INTRODUCTION

Discourse markers (DMs), as amply documented, occupy a top-most position on the hierarchy of items borrowed from one language to another in contact situations (Matras Reference Matras2009:193). While there appear to be recurring interactional and cognitive motivations that lie behind the high borrowability of DMs (e.g. Brody Reference Brody1987; Maschler Reference Maschler1988, Reference Maschler1994, Reference Maschler2000a,Reference Maschlerb; Salmons Reference Salmons1990; De Rooij Reference De Rooij1996; Matras Reference Matras1998, Reference Matras2000, Reference Matras2009; Goss & Salmons Reference Goss and Salmons2000; Auer & Maschler Reference Auer and Maschler2016), it is the particular linguistic, social, and ideological contact setting that affects the distinct history of each borrowed item. ‘History’ here covers not only the time in which a certain item began its circulation in a new context of speech, but the entire ‘life’ of the item within this new context, which may stray from the initial terms of its incorporation (Wilkerson & Salmons Reference Wilkerson, Salmons and Hickey2019).

The present study is concerned with one such item—ya′ani/ya′anu—in Modern Hebrew casual discourse. This item migrated into Modern Hebrew from colloquial Arabic, where it takes the form yaʕni, meaning literally ‘it means’. Our analysis of ya′ani/ya′anu is based on all tokens found in the Haifa corpus of spoken Hebrew (Maschler, Polak-Yitzhaki, Fishman, Miller Shapiro, Goretsky, Aghion, & Fofliger Reference Maschler, Polak-Yitzhaki, Fishman, Shapiro, Goretsky, Aghion and Fofliger2019) consisting at the time of this study of 243 conversations among university students, their friends and relatives, audio-recorded during the years 1993–2014. The corpus comprises over eleven hours of talk among 701 speakers, two to five participants per interaction. This corpus manifests a total of thirty-eight tokens, equally distributed between ya′ani and ya′anu (19:19).

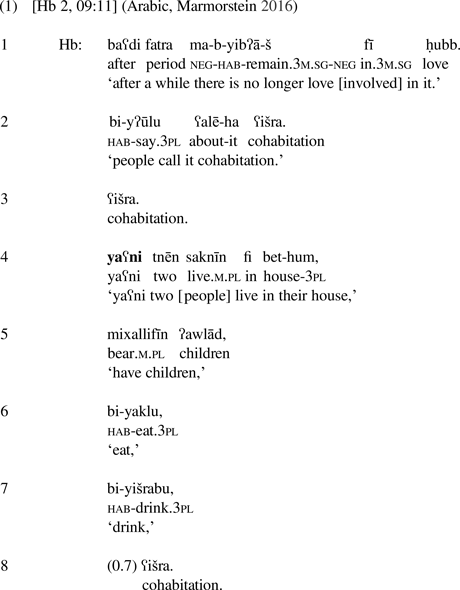

The first Hebrew variant of ya′ani/ya′anu investigated here (Pattern A) replicates the Arabic original as a DM serving to frame reformulations. For instance, in (1) and (2), both Arabic yaʕni and Hebrew ya′anu preframe a specification of the more generally formulated previous utterance. In (1), an example from Arabic, Hb is talking about married couples living with each other no longer out of love.

At lines 4–8, following a token of yaʕni, the speaker reformulates what she means by the term ʕišra ‘cohabitation’ (lines 2–3) by specifying it—two people living in the same house, having children, eating, and drinking (lines 4–8). She closes this specification by repeating the term (line 8). In (2), a Hebrew example,Footnote 1 Adva describes the location of a person with a peculiar sign who is standing next to a signpost close to a bar named hadov ‘The Bear’.

Adva begins to describe the location of where the person is standing: ′az hu ′omed ′im ha-gav, la-′amud shel ha-shelet ‘so he's standing with his back, to the signpost’ (lines 182–83). She then interrupts this description with a token of ya′anu followed by a reformulation (most likely involving gesture as well) specifying the exact whereabouts of the bar, the person, and the peculiar sign in relation to each other (lines 185–90). Thus we see that both the Arabic and the Hebrew items in question preframe reformulations specifying prior discourse.

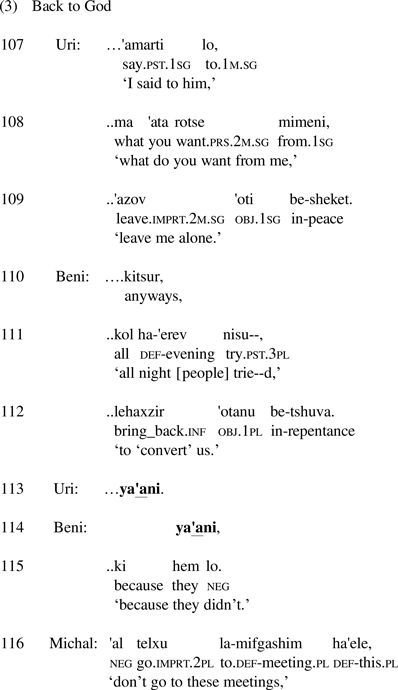

The second variant of ya′ani/ya′anu (Pattern B) is an innovation of Hebrew and consists of a modification marker. For instance, in the following excerpt (to be discussed in more detail below), Uri and Beni are co-telling a story about a Rabbi who had tried to convert them to Ultra-Orthodox Judaism.

Beni concludes the story by saying kitsur, kol ha-′erev nisu--, lehaxzir ′otanu be-tshuva. ‘anyways, all night they tried to ‘convert’ us.’ (lines 110–12). Uri's following turn consists of the word ya′ani (line 113), which refers back to Beni's immediately prior utterance and modifies it as being loosely related to its literal sense: ‘as if to attempt to convert us’. This interpretation is supported by Beni's following repetition of ya′ani in confirmation of his interlocutor's modification, followed by the explanation ki hem lo ‘because they didn't [attempt to convert us]’ (lines 114–15).

Pattern A and B ya′ani/ya′anu are prosodically distinct. In the first, the stress is carried by the first syllable, so that ya′ani/ya′anu presents the same prosodic form as Arabic yaʕni. In the second, the stress lies on the second syllable, often inducing its prolongation, viz. ya′ani/ya′anu.

We argue that this diversification of ya′ani/ya′anu in Hebrew elucidates two different processes that DMs may undergo when migrating to a different language: (i) the metalingual function of the DM is retained, even if its underlying literal meaning is lost; (ii) the metalingual function is extended due to the marker's independence of its lexical source as well as to its interaction with a different ecology of DMs.

