Introduction

What is wealth, can we link it to inequality, and how can and should archaeologists measure or characterize it? The answer to these ‘simple’ questions usually involves the quantity, variety, and quality of excavated things. Does the presence of more things mean that people had a greater acquisitive capacity? Or should we consider the singularity of the things under study? Does wealth reflect social inequality when inequality stems from so many different social and cultural aspects besides the economic ability to acquire things? Considering inequality as a broad concept of social differentiation, differences in opportunity, and unbalanced power relations (Paynter & McGuire, Reference Paynter, McGuire, McGuire and Painter1991), this paper aims to discuss how pottery consumption can reflect such discrepancies based on patterns of different wares consumed in early modern Portugal.

The use of material culture to study wealth as a reflection of inequality is not new in archaeology and has been applied to many contexts and periods, especially concerning behavioural and cognitive aspects (e.g. Walker et al., Reference Walker, Beaudry and DiZeriga Wall2011; Kohler et al., Reference Kohler, Smith, Bogaard, Feinman, Peterson and Betzenhauser2017; Basri et al., Reference Basri and Lawrence2020). Here, we hope to go a little further by employing statistical analysis to find a simpler way to identify the level of wealth at a given site.

This article is based on the quantification of different types of ceramics which had different prices and perceived value through time and are found in a variety of archaeological contexts in varying quantities. It aims to discuss how this can be used to identify levels of wealth and consequently social influence and power that promoted social inequality in different contexts. To achieve this, the quantities of porcelain and tin-glazed wares in various contexts, distinguishing between Portuguese-made examples and imports, are compared. When pertinent, lead-glazed and unglazed wares are used for comparison.

We analysed the ceramic assemblages from fifteen archaeological sites in different locations. Ten of them are secular or non-religious and five are convents and monasteries. Religious institutions in Portugal were traditionally seen as places of wealth even though, canonically speaking, nuns and monks were meant to dispose of their earthly goods and adhere to principles of poverty, isolation, and obedience.

Our contexts range from the mid-sixteenth to the early nineteenth century, a lengthy chronological span also analysed in relation to political events, natural catastrophes, technological breakthroughs, and economic change. The pottery production itself was carefully considered: for example, in the mid-sixteenth century, Portuguese tin-glazed ware was seldom used in Portugal, but, by the mid-seventeenth century, it is one of the most widespread products and it was consumed in stable amounts until the early nineteenth century, when industrially-made European vessels, especially from Britain, entered the Portuguese market en masse. As for porcelain, it was copiously consumed in the mid-/late sixteenth century, diminished in popularity by the mid-seventeenth century, increased once again in the early eighteenth century, and only declined at the beginning of the nineteenth century. European imports also changed in value and quantity over time, depending on demand from international consumers and availability. Despite such indications, a narrower chronological evaluation of the production and consumption of these wares is difficult for early modern Portuguese wares since most of their shapes and decorations, especially for the cheapest objects, endured for decades. Jillian Galle noted the same problem when she tried to apply her abundance index to the early modern Atlantic world (Galle, Reference Galle, Heath, Breen and Lee2017).

These are just some of the issues we encountered. The ten non-religious sites included in this study are mostly areas of waste disposal from either a specific house or a close group of houses. These are: three sites in Lisbon (Largo D. Pedro IV (PIV), Encosta de Santana (ES), and Rua Nova da Trindade (NT)); Rua 5 de Outubro (ALH) in Alhandra; Museu Nacional Machado de Castro (MC) in Coimbra; and two sites in Almada (Rua Latino Coelho (LC) and Paços do Concelho (PC)). Dumps which associated with a broader residential area but not with specific dwellings were found in Carnide (CAR) in Lisbon, Rua dos Peixeiros (LAG) in Lagos, and Avenida 5 de Outubro (SET) in Setúbal.

Excavation and publication of religious contexts is still rare in Portugal (Gomes Reference Gomes2012: 38), although these large complexes and the number of people living in them tend to produce a great deal of archaeological evidence. Here, five religious institutions were considered for analysis: three female institutions, i.e. Santana in Lisbon (SC), Jesus in Setúbal (JC), Madre de Deus de Monchique in Porto (MADC), and two male institutions, at São João de Tarouca (SJTC) in central-northern Portugal and São Francisco (SFC) in Lisbon.

