Introduction

The evolving relationship between national and supranational spheres, and the progressive intertwining of these two political arenas, represents a topical subject of political-scientific analysis. Since 2008, numerous crises have deeply affected the European Union (EU), leading to a reassessment of the degree of interconnection among EU member states, and at the same time revealing deep frictions and tensions that until 2008 had remained latent. The success of the Eurosceptic parties at the 2014 and 2019 European elections marked a new phase both in the relationship between national governments and European institutions, and in the public narrative concerning the EU, especially with regard to its influence on member states. The last 10 years have been characterized by heated debate and clashes regarding the future of European integration, and the very meaning of this political process (Milkin, Reference Milkin2014; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b).

In this context, Italy can claim to be unique since historically it boasts a lengthy pro-European tradition both at élite-level and among the voting public. This unique condition is characterized by the fact that citizens' trust in EU institutions has always been associated with a low degree of trust in the country's own political institutions (Isernia, Reference Isernia, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005); this lends support to the argument that the external constraint has exerted a prominent role in the trajectory of the Second Republic, ‘saving’ the country from a period of political/institutional and economic uncertainties (Ferrera and Gualmini, Reference Ferrera and Gualmini2004; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011; Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo, Della Sala, Magone, Laffan and Schwerger2016b). However, also Italy has witnessed an increase in the number of parties that, in terms of both political programme and public discourse, have adopted a position that has oscillated between Euro-criticism and genuine Euro-scepticism (Conti, Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017), as the result of the public's growing negativity towards the EU (Di Mauro, Reference Di Mauro2014).

From this point of view, the effort to map the evolution of parties and of public attitudes towards the EU is a strategic task that permits us to understand the intensity and direction of this oscillating tendency. This is why it may be interesting to take into account not only the evolution of the political stances on Europe expressed by party leaders, but also those of a prominent institutional figure like the Italian Prime Minister (PM). This could further our understanding of how, in recent years, this institutional figure has become entangled in a scenario which on the one hand has seen a cooling off of pro-European momentum, and a focus on the importance of EU membership on the other.

How does the PM, Italy's most important institutional representative within the EU political system, publicly present the evolution of the relationship between Italy and the EU? Have there been changes in the PM's position in this regard over time? What different categories/themes engaged by PMs have emerged in their discourses? Is it possible to detect some sort of refusal of the conditionality mechanism that has characterized EU policy making and influence since 2011 (Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2015)?

In order to identify variations and regularities in the approach of Italy's PMs towards the EU and the integration process (the greater or lesser degree of conflict with such), an empirical analysis of PMs' speeches from 1994 to 2019 will be conducted. This new research, which is part of a well-established tradition of analyses focusing on national elites' narrative regarding the EU and the integration process as a whole (Conti and Verzichelli, Reference Conti, Verzichelli, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005; Conti, Reference Conti, Best, Lengyel and Verzichelli2012; Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a), could help us get a better understanding of the relationship between member countries and the Union. It should facilitate our understanding of changes and regularities, and help us identify the conditions of crisis and of the conflict with the supranational level, through the study of the political language used in this regard.

I would expect the empirical analysis to confirm a significant variation in the approach adopted by PMs in the aftermath of economic crisis, towards a more adversarial stance, thus showing how the worsening of the economic situation has acted as a powerful trigger for negative attitudes towards the EU, both at elite level and among the general public (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011; Di Mauro, Reference Di Mauro2014; Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015).

Furthermore, this analysis may shed some light on the connection between a PM and his/her parliamentary majority: that is, in the case of a majority with a positive attitude to European integration, do the PM's statements reflect a more pro-EU stance? Vice-versa, does harsh criticism of the EU in a PM's discourse correspond to a more Eurosceptic parliamentary majority?

The originality of this study lies in the fact that it does not focus on the positions of individual parties or party leaders, but on the speeches of the PMs at the institutional level; this is done through the adoption of a mixed methodology (qualitative–quantitative content analysis) designed to establish how heads of government see their own evolving political position regarding the European integration process. Should such variations be identified, the research will highlight the ‘direction’ of such changes, using language as a fundamental tool in order to understand how PMs have responded to the increasing criticism of European integration.

In choosing to analyse PMs' parliamentary speeches, whilst at the same time using the literature on party positioning in regard to the EU as part of the framework, I am aware that I am taking something of a risk, since not all those Italian PMs taken into consideration are party leaders (or even party members). Despite this risk, I value this analysis as an interesting new approach, for the very reason that it focuses on institutional leaders rather than on party leaders.

The current study is organized as follows: the first part examines the main features of the evolution of relations between Italy's political elites and the European integration project. The second part presents the methodology and data used, while the last part discusses the findings and draws a number of conclusions.

The Italian political elites and Europe

Despite the emergence, in the 1990s, of Euro-scepticism, during the nation's so-called Second Republic, Italy's political elites were perceived as substantially supportive of the European integration process, and in perfect keeping with the legacy of pro-European feelings that had characterized the governing parties during the First Republic (Isernia, Reference Isernia, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005; Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo, Della Sala, Magone, Laffan and Schwerger2016b). Over the last decade, however, this attitude has significantly mutated, with the emergence of a much more varied range of political parties standing for election, including successful parties and movements characterized by Eurosceptic stances. These emergent actors have transformed the European issue into a salient theme, and one that has been accompanied by a considerable restructuring of the political spectrum, with new or transformed forces aiming to win the support of those voters most critical towards the EU (Di Mauro, Reference Di Mauro2014; Di Mauro and Memoli, Reference Di Mauro and Memoli2016; Conti, Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017).

To map this evolution, Brunazzo and Della Sala (Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a: 116) have proposed a three-stage scan of how parties have established their positions on European integration over the course of time. The first phase concerns the period from the 1950s to the early 1970s, when the Christian Democrats and other governing parties actively supported the integration process (Conti and Verzichelli, Reference Conti, Verzichelli, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Szczerbiak and Taggart2008; Conti, Reference Conti, Best, Lengyel and Verzichelli2012) in order to guarantee the country growth and stability, as well as its anchorage to the liberal democratic West rather than to the Eastern communist bloc. The second phase ran from the turn of the 70s until the early 90s, and was characterized by an exponential growth in support for European integration, although during this period it featured – among the political elite – more celebratory, rhetorical tones (Conti and Verzichelli, Reference Conti, Verzichelli, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005). During this second period, the narrative moved from the theme of democratic anchoring to that of policy performance, that is to say, the opportunities for economic growth and modernization offered to Italy by its subscribing to the common European project; this was the external constraint capable of producing positive externalities despite a blocked national political system (Ferrera and Gualmini, Reference Ferrera and Gualmini2004; Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a). The third phase, on the other hand, coincided with the foundation of the Second Republic and the launching of the Maastricht Treaty. This was a political period characterized by the ‘rescued by Europe’ approach, according to which Italy was to implement a massive economic and social overhaul in order to satisfy the Maastricht criteria for membership of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) (Ferrera and Gualmini, Reference Ferrera and Gualmini2004). At the same time, this was the moment when a certain divergence emerged among Italy's political parties in regard to their narratives and attitudes concerning Europe.

