1. Introduction

As cross-linguistic communication becomes more commonplace, interest in the cognitive and psychological changes experienced by individuals when using a foreign language is growing. The foreign language effect (FLE) relates to how people's judgments and decisions can be slightly different in a foreign language compared to in their native tongue (Keysar et al., Reference Keysar, Hayakawa and An2012). One line of research in the FLE suggests that people may detach from social norms acquired in their native language in executing several behavioral tasks in a foreign language. For example, Gawinkowska et al. (Reference Gawinkowska, Paradowski and Bilewicz2013) asked sequential bilingual participants to translate expletives and ethnophaulism between their native and foreign languages. They observed that participants' translation choices in the foreign language were much harsher than in their native language, suggesting loosened social norms in the foreign language. In the moral domain, Geipel et al. (Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b) examined sequential bilingual participants' judgments of several sacrificial dilemmas, revealing that moral judgments tended to be less severe in the foreign language. These authors related this finding to the language specificity of memories (Marian & Neisser, Reference Marian and Neisser2000), which entails limited access to social norms in a foreign language compared to the native language. Additionally, the FLE in social norms may be attributed to reduced sensitivity to undesirable consequences in norm-violation (Białek et al., Reference Białek, Paruzel-Czachura and Gawronski2019). Furthermore, the upholding of social norms can also be destabilized when individuals are exposed to foreign-accented speech (Bazzi et al., Reference Bazzi, Brouwer, Almeida and Foucart2022). In sum, the collection of these findings indicates that social norms regulating judgments and decisions may be somewhat different in a foreign language compared to the native language.

To investigate how language influences social norms, it is essential to understand how language and social norms interact. Language acquisition is believed to be a statistical process linked to the frequency of word representations as clusters of grounded experiences (Adams, Reference Adams2016; Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2010; Buccino et al., Reference Buccino, Colagè, Gobbi and Bonaccorso2016; Kiefer & Pulvermüller, Reference Kiefer and Pulvermüller2012). The exemplar theory stipulates that linguistic experiences are stored in the brain as exemplars, which are detailed memory traces formed from past linguistic encounters (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Nolan and Drager2006; Nosofsky, Reference Nosofsky, Pothos and Wills2011; Smith & Church, Reference Smith, Church, Vonk and Shackelford2021). In other words, these exemplars store not just the linguistic information such as form and meaning but also information about the social contexts in which they are encountered (Foulkes & Docherty, Reference Foulkes and Docherty2006). Thus, the mental representation of language comprises a network linking linguistic features along with their various social meanings and the contexts of their usage, i.e., social norms. The frequency with which an individual encounters a linguistic feature in various social settings influences the activation of different meanings (Wagner & Hesson, Reference Wagner and Hesson2014). Hence, the embodied nature of a cognitive process like language entails that the use of a certain language impacts the activation of social norms retrievable from memory (Marian & Neisser, Reference Marian and Neisser2000). Since most people acquire norm concepts in their childhood through the socialization process (Corsaro & Fingerson, Reference Corsaro, Fingerson and Delamater2006; Kesebir et al., Reference Kesebir, Uttal and Gardner2010), social norms are frequently activated in the native language (Grimshaw, Reference Grimshaw1973; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill2000). Whereas, social norms are activated less frequently in the foreign language of sequential bilinguals, and consequently less fluently retrieved from memory (Kauhanen, Reference Kauhanen2006). To summarize, social interaction is often vehiculated and consolidated by language, suggesting that the acquisition and activation of social norms may be language-dependent.

The language-dependent nature of cultural norms has been well documented in past research. For example, Ramírez-Esparza et al. (Reference Ramírez-Esparza, Gosling, Benet-Martínez, Potter and Pennebaker2006) found that Mexican-Americans exhibited higher levels of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness when interviewed in English compared to Spanish, suggesting simultaneous bilinguals may impersonalize two cultural frames. Further research showed that simultaneous bicultural and bilingual individuals seem to have no problems switching from one cultural frame to another (Ikizer & Ramírez-Esparza, Reference Ikizer and Ramírez-Esparza2018). However, there is contention on whether monocultural sequential bilinguals function similarly to bicultural simultaneous bilinguals. While some argue that fluent switching of language-dependent cultural frames occurs only for people who internalized the two cultures, not necessarily those who simply speak two languages (Luna et al., Reference Luna, Ringberg and Peracchio2008). For instance, sequential bilinguals that were highly acculturated in the cultures of the two languages were indeed unaffected by the FLE in the moral domain (Čavar & Tytus, Reference Čavar and Tytus2018), suggesting that knowing another language does not imply automatic acquisition of cultural norms. Others suggest that sequential bilinguals may also store two sets of language-dependent cultural frames (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Lam, Buchtel and Bond2014) and personalities (Dylman & Zakrisson, Reference Dylman and Zakrisson2023), as their responses tend to align with the language they are tested. Although these studies suggest that sequential bilinguals may store two language-dependent cultural frames like simultaneous bilinguals, it is questionable whether this result could potentially extend to social norms. While cultural frames represent broad, deeply ingrained practices and values that are pervasive across a cultural group and are stable over generations (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Morris, Chiu and Benet-Martínez2000), social norms are more context-specific and fluid, varying according to the immediate social setting and group dynamics (Etzioni, Reference Etzioni2000). It is yet unclear whether social norms in sequential bilinguals vary in their distinctiveness, associated with the culture of origin of the native or foreign languages, or in the level of activation, depending on the individual experience and frequency of use of the native and foreign languages.

When studying the impact of language on social norms, it is also important to consider the role of affect. Previous studies on the influence of foreign language on social norms have focused exclusively on contexts of high negative affect, e.g., swear words (Gawinkowska et al., Reference Gawinkowska, Paradowski and Bilewicz2013) or moral dilemmas (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b). In these contexts, the impact of language on social norms can be muddled by the presence of negative affect. For example, bilingual research has shown repeatedly that a second language is less emotionally engaging than a first language, such as for taboo words (Dewaele, Reference Dewaele2004, Reference Dewaele2008) and childhood reprimands (Caldwell-Harris et al., Reference Caldwell-Harris, Tong, Lung and Poo2011). Especially, discrete negative emotions such as fear and disgust can be less intense in a foreign language (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Klesse2018; Wu & Thierry, Reference Wu and Thierry2012). Furthermore, reduced negative affect in a foreign language is evidenced physiologically by less electrodermal activities (Caldwell-Harris & Ayçiçeği-Dinn, Reference Caldwell-Harris and Ayçiçeği-Dinn2009) and pupillary dilation (García-Palacios et al., Reference García-Palacios, Costa, Castilla, del Río, Casaponsa and Duñabeitia2018; Iacozza et al., Reference Iacozza, Costa and Duñabeitia2017). Therefore, in order to establish a robust argument regarding the impact of a foreign language on social norms, it is crucial to consider the polarity of affect in the experimental stimuli. That is, if the modulating effect of language on social norms is robust, it should be independent of the affect in the stimuli.

Lies serve as optimal experimental stimuli to investigate the impact of a foreign language on social norms. Lies are defined as statements made by the ones that do not believe them with the intention that others shall be led to believe them (Isenberg, Reference Isenberg1964; Mares & Turvey, Reference Mares and Turvey2018), and they are strongly regulated by social norms and can be culturally specific (Dor, Reference Dor2017; Grice, Reference Grice1995). Studies have estimated that people lie at the frequency of once or twice per day (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, George, Burgoon, Adkins and White2004; DePaulo et al., Reference DePaulo, Kashy, Kirkendol, Wyer and Epstein1996), but the actual number can be much higher as people often do not realize the lies they tell or hear. This is because not all lies are the same, for instance, we often hear and use the terms “black lies” and “white lies” in vernacular English to describe normally unacceptable lies and acceptable lies, respectively. In other languages, the latter can take on different labels such as mentiras piadosas (pious lies) in Spanish, petits mensonges (little lies) in French, or 善意的谎言 (well-intentioned lies) in Chinese. Lies are categorized based on their social acceptability (Oliveira & Levine, Reference Oliveira and Levine2008). For example, Lindskold and Walters (Reference Lindskold and Walters1983) initially proposed six categories of lies according to intent, impacts on others, and the repercussions for oneself. Successively, Backbier et al. (Reference Backbier, Hoogstraten and Terwogt-Kouwenhoven1997) identified importance of the matter and closeness of the relationship between the deceiver and the deceived as factors influencing the acceptability of lies. Furthermore, Levine and Schweitzer (Reference Levine and Schweitzer2014) demonstrated that the acceptability of lies was sensitive to the consequences for the deceived, but insensitive to the consequences for the deceiver. Additionally, Seiter et al. (Reference Seiter, Bruschke and Bai2002) argued culture to be an important predictor of acceptability of lies alongside intent and relationship type, for example, Euro-Americans rated lies as more acceptable than Ecuadorians (Mealy et al., Reference Mealy, Stephan and Urrutia2007). More recently, Cantarero et al. (Reference Cantarero, Szarota, Stamkou, Navas and Dominguez Espinosa2018) suggested the beneficiary, the underlying motivation, the specific circumstances, and cultural variations as considerable factors in determining the acceptability of lies. Despite the multitude of factors influencing the categorization of lies, there is a consistent and culturally robust distinction that some lies are normally more acceptable than others (Cantarero et al., Reference Cantarero, Szarota, Stamkou, Navas and Dominguez Espinosa2018; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Lee, Cameron and Xu2001, Reference Fu, Xu, Cameron, Heyman and Lee2007). For the sake of the simplicity of language, we hereafter refer to those normally less acceptable or norm-violating lies as “black lies” and those normally more acceptable or norm-adhering lies as “white lies.”

