The machine was a dominant trope of interwar modernism. As a compelling, if often amorphous, symbol of the present, it proliferated freely across different locations and art forms: from Berlin to Mexico City and Tokyo, from avant-garde poems to architectural drawings and cabaret revues. In the concert hall, one product of the machine vogue was a new sub-genre: compositions that used traditional orchestral instruments to depict the noisy technologies of production and transportation characteristic of early twentieth-century industrialism. Arthur Honegger's Pacific 231 (1923), named after a class of high-speed locomotive, remains probably the best-known example.Footnote 1 Such works have long captured the imagination of musicologists, partly because they raise, in a distinctive guise, fundamental questions about the nature of musical representation and partly because they offer enticing opportunities to draw connections with the historiography of modernism in other disciplines. The resulting scholarship has explained the appeal of industrial technologies to composers in search of post-Romantic modes of expression, highlighting affinities with broader artistic movements such as Futurism and New Objectivity, and shown how ideas and techniques associated with machine aesthetics in other media were translated into musical conventions.Footnote 2

As such research has demonstrated, at least implicitly, the early twentieth-century machine aesthetic was impressively mobile. It had an exceptional capacity to traverse national frontiers and other apparently fixed cultural boundaries. In music, there is perhaps no better example of this tendency towards expansive, unruly circulation than a short orchestral work by the Soviet composer Aleksandr Vasil′yevich Mosolov (1900–73): Zavod: muzïka mashin (‘Factory: The Music of Machines’, 1927), usually known outside Russia as the Iron Foundry. Insofar as the prominence of machines in early Soviet modernism across the arts registered a broader preoccupation with ‘Americanism’ – and, in particular, with the functional and aesthetic qualities of Fordist practices of mass production – Mosolov's choice to write a piece of music about a factory had been catalyzed by a rich seam of cultural mobility.Footnote 3 But what makes the Iron Foundry truly remarkable as a transnational historical phenomenon is its life outside the Soviet Union. Although Mosolov is an obscure figure today, his name was once much more widely known. From 1930, his machine-inspired composition followed in the tracks, so to speak, of Pacific 231, and became hugely popular across Europe, North America, and beyond. While its fame lasted, few other works of contemporary orchestral music enjoyed such widespread interest and acclaim.

This article sets out to follow the Iron Foundry on its circuitous routes in the 1930s. The work's success was the outcome of an explosively productive convergence of institutional structures, modes of listening, and compositional idiom. Tracking the interplay between these factors, I ask why Mosolov's machine aesthetic appealed so powerfully to audiences and how it lent itself to widespread circulation. Reassembling the fragmented archives of its performance and reception histories, across an expansive geographical scope, reveals how the work became a lightning rod for larger debates about concert music's relationships with modernity, politics, and mass entertainment. Extricated from more panoramic narratives about noise in twentieth-century music and sound art, on the one hand,Footnote 4 and specialist studies of Soviet music, on the other,Footnote 5 the Iron Foundry has much to teach us not only about the interwar machine aesthetic and its distinctive pleasures, but also about how the many listeners and critics who encountered it understood the forms and functions of culture in a machine age.

Wherever it went, the Iron Foundry posed the same basic dilemma: how to interpret the spectacle of a symphony orchestra imitating industrial machines. This quasi-programmatic gambit ostensibly established a straightforward stance towards modernity: ‘music that expresses contemporary life’, as one critic had it.Footnote 6 Yet in practice its meaning proved contentious and surprisingly difficult to pin down. The Iron Foundry transformed the orchestra into a factory, but not one that actually produced material commodities; mimetic similitude bridged the difference between a musical ensemble and heavy machinery, but did not erase it. For listeners, this play of presence and absence generated several layers of paradox. After a brief survey of the work's sudden ascent to world renown, I draw out the underlying logics and stakes by moving through a series of unstable binary oppositions in a sequence of increasing complexity and scope: the ultra-modern and the primitive, the particular and the universal, artistic creation and mechanical reproduction, modernism and mass entertainment.Footnote 7 Finally, I shift to a more diachronic perspective to consider the Iron Foundry's fading appeal at the end of the 1930s, when the larger paradigm of machine aesthetics to which the work belonged started to break down.

Throughout, I will be particularly concerned with the status of machine aesthetics as an international idiom – and, more than this, as an idiom of internationalism. My claim is not simply that machine aesthetics was ‘transnational’, which is to say, that it was carried and transformed through networks and patterns of circulation exceeding the bounds of any one nation or state.Footnote 8 It is, rather, that through the combination of its subject matter and its capacity to generate, or make visible, transnational mobilities and entanglements, machine-inspired art and culture invoked and helped to sustain larger narratives about technology's contribution to international politics. The word ‘internationalism’ is thus pertinent here not so much as a category of institutions or other collective projects, but as a shorthand for a broader (and more diffuse) set of attitudes and assumptions about geopolitics and the path of world history.Footnote 9

The Iron Foundry's origins in Moscow are clearly significant here. After 1917, the Soviet Union became the new centre of gravity for a vibrant tradition of internationalist thought and activism on the Left – a tradition in which industrial technologies, and factories in particular, played a foundational role (as actual and emblematic sites of the exploitation of the urban proletariat, on the one hand, and of the development of class consciousness and alternative political economies, on the other). The Iron Foundry always remained to a significant degree associated with politics of this kind, even if the meanings attributed to the association were often ambiguous or seemingly contradictory.

Yet that was not the whole story, or perhaps even the main one. In the quintessentially ‘bourgeois’ concert culture of the capitalist West, where the Iron Foundry enjoyed much greater success than within the Soviet Union, the basic values and discourses of liberal internationalism were normative. Although this intellectual and political tradition was fundamentally opposed to the internationalisms of the Left, the two camps nonetheless shared some important preoccupations and enthusiasms, one of which was the transformative potential of modern technology.Footnote 10 No less than their socialist and communist counterparts, early twentieth-century liberal internationalists depicted their cause as the inevitable future outcome of an unfolding trajectory of social evolution. Modernity, they argued, had enabled the formation of larger and larger human collectives: just as the national community had become a lived reality, an international community would surely emerge.Footnote 11 New technologies, such as the telegraph and the aeroplane, were usually presented as the primary drivers of this process.Footnote 12 The teleological thrust (and hubris) of such thinking is exemplified by Henry Ford's utopian prediction in 1928 that the development of machinery would ultimately engender a global polity: the United States of the World.Footnote 13 For others, of course, such a scenario implied the brutal erasure of national traditions, belonging, and sovereignty: an extension, at the level of geopolitics, of the modern machine's nightmarish potential to induce alienation and conformity.Footnote 14

Anxieties of this kind were not entirely unjustified. For all the talk of mutually beneficial cooperation, power and prestige were decisive factors in how internationalist schemes and institutions came to be directed, and for whose benefit. The history of liberal internationalism in the twentieth century was profoundly imbricated with that of imperialism – to the point where it is almost impossible to say where one ends and the other begins.Footnote 15 At the same time, and without underestimating the strength and significance of that connection, we should also be cautious of reducing the complex and sprawling histories of internationalism and machine aesthetics to a single master narrative of domination. One risk of doing so would be to lose sight of the sheer enjoyment that audiences gained from artworks and performances such as the Iron Foundry. For certain groups, and for better or worse, encountering machines in music and other media was above all fun.

