Introduction

In 1843, Allan Pinkerton moved from Scotland to Kane County, Illinois, a world where law and order was enforced by the efforts of private individuals. Early nineteenth-century officers of the peace were not a professional class of violence experts, but ordinary male citizens, often serving as temporary deputies. Even sheriffs and constables, the key officers of the peace in counties and towns, respectively, were simply local notables who earned fees rather than a salary and whose capacity to carry out arrests was based on their authority to call on the aid of residents as a posse comitatus (Karraker Reference Karraker1930). Each aspect of the criminal law enforcement process during this period—arresting suspects, prosecution, and holding trial—depended on this everyday form of mobilization (Steinberg Reference Steinberg1989).

Thus, although a simple cooper, when Pinkerton inadvertently stumbled on a counterfeiting operation hidden in a thicket in 1847, it seemed natural that he would return with Sheriff Noah Spaulding and aid in the arrest of the criminals as a deputy.Footnote 1 Pinkerton acted as most anyone in frontier Illinois would—under the republican assumption that private individuals had civic responsibilities.

At the same time, Pinkerton's experience awakened his keen entrepreneurial senses. H. E. Hunt and I. C. Bosworth, both well-known members of the Kane business community, asked Pinkerton to help continue the fight against local counterfeiters (presumably offering him some sort of pecuniary compensation), while an appointment as deputy sheriff under Spaulding's successor, Luther Dearborn, helped Pinkerton build a local reputation as someone with investigative talents. By the early 1850s, policing became a full-time occupation for Pinkerton. He moved to Chicago (still a raw frontier town), became a Deputy Sheriff in Cook County under Cyrus Bradley, and worked with the US Treasury to uncover postal fraud and to investigate counterfeiting cases. It was a short step from these activities to the creation of his own agency of private investigators, which could manage the increasing demand from both municipal governments and firms for detective services in Chicago. Although Pinkerton's agency was the most famous of the new detective service firms, others could be found in New York, Philadelphia, London, and elsewhere by the mid-1850s (Johnson Reference Johnson1979, 59–64).

The new private detective agencies were not the only changes in the provision of security at the time. Indeed, almost concurrent with the founding of the Pinkerton Agency, the Common Council of Chicago initiated a series of important reforms in law enforcement. In the early 1850s, the city's Common Council followed other large US cities at the time by creating a salaried and full-time police force made up of professional law enforcement officers. Indeed, by the late 1860s, a dual and complementary system of public and private policing—in which private guards largely cooperated with and possessed legal authority alongside permanent and bureaucratized police departments—was commonplace in the urban United States (Johnson Reference Johnson1979, 60; Walton Reference Walton2015, 14–15).

Why did both the private security industry and the municipal bureaucratic police emerge when they did? And why did they ultimately evolve together? This article focuses on Chicago to show that public and private police both arose from the breakdown of the existing republican system in which the provision of public law enforcement was secured by delegation to smaller communities organized through personalistic ties. The growth in anonymity and the politicization of ethnicity in the early 1850s undermined this older system and created a perception of public security threat that, exacerbated by media sensationalism, implied that delegation no longer worked. In response, elites continued to rely on practices like special deputization, through which official police authority could be granted to private individuals for a limited place and time. Because the social structural foundations of delegation had changed, however, the use of deputization transformed municipal and private governance, creating in the process a class of specialists who had moved easily between public and private policing roles. Over time, these networks among security providers helped lock in the dual public and private system, a process that occurred in Chicago and beyond.

To establish these claims, this article first presents the republican conception of delegated policing in early nineteenth-century cities, focusing on the ways social control was outsourced to smaller subcommunities within the municipality. It then demonstrates how this system broke apart by looking at how the growth of social and physical mobility and the politicization of ethnicity changed the way threat was perceived and managed. Next, it explores the coevolution of police and private security institutions in antebellum Chicago by examining how state and economic elites transformed the constabulary by continuing to use it in conditions that had changed. The net result was the gradual reorganization of networks among public and private providers of security and the institutionalization of a dual system of public and private law enforcement.

Republican Security, Police Power, and Delegation in the Nineteenth-Century American City

The creation of the “new police” in the United States and Europe—the system of full-time professionals housed in permanent municipal and state departments and private security firms, which most scholars date to the years between 1820 and 1870—is usually attributed to what Allan Silver (Reference Silver and Bordua1967) calls a rising “demand for order in civil society.” Early policing history emphasized that this demand, the product of changing class relations and a new industrial economy in which property protection became key, allowed the state to intervene in what had previously been private conflicts (Critchley Reference Critchley1970). Approaches to state formation in the 1980s and 1990s, in turn, often viewed the emergence of the salaried police force in Europe as a marquee example of the monopolization of violence and treated police as part and parcel of the growth of the autonomous state (Tilly Reference Tilly1990, 115; Mann Reference Mann1993, 403–12).

In assessing the cases of the United States and, to a lesser extent, England, however, scholars have since challenged this thesis.Footnote 2 Not only did the state fail to monopolize violence through the organization of police forces, it often did not even attempt to do so (Johnson Reference Johnson1981, 55–64). Instead, in these settings the republican tradition of fusing public security to private interest provided avenues for ordinary people to continue to retain important controls over the use of violence. This included not only a vision of a well-armed populace capable of defending itself (Williams Reference Williams1991), but also the involvement of private societies and “vigilance” associations in the monitoring and policing of public order (Fronc Reference Fronc2009; Szymanski Reference Szymanski2005).

Civic republican thought, highly influential in England and the United States beginning in the seventeenth century, held that the pursuit of private individual freedom depended on a public community of shared interest; conversely, public freedom was inextricable from the quality and esteem of virtuous private individuals (Skinner Reference Skinner, Bock, Skinner and Viroli1990). Public goods like security were thus the product of participation of citizens rather than professional expertise or bureaucratic specialization (Cress Reference Cress1981). The hope was that the direct participation of male property holders in their own protection could avoid the political despotism that might result from having a standing army, since leaders would be unable to use force that was considered illegitimate (Schwoerer Reference Schwoerer1974).Footnote 3 From the outset, the central state's ability to use violence depended on coordinating efforts among private volunteers and citizens, creating a fragmented, flexible system in which a professional security bureaucracy was largely considered anathema.

This did not, however, imply that the capacity to mobilize force in the United States was weak or inadequate. Indeed, as William Novak (Reference Novak1996) has demonstrated, the American state in the early nineteenth century possessed tremendous power to regulate the life of its citizens. For instance, Chicago's 1837 municipal charter—not unusual for the time—included ninety-two separate sections with regulations covering a huge swath of behavior, including market regulations, storage of firewood, use of guns, use of streets and public spaces, and provision for schooling and other services (James Reference James1898−1899).

What cities lacked were bureaucratic entities to mobilize enforcement of these rules.Footnote 4 Constables, sheriffs, and deputies of various kinds, who worked for fees and rewards rather than for a salary, responded to violations in response to local complaints (Lane Reference Lane1967, 8–13). Such officers rarely possessed any particular skills in violence and relied on their personal connections and social standing to prosecute arrests successfully (Kent Reference Kent1986, 30–31). Instead of a large, permanent force, city governments opted to depute or deputize regular citizens to serve in posses or to aid officers of the peace, in addition to appointing a night watch comprised of amateurs to monitor city streets (Lane Reference Lane1967, 10–11).

By the early 1830s, this began to change, as larger municipalities started experimenting with salaried, full-time police forces. Many of these experiments—particularly in northern cities such as Boston and New York—were inspired by London's adoption of a permanent policing organization in 1829 (Lane Reference Lane1967). Others, in southern towns like New Orleans and Charleston, created aggressive quasi-professional policing agencies to monitor and patrol slaves (Rousey Reference Rousey1996; Hadden Reference Hadden2001). By the Civil War, the largest US cities had reorganized policing infrastructure to include salaried and permanent patrol officers, while many others would do so in the following decades.

In explaining these changes, many scholars continue to rely on the demand for social order as the key explanatory framework. For example, many emphasize that the turn to bureaucratic police often accompanied critical junctures like crime waves, ethnic riots, or party conflict (Johnson Reference Johnson1979; Mitrani Reference Mitrani2013), while others turn to longer-term processes like class conflict or modernization to explain the profusion of police reform in the mid-nineteenth century (Monkkonen Reference Monkkonen1981; Harring Reference Harring1983). As such, the emphasis in most accounts of both the US and the English experience is on the ways this demand for policing engendered new organizational forms rather than reflecting traditional practices.Footnote 5

The primary aim of this article is to shift the gaze and explore how a supply of social order—the existing institutional apparatus dedicated to organizing and producing coercion—constrained and shaped the development of new municipal police and private alternatives. Of course, this is not to dispute the importance of the demands identified by Silver and others; indeed, riots, property crime, and anonymity mattered precisely because they created at least the perception of novel threats, to which elites and practitioners alike had to respond. But the efforts at reform such threats provoked were filtered through a well-developed system that structured the way decision makers understood the problem in front of them.

In particular, focusing on the existing supply of order helps make sense of the ways that public and private forms of law enforcement coevolved. As shown below, the delegation system in municipal governance devolved policing responsibilities to local communities, many of which were culturally homogeneous, but economically stratified. This system worked because of the close relationship between institutional rules—the abstract precepts of government, which assumed that private individuals would secure the public interest—and the concrete, day-to-day forms of social authority in personal networks that actually helped to prop up participation in public service. Such positive feedback between these abstract rules and day-to-day networks is often an important source of social order (Sewell Reference Sewell2005, 339–51; Padgett and Powell Reference Padgett and Powell2012, 5).

