The COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing protocols aimed to slow its transmission are having severe mental health consequences (Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Webster, Smith, Woodland, Wessely, Greenberg and Rubin2020; Ebrahimi, Hoffart, & Johnson, Reference Ebrahimi, Hoffart and Johnson2021; Hoffart, Johnson, & Ebrahimi, Reference Hoffart, Johnson and Ebrahimi2020; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, O'Connor, Perry, Tracey, Wessely, Arseneault and Bullmore2020; Prati & Mancini, Reference Prati and Mancini2021; Salari et al., Reference Salari, Hosseinian-Far, Jalali, Vaisi-Raygani, Rasoulpoor, Mohammadi and Khaledi-Paveh2020; Xiong et al., Reference Xiong, Lipsitz, Nasri, Lui, Gill, Phan and McIntyre2020). Depending on peoples' typical ways of reacting to stressful circumstances, the pandemic will probably produce different mental health consequences. Among factors likely central to the exacerbation and persistence of psychological symptoms, personality-based processes such as difficulties in the experience and regulation of emotion (Solbakken, Hansen, & Monsen, Reference Solbakken, Hansen and Monsen2011) and severity of interpersonal problems (Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins, & Pincus, Reference Horowitz, Alden, Wiggins and Pincus2000) are particularly salient candidates. Both factors are likely to be impacted by the pandemic and amelioration measures of societal lock-down and social distancing. As amelioration measures in turn are relaxed, this impact may presumably diminish, gradually returning these factors to pre-crisis levels. Difficulties in emotion regulation and interpersonal problems are, in turn, likely to predict symptoms of depression and anxiety throughout the pandemic and beyond, and early levels of these factors will presumably predict later developments in symptom status. Similarly, reductions in emotion regulation- and interpersonal difficulties during various phases of the outbreak will presumably coincide with reductions in psychological symptoms. Thus, emotion regulation difficulties and interpersonal problems are likely to be systematically predictive of the course of mental health problems during the pandemic.

In order to investigate this issue, we conducted an internet-based survey with 10 061 responders at time 1 (T1 – a period of strict social distancing protocols) and 4936 (49.1%) at time 2 (T2 – a period when the majority of distancing protocols were discontinued). We specifically investigated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): We postulate a significant decrease in emotion-regulation difficulties and interpersonal problems from T1 to T2.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): We postulate that the T1-level and changes from T1 to T2 in emotion-regulation difficulties and interpersonal problems will predict changes from T1 to T2 in anxiety and depression during the pandemic above and beyond other relevant factors such as age, gender, and education.

In terms of methodology, the study was a longitudinal, internet-based observational survey of the general adult Norwegian population during the COVID-19 pandemic with 10 061 responders at the height of lock-down (T1). After social distancing measures had been eased (T2), 4936 responders completed the survey again. Emotion regulation difficulties were assessed by a subset of items from the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS). Interpersonal problems were assessed by a subset of items from the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-64 (IIP). Symptoms of depression were assessed by The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Symptoms of anxiety were assessed by The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Statistical analyses were performed by hierarchical linear mixed models (see online Supplementary materials for details).

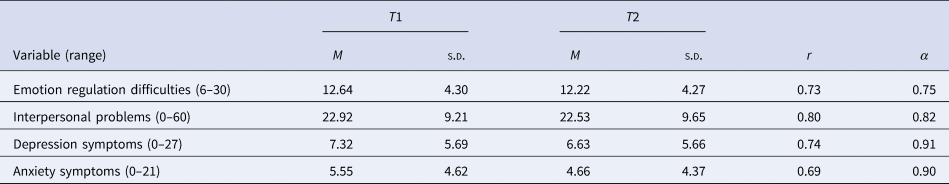

See Table 1 for sample characteristics at T1/T2. Descriptive statistics for predictor and outcome variables at T1/T2 are displayed in Table 2. Models testing H1 showed significant time effects for emotion regulation difficulties, interpersonal problems, anxiety, and depression (see Table 3). Figure 1 displays the effect sizes of changes.