The data used came from different sources, mostly from publications or Master's dissertations (e.g. Gomes & Gomes, Reference Gomes and Gomes2007; Castro, Reference Castro2009; Sebastian, Reference Sebastian2010; Almeida, Reference Almeida, Arnaud, Martins and Neves2013; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Gomes, Almeida, Boavida, Neves, Hamilton, Arnaud, Martins and Neves2013; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Gomes, Casimiro, Garrigós, Fernández and Iñañez2015; Silva, Reference Silva2016; Casimiro et al., Reference Casimiro, Boavida, Detry, Senna-Martínez, Martins, Melo, Caessa and Cameira2017a, Reference Casimiro, Boavida, Moço, Nozes, Cameira, Banha da Silva and Caessab). In addition, information from sites studied directly by the authors was also included (NT, LC). Although the Lisbon area, being the most excavated and best published in the country, yielded the most information, we tried to include data from other parts of Portugal (Figure 1). All the sites, except for the religious institutions, were located in urban centres. There is currently not enough information from rural or interior areas to include in this analysis, and hence it is not possible to know whether different patterns of distribution and consumption applied to more inland sites.

Figure 1. Map of Portugal with the sites mentioned in the text.

Our statistical analysis of similarity is offered as a basis for discussing wealth differentiation. In a first stage, we consider three tableware types (porcelain, imported tin-glaze, and Portuguese faience), a type that tends to reflect wealth and economic status quite well; in a further stage, we include locally and regionally produced glazed and unglazed wares (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tableware used in the seventeenth century found in Carnide, Lisbon. By permission of the Centro de Arqueologia de Lisboa.

Statistical analysis is key to this approach since we seek to present a solid method that allows us to consider different scales of wealth. This is also important when analysing and comparing domestic dumps from different areas since it enables us to create maps of wealth distribution for particular areas of a city or even compare different regions with each other.

To define wealth differentiation, we established five levels, grounded in the number and quality of the objects and applied to any given context. This will also determine whether the presence or absence of pottery can be useful when trying to understand differences in wealth and, consequently, whether it is an indicator of social inequality.

Studying wealthy contexts might be considered easier for archaeologists since interpretations based on presence are always more straightforward than those based on absence. Furthermore, we tend to be drawn to a conventional dichotomy between rich and poor, which veers towards a reductionist perspective that only takes into account people who have everything versus those who do not. The statistical approach adopted here allows us to overcome such issues; instead we discuss different scales of ownership and consumption and how these reflect wealth differentiation and relational behaviours at different levels and not as opposites.

Overview

Our statistical focus on pottery consumption and on how it can be interpreted as an indicator of wealth is based on the assumption that different types of commodities had different values, something evident not only from the archaeological data but also from documentary information. It is not possible to give a full analysis of the consumption of all wares circulating in Portugal in the early modern age here, but a brief overview is given to emphasize the different values ascribed to certain pottery types.

Porcelain was a key luxury item from the East (Figure 3), and Italian and Spanish ceramics were of higher quality than Portuguese wares in the sixteenth century. Chinese porcelain was first imported into Portugal in the late fifteenth century (D'Intino, Reference D'Intino1992: 53), and from then until the twentieth century imports never stopped, even though quantities fluctuated (Henriques, Reference Henriques, Teixeira and Bettencourt2012). While the flux was constant, sixteenth-century items are frequently found in use in later contexts, which suggests that some of these artefacts had more than an economic value and could be treasured heirlooms.

Figure 3. Plate of Jiajing porcelain found in Rua Nova da Trindade, Lisbon.

Although the value of porcelain changed during the more than 400 years they were consumed in Portugal, and even though this was a widespread product, the archaeological evidence and the analysis of wills and probate inventories indicate that porcelain was always considered prestigious and a highly valued commodity (Hallet et al., Reference Hallet, Monge and Senos2018). Thus, it appears associated with wealthy contexts although smaller amounts are also encountered in lower economic contexts (Henriques, Reference Henriques, Teixeira and Bettencourt2012).

Before porcelain entered Portuguese daily life, the most abundant imports in Portugal were ceramics produced in southern Spain, especially in the Andalusian and Valencian areas (Figure 4). These are frequently found in deposits dated to as early as the fourteenth century (Gomes & Casimiro, Reference Gomes and Casimiro2013), and imports were consistent until the mid-/late sixteenth century, as attested by Sevillian Isabella polychrome wares, white plain, blue-on-white, and lustre wares from Seville and Valencia (Pleguezuelo, Reference Pleguezuelo and Flor2014).

Figure 4. Plate and bowl manufactured in Seville found in Rua do Arsenal, Lisbon. Photograph by permission of A. Valongo.

The quantity of Spanish wares is significantly greater than Italian wares in Portugal. Most finds of Italian ceramics are dated to the second half of the fifteenth or first half of the sixteenth century. These originate predominantly from the Montelupo workshops, with a few examples of vessels made in Venice, Pisa, and Deruta (Manso & Garcia, Reference Manso, Garcia, Russo and Sabatini2019) (Figure 5). The value of Italian wares seems to have been slightly higher than the Spanish imports and is often comparable to porcelain (Hallet et al., Reference Hallet, Monge and Senos2018). A 1596 probate inventory of Dom Teodósio indicates that a ‘normal size’ porcelain bowl cost 80 to 120 réis while an Italian plate of the same size, depending on its provenance (Pisa or Venice), cost from 60 to 120 réis (Hallet et al., Reference Hallet, Monge and Senos2018). A later inventory of Simão de Tovar (1683) lists the cost of a porcelain plate as between 80 and 100 réis (National Archive PT/TT/TSO-IL/028/11440). In 1841, when industrial pottery production was already established in Europe, a large porcelain plate cost around 200 réis (Braga, Reference Braga2012: 175). All things considered, the price of porcelain did not change much over time, and the slight price increase can be related to inflation (Oliveira, Reference Oliveira1985).

