I. Introduction

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the number of international organisations (IOs) (Drezner Reference Drezner, Goldstein and Finnemore2013: 284) and transnational institutions (Tallberg et al. Reference Tallberg, Sommerer, Squatrito and Jönsson2013), the amount of international authority (Zürn et al. Reference Zürn, Binder, Tokhi, Keller and Lockwood-Payton2015; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Lenz, Bezuijen, Ceka and Derderyan2017), and the count of international treaties and agreements (Pauwelyn et al. Reference Pauwelyn, Wessel and Wouters2014; Hathaway and Shapiro Reference Hathaway and Shapiro2017) have reached all-time highs. The rise of transnational and international norms and rules has caused two challenges for global governance. Externally, the growing relevance of international and transnational institutions has given rise to social forces that defend national sovereignty against intrusions by cosmopolitan elites holding power in these institutions. Internally, it has created an increasing institutional density in the international system (e.g. Raustiala Reference Raustiala, Dunoff and Pollack2013: 296),Footnote 1 by which both collisions between norms or rules at the international level (horizontally) and between international and national ones (vertically) become more likely. This Special Issue focuses on the internal challenge to global governance.

While approaching questions relating to institutional density and norm collisions from two different – normative vs. descriptive – angles, scholarship in both international law and international relations (IR) tends to be pessimistic about their effects (see Faude and Gehring Reference Faude, Gehring, Sandholtz and Whytock2017 for an overview). On the one hand, the focus of international lawyers has mainly been on the fragmentation of international law that arguably undermines the unity of the international legal system. It is seen as an antipode to the constitutionalisation of international law that promises legal certainty and thus allows for the development of an international rule of law (Benvenisti and Downs Reference Benvenisti and Downs2007; Dunoff and Trachtman Reference Dunoff, Trachtman, Dunoff and Trachtman2009; Klabbers et al. Reference Klabbers, Peters and Ulfstein2009). On the other hand, studies in IR have mostly revolved around the notion of regime complexity and highlighted the possibilities for states to engage in cross-institutional strategising in this context (Alter and Meunier Reference Alter and Meunier2009). The prevailing assessment is that overlapping institutions are a source of conflict (e.g. Margulis Reference Margulis2013) and that states’ increased ability to resort to forum shopping or regime shifting to further their goals undermines the law-based international order (Drezner Reference Drezner, Goldstein and Finnemore2013; Gómez-Mera Reference Gómez- Mera2016).

However, scholars of both disciplines have also pointed out that the process of constitutionalisation is inherently contested, implying that contestation across legal spheres ‘does not (necessarily) descend into conflict but can productively produce new institutions at the domestic and global level’ (Lang and Wiener Reference Lang and Wiener2017: 4; see also Tehan et al. Reference Tehan, Godden, Young and Gover2017). In our view, the consequences of the growing institutional density for global order are thus far from established (see also Peters Reference Peters2017; Meggido Reference Meggido2019). As we argue in this Special Issue, the question of how the existence of multiple, non-hierarchically ordered sites of political and judicial authority affects the constitutional qualityFootnote 2 of the global order depends on a) whether and when overlaps or norm collisions lead to actual conflicts between actors, and b) whether and how such conflicts are managed. It is the (lacking) coordination between different norms, rules, and authorities that poses a problem, not the number of norm collisions or institutional overlaps. The constitutionality of governance systems needs to be addressed by looking at the quality of conflict management between different norms and authorities, not by assessing the degree of institutional differentiation (Zürn and Faude Reference Zürn and Faude2013).