This republican system of delegating policing, however, was subject to a series of long-term threats related to increases in mobility (which undermined the capacity for personal ties to mobilize sanctions) and the politicization of ethnicity in the early 1850s (which made ethnicity, one of the key building blocks of delegation in the city, a double-edged sword). As a result, the social contexts underlying delegation had changed, cutting off the capacity for local neighborhoods to police themselves reliably. The broken link between the rules of the municipal government and day-to-day social relations opened up a rupture in social order, undermining the positive feedback that helped sustain the earlier fusion of public security and private interest.

In response, however, decision makers and law officers did not try to innovate, but turned to the techniques they already knew. This is largely because these actors already benefited from the existing system and had no wish to create a powerful new bureaucracy that might threaten their political and economic power. But it was also because, as with most decision makers, they interpreted new threats using existing cultural schemas (Douglas and Wildavsky Reference Douglas and Aaron1983). By turning to the existing technique of special deputization, decision makers could simultaneously maintain control while flexibly allowing a variety of public and private organizations to gain policing authority. While specific events like riots and crises precipitated political action, in general elites tried to conserve continuity, and organizational innovation usually involved conservative rather than transformative change.

In the case of Chicago, because the turn to traditional forms of deputization was no longer rooted in delegation, its use extended policing authority in two new directions. On the one hand, it allowed city officials to convert the fee-based, part-time constable and watch system into a permanent municipal police force. Although this outcome was not necessarily the intent of early reformers, who were much more concerned with preserving existing law enforcement options, the public use of deputization ultimately grounded the police on a new bureaucratic and professional logic. For actors like Allan Pinkerton, on the other hand, special deputization provided entrepreneurial options, allowing them to convert their expertise into a service they could market to economic firms. This also, of course, made the boundaries between public and private policing porous; public officers who lost their jobs in municipal regime turnovers could move into the private sector, while private guards and detectives provided a pool for municipal police chiefs to draw on when staffing their departments.

Over time, the networks among these public and private officials helped lock in the new system of public and private police. Public police, still accustomed to the system of service for fees, did not see any contradiction in pursuing private security opportunities, while private detectives and guards saw their own profit-making activities as contributing to the public interest. In other words, what began as a conservative use of a traditional institutional principle led to inadvertent effects, transforming existing institutions into novel organizational forms.

Moreover, these changes were not unique to Chicago; indeed, similar threats associated with mobility and ethnic politicization threatened the operation of republican delegation throughout the United States and abroad at the same time (Ryan Reference Ryan1997, 124–31). Thus, while ideas about police, private security, and municipal reform did diffuse from city to city in the mid-nineteenth century (Monkkonen Reference Monkkonen1981, 49–64), changes in the organization of policing invariably involved local adaptations, often in response to the collapse of delegation. National trends, in other words, always had to be translated into local terms.

The supply-based framework therefore builds on and refines existing demand for order approaches, while also laying bare the close interdependence of public police departments with private alternatives. As the next section demonstrates, the tradition of private actors taking on key responsibilities for public policing in antebellum Chicago through the delegation of law enforcement to ethnic elites provided the raw materials out of which both the municipal and private police would emerge.

Exploring the Logic of Policing Evolution

Antebellum Chicago's municipal government resembled that of other cities. As in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, enforcement of these provisions lay in part with the aldermen and mayor themselves, as well as with officers they would appoint (James Reference James1898−1899, 155). A “high constable” was elected in addition to the mayor, who was granted the same responsibilities as a sheriff within the city limits; both this official and the council could appoint city constables and deputy constables to aid in the collection of fines and the enforcing of various regulations (James Reference James1898−1899, 40, 70–71).Footnote 6 The council occasionally appointed seasonal forces of night watchmen and even authorized construction of a Watch House in 1845, but such expenditures were contingent on momentary outbreaks of disorder and did not reflect a continued commitment of the city to the creation of a full-time staff of policemen.Footnote 7 The entire police force of Chicago in 1850 (in which the city's population hit 30,000), consisting of elected constables, a city marshal, a small, quasi-permanent night watch, and the sheriff and his deputies, was made up of at most twenty individuals.

As Robin Einhorn (Reference Einhorn1991, 99–103) has demonstrated, municipal politics in early Chicago were organized or “segmented” jurisdictionally to preclude redistribution and to deflect political conflict among social classes, thereby preserving the republican goals of minimal cost and bureaucracy. In essence, this meant that ward boundaries in the city were divided in such a way as to allow property-holding elites to control their own districts and only to pay for infrastructure in areas that affected them directly. There was, in other words, no unitary public interest, only a collection of private individuals responsible for administering their own communities.

The abstract institutional rules associated with the constable/watch system were grounded in this politics of segmentation, which likewise delegated enforcement responsibility onto local neighborhoods. As long as the social preconditions for this system were in place—the capacity for local elites in neighborhoods to exercise social control by using informal sanctions through personal networks—the institutional rules of the republican system were reproduced in day-to-day life and vice versa.

Delegating Policing in Practice

How, though, did delegation in the early nineteenth century actually work on the ground? It depended, fundamentally, on two components.

First, there was an interconnected core of political elites who occupied the key roles within the main city administration and who appointed and approved a small staff of constables. Second were the presence of culturally homogeneous and economically heterogeneous neighborhoods, in which ethnic boundaries provided a means for ensuring control by local notables. I address each in turn.

Elite Cohesion and Politics in Chicago

Chicago's municipal administration in the 1840s and 1850s was dominated by old Yankee residents who used close personal connections and economic power to help dominate the Common Council. These connections—often forged among the oldest settlers to the city, many from New York and Massachusetts, in the 1830s—allowed them to tamp down on partisan animosity, keeping spending low, while outsourcing actual city services to local neighborhoods (Einhorn Reference Einhorn1991, 39–42).

Political elites were tightly connected to one another. Data from Andreas's (Reference Andreas1884) encyclopedic history of the early city, for instance, demonstrate that the first seventeen mayors of the city (who served from 1837–1859) shared an average of over five organizational affiliations with each other, indicating that the political elite of the city was socially cohesive. Moreover, the city's elite shared close business and familial relationships; in 1863, when the population of the city was over 150,000, for example, almost 23 percent of the residents in Chicago who made $10,000 annually were related to one another (Jaher Reference Jaher1982, 495), while a large number of these were deeply involved in politics (Bradley and Zald Reference Bradley and Zald1965).

These overlapping contacts facilitated the creation of a relatively closed class of political elites, one that was primarily interested in managing its own affairs, keeping costs low, and relying on others to implement municipal policies. In this sense, they preserved a republican ethos of virtue and frugality, as well as promoting a logic of self-governance. A number of these elites did engage in a kind of noblesse oblige, taking a personal role in helping create emigrant aid societies and social service infrastructure on behalf of the burgeoning immigrant population, many of whom possessed very limited resources and language skills (McCarthy Reference McCarthy1982).

For the most part, however, the insulation of elites in the Common Council from the life of those subject to municipal regulations also made them disinclined to administer law enforcement directly through a centrally directed police force, leaving it instead to neighborhood constables.

Cultural Ties, Neighborhoods, and Delegation

Dense social networks and locally powerful actors in neighborhoods helped manage this system on the ground. In Chicago in the 1830s through early 1850s, many residential areas contained local notables with deep cultural ties to their neighbors, allowing for the provision of law and order without municipal interference (Pierce Reference Pierce1937, 179–86).

This was largely a product of settlement patterns in the early city. Many of Chicago's arrivals moved into areas where they could reproduce their traditional cultural practices without too much external interference (Palmer Reference Palmer1932, 110–18). This was particularly true for non-English-speaking immigrants. In his study of Swedish immigration to Chicago, for instance, Ulf Beijbom (Reference Beijbom1971, 58–62) shows how most settlers prior to 1850 selected homes that, though nestled in a primarily Irish area, nevertheless were within close spatial proximity to St. Ansgarius, the Swedish Lutheran Church. This provided both a focal point for the religious livelihoods of Swedes in Chicago and a means of establishing moral regulation of their day-to-day lives in a strange city. In these areas, wealthy, connected neighborhood leaders acted like patrons, managing what they saw as their populations while participating in the larger strategy of jurisdictional segmentation (Einhorn Reference Einhorn1991, 38–39). Keeping a small police force in the midst of a hands-off city council depended on precisely this kind of local control.Footnote 8

Delegated policing, then, largely meant that the authority of law enforcement was sustained by local elites and their connections rather than by a large bureaucracy. City elders, in turn, made regulations and dominated central municipal government through tight, enclosed social networks. Although in other, more established cities like New York and Boston, the reliance on specifically ethnic self-management was not always as profound as it was in Chicago, government in most antebellum municipalities similarly funneled a large amount of decision making over matters of public life downward to locally embedded elites and their personal networks; delegation was the norm rather than the exception (Ryan Reference Ryan1997, 78–94).

How Delegated Policing Decomposed

By 1850s, however, the social structural foundations of delegation were eroding. Two such changes—the growth of anonymity and mobility and the politicization of ethnicity—undermined the link between institutional rules of municipal government and day-to-day social authority and created new categories of threats with which political and economic elites had to reckon.

Anonymity and mobility, in particular, were highly dangerous to this link. Not only was there no guarantee that local actors would take the responsibility for countering threats from those with whom they shared no kinship or social ties, but it was also difficult to link private interests clearly to the pursuit of public welfare in a context where the boundaries of the community itself were called into question. As a result, certain public zones in the city, marked by high levels of social ambiguity and anonymity, could pose a significant challenge to the system of delegating security to local neighborhoods.

There were two causes of this shift: the dramatic increase in the population of the city and the rise of the railroad. The first presented what Lyn Lofland (Reference Lofland1973, 8–23) has termed a transformation from personal knowledge as a way of managing social relationships to one in which social categories were key. Personal knowledge allows for members of a community to have individualized information to help monitor and sanction one another. A shift to a system of social order based on categories, on the other hand, occurs once communities grow to the point at which it is impossible to be aware of the reputations of most fellow inhabitants. In these communities, categories provide heuristics to classify individuals into subgroups (“homeless,” “well-to-do,” etc.) and allow people to order their interactions even as they lack personal knowledge of one another.

