INTRODUCTION

Hong Kong's political agenda has featured intense debates and conflict in recent years over how its top officials are elected (Langer Reference Langer2007; Zhang Reference Zhang2010; Ip Reference Ip2014; Young Reference Young2014). This article reviews how the rules for electing Hong Kong's legislators have affected party system development and limited the effectiveness of the Legislative Council (LegCo). Building on existing scholarship on how votes are translated into LegCo representation, I examine how electoral rules shape the strategies pursued by Hong Kong party leaders. I also place Hong Kong elections in a broader comparative perspective, illustrating how LegCo electoral outcomes would differ under the proportional representation formula most commonly used in democracies around the world. And I show that even behavior that appears counterproductive, such as failing to form broad alliances, is a strategic response to Hong Kong's electoral rules rather than a symptom of political dysfunction.

Many observers have noted that Hong Kong elections are characterized by severe fragmentation of lists. Most notably Ma Ngok and Choy Chi-keung, in a variety of investigations, have emphasized that the formula for list proportional representation (PR) used in Hong Kong, known as Hare Quota with Largest Remainders (HQLR), encourages fragmentation. Rather than rewarding an electoral alliance for uniting as many votes as possible under one banner, HQLR punishes big winners and encourages political allies to divide. The effect of HQLR is to hinder the development of strong parties with encompassing platforms, limiting the LegCo's potential as a representative institution.

Most democracies that use list PR to elect their legislatures do not use HQLR, and the most commonly used PR formula rewards list size rather than punishing it. This article demonstrates the extent to which an alternative PR formula would produce incentives to unite party lists, and contrasts these with the incentives to fragment present in Hong Kong. It also illustrates the opportunity costs Hong Kong politicians would confront, given the rules under which they compete, if they did not fragment their lists and instead pursued unified alliances.

The article proceeds as follows. First, I review the key institutional design decisions that produced the current electoral system, what prior scholarship has to say about the system, and what this article adds. Next, I compare the mechanics of the HQLR formula with the most commonly used PR formula worldwide, the D'Hondt divisors method, and I illustrate the pattern of party and list fragmentation in LegCo elections under HQLR. The next section introduces the idea of electoral efficiency and demonstrates that Hong Kong party leaders have responded to the incentives HQLR generates, but that the incentives under D'Hondt would be starkly different. The last section reflects on the broader implications of HQLR for Hong Kong politics, locates the case of Hong Kong in comparative perspective, and considers the effects of electoral system design on democracy in the special administrative region.

ENGINEERING FRAGMENTATION AND DIAGNOSING THE EFFECT OF HQLR

Across all elections for national legislatures in democracies since 1946, 31 percent have been held under single-member district (SMD) rules, 56 percent have been held under PR, whereas 13 percent combined SMDs with some other (usually proportional) method. Of the PR elections, 24 percent have used the D'Hondt divisors formula, 16 percent have used HQLR, and another 16 percent have employed some one of over a dozen other formulas in use.Footnote 1 In short, electoral system designers had a wide variety of options for the LegCo, even within the family of PR systems. Within that family, the most commonly used formula by far is D'Hondt.

The selection of HQLR for Hong Kong was part of a package of electoral reforms adopted by the government of the People's Republic of China in the late 1990s, when sovereignty over the region was transferred. In the late stages of British rule in Hong Kong, the colonial government conducted two elections in which some members of the LegCo were directly elected.Footnote 2 In 1991, those seats were elected by block vote in two-member districts; in 1995, they were elected by SMD plurality. Either method allows a camp that can command plurality support to capture a large winner's bonus, and Hong Kong's pro-democratic forces dominated both elections, winning 16 of the 18 directly elected seats in 1991 and 17 of 20 in 1995. These outcomes alarmed the officials in Beijing who were preparing for the reabsorption of Hong Kong and crafting the institutions that would define governance under “one country, two systems” (Lam Reference Lam1995; Wong Reference Wong1998; Ho Reference Ho1999; Baum Reference Baum2000; Pepper Reference Pepper2000).

