1 Introduction

One barrier to the cumulation of knowledge in political science is the fact that researchers have limited visibility into the full set of research designs that scholars have conceptualized, implemented, and analyzed. This reality is a function of many different factors, including a lack of transparency around planned research; selective reporting and publication of scientific findings; and the sheer difficulty of seeing research designs through from data collection to publication. Although understandable, the inability to observe all research that is being done has a number of unfortunate consequences. First, it is likely that the effect sizes we report are biased upwards, given well-documented patterns of publication bias. Second, efforts to evaluate what we know (and do not know) in particular areas of the discipline are incomplete, particularly since many unpublished studies likely yielded null results. Third, a significant volume of time, energy, and resources are wasted on studies that might have been designed differently or not implemented had researchers been aware of the full body of undertaken but unpublished research.

In the midst of a “credibility revolution” in the social sciences, the discipline is making strides in addressing a number of these issues. In particular, there is now widespread acceptance of practices that facilitate greater transparency for data and research designs. However, while researchers have long acknowledged the challenge of providing visibility into null results (e.g., (Laitin Reference Laitin2013; Monogan III Reference Monogan2013; Rasmussen, Malchow-Moller, and Andersen Reference Rasmussen, Malchow-Moller and Andersen2011; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1979), the main ideas that have been floated to tackle this issue, including the widespread use of preregistration, a review process that accepts papers based on research design alone, and a high prestige journal that publishes null results, have proven inadequate or difficult to implement in practice.

