A. Introduction

The principle of individual liberty is not involved in the doctrine of free trade. Footnote 1

On February 11, 2020, British parliamentarian Fay Jones tweeted a photo of herself in the Houses of Parliament. As a young politician with over four thousand followers on Twitter, she most likely uses the platform to engage with her potential voters, and to increase her political influence—for example, by reaching more constituents—a social media presence that is not only common but also very much expected from contemporary politicians. However, what was likely unexpected was the fact that this particular tweet looked very much like a commercial. The tweet—since then deleted—read: “Delighted to see Parliament stocking @Radnorhills water! A brilliant firm in my constituency—employing over 200 people and putting sustainability right at the heart of their business. #RadnorHills.” It was later revealed that in early January, Jones had received a £10,000 donation from the water company referenced in her photo.Footnote 2

During the same month, Mike Bloomberg’s campaign for the presidency of the United States started collaborating with Instagram influencers.Footnote 3 For a $150 fee, the Meme 2020 project, led on behalf of Bloomberg by the Instagram-savvy owner of a well-known Instagram meme account, started asking various influencers to create content for Bloomberg, in an attempt to increase his reach and popularity among younger voters on the social media platform.Footnote 4

The two illustrations point to an emerging question of how to demarcate between political and commercial communication on social media. Scholars have already addressed the many issues that surround political advertising on social media, such as the use of platform ad archives,Footnote 5 or how platform affordances can be used and abused in the context of political advertising. However, in the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica incident, social media platforms are trying to take action against the foul use of their commercial services in the promotion of electoral interests. In consequence, platforms started taking measures to limit the scope of the influence of political vehicles of speech in their online space. As an example, Twitter and Facebook imposed various types of bans on political advertising.Footnote 6

Even though they are meant to bring clarity on political communication, these bans may, however, have unexpected adverse effects, especially because they are taking place at a time when native advertising is permeating public discourse not solely through purchasing ads from a platform, but through purchasing ads from other individuals. This phenomenon consists of using people as advertising banners, and it is known as influencer marketing.Footnote 7 In the past five years, digital marketing has been increasingly turning to influencers—often referred to also as “content creators”—as relatable and genuine advertisers who can effectively engage with consumers in the context of social commerce, as citizens/consumers turn to social media for entertainment, shopping, news, and the opinions of their peers, all shareable or retrievable in and from the same place. While lucrative and attractive for freelancers who want to use their creative talents for entertainment through content creation, social media influencing is often affiliated with dangers arising out of manipulative behavior that has an undisclosed commercial intent. So far, advertising laws adopted to protect consumers dictate that commercial communication must be disclosed, and European reforms on platform governance further crystalize disclosure duties—for example, Article 24 of the Digital Services Act as amended by the European Parliament in January 2022.Footnote 8 In addition, the monetization of content creation is increasingly receiving attention from regulators around the world,Footnote 9 for instance in addressing the need to protect vulnerable groups such as children.Footnote 10 In the consumer space alone, monetization has led to alarming enforcement questions, as detection at scale remains very difficult to achieve for public authorities.Footnote 11 In other words, while in enforcement practice it may already be difficult to distinguish an ad—which needs disclosure—from a personal post by a content creator, it is even more challenging to draw a line between a commercial and a political post.

Political speech enjoys the highest degree of protection by national constitutions, supranational, and international charters. Unlike commercial speech which usuallyenjoy less constitutional protection, political speech is the foundation of constitutional democracies. The blurring line between political and commercial speech introduces a new layer of complexity in tackling hidden political advertising. Indeed, political speech is likely to attract commercial speech inside a broader scope of protection with the result that potential limitations of this kind of speech would be required to pass a very strict test through the balance with other constitutional safeguards or legitimate interests according to the criteria of necessity, legitimacy, and proportionality. This could also question the scope of other regulation designed to govern commercial speech like advertising.

This article addresses the specific challenges arising from the monetization of political speech on social media, and proposes a normative argument to extend consumer disclosures to political speech. To this end, the article compares regulatory and judicial interpretations adopted in Europe and the United States, and is structured as follows. In the first part, we explore the content monetization business models—including influencer marketing—used on social media, and we identify three types of influencer “personas” who are prone to engage in political speech. The second part looks into the constitutional differences between commercial and political speech across the Atlantic. The third part explores the normative view that consumer disclosures, which may already apply to some types of political speech, could be used even further to alleviate the dangers of monetization, and the fourth part concludes.

B. Social Media and the Monetization of Political Content

I. General discussion

Called the “modern public square” by the US Supreme Court,Footnote 12 social media has already ignited a lot of broad academic debates relating to the nature of this space,Footnote 13 speech freedoms or limitations,Footnote 14 and intermediary liability,Footnote 15 just to give a few examples. In recent times, as a reflection of the new complexities brought about by factors such as the very large scale at which social media platforms operate as well as the implications of data markets, social media dynamics have been shifting from the classical discourse of the user’s freedom of expression and the moderation of this content, to more sophisticated supply chains generated by the rising content creation economy.Footnote 16 While content moderation has received a lot of public scrutiny, the same cannot be said about the monetization of content creation. So far, the phenomenon of monetizing content on the Internet has been mostly analyzed from the perspective of the platforms that operate various advertising structures, such as Google’s AdSenseFootnote 18 or Facebook’s sponsored posts.Footnote 18

Yet there is an emerging category that deserves a more prominent place in discussions relating to content creation and monetization—content creators. Also called influencers, content creators are individuals who make content on social media with the hope that they can monetize it in various ways. So far, influencers have been acknowledged by the growing body of literature on influencer marketing, consisting of the creation of content on behalf of brands which pay or offer goods or services in exchange, in the context of disclosing paid advertising. Yet, unlike legacy media, where the advertising industry has been held to more stringent transparency standards along the years, influencers often blur the lines between what they believe and what they are paid to believe. A telling example is the case of Rezo, a German influencer known for funny videos directed to a young audience, who in May 2019 surprised his followers with a political monologue in which he vehemently criticized the political promises and actions of the German party Christian Democratic Union (CDU).Footnote 19 At over 19.5 million views by February 2022, his video went viral in Germany as well as beyond that, and Rezo enjoyed a reputation boost from this activity. It is unclear why an influencer like Rezo, previously and subsequently focused on entertainment, would make such a video. One interpretation is that he focused on a specific gain, whether in the form of being paid to make the video, or knowingly addressing a controversial message to gain more engagement on the platforms or traction in legacy media. However, it may very well be that Rezo actually wanted to express his own, true opinion over the political process in Germany and saw fit to use his Youtube channel as a platform to express this message.