During the second phase, the main governing parties – the Christian Democrats and the Socialists – despite their substantial Europeanism, began to display more variegated positions on the form of European integration. There were internal divisions which, as the First Republic came to an end to be succeeded by the Second Republic, clearly manifested themselves as intra-coalition divisions (Conti and Verzichelli, Reference Conti, Verzichelli, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005), with the emergence of different degrees of Europeanism both on the centre-left and the centre-right. Generally speaking, the third phase was characterized by the marked pro-Europeanism of the centre-left, which is in line with the general revision of the social-democratic positions in favour of European integration that began in the 1980s (Gabel and Hix, Reference Gabel and Hix2002); this contrasted with the more lukewarm positions adopted on the centre-right (Conti and Verzichelli, Reference Conti, Verzichelli, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005; Conti, Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017). The element uniting the latter two phases is therefore a less enthusiastic, more complex involvement of Italy's political elites in the integration process (Conti and Verzichelli, Reference Conti, Verzichelli, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005). This state of affairs was the long-term result of Italy's shift in position, from being one of the leading players in the integration process, to being part of the support cast located on the periphery of the European system (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo, Della Sala, Magone, Laffan and Schwerger2016b).

The third phase is the one characterized by a greater degree of oscillation in the way that Europe is viewed. While a substantially positive judgement of the integration process was widespread among those coalitions competing for the government of the country up until 2013, in recent years, critical voices have emerged within the political spectrum (especially on the centre-right) in regard to issues such as the functioning of EU institutions; the fact that some policy decisions taken at a supranational level could damage Italy; the role of the Euro; and the EU's power to interfere in the country's democratic life (Bellucci, Reference Bellucci, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005).

From the mid-1990s onwards, there was a growing wave of criticism against the EU culminating in the 2008 crisis. The EU suddenly became a strongly politicized issue utilized within the framework of the inter-party competition, in a process of transformation of Italy's party system (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a).

From this point of view, the attitude of the Italian political elite was ambivalent since, as Conti (Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017) mentions, on the one hand, there was the will to maximize consensus during the electoral phase by intercepting the new Eurosceptic stance of the electorate, while at the same time, politicians acting within institutions adopted a pragmatic approach to the EU. This latter aspect can be ascribed to parties' awareness – when in government – of EU power in terms of ties and conditionality. The question is: can this general positivity towards the EU outside the electoral competition, on the part of the Italian political elite, still be found? (Conti, Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017).

As Brunazzo and Della Sala (Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a) point out, the conflict over the EU has been taking place in a political context characterized by certain specific, contrasting narratives permeating the Italian public debate on Europe: (a) the EU is still seen as an instrument with which to strengthen the Italian position and protect its interests; (b) the more openly Euro-sceptical approach of the Lega Nord (Northern League – LN), which in its new nationalist, non-regionalist version (Albertazzi et al., Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018), identifies the issue of EU interference (the single currency, constraints, etc.) as detrimental to the country as a whole (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Iltanen and Kritzinger2004; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Szczerbiak and Taggart2008; Albertazzi et al., Reference Albertazzi, Giovannini and Seddone2018); (c) the Euro-pragmatic approach that puts the emphasis on the centrality of national interests, but affirms that such should be pursued within, and not against, the EU (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo, Della Sala, Harmsen and Schild2011).

In addition to the previous three positions on the EU, a fourth, more recent position is that of new party actors that have recently appeared on the Italian political scene – such as the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement – M5S) – which we could classify as among those adopting the Euro-critical approach (Salvati, Reference Salvati2019a). From their point of view, European integration is pursued as an asset, a potentially positive constraint, but in order to do so, the political structure of the EU must be radically challenged, and the EU's decision-making models and its priorities require reforming.

In this fragmented scenario, Italian party-based Euro-scepticism has taken on a variety of different hues over the years, moving from being an ideological stance to a more strategic one, varying in relation to the public's Euro-scepticism (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011). Indeed, over the years Italian electors have displayed a relatively significant – but not majoritarian – degree of Euro-scepticism, as a result of strong concerns about the economic situation or about the direct impact of EU polices on domestic economic performance (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011; Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015). This shows the important influence of the economic variable on people's positions regarding the EU.

The critical shift in the positions adopted by Italy's political elites, and the emergence of several different stances on the EU, can be accounted for by the need to provide a fresh response to citizens' changing attitudes towards the integration process (Conti, Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017). The decline in enthusiasm about the Euro among the Italian public appears to be above all the product of the changed economic context: the worsening of individual material conditions, as variously interpreted by Italy's governing/leading politicians, has contributed towards increasing the perceived gap between citizens and EU institutions, thus fostering greater hostility/distrust towards the EU (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011; Serricchio et al., Reference Serricchio, Tsakatika and Quaglia2013; Di Mauro, Reference Di Mauro2014; Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015; Bellucci and Serricchio, Reference Bellucci, Serricchio, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017). This detachment has been increased by the perception of a political/institutional system such as that of the EU, which is too far removed from citizens, and above all is affected by a high degree of de-politicization, in virtue of a technocratic asset built around the dominance of non-majoritarian institutions (Van Spanje and de Vreese, Reference Van Spanje and de Vreese2011; Mair Reference Mair2013; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b).

As soon as the economic crisis exacerbated this sense of detachment from the EU, populist and Eurosceptic parties were afforded the room they needed to propose ‘alternative’ political platforms to the pro-European narrative of the mainstream parties and elites that had governed over the previous 20 years, and that now found themselves vulnerable to the new electoral volatility (Cotta, Reference Cotta2018). This room for manoeuvre afforded to the right-wing, to radical left-wing parties, and to parties on the periphery of the party system has been amplified by the consequences of the economic recession, which has accelerated the destabilization of traditional party systems (Di Mauro, Reference Di Mauro2014; Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016).

To this end, an analysis of PMs' speeches can further our understanding of the variations or continuity in question and, as Conti suggests (Reference Conti, Pasquinucci and Verzichelli2017), helps us ascertain whether a positive approach to European integration continues to characterize institutional public speeches or not.

Methodology

Discourse analysis has gained ground as a methodological approach also in European studies, for the fact that it can be performed in regard to almost all topics concerning the process of EU integration (institutional functioning, the emergence of a European public sphere, the definition of the European polity, EU public policy formation), even though certain limitations in terms of its effectiveness are still present (Crespy, Reference Crespy, Lynggaard, Manners and Löfgren2015; Pansardi and Battegazzorre, Reference Pansardi and Battegazzorre2018). The methodology applied in this study represents a novel approach consisting of a qualitative content analysis of the evaluative aspects of PMs' parliamentary speeches. This analysis concerns the evaluation that Italian leaders give of the EU integration process and of its impact on Italian democracy.

This approach directly stems from Lasswell's theory, whereby politics are seen as a power process involving the production and distribution of values in a society and connecting two actors: the elite – who control the majority of these values – and the masses – who only possess a residual part of these values (Battegazzorre, Reference Battegazzorre and Rositi2013). According to Lasswell, political discourse is an instrument of political control, and for this reason he interprets symbols – which are mainly expressed through political language – as a power resource controlled by the elite with the aim of protecting their own position. This methodology, unlike more quantitative approaches, permits the identification of those symbols that may trigger individuals' emotions and thus encourage forms of conformity that are in the interests of the elite (Battegazzorre, Reference Battegazzorre and Rositi2013).

In order to achieve this goal, the present analysis focuses ‘on evaluative aspects of the speeches, (…) not paying attention on signifiers (single “words”) but rather focusing on signified, on meanings’ (Pansardi and Battegazzorre, Reference Pansardi and Battegazzorre2018: 859). For this purpose, the coding unit is the symbol, a syntagm that both denotes and evaluates – positively or negatively – particular features of a political system (Fedel, Reference Fedel1999; Pansardi and Battegazzorre, Reference Pansardi and Battegazzorre2018). This methodology enables us to focus not only on individual symbols (and consequently to avoid the mere ‘counting’ of those symbols), but also on the larger argumentative structure of which the symbol is a part (Pansardi and Battegazzorre, Reference Pansardi and Battegazzorre2018). This larger structure is identified by the so-called clusters of symbols representing the sealed argumentative unit in which groups of symbols are located (Pansardi and Battegazzorre, Reference Pansardi and Battegazzorre2016).

