With the emergence of the Atlantic slave trade, plantation slavery shaped the development of slave societies in the Americas. Yet, as all the articles in this Special Issue have demonstrated, slavery was also present in many urban settings of societies where bondage was central or existed in the three continents involved in the inhuman commerce. Especially during the so-called age of abolition, a period covering more than one century (c.1770s–c.1880s), urban slavery continued to be prominent. Cities were spaces where enslaved and freed people joined rebellions, formed fugitive communities, and petitioned the courts to obtain their freedom. In the age of abolition, enslaved, freed, and free black urban populations also participated in campaigns to pass legislation to end slavery. However, in 1888, when slavery was eventually abolished in all societies of the Americas, cities continued to be the site of racial and social inequalities. Although offering opportunities of social mobility for the descendants of enslaved men and women, cities remained the privileged space where black social actors persisted in fighting against racism.

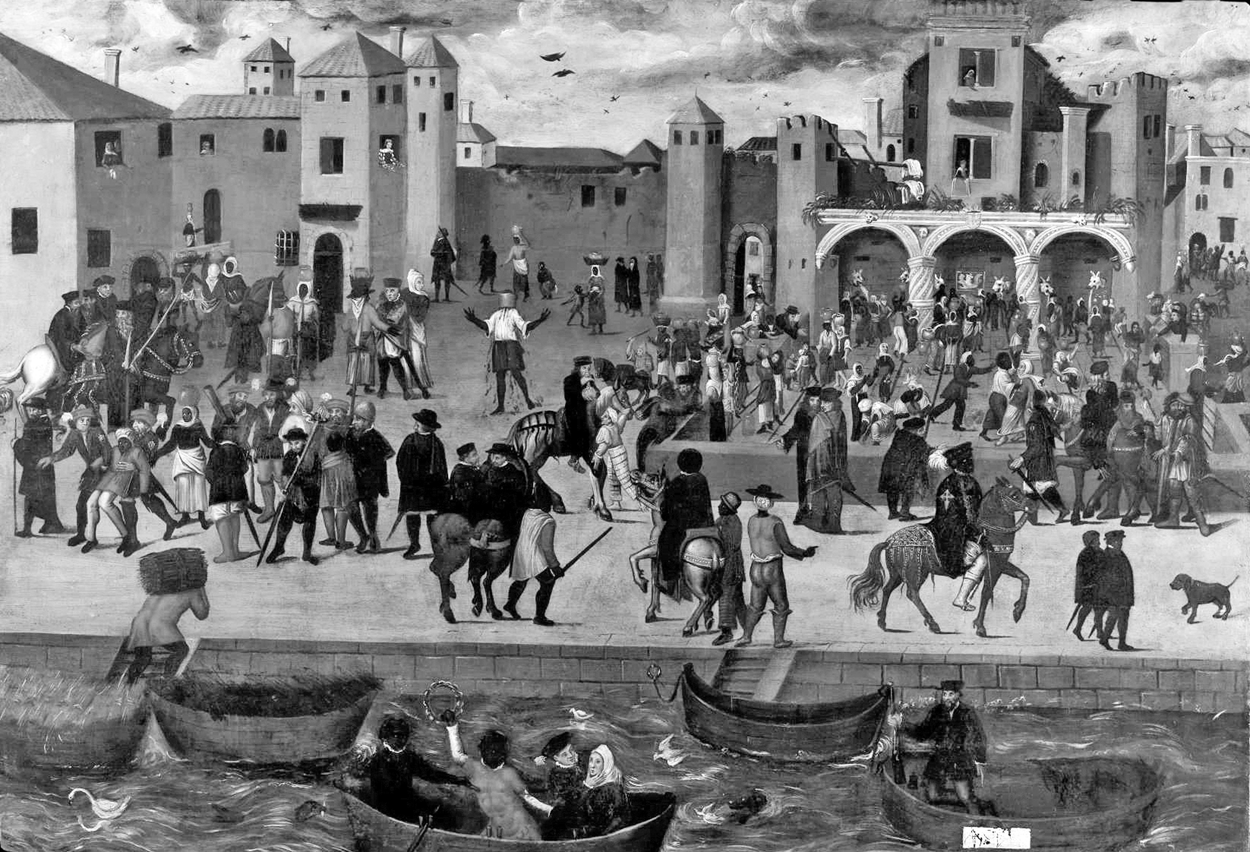

As early as in the sixteenth century, European artists painted people of African descent performing all kinds of activities near the Chafariz-del-Rey in Lisbon (Figure 1). Many contemporary observers, including European travelers, extensively commented on the strong presence of enslaved, freed, and free black men and women in the cities of Latin America and the Caribbean. Several of these travelers, like the French artists Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768–1848), Édouard Manet (1848–1883), and later François-Auguste Biard (1799–1882), who visited Brazil in the second half of the nineteenth century, were often surprised that when walking the streets of Rio de Janeiro and Salvador they rarely saw any white individuals, but could only identify black women, especially street vendors (Figure 2).Footnote 1 Despite the racist views of their authors, European travelogues provide a wealth of information on urban slavery in the Americas. Through texts and images, these travelers described how slavery shaped the urban landscapes, with its places of physical violence and suffering such as whipping posts and slave markets and its refuge spaces such as the churches housing Catholic black brotherhoods.

Figure 1. Chafariz d'el Rei, c.1560–1580, anonymous Flemish painting, oil on wood, 93 × 163 cm, Berardo Collection, Lisbon, Portugal. Source info: © Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. “Les rafraîchissements de l'après dîner sur la place du palais” [After-dinner refreshments in the Palace Square]. Jean-Baptiste Debret, Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil (Paris, 1834–1839), plate 9. Source info: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Available at: http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-7978-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99; last accessed: 29 December 2019.