The very fact that the intentions behind such a video remain unclear is worrisome for two reasons. First, any paid videos, whether by a commercial or non-profit entity, should be accurately disclosed, according to rules currently in force in Europe as well as in the United States. When influencers take advantage of the blurry line between what can pass as their opinion, and what is a paid “review,” this shows the vulnerabilities of disclosure monitoring by consumer authorities and platforms alike. Second, influencers are increasingly using political messaging as a context of promoting goods or services. “There’s over 1 trillion dollars in student loan debt and people with outdated education who can’t even get a job for the student loans they took out … We need to create a movement for our generation,” says Jake Paul in one of his Youtube videos.Footnote 20 At first, this call to action focused on education policy in the United States seems taken out of the talking points included in a presidential debate. A better look at the video reveals that it is sponsored. As one of the most well-known influencers in the United States, Jake Paul was paid to promote a financial service launched by the “Financial Freedom Movement,” consisting of for-profit financial coaching.

II. Business Models and Political Speech

To better understand the interests of content creators, we must first explore their business models and practices. This is an endeavor often overlooked in legal analyses that have implications for content monetization. While this is, to a certain extent, understandable, as social media business models change at a fast pace, not systematizing stakeholders and transactions on social media is one of the reasons why this economy remains generally obscure to academics and regulators alike. This section aims to shed light on the business models used by content creators as a much-needed detailed factual background for the legal analysis to follow.

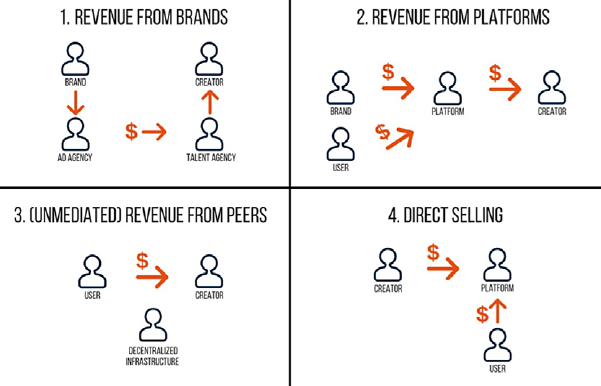

While the concept of content monetization has been traditionally used to refer to platform-based advertising structures which use individual channels to display ads, or integrate ads in user-recommended content, the creative ways in which a regular platform user could make money online have greatly diversified in the past decade and are in constant change. Taking the viewpoint of the user engaging in monetization, namely the influencer, we can distinguish different avenues of gaining income, as explored in Figure 1 and described below:

Figure 1. Monetization by content creatorsFootnote 21.

(i) Revenue from brands (influencer marketing) — Third parties can pay influencers or offer goods or services in exchange for the creation of native advertising by influencers, or the sharing of affiliate links through specific interface possibilities such as Instagram or TikTok’s link in bio and social commerce URLs.Footnote 22

(ii) Revenue from platforms (ad revenue; channel subscription; tokens; crowdfunding)—Platforms allow third parties to add their ads to an algorithmically-managed ad library. For instance, on YouTube, users who want to monetize their content may choose a specific “ad unit” such as display, overlay, video ads—skippable, non-skippable and bumper ads—and sponsored cards.Footnote 23 In addition, some platforms allow users to subscribe to premium content from creators, or to support them through microtransactions facilitated by the platform. Using this model, influencers can get income on social media platforms such as YouTube,Footnote 24 or from their own video streaming platforms. Platform tokens entail that users viewing content made by influencers can purchase tokens, or alternative “currencies” which they can spend to support or interact with their favorite creators. Examples include YouTube’s Super Chat or Super Sticker, that highlight messages when interacting on live streams,Footnote 25 or YouNow’s “bar” currency, allowing fans to “purchase premium gifts that help them further engage with broadcasters and support them.”Footnote 26 Lastly, through crowdfunding models—also mediated by platforms, for example, Patreon—influencers can also make money by being supported by their patron peers, who in turn receive a collection of “perks” against a tiered payment system.

(iii) Unmediated revenue from peers (web monetization)—Creators can also be supported by their peers through decentralized technologies. An example of such a decentralized infrastructure which is gaining popularity in this respect is the Web Monetization protocol, a payment standard which facilitates the receipt of microtransactions by creators from their supporters without any platform intermediary.Footnote 27

(iv) Direct selling—Influencers can also choose to create their own products—also known as “merch,” or merchandise—and link to their webshops using designated programs such as YouTube’s “merchandise shelf.”Footnote 28

The generous array of possibilities to monetize content on social media has undoubtedly enticed average social media users to become small-scale entrepreneurs and promote themselves as advertising vehicles.Footnote 29 Even within the realm of commercial transactions such as e-commerce, content monetization raises serious concerns that have led to regulatory reform. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is looking to review its Endorsement Guides for Advertising—which have not been updated since 2009Footnote 30— whereas in the European Union, the Consumer Omnibus Directive brought additions to the Unfair Commercial Practices DirectiveFootnote 31 by blacklisting practices such as the non-disclosure of advertorials,Footnote 32 or the promotion of fake reviews.Footnote 33 That is mostly due to the fact that social media users—and especially children—are believed to not always discern hidden advertising, making them more prone to manipulation for the purpose of commercial gain.Footnote 34

Out of all the business models outlined in Figure 1 and explored above, being sponsored by brands as part of an influencer marketing campaign raises the most questions. While revenue from platforms or peers is equally interesting, it does not raise similar issues about the integrity of the viewpoint explored by a creator, whereas being paid by a company to promote its products may very well raise integrity issues: Does the creator really like that product, or is it just mere puff?

While the tensions between regulators, platforms, and influencers are far from solved, the rise of influencers engaging in political speech raises new concerns relating to behavioral manipulation, especially at a time when platforms choose to ban political advertising.Footnote 35 A post on social media clearly labeled as an ad in a platform’s ad library not only makes the nature of the post more transparent, but this structural labeling can also facilitate more granular monitoring by platforms of public agencies. A post labelled as an ad can clearly be identified by users as advertising, meaning that a person or a company paid money for the user to see a commercial message. The move to not allow such posts on Twitter or Facebook is not only leading to the obscuring of commercial interests but is also pushing political actors to employ or even become social media influencers. Repeating the exercise of taking the point of view of the influencer, political speech can overlap with content monetization in various ways, depending on the influencer’s persona:

1. Politicians as Social Media Influencers

Politicians engaging on social media has led to a lot of academic and journalistic scrutiny.Footnote 36 While traditionally using their accounts to interact with voters or political competitors, politicians will increasingly use their platforms to promote the interests of their supporters. This has been seen in the barter-like action done by British parliamentarian Fay Jones when promoting the products of one of the companies which donated money to her political campaign. This indirect quid-pro-quo is not enshrined in one transaction or one contract, but rather consists of different actions that are determined by one another: A company offers financial support in exchange for visibility from a politician’s persuasive discourse and policy agenda.