In this article we limit ourselves to Pattern A and Pattern B ya′ani/ya′anu tokens that are involved in stance-taking.Footnote 2 We understand this term as denoting a complex act involving not only subjective evaluations, but also the ever-present intersubjective dimension, in which participants align themselves in relation to the micro- and macro-social context (cf. Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007; Englebretson Reference Englebretson and Englebretson2007; Du Bois & Kärkkäinen Reference Du Bois and Kärkkäinen2012). Pattern A is a stance-reformulation construction marked by the DM ya′ani/ya′anu. Pattern B is a ‘stance-saturated’ (Jaffe Reference Jaffe and Jaffe2009) device consisting of the modifying ya′ani/ya′anu.

In this study, in order to qualify as a DM, the utterance in question must fulfill a semantic requirement of having a metalingual interpretation in the context in which it occurs. In other words, rather than referring to the extralingual world, it must refer to the realm of the text, to the interaction among its participants (including relations of speaker to his/her utterance), or to their cognitive processes (Maschler Reference Maschler2009:17, see also Maschler & Schiffrin Reference Maschler, Schiffrin, Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015:194–98). In order to qualify as a prototypical DM, in the approach taken here, the utterance must fulfill a structural requirement as well:

the utterance must occur at intonation-unit initial position, either at a point of speaker change, or, in same-speaker talk, immediately following any intonation contour other than continuing intonation. It may occur after continuing intonation or at non-intonation-unit initial position only if it follows another marker in a cluster. (Maschler Reference Maschler2009:17)

This definition was arrived at based on a study of all 613 DMs that occurred in sixteen conversations from the Haifa corpus of spoken Hebrew. Maschler (Reference Maschler2002a) found that 574 out of the 613 DMs (94%) constitute prototypical DMs.

Maschler & Estlein (Reference Maschler and Estlein2008:312) have argued that the syntactic category of ‘discourse marker’, like other syntactic categories (cf. Hopper & Thompson Reference Hopper and Thompson1984; Ramat & Ricca Reference Ramat and Ricca1994), is a scalar one. This is true also for ya′ani/ya′anu. All Pattern A ya′ani/ya′anu tokens fulfill the semantic requirement for discourse markerhood. They often do not fulfill the structural requirement, in which case they constitute nonprototypical DMs (Maschler Reference Maschler2009:27ff). The status of Pattern B ya′ani/ya′anu tokens as DMs, by contrast, is more questionable, as they always refer first and foremost to some entity in the extralingual world. At the same time, however, they function metalingually in the realm of relations of speaker to his/her utterance. Pattern B tokens also tend not to fulfill the structural requirement for discourse markerhood, as they often occur in non-intonation-unit initial position. Pattern A and B variants thus differ also with respect to metalinguality and structure (prosody and position within intonation unit and turn), and consequently in terms of their prototypicality within the DM syntactic category.

Based on a collection excerpted from the Haifa corpus of spoken Hebrew (Maschler et al. Reference Maschler, Polak-Yitzhaki, Fishman, Shapiro, Goretsky, Aghion and Fofliger2019), the goal of this article is to explore each stance-taking pattern and analyze the diversification of ya′ani/ya′anu in view of the social and ideological dynamics of Arabic-Hebrew language contact in Israel. Following a comparative overview of Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu vis-à-vis Arabic yaʕni, we investigate Pattern A ya′ani/ya′anu. We then explore Pattern B ya′ani/ya′anu. We conclude by proposing an explanation for the emergence of Pattern B, by discussing possible contact-induced changes of meaning that DMs undergo. Finally, we offer some reflections on the stylistic role played by ya′ani/ya′anu and the indexical values it has come to assume in current Hebrew discourse.

HEBREW YA′ANI /YA′ANU VS. ARABIC YAʕNI

The DM yaʕni is found across a great number of Arabic dialects. Importantly, it exists in varieties that have been in extended contact with Modern Hebrew, either local Palestinian dialects, or the vernaculars spoken by Jewish immigrants from other Arab countries.

Formally, Arabic yaʕni is a third-person masculine singular imperfect verb, derived from the root ʕ-n-y ‘to mean/to intend’. As a DM, yaʕni is never inflected for person, number, or gender. Incorporated into Hebrew, the form undergoes two changes. First, it adapts to standard Modern Hebrew phonology, so that the pharyngeal /ʕ/ is realized as a glottal stop. Second, while in Arabic the DM presents the single form yaʕni, in Hebrew there have emerged other forms besides ya′ani. Most frequent among these is ya′anu, which according to (dialectal) Arabic morphology could be analyzed as a third-person plural form. In our corpus, ya′anu is as frequently employed as ya′ani. Other, far less frequent, variants are ya′antu, ya′eni, and ya′enu. However, these are not attested in our corpus.

In its capacity as DM, Arabic yaʕni functions metalingually. The relation between the conceptual denotata of yaʕni, that is, ‘meaning’ or ‘intention’, and its metalingual functions is quite transparent. In an earlier study of yaʕni in Egyptian Arabic spontaneous discourse, it was observed that yaʕni serves to facilitate the (re)formulation of ideas that the speaker displays as the locally most satisfying expressions of his/her communicative intentions (Marmorstein Reference Marmorstein2016). This basic function underlies the variety of uses of yaʕni in Egyptian Arabic, and is arguably present in other dialects where these uses of yaʕni are attested.

For the great majority of Hebrew speakers, the lexical source of ya′ani/ya′anu is unknown. While the root ʕ-n-y does exist in the Hebrew lexicon, it carries meanings that are either not present in Arabic (‘to answer’), or that in Arabic too are not associated with the DM (e.g. ‘to suffer or impose distress’). However, what is carried over from Arabic to Hebrew is the metalingual function of this item, which is put to use in contexts similar to those observed for Arabic yaʕni (as seen in excerpts (1) and (2)).

A final and crucial aspect in respect to which ya′ani/ya′anu and yaʕni differ is their frequency of use and distribution. Arabic yaʕni is one of the most frequently employed DMs in spontaneous speech,Footnote 3 a fact that has obviously affected its migration not only into Hebrew, but also into other languages of the region, such as Persian and Turkish. Moreover, while yaʕni is clearly an index of conversational language (Marmorstein Reference Marmorstein2019), it is not marked for a particular spoken register. In Hebrew, by contrast, ya′ani/ya′anu is employed far less and is limited to a markedly informal spoken register (see below).

We have identified five different functions for ya′ani/ya′anu in our data (Marmorstein & Maschler Reference Marmorstein and Maschler2017). Functions (i)–(iii) are observed also for Arabic yaʕni (Marmorstein Reference Marmorstein2016, Reference Marmorstein2019), whereas functions (iv) and (v) appear to be Hebrew innovations.

(i) Reformulating (both self- and other-initiated)

(ii) Floor-holding during the processing of new information

(iii) Quotative

(iv) Focus marking

(v) Ironic hedge

In the present article we explore only a subset of class (i) and class (v), in which the two variants of ya′ani/ya′anu implement stance-taking.