It is worth mentioning that black and white lies can be defined differently according to the underlying factors in each specific study. In the current study, we adopt these two labels because black lies are consistently rated as less acceptable than white lies, making these two conditions easily distinguishable. A plausible explanation for this is that black lies are usually linked to a higher level of negative emotions (Bond & Lee, Reference Bond and Lee2005; McCornack & Levine, Reference McCornack and Levine1990; Porter & Ten Brinke, Reference Porter and Ten Brinke2008). For example, studies have shown that people often report feeling more stressed when telling black lies compared to telling the truth (Caso et al., Reference Caso, Gnisci, Vrij and Mann2005; DePaulo & Kashy, Reference DePaulo and Kashy1998). This subjective feeling is evidenced also by increased electrodermal responses (Furedy & Heslegrave, Reference Furedy and Heslegrave1988; Furedy et al., Reference Furedy, Posner and Vincent1991) and enhanced activation of the amygdala, which is an indication of hightented anxiety (Abe et al., Reference Abe, Suzuki, Mori, Itoh and Fujii2007). On the other hand, white lies are considered socially harmless (Dietz, Reference Dietz and Meibauer2018) and are low in negative affect (Cantarero et al., Reference Cantarero, Szarota, Stamkou, Navas and Dominguez Espinosa2018; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Casado and Martín-Loeches2016). In fact, violating social norms by telling the blunt truth instead of white lies can trigger brain responses usually associated with unexpected events (Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Casado and Martín-Loeches2016), indicating that social norms require lying rather than telling truths in some circumstances. Therefore, if social norms were less potent in a foreign language, we would expect to see an attenuation of the difference in social acceptability between black lies and white lies in the foreign language compared to the native language.

One unexplored aspect of the FLE on social norms regards the specific type of social norms. Social norms are common standards within a social group regarding socially acceptable behavior in particular social situations, the breach of which has social consequences (Burke & Young, Reference Burke, Young, Benhabib, Bisin and Jackson2011; Cialdini & Goldstein, Reference Cialdini and Goldstein2004). They play a crucial role in shaping individuals' attitudes of various situations, influencing their intentions, and guiding their behaviors (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Wetherell, Cochrane, Hogg and Turner1990; McDonald & Crandall, Reference McDonald and Crandall2015). Social norms are measured by directly enquiring people about their attitudes or beliefs regarding certain social conducts (Dunkerley, Reference Dunkerley1970; Labovitz & Hagedorn, Reference Labovitz and Hagedorn1973). Within social norms, descriptive norms pertain to the attitudes and beliefs about the prevalence of behaviors, whereas subjective norms relate to perceptions of societal expectations (Costenbader et al., Reference Costenbader, Lenzi, Hershow, Ashburn and McCarraher2017; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Hong, Chiu and Liu2015). In other words, attitudes or beliefs regarding prevalent practices are termed descriptive norms, and they are measured by querying respondents about their perceptions of other people's actions (Cialdini et al., Reference Cialdini, Reno and Kallgren1990). Attitudes or beliefs concerning what society expects oneself to do are termed as subjective norms, and they are measured by querying respondents about their views on societal expectations regarding their own actions (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, Reference Fishbein and Ajzen2011). It is worth mentioning that there are other ways to categorize different social norms (Reynolds et al., Reference Reynolds, Subašić and Tindall2015). For example, Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1973, Reference Schwartz1977) distinguished “social norms” from “personal norms,” arguing that people adhere to social norms for the behaviors of others but adhere to personal norms for their own behaviors, while still acknowledging that personal norms develop from social norms. In this paper, we will be referring to the social norms regulating the perception of third-person behaviors as descriptive norms and those regulating first-person behaviors as subjective norms. Although previous research has shown that the regulatory strength of social norms in several behavioral tasks is reduced in a foreign language, it is yet unclear whether such an effect acts upon descriptive norms, or subjective norms, or a combination of both.

2. Method

The FLE has been investigated across various experimental paradigms. For example, the pioneering studies of Keysar et al. (Reference Keysar, Hayakawa and An2012) and Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and Keysar2014) both employed a forced-choice decision paradigm; subsequent research has delved into the phenomenon using different Likert scales to test judgments (Geipel et al., Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015a, Reference Geipel, Hadjichristidis and Surian2015b). In this study, we employ both measures to differentiate the impact of language on descriptive and subjective norms, comprising four experiments. Specifically, in experiments 1 and 3 we assessed the acceptability of third-person behaviors to gauge descriptive norms; in experiments 2 and 4 we examined first-person intentions and decisions, respectively, to understand subjective norms.

In experiment 1, two groups of participants evaluated the acceptability of black and white lies in either their native or foreign language using an 8-point Likert scale. We anticipated black lies to be rated as less acceptable than white lies, but crucially, the difference would be attenuated in a foreign language, reflecting the modulating effect of a foreign language on descriptive norms. In experiment 2, two groups of participants evaluated their intention to tell black and white lies in either their native or foreign languages using an 8-point Likert scale. We expected the intention ratings for black lies to be much lower than for white lies, and crucially, the difference would be attenuated in the foreign language, reflecting its effect on subjective norms. According to the notion that telling the truth is a default response (Verschuere et al., Reference Verschuere, Spruyt, Meijer and Otgaar2011), in experiment 3 we expected overall higher acceptability ratings in the truth-telling scenarios compared to the lie-telling scenarios. Critically, we hypothesized diminished difference in acceptability between telling white lies and telling the blunt truths in the foreign language than in the native, indicative of a foreign language's impact on the adherence to descriptive norms. In experiment 4, employing a forced-choice decision paradigm, two groups of participants made decisions about telling black and white lies in either their native or foreign language. We predicted a diminished distinction in the likelihood of making “Yes” decisions between black lies versus white lies in a foreign language, reflecting the impact of a foreign language on subjective norms.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Padua (Protocol: 4651) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Participants had to confirm they had received and understood the written information about the consent form to proceed with the experiments. All experimental materials, data, and analyses are provided at a repository on OSF (osf.io/dz3j8).

2.1. Experiment 1: lie acceptability in native and foreign languages

2.1.1. Materials

We selected six scenarios of black lies and six scenarios of white lies from previous studies (Cantarero et al., Reference Cantarero, Szarota, Stamkou, Navas and Dominguez Espinosa2018; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Casado and Martín-Loeches2016). In these scenarios, a person tells a lie to another person in various social circumstances (see Table 1 for examples). To ensure the structural similarity and overall length of the original scenarios, our research team slightly modified the wording of the scenarios in English. Next, these scenarios were proofread by a native English-speaker, and they were then translated into Italian by an English-Italian bilingual researcher. The protagonists of the scenarios are named with capital letters, e.g., A and B; all adjectives and pronouns in the scenarios were gender inclusive. In addition, we added six filler scenarios where the protagonists ask and tell well-known facts, e.g., A says to B that the capital of Spain is Madrid (see Supplementary materials for the complete set). Filler scenarios were added to ensure participants were performing the task correctly and as they are truth-telling scenarios, we expected to observe overall high ratings for these scenarios. The experiment was implemented on Labvanced (https://www.labvanced.com/).

Table 1. Example scenarios of the study in the foreign language (i.e., English)

2.1.2. Participants

The a priori power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) based on the effect size of .02 from Cantarero et al. (Reference Cantarero, Szarota, Stamkou, Navas and Dominguez Espinosa2018), an alpha of .05, and a power of .95 yielded a sample size of 84. We therefore recruited 85 participants (Mage = 27.71, SD = 6.63, 46 females) from the online crowdsourcing platform Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/), with pre-screening criteria for adult Italian citizens residing in Italy and Italian as their native language who also reported being fluent in English. The detailed participant profile can be seen in Table 2. Two-sample t tests for linguistic control variables between native and foreign language groups showed a significant difference for foreign language proficiency (t[1373.4] = 9.093, 95% CI [.42, .66], p < .001), with the participants reported higher proficiency (on a Likert scale from 0 to 10, with 10 being the highest) in the foreign language after completing the experiment in the foreign language (M = 8.37, SD = 1.04) compared to in the native language (M = 7.83, SD = 1.23); and for foreign language exposure (t[1360] = 7.646, 95% CI [5.91, 10.00], p < .001), with the participants reported higher exposure to the foreign language after completing the experiment in the foreign language (M = 67.81, SD = 18.04) compared to in the native language (M = 59.86, SD = 21.64). There may be several speculations as to why this occurred related to metamemory (Martín-Luengo et al., Reference Martín-Luengo, Hu, Cadavid and Luna2023), for instance, the self-confidence of the participant about their English proficiency may have increased after having successfully completed the task in English. Since this difference was irrelevant for the purpose of this study, we took the increased self-reported foreign language proficiency as an indication that participants had no problem understanding the scenarios in the foreign language and no further analysis regarding foreign language proficiency was performed.

