By 2010, the dictatorships ruling the MENA region seemed more self-assured than ever. President Assad retained an iron grip on Syria, President Saleh of Yemen was preparing to alter the constitution to stay in power for life, and Colonel Gaddafi in Libya was now a partner, rather than an enemy, in the global war on terror. But just when the power of these regimes seemed so secure, the despair of a single person ignited a volcano that had been boiling under the surface for decades. In the Tunisian city of Sidi Bouzid, a young man named Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire following humiliating abuse by municipal officials in December. His fellow Tunisians came out within hours to protest on his behalf. After the state-sanctioned murder of protesters produced a predictable backlash (Hess and Martin Reference Hess and Martin2006), mounting demonstrations and the demurring of the military successfully pressured President Ben Ali and his family to flee the country on January 14, 2011.

Egyptians then took up the mantle, confronting President Hosni Mubarak’s police state head-on. Given Egypt’s regional and symbolic importance, activists across the region knew that whatever happened next would signify whether the Arab Spring was going to become a game changer or get passed off as a fluke. After protesters from Cairo’s Tahrir Square to Alexandria and Port Said endured a series of state-sanctioned attacks and patronizing speeches, the Egyptian people pushed back, paralyzing the country with sit-ins, strikes, and riots. After the military decided to take control on February 11, 2011, Mubarak stepped aside, at least for the time being (Holmes Reference Holmes2019; Ketchley Reference Ketchley2017; Said Reference Said2020). The impossible was really happening, and populations around the world cheered in celebration.

As discussed in the book’s Introduction, the Arab Spring inspired protests across the region and the world over. Among the six countriesFootnote 1 hosting uprisings demanding the fall of ruling regimes, protesters in Libya, Yemen, and Syria became embroiled in prolonged battles against dictatorships over the course of 2011 and beyond. The regimes’ violent responses to peaceful protesters calling for bread and dignity sent shockwaves into diaspora communities. These uprisings were what many exiles had been waiting for their whole lives, and the rebellions at home reinvigorated their activism. The Arab Spring also transformed many diaspora members’ suppressed anti-regime sentiments into public calls for liberation and voice.

The emotions that these groups felt while watching the uprisings unfold from afar – rage, horror, hope, and excitement – might have been sufficient to inspire mobilization (Goodwin et al. Reference Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2001; Jasper Reference Jasper1998, Reference Jasper2018; Nepstad and Smith Reference Nepstad, Smith, Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2001). For the diaspora members in this study, however, two hurdles posed significant obstacles to voice, that is, public, collective claims-making against authoritarianism. As I explained previously, the operation and effects of transnational repression made non-exiles too fearful and mistrustful to wage either horizontal or vertical voice against the regimes. Conflict transmission also divided anti-regime members, sapped their efficacy by directing grievances toward one another, and undermined their willingness to act collectively for a common goal. Emotions played an important role in what happened next, but diaspora members needed other conditions to fall into place in order to overcome these obstacles to transnational activism.

In order to explain the Arab Spring’s significant effects on diaspora mobilization, this chapter builds on the theory of “quotidian disruption” proposed by sociologist David Snow and his collaborators (Reference Snow, Cress, Downey and Jones1998). Snow et al. argue that major disruptions to the quotidian – that is, the normative routines and attitudes that guide everyday life – stoke mobilization by motivating previously disempowered actors to engage in activism. Extending this theory to diasporas and their transnational practices, I propose that the disruptions caused by the Arab Spring stoked public, collective claims-making in the diaspora by undermining the normative operation and effects of transnational deterrents to activism – albeit in different ways and at varying times for each national group. Once these deterrents fell, diaspora members could at last capitalize on their civil rights and liberties abroad to express voice and consort with “stranger” conationals, thereby forging new protest movements, organizations, and coalitions for change at home.

As this chapter explains, the Arab Spring first undermined the normative operation and effects of transnational repression for Libyans and Syrians by changing the circumstances of their loved ones at home. First, when diaspora members’ relatives and friends were harmed, forced to flee, or became embroiled in the fighting, individuals abroad were released from the obligation to keep their anti-regime views a secret in order to protect their loved ones in the homeland. Second, acute regime brutality against peaceful, vanguard activists – such as Hamza al-Khateeb, a young Syrian teenager who was mutilated and tortured to death in unspeakable ways by regime agents early in the uprising – led diaspora members to take a principled stand in spite of the potential risks of coming out. As many in the United States and Britain came to believe that it would be shameful to hide their views to protect themselves or their families when protesters and innocent civilians were being slaughtered, their objects of obligation (Moss Reference Moss2016b: 493) expanded from kin to the national community writ large. Third, activists decided to go public after deducing that the risks and costs of activism had been reduced. They did so after observing that the regimes seemed incapable of making good on their threats against the diaspora while waging a full-scale war for survival at home.

The Arab Spring also broke down the normative operation and effects of conflict transmission, albeit for different durations across national groups in the United States and Britain. After regime violence unified political groups and factions in the home-country, I find that previously fractured conationals followed suit and came together to support their compatriots. While activists did not always join the same group or organization, they came to engage in a common tactical repertoire to facilitate rebellion and relief (which I discuss at length in Chapter 5) and rallied around the anti-regime revolutionary struggle. Thus, the formation of revolutionary coalitions at home against a common enemy, which Beissinger (Reference Beissinger2013) calls “negative coalitions,” was transmitted abroad through members’ ties. This led regime opponents to forge new diaspora movements and coalitions.

At the same time, the emergence of diaspora movements against authoritarianism was not a linear, uniform process. While Libyans came out rapidly in public and reported a strong degree of solidarity for the duration of the revolution in both host-countries, Syrians and Yemenis residing across the United States and Britain faced challenges due to persistent fears of transnational repression and resurgent conflict transmission. Because the Syrian regime remained relatively intact during the revolution’s escalation, transnational repression continued to pose a threat to the diaspora during the first years of the revolution. As a result, anti-regime diaspora members only gradually joined the public pro-Arab Spring movement, with many guarding their identities and voices throughout the revolution’s early stages. As the Syrian revolution became plagued by infighting, mistrust, and competition, diaspora activists too became subjected to conflict transmission and began to splinter apart once again.

Meanwhile, Yemenis did not have to overcome the hurdles posed by transnational repression because the regime was too weak to effectively repress voice after exit. Accordingly, regime violence and the outrage it caused were sufficient to motivate anti-regime individuals to come out against the regime. However, it was only after revolutionary coalitions formed at home that they overcame conflict transmission and formed new protest movements abroad. Obstacles to maintaining a unified voice for regime change reemerged, however, after regime violence prompted northern elites in Yemen to defect to the revolution. This move irked southern separatist supporters at home and abroad – the diaspora’s key anti-regime force before the Arab Spring – since the revolution coalition now included the perpetuators of southern oppression. Mirroring their compatriots at home, some Yemeni groups and activists withdrew their support as a result. In other words, conflict transmission reemerged as Yemen’s revolutionary coalition between north and south became redivided. Yemen’s Arab Spring therefore created its own hurdles to solidarity and divided the diaspora shortly after movements emerged to contest Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Taken together, the findings of this chapter demonstrate how home-country conditions and changes therein travel through cross-border ties to influence the use of voice (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970). The transnational effects of the Arab Spring had a significant, positive impact on diaspora mobilization not simply by stoking emotional distress or excitement but also by upsetting the transnational deterrents that had suppressed voice and divided their loyalties for so long. At the same time, the quotidian disruptions that brought people out and together to engage in public activism were also fleeting in some cases. As I show here, changes at home continuously shaped diaspora mobilization dynamics over time, leading to durable long-distance nationalism in some cases, and fissures or withdrawal in others.