Between 1840 and 1855, the population of Chicago increased from approximately 4,500—a village world marked by personal knowledge—to a large, urban center of over 80,000 residents. Although many of these new immigrants moved into ethnic neighborhoods, a large number did not, complicating the capacity for cultural ties to serve as a form of social discipline (Palmer Reference Palmer1932, 31–33). In addition to huge numbers of Irish and Germans, Scandinavians, Eastern Europeans, Southern Europeans, and others began to immigrate in increasing numbers, rendering the ethnic fabric of the city much more complex (Pierce Reference Pierce1937, 179–83). Moving from personal knowledge of individuals to a world of social categories meant that ethnicity became more important as a marker for social and political position, just as clear ethnic boundaries became more difficult to sustain.

Compounding the problems of population growth was the second shift of the railroad, which transformed Chicago almost overnight from a preindustrial urban center to an industrial one. Beginning in the early 1840s, the city's unique geographical location had allowed it to become a focal point in the burgeoning agricultural transport system linking the Western frontier to Eastern markets. Between 1848 and 1854, rail was added to the canal, river, and lake traffic, which made Chicago a uniquely vibrant trading center, and by the mid-1850s, the city sat at the center of one of the most comprehensive rail networks in the world, with an explosion of depots scattered throughout the city and train lines running both East-West and North-South (Cronon Reference Cronon1992, 66–74).

The physical mobility attending the railroad similarly undermined the link between authoritative social ties and delegation, since places of intermixing began to emerge that were populated by strangers who, by definition, possessed no such ties (Hoyt Reference Hoyt1933, 61–63; Schneider Reference Schneider1980, 14–26). Depots, for instance, not only were places of market exchange and commodity trading, but also brought strangers and visitors into the city in unprecedented numbers (Duis Reference Duis1998, 16–17). The combination, then, of two transformations—from a world in which personal knowledge was sufficient to manage social relationships to one marked by strangers, and the growth of an industrial system that created specific economically important zones of mobility and fluidity—utterly upended the social conditions upon which the republican system of delegation rested. While Chicago was a particularly extreme example, other cities in the United States and abroad confronted dilemmas of anonymity and public mixing in the 1850s (Frink Reference Frink2010).

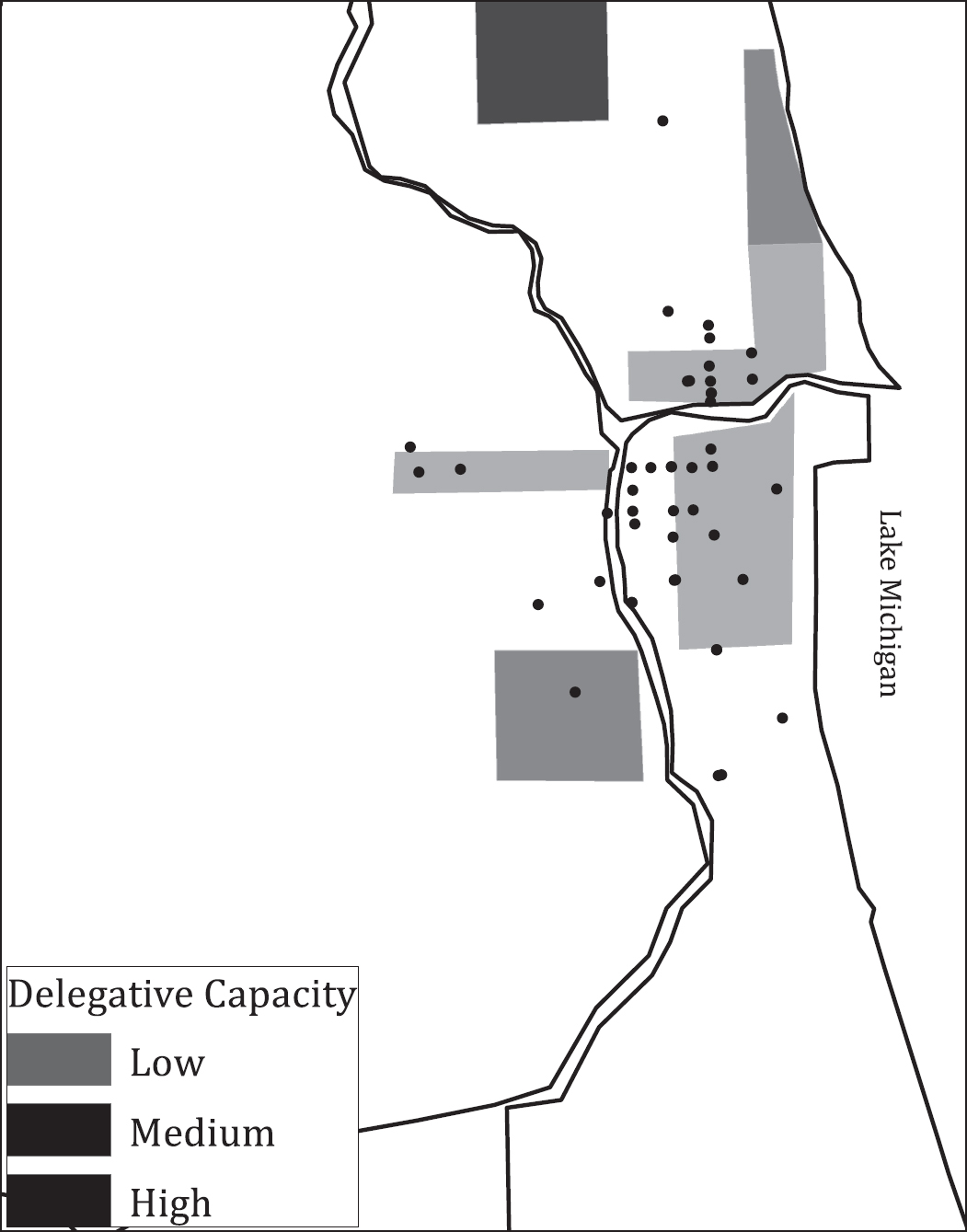

Before examining how these changes affected the discourse of threat in Chicago, however, it is necessary to analyze empirically the impact of these processes on social networks. To do so, I used a demographic sample of over 1,800 Chicago residents in 1855 to develop a measure of how capable each neighborhood in the sample was of policing itself. For reasons of space, the sampling strategy used and design of this delegative capacity index is described in an online appendix.

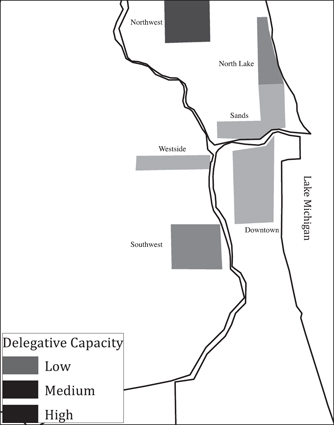

Figure 1 maps this measure of delegative capacity onto the city's spatial organization in 1855. The darker the area sampled, the more economically stratified and culturally similar the personal networks of those living in those areas and the more capable they were of policing themselves. As the map demonstrates, stark differences were emerging in delegative capacity across the city. The urban core was densely populated, highly diverse, and increasingly anonymous, while some outlying areas continued to feature the kinds of social networks we would associate with self-policing. On the whole, by 1855, the city was undergoing a transition from being composed of an archipelago of little culturally homogeneous and economically diverse security islands to a mixed zone of some highly isolated and insulated communities (the Northwest, which was known as Little Germany) and other, deeply mixed areas (the Sands, which was known as a notorious vice district).

Figure 1 Delegative Capacity in Select Neighborhoods (1855–1856)*

*Divisions between levels are based on natural breaks (Jenks).

Changes in Threat in the City

What were the effects of the loss of delegative capacity and the growth of anonymous public places? In Chicago, as elsewhere, the most immediate change was that, by the late 1840s, residents began to perceive new kinds of threats to the social order.

This took several forms. First, they increasingly discussed the presence of strangers in the city, the growth of traffic on city streets, and the creation of a sense of anonymity and bustle. “Look at the arrivals in our hotels from day to day, and the places from which they come,” wrote the Chicago Daily Democratic Press (1853), “and you will be astonished at the multitude of people that are constantly in motion.” While Chicago boosters actively courted the economic traveler and investor, the papers also noted an increase in the number of “rogues” interspersed among the crowds; newspaper accounts (Chicago Daily Democratic Press 1853a, 1853c) began to note how horse thieves and counterfeiters could quickly adopt a complex series of pseudonyms and exploit relatively new forms of evading local law enforcement by taking advantage of the anonymity afforded by the growing city (Halttunen Reference Halttunen1982, 20).

Second, and related, the issue of security for Chicago became intertwined with a threat to transportation, the lifeblood of its economy. Not only were rogues and villains able to use transportation infrastructure to avoid local punishments, but also, more importantly from the standpoint of town boosters, business travelers were often confronted by con men, corrupt cab drivers, and hotel thieves who preyed on the tourist infrastructure developing in the city (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2009, 18–36, 67–76, 137–60). Strangers to the city were not always considered dangerous, but they were often seen as vulnerable (Richter Reference Richter2005, 20–25). As the Tribune (June 26, 1854, quoted in Einhorn Reference Einhorn1991, 148) pointed out, wealthy guests in a growing city like Chicago would expect “to conduct their deliberations unmolested by unauthorized visitors, and to receive those civilities for the transaction of their business, for which other cities have been so justly praised.”

