involving reactions centering on the bus, only 23% of participants stated they believed the bus was true, although with significant difference between field sites (36% in England, 15% in Northern Ireland).

This theme reveals two compelling insights. Most compelling in terms of our interpretation of what this means for how left behind communities feel about Brexit is one participant’s reference to “the bus of lies” (38A). This framing suggests, for this participant, the bus took on a symbolic status representing not merely the particular falsehood of the £350 million promise but the Leave campaign in general and the referendum as a whole. This participant, a man in his late 30s, from Bristol but living in Newry, was relatively wealthy compared with other participants and voted “enthusiastically to Remain.” His insight with this phrase, however, was pertinent because it evokes interpretations of the bus as an embodied object of distrust. Research on the sociology of emotions suggests emotions do not become fully realized until they are attached to a physical event or object. As Turner (Reference Turner2009, 342) summarizes, “emotions are not formed until there is an appraisal of objects and events; only after the appraisal has occurred are the relevant emotions activated.” Distrust and disengagement from politics has been linked, for example, to physical objects like the second houses of MPs during the 2008 expenses scandal. In this case, it seems less important what the political theme was (Brexit), and more that it prompted the response of distrust (of all politicians and/or the political process in general).

Second, participants’ particular use of “bullshit” or “bollocks” is interesting not necessarily for evoking feelings of disillusionment, as some scholars feared not acting upon the signal of the referendum result would invoke, but of incredulity. Looking to the literature on the political economy of “bullshit” rhetoric, we can see bullshit is defined as “a lack of concern for factual information in favour of trying to shape attitudes and beliefs” (Antova et al. Reference Antova, Flear, Wood and Hervey2019). By stating in blunt terms that they were seeing “bullshit,” participants showed an intuitive understanding of the campaign promise as deliberately misleading, based on a manufactured statistic that those who ran the campaign themselves did not believe. Their responses appeared to us less like dejected disillusionment and more like cynical disbelief at political rhetoric they perceived as manipulative and inaccurate.

This evidence of distrust suggests a dislocation between the policy preferences of interviewees and the preferences implied in the photo elicitation. More specifically, it suggests that whatever interviewees’ personal preferences for change, the policy changes implied by the bus photograph (exit from the EU followed by NHS investment) were not viewed as credible in the interviews. Thus, we argue that the first stage of participants’ articulations of their policy preferences for Brexit was to distance themselves from the preferences implied by the elite-led Vote Leave campaign. This is significant, given the wider importance of elite cues for policy debates among the public. Members of the public often take their preferences from political elites, either agreeing or disagreeing with party platforms. In this research, however, the reaction of interviewees was to distance themselves from policy options provided by elite-endorsed policy prescriptions. As one middle-aged white man in Derry reacted sardonically, “it’s all elections isn’t it?” (127B).

Trustworthiness of Politicians

The incredulous reaction of our interviewees can be viewed as a distancing mechanism from which they begin to articulate their own policy preference. In adopting positive marginality, participants must first reject elite policy cues. Our second theme taps into how interviewees positioned their own thinking in a critical way toward mainstream policy preferences, specifically by questioning politicians’ trustworthiness.

In this theme, we identified and coded participants whose reactions focused on politicians and generated percentages for those indicating they felt politicians were untrustworthy in general, indicated specific politicians they felt were untrustworthy, or combined both general and specific evaluations of untrustworthiness in their evaluations. Last, we coded feelings of “disconnection,” where participants explicitly stated they had feelings of being disconnected from politicians. We find in this theme that participants’ feelings of politicians as untrustworthy were generic and generalized as opposed to directed at specific politicians or parties. This throws into doubt claims of a specific disconnection between politicians and communities prompted by significant political events and suggests a more general lack of trust in politics.

The dataset shows, across all four field sites, a higher percentage of respondents referring to politicians as untrustworthy in general rather than specific politicians they find untrustworthy. The difference is most notable in England; in Rochdale 52% of participants with a reaction focused on politicians stated they felt politicians in general were untrustworthy compared with 31% stating they felt specific politicians were untrustworthy. Similarly, in Rotherham, 45% focused on politicians in general as untrustworthy compared with 26% focusing on specific named politicians. In Northern Ireland, the picture is more mixed. Newry paints a similar picture to England; 41% of participants with a reaction focused on politicians stated they felt politicians in general were untrustworthy compared with 27% focusing on specific politicians. In Derry, however, the levels are reversed: 46% focused on specific politicians they found untrustworthy compared with 25% with a reaction focusing on politicians in general. Interestingly, the data suggest only a very small percentage of participants coded in this theme explicitly mentioned a disconnection between themselves and politicians when we prompted them to reflect on their feelings of untrustworthiness. In Derry, Newry, and Rochdale, less than 5% (3.0, 0.5, and 1.0%, respectively) mentioned they felt a disconnection from politics and/or politicians, whereas in Rotherham 5.6% mentioned a disconnection.