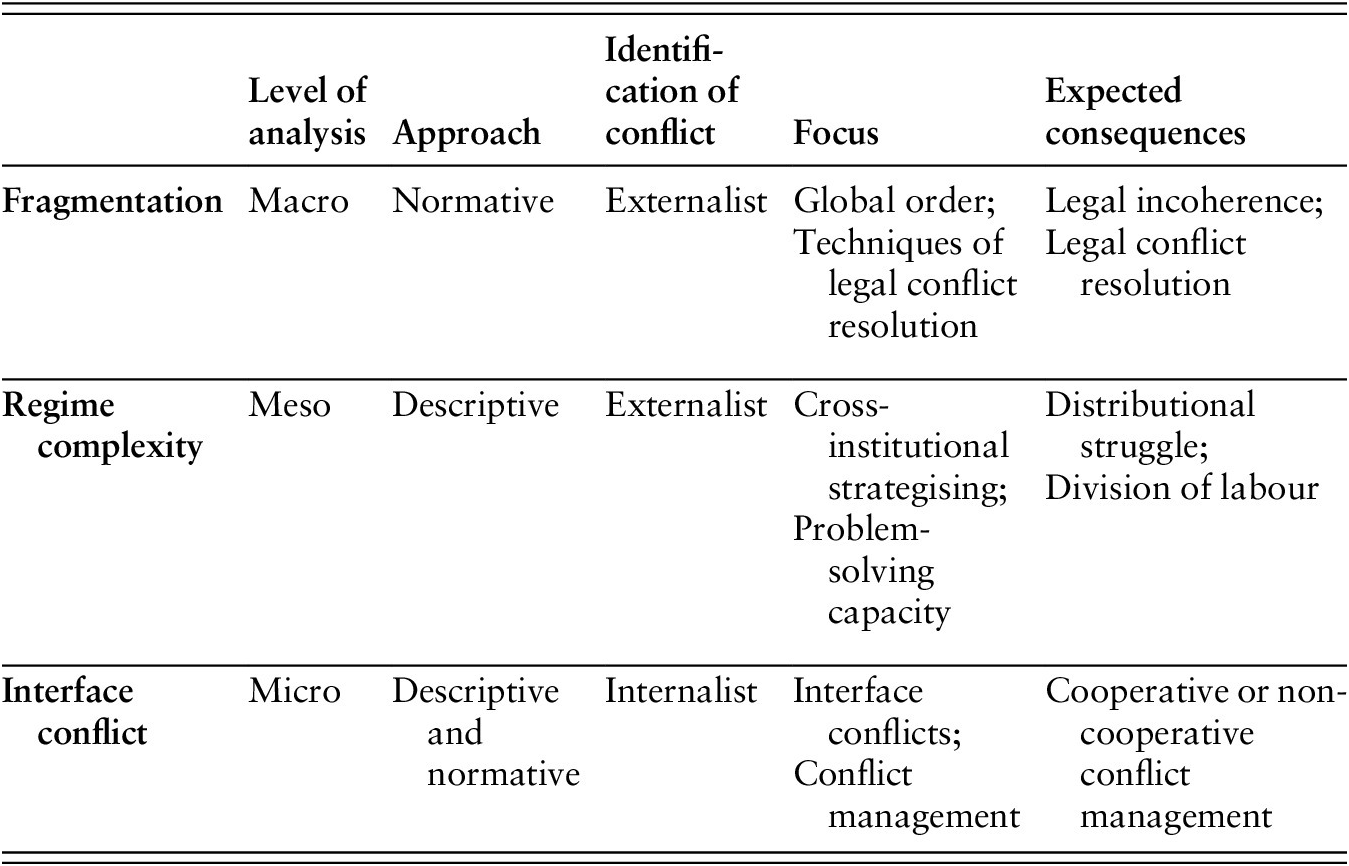

To study these questions, the Special Issue introduces an interface conflict framework as a research programme that puts the focus on the micro-level of conflicts between actors who refer to different international norms. We introduce our perspective in distinction from the fragmentation framework, which primarily works on the macro-level and is order-oriented, and the regime complexity framework, which works on the meso-level and is problem-solving oriented. With the shift to the micro-level of conflict, we, first of all, reorient the focus from norm incompatibility identified by observers to conflicts identified by actors – states, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), IOs, etc. – who justify their position with reference to different international norms. We thus differentiate between an externalist and an internalist approach. In legal as well as political science scholarship, there is a preponderance of the externalist approach by which the relationship of norms and rules is determined from the outside, that is, based on the researcher’s analysis of the compatibility of the norms and rules in question. By contrast, we seek to foreground an internalist approach that looks at the perceptions and behaviour of actors involved in the respective governance fields to trace the activation of norm collisions and analyse positional differences between actors on the relationship of norms and rules. Our core unit of analysis is what we term interface conflicts: incompatible positional differences between actors about the prevalence of different international norms or rules. We want to understand when, why, and how overlaps and norm collisions are seen, used, and abused by the actors of world politics.

Secondly, the interface conflict framework directs attention to the management of interface conflicts (see also Zelli Reference Zelli, Oberthür and Stokke2011; Peters Reference Peters2017). The type and outcome of conflict management are decisive to determine the consequences of institutional density. On the one hand, if conflict management is outright refused by the actors or if positional differences play out in the absence or disregard of procedural rules and thus lead to purely power-based outcomes, the expectation of fragmentation is vindicated; on the other, if conflict management follows procedural rules and produces secondary norms to avoid or handle interface conflicts in the future, it contributes to the creation of a coordinated inter-institutional order. Depending on the normative underpinnings of this order, its global constitutionalist aspirations can be more or less pronounced.

This micro-level perspective adopted in the contributions to this Special Issue enables some important insights and findings. Most importantly, institutional overlaps and norm-collisions do not necessarily lead to fragmentation of or chaos in the international order. This is so for two main reasons. First, not all institutional overlaps or norm collisions get transformed into interface conflicts. Many institutional overlaps and colliding norms can co-exist more or less silently without stirring conflict among actors. Their activation in interface conflicts most often is politically motivated and not an inevitable side effect of institutional density (see, in particular, Gholiagha et al., this issue). In some cases, we even see active attempts to prevent interface conflicts through pre-emptive coordination (Faude and Fuß, this issue).

The second reason points to the importance of conflict management. Even where interface conflicts are activated, they do not necessarily have destabilising effects on international law and order. Instead, some form of cooperative conflict management either mitigates negative effects or even generates new norms that at times come close to secondary norms (Birkenkötter, this issue; Krisch et al., this issue). Of the cases analysed in this Special Issue, none stands for a fully non-cooperative orientation in the management of interface conflicts. While the contributions show a broad variety of often decentralised and ad hoc forms of conflict management, the terms of settlement are regularly norm- and order-generative rather than undermining. This finding may cause some optimism from a global constitutionalist perspective. However, the contributions also highlight that the normative substance of the nascent inter-institutional order remains highly contested and is in no way predetermined to reflect liberal values (see Moe and Geis, this issue; Flonk et al., this issue). Moreover, the normative quality of conflict management varies significantly and depends to some extent on the type of conflict.

In section II of this introductory contribution, we outline the analytical perspectives of fragmentation and regime complexity, and point to some limitations and blind spots in the accounts adopting those frameworks. In section III, we present our interface conflict framework. It introduces our core unit of analysis, namely interface conflicts, as those conflicts in which actors bring to bear norms or rules against each other and spells out the implications of an internalist approach to the identification of interface conflicts. Furthermore, it describes our understanding of global governance as a system of loosely coupled spheres of authority, which allows for the distinction of interface conflicts that are rooted in one and the same or two different spheres of authority. On that basis, we describe a research programme centred on the conditions for and the shape of governance efforts to pre-empt or manage those conflicts. In each of the subsections, we discuss some of the findings by the contributors. In section IV, we then provide a road map and present the contributions to this Special Issue.

II. Existing frameworks: Fragmentation and regime complexity

International law scholars have predominantly analysed norm collisions through the lens of fragmentation that focuses on the macro-level of the international legal system, whereas political science contributions have adopted the conceptual perspective of regime complexity to look at meso-level phenomena of sectoral institutions. We briefly outline both approaches in turn and then point to some overarching problems and blind spots that an interface conflict framework operating at the micro-level is apt to address.

The fragmentation framework

The notion of fragmentation of international law refers to both the process and the result of the expansion and diversification of international law in a non-hierarchically integrated manner (Martineau Reference Martineau2016). The post-Cold War proliferation of international institutions – in particular, the rise of numerous (quasi-)judicial dispute settlement bodies responsible for determining norms of international law within their specialised subfields – led to the perception of jurisdictional overlaps and tensions between divergent interpretations of general international law (Charney Reference Charney1998). Given the absence of a central global legislator or a single global court of appeal, there is no mechanism for the hierarchical coordination of diverse international legal regimes. In the light of emergent inter-jurisdictional struggles, fears were expressed that this could undermine the coherence of the international legal system. Against this background, the International Law Commission (ILC) initiated a study group on the fragmentation of international law, headed by Martti Koskenniemi (ILC 2006).

The debate about fragmentation among international lawyers is focused on the macro-level of the international legal order as a whole. In particular, scholarly contributions aim to assess the consequences of fragmentation for the functioning and normative structure of international law and, on that basis, formulate ideas for how to encounter the phenomenon. More often than not, these ideas take the form of structural visions where fragmentation is considered as a given challenge that requires a response on the level of the international legal system. There are three different camps with three different responses: constitutionalists, constitutional pluralists, and legal pluralists.