Figure 5. Plate manufactured in Montelupo found in Campo das Cebolas, Lisbon.

Photograph by permission of C. Manso.

Although other kinds of imported wares reached early modern Portugal, they are few: German stoneware was minimally imported and Dutch faience is hardly present. As for British imports, these only started to be significant in the Portuguese market in the very late eighteenth century (Casimiro et al., Reference Casimiro, Castro and Silva2021).

Here, we compare the imports with local and regional productions. Tin-glazed wares were the ultimate Portuguese table ceramics, made from the sixteenth to the late eighteenth century in three locations: Lisbon, Coimbra, and Vila Nova near Porto (Sebastian, Reference Sebastian2010; Casimiro, Reference Casimiro2013) (Figure 6). Since there was a limited number of production sites, their wares circulated over the entire country. They had different values, depending on their quality, and ranged from extremely ornate—sometimes rivalling porcelain—to very low-quality, utilitarian examples, although always superior to common wares.

Figure 6. Portuguese faience plate, kept at Gothenburgh museum. Photograph by permission of T. Wennberg.

Our purpose is not to discuss how these objects were acquired and consumed. Nevertheless, let us note that, while local wares were bought directly in the workshops, imported wares were acquired from several stores in cities (Brandão, Reference Brandão1990). As for convents, some of the objects may have been brought in by the nuns upon their entry or the convents bought them directly from the potters.

The Contexts

We do not present a detailed analysis of the fifteen archaeological sites under study since our main purpose is to conduct a comparative and critical analysis of the quantitative data. Nevertheless, we outline the sites’ general characteristics. We considered these sites not only in terms of ceramic quantities but also with respect to the social base and diet of their inhabitants, their architecture and location, as well as documentary and historical evidence. Different people lived in these sites; their origin, name, family, and commercial opportunities, among many aspects, had a huge impact on wealth differentials.

Secular contexts

The variation in wealth among non-religious sites led us to include ten such sites in the discussion as opposed to five religious institutions (Table 1).

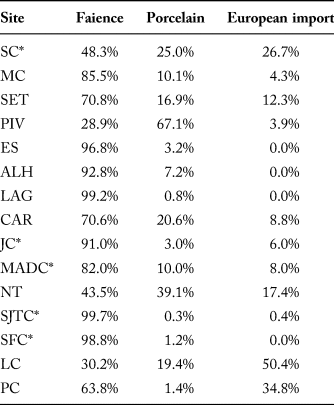

Table 1. Percentage of different types of wares per site. Religious houses are marked with an asterisk; all other sites are secular.

Some sites had general dumps associated with residential areas, described below. This is the case for Carnide (CAR), where 162 medieval storage pits were turned into dumps in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (c. 1550–1650). These reflect the daily use of ceramics and other material culture (Casimiro et al., Reference Casimiro, Boavida, Detry, Senna-Martínez, Martins, Melo, Caessa and Cameira2017a, Reference Casimiro, Boavida, Moço, Nozes, Cameira, Banha da Silva and Caessab). The material evidence found at Rua dos Peixeiros (LAG) in Lagos also originated from a storage pit transformed into a dump in the late seventeenth century (Oliveira, Reference Oliveira2010). At Avenida 5 de Outubro (SET) in Setúbal, the excavation of an area close to the medieval city wall revealed a dump with waste deposited during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Duarte & Silva, Reference Duarte and Silva2014). Excavation of the former bishop's palace in Coimbra by the Museu Nacional Machado de Castro (MC) uncovered an area that had been sealed by the building's refurbishment in 1592 and is interpreted as a dump from a less wealthy area of the palace (Silva, Reference Silva2016).