Although the overall number coded in this category is relatively small (49 participants in total, including our pilot in Sheffield) our data still offer some important insights on the process of policy preference formation. Derry is an outlier here—assessments of trustworthiness fall on specific political institutions and parties. We observed one participant comment, for example, that “all politicians told lies, from the DUP (Democratic Unionist Party) to Sinn Féin, to get votes” (165A). Our notes also state, “The man [participant] did not vote in the Referendum, because no point, all politicians say lies and make business. He [said he] would ‘bomb Stormont, kill all politicians, and start anew’” (214A). This may be due to the distinctive political history of Derry as a center of political tensions and violence during the Troubles, during which time particular figures in the Irish Republican Army and the British police gained notoriety in the city, as shown by the range of political graffiti we observed in the city during fieldwork. In Newry, Rochdale, and Rotherham, assessments of trustworthiness were more diffuse. We observed one participant in Newry state that “She was angry at the politicians, because they never saw the truth, they never gave people the facts, they mislead people” (52A), whereas in Rochdale one participant “wouldn’t trust politicians, because they are liars and crooks and all the same” (60A). In Rotherham, we observed one participant state “About politicians,” she said she couldn’t give a ‘monkey’s ass,’” (110A) and another asked rhetorically upon seeing the photo, “well, do you believe politicians?” (108B).

These findings suggest that assertions that politicians were untrustworthy were posited at a general level. Participants reinforced common negative tropes about politics and politicians as being ethically dubious and low in public esteem, reinforcing well-documented evidence on negative public perceptions of politics in western liberal democracies (Hay Reference Hay2007). However, we did not find evidence of a specific disconnection rooted in particular policy decisions, party or ideological shifts, Brexit itself, or the European Union. We did not, for example, find any direct evidence of the effects of the infamous parliamentary expenses scandal of 2008; although we did find one angry participant in Rotherham claim, “Politicians earn too much and claim too many expenses, allowances, and gifts and they employ their families” (116A). Our argument is that these assertions allowed interviewees to begin to frame their own policy preferences by distancing themselves from formal political institutions, specifically by questioning the integrity and character of any and all politicians to effectively deliver on any policy proposals.

Ambition for the NHS

The subsections above suggest the photo elicitation provoked a negative reaction in which interviewees dismissed the policy proposal itself, then distanced themselves more generally from politicians and political institutions. We suggest this distancing mechanism allowed them to talk in some detail about the NHS and begin to elaborate their preferences through reference to their own personal experiences, which they associated positively with a preference for investment in the NHS.

Many participants used the photo as a prompt to begin talking about the need for NHS investment. Of instances where participants reacted to the theme of the NHS/health care (n = 291), 38% had a positive reaction to the NHS and 40% stated they want more resources for the NHS. Only 2% stated they wanted fewer resources. As one white, middle-aged local in Derry commented, “I agree with that. More money for the NHS would be good. More GPs and nurses” (139B). The specific funding amount was particularly resonant: one participant said when asked what’s the first thing that came to mind: “money.” This was because “‘If we could get money back from where we’re sending it and put it in’ the NHS that would be ‘so important.’ Doctors, hospitals are stretched and stressed” (147B). Others reflected this with strong emotional attachment. We observed one woman say in reaction to the photo that “she was very passionate about the NHS” (40A). For these participants, the photo pulled them emotionally in two directions. On the one hand, their instinctive reaction was to call the picture “lies” or “bullshit,” but on the other hand they used the rest of the conversation to segue into discussing how the NHS might receive further funding “on the ground” for “doctors and nurses.” This is reflected in the high numbers both voicing positive views of the NHS but also demanding more resources.

