Cows’ milk protein allergy (CMPA) is the most common food allergy in infancy, affecting 2–3 % of infants(Reference Vieira, Morais and Spolidoro1–Reference Savage and Johns4). A cows’ milk elimination diet nutritionally adequate to fulfil nutritional requirements and promote growth is essential for all patients with CMPA, not only before but also after diagnostic confirmation, and must be maintained until the child develops tolerance to milk proteins(Reference Luyt, Ball and Makwana3). In recent decades, a rise in CMPA persistence into late childhood has been shown, with half the children still on an elimination diet by 5 years of age(Reference Wood, Sicherer and Vickery5,Reference Santos, Dias and Pinheiro6) . These findings strengthen the importance of studying children on elimination diets up to 5 years of age(Reference Savage and Johns4–Reference Spergel10).

Feeding difficulties are also common in childhood, with a prevalence ranging from 25 % to 50 % in children with normal neurological development(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11). Feeding difficulties are a useful umbrella term that simply suggests there is a feeding problem of some sort(Reference Kerzner, Milano and MacLean12). Feeding difficulties encompass a broad range, from mild and transient cases with no repercussion in nutritional status to severe cases(Reference Kerzner, Milano and MacLean12) that may place children at risk for malnutrition, failure to thrive, behavioural and developmental disorders(Reference Ramsay, Martel and Porporino13).

Feeding difficulties may be associated with food allergies(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11,Reference Meyer14) , probably as a consequence of the discomfort caused by symptoms and/or by elimination diets, that can limit exposure to new foods and disrupt feeding skill acquisition and the relationship with food(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11).

As far as we know two studies have been published on feeding difficulties in infants and children fed a cows’ milk elimination diet(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15,Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16) . In a tertiary referral centre in London, an avoidant eating score(Reference Wright, Parkinson and Shipton17) was used to assess feeding difficulties in 437 children with food protein-induced gastrointestinal allergies. Avoidant eating was characterised in the presence of manifestations of food aversion, like gagging on textured foods, spitting food out and turning head away or closing mouth when food is offered(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15). Avoidant eating was found in 40 % of the children (according to information reported by parents) and was associated with the number of foods eliminated from the diet, vomiting, constipation, rectal bleeding, headaches, lethargy, night sweating, joint pain and faltering growth(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15). The other study compared sixty-six infants and children on an elimination diet and sixty controls on an unrestricted diet recruited from allergy and health visitor clinics on the Isle of Wight(Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16). Feeding difficulties were assessed through two instruments: (1) the Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (which can detect feeding problems related to the lack of motivation for eating, oral-motor deficits, food selectivity according to texture or taste)(Reference Ramsay, Martel and Porporino13); (2) the picky eater questionnaire (picky or fussy eating are terms used to describe children who accept a limited number of foods, are unwilling to try unfamiliar foods, have strong food preferences and/or other undesirable eating behaviours)(Reference Carruth, Skinner and Houck18–Reference Taylor, Wernimont and Northstone21). Considering the assessment through both instruments, participants consuming a cows’ milk elimination diet had higher scores for picky eating and feeding problems than those consuming an unrestricted diet. In this study, no relationship was found between both scores and growth. Higher scores of feeding problems using the Montreal Scale were correlated with higher number of symptoms, colic, wheezing/whistling in chest and dry cough at night(Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16).

There are still many gaps in understanding feeding difficulties in children fed elimination diets for treating CMPA, such as their frequency rates in several countries in the world, the repercussion on weight and height and whether there are associated socio-demographic, dietary and clinical characteristics, which could be used as red flags for an earlier diagnosis of feeding difficulties. It is important to emphasise that both CMPA and feeding difficulties may be accompanied by nutritional impairment(Reference Vieira, Morais and Spolidoro1,Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11,Reference Kerzner, Milano and MacLean12,Reference Meyer14,Reference Medeiros, Speridião and Sdepanian22–Reference Ercan and Tel Adıgüzel24) . So, expanded knowledge on this subject may support proposals for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of feeding difficulties and other nutritional disorders(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11,Reference Meyer14) in children with CMPA. Therefore, the objectives of this study were: (1) to compare the scores and the frequency rates of feeding difficulties (picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems using the Montreal Scale) in children aged 2–5 years fed a cows’ milk elimination diet due to food allergy, with a control group on an unrestricted diet; (2) to verify whether these three feeding difficulties are associated with socio-demographic, anthropometric, dietary and clinical data.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study to investigate picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems in children on a cows’ milk elimination diet, as well as socio-demographic, anthropometric, dietary and clinical data associated with these three feeding difficulties. A control group comprised children from the same age group who were fed an unrestricted diet.