Table 2. Demographic information and linguistic background of the participant pool with mean values and standard deviations in the brackets

2.1.3. Procedure

All participants completed the experiment on a computer. Participants consented to the experiment after reading the description. They were then randomly assigned to complete the critical task in either Italian (native language) or English (foreign language). Each participant read the instruction in Italian and completed two practice trials before the main task, consisting of 18 trials. The two practice trials were either in Italian or in English according to the language group the participant was assigned to. Each trial consisted of a written scenario presented in the middle of the screen (Lato font, size 18, and black color in bold) on a white background. Participants were required to indicate the acceptability of the behavior of the deceiver on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all acceptable) to 8 (completely acceptable), which appeared below each scenario. Participants proceeded to the next trial by pressing the spacebar, following the instruction “press the spacebar to continue” at the bottom of the screen. Finally, they filled in a demographic and linguistic background questionnaire. The entire experiment lasted around 9 min.

2.1.4. Data analyses

Out of the 85 participants, 41 participants completed the experiment in their native language and 44 in the foreign language. Upon closer examination, we detected a translation error in one of the white lies in the native language version (“A likes B” was translated as “A piace a B” instead of “B piace ad A”). We therefore did not consider data relevant to this scenario in the native language for successive analyses. The main analyses were performed using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R language (R Core Team, 2022).

2.1.5. Results

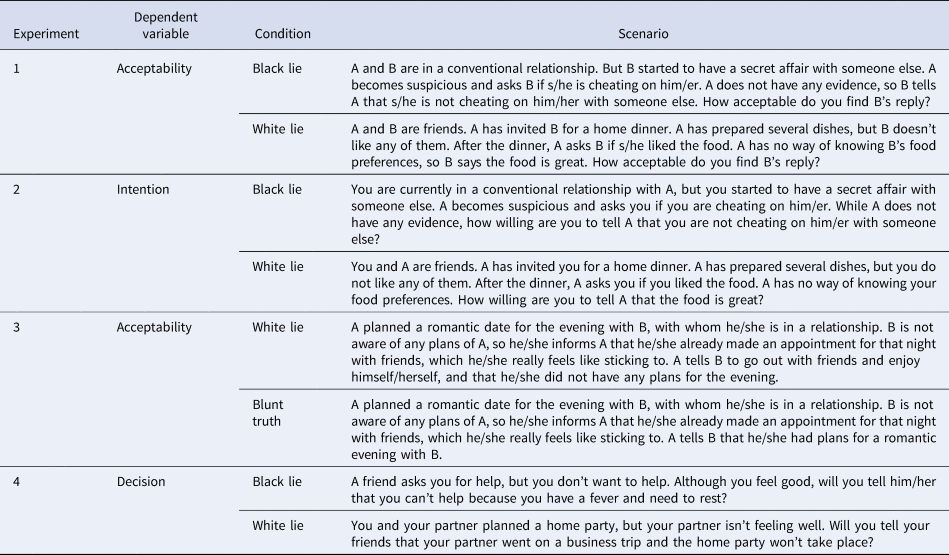

To examine the effects of language and lie type on the response, we conducted a linear mixed-effects regression analysis. The model included the fixed factors of lie (black vs. white), language (native vs. foreign), and the interaction between the two factors. The factors were Helmert coded (−1 vs. +1) to provide a clearer delineation of main effects in the models featuring interactions. Random intercepts for participants and scenarios were included in the model. The language factor did not reach statistical significance (b = .05, SE = .10, t[975] = .48, 95% CI [−.14, .24], p = .635). The lie factor showed a significant effect (b = 1.03, SE = .22, t[975] = 4.62, 95% CI [.59, 1.47], p < .001), with much higher acceptability ratings for white lies than black lies. The interaction between language and lie was also significant (b = .13, SE = .05, t[975] = 2.745, 95% CI [.04, .23], p = .006). This interaction is qualified by the opposite directions of the effect of language on acceptability (see Figure 1): for black lies the acceptability was higher in the foreign language (M = 3.51, SD = 1.98) than in the native language (M = 3.33, SD = 1.87), but that for white lies it was lower in the foreign language (M = 5.30, SD = 1.75) than in the native language (M = 5.77, SD = 1.51).

Figure 1. Pirate plot of the acceptability of black and white lies in native and foreign languages in experiment 1. The horizontal ticks (-) represent individual raw data points; the “bean” shape indicates the data density; the solid line represents the mean; the rectangular boxes represent the Bayesian highest density interval.

2.1.6. Discussion

The results of experiment 1 support the hypothesis that a foreign language impacts descriptive norms. We demonstrated this by showing an attenuated difference in the acceptability between black lies and white lies in the foreign language compared to the native language. Specifically, black lies were judged less severely in a foreign language compared to the native language, consistent with current theories that a foreign language can reduce negative emotions, which are often linked to black lies. But more interestingly, we observed a decreased acceptability for white lies in the foreign language (vs. native language), suggesting that a foreign language can indeed reduce the influence of social norms, as white lies do not normally have negative connotations. The cross-interaction of language and lie suggests that the modulatory effect of a foreign language on social norms could be somewhat independent from its effect on affect.

While ratings of lie acceptability do reflect one aspect of social norms, i.e., descriptive norms, the conclusions from these results could not be extended subjective norms. To explore whether the foreign language impacts subjective norms in a similar fashion as descriptive norms, a more designated measure was needed. Under the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen, Kuhl and Beckmann1985, Reference Ajzen1991, Reference Ajzen2011), subjective norms predict intentions that are direct antecedents to behavior, meaning that intentions and behaviors are strongly regulated by subjective norms. We therefore operationalized the difference with the intention to tell black and white lies to gauge the impact on subjective norms, and we expected to observe a reduced difference in the intention between black and white lies in the foreign language compared to the native language.

2.2. Experiment 2: lie intention in native and foreign languages

2.2.1. Design and materials

The scenarios of experiment 2 were adapted from experiment 1. That is, they were converted from third-person narratives to first-person narratives. Instead of measuring the acceptability of other people telling lies, we measured the participants' own intention of telling lies in these scenarios. Thus, in experiment 2 the participants were themselves the protagonists in the scenarios, in which they were asked to indicate their intention of telling a given lie on a Likert scale of 1 (not willing at all) to 8 (completely willing).

2.2.2. Participants and procedure

A total of 82 participants (Mage = 28.63, SD = 8.37, 38 females) participated on Prolific in this experiment. All eligible participants were native Italian speakers residing in Italy who reported being fluent in English. Forty-three of them completed the experiment in their native language and 39 in the foreign language (see Table 2 for participant details). Two-sample t tests for linguistic control variables between native and foreign language groups showed a significant difference for foreign language proficiency (t[1558.5] = 11.187, 95% CI [.57, .81], p < .001), with the participants reported higher proficiency in the foreign language after completing the experiment in the foreign language (M = 8.43, SD = 1.19) compared to in the native language (M = 7.74, SD = 1.18); and for foreign language exposure (t[1433.9] = 8.28, 95% CI [6.28, 10.18], p < .001), with the participants reported higher exposure to the foreign language after completing the experiment in the foreign language (M = 66.59, SD = 19.70) compared to in the native language (M = 58.36, SD = 18.37). Like experiment 1, we took the increased self-reported foreign language proficiency as an indication that participants had no problem understanding the scenarios in the foreign language and no further analysis regarding foreign language proficiency was performed.

The procedure of experiment 2 was the same as experiment 1: participants consented and read the instruction in their native language before being randomly assigned to the 2 practice trials, 12 critical trials, and 6 filler trials in either their native or foreign languages. The entire experiment lasted around 9 min.

2.2.3. Analysis and results

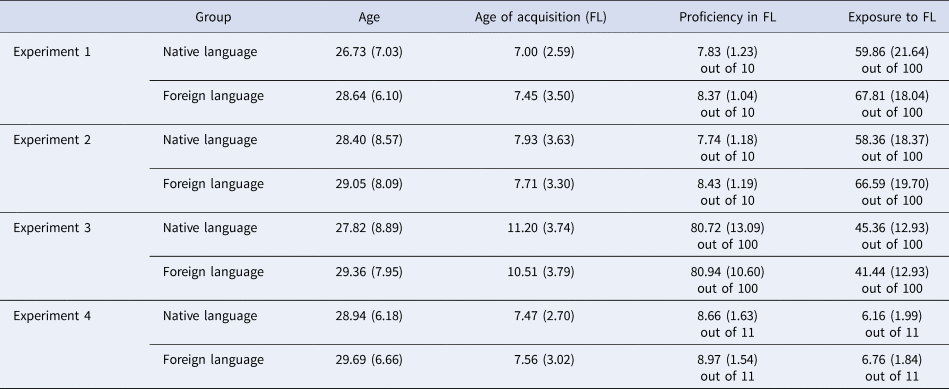

We used the same statistical analyses as in experiment 1 to examine the effects of language and lie on intention. The language factor did not reach statistical significance (b = −.06, SE = .10, t[980] = −.57, 95% CI [−.25, .14], p = .571). The lie type factor showed a significant effect (b = .65, SE = .22, t[980] = 3.01, 95% CI [.23, 1.08], p = .003), showing that intention ratings are much higher for white lies than black lies. The interaction of language and lie did not reach significance (b = .11, SE = .06, t[980] = 1.88, 95% CI [−.01, .23], p = .061), but it exhibited a trend of a reduced difference in intentions ratings between black and white lies in the foreign language compared to the native language (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pirate plot of the intention to tell black and white lies in native and foreign languages in experiment 2. The horizontal ticks (-) represent individual raw data points; the “bean” shape indicates the data density; the solid line represents the mean; the rectangular boxes represent the Bayesian highest density interval.