Other participants took a more easily recognizable logic of supporting the statement in principle, distancing themselves from trusting elite politicians and then making a link between NHS capacity and immigration (see also theme 6). For one retired man in Rochdale, we observed, “He liked the statement as he read it, but also added that he wouldn’t trust politicians, because they are ‘liars and crooks’ and all the same. To him the NHS used to be ‘the envy of the world.’ But now saw how health tourists keep coming to England for the NHS and argued that the NHS should ban health tourism” (60A). Again, in Rochdale, we observed an Asian man in a wheelchair who “read the statement [on the bus] and thought it was horrible that the UK would send so much money to the EU… . He voted to Leave and his reasons included problems with too many immigrants and asylum seekers… . He used the NHS a lot recently, because he had a stroke. He would employ more and younger nurses to improve the NHS” (61A).

Our notes also show in one interview explicitly mentioning “bullshit,” the person “did not dispute the figure, but argued that he could not see the money ever being put in the NHS. At the same time he thought that money for the NHS had a better chance to come in the NHS if we were out of the EU.” Such contradictory statements were typical of our interviews. Stoker and Hay (Reference Stoker and Hay2017) have argued the public can agree with contradictory statements about politics even if they are closely related to each other. Such contradictory statements are in line with expectations from methodological approaches using photos, prompts, and other methods to facilitate “fast thinking” such as those employed by Stoker and Hay (Reference Stoker and Hay2017). However, our approach also provides an interesting and counterintuitive contribution to the argument in the existing Brexit literature that left behind communities want Brexit in order to facilitate investment in the NHS. Scholars have pointed out that all forms of Brexit will have detrimental consequences for public finances and the NHS in general (Fahy et al. Reference Fahy, Hervey, Greer, Jarman, Stuckler, Galsworthy and McKee2017). Our data show a dissonant relationship between opposition to some of the claims made during the referendum about how much money would go into the NHS and an intuitive and more-informed understanding that such investment is required, particularly in hospitals and doctors’ surgeries. Often, there was an uneasy tension between these two themes. To navigate the above tension, participants resorted to telling stories of their own experiences using the NHS:

“If you’re old you get free transport on the NHS.” He has used the NHS. Wants more mental health provision. Tells a story about his brother who died in 1983. They didn’t have machines for CAT scans then. Alcohol is a big problem, and more mental health services are needed. (180B)

Story about the NHS—wife injured her foot, had to stay in a Greek hospital, foot got infected—he showed very graphic photos—local hospital was a better service but they couldn’t save his wife. So story is that health care is supposed to be equal across the EU but it isn’t, and our (i.e., the English) NHS is better, according to him. (133A)

“Lies” (very quickly). Why? “Because I’m a nurse in the NHS. The NHS needs to fund more nurses and GPs, surgeons etc. It’s short of money.” She had a whole monologue ready—had possibly told that before. (145B)

In each case, the participants identify the bus as a “lie” and then move directly to their own personal story. Their distancing mechanism then allows them to start from a position of positive marginality—articulating a personal, local experience that concretely confirms their view on policy—a desire for more investment in the NHS from a distrust of politics, politicians, and the Leave campaign. One participant from Derry, a man in his 40s, exemplified this contribution we make to existing research. We reflected on one interview:

He didn’t know the bus, but read the message and thought that it was really good, the NHS should indeed get more money. He didn’t engage with the figure and because he seemed reluctant to talk; I didn’t press… . He hadn’t used the NHS in a long time but would improve waiting hours in the A & E. He was hopeful that Brexit might have a positive influence on health but did not elaborate how … bus as aspiration rather than promise perhaps. (209A, italics added)

Our argument is that people in left behind communities in our study articulated their policy preference as an aspiration beginning from a small, marginal, or local observation. Aspirational claims are, by nature, ambitious and often unlikely to be fulfilled. Nor is there an expectation that they be fulfilled or a sense of demonstrable or measurable failure if they are not. Nevertheless, those who choose to accept aspirational claims as legitimate articulations of policy preferences do so with strength of purpose that is difficult to understand from distant social positions, such of those of academic researchers. Ambition can hide ulterior motives. For example, as the quotations from 60A and 61A illustrate, the ambition to invest in the NHS acts as a foil for the policy preferences of cutting immigration. Such logic was common for those participants we perceived to be “hard Leavers”—those who revealed with gusto their Leave vote in the referendum itself. Nevertheless, we also found this logic in interviews where participants were, in principle, either ambiguous in their referendum vote, or revealed they voted Remain.

Responsibility

Although we have argued that our data suggest participants did not identify a specific disconnection that they felt between themselves and their communities and politicians, they harbored ambitions for investment in the NHS. Our fourth theme, “responsibility,” adds nuance to this picture, by suggesting participants have complex and conflicting preferences of whether public, private, or voluntary sectors ought to be responsible for health care and the role of personal responsibility. These complex preferences emerged as they began to consider trade-offs between policy options.