Some of our sites correspond to one or a small group of abandoned or destroyed houses. The excavation of a building at Rua Nova da Trindade (NT) revealed a kitchen abandoned between 1540 and 1560, when a cellar was filled with domestic waste (Casimiro et al., Reference Casimiro, Detry, Pinheiro, Nunes, Teixeira and Netoin press). An excavation at Rua 5 de Outubro (ALH) in Alhandra was interpreted as the remains of several houses built in the sixteenth century and destroyed in the early eighteenth century to make way for a church (Casimiro, Reference Casimiro2020; Henriques & Casimiro, Reference Henriques and Casimiro2020). The remains of a house were excavated at Encosta de Santana (ES); the house was destroyed by an earthquake in 1755 and most of its contents were found inside (Casimiro, Reference Casimiro2011). An excavation at Largo D. Pedro IV (PIV) in Lisbon revealed the remains of a house also destroyed in the 1755 earthquake. A courtyard, a kitchen, and a pantry were excavated, and the quantity of imported wares found suggests a wealthy environment (Henriques & Filipe, Reference Henriques and Filipe2020). In Rua Latino Coelho (LC) in Almada, the excavation of a house yielded the remains of a water cistern abandoned in the early nineteenth century. It may have belonged to a public establishment, possibly an inn. Also in Almada, the excavation of Paços do Concelho (PC) was inside a building that had been used as a prison at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The excavation discovered a water cistern abandoned and filled with much domestic refuse in a single event sometime between 1820 and 1830 (Reis, Reference Reis2021).

Religious contexts

The religious contexts we examined belong to three female and two male institutions. The convent of Jesus (JC) in Setúbal was founded in 1496 according to the rule of the Order of Saint Clare. Originally occupied by Spanish nuns, it soon housed the daughters of the local nobility and wealthy families. After the dissolution of religious orders in Portugal in 1834, the convent finally closed in 1888 when the last nun died (Almeida, Reference Almeida2012: 24; Reference Almeida, Arnaud, Martins and Neves2013). Lisbon's Santana convent (SC) was founded in 1562. This institution also belonged to the Order of Saint Clare and at one point was the largest religious house in the city, hosting hundreds of nuns. The 1755 earthquake wrecked part of the building and it was finally demolished in 1897 (Gomes & Gomes, Reference Gomes and Gomes2007; Gomes, R.V Reference Gomes, Gomes, Almeida, Boavida, Neves, Hamilton, Arnaud, Martins and Neves2013; Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Gomes, Casimiro, Garrigós, Fernández and Iñañez2015). In Porto, the Madre de Deus de Monchique (MADC) convent's main building was originally the house of the nobleman Pero da Cunha Coutinho before it was transformed in 1538 into a convent for nuns of the Order of Saint Clare until it closed in 1834. Excavations yielded a large collection of tableware dated to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Rocha, Reference Rocha2019: 20–22).

The convent of São Francisco (SGC) in Lisbon was a male institution housed in a large complex located on Monte Fragoso. It was founded in 1217 and underwent several changes through time, with a particularly elaborate construction phase in the early sixteenth century. Of its excavated assemblages, only faience, porcelain, and glazed wares have been studied, and European imports were found to be sparse (Torres, Reference Torres2011, Reference Torres, Teixeira and Bettencourt2012). Finally, we examined material from the monastery of São João de Tarouca (Viseu, in central-northern Portugal), a male institution founded in 1154 and probably the first of the Cistercian Order in Portugal. By 1834, when the monastery was closed, it was one of the most important religious institutions in northern Portugal. Excavations revealed several buildings of different phases, and thousands of ceramic sherds, including Portuguese faience, European imports, and porcelain (Sebastian & Castro, Reference Sebastian and Castro2008; Castro, Reference Castro2009; Sebastian, Reference Sebastian, Gomes, Casimiro and Gomes2016: 219).

Methodology

The methodology used followed a three-step process. First, the degree of wealth of different contexts was assessed from the ceramic assemblages present, the site's architecture and location, the diet of its inhabitants, and the documentary and historical records. We then constructed a ranking system consisting of five levels of wealth defined as the five baseline sites listed below. The choice of five levels was merely a starting point, a baseline that could be changed or adapted if needed. Second, we ranked the sites using statistical analysis of similarity. Third, we calibrated and validated the previous step by examining other ceramic types, such as glazed or unglazed wares, and undertaking a chronological analysis to assess whether the rankings reflect changes in social status over time.

Ranking

The first step involved generating a wealth ranking based on the information available for our fifteen contexts, using parameters that included the ceramics represented, the population's diet, the sites’ architecture and location, and the documentary and historical evidence. Its main purpose was to identify which sites could be used to create such a ranking. Our five baseline sites, one for each of five wealth ranks, are Largo D. Pedro IV (PIV, Lisbon, secular), Av. 5 de Outubro (SET, Setúbal, secular), Machado de Castro (MC, Coimbra, secular), Encosta de Santana (ES, Lisbon, secular), and Convento Santana (SC, Lisbon, religious). An explanation of how this ranking was achieved appears in the ‘Results’ section.

Once we had our baseline sites, we simplified our assessment of wealth according to three tableware types (porcelain, imported tin-glaze, and faience). We focused mainly on porcelain, given its quality and elegance, which reflects the social status of its owner, and the documentary information about its consumption and value. Chinese porcelain, being the most representative indicator of wealth in our approach, was therefore taken to be the main sign of the presence (or absence) of socially and economically differentiated groups in our contexts.