In this very collision, or synthesis, of the whimsical and the serious, the case of the Iron Foundry illustrates how the pleasures of machine aesthetics – and, more specifically, a stylized idiom of mechanized gesture distinctive to the period – became widely assimilated into what we might call the vernacular internationalism of the interwar middle classes. ‘Vernacular’ here is inspired by the film scholar Miriam Hansen's use of the term as one that ‘combines the dimension of the quotidian, of everyday usage, with connotations of discourse, idiom, and dialect, with circulation, promiscuity, and translatability’.Footnote 16 Attending to the intensive dissemination of the Iron Foundry in the 1930s as a vernacular phenomenon in all these respects, I aim to excavate the aesthetic and sensory dimensions of a mode of belonging to the modern world that was distinct from, but also buttressed and intersected with, that of the elite individuals and institutions which have tended to predominate in the study of cultural and political internationalism.Footnote 17 For a defined period, I suggest, Mosolov's modernist aesthetic met a particular kind of popular hunger for ‘international’ experiences: one that was inextricable from a fascination with mechanicity and its effects on the human body.

Networks and trajectories

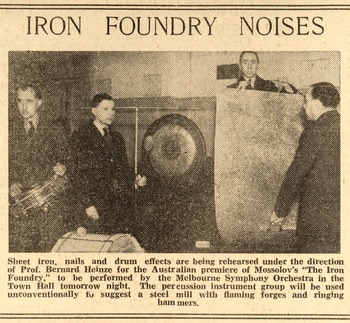

On first listen, the Iron Foundry might not seem an obvious candidate for popular success. The work begins with an array of ostinato cells: a snaking chromatic figure in the clarinets and violas is set against groaning basses, tuba, and contrabassoon, and pounding tritone crotchets in the timpani. Further repeated motifs are gradually added, building a texture of increasing complexity, dissonance, and clamour. This dense mesh of recurrent patterns provides the backdrop for two devices of orchestration often commented on in the 1930s. The first is the blazing entry of the horns, which marks the climax of the opening section's process of accumulation: entrusted with a relatively expansive quasi-modal theme, in contrast to the churning chromatic activity around them, they are instructed not only to play their unison line fortississimo, but also to stand and raise their bells in the air. The effect evokes at once the blasting of factory sirens and a massed cry of triumph – or, perhaps, something more ominously violent.Footnote 18 The other notable device comes at the return of the ostinato-based texture after a faster, more freely composed interlude: at this pivotal moment in the simple ternary structure, an actual sheet of steel is introduced into the percussion section (Figure 1).Footnote 19 The large plate of metal is shaken and hammered to add a loud, unpitched rumble to an already pummelling tumult of timpani, cymbals, bass drum, and tam-tam. The unusual ‘instrument’ appears to collapse the distinction between the subject matter announced in the work's title and its musical representation. It is almost as if, through its frantic labouring, the orchestra itself has forged the steel.

Figure 1 Percussionists preparing for the Australian premiere of the Iron Foundry in 1936. The sheet of steel (and the performers shaking it) can be seen on the right. The nails mentioned in the caption are not called for in Mosolov's score; they were presumably added here to enhance the general effect of metallic noisiness. [Unsigned], ‘Iron Foundry Noises’, The Herald [Melbourne], 10 July 1936, 3 (photographer uncredited). Scan courtesy of the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

The circulation of this ferocious music – its transformation into an unlikely hit – illustrates how the newly formed local and transnational networks that sustained musical modernism after the First World War depended on their interconnection, and offers a rare example of a work making the leap from that relatively exclusive domain to a more public and commercial one. In the early Soviet Union, the leading body for the propagation of modernist music was the Moscow-based Association for Contemporary Music (Assotsiatsiya sovremennoy muzïki, ASM), founded in 1923. ASM was affiliated with the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM), an organization established in Salzburg a year earlier, and known for its influential series of contemporary music festivals. One function of the ISCM's annual gathering, which was held in a different city each year, was as a site of display and discovery: it showcased works and composers, often previously obscure, to an international audience including performers, critics, publishers, and other new-music insiders. A platform of this kind was especially valuable to composers from the ‘peripheries’, who otherwise faced an uphill struggle for recognition from the centre.

The centre–periphery dynamic was evident in the case of the Soviet Union, although the musicians associated with ASM hardly needed help to ‘keep up’ with the West. In the 1920s, they had ample opportunities to hear the kind of repertoire performed at ISCM festivals. Esteemed Western musicians, such as Bartók and Casella, toured to Moscow and Leningrad, and contemporary works from abroad including Pacific 231 were regularly performed – lending credence to the notion that Mosolov's factory was inspired, at least in part, by Honegger's locomotive.Footnote 20 But Soviet musicians found it difficult to attain permission to travel abroad, a situation that hindered the dissemination of their work.Footnote 21 The ISCM offered a valuable channel for making their music known internationally, even if they could rarely attend the festivals in person. From 1924 to 1931, scores by ASM-associated composers were regularly performed at the festivals. This pathway into the West was further bolstered by an agreement between the Soviet State Publishing House and the Vienna-based publisher Universal Edition (UE), through which the latter attained the rights to distribute new Soviet scores internationally.Footnote 22

The mutually beneficial connections between ASM, the ISCM, the Soviet State Publishing House, and UE formed a composite network of patronage and exchange that decisively shaped Mosolov's career. With the support of Reyngol′d Glier and Nikolay Myaskovsky, his composition teachers at the Moscow Conservatory, Mosolov became established in the mid-1920s as a rising talent in ASM circles. Two events in 1927 confirmed his status. In the summer, his First String Quartet was performed by the renowned Viennese ensemble the Kolisch Quartet at that year's ISCM festival in Frankfurt. Although by the 1930s Mosolov's quartet seems to have been largely forgotten by Western critics – otherwise they might have realized that layered ostinato constructions were characteristic of his musical language beyond the Iron Foundry – the generally favourable reviews it received marked a significant milestone in his career.Footnote 23 In December, his reputation at home was further underscored at the concert organized by ASM in Moscow to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the Russian Revolution. This event – ‘undoubtedly the zenith of ASM's concert activities’, according to one survey of Soviet musical life in the 1920s – offered a prestigious setting for the premiere of the four-part suite from his ballet Stal′ (‘Steel’), the first movement of which was the Iron Foundry. Footnote 24

In 1929, UE published the international edition of the Iron Foundry score, which did not explain that it was an excerpt from a ballet, and in the following year it began to be performed internationally as a standalone orchestral miniature. The work was first heard outside the Soviet Union in Berlin in March 1930.Footnote 25 But what seems to have been the breakthrough moment came six months later, at the ISCM festival in Liège in Belgium, where the Iron Foundry was programmed as the final item of the second orchestral concert on 6 September. Mosolov's music proved memorable on this occasion not only because it was unorthodox and arresting, but also thanks to the contingent circumstances of the performance. It was flattered by comparisons with another machine-inspired work that featured in the first orchestral concert two days earlier: the young Belgian composer Marcel Poot's Poème de l'espace (1928), a symphonic poem depicting a Transatlantic flight (a nod to the then-recent achievement of Charles Lindbergh). Critics at Liège derided Poot's juxtaposition of up-to-date subject matter with an outmoded compositional idiom. ‘Is it possible that this young Flemish musician thinks he is modern because he sometimes dares to use a bunch of dissonant chords?’, scoffed the influential Parisian critic Henry Prunières. ‘Nothing [could be] more clichéd than this symphonic poem which brings back the memory of compositions perpetrated around 1890 by composers influenced by Wagnerism and the Russian school.’Footnote 26 Mosolov, by contrast, created monumental orchestral effects without seeming stuck in the nineteenth century, even if his strident horn theme suggests that Romantic symphonism was far from entirely expunged. Whereas Poème de l'espace sank into obscurity, the Iron Foundry's punch helped it stand out in the ISCM's notoriously crammed programmes. At the end of an exhausting week of concerts and social events, a blast of Mosolov seems to have revived the audience, or at least allowed a ‘tired public … to relax its strained nerves’.Footnote 27 The Iron Foundry may have been ‘the only thing in the festival to evoke hisses’, but this counted for much more than weary indifference.Footnote 28