4.1 The Breakdown (and Persistence) of Transnational Repression

4.1.1 The Libyan Case: The Implosion of Regime Control and the Diaspora’s Coming Out

Libya’s Day of Rage was announced on Facebook as planned for Thursday, February 17, 2011, a day that commemorated regime violence against protesters in Benghazi in 2006. However, protests exploded two days early on February 15 after the regime cracked down on activists and arrested Fathi Terbil, the lawyer representing the families of the Abu Salim Massacre victims. This gave already-aggrieved activists and the relatives of slain prisoners a reason to riot. As regime forces mowed down protesters with lethal force, civilians and army defectors overran the military’s barracks, forcing the brigade stationed in Benghazi to retreat. In this stunning turn of events, protesters claimed Benghazi as liberated territory. Protests then spread rapidly across the country to cities such as Misrata, Derna, Bayda, Ras Lanuf, Zawiya, and to the western capital of Tripoli. Within a week, Benghazi’s uprising had become a national revolutionary movement.Footnote 2

The regime attempted to reassert control by offering meager concessions while simultaneously killing protesters, conducting mass arrests, and shutting down the Internet. On February 21, two Libyan air force pilots flew to Malta and defected, claiming that they had been ordered to bomb Benghazi. Saif al-Islam responded by threatening to crush the uprisings in a televised address, which signaled the “final chapter in the comedy that was reform,” according to one of his advisors (Pargeter Reference Pargeter2012: 229). On February 22, Gaddafi also gave a long-winded speech; blaming foreign powers and drug-addicted protesters for the disruptions, he promised to “cleanse” Libya of “rats” and “cockroaches.” This proved to be a huge mistake, as it justified a multilateral and militarized intervention against him (see Chapter 7). Regime violence also induced widespread defections in the military, which all but imploded under the force of the exodus. Defectors formed what became known as the Free Libya Army, a loose conglomeration of underequipped fighting forces. In response, Gaddafi supplemented his loyalist forces with foreign mercenaries. Some protesters had secured small arms from abandoned military depots, but they were badly outgunned and largely untrained.

These developments were followed by a series of high-ranking defections by figures such as Mustafa Abdul Jalil, Gaddafi’s former justice minister, on February 21. He warned the international community that Gaddafi would not hesitate to annihilate entire populations, claiming, “When he’s really pressured, he can do anything. I think Gaddafi will burn everything left behind him” (Al Jazeera English 2011a; Black Reference Black2011). International institutions and heads of state condemned the “callous disregard for the rights and freedoms of Libyans that has marked the almost four-decade long grip on power by the current ruler,” as Navi Pillay, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, announced (Al Jazeera English 2011b). Within a week of the initial protests in Benghazi, the protester-regime standoff had escalated into a nationwide war that left approximately one thousand Libyans dead. On February 27, elite defectors and commanders announced the formation of the National Transitional Council (NTC) in Benghazi, giving the Free Libya Army official representation and what was to become an internationally recognized government-in-waiting.

As described in Chapter 3, Libyans in the diaspora had been largely silent on matters of home-country politics and regime change due to the threats posed by transnational repression. For this reason, the emergence of the rebellion was insufficient to automatically induce public mobilization in the diaspora. Libyans who were not previously “out” against the regime had to carefully consider whether or not to lend their faces and names to the cause out of concern for their family members at home. And yet, the majority of these respondents came out publicly against the regime in protests, community gatherings, and online forums during the onset of the revolution for three reasons.

The primary reason cited by respondents for using voice was because the conflict rapidly engulfed their relatives. When their family members joined the revolution, fled the country, or were harmed by the regime, this released persons in the diaspora from the obligation to hide their anti-regime sentiments. For example, Sarah – introduced in the Introduction – decided to attend protests at the London embassy because her family in Benghazi had joined the revolution. When Sarah called her aunt, her aunt declared,

“The whole family’s outside” – where people were being shot! And I said, “Go back inside!” and she was like “No!” You could hear shooting on the line, and she’s like, “It’s either Gaddafi or us. For us, Sarah, the fear is gone.”

For this reason, Sarah decided to do the unthinkable and go to the London embassy to protest against Gaddafi. From the Washington, DC, region, Dr. Esam Omeish, who went on to co-found a new anti-regime lobby called the Libyan Emergency Task Force (see also Chapter 5), had a similar experience. He also felt empowered to speak out in the media because his parents’ escape from Tripoli “helped us to increase our activities without fear for any reprisals against them there.” Violent repression therefore upset the relational mechanisms that had previously forced those abroad to keep their anti-regime sentiments private.

The second factor prompting activists to come out occurred after they observed vanguard revolutionaries taking brazen risks and sacrificing themselves for the cause of dignity (karamah) and freedom (hurriyah). This led respondents to embrace the potential costs of coming out for moral reasons. Even though some continued to receive threats, as when Mohammad of Sheffield received a threatening anonymous email and had his computer-based communications hacked, he said,

[With] women being raped, children being killed, innocent people being killed, I didn’t care, you know. I mean, compared to what the Libyans are going through while I’m sitting in an office in the UK, trying to help, and compared to what they do in [Libya], it is nothing.

Ahmed, a British Libyan doctor, also decided to reveal his identity during the second day of demonstrations because “there was a fire in me. People are dying! I’m talking to my friends who are protesting in central Tripoli and I’m wearing a mask? That’s ridiculous! It just didn’t seem right.” Even after agents inside of the London embassy were observed photographing the participants, Sarah recalled that “it was too late. We were out already.” Likewise, Ahmed H., a Libyan American who had been active anonymously before 2011, stated that despite the fact that his sibling was trapped in Tripoli, identifying publicly with the revolution was important for the collective effort.

I wouldn’t cover my face at that point. I made it a point to do everything – [in] all of my online communications, all my appearances, my name was being spoken. To make sure that people understood that if people are going to be out there on the front lines, sacrificing or risking their lives, then the very least I could do from the US was to make my name known and to say I’m with you, no matter what.

Adam of Virginia felt the same way, scoffing, “Everyone was just like, you know what? Screw it. If people in Libya are willing to die for it, I mean, what are you going to do? Take my picture? All right, here, I’ll take it for you – I’ll pose.”

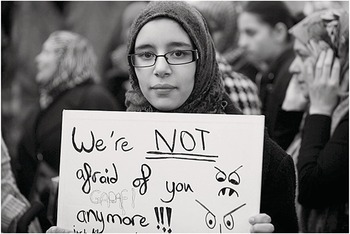

Figure 4.1. An anti-Gaddafi protester demonstrates voice by holding a sign reading “We’re not afraid of you anymore” from London in support of the Libyan revolution against Muammar al-Gaddafi.

Abdullah also recalled that Libyan students abroad came to side with the revolution rapidly in the United States, even though these students risked having their scholarships withdrawn and their families harmed. When Abdullah and his colleagues in Enough Gaddafi! talked to them in Washington, DC, “We said, ‘Aren’t you afraid? You have family in Libya!’” He recalled with admiration,

They’re telling me, “Those guys are facing bullets! The least I can do is come to a protest, you know?” [They] had this confidence and this loyalty to the lives that are being lost, the people who were dying, and the idea that, hey, we’re really on the cusp of a real change. And those were a lot of the same students who were forced to come out for Gaddafi at the UN [in 2009], protesting on the other side of the line from us.

As journalist Evan Hill (Reference Hill2011) reported for the Doha-based news agency Al Jazeera English, this shift in moral obligation also led students to explicitly refute regime threats.

For some of the students in the United States, the sight of citizens publicly calling for Gaddafi’s ouster was enough to inspire them to defy the embassy’s demands to come to Washington, DC. “I was up late all last night watching the videos of masked youths pleading to the Libyan people to rise against the oppression,” one of the students wrote in an email. “These videos have been circulating on Facebook, and after watching them I broke into tears. I will no longer accept this oppression.”

