Introduction

As a critical part of Canada’s continuing health care system, long-term care (LTC) services (i.e., nursing homes, LTC facilities) serve a predominantly older population (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2014). These services are facility based, meaning that residents live in communal dwellings with 24 hour nursing care, which is provided by staff primarily, but is also complemented by family members and formal and informal volunteers. Although LTC is effectively a “home” for residents, facilities are highly regulated and often hospital-like. Efforts to improve LTC residents’ living conditions have focused on quality of care standards derived from monitoring residents’ medical, social, physical, and emotional status (Ulsperger & Knottnerus, Reference Ulsperger and Knottnerus2008). As LTC is not included in the Canada Health Act, these standards of care are set provincially and enforced by provincial regulating agencies, resulting in provincial variations and frequent regulatory process tensions. Although LTC institutions exert considerable influence over how LTC relationships are organized, provincial regulatory and government-endorsed policy documents constitute the basic frameworks within which institutional policies are developed.

Quality of care is related to the technical processes involved in health care delivery (Bowers, Fibich, & Jacobson, Reference Bowers, Fibich and Jacobson2001) as monitored and regulated by government. A medical perspective is used to conceptualize and address LTC quality of care problems (Campbell, Roland, & Buetow, Reference Campbell, Roland and Buetow2000); however, in the last 20 years, researchers, residents, and advocacy groups have called for LTC to move beyond quality of care towards improving resident quality of life (QoL) (Cooney, Murphy, & O’Shea, Reference Cooney, Murphy and O’Shea2009). To date, this culture change has been poorly reflected in most LTC policy.

Volunteers and the Challenge of QoL in LTC

Research on LTC residents’ QoL has generated domains indicating a good QoL for residents: relationships, autonomy, dignity, meaningful activities, privacy, physical comfort, individuality, enjoyment, security, spiritual well-being, and functional competence (Kane, Reference Kane2001). Conversely, researchers have found that fixed routines, lack of privacy, boredom, inactivity, and loneliness negatively impact residents’ QoL (Kane et al., Reference Kane, Kling, Bershadsky, Kane, Giles and Degenholtz2003; Ulsperger & Knottnerus, Reference Ulsperger and Knottnerus2008). Improving interpersonal relations among residents, staff, family members, and volunteers is integral to enhancing these QoL domains in LTC facilities (Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems, & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Reference Oosterveld-Vlug, Pasman, van Gennip, Willems and Onwuteaka-Philipsen2013; Seitz, Knuff, Prorok, Le Clair, & Gill, Reference Seitz, Knuff, Prorok, Le Clair and Gill2016). Yet, amidst nursing staff shortages and neoliberal policy mechanisms that increase paperwork, in addition to LTC staff auditing responsibilities in Canadian residential facilities (Banerjee & Armstrong, Reference Banerjee and Armstrong2015), paid caregivers have little time to engage in interpersonal work and relational resident care. Unpaid, informal caregivers (predominantly family) often struggle to “fill the gaps” in care by attending to intimate and unforeseen details in residents’ lives. Formal LTC volunteersFootnote 1 are also relied upon to help pick up the slack; through their roles, they make unique contributions to older residents’ QoL, which we discuss in our subsequent literature review.

According to Lai (Reference Lai2015), reliance on informal and unpaid care to enhance quality has ushered in “new governance” approaches to improving LTC and other complex public-sector institutions. New governance approaches to LTC are characterized by “soft law”, or non-coercive policies, that encourage non-state actors (e.g., friends, family, volunteers, and community organizations) to collaborate in problem-solving improvements to quality in LTC institutions. In Canada, this is evidenced in both provincial and federal policy documents that encourage families’ and volunteers’ participation on councils and other programming initiatives aimed at improving LTC quality of care and QoL. This historical shift towards new responsibilities for volunteers to help improve LTC quality are also cultural and may be implicitly felt by volunteers, even when not explicitly reflected in regulatory policy expectations.

Nevertheless, the relative lack of attention to relational care and the critical roles of LTC unpaid caregivers has limited conceptualizations of QoL (Daly, Reference Daly, Armstrong and Braedley2013) and how “non-state actors’” contributions to QoL are recognized and supported. This is reflected in the dearth of literature on LTC volunteers and their scarce mention in provincial and territorial regulatory policies that govern and inform Canadian LTC facilities. As a result, there is evident tension and inconsistency in LTC volunteers’ roles, and volunteers’ potential to enhance older residents’ QoL remains underdeveloped.

In this article, we examine regulatory policies up to 2017 for LTC facilities’ volunteers in four provinces: Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, and Ontario. Our analysis examines regulatory policy texts and how they might help or hinder volunteers from playing important roles in improving QoL for older people (those 65 years of age and older) in LTC facilities. We found that most provincial policy fails to address the roles of volunteers. What language does exist has conflicting role interpretations and tends to limit these roles (particularly in Alberta and Nova Scotia), rather than exhorting LTC institutions to facilitate practical, creative, and unique avenues and mechanisms for volunteer engagement (with the exception of Ontario). This happens primarily through: (1) omitting volunteers from most regulatory policy, (2) likening volunteers to supplementary staff rather than to caregivers with unique roles, and (3) overemphasizing residents’ “safety, security and order,” rather than volunteers’ relational activities with residents.

Research shows that the roles of and desire for LTC volunteers is growing and that we will likely soon see expanded language describing volunteers in Canadian LTC policy. Therefore, this is a critical time for policy analysis to inform these policy changes. Rather than simply highlighting promising policy, however, we suggest that changing regulatory policy for LTC volunteers will not necessarily enhance residents’ QoL. Regulatory procedures in and of themselves may be inadequate or ill-suited to address the cultural, social, and structural changes needed for volunteers to enhance QoL in LTC settings. Following a review of literature on volunteers working with older people in LTC facilities, we examine related four jurisdictions’ regulatory policies, analyzing the QoL domains supported in each policy text and noting emerging cross-jurisdictional trends. We then consider how interpretations of these texts may enhance or thwart volunteers’ capacity to improve LTC residents’ QoL, and conclude by highlighting promising new policy directions for LTC volunteers and offering suggestions for future policy work and research on policy development and implementation processes, which are beyond the scope of this article.

Literature

The growing body of literature on volunteer contributions to the quality of care and QoL of older people focuses on volunteer roles, activities, and motivations, and identifies the continuing care sector’s challenges in recruiting, training, coordinating, and retaining volunteers. In 2013, Morris, Wilmot, Hill, Ockenden, and Payne published a literature scan of volunteers’ contributions to end-of-life services, noting that volunteers who work with people with dementia and/or those at the end of their lives often draw on previous experiences of loss and are motivated by deeply personal desires to support others going through similar experiences. Some researchers (see, for example, Thompson & Wilson, Reference Thompson and Wilson2001) have argued that older volunteers’ unique skills and life circumstances are an important under-tapped resource for volunteer recruitment and programming in LTC; palliative and hospice care should be specifically targeted to older (semi-) retired volunteers with requisite life experience. However, there is growing interest in the potential of younger volunteers to enhance LTC intergenerational relations (Blais, McCleary, Garcia, & Robitaille, Reference Blais, McCleary, Garcia and Robitaille2017; Østensen, Gjevjon, Øderud, & Moen, Reference Østensen, Gjevjon, Øderud and Moen2017).