2. Social Media Influencers as Political Opinion Leaders

Influencers can express their political opinions freely in the form of commentary channels and get ad revenue on the basis of the number of views they generate as well as the specific “ad units” they use—Platform ads model above. An example in this respect is the video by Rezo as discussed earlier. Additionally, as revealed in the case of Bloomberg’s campaign, owners of Instagram meme accounts were directly paid to make content promoting Bloomberg to their audiences, without disclosing the resulting memes as ads—Influencer marketing model above.

3. Social Media Influencers Turned Politicians

Influencers with political aspirations may nowadays start their careers on YouTube or may shift from other industries to politics. The case of Brazilian Youtuber Kim Kataguiri, the youngest person ever elected to the Brazilian Congress,Footnote 37 still uses AdSense on his YouTube channel, where he streams discussions from the country’s legislative branch for his over 500,000 followers.Footnote 38 In Kataguiri’s case, he even surpassed his initial role as a content creator with political opinions, as he took political office.

This article does not focus on a particular category of social media influencers, but rather actions which may be undertaken by any of the categories mentioned above, surrounding the monetization of political speech. As long as political content is created and posted on social media with the intention to obtain a direct or indirect revenue—known as monetized political content—we believe that novel issues relating to recognizing the fine line between commercial and political speech will arise.

The following sections thus examine the tensions found at the intersection of constitutional and unfair commercial practices law, and propose approaches meant to solve these tensions.

C. The Magnetic Effect between Commercial and Political Speech: A Constitutional Perspective

The rise of social media platforms has challenged the exercise of the right to free speech and its judicial protection. Constitutional protection afforded by states to freedom of expression is not uniform and changes across democratic countries. Forms of expression like commercial communications, which, in some states, fall within the constitutional umbrella of freedom of speech, may not be given the same relevance in other states.Footnote 39 The different values around free speech as also conditioned by moral and/or socio-political considerations are the reasons for different degrees of constitutional protection.Footnote 40 As it is deeply affected by cultural factors, free speech is foregrounded by the changes brought through digital technologies to the social conditions of speech.Footnote 41 The possibility to share ideas and opinions on a global scale indeed contributes to promoting the establishment of a democratic culture where any given participant can contribute to and engage in the communities which they identify with.Footnote 42 Even if free speech still has a primary role in promoting democratic values,Footnote 43 this approach to freedom of expression reflects more an earlier iteration of the Internet of social media platforms, focused on a more collaborative, peer-to-peer connectivity between platform users. Newer iterations of social media speech—especially on newer platforms such as TikTok or Snapchat—are less representative of this type of speech, and more characterized by the new commercial interests created through the amplification of monetized speech.

The phenomenon of social media influencers has questioned the traditional boundaries between commercial speech and other forms of expression. Commercial speech is generally perceived as a liberty deserving less degree of protection vis-à-vis forms of expressions aimed to safeguards democratic values like political speech.Footnote 44 In other words, when the market economy meets the marketplace of ideas, it is not easy to draft a clear line between the two dimensions. Commercial advertising is usually considered the core of commercial speech. Nonetheless, it is challenging to define expressions as commercial when they meet political topics or, more generally, topics in the public interest. As observed by Post, “sometimes advertising is deemed to be public discourse rather than commercial speech, and sometimes expression that would not ordinarily be regarded as advertising is included within the category of commercial speech.”Footnote 45 This is evident in all the cases where commercial speech meets political speech, like in political campaigns.

The theoretical fight is between who believes that commercial speech deserves the same constitutional protection of other forms of expressions and those who believe that this kind of speech would not deserve constitutional protection or, at least, a lower degree. On one side, commercial speech is a piece in the democratic puzzles of expressions. In particular, these forms of expression would allow people to make choices for their own lives, thus, safeguarding democratic systems. Redish would argue that commercial speech could not be distinguished from any category of protected speech because it can provide information to the public, producing positive effects on their personal lives and political decisions.Footnote 46 On the other side, commercial speech would not generate positive externalities but just feed business purposes oriented on profit maximization. As observed by Posner, “it seems paradoxical therefore to allow virtually unlimited regulation of the product—its price, quality, quantity, and the conditions under which it is produced—but to impose a constitutional obstacle, granted, a somewhat porous one, to the regulation of the sales materials for it.”Footnote 47

The core of the discussion is whether democratic principles protecting free speech can be extended to the economic realm, and this can contribute to the functioning of democracy.Footnote 48 Smolla clarified this point, observing that “[i]f one sees freedom of speech primarily as an aid to democratic self-governance, commercial speech is likely to be left out in the cold, for it does not in any obvious or direct way appear to advance the process of democracy.”Footnote 49 Indeed, the intersection of the market and democracy is not a new phenomenon. For instance, competition rules have been implemented to ensure media pluralism among traditional media outlets. At the same time, democratic values affect the market, defining limits to commercial speech through instruments of unfair competition. Therefore, the primary point in question is to understand whether a system tends to be a system of democratic markets rather than the market of democracy.

The intersection between commercial speech and the political field is crucial to understanding the boundaries of regulation of these forms of speech and which of the two poles prevail in one legal system. Beyond these poles, it is possible to observe a tendency towards the attraction of commercial speech within the field of political speech, thus, elevating the protection of the advertising or commercial communication to the highest constitutional rank between expressions. This phenomenon, named “magnetic effect,” can explain how the protection of commercial speech swings between the two poles, creating a hybrid area challenging regulatory interventions.

Therefore, focusing on the constitutional protection of the right to freedom of expression is a prerequisite to understanding the margin of protection of influencers’ marketing and the degree of public intervention in this sector. Within this framework, the European and US experience in this field can provide useful guidelines concerning the intersection between commercial speech and other forms of expressions. The debate about how to address influencers’ marketing in the political field cannot leave aside the constitutional paradigm of protection of speech in capitalist democracies.

I. Commercial Speech Meets Political Speech in the US Framework

It is no mystery that the US Constitution recognizes as paramount the role of free speech by granting quasi-absolute protection enshrined in the First Amendment.Footnote 50 At first glance, this broad frame of protection of the right to free speech would subject all forms of speech to strict scrutiny, no matter their content or intention, speaker or recipient. Instead, a closer look can show how there is at least one area of expressions enjoying a lower degree of protection in the US constitutional framework. More specifically, this is the field of commercial speech.