Sample

Two groups aged 2–5 years were established: (1) the cows’ milk elimination diet group and (2) control group. The group on an elimination diet consisted of children fed a diet free of cows’ milk and dairy products, due to CMPA, for at least 6 months. Children fed a cows’ milk elimination diet due to other reasons, such as vegetarianism and lactose intolerance, were not included. The control group was composed of children with no history of CMPA and who were fed an unrestricted diet.

In order to recruit volunteers, invitations were posted on the internet in groups and fanpages of Facebook (Facebook Corporation). The search words ‘alergia ao leite de vaca’, ‘alergia alimentar’ and ‘APLV’ (in English: ‘cows’ milk allergy’, ‘food allergy’ and ‘CMPA’) were entered on the Facebook page in order to identify groups and fanpages that gather parents of children fed a cows’ milk elimination diet. The invitation disclosed in the selected groups and fanpages presented the study objectives, inclusion criteria and the link to the Free and Informed Consent Form. The researchers’ contact details were made available to clarify any questions. The same procedure was performed for the control group, except for the search words used to identify Facebook groups and fanpages, which were: ‘criança’, ‘mãe’, ‘bebê’ (in English: ‘children’, ‘mother’, ‘baby’), ‘kids’ and ‘baby’. It was not possible to estimate the number of people who read the invitations.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) insufficient questionnaire data and (2) a previous history of diseases that could require significant diet modifications or that could lead to nutritional impairment or feeding problems (e.g., coeliac disease, hypothyroidism, chronic kidney disease, autism). For the control group, living in the same home as children with CMPA was also an exclusion criterion.

Electronic forms for data collection

Data collection was performed via the Internet using electronic forms hosted on the SoGoSurvey platform. Volunteers who completed and agreed to the Terms of Free and Informed Consent had access to the research electronic forms, which contained questions to collect the following data:

-

Data related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

-

Socio-demographic, mother’s education level, family history of allergies and previous or current maternal history of food allergy (to cows’ milk or other foods). Children with two or more first-degree relatives with previous or current history of any kind of allergic disease were classified as having ‘high risk of food allergy’(Reference Koplin, Allen and Gurrin25).

-

Previous clinical manifestations related to CMPA (present before the elimination diet initiation), such as food refusal/inappetence, colic, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, blood in stools, eczema, urticaria, and faltering growth, among others; and characteristics of the elimination diet (only in the electronic form of the elimination diet group).

-

Current constipation and anticipatory gagging. Constipation and anticipatory gagging were investigated as in earlier studies about feeding difficulties(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15,Reference Levy, Levy and Zangen26–Reference de Oliveira, Jardim-Botelho and Morais30) . Anticipatory gagging was characterised as occasional or frequent retching when seeing or smelling specific foods(Reference Levine, Bachar and Tsangen27). Constipation was characterised by the presence of at least two of the following symptoms: (1) painful, uncomfortable or hard bowel movements; (2) stool consistency lower than four on the Bristol scale and (3) frequency of bowel movements every three or more days. This criterion was based on published literature(Reference Hyams, Colletti and Faure31,Reference Hyams, Di Lorenzo and Saps32) .

-

Current weight and height.

The anthropometric evaluation was based on data from medical records. Only values of weight and height measured by a paediatrician or other healthcare professional within 90 d before the inclusion date were considered. When these data were not available, parents were contacted through WhatsApp messages or e-mail and requested to inform values from medical records measured within the 90 d after the inclusion date. The child’s age on the measurement date was used to calculate the weight-for-age, height-for-age and BMI-for-age z-scores using Anthro version 3.2.2 and Anthro plus version 1.0.4 (WHO). The anthropometric classification was calculated according to the WHO recommendations as z-score < –2 sd to classify low height-for-age (stunting) and low BMI-for-age (wasting). BMI-for-age z-score > +2 sd and ≤ +3 sd was the cut-off point used to classify overweight, and obesity if > +3 sd(33).

-

Questions to assess feeding difficulties (picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems):

Taking into account that questionnaires to assess feeding difficulties were not available in Brazilian Portuguese, the following instruments previously used to study feeding difficulties in healthy children and children on elimination diets(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15,Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16) were translated into Brazilian Portuguese and adapted for this survey (online Supplementary Materials 1, 2 and 3):

-

-

Picky eating questionnaire: the instrument contained nine questions related to the child’s feeding behaviour and maternal feelings, concerns and strategies used to feed the child. It was adapted from a questionnaire developed and applied to children aged 2–7 years(Reference Carruth, Skinner and Houck18,Reference Carruth and Skinner19) . The answers to each question were scored on a Likert scale ranging from one to seven. This instrument does not define a cut-off point indicative of a picky eating diagnosis. Therefore, considering the prevalence of picky eating observed in studies conducted in Natal, Brazil (25·4 % of 301 healthy children on an unrestricted diet aged 2–6 years from public and private day care centres)(Reference Maranhão, Aguiar and Lira34) and in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (27·6 % of 3627 children aged 3 years from a prospective population-based cohort)(Reference Cano, Tiemeier and Van Hoeken20), the score corresponding to the 75th percentile of the group fed an unrestricted diet (control) was adopted as a cut-off point to characterise picky eating.