Expanding volunteer roles, services, and programming is generally understood as a cost-saving strategy (Østensen et al., Reference Østensen, Gjevjon, Øderud and Moen2017) that “adds value” to existing services and offers a good investment (Andfossen, Reference Andfossen2016; Johnson & Cameron, Reference Johnson and Cameron2019; Morris, Wilmot, Hill, Ockenden, & Payne, Reference Morris, Wilmot, Hill, Ockenden and Payne2013). Therefore, well-developed volunteer programs are understood to “make good business sense” in LTC institutions and often serve as a stopgap response to funding cuts and staff shortages in non-profit facilities (Hussein & Manthrope, Reference Hussein and Manthrope2014; Lowndes, Daly, & Armstrong, Reference Lowndes, Daly and Armstrong2017; Watts, Reference Watts2012). Nevertheless, some research frames volunteers as playing crucial roles beyond resource investments and supplementary staff labour. Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Wilmot, Hill, Ockenden and Payne2013), for example, suggests that volunteers should be “used in innovative ways” through programming that enriches services and creates new ways of thinking about QoL and quality of care for older people. Innovative programming and exploratory approaches are currently concentrated in dementia care or palliative and hospice care research, where volunteer programming seems most developed (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Damianakis, Kröger, Wagner, Dawson and Binns2014; Ducak, Denton, & Elliot, Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018; Guirguis-Younger & Grafanaki, Reference Guirguis-Younger and Grafanaki2008; Hunter, Thorpe, Hounjet, & Hadjistavropoulos, Reference Hunter, Thorpe, Hounjet and Hadjistavropoulos2020; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Wilmot, Hill, Ockenden and Payne2013; Seitz et al., Reference Seitz, Knuff, Prorok, Le Clair and Gill2016; Watts, Reference Watts2012). Candy, France, Low, and Sampson (Reference Candy, France, Low and Sampson2015) argue that much more needs to be investigated regarding the “the mechanisms or aspects of the volunteers’ role that may lead to beneficial effects” (p. 766).

Volunteers’ Roles

Volunteers play diverse roles in supporting many LTC activities. In Canada, research reveals that formal LTC volunteer work can include personal or “friendly” visiting, mealtime assistance, administrative duties, fundraising, special programming (such as bingo, spa treatments, pet therapy, or music), or organizing special events (Vézina & Crompton, Reference Vézina and Crompton2012). Research tends to concentrate on the volunteer roles of LTC ombudsmen in the United States, and more generally, in spiritual care, mealtime assistance, and other community-based programming, often tailored for specific faith-based or ethno-cultural communities or people with specific psychosocial needs (Damianakis, Wagner, Bernstein, & Marziali, Reference Damianakis, Wagner, Bernstein and Marziali2007; Ducak et al., Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018; Falkowski, Reference Falkowski2013; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Thorpe, Hounjet and Hadjistavropoulos2020; van Zon, Kirby, & Anderson, Reference van Zon, Kirby and Anderson2016). The roles of volunteers working with older people also vary depending on the location of services, type of care provision, and funding arrangements of the service provider. In non-profit LTC settings, several studies (Funk & Roger, Reference Funk and Roger2017; Johnson & Cameron, Reference Johnson and Cameron2019) have argued that volunteers help “fill the gap” in staff shortages (Hussein & Manthrope, Reference Hussein and Manthrope2014), particularly providing support for residents during mealtimes (Lipner, Bosler, & Giles, Reference Lipner, Bosler and Giles1990; Lowndes et al., Reference Lowndes, Daly and Armstrong2017). In palliative care settings, Watts (Reference Watts2012) warns that improperly supported volunteer roles risk positioning volunteers as “handmaidens to the professional care team” (p. 115), thus engendering resentment from professional staff. In LTC, Tingvold and Skinner (Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019) found that lack of clarity about volunteer roles and limited opportunities for staff to learn about volunteer activities led to a variety of coordination challenges and staff conflict. Similarly, Keith (Reference Keith2001) and Nelson, Netting, Borders, and Huiber (Reference Nelson, Netting, Borders and Huiber2004) both underscore the significance of administrative support for LTC volunteer ombudsmen to minimize their conflict with staff, enhance the efficacy of their work, and motivate their continued volunteering despite inevitable challenges. Hunter et al. (Reference Hunter, Thorpe, Hounjet and Hadjistavropoulos2020) found that, with proper supports and training, staff are enthusiastic about volunteers’ complementary LTC roles. Similarly, Hurst, Coyne, Kellet, and Needham (Reference Hurst, Coyne, Kellet and Needham2019) argue that volunteers with LTC residents with dementia not only benefit residents, but also staff and the larger organization; however, clarification about volunteer roles is key for enhancing these contributions.

In an American context, Falkowski (Reference Falkowski2013) noted that non-profit and for-profit LTC institutions had distinctly different volunteer roles. Non-profit institutions tend to have much larger volunteer pools and more frequent volunteer visits. These volunteers were “flexible,” serving primarily to support/supplement staff and sometimes allowing staff to spend more time with residents, although activities were not organized around residents’ interests per se. For-profit settings, on the other hand, tended to recruit volunteers for specific programs geared towards residents’ “socialization.” These volunteer activities were heavily organized and often restricted volunteers’ scope of activities, which placed additional strains on LTC staff. In the United Kingdom, Johnson and Cameron (Reference Johnson and Cameron2019) argue that LTC volunteers are usually conceptualized as “a spare pair of hands” to fill the gaps in care, or as the “cherry on the cake” to augment existing services. However, in care settings that are strapped for resources and funding, the line between volunteers and paid care workers was blurred (see also Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe, Andrews, Agelink, Zegers, Cornes and Smith2003). Similar studies that contrast volunteers in non-profit and for-profit LTC institutions (McGregor & Ronald, Reference McGregor and Ronald2011) have suggested similar trends.