After Liège, the floodgates opened. As one 1930s dictionary of modern composers reported, the ‘success of this amazingly vital work was so instantaneous’ that performances were scheduled ‘thru-out the entire music world’.Footnote 29 Within twelve months of the festival, the Iron Foundry had been played in cities including Düsseldorf, Naples, New York, Paris, and Vienna.Footnote 30 The first London performance in February 1931 was broadcast by the BBC.Footnote 31 In the summer, the work's merits would be debated in front-page articles in the broadcaster's Radio Times magazine, a publication whose weekly circulation in that year averaged 1.5 million.Footnote 32 Over the next few years, the piece continued to enjoy regular performances and broadcasts in Western Europe and America. It benefited especially from being taken up by celebrity conductors, including Leopold Stokowski and Arturo Toscanini, since performances by the great maestros attracted extensive newspaper coverage, which, in turn, stirred up further curiosity and demand.Footnote 33 Piggybacking on the proto-globalization of Western art music in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – the diffusion of its cultural and institutional practices via European-dominated networks of power and commerce – the Iron Foundry also reached more ‘peripheral’ sites of concert culture, such as Bucharest, Buenos Aires, and Manila.Footnote 34 A performance in Sydney in 1936 was attended by the Queen of Tonga.Footnote 35 Soon enough, recordings were issued: two in late 1933 by Parlophone and Pathé/Columbia, and another in early 1938 by Victor.Footnote 36 These companies were looking to capitalize on a public demand for Mosolov's work that was more voracious and widespread than has previously been recognized. In an increasingly global marketplace, the Iron Foundry became a highly productive commodity, disseminated to its multi-continental audience through pathways closely tied to the imperialist–capitalist world order – to which the Soviet Union itself, of course, was fundamentally opposed, in ideology if not always in policy.

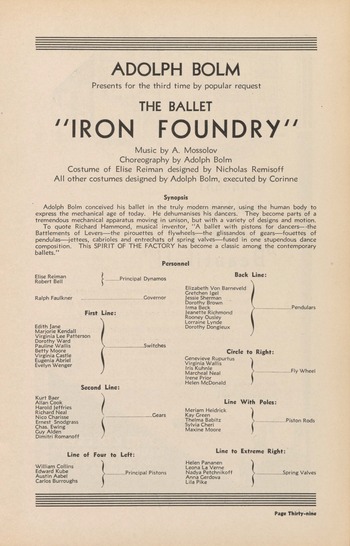

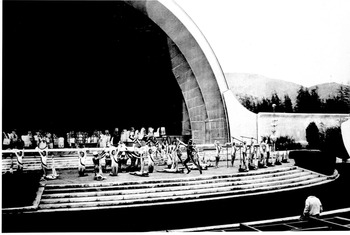

Less than a year after the Liège performance, the Iron Foundry even arrived in Hollywood. In early 1931, the choreographer Adolph Bolm, a former member of the Ballets Russes resident in the United States since 1917, was contracted by Warner Brothers to work on a film called The Mad Genius, a melodrama loosely based on the relationship between Diaghilev and Nijinsky.Footnote 37 Reportedly inspired by visits to a Ford assembly line and the printing press for the New York Times, two paradigmatic sites of American mass production, Bolm conceived the idea of a ‘factory’ ballet to be danced to the Iron Foundry. Mosolov's music and most of the factory sequence were cut from the final edit of the film, but Bolm ensured that his work did not go to waste. On 28 July 1931, his new ballet, now given the title The Spirit of the Factory, was performed for the first time at the Hollywood Bowl, which could hold approximately 20,000 spectators. The ballet was revived ‘by popular request’ the following summer (‘Never before has there been in the history of the Bowl such an insistent demand for repetition of a ballet’, the programme claimed), and restaged thereafter at various American venues, exemplifying the wide appeal of its increasingly well-known score.Footnote 38

There is a sad irony to the timing of the Iron Foundry's international success. With the beginnings of Stalin's ‘cultural revolution’ in 1928–9, ASM lost ground to its cultural–political rival, the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (Rossiyskaya assotsiatsiya proletarskikh muzïkantov, RAPM), who decried modernism as Western decadence and sought instead to promote a truly ‘proletarian’ music (meaning, primarily, mass songs for the workers).Footnote 39 Flush with their newfound authority, critics aligned with this movement brutally criticized Mosolov for his social irresponsibility and even degeneracy, in terms that anticipated the later orthodox Soviet view of the Iron Foundry as a ‘grossly formalistic perversion of a contemporary topic’.Footnote 40 As well as severely damaging Mosolov's career at home – to the point where in March 1932 he would appeal directly to Stalin himself for help as a ‘persecuted and entirely disenfranchised musician’ – the changed balance of power in Soviet musical life also threatened to stymie the Iron Foundry's rapidly growing reputation abroad.Footnote 41 In 1931, RAPM adherents at the State Publishing House tried to block a second edition, only relenting after UE protested to the USSR's Foreign Ministry.Footnote 42

From summer 1932, when the founding of the state-run Union of Soviet Composers put an end to the old ASM/RAPM rivalry, Mosolov was partially rehabilitated, even if the emerging dictate of socialist realism demanded a shift in compositional style.Footnote 43 But in late 1937, he became caught up in the persecutions of the Great Terror: accused of drunken hooliganism, he was sentenced to eight years imprisonment in the gulags (he was released after nine months, following the intercession of Glier and Myaskovsky, his dependable former teachers).Footnote 44 The details of this mistreatment did not become known in the West until the late twentieth century. For us now, though, the diverging paths of Mosolov and his famous composition – one trapped in a labour camp, while the other continued to traverse the globe – underscore the extent to which the Iron Foundry became detached from the life of its creator. Already restricted by the Soviet Union's absence from existing frameworks of international copyright relations (such as the Berne Convention), his control over how his international hit was disseminated became non-existent. His ability to influence how the work was understood was equally limited: even before the Great Terror, Mosolov's own voice had been entirely absent from the discussion of him and his music in other countries. At Liège, the Iron Foundry became an agent in its own right, with its own biography.

The ultra-modern and the primitive

Unearthing the profusion of performances, recordings, and broadcasts of the Iron Foundry in the 1930s raises more questions than it answers. Why this piece and not some other, when so much of the music performed at ISCM festivals fell instantly into obscurity? How did listeners interpret Mosolov's music, and why were so many of them so entertained by it? One initial hypothesis might be that the Iron Foundry's machine aesthetic confirmed its enthusiasts’ sense of themselves as moderns, and, by extension, their privileged standing in the global political order. In Liège, such an effect would likely have been reinforced by the context of the performance. The ISCM came to Belgium in 1930 because the country was hosting an international exposition, a genre of event that exemplifies perhaps more than any other the depth of the historical connection between internationalism and imperialism.