Lau Siu-kai (Reference Lau, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai, Kin-sheun and Wong1999) provides a detailed account of the deliberations of that era. From 1994 to 1996, Lau served as a convener first of the Electoral Affairs Study Subgroup for Hong Kong, then of the Subgroup on Electoral Methods for the First Legislature (SEMFL), both appointed by the National People's Congress in Beijing. He acknowledges that preventing the development of effective legislative parties was a central priority for Beijing:

The Communist regime … realized full well that the appearance of political parties was inevitable whenever there were elections, particularly popular elections. It nevertheless did not want to see the rise of anti-Communist political parties in Hong Kong. Nor could China tolerate the domination of the legislature by a powerful political party, which then could use the veto powers at the legislature's disposal to “blackmail” the executive or to bring about stalemate between the executive and legislative branches … In devising the electoral arrangements for the first legislature of the HKSAR, therefore, China strove to impede the development of local political parties, particularly those with pro-democratic and anti-Communist inclinations. (Lau Reference Lau, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai, Kin-sheun and Wong1999, 13–14)

Restricting the share of directly elected representatives and stacking the functional constituencies with representatives selected independently from parties promoted this agenda, but in Beijing's estimation, so did abandoning the majoritarian formulas that had been used under British sovereignty for the directly elected LegCo seats:

In view of the anti-Communist sentiments in Hong Kong and the instinctual tendency of a majority of the people to vote for politicians who stood for the interests of the man in the street, it was unavoidable that more than half of the seats would be won by the pro-democracy and pro-grass-roots politicians. Still, if a decent minority of directly elected politicians took a friendly stance toward China and a moderate position on socio-economic issues, the political clout of the majority could be blunted to a certain extent. (Lau Reference Lau, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai, Kin-sheun and Wong1999, 15)

The Beijing government considered adopting either list PR or the single non-transferable vote (SNTV) system. The latter presents the greatest obstacles to political party development of any system used to elect national legislatures (Cox & Shugart Reference Cox and Shugart1996; Cox, Rosenbluth, and Thies Reference Cox, Rosenbluth and Thies1999; Reynolds & Carey Reference Reynolds and Carey2012). But Beijing eventually soured on SNTV because, by the late 1990s, it was used only in Taiwan (Lau Reference Lau, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai, Kin-sheun and Wong1999). Ultimately, the National People's Congress opted for list PR, with the goal of allowing pro-Beijing politicians to transfer their roughly 40 percent support in the electorate into a corresponding number of seats in the LegCo. In combination with the functional constituency seats, which over-represent business and financial interests inclined to avoid direct confrontation with Beijing, the system has realized its designers’ goals of preventing the development of a pro-democracy party that could control the LegCo and use it as a platform to challenge the chief executive's dominance in setting policy (Ma and Choy Reference Ma and Choy1999).

Scholars of Hong Kong elections have widely noted that the adoption of PR provided insurance for Beijing against a pro-democracy tsumami in the LegCo (Fung Reference Fung1996; Ho Reference Ho1999; Baum Reference Baum2000; Choy Reference Choy2013). These accounts correctly note that PR provides fewer incentives for the formation of broad electoral alliances than do the majoritarian electoral rules that governed contests for the LegCo's directly elected seats in 1991 and 1995 (Duverger Reference Duverger1951; Cox Reference Cox1997). Nevertheless, there are two relevant comparisons at work here. The first is between majoritarian electoral rules and PR, and the second is among PR formulas. Scholarship on Hong Kong elections has widely recognized the former, emphasizing that PR elections have fostered more party fragmentation than would majoritarian ones (Cheng Reference Cheng2001 and Reference Cheng2010; Cheung Reference Cheung2005; Lee Reference Lee2010; Yip and Yeung Reference Yip and Yeung2014), but less frequently recognized the role played by the choice of HQLR rather than other available PR formulas.