Several studies attempt to clarify volunteers’ roles vis-à-vis staff and family members. For the most part, this research emphasizes that volunteers tend to excel in relational care rather than task-based medical care provided by staff (Ducak et al., Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Thorpe, Hounjet and Hadjistavropoulos2020; Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe, Andrews, Agelink, Zegers, Cornes and Smith2003; Mellow, Reference Mellow, Benoit and Hallgrímsdóttir2011; Seitz et al., Reference Seitz, Knuff, Prorok, Le Clair and Gill2016). In the United Kingdom, Hussein and Manthrope (Reference Hussein and Manthrope2014) showed that, largely, volunteers did not supplement staff but rather supported LTC residents with counseling, support, advocacy, and advice, which are increasingly out of the purview of paid staff. Technology-based programs, administered exclusively by volunteers, seem also to enhance residents’ autonomy in specific ways (Østensen et al., Reference Østensen, Gjevjon, Øderud and Moen2017; van Zon et al., Reference van Zon, Kirby and Anderson2016). Similar trends are found in in Norway, where volunteer activities complemented staff duties by focusing on “cultural, social and other activities aimed at promoting mental stimulation and well-being” (Skinner, Sogstad, & Tingvold, Reference Skinner, Sogstad and Tingvold2018, p. 1007). Andfossen (Reference Andfossen2016) argues that managed volunteers (those screened and trained) in Norway serve a highly organized, “non-personal” role unique from that of family and unmanaged volunteers, which should be better reflected in LTC policy and programming in order to maximize its potential to improve LTC. Some researchers (Candy et al., Reference Candy, France, Low and Sampson2015; Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2004; Guirguis-Younger & Grafanaki, Reference Guirguis-Younger and Grafanaki2008; Mellow, Reference Mellow, Benoit and Hallgrímsdóttir2011) have argued that volunteers’ altruistic motivations distinguish volunteers from both staff and family and uniquely situate them to enhance QoL for families, staff, and residents. Mellow (Reference Mellow, Benoit and Hallgrímsdóttir2011) notes that direct service hospital volunteers have more control of their time, so they can engage in affective dimensions of care that is crucial to improving quality of care and dignity in highly regulated care environments. Guirguis-Younger and Grafanaki (Reference Guirguis-Younger and Grafanaki2008) argue that palliative care volunteers play an integral role because they are motivated to share their “emotional resilience” with families and people who are dying. Volunteer choice and flexibility appear to be integral to volunteers’ abilities to make specific and valuable contributions in palliative care. Weeks, MacQuarrie, and Bryanton (Reference Weeks, MacQuarrie and Bryanton2008) make similar observations in hospice palliative care (HPC) settings (including homes, hospitals, and LTC facilities), arguing that volunteers provide a “unique care link” between paid and unpaid caregivers, indirectly benefitting HPC users. Although Weeks et al. (Reference Weeks, MacQuarrie and Bryanton2008) note that volunteer roles are highly context specific, in general, volunteers play an “in-between-role”, allowing for family confidences and contributing to sustained relationships even after death, while also acting as a buffer between family members and staff. This role differed significantly from that of paid staff, even in non-profit settings.

Many of these roles are difficult to “train” for or standardize, as they are frequently nuanced and often informed by volunteers’ years of lived experience caring for older people (Candy et al., Reference Candy, France, Low and Sampson2015; Mellow, Reference Mellow, Benoit and Hallgrímsdóttir2011; Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, MacQuarrie and Bryanton2008). Further, Ferrari (Reference Ferrari2004) and Funk and Roger (Reference Funk and Roger2017) both note that despite trends towards LTC volunteers’ routinization and regulation (Candy et al., Reference Candy, France, Low and Sampson2015; Watts, Reference Watts2012), volunteers seem to value autonomy and control in their activities and may be deterred by heavily formalized volunteer environments. Nevertheless, research (Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2004; Funk & Roger, Reference Funk and Roger2017; Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe, Andrews, Agelink, Zegers, Cornes and Smith2003; Tingvold & Skinner, Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019) has shown that volunteers benefit from organizational support and clear roles and expectations.

Challenges of Managing Volunteers

Numerous studies emphasize the importance of appropriate LTC volunteer training, coordination and support (Damianakis et al., Reference Damianakis, Wagner, Bernstein and Marziali2007; Falkowski, Reference Falkowski2013; Landau, Brazil, Kaasalainen, & Crawshaw, Reference Landau, Brazil, Kaasalainen and Crawshaw2013; Lipner et al., Reference Lipner, Bosler and Giles1990; Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe, Andrews, Agelink, Zegers, Cornes and Smith2003; Tingvold & Skinner, Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019), even as such strategies for volunteers are becoming more complexFootnote 2 . In the United States, Thompson and Wilson (Reference Thompson and Wilson2001) suggest that management strategies should be tailored to older volunteers, who seem to do particularly well supporting older LTC residents. Their recommended strategies include having well-resourced, centralized volunteer agencies, incentives, and mechanisms allowing volunteers to play active and creative LTC roles. In the United Kingdom, research suggests that volunteer programs should recruit from relevant voluntary sector organizations (Manthorpe et al., Reference Manthorpe, Andrews, Agelink, Zegers, Cornes and Smith2003), so that recruitment efforts target volunteers with prior experience and organizational support. In Norway, Tingvold and Skinner (Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019) noted that staff should be actively engaged in volunteer programming and training to increase understanding of volunteers’ value and exert some control over coordination with staff activities. In Canada, efforts have long been underway to develop “best practices” for volunteers (especially in palliative care) and quality indicators for accrediting volunteer agencies (Guirguis-Younger, Kelley, & McKee, Reference Guirguis-Younger, Kelley and McKee2005). Strategies to enhance volunteer experience and motivational recruitment and retention tools for volunteers working with older people in LTC have also grown increasingly sophisticated over the last 30 years (see Claxton-Oldfield, Wasylkiw, Mark, & Claxton-Oldfield, Reference Claxton-Oldfield, Wasylkiw, Mark and Claxton-Oldfield2011; Duncan, Reference Duncan1995; Landau et al., Reference Landau, Brazil, Kaasalainen and Crawshaw2013; Lipner et al., Reference Lipner, Bosler and Giles1990).

Despite these initiatives, Tingvold and Skinner (Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019) note that there are often limited time and few operational mechanisms in place to support effective LTC volunteer integration and coordination, which is reflected in high volunteer turnover and conflict between staff and volunteers. Notably, these challenges appear to manifest in ineffective volunteer policies, or in implemented policies that fail to account for LTC realities. In many cases, policy change is not the best response to challenges experienced by LTC volunteers. In fact, many LTC volunteers do not want their roles formalized in policy and procedures (Funk & Roger, Reference Funk and Roger2017), as these can undermine their experiences with residents and create discriminatory recruitment practices (Watts, Reference Watts2012). Other research warns that formalization might be negatively correlated with what volunteers do best: provide nuanced relational care (Guirguis-Younger et al., Reference Guirguis-Younger, Kelley and McKee2005). Mellow (Reference Mellow, Benoit and Hallgrímsdóttir2011), for example, describes how direct service hospital volunteers must work creatively around regulatory constraints, which focus primarily on instrumental tasks, in order to provide affective, intimate care and maintain dignity in their work. Finally, Banerjee and Armstrong (Reference Banerjee and Armstrong2015) and Kane (Reference Kane2001) suggest that moves towards further regulating LTC (including LTC volunteers) are more reflective of an increasingly risk-averse care culture, rather than an effective enhancement for QoL or quality of care. They argue that further regulation may strain staff resources and obscure systemic problems in LTC.