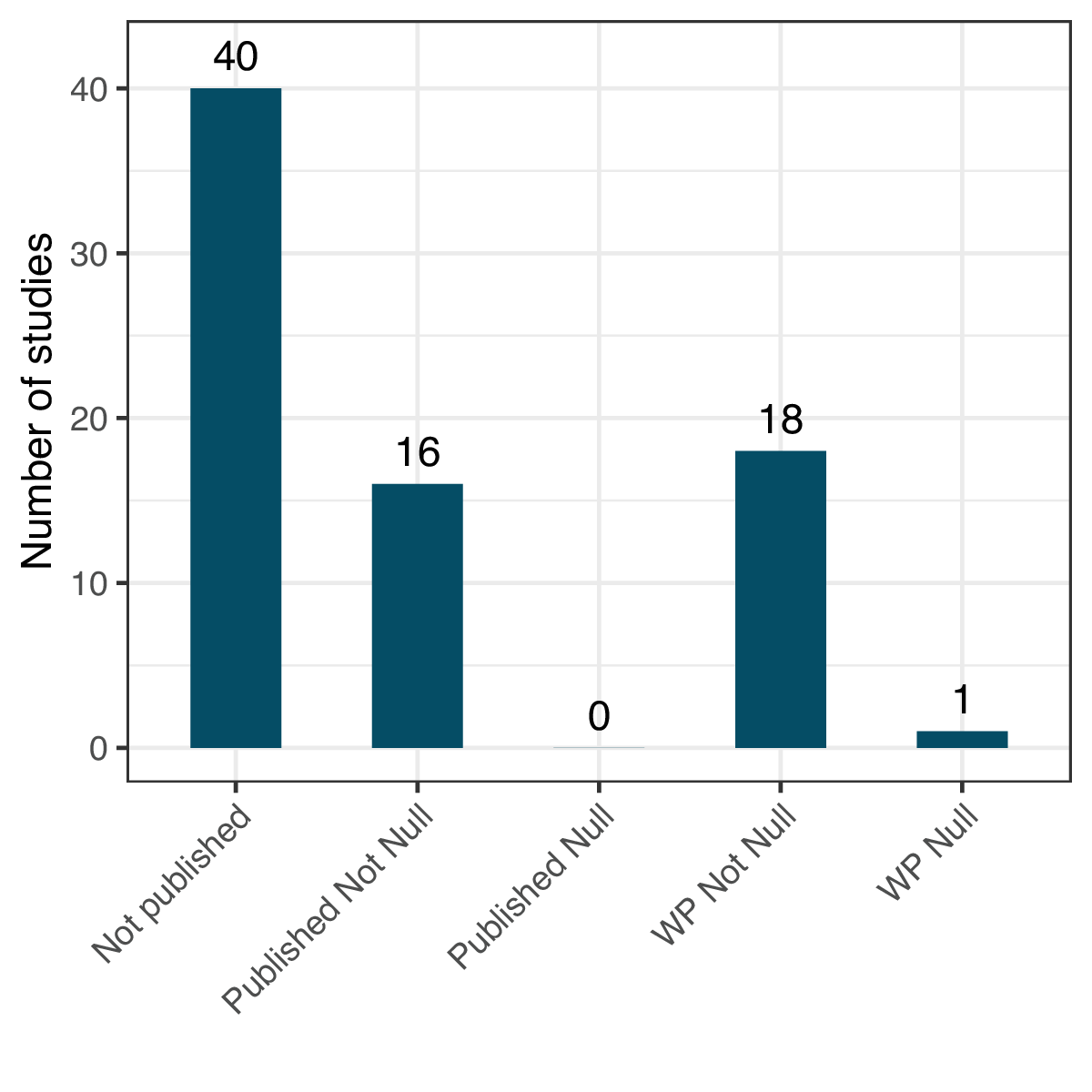

We provide one example of this problem using data from pre-registered studies on the American Economic Association (AEA) registry that relate to a large, policy-relevant literature on information “nudges.”Footnote 1 Of 75 such studies registered, Figure 1 shows that 40 had no publicly available working papers or publications by the end of October of 2020. Of the remainder, 16 were published and 19 had working papers available online. None of the 16 published papers reported primarily null results, and only one of the 19 working papers did so. While some of the 40 studies with no publicly available results were probably unfinished, it also seems very likely that this research includes many more null results than the studies visible to the research community. This bias makes it more difficult for academics and practitioners to cumulate knowledge about when nudges work and why—a challenge that extends to many other bodies of research.

Figure 1 Visibility of nudge results from AEA pre-registered studies.

We propose that the problem can be addressed most effectively through the development of a new disciplinary norm in which scholars routinely report null results that they cannot or do not wish to publish through the peer-review process. This proposal is particularly but not solely relevant for preregistered, experimental studies. We highlight the emergence of data sharing and registration norms to argue that widespread reporting of null results can be encouraged through a bottom-up strategy that leverages the ability of well-defined research communities (such as labs and departments) to set common standards and expectations for their members. To reduce the costs of adopting this practice, we also outline a template that can be used by other researchers to report null results efficiently online, and we highlight its utility by applying it to two examples from our own work. The article concludes with a brief discussion of additional challenges and opportunities for developing a norm of null results reporting.

2 The Discipline’s New Practices: What they can and cannot Accomplish

The discipline of political science is undergoing significant changes, and some of the most important developments relate to how we operate as a scholarly community that is committed to generating cumulative knowledge. Two advances merit particular mention. First, a growing awareness of how the publication process warps the research process has led to changing norms for quantitative and experimental research in particular. Scholars are making research designs more transparent, which helps to reduce incentives created by the publication process to report statistically significant findings discovered post hoc. As one example, preanalysis plans (PAPs)—in which researchers register their designs prior to accessing the data—are increasingly the norm in experimental research (e.g., Casey, Glennerster, and Miguel Reference Casey, Glennerster and Miguel2012).Footnote 2

Second, there is greater appreciation of the value of replication as a core element of the discipline’s effort to advance knowledge. This is facilitated by the increasingly widespread practice of posting data from published studies (e.g., Key Reference Key2016). At the same time, there is growing recognition of the value of replicating research designs across multiple populations and contexts, especially with the micro-turn in political science. Research communities increasingly look for multiple, similarly designed studies as evidence of the robustness of a given finding (Dunning et al. Reference Dunning, Grossman, Humprheys, Hyde, McIntosh and Nellis2019).

