Forensic mental health services for children and adolescents are still in a process of development. Nevertheless, in recent years there has been considerable progress in the provision of coherent approaches to the assessment, care and support of young offenders and/or young people who present with high-risk behaviours and significant emotional and mental health difficulties: what we call here ‘high-risk young people’.Footnote a

Concerns about the welfare of young people who come into contact with the criminal justice system have been voiced over the past 200 years (Reference Hagell, Hazel and ShawHagell 2004). Throughout the 20th century, policy in relation to young people involved in criminal activity or antisocial behaviour resulted in a range of programmes and institutional developments, some of which were characterised by greater emphasis on education and welfare, whereas others emphasised regimes based on punishment and deterrence.

In England during the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, there was a predominantly educational emphasis on the therapeutic needs of young people in the youth justice institutional setting. The advent of two ‘youth treatment centres’, St Charles and Glenthorne (Reference Bullock, Little and MillhamBullock 1998), during the 1970s in England led to greater involvement of core mental health disciplines in rehabilitation programmes. Specific interest in the mental health needs of young people in the youth justice system developed further in the 1980s, with specialist in-patient mental health secure provision for young people in Manchester and Newcastle (Reference Bailey, Thornton and WeaverBailey 1994) and an increase in mental health liaison work within secure children's homes and custodial settings.

The passing of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 in England and Wales resulted in a systematic attempt to reform the youth justice system. This was embodied by the formation of the Youth Justice Board and multidisciplinary youth offending teams (YOTs), which explicitly included healthcare practitioners. There was also greater attention given to sentencing reform, with more emphasis on non-custodial sentences. More recently, across the UK there has been even greater emphasis on diversion from custody and on pre-court diversion from the youth justice system, with the favouring of prevention, diversion and desistance (as described by Reference Lightowler, Orr and VaswaniLightowler and colleagues (2014) in Scotland) over the reactive and more punitive approach previously in place. This has been supported in England and Wales within the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, in Scotland by the provisions of the Children's Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011 and in Northern Ireland by the Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002, which places emphasis on prevention and restorative justice through a youth conferencing system.

Further specific development of mental health provision for high-risk young people, who often have highly complex presentations and needs, has accompanied the developments in youth justice policy and practice. The network of secure mental health in-patient provision has grown. Furthermore, there has been greater emphasis on the development of a mental health care pathway that places greater emphasis on supporting and coordinating cross-agency provision for this group of children and young people. Specialist community forensic child and adolescent mental health services (FCAMHS) now exist in some parts of the UK. There is still no secure mental health in-patient provision for young mentally disordered offenders (or those with mental health needs outside the youth justice system who present high risk of harm to others) in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.

Underlying principles and concepts

‘Child and adolescent’ or ‘adolescent’?

This article will refer to children and adolescents under 18 years old collectively as ‘young people’, and use the specific terms ‘child/children’ or ‘adolescent/adolescents’ only in relation to those under 12 and over 12 respectively.Footnote b We recommend the use of the term ‘child and adolescent’ to denote the overall care pathway of forensic mental health provision for children and young people. This emphasises that such a care pathway is available to all young people under 18. It does not mean, however, that individual parts of the care pathway may not be specifically intended for one specific age group.

‘Mental disorder’

For the purposes of this article ‘mental disorder’ refers to both mental health and neurodevelopmental difficulties, including intellectual (learning) difficulties. Some child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) services and commissioners make a distinction between such categories and may not include young people with intellectual, other neurodevelopmental and conduct difficulties within an overall CAMH provision. This is not the case for the FCAMHS pathway, which necessarily should be inclusive and take a broad view of the term mental disorder.

Attributes of a forensic mental health service

The term ‘forensic’ is derived from the Latin word for court (forum) and it has acquired a range of meanings in modern usage – for example:

-

• relating to the courts or criminal justice system

-

• indicating analysis of a specific issue in detail

-

• relating to shocking or high-profile violent crime

-

• defining a range of high-risk psychiatric patients.

When ‘forensic’ is used in relation to a mental health service, the term is used to denote a broad range of such functions irrespective of whether the service works with adults or young people (see Reference Gunn and TaylorGunn & Taylor 2014). These include:

-

• working at the interface between mental health and legal/criminal justice provision

-

• working in prisons and a range of secure or highly supervised settings

-

• evaluating risk

-

• working in community settings with other agencies to identify and supervise high-risk individuals with mental health needs; this requires strong emphasis on supporting formulation, care planning and risk management

-

• experience in a wide range of therapeutic interventions

-

• identifying the needs of victims and understanding victims as perpetrators (Reference Lengua, Bailey and DolanLengua 2004).