With these cautions in mind, the diverse volunteer roles and activities we discussed here have the potential to enhance all 11 of Kane’s QoL domains. Yet, how volunteers are recognized and supported varies considerably across Canada’s expanding patchwork of LTC policy. In the following sections, we detail our analysis of how formal volunteer roles—those that require management, regulation, screening and training—are defined in four provincial regulatory contexts in ways that might inhibit or enhance LTC residents’ QoL.

Methods

This present study is part of a larger policy analysis associated with a Pan-Canadian multi-method research project, Seniors – Adding Life to Years (SALTY). SALTY aims to enhance QoL for LTC residents in Canada during their later years using an integrated knowledge translation approach. The SALTY research team involved non-researcher stakeholders, including policy makers and health professionals, and LTC end users such as volunteers, family members, residents, and people with dementia. These stakeholders assisted in research design and analysis to ensure that our research addressed priority areas for those most impacted by policy changes (see Keefe et al., Reference Keefe, Hande, Aubrecht, Daly, Cloutier and Taylor2020, for a more detailed description of the overall project). It was also these stakeholders who identified a volunteer perspective or “lens” on LTC policy as a priority research area.

The policy analysis team collected data by scanning public repositories in four provincial jurisdictions—Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, and Ontario—to identify policy documents related to residential, long-term, and end-of-life care. No policy documents were collected after July 2017, with the exception of the Minister of Justice’s (2017) Framework on Palliative Care in Canada Act and the Government of Alberta’s (2018) Resident and Family Council Act, which was approved and operational in Alberta. These were included as a result of feedback from the project’s policy stakeholders. The initial search resulted in 350 policy documents by numerous non-governmental organization (NGO) authors that encompassed legislative, best practice, and strategic papers with varying goals. In order to refine our policy data pool, inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied in a series of stages to ensure that the policy document related to the overarching research question: How does existing policy enable or inhibit the QoL of residents in LTC facilities? First, the documents needed to refer to current LTC residents 65 years of age and older (versus those waiting for admission into facility care), second, the document was to be prescriptive in nature (versus descriptive or background documents), and, finally, the document had to relate to facility care or be inclusive of facility care. The projects policy stakeholders also made recommendations to remove a couple of the initially included documents because their texts resembled hiring criteria more than policy direction. After applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria and consulting with project stakeholders, a total of 139 policy documents were selected, constating our base policy library.