The caselaw of the Supreme Court can provide several clues on the degree of protection of commercial speech.Footnote 51 Indeed, unlike in the European framework, the Supreme Court has dealt with commercial speech since the first half of the last century.Footnote 52 In Valentine v. Chrestensen,Footnote 53 the Court denied that the First Amendment protects the advertising of a visit to a private submarine. Indeed, it is true that the First Amendment grants a broad framework of protection to the right to free speech, but it does not extend to “purely commercial advertising.” This decision shows that commercial speech was considered outside the constitutional umbrella of the First Amendment so that it was nothing more than a business activity subject to potential public interventions. This decision was, however, the result of the New Deal period represented by the expansion of the regulatory state in the aftermath of Lochner v. New York.Footnote 54 Nothing changed for twenty years, as also confirmed by the judgment of the Supreme Court in Cammarano v. US.Footnote 55 The classic definition of commercial expressions is about speech that “does no more than propose a commercial transaction.”Footnote 56 Emerson, indeed, considered commercial speech within the system of commerce and outside that of free speech or democracy.Footnote 57 Likewise, Meiklejohn shares a similar view considering commercial speech as outside democratic values and the political idea of self-government.Footnote 58 In other words, commercial communications would belong to a different legal dimension involving property rights rather than free speech.

Nevertheless, in New York v. Sullivan, the Court clarifies, inter alia, that the commercial newspaper does not make its content, including advertisements discussing public issues, as commercial speech.Footnote 59 From this point, the Supreme Court followed a different orientation. In Bigelow v. Virginia,Footnote 60 the commercial nature of an advertisement message was not enough to exclude the constitutional protection of the right to free speech. This case was the first recognition of the constitutional protection of commercial speech in the US system, but still it was just a first attempt. The Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council case was the true turning point in the field of commercial speech.Footnote 61 In this case, the mere economic nature of the message does not automatically exclude speakers or recipients from constitutional protection. According to Justice Blackmun, commercial speech would promote the free flow of commercial information that may be of “general public interest.” Therefore, the constitutional protection of commercial speech would be the result of the essential role of the information flow in democratic societies. In other words, the Supreme Court also acknowledges that commercial speech can support democratic values by ensuring that economic decisions are taken consciously. This movement from market to democracy seemed to signal a new wave of constitutional protection for commercial speech.

Nonetheless, a following decision defined “commercial speech a limited measure of protection, commensurate with its subordinate position in the scale of First Amendment values.”Footnote 62 The case Central Hudson Gas Corp v. Public Service Commission confirmed this trend.Footnote 63 This decision has become famous for the so-called “Central Hudson Test” built on a four-step commercial speech analysis.Footnote 64 In particular, the test is based on verifying the protection of the expressions in question under the First Amendment: The governmental interest to restrict free speech, the ability of public rules to protect a specific interest, and the necessity and proportionality of the public intervention in relation to the interest to protect.Footnote 65 On the one hand, this approach could paternalize commercial speech, opening the doors towards broad margins of public intervention.Footnote 66 On the other hand, this case does not recognize absolute discretion in regulating commercial speech. Indeed, public interventions are limited by criteria reducing the influence of speech regulation.Footnote 67 It is not by chance that this period has been defined as an “era of uncertainty.”Footnote 68

From that moment, the Supreme Court has expanded the boundaries of commercial speech.Footnote 69 In Sorrell v. IMS Health,Footnote 70 the Supreme Court addressed a case of discrimination against commercial speech applying strict scrutiny. In this case, regulation affected speech concerning prescription drugs coming from nonmanufacturer and manufacturers. This decision led to the recognition of a different level of protection of the right to free speech based just on the speaker’s commercial motivation.Footnote 71 Despite this case, which can be considered peculiar, it cannot be ignored that commercial speech still enjoys a lower degree of protection when compared to other expressions, especially political speech.Footnote 72

Even if commercial speech does not enjoy the same constitutional protection of other forms of expression, nevertheless its protection tends to increase when cases also involve political matters. It is possible to observe that the Supreme Court has explicitly dealt with cases at the intersection between commercial and political speech. Concerning corporate political speech, in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti,Footnote 73 the Court invalidated a Massachusetts law banning investments from influencing the electoral body adopting a content-based approach which does not focus on the speaker but on the message. While, on the one hand, this decision recognizes the role of corporations in the public debate, on the other hand, it contributes to blurring the line between commercial and non-commercial speech for political purposes. The result of this approach is that corporate speech tends to be absorbed by the higher safeguards protecting non-commercial speech.

Even outside the framework of strictly-political speech, the case In re Primus showed how the protection of commercial speech could be extended when it meets expressions in the public interest. In the case in question, the expressions of a lawyer informing clients about the availability of the legal services provided by the American Civil Liberties Union were considered to be of a political nature, thus, requiring more precision in public interventions restrictions.Footnote 74 This approach was also adopted in Riley v. Nat’l Fed’n of the Blind.Footnote 75 In a case involving the imposition of a “reasonable fee” for the solicitation of charitable contributions, the Supreme Court held that “even assuming that the mandated speech, in the abstract, is merely ‘commercial’, it does not retain its commercial character when it is inextricably intertwined with the otherwise fully protected speech involved in charitable solicitations, and thus the mandated speech is subject to the test for fully protected expression, not the more deferential commercial speech principles.”Footnote 76

Likewise, in Nike, Inc. v. Kasky,Footnote 77 the Supreme Court addressed a case involving the degree of protection for non-commercial messages by press releases and promotional materials. In other words, the question was whether the statements of a business entity involved in public debate should be considered as commercial speech because they could affect consumers’ opinions and, therefore, their purchasing habits. Although the case was settled after the Supreme Court returned the issue to the California courts for procedural reasons, Justice Breyer clarified in his dissenting opinion that the case in question would have involved the freedom to speak about public matters in public debate. According to Edwin Baker, free speech consists of the exercise of an individual freedom. Consequently, speech by business entities cannot be considered an exercise of liberty because of their business focus on profit maximization.Footnote 78 In other words, commercial advertising does not contribute to public discourse but just to feed the economic interest of the business, rectius speaker. Post also supported that commercial speech would fail to protect the First Amendment speaker-centric value.Footnote 79 Nevertheless, he focuses more on the “participatory” model of democratic self-governance, observing how commercial speech should also be defined by reference to constitutional values. Therefore, it is not just a matter of speech qualification, speaker, or recipient, but also of the intersection between commercial speech and constitutional values or the public interest.