The most prominent exceptions are a series of studies by Ma Ngok and Choy Chi-keung, both individually and in collaboration. These scholars emphasized early on that Beijing's support of PR elections was a strategic move that could fragment the pro-democracy camp's forces in the LegCo (Ma and Choy Reference Ma and Choy1999; Ma Reference Ma2001 and Reference Ma, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai and Ka-ying Wong2002). The experience of the first two elections after the transfer of sovereignty, in 1998 and 2000, featured rivalries within parties, and the first instances of strategic list splitting (Choy Reference Choy, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai and Ka-ying Wong2002). Ma and Choy presciently attributed this phenomenon to the disadvantage that large lists face under HQLR in winning “the last seat” in any given district (2003a, n. 7), and for the 1998 election they identified two districts in which seat distributions across parties would have differed had the D'Hondt formula been used rather than HQLR (2003b). As strategic list-splitting has increased in Hong Kong and spread from the pro-democratic to the pro-Beijing camp, these scholars have chronicled the fragmentation, diagnosed HQLR as a motivating factor, and identified the phenomenon as a contributing factor to the LegCo's weakness as a counterweight to the chief executive (Ma Reference Ma2005, Reference Ma, Wai-man, Luen-tim Lui and Wong2012, Reference Ma and Cheng2014; Choy Reference Choy2013; see also Chen Reference Chen2015).

Building on the foundation established by Ma and Choy, the remainder of this article offers a number of further contributions. I illustrate the virtual disappearance from Hong Kong elections of competition for seats by full quota. Then, using district-level returns from every election from 1998 to 2016, I produce simulated outcomes showing that the impetus toward fragmentation would not have applied—indeed, it would have been reversed—if Hong Kong employed the more widely used D'Hondt divisor PR formula rather than HQLR. I also produce simulations that illustrate how recent electoral results would have differed under HQLR, had the pro-democratic camp not pursued list fragmentation. In all, these analyses indicate that the current rules make list fragmentation an effective strategy for party leaders, whereas other rules would alter strategies, and could produce a LegCo with broader party alliances.

PR FORMULAS

Despite their common purpose, the two most common PR formulas differ both in their mechanics and in their effects on electoral outcomes.

HQLR

The basic principle of HQLR is to set a “retail price,” in the currency of votes, at which seats in each electoral district may be “purchased” by lists. That price, or quota , is determined by dividing the total number of valid votes cast in a district by the DM.Footnote 3 After votes have been tallied, each list is awarded as many seats in the district as full quotas of votes it won. For each seat awarded in this manner, a quota of votes is subtracted from the list's district total. If not all seats in the district can be awarded on the basis of full quotas, any remaining seats are allocated, one per list, in descending order of the lists’ remaining votes. These seats, therefore, are purchased for less than the retail price (or quota) for a seat. Lists that win seats on the basis of their remainders are, effectively, buying seats “wholesale,” at reduced prices. Note that, under HQLR, it is virtually impossible for all seats in a district to be purchased at retail price, so the HQLR method almost guarantees that, within a given district, lists will pay different prices for seats they win.

D'Hondt

Under D'Hondt, all seats are awarded according to a uniform principle. Rather than set a price in votes for the purchase of seats, divisors methods use the tallies of votes across lists to establish a matrix of quotients pertaining to lists, then allocate seats in descending order of quotients until all the seats in a given district are awarded. A hypothetical example illustrates. Imagine a district in which 1,000 votes are cast with four lists—A, B, C, and D—competing. The votes are distributed across lists as illustrated in Table 1: 405, 325, 185 and 85, respectively. D'Hondt proceeds by calculating a matrix of quotients by dividing each list's tally by the sequence of integers 1, 2, 3, and so on. These quotients are shown in the successive rows of Table 1.

Table 1 Illustration of the DHD method in a hypothetical district

Once the matrix is constructed, seats are awarded in the descending order of quotients. In this district, for example, if DM = 6, then the distribution of seats under D'Hondt would be A(3), B(2), C(1), D(0). By contrast, under HQLR the seat distribution would be A(2) B(2), C(1), D(1), thus benefitting the smallest list and disadvantaging the largest relative to D'Hondt.Footnote 4

LEGCO FRAGMENTATION

Since the transfer of sovereignty from the United Kingdom back to Beijing in 1997, and the formation of a new LegCo under Hong Kong's Basic Law, the assembly has grown in size. Still, only half of its members are directly elected in districts by HQLR, whereas the other half are chosen by “functional constituencies,” a corporatist system in which key decision-makers are selected by commercial, professional, and civic groups whose voting weight does not correspond to their share of the population (Pepper Reference Pepper2000; Ip Reference Ip2014).Footnote 5 The sizes of these cohorts are shown in Table 2.Footnote 6

Table 2 How LegCo members are selected

There are five geographical districts for the list PR elections. Table 3 shows the number of seats awarded in each geographical constituency in the HKSAR in each election since 1998.