The threat posed by and to strangers in public places represented an important shift in how residents of cities thought about disorder (Keller Reference Keller2009, 8–11). For example, in the 1840s the papers only rarely covered crime in Chicago itself. In part, perhaps, this was because actual levels of crime were low, but it was also likely due to the fact that the enforcement of criminal laws rarely called for intervention on the part of the city constabulary. For example, I examined a sample of seventy-six issues of the Chicago Daily Journal from January 1 to March 31 in 1845, a year the population of the city reached 12,000. In total, not counting coverage of the Circuit Court, only four of these issues (5 percent) contained information about criminal events and arrests in Chicago itself. On the other hand, thirty (39 percent) of the issues contained a news article about crime elsewhere in the nation.

By 1855, coverage of local arrests was much more prevalent, reflecting both national trends in media consumption and local changes in legal administration. Across the country, readers paid increasing attention to crime stories in the 1840s and 1850s; not only were there a number of new national periodicals specifically dedicated to covering crime stories (such as the National Police Gazette, which began publication in 1845), but such stories often involved explicitly salacious and sensational news (Lehuu Reference Lehuu2003). At the same time, the local papers dedicated increasing space to covering crime following the creation of a daily police court in 1851 (Andreas Reference Andreas1884, 449). Hence, of the seventy-six issues of the Journal I examined from January 1 to March 31 of that year, 57 percent (forty-three issues) contained Chicago crime coverage, while coverage of crime outside the city remained fairly constant (47 percent, or thirty-six issues). In other words, while the population of the city increased sixfold during these years, the number of crime stories involving the city increased over tenfold. Something besides mere population growth was driving a heightened discourse of threat in the city.Footnote 9

Moreover, the spaces associated with all types of crime were explicitly public ones. In all, I was able to catalogue 387 violent events of a variety of types (murders, armed robberies, fights, etc.).Footnote 10 Of those, approximately 213 included information about the locale in which the crime was committed. Table 1 indicates the frequency of location types.

Table 1 Location of Local Violent Events in Chicago Newspapers (1853–1856)

| Location Type | Number of Events |

|---|---|

| Street | 62 |

| Saloon | 38 |

| House | 35 |

| Boarding House | 19 |

| Brothel | 10 |

| Depot | 7 |

| Boat | 4 |

| Bridge | 3 |

| Dock | 3 |

| Hotel | 3 |

| Dance House | 2 |

| Lake Shore | 2 |

| Polling Station | 2 |

| Shanty | 2 |

| Store | 2 |

| Auction House | 1 |

| Barber's Shop | 1 |

| Beach | 1 |

| Bridewell | 1 |

| Coffee House | 1 |

| Construction Site | 1 |

| Gambling House | 1 |

| Grocery | 1 |

| Park | 1 |

| Police Station | 1 |

| Poor House | 1 |

| Post Office | 1 |

| Prairie | 1 |

| Printing Press | 1 |

| River | 1 |

| Steamboat Landing | 1 |

| Theater | 1 |

| Wharf | 1 |

| Wood | 1 |

| Total | 213 |

Data from Chicago Tribune, Chicago Daily Journal, Chicago Daily Democrat, and Chicago Daily Times.

As is evident from Table 1, most of the violence receiving publicity in the press took place in either public places or areas associated with tourist infrastructure—streets, saloons, boarding houses, and so forth. From the outset, the burgeoning police department engaged not in policing general disorder, but instead focused on those areas where such disorder would create an explicitly public threat.

Of particular concern were railroad depots, along with nearby boarding houses and hotels. Swindling, theft, pickpocketing, public drunkenness, and fighting in the very spots where many tourists and prospective businessmen had their very first taste of the city led council members to identify a new threat to public order. “Respectable” residents in the south of the city, for example, confronted problems with rowdy behavior in the “neighborhoods around the several Rail Road Depots,” and issued a petition to request more watchmen to patrol the area (CP 1853, 0976A). Moreover, books (Herbert Reference Herbert1859, 20–28) describing the nefarious stratagems employed by Chicago hack men and “scalpers” were distributed nationally, giving the city unwelcome notoriety.

Strikingly, the areas that became the most associated with crime were also those with the lowest levels of delegative capacity (see Figure 2). These areas—dense zones of ethnic and economic ambiguity and the frequent observation of strangers—were perceived as the most dangerous areas in the city, not only places with a great many public spaces, but also those in which the conditions underlying social order were not in place (Hoyt Reference Hoyt1933, 51, 62).

Figure 2 Violent Events in Select Neighborhoods (1855–1856)

*Divisions between levels are based on natural breaks (Jenks).

As a result, Chicago (like many other big cities at the time) began to be thought of as a destination for outlaws and brigands. Newspapers printed many stories of the travails of travelers, many of whom were taken advantage of or assaulted by brothel keepers, cab drivers, and hotel proprietors in either downtown or on the near north side. Such events dominated coverage of crime in Chicago in the early 1850s (Chicago Daily Journal 1853a, 1853b, 1853c, 1853d, 1853e,). The Chicago elite particularly associated the Sands, which was populated by sailors, squatters, and seedy boarding houses, with criminal activity, frequently complaining that the police seemed ineffective in dealing with the problems posed by such a wild district; “not a week passes,” complained the Chicago Daily Democratic Press (1853), “and scarcely a night without a row, often ending in bloodshed, in that vicinity.” While undoubtedly there was some truth to these fears, the specific situation in Chicago paralleled the larger crisis in confidence that Karen Halttunen (Reference Halttunen1982) has identified as part and parcel of the cultural transition to industrial capitalism in the mid-nineteenth century.

Anonymity and mobility were only the first major threats to delegation; the politicization of ethnicity was another. In St. Louis, New Orleans, Baltimore, and Cincinnati in the 1840s and 1850s, the massive influx of immigrants created a political backlash among existing residents, leading to the creation of powerful local Know Nothing movements and resulting in violent collective disturbances targeting immigrant communities (Grimsted Reference Grimsted1998, 184–93). In Chicago, where the proportion of immigrants was as high as anywhere else in the country, the Chicago Tribune began to argue that it was the Irish Catholics, in particular, who posed a threat to the “good order” of the city, claiming that “a very large proportion … of the riots and bloodshed which have grown out of and in opposition to Native Americanism, may easily be traced to the fatally mistake which is continually being made by the Catholic priesthood of this country in telling their spiritual children that their allegiance and obedience is due, not to the laws and institutions of their adopted country, but to the mandates and instructions of their ghostly superiors” (December 23, 1853).

Crucially, one major problem nativists had with some of the newcomers was related to their capacity to serve as the vessels of delegation. Know Nothingism in Chicago, for instance, was not opposed to all immigration; instead, supporters were worried that Irish and other Catholic “foreigners” would be unable to exercise the kind of self-management necessary to operate in a republican system. “Those Romish adherents,” wrote the nativist paper Watchman of the Prairies, “would prefer that the Pope should enjoy the honors of temporal sovereignty than that the people should enjoy the right of self-government” (Watchman of the Prairies 1850). Those groups that could manage their own affairs were commended; the Tribune, for example, was strongly supportive of both Swedish and Jewish immigrant communities because of their putative self-sufficiency (Cole Reference Cole1948, 62–65). Ethnicity was still useful as a way to delegate authority, but for certain groups with supposed allegiance to a perceived foreign power, such networks could be construed as a means of undermining local social order.

This issue came to a head, however, over the issue of drinking in public saloons. Saloons played an increasingly important role in ethnic life in Chicago and elsewhere during the 1840s and 1850s and were the frequent sites of violence (Duis Reference Duis1983). In its report on the “Liquor Traffic of Chicago” in 1854, the local branch of the “Maine Law” temperance association assailed the saloons as sites of prostitution and gambling, “where time is wasted, morals destroyed, and the ignorant and unwary are robbed of their last dollar” (Chicago Daily Democratic Press 1854).

At the same time, these public places of intermixing were also key institutions for the articulation of a new ethnic politics drawing on links between the growing parties and party leaders (Duis Reference Duis1983); nativist papers repeatedly linked “drinking hells” to the Irish vote (Cole Reference Cole1948, 56–58). As such, for nativists across the country, the problem of violence in saloons was both a danger to the public order—in the sense that saloons were zones of intermixing—as well as a threat to the political rule of the traditional ruling elite—in the sense that they were hotbeds of partisan mobilization.

In Chicago, this crisis led to an alliance between the forces of temperance and Know Nothingism, one that produced a fusion slate for the 1855 municipal elections. This alliance was predicated on defeating the combined politicosocial threat of Catholics, drinking in saloons, and public disorder. Much of this supposed disorder was illusory: the Tribune, for instance, breathlessly fabricated tales of Irish riots at both groggeries and Protestant churches, which it claimed were intended to suppress the Know Nothing vote (Cole Reference Cole1948, 56). Nevertheless, the perception of public danger had changed; precisely as ethnicity became a partisan issue, it ceased to operate as a means through which ruling elites could delegate policing to neighborhoods.

Special Deputization and the Emergence of the Public and Private Police

Despite their severity, city elders did not respond to these threats by radically transforming the existing law enforcement system. Instead, their initial responses built on the republican logic of public interest through private effort, trying to preserve rather than overthrow the key principles of the constable/watch system.

For instance, in 1851, Edward Bonney, a figure known for his pursuit of frontier outlaws in Illinois in the early 1840s, wrote the Common Council laying out the case for the creation of an “independent police” in Chicago (CP 1851, 1290). Arguing that “Chicago is now considered about the safest place of refuge for rogues in the Union” and that “it is in cities and large towns and along the lines of the principle [sic] thoroughfares, that desperadoes concentrate as places most congenial to their habits and criminal careers,” the city required a police force “clothed with the same power to do criminal business that the regular police constables now are.” This police force, argued Bonney, could be organized privately and paid through fee for service by employers. In turn, of course, Bonney generously offered his expert services to the city. The Common Council did not take Bonney up on his offer—primarily because he was not a resident of the city—but it recognized that the problem of public disorder centered on the dimensions he identified: the emergence of anonymous places like hotels and depots where criminals took advantage of the failure of local knowledge and sanction.