Overall, 96 interviews mentioned the issue of responsibility, either for health and health care in general or health care services in particular. The results here do not clearly answer the question of how participants preferred investment in health care to occur. Results show very mixed conceptions of which sectors ought to be responsible. In our two England sites, of 51 interviews coded for responsibility, 53% stated health care should be an individual responsibility or provided as a matter of charity, whereas 24% of interviews stated that the UK could not “afford” a national health care system, or that the NHS should involve more private sector provision, or stated that the NHS is mainly for “rich people.” Overall, 86% of these interviews stated that anything other than the state ought to be responsible for the NHS. However, many of these interviews were convoluted on the precise question of where responsibility ought to lie; 39% of interviews suggested the state or government should be responsible or that health care is a collective responsibility or an entitlement as of right. Similarly, in our Northern Irish sites, 71% of interviews mentioned anything other than the state, government, or public sector ought to be responsible for health care, but 56% of interviews suggested the opposite; state, government, or collective responsibility should take priority. Across our field sites, participants tended to view health care as a nonstate responsibility, but within the same conversation they would assert a role for the state.

The evidence thus suggests some complex preferences. Participants stated, for example, that “Both the government and we are responsible for health and that people should not rely on the NHS too much” (30A, Newry), and we observed one woman state that “To her the government is responsible for where the money goes, but people are responsible for not misusing the NHS” (64A, Rochdale). Participants also diverted the conversation to other policy areas, for example in one interview with two participants:

But then she turns the conversation to investment in education, saying, “people just rocking up to A&E is not helpful.” Younger one says “people should take responsibility for their health too.” (33B, Newry)

Participants also drew again on personal health practices in illustrating their preferences. We noted of one Rotherham man, “He told me he keeps very fit, as the NHS would be a bad experience” (166A) and a woman in Newry, “She would eat fresh food, instead of having to go to the NHS for health related procedures. She struck me with the argument that we are responsible for our health as much as the government is” (27A). Others related their responsibility for health care to personal consumer choices. In Rochdale, one participant commented “I pay for my phone and my Spotify, why not pay for my health care too?” (60B), and another mentioned, “people should invest in their health” (2A, Sheffield).

This theme shows our participants were, at times, confused about who or what they preferred to be responsible for health care in the UK. Our data suggest that although participants clearly preferred investment in the NHS, they were more unsure about precisely where responsibility should lie for improving health and health care. This theme suggests that certainty over policy preferences became less clear, as interviewees sought to articulate at a more abstract level. The clarity they initially gained from being able to distance themselves from politicians and the referendum campaign became fuzzier when considering distinctions between concepts of “public,” “private,” “voluntary sector,” and other abstract notions of “responsibility.” Returning to the positive marginality explanation, this evidence suggests policy preferences are articulated more clearly when related to individual experience, as stimulated by the photo elicitation.

Lack of a Link between Brexit and NHS

Although interviewees did not articulate strong preferences around nuanced abstract questions of public, private, voluntary, and other sectoral responsibility for health care, they articulated clear negative preferences for what NHS investment should not be related to. In this case, despite the photo elicitation seeking to prompt emotional considerations around the relationship between Brexit and NHS investment, interviewees either refused or failed to recognize this connection.

Many respondents saw little, if any, link between a policy preference—investment in health care service—and the institutional process of Brexit. In 292 interviews commenting on the NHS (more than the actual total of 291 because participants contradicted themselves within a single conversation, so were double-coded), we coded those that (1) made an explicit or nuanced link between Brexit and the NHS (n = 110), (2) commented on the NHS but did not make a link to Brexit (n = 157), or (3) commented on the NHS and actively said that there was no link between the NHS and Brexit (n = 25). In 62% of coded interviews, no link was made between the NHS and Brexit or participants actively denied that there was a link, even when nudged to consider the relationship. Our data even show that a minority of participants pushed back against our prompting them to consider a link, suggesting there was no link. We noted of one Rotherham participant, “She is avoiding the cue to link Brexit and the NHS—possibly because she never saw the claim—although she does sort of agree with it” (49B), whereas another Rotherham participant stated bluntly, upon being prompted, “Nothing will change after Brexit because it doesn’t address the problem” (87B, italics added).