As historian Rashauna Johnson explains, in port cities like New Orleans, enslaved persons “were commodities in the flesh trade, laborers who produced addictive staple crops, consumers who purchased local and imported goods, vendors who peddled products to multilingual customers, and modes of transport to buyer and sellers”.Footnote 2 In port and inland cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Sabará, Baltimore, Bridgetown, New York City, Lima, Puebla, Cartagena, Quito, as well as Lisbon, Seville, Luanda, and Benguela, enslaved men had a variety of professions: they were coachmen; porters; barbers; gardeners; shoemakers; surgeons; healers; carpenters; tailors; craftsmen; blacksmiths; hatters; and silversmiths, whereas enslaved women could work in convents and shops and were also street vendors, prostitutes, nannies, wet nurses, cooks, washerwomen, and domestic servants.Footnote 3

Urban areas were places of struggle and resistance, where bondsmen and bondswomen wandered, gossiped, and hid. Along the network of dark and stinking streets, in several cities of the American continent bondspeople plotted conspiracies and rebellions. Led and supported by enslaved, freed, and freeborn black individuals, the Denmark Vesey's conspiracy in 1822 and the Malê rebellion in 1835, respectively, emerged in the urban settings of Charleston, South Carolina and Salvador, Bahia. The streets of Philadelphia and Baltimore also offered enslaved people the ideal context to run away from bondage.Footnote 4 Yet, during the decades that preceded the beginning of the Civil War, cities also provided opportunities to professional gangs of kidnappers to abduct free black men, women, and children and sell them into slavery in the United States South.Footnote 5 Still, cities were sites where enslaved people preserved, adapted, and recreated African cultures, by preparing food and prescribing remedies whose recipes they had brought from the African continent. For enslaved people and their descendants, the urban fabric was also the stage for drumming, dancing, singing, reveling, and participating in religious and pagan festivals. Afro-Brazilian martial arts, dance, and music such as capoeira and samba emerged during slavery in Brazilian cities like Salvador and Rio de Janeiro. Bondspeople also paraded in religious processions and celebrated carnivals in the streets of Havana, New Orleans, Nassau, and Kingston.

