Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by emotional dysregulation,Reference Carpenter and Trull 1 interpersonal relationship problems,Reference Howard, Lazarus and Cheavens 2 anger,Reference Martino, Caselli and Berardi 3 and impulsive and risk-taking behaviors such as suicide and substance use problems.Reference Brune 4 It is often a chronic mental health disorder that may have profound negative impacts on individuals’ psychosocial functioning,Reference Bagge, Nickell and Stepp 5 –Reference Euler, Nolte and Constantinou 7 and can lead to a severe burden on family members of these individuals.Reference Hoffman, Fruzzetti and Buteau 8 The estimated prevalence of the disorder is between 0.5% and 5.9% in the general population from worldwide studies.Reference Arens, Stopsack and Spitzer 9 –Reference Ellison, Rosenstein and Morgan 12

Although it has long been proposed that BPD has disorganizing effects on cognition and memory,Reference Fertuck, Lenzenweger and Clarkin 13 surprisingly little research has examined cognition in BPD patients compared with nonaffected individuals. Nonspecific deficits in working memory and executive dysfunction have been reported in BPD groups compared with some other psychiatric and nonclinical groups.Reference Fertuck, Lenzenweger and Clarkin 13 –Reference Gvirts, Harari and Braw 15 On the contrary, some studies have found little or no evidence of cognitive dysfunction (executive functioning and working memory) in BPD.Reference Sprock, Rader and Kendall 16 –Reference Linhartova, Latalova and Bartecek 18 Clinical implications of cognitive dysfunction in BPD have been highlighted in previous reviews.Reference Baer, Peters and Eisenlohr-Moul 19 , Reference McClure, Hawes and Dadds 20 Eijk et al.Reference van Eijk, Sebastian and Krause-Utz 21 conducted research on response inhibition in two separate groups of unmedicated women with BPD without co-occurring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They found that patients with BPD had higher levels of impulsivity (on the BIS-11 and on subscales of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale) compared with healthy controls, but there were no differences in response inhibition as measured by the Go/nogo and Stop Signal tasks.

Impulsivity is regarded as a key hallmark of BPDReference Kenezloi, Balogh and Fazekas 22 , Reference Chamorro, Bernardi and Potenza 23 and is implicated across a range of disorders such as ADHD and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) but may be particularly pertinent to BPD given the nature of the symptoms and prior work suggesting correlations with symptom severity in BPD.Reference Linhartova, Latalova and Bartecek 18 , Reference Martin, Graziani and Del-Monte 24 –Reference Black, Blum and Allen 26 Impulsivity in BPD has been linked to cognitive impairments, including set-shifting deficits, which refer to the ability to switch between tasks or mental sets. Impairment in set-shifting is considered another hallmark of BPD and has been associated with increased impulsiveness, emotional dysregulation, and difficulties in forming and maintaining stable relationships.Reference Turner, Sebastian and Tuscher27 Studies have shown that individuals with BPD exhibit impairments in a range of cognitive processes, including attention, memory, and executive functions, which are thought to underlie their impulsivity and emotional dysregulation.Reference Gagnon28 Despite this, there is still a great deal of uncertainty about the precise relationships between impulsivity, cognitive impairments, and BPD. This highlights the need for further research to fully understand the underlying mechanisms and to develop effective treatments for this debilitating disorder. Impulsivity could also play a mediating role in an increased risk of non-suicidal self-injury and suicidalityReference Brodsky, Malone and Ellis29–Reference Black, Blum and Pfohl32 and substance use problemsReference Brune4 in BPD. Research suggests that increased impulsivity may also be a risk factor for criminal behaviors in BPD.Reference Karsten33

Considering the personal and societal negative consequences of BPD,Reference Brodsky, Malone and Ellis 29 –Reference Chamberlain, Redden and Grant 31 , Reference Karsten 33 more multidisciplinary research aiming at investigating the relationship between impulsivity and cognitive functioning is needed to generate a better understanding of the etiology and longitudinal course of BPD. The aim of this study was to evaluate cognitive functions in individuals with BPD and to compare them to controls. It was hypothesized that BPD would be associated with cognitive impairments. In addition, the study aimed to examine the relationship between trait impulsivity and symptom severity in BPD. It was hypothesized that individuals with BPD would display high levels of trait impulsivity and that this would be positively correlated with symptom severity in the clinical group.