Since their beginnings in the mid-nineteenth century, international expositions had done much to shape how their millions of visitors understood their place in world history, not least by perpetuating the Enlightenment tradition of treating mastery of science and technology as a ‘measure’ of the distance between Western civilization and its supposedly less sophisticated Others.Footnote 45 The polarity was writ large in Belgium in 1930. The Exposition was divided into two strands: Antwerp presented the colonial exotica, and Liège the scientific and industrial exhibits.Footnote 46 Located in the country's industrial backbone, the so-called sillon industriel (industrial furrow), Liège was an apt choice for this assignment. Indeed, the city was felt particularly well suited to host the 1930 International Foundry Congress (Congrès International de Fonderie) – one of the many international conferences held in Belgium in association with the Exposition – because it boasted, as a brochure for the Exposition noted, ‘foundries remarkable for their importance or specialization’.Footnote 47

In the sillon industriel, foundries were emblems of progress and prosperity. Thanks to the Iron Foundry, the region's vaunted plants formed more than a mere backdrop to the ISCM festival: the steel sheet demanded by Mosolov's score was, reportedly, cast specially for the occasion by a local foundry.Footnote 48 In this rendition, the music made audible a characteristic material product of Belgian modernity. Especially in the context of the Exposition, such a spectacle was redolent of familiar imperialist and gendered tropes about modern man conquering the natural world. In his short essay on Mosolov and the Iron Foundry for the ISCM festival programme book – the only information about the composer available to the audience at Liège – the Soviet conductor Nikolay Anosov laid claim to precisely these ideas: Mosolov, he argued, ‘rises to the exalted pathos of the power of the human genius that has subjugated the forces of nature’.Footnote 49

Anosov's interpretation was repeated almost verbatim in several press reports.Footnote 50 Yet in the age of mass production and industrialized warfare, this was just one possible way to parse the sprawling field of symbolism associated with machines. Charting the racial imagination that underpinned George Antheil's Ballet mécanique – another landmark machine-inspired composition of the 1920s – Carol Oja has demonstrated the proximity and, in terms of compositional technique, the frequent indistinguishability of the ultra-modern and the primitive.Footnote 51 Conceived as an emblem of enormous power and brutal indifference to a bourgeois aesthetics of subjectivity, the machine came to perform some of the same polemical work in modernist art as, say, pre-modern folk ritual. So it was that, in 1921, T. S. Eliot could famously describe Stravinsky's evocation of pagan Russia in The Rite of Spring as seeming to ‘transform the rhythm of the steppes into the scream of the motor-horn, the rattle of machinery, the grind of wheels, the beating of iron and steel, the roar of the underground railway, and the other barbaric noises of modern life’.Footnote 52

To communicate mechanicity or primitivism, early twentieth-century composers pushed two musical parameters to their extremes. The first was repetition. In the Iron Foundry, the ‘relentlessness of mechanical motion’, as one observer at Liège described it, seemed to defy inherited conceptions of musical form.Footnote 53 The work's ‘obstinate repetition’, as another critic put it, negated development in the traditional symphonic sense; machine-like replication forestalled organic growth.Footnote 54 To some early twentieth-century critics, this state of suspended animation would have rendered the music deeply suspect: in his notorious critique of Stravinsky in Philosophy of New Music (1949), Adorno treated compulsive repetition quasi-psychoanalytically as a symptom of infantilism and regression.Footnote 55

The second parameter emphasized in the mechanical/primitive idiom was noise: what Joy H. Calico, echoing the anthropologist Mary Douglas's influential work on the social construction of dirt, has called ‘sound out of place’.Footnote 56 The Iron Foundry transgressed naturalized sonic limits in both a qualitative sense, through the depiction of industrial technologies in concert music and the inclusion of the steel sheet as a musical instrument, and a quantitative one, through brutal dissonance and massive orchestral power. At Liège, noisiness in the latter sense was amplified by the ‘extreme resonance’ of the Conservatoire's concert hall, leading one critic to assert that the Iron Foundry was ‘one of the noisiest pieces of music ever written’.Footnote 57 The clamour even prompted some to refer ironically to contemporary anxieties about the health threats of industrial noise. Imogen Holst, for example, described the Liège gathering as ‘the noisiest festival on record: – towards the end our nerves got somewhat frayed at the edges, and the mere sound of a bicycle bell was enough to make us leap and turn pale’.Footnote 58

In the Iron Foundry, repetition and noise were inseparable: Mosolov's chief strategy for both portraying machines and generating cacophony was to layer ostinato cells. Although some found the din intolerable, others revelled in its rhythmic clamour. As the historian of sound Karin Bijsterveld has observed, early twentieth-century listeners tended to distinguish between different categories of loud noise. ‘Intrusive’ sound, such as the sudden passing of a train or aeroplane, was perceived negatively: it was irregular and unpredictable, and thus seemed to threaten the listener. By contrast, ‘sensational’ sound, such as ‘the running of machines’, was marvelled at: it was regular and predictable, and could ‘fill the environment and surround the subject’, creating feelings of wonder and awe.Footnote 59 Through its poundingly repetitive noisiness, the Iron Foundry (re)produced the sensational soundscape of the ‘technological sublime’.Footnote 60

The compositional means for achieving this effect seem indebted above all to The Rite of Spring.Footnote 61 For Mosolov, as for Stravinsky, ostinato technique served to strip the orchestra of its human essence. The only element in the Iron Foundry that recalled the human voice was the blasting horn theme; but this was a cry of the collective, not the utterance of a particular subject. This deindividualized music had the potential to induce Rite-like feelings of dread: one reviewer of The Spirit of the Factory labelled the ballet a ‘startling, even terrifying picture of a roboticized humanity’.Footnote 62 But perhaps surprisingly, given just how audible it is, few, if any, critics in the 1930s actually pointed out the connection between The Rite and the Iron Foundry. There seems to have been a crucial, even categorical, distinction between the two works: whereas Stravinsky's could be heard, despite its primitivist scenario, as evocative of modernity's soundscape, Mosolov's was explicitly mimetic. To refer, as so many did, to the ‘noise’ of the Iron Foundry was not simply to describe its sonic excess; it was also to ponder the imitative relationship between this music and industrialism's sounds and rhythms. Sublime visions of ‘exalted pathos’ or ‘roboticized humanity’ notwithstanding, the mimetic gambit was not usually felt to warrant the fundamental seriousness accorded to The Rite. As one critic reported from the Berlin performance in March 1930, although ‘the racket was ear-splitting’, Mosolov's creation was, in the end, ‘a charming and, what's more, brilliantly done orchestra-joke’.Footnote 63

The particular and the universal

Even if its debts to The Rite went largely unremarked at the time, the Iron Foundry was often presented as belonging to a specifically Russian musical tradition, most obviously through its inclusion in all-Russian programmes of orchestral music.Footnote 64 After 1917, however, the continuity of that tradition could hardly be taken for granted. When audiences in the West encountered the Iron Foundry, in the knowledge that its composer lived in a radically reorganized society, they seem to have felt uncertain about the extent of their contemporaneity with Soviet citizens. Did factories in Moscow sound the same as those in Liège? And did these different societies hear industrial noise in the same way? In raising such questions, the work confronted its international listeners with what is now a historiographical problem: evaluating whether the Soviet Union belonged to a shared modernity or represented one distinct form among a gamut of modernities.Footnote 65

In 1930, there was a gap in the market for a quintessentially ‘Soviet’ musician. In other fields, above all cinema and visual art, Western audiences could access culture with distinctively Soviet qualities. But the limited body of Soviet music that circulated internationally during the 1920s, such as Myaskovsky's symphonies and piano sonatas, seemed disappointingly consistent with pre-revolutionary aesthetic norms.Footnote 66 There was one significant exception: Prokofiev's ballet Le Pas d'Acier (‘The Steel Step’), first staged in Paris in 1927. As Lesley-Anne Sayers and Simon Morrison have described, the factory-based scenario was Diaghilev's attempt ‘to bring the “new Russia”’ to the West.Footnote 67 There was confusion, though, about just how Bolshevik this ‘Bolshevik ballet’ really was: Russian émigrés were prominent among the contributors, and Massine's choreography for the Ballets Russes undercut the pro-Soviet message by ‘allowing the factory to be interpreted as a symbol of oppression’.Footnote 68 The Iron Foundry shared Le Pas d'Acier's industrialized aesthetic and in places a very similar musical vocabulary, but was less ambiguous in its origins.Footnote 69 It seemed to mark the arrival of a truly Soviet music: the product of a distinctive form of modernity. As one Austrian critic put it, Mosolov was not one of those composers who ‘despite revolution and social chaos, clings on to the old, grand musical forms’; his work was one of the ‘natural healthy children of the revolution’.Footnote 70 The Iron Foundry, it was claimed elsewhere, was ‘Russia's five-year plan set to music’.Footnote 71

