“I don’t want to read all this stuff, so would appreciate if someone could answer this question for me: for those who argue too few women are cited, what is the normative standard for the amount women should be cited? Is there some proportion they say is right, or is the standard more nuanced than that?”

Response to “Gender Bias in Citations” thread on poliscijobrumors.com (Natille [anonymous] 2018)

Recent political science studies identified gendered citation gaps in journal articles (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013; Mitchell, Lange, and Brus Reference Mitchell, Lange and Brus2013), with male scholars being less likely than their female peers to cite work by female scholars. These findings may explain the underrepresentation of female authors in syllabi (Colgan Reference Colgan2017; Hardt et al. Reference Hardt, Kim, Meister and Smith2017), edited volumes (Mathews and Andersen Reference Mathews and Andersen2001), and textbooks (Cassesse, Bos, and Duncan Reference Cassese, Bos and Duncan2012). Although many in the discipline are becoming more aware of implicit biases and adopting strategies to remedy them, many political scientists—including the anonymous author of the quote that opens this article, responding to an online discussion about evidence of gendered biases in citations (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018)—want to know how many citations to work by women is “enough.” This is particularly important if journals begin adopting policies to promote gender balance in citations (International Studies Review 2018), and we recognize that some research areas within political science are more gender balanced than others. For example, if an article on international security has 40% of its citations to female authors, is the author sufficiently recognizing research contributions by women? Whereas 40% of citations to women might be reasonable in international security, 40% to women in an article on gender and politics would be biased, given much greater women’s representation in that area. Without information about women’s representation in a specific research area, it is difficult to know whether the distribution of cited authors is biased, even when calculating the gender and racial breakdown of references (Sumner Reference Sumner2018).

Our study provides political scientists with estimates of women’s representation across a wide range of research fields using the gender distribution in professional association membership and authors in 38 political science journals. Though other studies discussed gender across American Political Science Association (APSA) organized sections (Reid and Curry Reference Reid and Curry2019) and authors in a much smaller subset of journals (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), we also compare the gender distribution of authors to those of journal sponsor organizations, illustrating the size of the gendered publication gap across numerous research fields within political science. In only one of 26 journals for which we also have membership data from the sponsoring section or organization did the journal publish significantly more female authors than its membership. In all other cases, women were equally represented or underrepresented among journal authors, which suggests that membership may be a more useful baseline for publication and citation rates of work by female scholars. We argue that scholars should consider gender representation in their research areas if they want to minimize implicit biases in their citation practices.

Our study provides political scientists with estimates of women’s representation across a wide range of research fields using the gender distribution in professional association membership and authors in 38 political science journals.

BACKGROUND LITERATURE

Professional associations and the National Science Foundation (NSF) collect demographic information (including gender) about awarded degrees and scholars in political science. Mitchell and Hesli (Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013) used NSF data to show declining percentages of women in the discipline as ranks increase, noting that women constitute 40% of doctoral degrees in the field but only 28% of APSA members in 2009; a decade later, it was still only 33.6% of members (APSA 2018). These data accord with other estimates of women’s participation in professional associations (Breuning and Sanders Reference Breuning and Sanders2007). Similarly, Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) noted that women comprise 27% of faculty in the 20 largest PhD-granting departments, 31% of APSA members, and 40% of PhDs in political science. Hancock, Baum, and Breuning (2013, 6) reported that among International Studies Association (ISA) members, 20% of women are full professors compared with 34% of men. These types of aggregate disciplinary snapshots identify the population of female scholars in our profession; however, they do not identify nuanced differences across disciplinary subfields or narrow substantive areas of interest, which often have significant variations in gender distributions.

A second approach for determining how many female scholars work in a research area involves coding the gender of journal article or book authors in a discipline (Evans and Moulder Reference Evans and Moulder2011; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Bates, Jenkins, Luke and Rogers2015). Breuning and Sanders (Reference Breuning and Sanders2007) found that women were only 21% of article authors in eight political science journals (1999–2004), even though their representation in APSA and ISA then exceeded 30%. Østby et al. (Reference Østby, Strand, Nordås and Gleditsch2013) found that women authored or coauthored 23% of 947 articles in the Journal of Peace Research between 1983 and 2008. Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) noted that approximately 35% of articles were authored or coauthored by women in 10 political science journals from 2000 to 2015 (N>8,000 articles). Like aggregate membership data, these snapshots of eight to 10 political science journals usually are weighted toward general journals that publish research from all subfields of political science rather than narrower research topics that may significantly deviate from aggregate, discipline-wide distributions.