Methods

Participants

Adults with BPD were recruited as part of a clinical trial for BPD.Reference Grant, Valle and Chesivoir 34 The diagnosis of BPD was made using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria and a validated diagnostic tool.Reference Grant, Valle and Chesivoir 34 Neurocognitive testing was conducted before participants received study medication, as part of the baseline assessment, and the cognitive data have not been reported previously. Healthy controls were recruited from a study of impulsivity in young adults. Both groups were recruited for their respective studies using online advertisements, and neurocognitive testing was conducted using the same procedures in the same testing suite. Inclusion criteria for those with BPD were as follows: primary diagnosis of BPD; a ZAN-BPD scale total score of at least 9; and the ability to understand and sign the consent form. Exclusion criteria were: unstable medical illness; schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder; an active (i.e., last 12 months) substance use disorder; suicide attempt within the last 6 months; illicit substance use based on urine toxicology screening (excluding marijuana); and initiation of psychological interventions or use of any new psychotropic medication within the last 3 months.

Participants were recruited in the study from the June 1, 2018 until December 16, 2020. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. After a comprehensive explanation of study procedures and an opportunity to ask any questions, all participants provided written informed consent. In total 84 adults were enrolled for this study, 26 of whom were people diagnosed with BPD and 58 were healthy controls.

Assessments

Demographics including sex, race (asked with a single question regarding how the person self-identified), education and age at time of study enrolment were collected for all participants. We assessed cognitive functions using validated computerized tests from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB). The tests used were Intra/Extra-Dimensional Set Shift (IED) task and One Touch Stockings of Cambridge (OTS) task. We focused on these two domains due to prior reports of executive function difficulties in BPD, as well as the repetitive symptoms often seen in BPD in terms of self-injury, which may suggest difficulties in flexibly adapting behavior. The Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) and the Self-Report Version of ZAN-BPD were used to assess the symptom severity of BPD and impulsivity was measured using Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11).

Intra/extra-dimensional set shift task

The IED task is a part of CANTAB and is a computerized version developed from the earlier Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. IED is a commonly used test that aims to investigate the ability of individuals to flexibly shift their attention and make appropriate responses based on changes in task demands/rules. This task requires participants to attend to different dimensions of a visual stimulus, such as color or shape, and make a decision accordingly. Participants are presented with a series of trials in which the target dimension changes and they must shift their attention to respond accurately. The task is particularly useful for investigating the neural underpinnings of cognitive flexibility and the role of the prefrontal cortex in attentional control. It has nine stages to be completed. On each trial, individuals select the correct stimulus on a screen and after six consecutive correct responses, the rules change, and individuals move on to the next stage. The key outcome measures of interest were: total errors adjusted (since subjects who fail at any stage of the task have less opportunity to make mistakes, their score is adjusted by adding 25 for each stage not attempted due to failure); total Extra-Dimensional shift (ED) errors (this is the crucial cognitive flexibility stage [Stage 8] where individuals need to inhibit and shift attentional focus); and the total number of stages passed. Further information on the task can be found at www.camcog.com, including access to a bibliography of prior publications using the task.

One-touch stockings of Cambridge task

The OTS is also a part of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) and is used to assess executive goal-directed planning. It measures an individual’s ability to plan and execute a task efficiently. Participants are presented with two sets of colored balls on-screen, arranged in three stacks, and they are asked to determine the minimum number of moves required to rearrange one set of balls to match the appearance of the other set of balls. The task is analogous to the classic ‘Tower of Hanoi’ paradigm. Individuals indicate their estimated minimum number of moves necessary to complete a given trial by selecting the corresponding number button on the screen. Thus, the individual has to mentally work through how to solve each problem using the fewest possible number of ball movements, and then select the corresponding minimum number of moves on the screen. Key outcome of the measure was the number of correctly solved problems on the first attempt. Further information on the task can be found at www.camcog.com, including access to a bibliography of prior publications using the task.