-

Avoidant eating score: the instrument contained seven questions about aversive eating behaviours (gagging on textured foods, pushing food away, holding food in the mouth, spitting food out, throwing food on the floor, crying during meal times, turning head away or closing mouth when food is offered). It was adapted from a score described in a cohort of children aged 29–33 months(Reference Wright, Parkinson and Shipton17) and modified to study children with food protein-induced gastrointestinal allergies(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15). The responses of each question were scored on a scale ranging from zero to two. The sum of points higher than five characterised children with avoidant eating behaviour.

-

Feeding problems scale (The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale): the instrument contained fourteen questions covering aspects of the oral-motor and oral-sensory domains, appetite, mealtime behaviours, maternal concerns and strategies used to feed the child and family reactions to child’s feeding behaviour. It was adapted from an instrument developed for children aged 6 months to 6 years(Reference Ramsay, Martel and Porporino13). The responses to each question were scored on a Likert scale ranging from one to seven. The sum of points higher than 45 characterised children with feeding problems.

-

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Epi-Info version 3.4.3 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), SigmaPlot version 12.5 (Systat Software) and Stata/se 15·1 (Stata-Corp, 2017; StataCorp LLC). A P-value lower than 5 % was considered in all analyses.

The sample size estimate was based on the expected prevalence of feeding difficulties characterised using the Montreal Scale. Therefore, data were obtained from the only study that compared the frequency rates of feeding difficulties among children on a cows’ milk elimination diet and children on an unrestricted diet (13·6 and 1·6 %, respectively)(Reference Meyer14). An α error of 5 %, power of 80 % and safety margin of 20 % were used to estimate a minimum number of ninety-two individuals in each group.

Data normality was tested using Shapiro–Wilk test. A two-sided P value was used in all tests. A descriptive analysis was performed where categorical variables were summarised by the number (n) and percentage (%) and non-categorical variables as mean and standard deviation or as median (P50 %) when the normality assumption was not satisfied.

Bivariate analyses compared weight and height z-scores of children with and without picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems.

For the whole sample (both groups), full multivariate logistic regression models were built in two stages to evaluate the association of the three feeding difficulties studied with socio-demographic, dietary and clinical characteristics. In the first stage, simple logistic regression models of each dependent variable, with each explanatory variable (covariates), were evaluated. From these bivariate analyses, all variables that had a P value lower than 0·20 were included in the multiple logistic regression models(Reference Kleinbaum, Kupper and Muller35). The variable ‘being fed an elimination diet’ was included in the models regardless of having a P value < 0·20 in the bivariate analyses. Explanatory variables that were not significant in this multilinear model (P ≥ 0·05) were removed one by one until the final adjusted model was reached. The same procedure was performed for the second multiple logistic regression models including only the elimination diet group to evaluate the association of the three feeding difficulties studied with past clinical manifestations of CMPA and characteristics of the elimination diet.

Cronbach α was applied to analyse the internal consistency of the three instruments used to evaluate feeding difficulties.

Ethical approval

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) (CAAE:54771616.3.0000.5505/2016).

Results

Description of sample

Data collection was performed from July 2016 to August 2017. The e-forms were completed by 275 children’s parents, of whom twenty were not included in the analysis: history of diseases that required significant diet modifications or that could cause nutritional impairment or feeding difficulties (n 12), residence outside Brazil (n 6) and control child living in the same home as children with CMPA (n 2). The elimination diet group consisted of 146 children, and the control group included 109 children on an unrestricted diet. The forms were completed predominantly by mothers, both in the elimination diet group (97·9 %) and in the control group (94·5 %, P = 0·177). The sample included participants from all Brazilian regions (Southeast, 66·3 %; South, 15·3 %; Northeast, 12·1 %; Midwest, 4·3 % and North, 2·0 %).

The groups were similar regarding age, type of delivery, proportion of premature births, birth weight and frequency of children exclusively breastfed for more than 4 months (Table 1). The group on an elimination diet exhibited higher frequency of male sex, high risk of food allergy (in children) and maternal history of food allergies. In the control group, higher socio-economic status, higher maternal education level and higher frequency of breast-feeding for more than 12 months were observed. In the elimination diet group, the assessment of current anthropometric measurements revealed higher frequency of stunting and lower z-score values for all evaluated parameters, except for BMI-for-age. The occurrence of constipation and anticipatory gagging at the time of the study was similar in both groups.

