The New York Hippodrome theatre brought together many different types of performance on its massive stage. Its opening production in 1905, for instance, included circus acts, a ballet, and a fictionalized Civil War battle (Fig. 1). Many of the acts focused on a key feature in the theatrical environment, a water tank beneath the apron of the stage that could be filled to a fourteen-foot depth. High divers plunged into the tank; in shows with an “ice ballet,” its water was frozen into a skating rink; for a production of HMS Pinafore, a replica ship floated in its water with Brooklyn Navy Yard sailors in the rigging. Yet one tank act repeated and was recalled more than any of the others: a phalanx of women in martial costumes who marched solemnly, row after row, into the water and disappeared.

Figure 1. Vintage postcard view of the New York Hippodrome showing signage for The Raiders and A Yankee Circus on Mars (12 April–9 December 1905). Souvenir Post Card Co., New York. From the collection of Michael Gnat.

Somewhere between a military drill and a magic trick, the sight of the girls submerging in the tank stood out even among the many spectacular acts. Like other large chorus routines, it highlighted the group's size and synchronization. What made the act most striking, though, was its end in self-destruction. Hippodrome prima donna Nanette Flack recounts the scene's effect: “With each descending row, the gasps from the audience became louder and louder. It was realized that over a hundred girls weren't drowned at every performance, but the effect was absolutely weird, and how it was accomplished mystified nearly everyone beyond the footlights.”Footnote 1 By the early 1920s, the disappearing girls—sometimes called mermaids or “water guards”—were a standard part of the show.Footnote 2 Programs for Good Times (1920) and Better Times (1922) called attention to their absence, following their act listing with the question, “Where do they go?” In the genealogy of this evolving act, I suggest that the audience's ambivalent fascination with the disappearing mermaids stood in for a broader cultural interest in and anxiety over modern white women's mobility.

The New York Hippodrome was most dominant as a cultural institution during the second half of the Progressive Era, a period in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American life when technological innovation, political reform, and waves of immigration and internal migration reshaped the country. One of the defining characteristics of this period was the growing presence of young, active women within urban life.Footnote 3 Women moved to American cities for economic opportunity, engaged in sports and dancing that allowed them increasing physical freedom, and, while grouped together into large assemblies, demonstrated for their right to strike, and protested for their right to vote.

Women dominated the popular stage during this time as well. Whether they sang, imitated other celebrity performers, or danced the “Dance of the Seven Veils,” female performers earned the most notice in turn-of-the-century vaudeville shows.Footnote 4 The most characteristic female figure on the Progressive Era stage, though, was the chorus girl—or, to use a term more particular to the era, the group of chorus girls that made up a “girl act.”Footnote 5 Groups of eight and sixteen petite dancers trained by British dancing master John Tiller appeared on Broadway around the turn of the century.Footnote 6 Dubbed the “Pony Ballet,” they performed in larger groups with tighter synchronization than had been seen on American stages. This early iteration of the Tiller Girls inspired American dance directors of the era, particularly Ned Wayburn.Footnote 7 Girl acts like these, along with the large groups of supernumerary performers in Victorian spectacles, model the work done by the Hippodrome chorus on a far larger scale. The most striking visual effects arose from the size of the group and the coordinated costumes, height, and movements of its members.

One additional element was coordinated: girl acts that performed on Broadway, in “big time” vaudeville, and in roof garden shows were almost uniformly made up of white women.Footnote 8 Ned Wayburn's girl acts employed minstrel show techniques—his “Minstrel Misses” used burnt cork to blacken their faces onstage, for instance—as well as military drill formations. “As his reliance on minstrel show imagery decreased,” M. Alison Kibler writes, “his focus on the strict management of chorus girls and the establishment of drill-like precision increased.”Footnote 9 In both cases, emphasis is placed on the staging of uniform, white femininity. Wayburn became the choreographer for the Ziegfeld Follies; Linda Mizejewski has analyzed how same whiteness was bestowed on the Ziegfeld Girl.Footnote 10 Busby Berkeley's choruses show the progression from stage to screen of what Joel Dinerstein calls “the standardized white girl in the pleasure machine.”Footnote 11 Hippodrome choruses participated in the same staging of standardized white femininity that took place in popular performance venues across New York City, but the staging took place at a larger scale and at a more abstract remove.

The venue was far larger than those where other girl acts appeared, with more than fifty-two hundred seats for audience members, who faced a stage twelve times the size of one in a typical Broadway house.Footnote 12 Because of the distance from the audience and the large number of performers needed for each show, Hippodrome chorus members did not have to be especially pretty or shapely. Indeed, one of the most remarkable facts about the Hippodrome chorus was that it did not limit itself to young women. In her memoir, circus performer Tiny Kline observes “The Hippodrome show was the first I have known where youth was of no consequence in the chorus—three generations danced side by side if they matched up in size.”Footnote 13 Thinking about the Hippodrome chorus through this lens emphasizes the whiteness of the chorus girl in these spectacles. Black performers could appear on benefit nights or as part of specific scenes, but the Hippodrome chorus reinforced the norms of white femininity as the backdrop and the default setting for the action taking place.Footnote 14

From its third season onward, the New York Hippodrome was associated with a unique form of girl act, one where women either emerged from or disappeared into the stage apron's water tank. In the following sections, I discuss the evolution of the Hippodrome mermaid as a key figure in these spectacular performances, one who reinforced the status of an endless parade of white women as both a common fear and a common fantasy in this era. Women emerging from and descending into the water created unique stage pictures, ones that united a sense of beauty with one of peril.