This sea change in respondents’ orientations toward risk and a new obligation to fellow nationals was both a strategy of resistance and an expression of newfound empowerment. As Mahmoud, a lifelong activist who had been shot by regime agents in London in 1984, stated, “The mask came off. It became [about] facing them eye to eye.”

As the regime was put on the defensive in Libya, the third factor prompting participants to come out was the regime’s relatively weak response to dissent in the diaspora and the rapid collapse of its outposts and informant base. Initially, activists expected a significant counter-mobilization effort because of the heavy-handed tactics used in the past. As Dina of California explained, some people refrained from joining the diaspora’s first anti-regime protests because “they thought that others were going to report back to the regime, take pictures, and take down names and send them back to Libya. So people were still afraid at first.” Osama, an organizer of the first demonstration held on February 19 in Washington, DC, recalled that they made plans for “security because [we] had an expectation that Gaddafi would send his people” to confront them and instigate a fight to discredit pro-revolution demonstrators. But while the presence of pro-Gaddafi demonstrators “shook up” those who traveled periodically to Libya, as a participant named Manal recalled, these efforts came to be perceived as an empty “scare tactic.” Mohamed of London also attested that the students who were initially coerced into attending pro-regime protests rapidly defected to the revolution side, and the throngs of pro-Gaddafi supporters that many expected to materialize never did.

The regime’s inability to deter dissent through threats and counter-demonstrations further empowered activists to confront the institutions and agents that had long terrorized them. Tamim, co-founder of the Libyan Emergency Task Force, attested that the Washington, DC-area community spoke out to harass and shame the Libyan ambassador, Ali Aujali, after he refused to side with the revolution in an interview on CNN. After Aujali officially resigned from his post on February 22, protesters entered the DC mission, which was still under the regime’s jurisdiction, and ripped down pictures of Gaddafi, shouting, “Is this a free country or is this Libya?” (Fisher Reference Fisher2011). Exhilarated by this previously unthinkable showing of dissent, participant Rihab recalled that it was about “finally being able to do something and [making] a statement on behalf of the martyrs.” A similar incursion occurred in London on March 16 when demonstrators stormed the embassy and raised the revolutionary flag.

Ten of my respondents reported guarding their identities beyond the first days of the revolution because their family members were trapped in Tripoli or because they were corresponding directly with rebels on the ground.Footnote 3 As Dina from California attested,

During Tunisia, I was tweeting in my own name. When Libya started, the first thing my mom said was change your name on everything, take down any pictures, because my entire extended family is in Tripoli.

Yet, respondents attested that anonymity was relatively rare, and did not hinder their efforts to form new movement groups under the banner of the revolutionary flag. Because the regime proved incapable of making good on its threats at the onset of the revolution, members of the diaspora largely experienced a rapid liberation of their own. The murders of protesters in the early days of Libya’s uprising not only backfired at home, therefore, but also abroad, as the barrier caused by fear of consorting with the “wrong” Libyan largely dissipated.

4.1.2 The Syrian Case: Persistent Fears of Transnational Repression and Guarded Advocacy

In contrast to the swift eruption of a regime-rebel standoff in Libya, Syria’s uprising resembled a “slow motion revolution” (International Crisis Group [ICG] 2011a). Calls on Facebook for a “Day of Rage” on February 4 failed to materialize on the ground, and the regime attempted to stave off protests by implementing a series of concessions, including lifting the bans on YouTube and Facebook.Footnote 4 Yet, many Syrians were aggrieved by years of growing inequality, corruption, and everyday abuse. In light of the new mood induced by Egypt’s Arab Spring, individuals and crowds in Syria began to spontaneously challenge regime officials in ways that were previously unimaginable (ICG 2011a). For example, about a dozen children were arrested by security forces on March 6 for chanting slogans against the regime in the city of Daraʻa. After their families rallied to demand the children’s release, security forces used live ammunition to disperse them. This incident motivated this group to escalate their demands from releasing their children to demanding the end of the regime itself. Other collective displays of dissent emerged in Damascus as well, as when small groups held vigils to support neighboring revolutions. Cell phone videos of protests being harshly dispersed, including one that showed security forces dragging activist Suheir al-Atassi by her hair and throwing her in jail for demonstrating peacefully, affirmed to many observers that Bashar al-Assad was not interested in change.

On March 15, the moment that many regime opponents-in-exile had been waiting for arrived. A small demonstration in the central market of Damascus’ Hamidiya neighborhood was recorded and disseminated to international news channels for the first time, and the territorial scope of the protests expanded shortly thereafter. Assad’s March 30 speech denounced dissenters as traitors and foreign conspirators (ICG 2011b). Attempts by demonstrators to form a Tahrir Square–esque sit-in movement in Homs were brutally crushed by a military siege in late April. During a subsequent siege in Daraʻa, a young teenager named Hamza al-Khateeb was detained by regime forces. On May 25, his corpse was returned to his family displaying evidence of burns, broken bones, and dismemberment. Images of his body circulated on the Internet and were broadcast on Al Jazeera, stoking outrage inside and outside of the country.Footnote 5

As the Syrian army moved to quell protests in Baniyas, Homs, Latakia, Hama, the Damascus suburbs, and other cities in May with lethal force, their brutality provoked defections and increased anti-regime sympathies. As reports circulated about mass detainment, torture, rape, and massacres of entire families by al-Shabiha loyalist militias, the death toll hit approximately one thousand five hundred in July. But even as protests and riots continued through the fall of 2011, the regime retained control over broad swaths of the population and its territory through a range of coercive tactics, including stoking fears of an Islamist-extremist takeover among minorities. The pitting of an Alawite-dominated security force against a Sunni majority and the Kurdish minority stoked further ethno-religious divides on the ground. As the International Crisis Group reported (2011c: 2),

Denied both mobility and control of any symbolically decisive space (notably in the capital, Damascus, and the biggest city, Aleppo), the protest movement failed to reach the critical mass necessary to establish, once and for all, that Assad has lost his legitimacy. Instead, demonstrators doggedly resisted escalating violence on the part of the security services and their civilian proxies in an ever-growing number of hotspots segregated from one another by numerous checkpoints.

As a result of these dynamics, the Syrian revolution unfolded in phases that were distributed unevenly across the country. The uprising was first characterized by pockets of protest and riots that gradually spread to many cities and towns, but it did not constitute a national rebellion until many months later. International condemnation did little to temper the regime’s brutal approach. In December, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights reported the death toll as having reached approximately five thousand; by the end of 2012, that figure would increase at least tenfold.

Syrians in the diaspora went public in their opposition to the Assad regime over the course of 2011 and beyond. This was because the three factors enabling Libyans to wield voice also became operative in the Syrian case: (1) the engulfment of their significant others into the conflict; (2) the embrace of risk-taking and cost-sharing for moral and ethical reasons; and (3) the perceived decline in the regime’s capacity to target individuals abroad. However, the pace at which Syrians went public was staggered because regime control in Syria was largely held in the initial months of the uprising. Correspondingly, regime agents and loyalists continued to threaten activists in the United States, Britain, and other host-countries during the revolution’s first year and beyond.

The threats posed by agents of transnational repression were realized in some cases. For example, after protesters met with the ambassador to Syria in Washington, DC, in mid-April to discuss their grievances, some of their relatives in Syria were detained or disappeared, and others received death threats (Public Broadcasting Service 2012). Additionally, when Syrian artist Malik Jandali performed at a July rally in Washington, DC, in support of the 2011 revolution, regime agents kidnapped his father and beat his mother in Homs, telling her, “We’re going to teach you how to raise your son” (Amnesty International 2011). The brutalization of Jandali’s parents was cited by activists across the United States and Britain as a deterrent to using voice. Media reports also detailed additional instances of Syrians’ relatives being harmed after they spoke out against the regime over the course of the uprisings’ first year (Devi Reference Devi2012; Hastings Reference Hastings2012; Hollersen Reference Hollersen2012; Parvaz Reference Parvaz2011). Batul, a student who later became active in a youth chapter of SAC, explained that these reprisals made her family too fearful to go public in 2011. Her mother told her,

“I understand we all want to voice our opinions. I understand we live in America, it’s a free country. But you’ve got to think of the others. Don’t be selfish. You’re not the one that’s going to face the harm – they are.” That’s why [we were] quiet for a year.

