INTRODUCTION

The Institute of Advanced Legal Studies (IALS) sits within the School of Advanced Study at the University of London. At IALS Library, one of the many impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic has been a shift in ways of working. Before the pandemic, the librarians at IALS were used to working each day in the same office, just a chair swivel away from a quick catch-up on the status of our projects and day-to-day work. In the post-pandemic world we have found that our timetables mean overlapping onsite less frequently.

Like many workplaces we have moved to a hybrid model, with staff spending some days working from home and some days working on-site. We have certainly felt an overall beneficial effect of this new pattern, but a side-effect has been the need to think more intentionally about how we work together and communicate.

In the Academic Services team, one tool we have adopted is the use of Kanban boards. We began our exploration of Kanban boards with a project to develop a new training workshop.

In this article, we will introduce the concept of Kanban boards and then explain how we used a Kanban board to help us plan and deliver a successful workshop.

WHAT IS KANBAN?

Kanban is a Japanese word that translates as ‘signboard’ or ‘visual signal’.Footnote 1 The use of kanban cards as a tool for organising work activities has its origins in manufacturing. Developed at Toyota in the 1940s, kanban cards formed part of the Toyota Production System which is “based on the philosophy of achieving the complete elimination of all waste in pursuit of the most efficient methods”.Footnote 2 At Toyota, kanban cards were devised as a way to manage the flow of manufacturing parts, ensuring that precisely the correct quantity of parts was available at just the right time. Over time, other industries have adapted kanban cards to suit their own needs. Kanban has notably been adopted in software engineering, with an early proponent being David J Anderson, who introduced the Kanban Method to Microsoft.Footnote 3

Kanban should also be contextualised within the overarching concept of ‘Agile’. Agile is an approach to managing work and projects which is widely used in the technology sector, particularly for software development. Agile has come to be understood as an umbrella term for a certain kind of approach to working. The philosophy behind Agile software development is laid out in the Manifesto for Agile Software DevelopmentFootnote 4 which outlines four key values:

• Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

• Working software over comprehensive documentation

• Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

• Responding to change over following a plan

Using Kanban is just one methodology that a team might adopt to work in an Agile way. An example of another very popular methodology is Scrum, but there are numerous Agile frameworks available.Footnote 5

Whilst Kanban systems have become well known and commonplace in software development, they are not limited to manufacturing or technology companies. Kanban can be applied to a wide range of activities that would benefit from controlling the quantity of ‘things’ inside the systemFootnote 6 (whereas at Toyota the ‘things’ were physical parts used for manufacturing, in knowledge-based work the ‘things’ might be a single task or activity). In this article, we describe Kanban systems as used in knowledge work, as opposed to more physical occupations such as manufacturing.

Kanban acts as a framework that can be used to help both projects and day-to-day work to proceed more effectively. The basic ingredients of a Kanban system as it is widely used today are boards, columns and cards.

• Kanban board. The Kanban board is your workspace. A board might represent the work of a single team, or a particular type of work that involves people from different teams. Boards can be physical or digital.