Neptune's Daughters

Real water had appeared on New York stages long before the construction of the Hippodrome. In 1840, a Bowery Theatre production incorporated water effects to replicate the nautical melodramas that could be seen at Sadler's Wells in London.Footnote 15 Sensation melodramas of the post–Civil War era might include an aquatic scene where the heroine was rescued from drowning. Producer David Belasco often incorporated water into the staging of his dramas, from a scene in Hearts of Oak where two washerwomen douse each other with their buckets, to the working wells and taps included in his hyperrealistic onstage infrastructure.Footnote 16 Indeed, we might understand the prevalence of real water in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century performance as another example of staging techniques that helped audiences to navigate the shock and overstimulation of modern life.Footnote 17

The first owners of the New York Hippodrome, Frederic Thompson and Elmer Dundy, incorporated aquatic features into their shows from the beginning. The theatre opened with a double bill: a fantasy spectacle called A Yankee Circus on Mars, and a historical drama of the Civil War called Andersonville: A Story of Wilson's Raiders. The second act of Andersonville staged the “Battle at Rocky Ford Bridge of men and horses in which Participate the Thompson & Dundy stud of Plunging Horses”; the horses and their riders swam across the tank as part of the battle scene.Footnote 18 Thompson and Dundy's A Society Circus opened in December 1905; this extravaganza ended with a sort of aquatic pageant called “Court of the Golden Fountains” (an illustration of which appears on this issue's cover). Reviewing the show for The Billboard, Walter K. Hill says, “The monster water-tank is used as a front setting for the scene and building up from there for tier after tier the entire company is massed in rows of gorgeous coloring and bathed in floods of light.”Footnote 19 Some cast members pose as caryatids holding up the fountains, but there seems to be little chance of anyone actually getting wet. Where the Raiders scene depended on risk for its emotional impact, this scene gives the audience a chance to appreciate the beauty made possible by the onstage water. A Society Circus was the last New York Hippodrome show produced by Thompson and Dundy. The show made far less money than its predecessors had; critics suggested that it failed due to lack of direction.Footnote 20 The Shubert Brothers then took over the management of the theatre, with the support of investors.

It was in the Hippodrome's third season that the Shuberts first employed the water feature in a way that came to be associated with the theatre for the rest of its history. Neptune's Daughter, which closed the bill, combined the risks taken by the plunging horses and riders in The Raiders with the visual beauty that animated the “Court of the Golden Fountains.” The program proclaimed Neptune's Daughter be a “romantic operatic extravaganza.”Footnote 21 The first act drew on the melodramatic tradition, including a storm and shipwreck off the coast of a French fishing village. A baby saved from the wreckage is named Annette; she is adopted by the family who saves her. As the second act begins, the village celebrates Annette's impending marriage to her foster brother, Pierre. When Pierre sings about having a girl in every port, Annette jealously breaks off their engagement. This is the moment when mermaids appear: eight chorus girls in metallic wetsuits and jeweled headdresses emerge from the tank. They swim and sing, ask Pierre and his fellow fishermen to join them at the bottom of the sea, and dive under the water once again. When Annette finds out what happens, she calls upon Neptune to take her there as well. The third act opens with a vividly costumed ballet of sea creatures, after which the young lovers are reunited and married under the sea.

Aquatic performance at the New York Hippodrome developed alongside a growing interest in swimming as a form of exercise for modern women.Footnote 22 The name of the title character in Neptune's Daughter makes that connection more explicit: the show developed just around the time that Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman first appeared on the radars of American newspaper readers. Kellerman had attempted to swim the English Channel in the summer of 1905 and broke women's long-distance swimming records in Vienna in June 1906. A woman's page article from August 1906 mentions Kellerman among a growing number of women who competed in swimming and water sports while still maintaining their femininity.Footnote 23 She had performed swimming and diving exhibitions in Melbourne and London but not yet in the United States. Indeed, her first American tour began in April 1907—midway through the run of Neptune's Daughter. Kellerman starred in later Hippodrome stage spectacles, most notably in The Big Show (1916), where her water spectacle shared a title with one of the characters in Neptune's Daughter: “The Queen of the Mermaids.”Footnote 24 The two shows share a larger sense that women who can swim with such facility are otherworldly creatures, more than human.Footnote 25 This sense of separation continues in the work of contemporary “merformers” who use silicone tails with monofins in order to maintain the fantasy of their otherworldliness and help them swim in a more fishlike way.Footnote 26

Swimming ability was still an unexpected novelty among performers in the initial press coverage of auditions for Neptune's Daughter. An article in the New York Tribune proclaimed that Louise Gribbon, who played the title role, was “the first singer on record to dive into a tank in order to obtain an engagement.”Footnote 27 There was no guarantee that performers could swim, nor that they would want to do so. Olive North, a featured actress in prior Hippodrome shows, declined the part when she learned how extensive the water performance would be.Footnote 28 A swimming race served as the audition for her replacement. The interested performers, dressed in swimsuits, “were lined up on the 44th street end of the tank and told that the young woman who swam first to the further end of the tank would be given the part.” Miss Gribbon won the race; being “a pretty young woman, with an excellent soprano voice,” she fulfilled the other requirements for the part as well, and so was cast.Footnote 29

In the Progressive Era, swimming tended to be a single-sex, class-stratified experience. It was not until after the Great Migration, historian Jeff Wiltse observes, that “whites of all social classes” used race-segregated swimming pools to “forge a common identity out of their shared whiteness.”Footnote 30 But chorus lines too were segregated, and aquatic performance in this era drew on the chorus line for its participants; the “common identity” forged, therefore, was both raced and gendered. One newspaper story described a competition between Hippodrome mermaids and showgirls from the then-current Casino Theatre opera Princess Beggar. The challengers from the Casino reportedly begged off when they saw how comfortable the Neptune's Daughter cast members looked in the tank: they were “at home in the water” and “swimming like porpoises.”Footnote 31 This left the Hippodrome mermaids to race among themselves before a sizable crowd of chorus members and friends.Footnote 32 (The Shuberts produced both shows.) The story creates a kind of utopia of white femininity with exercises that take place apart from the ticketed performances—either before the show is cast or while its performers are relaxing outside of work—which are experienced only secondhand by readers.