The rise of gradual abolition in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century progressively provoked the disappearance of tangible traits of urban bondage. The streets and buildings where slavery bloomed were transformed by several layers of works intended to sanitize and modernize the cities. Black populations were not welcome in this process. Still, many towns of the Atlantic world preserved entertainments, music festivals, and dance traditions that emerged with the development of slavery and the growth of black populations in urban areas. Over the twentieth century and during the two first decades of the twenty-first century, black men, women, and children who have been historically identified as descendants of enslaved people have continued to struggle to occupy the public spaces of cities built with slave labor. Maintaining this presence has always been a difficult challenge. The state and its institutions, such as the courts of justice and the police, have criminalized black people's participation in carnivals, samba parties, capoeira circles, and African-based religious ceremonies. Many decades after its end, the violence of slavery still marks many cities in the Americas. In 2019, attending a funk ball in one of Rio de Janeiro's favelas can be the equivalent of a death sentence. Likewise, in the United States, because they were black, men and women have been profiled, targeted, and killed by police officers in Charleston, Ferguson, New York City, Cleveland, Baltimore, and many other cities.

The ghosts of slavery continue to haunt former slave ports and cities where slavery once existed. Slave wharfs, cemeteries, and markets were among the central tangible sites associated with slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. Although their traces have survived, in many cities of the Atlantic world they also remain unnoticed in the public space. The slave markets of Salvador and Rio de Janeiro attracted the attention of European travelers who visited Brazil. Amédée François Frézier, a Savoyard military man who had traveled to Chile, Peru, and Brazil between 1712 and 1714, describes Salvador's slave market in his travelogue: “There are shops full of these poor unfortunates that are exposed all naked, and they bought them like animals and acquire upon them the same power, so that on minor discontent, they can kill them almost with impunity, or at least mistreat them as cruelly as they want”.Footnote 6 Likewise, British traveler Thomas Lindley, who sojourned in Bahia in 1802, also provides a description of a slave market in Salvador: “The streets and squares of the city are thronged with groups of human beings, exposed for sale at the doors of the different merchants to whom they belong; five slave ships having arrived within the last three days”.Footnote 7 British traveler Maria Graham who visited the port area of Salvador's Lower City described it as being the place where the slave market was located: “passing the arsenal gate, we went along the low street, and found it widen considerably at three quarters of a mile beyond: there are the markets, which seem to be admirably supplied, especially with fish. There also is the slave market, a sight I have not yet learned to see without shame and indignation”.Footnote 8 But despite these accounts, to this day no markers indicate where these sites were located. This absence has led city residents to develop accounts according to which the basement of the present-day central market, known as Mercado Modelo, was a former slave market.Footnote 9 Residents report that they can hear the laments of enslaved persons who were held in the basement during the night. Stories of ghosts of enslaved men and women are also widespread in cities such as New Orleans, where ghost tours disseminate similar narratives.Footnote 10 These stories, expressing how the collective and public memory of slavery has been repressed in former slave societies, show how social actors continuously respond to the lack of initiatives publicly recognizing sites of slavery. By relying on existing images and recollections, narratives of slave ghosts allow black citizens to imagine where slave markets were located and what the experience of confinement was like for enslaved individuals in these slave depots.

Despite the long-lasting invisibility of slavery in the public space of former slave societies and societies where slavery existed, there are signs that this context is changing. After creating a Slave Trail Commission in 1998, the city of Richmond, capital of Virginia, in the United States, conceived a self-guided walking trail highlighting the city's sites associated with slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. In 2011, Richmond eventually unveiled seventeen markers along the trail. Likewise, the Williams Research Center (The Historic New Orleans Collection) inaugurated the exhibition Purchased Lives: The American Slave Trade from 1808 to 1865 in 2015. The traveling exhibition portrays the importance of New Orleans as the largest market for the domestic slave trade in the United States. In 2018, the New Orleans Committee to Erect Markers on the Slave Trade dedicated a plaque at the intersection of Esplanade Avenue and Charles Street marking the site where “the New Orleans offices, showrooms, and slave pens of over a dozen of slave trading firms” were located. In 2015, New York City also unveiled a modest plaque marking the New York's Municipal Slave Market situated where Wall Street meets the East River.