Comparisons of organizational membership and published authors also reveal potential gendered publication gaps if women’s representation as article authors is significantly less than their presence in a field. Breuning and Sanders (Reference Breuning and Sanders2007) found that women are much less represented in ISA journals than in ISA sections, and Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) showed that most political science journals fail to publish a percentage of female authors similar to their APSA representation (31%). Several processes could produce publication gaps, including (1) the leaky pipeline, or fewer women in senior ranks; (2) lower article submission rates of women compared to men (Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Smith and Sokhey2019; Hesli and Lee Reference Hesli and Lee2011); (3) the rise of coauthorship, which benefits primarily male authors (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017); and (4) gender biases in editorial decision making processes. A recent special section in PS: Political Science & Politics suggested that there are no significant gender biases in editors’ decisions for five journals (Brown and Samuels Reference Brown and Samuels2018), but the persistent gendered publication gap points to more pernicious sources, such as leaky pipelines and gendered coauthorship or submission rates. For example, Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey (2019, figs. 2–3) found that, overall, men have authored more peer-reviewed articles than women (Hesli and Lee Reference Hesli and Lee2011), but this difference is driven by significant differences between men and women at the associate professor rank. Nonetheless, existing studies fail to provide insight into variations in publication gaps across topical research areas, which also are indicative of potential biases in pipelines, coauthorship, and submission rates.

HOW MANY CITATIONS TO WOMEN IS “ENOUGH”?

The previous discussion suggests that we can think about gender balance in our bibliographies, textbooks, syllabi, and speaker invitations by examining the representation of women in professional organizations and their sections. The citation literature shows, however, that there are implicit biases in citation decision making. Men’s research can be viewed as more central or important in a field (i.e., the “Matthew” effect), whereas women’s work can be ignored or worse—attributed to men in a field (i.e., the “Matilda” effect) (Rossiter Reference Rossiter1993). Even in fields such as women in politics, in which female scholars comprise a majority of all authors, male authors in Politics & Gender are still 14% less likely than female authors to cite the work of women (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018). Although recruitment and retention of more women can reduce citation gaps, we must raise awareness of implicit biases in citation decisions. Expressed differently, gendered publication or citation gaps between membership and authorship in related academic journals provide insight into research areas where potential biases in pipelines, coauthorship, and submission rates remain substantial. In this regard, our data provide more nuanced information about relevant gendered baselines for scholars who wonder whether they are missing research by women in their articles, books, and syllabi, as well as those who want to identify research areas in which gendered biases in publications and citations may be most significant.