Table 3 Seats per geographical constituency

Within each district, parties, alliances, or even individual politicians can register to present a candidate list. Each voter casts a ballot for a most-preferred list.Footnote 7 After each list's votes are tallied, the HQLR formula is used to convert votes to a proportional share of seats within each district. Once each list's share of seats is determined, winning candidates are identified by their list positions. If a list wins one seat in the district, only its top candidate is elected; if it wins two seats, the top two are elected; and so forth.

Fragmentation in Hong Kong elections is driven by three related trends: the multiplication of political parties, splits within parties by which parties sometimes run multiple lists in the same district, and the proliferation of lists affiliated with the major political camps—pro-democratic and pro-Beijing—but under Nonpartisan labels. The combined effects of these phenomena are illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the vote share for lists within each camp and among non-aligned lists for each election since the current electoral rules have been in place.Footnote 8

Figure 1 Hong Kong LegCo elections: Party list vote shares by camp

The vote shares across the broad camps are consistent, with the pro-democracy side winning majorities of the overall vote. Note that for the 2016 election, Figure 1 shows the vote share for Localist candidates separately. This is to highlight that the success of Localist lists represented a conspicuous further increase in fragmentation in that election (which occurred as this article went to press). Post-election assessments, however, grouped the Localists broadly with the pro-democratic camp in the priority they place on elections, equal voting rights for all citizens, and the maintenance of political liberties in Hong Kong (Lam and Ng Reference Lam and Ng2016; Lau and Cheung Reference Lau and Cheung2016; Ng Reference Ng2016; Tong Reference Tong2016). For the purposes of subsequent analyses, therefore, I group the Localist lists from 2016 with the pro-democratic camp.

The most striking pattern in Figure 1 is the fragmentation within camps, starting in 2000 among the pro-democrats and increasing thereafter on both sides. The splintering reflects increasing divisions, both among parties and within them. In the 2000 election, for the first time, the Democratic Party ran multiple lists in New Territories East (two lists) and West (three lists) districts. By 2004, the ADPL joined the Democrats, splitting lists in Kowloon West, and in that same election, six of the pro-democratic camp's 18 seats went to nonpartisan lists that won a single seat each. By the 2012 election, the pro-Beijing DAB ran multiple lists in Hong Kong Island as well as New Territories East and West.Footnote 9

DISTRIBUTIONAL CONSEQUENCES: ELECTORAL EFFICIENCY, SIZE, AND SEAT BONUSES

Electoral efficiency means winning the most seats possible, given one's level of support in the electorate. Imagine a set of politicians who share a common purpose—whether to increase (or reduce) tax rates, to increase (or reduce) social welfare spending, to increase (or relax) environmental regulations—and who expect some level, X, of support for this platform among voters. For this set of politicians, maximizing electoral efficiency means converting X into the largest possible share of seats in the legislature. Under HQLR purchasing seats with remainder votes is always more efficient than purchasing them with full quotas. It follows that any group of politicians maximizes its efficiency by purchasing as many seats as possible by remainders and as few as possible by full quota. To win any seat by full quota is to over-pay.

Hong Kong politicians have learned this lesson well. Figure 2 shows the percentage of seats won by full quota among lists within each camp for each election since 1998. For the first three elections, both camps paid full price for about half of their seats, and purchased the other half at reduced prices, by remainders. The proliferation of lists that jumped most dramatically in 2008 corresponded to sharp reductions in the share of seats for which each camp paid full price. By the 2012 election, of the 34 seats captured by lists from the two major camps, only three were won by full quota, and in 2016, 4 seats were.