Bonney's solution, however, took for granted that private effort could be linked to public interest without contradiction. Indeed, the approach to reforming law enforcement actually taken by the Common Council thus also reflected a commitment to incremental changing of the republican system. Some changes had come to the policing infrastructure of Chicago during the late 1840s and 1850s, for instance, but these were almost always oriented around strengthening the constable and watch system (Mitrani Reference Mitrani2013, 14–23). For example, the council occasionally appointed seasonal forces of night watchmen and even authorized construction of a Watch House in 1845, but such appointments were contingent on momentary outbreaks of disorder (CP 1843, 1523A; CP 1844, 2271A; CP 1845, 2521A; CP 1845, 2544A; CP 1847, 3875A; CP 1848, 4608A). When the night watch was finally put on more permanent footing in October 1849, it was primarily organized to detain those “found … at unusual hours” and “under suspicious circumstances” as well as to arrest drunk and disorderly persons in public places (CP 1849, 5672A).

In particular, however, city elders expanded the use of deputization to special cases, a practice with deep roots in English and US legal history (Radzinowicz Reference Radzinowicz1957, 202–32). Some special deputies were involved in other municipal services—Pound Masters, Bridge Tenders, Tax Collectors, and a Special Sanitary force, for instance, all began to receive special constabulary powers (CP 1852, 0388A; CP 1855, 0611A; CP 1858, 0786A; CP 1865, 0803A). More frequently, however, the mayor appointed specials to deputize already employed watchmen and private guards. While there was some precedent for the mayor and council allowing such appointments in response to individual petitions by business owners, the power was implicit until June 1855, when the council passed an ordinance (CP 1855, 0623A), explicitly enabling the use of specials for businesses. Noting that “many of our railroad and manufacturing companies, lumber, and other dealers find it necessary to employ private Watchman” who would be “much more serviceable to their employees and beneficial to the city of invested with police powers,” the ordinance allowed the mayor to appoint watchmen as specials who “shall profess the same power and authority as the regular police of the city.”

Table 2 depicts some of the businesses that hired and used special deputies. Firms with specific, spatially defined property interests subject to the problems of anonymity and physical mobility—the railroads in particular—hired the bulk of deputies. Although these firms were usually less concerned with public drinking or disorder than political elites, the erosion of the social structural foundations of delegation nevertheless made it increasingly difficult for them to rely on an amateur constabulary (Spitzer and Scull Reference Spitzer and Scull1977, 21–22). Hiring specials was simply a way of using traditional institutions to address a growing threat.

Table 2 Private Special Constable Commissions in Chicago (1840–1871)

| Type of Organization | Number of Specials Hired |

|---|---|

| Railroad | 27 |

| Lumber Yard | 6 |

| Brick Yard | 5 |

| Theater | 5 |

| Emigrant Aid Society | 4 |

| Storage & Commission | 3 |

| Church | 2 |

| Coal | 2 |

| Fire Engine Company | 2 |

| Planing Mill | 2 |

| Alderman | 1 |

| Baker | 1 |

| Boarding House | 1 |

| Brewer | 1 |

| Butcher | 1 |

| Ferryman | 1 |

| Hospital | 1 |

| Land Agent | 1 |

| Machine Works | 1 |

| School | 1 |

| Ship Builder | 1 |

| Wood Dealer | 1 |

Data from Common Council Proceedings Files; oaths only included

The city also used special deputies in response to collective disorder. This was most obvious in the case of the Lager Beer Riot in 1855, the most serious threat to the extant system of policing Chicago had seen. The event was precipitated by the prosecution of a group of primarily German saloon owners for serving liquor without paying the massive licensing fees imposed by the new Know Nothing mayor, Levi Boone. The micro-level story is complex, but the upshot was that a demonstration of the saloon forces on the day of the prosecution induced a police crackdown, which then led to a retaliatory spiral and, by Chicago standards, a severe riot, in which several people were killed and a policeman lost his arm. The majority of the participants in the demonstration were Germans, who had been mobilized through the organized efforts of ethnic elites in the northern section of the city (Renner Reference Renner1976, 14–16).

The Lager Beer Riot was the culminating event of the tensions that had accompanied the rise of ethnic politics in Chicago. For the political elite, the event emblematized the threat jointly posed by saloons as public places associated with disorder and the newfound ethnic (Catholic) resistance to native control over politics. It demonstrated, as nothing else yet had, the ways in which delegated policing was failing to work for communities that nativists had decided were incapable of self-governance. “The attempt made by the Germans to over-awe a court of justice, and to resist the laws of the city, all for ‘lager beer,’” proclaimed the Tribune, “has infused a deep seated and invincible determination in the minds not only of the Americans, but of all the Law and Order citizens of the place, that they shall be made to respect and obey our laws” (Chicago Tribune 1855).

To manage the crisis, Mayor Boone appointed 201 special officers (including luminaries like Allan Pinkerton), who were deputized to help keep the peace during the riots, and mobilized several local militia units to aid the special deputies and the city watch in restoring order (see CP 1855, 2434A). In his debriefing to the Common Council, the mayor remarked with pride that he was quickly able to produce “a force so strong that none would be rash enough to oppose it,” composed of both regulars and specials, all “men of indomitable courage and firmness, proving themselves eminently worthy of the trust that had been reposed in them” (Chicago Weekly Times 1855).

However, the riot also clarified a need for further change in how law and order was managed in the city; indeed, as scholars have pointed out (Gilje Reference Gilje1996, 138–39; Rousey Reference Rousey1996, 62–80), ethnic rioting led to calls for policing reform in cities throughout the country. In Chicago, the Common Council, under the slim control of the Know Nothing Party (and with the support of the Chicago Tribune), began deliberations on restructuring the existing police force and creating a new consolidated police department. The republican system, which had guided Chicago's first twenty years, was well on its way to decomposing into something new, even as elites continued to rely on traditional techniques.

The Creation of the Police

The reorganization of the police force in April 1855—in part a response to the Lager Beer Riots—has been interpreted as a major organizational innovation for the municipal governance of Chicago. The ordinance itself creating the new department was passed by a close 8–7 vote on April 30, 1855, and involved the expansion of the existing force, its reorganization into police districts, and the creation of a more clear-cut internal chain of command (CP 1855, 0293A).

In an important recent account, Sam Mitrani (Reference Mitrani2013, 28) claims that through the reorganization, “the police were transformed from an unorganized, undisciplined, and poorly defined group of citizens into a well-ordered hierarchy organized along military lines and clearly differentiated from the rest of the population by their uniforms.” This, he argues, marked “a crucial founding moment” in the modernization of the city's coercive capacity.

Even though these changes were significant, the new police force largely reflected the republican foundations of delegative law enforcement rather than a clear attempt to transform the existing system. The riot did catalyze a demand for change among municipal leaders, but the actual response involved reconfiguring existing forms of supplying social order that, for reasons largely unappreciated by political elites, would lead to large-scale change down the road. This was true for several reasons.

First and most significantly, the new force established in 1855 represented only an incremental bureaucratic shift rather than a quantum change in police organization. Not only was there already an administratively separate police department in place in 1853, but Boone had already spelled out the need to combine the day and night police in his inaugural address, well before the violent events of late April (Chicago Daily Democratic Press 1855). Moreover, in anticipation of the need to enforce a new Sunday closing law, he had already dramatically expanded the force through special deputization almost immediately after taking over the mayoralty (Einhorn Reference Einhorn1991, 164). The official transformation in 1855 was more a matter of quantity than quality; the force was expanded and made more directly subject to mayoral control, but the essential regulatory structure and rulebook of the force was kept in place. Although the size of the force was expanded to ninety-six in the spring of 1855, there were at least fifty-two members of the watch who had served the city by the end of 1854; given the fact that the population as a whole increased just 20 percent during that year, this expansion was significant, but not necessarily transformative.

Second, the reorganization of the police did not supplant older republican institutions, but rather coexisted with them. For instance, the constable remained a key law officer in the wards, special deputies continued to be appointed as supplements to the public police force, and the fee structure continued in place for nonpolice law officers until well into the 1860s (Journal of the Proceedings of the Common Council 1871). Moreover, other traditionally republican institutions (such as the Cook County Sheriff) remained highly active participants in law enforcement, and important political figures such as Anton Hesing (a leader of the German community) viewed the role as a crucial stepping stone in their public careers (Chicago Tribune 1860). Indeed, the ordinance expanding the powers of deputization to include businesses was actually passed the month after the reforms of 1855 (CP 1855, 0623A), indicating that special constables were seen as just as valuable in addressing the problem of law enforcement as paid police.

There were other points of continuity with earlier forms of policing. For instance, the personnel of the new police force included many who had held earlier law enforcement roles. The special deputies who served during the riot, for instance, provided the core for the new police force; twenty-nine of these deputies were hired by the police department in the following years. Moreover, of the ninety-six officers who took oaths to serve in Boone's police in the spring of 1855, forty-six (or 47 percent) had served in some policing capacity during the height of the republican system of constables and watch (for the oaths, see CP 1855, 2436A).