The mermaid performers may have been celebrated as skilled swimmers in the press, but they were not very mobile during their performance. The Hippodrome mermaids emerged, sang, and dove back under the water, meaning that their athleticism was implied rather than foregrounded. This stood in sharp contrast to another popular show from the same theatrical season: the Anna Held vehicle A Parisian Model, produced by her romantic partner Florenz Ziegfeld, demonstrated the mobility of the chorus more directly onstage with a featured “Roller Skate Ballet” of a dozen women. Reviews emphasized that the mermaids maintained their feminine appeal even when emerging from the tank. “Popular interest,” the Variety reviewer Rush notes, “centred in the spectacle of beauteous mermaids rising from a sea of real water without a suspicion of dampness in their curls.”Footnote 33 For women who swam at the turn of the twentieth century, bathing caps were seen as dowdy, and wet hair was unsightly; the mermaids’ costumes followed the fashions noted in the newspapers a few years earlier, which celebrated bathing wigs of ringlets that kept the wearer's hair dry. In this way, the early aquatic performers of the Hippodrome are forerunners of the skilled swimming stars in Billy Rose's Aquacade (1939–40) who were asked to downplay their athletic prowess in favor of feminine appeal. Eleanor Holm was an Olympic gold medalist, and Esther Williams would have attended the 1940 Summer Olympics that were canceled due to the outbreak of World War II: when they performed in the Aquacade, Rose encouraged them to “swim pretty,” keeping their heads above the water to maintain their hairstyle and makeup.Footnote 34

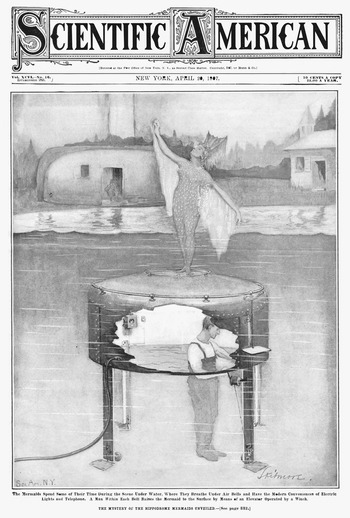

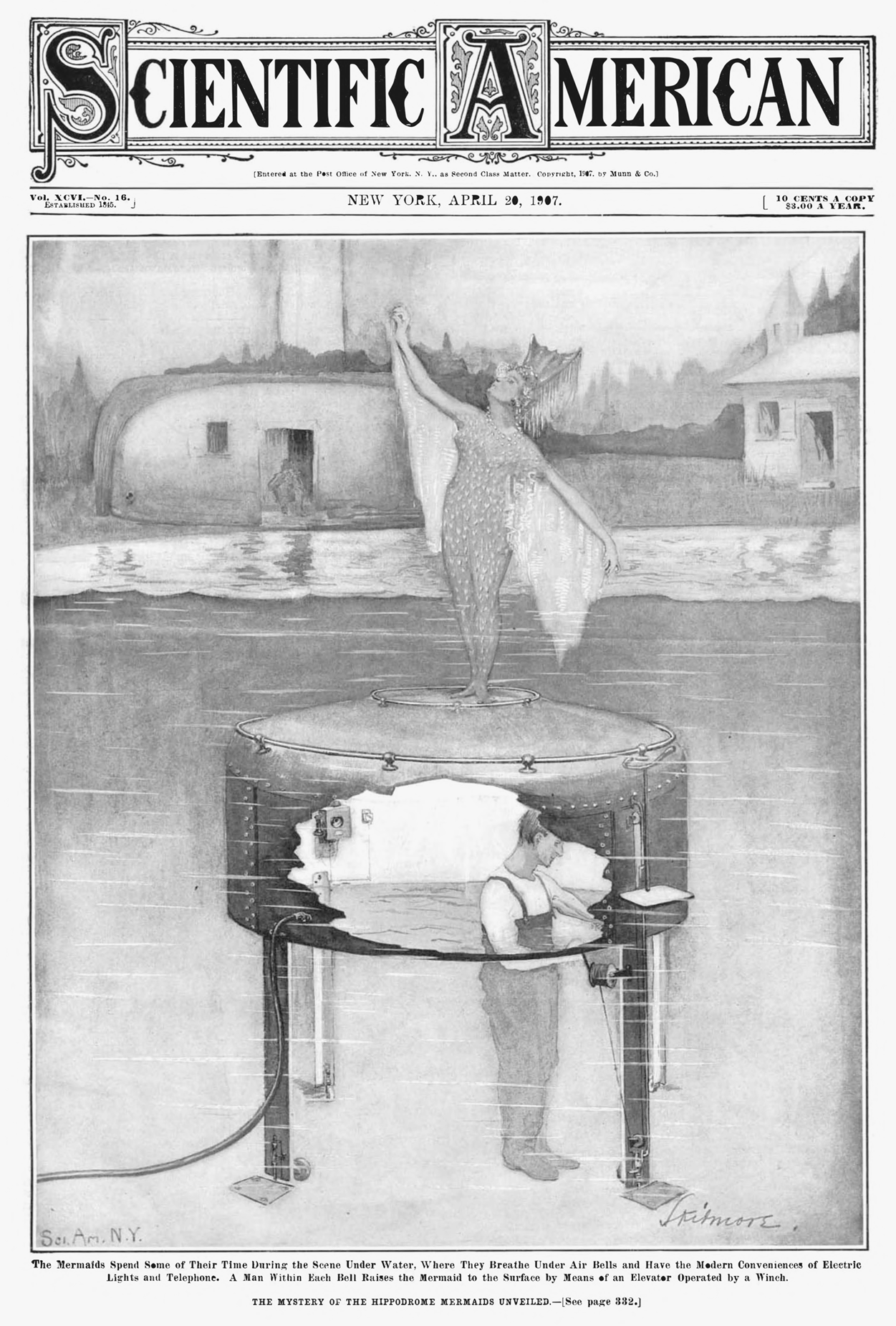

Early Hippodrome shows tended to emphasize female athleticism in the circus acts, giving audiences the chance to evaluate the virtuosity of female acrobats and lion tamers.Footnote 35 In Neptune's Daughter, by contrast, the most discussed part of the water act took place when the mermaids couldn't be seen. They could hide within the stage apron's built-in water tank because of the invention of Harry L. Bowdoin, also credited with the story scenario.Footnote 36 At the first curtain, stagehands bolted diving bells to the floor of the front apron, which was then lowered into the rapidly filling tank. As seen in Figure 2, the individual bells were wide metal drums with the underside open and four legs attached. As water rose inside the tank, the air pressure inside the chamber, along with piped-in compressed air, kept the inside from filling fully. Chorus members dressed in mermaid costumes with rubberized tights entered the bells, as did the handlers who oversaw each performer's safety. The aquatic performers stayed in these submerged bells for more than fifteen minutes before receiving their cues to appear.Footnote 37