European imported ceramics, mainly from Spain and Italy, were chosen as our second indicator of wealth. When present in significant quantities in archaeological contexts, they can also indicate a wealthy environment. The third and last ceramic type considered was Portuguese faience.

We then determined the ratio of each of the three ceramic types for each of the ranked sites. The ratios for each of the five baseline sites were what allowed us to conduct statistical analyses in our next step.

Statistical similarity

The analysis undertaken in the second step used a statistical approach known as the Brainerd-Robinson Similarity Coefficient (Brainerd, Reference Brainerd1951; Robinson, Reference Robinson1951). This is one of the numerous coefficients of similarity that can be used to compare archaeological evidence from different sources. According to some scholars, the greater the archaeological ‘similarity’ score between contexts, the greater the probability that the human behaviours which resulted in this evidence were equivalent (Peeples et al., Reference Peeples, Mills, Haas, Randall, Jeffrey, Roberts, Brughmans, Collar and Coward2016: 62). The choice of the Brainerd-Robinson method was based on its simplicity and because it facilitates the comparison of percentages of material evidence.

The similarity (S) calculation between two contexts, ‘a’ and ‘b’, used the following formula:

Thus, k = ceramic types; Pak = percentage of ceramics k in context ‘a’ and Pbk = percentage of ceramics k in context ‘b’.

The index can range from 0 to 200, 0 being the total absence of similarity between contexts and 200 the total statistical parity. Therefore, contexts that have a higher score will have a higher equivalence from a material evidence perspective and can be considered similar, which in the case of the contexts under study indicates their wealth and similarity in social status.

Thus, taking our five baseline sites within our ranking as reflecting the ratio of the three ceramic types listed previously, we could, using the Brainerd-Robinson Coefficient, employ these ratios to rank all the remaining contexts according to their ability to acquire ceramics. This made it possible to gain an idea of the level of wealth at each site.

Comparative analysis

In a third step, similarly ranked archaeological sites were analysed more comprehensively, based on information from other sources. In addition to counting ceramics, we considered other cultural, economic, and social aspects. This was important because even when using statistical similarity calculations to rank the contexts, a purely quantitative analysis can be insufficient; despite the exactitude of the numbers, they do not always allow us to distinguish between characteristics such as the artefacts’ perceived quality. We therefore combined the statistical results with data obtained by other research and from direct observation of the assemblages. Our purpose was to reveal a finer-grained picture of the respective contexts’ social and cultural character, including their urban location, the social origin of their inhabitants, their daily habits, or their religious beliefs.

Results

Our first step was to establish a ranking reflecting five levels of wealth by identifying the ratio of three ceramic types (porcelain, imported European ceramics, and Portuguese faience) for each of our sites (Table 1). Subsequently, we recalculated their respective ratios (Table 2).

Table 2. Percentage of the three types of wares used in the comparative analysis. Religious houses are marked with an asterisk; all other sites are secular.

Archaeological evidence concerning the nature of the sites and their assemblages and the ratios of the three selected ceramic types (expressed as percentages of porcelain, European imports, and faience) helped us to define the following five archaeological sites as the baseline for each level of wealth:

-

Rank 1: Largo D. Pedro IV (Lisbon): 67% porcelain, 4% European, 29% faience

-

Rank 2: Convento Santana (Lisbon): 25% porcelain, 27% European, 48% faience

-

Rank 3: Av. 5 de Outubro (Setúbal): 17% porcelain, 12% European, 71% faience

-

Rank 4: Machado de Castro (Coimbra): 10% porcelain, 4% European, 86% faience

-

Rank 5: Encosta de Santana (Lisbon): 3% porcelain, 0% European, 97% faience.

Having defined the baseline sites, a Brainerd-Robinson Similarity Coefficient between sites was calculated (Figure 7). A colour code was used to identify the degree of similarity. Dark blue indicates a significant similarity between sites (e.g. between Encosta de Santana (ES) and Lagos (LAG)), while dark red indicates a very low degree of similarity (e.g. between Largo D. Pedro IV (PIV) and Lagos (LAG)). Using these similarity values, our contexts were classified according to their correspondence with the ranked baseline sites; as a first iteration, the sites with values above 190.0 were considered similar.

Figure 7. Brainerd-Robinson Similarity Coefficients between sites. Dark blue: significant similarity; dark red: low similarity.