PATTERN A: STANCE-TAKING VIA YA′ANI /YA′ANU-FRAMED REFORMULATIONS

Reformulating is the most common function of both Hebrew ya′ani and Arabic yaʕni. In our Hebrew data 63% (twenty-four out of thirty-eight) of all ya′ani/ya′anu tokens implement reformulations.

Reformulation has been dealt with in the literature both as a cognitive-semantic and as an interactional concept. Taking a relevance-theory perspective, Blackmore (Reference Blackmore1997), for example, defines reformulation as a relation between two resembling utterances, whereby the latter evokes an interpretative representation of the first. Resemblance, according to Blackmore (Reference Blackmore1997:6), ‘may hold in virtue of similarities in phonetic and phonological form, or in lexical and syntactic form, or in logical properties’.

While in Blackmore's view, as well as in those of others, reformulation is a relation that holds between utterances or ‘text spans’ (Mann & Thompson Reference Mann and Sandra1988), in interaction-based approaches (re)formulation is primarily conceived of as meta-communicative actions, such as describing the conversation, explaining it, characterizing it, explicating, translating, summarizing, or furnishing the gist of the conversation (Garfinkel & Sacks Reference Garfinkel, Sacks, McKinney and Tiryakian1970:350). Heritage & Watson (Reference Heritage, Watson and Psathas1979) operationalized the term formulation to refer to responsive actions whereby recipients proffer the gist or upshot of the previous speaker's contribution, thus displaying their understanding and securing agreement as to what has been said so far. This narrower conceptualization of formulation has gained much currency in subsequent literature, specifically in relation to institutional contexts (e.g. Drew Reference Drew, Glenn, LeBaron and Mandelbaum2003; Antaki Reference Antaki, Peräkylä, Antaki, Vehviläinen and Leudar2008). Other researchers have employed this concept in less restricted fashion, including in it also various kinds of speakers’ self-formulations (see Deppermann Reference Deppermann2011) and reformulation (e.g. Keevallik Reference Keevallik2003:177ff.).

In the present study, we employ the term reformulation in the broader sense, to refer to a set of self- and other-initiated practices, whereby negotiation of or dealing with meanings and interpretations of utterances is topicalized (cf. Deppermann Reference Deppermann2011). We prefer reformulation to formulation, as we wish to underscore the retrospective nature of these practices.

In all ya′ani/ya′anu-framed reformulations, interlocutors re-address some segment or aspect of prior talk and contribute a supplemental or alternative reference to it. A ya′ani/ya′anu reformulation thus consists of two parts: the reformulated prior (Part A), that is, the re-addressed segment or aspect, and its reformulating utterance (Part B). The reformulating utterance coheres with the reformulated prior by means of explicit lexical and/or morphosyntactic reproduction, or inferentially, via evocation of the same referential contents. Thus, the reformulating utterance always contains traces of previous discourse. At the same time, it also contains something ‘new’, the expression of which is the very reason for performing the reformulation.

Structurally, then, reformulations may resemble their priors to various degrees. On one extreme, they can be almost identical with their ‘originals’, save for one aspect or feature (the ‘inevitable’ new or renewing contribution to discourse, cf. e.g. Becker's (Reference Becker, Becker and Yengoyan1979) notion of ‘speaking the past’ vs. ‘speaking the present’; Linell Reference Linell1998:165). On the other extreme, reformulations can take a completely different form vis-à-vis the segment to which they refer back. The DM ya′ani/ya′anu in both cases (and in the range in between) is an overt mark of the connection between the two parts of the reformulation, and it may be employed either preframing or postframing the reformulating utterance (Part B). When reformulation involves verbatim repetition, ya′ani/ya′anu makes explicit the communicative relevance of Part B, by marking it as not simply redundant, but as an interpretation of some aspect of Part A (see (4) below). When reformulation involves structural transformation (see (5) below), as well as when it involves only evocation of content (see (6) below), ya′ani/ya′anu makes explicit the association between Part A and Part B, which, however different on the surface, are conceptually linked.

Interlocutors may reformulate in order to enhance mutual understanding as to the previous referential contents (as in (1) and (2) above). However, they may also be concerned with enhancing interpersonal involvement and mutuality regarding the stance they take toward these contents. In such a case, reformulation does not select for further reworking (a certain aspect of) the conceptual meaning of what-has-been-said, but rather targets the ways in which the interlocutor means, thinks, or feels about what-has-been-said. As we shall see below, particular kinds of stance-reformulations are distinct in their structural and organizational properties.

Reformulation via verbatim repetition of Part A

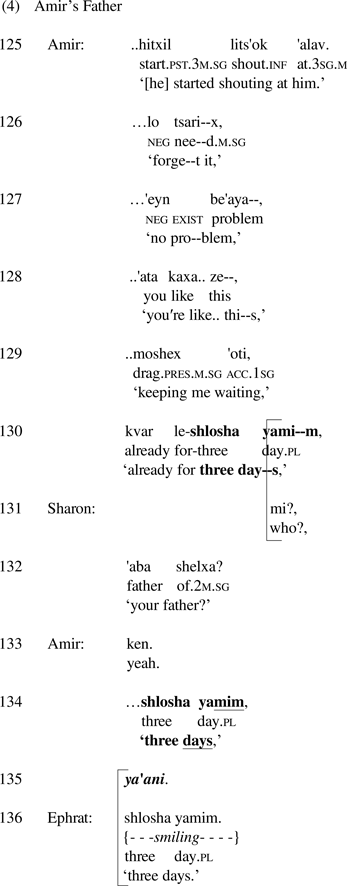

We begin with a case of verbatim repetition of Part A, in which we find a ya′ani reformulation clarifying the speaker's stance towards a stance object (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007) in an attempt to secure stance alignment with the interlocutors. In (4) below, a conversation among friends, Amir tells how bad his relationship with his father is. In the following intonation units (Chafe Reference Chafe1994), he criticizes his father for shouting at an acquaintance who had agreed to fix his computer for free, because three days had gone by without his having repaired the computer.

In the midst of Amir's outraged description of his father's complaining that the computer expert acquaintance has been keeping him waiting shlosha yamim ‘three days’ (line 130), Sharon interrupts with a clarification request, verifying that the story concerns Amir's father: mi? ′aba shelxa? ‘who? your father?’ (lines 131–32). Amir responds with a short ken ‘yeah’ (line 133), and returns to the exact same place in his narrative by repeating the end of the final prepositional phrase before the interruption. However, while Amir's shlosha yamim ‘three days’ (line 130) was verbalized with no particularly marked prosody, in the absence of an appreciative response from Sharon, and perhaps also out of concern that, being so ‘far behind’ trying to understand who the story is about, she did not get the point of the ridiculousness of the situation, the repetition of shlosha yamim ‘three days’ is marked by a prominent stress shlosha yamim (line 134) and postframed by ya′ani (line 135).