Figure 2 Percentage of elected LegCo seats won by full quota

Another way to think about electoral efficiency is in terms of whether the share of seats won by a party or a camp exceeds its share of the vote (a bonus), or falls short of its vote share (a penalty). Drawing on the district-level electoral data described above, I calculated the bonus for every party (and nonpartisan list) that contested any district-level elections in Hong Kong from 1998 to 2016. Figure 3 shows a series of plots, one for each election, of each party's overall vote share against its seat bonus. The smallest parties win some, albeit modest, vote shares and no representation and so, by definition, suffer penalties. Those penalties afford for surplus representation that is distributed across the parties winning seats. But how the bonuses are distributed illustrates the relationship between electoral size and electoral rewards. Each plot in Figure 3 includes the quadratic best-fit line, illustrating the shape of the vote-bonus function. In the first two elections, the function was convex, which is to say there were diminishing returns to scale. The largest parties did not necessarily win largest seat bonuses. By winning seats with full quotas, they were over-paying, and converting voter support into representation inefficiently. Efficiency was greatest for parties capturing moderate vote shares, between 5–15 percent, which were winning seats based only on remainder votes.

Figure 3 Seat bonuses by vote share in Hong Kong elections

Note also that the vote share of the largest party tends to diminish over time, from 43 percent in 1998, to 29 percent in 2000, to 21 percent in 2004, rising slightly to 23 percent in 2008, and falling again to 18 percent in 2012, and to 17 percent in 2016. This is no accident; rather, it is the result of the strategic response of politicians to the diminishing returns to size in the early elections under HQLR. When being big does not convey an electoral reward, politicians—even potential allies—are motivated to diverge rather than to coalesce. As the size of the largest parties diminishes, there are no more competitors who would ever pay full price for a seat. The vote-bonus function, which is sensitive to the strategic behavior of parties under HQLR, loses its convex shape. The proliferation of parties within each camp and, in some cases, the lists within each party, is a strategy to maximize electoral efficiency—never paying full price for a seat that could be won more cheaply, and ideally channeling surplus votes to other lists fighting for more or less the same set of policies.

Now consider how these incentives would have differed had Hong Kong used D'Hondt rather than HQLR. Figure 4 replicates the plots from Figure 3, this time simulating the outcomes that would have obtained had Hong Kong used the D'Hondt formula, which rewards size, providing economies of electoral scale, and conferring larger bonuses to larger parties. Note that the shape of the vote-bonus function under D'Hondt is consistently concave, even in the face of increasing party and list fragmentation. D'Hondt provides increasing return to scale, rewarding larger lists with larger seat bonuses at any level of list fragmentation, thus motivating politicians to form and sustain broad alliances.

Figure 4 Seat bonuses by vote share in Hong Kong elections—D'Hondt simulated results