This argument is crucial to understand how the values of free speech shape the definition of commercial speech and how much the notion of public discourse can influence the boundaries of protection and public interventions. So far, the analysis of the Supreme Court case law has shown an increasing extension of the limits of commercial speech within the constitutional framework of the First Amendment and an increasing magnetic force of political speech vis-à-vis commercial speech. From a first phase of marginalization, commercial speech has also been recognized as a public interest matter consisting of the right to be informed. The constitutional influence of political speech on the protection of commercial speech can also be analyzed when moving from the US framework to the European protection of freedom of expression.

II. Commercial Speech Meets Political Speech in the European Framework

The debate about commercial speech in Europe has not captured the same degree of attention. Indeed, in the European framework, there is not a commercial speech doctrine like on the other side of the Atlantic.Footnote 80

In Europe, freedom of expression can be observed from three different perspectives. First, from the perspective of international law when looking at the framework of the Council of Europe and the European Convention on Human Rights.Footnote 81 Second, the protection of freedom of expression is also enshrined at the EU level in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.Footnote 82 Third, national constitutions of each state protect freedom of expression despite some differences. It is worth focusing the attention on the Council of Europe and the Union framework to provide a comparative perspective with the US approach and caselaw of the US Supreme Court in the intersection between commercial and political speech.

Unlike in the US framework, the limitation to the right to freedom of expression is explicit.Footnote 83 This fundamental right, as interpreted by the caselaw of the ECtHR and ECJ, can be subject to limitations when balanced with the protection of other fundamental rights.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, this consideration does not mean that the right to free speech in Europe is not based on liberal roots as also shown by the first decision of the ECtHR on freedom of expression.Footnote 85

Within this framework, political expressions usually enjoy the highest degree of protection, higher than commercial speech. As observed by the Strasbourg Court, when political speech is involved, states cannot exercise a broad degree of discretion in regulating this kind of speech.Footnote 86 Indeed, restrictions should be “narrowly interpreted and the necessity for any restrictions must be convincingly established.”Footnote 87 Other forms of expression, especially commercial speech, leave a margin of appreciation to public authorities because states would be in a better position to balance fundamental rights and pursue legitimate interests at the national level.Footnote 88

When focusing on commercial speech, the starting point is the decision in X and Church of Scientology v. Sweden. Footnote 89 In this case, the former European Commission on Human Rights addressed a case involving a national injunction against the Swedish Scientology Church for misleading advertising concerning a device called “E-meter.” Beyond the fact that this case was the first opportunity to address the issues of commercial speech in Europe, it is worth focusing on how the Commission distinguished between information advertisements concerning religious matters and commercial advertisements about the offering of goods and services. The Commission acknowledged that, when religious speech meets commercial advertisements for the sale of goods for commercial purposes, these statements do not enjoy the protection granted to religious statements. Even more importantly, according to the Commission, the Swedish government had the authority to restrict this form of expression because Article 10(2) should be interpreted less strictly when commercial speech is involved. Nevertheless, commercial speech would enjoy constitutional protection, but “the level of protection must be less than that accorded to the expression of ‘political’ ideas, in the broadest sense, with which the values underpinning the concept of freedom of expression in the Convention are chiefly concerned.”Footnote 90 In other words, like in the US constitutional framework, commercial speech enjoys constitutional protection but with a lower degree.

Some years later in Casado Coca v. Spain,Footnote 91 the Strasbourg Court clarified the boundaries of commercial communications in the European framework. The opportunities came from an administrative sanction to a lawyer for advertising legal services. The Court underlined the role of advertising as a channel for citizens to be aware of the characteristics of goods and services. Nonetheless, despite this critical role, commercial speech can be subject to restrictions, especially to tackle unfair competition and misleading advertising. Even beyond this framework, commercial speech can also be restricted when truthful messages are involved “to ensure respect for the rights of others or owing to the special circumstances of particular business activities and professions.”Footnote 92 In this case, the sanction was not considered a disproportionate interference with commercial freedom of expression violating Article 10. Indeed, the Strasbourg Court clarified that “Article 10 does not apply solely to certain types of information or ideas or forms of expression, in particular, those of a political nature; it also encompasses artistic expression, information of a commercial nature.” Yet, national authorities enjoy a broad margin of discretion in dealing with unfair competition and advertising rather other forms of speech.Footnote 93

The Strasbourg Court had the opportunity to address the intersection between commercial speech and other forms of expressions. In Barthold v. Germany,Footnote 94 a veterinarians’ association charged one member with a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct and the Unfair Competition Act for its statement in a newspaper. The Court recognized a violation of freedom of expression because the injunction does not strike a fair balance failing to take into consideration the role of the press. It is not always possible to distinguish information, opinion, and advertising elements. Likewise, in Stambuk v. Germany,Footnote 95 the fine imposed on an ophthalmologist for the publication of a newspaper about a new laser operation technique and its success was a violation of freedom of expression as protected by Article 10. The Court observed that advertising plays a crucial role for citizens so that truthful advertising should be subject to strict scrutiny.Footnote 96 This is because, in the case in question, the press informed the public about a matter of public interest “in a language and manner of presentation destined to inform a general public.”Footnote 97 In other words, the Strasbourg Court did not focus on the potential nature of the content in question but the article’s informative effect over recipients.

In Markt Intern & Beerrmann v. Germany,Footnote 98 the Court dealt with a multifaceted case deriving from a national injunction on a publishing firm’s editor-in-chief for unfair competition against the promotion of the interest of small and medium businesses vis-à-vis large-scale business entities. The Court did not recognize a violation of freedom of expression in this case. Among the reasons was that these anticompetitive behaviors have not reached the general public but just a limited number of traders, rectius recipients. Indeed, the Strasbourg Court underlined that in “a market economy an undertaking which seeks to set up a business inevitably exposes itself to close scrutiny of its practices by its competitors. Its commercial strategy and the manner in which it honors its commitments may give rise to criticism on the part of consumers and the specialized press … However, even the publication of items which are true and describe real events may under certain circumstances be prohibited.”Footnote 99 It is clear how, in this case, the Court approached the restriction in question as a matter of commercial speech without that public relevance that could have led to consider the publication in question as non-commercial speech. Likewise, the Strasbourg Court addressed another case involving unfair competition in Germany. In Jacubowski v. Germany,Footnote 100 the publication of a press release by an employee in its news network concerning the reorganization of personnel—which also commented upon the applicant’s qualifications and his performance as a journalist and managing director—was not considered a form of expression deserving more protection to reduce the margin of appreciation of public authorities in interfering with this kind of speech. Like in the previous case, the publication did not involve either the public or a subject of public interest, thus leaving the Strasbourg Court free to refer to the states’ margin of appreciation.