Especially for global constitutionalists, the fragmentation of international law is inherently problematic. The potential of conflicts and incompatibilities between separate legal obligations is seen to undercut the normative integrity of the international legal system. Specifically, it risks losses of legal certainty as an element of the international rule of law by reducing ‘the predictability and reliability of law application’ (Peters Reference Peters2017: 679; see also Crawford and Nevill Reference Crawford, Nevill and Young2012). As Peters (Reference Peters2017: 680) puts it, ‘at the bottom of the fragmentation debate lies a concern for a loss of legitimacy in international law, a loss which will ultimately threaten the law’s very existence’. The global constitutionalist response to this predicament is to aspire to a hierarchically structured legal system with an institutionalised final authority imposing a set of superior substantive norms (Dunoff and Trachtman Reference Dunoff, Trachtman, Dunoff and Trachtman2009; Fassbender Reference Fassbender2009; Habermas Reference Habermas2008). The assumption is that constitutionalising international law could thus reinstate legal coherence and certainty. By contrast, constitutional pluralists highlight certain benefits of decentralised governance systems, especially their capacity for flexible adaptation, the possibility of contestation, and the introduction of checks and balances (Krisch Reference Krisch2010: 78–89; see also Kumm Reference Kumm, Dunoff and Trachtman2009). G lobal legal pluralists even go a step further and see the fragmentation of international law as inherently desirable as it creates both a source of innovation and ‘a site of discourse among multiple community affiliations’ (Berman Reference Schiff and Paul2007: 321). It then works in the form of heterarchical interactions between different function systems (Fischer-Lescano and Teubner Reference Fischer- Lescano and Teubner2004).

Another strand in the fragmentation literature is less concerned with developing normative theories to (re-)construct the global legal order. Instead, it deals with the more concrete question of how to immediately deal with overlaps and potential conflicts between international norms (Pauwelyn Reference Pauwelyn2003) or international authorities (Shany Reference Shany2003). Here, conflicts are conceived as legal inconsistencies or overlapping claims to jurisdiction that can and need to be resolved by way of legal techniques (ILC 2006). Contributions to this debate thus mostly search for the best legal solutions to collisions within and between branches of international law, such as rules of lex specialis or lex posteriori and approaches rooted in private international law (e.g. Broude and Shany Reference Broude, Shany, Broude and Shany2011; Michaels and Pauwelyn Reference Michaels, Pauwelyn, Broude and Shany2011). While the normative prescriptions are at times formulated with respect to specific legal regimes such as the ‘trade-and-…’ nexuses and thus operate on a more sectoral meso-level, the proposed solutions are still very often generally applicable formulas devised with a view to the frictionless functioning of the international legal order as a whole.

The fragmentation framework has much strength and inspired a research programme that provided multiple new insights into the evolution and normative structure of the international legal system characterised by overlapping and partially competing claims to authority. In particular, its macro-perspective on problems at the level of the global political system has highlighted the possibility of collisions between regimes that stand for fundamentally different goals such as free trade and environmental protection (see Young Reference Young2011; Blome et al. Reference Blome, Fischer-Lescano, Franzki, Markard and Oeter2016). We embrace this notion of the global governance system as consisting of different normative spheres that stand in an interdependent yet non-hierarchical relationship with each other (Zürn Reference Zürn2018).

The regime complexity framework

In parallel to the fragmentation debate in international law, the growing institutional proliferation and density at the international level also led IR scholars to go beyond their previous focus on single and separate international institutions to analyse interactions between institutions with overlapping regulatory functions.Footnote 3 In this context, Raustiala and Victor (Reference Raustiala and Victor2004) coined the term ‘regime complex’ to denote a set of non-hierarchical institutions with partially overlapping jurisdictions that govern a particular issue area or subject matter. In their initial study, for example, Raustiala and Victor analysed the regime complex for plant genetic resources, that is, the interplay of different institutions such as the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), and the United Nations (UN) Convention on Biological Diversity, speaking to the problem of property rights for plant genetic resources (ibid: 283–4).

The concept of a regime complex stresses three necessary features (Alter and Meunier Reference Alter and Meunier2009; Keohane and Victor Reference Keohane and Victor2011; Orsini et al. Reference Orsini, Jean-Frédéric and Young2013; Zelli Reference Zelli, Oberthür and Stokke2011; Alter and Raustiala Reference Alter and Raustiala2018): (1) two or more separately created elemental institutions with (2) overlapping membership (Hofmann Reference Hofmann2011), that (3) speak to the same issue area, problem, or subject matter. On this basis, scholars have increasingly analysed the governance of a given problem or subject matter by mapping the complex of international and transnational agreements, their interplay, and how the interplay affected outcomes, with a view to the problem-solving capacity of inter-state cooperation. While regime complexity may also be seen as a systemic feature of world politics, regime complexes as understood in this literature operate at a meso-level of societal organisation, not at the macro-level of the global governance system as a whole (see also Faude and Gehring Reference Faude, Gehring, Sandholtz and Whytock2017: 186).

One key question addressed in the regime complexity literature is how regime complexes are structured and how their structure impacts the problem-solving capacities regarding the respective issue. Here, most contributions have taken given issue areas or governance problems as starting points to map the web of inter- and transnational institutions that overlap in their claims to authority regarding the regulation of issues such as climate change (Keohane and Victor Reference Keohane and Victor2011; Abbott Reference Abbott2012), security (Hofmann Reference Hofmann2011), global refugees (Betts Reference Betts2009), or intellectual property rights (Helfer Reference Helfer2009). As a consequence, the literature has mostly focused on interactions between institutions rooted in one and the same issue area. Studies about the trade–environment nexus are the most notable exception in this regard (e.g. Eckersley Reference Eckersley2004; Biermann et al. Reference Biermann, Pattberg, van Asselt and Zelli2009; Zelli et al. Reference Zelli, Gupta and van Asselt2013).Footnote 4 In terms of assessment, these contributions are thus predominantly concerned with the functionality of the regime complex for solving the problem(s) around which the elemental institutions converge (see Keohane and Victor Reference Keohane and Victor2011; de Búrca et al. Reference De Búrca, Keohane and Sabel2014).