Figure 2. Cover illustration from Scientific American 96.16 (20 April 1907) showing the diving bell technology used in the New York Hippodrome show Neptune's Daughter.

There were other diving bells used in the scene: one for a live performing dog, pulled out of the water on a fishing line by the clown Marceline; and another that was more like an upside-down canoe, which supplied air to the performers playing Neptune and attendants on his barge, which was pulled out of the water by a winch hidden in one of the fishing village cottages. The emergence and disappearance of Neptune's barge was clearly more complex, and early publicity from the Shuberts emphasized both. After the dress rehearsal for Neptune's Daughter, Lee Shubert is quoted in the New York Tribune as saying: “When King Neptune goes down in the sea in his barge, he and the mermaids disappear into the water and do not rise again.”Footnote 38 But it was the mermaids who inspired the most coverage.

The mermaids’ effortless navigation of the Hippodrome tank may in fact have undercut the effectiveness of the spectacle. A New York Times story called “How the Stage Mermaids Can Live Underwater” explains the diving bell mechanism and the performers’ use of it in extensive detail, ending with this justification: “Though this may all seem mechanical in the narration, it is only just to the managers to add that the illusion is perfect. The visual mystery is absolute—so absolute that most people have jumped to the conclusion that the water was a mirage and the whole thing contrived with mirrors.”Footnote 39 The illusion is remarkable only when the audience knows that it is grounded in truth. Coverage of the Neptune's Daughter diving bells, then, must find a middle ground where the illusion can be maintained while audience members watch it take place but explained in a way that emphasizes the risks being taken. Unlike the later iterations that emphasize the mermaids’ absence, however, the first version of this act calls attention to the mermaids’ presence and safety offstage.

An early program for Neptune's Daughter takes an approach that seems striking in our “no spoilers” age: it asks the audience to prepare themselves for the sight of the mermaids’ emergence and disappearance. Scene 2 of the show takes place in the same location as scene 1 but eighteen years later. Before introducing the new characters in this act, the program text makes an oddly long request of its readers:

The attention of the audience is called to the extraordinary water effects, invented by H. L. Bowdoin, introduced in this scene, when the singers make their entrance and their exit through the great water tank of the Hippodrome. This feat is something never before attempted in the history of the world. It is absolutely marvelous. Messrs. Shubert & Anderson announce that the effect is fully protected by patents, and could never be reproduced anywhere else in the world, even if it were possible to find a stage and water tank the size of the Hippodrome.

Spectators are advised that the feat of entering and leaving the stage by means of the water tank is absolutely safe, and that no apprehension whatever need be felt that any one disappearing in the tank is in danger.Footnote 40

They are asked to notice, marvel at, and manage their response to a technology that cannot in fact be seen. Instead of assuming that the entrance or exit is an illusion, audience members are assured that it is novel, patented, and uniquely available at this theatre. The program calls attention to this effect without explaining how it worked.

This movement between revelation and concealment highlights the middle ground staked out by the New York Hippodrome's aquatic performances, where the theatre makers wish to confirm the trick's reality without revealing so much about its mechanics that it could be replicated elsewhere. The cover of the Scientific American from 20 April 1907 (see Fig. 2) demonstrates this dual process. A mermaid performer stands atop the diving bell in her spangled wetsuit and headdress, with arms extended and head tilted to show off the fringed embellishments on both. Beneath the water, which comes to her knees, we see the diving bell on which she stands. A cutaway reveals the inside of the diving bell, including the light that signals the mermaid performer's cues, the tube that pumps in fresh air, and the overall-clad working man who helps her emerge and descend. Aestheticized femininity appears on the surface, supported and undergirded by masculinized technology embodied by the man in the submarine bell.

The article describes the function of the diving bell in even more detail than earlier articles in the New York Times had done, and for the first time it also includes extensive descriptions and diagrams explaining the functioning of Neptune's barge. But it is the caption for the cover illustration that interests me most: “The Mermaids Spend Some of Their Time During the Scene Under Water, Where They Breathe Under Air Bells and Have the Modern Conveniences of Electric Lights and Telephone. A Man Within Each Bell Raises the Mermaid to the Surface by Means of an Elevator Operated by a Winch.”Footnote 41 This engages in a kind of logic seen repeatedly in descriptions of the diving bell, where the mermaid performer is imagined as a kind of modern apartment-dwelling woman. If we follow this analogy through, then, the theatre technician working with her below the surface becomes a kind of doorman and elevator operator.Footnote 42 New York Times coverage of the show even called the space in the diving bell a “mermaid apartment” and imagined the performers inside killing time until their cues, perhaps powdering their noses with a “submarine powder-puff.”Footnote 43 The diving bells are thus figured as domestic spaces of modern urban femininity. The clown Marceline plays up this association in the show: though one of his fishing attempts pulled a dog from the water, another attempt reels in women's undergarments. Both the show and the press coverage teasingly associate the underwater space of the tank with young city women's private lives.