This postframing ya′ani reformulation serves to clarify Amir's previously expressed outraged ridiculing stance towards his father's behavior, at a moment of insufficient stance alignment (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Englebretson2007) with one of his interlocutors. Note that Part B here is a free constituent—an unattached NP (Ford, Fox, & Thompson Reference Ford, Fox, Thompson, Ford, Fox and Thompson2002; Couper-Kuhlen & Ono Reference Couper-Kuhlen and Ono2007)—structurally identical to Part A, except for its prosodic qualities. Ford and colleagues (Reference Ford, Fox, Thompson, Ford, Fox and Thompson2002) have argued that increments (Schegloff Reference Schegloff, Ochs, Schegloff and Thompson1996) of the unattached NP variety are employed in English conversation in the environment of lack of uptake at a transition-relevance place (TRP) (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974) in order to display a stance that provides a model for recipients for the type of response sought after by the speaker, which the recipient could then provide at a second TRP created by the increment. Although we are not dealing with an increment here, the function of the unattached NP at line 134 is similar. Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu may be employed to frame unattached NPs of this type. Indeed, overlapping the end of this stance clarification, another participant, Ephrat, displays sharedness of Amir's ridiculing stance, as evidenced by her repetition of shlosha yamim ‘three days’ (line 136) in smiling voice quality. The unattached NP followed by ya′ani thus served to provide a model for Ephrat for the type of response that Amir was seeking.

The ya′ani token at line 134 does not refer to anything in the extralingual world. It functions to postframe the verbatim repetition of Part A in an attempt to secure stance alignment. In this sense it functions metalingually as a textual DM (marking the relation between Parts A and B) as well as an interpersonal DM (attempting to secure stance alignment) (Maschler Reference Maschler2009:17, and see the Introduction above). This ya′ani token is a nonprototypical DM (Maschler Reference Maschler2009:17), because it occurs intonation-unit initially following continuing intonation (line 133) and therefore does not fulfill the structural requirement for discourse markerhood (Maschler Reference Maschler2009:17).

Reformulation via partial repetition of Part A

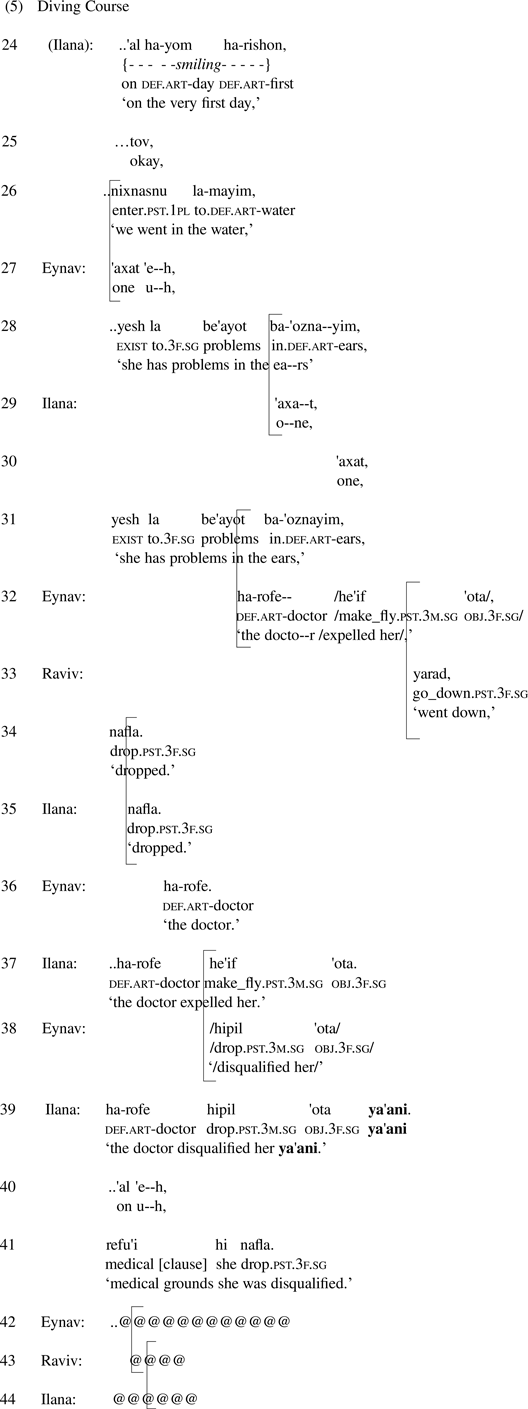

Reformulations framed by ya′ani/ya′anu may involve partial repetition of Part A. These cases manifest reproduction of the syntactic pattern and/or lexemes of Part A. In the reformulation via partial repetition illustrated in (5), ya′ani is employed to increase shared stance among participants by invoking a particular prior text (Becker Reference Becker, Becker and Yengoyan1979). Here two women, Ilana and Eynav, are humorously co-telling a man, Raviv, a narrative about a diving course they had attended with three other women friends, in the course of which more and more women kept dropping out.

Ilana, extensively ‘aided’ by Eynav, recounts here how the first woman in their group was removed from the course by the doctor because of ear problems. Ilana and Eynav both begin with ′axat, yesh la be′ayot ba-′ozna--yim, ‘one, she has problems in the ears’ (lines 27–31). Possibly echoing Eynav's contribution at line 32, Ilana first employs the informal causative verb he′if ‘expelled’, literally ‘made her fly away’, for the action taken by the doctor: ha-rofe he′if ′ota. ‘the doctor expelled her.’ (line 37). This clause constitutes Part A of the reformulation. Possibly resonating Raviv's earlier contribution of nafla ‘dropped’ (the intransitive verb) (line 34) (also echoed by Eynav in line 35), Ilana then reformulates line 37 by repeating the entire clause but replacing the causative he′if ‘expel’ with another, more ‘slangish’ causative verb, from the same root as nafla ‘dropped’—hipil ‘disqualified’, literally ‘dropped’ (the transitive verb). This reformulating utterance (Part B) is immediately followed by an intonation-unit final ya′ani: ha-rofe hipil ′ota ya′ani. ‘the doctor disqualified her ya′ani.’ (line 39), postframing Part B.

The prior-text invoked here, which is well known to all participants from their army service, is the military jargon used when dropping out of military courses due to health problems. This prior-text is made even more explicit in the speaker's following utterance, where she spells out the entire jargonish idiom: ′al ′e--h, refu′i hi nafla. ‘on u--h, medical grounds she was disqualified’ (lines 40–41). The ya′ani-reformulation at line 39, implementing an army-service characterization of the prior segment is not simply intended to enhance mutual understanding but more to create involvement—and therefore increase intersubjectivity and shared stance—by employing in-group jargon (particularly in a context of playful conversation). Indeed, we see the immediately ensuing bout of laughter by all participants (lines 42–44).