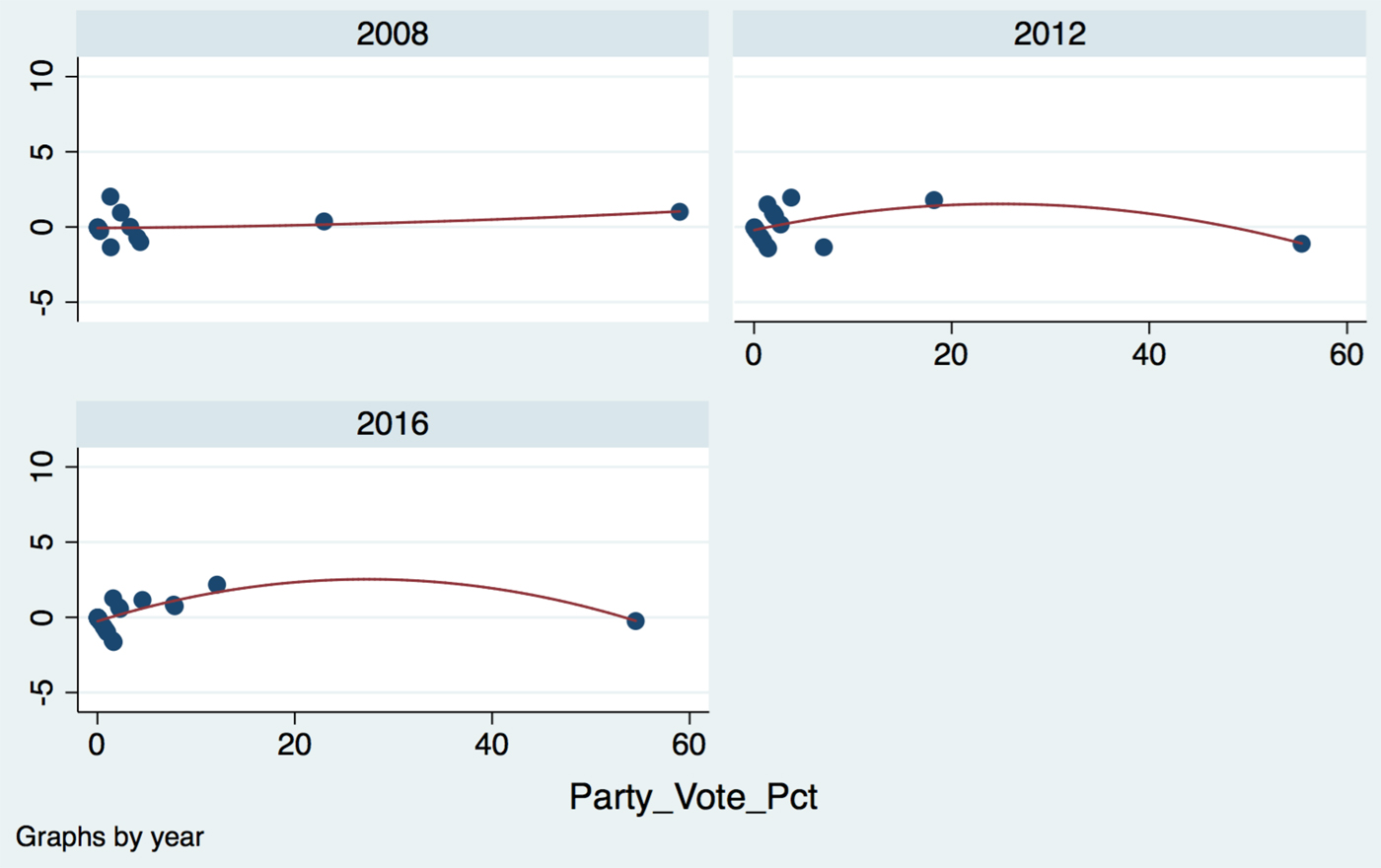

We can also simulate what would have happened to Hong Kong's electoral alliances under HQLR had they pursued unification rather than fragmentation. By 2008, for example, fragmentation reached its mature form among the pro-democratic camp, which won only one of its 19 seats by full quota. Figure 5 shows the analogous plots for the 2008, 2012, and 2016 elections conducted under HQLR, but this time with votes for all the lists from the pro-democracy camp pooled together within each district as if the pro-democrats had run unified lists.Footnote 10 The average seat bonus for such a broad alliance would have been zero, whereas much smaller lists (in these cases, pro-Beijing and non-aligned lists) would have captured larger bonuses.

Figure 5 Seat bonuses by vote share in the 2008, 2012, and 2016 elections—Simulation with votes from all Pro-Democratic lists in each district pooled

The lessons from these various exercises are consistent: Electoral efficiency under HQLR's dual-pricing system means avoiding paying full price for a seat. In each election to date, Hong Kong voters have confronted an increasingly cacophonous set of choices when they cast their LegCo ballots. This is not because political leaders are inherently individualistic or uncooperative. They are simply responding to the incentives generated by HQLR, where the optimal strategy is fragmentation. Under a different PR formula, incentives could push in the opposite direction, encouraging broad alliances in the HKSAR rather than fragmentation. D'Hondt is one option. Of the commonly used PR formulas, it rewards size the most. Other alternatives are also available (for example, the St. Lague divisors method), which are somewhat more generous to small and mid-sized lists while avoiding the dual-price system of HQLR. The key point is that, under other PR formulas, the imperative of electoral efficiency is to unify the largest possible vote share behind a common list.