Why have child and adolescent forensic services?

Box 1 outlines reasons for specific child and adolescent forensic services: these are essentially those that dictate the desirability of dedicated services for young people in any arena. Such specialist services should not be ‘stand-alone’, but should have clearly defined areas of expertise and an emphasis on close working with other mental health professionals and colleagues in other agencies.

BOX 1 Why do we need specialist forensic child and adolescent mental health services (FCAMHS)?

Young people, in comparison with adults:

-

• are subject to ongoing development in multiple domains

-

• suffer from mental disorders that are conceptualised and managed in very different ways

-

• are subject to a complex range of statutory provision, principally the Children Act 1989 and 2004, Education Act 2011 and youth justice provision, in addition to the Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended 2007) and Mental Capacity Act 2005

-

• are supported by professional networks that differ significantly from those designed for adults.

FCAMHS:

-

• provide a specialist service for high-risk young people that is not otherwise available

-

• ensure clear links between youth justice provision (community and custodial), other secure or specialist settings for high-risk young people and core provision whether within specific CAMHS or other services.

The FCAMHS care pathway:

-

• aids early intervention in high-risk cases as a means of improving outcomes and reducing risk and vulnerability.

Key principles underlying the work of child and adolescent forensic services

A forensic mental health service working with high-risk young people, whether based in a community, in-patient or custodial setting, should be founded on a number of key principles. Such principles include:

-

• ensuring that team members have specialist competencies in the identification and treatment of mental disorders in young people, together with similar competencies in forensic mental health

-

• ensuring that primacy is given to the needs of young people as guided by relevant welfare legislation (e.g. Children Act 1989; Children (Scotland) Act 1995 or The Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995), that the principle of proportionality (Reference Curtice, Bashir and KhurmiCurtice 2011) is respected, and that the least restrictive treatment measures are used to meet identified needs and prevent harm to others (United Nations General Assembly 1991)

-

• ensuring that there is a clear understanding of the principles of children's safeguarding (HM Government 2015) and knowledge of the means of escalating concerns both in individual cases and where systemic failings are encountered

-

• understanding of the range of provision within children's services as a whole in which high-risk young people with mental disorders may be encountered; this includes practical understanding of the means whereby access to and, if necessary, transfer from such provision can be facilitated

-

• maintaining clarity of purpose and a clear understanding of the interplay between specialist and generic mental health functions in everyday clinical work; for example, what may be considered generic CAMHS work in an everyday community setting may become the responsibility of an FCAMHS clinician if a young person is in a highly specialist custodial, residential or educational setting

-

• ensuring initial ease of access to the service for families and professionals who have concerns about emotional and mental issues in relation to a high-risk young person

-

• maintaining close links at all times with families or others with parental responsibility for young people

-

• ensuring clear links both clinically and strategically between local, regional and national provision and supporting transition of young people to adult mental health or other provision as required.

Where are the young people that FCAMHS work with?

It is a frequent misconception that FCAMHS work only with young people in contact with the youth justice system. In reality, such services are predicated on the fact that they work with high-risk young people about whom there are mental health concerns; this means that they need to cater for young people both within and outside youth justice settings and processes.

The statistics that monitor young people's contact with the youth justice system in England and Wales are reviewed annually. The most recent statistics cover the year 2014–2015 (Ministry of Justice 2016) and are summarised in Table 1. It will be noted that numbers of formal community and custodial ‘disposals’ for young people have decreased dramatically since 2002. It is thus the case that, outside of formal youth justice provision, there are many young people involved in high-risk behaviours who are supported within a range of welfare secure and residential, specialist educational, voluntary sector and other provision (including their own families). There is a further group of young people who do not benefit from support of this kind and who, as a result, give particular cause for concern. These two groups and the professionals trying to work with them frequently require specialist input from FCAMHS with regard to the interplay between risk, mental health difficulties and the young person's developmental needs.

TABLE 1 Young people who offend: contact with the youth justice system in England and Wales (2014–2015)

High-risk young people may be found in a range of secure settings subject to welfare, mental health and youth justice statutory jurisdictions (Table 2). It will be noted that at any one time in 2015 there were about 1450 young people under 18 in secure settings in England.