For more than three decades, a variety of black social actors have put pressure on municipal authorities and politicians to make slavery visible in urban spaces. Activists and other citizens have also protested the presence of monuments honoring slave traders and pro-slavery individuals. In European cities such as Liverpool and Bordeaux, activists of African descent demanded the municipalities rename the streets named after individuals involved in the Atlantic slave trade. As recently as in 2018, a monument honoring the slave trader Antonio Lopez y Lopez was removed from downtown Barcelona.Footnote 11 Every December, concerned citizens continue to organize demonstrations in various cities of the Netherlands to protest the notorious Black Pete, a racist depiction of a black helper of Saint Nicholas or Sinterklaas (Santa Claus) associated with the country's long history of involvement in the Atlantic slave trade and colonialism. Similarly, in numerous cities of the United States, citizens have protested the presence of Confederate monuments and flags and demanded their removal, especially after June 2015, when a white domestic terrorist killed nine African American parishioners in Charleston.

In addition to these intentional actions, sometimes the history of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade literally emerges from the ground. In the last twenty-five years, cities in Europe and the Americas have uncovered various burial grounds where enslaved people were interred. In 1991, hundreds of human remains were discovered during an excavation to construct a new federal building at 290 Broadway, in New York City. A team of scholars concluded that the site was a former burial ground containing the remains of about 15,000 enslaved and free black individuals (African or of African descent) buried during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The site became known as the New York African Burial Ground, to this day the largest of its kind in the United States. The uncovering of the burial ground emphasized the importance of slavery in New York City and led to the dedication of a memorial in October 2007.Footnote 12

Unlike New York City, whose past associated with slavery has been a forgotten chapter in the history of the United States, slavery was a central element in Rio de Janeiro's daily life until the end of the nineteenth century. Between 1758 and 1831, nearly one million enslaved Africans came ashore in the Valongo Wharf. But the site was gradually erased from the urban space after the international slave trade was banned in 1831 and during the chaotic processes of modernization and urbanization in the early twentieth century. During this period, the old port zone in Rio de Janeiro's downtown area remained nearly abandoned.Footnote 13 The city administration failed to preserve the heritage sites and buildings located in the region, and also neglected its underprivileged black residents.Footnote 14 But like what occurred in New York City in 1991, in 1996 an archaeological excavation on a private property at 36 Pedro Ernesto Street (formerly Cemitério Street) in the Gamboa neighborhood recovered a burial ground containing bone fragments of dozens of enslaved African men, women, and children. The site was identified as being the Cemitério dos Pretos Novos (Cemetery of New Blacks), a common grave where recently arrived Africans who died before being sold in the Valongo market were buried. Without official and public support, the private site remained in the hands of the Guimarães family who owned the house where the bones were uncovered and who gradually transformed the building into a nongovernmental organization. But in 2011, as Rio de Janeiro prepared to host the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games, drainage works eventually revealed the old ruins of Valongo Wharf. The excavations also recovered numerous African artifacts, therefore giving a new visibility to the slave burial ground. Although the lack of public support persists, both the Valongo Wharf (Figure 3) and the Cemetery of New Blacks (Figure 4) have been gradually incorporated into Rio de Janeiro's urban landscape that now recognizes the importance of the Atlantic slave trade and Brazil's crucial role in it. In 2012, the site of the Cemetery of New Blacks was transformed into a memorial and its main exhibition was reshaped. In 2017, UNESCO added the Valongo Wharf to its World Heritage List. The local community slowly appropriated the Valongo area, organizing black heritage tours, public religious ceremonies, and spectacles of capoeira.Footnote 15 Despite these developments, the Valongo area remains negligible compared with most other Rio de Janeiro's tourist sites, and many locals are not aware of its historical importance. Yet, its presence is a permanent reminder of the role of slavery in Rio de Janeiro, which will be hardly erased again from public view.