The second main question concerns the effects of regime complexity for strategic interactions. Here, the gist of the literature is that the existence of multiple and overlapping institutions in an issue area create new options for states and non-state actors to pursue their interests. On the one hand, it opens the possibility of institutional choice (Jupille et al. Reference Jupille, Mattli and Snidal2013). In an institutional setting with overlapping claims to regulatory authority, the rule-addressees may engage in forum shopping to circumvent costly obligations or foster favourable decisions on specific questions in their interest (Busch Reference Busch2007). On the other hand, it also enables actor coalitions that are dissatisfied with an existing institution to shift the focus of their ‘activity to a challenging institution with different rules and practices’ (Morse and Keohane Reference Morse and Keohane2014: 388). This practice is referred to as regime shifting (Helfer Reference Helfer2009) or more broadly as contested multilateralism (Morse and Keohane Reference Morse and Keohane2014; Kreuder-Sonnen and Zangl Reference Kreuder-Sonnen and Zangl2016) or counter-institutionalization (Zürn Reference Zürn2018: Ch 7).Footnote 5 On that basis, the literature has so far tended to stress the problems created by regime complexity for an international order based on law. Arguably, it propels a shift from law-based to power-based outcomes by providing powerful states with additional opportunities to pursue their parochial interests through inter-institutional strategising (Drezner Reference Drezner, Goldstein and Finnemore2013; see also Faude and Gehring Reference Faude, Gehring, Sandholtz and Whytock2017: 187).

To sum up, the regime complexity framework has produced a rich research programme on the meso-level of global governance arrangements in the confines of single issue areas or subject matters. Research in this tradition is predominantly centred on the question of either the effects of regime complexes on problem-solving capacities or the strategic opportunities they open for actors. Such an approach is valid and important to understand the effects of institutional interplay for problem solving and distributional effects.

Shortcomings: The need for a micro-level approach

While both frameworks outlined above have spurred a rich and insightful research programme, they also have some limitations and blind spots. Most importantly, they have largely worked on assumptions of inconsistency or complementarity between the norms that overlapping institutions embody. Much less attention has been paid to the question of what actually happens at the interface of the fragments that compose the international legal system or between the elemental institutions that compose a regime complex. Do overlaps really result in interface conflicts? If yes, when? And how, if at all, are colliding norm sets handled empirically? We suppose that the neglect of these questions is tied to a second problem of both the fragmentation and the regime complexity framework, namely their reliance on an externalist approach to the identification of normative incongruence. That is, whether an overlap exists and whether it is conflictual or not is determined by the researchers from the outside, mostly relying on legal analyses. However, it is possible that actors see or construct norm collisions where analysts do not, and it is possible that analysts see conflicting norms, but actors do not. In our perspective, institutional overlap constitutes a problem only to the extent that at least one collective social actor (interest group, civil society organisation, state, or IO) challenges the validity or interpretation of an international norm or rule by referring to the prevalence of another norm or rule. Conflicts need to become activated via contestations in practice or speech acts. Such a focus on the actors’ own perception or construction of normative incompatibility is at the core of our internalist approach to the identification of conflict.

The concentration on the handling of actors’ positional differences at the interstices of legal fragments or elemental institutions not only highlights a different element of the phenomenon, but it also represents a missing link for answering key questions in the original debates on fragmentation and regime complexity. Only if we know how conflicts are dealt with – that is, if and how they are managed – can we understand and demonstrate the mechanisms by which the deliberate or unintentional creation of institutional overlaps translates into eventually harmful or beneficial conditions for the international order and for explaining strategic interactions therein. As Michaels and Pauwelyn (Reference Michaels, Pauwelyn, Broude and Shany2011: 31) put it: ‘Whether international law behaves like a system or not is in no small part determined by the very way in which relations between rules are handled.’ Moreover, answers to these questions are necessary to determine the empirical conditions upon which the normative visions for the global legal order are to be based. Where the system of international law is headed – that is, in a more constitutionalist or a more pluralist direction – and what normative response it should give rise to depends on comparative empirical analyses at the micro-level of conflicts, of which we assemble an initial batch in this Special Issue. By doing so, we contribute to a newly emerging literature that says ‘farewell to fragmentation’ (Andenas and Bjorge Reference Andenas and Bjorge2015) as the structural concept of interest and puts emphasis on the ways in which courts, tribunals, and other actors have developed legal and political techniques to coordinate the different subfields of international law (Peters Reference Peters2017; Meggido Reference Meggido2019).

III. The interface conflict framework

In contrast to the macro-level approach of the fragmentation framework and the meso-level approach of the regime complexity framework, our interface conflict framework zooms in on the micro-level of conflict between actors. We foreground questions relating to how actors perceive or even construct norm inconsistencies, to whether and when they avoid or enter into open conflict over the prevalence of overlapping norms, and to if and how such conflicts are managed.Footnote 6 It thus provides the basis for an integrated and inter-disciplinary research programme on institutionalised cooperation after fragmentation.