TABLE 2 Numbers of young people in secure provision in England at any one time (2014–2015)a

High-risk young people and mental health difficulties

The high rate of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorder in adolescent offender populations is well documented. Table 3 compares the prevalence of various mental disorders in adolescents in normal community samples with those involved in offending behaviour. Reference HagellHagell (2002) summarised the UK prevalence of diagnosed disorders among young people in custody (range: 46–81%) and young offenders in the community (range: 25–77%), and emphasised that conduct and oppositional diagnoses are the most frequent, often occurring in association with other diagnosable disorders such as those in Table 3. High rates of neurodevelopmental difficulties among adolescent offenders have been emphasised by Reference Hughes, Williams and ChitsabesanHughes et al (2012). Other studies have confirmed the high levels not only of diagnoses of emotional and behavioural disturbance, but of more general comorbid ‘complex needs’ (among which are ‘looked after’ status,Footnote c substance misuse, special educational needs, previous experience of abuse and family disruption) (Reference Lader, Singleton and MeltzerLader 2000; Reference Kroll, Rothwell and BradleyKroll 2002; Reference Harrington, Bailey and ChitsabesanHarrington 2005; Reference Chitsabesan, Kroll and BaileyChitsabesan 2006; Health in Justice LLP 2010; Reference Daniells, Speed and ScaresDaniells 2011).

TABLE 3 Mental disorder in adolescents in the general population and in criminal justice settings

Scope and organisation of existing provision

Dedicated FCAMHS are specialist services that should be regarded as complementary to core service provision for all young people. In this way, young people can receive services as close to their homes as possible and in contexts with which they are familiar. In principle, concerns about risk or about emotional or mental health should initially be considered by ‘universal’ services (e.g. within education, children's social care or primary healthcare). However, in some cases more specialist services will be required to meet emotional or mental health needs and risk of harm to others (e.g. residential and specialist educational placements, youth offending services and custodial settings, local CAMHS teams, ‘open’ CAMHS in-patient units). Where such solutions to meeting a young person's needs and risk are not successful, or where more specialist advice is required, FCAMHS intervention may be sought. This can give rise, particularly where specialist in-patient provision is required, to a dilemma for service providers and commissioners, namely the tension between the need for specialism available in only a few centres in the UK and the geographical dislocation of the young person from their family and familiar local surroundings.

This organisational framework represents a graded or tiered approach to high-risk young people with mental health problems (similar to that proposed by Reference Williams, Bailey and DolanWilliams (2004)). It should serve as a guide and not be rigidly and unquestioningly adhered to – the complex contexts and situations in which high-risk young people may present require a more flexible approach to ensure that exceptional circumstances giving rise to high professional concern (which, with this particular group of young people, arise quite frequently) are dealt with rapidly and effectively. In such circumstances, FCAMHS involvement may serve either to contain anxiety or to escalate professional concern.

Dedicated FCAMHS provision refers to services commissioned specifically to fulfil the functions outlined in Box 2. In practice this has resulted in the development of in-patient and community services whose functions should be complementary and have some degree of overlap. Other services may provide some of these functions, but these services usually do not have the capacity or expertise to undertake the full range of functions provided by FCAMHS.

BOX 2 Core functions of services within the child and adolescent forensic care pathway (in-patient and community FCAMHS)

-

• Specialist expertise in the assessment, treatment, management and care of high-risk young people in secure settings

-

• Advice, formal consultation and clinical assessment/intervention, irrespective of setting, in response to family or professional concerns about mental disorder in young people who present with perceived high risk of harm to others and/or are in contact with the youth justice system

-

• Evaluation of risk both in relation to mental disorder and more generally in collaboration with families and other agencies

-

• Ability and willingness to become involved in the multi-agency management of the most complex cases involving young people; understanding of cross-agency arrangements for funding of specialist placements; understanding of different statutory jurisdictions

-

• Liaison and a clear understanding of the working of relevant custodial (SCH/STC/YOI)Footnote a and welfare secure provision as well as other specialist residential, educational and community youth justice provision

-

• Close relationship with youth offending teams and support to courts, including specialist forensic court assessments (such as fitness to plead/appear in court; appropriate ‘disposal’ for young person under relevant youth justice, welfare or mental health legislation)