This type of qualitative content analysis represents a mixed-method approach involving both qualitative and quantitative aspects. The identification and categorization of symbols constitute the qualitative part, while the quantitative aspect concerns the measuring of the frequency with which symbols and clusters of symbols recur.

The analysis is based on a codebook permitting the identification, in terms of positive or negative symbols, of all references to the constitutive elements of a political system made by the speaker (Pansardi and Battegazzorre, Reference Pansardi and Battegazzorre2018; Cremonesi and Salvati, Reference Cremonesi and Salvati2019). Every time one of those elements is the subject of positive or negative appraisal, it becomes a codified signified unit and is counted by hand in order to map the argumentation's key elements. In this study inter-code reliability, established using NVivo software, showed a satisfactory degree of agreement between the two measurements (i.e. the K-α coefficient is higher than 0.86).

The grid (Table 1) is organized into three macro-categories embracing the following respective symbols: (a) polity symbols, concerning the general elements of a political system, (b) politics symbols, concerning the political/electoral competition and relations among parties in the electoral and institutional arenas, (c) policy symbols, which refer to the policy-making process. Each of these three categories is sub-divided into different categories classifying the various symbols.

Table 1. The coding of EU references: symbols categories

The collected data are the result of a longitudinal study of PMs' official speeches. The analysed speeches have been chosen according to their relevance, and to the opportunity they give of identifying an expression of the speakers' clear (unmediated) positions in regard to the EU. These speeches are of two types: (a) programmatic statements made on the occasion of a vote of confidence to the government (for all PMs); and (b) official statements on issues directly concerning the EU, or specifically concerning the European Council's activities. The second category groups together all those speeches whose main topic is the EU institutional features; its role, its policy production, and the relationship between Italy (and its government) and the EU institutions (including issues like the enlargement of the EU, the review of treaties, the Italian economic situation in relation to EU policies and the EMU, specific decisions made by the European Council, and so on).

The sample is composed of 58 speeches given during the period from May 1994 (Berlusconi I Government) to September 2019 (Conte II Government), and the distribution among individual PMs is shown in Table 2. The number of speeches increases from Monti's Government onwards due to the fact that with the approval of Law 234 in 2012 concerning Italy's participation in the implementation of European legislation, the Government is now obliged to comply with new, more stringent obligations relating to disclosure to Parliament in regard to EU activities and policy making.

Table 2. General distribution of symbols

The analysis will be divided into two sections. In the first, the general findings of the content analysis for all the 58 discourses will be presented, so defining the big picture of the relationship between Italian governments and EU as presented by PMs. In the second section, a more specific temporal focus on the PMs' speeches after the breakthrough of the economic crisis will be introduced, in order to effectively enlighten if the multiple EU crises and the worsening of the economic/financial situation have represented a watershed.

Data analysis: general findings

The data in Table 2 offer a first interesting insight into the way in which different PMs have viewed the European theme: up to Letta's period in office, there was an overwhelming majority of positive symbols relating to EU topics; when Renzi was made PM, there was a sharp change in direction. At first glance, it would seem that the relationship is presented in a way independent of the EU positions expressed by the party majority sustaining the Government.

Indeed, if we take into account the ‘parliamentary majority’ variable, certain important observations may be made. For example, Giuseppe Conte – during his first Government (Lega Nord-Movimento Cinque Stelle) – is quite critical of EU institutions, but that Government was supported by the aforementioned two parties with their respective Euro-sceptic and Euro-critical positions, and so Conte's stance is e hardly surprising. Matteo Renzi, on the other hand, directly attacks the EU leadership and Euro policies, despite the fact that his Government was supported by a strongly pro-European parliamentary majority. The same incongruence can be found in the case of Berlusconi's third government (Berlusconi III 2008–2011): he effectively gave some of the most pro-European speeches of them all, despite the fact that his own parliamentary majority was composed of a Euro-sceptic party like LN, and that within his own party – Popolo delle Libertà (People of Freedom – PdL) – there were strong critics of the EU, such as the Minister of the Economy, Giulio Tremonti. This does not mean that the type of parliamentary majority does not affect a PM's own position, but rather that this variable does not appear to decisively influence the narrative of the relationship between Italy and the EU, as presented in the official parliamentary statements.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the symbols relating to the three macro-areas on which the codebook is based: polity, politics, and policy. The most important observation resulting from this table is that the politics symbols were marginal, or virtually absent, until the Prodi II government. This is very important, given that this category groups together those symbols closely linked to the procedural/conflictual dimensions of politics and to the interconnection between political parties and/or institutional actors. The almost total absence of these symbols in previous years seems to point to the argument sustaining the de-politicization of the EU arena (Mair, Reference Mair2013), that is, the decision to protect EU institutions from political conflict, by strengthening the non-majoritarian, techno-bureaucratic aspects of the integration process (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005; De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b).

The fact that from the Berlusconi IV government onwards, we observe the greater relevance and frequency (partly preponderance) of politics symbols – regardless of whether they are positive or negative – confirms the fact that the crisis triggered a process of open politicization of the EU (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b), which is now one of the most prominent political issues capable of influencing contemporary political systems and the structure of inter-party competition (Milkin, Reference Milkin2014).

Moreover, the analysis reveals that the reference to a particular issue is influenced by the transition from the pre-crisis period to the post-crisis period: the reform and review of treaties – a polity indicator – which is a constant in the PMs' speeches up to the Berlusconi IV government, almost disappears in the years following the crisis. This means that the idea of an EU that can be incrementally changed through treaty reforms that are the result of the involvement of the EU institutions appears to disappear during this phase, thus offering increasingly greater room for intergovernmental negotiations (Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2016; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b).

As far as politics is concerned, the only category that constantly emerges in all of the speeches (albeit less so than in those of the Berlusconi I Government) is that of the ‘Acceptance of the indication and respect of the commitments made at European level’. This observation is extremely interesting, since it confirms the close political link between the national and European arenas, and therefore the presence of the EU's ‘external constraint’ (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo, Della Sala, Magone, Laffan and Schwerger2016b), which is exercised through the implicit conditionality mechanism (Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2015). The concept of implicit conditionality refers to the implicit adherence to reforms and/or changes without the explicit threat of a sanction, in contrast to formal conditionality which, on the contrary, is based on the signing of official commitments and memoranda. This mechanism boasts a clear-cut effectiveness because it is based on a profound asymmetry of power, which allows a contracting actor to ‘impose’ reforms and supervise the compliance of the weaker partner to those required changes (including an evaluation of the results achieved). As Sacchi explains, this was the case of the Berlusconi and Monti governments and their relationship with EU institutions (Reference Sacchi2015).

The paramount presence of the external constraint – mainly exercised through the implicit conditionality mechanism – appears in almost all those discourses characterized by a totally positive tone, with the clear exception of the Renzi and Conte I governments, where the pressure exercised by the constraint is rejected and considered as extremely negative for Italy, as is clearly shown in the following statements:

Renzi: trovo che sia assolutamente fondamentale che si esca da una visione per la quale l'Europa ci controlla i compiti o l'Europa ci fa le pulci (…). Il pacchetto di misure che presentiamo all'Unione europea, non viene presentato per ottenere un imprimatur o una bollinatura, o ottenere il timbro (19 March 2014).