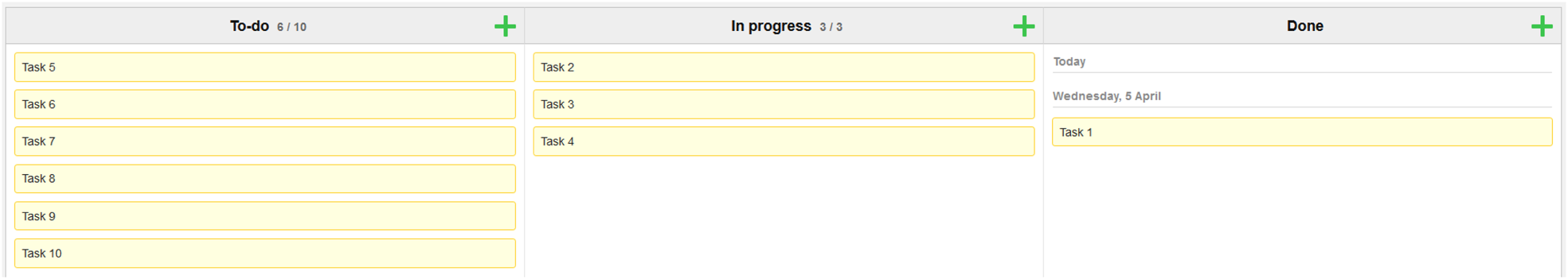

• Columns. At its most simple a Kanban board consists of three columns, titled ‘to do’, ‘in progress’ and ‘done’, although these columns can (and should) be adapted to suit the requirements of the business. The columns create the structure for a ‘flow’ of work across the board.

• Cards. Within the columns, cards are added. Each card represents a single activity or task. The aim is to move cards across the board, from ‘to do’ until they reach ‘done’.

KANBAN IS A VISUAL SYSTEM

As described, a Kanban board is fundamentally a visual control system. Board members can easily track the flow of work and see which cards have been completed, which are currently underway, and what is still to come. In this way Kanban boards are inherently transparent.

KANBAN LIMITS WORK IN PROGRESS

An important aspect of a Kanban board is the work in progress (WIP) limit. The WIP limit elevates a board from a simple visualisation of tasks to a Kanban system. The ‘in progress’ column should have a pre-agreed WIP limit – this defines how many cards are allowed to be in this column at a single time. If there are fewer cards in the in progress column than the limit allows for, this prompts a team member to pick up a new card and move it into the in progress column. In this way Kanban boards operate as a ‘pull’ system, where the work is being pulled across the board by the workers, as opposed to work being ‘pushed’ (delegated) onto the team members by a manager. Limiting WIP further encourages focused attention and discourages excessive multi-tasking.

KANBAN RESPECTS EXISTING ROLES

Using a Kanban board does not require teams to all follow exactly the same set of processes or to agree to dramatic changes in the way they work. Rather, each board will be unique. ‘Start with what you do now’ is the first step to setting up a Kanban board. The Kanban board can be amended later on to better suit redesigned policies and procedures. Kanban is thus a flexible framework.

KANBAN PROMOTES INCREMENTAL IMPROVEMENT

Once teams begin to use a Kanban board, they are likely to identify opportunities for improvement as it becomes easier to see where bottlenecks are occurring. For instance, if a single worker is vital to progressing all cards to ‘done’ this person is going to cause a bottleneck and hold up the flow of cards across the board. The issue may be solved by upskilling other team members.

KANBAN IN LIS CONTEXTS

When considering the Kanban board as a framework for developing a new training workshop, we wanted to find out how other libraries had used Kanban boards. Whilst we did find some examples, this does not seem to be a widespread practice in library and information settings.

Figure 1: Example of a basic layout for a Kanban board, created using KanbanFlow

The management of electronic resources using Kanban appears to be the area that has received the most attention, and in this context it has been suggested to be a method that can “help manage the information overload many librarians experience daily”.Footnote 7 McLean and Canham offer case studies from the University of Saskatchewan Library and the Saskatchewan Polytechnic Library in Saskatchewan, Canada.Footnote 8 Both institutions chose to use Kanban boards for managing electronic resource workflows and found that they benefitted in terms of communication, streamlining of work, and continuous improvement.Footnote 9 A further example, from North Carolina State University Libraries, discusses their Licensing team's use of the Trello platform to track workflow.Footnote 10 Whilst this article does not explicitly use the term kanban, the system described uses a basic kanban column layout which has been tailored to the specific uses of this team – it could perhaps be described as kanban inspired.

Digitisation work is another area where Kanban has been used. A blog post from the British Library's Workflow team describes how they strive to progress items through the digitisation workflow more efficiently and effectively through use of a physical Kanban board.Footnote 11 The post describes how the tactile use of a physical board assists with managing workload, flow, and helps with a sense of achievement.