Figure 7 shows that Largo D. Pedro IV (PIV) in Lisbon has the highest level of wealth and is unlike any other site (i.e. no dark blue), with very significant differences when compared to all the other contexts. The same appears to hold for the Convento de Santana (SC) in Lisbon, the second highest, where no values with similarities over 190.0 were identified. For the other levels, the scenario changes. At the third level of wealth, Avenida 5 de Outubro in Setúbal (SET) has a very high level of similarity (192.6) with Carnide (CAR). For the fourth level, Machado de Castro in Coimbra (MC) is very similar (192.7) to the Convento de Madredeus in Porto (MADC). Finally, for the fifth level, we can associate Encosta de Santana (ES) in Lisbon with several sites: Alhandra (ALH) (192.0), Rua dos Peixeiros in Lagos (LAG) (195.2), the monastery of São João de Tarouca (SJTC) (193.7), and the convent of São Francisco in Lisbon (SFC) (195.9). As discussed later, these rankings may change when further information is added.

The sites of the convent of Jesus (JC) in Setúbal and Rua Nova da Trindade (NT) in Lisbon could not be ranked with similarities of over 190.0, and hence could not align with the five predetermined levels, falling ‘in-between’. The convent of Jesus (JC) has similarities between 180.0 and 190.0 with all the sites ranked in the fourth and fifth level of wealth; therefore, even without a direct association, we can rank it between levels 4 and 5 (perhaps 4.5), a conclusion reached during the study of the site (Almeida, Reference Almeida2012). The same logic was applied to the house in Rua Nova da Trindade (NT) in Lisbon, which has the highest similarity (171.7) with the Convento de Santana in Lisbon (SC; rank 2) and is most similar (144.1) to Largo D. Pedro IV in Lisbon (PIV; rank 1). Therefore, the Rua Nova da Trindade (NT) house's wealth must have ranked between levels 1 and 2 (e.g. 1.5). This may indicate that further levels need to be defined and that wealth may not be so easy to distinguish from statistics alone.

The level of wealth at eleven sites is supported by evidence from historical and archaeological investigations. The exceptions are the monastery of São João de Tarouca (SJTC) in Viseu, the convent of São Francisco (SFC) in Lisbon, and the sites of Latino Coelho (LC) and Paços do Concelho (PC) in Almada. The two monasteries cannot be classified as belonging to level 5 since they were wealthy; nor can the Latino Coelho (LC) house and the Paços do Concelho (PC) site be ranked at the same level since historical and archaeological studies suggest that both sites had different levels of wealth. All these sites will be discussed below.

Discussion

Analysing differences in wealth is always complicated. While large quantities of objects in a given context may indicate an ability to acquire material goods, it may not be that simple. Our discussion focuses on the differences in the objects that a given house, group of houses, area, or religious institution acquired and how they can reflect discrepancies in the ability to acquire things. Defining and discussing similarities between contexts makes it possible to visualize which instances are more alike than others and classify them into one of five possible levels of wealth. Nevertheless, we must also consider other issues.

Looking at the similarities more broadly, we note that no religious context is as wealthy as a wealthier domestic setting, but it is also never as poor as the poorest secular site. Though this can lead to different interpretations, this may reflect the fact that all religious houses were dependent on the Church and religious orders. These institutions were responsible for conventual and monastic regulations, i.e. they would always support their dependent religious houses and would not let them fall into complete poverty. This may seem to contradict the fact that, in Figure 7, the monastery of São João de Tarouca (SJTC) and the convent of São Francisco (SFC) show a high level of similarity with level 5 sites (see further discussion below). On the other hand, large convents such as the Santana convent (SC) may have been generally wealthier than, say, a merchant's house; the available data, however, suggests that sites like the Largo D. Pedro IV (PIV) house were proportionally wealthier.

When comparing sites, difficulties are also encountered when contexts do not share a cultural environment. Thus, it would be inappropriate to include in this analysis a fifteenth-century context, given that porcelain rarely reached Europe at that time. The same can be said for post-eighteenth-century contexts. The vast quantities of European ceramics imported into Portugal from the 1780s onward make it impossible to compare sites formed before and after the industrialization of ceramic production. While thirteen of our sites predate 1760, two sites in Almada (Rua Latino Coelho (LC) and Paços do Concelho (PC)) post-date 1780, making their results incompatible with the pre-1760 sites. But, when compared with each other, Rua Latino Coelho (LC) is wealthier than Paços do Concelho (PC). This indicates that the method used here works when dealing with contexts that probably belonged to social groups with comparable behaviours and consumption patterns.

Level 5 in our scheme does not show any evidence of imported European wares (Table 2). It is also associated with a very low percentage of Chinese porcelain. We are confident that we did not miss identifying places where porcelain was found, even in very small amounts, in our search of archaeological publications referring to sixteenth- to nineteenth-century Portugal; but such publications are a fraction of all the excavations conducted. Although no absolute conclusions can be drawn, we believe that porcelain, despite being an expensive item, circulated widely, and imported European ceramics were difficult to acquire even if their price was similar to that of eastern imports, at least until the late sixteenth century (Hallet et al., Reference Hallet, Monge and Senos2018).