Publicity stunts throughout the run of Neptune's Daughter drew upon the idea of the diving bell as domestic space in comical ways. Early in the show's tenure, the mermaids reportedly ate turkey dinners while awaiting their cue within them; they had been paid for by Joseph Rhinock, a visiting congressman from Kentucky who was also a financial backer of the Shubert Organization. The mermaids displayed their empty plates to Rhinock when the show ended, according to a New York Times headline, “To Prove They Were Safe.”Footnote 44 Once the show closed, the press agent managed to wring a bit more publicity from the space with a wedding beneath a diving bell, with the actors who played Sirene and Neptune serving as witnesses.Footnote 45 Even if typical audience members couldn't see (or see into) a diving bell, they were reassured that the space was a safe one where everyday life could continue. While the ability to swim made young women seem more than human, stories like these reassured the readers that they retained their femininity.

The women who performed in Neptune's Daughter briefly became celebrities in theatrical circles. At first, only Margaret Townsend, who played Sirene, the Queen of the Mermaids, received credit in the program. In later programs all eight mermaids were named, and the popular press did its best to make them as famous as the Floradora Sextette had been six years before.Footnote 46 As the Hippodrome spectacles developed through the 1910s and into the 1920s, though, the space of the diving bell took on a different resonance. Reporters no longer wrote stories emphasizing the mermaids’ safety or their free time waiting for a cue. Subsequent Hippodrome spectacles highlighted the act of disappearing into the tank at a grander scale. The number of mermaids in the chorus grew, and their names once again fell out of the program. Cultural attitudes toward young white women in New York City shifted in the late 1900s and into the 1910s, with a growing emphasis on their collective movement as protesters and on the dangers facing them in the city at large.

The Aquatic Mass Ornament

Hippodrome shows staged other forms of spectacle in the 1907–8 and 1908–9 seasons, including car crashes and airship battles. Not until September 1909 did expressly aquatic performers return to the tank, this time as a part of the final show on the bill called Inside the Earth.Footnote 47 In the lead-up to the spectacular scene, the ruler of a subterranean city has his minions kidnap a female character from an aboveground mining camp. From his palace at the center of the earth, the king sends his guards to fetch his potential queen: “a silver-clad army of men and women serenely descended a flight of steps, submerging themselves, row after row, in the depths of the underground lake.”Footnote 48 In order to achieve this effect, set designer Arthur Voegtlin lengthened the diving bells of Neptune's Daughter so that, as each row reached the bottom of the stairs, they came up with their heads under a long inverted trough. Once submerged, that group would move in unison to one side or the other to make room for the next row of performers.Footnote 49 Instead of emerging from and returning into individual underwater spaces, these performers moved as a military unit, remaining in the collective diving bell until the scene ended.

The martial imagery of the “water guards” aligned with a move toward militarism and nationalism in popular performances of this era. It was in the same theatrical season that the Ziegfeld Follies featured a “review of the United States fleet” where the chorus girls wore battleship headdresses.Footnote 50 Margaret Werry discusses the 1909 Hippodrome season as one that marks the development of what she calls “the American Pacific,” a fantastic staging of imperial desires and ambitions that “linked the domestic production of consumer desire for an imagined Orient in the United States, with the all-too-real political, military, and commercial pursuit of an American presence in the actual East.”Footnote 51 Inside the Earth shows how these desires are mediated through the Hippodrome chorus. According to a New York Times review, the second scene takes place outside a ferry-house, where “a clever negro song and dance is introduced, in which so many chorus girls take part that it is impossible to count them, all apparently blacked up”; the reviewer archly notes, “It was heartrending to feel that they would be compelled to get their faces clean in time to be Japanese ladies in the ensuing scene, but suddenly they transform themselves in plain view into perfectly white sailor boys.”Footnote 52 Whether this stagecraft took place through lighting, quick changes of costume, or additional makeup, it communicated effectively to the audience. The white chorus girl is a screen for audience desires, one that seems able to transform with ease from blackface to “perfect” whiteness and then to what Esther Kim Lee terms “cosmetic yellowface” for the geisha girl number.Footnote 53 Their collective racial mimicry is visible and vital to the pageantry of the show.

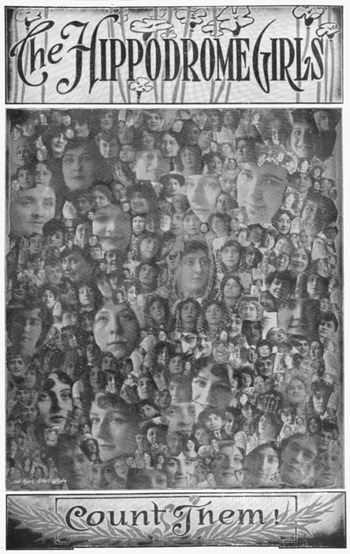

Unlike the individualized mermaids of Neptune's Daughter, this group is most notable because of its size. The souvenir program for the 1909–10 season that includes A Trip to Japan and Inside the Earth features an illustration meant to overwhelm the reader (Fig. 3).Footnote 54 Taking up most of the page, we see a collage of Hippodrome chorus girls’ faces ranging in size from the tip of a pinkie to larger than a quarter. They are cut from promotional pictures for Hippodrome shows of the past: the Neptune's Daughter mermaids are visible at the center of the page, one large image surrounded encircled by smaller ones wearing the same beaded headdress. For the most part, though, the faces are shorn of their context, roughly overlapping one another so only their eyes, nose, mouth, and occasionally their hair, can be seen. The header for the image reads “The Hippodrome Girls”; the footer reads, “Count Them!” This seems like an unachievable command: because of their excessive number, irregular size, and positioning within this image, the Hippodrome Girls indeed seem, per the New York Times review, “impossible to count.” They are a kind of fractal white womanhood, self-similar and reproducing the same features at every scale.

Figure 3. Page from Souvenir Book: New York Hippodrome, Season 1909–1910. (New York: Comstock & Gest, 1909), n.p. Collection of the author.