2.2.4. Discussion

The general pattern of the FLE in experiment 2 was similar to that of experiment 1. More specifically, the intention to tell black lies was higher in the foreign language than in the native language, while for white lies the difference was not so apparent, though there was a slight reduction of intention in the foreign language condition. One explanation as to why the effect of language was significant in acceptability but not in intention was that these two ratings measure different social norms, i.e., descriptive norms and subjective norms, respectively. Descriptive social norms represent the prevailing behavioral standards perceived as appropriate by the majority of society, while subjective social norms regulate the attitudes regarding the behaviors of oneself (Costenbader et al., Reference Costenbader, Lenzi, Hershow, Ashburn and McCarraher2017; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Hong, Chiu and Liu2015). The results from experiments 1 and 2 suggest that while a foreign language can significantly diminish the impact of descriptive norms in perceiving the lies told by other people, its impact on subjective norms used to tell lies by themselves may not be so strong. These results corroborate the notion that the descriptive norms are more external and impersonal, being more subject to contextual changes such as language, whereas subjective norms are more robust as they are more internalized and personal (Kwan et al., Reference Kwan, Yap and Chiu2015; Muldoon et al., Reference Muldoon, Lisciandra, Bicchieri, Hartmann and Sprenger2014). Though it is important to recognize that subjective norms, or personal norms in broader terms, develop from descriptive social norms, usually through socialization in early childhood (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1973, Reference Schwartz1977). In fact, some argue that descriptive norms can be a minor contributor to intention alongside subjective norms (Manning, Reference Manning2009; Rivis & Sheeran, Reference Rivis and Sheeran2003). This might explain why the patterns of results of experiments 1 and 2 are highly similar, even though the interaction was not significant in experiment 2.

Additionally, these results were congruent with a recent study on lying in a foreign language that showed increased social acceptability of black lies but not in actual behavior in having them tell them (Alempaki et al., Reference Alempaki, Doğan and Yang2021). Another explanation for the null interaction between language and type of lie could be due to the influence of additional factors contributing to actual decisions, such as belief of controlled behavior (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen2002) and personal involvement (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Cushman, Stewart, Lowenberg, Nystrom and Cohen2009). These individual differences might have influenced subjective norms in determining the intention ratings. Although we did not specifically measure the individual differences such as perceived behavioral control, we statistically addressed these differences by inserting individual participants as a random predictor in the mixed-effects linear model. Therefore, we argue that it is unlikely that the results of experimental 2 are induced by individual differences. In sum, the results in experiments 1 and 2 suggest that although a foreign language seems to impact social norms overall, this effect can be more evident in descriptive norms than subjective norms.

Notwithstanding the revealing findings from experiments 1 2 regarding the impact of a foreign language on social norms, there were at least three limitations that need to be addressed. Initially, we hypothesized that the use of a foreign language would diminish the influence of social norms regardless of affective polarity, and we tested this by measuring the difference of black and white lies. However, given the nature of black and white lies, these scenarios differed in terms of the underlying factors that lead to their distinction, such as the motivation, the beneficiary, the social context, the relationship between the protagonists, etc. Due to the intrinsic differences between black lies and white lies, other than different affective values, they are fundamentally different scenarios. To strengthen the hypothesis that the influence of social norms is reduced in a foreign language, it was more suitable to examine the difference between two conditions of the same scenario. For example, telling white lies and telling blunt truths can be the two sides of the same coin: adhering to social norms, i.e., telling a white lie, versus violating social norms, i.e., telling blunt truths. Therefore, if a foreign language consistently modulates descriptive norms, we should expect to see an attenuation of the divide in social acceptability between norm-violating behaviors and norm-adhering behaviors. Secondly, the inclusion of only a limited sample of black and white lie scenarios used in previous studies may raise concerns about the validity and generalizability of our findings. To establish a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon, it is necessary to investigate a wider range of scenarios in the participants’ cultural context to provide more ecological validity. And thirdly, the adoption of an 8-point Likert scale in measuring the dependent variable can have limited precision in differentiating responses and sensitivity to the subtle shifts in participant opinions. To overcome these limitations, we implemented experiment 3.

2.3. Experiment 3: the acceptability of telling white lies and telling blunt truths in native and foreign languages

2.3.1. Design and materials

By addressing the limitations, experiment 3 conceptually replicated experiment 1. We made several changes to the materials. Firstly, we expanded the set of lie scenarios from 12 in experiment 1 to 20 scenarios in experiment 3, sampling from previous studies (Cantarero et al., Reference Cantarero, Szarota, Stamkou, Navas and Dominguez Espinosa2018; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Casado and Martín-Loeches2016). Secondly, we created a truth-telling version for each of the lie scenarios, where instead of telling lies, the protagonist speaks frankly and tells truths. Then, four counterbalanced groups were constructed out of these scenarios, with each counterbalance group containing 10 different scenarios of lie-telling and 10 different scenarios of truth-telling. Thirdly, the participants provided their responses on a slider scale ranging from 0 to 100. Finally, we strictly followed the language adaptation process of the PSA (https://psysciacc.org/translation-process/) to make sure there was no confusion in the scenarios (see Table 1 for example scenarios and Supplementary materials). In experiment 3, we measured the acceptability of behavior of the deceiver in the scenarios as the dependent variable. We took the difference in acceptability ratings between norm-violating and norm-adhering behaviors as a reflection of the strength of descriptive norms. The experiment was implemented on Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com/).

2.3.2. Participants and procedure

We recruited 104 participants that had not previously participated in experiments 1 and 2 via Prolific. The participants in experiment 3 all reported being only monocultural Italian nationals born and raised in Italy, with Italian as the native language and English as a foreign language, who had no immigration background nor experience living abroad (see Table 2 for the participant details).

We emulated the experimental procedure from Hayakawa et al. (Reference Hayakawa, Tannenbaum, Costa, Corey and Keysar2017). The participant was randomly assigned to complete the experiment in either their native language or the foreign language in one of the counterbalanced groups. They consented to their participation after reading a brief description of the experiment. The instruction was in the native language only if they were assigned to the native language condition and bilingual for the foreign language group. The adoption of bilingual instructions in the foreign language condition was to make sure the participants could fully understand the task. First, they completed a text comprehension test in either their native or foreign language, congruent with the experimental language. After that, the participants were presented with 20 scenarios (Helvetica font, size 14, and black color in bold). Their task was to indicate the acceptability of the behavior of the protagonist in each scenario on a slider ranging from 0 (not at all acceptable) to 100 (completely acceptable) with the starting position at 50. They clicked the arrow button at the bottom right corner of the screen to continue. After the main task, they completed another comprehension test in the other experimental language. Finally, they reported the difficulty of the experiment, and then answered a standard set of demographic and linguistic background questions. The entire experiment lasted about 10 min.

Considering the inherent limitations associated with online surveys, we recognized the need to apply more rigorous criteria in the selection of eligible participants. Since the participants could leave and come back to the Qualtrics survey anytime they wanted, based on the average completion time of 10 min, we set up upper and lower thresholds for the duration of the experiment as 16 and 4 min, respectively. This removed 12 ineligible participants. Another issue concerning the data collected via online surveys using a 100-point slider is response bias, i.e., extreme responding (Meisenberg & Williams, Reference Meisenberg and Williams2008; Paulhus, Reference Paulhus1991) and midpoint responding (Garland, Reference Garland1991; Weems & Onwuegbuzie, Reference Weems and Onwuegbuzie2001). To overcome these issues in the data, we removed three participants that showed either extremely high variability in their responses (SD > 80) or extremely low variability in their responses (SD < 20). Hence, we performed the main analyses on the data of the remaining 89 participants (Mage = 28.60, SD = 8.46, 46 females). Out of these participants, 45 were in the foreign language condition and 44 in the native language condition. Although the participants generally reported the experiment to be more difficult in the foreign language (M = 30.67, SD = 23.64) than in the native language (M = 21.32, SD = 17.01, t[1634] = 9.59, 95% CI [7.44, 11.26], p < 0.001), the eligible participants all responded correctly to the before and after text comprehension tests. They also did not differ in self-reported English proficiency (t[1689] = .404, 95% CI [−.88, 1.34], p = 0.69), with high proficiency (on a slider scale from 0 to 100, with 100 being the highest) in both the foreign language group (M = 80.94, SD = 10.60) and the native language group (M = 80.72, SD = 13.09). The collection of these results suggests that even though the participants perceived the experiment to be more challenging in the foreign language, they had no problem understanding it.