-

• Provision of training in relation to mental health and risk in young people for professionals in universal services (health, social services, education), those in more specialist provision (YOTsFootnote a and custodial settings) and mental health workers wanting to specialise in this area of work

-

• Service development functions: ability to identify areas of specific need and gaps in provision locally, regionally and nationally, and ability to work with key stakeholders (e.g. health and social care commissioners, safeguarding children boards, voluntary and independent sector providers, patients and their carers or families) to develop service improvements

-

• Evaluation: ongoing service evaluation to include quantitative service data, qualitative evaluation of feedback from young people, their families and carers, and referrers to the service, together with information relating to service outcomes

a SCH, secure children's home; STC, secure training centre; YOI, young offender institution; YOT, youth offending team.

In-patient provision

National coverage in England for forensic adolescent in-patient needs is ensured in part by an NHS England commissioned network of medium secure units distributed geographically across England. In December 2015 the lead commissioner at NHS England (personal communication) confirmed the following: five of these units (with 73 beds in total) provided care for young people with mental disorder and high-risk behaviours for which they may or may not have received convictions; a further two units (27 beds in total) provided for young people with intellectual (learning) disability whose circumstances were similar. There are no medium secure adolescent in-patient units in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland, but the medium secure provision in England can be made available to the rest of the UK under separate and individual commissioning arrangements.

Further provision for high-risk young people with mental health or neurodevelopmental difficulties who do not require conditions of medium security is available in a range of low secure and other secure in-patient units (principally, psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs)) managed largely by independent healthcare providers; precise statistics regarding people in such settings on grounds of risk of harm to others are not available, but numbers significantly exceed those in medium secure settings (see Table 2).

A relatively small proportion of young people in secure settings in England (roughly 16%) are found in mental health units, despite the high prevalence of mental health difficulties in young people who offend. This reflects the fact that the majority of young people who offend can either receive assessment and treatment for mental health difficulties by mental health liaison teams within custodial or welfare secure units or can be managed in non-secure mental health, community youth justice, specialist residential or educational settings. Admission of a young person to a secure setting on mental health grounds should always occur under the jurisdiction of the Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended in 2007) and only when this is considered to be the most appropriate option to meet the young person's needs (NHS Health Advisory Service 1994).

Community provision

Community FCAMHS provision has developed significantly since the introduction of in-patient services, but remains heterogeneous in terms of both geographical coverage and commissioning arrangements, resulting in large areas of the UK with no access to any specifically commissioned local or regional community FCAMHS (Reference Dent, Peto and GriffinDent 2013). Areas without access to such provision may have to rely on ‘spot-purchased’ assessments and advice about case management and intervention from services with national coverage. Advantages of a service commissioned for a given catchment over spot-purchasing arrangements are discussed by Reference Dent, Peto and GriffinDent et al (2013). There remain ongoing difficulties with establishing a suitable commissioning framework to ensure equitable access to services with regional catchments in England and elsewhere.