This reformulation may also be in response to Eynav's overlapping contribution (which is hard to decipher) hipil ′ota ‘disqualified’, literally ‘dropped her’ (line 38)–in which case line 39 constitutes an instance of other-initiated self-repair (Schegloff, Jefferson, & Sacks Reference Schegloff, Jefferson and Sacks1977). As argued by Keevallik for the Estonian ‘equivalent’ of ya′ani/ya′anu, tähendab (lit. ‘it means’), ‘what can be widely characterized as reformulations can occur as self-repairs’ (2003:190). Since Eynav is ‘helping’ Ilana along throughout this telling, either way, the motivation for this reformulation is enhancing interpersonal involvement. Note that unlike in (4), there is no retroactive concern here with the intelligibility of what has just been said. What motivates the reformulation of (5) is rather a prospective concern with in-group solidarity.

Again, the ya′ani token at line 39 does not refer to anything in the extralingual world. Its realm of operation is the text (marking the relation between Parts A at line 37 and B at line 39 of the reformulation) and the interaction among participants, as we have seen. It therefore fulfills the semantic requirement for discourse markerhood. However, as it occurs intonation-unit finally, it does not fulfill the structural requirement and constitutes a nonprototypical DM.

Reformulation by evocation of the content of Part A

Sometimes no structural repetition is involved, and Part B is related to Part A solely by virtue of evoking the same content. Example (6) comes from a narrative told among four university students reminiscing about junior high school days in the small town they come from.

Noga tells about a Finnish family with two beautiful twin girls who arrived in town one day (lines 25–28, 32, 34, 38). Following a short digression (lines 39–48), the speaker picks up literally where she had taken off, elaborating on the beauty of the two very blonde Finnish girls: yafo--t, blondiniyot, tsehubot tsehubot tsehubot tsehubot tsehubot ‘beautiful, blonde, yellow yellow yellow yellow yellow’ (lines 49–51). Following a short clarification sequence, in which Liat verifies that the two sisters were twins (lines 52–53), Noga's description ends with a conclusive ya′anu-projected utterance: ya′anu, xalomo ha-ratuv shel kol.. gever. ‘ya′anu, the wet dream of every.. man.’ (lines 54–55)—another free constituent in the form of an unattached NP (cf. (4)).

This is a formulation of gist (Heritage & Watson Reference Heritage, Watson and Psathas1979) concluding the previous episode by explicating its main point—that these Finnish twin girls were highly attractive. Here we find reproduction of referential content—the attractive blonde twins—but of no form. No lexemes or morphosyntactic structures are shared by Part A (lines 49–51) and Part B (line 55). This reformulation, again, is not simply intended to enhance mutual understanding but more to increase intersubjectivity and shared stance, this time by means of vivid imagery. The strategy is indeed successful, as we see from Liat's way-- ‘woa--’ (line 56) response.

All conclusive ya′ani/ya′anu tokens in our collection occur as separate intonation units, usually immediately preceding the final TCU of a multi-unit turn (constituted here by lines 49–55, punctuated by the short intervening clarification sequence at lines 52–53), preframing Part B. In other words, these ya′ani/ya′anu tokens constitute a turn-closing device. As is often the case with more extended sequence-closing sequences (Schegloff Reference Schegloff2007), the ya′anu-projected utterance provides a summarizing evaluation of material just-previously verbalized. In this way, this ya′anu reformulation, too, functions to enhance interpersonal involvement among speakers (cf. ex. (4)).

Again, the ya′anu token at line 54 operates in the realm of the text and the interaction among participants. However, unlike the tokens seen so far, it also fulfills the structural requirement for discourse markerhood, as it occurs intonation-unit initially following a final intonation contour (line 53). This ya′anu token, therefore, constitutes a prototypical DM.

PATTERN B: YA′ANI /YA′ANU AS IRONIC HEDGE

So far we have seen the role of ya′ani/ya′anu within larger constructions of stance-reformulations. The DM, in these cases, is part of an ensemble of devices that concomitantly produce the expression of stance. However, ya′ani/ya′anu also functions as a ‘stance-saturated’ (Jaffe Reference Jaffe and Jaffe2009:3) device, that is, as a linguistic resource that carries the expression of stance on its own. As such, the lexeme assumes a different prosodic form—ya′ani/ya′anu—with the stress occurring on the penultimate syllable. As mentioned above, this realization of ya′ani/ya′anu is not encountered in Arabic, nor is the meaning that it has come to convey.

In our corpus, ya′ani/ya′anu serves to modify an utterance by hedging it in a particular stance-marked way. Preceding or following the utterance with ya′ani/ya′anu indicates that the association between the utterance and the concept or state-of-affairs to which it refers in the extralingual world is a loose, pretentious, or false one. The modification marked by ya′ani/ya′anu implicates thus an ironicFootnote 4 stance, that is, a contrastive double-voiced (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin, Holquist, Emerson and Holquist1981, Reference Bakhtin, Emerson, Holquist and McGee1986; Günthner Reference Günthner, Kotthoff and Wodak1997, Reference Günthner1999) evaluation or ‘perspectivation’ (Kotthoff Reference Kotthoff, Graumann and Kallmeyer2002) of the idea alluded to by the modified segment.

Example (3), reproduced here as (7), comes from a conversation in which two secular Jewish men, Beni and Uri, are co-telling a woman, Michal, about a gathering they were invited to by a friend who had recently ‘converted’ (so-to-speak) from being a secular Jew to Ultra-Orthodox Judaism.Footnote 5 The purpose of such gatherings is to get more people to ‘convert’ to Ultra-Orthodox Judaism, a fact towards which Uri and Beni both take a highly ridiculing stance throughout the conversation. In the lines preceding this excerpt, Uri and Beni ridicule people at the gathering who had taken various actions in an attempt to ‘convert’ them. The excerpt opens with Uri relating how he had told the Rabbi taking such actions to leave him alone.

Following Uri's description of his telling the Rabbi to leave him alone, Beni sums up the episode with kitsur,Footnote 6kol ha-′erev nisu--, lehaxzir ′otanu be-tshuva. ‘anyways, all night they tried to ‘convert’ us.’ (lines 110–12). He uses the common idiom for this activity, lehaxzir bitshuva, literally ‘to bring (one) back in repentance’, that is, ‘to convert (one)’ (so-to-speak). This is followed by Uri's ya′ani (line 113) indicating his understanding that the ‘conversion’ attempts were not real. Beni then repeats ya′ani (line 114) in agreement with this modification. He then supplies an account for why this understanding is correct: ki hem lo ‘because they didn't (really try to ‘convert’ us)’ (line 115).