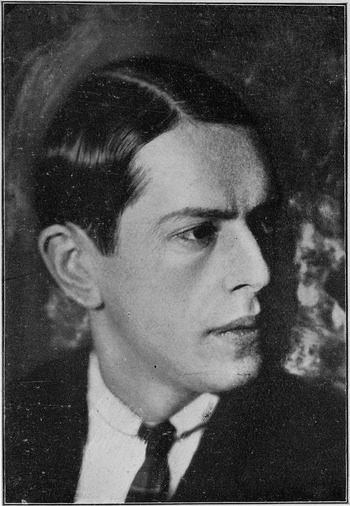

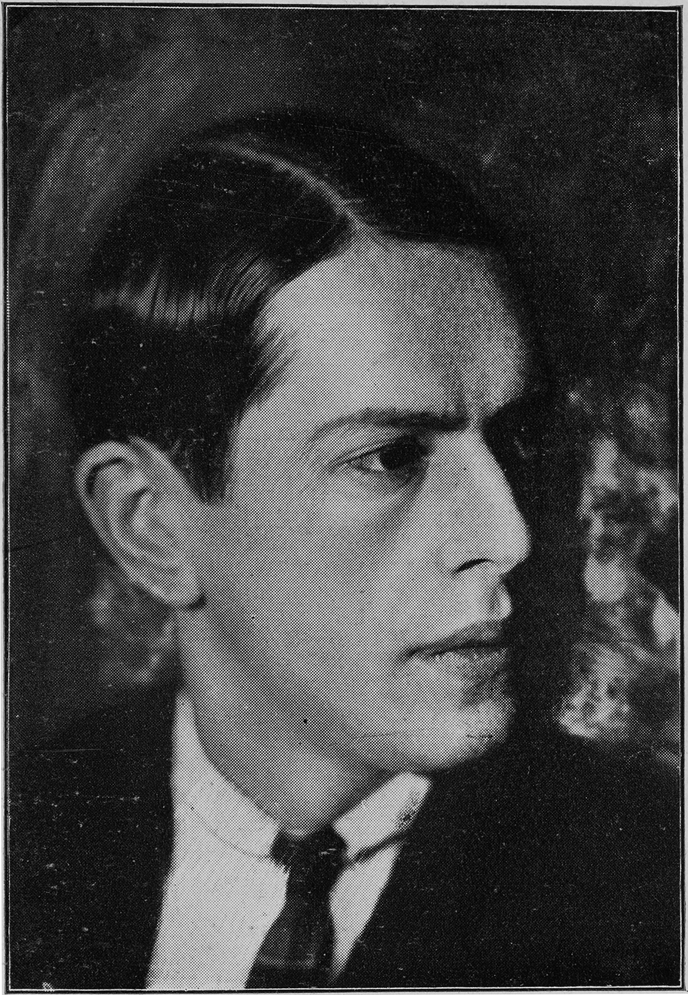

Mosolov himself was often presented as an essentially Soviet figure. In this period, the Western cliché of the Soviet artist–intellectual was of a man who had overcome pre-revolutionary hardship, fought in the Civil War, and now worked in an industrial setting.Footnote 72 Mosolov could be slotted neatly into this mould: while the Iron Foundry confirmed a stereotypically Soviet infatuation with industrialism, Anosov's biographical note for the ISCM festival dutifully recorded the composer's service in the Red Army between 1917 and 1920 (although it steered clear of what we now know to have been his middle-class childhood).Footnote 73 Combined with the shadowy moodiness of the photograph of the composer in the festival programme book (Figure 2), such tantalizing biographical details fed an image of Mosolov as committed revolutionary. The French composer and critic Florent Schmitt, despite his right-wing political views, was among the more extravagant of those to fetishize Mosolov's Sovietness: he lingered on the ‘hardened face’ and ‘eyes of flame’ of ‘this ex-combatant of the Red Army’, and reported that ‘the acuity and intransigence of his art belong, it seems, to a left no less extreme than his political opinions’.Footnote 74 Many came to assume that the Iron Foundry epitomized the musical culture of post-revolutionary Russia, a situation that led some pro-Soviet ideologues to try to challenge the misleading generalizations that the work's international exposure inspired.Footnote 75

Figure 2 The enigmatic portrait photograph of Mosolov in the 1930 ISCM festival programme book. Anosov, ‘Alexandre Mossolov’, 80 (photographer uncredited). Scan courtesy of the British Library, London.

At Liège, the ISCM festival context may have strengthened the idea of Mosolov as a distinctively Russian/Soviet composer. As synchronic overviews of an international field, these occasions often led attendees to compare and catalogue what they heard, modes of listening that encouraged essentializing claims about nationality and race. (In 1927, for instance, the British tabloid the Daily Mail compared the ISCM to a zoo, whose ‘several different tribes’ included the ‘Viennese Disintegrators’, ‘Parisian cynics’, and ‘savage Easterners’.Footnote 76) On the other hand, as annual snapshots of the diachronic unfolding of music history, the events also proffered an experience of ‘contemporary music’, a category that did not belong to any one country. The Prague-based critic Erich Steinhard surely had the Iron Foundry in mind when at the end of the 1930 festival he complained about: ‘the tendency towards the deployment of sound masses and their excessive amplification in dynamics. What a racket.’Footnote 77 He was among several observers at Liège to compare Mosolov to Honegger, a gesture whose continual repetition in the years to come would do much to establish machine-imitating works as a recognized category of modernist music.Footnote 78 As a major contributor to this quintessentially modern and international genre, Mosolov became a symbol not only of Sovietness but also of new music in general. So it was that a correspondent to The Musical Times in 1939 could refer casually to music ‘from Palestrina to Mossolov’.Footnote 79

As a border-crossing genre, machine-inspired works seemed to mediate the unprecedented sounds of a shared present. The Iron Foundry and Pacific 231, claimed one French writer in 1937, ‘provide a true reflection of the active, breathless, noisy life of the twentieth century’.Footnote 80 As we are about to see, nearly all critics agreed that the Iron Foundry was startlingly ‘realistic’. One striking thing about this consensus is that Western listeners felt so confident in making the judgement. Industrial technology, most seem to have supposed, was a universally legible ground, a pre-ideological building block of modern societies. A foundry was a foundry, regardless of who controlled the means of production. The prevalence of this assumption indicates how commonplace it was to imagine the world as bound together by processes of modernization that ran deeper than cultural or political differences. It was this conviction that lent credibility to early twentieth-century claims that the future would inevitably be international.