Figure 3. Valongo Wharf, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Photograph: Ana Lucia Araujo, 2018.

Figure 4. Façade of the Cemetery of New Blacks, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Photograph: Ana Lucia Araujo, 2018.

On the other shore of the Atlantic Ocean, despite the enduring traces of the Atlantic slave trade in its urban areas, Portugal was one of the last European countries to respond to the demands to memorialize slavery and the Atlantic slave trade. In 2009, during work to construct the Anel Verde Parking Lot in the Gafaria Valley in Lagos (a former slave port situated nearly 300 kilometers south of Lisbon), the skeletons of 158 enslaved Africans were uncovered from an urban waste dump that functioned as a “blacks’ pit”, dating back to the period between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 16 The analysis of the remains revealed corpses of men, women, and children disposed in a variety of positions, and some of them had their hands and arms tied.Footnote 17 Although the remains were extensively studied by Portuguese scholars, no memorial was established at the site. Instead, an underground parking lot now occupies the location of the waste dump, on top of which sits the Pro Putting Garden Lagos, a picturesque landscaped mini-golf course. Featuring fountains and bridges, the scenic park is decorated with colorful sculptures (Figure 5) by artist Karl Heinz Stock (who is identified as white), representing female bodies joyfully dancing over one of the oldest European sites where the remains of enslaved Africans associated with the Atlantic slave trade were discarded. But tourists are only informed about this unpleasant long chapter of Portuguese history when they visit the “slave market,” a museum center created in collaboration with the UNESCO Slave Route Project in 2016. The museum, occupying a seventeenth-century building constructed in the area where the presumed first European slave market existed, comprises a modest permanent exhibition telling the story of the Atlantic slave trade and slavery in Lagos.

Figure 5. Sculptures by Karl Heinz Stock, Pro Putting Garden, Lagos, Portugal. Photograph: Jose A., 2014, cc-by-sa-2.0, © Wikimedia Commons.

Despite Portugal's continuing refusal to face its history of slavery and its central involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, over the last decade black citizens have played an important role in making Lisbon's slave past visible in the public space. In December 2017, under the leadership of the Association of Afrodescendants (an anti-racist organization) and through the city's participatory budgeting system, Lisbon residents voted for a project to create a memorial to the victims of slavery. In June 2019, the city council sanctioned the creation of the memorial along with a visitor center and initiated the selection process of its design and implementation proposal. The memorial will be constructed at Campo das Cebolas, an area associated with the presence of enslaved Africans in Lisbon, 230 meters from the Chafariz-del-Rey (Figure 6), the same portrayed in the sixteenth-century painting (Figure 1).

Figure 6. Chafariz-del-Rey, Lisbon, Portugal. Photograph: Ana Lucia Araujo, 2019.

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, an increasing number of scholarly works started focusing on how slavery shaped the urban areas of the three continents involved in the Atlantic slave trade. As this new interest emerges, cities where slavery existed and former slave ports have gradually attempted to come to terms with their history of bondage and trading in human beings. Despite the need of more studies focusing on the various social, economic, legal, and cultural dimensions of slavery in specific cities, comparative works can contribute to better illuminate the development of bondage in urban areas and the present-day legacies of the inhuman institution. Scholars continue to uncover a multitude of new archival documents such as parish and judicial records. Still, the use of ethnography, visual images, oral traditions, dance, music, and material culture, as well as archaeological evidence, can contribute to address the persisting lacunas and silences of written sources and capture the complex nuances of urban slavery.