In employing ya′ani to modify the specific, concrete attempts at ‘conversion’, the speaker marks them as loosely and not really equivalent to the generic concept or state-of-affairs to which this utterance refers (in other words, ‘as if to attempt to “convert” us from being secular Jews to Ultra-Orthodox Judaism’). No reformulation is involved here. This is a double-voiced ironic ya′ani, by which the speaker's stance concerning the adjacent utterance is superimposed over the referential dimension of the utterance, indicating that the speaker is intending the opposite of what s/he is saying.

Since what is modified here is the referential dimension of the utterance, this ya′ani actually does refer to the extralingual world. However, in that this token of ya′ani also marks the speaker′s stance towards the utterance modified, it possesses some degree of metalinguality in the realm of relations of speaker to his/her utterance. In this sense ya′ani could perhaps be considered an interpersonal discourse marker, though very low on the scale of prototypicality (see the Introduction above).

As our spoken corpus attests only two tokens of Pattern B ya′ani, we add here some examples found on the internet, illustrating the ironic double-voiced hedging by both ya′ani and ya′anu. A Google search yields a wealth of tokens, particularly for ironic hedging ya′ani but also some for ya′anu, from which we selected the following four examples.Footnote 7

(8)

a. The title of a restaurant review by a food critic: ′iskit bela shuk: ke′ilu ′otenti, ya′ani ta′im ‘A [lunch] special in ‘la market’ [name of restaurant in the center of Tel Aviv]: ‘as if’ authentic, ya′ani tasty’. The highly unflattering review ends with the three assertions: lo shuk, lo ′otentit, velo kol kax ta′im ‘Not a market, not authentic, and not very tasty’.

b. A review on TripAdvisor of a hotel in Tel Aviv: kaxa nir′e xeder bemalon ya′ani5 koxavim herods betel ′aviv ‘This is what a room in Herods ya′ani 5 Star Hotel looks like’, followed by a series of photos documenting various flaws of the room, thereby attesting the ironic modification by ya′ani of the five stars.

c. The title of a recipe for a quick inexpensive salad, which a person on a budget could put together at work if one were tired of fast-food: salat ya′anukapreza ‘a ya′anu Caprese Salad’. The writer explains the ya′anu a bit further along: a real Caprese Salad contains mozzarella cheese, but the version the writer is recommending is made up of ‘salty cheese’ (gvina meluxa)—not quite authentic, nevertheless much less expensive.

d. The title of a comment on a post reviewing the film Soul kitchen on the TheMarkerCafe website: sol kitshen -- ya′anuneshama ‘Soul kitchen -- ya′anu soul’. This writer then proceeds to give a rather negative review of the film, describing it as shallow (shatuax), empty (reykani), and generally a fraud (rama′ut), in other words, not a movie that ‘speaks to the soul’.

In all of these cases, as well as in other such examples found on the internet, ya′ani/ya′anu modifies the immediately preceding or following utterance by hedging it while at the same time coloring it with the speaker′s ironic stance.

Interestingly, ya′ani as an ironic, double-voiced hedge is unattested in Arabic dialects in general. In what follows, we suggest an explanation for the emergence of this new type of ya′ani/ya′anu in Hebrew discourse.

DISCUSSION

Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu: Two processes undergone by a borrowed DM

Factors that make DMs top-most on the borrowability hierarchy (Matras Reference Matras2009:193) apparently played a distinctive role also in the transfer of Arabic yaʕni into ‘neighboring’ languages such as Hebrew. ‘Language change’, writes Matras (Reference Matras2009:310), is ‘always the product of innovations that are introduced by individual speakers in the course of discourse interaction, and which find favourable conditions of propagation throughout a sector within the speech community, and on to the speech community as a whole’. Matras points out that the term contact in language contact is, of course, a metaphor. He continues:

language ‘systems’ do not genuinely touch or even influence one another. The relevant locus of contact is the language processing apparatus of the individual multilingual speaker and the employment of this apparatus in communicative interaction. It is therefore the multilingual speaker's interaction and the factors and motivations that shape it that deserve our attention in the study of language contact. (Matras Reference Matras2009:3)

It is of course the discourse of individuals proficient in Hebrew and (to a certain extent) also in Arabic that has played a crucial role in the migration of yaʕni into Hebrew.

Many studies have shown that the borrowing of discourse markers into a language is the result of language alternation phenomena (‘code-switching’) among multilinguals (e.g. Brody Reference Brody1987; Maschler Reference Maschler1988, Reference Maschler1994, Reference Maschler2000a,Reference Maschlerb; Salmons Reference Salmons1990; De Rooij Reference De Rooij1996; Matras Reference Matras1998, Reference Matras2000, Reference Matras2009; Goss & Salmons Reference Goss and Salmons2000; Auer & Maschler Reference Auer and Maschler2016). Maschler (Reference Maschler1994) argues that language alternation at discourse markers comes about because bilingual discourse affords the unique strategy of iconically separating the discourse from its metalingual frame by verbalizing each of the two in a different language. Matras (Reference Matras1998, Reference Matras2000, Reference Matras2009), by contrast, suggests that the motivation is cognitive rather than discourse strategic, since by automatizing language choice of DMs, bilinguals’ cognitive overload is unconsciously reduced. Either way, over time such language alternation phenomena become sedimented in the language of bilinguals (see Maschler Reference Maschler2000b), forming a fused lect (Auer Reference Auer1999), and later they come to be employed also by the speech community at large.

In many cases, Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu retains (mutatis mutandis) the form and the function it has in Arabic. This fact evidences the primacy of the metalingual function of Arabic yaʕni over its literal meaning. While the latter is lost for most Hebrew speakers, the first is retained and is in fact the productive force behind the further development of this DM in Hebrew.

When a DM migrates into another language, it is the language games (Wittgenstein Reference Wittgenstein and Anscombe1958) repeated over and over again in the new language and culture (cf. Auer & Maschler Reference Auer and Maschler2016:43) and the particular ecology of DMs in the recipient language that ultimately determine the particular uses of the borrowed form. In what follows, we argue that the emergence of ya′ani/ya′anu should be attributed to its association with another Hebrew DM, ke′ilu (‘like’, lit. ‘as if’), which shares much functional territory with Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu but is far more frequent—1,102 tokens (vs. only thirty-eight tokens of ya′ani/ya′anu in the same corpus).

As mentioned earlier, five functions were identified in our data for Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu, only the first three of which are observed also for Arabic yaʕni.

(i) Reformulating (both self- and other-initiated)

(ii) Floor-holding during the processing of new information

(iii) Quotative

(iv) Focus marking

(v) Ironic hedge

Previous studies of Hebrew ke′ilu (Maschler Reference Maschler2002b, Reference Maschler2009) at a much earlier state of the construction of the Haifa corpus of spoken Hebrew (the earliest fifty conversations collected, comprising 150 minutes of talk recorded during 1993–2002 among 124 different speakers) found the following functional distribution for the 120 ke′ilu tokens employedFootnote 8 (Maschler Reference Maschler2009).