Solo librarians need not feel left out. Whilst Kanban is usually conceived as a system that will improve performance across a team, it can also be useful for personal effectiveness.Footnote 12

Whilst mentions of Kanban in the LIS literature we surveyed were infrequent, there was some evidence of interest in adopting Agile methodologies more generally. An informative article from colleagues at Middle Temple Library describes how they used an Agile approach to assist with a large book moves project, adopting the Scrum methodology.Footnote 13

BACKGROUND TO THE WORKSHOP PROJECT

The IALS has a small cohort of its own masters, MPhil and PhD students. In the Library, we also admit law master's degree students from certain University of London colleges (Birkbeck, King's College, LSE, UCL and SOAS). In addition, we admit MPhil / PhD students and academic staff from any university.

To help our members make the most of the resources available at IALS Library, we run a programme of regular training sessions. The training session that is most popular is something that concerns law students up and down the UK: OSCOLA.

The Oxford University Standard for the Citation of Legal Authorities (OSCOLA) is the citation standard used by many law schools in the UK and beyond. We know that OSCOLA is something that our members, especially those at master's level, are often concerned about. Our Introduction to OSCOLA training session is consistently the most popular session we offer, OSCOLA is the subject of many one-to-one appointments (especially in the summer months when students are writing their dissertations), and our OSCOLA Library GuideFootnote 14 is the most popular guide on our website. Feedback indicated that whilst the students appreciated the introductory session we already offered, there was an appetite for a more in-depth and hands-on approach to getting to grips with OSCOLA. This is why, in autumn 2022, we decided to create a brand new OSCOLA workshop.

We would create a session where smaller groups of students who already understood the basics of OSCOLA would have a chance to practise, with a particular focus on the areas we find students tend to struggle with the most. We wanted the session to have less talking from the librarians, and give the students a chance to ‘have a go’. We also wanted to foster a space for discussion and for students to feel emboldened to voice all of the questions they might feel too shy to ask in a much bigger group. Our ultimate aim for the workshop was to have students leave feeling confident about using OSCOLA, and able to focus more of their energy on conducting their legal research and writing (because no one has come to law school to worry about whether to use a square bracket or a round one). This was to be different to the other training sessions we offer, which tend to be more instructor led.

The workshop would be designed and delivered by the Academic Services Manager, Laura Griffiths, and the Access Librarian, Alice Tyson.

WHY DID WE CHOOSE TO USE KANBAN FOR THIS PROJECT?

Our current pattern of working means that we (Laura and Alice) are scheduled to be on-site together one day per week. Add in our regular on-site library duties such as covering the Enquiry and Reference Desks, annual leave, and rota swaps, and in practice we see one another face-to-face less than weekly. Scheduling online calls could also be tricky at times, given our full calendars.

The small window for ad hoc updates and scheduled meetings meant we knew we needed to be more intentional about discussion of the project and updating one another on the progress of our work. Not keen to overload our inboxes with ever more emails, we looked for a different solution. This is when we came up with the idea of using a Kanban board to plan and manage the project work.

HOW WE USED KANBAN FOR THIS PROJECT

An early decision was whether to use a physical or online board. Due to our hybrid working arrangement, an online board that could be accessed and updated in real time was the obvious choice. There are numerous free options for small teams who want to create a Kanban board. We decided to use Trello,Footnote 15 as it was a platform one of us had used before, it's free, and it's easy to learn.