2.3.3. Analyses and results

To select white lies, we extracted the data of all the lie-telling scenarios in the native language as normative data. For this experiment, we considered the 10 most acceptable lies as white lies. The main analyses were thus performed by comparing these scenarios of telling white lies with their counterparts, i.e., the same scenarios but telling blunt truths. The statistical approach was analogous to experiments 1 and 2: the model included the fixed factors of language (native vs. foreign), content (lie-telling vs. truth-telling), and the interaction between the two factors. All factors were Helmert coded. Random intercepts for participants and scenarios were included in the model.

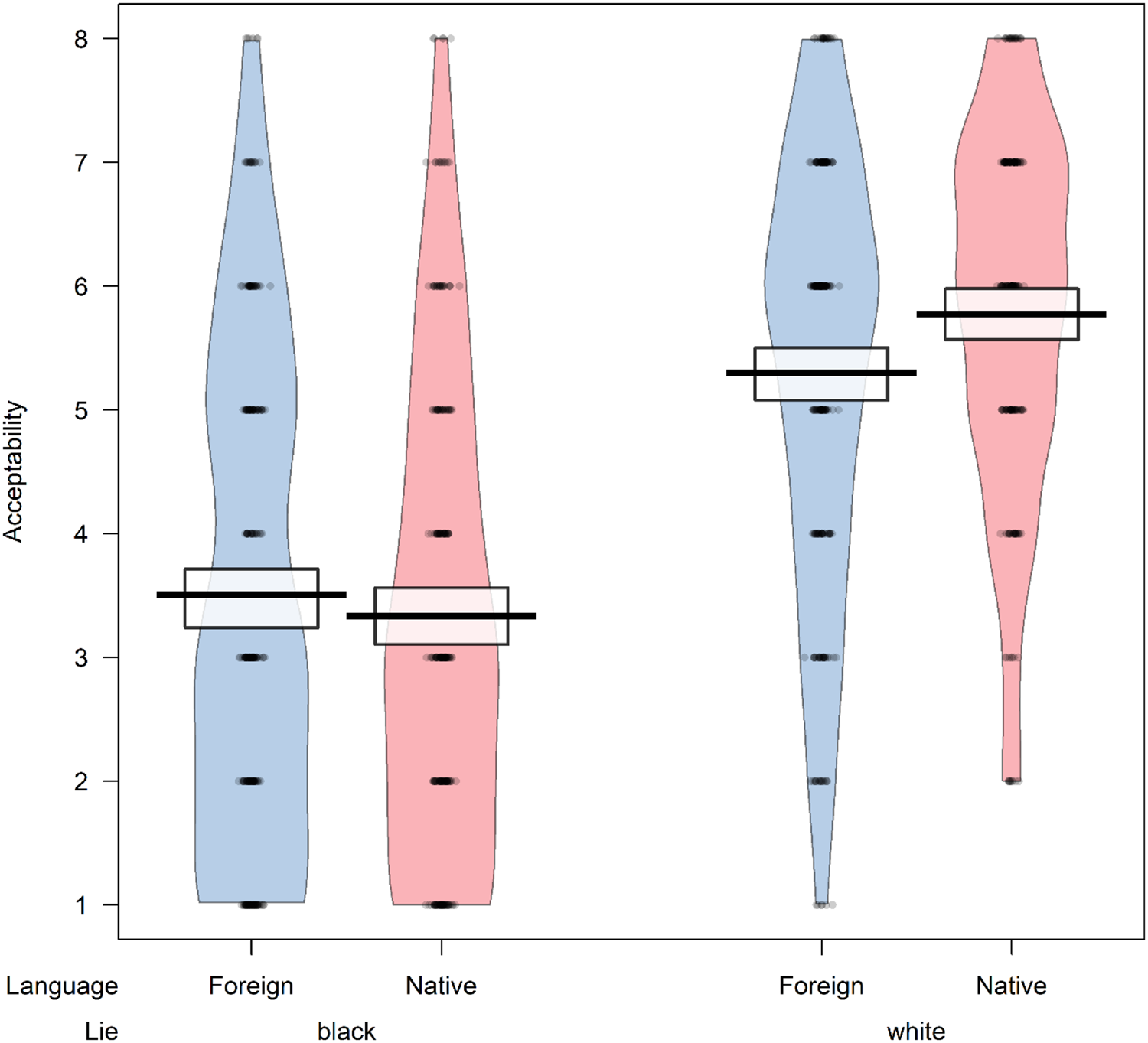

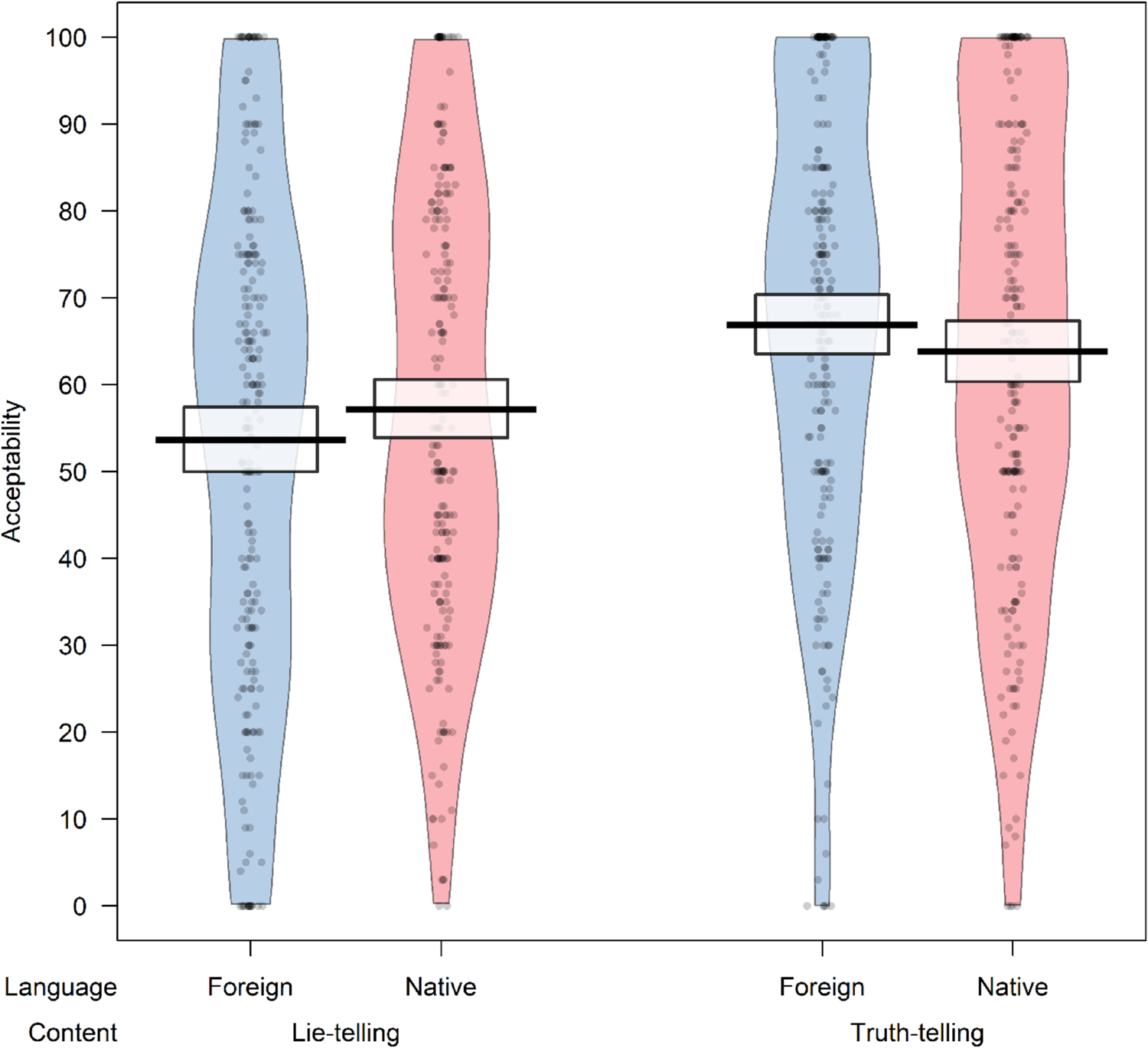

The results showed that the main effect of language was not significant (b = .12, SE = 1.00, t[886] = .12, 95% CI [−1.84, 2.08], p = .906). The factor content showed a significant effect (b = 4.92, SE = .83, t[886] = 5.97, 95% CI [3.30, 6.54], p < .001), indicating higher responses for (blunt) truth-telling compared to (white) lie-telling scenarios. Importantly, the interaction between language and content was significant (b = −1.68, SE = .83, t[886] = −2.03, 95% CI [−3.30, −.06], p = .042). More specifically, while telling white lies was considered less acceptable in the foreign language (M = 53.63, SD = 28.94) than the native language (M = 57.15, SD = 25.85), telling the blunt truths was considered more acceptable in the foreign language (M = 66.89, SD = 25.76) than in the native language (M = 63.83, SD = 26.95) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pirate plot of the acceptability of (white) lie-telling and (blunt) truth-telling scenarios in native and foreign languages in experiment 3. The jitters represent individual raw data points; the “bean” shape indicates the data density; the solid line represents the mean; the rectangular boxes represent the Bayesian highest density interval.