Table 1. Characteristics of the cows’ milk elimination diet and control groups

(Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations*)

* Frequency rates expressed as percentages, Pearson χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test; mean values and standard deviations, Student’s t test.

† Socio-economic status according to the Brazilian Criteria 2015 and social class distribution update for 2016, ABEP – Brazilian Association of Research Companies (http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil).

Online Supplementary Material 4 shows the frequency of the patients’ past clinical manifestations (present before starting the cows’ milk elimination diet). In 90 % of the children, the onset of clinical manifestations was in the first year of life (median age = 2 months; P25 = 0·5; P75 = 6·0).

In the elimination diet group, the median age of elimination diet initiation was 6·0 months (P25 = 3·0; P75 = 12·0). The duration of the elimination diet since the suspect of CMPA until the online survey ranged from 6 to 65·8 months (median = 29·9 months; P25 = 21·3; P75 = 38·7). Most children (63·0 %) had more than one food eliminated from the diet. In addition to cows’ milk, the most frequently eliminated foods were soyabean (37·7 %), egg (28·8 %), extensively hydrolysed protein formulas (22·6 %), peanuts (21·9 %), wheat and/or gluten (13·0 %), one or more fruits (11·0 %), colour additives (6·2 %) and beef (5·5 %). Other foods were excluded at a frequency rate lower than 5 %.

Scores and frequency of feeding difficulties

Complete data for the evaluation of feeding difficulties were obtained in more than 93 % of both groups: for picky eating in 144/146 (98·6 %) children on an elimination diet and 103/109 (94·5 %) controls; for avoidant eating in 138/146 (94·5 %) children on an elimination diet and 108/109 (99·1 %) controls; and for feeding problems in 137/146 (93·8 %) children on an elimination diet and 102/109 (93·6 %) controls.

There was no difference in picky eating scores between the elimination diet group (median = 31; 25th and 75th percentiles: 19 and 39) and the control group (median = 27; 25th and 75th percentiles: 19 and 35; P = 0·148). The frequency rate of picky eating was higher in children on an elimination diet (35·4 %) than that in the control group (23·3 %; P = 0·042), considering a score > 35 (75th percentile of control group) as the cut-off point.

Avoidant eating scores were also similar between the elimination diet group (median = 3; 25th and 75th percentiles: 2 and 5) and the control group (median = 3; 25th and 75th percentiles: 2 and 5; P = 0·164), as well as the frequency rates of avoidant eating (23·9 and 20·4 %, respectively, P = 0·508).

The feeding problems score was higher in the elimination diet group (median = 38; 25th and 75th percentiles: 28 and 50) than in the control group (median = 34; 25th and 75th percentiles: 24 and 48; P = 0·032). However, the frequency rates of feeding problems were similar between groups (32·1 and 28·4 %, respectively; P = 0·541).

The three instruments had high internal consistency in the analyses calculated for the whole sample (Cronbach α = 0·85, 0·80 and 0·87 for picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems, respectively).

Weight and height according to the presence of feeding difficulties

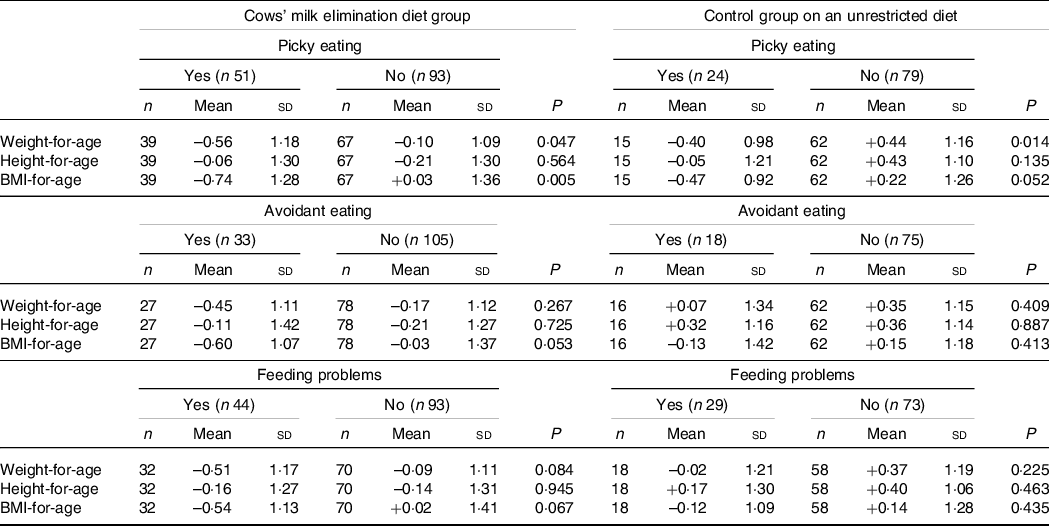

Table 2 presents the anthropometric data according to the presence of feeding difficulties in the elimination diet and control groups. Lower weight-for-age z-scores were observed in children with picky eating in both groups. BMI-for-age z-scores were lower in both groups for picky eating and in the elimination diet group for avoidant eating and feeding problems; however, statistical significance was reached only for picky eating in the elimination diet group. Height-for-age z-scores were similar in both groups independently of the presence of picky eating, avoidant eating or feeding problems.