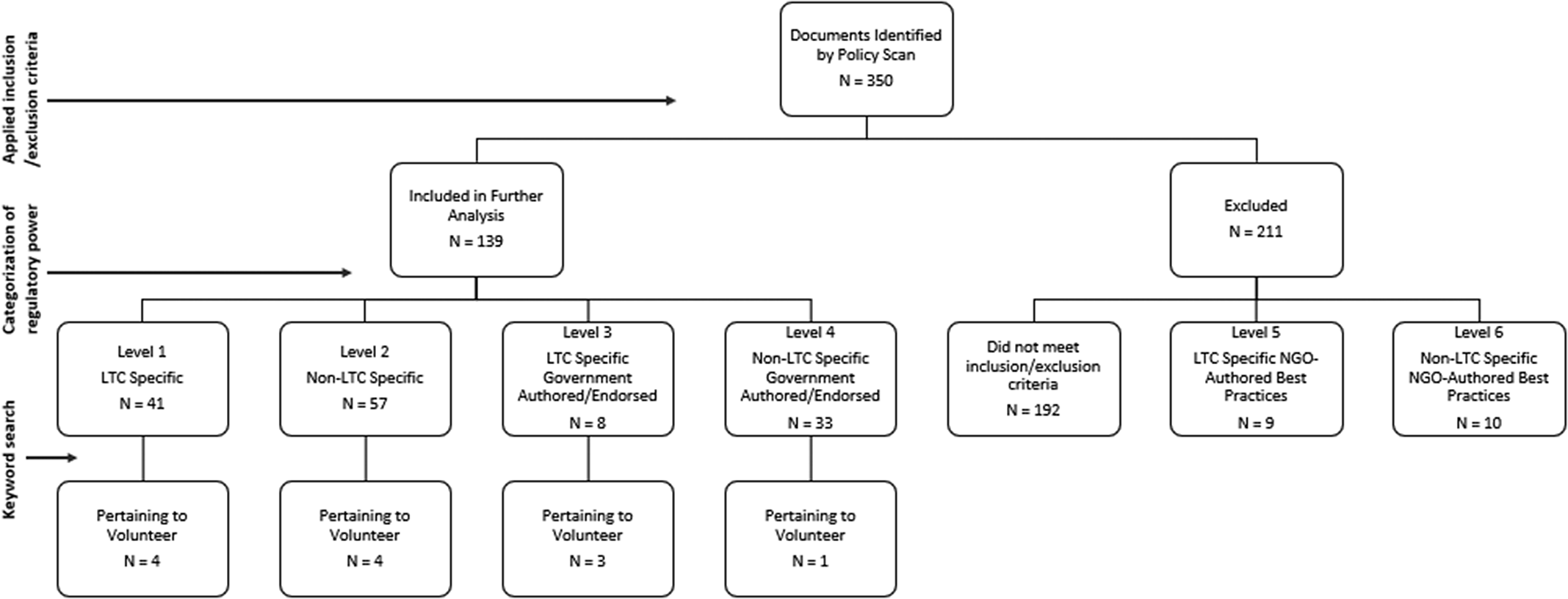

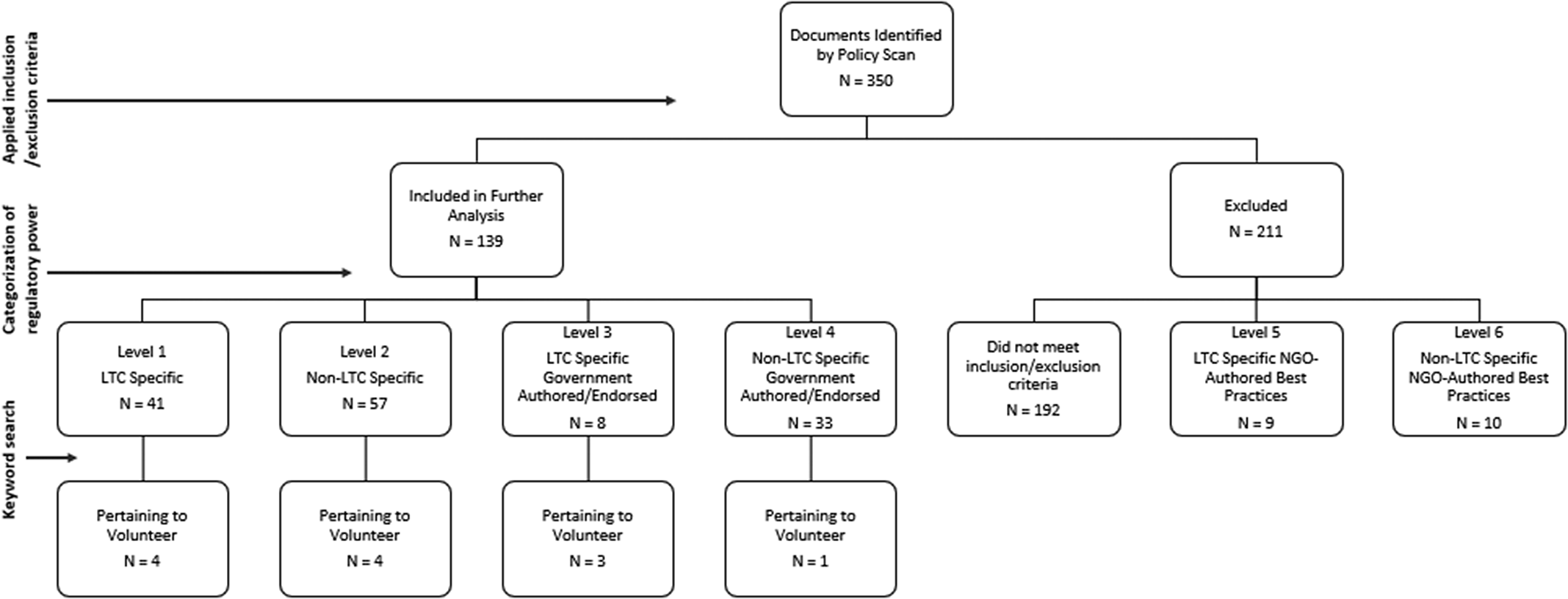

After finalizing our policy library, we described and categorized the documents using deductive content analysis (Schreier, Reference Schreier and Flick2014). All 139 documents were categorized into six regulatory power levels to determine LTC facilities’ degree of compliance: level 1 policies are compulsory LTC-specific provincial or federal regulations, whereas level 6 policies are voluntary, non-LTC-specific best practice documents. After consultation with project stakeholders, the decision was made to anchor our policy analysis (as it relates to QoL) in the highest regulatory levels (1 and 2). Each document was scanned for keywords related to various LTC policy lenses, including the “volunteer lens”; the term “volunteer” was used to search policy documents for inclusion in the “volunteer lens” analysis. Initially, only regulatory policies (levels 1 and 2) were searched and included, yielding nine documents. In one of these documents, the volunteer-relevant text excerpts were entirely duplicated; therefore, the older of the two documents was eliminated as being redundant, leaving eight texts. This scant data set prompted the researchers to expand their search to include levels 3 and 4 (government-endorsed documents), which yielded an additional 4 documents (making 12 in total). Figure 1 shows how the overall policy library was refined and organized to facilitate a volunteer focus. Inclusion/exclusion criteria, coding, data categorization, and interpretation were discussed and refined regularly at research team meetings.

Figure 1. Selection process for LTC volunteer policy documents

/Next, text excerpts (with the word “volunteer”) from the 12 documents were inserted into an Excel spreadsheet for inductive interpretive analysis. These excerpts were coded according to Kane’s (Reference Kane2001) 11 QoL domains, to determine which domains are best supported in existing provincial policy. We followed Kane’s QoL domain descriptions in including a sense of: (1) “Safety, Security and Order” meaning that residents can trust that their living environment is benevolent and organized by ordinary ground rules; (2) “Physical Comfort,” meaning that residents are free from physical pain and discomfort caused by symptoms or the environment; (3) “Enjoyment,” through programming and physical settings; (4) “Meaningful Activity,” according to personal preferences; (5) “Reciprocal Relationships” with anyone living, visiting, or working in the LTC facility; (6) “Functional Competence,” so that the resident is as independent as possible, depending on impairments; (7) “The Resident’s Dignity” or unique humanity must be respected; (8) “Resident Privacy,” which means having control over when one is alone and what information is shared about oneself; (9) “Individuality,” through residents expressing identity and having a desired continuity with the past; (10) “Autonomy/Choice” that enables residents to have some direction in their respective lives; and (11) “Spiritual Well-Being,” which includes, but is not limited to, religiousness.

To guide our coding, we used a modified objective hermeneutics method (Mann & Schweiger, Reference Mann and Schweiger2009) to interpret policies according to QoL domains. We sought to uncover not necessarily the intent or the potential outcomes of the policy text, but rather how it might be interpreted based on the text alone. For example, if the policy excerpt did not explicitly refer to privacy issues (even if implications could be inferred), it was not coded as relevant to the “Privacy” QoL domain. At least two researchers analyzed each text excerpt independently and then compared excerpt coding to ensure consensus on the direct link (interpretation) between the excerpt and (a) particular QoL domain(s). Text excerpt coding was discussed and finalized through consensus during larger research team meetings. Once coding was complete, emerging themes and key findings were discussed at subsequent team meetings and shared with project stakeholders. Policy data and applicable domains are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Policy data summary

Note. All federal policy data collected on the “volunteer lens” was categorized at either 5 or 6, or the data were collected on an ad-hoc and supplementary basis.

LTC = long-term care; DHW = Department of Health and Wellness

As mentioned earlier, there are numerous regulatory tensions caused by the decentralized, patchwork nature of Canada’s LTC policy, which exist at multiple levels (federal, provincial, regional, facility) and are sometimes poorly aligned. Therefore, linking policies with QoL domains was often complicated (see Taylor and Keefe, submitted, for more detail on this methodological approach). Ultimately, however, linking QoL domains to these policy text excerpts enabled us to develop a clearer idea of which domains have more leverage in various jurisdictions and which ones might require more work at the policy level to ensure clarity and consistency as to how LTC volunteer activities are coordinated.

Findings

Alberta

Four pieces of policy were identified in Alberta: two at the regulatory level, and two that are government endorsed. The regulatory policies are categorized as level 2 (not LTC-specific). They include language mandating that LTC facility operators ensure that volunteers are trained, that volunteers have limited involvement in residents’ personal affairs, and that operators maintains a physical environment comfortable for everyone who occupies the facility, including volunteers. The level 2 document Continuing Care Health Services Standards (Alberta Health Services, 2016) mentions volunteers sparingly as one kind of caregiver requiring proper training before using the facility’s equipment, technology, and supplies. This language applies only to the “Safety, Security and Order” domain.