Despite this progress, our ambition to cumulate knowledge in political science is still held back by our inability to observe the full population of research studies on a given topic. Even if we improve the quality of our inferences and test the robustness of published results, it is difficult to evaluate the state of knowledge in our field when we cannot account for studies that have been carried out, but whose results are not visible. Often, the studies that remain invisible are the ones that yield null results, suggesting a systematic bias in the research we observe. While PAPs represent a step forward in making visible a much broader population of studies, scholars are left to make educated guesses about whether the absence of a published paper is evidence of a null finding (Ofosu and Posner Reference Ofosu and Posner2020), which is unlikely to prove efficient.

3 Making Null Results Visible: Existing Approaches

Franco, Malhotra, and Simonovits (Reference Franco, Malhotra and Simonovits2014) illustrate the extent of the problem and why it is difficult to address. Using the full population of studies selected for funding through the National Science Foundation’s Time-sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences (TESS) program, the authors show that strong results are 40 percentage points more likely to be published than are null results and 60 percentage points more likely to be written up. In part, they interpret this as evidence of publication bias. Statistically significant findings are more likely to be published, even controlling for the quality of study designs. But they also argue that researchers are making choices that exacerbate this problem. Researchers are less likely to write up studies if they find insignificant results. Part of this reflects a perception that such papers will be rejected, but it also appears to be the case that researchers “lose interest in ‘unsuccessful’ projects” (Franco et al. Reference Franco, Malhotra and Simonovits2014). Similar patterns have long been observed in other disciplines, such as medicine (e.g., Easterbrook et al. Reference Easterbrook, Gopalan, Berlin and Matthews1991).

These findings speak to the more general challenge that must be addressed to make progress on the reporting of null results. The sharing of null results is helpful to the discipline, but potentially harmful to the individual scholar, who must weigh the cost of writing up a study against the perception of a low return, both in terms of publication and reputational enhancement. Combating publication bias thus requires a serious effort to address the disciplinary incentives that are misaligned with our goal to cumulate a body of knowledge.

Two ideas have been advanced as a solution to this challenge, but both have run into significant hurdles in practice. The first involves editors of journals committing to a review process that evaluates studies on the basis of their research design rather than their results. This process would ensure that reviewers are not making judgments about quality or appropriateness for the journal as a function of the findings, but instead focusing on the quality of the research design and measurement strategy. The editors of Comparative Political Studies were an early adopter of this approach, which they agreed to pilot in a special issue in 2016 (Findley et al. Reference Findley, Jensen, Malesky and Pepinsky2016). Perhaps unsurprisingly, although this review process yielded an issue with several null findings, the editorial board abandoned this idea, as it turned that results-free publication would not fully protect the publication process from “data fishing,” would increase the difficulty of reviewing analysis adequately, would complicate the process of identifying important findings, and would inhibit the publication of nonexperimental research. As a result, they said they were “not likely to repeat” the process in their journal (Tucker Reference Tucker2016).

A second proposal has been to develop high-prestige journals for reporting null results, or to have leading journals publish annual issues devoted to null results (e.g., Laitin Reference Laitin2013). Despite these ideas being in circulation for many years, there have been few concrete efforts to follow through. Why has it been so difficult? Beyond the disincentives that individual scholars have to write up null results, it also likely takes a unique individual who is willing to trade off research or editing opportunities elsewhere to build and oversee a journal focused on reporting so-called “unsuccessful” studies. Furthermore, the challenge of evaluating these studies is not insubstantial, as null results may be a function of any number of factors, including but not limited to research design, measurement, power, the failure of a theoretical prior, implementation, and context. A journal of null results would likely be overwhelmed with a high volume of poorly designed and implemented research, making it challenging to organize the volume of reviewers needed to manage the flow of manuscripts. We share the view of many that creating outlets for publishing null results would be a good thing if it could be made incentive compatible for publishers and editors. But we also are convinced that the publication process alone will not solve the problem.