Fears were also heightened by the presence of counter-demonstrators at protest events. Pro-Assad protesters took photographs and video recordings of revolutionary gatherings and verbally threatened individuals in Arabic, as I observed firsthand in Los Angeles in 2012. This marked a notable difference from the Libyan situation. Libyan American activist Dr. Saidi, whose wife is Syrian, attended protests for both causes; he attested that

When I was marching with Syrians in the beginning, we always had people intimidating, taking photos. Sometimes they are on the streets, sometimes they are in a car. [This happened] much less with the Libyans. Much less. Because [although] there were a few pro-Gaddafi, because they saw everyone is against Gaddafi, none of them were willing to stand up or do this intimidation.

These acts of intimidation by pro-Assad Syrians were not always empty gestures. One man named Mohamad Soueid was in fact arrested and convicted of documenting the DC-area opposition with the intent to “undermine, silence, intimidate, and potentially harm persons in the United States and Syria who protested,” according to the indictment (United States of America v. Mohamad Anas Haitham Soueid 2011: 3).

Pervasive regime threats also made my presence at protests suspicious to some participants. In January 2012, a woman observed me jotting down the names of protesters I recognized during a sidewalk rally in Anaheim. She asked in a flat tone, “Why are you writing names?” As I hurried to introduce myself, she remained standoffish and seemed unconvinced. Another woman who was listening to the conversation turned to me and explained in a Syrian accent, “We’re not afraid for ourselves, but for our families.” British Syrians also reported that the presence of outsiders at their events raised serious concerns. Ayman, a doctor who had been living in Manchester since the 1980s, recalled that public events did not start in his city until “late 2011” and that he was “very afraid” to participate because “I have elderly parents in Syria and I don’t want them to be harassed, and we know that people have been.” The counter-mobilization of pro-regime groups meant that just because revolution sympathizers were out demonstrating in public did not mean that they necessarily felt free to be identified as revolution supporters.

These fears led some activists to engage in what I call “guarded advocacy” by covering their faces during protests, posting anonymously online or not at all, and refusing invitations to speak to the media in order to avoid being identified as pro-revolution. Sarab, for example, first helped activists in New York organize from behind the scenes “because I hadn’t gotten approval from my family to be public.” The guarded character of activism also meant that public events took on a semi-private character. For example, despite declarations by a speaker that “the wall of fear has come down!” at a SAC-LA community meeting in December 2011, I was explicitly instructed not to photograph the audience. Persistent concerns about infiltration also led activists who went public early on to be suspected as agents provocateurs. Susan of Southern California, who had gotten permission from her father in Syria to come out, recalled that “people were like, why is she doing this if her family is home? Why is she not scared for them? Reality was, I was scared to death.” In this way, respondents reported that their mobilization efforts suffered from enduring suspicion between conationals. As Rafif from the DC area recalled,

Many people used pseudonyms for a very long time. Other people would sort of mask their faces or something so they wouldn’t be recognized on camera. So people took their pace, whatever they were comfortable with, in terms of coming out publicly in support of the revolution. That also created some mistrust, right? [Because it raised questions as to] why is one guy completely out there and not afraid, and then somebody else is still protecting his identity?

Mistrust in the community also created a challenge for Syrian organizers, because early supporters of the revolution could not get significant numbers of sympathizers in their communities to sign their names on petitions, join organizations like SAC, or affiliate with public calls for regime change. This was a problem because organizers wanted to combat regime propaganda that slandered the revolution as a conspiracy of foreign powers and a terrorist plot. As Said Mujatahid, one of the early SAC organizers, recalled, because of the “phobia in the Syrian community to say anything against the Syrian regime, I would say the first four months was difficult. Even some of your closest people will stay away from you because they are afraid of being associated.” In another example, Belal formed the National Syrian American Expatriate group in Anaheim, which he hoped would bring individuals with varied political views together to support gradual liberalization in Syria. This group of a dozen or so individuals put together a list of requests for Assad, including presidential term limits, in March 2011. However, Belal’s expatriate group was formed in secret out of fears of transnational repression, and Belal was the only member willing to sign his name to the group’s demands.

4.1.3 Syrians’ Gradual Coming Out and Risk-Taking Strategies

Despite the challenges of going public, Syrians reported doing so after regime violence converted their families to the cause or forced their loved ones to flee. Sharif observed this shift among his conationals in Bradford, who began to tell him, “Look, if my family in Syria are going on the street, why do I need to be frightened here in England?” Similarly, Batul was able to “open up” in 2012 after her relatives in Syria decided to make their anti-regime position known and gave “their okay” for their relatives to come out. Washington, DC-based Mohammad al-Abdallah, a political exile whose father was imprisoned by the regime at the onset of the uprising, likewise reported being able to escalate his public criticisms of the regime after his father reached out to condone his son’s activism. He said,

When the uprising started, I was on TV commenting and basically criticizing the government. But I had that concern about my family’s safety because members of my family were in prison. In April, I get a phone call from my father inside the prison. He managed to basically bribe a police officer and use his cell phone. And he called me, [saying] they’re arresting lots of people from the street and bring[ing] them to the prison here, but they tell me they see you on TV and they’re very proud of you. So please continue doing that regardless of what’s happening here.

The victimization of loved ones also compelled respondents to transition from guarded to public advocacy. Nebal, a student in London, emphasized that although an embassy official had contacted him to demand that he attend pro-Assad demonstrations, he felt that he had “no choice” but to go public after his brother was imprisoned. Others did so after experiencing a personal loss. As Abdulaziz Almashi, a founder of the Global Solidarity Movement for Syria, attested,

When I start joining the anti-Assad demonstrations in late April, we used to hide our faces with scarves because we’re not sure about the consequences, we’re worried about loved ones in Syria. In late May, my friend was killed in Hama and I saw the video on Al Jazeera. One week after that, the Syrian embassy again contacted me to ask me to join their protests, and I made my decision. I said “look, I’m not joining you, you are killing our people.” The person said to me, “if you don’t join us, that means you are against us.” I said “I am against you, go to hell!” I was using the megaphone, shouting. They were [taking pictures of] me. And I didn’t care at that time. It was the spark of my activism in the open way.

Respondents also came out after the scope and brutality of regime violence transformed their sense of obligation to encompass the broader national community, rendering nonfamilial Syrians as significant others. Omar, an activist from Houston, recalled, “My brother and family are in Syria, but people were losing their lives. And I don’t think our lives are more precious than those people who lost their lives.” Similarly, Firas of Southern California came out after the regime sent tanks to put down protests in Daraʻa in April 2011. Before this incident, he had covered his face in protests, and

[I tried] to avoid mentioning my name in any petition. But after using the tanks, it was like, no, screw it! Why should I worry about my family when all of the people are getting killed? I know that this regime uses collective punishment. But I was like, I’m not going to care. I’m going to go public.

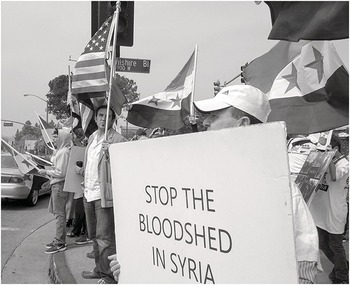

Figure 4.2. Syrians and SAC organizers call for outside powers to “Stop the Bloodshed in Syria” at the Federal Building in Los Angeles, California, on June 9, 2012.