Gender Distribution of Faculty by Field and Organized Sections in APSA

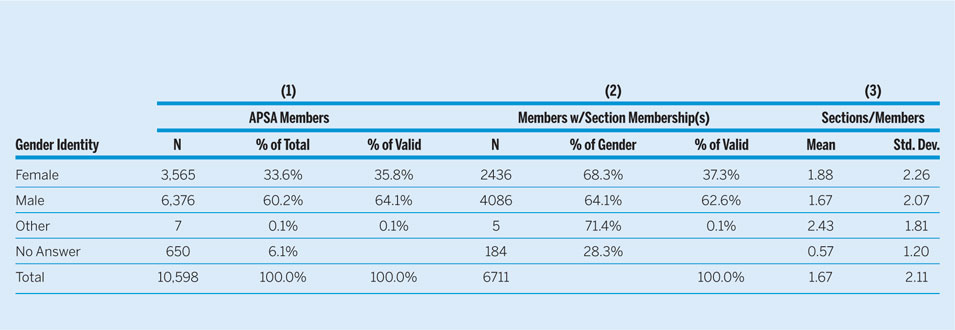

We used APSA field and section membership to establish minimum baselines for the proportion of references that should include female authors, similar to Reid and Curry’s (Reference Reid and Curry2019) use of membership data to estimate progress toward descriptive representation across political science research areas. If publications are an outcome potentially influenced by gendered practices, professional association memberships may be less biased baselines because membership involves fewer resources and gatekeepers. Nevertheless, membership figures can be gender biased to the extent that women are more concentrated in non-R1 institutions with lower levels of research support or are less likely to have research funding.Footnote 1 In 2018, of APSA members with self-reported genders, 35.8% identified as female, 64.1% as male, and 0.1% as other genders (table 1). If research productivity and publication processes are gender neutral, then journals that publish work in all research areas (e.g., American Political Science Review and Perspectives on Politics) should have one-third female article authors and bibliography entries. Of course, if women submit to journals at lower rates than men (Djupe, Smith, and Sokhey Reference Djupe, Smith and Sokhey2019) and if men cite research by other men at higher rates (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018), then these selection effects may result in gendered publication and citation gaps.

Table 1 Mean Number of Section Memberships by Gender (2018)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on APSA (2018).

Membership in more specialized organizations, such as APSA’s organized sections and affiliated groups (e.g., Society for Political Methodology), represents a wide range of research areas and the smallest relevant research communities for our analysis. Indeed, female APSA members join organized sections at a significantly higher rate than male APSA members: 68.3% of women and 64.1% of men belong to at least one section (table 1, column 2: χ2=18.277, p=0.000). Female APSA members also belong to a significantly higher average number of sections than men (table 1, column 3: ANOVA, F=21.73, p=0.000). This is consistent with women in political science being more oriented toward community building (Mitchell and Hesli Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013) as well as having less specialized research trajectories and more interdisciplinary research (Leahey Reference Leahey2006; Reference Leahey2007).