Zanarini rating scale for borderline personality disorder

This is a widely used valid and reliable behaviorally anchored rating scale (also known as BARS) which is used to measure symptom severity of BPD.Reference Guo, Li and Crawford 35 , Reference Zanarini 36 The scale was developed based on the borderline module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) and is comprised of nine items scored between 0–4 yielding a total score of 0 to 36.

Self-report version of ZAN-BPD

Although we expected clinician-administered and self-report scales to be largely similar, there is the chance that people may be more open with an examiner or others may be more open if they answer the questions without talking to someone directly. Therefore, we also included an adapted self-report version of the ZAN-BPD. This self-report version of ZAN-BPD is a modified version of the original clinician-administered ZAN-BPD scale aiming to assess the change in the severity of BPD psychopathology over time. Like the clinician-administered ZAN-BPD, this self-report version of the Zanarini Scale also has a five-level set of anchored rating points for nine items. The scale is reported to have good convergent validity with the original scale, and good internal consistency, and test–re-test reliability.Reference Zanarini, Weingeroff and Frankenburg 37

Barratt impulsivity scale, version 11

The BIS-11 is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 30 items that are used to assess the level of impulsiveness in individuals. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “Rarely/Never” to “Almost Always/Always”. The higher the score, the greater the level of impulsiveness. To avoid response biases, some items are scored in reverse order. The total score is calculated by summing the individual item scores, providing a measure of the overall level of impulsiveness.Reference Patton, Stanford and Barratt 38 , Reference Barratt 39

Data analysis

Subjects were comprised of two groups: BPD and controls. The two groups were compared in terms of the cognitive measures of interest. All between-group comparisons were undertaken using t-test and chi-square statistics as appropriate. Correlation analyses were carried out using Spearman’s rho to examine relationships between BPD symptom severity and impulsivity and cognitive performances in the BPD group. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05 uncorrected. All analyses were conducted using JMP Pro software.