Indeed, the Chicago Tribune (1855) complimented the new captain of the force, Cyrus Bradley, as a reputable member of the old order: Bradley had “long been known to us as one of the most efficient conservators of the peace and good order of the city,” and, as one whose “name has already become a terror to evildoer,” he would best be able to preserve the good order of the city.Footnote 11

From the outset, police rosters also reflected the importance of ethnicity as a political category. Of the forty members of the original police force for whom I was able to locate information on ethnicity, thirty-six (or 90 percent) were native Americans, many of whom were involved in Know Nothing politics (Mitrani Reference Mitrani2013, 30–31). This was a major source of contention for the Times (June 14, 1855), which complained about a “Know Nothing and do-nothing police” that focused on persecuting poor Irish women rather than solving “important” crimes. When control over city government reverted to the Democrats in 1856, Thomas Dyer, the new mayor, completely overhauled the force—of the ninety-eight members listed on the new roster, only nine were also on the previous year's list (CP 1856, 1446A). In addition, approximately three-quarters of those on the new force were Irish or Germans, leading the Tribune to retaliate in a series of editorials about the incompetence of police officers in the city, even accusing some of running “rumshops” (Chicago Tribune 1856; Cole Reference Cole1948, 94–95).

In other words, the new police force reflected the traditional importance of ethnicity as an organizing principle for delegating law enforcement, even as disorder itself was increasingly understood in cultural and religious terms. And because the elements of disorder—the growth of anonymity and mobility, the heightened perception of property and personal crime, the anxiety over the politics of ethnic mobilization, and the use of special deputization—were found throughout large US municipalities during the 1850s, Chicago's police department was just one of a number emerging from the existing republican institutional order that explicitly built on the foundation of local delegation (Schneider Reference Schneider1980, 77–86).

As in other US cities at the time, though, the permanence of the Chicago police was not a foregone conclusion. Indeed, even as late as the 1860s it remained unclear both how the use of special deputization and the consolidation of the new department would play out over the long run and whether the municipal police would be the only security option available to political and economic elites. Just as municipal reforms were creating the seed for a new kind of public policing infrastructure, so, too, was a private alternative emerging, one that built on precisely the same incremental approach to change and reliance on traditional republican institutions.

The Creation of the Private Security Industry

The new American private security industry—in which Chicago was an important center of activity—represented the other half of the decomposition of the republican system in the 1850s. Just as with the new police, it was the availability of special deputation for private security purposes that fed into the creation of a new industry (e.g., ten of those who served during the Lager Beer Riots later became private detectives or watchmen). The shared ancestry of the public police and the private security industry in an older republican tradition helped ensure that, over time, the two entities would coevolve rather than emerge as competitors and rivals.

Unlike the police, however, which reflected the public side of the old republican institutional logic, this new industry emphasized private interests and incentives. Guard and detective firms were organized by entrepreneurs to confront the increasing problem of theft, as well as the class of threats (such as swindling and fraud) associated with social anonymity that Friedman (Reference Friedman1991) has called “crimes of mobility.” Though public police were also responsible for addressing property crimes, the need for agencies that could move across jurisdictional boundaries became key in a world with fast and integrated transportation networks (Unterman Reference Unterman2015, 35–42). The unease created by the Lager Beer Riot likely accentuated this general sense of disorder in Chicago.

There were two sides to the emergence of this new industry: the first were the entrepreneurial firms organized to provide security and detective services to private firms; the second were watchmen and “merchant police” forces organized en masse by companies themselves to protect property. Allan Pinkerton exemplifies the first development. Pinkerton's early experience as a deputy sheriff made the transition to viewing the organization of violence as entrepreneurial activity seamless. As a deputy, Pinkerton received fees based on performance, the same system that remunerated city and county constables. Deputies like Pinkerton had traditionally done the brunt of actual policing work for sheriffs, whose activities mainly involved serving process, and as a deputy in a county with some of the most well-developed railroad infrastructure in the world in 1853, Pinkerton's duties also frequently took him across the region, which allowed him to cultivate a wide range of contacts (Morn Reference Morn1982, 35–39). Because outside the politically fraught and minuscule US Marshals Service there was no national police force in the United States at the time, Pinkerton's conversion of his thief-taking duties to a national scale meant creating a new, private firm to take advantage of the rewards such arrests could provide. His decision to organize a North-Western Detective Police Agency, the first such agency in Chicago, with lawyer Edward Rucker in March 1855 (just days before the election that brought Levi Boone to power in the city) was a simple one, adapting the skills and connections he had established as a deputy to service clients (Chicago Tribune 1855). Some of the firm's earliest clients, unsurprisingly, were railroads (Chicago Tribune 1856).

The private detective industry built on the traditional republican constable system in two ways. First, it relied on contracts and fee schedules (Spitzer and Scull Reference Spitzer and Scull1977, 19–21). This meant that the kinds of services provided by private security were limited in scope and focused only on particular problems confronted by clients. Second, it relied on ad hoc deputization (US Senate 1893, 235). Private detectives frequently worked closely with local courts and were allowed to participate directly in arrest (Pinkerton and Pinkerton Reference Pinkerton and Pinkerton1895, 6–14). Detectives also relied on the common law, by which average citizens could arrest offenders for felonies committed in their presence on their own authority (Warrum Reference Warrum1895, 85–86).

Pinkerton's firm was the first but not the only private security firm to emerge out of the ferment of antebellum Chicago. Cyrus Bradley—Pinkerton's former boss and the city marshal under Levi Boone—formed a private Detecting and Collecting Police Agency with a number of other police officers after the Know Nothing Party was defeated in 1856 and Dyer restructured the police department (Chicago Tribune 1856). Though rivals, both Bradley and Pinkerton provided detective services calibrated to address the same problems in finding criminals in anonymous settings (Johnson Reference Johnson1979, 65).

By 1860, entrepreneurs began to offer a second kind of service in Chicago aimed at saturating vulnerable areas—especially business and warehouse districts—with watchmen. These watchmen, sometimes known as merchant police, formed a privately funded, geographically limited alternative to the kind of patrol municipal police services were increasingly expected to provide for the general public across the city.Footnote 12 Private police services were offered by George T. Moore's Merchant Police (Chicago Tribune 1858) as well as by Pinkerton's Preventive Police patrol, also founded in 1858, a force that was active in patrolling retail and public areas through the 1860s. In 1858 alone, for example, the Pinkerton Preventive Patrol arrested fifty-three people for a variety of infractions and worked closely with the Chicago police. These groups formed a corps of paid watchmen available for selective patrol, capable of using force if necessary to protect their client's property (Morn Reference Morn1982, 29–30).

The new guard industry was also promoted by non-security firms who hired their own watchmen, without going through a merchant police service (Schneider Reference Schneider1980, 62–63). Railroads and some of the larger manufacturers had employed their own watchmen beginning in the early 1850s, but by the end of the decade the pattern of hiring permanent guards was set, particularly in the transportation and industrial sector. For instance, as evident in Table 3, which presents the numbers of individual guards identified in city directories who were hired to work for different firms, every sector of the economy increased the number of guards it hired after the war. In particular, the new, large sectors—railroads and heavy manufacturing, factories and stockyards—that had much physical property to protect relied most directly on their own private armies of watchmen.

Table 3 Number of Private Watchmen Employed in Chicago Firms (1851–1870)

| Firm Type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Industry | Transportation | Retail | Recreation | Office | Wholesale | Total |

| 1851-1855 | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 |

| 1856-1860 | 3 (6%) | 36 (80%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 45 |

| 1861-1865 | 28 (20%) | 84 (60%) | 1 (0%) | 11 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 16 (11%) | 140 |

| 1866-1870 | 100 (28%) | 183 (51%) | 8 (2%) | 20 (6%) | 9 (2%) | 42 (12%) | 362 |

| Total | 134 (24%) | 306 (55%) | 10 (2%) | 32 (6%) | 10 (2%) | 61 (11%) | 553 |

Data from City Directory of Chicago, 1851–1870.

Note: Row percentages in parentheses; totals do not add up to 100% because of rounding.