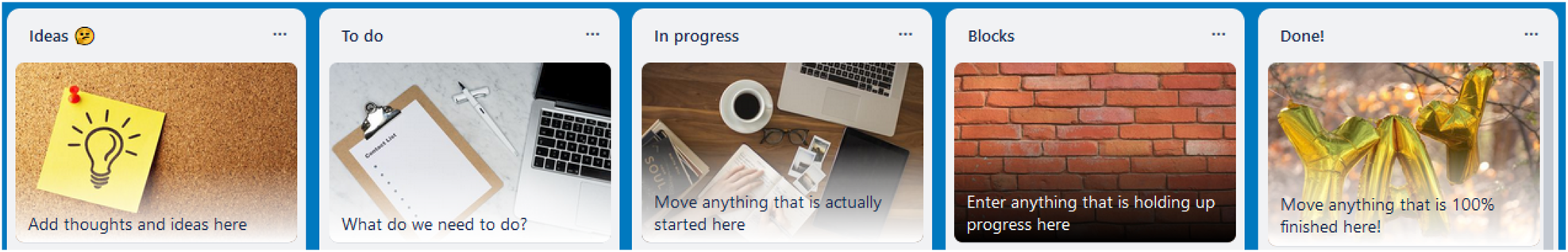

We set up the Trello board with the basic columns of ‘To do’, ‘In progress’ and ‘Done’. In addition we added a ‘Blocks’ column, as a place to park any cards that we had started but were temporarily unable to progress. We also added a column for ‘Ideas’. Arguably Ideas does not belong on the Kanban board, as the suggestions added here would not necessarily all be taken forward across the board. However, we felt it made sense to include the Ideas column so that we could keep track of as much of the workshop development in one place as possible.

Figure 2: The column headings on our Kanban board (image taken from Trello)