Results

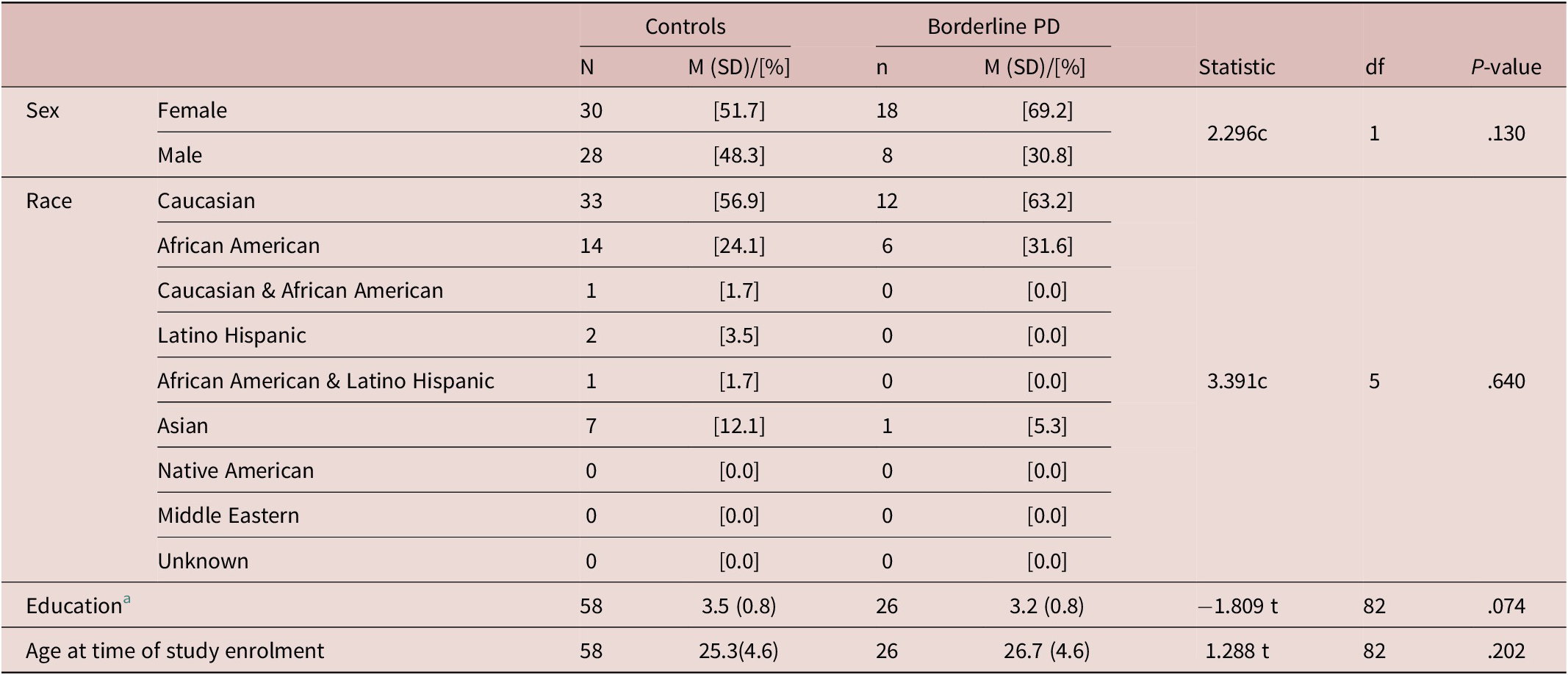

The sample comprised 84 participants which consist of 26 patients diagnosed with BPD and 58 controls. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the groups. According to the t-test and chi-square statistics, the groups did not differ significantly in terms of sex, race, education, and age at the time of study enrolment distributions.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics

Note. Statistic: c, Chi-square; t, t-test.

a 1 = <H.S. (High School) 2 = H.S. Grad./GED (General Equivalency Diploma) 3 = Some College 4 = College Grad. 5 = College+.

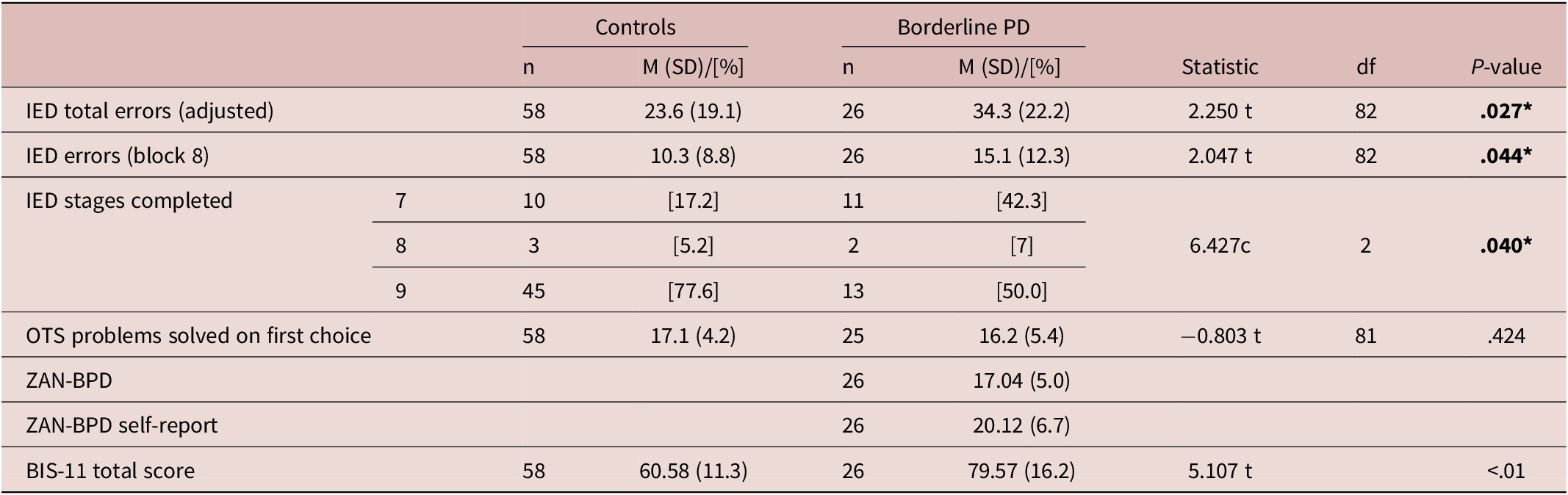

In the clinical group, the mean ZAN-BPD score was 17.04(5.0) and the mean self-report score was 20.12(6.7), indicative of typical moderate severity of illness. In terms of impulsivity, the mean BIS-11 total score for the BPD group was 79.57(16.2) and for the healthy controls was 60.58(11.3), this being a statistically significant difference (t = 5.107, P < .01).