Fig. 1. Effect sizes of changes from T1 to T2 in anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, emotion regulation difficulties, and interpersonal problems. Note. T1 = a period of 1 week (31st March to 7th April 2020) starting nearly 3 weeks after the implementation of strict social distancing protocols in Norway (12th March 2020). T2 = a period of 3 weeks (22nd June to 13th July 2020) starting 1 week after the strict social distancing protocols had been discontinued (15th June 2020). d = Cohen's d.

Table 1. Demographic and social variables for the original sample at T1 and for the completer sample at T2

Note. T1 = a period of 1 week (31st March to 7th April 2020) starting nearly 3 weeks after the implementation of strict social distancing protocols in Norway (12th March 2020). T2 = a period of 3 weeks (22nd June to 13th July 2020) starting 1 week after the strict social distancing protocols had been discontinued (15th June 2020).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the predictor and outcome variables across time

Note. T1 = a period of 1 week (31st March to 7th April 2020) starting nearly 3 weeks after the implementation of strict social distancing protocols in Norway (12th March 2020). T2 = a period of 3 weeks (22nd June to 13th July 2020) starting 1 week after the strict social distancing protocols had been discontinued (15th June 2020).

r = Pearson's r; d = Cohen's d; α = Cronbach's α.

Table 3. Fixed effects estimates (top) and variance-covariance estimates (bottom) for multilevel models of difficulties in emotion regulation, interpersonal problems, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms from T1 to T2

DERS, difficulties in emotion regulation; IIP, overall interpersonal problems; PHQ-9, symptoms of depression; GAD-7, symptoms of anxiety; AIC, Akaike's information criterion.

Note. Standard errors are given in parenthesis. Estimations were performed by the method of maximum likelihood (ML). *p < 0.01. Tot = total residual in models with homoscedastic error covariance structures. T1 = a period of 1 week (31st March to 7th April 2020) starting nearly 3 weeks after the implementation of strict social distancing protocols in Norway (12th March 2020). T2 = a period of 3 weeks (22nd June to 13th July 2020) starting 1 week after the strict social distancing protocols had been discontinued (15th June 2020).

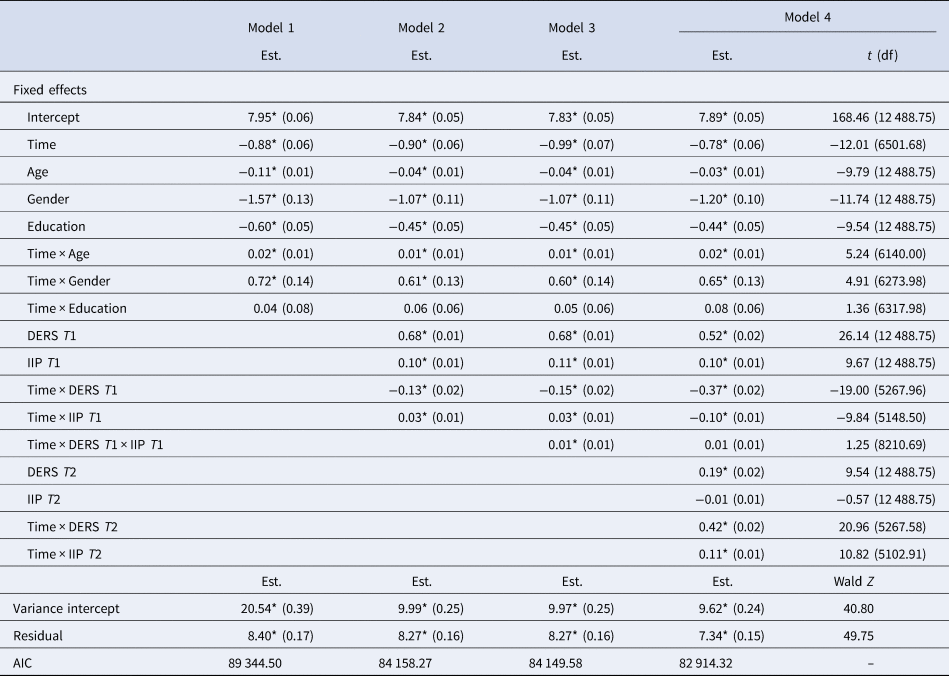

Models testing H2 are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Addition of demographic variables and their interactions with time (model 1) showed that males, older persons, and the highly educated had lower depression at T1, males and older persons reported smaller reductions to T2. Similarly, males, older persons, and the highly educated had lower anxiety at T1, and males reported smaller reductions to T2.