Table 2. Anthropometric indicators for the cows’ milk elimination diet and control groups according to the presence of feeding difficulties

(Numbers; mean values and standard deviations*)

* Mean values and standard deviations, Student’s t test.

Socio-demographic, dietary and clinical characteristics associated with feeding difficulties

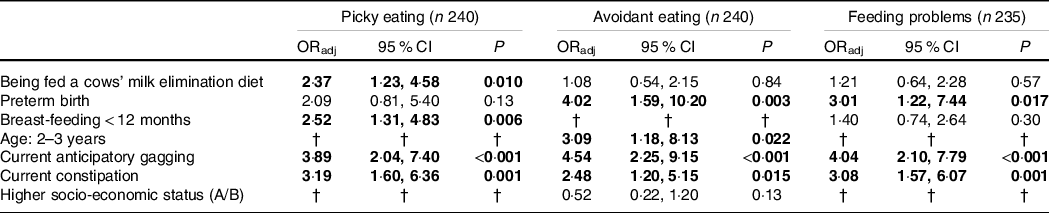

Multiple logistic regressions were performed on all children from both groups to evaluate variables associated with feeding difficulties. Being fed an elimination diet was included in the multiple regression analyses as an independent variable along with those variables in the univariate analyses with P values < 0·20 (online Supplementary Material 5). The results obtained after adjustment of the models are presented in Table 3. Being fed a cows’ milk elimination diet and breast-feeding for less than 1 year were associated only with picky eating (score > 35). Constipation and anticipatory gagging showed strong associations with the three feeding difficulties studied. Premature birth was associated with avoidant eating and feeding problems. Younger age (age 2–3 years, n 198; compared with 4–5 years, n 57) was associated with avoidant eating. Sex, socio-economic status and maternal education were not associated with any of the studied feeding difficulties.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratio evaluating the associations between feeding difficulties and socio-demographic, dietary and current clinical characteristics for the cows’ milk elimination diet and control groups*

(Adjusted odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

ORadj, adjusted odds ratio.

* Logistic regression models were performed with data from the whole sample to investigate associations of each feeding difficulty with the children’s characteristics. OR were estimated from these equations. Being fed an elimination diet was included in all models, regardless of having a P value < 0·20 in the univariate analyses. Variables highlighted in bold were associated (P < 0·05) with picky eating, avoidant eating or feeding problems in the final models.

† Variable not included in the regression model as presented a P value ≥ 0·20 in the univariate analysis (online Supplementary Material 5).

Previous clinical manifestations and elimination diet characteristics associated with feeding difficulties in children on a cows’ milk elimination diet

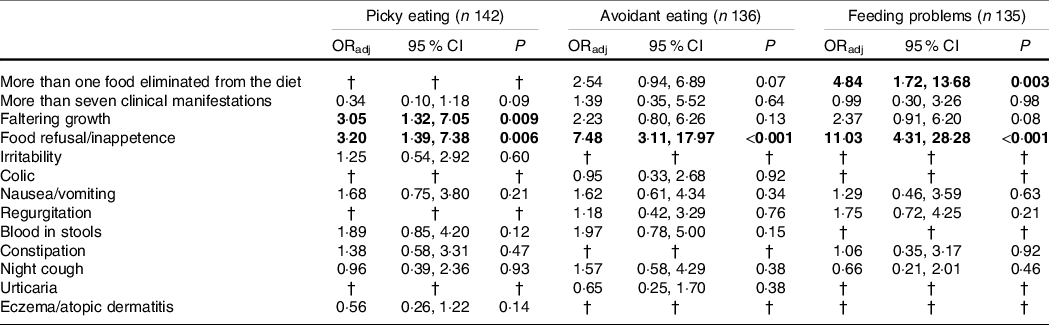

In the elimination diet group, the past clinical manifestations present before starting the elimination diet and current diet characteristics that exhibited P < 0·20 in the univariate analyses (online Supplementary Material 6) were included in the multiple regression models as independent variables. The multiple regression analyses are shown in Table 4. Past food refusal/inappetence was strongly associated with the three feeding difficulties studied. Past faltering growth was associated with picky eating. Elimination of more than one food from the diet was associated with feeding problems. Other variables included in the multiple regression analyses (number of clinical manifestations and past occurrence of other clinical manifestations) were not associated with any of the studied feeding difficulties.