Cognitive tests and other clinical variables are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that the BPD group was impaired relative to controls on IED total errors (adjusted), IED errors (block 8), and IED stages completed. Both BPD and control groups passed the task stages (1) simple discrimination, (2) simple reversal, (3) compound reversal, (4) compound discrimination, (5) compound reversal, (6) ID shift, and (7) ID reversal. The proportion of participants passing the ED stage (8) was significantly lower in the BPD participants compared to controls (Likelihood Ratio Chi-square = 5.72, P = .0168). Collectively this suggests a selective impairment in ED-shifting in the BPD group versus controls; i.e., a relative impairment in the ability to inhibit and shift attentional focus, which is the key component of cognitive flexibility as indexed by the task. Individuals with BPD did not significantly differ from healthy controls on OTS problems solved on the first choice (Table 2); this task reflects executive visuospatial planning and working memory.

Table 2. Cognitive Tests and Clinical Variables

Note. Statistic: c = Chi-square; t = t test. Bold P-value indicates significance at <.05 with effect size.

Abbreviations: IED, intra-extra dimensional set shift; OTS, one touch stockings of Cambridge.

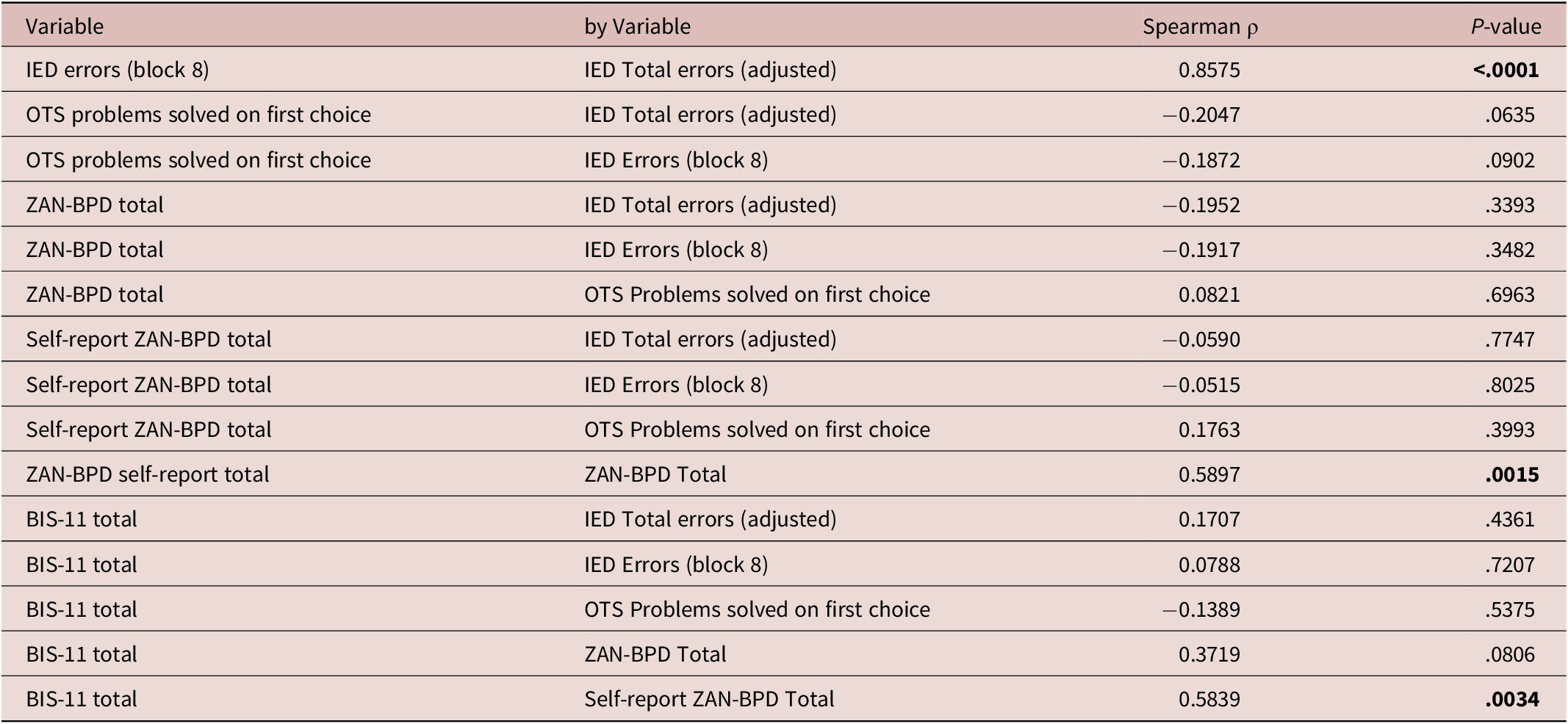

Significant positive correlations were found between symptom severity (clinician-administered ZAN-BPD) and impulsivity (BIS-11) in BPD patients (ZAN-BPD Total scores; Spearman’s rho = 0.58, P = .003) while cognitive functioning did not correlate significantly with BPD symptom severity for ZAN-BPD (IED total errors Spearman’s rho = −0.20, P = .34; OTS Spearman’s rho = 0.08, P = .70), and for self-report ZAN-BPD (IED total errors Spearman’s rho = −0.06, P = .77; OTS Spearman’s rho = 0.18, P = .40). (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations

Abbreviations: BIS-11, Barratt impulsivity scale, version 11; IED, intra-extra dimensional set shift; OTS, one touch stockings of Cambridge; ZAN-BPD, Zanarini rating scale for borderline personality disorder.

Discussion

This study examined trait impulsivity and two cognitive domains in people with BPD versus controls: set-shifting and executive planning. The key findings were that BPD was associated with impairment on set-shifting and elevated trait impulsivity. The finding of set-shifting impairment in BPD may have important clinical implications: set-shifting refers to the ability to switch between tasks or mental sets and is thought to be linked to the function of the dorsolateral frontal cortex, as well as the anterior cingulate cortex. It is