(I think it is absolutely vital that we stop seeing Europe as checking our homework or scrutinising our every move (…). The package of measures that we present to the European Union is not presented to obtain its approval or disapproval, or its stamp of endorsement) (Author's own translation).

Conte: spiegheremo, infine, che non abbiamo accolto le loro raccomandazioni in materia di aggiustamento strutturale, perché non compatibili con lo stato congiunturale della nostra economia e con il nostro disegno di politica economica (22 November 2018).

(Finally, we will explain that we have not accepted their recommendations on structural adjustments, because they are not compatible with the state of our economy or with our economic policy design) (Author's own translation).

Otherwise, the policy symbols (Table 2) recur in a homogeneous way over time in all of the speeches concerned. The constant re-proposal of the theme of immigration and border controls in this category is rather interesting. This is a topic that has gained prominence and has taken on a strictly political significance over the last 5 years, and has repeatedly called into question the role of the EU and of the European solidarity mechanism. The content analysis reveals that over the years, there has been a constant emphasis on the need to develop European, rather than national, borders, and to promote a deeper involvement of European institutions, requiring a supranational approach to the management of the incoming migratory flows.

Table 3 provides a synopsis of other important elements for the purpose of our discussion; for the sake of brevity, I decided to focus on the four most discussed topics in the parliamentary speeches of each single PM, thus offering a valid overview of the main tendencies seen in the case of each individual PM. For each area, the focus is on the percentage frequency with which those symbols recur, and an indication is given of the areas to which the categories belong, so as to identify any regularities and peculiarities in the recurrence of symbols for each PM.

Table 3. Most recurring symbols

An analysis of the most often recurring categories confirms what we had previously indicated, namely that the politics category is used exclusively from the Prodi II Government onwards, and as such offers proof of a clear break in the time series. From the beginning of the economic crisis, the EU and European politics has become an area of heated political confrontation: a macro-issue characterized by a strong degree of conflict. In an almost mirror-like manner, references to the category of polity – that is, references to the European political system – dramatically decrease. In this regard, the record-holder is Giuliano Amato, in whose case all four categories belong to that area. With regard to the frequency with which certain categories are mentioned, the result is as follows: of the 52 categories considered in Table 3, the four that come up most frequently are: ‘public finance control rules’ and ‘support for European policies’, each with a share of 11.5%, and ‘governance of European political choices’ and ‘evaluation of the integration process’ each with a share of 10%.

Moving on now to the frequency with which certain categories are addressed, it is interesting to see the specific issues that PMs' speeches focus on. For example, during his first government, PM Prodi emphasized the fact that the reviewing and controlling of public spending, together with debt reduction, are unavoidable steps towards bringing the Italian economy into line with those of the future Eurozone (19.2%), and stressed the importance of joining the single currency and a stable monetary area (15.4%).

The Berlusconi IV government was also characterized by a very strong emphasis on the need to keep public spending under control (32.9%) in order to safeguard the Italian economy from on-going speculation. In this regard, it is remarkable how Berlusconi stresses the importance of new agreements such as the fiscal compact, in order to guarantee financial and economic stability, presenting them as necessary tools for the interests of the country (20%). Monti, on the other hand, focuses on the role of European policy governance (20.1%), by associating it with the agreements and treaties signed by the previous government (15%), pointing out that his government had not been responsible for certain political choices, and that it was mainly committed to respecting those agreements. Letta and Gentiloni, on the other hand, shift the focus of their speeches towards the question of values, by emphasizing the importance and the irrevocability of the integration process, and presenting it as ‘a yet unfinished challenge’ which Italy must have a leading role in, due to its strongly pro-European tradition (12.6% and 12.7%).

Once the general framework has been defined, what can be said about the PMs' specific considerations regarding these topics? How do they deal with the relationship with the EU after the onset of the economic crisis? Has that relationship evolved positively or negatively? In the next section, I shall be focusing more in depth on the PMs' speeches of the period beginning with the 2008 economic crisis, in order to establish whether the multiple European crises have also represented a turning point in the way that the relationship between Italian governments and the EU institutions is portrayed.

Data analysis: the speeches made by Italy's Prime Ministers following the onset of the economic crisis

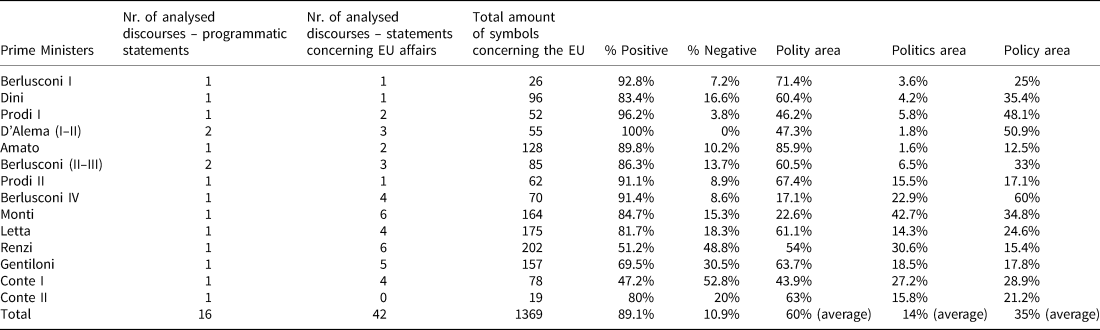

In order to understand the pattern of Italy–EU relations after 2008 and to address the various issues presented in the previous section, I have decided to focus on Italy's governments starting with Berlusconi IV, and on the post-crisis period, in order to assess any critical features of this relationship. For the six PMs thus analysed, I focus on the four most significant and recurring categories. Berlusconi's speeches (Figure 1) are characterized by a substantial adherence to the dictates of Brussels, not only in the form of a positive assessment of the budget rules, but also through his constant reference to the absolute toned for rapid compliance with the instructions and guidelines issued by the European institutions and the EU partners.

Berlusconi: Questa manovra (economica) è stata concepita in coerenza con gli obiettivi fissati in sede europea ed è stata giudicata adeguata e sufficiente dall'Europa e da tutti gli osservatori internazionali anche relativamente alla tempistica (3 August 2011).

Figure 1. Berlusconi IV government. Distribution of symbols.

(The (budgetary) manoeuvre was designed in line with the objectives set at European level and was judged adequate and sufficient by Europe and by all international observers, also in terms of the corresponding timing) (Author's own translation).

This means that the relationship with the EU is presented as extremely positive, and in clear keeping with the positions adopted by past Italian governments. This stance is particularly interesting, as the Berlusconi government was to be politically overwhelmed by the sovereign debt crisis and by the worsening of the economic situation throughout Europe (Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2015). The continuous reference to the goodness/necessity of meeting the requests of EU institutions can be accounted for by the fact that it was of instrumental importance for Berlusconi to legitimize the de facto external control exercised by the EU (Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2015). Finally, it is interesting to note how Berlusconi is the first and only PM to have made reference to the relationship with parties from the same European political family, in this case the European People's Party (EPP). This can be ascribed to Berlusconi's pursuit of a minimum of support from the major European governments, through his frequent reference to shared cultures/values in relation to membership of the EPP (at that time, almost all major European leaders were EPP members). This reference to the common European party family was part of the PM's ploy to ease the intense pressure from EU partners, to the result of the Italian government's inability to implement the required reforms.