2.3.4. Discussion

In experiment 3, we specifically tested the norm-adhering behavior and norm-violating behavior of the same scenarios, i.e., telling white lies versus telling blunt truths. We predicted a diminution of the divide in social acceptability between telling white lies and telling blunt truths. The results showed that people generally considered the truth-telling versions of the same scenario more acceptable than the white lie-telling versions. This could be that truth telling is generally more acceptable than lie telling even though in some cases it means violating social norms, as telling the truth is the default response in the human brain (Verschuere et al., Reference Verschuere, Spruyt, Meijer and Otgaar2011). However, it is important to notice that this divide between telling white lies and the blunt truth was much smaller compared to the divide between telling black lies and white lies, observed in experiments 1 and 2. Critically, the results clearly showed a cross-interaction of content by language, indicating that a foreign language modulated the acceptability of norm regulated behaviors of telling white lies versus telling blunt truths. More specifically, while norm-adhering behavior, i.e., telling white lies, can be judged less favorably in the foreign language, norm-violating behavior, i.e., telling blunt truths, can be judged more favorably. This result is consistent with those found in experiment 1, that is, while normally adhering behaviors (telling white lies) were judged as less acceptable in the foreign language, norm-violating behaviors, i.e., telling black lies, were judged as more acceptable. We believe these results further strengthen the hypothesis that a foreign language impacts social norms, particularly descriptive norms.

Building on the findings from the previous experiments demonstrated that a foreign language attenuates the influence of descriptive social norms that regulate lie acceptability. In experiment 4, we explored further the effect of a foreign language on social norms could have an impact in the decision-making domain. Several previous studies have only examined telling black lies in native and foreign languages. For example, it was found that the proportion of lies was significantly lower when expressed in a foreign language compared to a native language, potentially due to reduced negative affect associated with black lies (Bereby-Meyer et al., Reference Bereby-Meyer, Hayakawa, Shalvi, Corey, Costa and Keysar2020; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Li and Li2021). However, Duñabeitia and Costa (Reference Duñabeitia and Costa2015) showed that the cognitive load of producing false statements is similar in both foreign and native languages, challenging the idea that lying is more demanding in a non-native language. Their study, using a picture naming task where participants lied or told the truth, found that foreign language and deception independently increased cognitive load, indicated by larger pupil dilations and longer voice onset latencies in false statements. However, these factors did not interact, indicating separate processing demands for language and deception. Thus, it is hard to draw conclusions from these studies on whether a foreign language affects lying decisions by impacting social norms.

The results from experiments 1 and 3 indicate that a foreign language can significantly affect the strength of descriptive norms, and the results from experiment 2 suggest that the impact of a foreign language on subjective norms may be less pronounced. Given that intention is the direct antecedent of behavior (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen, Kuhl and Beckmann1985, Reference Ajzen1991, Reference Ajzen2011), we expected to observe a similar modulating effect of foreign language in modulating the lying decisions for black and white lies. More specifically, we predicted that people would be more likely to choose to tell white lies than black lies; however, this difference would be attenuated in the foreign language compared to the native language.

2.4. Experiment 4: lying decisions in the native and foreign languages

2.4.1. Design and materials

We adapted the 20 lie-telling scenarios used in experiment 3 for experiment 4 by using a forced choice decision paradigm. The 10 scenarios with the lowest acceptability according to the normative data in experiment 3 were coded as black lies, whereas the 10 scenarios with the highest acceptability were coded as white lies (see Table 1 for example scenarios and Supplementary materials for the complete set). In experiment 4, the participants themselves were protagonists in the scenarios and they decided whether to tell a lie after reading a description of social interaction. In experiment 4, we measured the participants' decisions as the dependent variable, while maintaining the independent variables of language and lie type. The experiment was implemented on Labvanced.

2.4.2. Participants and procedure

One hundred and three adult Italian native speakers (Mage = 29.32, SD = 6.44, 52 females), who had not participated in the previous three experiments, were recruited in experiment 4 via the crowdsourcing platform Prolific. They all reported to be currently residing in Italy and having Italian as their native language (see Table 2 for the participant details) and English as a fluent second language. Two-sample t tests for linguistic control variables between native and foreign language groups showed a significant difference for foreign language proficiency (t[2047] = 4.493, 95% CI [.18, .45], p < .001), with the participants reported slightly higher proficiency (on a Likert scale from 0 to 11, with 11 being the highest) in the foreign language after completing the experiment in the foreign language (M = 8.97, SD = 1.54) compared to in the native language (M = 8.66, SD = 1.63); and for foreign language exposure (t[2039.2] = 7.178, 95% CI [.44, .77], p < .001), with the participants reported slightly higher exposure to the foreign language after completing the experiment in the foreign language (M = 6.76, SD = 1.84) compared to in the native language (M = 6.16, SD = 1.99). Like in experiments 1 and 2, we took the increased self-reported foreign language proficiency in the foreign language group as an indication that participants had no problem understanding the scenarios in the foreign language and no further analysis regarding foreign language proficiency was performed.

The experimental procedure was akin to that of experiments 1 and 2. The participants first read a brief introduction to the experiment and proceeded only if they consented to participate. Afterwards, they were presented with the 20 scenarios one after another in random order. Each scenario appeared at the center of the computer screen (Lato font, size 16, black) and the participants' task was to click either the “Yes” button, i.e., tell such a lie, or the “No” button, i.e., not tell such a lie, below the scenarios. After selecting their choice, the next trial automatically began after 500 milliseconds. Finally, the participants completed the Italian version of the LEAP-Q questionnaire (Marian et al., Reference Marian, Blumenfeld and Kaushanskaya2007), regarding their demographic and linguistic background. The experiment lasted around 8 min.