believed that a reduced functioning of the action-monitoring network in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) leads to difficulties in learning from errors, which in turn contributes to the impulsive behavior and lack of behavioral adjustment seen in individuals with BPD.Reference de Bruijn, Grootens and Verkes 40 Impairment in set-shifting is regarded by some as a hallmark of BPD and is associated with a range of negative outcomes, including impulsiveness, emotional dysregulation, and difficulties in interpersonal relationships.Reference de Bruijn, Grootens and Verkes 40 , Reference Schulze, Schmahl and Niedtfeld 41 Clinically, the set-shifting impairment in BPD may contribute to difficulties in adapting to new situations, rigid thinking patterns, and an inability to change maladaptive behaviors. This may contribute to increased impulsivity, difficulty in regulating emotions, and difficulties in forming and maintaining stable relationships. Reference Turner, Sebastian and Tuscher27, Reference de Bruijn, Grootens and Verkes 40 , Reference Schulze, Schmahl and Niedtfeld 41 In this study, only trait impulsivity had a significant correlation with symptom severity in BPD. However, we did not detect any significant differences between the groups on the OTS task which assesses spatial planning, and (to some degree) working memory. This finding is somewhat consistent with the existing literature as Sprock and colleagues’ study on memory and cognitive functions did not find a significant difference between BPD patients and control groups in terms of memory tasks.Reference Sprock, Rader and Kendall 16

On the other hand, Hagenhoff et al.Reference Hagenhoff, Franzen and Koppe 14 reported impairment in working memory and no impairment in response inhibition in BPD group compared to controls. Similarly, a study focusing on executive functioning (cognitive planning, sustained attention, and spatial working memory) in BPD patients and their relatives found that BPD patients showed a significant impairment only in cognitive planning.Reference Gvirts, Harari and Braw 15 However as mentioned earlier, existing literature is divergent in terms of cognitive dysfunction in BPD population. Some studies suggest BPD patients demonstrate no indications of cognitive dysfunction (executive functioning and working memory).Reference Kunert, Druecke and Sass 17 , Reference Linhartova, Latalova and Bartecek 18 An explanation for the divergent findings could be that there is considerable heterogeneity in the BPD group profiles since confounders such as comorbidities, age, and therapy/medication status might have played a role in the findings of these studies.