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratio evaluating the associations between feeding difficulties and past clinical manifestations of food allergy (present before starting the elimination diet) and current elimination diet characteristics for the cows’ milk elimination diet group*

(Adjusted odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

ORadj, adjusted odds ratio.

* Logistic regression models were performed with data from the elimination diet group to investigate associations of each feeding difficulty with current dietary characteristics and past CMPA clinical manifestations. OR were estimated from these equations. Variables highlighted in bold were associated (P < 0·05) with picky eating, avoidant eating or feeding problems in the final models.

† Variable not included in the regression model as presented a P value ≥ 0·20 in the univariate analysis (online Supplementary Material 5).

Discussion

Picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems were found in 20–35 % of children, which is in accordance with data from literature(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11). Picky eating frequency and feeding problems scores were higher in the children on an elimination diet. Food refusal and/or inappetence as clinical manifestations of food allergy were associated with feeding difficulties. Children with picky eating from both groups presented lower values of weight-for-age z-scores. The three investigated feeding difficulties were associated with current constipation and anticipatory gagging in both groups.

In the paediatric population, there is a great variability in the prevalence of feeding difficulties, which may be due to differences in the diagnostic criteria(Reference Taylor, Wernimont and Northstone21,Reference Taylor and Emmett36–Reference Cole, An and Lee40) . On the other hand, there are few articles concerning feeding difficulties in children fed a cows’ milk elimination diet due to CMPA. One study evaluated avoidant eating(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15) and the other searched for picky eating and feeding problems using the Montreal Scale(Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16). Therefore, we decided to study the same feeding difficulties with the same questionnaires. The first was a retrospective non-controlled study held in a tertiary centre in London that showed avoidant eating in 40 % of children aged 1 month to 13 years with gastrointestinal allergies(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15). In our study, avoidant eating was found in 23·9 % of the children on an elimination diet and in 20·4 % of the control group. The second study was conducted on the Isle of Wight and evaluated picky eating and feeding problems in children aged 8–30 months fed a cows’ milk elimination diet, compared with a group on an unrestricted diet. Children on an elimination diet presented higher scores of picky eating, while in our study higher frequency (35·4 % v. 23·3 %, P = 0·042) but similar scores were observed. Taking feeding problems into account, in the Isle of Wight the frequency rates found were 13·6 % in the elimination diet group and 1·6 % in the control group(Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16). In our study, there was no statistical difference between the rates of feeding problems (32·1 and 28·4 %, respectively, in the elimination diet and control groups). However, in both studies the scores were higher in the children fed an elimination diet. The relation between feeding difficulties and a cows’ milk elimination diet was also addressed by multivariate analyses (Table 3). A statistically significant positive association was found between being fed a cow’s milk elimination diet and picky eating, but not with avoidant eating and feeding problems. Even though an association between elimination diet and feeding problems was not found, the children on an elimination diet scored higher for feeding problems than those of the control group. Therefore, our results confirm that children on an elimination diet are at greater risk of feeding difficulties. Some hypotheses may support this finding. The presence of CMPA symptoms in the first year of life may promote delay in the introduction of new foods and textures and affect negatively this window of opportunity for the development of motor-oral skills(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15,Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16) . Feeding pleasure can be affected in the presence of pain or discomfort caused by symptoms, contributing for the development of feeding difficulties(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11). Additionally, multiple dietary restrictions can limit exposure to new foods, increasing the risk of feeding difficulties(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11,Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15) , as was confirmed in our study from the association between the elimination of more than one food and feeding problems (OR = 4·84; Table 4).

Concerning our control group, it must be pointed out that the frequency rates of feeding difficulties were similar to those found in studies conducted in Brazil(Reference Maranhão, Aguiar and Lira34) and in other countries(Reference Wright, Parkinson and Shipton17,Reference Benjasuwantep, Chaithirayanon and Eiamudomkan38) . However, it is important to note that, in both groups from our study, the frequency and scores of feeding problems and picky eating were higher than those found in the Isle of Wight. The lower age of the children from the British study (age range: 8–30 months; mean: 12·4 and 15·0 months) might be an explanation, since the children from our study were older (age range: 2–5 years; mean: 3·3 and 3·4 years) and the prevalence of picky eating may increase with age, with a peak by the age of 3 years(Reference Cano, Tiemeier and Van Hoeken20,Reference Taylor and Emmett36,Reference Brown, Perrin and Peterson41) . In the multivariate analysis shown in Table 3, a higher risk for avoidant eating (OR = 3·09) was found in children aged 2–3 years, compared with 4- to 5-year-old children. Although the same questionnaires were used, the comparison of the three studies should be evaluated taking into account the differences between these three case series in relation to socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Despite the heterogeneous cases and results of these three studies, it is possible to conclude that feeding difficulties are more frequent or severe in children on an elimination diet. Another recent study conducted in Turkey(Reference Ercan and Tel Adıgüzel24) evaluated preschoolers fed an unrestricted diet who were, however, fed a cows’ milk elimination diet in their first 2 years of life. These children presented, in relation to the controls, higher scores of food avoidance and satiety responsiveness, as well as higher frequency rates of children with low intake of dairy, macro and micronutrients. Supported by previous studies(Reference Maslin, Grundy and Glasbey42,Reference Mennella, Forestell and Morgan43) , these results show that the elimination diet may have effects that remain after cows’ milk is reintroduced into the diet.