The relevance of the public interest in the field of commercial speech was more evident in Hertel v. Switzerland.Footnote 101 In this case, the national injunction concerned the findings of a scientist published in a lay magazine. The Strasbourg Court went beyond the qualification of these expressions as purely commercial statements. The Court acknowledged that the article on microwaves should be framed in a debate affecting the general interest—for example, public health—thus deserving strict scrutiny. In Herbai v. Hungary,Footnote 102 the applicant launched a knowledge-sharing website about human resources management with publications and events. The applicant’s employer terminated the contract, claiming a breach of confidentiality standard and an infringement of its economic interests. Once the Strasbourg Court recognized that commercial speech leaves a broad margin of discretion to public authorities, the Court applied a higher scrutiny, finding a violation of freedom of expression by national authorities which had excluded the aforementioned expression from constitutional protection just because of their commercial nature and without taking into account their public interest.

The intersection between commercial speech and other forms of commercial speech seems even self-evident when focusing on Vgt Verein Gegen Tierfabriken v. Switzerland,Footnote 103 where an animal rights association planned to advertise a campaign to encourage people to reduce their consumption of meat. In this case, although the Court recognized a broad margin of discretion of domestic authorities to restrict commercial speech, this kind of advertising was a non-commercial expression because there was no persuasion to change the purchasing habits of consumers, just capture their attention on a controversial topic. Therefore, because the advertising was of a political nature, the authority of discretion should be considered more limited rather than in cases of mere commercial speech and, therefore, the prohibition was considered a disproportionate interference with freedom of expression. Likewise, in Lehideux and Isorni v. France,Footnote 104 the publication of a newspaper advertisement concerning World War II crimes was considered a promotion of the historical debate protected by strict scrutiny. The Strasbourg Court underlined that the freedom of expression also covers “information or ideas that are favorably received or regarded as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock, or disturb.”Footnote 105

Nevertheless, this public interest approach was questioned in other decisions. In the case of Demuth v. Switzerland,Footnote 106 the Strasbourg Court showed a different approach to the intersection between commercial and non-commercial speech. The case involved expressions on a television program concerning not only cars but issues of public interest such as energy and environmental issues. Despite the lack of purely commercial interest, the Court did not underline the importance of the expressions for the public interest but focused on the purposes of the company’s advertising. The Court underlined that the aim of the transmission was commercial and, therefore, a lower degree of protection should apply. In a similar case involving an organization advocating for animal rights, the Court instead took into consideration the public interest. In Peta Deutschland v. Germany,Footnote 107 the case concerned an advertising campaign against battery animal-farming called “The Holocaust on your plate.” The advertising in question involved topics of public interest like animal and environmental protection. Therefore, the Court applied strict scrutiny to assess the interference with freedom of expression. Nevertheless, the balance with other fundamental rights, in particular human dignity, has led the Court to consider the public interference in the case in question as proportionate, thus without recognizing a violation of Article 10.

In Animal Defenders International v. the United Kingdom,Footnote 108 the Strasbourg Court seems to have adopted once again a restrictive approach even in the field of political speech in a case concerning the keeping and exhibition of primates and their use in television advertising. The applicant maintained that the prohibition was disproportionate because it prohibited paid “political” advertising by social advocacy groups outside of electoral periods. Nonetheless, the Court did not recognize a violation of Article 10 because the ban on political advertising can protect the democratic debate and avoid distortion by powerful financial groups able to influence the media. Likewise, in Remuszko v. Poland,Footnote 109 the Court recognized that the advertisement of a book can contribute to promoting a debate in the public interest, such as the mission of the press in Polish society. However, even in this case the Court looked at the aims of the publication whose scope was essentially directed to promote the distribution and sales of his book. In Mouvement Raëlien Suisse v. Switzerland,Footnote 110 the Strasbourg Court addressed a religious poster campaign. According to the Court, the poster campaign in question sought mainly to draw the attention of the public to their websites, where there were just incidentally social or political ideas. The Court takes the view that the type of speech in question is not political because the main aim of the website in question is to draw people to the cause of the applicant association and not to address matters of political debate in Switzerland. Even if the applicant association’s speech falls outside the commercial advertising context, it is nevertheless closer to commercial speech than to political speech per se, as it has a certain proselytizing function. The state’s margin of appreciation is therefore broader.

Within this framework, it is not easy to outline a clear commercial speech doctrine in Europe. This is mainly the result of the specific focus of the Strasbourg Court influenced by cases in question and the inter partes effects of its decision. Nevertheless, it is possible to define some patterns. First, it is possible to observe that, like in the US framework, the Court addressed very similar issues in the field of commercial speech, like professional advertising and corporate speech. Second, the cases have also shown that commercial speech enjoys a lower degree of protection, thus, leaving public authorities a wide margin of appreciation when commercial expression is involved.Footnote 111 Third, and even more importantly, the Strasbourg Court has dealt with many cases involving the intersection between commercial and political speech. In these cases, like in the US framework, courts have attracted commercial speech in the protection of political speech. This magnetic effect is positive for those who believe that commercial speech can foster democratic values. On the opposite, such attraction could lead to troubling results limiting the interferences of public actors just because commercial speech hides itself beyond public interest’s narrative.

D. Monetized Political Speech: Where Market Meets Democracy

So far, we looked at the constitutional balance between political and commercial speech to determine which type of expressions can be more prone to limitations, such as those stemming out of mandatory norms embodying public interest. One way of looking at public interest when commercial intent is involved is to consider how fair commercial practices are, and to what extent they are prone to manipulating consumer behavior. As we indicated before, influencer marketing is a timely and suitable vehicle for political advertising, and this development warrants a closer look at the disclosures made in this process. This section puts forth the argument that political speech made with the commercial intent of obtaining financial gain should fall under the ambit of consumer protection disclosure rules, the violation of which can be interpreted as an unfair commercial practice.Footnote 112

There are strong discrepancies between the way in which US and EU law deal with unfairness in business practices: The EU has a cohesive—albeit very open to interpretation—framework surrounding unfair commercial practices as regulated in a maximum harmonization directive, which has a black list, as well as consistent interpretations from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The US has shaped a somewhat inconsistent fairness doctrine based on caselaw and further shaped by the FTC. Consumer protection rules in the EU have a mandatory nature, in light of consumer protection regulation being adopted on the basis of Article 114 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), as a way to further the internal market by providing consumers with a high standard of protection. In the US, case law has not led to a general prohibition against unfair competition of the same nature. Still, similarities can be observed as well: The average consumer test is used in both jurisdictions to determine when practices are unfair.Footnote 113

In the United States, unfair competition or unfair commercial practices are not subject to a harmonized regulatory framework, but the landscape has been rather defined as “courts try[ing] to stop people from playing dirty tricks.”Footnote 114 To consolidate existing case law and provide advertisers with a cohesive framework of good practices, the Federal Trade Commission drafted the Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising,Footnote 115 which will be revisited after a request for public comments.Footnote 116 The most important element of the Guides relates to the disclosure of material connections which may exist between a marketer and an endorser. In other words, if there are considerations such as payment, proximity between marketer and endorser—for example, employee/employer relationships—which may materially affect the weight or credibility of the endorsement, the Guides mandate this type of connection to be disclosed to the broader audience.