We did not find any significant correlations between BPD symptom severity assessed by both self-report and clinician-administered ZAN-BPD scales, and cognitive functions assessed by the CANTAB-IED and OTS tasks. This result may indicate that although individuals with BPD seem to have poorer performance in cognitive tasks, symptom severity itself may not play a role in this difference. One interpretation is that this deficit may constitute a candidate vulnerability marker that precedes symptoms, as has been found in other conditions associated with repetitive behaviors such as OCD. Therefore, future research should use a longitudinal approach to enhance our understanding of causal relationships between BPD and cognitive functioning.

Barratt impulsivity scores differed significantly between BPD and control groups, as expected, due to higher levels of trait impulsivity in the former. Additional analyses suggested a significant medium-effect size correlation between impulsivity and BPD symptom severity. This result is consistent with the literature as impulsivity is one of the core symptoms of BPD.Reference Linhartova, Latalova and Bartecek 18 , Reference Kenezloi, Balogh and Fazekas 22 –Reference Martin, Graziani and Del-Monte 24 This result may suggest that people with high trait impulsivity are more likely to have increased symptom severity. It is interesting to note that a previous study examined the factor structure of BPD symptoms and found a ‘high severity’ subtype, which was associated with high impulsivity.Reference Black, Blum and Allen 26 This prior finding is aligned with the current results. GagnonReference Gagnon 28 reviewed the literature on impulsivity in BPD and emphasized the importance of considering impulsivity as a multidimensional construct that encompasses both behavioral and cognitive aspects. Impulsive behavior in BPD can be seen as an expression of underlying cognitive impairments, such as difficulties with impulse control and decision-making. Again, this is important as it suggests longitudinal work could now shed light on mechanistic directions of effect, now that a correlation has been established.

While this study was conducted in a neglected research area, several potential limitations should be considered. One limitation of this study (and others in the field) is the lack of a gold standard tool to assess both cognitive functioning and trait impulsivity in individuals with BPD. This makes it challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the nature and extent of cognitive impairments in this population. Additionally, it is important to note that these results are only preliminary and further research is needed to confirm and expand upon these findings. It would be valuable to conduct larger, more comprehensive studies with larger samples and more diverse populations to better understand the relationship between cognitive impairments and impulsivity in BPD. Comorbidities are common in people with BPD and this study was neither designed nor powered to assess any contribution of comorbidities to the cognitive profile identified. The study was neither designed nor powered to address the impact of psychoactive medications on cognition in BPD: to address this would require much larger future studies. Lastly, we used total scores on the BIS-11 rather than using factor scores. Our rationale for this decision was that prior work has indicated that factor models of the BIS-11 (i.e., the three-factor model) may be psychometrically unstable.Reference Vasconcelos, Malloy-Diniz and Correa 42 , Reference Hook, Grant and Ioannidis 43

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study identified impaired set-shifting but intact executive planning in people with BPD versus matched controls. Higher impulsivity (on the BIS questionnaire) was correlated with worse symptom severity. Future work should use a longitudinal approach to enhance our understanding of causal relationships between BPD and cognitive functioning.

Financial Support

Prof Chamberlain’s time on this study was supported in part by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Fellowship (110 049/Z/15/Z).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.E.G.; Funding acquisition: S.R.C.; Project administration: I.H.A.; Resources: J.E.G.; Supervision: J.E.G., S.R.C.; Writing—original draft: I.H.A.; Writing—review and editing: J.E.G., S.R.C.

Disclosures

Prof Grant has received research grants from TLC Foundation for BFRBs, and Avenir and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. Prof Grant receives yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for acting as Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies and has received royalties from Oxford University Press, American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Norton Press, and McGraw Hill. Prof Chamberlain receives research funding from Wellcome and the NHS, UK. Prof Chamberlain receives a stipend for his work as Associate Editor at Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews; and at Comprehensive Psychiatry. Dr. Aslan reports no disclosures.