Yet such fantasies arguably did little to promote genuine mutual understanding. As the few musical commentators in the West who did follow Russian-language musical debates tried to explain, to limited effect, the Iron Foundry did not enjoy anything like the same profile or popularity within the Soviet Union as it did elsewhere.Footnote 81 When the work received its first international performances in 1930, hardly anyone in the audience seems to have realized that the period when such music could have achieved official support or public acclaim in Mosolov's own country was already over. In a pattern that would recur throughout the history of Western engagement with the USSR, a fascination with exotic or otherwise arresting cultural phenomena did little to advance – indeed, actively impeded – a more informed appreciation of what was actually distinct about how social and cultural life there was developing.Footnote 82

Artistic creation and mechanical reproduction

Some critics thought the Iron Foundry so realistic that they described the work as a ‘photograph’ or Mosolov as a ‘photographer’.Footnote 83 Although sound recording might have provided a more straightforward analogy, the choice of photography said something about the quality, as well as the extent, of the music's perceived literalism. Because its obsessive repetition did not project a musical subjectivity that developed over time, the Iron Foundry seemed, like a photograph, static and flat. Consequently, it did not meet the criteria of ‘depth’ against which the aesthetic value of instrumental music was conventionally judged, especially in the Austro-German tradition.Footnote 84 The Iron Foundry had a captivating surface, but an absent centre; as Schoenberg might have put it, the music had superficial ‘style’, but lacked an abstract ‘idea’.Footnote 85 The young Benjamin Britten came to a similar conclusion when he heard the work at the Proms in September 1931: the Iron Foundry, he recorded in his diary, was ‘amusing – nothing more’.Footnote 86

The charge of hollowness echoed a long-standing unease among elite musicians and critics in the West about the popularity of Russian music they dismissed as shallowly programmatic.Footnote 87 It also seems characteristic of broader misgivings about musical realism and, in particular, musical mimesis. The latter especially was difficult to reconcile with Romantic and modernist notions of artistic originality, not least because it seemed to require an instability or even renunciation of individual personality. In the reception of the Iron Foundry, mimesis itself was often presented as a kind of mechanical procedure, devoid of full subjectivity. As the British critic W. J. Turner sniffed in 1931, Mosolov ‘shows no more mind than a photographic plate which records a scene impinged upon it’.Footnote 88 Used in this derisive way, the photography metaphor implied that the Iron Foundry was not just about mechanical production, but was also an object that had itself been mechanically produced, and so did not qualify as art.

Turner was far from alone in complaining that Mosolov's compositional project was one of naive imitation rather than transubstantiating musicalization. Guided by the idealist aesthetics of Benedetto Croce, Italian critics tended to argue that the Iron Foundry could be assessed ‘as a demonstration of skilful instrumentation adequate for the realistic reproduction of noises, but not as a work of art’.Footnote 89 Although Mosolov's ‘mighty hymn to mechanized labour’ was actually praised by one Soviet critic at the Moscow premiere for ‘go[ing] further and deeper’ than simply depicting a factory, some writers in other countries – perhaps backdating the slogan ‘socialist realism’ to 1927 and misconstruing what it meant in practice when applied to music – attributed what they saw as the Iron Foundry's excessive literalism to the inescapable pressure on artists in a communist state to produce propaganda for the regime.Footnote 90 Mosolov, in other words, was just another cog in the Soviet machine.

Another sceptic, at least initially, was the philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch. When he heard the Iron Foundry in Prague in 1931, he decried its ‘childish idea of one-upmanship. The Symphony of Machines makes sirens wail and turbines whir just as the orchestra of [Beethoven's] Pastoral makes sheep bleat and cows moo. It is enough to make one weep.’Footnote 91 By the time he came to write Music and the Ineffable (1961), though, Jankélévitch saw Mosolov's literalism in a different light. He praised the Iron Foundry as a work in which the ‘atonal racket of the machines resounds as it is’, and thus as an example of ‘inexpressive music’ that ‘allows things themselves to speak, in their primal rawness, without necessitating intermediaries of any kind’.Footnote 92 Jankélévitch's conversion from detractor to advocate did not require a departure from the widespread view of the Iron Foundry as quasi-photographically realistic; this conception of Mosolov's music could support antithetical aesthetic judgements.

The accuracy of representation in the Iron Foundry did not go entirely unquestioned. After the performance in Berlin in March 1930, Mosolov's music came under attack from an unexpected source: the Giesserei-Zeitung, the ‘Foundry Newspaper’, the German trade journal for those working in the industry. This publication ridiculed Alfred Einstein's claim in Die Musik that the foundry environment was ‘astonishingly well observed’.Footnote 93 ‘The critic has certainly never visited an iron foundry’, the writer for the Giesserei-Zeitung remarked:

The blasting furnace, steelworks, rolling mill, and hammer mill, or the smeltery not only convey a completely different optical impression from the iron foundry, but also have a completely different acoustic effect. The iron foundry is a relatively quiet plant, in which the heaving and roaring of machines is almost entirely absent. … The manager of a foundry would come down like a ton of bricks on anyone who put on a spectacle in his plant like the one the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra staged under the instructions of Mr Mosolov. And the factory inspectors would intervene as quickly as possible and shut down the whole enterprise!Footnote 94

As Bijsterveld has shown, early twentieth-century industrial workers were highly discriminating about noise, which could reassure them that mechanisms were running properly or alert them to inefficiencies and faults.Footnote 95 By these standards of aural expertise, the Iron Foundry was laughable.Footnote 96

There is a cautionary tale here: upper-middle-class music critics probably cannot tell us what industrialism really sounded like. There is a telling contrast between their proclamations of precise literalism and the confusing proliferation of names by which Mosolov's work was known (these included ‘Factory’, ‘Soviet Iron Foundry’, ‘The Symphony of Machines’, and ‘The Iron Rolling Mill’). Yet should we assume, as the writer for the Giesserei-Zeitung did, that what listeners found so compellingly realistic was necessarily a literal reproduction of a particular sonic environment? The British critic Edwin Evans argued after the Liège performance that noise was a red herring, insisting instead that what mattered was: ‘the essential dynamism of the music. It is loud, of course, as the subject demands, but loudness is a relative factor and I believe the ruthless pulsation would make it scarcely less impressive without the loudness.’Footnote 97 Other critics agreed that the Iron Foundry was an ‘essay in rhythm’, in which ‘Mossolov contrived to give an impression of musical pattern allied with the mechanised certainty of foundry work’.Footnote 98 Taking our cue from these comments, we might conclude that what the Iron Foundry offered its listeners was not the phonograph-like recreation of a sound source. Rather, the synchronized, repetitive movements of the musicians replicated, in sight and sound, the novel and much-discussed somatic experience of working on an assembly line.Footnote 99

This scripting of the body was accentuated in The Spirit of the Factory, Bolm's ballet for the Hollywood Bowl. In setting the Iron Foundry to dance, Bolm restored its original function as ballet music. The resulting choreography suggests that he was drawn to the score not only because he was following the general vogue for machine aesthetics, but also because he wanted to exploit a more specific fascination – one shared by the early Soviet theatrical avant-garde – with the embodied mimesis of mechanicity.Footnote 100 Bolm divided his large corps de ballet into groups that imitated various kinds of mechanisms moving in synchrony: parallel lines of ‘Gears’, ‘Switches’, and ‘Pendulars’ in the centre, four ‘Principal Pistons’ to one side, five ‘Spring Valves’ to the other (Figures 3 and 4). The result was a vast array of quasi-mechanical movement. As the most concrete elaboration of the Iron Foundry as mimetic display, this choreography brought to the fore qualities also present in concert performances and even in radio broadcasts and gramophone recordings. Playing off the long-standing tradition of imagining the orchestra as a giant machine – and in this sense, it really was an ‘orchestra-joke’ – the work induced musicians to personify the dynamism of mechanical parts.Footnote 101 Its mimetic gestures drew out the parallels between the specialized labour of orchestral musicians, tessellating into a complex output that no individual could produce alone, and the repetitive, rationalized movements that defined the worker–machine interface in the age of Ford.

Figure 3 Synopsis and personnel for the 1932 run of Adolph Bolm's Iron Foundry ballet. Hollywood Bowl Association, Symphonies under the Stars: 1932: Aug. 9, 11, 12, 13: Program Magazine: Sixth Week (1932), 39. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives.