In the EU, unfair competition rules are brought together in the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD).Footnote 117 The UCPD is a maximum harmonization instrument of consumer protection, with the aim of establishing uniform rules on unfair business-to-consumer (B2C) commercial practices in order to support the proper functioning of the internal market and establish a high level of consumer protection.Footnote 118 The structure of the main provisions of the UCPD is laid down as follows. Article 5 sets the general clause according to which a commercial practice is unfair if it satisfies a two-tier test: (i) “it is contrary to the requirements of professional diligence”; and (ii) “it materially distorts or is likely to materially distort the economic behavior with regard to the product of the average consumer whom it reaches or to whom it is addressed, or of the average member of the group when a commercial practice is directed to a particular group of consumers.” In addition, the same article acknowledges two particular types of commercial practices which may be deemed unfair: (i) misleading practices as set out in Articles 6 and 7; and (ii) aggressive practices as set out in Articles 8 and 9. These two sets of Articles include their own, more specific tests which derogate from the general test in Article 5, although they are set around the same principle—that manipulative commercial practices are prohibited. A blacklist is annexed to the UCPD and contains a total of thirty-one practices which are in all circumstances considered to be unfair. Most importantly for influencer marketing, among those are practices added by the Omnibus Directive, including point 23c, according to which “[s]ubmitting or commissioning another legal or natural person to submit false consumer reviews or endorsements, or misrepresenting consumer reviews or social endorsements, in order to promote products” is not permitted. In addition, point 11 of the Annex also prohibits paid advertorials that are not disclosed, as has been the case with native advertising.

Consumer protection rules on disclosures, wherever they exist, are based on the idea that when engaging in transactional behavior, the information asymmetry between an individual and a company ought to be remedied by giving the weaker party in that transaction information which can aid decision-making. For consumers, this decision-making process traditionally relates to goods and services: Whether online or offline, the experience of a consumer entering a store and looking to purchase something is very clearly governed by contract and consumer rules. Both categories of rules stem from the private law consideration of freedom of contract, albeit limited by the public interests fueling the mandatory boundaries of this freedom in specific jurisdictions. This is surely the case under European consumer protection, although a different picture emerges when considering the much narrower scope of consumer protection in the US. In parallel with positive law, academic scholarship has been exploring the public aspects of private consumer transactions, as well as the private aspects of relationships in the public sphere for a while now,Footnote 119 emphasizing the similarities between the status of consumers and that of citizens. Nowhere is this similarity more prevalent than on social media, where users can look at commercial ads, follow their favorite political candidates, and be entertained by various monetized forms of self-expression, all at once. In this space, a photo of Donald Trump endorsing products stacked on his desk in the Oval Office, and an Instagram post using affiliate links to advertise a popular hair vitamin product have similar advertising characteristics (see Figure 2). Indeed, more empirical evidence is necessary to understand the customer journey vis-à-vis political branding, especially in the context of social commerce, which diffuses the boundaries between public and private interests. However, when posts are made on social media on the basis of transactions establishing their commercial nature, these posts ought to be governed by consumer protection. This normative argument builds on three specific points.

Figure 2. Instagram posts by a politician and an influencer promoting products.

First, whether speaking of commercial or political speech, monetization is inherently linked to advertising. Currently, a dispersed landscape of national rules on political advertising are making it difficult to understand what is and is not allowed during electoral campaigns, or in some cases beyond campaigns.Footnote 120 Instead of pursuing regulatory reforms aimed at political advertising to include newer categories of stakeholders who can engage in monetization, using the disclosures which are already native to commercial speech via consumer protection, we argue, is in the interest of many stakeholders of the political speech monetization process.

Second, the online consumer experience has been vastly expanded through user-generated content and content sharing, which entails that in the past decade there has been a shift from e-commerce to social commerce.Footnote 121 This phenomenon has already blurred the lines between commercial and non-commercial speech, and the monetization of self-expression only adds to this confusion. For instance, when visiting her Instagram account, the followers of Dutch influencer Famke Louise can see, among others, ads for makeup and beauty products, posts relating to her TV appearances, but also personal posts relating to the Covid-19 pandemic. Some of her social media content earlier in the pandemic was paid for by the Dutch government to promote the wearing of masks during a global health pandemic,Footnote 122 but more recent content showing a polar opposite opinion relating to whether citizens should abide by national social distancing rules seems to evoke more genuine, unpaid opinions. The only way of telling whether her opinions—as well as those expressed by other influencers speaking on political matters, like Rezo—are not sponsored is to have access to all the contracts concluded by her, which is unattainable. At this point, popular influencers are generally aware that they have to disclose advertising, but grey areas of influencer marketing—for example, barter—as well as poor enforcement have allowed them to maintain a situation where their endorsements remain under-disclosed. Adding the political speech dimension to this type of monetization takes away any clarity which consumer protection may have instilled in the social media space, risking inconsistent doctrinal and judicial interpretations.

Third, even though companies—including those of influencers—also have a right to engage in political speech, distinguishing when this speech is motivated by commercial gain and when it is separated from it is a particularly difficult task in the realm of social commerce.Footnote 123 Take, for instance, the Instagram post made by US shoe brand Stuart Weitzman on their official account on August 25, 2020: A photo of long boots featuring a vertical message that reads “Vote” (Figure 3). The photo also uses one of the commercial affordances made available by Instagram, namely product tagging, where the product is named, as well as the price. From this post, it takes two additional clicks to purchase the goods. Would this qualify as political—including “issue-based” messaging—or commercial speech? On the one hand, companies can make political statements that are not as such connected to the promotion or sale of goods. On the other hand, if goods are linked to such an extent that consumers can immediately jump into a transaction with the brand, it can be argued that the commercial intent is more predominant than the intent of engaging in an act of political speech, even though the content of the post reads that all proceedings will be donated to a non-partisan organization. If the brand paid influencers to promote the boots, would there be an obligation to disclose the endorsement? Following the argument relating to the prevalent commercial intent, we would argue this question ought to be answered in the positive. And even if the brand paid influencers to market products and share their political opinion, our answer is still positive.

