Introduction

Copper-base technology was transmitted across central Asia and reached north-western China by the late third millennium BC, where several sites on the Gansu-Qinghai uplands have been identified (Mei Reference Mei2004). Copper/bronze technology was then adopted in the Longshan sites of the Central Plains, followed by the rise of piece-mould casting of ornaments, weapons and sumptuary vessels at sites such as Erlitou and its contemporaries.

Two contrasting hypotheses have evolved to explain when and by what means knowledge of copper-base technology reached Southeast Asia. The first contends that copper-base technology reached north-east Thailand by 2000–1800 BC via contact with Seima-Turbino practitioners from the Eurasian steppes (White & Hamilton Reference White, Hamilton, Roberts and Thornton2014, Reference White and Hamilton2019). The second hypothesis traces the southward transmission of knowledge along multiple routes that incorporated the early states of the Central Plains—via the middle reaches of the Yangtze into Lingnan and along the Qinhai-Tibet Plateau—by c. 1100 BC (Pigott & Ciarla Reference Pigott, Ciarla, Niece, Hook and Craddock2007; Higham et al. Reference Higham2011a, Reference Higham2011b, Reference Higham2015; Higham Reference Higham2023). Resolution of these alternative hypotheses will be expedited by the discovery, evaluation and dating of early copper-exploitation sites along the Qinghai-Tibet route (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Southeast Asia showing the location of Jicha and other sites mentioned in the text. Yellow arrow indicates the corridor (figure by authors).

Jicha: the key site

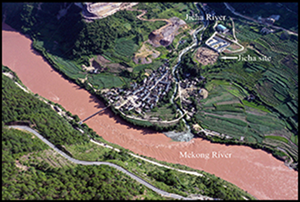

In this article, we present the first results from Jicha, a site located strategically on the most direct, logical route of transmission—at the junction of the Mekong, the Yongchun and the Jicha rivers (Figure 2). Excavations in 2022 revealed a cultural sequence that covers Late Neolithic, Early and Late Bronze Age contexts and the Iron Age occupation.

Figure 2. Landscape of Jicha looking to the south-west (figure by authors).

Chronology and the occupation sequence

Nineteen radiocarbon samples have been subjected to Bayesian modelling (Figure 3). The Late Neolithic remains are characterised by elaborate ‘incised and impressed’ patterns on pottery (Figure 4), that are found upstream at Karuo and downstream at Haimenkou, which reveals the wide distribution of this instantly recognised style in the early communities. The Early Bronze Age is identified by the presence of painted pottery, reflecting the influence of the painted-pottery cultures of north-western China (Figure 4.7). The crucial dating for the first evidence for this phase comes from three radiocarbon determinations on rice grains and one on bone (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bayesian age model for Jicha 14C dates (figure by authors).

Figure 4. Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age remains: 1 & 2) Early Bronze Age remains, as burnt layers and structures raised on piles; 3 & 4) Late Neolithic pottery; 5–7) Early Bronze Age pottery (figure by authors).

The site was reoccupied c. 700 BC, during the Late Bronze Age, and included a residential area of stone-walled buildings and a burial ground comprising 54 burials (Figure 5). The northern part of settlement contained half-crypt structures thought to have been animal pens. Industrial activity involved copper smelting and casting and firing charcoal or pottery in a kiln. One-fifth of the burials contained flagstones and all contained infants under two years of age. Mortuary offerings included handled pottery vessels and bronze pendants (Figure 6). The final occupation took place during the Early Iron Age (c. 300–0 BC), after which the site was abandoned, probably due to landslips following heavy rains.

Figure 5. Jicha during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age occupation: 1) debris flows deposition; 2) stone foundation structure; 3) half-crypt pen; 4) metallurgical area; 5) inner ditch and nearby structure; 6) pavement (figure by authors).

Figure 6. Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age metallurgical remains from Jicha: 1–3) in-ground furnace with nozzle; 4 & 5) tuyères; 6) copper-base droplet; 7) charcoal entrapped in slag; 8) crucible fragment with lining; 9) copper ore; 10 &11) ceramic moulds for a handled mirror and an axe; 12–16) bronze ornaments from infants’ burials (figure by authors).

Metallurgical remains

The chaîne opératoire of metallurgical production during the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age can be reconstructed based on the 1000-plus stone tools that were found for ore mining and processing—such as pestles, hammers, anvils and mortars (Figure 6). There were also bowl-shaped in-ground furnaces and nozzles from bellows. There was no typical type of lining (i.e. a fire-resistant technique frequently used in south-west China and Southeast Asia (Vernon et al. Reference Vernon, White, Hamilton, White and Hamilton2019)) at the base of the furnaces, so it is suggested that they were probably used for alloying and casting. Dozens of ceramic tuyères lay in the encircling ditches and one crucible fragment with an inner sandy lining was found; 20 ceramic and five stone moulds for casting an axe, knife and a handled mirror were located. The copper-base artefacts were awls, needles, bracelets, pendants and beads. Slag was rare, but there were several copper-base droplets of casting splatter.

Conclusions

The strategic location and Bayesian-modelled chronology for Jicha make it a key site in tracing the southward transmission of copper-base technology. There has been a recent surge in the number of radiocarbon chronologies available for key sites in Southeast Asia—from Oakaie in Myanmar to Vilabouly in Laos and including sites in Thailand—which are unanimous in dating the first evidence for copper-base technology to 1200–1000 BC (Higham et al. Reference Higham2015, Reference Higham2020; Pryce et al. Reference Pryce2018; Cadet et al. Reference Cadet2019). The new information from Jicha supports the hypothesis that expertise in copper mining, smelting and casting travelled south from north-west China as skilled practitioners moved in that direction during the second half of the second millennium BC. However, this does not exclude other transmission routes; for example, the dissemination of techniques from the highly sophisticated Shang Culture via Lingnan and the Red River into Southeast Asia (Pigott & Ciarla Reference Pigott, Ciarla, Niece, Hook and Craddock2007; Ciarla Reference Ciarla, Higham and Kim2022). Research along the course of the Mekong River has identified two other sites from which we will obtain further vital chronological information and data on metal production, exchange networks and subsistence strategies at Jicha and related sites.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Professor Vincent Pigott and Professor Xueping Ji for their technical expertise and their support on the framework of this article.

Funding statement

This work was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2022FY101505), the National Natural Science Fund of China (T2350410495) and Sichuan University (SKSYL2023-05 & 2035xd-02).