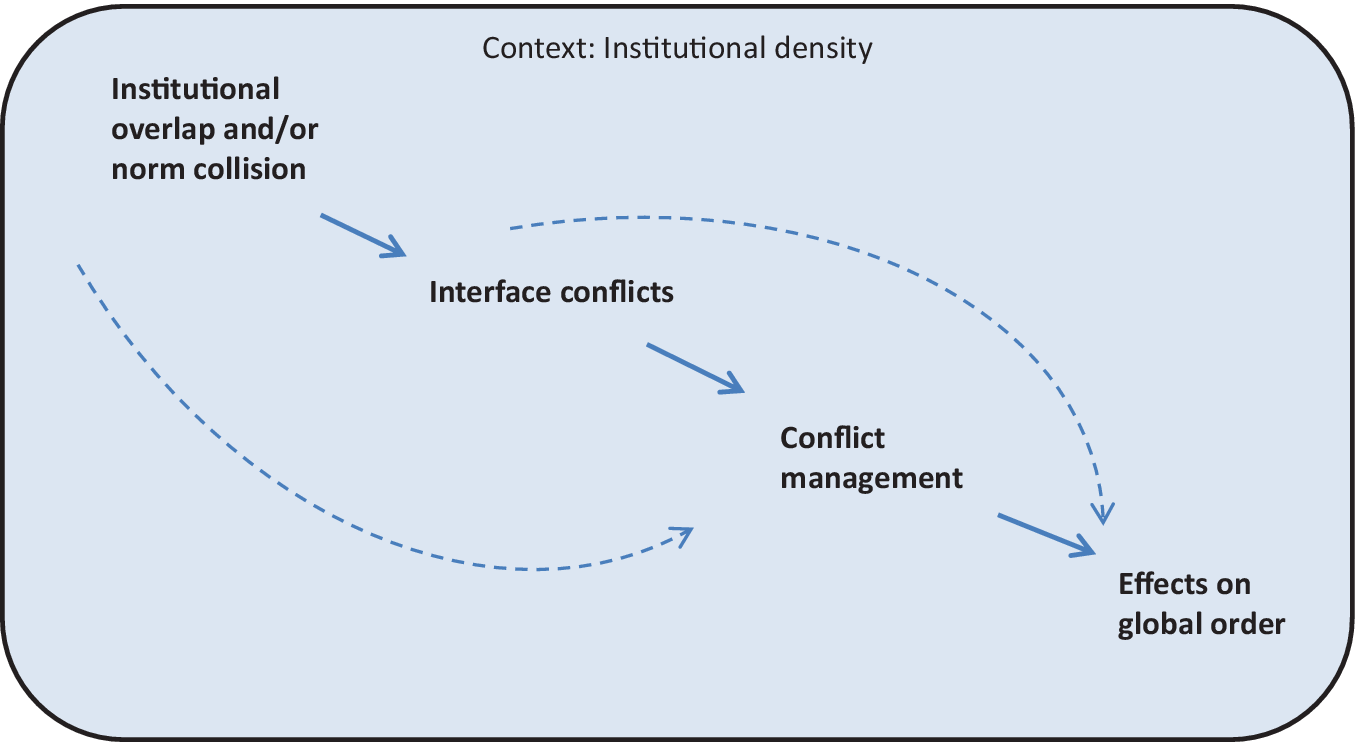

In the remainder of this introduction, we develop the analytical model underlying the interface conflict framework that the contributions to this Special Issue fill with life. Figure 1 sketches the model in a schematic fashion. It consists of a sequence of variables or concepts that we assume to be causally linked. It starts with institutional overlap and norm collisions and, through conflict activation and conflict management, leads to effects on global order. While the order of variables in the chain is logically determined, we accept that in real-world cases some steps in the causal chain can be circumvented. For instance, norm collisions or institutional overlap can incite (pre-emptive) conflict management without first creating an open interface conflict and some interface conflicts may directly affect the global order without running through conflict management. We spell out the relationship of these concepts more fully in the following sections and highlight some of the main findings in the contributions.

Figure 1: Analytical model of interface conflict framework

Core concepts

The central concept around which our framework revolves is that of interface conflicts. It denotes those norm collisions beyond the nation state that are perceived or constructed by actors and expressed in positional differences. We are interested in the causes of interface conflicts and in their consequences. Interface conflicts can thus be both an analytical starting and end point. They represent a starting point inasmuch as we are interested in how interface conflicts are acted upon – that is, if and how they are managed – and what consequences the conflict management has on the global order. On the other hand, they are also end points to the extent that we inquire into the conditions under which interface conflicts come about or can be avoided.

In order to approach these questions, it is first of all necessary to develop a clear-cut conceptualisation of interface conflicts. In general, interface conflicts refer to a subset of norm collisions arising in global governance. We include only collisions between norms emanating from different institutions, at least one of which being an international authority. This conceptual scope allows us to study both horizontal conflicts pitting norms from two international institutions against each other, and vertical conflicts in which domestic and international norms collide. But how do we know when we see an interface conflict? The literature has so far tended to adopt a formalistic approach according to which the legal community establishes conflicts by determining the correct legal interpretation of the norms in question (see Wisken Reference Wisken2018: Ch 2). By contrast, our conceptualisation takes a sociological perspective and sees interface conflicts not as objectively given. Before we speak of conflicts, they must be constructed and perceived as such by relevant actors and expressed in form of incompatible positional differences about means or goals (see Dahrendorf Reference Dahrendorf1961; Coser Reference Coser1964). Importantly, this also implies that interface conflicts may arise irrespective of whether the norms invoked by the conflicting actors previously were colliding according to legal observers. We thus give priority to the internal perspective on conflict.

In sum, then, we speak of an interface conflict when relevant actors perceive rules to diverge in such a way that the simultaneous attainment of their regulatory objectives is seen to be incompatible or unattainable, or when they purport such an incompatibility to pursue their interests. In other words, interface conflicts are defined as incompatible positional differences between actors about the prevalence of two or more norms or rules emanating from different institutions. In these interface conflicts, different positions are justified with reference to different norms and rules of which at least one is associated with an international authority.

A prominent example of an interface conflict is the dispute over the UN Security Council’s (UNSC) regime of targeted sanctions against terror suspects. Here, positional differences were expressed over the question of whether and to what extent the UNSC should be obliged to grant due process rights to the targeted individuals. One actor coalition, including the United States and the UNSC as a whole, referred to the special powers granted to the UNSC in the UN Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security to argue that no such obligation existed. Another actor coalition, comprising in particular European and domestic courts, the UN Human Rights Committee, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, several NGOs, and a group of European states, held that basic – if not the full range of – due process standards had to be adhered to by the UNSC when targeting individuals. They justified their position by reference to international, and particularly European, human rights norms (Krisch Reference Krisch2010: Ch 5; Heupel Reference Heupel2013, 2017; Kreuder-Sonnen Reference Kreuder-Sonnen2019: Ch 4).

Indeed, the case is well-rehearsed also in the fields of fragmentation (Ziegler Reference Ziegler2009) and regime complexity (Morse and Keohane Reference Morse and Keohane2014). From the perspective of our approach, however, it highlights the necessary features of interface conflicts that are a) actors with positional differences who b) justify their respective stance with reference to different international norms that are c) connected to different international authorities. This notion is more restrictive than the situations covered in the alternative accounts. For example, the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) alongside the World Bank is widely cited as building a regime complex of development banking that undermines the hitherto stable rules of development financing (Heldt and Schmidtke Reference Heldt and Schmidtke2019). However, upon closer inspection, we see that the regime complex so far has not activated interface conflicts. None of the relevant actors have brought the rules of one institution in collision with those of another institution (see Faude and Fuß, this issue). In the same vein, the competing jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia on the question of state responsibility for non-state actor violence – the famous ‘effective control’ versus ‘overall control’ standards – are treated by the ILC (2006: paragraphs 49–52) as a prime example of fragmentation through conflicting interpretations of general law. It is a completely different question, however, whether such a ‘prima facie conflict’ (ILC 2006: paragraph 21) is also activated by actors seeking to justify positional differences by referring to competing norm interpretations.

To sum up the conceptual discussion: While the interface conflict framework does not introduce a completely new type of phenomenon, it proposes a new analytical lens that centres on guiding questions, a unit of analysis, and empirical expectations that are distinct from those taking centre stage in the fragmentation and regime complexity frameworks (see Table 1). On this basis, we move on to discuss some of the implications of this framework and our findings.