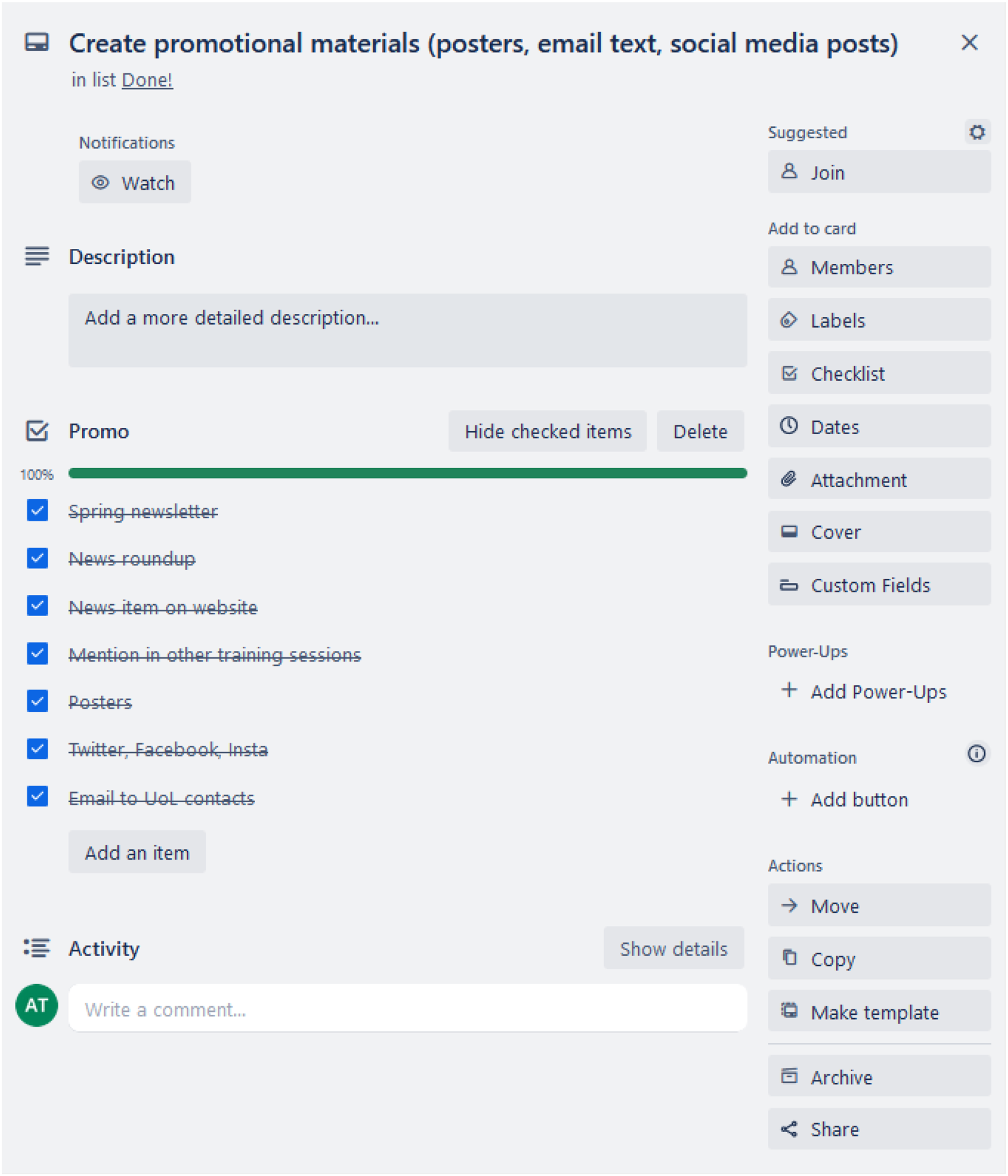

To finish setting up the board we had to add cards to the ‘To do’ column. This is where the ‘start with what you do now’ ethos of Kanban came into play. Both of us have been organising training sessions at IALS Library for a number of years, so between us we had a good idea of what would need to happen. We brainstormed the tasks that we would need to complete from the earliest stages of the project (write a project overview) to the last task (implement changes based on feedback). We tried to place the cards in a rough order, so that the tasks which needed to be completed next would appear at the top of the ‘To do’ column. We ended up with around 30 cards, some of which were further broken down by adding checklists.

Over time, we got into the rhythm of selecting a card to work on, progressing it across the board, and moving on to the next card.

THE KANBAN BOARD AS A TOOL FOR COMMUNICATION

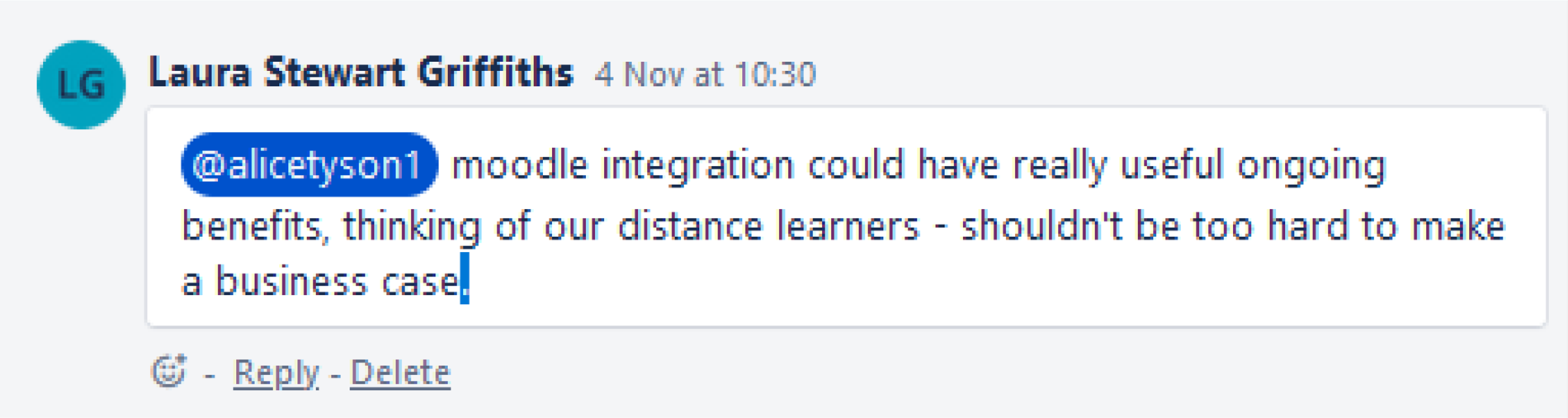

As mentioned above, we had very little time for actual face-to-face collaboration, so the majority of our communication on the project was done via the Kanban board itself. Boards are updated in real time, so we were able to see any changes made as they happened and could easily check on each other's progress at a glance, avoiding any ambiguity of task ownership and obviating the need for constant status update enquiries.