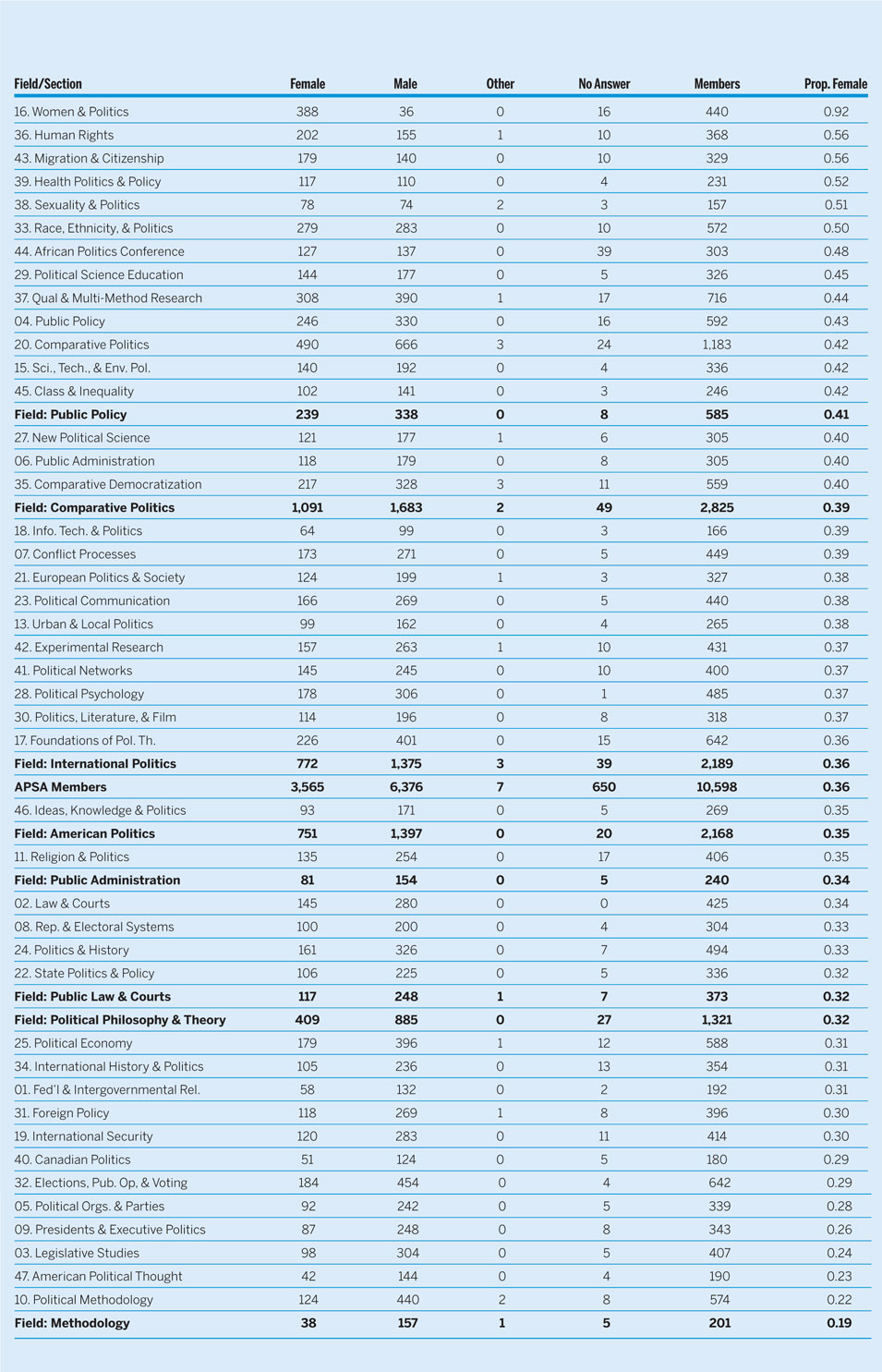

Table 2 presents the proportion of APSA members who self-identify as female by (1) self-identified primary field of study, (2) membership in organized sections, and (3) in APSA overall. We exclude those with no gender identity provided but include those who identified as other genders. In 2018, significantly more women identified their primary research or teaching field as public policy (41.4%) or comparative politics (39.3%) than the overall female representation in APSA (35.8%).Footnote 2 In contrast, women are significantly underrepresented among members who claim political philosophy and theory (31.6% female) or political methodology (19.4% female). Other large fields—including international politics, American politics, public administration, and public law and courts—have female representation rates similar to (i.e., not significantly lower than) overall APSA levels.

Table 2 Proportion of Female Members of APSA by Section and Primary Field (2018)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on APSA (2018). Proportions of members with declared gender (excluding “no answers”) are sorted in descending order by proportion female.

Organized section membership provides an even more detailed breakdown than primary field of research areas because they organize research panels at annual meetings, sponsor specialized research conferences and journals, and recognize research contributions with professional awards. The data are broadly consistent with prior research, which has noted, for example, that women are more likely to study human rights (Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013) and less likely to study methodology (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018; Shames and Wise Reference Shames and Wise2017). Several research areas have female membership that significantly exceeds overall representation in APSA, and in these areas (e.g., race, ethnicity, and politics), a representative bibliography would cite more than 35.8% of works written by women. In a few areas (e.g., legislative studies), women are significantly less represented than in APSA overall, and a representative bibliography might have fewer works by women than female membership in APSA. When political scientists compose course syllabi, graduate reading lists, and research bibliographies, these membership data provide guidance about the minimum representation of scholarship by women that should be included to be representative by gender.

In at least 13 journals, female authors were significantly underrepresented compared to their membership in the sponsoring organization, and in no instances were women “over”-represented among authors, which suggests underlying gendered practices.