Table 1. The analytical frameworks compared

From overlap and norm collisions to interface conflicts

A first set of issues arises regarding the first arrow in our model that connects institutional overlaps and norm collisions with interface conflicts (see Figure 1). We expect that interface conflicts most often are based on previously existing institutional overlaps or norm collisions that were not (yet) openly expressed in actors’ positional differences. Institutional overlap can broadly be defined as different transnational and/or international institutions with prescriptive norms and rules that speak to the same issues and have an intersecting membership. Whether and when such overlaps are turned into interface conflicts is an open question addressed by Faude and Fuß in this issue. Norm collisions, on the other hand, can be defined as an incompatibility of two norms due to colliding expectations about appropriate behaviour (see Gholiagha et al., this issue). In this understanding, actors may individually or dialogically problematise a perceived inconsistency between two norms without, however, justifying incompatible positions by reference to the colliding norms. As Gholiagha et al. show in this issue, norm collisions can long predate interface conflicts. Only when they are activated do they translate into actors’ positional differences.

Taking interface conflicts as an analytical end point, the contributions to this Special Issue produce some important findings. Most importantly, the number of norm collisions and institutional overlaps is far greater than that of interface conflicts – that is, intersecting norms and institutions do not always lead to conflict among actors. Gholiagha et al. show in their contribution that the activation of norm collisions often is a matter of political choice and it is subject to scope conditions such as the power distribution in the political system. For example, the prohibition of coca leaf chewing in the international drug control regime had long been seen as colliding with indigenous rights, especially by political actors from Bolivia. However, it took decades before the collision was transformed into an interface conflict at the international level (Gholiagha et al., this issue). Moreover, Faude and Fuß argue that institutional overlaps only lead to interface conflicts if the motivation for the creation of overlapping institutions emanates from substantive policy dissatisfaction. In other cases, inter-institutional coordination or at least the peaceful co-existence of the overlapping institutions is more likely (Faude and Fuß, this issue). The flipside of these findings is that the transition from overlap/collision to conflict appears to happen predominantly for instrumental reasons. Interface conflicts are not just an unintended side product of an increasing institutional density at the international level. Therefore, they can also hardly be prevented by institutional means. The types of interface conflicts and the ways in which they are addressed thus become all the more important objects of study.

Moreover, we hold that one important dimension to distinguish interface conflicts, which is consequential also for conflict activation and management, is their bone of contention. Here, we aim at broadening the research agenda related to international institutional density beyond the narrow focus on issue-area specific overlaps and sources of conflict to encompass also veritable goal conflicts. Such conflicts are possible when norms collide that are rooted in fundamentally different social purposes. Therefore, we distinguish between interface conflicts occurring within and across spheres of authority (Zürn Reference Zürn2017). We define a sphere of authority as a governance space with at least one domestic or international authority, which is delimited by the involved actors’ perception of a common good or goal at a given level of governance. Spheres of authority are different from both issue areas and regime complexes.

While the confines of issue areas and spheres of authority overlap, they are conceptually independent. Issue areas are marked by the perception of a connected set of problems that links actors and stakeholders (Keohane and Nye Reference Keohane and Nye1977). The problem of cross-border trade is an example. However, among the actors and stakeholders in this issue area, there can be a fundamental disagreement about what the problem entails and how it should be approached and tackled. There can be actors and institutions advancing free trade by reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade. However, there can also be actors and institutions that stand for protectionism and the reduction of cross-border flows of goods and services. They all belong to the issue area. A sphere of authority, by contrast, unites actors and institutions (at least one of which is an authority) that share a common sense of purpose. The World Trade Organization (WTO), for example, is at the centre of an international sphere of authority comprising a diverse set of actors and institutions with the goal of enabling and regulating free trade.

As such, a regime complex can indeed form the institutional core of a sphere of authority as long as one of the institutions in the complex is an authority. However, as the example of the regime complex of plant genetic resources shows, a regime complex can also comprise institutions rooted in different spheres of authority, such as the WTO (free trade) and the UN Convention of Biological Diversity (Raustiala and Victor Reference Raustiala and Victor2004). The concepts are thus different. While the WTO can be part of myriad regime complexes governing certain subject matters bordering trade, it remains part of only one sphere of authority with an identifiable social purpose, namely free trade. What is more, spheres of authority can also be identified at a lower governance level than regime complexes. A set of domestic actors and institutions clustering around an authority with a nationwide goal of, say, energy transformation also qualifies as a sphere of authority. This highlights the potential of overlaps (and conflicts) between domestic and international spheres of authority that are missed by the regime complexity framework.

The conceptual lens of spheres of authority allows us to study and compare conflicts between actors who bring to bear norms emanating from one and the same or from different spheres of authority. The distinction is important because we expect significant differences regarding both the activation and management of interface conflicts. Given the overall goal-alignment of institutions in within-sphere conflicts, positional differences should normally relate to turf battles over resource allocation and institutional prevalence (interest conflicts), or to conflicts over means, not to fundamental normative disagreement. In across-spheres conflicts, by contrast, the colliding norms reflect fundamental goal conflicts over the question of according to which social purpose a certain subject matter should be governed (conflict over values). Indeed, the contributions to this Special Issue lead to the conclusion that overlaps and norm collisions within a sphere of authority get transformed into interface conflicts less often than those involving norms and institutions from two different spheres. To the extent that we observe active conflict pre-emption, it takes place within a sphere of authority. In fact, the one case of overlap studied by Faude and Fuß (this issue) that leads to an interface conflict is the one where two competing social purposes (energy security and climate change prevention) are at play. Moreover, interface conflicts seem more likely to be managed cooperatively when they take place within a sphere of authority. It is especially courts that may develop secondary norms and rules to manage interface conflicts smoothly. Most existing courts are, however, bound to one sphere of authority. In general, the management of interface conflicts across different spheres of authority can thus be expected to be more difficult. Nevertheless, some contributions to this Special Issue show that also across-sphere conflicts can be successfully managed. Birkenkötter (this issue), for instance, highlights that general international law may serve courts as a tool to legally address conflicts cutting across spheres of authority.

Conflict management

A major implication of our approach is that we are less interested in institutional density as such. In fact, we consider institutional differentiation to be a defining feature of any modern society, be it on the national or the global level. In this sense, institutional density cannot be understood as fragmentation (the falling apart of something that was once an integrated whole), and the rise of institutional density is nothing that is by itself conducive or unconducive to problem-solving. The decisive question is whether and by what principles interface conflicts are managed once they arise. With this question, we move to the second arrow in our analytical model (see Figure 1).

Here, we are especially interested in the conditions under which interface conflicts are handled cooperatively or non-cooperatively. We suppose that conflicts regularly involve some form of conflict management (see Rittberger and Zürn Reference Rittberger, Zürn and Rittberger1990). According to Zelli (Reference Zelli, Oberthür and Stokke2011: 207), management of interface conflicts can be defined as ‘any deliberate attempt to address, mitigate, or remove any incompatibility between the [norms] in question’. These attempts are in no way predetermined to be rational, balanced, or technical. Just as the conflict itself, its management can be highly political. The concrete form of the management attempts is then an empirical question, which should be telling with regard to the functioning and the normative structure of the emerging global governance system.