The Accommodation Standards and Licensing Information Guide (Government of Alberta, 2011) (also level 2) is much more expansive. Six excerpts from this document state that LTC operators must ensure a clean, comfortable environment, including for volunteers; operators must ensure that volunteers receive training in security, communication, and emergency call systems; volunteers must complete a criminal record check; volunteers must be familiar with policies designed to maintain residents’ privacy and personal information; LTC facilities must have policies documenting staff and volunteer involvement in residents’ personal affairs; and written policies must be provided to residents, their representatives, staff, and volunteers. Altogether, these texts suggest that volunteers are expected in the LTC facility, their physical comfort is prioritized, and they might receive similar training to staff regarding equipment use and technology, privacy, and personal information. The policies so infrequently mention volunteers, however, that volunteers’ role(s) in improving residents’ QoL remain(s) unclear. The QoL domains coded here are still predominantly “Safety, Security and Order”, and touch on “Physical Comfort” and “Privacy” domains. In each instance, however, volunteers are treated as counterparts of paid staff and therefore are subject to much of the same training, policy oversight, and policy documentation. This might be interpreted as LTC volunteer “support”, yet it is minimal and does not guarantee an increased or clarified role for volunteers. Despite more frequent mention of volunteers in the Guide, the policies have a narrow focus, addressing only three of the 11 QoL domains. We read this language as restricting volunteers’ role rather than encouraging volunteer involvement and support through the creation of opportunities.

Non-regulatory, government-endorsed documents (at levels 3 and 4) suggest more relational and distinctive roles for volunteers. A New Vision For Long Term Care Mirosh Report (Mirosh, Reference Mirosh1988) frames volunteers not as staff counterparts, but rather as outside sector representatives from community organizations and corporate agencies that might contribute funding for older people’s service delivery. The document recommends that “the volunteer sector be considered an integral part of the long term care system”, and that “every effort should be made” (Chapter 6) to ensure that these volunteers can contribute to LTC. This language supports volunteers’ relationships with older residents, and perhaps underscores the government’s growing interest in community and corporate involvement in LTC homes. This volunteer role is reiterated in Palliative and end of life care: Alberta provincial framework (Alberta Health Services, 2014), which likens supports that volunteers can provide to non-governmental offices and community-based services, all of which, the Framework argues, must be better integrated into various palliative services and supports. Again, this language suggests that volunteers play a key role in supporting the “Relationships” and “Physical Comfort” QoL domains.

British Columbia

British Columbia has no LTC-specific regulatory policy that mentions “volunteers” explicitly. However, two level 2 policies—BC Home and Community Care Policy Manual (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2016) and Model Standard For Continuing Care and Extended Care Services (British Columbia Ministry of Health and Ministry Responsible for Seniors, 1999)—outline volunteers’ role in improving resident relations by identifying and enhancing appropriate communication channels. Although these texts are brief, they suggest broader, more subjective volunteer roles, in which volunteers might creatively tailor their activities according to residents’ specific needs and preferences. The BC Policy Manual (British Columbia Ministry of Health, 2016) encourages health authorities to support resident/family councils by, among other things, “identifying communication channels and encouraging collaborative relationships among staff, families and volunteers” (Chapter 6). This language suggests that volunteers can, and perhaps should, play a collaborative role in LTC residents’ care spheres. Giving volunteers an active, collaborative role might create new opportunities through which they can enhance other resident QoL domains with support from paid and unpaid caregivers networks.

The latter document, Model Standard (1999), outlines a potentially specific role for volunteers—facilitating good communication with residents by serving as language interpreters—if staff or other caregivers cannot communicate with the resident. Although this certainly enhances the “Relationship” QoL domain, it also has the potential to enhance QoL for residents within the “Functional Competence” and “Individuality” domains. Here volunteers are asked not only to play a resident-centered role, but also to support staff and possibly enhance relationality across various caregivers. Despite these policy excerpts being more relationship oriented than those in Alberta, we note that they enhance residents’ QoL in a very small number of domains, with relatively limited scope in each. There appears to be no indication that volunteers might play a broader or more central role in augmenting residents’ overall QoL.

Nova Scotia

Long Term Care Program Requirements (Nova Scotia Health and Wellness, 2016) is the only relevant regulatory policy (level 1) in Nova Scotia that includes language pertaining to LTC volunteers. In its first statement, volunteers are grouped with employees and are subject to policies and procedures limiting their involvement in residents’ personal affairs. This language suggests that, in Alberta and Nova Scotia, there is no overlap between family or close friends and volunteers. In other words, volunteers play a formal role—similar to that of staff—distant from residents’ personal lives. The second text from this policy document reads that “volunteers are supported and supervised and do not replace paid staff” (Section 11). Here it is clarified that volunteers might be subject to some staff policies and regulations; however, they are distinct from staff and should not engage in the same work. Nevertheless, volunteer roles and duties are not defined, and it is not clear from this latter excerpt how volunteers might be “supported” or “supervised” or how they differ from staff. There is no mention of volunteers’ relationship with, or role vis-à-vis, residents or their families. These policy excerpts differ from British Columbia and Ontario policy (discussed subsequently) in which volunteers play explicit roles in resident councils. The policy language suggests that volunteers are understood more to be workers (albeit unpaid) and distinct or discrete from friends and family; as such, the volunteer role is limited in a number of ways. We coded this policy as potentially enhancing QoL in the “Relationships”, “Privacy”, and “Safety, Security and Order” domains, although it is unclear, based on our hermeneutics interpretation, how this might happen.

One additional text was included at policy level 3: Viral Illness Outbreak Control in LTC (Nova Scotia Health and Wellness, 2014). This document lists volunteers as one of several groups that should be included in data collection and training procedures aimed at preventing illness Overall, Nova Scotia regulatory policy and government-sponsored documents provide little indication of how volunteers might have distinctive roles in LTC that differ from, yet complement, those of staff and family caregivers.

Ontario

We found four LTC-specific policies (levels 1 and 3) in Ontario that made explicit mention of volunteers. The level 1 documents—Long-Term Care Act (LTCA) Regulations (Government of Ontario, 2007), Long-Term Care Homes Act (LTCHA) (Government of Ontario, 2007), and Long Term Care Homes Funding Policy Eligible Expenditures (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2010)—provide relatively rich supports and resources for LTC volunteers and cover several QoL domains. The LTCA Regulations (2007) outline the necessity for volunteers to be screened and given some orientation or training before they work with residents. This language is most like that from the other provinces and addresses similar QoL domains: “Safety, Security and Order”, “Physical Comfort”, “Enjoyment”, “Relationships”, “Functional Competence”, and “Privacy.” The LTCHA (2007), however, is by far the most expansive, including several statements emphasizing the importance of supporting communication and healthy relationships across diverse care networks as being necessary to maintaining and improving residents’ QoL across 8 domains: “Safety, Security and Order”, “Physical Comfort”, “Relationships”, “Functional Competence”, “Individuality”, “Meaningful Activity”, “Enjoyment”, and “Spiritual Well-Being.” This document addresses many themes that are present in other previously noted provincial documents, but makes use of different language. For example, Ontario’s LTCHA (2007) mandates that licensees explicitly invite volunteers to help develop and revise mission statements for the LTC homes and collaborate with resident and family councils. This language articulates significantly more active and creative roles for volunteers than exist in the other jurisdictions in our study, and acknowledges volunteers’ contributions as being not only valuable, but perhaps also unique from those of other caregivers. The LTCHA (2007) also mandates “an organized volunteer program … that encourages and supports the participation of volunteers in the lives and activities of residents” (Section 16). This policy text is the most explicit about recognizing the importance of volunteer supports, and highlights the value of volunteers in Ontario.