All the sites under study provided data on wares in daily use. Glazed and unglazed vessels were used for cooking, storage, and drinking, among other household activities. The data revealed that the ability to acquire ceramics was greater in wealthy contexts: they contained a greater quantity of tableware and other objects, as is evident from dumps such as those excavated at Carnide (CAR). When analysing the objects found inside wealthy houses at the time of their abandonment, the quantity of tablewares (porcelain and tin-glazed) is much higher than unglazed or lead-glazed wares. This may indicate that fine wares were kept but that coarse wares were discarded when they developed a minor fault, as suggested by the substantial amounts of these wares in the dumps ranked above level 2.

At the poorest level, rank 5, coarser wares likely continued to be used even when slightly broken or defective, as suggested by their small ratio in level 5. Exceptions nevertheless exist: the Machado de Castro (MC) assemblage proportionally had a large number of unglazed wares. Why this should be so is difficult to determine but it may be that the area, although located in the poorest part of the bishop's palace where servants lived, received waste from the palace itself. Alternatively, the assemblage was wealthier than its level 4 ranking, which takes us to the next point.

The comparison between secular and religious contexts seems possible with the method used in this paper, as it establishes different rankings of wealth for each. But, when we compare religious contexts with each other, differences between female and male religious institutions emerge. In terms of quantity, it seems that male institutions did not consume high quantities of imported wares and instead opted for local and regional high-quality products. Female convents, on the other hand, were among the highest consumers of porcelain and of varying amounts of European imports. The idea that porcelain consumption may be gender-related in religious houses has been aired before (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Gomes, Casimiro, Garrigós, Fernández and Iñañez2015); an alternative explanation is that the wealth ranking used here might not work for religious male orders. This would explain why São João de Tarouca (SJTC) and São Francisco (SFC) are ranked at level 5 although they were wealthy institutions. We should therefore seek to develop other ways of assessing the wealth of male religious institutions.