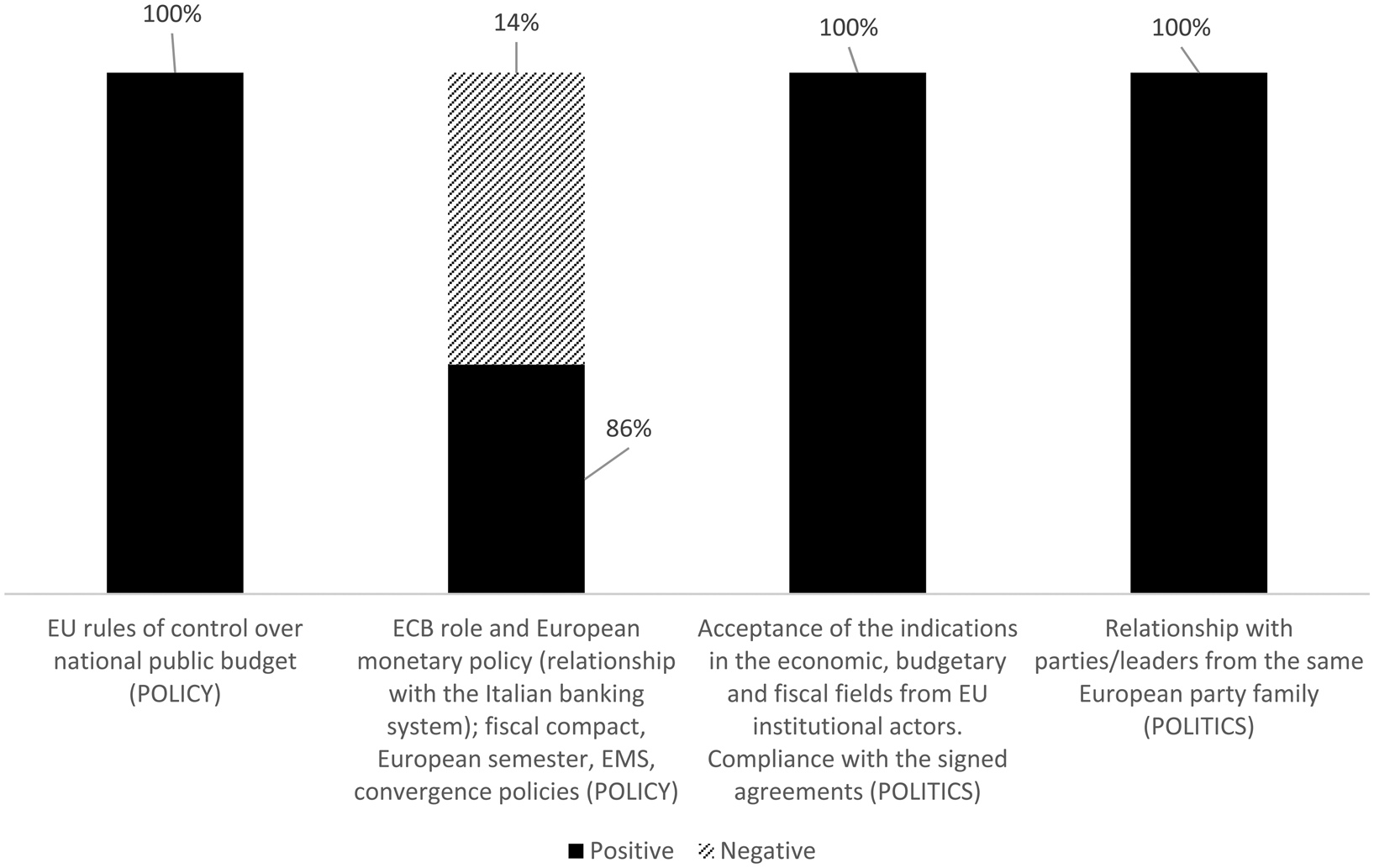

The case of Mario Monti, who took over from Berlusconi in December 2011 as head of a large coalition government, is very different. While Monti, like his predecessor, underlined the added value for Italy of compliance with state budget control parameters (Figure 2), he did criticize the way EU institutions – and some governments within the Euro area – had handled the crisis. This criticism was aimed at two aspects of the latter: the lack of focus on economic growth, and the strict application of measures that could hinder economic recovery. Although the negative symbols are statistically marginal, a degree of reproach also emerges in regard to the package of new policies adopted by the EU (fiscal compact, Six Pack, etc.).

Monti: rispetto alle norme relative alla disciplina delle finanze pubbliche, è quello di evitare che si introducano vincoli più rigidi, limiti procedurali o ulteriori sanzioni rispetto a quelli già esistenti nell'ambito del Patto di stabilità e di crescita dopo le riforme approvate nel quadro del cosiddetto Six Pack, approvato dal Consiglio e dal Parlamento solo pochi mesi fa. (…) se l'obiettivo dichiarato è anche quello di dotare l'unione economica e monetaria di un più solido pilastro economico, è necessario bilanciare le norme relative alla disciplina delle finanze pubbliche con disposizioni volte a promuovere la crescita e le politiche per la competitività, in primo luogo rafforzando l'integrazione economica all'interno del mercato unico (16 January 2012).

Figure 2. Monti government. Distribution of symbols.

(The aim of the new framework is to prevent the introduction of stricter constraints, procedural limits or additional sanctions to those already in place under the Stability and Growth Pact following the reforms approved under the so-called Six Pack, which was approved by the Council and Parliament only a few months ago. (…) if the stated objective is also to provide the economic and monetary union with a more solid economic basis, it is necessary to balance the rules on public finance governance with growth-enhancing provisions and competitiveness policies, primarily by strengthening economic integration within the single market) (Author's own translation).

Under the Letta Government, priorities changed and the level of criticism aimed at the EU was clearly different. First of all, Letta (Figure 3) decided to promote parliamentary communications emphasizing the value aspect of the European integration process, and therefore Italy's traditional participation in that process. In addition to repeatedly stressing the Europeanist style of his government, and the self-denial required in the name of integration, Letta was the first Italian PM since 1994 to explicitly and clearly request the strengthening of the EU's supranational sphere of influence, in an attempt to contain the intergovernmental model that had dominated the European decision-making process since 2008 (Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2016; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b).

Letta: Senza gli Stati Uniti d'Europa ogni progresso, anche il più ambizioso e faticoso, rischia di essere svuotato di senso (22 May 2013).

(Without the United States of Europe, any progress, even the most ambitious and difficult form of progress, risks being meaningless) (Author own translation).

Letta: (…) tra chi vuole un meccanismo di tipo intergovernativo, in cui ogni Stato può porre il veto alle decisioni relative alle sue banche nazionali, e chi, tra cui noi, l'Italia, chiede un meccanismo sovranazionale garantito da un backstop dotato di risorse europee (22 October 2013)

Figure 3. Letta government. Distribution of symbols.

((…) among those who want an intergovernmental mechanism, in which each State can veto decisions relating to its national banks, and those who, including us, Italy, are calling for a supranational mechanism guaranteed by a backstop with European resources) (Author's own translation).

Even more important is the data for the symbols concerning the governance of the major European political decisions: in this regard, Monti's partial criticism is trumped by Letta's full-blown criticism of the major European governments and the EU institutions concerning the important decisions made over the previous 5 years. This was the first time that a strongly negative assessment had been made by an Italian PM in regard to an important area of community politics: a process of politicization taking on the tone of radical opposition.

Letta: (…) L'Europa sia finalmente in grado di offrire un ambiente che ampli e sostenga la capacità di azione della politica nazionale e non si traduca in una gabbia di vincoli, regole e procedure che (…) finiscono spesso per limitare l'azione di tutti: famiglie, cittadini, piccole e grandi imprese (22 May 2013).