Another interesting level 1 policy feature in Ontario is the listing of “volunteer co-ordinators” as an eligible expenditure under Long Term Care Homes Funding Policy Eligible Expenditures (2010), provided that they “improve the quality of life of residents” (p. 4). This demonstrates Ontario’s strategy to invest material resources in supporting volunteers because of their important role in improving residents’ QoL. Without a clear definition of QoL and how volunteers might contribute to it, however, the volunteer coordinator role is discretionary. Nevertheless, this resource allocation is supported in the level 3, government-sponsored Commitment to Care: A Plan for LTC in Ontario (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, 2004), which states that every LTC facility must employ a volunteer coordinator and recruit volunteers through liaising with other community centres, programs, and schools to facilitate intergenerational activities, events, and programming. Facilities should also develop best practices manuals for these volunteer engagement activities.

In contrast to other provinces’ disciplinary measures, particularly reflected in Alberta’s and Nova Scotia’s policy documents, Ontario seems to focus on finding resources and structures to support volunteers and mandating a collaborative role for them in resident care. Ontario moves beyond language indicating general volunteer screening and training laws. Rather than peripheral afterthoughts in policy development, volunteers in Ontario are an integral part of LTC vision, even helping to formulate LTC institutions’ mission statements.

Discussion

Several themes emerge from the volunteer lens applied to provincial policy documents outlined. Table 2 compares these themes and their applicable QoL domains across all four jurisdictions.

Table 2. Thematic analysis of LTC volunteer policy

Note. aNot explicitly mentioned in BC policy documents but mandated at a federal level.

The most common themes relate to screening practices, limitations to volunteers’ involvement in residents’ personal affairs, and supporting relationships among volunteers, staff, and family. These themes are not surprising given increasing licensing requirements, demands for further volunteer regulations to manage facility liabilities and risk, as well as federal regulations to protect “vulnerable” residents through screening and privacy protection legislation. Perhaps unsurprisingly, “Safety, Security and Order” was the most commonly applied QoL domain, showing up in almost every theme identified here, except for the themes I which volunteer roles are particularly well developed and conceptualized as being unique from staff and family roles. “Relationships” is another widely addressed domain in the policy documents that we collected, particularly in Ontario and British Columbia. This is consistent with our literature review, which underscores the critical role that volunteers play in relational care and as go-betweens in complex and diverse care arrangements. This is also in line with the increasing influence of new LTC policy governance (Lai, Reference Lai2015), wherein volunteers, as non-state actors, are increasingly seen as integral participants improving LTC quality.

There were, however, some revealing absences. Volunteer roles in palliative care policy were given scant attention in the policy documents that we reviewed. Based on our literature review, we know that volunteer roles are particularly developed and crucial in palliative care approaches, yet these are not reflected in provincial regulations or government-endorsed documents. In 2017, Canada’s federal government established palliative care policy as a key priority (Government of Canada, 2017). In our general policy scan, we found 28 government policy documents relevant to palliative care; only one— Palliative and end of life care: Alberta provincial framework (Alberta Health Services, 2014)—mentioned volunteers. If we consider palliative approaches to care as critical for improving LTC residents’ QoL (Sawatzky et al., Reference Sawatzky, Porterfield, Lee, Dixon, Lounsbury and Pesut2016), this is an important area in which volunteer roles could be, but are not currently, well supported by policy. Moreover, QoL domains “Spiritual Well-Being”, “Individuality”, and “Dignity”, were coded very rarely and the “Autonomy/Choice” domain was not coded in any policy documents. From our literature review and stakeholder feedback, we know that volunteers can and do play important roles in enhancing these QoL domains, even if this is not well reflected or supported in policy. It is possible that if volunteers were better represented in palliative care policies, these QoL domains would be better supported.

What appears in provincial policy documents is not necessarily representative of all that volunteers do to enhance LTC residents’ QoL. Nor do these policy documents represent all the levers shaping volunteers’ involvement in LTC. Indeed, institutional policies and procedures and national, non-regulatory frameworks, such Accreditation Canada’s Residential Homes for Seniors Standards (2016), certainly exert considerable influence.Footnote 3 However, they do emphasize QoL domains with the most regulatory leverage in LTC and show which volunteer roles are reinforced and supported through regulation. Overall, we noted that very few documents outline unique volunteer roles. Table 3 sketches how each of the policy documents we included represents volunteer roles by jurisdiction. Many text excerpts were vague, listing volunteers as one of many parties to whom policies apply.

Table 3. Volunteer roles by jurisdiction and policy text

Note. LTC = long-term care; DHW = Department of Health and Wellness.

There are some interesting provincial differences conceptualizing volunteer roles. In most policy documents, volunteers are only mentioned vis-à-vis staff-directed policies. This is particularly the case in Nova Scotia, where no policy document outlined a unique volunteer role distinct from those of staff. Alberta policy documentsFootnote 4 sometimes conceptualize volunteers as NGOs, corporate sponsors, or community agencies involved in LTC; these specific roles were not captured in other provinces’ policy documents. In British Columbia, volunteer roles are largely unclear, except that volunteers might be used as resources for facilitating residents’ communication and must be included in collaborative relationship-building processes with staff, family, and residents. In Ontario, all four policy documents recognized volunteers’ unique role in LTC and volunteer programming, and through mandatory resource allocation. Moreover, although British Columbia’s policy notes that volunteers might play a role in resident and family councils, in Ontario, family and resident councils are invited to collaborate with volunteers. It is unclear whether classifying volunteers in these ways effectively supports their potential to enhance residents’ QoL. Although best practice handbooks and documents might exist (at facility, health region, or even federal levels), there is very little regulatory policy that mandates programming that supports volunteers’ unique relational roles in LTC as they are outlined in our literature review. If volunteers are to be regulated, policy language that recognizes and supports these roles through programing might leverage volunteers’ opportunities to better address all of Kane’s 11 QoL domains.