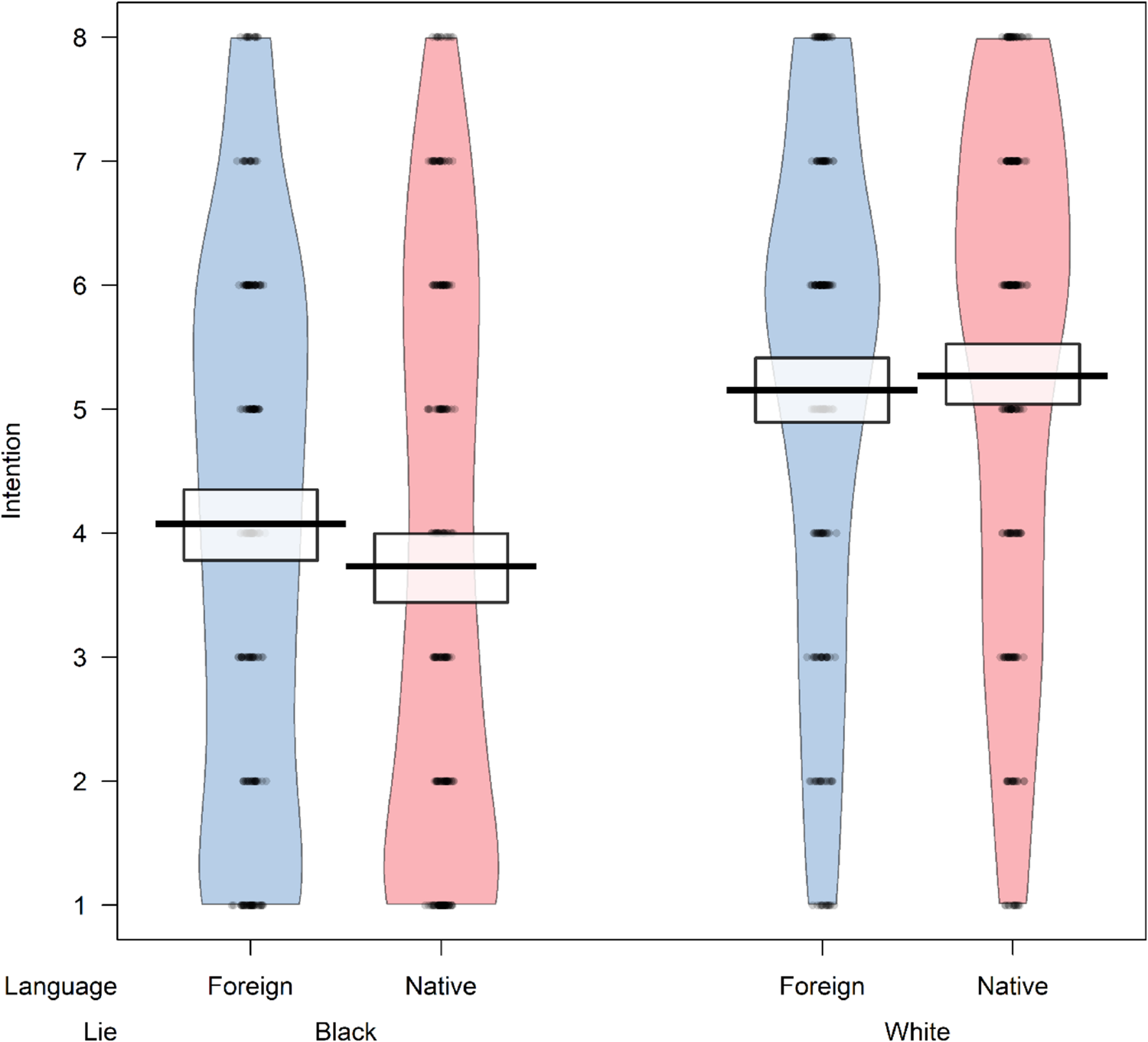

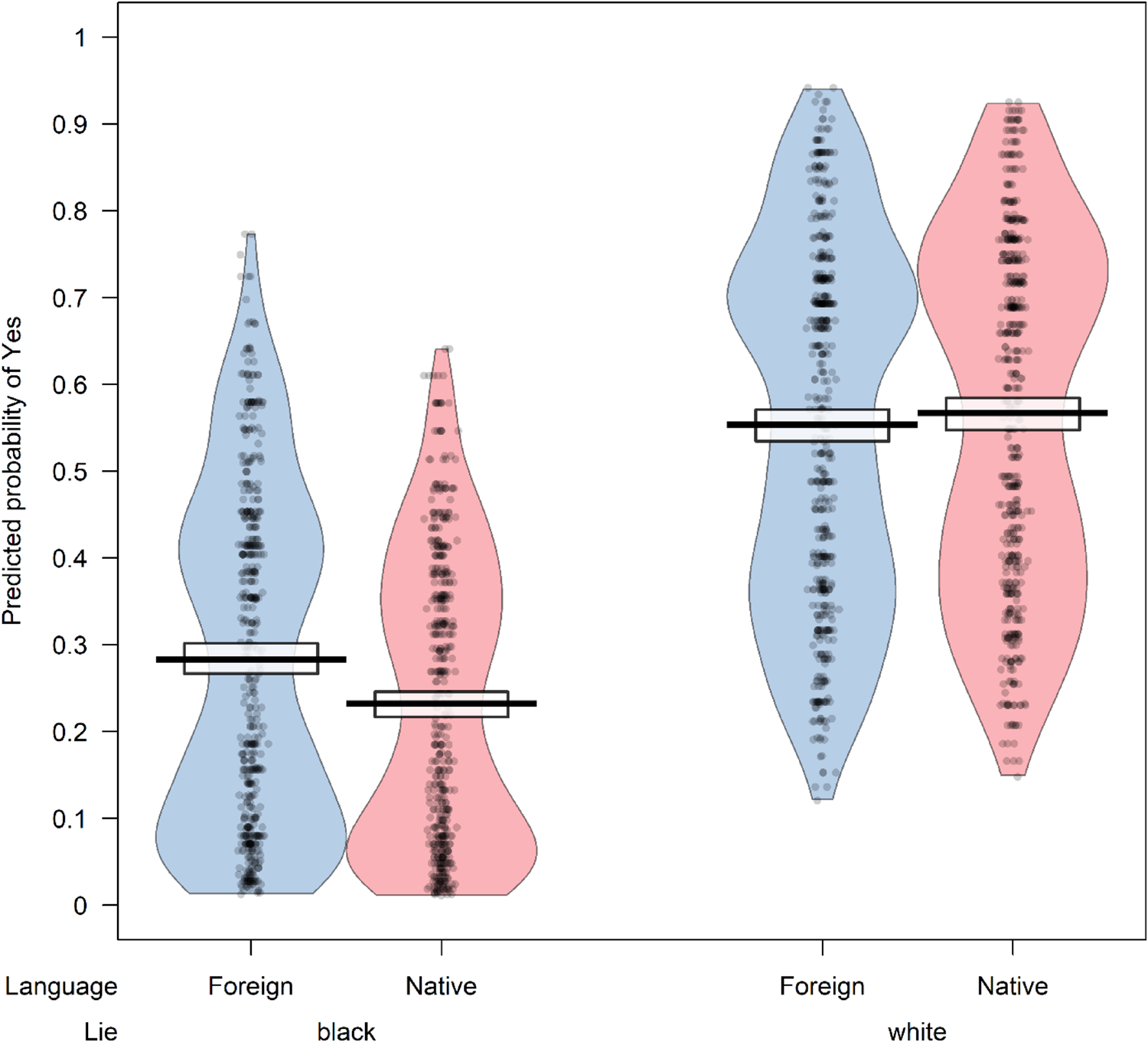

2.4.3. Analyses and results

Analysis was performed using a generalized linear mixed model with a binomial family and a logit link function to predict decision of lie-telling. We used fixed factors of lie (black vs. white), language (native vs. foreign), and the interaction between the two factors. Random intercepts for participants and scenarios were added to the model. The language factor did not reach statistical significance (OR = .94, 95% CI [.81, 1.08], p = .381). The factor of lie type showed a significant effect (OR = 2.43, 95% CI [1.45, 4.05], p = .001), meaning that participants were significantly more likely to tell a white lie than a black lie. The interaction between language and lie did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.10, 95% CI [.99, 1.22], p = .073), though it showed a trend that the difference in the probability to tell black lies and white lies could be reduced in the foreign language compared to the native language (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The predicted probability of yes decisions for black and white lies in the native and foreign languages in experiment 4. The jitter represents individual data points of predicted probability; the “bean” shape indicates the data density; the solid line represents the mean; the rectangular boxes represent the Bayesian highest density interval.

2.4.4. Discussion

In experiment 4, we further tested whether a foreign language could modulate subjective norms by measuring the decisions in telling black lies and white lies. In alignment with previous experiments, the results showed a significant divide between the decisions of telling black lies and white lies, that is, people were generally more likely to tell white lies than black lies. However, the modulation effect of a foreign language on this difference was not significant, consistent with the results in experiment 2 on subjective norms. Given that a foreign language does not significantly impact the subjective norms regulating intentions and that intentions are the direct antecedent of decisions, it is reasonable to conclude that a foreign language has limited impact on first-person decisions. Alternatively, it is possible that participants were subject to language-induced response biases when making dichotomous decisions. For example, a recent study found that people can show more acquiescence in a foreign language (vs. native) by providing more confirmatory responses (i.e., yay-saying), potentially due to decreased processing fluency (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Suitner and Navarrete2024). Such bias could have confounded the impact of foreign language on subjective norms in dichotomous decisions. Nevertheless, it is interesting to notice that the general pattern of results in experiment 4 is analogous to the patterns of previous experiments, i.e., an increased probability to tell norm-violating lies (black lies), but a decreased probability to tell norm-adhering lies (white lies) in the foreign language compared to native language. The combined results of the previous experiments suggest that although a foreign language modulates the regulatory power of descriptive norms on the perception of third-person behaviors, its modulation of subjective norms is less evident as showcased in first-person intentions and decisions.