In addition to these two proposals, some scholars have suggested registration as a solution to publication bias. Monogan (Reference Monogan2013) hypothesized that widespread registration of PAPs could make null findings more publishable by making them more credible, but the persistence of the problem despite the growth in registrations implies this has not taken place. Rasmussen et al. (Reference Rasmussen, Malchow-Moller and Andersen2011) propose that registries could help to overcome publication bias if they were expanded to include reporting of results after studies were implemented. Duflo et al. (Reference Duflo, Banerjee, Finkelstein, Katz, Olken and Sautmann2020) also suggest that researchers should write short reports post-PAP that summarize all results from the prespecified analyses. We believe this approach is important and should be pursued by political scientists as part of an effort to make null results more accessible. However, without a norm of reporting null findings, this practice has not taken off, despite the fact that commonly used registries offer fields in which authors could report their results. For instance, of the 3,989 studies in the AEA registry as of October 2020, only 20 (0.5%) included preliminary reports on results (other than research papers) while only 394 (10%) linked to working papers or publications.

4 A Bottom-Up Approach: Developing a Norm of Null Results Reporting

As discussed above, the ability to cumulate knowledge in political science has been improved substantially by a shift toward greater transparency of data and research design. In both cases, this improvement has been driven by bottom-up efforts to inculcate new disciplinary norms around the specific practices of sharing replication data for published studies and registering PAPs for quantitative and especially experimental studies. Individual scholars advocated for and engaged in these practices, developed common expectations for how they should be used, and gradually convinced powerful disciplinary institutions—such as top journals and funders—to adopt standards that would further incentivize their spread (King Reference King2003; Nosek et al. Reference Nosek, Ebersole, DeHaven and Mellor2018).

Based on the success of this model, we propose that the challenge of making null results more visible can be addressed most effectively by establishing a norm of researchers reporting results that they cannot or do not want to publish through the peer-reviewed process. Specifically, we envision scholars posting brief “null results reports” to public repositories online that summarize their findings and discuss implications for future research. While this reporting norm could be extended to studies whether they return null results or not, we focus here on null results because publication bias makes them particularly likely to be relegated to the file-drawer. This norm can also be applied to research of all types, including experimental and nonexperimental quantitative studies and also qualitative work. However, as a first step, we believe this practice should become standard for experimental studies where researchers develop explicit hypotheses prior to collecting their data.

We recognize that researchers may be reluctant to adopt this practice because of time constraints and concerns about reputational costs for revealing results that did not turn out as expected. Given these challenges, how can this norm be encouraged? First, the success of replication data and PAPs suggests the importance of well-defined research communities—ranging from departments and labs to subfields and methodological groups—taking steps to establish standards for their own members. These communities are ideal settings in which to set expectations about what it means to contribute to the discipline or to a field and to organize practices that are consistent with our broader goals as a scholarly community. The actions taken by one research community can also create important examples for other communities to emulate. Research groups committed to the cumulation of knowledge can contribute to this goal by recommending or even requiring their members to report null results publicly.

We have taken steps to begin creating such an environment in our own research community. The authors are all either directors, staff, or fellows of the Immigration Policy Lab (IPL), a collaborative research team at Stanford University and ETH Zürich focused on building evidence and innovation in immigration policy. As a lab, we are requiring our research team to adhere to a set of guidelines (Supplementary Appendix A) that defines our policy for reporting null results for every preregistered study. The reports will be posted as pre-prints on platforms such as SocArXiv, SSRN, or OSF, in addition to being posted to a null results repository on the IPL website. By embedding this norm shift in our scholarly community, we hope to set an example that other research communities can follow, while also reducing any reputational risk associated with running studies that yield no statistically significant findings—something we have all done repeatedly, but tend not to discuss.