Not only is there scant attention to the specific roles of volunteers, but also very few LTC policy texts mention volunteers at all. Notably only 12 policy documents, out of our pool 139 coded policies, mentioned volunteers. This scarcity might be explained in several ways: (1) volunteer roles are largely casual and/or not well defined or understood by policy makersFootnote 5 ; (2) volunteers are not considered to be key stakeholders when LTC regulatory policy is being developed (relatedly, volunteers are not conceptualized by many policy makers as contributing to LTC residents’ QoL.); (3) there have been few documented problems with LTC facilities’ volunteers; therefore, there has been little incentive to regulate their behavior further; and/or, (4) volunteers are largely managed through more general policies, such as Accreditation Canada standards, which were not part of our formal analysis. Certainly, these regulatory tensions and lack of role clarity may also restrict rather than enhance volunteers’ capacity to improve residents’ QoL. Further research is necessary to determine the leading factors leading to scant attention to volunteers in LTC regulatory policy.

Enhanced clarification around volunteers’ roles and how these various roles may be supported through creative collaboration with other LTC users should be reflected in policy documents. Some of the more promising policy texts, from British Columbia and Ontario in particular, address these issues. Volunteers are explicitly mentioned in relation to British Columbia and Ontario resident and family councils, giving them a voice that seems largely absent in Alberta and Nova Scotia. Rather than framing volunteers as potential risks to residents or caregivers who must be carefully managed, the language in many British Columbia and Ontario policy texts positions volunteers as making rich and unique contributions that improve residents’ QoL overall, and emphasizes volunteers’ complex relationality within diverse social networks. Ontario, in particular, is a leader in this regard, putting mechanisms in place to encourage collaboration with volunteers and enhance “volunteer voice”. Collaboration opportunities give volunteers meaningful and creative, rather than restrictive, roles to play. Allocated funding in Ontario for volunteer coordination also gives volunteers direction and perhaps minimizes the likelihood that care/nursing staff will have to take on the additional labour of volunteer training and direction. Ontario’s comparatively rich policy framework for volunteers owes something to the comprehensive nature of their LTCHA, which as Lai (Reference Lai2015) argues, reflects a strong adherence to a new governance approach in improving LTC quality. A similar policy framework seems to be emerging in Alberta as well, as is evidenced by the expanded role of volunteers in Palliative and end of life care: Alberta provincial framework (Alberta Health Services, 2014), which emphasizes better integration into existing services and systems rather than restricting or inhibiting volunteers’ capacity to enhance QoL. These expanded and unique volunteer roles in provincial policy texts show how volunteers might be better supported from the top down (Ducak et al., Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018).

Nevertheless, additional regulation or changes to current regulations may not address these problems. As demonstrated in Tingvold and Skinner (Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019)’s research on Norwegian volunteer and staff work, there is often insufficient time and attention spent on thoughtfully coordinating volunteer activities mandated or encouraged in policy frameworks into daily LTC processes. Moreover, Funk and Roger (Reference Funk and Roger2017) suggest that many volunteers do not want to be regulated and that LTC regulations themselves present a barrier for volunteers to improve residents’ QoL. Volunteers’ restrictions and specific obligations may conflict with volunteer motives and incentives for altruistic relationship building and a sense of meaning or purpose (Candy et al., Reference Candy, France, Low and Sampson2015; Ferrari, Reference Ferrari2004; Guirguis-Younger & Grafanaki, Reference Guirguis-Younger and Grafanaki2008; Mellow, Reference Mellow, Benoit and Hallgrímsdóttir2011). This leads to questions about the extent of volunteer regulation. Heavily regulated volunteer roles may also contradict goals to make LTC less “institutional” through mutually beneficial relations that encourage more spontaneity and creativity in LTC. These goals may be supported through policies that allow LTC residents to take some risks in their relationships with volunteers. Funk and Roger (Reference Funk and Roger2017) helpfully suggest a scale of volunteer guidelines (ranging from less to more formal roles) that might modify resident and volunteer relationships based on mutually determined terms rather than pre-determined or overly prescriptive terms.

Finally, even promising LTC policies cannot enhance QoL when austere budgets and opaque decision making dominates. Structural issues around LTC funding and ownership models may shape volunteers’ roles in ways that cannot be addressed through the provincial LTC regulations that we analyzed here. For example, Watts (Reference Watts2012) argues that austere health care funding tends to follow a business model, incorporating overly managed volunteer roles that run counter to many QoL improvement measures discussed here. Lowndes et al. (Reference Lowndes, Daly and Armstrong2017) argue that the increasing reliance on volunteers does not necessarily reflect a recognition of their unique contributions, but rather reflects the need for supplementary labour as LTC staffing levels diminish. Ensuring adequate staff compensation and resources to provide more relational care to residents may ease tensions between staff and volunteers and enhance collaboration (Lowndes & Struthers, Reference Lowndes and Struthers2016; Tingvold & Skinner, Reference Tingvold and Skinner2019). Given this structural context, better supporting volunteers through LTC care policy is just one of many strategies required to make concrete improvements to LTC residents’ QoL in Canada.

Limitations and Future Research

Our focus on regulatory and government-endorsed documents that explicitly use the term “volunteer” does not present a comprehensive analysis of who volunteers in LTC facilities, what institutional policies support or inhibit volunteers, or what gaps exist between written policy and practice. Moreover, as one of our project stakeholders stated, provincial policy may be silent in areas that are reflected in national non-regulatory frameworks. Although we have noted differences across jurisdictions, a detailed analysis of the specificities of each regulatory context is beyond the scope of this analysis but warrants further investigation. Questions that require further research include: How much LTC volunteer care is formalized through screening and training as opposed to “unmanaged” or casual roles? Are certain QoL domains better supported through unmanaged volunteer roles? How much of the Canadian volunteer force is motivated by faith-based, ethno-cultural, or program-specific LTC activities, and to what degree can these activities enhance the overall QoL of all LTC residents? Is there a role for regulatory policy in enhancing volunteer diversity to better attend to the changing LTC resident population? How does current policy reinforce gender divisions in informal care provision and how might this change at the policy level? Finally, more Canadian research is needed on policy’s role in changing relationships among LTC volunteers, staff, and management, and on how these changes could impact volunteers’ capacity to enhance LTC residents’ QoL.

Conclusion

Demand for LTC volunteers is increasing in Canada and existing literature suggests that the contributions volunteers make to resident QoL are important and unique. Despite limitations, our analysis offers some timely insights into the role of Canada’s regulatory policy in both enabling and inhibiting volunteers to enhance LTC residents’ QoL. We analyze several gaps in policy, particularly palliative policy, where volunteers currently lack regulatory support for their contributions to residents’ QoL, notably in the “Autonomy/Choice” domain. Although we discuss the limitations of relying too heavily on LTC regulatory change for enhancing residents’ QoL, we also highlight some promising policy language uncovered in our analysis. This language clarifies and expands unique LTC volunteer roles, prioritizes concrete resources to support these roles, and offers guidance on how to facilitate volunteers’ active collaboration with LTC staff, families, and residents to better enhance QoL in multiple domains. Developing such regulatory policy in each jurisdiction provides consistent clarity and support for volunteers that may result in tangible improvements to resident quality of life.