For the purposes of this Special Issue, we most basically distinguish between cooperative and non-cooperative forms of conflict management. We speak of non-cooperative conflict management when the conflict parties seek to resolve the dispute in their favour without regard for the preferences of their opponent and without following procedural norms. By contrast, cooperative conflict management refers to attempts to address an interface conflict in which the conflict parties agree to follow procedural norms and/or accommodate each other’s preferences at least somewhat in their respective position. Within the category of cooperative conflict management, we furthermore differentiate three subtypes according to their degree of regulation. We consider cooperative conflict management to be constitutionalised if it takes place within institutionalised procedures providing norms of meta-governance to authoritatively solve interface conflicts. Second, norm-based conflict-management describes a handling of interface conflicts with reference to third norms – that is, norms that are different from the two norms in collision. Such norms may be substantive (e.g. higher-ranking normative principles such as sustainability) or procedural (e.g. rules of precedence or applicability). Finally, we speak of decentralised cooperative conflict management if the conflict is not referred to a third party and actors do not take recourse to third norms, but when they still show a willingness for mutual accommodation and political compromise in the process of handling positional differences. This orientation towards compromise may show in actors’ acceptance of certain basic procedural norms and/or the at least rhetorical embrace of some common norms. An orientation towards compromise is also indicated if actors adapt their behaviour – actively or tacitly – to reduce positional differences by taking other positions into account.

The studies in this Special Issue show quite impressively that fully non-cooperative forms of conflict management are rare. In fact, all contributions focusing on the management of interface conflicts find that actors respond to conflicts at least moderately cooperatively. While none of them finds indications for a constitutionalised system of conflict management, especially Birkenkötter (this issue) highlights that interface conflicts can be referred to third parties – that is, courts – that implement norm-based conflict management by solving legal disputes with reference to (mostly procedural) third norms. Others find conflict management to be much less regulated but still cooperative. For instance, Krisch et al. (this issue) show that conflicts over human rights in World Bank policies and UN rules of Corporate Social Responsibility have not been addressed through third parties or third norms. Nevertheless, the decentralised norm-based contestation between the conflict parties has led to a tacit accommodation of human rights norms in the adjacent institutions and thus significantly reduced the norm incoherence (see Krisch et al., this issue). Even in the field of internet governance where Flonk et al. (this issue) trace protracted interface conflicts between competing liberal and sovereign spheres of authority, actors’ conflict handling is characterised at least by the acceptance of basic procedural norms and an interaction mode of norm-based argumentation indicating at least some compromise orientation. Overall, we can conclude with Krisch et al. (this issue: 360) that often ‘norm collisions are not antithetical to order but creative of it’. In this sense, Dahrendorf (Reference Dahrendorf1961) may have been right to emphasise that conflicts are the ‘creative core of all societies’.

The choice of conflict management, in turn, seems to depend on the types of underlying conflicts and scope conditions. For instance, it seems to be conflicts over underlying values that are especially difficult to manage, which might also be one of the reasons why interface conflicts between different spheres of authority are less likely to be managed on the basis of third norms. In these cases, decentralised forms of conflict management prevail (e.g. Krisch et al., this issue; Flonk et al., this issue). Conflict management, however, is not fully predetermined by conflict types. Scope conditions – such as the power distribution among the involved parties and their general attitude towards each other – as well as the role that transnational actors and third parties play are decisive.

Effects on global order

Moving to the third arrow in our model – from conflict management to effect on global order (see Figure 1) – it is fair to state that the diffusion of interface conflicts leads to neither constitutionalisation nor fragmentation. Cooperative conflict management of interface conflicts prevails, but it falls short of creating a strong and legally systematic apparatus of secondary norms that cut across spheres of authority. Norm-based cooperative conflict management in which the actors resort to third norms to address the conflict is the most order-generating type of conflict management observed. Since it typically incites the creation of future-oriented interface norms, it does introduce some secondary norms into the global governance system that support the building of an inter-institutional order (e.g. Birkenkötter, this issue). However, also decentralised forms of conflict management may establish normative guideposts for mutual adaptation (Krisch et al., this issue). This is particularly true for instances of pre-emptive conflict management in which the coordination of potentially conflicting norms and institutions may lead to normative alignment or a sustainable division of labor (Faude and Fuß, this issue; see also Flonk et al., this issue). In this sense, the rise of interface conflicts does not necessarily undermine the global legal order.

At the same time, the mere absence of chaos or disorder in an institutionally dense international environment does not say much about the normative quality of the inter-institutional order emerging from the handling of potential and actual interface conflicts. From a constitutionalist perspective, in particular, we have to bear in mind that the normative substance of the global legal order can be liberal but also illiberal (see also Kreuder-Sonnen and Zangl Reference Kreuder-Sonnen and Zangl2015). It is possible to think of an international order that contains strong interface norms for norm collisions but is not liberal at all. An interface norm that systematically puts state rights over individual rights may resolve many interface conflicts, but it certainly makes the international order less liberal. A prime example for this kind of illiberal order building is provided by Moe and Geis (this issue). In the realm of African security governance, interface conflicts over the prevalence of sovereignty and humanitarian intervention between the UNSC and the African Union (AU) have given way to a mutually accepted division of labour. After the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001, the paradigm of liberal interventionism was incrementally replaced by the notion of stabilisation missions, which tend to subjugate the goal of protection of individuals to that of protection of political order. While this shift allowed the UN and the AU to more cleanly divide tasks of mandating and enforcement on the ground and thus to increase inter-institutional order, Moe and Geis (this issue) show that this order is highly detrimental to human rights protection on the ground.

While there is no theoretical reason to expect the settlement of interface conflicts to systematically show illiberal traits, the example highlights that the normative direction of the international legal order is indeterminate. What is more, the contributions to this Special Issue show that most interface conflicts arise out of actors’ desire to contest a given institutional or normative status quo – they are not normally accidental or inevitable. Since much of the global order has at least a veneer of liberalism rooted in post-war Western dominance (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2011), it is not far-fetched to claim that interface conflicts often serve as instruments to contest (overly) liberal aspects of the order and/or to undermine the preponderance of established (Western) powers in international institutions. Most prominently, this dynamic can be observed in the interface conflicts unfolding in the domain of internet governance (see Flonk et al., this issue). While actor coalitions and interest constellations are more complex, the article shows that the proponents of a sphere of sovereign internet are led by rising powers contesting the preponderant sphere of liberal internet, which is centred on Western institutions and human rights norms (Flonk et al., this issue). Evidently, norm contestation through interface conflicts can also be progressively geared towards an enhancement of liberal values (e.g. Krisch et al., this issue). Yet, given the current distribution of power in international institutions and their value orientations, we expect that, more often than not, norm collisions will be activated to contain and not to reinforce the liberal aspect of global order.