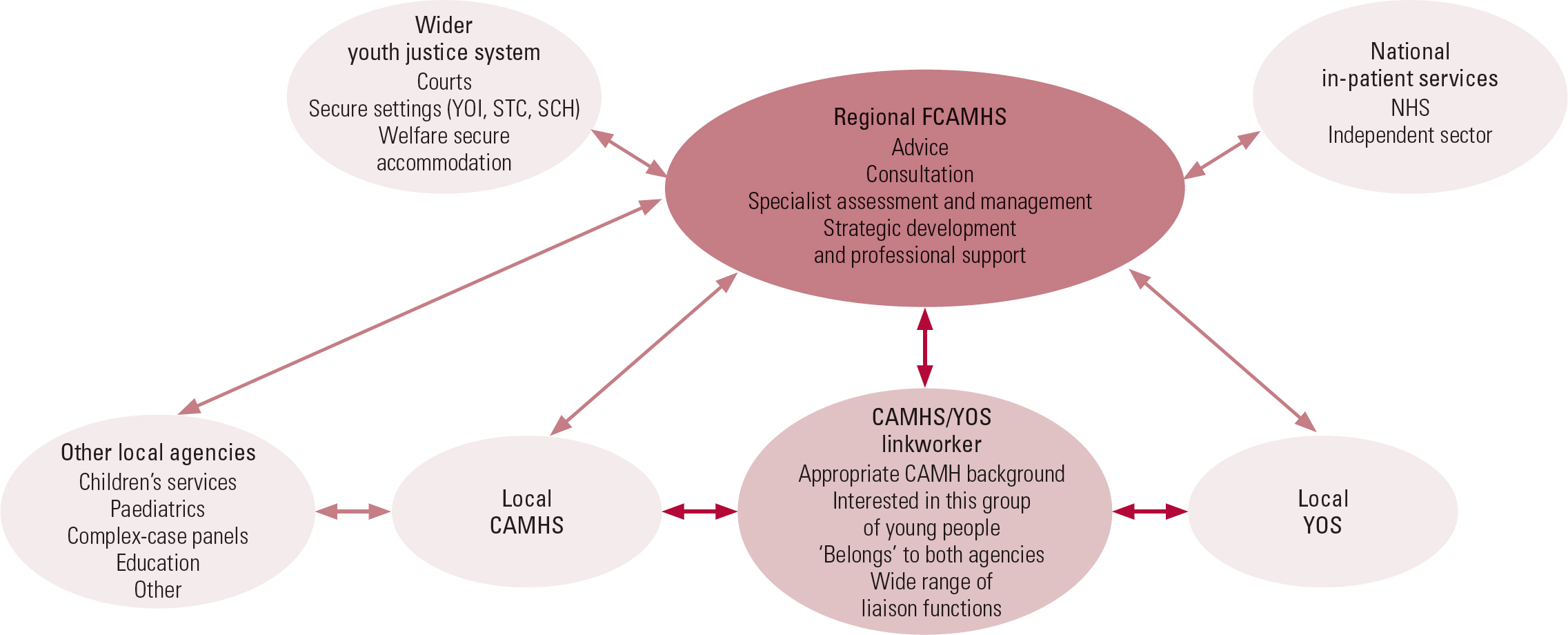

In some areas where it has been possible to develop and sustain a commissioned catchment-based regional forensic service, evaluation and validation of a working service model (as described by Dent et al) has received widespread approval. In brief, community FCAMHS should be small and should consist of clinicians with specialist awareness and experience of working with high-risk young people, who frequently have complex needs and are involved with a number of different agencies. A community FCAMHS may include psychiatrists, clinical and forensic psychologists, nurses, social workers and other allied disciplines. Dent et al propose that the services should ideally serve a given catchment area (total population of about 2–2.5 million) and should form a specialist (‘tier 4’) part of existing CAMHS provision. Team members should have highly developed liaison skills (with local, regional and national services; Fig. 1) and an understanding of the varying statutory jurisdictions and range of community and residential settings that influence and contain high-risk young people. Above all, such services should understand how to facilitate and mediate positive change and containment for young people who give cause for significant family and professional concern; paramount in such circumstances is accessibility, the provision of clear formulations, attention to detail and emphasis on practical case management. In addition, FCAMHS should be able to provide therapeutic interventions for young people where they are best placed to do this either because of the young person's specific needs or the absence of other appropriate service provision (Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health 2014).

FIG 1 A service model for community forensic child and adolescent mental health services (FCAMHS).

SCH, secure children's home; STC, secure training centre; YOI, young offender institution; YOS, youth offending service.

The ascertainmentFootnote d and consultation role of community FCAMHS, in terms of identifying high-risk young people with mental health and other needs, is of great importance. This is especially true because a significant proportion of such young people will not be within the youth justice system and their risks and needs may not have been adequately assessed. For this reason, such services should be easily accessible to all professionals and should respond to family and professional concerns rather than solely to proven and established high-risk situations where mental health need has been definitively established.

Other sources of support for high-risk young people with mental health needs

A number of types of service exist which, although not providing the overarching, regional and national levels of provision available from FCAMH in-patient and community services, are nevertheless experienced in working with high-risk young people. In a minority of areas (such as Oxford, Manchester, Wakefield and Newcastle) some services of this kind are clinically very closely linked with community FCAMHS and may, indeed, be commissioned to be delivered by them. This is particularly the case for harmful sexual behaviour services, the youth justice components of the recently developed criminal justice liaison and diversion teams (NHS England 2014) and mental health liaison input into YOTs and some youth justice custodial settings. The advantages of such arrangements in terms of coordinating provision at the interface between youth justice, welfare and mental healthcare are clear. Unfortunately, in many parts of the UK there is little coordination between different providers of such additional services for high-risk young people – services such as multisystemic therapy (MST) and multidimensional treatment foster care (MTFC) teams, mental health in-reach teams to youth justice and secure welfare settings, and professionals working in independent specialist residential settings and special educational settings.