(Europe should finally be able to offer an environment that broadens and supports the capacity for action of national policy, and does not result in a series of constraints, rules and procedures that (…) often end up hindering the action of all: families, citizens, small and large enterprises) (Author's own translation).

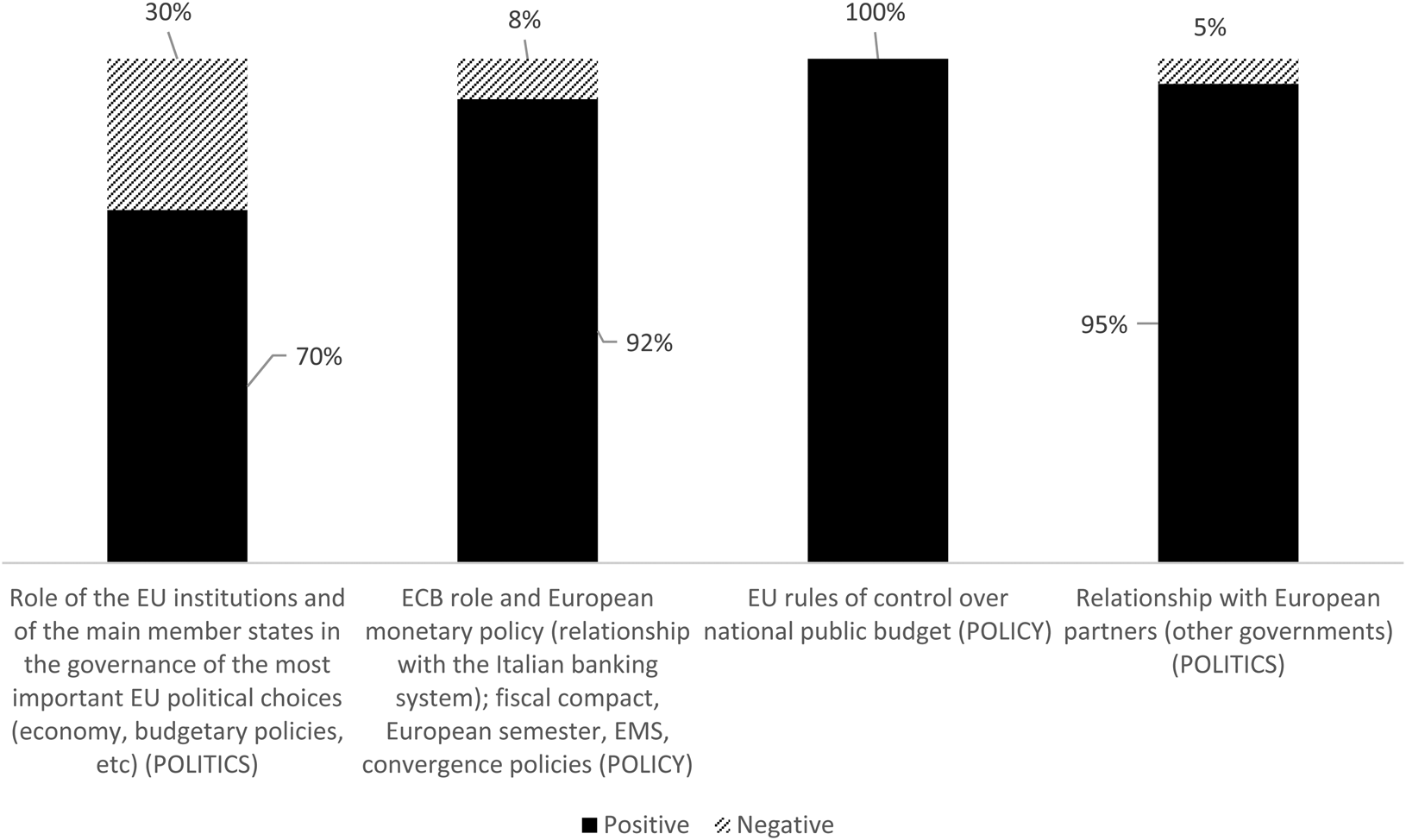

The Renzi Government (Figure 4) represented a substantial change in the way that Italy's government relate to the EU, as assessed through parliamentary discourse. Three of the four categories that Renzi's speeches concentrated on have an eminently negative connotation and therefore a clearly adversarial dimension with regard to the EU; this shows a typical trait of Renzi's leadership style developed over the years (Salvati, Reference Salvati2016). The fact that two categories belong to the politics area confirms his desire to instigate political conflict with Brussels.

Figure 4. Renzi government. Distribution of symbols.

Renzi's parliamentary speeches diverge from the classic narrative established by Italy's elites in regard to the EU: his is an attempt to emphasize the need for Europe to change its present functioning and arrangements, and for a return to the original values of the European project (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a; Reference Brunazzo, Della Sala, Magone, Laffan and Schwerger2016b). This last point is confirmed by the fact that the only positive category is that of references to the European identity and the need to rediscover the value of European community membership and its underlying rationale. Renzi strongly criticizes the governance of the policy decisions made by the EU during the years of the crisis; Brussels and the governments that support austerity are deemed responsible for the poor economic growth of the Euro area, and in particular for the non-solidarity and unequal management of the immigration question.

This criticism is exacerbated by the fact that Renzi identifies the EU's limitations and responsibilities as resulting from its domination by technocrats and bureaucrats, and thus he goes against the communitarian structure and encourages the true politicization of the EU and a change in the community process.

Renzi: (…) lottare contro un'Europa che sia semplicemente espressione della tecnocrazia e della burocrazia e fare dell'Europa, riprendere quello sguardo profondamente alto e ideale che l'Unione europea aveva avuto nel sogno dei padri fondatori e nel sogno dei Paesi fondatori, tra cui l'Italia (12 March 2014).

((…) to fight against a Europe that is simply an expression of technocracy and bureaucracy, and to restore that profoundly ideal outlook underlying the European Union project as conceived by its founding fathers and its founder members, including Italy) (Author's own translation).

It is particularly interesting to note the significant hostility towards acceptance of Community recommendations, with an Italian PM for the first time ever rejecting the idea that Italy must simply conform to the recommendations of the European institutions and/or of other governments within the Union. From this point of view, Renzi repeatedly underlines his belief that Italy has already played its part, and represents more a virtuous model than a cause for concern.

Gentiloni's approach differs only partially from that of Renzi (Figure 5); while his criticism and negativity is not as predominant as that of Renzi, his period in the office did not witness a return to the pre-crisis type of parliamentary speech. As for Letta, his positive evaluation is entirely based on the value categories, which were the same as those used by his former party colleague: a re-launch of the process of integration, and a rebalancing of the decision-making axis in favour of a supranational model. Gentiloni repeatedly pointed to the need for a model of differentiated integration for the EU in order to restart the integration process.

Figure 5. Gentiloni government. Distribution of symbols.