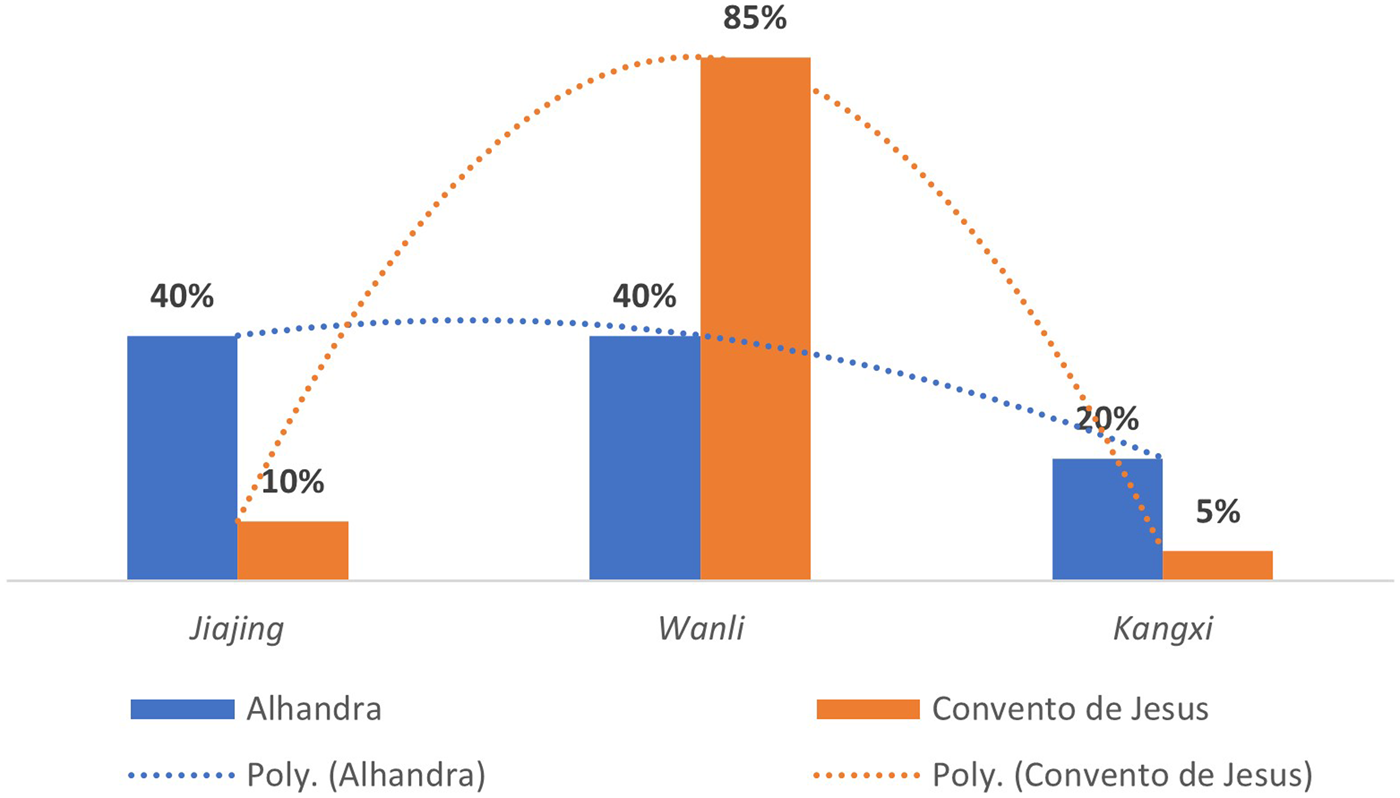

One of the most significant absences in published studies is a diachronic analysis of vessel consumption. Sites tend to be attributed to a general period, such as the seventeenth century, without considering the many variations in patterns of importation and pottery consumption within a hundred years and overlooking the fact that sites can vary alongside the behaviour of their occupants. In this study, we could evaluate the chronology of the complete assemblage of imports in only five sites. The typology of porcelain can provide additional information concerning production dates. At the Encosta de Santana (ES) house, the only identified porcelain find was produced in the late sixteenth century, giving an initial Wanli period date; its context, however, was dated to 1755. Other instances include Alhandra (ALH) (with eleven datable sherds), Rua Nova da Trindade (NT) (eight sherds of Jiajing type), and Carnide (CAR). At the convent of Jesus (JC), thirty-five out of the forty-one porcelains are Wanli products, interpreted as an indicator of the convent's growing wealth in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century (Almeida, Reference Almeida2012). The absence of published studies precludes analysis of chronological developments within similarly ranked sites, except in two cases (Figure 8). It illustrates the variations in wealth in two similar contexts during the same period.

Figure 8. Comparison of porcelain types from two contemporary sites.

Conclusion

Our study consists of a similarity analysis of fifteen early modern contexts associated with five levels of wealth. While the method used identified certain patterns, it is not universally applicable. When assessing wealth based on porcelain and imported wares, male religious institutions, such as São João de Tarouca and São Francisco, cannot be included since it seems that porcelain consumption may have been gendered and thus not entirely indicative of status. Female religious houses, on the other hand, were among the highest consumers of porcelain and European imports; the many women living in convents who were not called to be nuns reproduced their original social structures and levels of wealth within the convent walls. From this we conclude that analyses of similarity between sites must be made for contexts that have similar consumption patterns. Thus, we cannot directly compare pre-industrial with industrial consumption.

When choosing our sites, we attempted to cover different areas in Portugal and site types. If levels 1 and 2 are considered wealthy and 4 and 5 relatively poor, the conclusion from this analysis would suggest that it is easier to find less wealthy sites than wealthy ones. While the houses at Largo D. Pedro IV and Rua Nova da Trindade in Lisbon, and the convent of Santana, also in Lisbon, are the wealthiest, there are two mid-level sites (Carnide and Setúbal), and six poorer examples. When comparing this information with the documents available for early modern Portugal, it is unsurprising to find that most of the population was not wealthy enough to acquire large quantities of imported material. While porcelain and European ceramics were widely available, most people could only acquire small quantities of them.

While it is tempting to conclude that inequality in consumption can be related to people's socioeconomic capacity for acquisition, it is not always that easy to demonstrate it directly or define it through archaeological analysis. This is what we have aimed to do here. By quantifying different types of ceramics which we know from historical documents to have had different values, it is possible to build a narrative indicating that ceramics can demonstrate different levels of wealth and the ability (or not) to acquire such objects. We learned from this study that applying similarity analysis to every site requires further critical reflection, and other ways of assessing wealth must be considered.

Consequently, the conclusions presented here are preliminary. We would have liked to include more sites and demonstrate that differences in wealth can be revealed more effectively when comparing consumption behaviour in different places. Thus, further formulae and methods for understanding wealth in male religious institutions, for instance, are needed. Moreover, we need to examine more examples to establish whether wealth can be calculated from porcelain ratios or if some other formulas must be devised. We believe that numerous avenues of research are open and that it is important to consider how archaeology can help us understand the diversity of lifeways in early modern Portugal. That some people were wealthier than others is clear from the archaeological record. We have been able to characterize and understand it in a generalized way through one facet of material culture (ceramics) but other topics, such as an analysis of regional differences, or an examination of wealth within urban centres and their relation to the urban landscape, are equally deserving of further study. Using other types of material culture to assess wealth is another path that could be followed, allowing for further methodological refinement of methods such as the similarity coefficient presented here. Ultimately, we shall reach a better understanding of wealth disparity and dynamics in early modern Portugal.