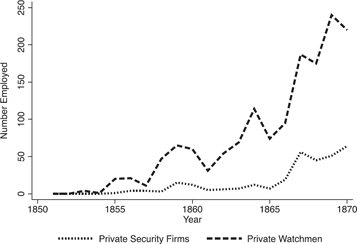

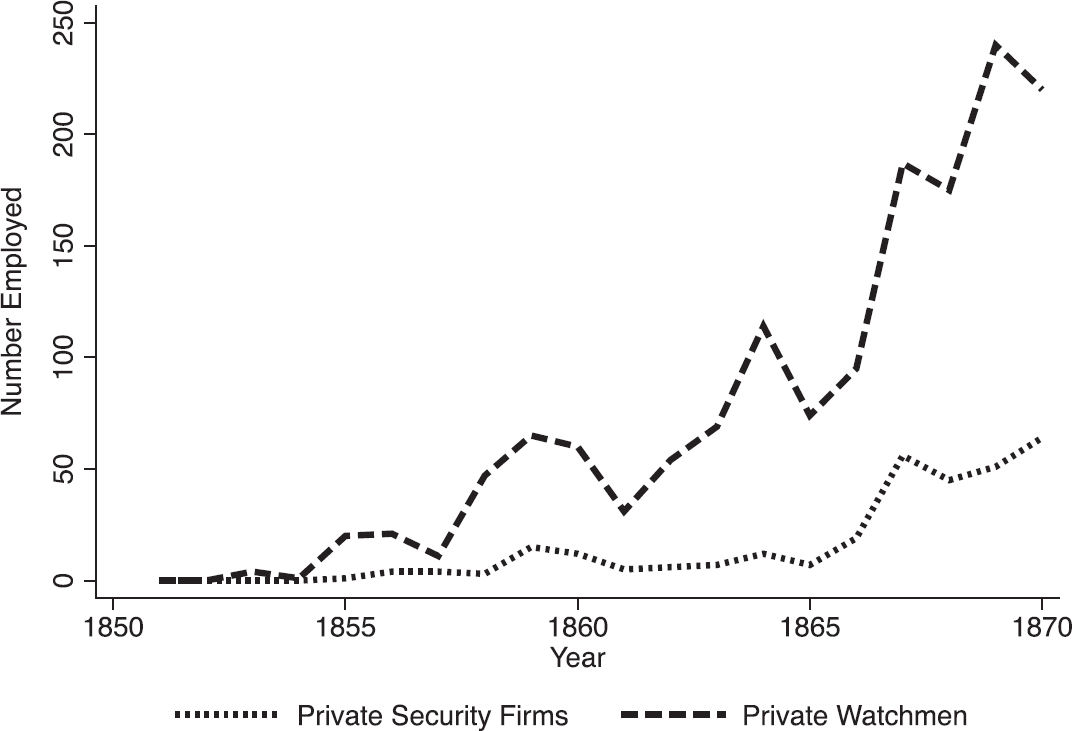

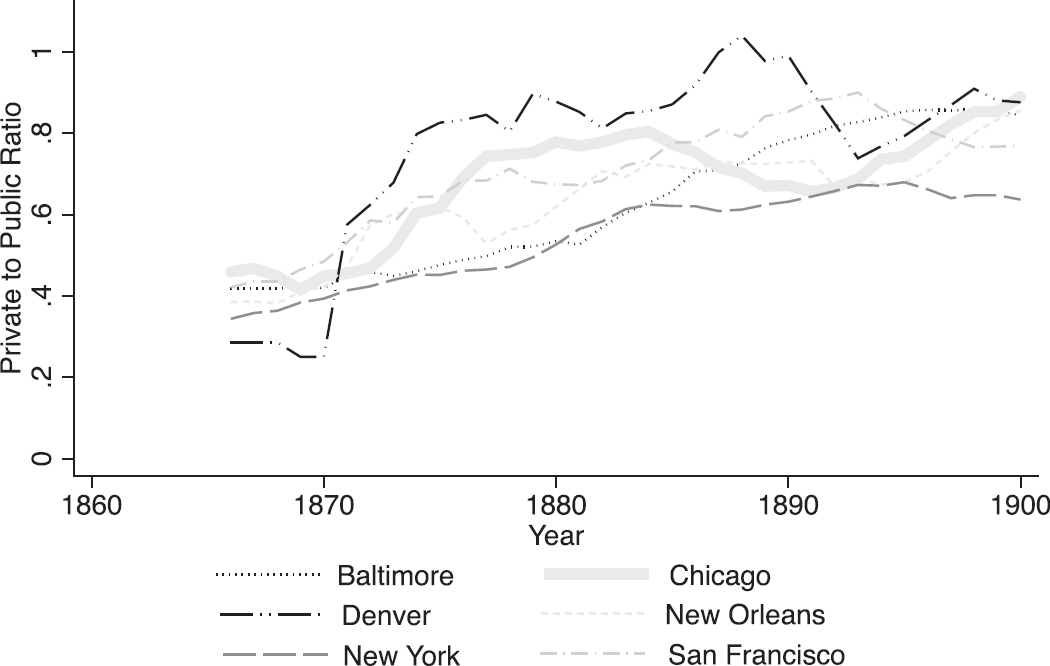

Figure 3 depicts the annual number of individuals I could identify in the city directories who were employed as private guards or by private security firms from 1851 through 1870. The trend lines are fairly straightforward: firms had begun hiring private guards prior to the Civil War, but the years between 1860 and 1870 saw a dramatic escalation in their number. By the mid-1870s—when the Pinkerton firm began redefining its operations by chasing bandits in the West and suppressing union organization in the East—the private security complex was well entrenched across the nation (Weiss Reference Weiss1981).

Figure 3 Trends in Private Security Employment in Chicago (1851–1870)

Data from City Directories of Chicago, 1851–1870.

Evolution and Institutional “Lock in”

The use of traditional republican institutional practices like special deputization to address new threats to social order and the gradual extensions of those mechanisms to serve the ends of political and economic elites ultimately led to the creation of both the public and private security industry. However, and crucially, the new divide between what counted as public and what was private only stabilized over time, and was a product of reorganization of the networks linking these state and market forms of law enforcement.

Ironically, during the early years of both the private security industry and the public police department, it was not even clear whether either or both would survive. In the late 1850s, for example, Chicago papers began a debate over whether the municipal police were actually an effective means of managing the gap created in delegated policing. Democratic papers and politicians decried the adoption of policing duties by specialist private firms and private watchmen rather than neighborhood police, arguing that “it is the business … of a private police everywhere to affrighten the people and make them think they are unsafe unless a private police is maintained” (Chicago Daily Democrat 1857). Although it also often emphasized the need for a publicly funded police, the Tribune considered private detectives like Pinkerton and Cyrus Bradley as heroes.Footnote 13

Though this debate carried on for several years, public and private security alternatives flourished, often cooperating with one another and sharing resources. For example, Pinkerton guards frequently cooperated with Chicago police by identifying public threats (see Chicago Tribune 1864) and, often, aiding in the investigation of robberies and property crimes (see Chicago Tribune 1863, 1869). Moreover, Pinkerton's agency was itself even hired by the city to investigate certain crimes, such as a notorious grave-robbery scandal involving city officials in 1857 (Chicago Tribune 1857). The boundary between public and private security was quite ambiguous, particularly in the early years of the new police department, and private detectives frequently saw themselves as public-minded officials. Moreover, many police officials—such as city constables—continued to operate on the basis of fees and personal rewards.

Part of what allowed this dual system to work was the fact that public police and private security agencies were tied to one another through their experiences in older republican institutions. Indeed, private policing quickly became an attractive option for those who lost their jobs with the public police—the volatility of early municipal governance institutions undoubtedly played a crucial role incentivizing actors to seek out novel forms of employment. Special deputization was a seedbed for both types of careers, and it linked public actors to private security professionals.

There are several ways of demonstrating this dynamic. I begin by exploring how occupants of different protection agencies in Chicago moved back and forth between occupational positions. I collected data on almost 3,800 individuals active as watchmen, policemen, sheriffs, constables, and private detectives in Chicago from 1845 through 1871 (for the purposes of this article, I only focus on interorganizational mobility from 1845 through 1860). I culled these data from a variety of sources, including official rosters and records of oaths, newspaper articles, and city directories. By examining who these individuals were and what kinds of jobs they held, as well as what activities they participated in, I demonstrate the interconnections among personnel in the institutional framework of Chicago security over time.

Most members only belonged to one organization throughout their careers. However, some were much more active—450 of the 3,799 people identified in this study (around 12 percent) belonged to different security organizations at some point. Table 4 sets out the number of individuals who moved from job to job. If the theory is correct, we should see the creation of specific career pathways that show how actors transformed the older system of delegated policing into these types over time. By treating the flow of security providers from one organization to another as a social network, in other words, I can identify both how those providers related to each other and whether particular roles were important in linking them together.

Table 4 Links Between Security Organizations in Chicago (1845–1871)

| Destination | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police | Private | Special Police | Municipal | Sheriff | US | US | County | Private | Municipal | County | |

| Origin | Detective | Force | (Other) | Marshal | (Other) | (Other) | Firm | Constable | Constable | ||

| Police | 39 | 28 | 23 | 16 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 94 | 57 | 14 | |

| Private Detective | 51 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 3 | |

| Special Police Force | 44 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 1 | |

| Municipal (Other) | 31 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 3 | |

| Sheriff | 13 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 9 | |

| US Marshals | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| US (Other) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| County (Other) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Private Firm | 82 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 4 | |

| Municipal Constable | 53 | 4 | 12 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 25 | |

| County Constable | 15 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 29 | |

*Data from Common Council Proceeding Files and City Directories of Chicago (1845–1871).

Includes those moving from position to another within five-year windows.

One way of unpacking this process involves examining which organizations were crucial in knitting different types of actors together. Drawing on the influential notion of brokerage elucidated by Gould and Fernandez (Reference Gould and Fernandez1989), I identify those organizational nodes that act as liaisons in the interorganizational network; that is, those that are uniquely positioned to connect nodes with different kinds of attributes. This analysis reveals that those receiving special deputization did indeed broker relationships among different types of organizations; the position of being a special deputy played the liaison role first between the city watch and the older municipal constabulary from 1845 to 1850 and then for the police force and the private detective industry in the crucial years of the late 1850s.Footnote 14 Being a special deputy, in other words, was an important step in the transition from being a public to a private security officer and vice versa, helping lock in the new organizations as compatriots in a new network of security providers in the antebellum city.

Moreover, when we look at the level of individual careers, serving as a member of the special police played a key role for the most important of security officers. Of the total number of security providers identified in the dataset, I focus on 388 who were the key players in the network—those for whom we have comparable records over time and who were members of multiple organizations.Footnote 15

Some summary information about the career trajectories of these individuals is presented in Table 5, which records the frequency with which an organization assumed a particular position within the career trajectories of the actors in the set (the numbers in the columns reflect the number of individuals in the sample to whom the role position applies). The most active seedbed for security careers was the police force: of the 388 individuals, approximately 39 percent began their trajectories as police. On the other hand, the special police force served as the most active intermediary position for security experts in Chicago; approximately 27 percent of those who were special police officers held the role between holding two other positions.Footnote 16 This again hints at the importance of traditional republican deputization as facilitating broker between “modern” security jobs.