Trello allows users to set up notifications (pop-up alerts or emails), so we could each receive an alert when the other had made changes on the board, but the information itself was located on the specific card. This meant that all communications relating to the project were stored in the same place and there was no feeling of ‘email overload’ which can sometimes accompany a project. By the same token, the communication on the board acts as a kind of feedback loop, with comments and suggestions remaining on the various cards to provide guidance and insight should the board be reused for a future project.

Communicating in this way alleviated the need for frequent meetings. Overall we met around five times during the project. Because we both already had clear and up-to-date knowledge of what stage the project was at, we were able to focus meeting time on problem solving and making decisions.

ADVANTAGES OF THE PROJECT

As discussed above, improved communication was a major advantage of using a Kanban board for this project. We also found Kanban to be highly adaptable to our existing ways of working and very flexible. From the outset we had a clear understanding of the overarching goals of the project, but as things progressed our ideas matured and diverged from our early plans. With Kanban this was not a problem, we were able to simply update and re-order the cards waiting in our to-do list.

A less-anticipated advantage was the psychological benefit of using the board. The visual layout helped us feel in control and avoided the sinking feeling of tasks piling up. Moving cards across the board was surprisingly motivating and gave us a sense of steady progress.

Finally, the basics of Kanban were easy to learn without the need for extensive research or training. This meant we were able to get the project off the ground quickly, gradually improving our Kanban board and learning as we went.

LIMITS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE LIS COMMUNITY

We found Kanban to be very beneficial in this small-scale project and firmly believe its flexibility and ease makes it well suited to a multitude of projects, service improvements and routine work regularly carried out in library and information settings. That said, Kanban is not a silver bullet, and each project or activity should be carefully considered for its suitability to this approach.

Where a project is deficient in resources (time, funding, expertise) Kanban alone will not make a success of it. Additionally, projects that are poorly scoped will still struggle; whilst Kanban is flexible and adaptable, it is still necessary to have a good understanding of what tasks need to be completed and cards need to be populated with enough information for team-members to work on them effectively. For work that is already very efficient or simple to do, it would be prudent to consider whether introducing a Kanban board would be beneficial or merely add extra and unnecessary steps.

Figure 3: An example of a card with a completed checklist (image taken from Trello)

Figure 4: Detail from a card showing how we communicated throughout the project (image taken from Trello)

CONCLUSION

As unlikely as it may seem, our experience is that this system designed to streamline car production in 1940s Japan slots perfectly into a modern LIS workplace. Although started as a means to control physical ‘bits’ of work in progress, it has relevance today against a landscape of hybrid working, digital collections and remote meetings. It is perhaps the very simplicity of a Kanban board that makes it such a rich and dynamic tool. Although this article has discussed in detail the theory and potential uses of Kanban, a board speaks for itself – a real time snapshot of where your team are on various projects, which could potentially be used to identify areas of concern at a glance.

It is also possible that such an open and transparent method of collaborating is particularly suited to our sector of information management. The LIS field has long been a highly collaborative profession, with librarians generally happy to share resources and information for the greater good, all of which is facilitated by the Kanban method. Kanban has the potential to encourage open communication, empower staff at all levels to contribute ideas, and foster a sense of ownership over tasks and projects. At its most basic, it is the best version of a to-do list we have ever used. A small system with a big application, the Kanban method is here to stay at IALS Library.