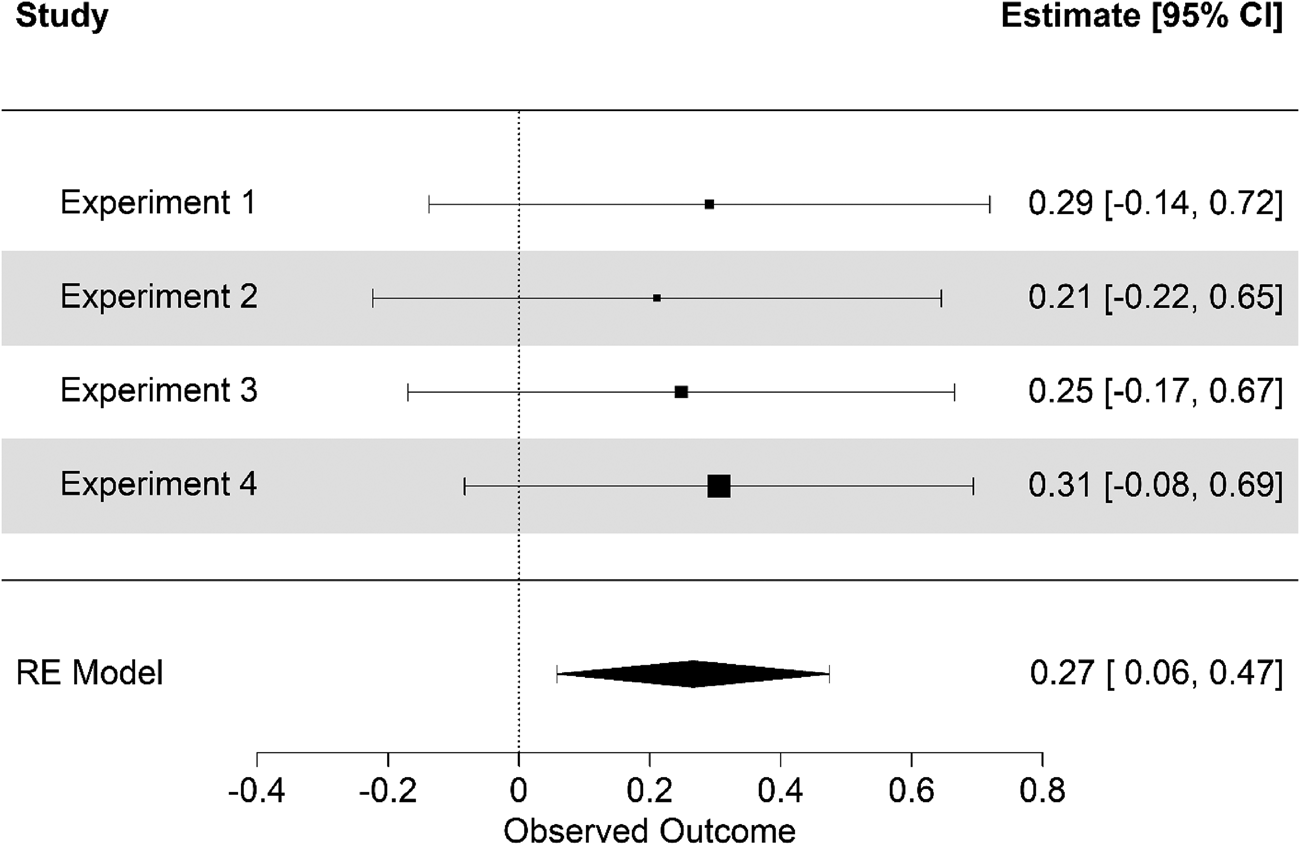

2.5. Meta-analysis

To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the reliability and generalizability of our findings, we conducted a random-effects meta-analysis to summarize the impact of a foreign language on social norms in the four experiments. For each experiment, we calculated the effect size and the associated variance of the interaction between condition and language, illustrated in Figure 5. The meta-analysis was performed using the function rma of the metafor package (Viechtbauer, Reference Viechtbauer2010) in R. The modulating effect of a foreign language in each experiment is represented as a square marking the effect size (Cohen's d) and its 95% CI. The diamond represents the overall effect size of the meta-analysis, and its 95% CI. The overall effect size was .2662, SE = .1061, z = 2.5079, 95% CI [.06, .47], p = .012, which is interpreted as a small effect (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). Notably, the magnitude of this effect size aligns with the findings of a recent meta-analysis conducted by Circi et al. (Reference Circi, Gatti, Russo and Vecchi2021) on the FLE in 38 moral decisions and 9 risk aversion experiments. Other meta-analyses on the FLE have yielded similar findings: Del Maschio et al. (Reference Del Maschio, Del Mauro, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2022) and Stankovic et al. (Reference Stankovic, Biedermann and Hamamura2022) reported an overall small effect size in their meta-analyses.

Figure 5. Forest plot of the meta-analysis of four experiments.

In conclusion, the meta-analysis solidifies the reliability of the results reported in the four experiments, reinforcing the notion that a foreign language diminishes social norms compared to the native language. Although the meta-analysis yielded a small effect, it is in alignment with what has been reported in the previous meta-analytical studies on the FLE. Furthermore, the consistent pattern in the results across our four experiments suggests that a foreign language can indeed nudge people's attitudes and beliefs regarding lies, and potentially people's intentions and decisions, underscoring the influence of language on social norms.

2.6. General discussion

In the current study, we conducted four experiments using lies to examine the role of a foreign language on social norms, distinguishing descriptive norms and subjective norms. Experiment 1 provided support for our hypothesis that a foreign language reduces descriptive norms by attenuating the difference in social acceptability between black lies and white lies. More specifically, while norm-violating lies (black lies) were judged more acceptable in a foreign language (vs. native language), norm-adhering lies (white lies) were judged less acceptable, indicating that the descriptive social norms regulating the difference are impacted in the foreign language context. We expanded on the hypothesis to subjective norms in experiment 2, which focused on individuals' first-person intentions to tell lies. While the modulation of a foreign language on intentions did not reach statistical significance, the overall pattern of the results highly resembled that from experiment 1. Experiment 3 aimed to replicate experiment 1 on the FLE on descriptive norms by comparing the acceptability of two versions of the same scenarios, namely, norm-adhering behavior (telling white lies) versus norm-violating behavior (telling blunt truths). Consistent with experiment 1, experiment 3 showed that while norm-adhering behaviors (telling white lies) were judged less acceptable in the foreign language than in the native language, norm-violating behaviors of the same scenarios (telling blunt truths) were judged more acceptable. Lastly, experiment 4 further explored the impact of foreign language on subjective norms in lying decisions. Like experiment 2, although such an effect was not statistically significant, the pattern of results showed high compatibility with previous results. In sum, the results of these four experiments provide evidence that a foreign language indeed impacts social norms. In particular, the significant results from experiments 1 and 3 indicate that a foreign language can mitigate the strength of descriptive norms in regulating the perception of third-person behaviors; and the null results from experiments 2 and 4 seem to suggest that subjective norms may remain relatively robust in a foreign language. Nonetheless, the overall similarity of the patterns of results could be explained by the fact that subjective norms are developed from descriptive norms through socialization (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1973, Reference Schwartz1977), we should therefore not interpret these results in isolation.

However, there is still some unclarity surrounding the mechanism underlying the FLE on social norms. One way to explain the effect is that sequential bilinguals store only one set of social norms in their mind, that is, social norms acquired in their native language and culture. As these norms are activated more frequently and retrieved more fluently in their native language to navigate social interactions (Trudgill, Reference Trudgill2000; Wagner & Hesson, Reference Wagner and Hesson2014), the FLE thus emerges from hampered access to the same set of social norms. An alternative explanationFootnote 1 for such an effect could be that sequential bilinguals, like bicultural simultaneous bilinguals (Ramírez-Esparza et al., Reference Ramírez-Esparza, Gosling, Benet-Martínez, Potter and Pennebaker2006), possess two sets of language-dependent cultural frames (Dylman & Zakrisson, Reference Dylman and Zakrisson2023), and they tend to align with the social norms of the language which they were immersed in during the test. For example, Ross et al. (Reference Ross, Xun and Wilson2002) reported that Chinese-English bilinguals were more inclined to activate and retrieve information linked to East-Asian culture when providing information in Chinese as opposed to English. Similarly, it was found that Hong Kong bilinguals seemed to rate themselves as more competent and conscientious when responding in English than in Chinese (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Lam, Buchtel and Bond2014). Although cultural frames and social norms differ in terms of scope and stability, it is still possible that sequential bilinguals form and store two sets of language-dependent social norms, and they may be prompted by the language of interaction to switch between the two sets of norms. Since culture, social norms, and language are very much interconnected (Etzioni, Reference Etzioni2000; Semin et al., Reference Semin, Fiedler and Fiedler1992), it remains challenging to ascertain whether monocultural sequential bilinguals mentally store two sets of language-dependent social norms, capable of switching between them, or they possessed a singular set of social norms acquired in their native, and that a foreign language merely influenced the level of activation of these norms. We encourage future research in this area to further elucidate and resolve this theoretical contention.

3. Conclusion

Our research adds to the burgeoning body of knowledge on the FLE. We contextualize our findings within recent theoretical frameworks suggesting that the use of a foreign language can impact social norms. Through a series of four experiments, we have provided further evidence on the influence of a foreign language on social norms, particularly in distinguishing descriptive norms from subjective norms. Our findings suggest that using a foreign language can mitigate the perceptual difference between norm-violating and norm-adhering behaviors, reflected by the attenuation of strength of subjective norms in evaluating third person lies. Tendentially, using foreign language can have a similar impact on subjective norms that regulate first-person behavioral intentions and decisions.

In sum, our study provides compelling evidence that a foreign language can impact social norms. Our findings carry important societal implications, especially in multilingual contexts, as we may not rely on the same set of social norms or rely on them to different degrees in interpreting others' behaviors and guiding our own behaviors. We do not contend that there is a fundamental alteration in our cognitive processes when utilizing a foreign language. However, we believe it is imperative to acknowledge and understand the nuanced psychological variances when communicating in a non-native language. Our research is by no means definitive regarding the influence of a foreign language on social norms. We recognize the constraints of the methodology to disentangle the underlying mechanism for such effects. Future investigations should expand our findings by examining different social interactions, broadening participant demographics, and assessing variations across languages. This will allow us to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the FLE and its implications for social cognition and human behavior.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728924000373.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at osf.io/dz3j8.

Acknowledgements

Z. H. is supported by a PhD grant from the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Padova e Rovigo.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.