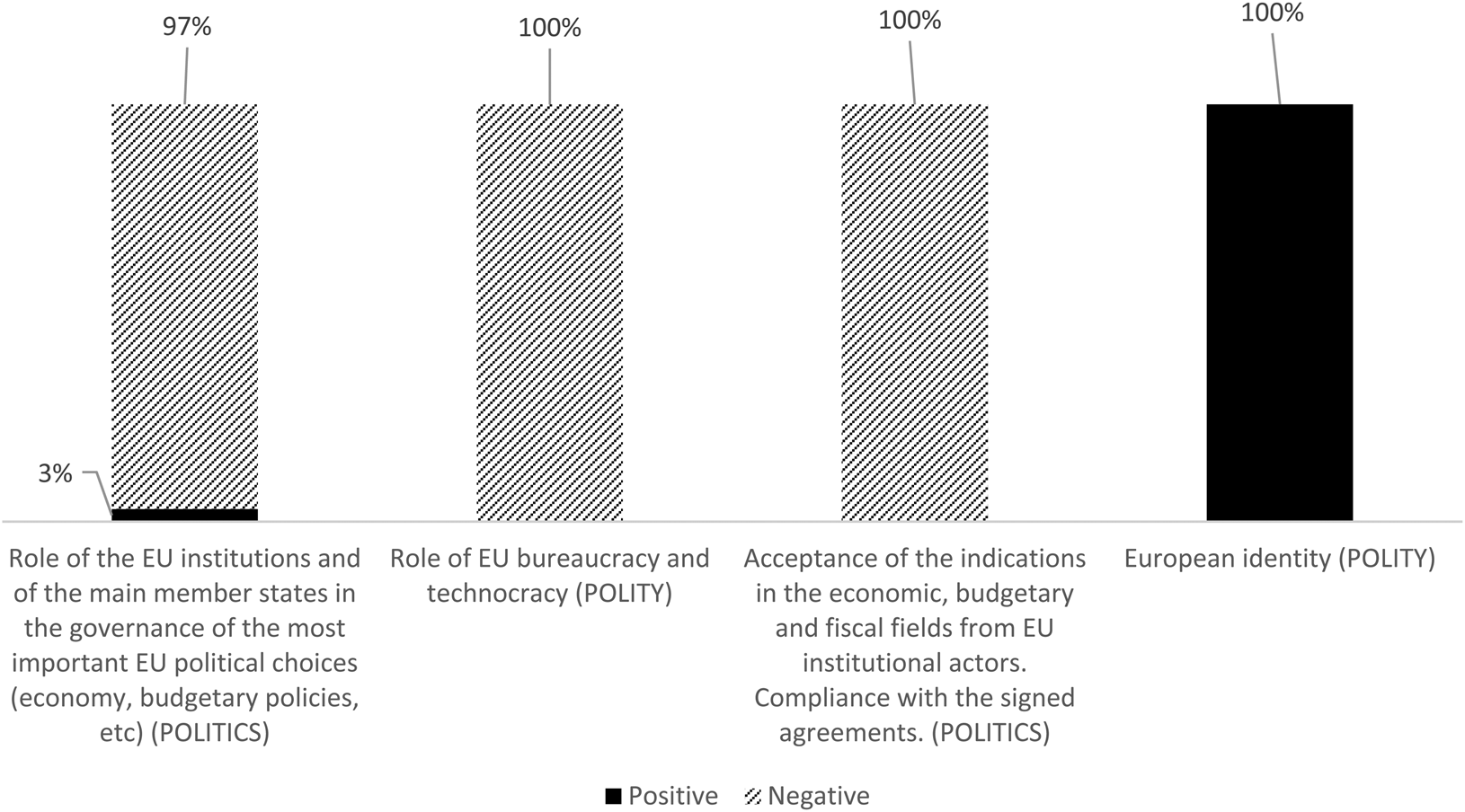

The first Conte government (Figure 6) was of an ‘attention-grabbing’ nature, since it was the first European governmental coalition composed exclusively of populist parties, one of which – the LN – is openly Euro-sceptic (Chari et al., Reference Chari, Iltanen and Kritzinger2004; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Szczerbiak and Taggart2008), while the other – the M5S – has held fluctuating/uncertain stances on the question of European integration (Cremonesi and Salvati, Reference Cremonesi and Salvati2019; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019a; Reference Salvati2019b). The category that the majority of positive references focus on is that pertaining to the EU's role in the handling of the migration issue. Conte specifically called for the greater involvement of the EU in the management of migration flows, with express reference to European borders.

Conte: proponiamo una european multilevel strategy for migration, una proposta articolata e organica basata sul nuovo approccio, che consenta all'Europa di uscire da una logica di gestione emergenziale e le consenta di confidare su una logica di gestione strutturale, da riconoscere definitivamente come priorità. (Bisogna) rafforzare le frontiere esterne dell'Unione Europea (7 June 2018).

Figure 6. Conte I government. Distribution of symbols.

(We propose a European multilevel strategy for migration, that is, an articulated and organic proposal based on the new approach, which allows Europe to move away from a logic of emergency management towards a logic of structural management, to be finally recognized as a priority (We need to) strengthen the external borders of the European Union) (Author's own translation).

This aspect is associated with a radical criticism of the governance of European economic policies and of how the issue of migrants' landings has been managed in previous years. Conte strongly criticizes past and present policy, leaving room for a call for ‘more Europe’ on this issue. However, it is interesting to observe that this request was accompanied by his insistence on defending national interests within Europe: he is the only PM to openly state that the Italian government will operate in Brussels mainly in defence of Italy's interests.

The other negative reference, in Conte's case, concerns the rules governing budget control, with his position clearly being influenced by the tug-of-war with the Commission over the budget manoeuvre for 2019. During his first experience in government, Conte repeatedly emphasized his belief that these constraints, combined with the EU's governance of the Eurozone and the budgetary and monetary sector (i.e. the reform of the European Stability Mechanism, the Fiscal Compact, etc.), should be considered as the main obstacle to economic growth. This embodies a straightforward refusal of conditionality, which is confirmed by his negative references – the first and only PM to do so – to the detrimental effects that the EU institutions and many of the political choices made at European level can have on the quality of Italy's democratic life.

Conte: (…) questi meccanismi di condivisione del rischio non debbono contemplare condizionalità che, in nome dell'obiettivo della riduzione del rischio, finiscano per irrigidire processi già avviati. (…) Siamo contrari ad ogni rigidità nella riforma del meccanismo europeo di stabilità: soprattutto perché nuovi vincoli al processo di ristrutturazione del debito potrebbero contribuire proprio essi all'instabilità finanziaria, anziché prevenirla (June 2018).

(These risk-sharing mechanisms must not include conditions which, in order to reduce risk, would ultimately render on-going processes more intransigent. (…) We are against any tightening of the reform of the European Stability Mechanism, especially as new constraints on the debt restructuring process could contribute to financial instability rather than prevent it) (Author's own translation).

The current Conte II government, which emerged following the end of the coalition between LN and M5S, is actually supported by a more pro-European majority due to the presence of the Partito Democratico (Democratic Party – PD). This brand new coalition arrangement does not seem to have had any great impact on the main topics considered by Giuseppe Conte (Figure 7). As in his first experience as PM, Conte emphasizes the need for the EU to play a stronger role in managing the immigration issue, and makes know his strong disapproval of certain previous political positions adopted by EU institutions, in particular with regard to the financial and monetary sector. The main difference from his previous period as PM is represented by his direct reference to the need for stronger, renewed cooperation and solidarity among EU member states.

Figure 7. Conte II government. Distribution of symbols.

This partial continuity in Conte's discourse confirms the absence of any clear, direct correlation between a parliamentary majority's position on the EU and the parliamentary discourse of its PM. As far as regards the Conte II Government, an important caveat applies: the analysis is based on one speech only, and so it is not possible to offer any clear-cut definition of Conte's (possible) new approach to the EU. It will be interesting to analyse the development of this relationship on the basis of a larger dataset of parliamentary speeches, which for the moment is not available.

