The colloquially named ‘psychoanalytic drawings’ are a series of images produced by the American artist Jackson Pollock while he was receiving Jungian analysis between 1939 and 1940. Pollock, born in 1912, is well-known for both his large-scale abstract expressionist paintings and his lifelong mental health issues. From an early age he was noted to display delayed speech, truancy and excessive alcohol consumption. By the time he began therapy he additionally presented with: rapid mood swings, violence (including sexual assault), visual disturbances, impulsivity, antisocial behaviour and suicidal ideation.

Pollock entered Jungian analysis following an admission to hospital for alcoholism and his therapist was a young psychiatrist named Joseph Henderson, who had received analysis from Jung himself. Henderson initially struggled with Pollock's difficulties expressing himself verbally and so encouraged Pollock to draw at home and then present his work in the sessions, as a non-verbal form of free association.

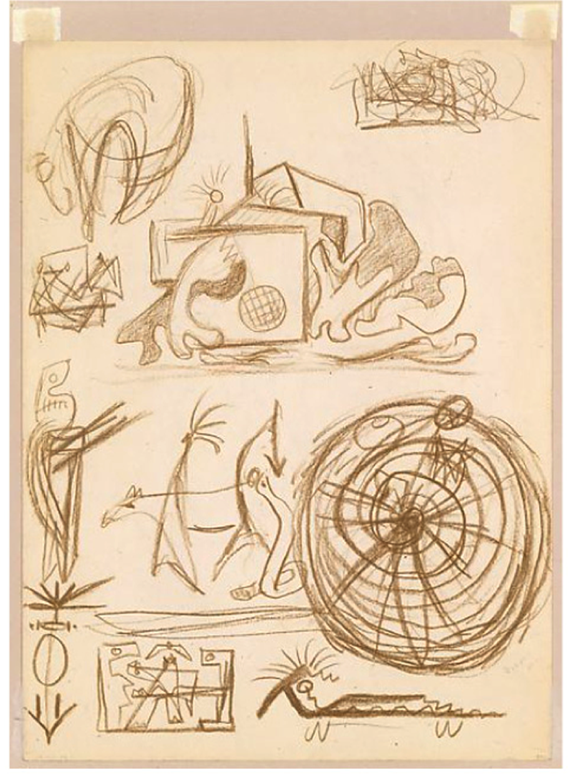

Although we do not have access to Henderson's full analysis, academics agree the drawings do suggest psychoanalytic experiences. At first glance, they are complex, seemingly disorganised and perhaps read as stylistic for Pollock (even though they actually pre-date his signature drip-style paintings). Featured throughout are a range of subjects, primarily imagery from across Native and Indigenous cultures. In one drawing there is a prominent hermaphroditic figure, an icon reappearing in Pollock's subsequent works. It is thought that these suggest that Pollock was perhaps working with Jungian themes such as those of individuation, the collective unconscious and anima.

After the therapy ended Henderson presented his work with Pollock to the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute. In this unpublished paper he formulated that the drawings had allowed Pollock to tap into his unconscious mind. Then in 1970, Henderson sold 80 drawings to a private gallery, in order to fund his own psychiatric research. They were then exhibited across America before being published shortly afterwards in a book, to the consternation of both psychiatrists and Pollock's widow, the artist Lee Krasner. Although Krasner did not object to the drawings themselves having been made public, she criticised Pollock's psychiatric notes from Henderson being included alongside them. Krasner attempted to sue Henderson, although the case was dismissed. The court ruled that writings concerning an artist's life did not require restriction, evoking a debate regarding the privacy of a public figure.

Although it remains unclear how much of an impact the drawings had on the artist himself, in a rare statement made many years after therapy Pollock stated: ‘I'm a little representational all the time. But when you're painting out of your unconscious, figures are bound to emerge.’Reference Leja1

Although trusts such as the Adamson Collection preserve and archive art produced by people with mental health issues, it remains a rarity for catalogues such as the psychoanalytic drawings to exist. Despite the historical ethical issues the publication raised, what the drawings offer us now is a rare opportunity into the mind of both a famous artist coupled with a workable psychiatric history, and thus a much more complete window into the unconsciousness.

Jackson Pollock. Untitled (Psychoanalytic Drawing), c. 1939–40. Reproduced with permission: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (metmuseum.org)

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.