The Hippodrome spectacle thus connects the mass movement of women in nineteenth-century spectacular performance to that of the twentieth century's Tiller Girls, Rockettes, and other practitioners of precision dance. Unlike the individual mermaids in Neptune's Daughter, the water guards in Inside the Earth and the disappearing girls in Hippodrome shows to come can all be understood as examples of the “mass ornament,” Weimar era cultural theorist Siegfried Kracauer's term for the abstract pattern produced by large numbers of women's bodies moving in unison. Dance and performance studies scholars have used Kracauer's concept to discuss the forces of mechanization at work in precision dance and, more recently, in synchronized swimming.Footnote 55 Each performer becomes part of a larger spectacle that can only be understood from a distance, “performing a partial function without grasping the totality” in the same way as a worker on an assembly line.Footnote 56 The disappearing aquatic performers of the Hippodrome participate in the tradition of the mass ornament through the rational and feminized construction of their spectacle.

Though the principal performers may have had a different sense of themselves and their work, most Hippodrome performers followed a schedule like that of the factory worker. They used timecards to punch in and out; their schedule was a strenuous one with shows twice a day Monday through Saturday, plus rehearsals Monday morning.Footnote 57 At the same time, this stability could be a welcome relief compared to the touring schedule of a vaudeville performer; one article described “Hippodrome couples, whose professional duties are so regular that they savor of the tin dinner pail and factory whistle.”Footnote 58 As the aquatic performances increased in size and complexity, safety precautions multiplied: by the time they reached ninety-six disappearing mermaids, each one was assigned a number that she called off when emerging, so that stagehands could ensure that everyone made it out of the tank.Footnote 59 Whereas every mermaid in Neptune's Daughter had her own handler, later aquatic performers were responsible for confirming their safety within a Taylorized system. In both cases, their experience is far different than that of current mermaid performers studied by Tracy C. Davis and Sara Malou Strandvad. They discuss how present-day mermaids survive in the gig economy: giving swimming lessons, booking their own appearances, and otherwise carving out a space for their entrepreneurship.Footnote 60 Aquatic performers of the early twentieth century undeniably operated within a more regimented and externally regulated system.

A meeting that took place at the Hippodrome during Inside the Earth's run confirmed the cultural link between new labor practices and the presence of large groups of women in this period. The New York Hippodrome did not run its usual shows on Sundays due to laws prohibiting theatrical performance on the Christian sabbath. The theatre's owners typically rented the space on Sunday for benefit performances, concerts, and political rallies. On 5 December 1909, wealthy socialite and women's suffrage advocate Alva Vanderbilt Belmont hosted a rally supporting the striking women who worked in the city's shirtwaist factories. Speakers at the rally shared their messages of “[s]ocialism, unionism, woman suffrage, and what seemed to be something like anarchism” with a crowd made up of mostly young women.Footnote 61 In Progressive Era New York City, women's mobility was inextricably bound up with the challenge to the political establishment.

Notably, the water guards of Inside the Earth were at first a mixed-gender group. (The coverage in Theatre Magazine that reveals the setup for this act was written by a male writer who took the place of a Hippodrome employee.) Stage manager R. H. Burnside said that the men cast in this show generally had an easy time performing the trick but that the women were a harder sell; the chorus girls were sold on the act only in summertime, when they could rehearse in the tank and save a trip to Coney Island.Footnote 62 As aquatic performance at the Hippodrome progressed, though, it became increasingly populated by women. This follows a trend identified by scholars of later aquatic performance. Jennifer Kokai notes that the earliest shows at Weeki Wachee Springs in Florida included male and female performers; “men were phased out,” she writes, when the founder, Newton Perry, realized that a homogenously female cast made for a more uniform and appealing spectacle.Footnote 63 The Hippodrome's aquatic performances became increasingly feminized both onstage and in the minds of audience members. Later shows produced by Charles Dillingham supplemented the disappearing mermaids with women high divers.Footnote 64 At least one of those divers, Helen Carr, lost sight in both of her eyes from the impact of the water when she dove from a 122-foot platform.Footnote 65

Unlike the women in Neptune's Daughter before them or those in the aquatic spectacles to come, the mass groups of Hippodrome mermaids did not put on a pretty face as they marched into the tank; they wore serious expressions and descended to solemn music. One account of Around the World (1911) describes mermaids who squared their jaws and took one last breath before going under.Footnote 66 This is no longer the performance of ease and effortlessness that we saw with the first Hippodrome mermaids. Instead, as I discuss in the following section, it is an acknowledgment and an embodiment of the risks associated with women's mobility. Indeed, we might understand the performers’ expressions and physicality as ways of communicating their individual responses to the spectacle in which they participate. Like the visible pleasure Esther Williams takes in her own swimming body, the grim resolve of the Hippodrome mermaids belongs both to their characters and to themselves.Footnote 67 These expressions reminded audience members that the mermaids undertook a dangerous task to create such a spectacular finale. They also remind scholars like me that even the most prosaic form of aquatic performance—walking down steps—might have more in common with the daredevil feats of the high diver than it does with the synchronized movements of the Tiller Girl. Their expressions, whether real or put on, called attention to the risk they took. The risk exceeds acting. The water guards differ from ballet girls or supernumeraries before them, or Rockettes and other precision dance groups after, because their movement across the stage calls attention not merely to their fanciful appearance or to their construction of the abstract spectacle seen only from the audience's point of view, but to the way that spectacle is insistently destroyed.