We believe our data here suggest an important and unacknowledged fact for existing research; the logic that Brexit leads (or not) to investment in health care in the UK, one discussed extensively by media commentators and researchers, is not simply either true or untrue for the left behind communities who are commonly said to support this logic: individuals in these communities reject the premise of the logical relationship between the two processes (Brexit and health care investment) when they are presented with it and prompted to discuss it in qualitative research. It is not that participants were prompted to consider the UK’s exit from the European Union should (or should not) lead to further health care investment and addressed this question directly in yes or no terms. Rather, their common response was either not to perceive a relationship despite being presented with an image and being verbally prompted to consider the relationship or to deny the premise of the question altogether.

A significant insight here is that photo elicitation enables interviewees to reject, at least in part, policy preferences that are assumed in elite discourse to be common and integrated within elite policy debates. Here we see the empowering effect of photo elicitation, to give interviewees the opportunity to separate two preferences—Brexit and NHS investment—and to state either that they do not prefer both of these together or to dispute the logic that one preference ought to follow from the other. This evidence demonstrates our argument that photo elicitation enables interviewees to use positive marginality—to distance themselves from an image representing an elite campaign message and critically assess the logic implied by the message.

Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

Although the analysis presented above suggests participants did not perceive a relationship between health investment and Brexit, this does not discount that one particularly salient policy issue related to Brexit may have been more prominent in their thinking: immigration. Immigration and sovereignty are shown in survey research to be the most prominent issues related to Leave voters’ decisions (Goodwin and Milazzo Reference Goodwin and Milazzo2017) and therefore may have had a prominent role particularly in how professed Leave voters reacted to the photo elicitation. Could it be that participants did not comment explicitly on the relationship between Brexit and the NHS because reducing immigration was in fact a superior preference for them? Although our study was not focused on immigration, we coded immigration as a theme to shed light on this question.

Our coding results show 44 interviews that mentioned immigration in either a negative or positive light. This is a high proportion given that the photo elicitation prompt did not allude to immigration at all. Of these 44 interviews, 33 included expressions of anti-immigrant sentiment and 11 talked in positive terms about immigration, either explicitly or implicitly. Within these interviews, we can see participants who used the logic by which Brexit is linked to increased investment in the NHS to then express explicitly anti-immigrant sentiments. We documented examples of these in detail:

Argued upon being presented with the bus that “we should look after our own group first.” Man says, “Nothing against foreigners, but there’s too many of them. You see them queuing up on the hill” (presumably he refers to the local hospital). Woman complains it takes “too long to get an appointment” and links this to the “foreigners” who are “queuing up.” Reducing immigration will improve this, the man states, and “Brexit will be good.” Woman nods along. (18B)

“What’s the country coming to?” “I love the NHS and our armed forces but people from other countries are coming.” (41B)

About the NHS he said that doctors and social carers do a great job, but there are too many people coming here, going to the hospital for a thing when they shouldn’t and it is “ridiculous.” He then insisted that he is not “color prejudiced.” (112A)

We can thus see, in a minority of interviews (7.9% of n = 418 interviews), explicit examples of participants diverting the interview to a discussion of immigration. Participants linked a lack of health care access to migrant use of health care services and argued Brexit would reduce migrant numbers, thus leading (in their logic) to improved access to services. Participants thus diverted toward a logic explicitly promoted by the Leave campaign and the UK popular tabloid press, particularly the Sun and Daily Mail. However, as revealing as these conversations are about the strength with which a minority of participants chose to identify with the radical-right policy preference promoted by these newspapers, these interviews did not make up a significant percentage of overall interviews. Therefore, we suggest that they do not override the trends we identify about health care through analysis of our other themes.

Discussion and Conclusion

To recap, our research sought to picture the policy preferences of left behind communities in the UK regarding Brexit—a policy process that will have profound implications for their lives and about which they may have strong feelings. We used a photo elicitation methodology to capture these preferences while accounting for the methodological challenges of stigmatization. Our argument is that the data suggest that individuals we interviewed in stigmatized left behind places do not accept a link between NHS investment and Brexit. They rejected the framing of the two policy preferences as linked and instead elaborated preferences for health care investment based on individual experience.