Clinical needs of high-risk young people and the role of FCAMHS

There has been a tendency for the needs of high-risk young people to be regarded as different from those of their non-offending peers and for the systematic evaluation of their needs to be truncated. This occurs partly because the intrusion of perceived risk and high-risk behaviours tends to cause multidisciplinary systems to become organised around (and frequently paralysed by) such concerns at the expense of evaluation of needs, and partly because there are frequently difficulties with continuity of care and meaningful engagement with such young people. Alternatively, young people who come to be regarded as particularly disadvantaged and impaired by their life circumstances by professionals involved in providing support to them become subject to a search for successive poorly defined ‘therapeutic’ solutions at the expense of attention to high levels of risk of harm to others. In practice, risk assessment should form an integral part of any needs assessment for a young person, just as risk management should be part of any management plan designed to meet needs. Equally, the meeting of unmet need in high-risk young people usually forms an integral part of risk management.

The role of specialist FCAMHS is to assist colleagues in a range of agencies working with high-risk young people in identifying mental health need together with other vulnerabilities and needs that may impinge directly on a young person's mental health, and to undertake and support risk assessment and risk management. Although the emphasis of such work varies between the intense focus of secure in-patient settings and the more macroscopic and systemic emphasis of community FCAMH teams, many of the principal clinical requirements remain the same. These include:

-

• strong emphasis on engagement skills with young people who may react in a hostile way and whose difficulties are frequently difficult to treat

-

• capacity for longitudinal case involvement and appreciation of the value of continuity of professional involvement

-

• flexibility of response to different clinical presentations, professionals and families

-

• wide experience of universal and specialist provision for young people

-

• specific knowledge of evidence-based mental health interventions for young people, together with knowledge of additional interventions likely to be of benefit for high-risk sexual, violent and antisocial behaviours

-

• strong formulation and case management skills (including structured evaluation of risk and its management)

-

• emphasis on the need for carefully planned transitional arrangements for high-risk young people, in particular the transition from child and adolescent to adult mental health services.Footnote e

Conclusions

A danger of an article of this kind is that it creates an impression of systems and services that are well-coordinated and organised; on the contrary, the provision of services for high-risk young people across agencies throughout England, and indeed throughout the UK, remains generally fragmented and lacking in coordination. However, the past 15 years or so have seen considerable progress in the recognition and addressing of the mental health and other needs of this group of young people. It is hoped that the next 15 years will see further integration of forensic services for young people with mental disorder into overall care pathways for all young people. A significant step towards such integration is likely to be made by the recent agreement by NHS England that funding for national implementation of community FCAMHS is to be made available. This enterprise will be jointly coordinated at a national level by two departments within NHS England: Specialised Commissioning and Health and Justice.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Which of the following is not an example of key legislation applicable to children and young people in forensic settings?

-

a Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended)

-

b Disability Discrimination Act 1999

-

c Children Act 1989

-

d Mental Capacity Act 2005

-

e United Nations Resolution 46/119.

-

-

2 What proportion of adolescents in youth justice settings have an intellectual disability?

-

a 5%

-

b 10%

-

c 15%

-

d 20%

-

e 25%.

-

-

3 Which of the following secure settings for under-18-year-olds accommodate the highest numbers of young people in England?

-

a Secure children's homes

-

b Secure training centres

-

c Young offender institutions

-

d Low secure in-patient units

-

e Medium secure in-patient units.

-

-

4 Which of the following conditions is most frequent in offending populations under the age of 18?

-

a Mood disorder

-

b Psychosis

-

c Conduct disorder

-

d Intellectual and developmental disability and other learning difficulties

-

e Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

-

-

5 Which of the following is a necessary feature of FCAMHS?

-

a Insistence on detailed written referrals as the initial contact from agencies concerned about a high-risk young person

-

b Specialist understanding of the working of the youth justice system, but not of other educational or residential provision for young people

-

c Location in a prison setting

-

d Detailed knowledge of the Children Act and Mental Health Act

-

e Location in a medium secure unit.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | b | 2 | e | 3 | c | 4 | c | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.