The Girls That Disappear

The sheer number of performers who disappeared became a central part the Hippodrome spectacle. Where Inside the Earth sent a dozen men and a dozen women down the steps, the 1913 spectacle America did the same with “Forty-eight girls in pink and white.”Footnote 68 Press agent Murdock Pemberton reports that, at its height, ninety-six women performed the act together. This followed the general schema of the Hippodrome in the late 1910s and early 1920s. Pemberton reminisced in the 1930s that Charles Dillingham–produced shows were built on a particular formula: take the numbers of singers, dancers, show-stopping settings, and so on in “the contemporary musical revue” and multiply each by six.Footnote 69

The sight of young women marching, row after row, into the water would have evoked several associations for audiences in the late 1900s and the 1910s: strikers or protesters for women's suffrage, workers clocking in for their shift at a factory, and the masses of women arriving from the hinterlands or from abroad, who risked losing contact with their families or losing their virtue in the process of acclimating to city life. This was an age of moral panic about young women's mobility within urban space, with a particularly acute awareness of the risks that they would be trafficked into forced prostitution, or as reformers called it then, “white slavery.”Footnote 70 Nominally meant to distinguish this threat from that of wage slavery or chattel slavery, this racist term emphasized the moral purity of white women and racialized their captors.Footnote 71 It was closely aligned with Progressive Era anti-Asian and anti-Black sentiment, as well as perceived threats to the vitality of white America.

The attempt to shut down networks of commercialized prostitution in the early twentieth-century American city led to the formation of several vice commissions, the publication of reports on their findings, and at least one law passed by Congress, the Mann Act.Footnote 72 These reforms are more commonly examined in relation to another genre of theatre, the red-light drama or brothel play. As Katie N. Johnson discusses in Sisters in Sin, sex work dominated the 1913–14 Broadway season: four plays dealt with the topic, and two of them—The Lure and The Fight—were closed and put on trial for obscenity.Footnote 73 But Hippodrome spectacles and brothel plays were part of the same theatrical landscape. George Bernard Shaw's Mrs. Warren's Profession ran at New York's Garrick Theatre for a single performance on 23 October 1905—six months after the New York Hippodrome opened.Footnote 74 Moreover, the discourse surrounding this moral panic often poeticizes the plight of these women in ways that the Hippodrome mermaids act specifically evokes. The former New York City police commissioner Theo A. Bingham published a book in 1911 called The Girl That Disappears: The Real Facts about the White Slave Traffic. In another title from that year, two chapters with different authors both use the metaphor of innocent girls sinking or being engulfed in a sea of immorality.Footnote 75 The image of rows of women sinking into the water may have been so evocative because it made staged one of the most prevalent anxieties of the time in a literal way.

The most common descriptions of the disappearing mermaids act relate its finale in a tone of morbid fascination, suggesting the ambivalence with which audience members consumed the images of feminine risk within urban space. A woman who saw the act when she was a child recounts her experience: “We saw mermaids being chased by sailors, we saw them disappear into the water—a few bubbles, and that was all. No one floated up to the surface. The mermaids wore a good deal and the sailors possibly had weights in their pockets which may have accounted for their bodies’ remaining at the bottom of the Tank. But it gave a ghoulish zest to the end of the show to think how many lives were being sacrificed.”Footnote 76 Unlike both earlier and later discussions of women's aquatic performance, which emphasize how comfortable and “at home” the performers feel in the water, this trope instead imagines the water as a site of recurrent fatality. Indeed, the trope was so well-established that Alexander Woollcott could write in his review of Happy Days (1919):

It is always entertaining to see fifty or more of the Hippodrome's amphibious chorus girls march nonchalantly into the water and disappear forever beneath the unrippled surface of the lake. Not quite forever, to be sure, because just when the suspicion lays hold on you that the prodigal Mr. Dillingham, in his lavish way, must drown a new set each night, for the diversion of his gratified patrons they reappear, damp but dauntless, in time for the grand finale.Footnote 77

Woollcott slyly suggests, as Kracauer does of the Tiller Girls’ performances, that the mermaids’ disappearance is “an end in itself,” a theatrical demonstration of the Hippodrome's commitment to the production of excess that Dillingham lavishly upholds through the murder of his chorus.Footnote 78 The mermaids’ return for the finale confirms that all is well, that even though the show might be excessive it also ensures the safety of its performers. The destruction of the mass ornament occurs, but so does its restoration. The audience's attitude toward them, though, is markedly different from the one Kracauer imagines toward the Tiller Girls and their ilk. Whereas audiences for the persistent mass ornament can think about them as component parts that can be reconstituted into different shapes, audiences for the disappearing mass ornament must reckon with the potential of loss—the loss of a constituent part, and the loss of their authority to perceive the whole image.

In Better Times (1922), eighty mermaids marched into the deep and then reappeared on a vessel emerging from the water for the final scene, posing as star Nanette Flack sang “My Golden Dream Ship.”Footnote 79 This was their last appearance. Charles Dillingham left his role as producer in 1923. Vaudeville impresario E. F. Albee leased and remodeled the theatre,Footnote 80 adding more seats and a more conventional stage for variety performance and film. The stage apron before the proscenium arch, and the tank beneath it, were torn out.Footnote 81 When writing about the spectacle years later, though, nostalgic Hippodrome-goers inevitably remember not the triumphant reappearance of the mermaids in the finale but their initial disappearing act. A 2008 article in the Theatre Historical Society journal Marquee includes this reminiscence: “This writer remembers as a young boy attending the last of the great Dillingham and Burnside shows in 1922, Better Times. Among the wonders recalled were those Hippodrome diving girls who disappeared down the stairs in groups of six or eight and into the water, never to return.”Footnote 82 As time goes on, the Hippodrome mermaids do not produce the same kind of mass ornament as the Tiller Girls of Kracauer's essay: the spectacle that they produce is not the abstract shape of their bodies in unison seen from above; instead, it is the absence they produce that persists in the mind of spectators.

The mermaids, perpetually disappearing in the memory of audiences, functioned as a metonym for the venue where they performed. These disappearing mermaids became emblematic of nostalgia for the Hippodrome and for the city it represented. Here it is useful to remember Peggy Phelan's discussion of disappearance as a key element that connects performance to the desires of the watching audience: “The disappearance of the object is fundamental to performance; it rehearses and repeats the disappearance of the subject who longs always to be remembered.”Footnote 83 New Yorkers may have embraced the perpetual newness of their city, but they held onto memories of the places and performances that linked them to the past. Indeed, contemporary author Colson Whitehead suggests that these memories make someone into a New Yorker: “You are a New Yorker,” he writes, “when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now.”Footnote 84 Where the Hippodrome mermaids in their own time embodied public anxieties about women moving through the city, they become internalized as ghostly representatives of what the city has lost.