The effects of international institutional density and the rise of interface conflicts on the constitutional quality of the global order thus are important but indeterminate. We expect that real-world interface conflicts lead to conflict management that entails complex and contradictory configurations of consequences for the normativity of global order. After fragmentation thus does not mean before constitutionalisation. It stands for a global political system that consists of spheres of authority that are loosely coupled in varying ways with different implications for the normative quality of global order.

IV. Contributions

The contributions to this Special Issue tackle three major questions that lie at the core of the interface conflict framework: a) under what conditions interface conflicts arise, b) if and how interface conflicts are managed, and c) what effects interface conflicts and their variable handling have on the global order. Faude and Fuß as well as Gholiagha et al. provide answers to the first question. The contribution by Faude and Fuß inquires into the conditions under which deliberately created institutional overlaps result in interface conflicts. Studying institutional overlaps in the fields of development banking, climate change, and energy, Faude and Fuß show first of all that not all overlaps translate into interface conflicts. Second, they argue that whether this happens very much depends on the motivation for creating overlapping institutions in the first place. If dissatisfaction with procedural rules or the governance effectiveness of the institutional set-up is the reason for bringing in overlapping institutions, Faude and Fuß expect coordination among the institutions. Only if the overlap is created due to dissatisfaction with substantive policies, they argue, is it likely to spur veritable conflict.

Similarly, Gholiagha et al. start from the assumption that there are norm collisions – that is, subjectively or intersubjectively perceived normative incompatibilities – which are not yet nor will necessarily become actual interface conflicts. In their view, norm collisions need to be activated by actors who employ the colliding norms to justify incompatible political positions and to induce a policy change. Analysing the discourse in the issue area of international drug control, Gholiagha et al. show that a norm collision between indigenous rights and the prohibition of coca leaf chewing existed for decades before it was activated by Bolivia, the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and the International Narcotics Control Board in the late 2000s. Zooming in on the question of the conditions under which norm collisions are turned into interface conflicts, Gholiagha et al. extrapolate three main factors that were conducive to the activation of the norm collision regarding coca leaf chewing and that are expected to be more general scope conditions for the translation of norm collisions into interface conflicts: the decline of hegemony, the mobilisation by advocacy coalitions, and a (health) crisis.

Birkenkötter starts to move from the analysis of the emergence of interface conflicts to the analysis of conflict management. Concretely, her contribution studies the role of international law as a conflict management tool in interface conflicts that end up in front of a court or court-like third party. As Birkenkötter argues, international law provides a common language that cuts across spheres of authority and provides commonalities of legal form that regulate conflict management in recurrent ways. On the one hand, when conflict management involves international courts or court-like institutions, the conflict parties are tied to specifically legal arguments. That is, when referring to norms, they must make an effort to argue why that norm should be legally binding and not merely be morally persuasive. On the other hand, judicial or quasi-judicial third parties may then resort to legal norm-conflict resolution rules such as lex specialis or lex posterior, or also broader rules of justification and excuses such as the principle of proportionality. Overall, Birkenkötter makes the claim that international law can function as a legal conflict resolution tool, but that it is strongly limited in scope and furthermore unlikely to appease the underlying political conflict.

In their contribution, Krisch et al. look at more decentralised management of interface conflicts, that is, without third party involvement. While the literature tends to highlight the conflict potential of mostly rivalrous norm collisions that are not subject to more regulated conflict management, Krisch et al. argue that interface conflicts are often rather of irritative nature and thus not destabilising but transformative of order – an effect that becomes visible when the conflicts and their management are observed over longer periods of time and not as momentary snapshots. According to Krisch et al., conflicts are irritative if they imply a normative challenge to the existing institutional or normative status quo that is not meant to replace the original norms and institutions or to play one of them out against the others, but to induce normative change in the existing body of norms. Since irritation may be met with gradual adjustments, it is more conducive to cooperative conflict management than rivalry. This claim is illustrated in two case studies of the handling of interface conflicts related to the relationship between human rights norms and World Bank policies and procedures as well as UN norms of Corporate Social Responsibility.

In the field of internet governance, Flonk et al. analyse a sequence of interface conflicts in varying institutional settings and partially varying actor compositions, but with a broadly consistent object of contention: the question of whether the internet should be governed by mostly Western, multi-stakeholder institutions embodying liberal norms of individual freedom or by mostly non-Western, intergovernmental institutions embodying sovereigntist norms of national security and territorial integrity. Flonk et al. frame this as a goal conflict across two emerging yet competing spheres of authority, one liberal and one sovereigntist. Reflecting the deep-seated conflict over values that is underpinning this struggle, conflict management has so far remained rather sketchy and has not yet led to a sustainable settlement among the conflict parties. Nonetheless, the contribution by Flonk et al. also shows that, even in such a rivalrous setting, interface conflicts are not necessarily addressed by means of fully uncooperative conflict management.

Finally, Moe and Geis provide a critical reflection on the consequences of conflict settlements for the global order. Focusing on the field of security governance in Africa, the contribution traces the development of the inter-organisational relations between the UNSC and the AU over questions of the interventionary use of force. Moe and Geis find that interface conflicts pitching norms of human rights protection against sovereignty and non-interference were common during the heydays of liberal interventionism in the 1990s. After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, however, Moe and Geis argue that the macro-securitisation through the global war on terrorism has led to a shift in priorities that put stabilisation missions higher up on the agenda than humanitarian interventions. As a consequence, the main normative bone of contention between the UN and the AU has waned, because stability-driven interventionism allowed for a pragmatic division of labour. While the UN retained the mandating authority, it increasingly delegated the often more robust enforcement measures to the regional organisation. While this cooperative outcome is indicative of the building of inter-institutional order, Moe and Geis highlight that it comes at a cost to liberal values, since human rights have been relegated to second rank in the preoccupation to secure political stability.

The Special Issue is concluded by two critical commentaries by Karen Alter and Siddharth Mallavarapu.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2018 General Convention of the German Political Science Association in Frankfurt, the 2019 Annual Convention of the International Studies Association in Toronto, and two authors’ workshops with the contributors to this Special Issue. We would like to thank the participants in these forums for their valuable comments, in particular Kenneth Abbott and Andreas von Staden. We are furthermore grateful to two anonymous referees for their constructive feedback, to Barcin Uluisik for language editing, and to Joia Buning for research assistance.