(9)

a. Self-rephrasal (both self- and other-initiated) (48.3%)

b. Focus marker (29.2%)

c. Hedge (13.3%)

d. Literally (the conjunction ‘as if’) (5.8%)

e. Quotative (3.2%)

We see that despite the great difference in the frequency of ke′ilu vs. ya′ani/ya′anu in the corpus, ke′ilu, too, is employed most frequently in reformulations (or self-rephrasals, as they are termed in Maschler Reference Maschler2002b, Reference Maschler2009). Besides the function of reformulation, ke′ilu shares with Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu the functions of focus marker, hedge, and quotative (see also Maschler Reference Maschler2009:156–57, 160, n. 32). Since Arabic yaʕni does not function as hedge or focus marker in the particular ways ke′ilu does, it is highly likely that ya′ani/ya′anu has accumulated these two functions by analogy to Hebrew ke′ilu.

Interestingly, though, unlike ke′ilu, Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu is not employed as a regular hedge but only as an ironic one. In what follows we explain this finding. Hebrew ke′ilu originates in a completely different lexical source compared to that of Arabic yaʕni—crucially, a source that is transparent for Hebrew speakers. It is composed of the preposition of comparison and approximation ke- ‘as’ followed by the irrealis conditional conjunction ′ilu, thus literally ‘as if’. The use of ke′ilu for hedging (approximative meaning) is therefore motivated by its literal sense. More specifically, ke′ilu can be used also for ironic hedging often resulting in sheer parody, as attested by a newspaper review of the Miss Israel contest, entitled ke′ilu malkot yofi ‘ke′ilu Miss Universes’. In dripping sarcasm, the women in the contest are described floating in gondolas in a hotel in Las Vegas, of which one of the floors was reconstructed as Venice. Sarcasm is directed also at the host of this event, Nir Xaxlili, who is known, according to the journalist, as ‘the Israeli Richard Gere’.

lo be′emet venetsia, ke′ilu. vexaxlili hu ke′ilu richard gir. ve“malkat hayofi” hi ke′ilu malkat yofi. veha′ish baxalifat hadonald dak bedisnilend hu ke′ilu donald dak. kax shelo tsarix lehizda′em mitaxarut malkat hayofi. ze misxak beke′ilu. harov yod′im sheha′ish baxalifat hadonald dak ′eyneno donald dak, veshehabaxura hanirgeshet ′im haketer ′al harosh ′eynena malkat hayofi.

′ela she-20 hamo′amadot hasofiyot lo behexrax yod′ot shehakol ke′ilu. lo yod′ot shehen ke′ilu 20 hamo′amadot hasofiyot betaxarut ke′ilu malkat hayofi. ze ′ikron hake′ilu: kedey lihiyot “ke′ilu” yesh lehityaxes ′elav ke′el “be′emet”.

mila ktana, ke′ilu. yesh lishkol lehosifa lato′ar: “ke′ilu malkat hayofi”.

‘Not really Venice, ke′ilu. And Xaxlili is ke′ilu Richard Gere. And “the beauty queen” is a ke′ilu beauty queen. And the man in the Donald Duck suit in Disneyland is ke′ilu Donald Duck. So there's no need to become enraged about the beauty queen contest. It's a game of ke′ilu. Most people know that the man in the Donald Duck suit is not Donald Duck, and that the ecstatic young woman with the crown on her head is not the beauty queen.

But the final twenty candidates don't necessarily know it's all ke′ilu. Don't know that they are ke′ilu the final twenty candidates in the ke′ilu beauty queen contest. This is the ke′ilu principle: in order to be a ke′ilu one must relate to it as real.

A tiny word, ke′ilu. One should consider adding it to the title: “the ke′ilu beauty queen” (Alper Reference Alper2000, Ha′aretz daily newspaper, translation YM).’

(Maschler Reference Maschler2002b:254–55)We would like to suggest that this ironic use of hedging ke′ilu has affected the emergent use of Hebrew ya′ani as a hedge (‘kind of’), but—perhaps because of ya′ani’s negative indexing of Arabness at the macro-social level (at least for some Hebrew speakers, see below)—ya′ani has emerged only as a hedge overlaid by an additional ironic stance (‘kind of, but not really in my perspective’). The change in stress placement from ya′ani to ya′ani, in analogy to the penultimate stress of Hebrew ke′ilu—particularly in its exaggerated performance in ironic contexts—further supports this suggestion, as does the fact that both ya′ani/ya′anu and ke′ilu (see Maschler Reference Maschler2002a, Reference Maschler2009) often function as nonprototypical DMs.

In summary, the case of ya′ani/ya′anu illustrates two different processes that borrowed DMs may undergo.

(i) Pattern A ya′ani/ya′anu tokens show that on one hand, Hebrew speakers, though generally ignorant of the literal meaning of Arabic yaʕni (lit. ‘it means’) may use ya′ani/ya′anu for reformulation, in ways much related to its lexical semantics of ‘meaning’. The persistence feature in grammaticization (Hopper Reference Hopper, Traugott and Heine1991) is thus preserved also across languages in language contact situations.

(ii) By contrast, the case of Pattern B ya′ani/ya′anu shows how the function of a borrowed DM—precisely because of not being associated with a literal meaning—may undergo modifications and extensions, affected by the particular ecology of DMs in the recipient language, and by the sociocultural world in which it is embedded.

Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu as a social indexical

Hebrew ya′ani/ya′anu is nonfrequent overall in our corpus. Moreover, the total number of thirty-eight occurrences is produced by only nineteen (of 701) speakers. In employing ya′ani/ya′anu, these speakers draw upon a markedly informal variety of their language. Indeed, dictionaries of Modern Hebrew label ya′ani, usually without mention of ya′anu,Footnote 9 as ‘casual spoken language’ (Even-Shoshan Reference Even-Shoshan2003) or ‘common language’ (Avneyon Reference Avneyon1998). Interestingly, in the Rav-Milim Online Dictionary, ya′ani and ke′ilu are differentiated, so that ke′ilu, listed as an explanatory term of ya′ani, is labeled ‘casual spoken language’, whereas ya′ani is ranked lower on the scale of informality and labeled ‘slang’.

As slang vocabulary, the import of ya′ani/ya′anu does not reside in its referential content, but in its social utility, specifically, in the ways it serves ‘to establish or reinforce social identity or cohesiveness within a group or with a trend or fashion in society at large’ (Eble Reference Eble1996:11). Slang, as a distinct speech style, is essentially a linguistic resource for stance-taking (cf. Rickford & Eckert Reference Rickford, Eckert, Eckert and Rickford2001; Coupland Reference Coupland2007): its informal flavor serves to index interlocutors’ ‘casual’ personae and appeal for in-group solidarity while, at a higher level, indicate alignment with more global and enduring social categories and ideologies (Ochs Reference Ochs1993), particularly such viewed as nonhegemonic (Allen Reference Allen and Mesthrie2001).