DISCUSSION

The effects of PR for the directly elected seats in the LegCo have been widely noted by scholars, and the pioneering work by Ma and Choy has emphasized the specific effects of the HQLR formula. This article pursues that issue, highlighting the strategic response of Hong Kong politicians to HQLR and how electoral results would have differed under an alternative PR formula.

The implications of HQLR for Hong Kong politics are more profound than just whether more or fewer lists compete, and more substantive than whether lists pay for their seats with full quotas or remainders. The imperative to fragment means that politicians cultivate appeals to narrow constituencies and fight to pull votes away from close allies as tenaciously as they battle against the opposition camp (Lam Reference Lam2016). The imperatives that drive elections, in turn, are reflected in legislative process. Fragmentation undermines the alliances that are necessary for collective action within legislatures. Because the chief executive is not directly elected, the LegCo is Hong Kong's premier institution for electoral representation, but it is weakened by the fragmentation its electoral formula cultivates (Choy Reference Choy2013; Ma Reference Ma and Cheng2014).

This phenomenon was reflected most recently in the aftermath of the September 2016 LegCo elections, when the success of Localist lists raised vote fragmentation to new heights (Lam and Ng Reference Lam and Ng2016). One result is that, even as the aggregate outcome in 2016 was a repudiation of the pro-Beijing camp, Hong Kong political observers were skeptical that the pro-democratic side would be able to coordinate behind a common agenda within the LegCo (Tong Reference Tong2016; Wu Reference Wu2016). In the immediate aftermath of the election, Moody's issued a report warning that prospects for obstructionism and stalemate within the increasingly fragmented LegCo could prompt a credit rating downgrade for Hong Kong (Lockett Reference Lockett2016).

It is worth noting that the Hong Kong experience is not unique. During most of the twentieth century and until 2002, Colombia elected its House of Representatives using HQLR in 33 districts with an average DM around 5, akin to Hong Kong's. Like Hong Kong, Colombia allowed parties to run multiple lists in a given district—and split they did. In the Bogota district in 2002, 256 separate lists ran, none captured a full quota (5.6 percent), and all 18 seats were won by remainders (Pachón and Shugart Reference Pachón and Shugart2010). Splitting lists in order to capture seats by remainders rather than full quotas was such a staple strategy in Colombia that it was widely known as operacion avispas (operation wasps), to convey that a target was more effectively attacked by a swarm of small predators than by a single, larger assailant. Because Colombian legislators were in competition as much with other lists from their own parties as with other parties, they lacked incentives to cultivate broad party platforms that would make the legislature as a whole an effective policy-making actor.

With the goal of strengthening its Congress, Colombia adopted a reform in 2006 that made three important changes: switching the PR formula from HQLR to D'Hondt, limiting each party to one list per district, and allowing parties to run their single lists under either an open format—thus affording voters the opportunity to cast preference votes among candidates—or a closed format (Shugart, Moreno, and Fajardo Reference Shugart, Moreno, Fajardo, Welna and Gallon2007). Following the reform, the number of lists dropped (a forgone conclusion given the requirement of one list per party) and intra-party competition shifted from across split lists to within open lists (Pachón and Shugart Reference Pachón and Shugart2010). Notably, the correlation between the vote shares of the largest parties and their seat bonuses grew stronger (Shugart, Moreno, and Fajardo Reference Shugart, Moreno, Fajardo, Welna and Gallon2007, 222 and 252–253). The move to D'Hondt rewards economies of scale and broader electoral alliances united under a common banner.

The choice of PR formula is a technical matter but it can have profound effects on the behavior of politicians, the choices offered to voters, and the composition of the legislative alliances. The decision to adopt HQLR for Hong Kong's LegCo elections was momentous, and the effects were consistent with the goals attributed by Lau (Reference Lau, Hsin-chi, Siu-kai, Kin-sheun and Wong1999) to Beijing's electoral system designers, to impede the development of an effective pro-democratic block in the LegCo. Were Hong Kong to use a formula that encouraged alliance, rather than fragmentation, the LegCo's potential to represent broad interests within the Hong Kong policymaking process could be substantially stronger.

Appendix

Table A-1. Vote shares and number of geographical constituency seats won by camp and party, 1998–2016