Nostalgia and Filiation

In February 1939, producer Billy Rose held auditions at the Hippodrome; he offered a promised “500 jobs,” most in the cast of his World's Fair Aquacade.Footnote 85 Joined by producer John Murray Anderson and star swimmer Eleanor Holm, Rose saw thousands of prospective chorus girls. Indeed, so many people showed up looking for nonswimming roles that they had to ask the swimmers and divers to return for an audition the following week. Candidates were told to bring a bathing suit, although the Hippodrome tank was no longer available to test their swimming skills.Footnote 86 The New York World's Fair opened on 30 April 1939. The Hippodrome hosted a mix of religious services, rallies, concerts, and sporting events that spring and summer, but it closed for good on 16 August 1939.

The year 1939 was an inflection point in the development of aquatic performance. The move from the Hippodrome to the Aquacade marked a larger change in American expectations about “how water performs.”Footnote 87 Whereas earlier in the twentieth century audiences were thrilled by the onstage water of vaudeville tank acts and Hippodrome extravaganzas, this was an era where they turned their attention back to the outdoor aquatic spectacle. Popular performance styles that brought water onto interior stages had been superseded by new modes of performance on film and radio. In addition, the paradigm of “modern water” discussed by Timothy Scott-Bottoms seems to have shifted.Footnote 88 The Hippodrome contained and abstracted water within its tank, an enclosed space within an enclosed theatre. The Aquacade stadium, by contrast, was an open-air theatre that presented a “domesticated” landscape.Footnote 89 The types of performance that arise later in the century have more to do with the touristic outdoor space of the Aquacade than they do to the controlled onstage water of earlier performances.

Attitudes toward the women swimming through these scenes changed as well. In the 1920s and 1930s, recreational sports had become a more important part of physical education for women.Footnote 90 Gertrude Ederle swam the English Channel. American women flourished as swimmers at the Olympic Games, first Ederle in 1924 and then Eleanor Holm in 1928 and 1932. Instead of imagining them as otherworldly creatures or women engaged in risky activities, audiences had a more developed framework for appreciating the athleticism of these female performers—though they did still want to see it demonstrated in a conventionally feminine way.

New Yorkers at the time recognized a family resemblance between the Aquacade swimmers and the previous generation of aquatic performers. Two months after the Aquacade opened in Queens, a piece of comic verse by newspaper columnist H. I. Phillips was nationally syndicated. Titled “Only a Hippodrome Mother,” its first chorus read:

The Hippodrome “mother” in this piece reminisces about her days performing as a mermaid, engaging in some of the same nostalgia as the audience members previously discussed. At the same time, though, she acknowledges the trials she went through in maintaining her youthful appearance—including diets, facials, and lying about her age—even after her performing days were done. “I felt I was still youthful,” the voice proclaims, “but / It's all so different now.”Footnote 92 I find this one-off column fascinating because it asks us to think about what happens to the seemingly endless assembly line of interchangeable dancers once they're replaced by newer models. Performers, producers, and scholars alike can attend to the body that is not onstage, the aging female body, and the passage of time.

If the Hippodrome mermaid is mother to the Aquacade swimmer, then glamorous synchronized swimming is imagined as a matrilineal form of women's popular performance. The logic of filiation can be a dangerous one, though, since the passing of the torch from mother to daughter also centers whiteness. Aquatic performance in the postwar era, epitomized by the cinematic aqua-ballets of Esther Williams, do the same kind of work, with Williams as the “all-American girl” backed by a circling chorus of white women swimmers. There are contemporary performers pointing this out and pushing back against it—here, I'm particularly thinking about Beyoncé using synchronized swimming iconography in the Lemonade visual album,Footnote 93 and more recently in the musical film Black Is King. Synchronized swimming troupe The Aqualilies, whose routines spoof the campy homogeneity of the Esther Williams–style routine, collaborated with the singer to produce a routine where most of the swimmers are women of color; the Esther Williams spot—radiant, at the center of the spectacle—is occupied by Beyoncé herself.Footnote 94

Women's aquatic performance is constituted through the play of presence and absence. When synchronized swimming hides its work beneath the water, scholars of theatre and performance can surface it and make it more visible. The stories of the Hippodrome mermaids help us refocus scholarly attention on the work behind the spectacle, the feet kicking beneath the surface of the pool at the Aquacade, the unseen labor that goes into swimming pretty. Yet as much as I am inclined to reveal the previously concealed, I also hope that we can meditate on the absences evoked by performance without filling in the narrative gaps. The Hippodrome program asked of the disappearing diving girls, “Where do they go?” Audience members regularly echoed the question back to Hippodrome performers and those behind the scenes. The ones who knew how the trick worked shared an agreed-upon response suggested by the artistic director R. H. Burnside: when the girls disappeared, they went across the street to Jack's restaurant for a meal.Footnote 95 The joking deflection grounded the Hippodrome's fantasy world within the logic of urban space and showed how comfortable these female performers were when moving between the two. What seemed like a matter of life and death to the audience's eyes was merely a shift at work to the participants: physically taxing, even dangerous, but an everyday part of life in the city. Instead of making the unseen part of the act seem either domestic or dangerous, this joke opens a space for thinking about these women performers’ agency in the city outside of the framework of performing their own peril. They move off the stage where they perform a highly racialized visibility, passing into a space of anonymous sociability that is out of sight and off the clock.

Sunny Stalter-Pace is Hargis Professor of American Literature at Auburn University. She specializes in the interdisciplinary study of modernism, popular performance, and urban space. Her current book project is a group biography called Backstage at the Hippodrome: The Show People behind New York City's Most Spectacular Playhouse. She published Imitation Artist: Gertrude Hoffmann's Life in Vaudeville and Dance with Northwestern University Press in 2020. Her website is www.sunnystalterpace.com.