The repercussions of CMPA and feeding difficulties on weight and height are an important issue. In both groups, picky eating was associated with lower values of body weight (weight- and BMI-for-age; Table 2). Only in the elimination diet group, BMI-for-age of children with avoidant eating and feeding problems showed a tendency to be lower (P-values, respectively, 0·053 and 0·067). The study from the Isle of Wight did not compare specifically the impact of feeding difficulties on the z-scores of weight and height(Reference Maslin, Dean and Arshad16). On the other hand, the study conducted in a tertiary centre in London found an association between avoidant eating and weight loss in children with gastrointestinal allergies(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15). According to recent reviews of the literature, the nutritional impact of picky eating is controversial(Reference Brown, Vander Schaaf and Cohen39,Reference Samuel, Musa-Veloso and Ho44) , but there is a subset of picky eaters at risk of poor weight gain, requiring early identification and nutritional surveillance(Reference Taylor and Emmett36). Possible causes for faltering growth in children with CMPA are: the inadequacy of the elimination diet(Reference Medeiros, Speridião and Sdepanian22,Reference Boaventura, Mendonça and Fonseca23) , higher demand of nutrients due to increased gut permeability, the inflammation and production of inflammatory cytokines and the deficiency of vitamins and minerals important for growth(Reference Meyer14), such as vitamins A and D(Reference Boaventura, Mendonça and Fonseca23). In Brazil, the special formulas for children with CMPA are usually provided by the public healthcare services only until children are 24 months old. Therefore, preschoolers can be fed with nutritionally inadequate milk substitutes(Reference Boaventura, Mendonça and Fonseca23). The nutritional care of children with feeding difficulties and CMPA is even more challenging because, besides the restrictions imposed by the elimination diet, children with feeding difficulties may refuse other foods and have a low intake of nutrients(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11,Reference Meyer14,Reference Ercan and Tel Adıgüzel24) . All these factors may compromise growth.

Concerning the comparison of anthropometric data of the two groups, children on an elimination diet had lower values of height- and weight-for-age compared with the control group (Table 1), as has been described before(Reference Vieira, Morais and Spolidoro1,Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11,Reference Meyer14,Reference Medeiros, Speridião and Sdepanian22,Reference Boaventura, Mendonça and Fonseca23) . However, the three types of feeding difficulties were not associated with lower values of height in both elimination diet and control groups (Table 2). Anyway, our data showed that children on an elimination diet are at risk of lower values of weight, especially those with feeding difficulties, confirming the hypothesis that children on an elimination diet are at greater risk of nutritional impairment(Reference Meyer14), which could be aggravated by feeding difficulties.

For the whole sample, the multivariate analysis of Table 3 also showed a strong positive association between constipation and anticipatory gagging with the three feeding difficulties studied. Constipation was also associated with avoidant eating in the study held in London(Reference Meyer, Rommel and Van Oudenhove15). Even for children on an unrestricted diet, constipation has been associated with feeding difficulties(Reference Tharner, Jansen and Kiefte-de Jong28–Reference de Oliveira, Jardim-Botelho and Morais30,Reference Taylor and Emmett36) . It is important to note that in our study, constipation was found in 21·1 and 26·9 % of the elimination diet and control groups, respectively. Such values are within the range of the literature(Reference de Oliveira, Jardim-Botelho and Morais30,Reference Koppen, Vriesman and Saps45) . In children with constipation, it is hypothesised that visceral hypersensitivity, delayed motility and chronic pain or discomfort may affect the sensory perception of food, willingness to eat, appetite and satiety, contributing to the development of feeding difficulties(Reference Chehade, Meyer and Beauregard11). Concerning anticipatory gagging, it has an important role in the diagnosis of feeding difficulties(Reference Levy, Levy and Zangen26,Reference Levine, Bachar and Tsangen27) and was present in approximately 48 and 17 % of children with and without feeding difficulties, respectively (online Supplementary Material 5). A higher frequency rate was also observed in a previous study that found anticipatory gagging in 47 % of the children with feeding difficulties, compared with 2 % in those without feeding difficulties(Reference Levine, Bachar and Tsangen27), confirming the relevance of this manifestation for the investigation of feeding difficulties.