Gender Distribution of Authors by Journal

Using a methodology similar to previous studies (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018; Sumner Reference Sumner2018; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), we coded the gender of the first five authors for a large sample of 38 political science journals, including all articles published between 2007 and 2016 by journals sponsored by APSA organized sections and regional and international political science associations.Footnote 3 Figure 1 plots the female proportion of authors (with 95% confidence intervals) in this sample alongside the female proportion of the journal’s sponsoring APSA section or organization membership in 2017 or 2018, when available.Footnote 4 The proportion of all authors who are likely to be female varied from a high of 0.829 female authors in Politics & Gender to a low of 0.141 in Political Analysis. Similar to the findings of Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017), who found that women were underrepresented in high impact journals compared to the profession, this figure illustrates the gap between recent membership and authorship across a much larger number of research areas. In at least 13 journals, female authors were significantly underrepresented compared to their membership in the sponsoring organization, and in no instances were women “over”-represented among authors, which suggests underlying gendered practices. Indeed, these gendered publication gaps often were greatest in the highest status journals that publish all subfields and research areas of political science (e.g., American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Politics). These data do not determine why women are less represented as authors than as organization members across such a wide range of general and narrow research areas. As explained previously, women might be less likely to submit their work or more likely to exit the discipline or experience bias during the publication process. Therefore, as a measure of the supply of female authors available to be cited, the proportion of authors who are female is a conservative estimate.

Figure 1 Proportion of Female Authors of Journals and the Membership of Sponsoring Section or Association, with 95% Confidence Intervals

Notes: APSA and organized section membership as of 2018 (APSA 2018), other organization membership as of 2017 (see fn. 4), and journal authors for 2007–2016 for available years. APSA membership used for APSA flagship journals: American Political Science Review and Perspectives on Politics. Point estimates with 95% confidence intervals. See the appendix for a complete list of journal publication years included in the sample.

Previous research also considered article author team composition (Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), recognizing homophily effects in collaborations and that collaboration is more common in some research areas. Therefore, we also coded the first five authors of each article published in our sample as solo female, solo male, female team, male team, or mixed gender team (see the appendix).Footnote 5 Only in Politics & Gender and Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics do the percentage of solo female-authored articles exceed that of solo male-authored articles and the percentage of female team-authored articles exceed that of male team-authored articles. Both areas have high rates of female participation in the journal’s sponsoring organization. If we consider journals in which the modal author team is collaborative (not solo), the modal collaborative team is either all male or mixed gender—never all female. Four journals (i.e., Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics; Journal of Experimental Political Science; Public Opinion Quarterly; and Political Communication) have more mixed gender teams than other types of author configurations. Five journals (i.e., American Journal of Political Science, Political Analysis, Journal of Conflict Resolution, British Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Politics) have mostly male only, collaborative author teams. This reflects tendencies for women to engage in fewer collaborative publications and to work in fields (e.g., comparative politics) in which collaboration is less common.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Recent studies document gender gaps in citations in political science. However, we lack benchmarks for how many female-authored works are enough for a representative bibliography across a wide range of research areas. We remedy this gap by explicitly providing conservative estimates of gender diversity based on organization membership and journal article authorship for evaluating gender representation. Instructors, researchers, and editors who want to ensure that references are representative can reference these as floors (rather than ceilings) for minimally representative citations. However, our study does not evaluate scholars’ decisions to join professional association sections or examine whether variance in gender representation among sections reflects personal preferences, perceived section biases, or both. Our dataset simply provides a benchmark and recognizes that these unobserved factors influence scholarly engagement with APSA and other associations.

Political scientists should reflect on their own citation practices to ensure that their references are consistent with gendered distribution of research in their area. Likewise, journal editors can ask peer reviewers to explicitly consider whether article bibliographies are representative, including the distribution of author genders. Some journals have gone farther, explicitly evaluating the gender balance of article bibliographies and encouraging authors to remedy gendered citation gaps by providing additional space to do so ( International Studies Review 2018). APSA sections that sponsor journals should evaluate whether the publications provide ample descriptive representation of section members. In addition, those that select journal editorial teams should pay attention not only to their diversity but also to their plans for addressing potential citation biases. Fortunately, tools, including the Gender Balance Assessment Tool (Sumner Reference Sumner2018), can help political scientists quickly and easily evaluate gender balance in their bibliographies.

Over time, as the discipline becomes more gender balanced across research areas, these estimates will need to be updated and adjusted. Finally, although we focus on gender diversity (and particularly cis-gender identities), future research and recommendations should consider racial or ethnic diversity, representation of other equity-seeking groups, as well as intersectional identities, to ensure that scholarly work by underrepresented groups is referenced adequately in political science teaching and research.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519001173

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Yanna Krupnikov for comments on an earlier version of this article.