Fadel, a doctor in London, refuted peer pressure not to go public by referencing Syria’s most famous child martyr: “You can’t only be concerned about yourself and your family. If you think Hamza al-Khateeb is not part of your family, I think you are very selfish.” Ahmed of London also attested that he came out after Hamza’s mutilated body was posted on YouTube. “The thing that affected me most was the murder of Hamza al-Khateeb. Before that, I was reluctant to do protests. When that happened, the next day I was protesting outside the embassy.”

The perception that costs should be collectively shared sometimes forced activists to choose between their families and the cause. Muhammad N., exiled to London at the time, described the agonizing decision of whether or not to give a televised interview because his family in Aleppo might be subjected to reprisals. His brother advised him, “This is a duty on every one of us. If all of us are cowards because we have family in Syria, then it’s treason.” Muhammad decided to speak to the media, but the decision pitted his family’s safety against his principles. For other Syrians, the decision to embrace the potential costs of coming out led to familial discord. Fadel in London reported,

I was in a big dispute with my mother. She said, “aren’t you risking yourself?” I said “I’m not, I am safe here.” Then she said, “you have a brother and sister back home.” I said, “Mom, I have to get out of my silence and talk and protest. Those people on the ground, they are brave enough to sacrifice their lives. And I’m sitting here, knowing that nobody is going to shoot at me, and I’m still hesitating? No way. This is the least I can do.”

Some experienced significant social costs for choosing the cause over their familial obligations. When Nour, an independent activist from a Christian family, set up a Facebook page in February 2011 calling for liberty for Syrians, some of his family members in the United States called him very “angry” to say that “if you don’t care about yourself, fine, but we want to go to Syria.” Friends and family abroad and in Syria then began to sever their connections with Nour for fear of “getting in trouble,” and he “started to unfriend a lot of people just to spare them the headache.” Because two of his uncles in Syria were interrogated by security forces about Nour’s social media posts, he published an announcement on Facebook that his family had rejected him. That way, he reasoned, if the regime questioned any of his relatives about him again, they could see that he did not represent their views. “But it wasn’t an easy call,” Nour explained. “I experienced extreme isolation and social stigma. I lost everything, all my social connections.” In a parallel case, Hussam stated that coming out early on as a member of SAC was a strategy “to help others break the fear, the wall of fear. Because it was unusual for people to go public criticizing the regime.” At the same time, “We got a lot of heat. I had family members calling me from Syria like what the heck are you doing? Relatives from all over. All of us went through that, although our [initial] letter [to the regime] was very respectful.” Many participants reported that they had to cut all forms of communication with their families at home so as not to incriminate them by association, which was emotionally trying.

Lastly, activists came out because they perceived that the Assad regime’s increased use of collective and arbitrary violence in Syria meant that going public no longer posed additional risks to their significant others. As L. A. from California explained, such escalations signaled that her family’s fate was no longer in her hands.

Even if I didn’t do anything, if they want my family, they will take them for no reason. When my mom tells me you are [putting a] target on us, I say mama, when they want you, they won’t wait for me to protest or not to protest.

Sabreen also stated that although her mother initially asked her to remain anonymous, she later told Sabreen, “It doesn’t matter if you speak or not, because they are targeting everybody.” As such, members of the diaspora went public because they came to perceive that the regime was no longer willing or able to sanction them in a targeted fashion. As Y. explained,

In the beginning, because everything was so slow in Syria, the regime was able to crack down on everyone who talked. Then it got to a point where they’re not going to keep up. When the conflict escalated militarily, we’re like, okay, their focus is not on Facebook anymore.

This rendered formerly high-risk activism abroad as low-risk, enabling activists to transition from guarded to overt advocacy.

In summary, Syrian anti-regime mobilization in the United States and Britain emerged as never before over the revolution’s first year. As Qayyum (Reference Qayyum2011: 4) writes, this coming-out process cultivated a new consciousness in public space, as Syrians came to “link their names to their stories and opinions as an act of defiance … [and] to rebuff intimidation tactics facilitated by the Syrian government.” However, transnational repression also obstructed diaspora solidarity and mobilization by perpetuating mistrust and fear, and by imposing costs. As Sarab explained, the decision to “cross that line of fear” was belabored.

After I put my first post on Facebook condemning the regime, my finger was trembling and my heart was racing. So it gives you a sense of how repressed and how conditioned we were to be quiet and never express ourselves as long as I’ve been alive.

Furthermore, because many of their family members still resided in Syria, some Syrians chose to only use their first names or to remain partially hidden online or in public.

As numerous members of the anti-regime diaspora began to come out on behalf of the revolution, Syrians attested that the cause lumped and split the community into pro- and anti-regime camps. The fear of being informed upon by fellow conationals also increased polarization within the diaspora. Respondents reported cutting off communications with those who came out on behalf of the regime and avoiding or boycotting businesses known (or believed) to be pro-regime. Though the respondents interviewed in this study affirmed that they would continue to be public regardless of the eventual outcome of the revolution, many knew of others who remain silent or guarded.Footnote 6 Hassan of SAC-LA cited this as a pervasive dilemma for Syrians because “we enjoy freedom and democracy. We came to this country for those things. That fear should not be there. And still, people are afraid.”

4.1.4 The Yemeni Case: Regime Repression’s Effect on Public Mobilization

Protests broke out in Yemen’s capital city of Sanaʻa on January 15, 2011, in support of Tunisia’s revolution, and street-level demonstrations grew steadily each week across the country. Calls by demonstrators known as the “independent youth” for Saleh to step down were intertwined with calls by the legal opposition, including Yemen’s Al-Islah Party and the Yemeni Socialist Party, for reform. After Yemen’s first Day of Rage on February 3, protesters pitched tents at the newly christened Change Square at Sanaʻa University and in Freedom Square in Taʻiz. Regime forces killed several participants in response and spurred a steady growth in protests and sit-ins.

The resignation of Egypt’s president on February 11 escalated Yemen’s uprising. Thousands took to the streets to demonstrate in at least eight cities across different regions of Yemen, including in the restive South and its largest city of Aden. In the North, the regime deployed al-baltajiyya – plainclothes security forces and thug groups – to disperse protests by force. Repression in the South included a series of coordinated attacks, firing on fleeing civilians, preventing doctors and ambulances from reaching injured demonstrators, and disappearing victims (Human Rights Watch 2011a). In the capital and elsewhere, erratic shootings by Saleh’s forces killed about a dozen protesters each week. By the end of February, regime violence prompted Hussein al-Ahmar, a paramount leader of the prominent Hashid tribal confederation, to rally thousands of tribesmen to the cause. He also urged northern Houthi insurgents and southern secessionists to “drop their slogans, adopt a unified motto calling for the fall of the corrupt regime” (ICG 2011d: 5). In February and March, some southern protest factions acquiesced to requests by northerners not to raise the secessionist flag.

In early March, Saleh announced that he would implement reforms while also deporting as many foreign journalists as his enforcers could get their hands on. Soon after, the regime attempted to clear Sanaʻa’s Change Square for good. During a day of protest dubbed the “Friday of Dignity,” or Jumaat al-Karamah, Saleh loyalists shot and killed more than fifty unarmed protesters in the square and injured hundreds (Ishaq Reference Ishaq2012). The massacre backfired, however, by drawing international condemnation and stoking key defections. Saleh’s former ally and commander of the First Armored Division, General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, announced that his unit would defect to protect the protesters. Sadeq al-Ahmar, another prominent figure in the Hashid confederation (and of no relation to Ali Mohsen), also came to side with the revolution. This gave the sit-in movement in Sanaʻa armed protection by Mohsen and his division. At the same time, other protests and sit-in movements across Yemen remained exposed. The regime continued to target them with regularity, leading to dozens of deaths each week.