Figure 4 Rehearsal of The Spirit of the Factory at the Hollywood Bowl, believed to date from shortly before the first performance in 1931 (photographer uncredited). Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Archives.

Modernism and mass entertainment

Mosolov's severe dissonances did not literally transcribe the sounds of a foundry. But they were integral to his international reputation as a modernist innovator who could be named alongside the likes of Krenek and Walton as one of the most promising young composers of his generation.Footnote 102 Even in the ISCM context, Mosolov's discordant raucousness seemed extreme to some – hence the hissing in Liège, which recalled what was by 1930 an established tradition of protest against modernist music (one that had occasionally reared its head at previous ISCM festivals).Footnote 103 At the same time, though, not everyone took the Iron Foundry seriously. As was evident in their questioning of whether Mosolov's ‘photograph’ was really art, some critics were sceptical of music that listeners could grasp intuitively without any special effort or expertise.

Even sympathetic commentators tended to present the Iron Foundry as a gimmick, an aesthetic category which Sianne Ngai has recently theorized as emerging from the conditions of mass production, and which she distinguishes, in part, by its simultaneously appealing and irritating capacity to seem ‘both to work too hard and work too little’: too hard, in this case, because of the lengths to which Mosolov had gone to achieve his supposed realism (especially by calling for the steel sheet) and the extremes to which he pushed the orchestra in consequence; and too little, because of his reliance on external stimuli, his apparent disregard for more abstract concerns, and the cheap thrills he served up to unsophisticated audiences.Footnote 104 Though disdained by more earnest critics, the Iron Foundry's gimmickry was pushed by some performers to the point of full-blown slapstick. In their rendition at a Christmas concert in 1937, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra donned workers’ overalls, while their conductor Ernest MacMillan wielded a monkey wrench as a baton. When the piece finished, MacMillan himself recalled, ‘a factory whistle blew and the players knocked off work and opened lunch boxes, the contents of which were consumed on stage’.Footnote 105

This kind of tomfoolery made it easy to sneer at the work's success. Yet as Ngai argues, judging something a gimmick, however damning the rhetoric deployed, is always somewhat equivocal, since part of what defines the form, as both ‘a wonder and a trick’, is the deeply ambivalent responses it provokes. One sign of this ambivalence, she suggests, resides in how we uneasily acknowledge the gimmick's charms as ones ‘to which others, if not ourselves, are susceptible’.Footnote 106 This dynamic of observing, at a safe distance, the unthinking enjoyment of other people was evident in the Iron Foundry's critical reception: even the most hostile reviewers had to admit that Mosolov's mimetic gambit appealed to a broad public, if only as grounds on which to indict that public. Noting that Pacific 231 and the Iron Foundry ‘never fail to bring the house down whenever they are performed’, one British writer concluded disparagingly in 1931 that ‘the public will tolerate almost any degree of cacophony provided it has an illustrative intention’.Footnote 107 That tolerance was not universal, though: in France and the United States, some conductors adopted the practice of making the Iron Foundry the last item on a concert programme and providing time for patrons offended by its abrasiveness to leave early, while the rest stayed to enjoy the amusing finale.Footnote 108

For the Iron Foundry, the rift between modernism and mass culture, the so-called ‘great divide’ of the early twentieth century, did not prove impassable.Footnote 109 The work regularly appeared in the kinds of middlebrow settings, such as children's concerts or the Proms, that have recently attracted much musicological scrutiny.Footnote 110 However, no one seems to have imagined this gimmicky music serving as a vehicle for the aspirations of aesthetic education and moral uplift usually associated with middlebrow culture, especially earlier in the twentieth century.Footnote 111 (In its register and reception, the work was clearly very different to the symphonies from the later 1930s by Shostakovich and others that Pauline Fairclough has suggested might be productively described as emerging from a distinctively Soviet middlebrow.Footnote 112) At once too challenging and too accessible to slot comfortably into any established category, the Iron Foundry reminds us that the middlebrow project was always partial and incomplete. Much the same audiences we most strongly associate with middlebrow culture in this period, in much the same contexts, did not only participate in anxious efforts to mediate between the extremes of high and low culture. They were also drawn to more frivolous – and perhaps more subversive – moments in which the heady pleasures of popular culture, only lightly transformed, surfaced unexpectedly in the sanctum of the concert hall.

An unstable blend of the ‘high’ and the ‘low’ was characteristic of machine aesthetics, due to its strong associations with both modernism and mass entertainment. The duality was evident in the case of the Iron Foundry: Mosolov's music belonged not only in the highbrow orbit of Stravinsky and Futurism, but also, as The Spirit of the Factory demonstrates most vividly, in a lineage of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century popular entertainments that generated spectacle and humour from mechanical movement. In the latter respect, one notable precursor was the ballet Excelsior, first staged in Milan in 1881, and then performed in numerous tours and revivals through to the mid-twentieth century. As Gavin Williams has described, the ‘proto-robotic dance’ of this long-running extravaganza embraced the pleasures of ‘mass choreography’ and ‘geometry in motion’.Footnote 113 Excelsior, argues Williams, can be thought of as what Siegfried Kracauer called a ‘mass ornament’: a kaleidoscopic spectacle of patterned movement devoid of substantive content – devoid, that is, of ‘depth’ – whose dehumanizing effects reduced human beings to ‘clusters whose movements are demonstrations of mathematics’, and exemplified how the latest capitalist production methods accommodated the individual only as ‘a tiny piece of the mass’.Footnote 114 Deriving from mimesis a particular kind of ornamental abstraction – what the Russian-American conductor Nikolai Sokoloff explained to an audience in Cleveland as its ‘design of circles, parallel and vertical lines’ – the Iron Foundry transformed the orchestra into just such a burlesque of rationalized production.Footnote 115 It actualized the analogy between embodied movement and economic system. Bolm's Hollywood Bowl spectacular brought this patterning of movement into stark relief, in ways that exemplify the dynamic reciprocities between American ballet and commercial show dance in the 1930s, particularly as regards how both genres of performance staged and disciplined working bodies.Footnote 116 Recuperated in California as music to accompany dance, the Iron Foundry realized Kracauer's most famous pronouncement in startlingly literal terms: ‘The hands in the factory correspond to the legs of the Tiller Girls.’Footnote 117

As the objections of the Giesserei-Zeitung suggest, it was not those who really worked in iron foundries who were amused. Mosolov's international audience was primarily a middle-class one. For these listeners, the cognitive dissonance of encountering, simultaneously, orchestral music and industrial noise involved an enjoyable dip in the dressing-up box: the inspired and highly trained artists of a bourgeois institution slumming it as a faceless mass of unskilled labourers appended to an assembly line (a joke realized in a crudely literal-minded way by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, with their overalls and lunchboxes). As one critic reported from a Melbourne performance of the Iron Foundry in 1936:

In common with most examples of ‘proletarian music’ constructed by earnest young men with more intelligence than sense of beauty, ‘The Iron Foundry’ … provides an interesting study in inverted class consciousness. Ostensibly it glorifies the ‘worker’. Actually it depends for a hearing upon the tolerance of leisured and wealthy patrons. No man or woman obliged to toil for daily bread in such a house of torment as is depicted by Mosolov would be likely to welcome its gruntings, raspings, whistles, and shrieks as a form of entertainment. Judged by æsthetic standards, ‘The Iron Foundry’ is an abomination. As a novelty with which to amuse a sophisticated audience it has merit, and the spectacle of trained musicians manipulating steel plates and emulating the roar and rattle of machinery excited on Saturday night a hilarious response.Footnote 118