Table 5 Career Trajectories of Important Actors (1845–1871)

| Starting | Intermediary | Last | Any | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Position | Position | Position | Position | |

| Police | 150 | 30 | 119 | 299 | 1.57 |

| Municipal Constabulary | 52 | 22 | 37 | 111 | 1.74 |

| Private Detective Firm | 38 | 17 | 43 | 98 | 1.84 |

| Sheriff | 14 | 12 | 19 | 45 | 1.89 |

| Special Police Force | 19 | 15 | 22 | 56 | 1.95 |

| Private Firm | 71 | 16 | 80 | 167 | 1.74 |

| County Constabulary | 26 | 11 | 31 | 68 | 2 |

| Municipal (Other) | 13 | 7 | 23 | 43 | 2.21 |

| US (Other) | 2 | 4 | 12 | 18 | 2.33 |

| US Marshals | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1.75 |

| County (Other) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

N=388; Avg. Trajectory Length: 2.35 (s.d.: 0.67); Max: 6

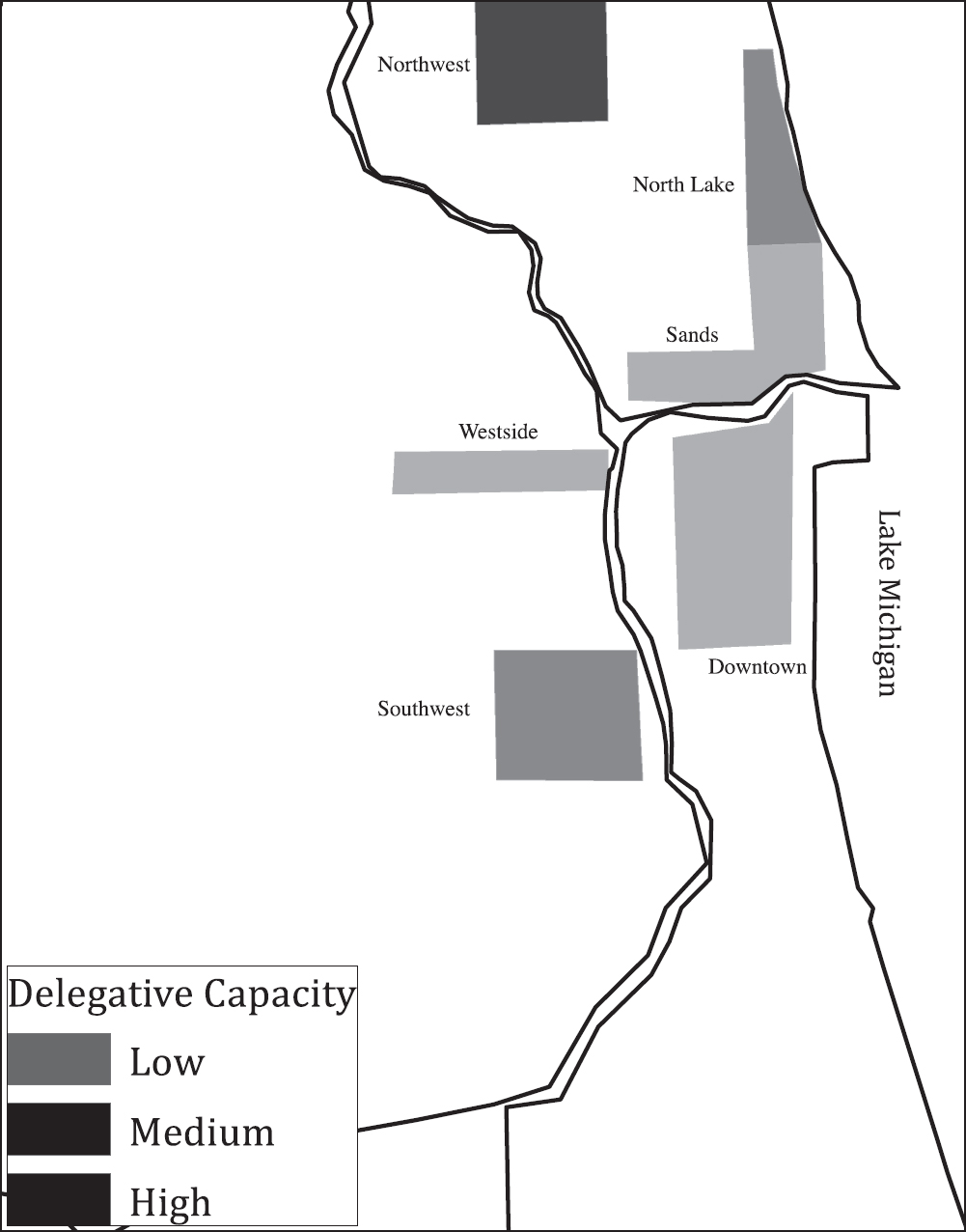

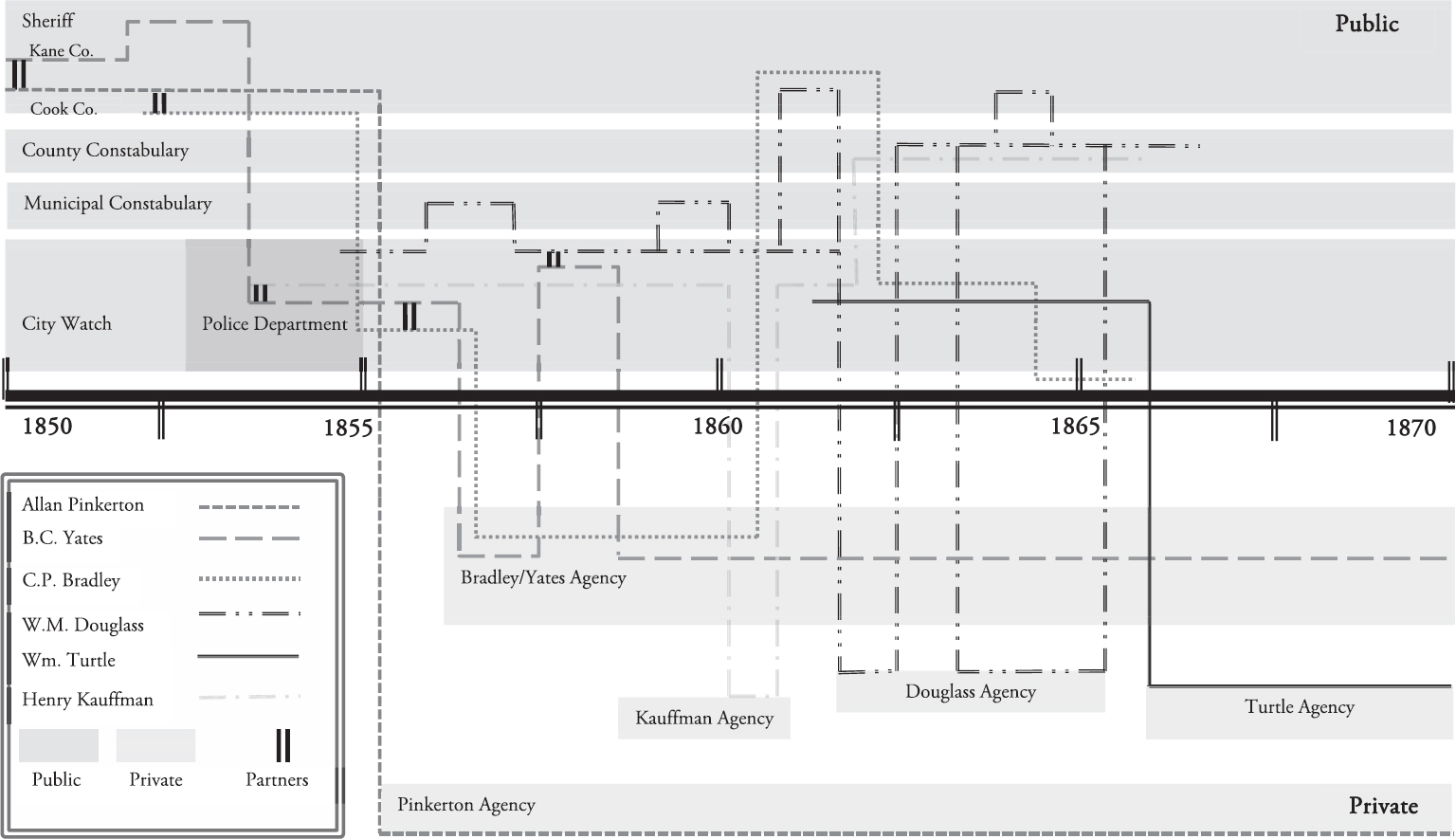

Not only did traditional republican roles like that of the special deputy connect the private industry to the public police in general, but a group of very influential individuals occupied both public and private security institutions at various points in their careers. To explore this, I trace the careers of six of the most well-known individuals active in Chicago's police and private detective system in the timeline presented in Figure 4. In this figure, each line represents the career of an individual through time, while the shaded regions represent different types of security institution in which the actor in question participated. The timeline bar in the middle represents a divide between public and private institutions, while the small vertical bars in the chart itself indicate that the two actors were linked together as partners in a criminal case at a given point.

Figure 4 Selected Career Trajectories of Chicago Violence Experts (1850–1870)

The figure demonstrates several things. First, early ties between these actors, often forged during shared public service, paved the way to future careers as private detectives. Bradley and Yates, having known Pinkerton as a deputy and witnessed his success, decided to become private detectives after having lost their jobs in the turnover of the 1856 election. In a sense, the private security option allowed for a kind of shadow police force, which could be called on in the aftermath of an electoral transition.

Second, these actors also moved throughout their careers between public police and private service. Yates, Bradley, Kauffman, and Douglass all served as police as well as in other county or municipal roles. Douglass, in fact, linked multiple roles together at one time, apparently serving, for instance, as both a police detective and a municipal constable in 1859 and later combining service as county constable with his private position as head of his own agency. This, in turn, helped lock in a longer-term pattern in US policing whereby law enforcement became the purview of a wide variety of actors and in which public and private police frequently cooperated and shared information and resources (Morn Reference Morn1982, 164–83).

Conclusion