The Yemeni diaspora did not experience the same degree of threats or fear as their Libyan and Syrian counterparts, as Chapter 3 describes, owing to the regime’s relative weakness and inability to effectively intimidate Saleh’s opponents abroad. Several activists, particularly those from the South, were concerned that they might have trouble returning to Yemen for going public. That said, many of these individuals took that risk out of a sense of moral obligation. Arsalan of Sheffield said that his family worried about potential retribution from the regime, but “I couldn’t stand to stay home and watch TV while my brothers and sisters were being killed back home and not do anything.” Furthermore, unlike their Syrian counterparts, no Yemeni diaspora respondents reported covering their faces at protests or witnessing others doing so, and only one interviewee guarded his identity online.

Respondents reported that regime violence also undermined the sway of the regime over students on state-sponsored scholarships. Hanna, who had been active before 2011 organizing with southern Yemenis in New York, recalled,

In the beginning, a lot of Yemenis, mainly from the North, were pro-Ali Abdullah Saleh. So that was one of our main challenges. [At] the first rally that we had, we had a group come rally against us. And it was mainly people from the embassy, mainly students that the regime was paying for, they said well, we’re paying for your schooling, you have to come out to this rally and support the regime against the other activists. [But] a lot of them, after the killings and after just the tortures and a lot of things that were going on, [those] Yemenis came to our side. So the pro-government rallies started dissipating.

Furthermore, while a core group of activists had already begun mobilizing on behalf of the revolution in February and March, the Friday of Dignity Massacre on March 18 spurred a dramatic spike in protest participation in the diaspora. Adel of Michigan described it as a “turning point” because the killings motivated many who were not previously active or were pro-regime to join their calls for Saleh to step down. Idriss of Washington, DC, recalled, “At that point, there was no going back. Whatever happens, we weren’t going to stick with Saleh anymore.” Respondents attested that they found the footage of the protests appalling. As Ali from the DC-area community described,

Personally, what motivated me most was all those videos I watched on Facebook and on the news. All those young people getting killed by Saleh’s army. I felt like I have to do something. If those people over there are facing the army with guns and everything, the least I can do is support them with my voice.

For Haidar of Birmingham, the massacre also affected him personally. He said,

Initially, Yemenis in the UK were not involved in the revolution heavily, until what happened in March 2011 in [Change] Square, Jumaat al-Karamah. I remember that day, it was – a black day – when we saw the blood of our friends, our colleagues. Some of my best friends were injured in this massacre. Since this day, we started to move.

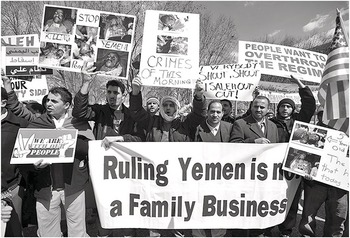

Figure 4.3. Yemeni community members shout slogans against Yemen’s embattled president Ali Abdullah Saleh during a demonstration in front of the White House in Washington, DC, on March 26, 2011. The large banner reads “Ruling Yemen is not a family business.”

Mahmoud of Sheffield described the effect of the massacre as “shocking” in its scale. Referring to another well-known community figure and longtime regime opponent named Abdallah al-Hakimi, he said,

It [became] not only about me or Abdallah calling people and saying, let’s go out. It was amazing how people were calling us to say, look guys, you have to do something, we need to mobilize. I think we had one or two demonstrations beforehand, but they were not as big as after Jumaat al-Karamah. The response of people was very enormous to that.

Morooj also attested that the massacre inspired activists across different US cities to begin working together to launch national days of protest in Washington, DC. She recalled, “After that day, we really began to start working with other cities and start connecting our actions together and [planned] a national day of action in solidarity with Yemenis. So that day definitely was a big turning point. [I]t brought the movement home [to us].” Nadia reported that this event motivated her to galvanize other women in Birmingham to participate in the London-based protests.

The women weren’t involved as much in the organizing for the revolution. They weren’t normally invited. When they killed that many people in one day, that was it for me, I had had it. I felt that it was my children who were getting killed and hurt, [so] I went and booked a coach [to London]. [My husband] said “why did you do that? you haven’t even spoken to the men about it.” I said that “we’re going to fill the coach, even if we fill it with women.” That was the turning point where I was prepared, if anyone was to say to me, “You don’t have the right,” I would say, “Yes I do.” There’s a point where you go past thinking, am I supposed to do, am I not supposed to do. It’s something you have to do, it’s obligatory. So for me, [Jumaat al-Karamah] was the turning point.

As the experiences of activists like Nadia and others illustrate, Yemen’s revolution not only brought diaspora members out in public to protest, but also increased the political participation of Yemeni women as well.

From one of Yemen’s largest concentrated communities in the United States, a community organizer named Adel also observed that the massacre had a counteractive effect on the pro-regime protests in Dearborn, Michigan.

At the beginning, just a few people showed up to a small demonstration. But especially after the Friday of Dignity, lots of people showed up. There were also two demonstrations that were big in numbers that were pro-government. And those were the people who were members of [Saleh’s] Al-Mu’tamar [General People’s Congress] party. They showed up with the president’s pictures. But after that Friday, I don’t think they did anything after that. Some of them kind of joined the revolution and some of them just stayed on their own. And the last [pro-Saleh] one was kind of an embarrassment because only like ten or eleven people showed up to the city hall.

In all, regime repression at home undermined the weak effects of transnational repression in the Yemeni diaspora and, as I explain below, stoked the outrage needed for community members to condemn Ali Abdullah Saleh. As a result, anti-regime activists, both new and old, came together to wield voice as never before.

4.2 The Breakdown (and Resurgence) of Conflict Transmission

4.2.1 The Libyan Revolution and Diaspora Solidarity

In addition to upending transnational repression, the rapid escalation of a zero-sum standoff in Libya also undermined conflict transmission and induced solidarity between conationals for the Arab Spring. As Noueihed and Warren (Reference Noueihed and Warren2012: 180) write,

[Gaddafi’s] now-infamous pledge to go “zanga zanga, dar dar” or from “alley to alley, house to house” to “cleanse” the “rats” and “cockroaches” carried echoes of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, when Hutus described the Tutsis in similarly insect-like terms. Saif al-Islam’s calls for dialogue and a “general assembly” were ignored by both the opposition and the outside world, while his rambling speech threatening “rivers of blood” prompted Western politicians to fall over each other in their rush to distance themselves from Libya’s heir apparent … Even though Gaddafi promised an amnesty to those who gave up their weapons, threats of “no mercy” to those who resisted suggested that a terrible vengeance would be visited upon Libya’s second city [of Benghazi].

Thus, the revolution created shared anti-regime grievances between revolutionaries in exile, reformists who had treated the regime as a bargaining partner in recent years, bystanders who had eschewed home-country politics in the past, and students abroad on state-sponsored scholarships. As a result, regime repression and revolutionary backlash in Libya produced a newfound alignment that paired a “diagnostic frame” attributing the Gaddafi regime as the problem with a “prognostic frame” naming the armed revolutionary movement under the National Transitional Council (NTC) as the only legitimate solution (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Snow and Benford Reference Snow and Benford1988). These conditions motivated mobilization among a wide cross-section of Libyans in the United States and Britain and produced a newfound sense of nationalistic solidarity among conationals. As M., a second-generation exile and member of the Enough Gaddafi! network, explained,

It was incredibly unfortunate, the severity of the crisis, but it left a very clear line for us. There wasn’t any doubt if Gaddafi was doing this or he was not doing this – like in Syria, where there’s a lot of doubt floating around regarding who did what, and what was going on, who’s the good guy or the bad guy. We were lucky enough to have all of that very black and white. The severity of his actions made it very clear. Whether or not [others] had been supportive of Gaddafi before, it changed a lot of people afterwards, not to mention those who had already been affected.