Second, in order to reduce the time investment needed for posting results, we have also developed a template that researchers can use when drafting a null results report. The template first asks for brief language on the research design and basic findings, and then prompts the researcher to discuss the major factors that might account for the null results. Because these results can be difficult to interpret, we believe this component is of particular importance. As a result, we outline a set of issues that each report should ideally explore as possible explanations for the null findings, including: (a) statistical power, (b) measurement strategy, (c) implementation issues, (d) spillover and contamination, and (e) flaws in the theoretical priors. Finally, the template asks researchers to briefly consider implications for future studies, whether suggestions for improving research design or implications for the academic literature. We wish to note that several of these components are already included in most PAPs or completed during analysis of the results, further reducing the required time investment. The template thus provides academics with a formulaic and relatively quick method for informing the scholarly community about the design, findings, and interpretation of their studies.

Our hope is that these reports will become a norm that enables scholars to build on prior work and adjust their beliefs to reflect the reality of both published and unpublished studies. Also, given the policy-relevant research of some political scientists, we anticipate that the benefits of revealing null results will extend beyond the academic community as well. Below, we outline two examples of IPL projects that returned null findings and whose publication in the form of null results reports we believe offers a learning opportunity for the political science community. The two full reports are included online as Supplementary Appendices B and C.

5 Applications: Naturalizations in New York and Syrian Refugees in Jordan

Following our example in the introduction, the first project speaks to a large literature on the role of information “nudges” in addressing behavioral obstacles to individually beneficial outcomes. This is a large theoretical and empirical field that has prompted much field experimentation, and one where the risk of simply not observing null findings in the scholarly literature and overestimating causal effects is substantial.

Building from an earlier study which found that a simple information nudge could increase naturalization rates (Hotard et al. Reference Hotard, Lawrence, Laitin and Hainmueller2019), IPL researchers designed two enhanced nudges to help close the gap between naturalization intentions and naturalization among low-income lawful permanent residents in New York.Footnote 3 The first treatment group received substantially more information and better formatting than the simple information nudge given to the control group. The second treatment group received the same information along with an opportunity to schedule an appointment for an upcoming citizenship workshop where they could receive assistance completing their naturalization applications. Each of these were relatively low-cost interventions and evidence of their efficacy would have the potential to shape existing naturalization programs and our understanding of the conditions under which nudges work. However, neither of the nudges produced a discernible increase in citizenship application rates over the simple information nudge administered to the control group.

The null results report systematically reviews possible explanations for these findings. One potential explanation is that the study did not have enough power to detect a small effect, even though a small effect would have been meaningful for those seeking to increase naturalization rates. The study was powered to detect larger effects, similar to the magnitude identified in other studies in this area. A second key concern is that the design of the invitation treatment was limited in scope. All of the participants in the second treatment group had to choose from appointment times at only one location and only one date. A different treatment with more options and flexibility might have driven higher rates of follow-through. On the theoretical side, the researchers suggest that the barriers to naturalization may be too high to reduce with nudges, since it takes between five and twelve hours to complete the paperwork, alongside a comfort with English and bureaucratic language.

The second example concerns a survey experiment around attitudes toward Syrian refugees in Jordan. Increasing refugee flows in recent years have triggered political backlash in a number of countries, prompting a growing literature about strategies for reducing hostility toward migrants.

In this context, IPL researchers designed a survey experiment to test strategies for improving Jordanians’ views of Syrian refugees.Footnote 4 The interventions were meant to promote generosity toward the refugee community by priming mechanisms grounded in the literature on what motivates charitable giving (Bekkers and Wiepking Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011). The first treatment encouraged Jordanians to think about the struggles and needs of the refugees; the second sought to give respondents a “warm glow” by emphasizing how grateful Syrians were for Jordanians’ hospitality; and the third attempted to connect Islamic values to the need to welcome Syrians. Each treatment included a short paragraph of text followed by a video of approximately 2 min. Individuals in the control group proceeded directly to several outcome questions. The treatments reflect the underlying logic of social cohesion programming implemented by governments, IOs, and NGOs in host countries, and as such they have important implications for efforts to facilitate the integration of migrants. However, they did not produce statistically significant effects across the various outcomes.