Discussion and conclusions

The empirical analysis of the PMs' parliamentary speeches confirms the belief that the relationship between the Italian political elite and the EU is a mix of continuity and rifts. The continuity resides above all in the absence of any real split over adhesion to the founding values of the Union, and in the constantly positive nature of the references made to the integration process – whether they are based on instrumental reasoning such as that of European integration being the best way of protecting Italy's interests, an echo of the external bond and of the ‘rescued by Europe’ argument (Ferrera and Gualmini, Reference Ferrera and Gualmini2004), or on genuine ideals (European values, continental solidarity). The rift came about with the crisis that has fuelled a drift in the approach to Europe towards a phase of politicization of the integration issue (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b). As far as concerns the relationship between PMs and their parliamentary majorities, there does not seem to be any direct, linear correlation between PMs' speeches and party positions on the EU. PMs who are more critical of the EU do not necessarily correspond to a Euro-sceptic or Euro-critical parliamentary majority, while PMs who have adopted more favourable stances with regard to the EU do not necessarily correspond to a strong pro-EU majority. This matter needs to be analysed further in order to establish the degree of political congruence between the position of PMs and parties in regard to EU integration, during the course of Italy's Second Republic.

After the year 2008, the symbols of politics become predominant, and the categories pointing to conflict with European institutions and the major governments of the euro area (Germany and France) become preponderant. The narrative regarding the EU thus takes on pronounced dialectical and critical tones, especially after the most acute phase of the economic and financial crisis, during which Berlusconi and Monti (2008–2013) underlined the goodness of the actions taken by EU institutions, above all in terms of the need for the country to adapt to EU guidelines. These two PMs were the ones who were most affected by the impact of implicit conditionality, and who consequently tried to legitimize, in their public speeches, the EU's interference in Italy's domestic issues. As De la Porte and Heins (Reference De la Porte and Heins2015) have pointed out, these aspects relate mainly to the questions of the conditioning/monitoring of policy objectives, the monitoring of the policies adopted, and the methods of implementation utilized.

Letta and Gentiloni were both strongly critical of the governance of the EU's political decisions during the 2008–2013 period; however, they both make a clear appeal to the rediscovery of the values of a united Europe, by re-launching the integration theme from a clearly supranational perspective and criticizing the excessively intergovernmental nature of the EU's political decisions (Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b). Their references to the intrinsic value of EU integration and to Europe's shared values confirm how the discourse of Europe's political elites tends to focus on the question of identity, particularly when the crisis of, and danger for, the European project are perceived (Conti, Reference Conti, Best, Lengyel and Verzichelli2012).

Renzi's presidency was the one characterized, in many ways, by genuine open conflict with the EU, thus marking not only a decisive veering away from the approach to relations between Italy and the EU generally shared by all previous governments, but also a clear break with the narrative of the centre-left regarding Europe (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011; Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a). Although Renzi's speeches are fundamentally anchored to Europeanism, and indeed praise the rediscovery of the logic and values underlying European unity, he strongly attacks the EU's diplo-techno-bureaucratic model (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005), which he believes is what governs the Union; he makes a long series of accusations against the European technocracy, and clearly rejects the conditionality mechanism.

Unlike Letta and Gentiloni, and in many ways similarly to Conte I, Renzi sees the furthering of the integration process as the result of the review of European decision-making tools, which does not discard the intergovernmental method however, but is based on open bargaining between governments (Carbone, Reference Carbone2015). This stance is reinforced, in fact, by Renzi's vision of the Commission as an inefficient, techno-bureaucratic arena where there is no room for politics or political decision. He calls for ‘more politics’ played out at the negotiating table by national governments, and not linked to any reinforcement of the supranational institutions.

Conte, in keeping with Renzi's muscular approach, and in addition to the criticisms made by his predecessor, expressed strong hostility towards public spending controls, and he indeed declared that certain forms of intervention on the part of EU institutions risked undermining the democratic character of the country.

Albeit in different ways, both Renzi and Conte distanced themselves from the traditional approach to the EU of previous Italian PMs. This can be seen in the willingness of these two PMs to build a public discourse on Europe that is more in keeping with the erosion of Italians' traditional Europeanism. The tones of their speeches, and the issues addressed by those speeches, cannot be defined as those of Euro-sceptics: in fact, despite their increased disaffection with the EU, Italians continue to declare a non-marginal level of appreciation of EU membership (Isernia, Reference Isernia, Cotta, Isernia and Verzichelli2005).

The elite's adhesion to the European process is still strong, but this is no longer an ‘adherence in principle’ based on the rhetoric or myth of the external constraint (Brunazzo and Della Sala, Reference Brunazzo and Della Sala2016a). The latter position has been replaced by a more critical and politicized Europeanism (Salvati, Reference Salvati2019a), whereby leaders such as Renzi and Conte invoke the substantial reform of Europe and a rejection of consolidated decision-making models. Our analysis shows that 2008 represented a watershed in the relationship between Italy's elites and the EU, thus confirming how the economic issue in the Italian context is a key to the greater or lesser inclination towards Euro-scepticism and to the evaluation of the integration process (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2011; Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015).

As Quaglia (Reference Quaglia2011) points out, unsatisfactory economic conditions are a key to stoking Euro-scepticism among the public, and to paving the way for those political entrepreneurs capable of embracing strategic Euro-scepticism in order to generate political consent. From this point of view, the changes in the ‘Euro-narrative’ of some Italian PMs seem to be strictly connected to, and can be accounted for by, an exogenous factor like the economic crisis, thus confirming previous findings concerning this relationship (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Szczerbiak and Taggart2008, Reference Quaglia2011; Di Mauro, Reference Di Mauro2014; Conti and Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015).

In any case, as Conti says, strong Euro-scepticism seems to be an episodic, non-characterizing phenomenon (2017), a fact that this research confirms. At the same time, the overall picture of Italy–EU relations given by Italy's PMs has effectively shifted towards a more conflictual, politicized dimension. Moreover, this ‘muscular’ approach to European politics clearly indicates a rejection of the conditionality mechanism, and thus an attempt to correct this increasingly pervasive role of the EU, which takes the form of an on-going merger of the two arenas instead of a redefinition of powers and competences in terms of multilevel governance (Sacchi, Reference Sacchi2015). Furthermore, the PMs' speeches reveal an awareness of the strong tension between responsibility and responsiveness (demands and short-term gains vs. needs and long-term duties) (Bardi et al., Reference Bardi, Bartolini, Trechsel, Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2015); this tension is caused by the caveats created by EU conditionality, which hamper the nation state's capability and freedom to use the budget deficit to finance expensive public policies.

These changes are thus closely linked to the several crises impacting the EU over the last 10 years, and to all of the consequences of those crises. Such consequences concern both the political elites, who have been forced to readjust their positions on the European theme, due to their increased vulnerability to the strengthening of populist and Euro-sceptical parties (Cotta, Reference Cotta2018; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b), and also national party systems that have been destabilized by de-alignment and re-alignment processes, including those subsequent to the emergence of new political parties and movements (Hernández and Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). The result has been a phase of strong politicization of the EU issue, without however any coherent public debate on the European integration process and the role of Italy within the EU (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia, Szczerbiak and Taggart2008; Salvati, Reference Salvati2019b).

This situation has produced two results: on the one hand, the elites of the mainstream parties have been given an incentive to move towards more critical positions vis-à-vis the EU, in order to counter domestic electoral losses; on the other hand, those same elites have chosen to support a much more intergovernmental decision-making process at EU level, thus marginalizing the role of supranational institutions: hence the call for ‘more Europe’ has been a rather weak appeal.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.