Dina from California also attested to how important Saif al-Islam’s threatening reaction to the uprising was in discrediting the regime. A young professional from Southern California, Dina had spent time working in Libya during Saif’s “liberalization” period before being imprisoned for a brief but terrifying time over government suspicions that she was a spy. She said,

Many people actually, at the beginning of the revolution, did not expect Saif to react in the way that he did. People forget that, but that’s still really an important part of the whole puzzle – the way that he came out so strongly in those first days. His hatred was just so shocking.

Saif’s speech also prompted individuals like Adam, who had engaged with regime representatives through Saif’s diaspora outreach initiative in 2010, to change his mind. He explained his decision in the following way:

If I’m having a debate with somebody and the person decides to slap my sister, the debate is over. I understand we want to limit as much bloodshed as possible. But when you’re fighting a rabid dog, you can’t speak with it, you can’t calm it down with words anymore. That’s it. You’ve got to put it to sleep, end it then and there. The point of return is long gone. And [the regime] passed it.

Abdullah of Enough Gaddafi! also recalled the transformative effect of the revolution in unifying members’ grievances. He reported that during the initial planning meetings for the first protest in Washington, DC, on February 19, he and his fellow organizers debated,

What if people bring [the] green flags [of the regime]? What if people don’t want to see posters that are cursing Gaddafi? There were all these things that we were trying to accommodate so that we’d get as many people to come out as possible. But when the nineteenth came, all of that went out the window. When people were getting killed, people could see the bravery of the youth in the street, and it was all the independence flags, down with Gaddafi! It was just unified all of a sudden.

Niz, a Libyan doctor-turned-revolutionary who was living in Cardiff at the time, also noted that the regime’s use of overwhelming force was critical in legitimizing armed revolution as a necessary method of resistance. He explained,

Very quickly, the realization was that Gaddafi is not Ben Ali or Mubarak. They are all brutal and corrupt dictators, but Gaddafi is a different breed, and public protests at squares – these things were not going to bring the regime down. And that the Gaddafi regime would easily kill 90 percent of the population if it meant him staying in power. They would continue to gun down protesters. And very quickly, the idea came about that this cannot be a mass peaceful protest movement. It needed to become an armed uprising.

For this reason, respondents came to validate the armed struggle by the Free Libya Army (also known as the National Liberation Army) and to back the NTC.

Respondents overwhelmingly reported experiencing a newfound sense of community that brought exiles, refugees, non-activist immigrants, migrants, and even some formerly pro-regime individuals together for the same cause. As Abdo G. of Manchester recalled, “It unified the Libyan community. Because before February 17, the Libyan community in Manchester was in silence. There wasn’t a community.” But after the onset of the revolution, he exclaimed, “People [were meeting] new people. My own brother met his future wife at one of these events!” This sentiment was echoed by activists based in the United States as well. As Khaled recalled, the first Washington, DC, protest on February 19 was

the biggest thing I’ve ever been a part of. Usually when we protest[ed], I would have spent my last dime driving to New York or DC for a protest that had maybe thirteen people. The DC protest was the most Libyans I have seen in one place in America ever. It was [hundreds of] people who had never been politically active, who had never met before.

Osama, who at the time of the revolution was living in Chicago but had grown up among other Libyan families in Tucson, Arizona, echoed that at informal community events, such as “the picnics that happened during the revolution, suddenly everyone [is] singing freedom songs, singing the national anthem – any picnic it would be like that.” The contrast in community relations before and during the Arab Spring could not have been starker.

Of course, neither the revolution itself nor the diaspora’s response was a purely harmonious effort. There were underlying conflicts and mistrust between groups, including violence between anti-regime forces in Libya itself, as well as lingering resentments by long-standing regime opponents of those who had jumped on the anti-regime “bandwagon,” as Ahmed H. recalled. Several members of Enough Gaddafi! who helped to organize the February 19 protest also recalled competition between opposition figures to dominate the event. Ahmed explained that he spoke with the leaders of other groups in order to tell them,

Listen, we just need people to show up. If you want to demonstrate solidarity with the people who are on the front lines going through it right now, [then participate]. That’s the objective more than anything else. We want to present a common front, a unified front, to the world.

Mohamed of Manchester also referenced an underlying “competition” over who would appear in the media. However, despite these wobbles in community cohesion, respondents reported experiencing a sense of solidarity as never before. Mohamed said his experience protesting in Manchester around February 19 “was in and of itself amazing” because

We were rubbing shoulders with everyone. The thing that brought us together was being Libyan and being anti-Gaddafi. I was talking and standing together with socialists, communists, liberals, Islamists, we all had one goal and one pain and we were happy to be together.

Furthermore, despite some tensions, collective action in the diaspora was fundamentally unified around a set of anti-regime grievances and demands. As M. stated, “There was one goal to be achieved. Yes, we all have our differences, but the main goals were to get Gaddafi out, and to stop the killing of people.” Mohamed of Manchester also recalled that Libyans were joined together by the fact that the revolution had escalated immediately into “a fight to the death” – and that despite the disparate groups involved, the revolution-supporting opposition was “united in one fight” against Gaddafi, as Adam from Virginia recounted. As a result, their various strategies to intervene in the revolution itself, described in the next chapter, remained complementary and largely unified for the duration of the fight.

For Libyans, the Arab Spring not only prompted individuals to ally themselves under the banner of the revolutionary flag, but also enabled them convert all known preexisting diaspora groups and organizations in the United States and Britain to the cause (see Table 4.1). This not only empowered individuals to unite in new ways, but also allowed diaspora members to use previously “neutral” or apolitical “indigenous organizations” (McAdam Reference McAdam1999[1982]), that is, community associations and groups formed prior to the revolutions, as spaces for conationals to congregate. In this way, the Arab Spring transformed Libyan organizations into “mobilizing structures” for activism (McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996), providing leaders with a base of support and collective resources for intervention at home. Although the NFSL and other groups formed in the 1970s and 1980s were no longer in operation just before the revolution, many of their participants immediately came to support the struggle. So too did Dr. Abdul Malek, founder of Libya Watch and representative of the Muslim Brotherhood from Manchester. He recalled that he and the Brotherhood came to ally with the revolution because of the regime’s severe response.

When we went to the general meeting, which is the highest authority in the Ikhwan [Brotherhood], we expected something to happen on the seventeenth of February. The argument was over what to expect. Would we expect an outright revolution? Would we expect just some people to come out and then go home, or what? Our position at the end of the day was this: if something happens on the seventeenth, then we will have to wait for the response of the regime. If the regime uses brutal force and kills demonstrators, then we will go out right [away] with the revolution and there will be no going back. But if the regime backs away and allows these young people to vent their energy and their steam without an incident and without killing anyone, then the reform prospects that we are very keen on will continue. But obviously, the regime decided to act brutally against the uprising and started killing right away, and immediately we moved into the revolution mode.

Table 4.1. Libyan groups and organizations converted to the revolution and/or relief during the 2011 Arab Spring, as reported by respondents

| Diaspora Group/Organization | Converted? |

|---|---|

| USA | |

| Enough Gaddafi! | Yes |

| Libyan Association of Southern California | Yes |

| National Conference for the Libyan Oppositiona | Yes |

| Britain | |

| Libyan Muslim Brotherhooda | Yes |

| Libya Watch | Yes |

| Libyan Women’s Union | Yes |

| National Conference for the Libyan Oppositiona | Yes |

a Denotes multinational membership.

The revolution also transformed previously apolitical organizations for empowerment and socialization into politicized groups for the Arab Spring. Dr. Saidi of the Libyan Association of Southern California remarked that “when the revolution started, every Libyan gathering became political.” While attending one of these events in Fountain Valley, California (which convened just a few days after the October 2011 killing of Gaddafi), I observed that the event was entirely revolution-themed: children gleefully swatted at piñatas draped with pictures of the Gaddafi family, and different men gave a series of speeches while wearing the revolution flag like a cape, heralding the triumphs of their compatriots. Participants wore clothing adorned with the revolution flag, ate revolution-flag-colored food, and sang revolution songs, both old and new. British Libyans witnessed this transformation as well. Zakia, founder of the Libyan Women’s Union in Manchester, explained that her organization transformed from a social empowerment group into an activist organization dedicated to intervening in three areas: “one for charity, one for media, one for protests.” As these examples show, diaspora organizations and community events came to be pro-revolution in orientation and mission, giving activists the structural foundation and legitimacy to launch collective actions for rebellion and relief.