Table 4. Fixed effects estimates (top) and variance-covariance estimates (bottom) for predictive multilevel models of depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) from T1 to T2

DERS, difficulties in emotion regulation; IIP, overall interpersonal problems; AIC, Akaike's information criterion.

Note. Standard errors and degrees of freedom are given in parenthesis. Estimations were performed by the method of maximum likelihood (ML) and with a homoscedastic error covariance structure. *p < 0.01. T1 = a period of 1 week (31st March to 7th April 2020) starting nearly 3 weeks after the implementation of strict social distancing protocols in Norway (12th March 2020). T2 = a period of three weeks (22nd June to 13th July 2020) starting 1 week after the strict social distancing protocols had been discontinued (15th June 2020). Degrees of freedom (df), t values, and Wald Z are given only for the final model.

Table 5. Fixed effects estimates (top) and variance-covariance estimates (bottom) for predictive multilevel models of anxiety symptoms (GAD-7) from T1 to T2

DERS, difficulties in emotion regulation; IIP, overall interpersonal problems; AIC, Akaike's information criterion.

Note. Standard errors and degrees of freedom are given in parenthesis. Estimations were performed by the method of maximum likelihood (ML) and a heteroskedastic error covariance structure. *p < 0.01. T1 = a period of 1 week (31st March to 7th April 2020) starting nearly 3 weeks after the implementation of strict social distancing protocols in Norway (12th March 2020). T2 = a period of 3 weeks (22nd June to 13th July 2020) starting 1 week after the strict social distancing protocols had been discontinued (15th June 2020). Degrees of freedom (df), t values, and Wald Z are given only for the final model.

The addition of initial emotion regulation difficulties, interpersonal problems, and interactions with time (model 2), showed that greater problem load in both domains was associated with more extensive anxiety and depression at T1. More extensive emotion regulation difficulties at T1 predicted greater reductions in both symptom domains, more extensive interpersonal problems did not.

Addition of three-way interactions between emotion regulation difficulties, interpersonal problems, and time (model 3), indicated that the effect of initial emotion regulation difficulties on symptom reduction was dependent on the level of interpersonal problems: more pervasive interpersonal problems reversed the effect of emotion regulation difficulties on symptom development.

The final step, adding T2 levels of the predictors (model 4) and their respective interactions with time, demonstrated that reductions in the predictor variables across time were strongly associated with reductions in symptoms.

Problem load in all of the examined domains was significantly reduced, but with minor effect sizes. Thus, vaccination, mass immunity, and subsequent return to normal daily life may not in and of themselves lead to the desired rapid improvement of mental health in the population. As expected, greater problem load in both predictor domains was associated with more anxiety- and depressive symptoms across time. Improvements in predictor domains were associated with symptom reduction. Thus, focused interventions that target these processes may help remediate the mental health strain of COVID-19.

Contrary to hypothesis, more extensive emotion regulation difficulties initially predicted greater symptom reduction, whereas the opposite was true for interpersonal problems. Thus, participants with more extensive emotion regulation difficulties became more similar to average responders in symptoms from T1 to T2, whereas those with more severe interpersonal problems became further removed from the average. We may speculate that those having greater difficulties tolerating unpleasant emotions were more negatively affected by the onset of the pandemic, and also experienced more relief when emotional pressures associated with COVID-19 somewhat dissipated with easing of social distancing protocols. Similarly, the negative effect of interpersonal problems on symptom improvement is meaningful, as entrenched, maladaptive interpersonal strategies presumably hinder constructive use of social contacts in the service of improving one's situation as social distancing was eased. These propositions are also consistent with the interaction between emotion regulation difficulties and interpersonal problems. In this case, additional relief afforded by reduced emotional pressure through eased amelioration measures for responders with low tolerance for emotions was offset by the presence of persistent maladaptive relational strategies. Our results suggest that poor tolerance of emotions and maladaptive relational strategies are targets of intervention worth pursuing for alleviating anxiety and depression during the pandemic.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001987.

Financial support

The study was in its entirety funded internally by the University of Oslo, Norway.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.