Mimesis thus underscored, rather than closed, the gap between those present in the concert hall and a seemingly dehumanized industrial proletariat, and in ways that subverted the work's presumed intent as propaganda. Construed as a representative cultural artefact of Russia's misguided social experiment, this ‘noisy novelty’, as the same critic labelled it, was sound ‘out of place’ in more ways than one. Here, despite its origins in the world's first communist state, Mosolov's work made explicit the latent class politics and xenophobia of Henri Bergson's much-cited definition of humour as a collective purging of ‘[s]omething mechanical encrusted on the living’.Footnote 119

Certain of the Iron Foundry's comic effects stemmed, then, from the disjunction between the organic and the mechanical, between music and noise. Yet part of what made the work so distinctive was how it subverted these familiar oppositions by collapsing their polarities in rhythmic entrainment. In a riposte to Bergson and other theorists who espouse ahistorical models in which humour is always caused by conflict or surprise, the literary critic Michael North has proposed that ‘the machine age seems to have brought, along with all its other dislocations, a new motive for laughter and perhaps a new form of comedy’.Footnote 120 Significantly implicated in the gimmick's emergence as an aesthetic category, this ‘machine-age comedy’ extracted humour from the very predictability of repetitive mechanical movement, since ‘the most thorough mechanization can produce, out of its very regularity, a new form of nonsense’.Footnote 121 Just as Charlie Chaplin fascinated so many intellectuals of the day, this comic style cut across the divides between high and low culture.Footnote 122 If we open out the category to include sound and live performance, ‘machine-age comedy’ elucidates the Iron Foundry's appeal as popular entertainment, especially when, with Edwin Evans, we listen for rhythm as the work's primary parameter.Footnote 123 This mass-ornamental music derived humour not only from a conflict between organic life and mechanical repetition, but also from the latter's own distinctive pleasures.

North's perspective places the trope of Mosolov as ‘photographer’ in a new light: what if that metaphor actually reveals an impulse to associate the Iron Foundry with the moving pictures? This proposition lends new significance to how quickly the work made it to Hollywood, if not, in the end, into the movies. (In fact, Bolm's work on The Mad Genius would not be the Iron Foundry's only close encounter with American film: its cinematic potential was also recognized by Walt Disney and Stokowski, who in September 1938 listened to and discussed the work when they were shortlisting music for Fantasia [1940].Footnote 124) Cinema was, after all, the artform par excellence of machine-age comedy. It was also the one in which Soviet modernists of the 1920s achieved their greatest esteem abroad. Indeed, it may be no coincidence that critics from Berlin – where Soviet films had enjoyed their greatest international success, particularly with the release of Battleship Potemkin in 1926 – were the readiest to suggest connections between the Iron Foundry and cinema, with one comparing Mosolov to Edmund Meisel, the composer of landmark film scores including Potemkin, and another labelling the work ‘a skilful sound-film recording of reality’.Footnote 125 Such responses might prompt us to wonder whether the Iron Foundry's allegedly startling realism might be best credited to a correspondence between its distinctive rhythmic patterns and the reproduction of mechanical movement so widely disseminated in the 1920s and 1930s via the mechanically reproduced medium of film. As Hansen argued, cinema in this period became ‘something like the first global vernacular’: ‘an international modernist idiom on a mass basis’, which ‘articulated, multiplied, and globalized a particular historical experience’. The resulting ‘mass production of the senses’ may have done much to enable the Iron Foundry's success, rendering its mimetic gestures both legible and instantly appealing across a vast geographical span.Footnote 126 The work's widespread popularity might therefore be taken as evidence that new technologies really had forged a more genuinely ‘international’ culture. But if so, it was media machines, not industrial ones, that were chiefly responsible.

Novelty and obsolescence

The Mosolov craze was a transient affair. Already in the middle of the decade, there were signs that the composer's star was beginning to fade; by the end of the Second World War, he had all but been forgotten. After his death in 1973, a steady trickle of performances and recordings re-emerged, partly as a result of the efforts of scholars in the West to rescue, in retrospect, the early Soviet modernists they viewed as victims of Stalin's regime.Footnote 127 But the necessity of a revival movement demonstrates that the Iron Foundry's early renown had not translated into canonicity. The work was to some extent a victim of its own success. By the end of the 1930s, its novelty had been blunted by ubiquity; even humour based on repetition can only bear being repeated so many times. Meanwhile, Shostakovich's international breakthroughs were broadening ideas about the possibilities of Soviet music.Footnote 128

Perhaps more crucially, the heyday of machine-age comedy was drawing to a close. As film studios reorganized themselves around the possibilities of synchronized sound, the reflexive concern with mechanized movement so prominent in silent cinema was overtaken by other priorities.Footnote 129 And as everyday experiences of technology such as filmgoing changed, so, too, did the symbol of ‘the machine’. In his description of the 1920s machine aesthetic, the architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson provides, in effect, a recipe for the Mosolovian mass ornament: begin from a ‘perception of the machine as a combination of parts – gears, cams, axles’, and then arrange these ‘simple geometrical elements’ into ‘complex patterns’.Footnote 130 Especially after 1930, this ‘machine-as-parts syndrome’ gave way, by Wilson's account, to various kinds of black-boxing: neoclassical purity, streamlined forms, biomorphic design.Footnote 131

With this shift, Mosolov started to suffer the same fate as Marcel Poot in 1930: he sounded embarrassingly outdated. In 1934, Constant Lambert derided works such as the Iron Foundry and Pacific 231, predicting:

The present vogue for mechanical romanticism, being based primarily on the picturesque aspects of machinery, is bound to disappear as the mechanic more and more comes to resemble the bank clerk, and as the Turneresque steam engine gives way to the unphotogenic electric train. It is only comparatively primitive machinery that affords a stimulus, and there is already a faint period touch about Pacific 231 and Le Pas d'Acier.Footnote 132

For Lambert, new kinds of machines were superseding the propinquity of high technology and the ‘primitive’ that the Iron Foundry's musical language denoted. By the end of the 1930s, other critics also came to consider Mosolov's ‘painful realism … as old-fashioned as a 1922 fox-trot’.Footnote 133 The Iron Foundry had become obsolete.Footnote 134 Despite the work's immediate popularity, this outcome was hardly unexpected. Indeed, it was arguably because Mosolov's success had always seemed so likely to be short-lived that mainstream concert institutions could accommodate, and then discard, the Iron Foundry without compromising on their dominant museum function. Safely marginalized as a gimmick with a temporary shelf life, the work served above all as an entertaining novelty item: a refreshing diversion from the established canon, but not a fundamental augmentation or challenge to it.

The decline of mimetic mechanicity coincided with major shifts in both international relations and public attitudes towards internationalism. The economic and political crises of the 1930s severely undermined the claim that technological progress would unite the world in peace and prosperity. The intuition that the citizens of ‘modern’ states shared much the same historical trajectory and sensory experiences – an intuition essential to and reinforced by the extensive dissemination of machine aesthetics – was confronted with the hard reality of ideological and military conflict. The internationalist strain in popular culture survived these and further dislocations, but not without a change in emphasis. During the Second World War and the early Cold War, Hollywood sought to educate its audiences in their imagined new attachments and responsibilities as global citizens by projecting a sentimental ideal of shared humanity transcending cultural and racial difference: an internationalism centring more on sympathy for suffering children than wonder at industrial machines.Footnote 135 In this new world, the configuration of aesthetic practices, media techniques, and narratives of modernity that had sustained interwar machine aesthetics as a mode of vernacular internationalism definitively unravelled. By mid-century, there was little appetite or opportunity anywhere to preserve the memory of the Iron Foundry's astonishing, if ultimately ephemeral, success.