4.2.2 The Syrian Revolution and the Diaspora’s Gradual Coming Together

As in the Libyan revolution, the onset of protests in Syria re-energized existing activist networks that had previously opposed the regime. For groups like the Syrian Justice and Development Party in London, the onset of the protests in their home-country presented a welcome opportunity to support and incite resistance. Co-founder Malik al-Abdeh recalled that his group began to play amateur footage of protests in Syria repeatedly on Barada TV to prod Syrians into doing “more of this kind of stuff.” Exiles such as Dr. Radwan Ziadeh and Marah Bukai in Washington, DC, also came out immediately to support the uprising. They used their political connections to meet with US officials on Capitol Hill and speak out in the media. After Suheir al-Atassi was released from prison in Damascus, Marah recalled contacting her friend to affirm that “we’ll do what we can do here to support your aims and targets.”

However, not all activists in exile were comfortable with the prospect of a Libya-style revolutionary war. Ammar Abdulhamid, an activist in exile and co-founder of the Tharwa Foundation, expressed grave concerns about the poor state of rebels’ preparedness. Recalling his thinking at the time, Ammar said, “If people are in the street, I’ll be with them, [and our] Tharwa network is part of it anyway.” Still, he recalled warning other exiles and regime opponents that “we’re not ready,” expressing concerns about the lack of vision and planning on how to overcome the challenges inherent in launching a successful revolution.

The uprising also breathed new life into the Syrian American Council (SAC), but the gradual emergence of the revolution meant that SAC’s reform-oriented stance did not automatically convert into a pro-revolutionary one. Hussam, who helped establish the Los Angeles chapter of SAC and would later became its national chairman, recalled that the council’s first statement on the uprisings was laughably humble in hindsight. He said,

It wasn’t asking for changing of the regime. It was still addressing Bashar al-Assad as the legitimate president – Dear President Assad, basically. We stated support for the demands of the protesters, which at that time were very, very simple. It was very peaceful. It was about political reforms, freedoms, release of political detainees. And the argument behind it was that’s what they’re asking for in Syria. And we can only support what they’re asking for on the street. There’s no need to push the envelope higher than they’re doing. As long as the regime is willing to compromise and come to somewhere in the middle, that’s my insistence. We made it a condition [that] anyone joining SAC or speaking for SAC [had] to abide and be committed to a peaceful revolution, a nonviolent one demanding freedom and democracy and a slow process of change.

This initially put SAC at odds with longtime activists calling for regime change. When Marah Bukai was invited to SAC’s first national meeting in May, she recalled asking them, “‘What is going to be your major statement?’ They said, ‘We want to see some changes in Syria.’ I told them, ‘I’m sorry, you should go and knock on the door of someone else. For me, I want this regime to go.’ So their ceiling was different than my ceiling.”

Just as many Libyans had believed that Gaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam would be the harbinger of reason in the early days of the uprising, many Syrians also held out hope that Bashar al-Assad would do the same. Belal, a Syrian American from Orange County, California, had represented the Syrian expatriate community in dialogues with Syrian regime officials in the past. He explained,

When I met [Assad] face to face and we were talking, you know, he really showed humility and he showed passion. He was very passionate about making change and I believed him. So that’s why I became part of the expatriate [group] that wanted to build a bridge between here and Syria.

However, after sending a letter to the regime and receiving a favorable response, Belal was left waiting in vain as violence on the ground escalated into the summer of 2011 and produced over one thousand casualties.

Once the regime escalated its retaliatory response to protests by laying siege to entire cities and towns, reformist groups mirrored calls for the fall of the regime that were spreading across Syria. Hussam of SAC recalled, “After the regime showed that they had absolutely no interest in reforming or changing their ways, that’s when I said dialogue cannot work.” In an evolution of SAC’s position, he explained why the organization transitioned from supporting a peaceful revolution to armed resistance:

Initially, most people truly believed the nonviolent path was the only path. It started changing, [but] the change didn’t happen overnight. That transition first included: what do you do with soldiers who defect? These people are being tracked down by the government and killed, and their wives were being raped and their parents were being shot. So there was a debate, can they defend themselves and their own families and villages? The first transition was yes, they have the right, actually they have the responsibility to refuse these orders. And when they go in hiding, if the government is pursuing them, they have the right to defend themselves and their families. And the next phase became, what about these soldiers defending their whole village, their whole town, or their neighborhood? Because the regime is coming to practice collective punishment on the cities. Can they defend their own villages and neighborhoods? The answer was yes. And then the next question becomes, what if a young man joins them because there weren’t enough defecting soldiers to defend the village? What if a young man says, I will join you? Yes. And that transition eventually became, what if we [the revolutionaries] raid [government forces] before they raid us? What if we go and raid a Syrian army base and take the weapons so that they don’t use them against us? Yeah, that sounds good, too.

He added, wryly, “I know from here, it sounds great to be Gandhi.” Yet, because regime forces and militia known as al-Shabiha were hunting down pacifists and defectors, this left the opposition with no choice but to fight back. Belal, despite having initiated dialogue with the regime in the past, also came to side with the revolution by the end of the summer. He said,

When people rise up for a change, you should accept that. I learned that here [in the United States]. People were going out in their bare chest, they’re resisting, they’re asking for change. And they were met with weapons, machine guns, and attacked. Basically they were paying the price with their life. Even we supported that they carry arms because they were getting killed and slaughtered.

As violence worsened significantly over the course of 2012, activists reported that many members in their respective communities came to sympathize with the uprising within a year of its onset. Sabreen, a youth activist from Southern California, reported that different events, including a slew of massacres occurring in people’s hometowns and cities, “hit different people at different points. So there wasn’t one specific event. [But] you can’t really go back on all those massacres, you can’t go back on all those deaths. And you can’t just accept the regime after all that.” The escalation of the conflict over the course of 2011 gradually brought different politicized factions into alignment with the view that the regime must fall.

As a result, Syrians converted many preexisting organizations to the Arab Spring (see Table 4.2). Groups such as the Syrian American Council, which lay relatively dormant since its founding in 2005 due to the threat of transnational repression (see Chapter 3), and elite-led organizations like Ammar Abdulhamid’s Tharwa Foundation and Dr. Radwan Ziadeh’s Center for Political and Strategic Studies, immediately converted their groups to the Arab Spring. Activists also converted professional service organizations, previously perceived by respondents as co-opted by regime elites, to the cause of relief. The two medical associations that operated in the US and British diasporas before the revolution – the Syrian British Medical Society and the Syrian American Medical Society, both founded in 2007 – came to channel their resources to the conflict after pro-revolution humanitarians and activists mobilized to liberate these organizations from regime loyalist control.

Table 4.2. Syrian groups and organizations converted to the revolution and relief during the Arab Spring (2011–14), as reported by respondents

| Diaspora Group/Organization | Converted to the Rebellion and/or Relief? |

|---|---|

| USA | |

| All4Syria | Yes |

| Syrian American Association (Southern CA) | No |

| Syrian American Club of Houston | No |

| Syrian American Council | Yes |

| Syrian American Medical Societya | Yes |

| Syrian Center for Political & Strategic Studies | Yes |

| Tharwa Foundation | Yes |

| Britain | |

| Syrian British Medical Societya | Yes |

| Syrian Justice & Development Party | Yes |

| British Syrian Society (London) | No |

| Syrian Observatory for Human Rights | Yes |

a Denotes an exclusively charitable/service nonprofit organization.