Figure 3. Shoe brand Instagram post.

To summarize, the normative argument explored above consists of the proposal that political advertising occurring in the context of social commerce which is based on commercial intent ought to be subject to consumer disclosures. Revisiting the classification of influencers who engage in political speech which we explored in section 2 of this article, we consider it could be applicable to social media influencers as political opinion leaders, as in specific jurisdictions, influencers have already been called upon by courts to disclose not only when they make an endorsement, but to bear the negative duty of also disclosing when they are not making endorsements.Footnote 124 While this approach has been criticized as being a too-strict interpretation of disclosure duties, it does bring into attention the fact that a social media account—the purpose of which is to monetize content—is a commercial space, and this must be clear for consumers engaging with that space. As for the other two categories we identified, namely social media influencers turned politicians, and politicians as social media influencers, these categories touch upon a different constellation of rights and obligations. Ideally, their increased engagement in monetization would be treated as an expression of commercial speech, but it is worth noting that additional rules come into play, such as electoral laws. These laws often govern political advertising by political actors. Looking at specific regulation on electoral disclosures falls outside of the ambit of this article, as transatlantic comparisons are rather difficult in this field: Each Member State will have its own political advertising regulation, which will be soon enriched by the national implementation of the Commission’s recent proposal on the transparency and targeting of political advertising.Footnote 125

The normative argument in this Section might be considered rather controversial when keeping in mind some of the current limitations in existing consumer law rules, such as their material scope. In the US, the Influencer Guidelines do not specify this limitation, yet the UCPD does. According to Article 3(1), the material scope of the prohibition of unfair commercial practices is limited to “practices […] before, during and after a commercial transaction in relation to a product.” However, Article 2(c) clarifies that “product” is to mean “any good or service including immovable property, digital service and digital content, as well as rights and obligations.” The Commission guidance for the interpretation of the UCPD also clarifies that the scope also includes services.Footnote 126 Political speech is by no means a product. For the UCPD to be remotely relevant for this situation, we would need to consider the concept of monetized political speech as a service. In addition, recital 13 of the UCPD Preamble, which refers to “unfair commercial practices which occur outside any contractual relationship between a trader and a consumer or following the conclusion of a contract and during its execution,”Footnote 127 shows that the product or service may be part of the transaction, but unfair commercial practices can go well beyond the transactional dimension. Lastly, there might be a problem with the interpretation of the status of “trader,” as a NGO paying an influencer for political speech may not fall under this category. However, platforms and influencers do, which is why using consumer protection rules is even more justified because these stakeholders are all part of the supply chain of advertising, political or not.

E. Conclusion: The Magnetic Effect–Same Problem, Different Label

This research illustrates a long-standing, fundamental tension arising between different protective regimes that give rise to individual rights: Consumer law and freedom of expression. Recalling the example of the Instagram influencers that were paid to boost Bloomberg’s political campaign: The accounts pertaining to these influencers, which regularly posted curated content made by other content creators on various platforms, allegedly received around $150 to post a meme about Bloomberg in order to increase his appeal towards younger voters.Footnote 128 On this specific occasion, the posts were disclosed as advertising, not only using the Instagram interface which allows the possibility to indicate “paid partnerships,” but also in the text of the post: “… and yes this is really #sponsored by @mikebloomberg.” However, in influencer marketing, advertising remains under-disclosed,Footnote 129 and this trend is very likely going to transition into the monetized political speech category. As digital operations become more and more important for politicians, they will increasingly turn to influencers to gain their endorsement.Footnote 130 We have underlined how, unlike politicians subject to other forms of obligations, influencers engaging in political speech fall within a grey area between market and democracy. This is why we argue that they should be required to disclose their source of revenues due to the prevalence of the commercial nature of their messages.

This context illustrates the tensions between constitutional freedoms and consumer obligations. At first sight, in the Bloomberg example, the strategist behind the social media plan of monetizing political support acknowledged the need to abide by the FTC’s Endorsement Guidelines, although in the US, the First Amendment reigns supreme, and consumer policy does not enjoy the same nature as constitutional protections. In comparison, consumer rules are recognized in the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights in Article 38, without being given less importance than freedom of expression in Article 11.

The mix of constitutional and consumer law outlines a legal framework encouraging or limiting the possibility for influencers to monetize political speech. The importance of these rules for monetized political speech is a practical manifestation of the magnetic effect presented in the prior section. On the one hand, political speech can be seen as a highly protected category of speech, regardless of where exactly it is expressed: On social media, in newspapers, on television, etc. From this perspective, anyone who expresses themselves publicly regarding opinions, beliefs, and thoughts they might have or hold with respect to political matters should be covered by this protection. On the other hand, if this speech comes from persons who monetize content for a living, and are paid to review, advertise, or endorse brands, it can be seen as commercial speech which can be limited by mandatory rules belonging to consumer protection regimes. In the case of monetized political speech, the public good is the disclosure of paid advertising, so social media users know when their favorite influencers are paid to promote a certain political candidate.

To understand how to deal with the magnetic effect, it is worth looking once again at the protection of freedom of expression in the EU and US. Even if we have seen that that the magnetic effect could raise concerns on both sides of the Atlantic, still the results could be different. The protection of free speech in the US could ban any regulatory intervention in this field. Whereas, when focusing on the European framework, we have seen how commercial speech has been highly regulated. And this is not by chance. This much depends indeed on how constitutional democracies conceive freedom of expression.

Basically, this is the clash between a paradigm of liberty which is reluctant to paternalism and regulation like the US framework and a framework of dignity in Europe which takes more into account the role of public actors in safeguarding other interests deserving to be protected. We should not forget that freedom of expression is not the only constitutional pillar of the European system. Indeed, other values like the health or the protection of minors could lead to a different approach to the gap between market and democracy.

Therefore, when addressing the monetization of political speech across the Atlantic, the magnetic effect can play a different role due to the different constitutional values. Consumer law in Europe could play an important role in providing guidelines to break such hide, while in the US framework the lack of a solid legal framework of consumer protection could lead to an increasing attraction of commercial speech within the framework of political speech without recognizing rights of users to understand and challenges deceptive behaviors.