Premature birth was also associated with avoidant eating and feeding problems independently of being fed an elimination diet (Table 3), which is in accordance with studies that identified in children born prematurely a higher risk of feeding difficulties at 2 years(Reference Johnson, Matthews and Draper46) and at 6 years of age(Reference Samara, Johnson and Lamberts47). This association may result from the neurodevelopmental and behavioural problems that might affect preterm infants, delaying feeding skill acquisition and contributing to the development of feeding difficulties(Reference Johnson, Matthews and Draper46). Furthermore, a shorter total duration of breast-feeding was associated with picky eating. Breast-feeding offers the baby the flavours of foods and beverages consumed by the mother, which can influence its food preferences and acceptance(Reference Beauchamp and Mennella48). This highlights that breast-feeding might be a protective factor against picky eating(Reference Taylor, Wernimont and Northstone21,Reference Shim, Kim and Mathai49) .

The multivariate analysis shown in Table 4 studied the relation between previous clinical manifestation of CMPA, present before starting the elimination diet, and feeding difficulties. There was a strong association of past clinical manifestations of faltering growth with picky eating (OR = 3·05) and of food refusal/inappetence with picky eating (OR = 3·20), avoidant eating (OR = 7·48) and feeding problems (OR = 11·03). These manifestations cause anxiety in parents. Inadequate feeding practices can be a consequence, which in turn may contribute to the development and/or perpetuation of feeding difficulties(Reference Levy, Levy and Zangen26).

One of the strengths of this study was the use of the Internet, which allowed for the recruitment of patients from several cities of the country. In Brazil, two of every three adults are Internet users(50). The strategy permitted the exceeding of the planned sample size with low collection cost and low demand for human resources. As far as we know, this was the first study that evaluated the frequency of feeding difficulties in children on an elimination diet outside the UK. Other strengths were the strong internal consistency of the questionnaires applied to evaluate feeding difficulties, and the recruitment of a control group.

This study has the limitations inherent to all cross-sectional studies, so it is not possible to establish a causal relationship. The CMPA diagnosis was established by the physician in charge of the assistance of each child. Therefore, the diagnosis was not always established by the same protocol. The instruments used to assess feeding difficulties were not validated in Brazil; nevertheless, most of the results are in line with previous studies. It must be emphasised that the volunteers in a pilot study did not mention difficulties in understanding the questions and the Cronbach α coefficient confirmed a strong internal consistency. As for the decision to participate in the study, there may have been a greater interest among parents of children with feeding difficulties, but this factor could be present equally in both groups, considering that the decision to participate in the study was voluntary. The assessment of the association between previous clinical manifestations of CMPA and feeding difficulties showed a strong association for faltering growth and food refusal/inappetence. Both can also be present in the history of children on an unrestricted diet, which makes them important manifestations to be investigated in future studies including healthy children. Finally, the higher maternal education level and socio-economic status in the control group might result from regular people’s greater awareness of the importance of being voluntary in research projects. It must be pointed that 84 % of the participants from the whole sample belonged to the higher Brazilian socio-economic levels (A and B). Therefore, the results of this study cannot be automatically extrapolated to the other socio-economic strata. On the other hand, our results justify future studies including participants from other geographic regions and socio-economic status.

In conclusion, children on an elimination diet had higher frequency of pick eating and higher scores of feeding problems in relation to those of the control group. Picky eating was associated with lower values of weight-for-age but not of height-for-age z-scores in both groups. The antecedent of food refusal and/or inappetence as past clinical manifestations of CMPA, before the onset of the elimination diet, were associated with an increased risk of feeding difficulties in preschool years. Constipation and anticipatory gagging at the moment of the survey stood out as clinical manifestations associated with picky eating, avoidant eating and feeding problems.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support given by Danone Nutricia for sponsoring the online platform SoGoSurvey for data collection.

This work was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (grant number 130332/2016–0). The CNPq had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

V. C. de C. R.: formulating the research questions, designing the study, carrying out the study, analysing the data, interpreting the findings, writing and reviewing the article. P. G. L. S: formulating the research questions, designing the study, analysing the data, interpreting the findings, reviewing the article. A. S.: analysing the data, interpreting the findings and reviewing the article. M. B. M.: formulating the research questions, designing the study, carrying out the study, analysing the data, interpreting the findings, writing and reviewing the article. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version to be submitted.

V. C. de C. R. reports personal fees from Danone Nutricia outside the submitted work. For the remaining authors, no conflict of interest is declared for this article.

Supplementary material

For supplementary materials referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521004165