The authors considered both methodological and theoretical explanations for the null findings. While power calculations were performed, the warm glow treatment may have generated a small but meaningful effect detectable with a larger sample. In addition, the design or delivery of the treatment may have created issues, as enumerators reported that respondents often appeared bored during the 2-min videos. Theoretically, attempting to foster generosity by priming refugee needs and religious values may not have been sufficient to generate attitude change in a context where the refugee crisis is highly visible in Jordanians’ lives and baseline attitudes towards Syrian refugees also remain relatively positive (Alrababa’h et al. Reference Alrababa’h, Dillon, Williamson, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Weinstein2021). Instead, it may have been more fruitful to provide Jordanians with genuinely new information or frames for thinking about the crisis. The warm glow treatment came closest to this and was also somewhat more successful. Given contradictory evidence about what “works” in the prejudice reduction literature, reporting null findings consistently can help researchers think more critically about the contexts in which certain interventions are more or less likely to succeed.

Both examples demonstrate the value of this exercise. Instead of losing the opportunity to learn from failed nudge and prejudice reduction experiments, the null results reports put the scholarly community in a position to observe important lessons about the design and implementation of particular nudges and prejudice reduction interventions.

6 Challenges and Opportunities on the Path Forward

Several apparent challenges stand in the way of the successful adoption of null results reports as a norm in political science. First, even with an accessible template and visible examples within the discipline, time constraints and fear of reputational costs may still deter researchers. Second, even if these null results reports become more widespread, they may not prove useful to the academic community if they are not organized and accessible.

As discussed previously, research communities including labs, departments, and subfield groups can play a key role in overcoming these challenges by adopting guidelines and requiring their affiliates to report null results. However, other academic institutions can also contribute substantially to the development of a reporting norm. In particular, large funding organizations like the National Science Foundation could develop requirements for grant recipients to publicize a summary of their findings within a certain time period of receiving the funding, with waivers granted for evidence that the project is moving through the publication process. On a positive note, the SBE Division of the NSF funded a recent workshop to make recommendations on the role of federal granting agencies in promoting the publication of null results (Miguel Reference Miguel2019).

Likewise, pre-registration repositories such as those connected to EGAP and AEA can also encourage the emergence of a reporting norm (Rasmussen et al. Reference Rasmussen, Malchow-Moller and Andersen2011). As discussed previously, scholars can post updates to their registrations that could, in theory, include a null results report after the study has been implemented. However, the registries could substantially increase the likelihood of this practice becoming widespread by requiring that scholars post a summary of the findings from their preregistered studies within a certain time period, whether as a publication, working paper, or shorter null results report. As with the PAPs, these summaries could be entered through a formulaic template on the website, they could be embargoed for a set amount of time, and they could be reviewed quickly by staff to ensure that they include a basic set of information about the project. The adoption of these standards by large pre-registration repositories would also help to minimize the problem of organization. Null results reports could be posted with the initial pre-registration plan, and be searchable by keywords and visible to other researchers.

In the meantime, we encourage individual scholars to follow our model by posting reports of null findings on their own websites, in addition to posting them on preprint platforms such as SocArxiv, OSF, or SSRN using the keyword “Null Results.” This will allow the reports to be cited and would further reduce problems related to organization and accessibility. If a norm of writing null results reports can be developed from the bottom-up, we are confident that the discipline of political science will have taken a step toward improving our ability to cumulate knowledge.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding from the Swiss Network for International Studies, the Ford Foundation, the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant NCCR on the move 51NF40-182897), and the Stanford Center for International Conflict and Negotiation.

Data Availability Statement

Replication code and data for this article is available at Alrababa’h et al. (Reference Alrababa’h2021) at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PEGIUB.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2021.51.