Substantively, this article suggests that the findings in the existing Brexit literature showing support for investment in the NHS as a logical and linked consequence of Britain leaving the EU more accurately reflect, in left behind communities, dissonance between support for such investment and simultaneously distrust that such investment will happen, or is even intended, as a result of Brexit. On the one hand, our data support the argument that left behind communities are in favor of investment in health services, which are interpreted as failing as a result of government-mandated austerity, perhaps, but not necessarily, linked to EU membership. However, our research does not support the argument that left behind communities interpret Brexit and the Leave campaign promoting it as a popular antidote to elite Remainer institutions. Instead, participants in our study reacted to pictures of the battle bus with scorn and opprobrium, calling it a “lie” and “bullshit.” They linked this reaction to broader distrust of all politicians. Therefore, our study supports elements of existing research on public preferences for state investment in health care but decouples these from Brexit as a political process. We do not claim to have found unique dynamics in these communities that are not present outside left behind communities. Our argument is relevant to the claim that left behind communities—that is, communities who live in places that are stigmatized by elite actors as left behind—interpret Brexit as an “opportunity” to invest in the NHS. The research brings into question this assumed relationship. We also show that the issue of immigration, although relevant to a minority of respondents, did not substantively shape our findings.

The research also demonstrates the value of photo elicitation as a research method in political science. To elaborate this value, it is first crucial to clarify the issue of generalizability. We cannot and do not claim statistical generalization from our sample (N = 418 interviews) because it involves a nonprobabilistic street intercept recruitment method. It is “biased,” necessarily, toward participants who were likely to be walking around town centers between 09:00 and 17:00 hours on weekdays. To the objection that our sample is “unrepresentative,” we respond that it is inappropriate to hold qualitative research on hard-to-research stigmatized groups to such standards (Tourangeau et al. Reference Tourangeau, Edwards, Johnson, Walter and Bates2014). The value of our approach is to provide rich descriptive data on policy preferences of individuals living in places that are stigmatized as left behind in public debate. We carefully selected the field sites to ensure they met the socioeconomic and geographical characteristics of such places (see Table 1).

Our purpose was to address methodological challenges in collecting descriptive data on the policy preferences of individuals living in places stigmatized as left behind. These include hesitancy in responding to researchers due to social stigma and social desirability bias influenced by affective polarization over Brexit.

Bearing this first point in mind, the value of our approach was in enabling positive marginality for interview participants—enabling interviewees to articulate positive policy preferences from their marginal position in stigmatized left behind places. Presenting a relevant photograph in a loosely structured street-level interview allowed interviewees to consider any emotional entanglement with Brexit, before responding in stages. Interviewees reacted negatively to the photo, indicating distrust in politics and politicians. However, many interviewees then used the interviews to elaborate a preference for investment in the NHS, separately from the policy changes associated with Brexit. We suggest the photo elicitation successfully enables participants to articulate policy preferences without being beholden to social desirability bias because they were able to separate and reject the implied logical connection between Brexit and health care investment established by the £350 million investment campaign proposal. Photo elicitation may thus play a specific role in empowering interviewees in qualitative research to reject the imposition of elite policy options, separate out preferences from elements they find emotionally contentious, and reclaim policy preferences—like health care investment—implied by elite messaging.

Our findings also suggest the specific benefit of photo elicitation in accessing public policy preferences via interviewees’ personal experiences. Public knowledge of factual details and reputations of public policies, institutions, and agencies is notoriously fuzzy (Overman, Busuioc, and Wood Reference Overman, Busuioc and Wood2020). Photo elicitation allows researchers to access data on public policy preferences via personal experiences, overcoming challenges in a lack of detailed public knowledge about policies and institutions. When prompted to assess responsibility for health care policy and name preferred abstract agents who they think ought to have responsibility (for example, public, private, or voluntary sector agents), respondents indicated confusion. Such a limitation is unsurprising given the street intercept method we employed to address methodological issues. Participants were not given extra time and information, as in a focus group methodology. Focus group research elicits detailed consensual group justifications for policy preferences (Diamond Reference Diamond2021), whereas our methodology sought to elicit individual reactions and preferences, with little information. Where participants did describe policy preferences in detail, they used their personal experiences to elaborate preferences for health care investment. The photo elicitation allowed them to distance themselves from elite policy framing and center their personal experiences, from which they elaborated broad preferences for health care investment. Future research might combine focus group methods to enable research to elaborate these preferences based on personal experience into more concrete proposals.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001186.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation for this study is openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RFC66F. Limitations on data availability are discussed in the appendix.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Simon Rushton, Anastasia Shesterinina, Jack Corbett, and Daniel Wincott for their help and encouragement. We are extremely grateful to the editors and the reviewers of APSR for their incisive comments on the manuscript.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the United Kingdom Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/S00730X/1.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the University of Sheffield Department of Politics and International Relations and certificate numbers are provided in the appendix.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.