Arabic vocabulary incorporated into Hebrew—by way of borrowing from local (Palestinian) Arabic, by ‘imposition’ (van Coetsem Reference van Coetsem1988:3) through the agency of speakers of Judeo-Arabic vernaculars, or via some differently motivated strategy of language alternation at DMs (Maschler Reference Maschler1994) employed by Hebrew/Judeo-Arabic bilinguals—is overwhelmingly recognized as slang. In fact, Arabic lexicon constitutes the lion's share of a class of ‘code words’ (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal2001:77–78) in Hebrew, consisting of DMs and other elements regulating conversation and expressing speakers’ epistemic and emotive stances. These words are highly frequent, in fact inescapable, in any type of daily interaction (see also Henkin-Roitfarb Reference Henkin-Roitfarb2011:66–70).

The deep penetration of Arabic into Modern Hebrew, specifically in the realm of everyday discourse, should be traced to the history of the contact between speakers of both languages. The contact with local Arab communities in the early stages of Jewish revival in Palestine (from late nineteenth century up until 1948) induced extensive borrowing into reviving Modern Hebrew by both language planners and pioneers. As Henkin-Roitfarb points out:

For the former [i.e. language planners] Arabic was a particularly archaic, therefore authentic relative of Ancient Hebrew. For the latter [i.e. pioneers], it was part of the Zionist ideal of kibuš ha-adamá ve-ha-lašon ‘conquest of the Land and the Language’. As the contemporary indigenous language in the Land of Zion, it would add the local biblical flavor that could join the pioneer with his forefathers, erase the centuries of exile, and establish a local Israeli identity that would fit into the larger local environment and milieu. (Henkin-Roitfarb Reference Henkin-Roitfarb2011:70)

However, this ideological stance toward Arabic has considerably changed in the decades that have transpired since the establishment of the state of Israel. First, the ongoing political conflict has eroded the positive sociocultural attributes once associated with Arabness in Jewish-Israeli society (Henkin-Roitfarb Reference Henkin-Roitfarb2011). Second, given the dominant European orientation of Israeli culture in the formative and early period of statehood (Blanc Reference Blanc, Fishman, Ferguson and Gupta1968), cultural import of non-European, specifically Mizrahi,Footnote 10 immigrants was far less endorsed, if not rejected. Thus, linguistic features originating in Judeo-Arabic vernaculars often did not enter wide circulation, but remained in the confines of ‘peripheral’ sociolects (Henshke Reference Henshke2013). Moreover, the adoption of Westernizing ideologies and the preference for English as the prestige ‘donor’ of new lexicon has pushed Arabic even farther out of the scene (Marʕi Reference Marʕi and Benziman2013; Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal2001). All of this has resulted in a sharp decrease in the number of new Arabic loans and in the social devaluation and withdrawal of previous borrowings.

The component ya′ani/ya′anu is slang that did not go out of fashion altogether. The speakers in our corpus never employ it in a stereotyping fashion (e.g. for ridicule) but rather use it as an organic part of their vocabulary, whether consciously or not associating it with its Arabic origin and, more specifically, with a general ideology favoring Arabic. Still, the fact that this use is overall rather minor may be an implicit indication of its diminished social utility.

Meta-discourse, by contrast, provides explicit indication of the depreciative ideologies underlying the low frequency of ya′ani/ya′anu. For example, in the online quick-question forum Stips,Footnote 11 there are quite a few discussions dedicated to clarifying the meaning of ya′ani and ya′anu.Footnote 12 Users occasionally reveal negative and quite racist stances toward these terms, evaluating them as ‘annoying’ words, as ‘street language’, or ascribing them to the speech style of ′arsim, a pejorative referring to lout persona, used predominantly for Mizrahi men.Footnote 13 On the Fxp website, in a discussion launched by the question ‘Do you say ya′ani or ya′anu?’, one finds even stronger assertions of the scornful attitude toward these terms.Footnote 14 Thus, one user declares that he does not say this ‘inferior’ (tat-rama) word, and another user comments ‘A word of Arabs. I don't say (it)’ (mila shel ′aravim. lo ′omer). Unlike Hebrew ke′ilu, which serves to translate or paraphrase ya′ani/ya′anu in these discussions, and is treated as socially ‘neutral’ nowadays,Footnote 15ya′ani/ya′anu is clearly imbued with negative social meanings associated with nonhegemonic ethnic and religious groups often lumped together, such as Arabs and Mizrahi Jews (cf. Lefkowitz Reference Lefkowitz2004).

Perhaps the most explicit articulation of the depreciative ideology which ya′ani/ya′anu has come to signify is to be found in a speech delivered by the former head of the ISA (Israeli Security Agency), Avi Dichter, at the annual summit of the Christians United for Israel organization held in Washington DC on July 2017.Footnote 16 Dichter describes ya′ani as “a very essential word we are using in order to define our neighbors; sometimes they become our enemies”. He refers to ya′ani as an “untranslatable” term and explains that it may refer to an existing state of affairs, to the opposite state, and to “everything in between”. In other words, ya′ani is a word signifying a vague, or ‘kind-of’ truth, which, according to Dichter, is characteristic of the culture from which the double-faced and untrustworthy conduct of the Palestinian leaders emerges. That the modifying ya′ani, by contrast to ke′ilu, has become a dedicated means for expressing a double-voiced ironic stance may be subtly related to such depreciative ideologies. Being/doing X ya′ani, that is, in a pretentious or false manner, also resonates the racist Hebrew expression ‘Arab work’ (′avoda ′aravit), which refers to work done in poor quality, in a degraded form, or not in the proper manner.

Importantly, the former discussion refers to the social meanings of ya′ani/ya′anu in a particular section of the population of Hebrew speakers in Israel. Practice and ideology can be radically different for other sections of the population, such as Hebrew-Arabic bilingual speakers or speakers for whom Arabic is a heritage language (cf. Henshke Reference Henshke2013). Further investigation is required to assess the full indexical potential of ya′ani/ya′anu in Israeli society.

To conclude, this article explored two stance-taking patterns in Modern Hebrew involving the element ya′ani/ya′anu of Arabic origin. It was suggested that the loss of the root meaning of ya′ani/ya′anu enables two different processes, namely, the replication of the metalingual function of the Arabic DM (Pattern A), and the emergence of a new modifying function, affected by the association of ya′ani/ya′anu with the Hebrew DM ke′ilu (Pattern B). The limited use of both patterns and the negative nuance that the latter pattern has come to assume were explained by a depreciative ideology toward Arabic in modern-day Israel. The case of ya′ani/ya′anu corroborates the broader idea that both cognitive and social pressures affect the migration, rise, and (possible) fall of lexemes in language contact situations.

Appendix: Transcription and glossing conventions