Introduction

‘Russia is rich, fertile and powerful. What does it need to become richer, more fertile and more powerful? People’ (Von Schlözer Reference Von Schlözer1768, 120). The thesis presented by the German historian August Ludwig von Schlözer, later professor at the St Petersburg Academy of Science, became so influential that it would determine the populationist political course adopted by Russia's empress, Catherine the Great (1729–96). Through the implementation of populationist policies in the design of her imperialistic plans, Catherine II's reign is considered ‘the first, in Russia, to show systematic concern with population’ (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2008, 31), especially marked by the 1764 edict on serfdom, which sanctioned aristocratic and state monopoly over the ownership of peasants. With this edict, Russia took a socio-political course opposed to the physiocratic theory advocated by prominent intellectual figures like Alexander Golitsyn and Alexander Radischev (Letiche Reference Letiche1964). According to them, peasants’ freedom rather than constraint was of the basis for agricultural and consequently economic development. Although persecuted for their ideas, these thinkers were eventually proved right. The status of serfdom of the peasantry compelled the Russian state to look for other, free human capital to work the land and bring innovation to various fronts. As a result, foreign immigration became a key factor in the modernisation of Russia's vast, under-populated territories. The Italian migration to the northern Black Sea region is embedded within this context.

The present article focuses on the mutual interactions between the Italian migrant community and the environment in which they settled, Eastern Crimea, between the 1820s and 1920s. This period begins with a consistent and stable migration from Italy to Eastern Crimea and ends with the Bolshevik rise to power and the subsequent repatriation or escape of many Italian families. Prompted by the populationist policies developed in the late eighteenth century, which soon expanded their focus according to a mercantilist logic, the 1820s saw mainly single Genoese merchants settling in Eastern Crimea (especially the cities of Kerch and Feodosia). From the 1870s onwards, Kerch saw a larger migratory flow from Apulia, composed primarily of seamen and market gardeners.

As it was a highly mobile and fluid group in terms of identity, there are no precise estimations on the size of the Italian community in the area. However, according to diplomatic reports of the time, in the late nineteenth century the Kerch Apulian community amounted to more than 2,000 individuals, an estimate that included only people who retained Italian subjecthood. Whilst the exact numbers may not be clear, this migration holds significant qualitative value, particularly given the complexities of identity formations and transformations. This principle guides my analysis to primarily consider the micro scale through individual cases rather than statistical evaluations.

Referring to the migrant community, the word Italian is used not in a national sense but as a container term which denotes a group formed in the majority by Apulians and a minority of people from other Italian regions. It was precisely this lack of national structuring rather than population size which determined the relegation of Italian migration to the northern Black Sea region into what Anna Makolkin describes as ‘historical amnesia’ (Makolkin Reference Makolkin2004). Whilst consistently contributing to the transformations of their surroundings, it is only rare cases of toponymy which preserves a blurred memory of these people's industry. The Italians were by no means the only migrant group that creatively interacted with the region's environment. The Greeks, Germans, Armenians, Poles, French, Swiss, Estonians, who arrived in response to the 1762 and 1763 imperial manifestos inviting foreign immigrants from all over Europe (Pisarevskii Reference Pisarevskii1909) ‘to create a complete system of rural-colonial establishment’ (Klaus 1869, quoted in Bartlett Reference Bartlett2008, 56), and of course the locally mobilised Ukrainians and Russians, did it as well. However, unlike the above-mentioned groups, Italian agency has not been systematically explored.

I found part of the reason for the historiographic absence of the Italian migratory experience can be explained by the absence of Italy itself during the first 40 years of the period under consideration. However, this aspect is also valid for other migrant groups. Italian agency was characterised by a marked sense of autonomy, individuality, and versatility that, apart from hampering its crystallisation around a national feeling of belonging, allowed it to act in spite of state designs and ideology. These qualities also defined the various ways in which the community impacted the environment, intended as physical and social space. Explaining how the Italian migration to the Crimea fit within Russia's populationist policy, both pragmatically and symbolically, the article focuses on the migrants’ individual agency. This explains the introduction of particular people's cases to the narrative, as my only way into the individual dimension of their stories.

Although acknowledging the importance of ‘breaking the boundaries between bodies and nature’ (Armiero, Tucker Reference Armiero and Tucker2017, 9), in this contribution I reflect less on the migrants themselves and more on their interaction with the inhabited space, the city of Kerch and its environs. Physical space and territoriality constitute the framework without which the Italian nation, and therefore its migrant body, cannot be fully understood (Ben-Ghiat and Hom Reference Ben-Ghiat and Hom2016, 3). Therefore, I approach space in opposition to the imagined or symbolic space, where both Russian imperialism and Italian nationalism operated, including both the urban and the rural. As Donna Gabaccia observed, ‘for migrants from Italy, home was a place – the patria or paese – not a people, nation or descent group’ (Gabaccia Reference Gabaccia2003, 7). Indeed, physical space represented the first and most direct factor of interrelationship for the Italians in Kerch, embodying their primary receiver and recipient of value, identity and activity.

The Italian migrant community in Eastern Crimea, reverberating within the local highly diverse and cosmopolitan society, reproduced the tension between the transnational and the local, forming ‘webs of social connections and channels of communication between the wider world and the particular paese’ (Gabaccia Reference Gabaccia2003, 3), that informs the broader research behind this study. From an introduction on Russian imperial ideology and ‘southern migration’, of which the Italians were part, in the present contribution I look at the interaction between the migrants and the environment surrounding them, both as the experience of exceptional pioneer-like figures, and that of a collective of ordinary Apulian seamen and market gardeners.

The lack of autobiographical sources and other documents of a personal nature does not allow me to include the migrants’ direct perception of nature and the city in this study. However, the archival documentation illustrating their interaction with space reveals many aspects of their ‘environmental sensitivity’. This interaction was characterised by practices of ‘appropriation of the environment through gardening’ (Armiero, Tucker Reference Armiero and Tucker2017, 8), through the utilisation of natural resources, as well as through the management of the urban infrastructure of Kerch. Such practices aimed to recreate home in the hosting place, but were also simply the product of the migrants’ ingenuity and creativity, of their propensity to mould and transform.

Settling the south: ideologies and solo practices in Eastern Crimea

Based on concepts of heritage and antique culture, the Italian presence fits long-lasting cultural and geopolitical aspirations to which Russia fervently aspired. Eighteenth-century Russia was an Empire of the North (Wolff Reference Wolff1994) that wanted to become more South. Not a position on the globe, these geographical connotations indicated a place on the map of world civilisation. While the North was regarded as ‘barbarian’, the South stood for Greek antiquity, for the historical and the cultured. From this vision imbued with Graecophilia, that during the Enlightenment was a common ‘European obsession … on an institutional level’ (Kozelsky Reference Kozelsky2009, 43), derived also Russia's desire for a genealogical connection with antiquity and consequent geopolitical expansionistic plans southwards, to the Black and Mediterranean Seas (Zorin Reference Zorin2014).

The expansion culminated, after major military victories over the Ottoman Empire, with the annexation of Crimea in 1783. Having been part of the ancient Greek colonial network, Crimea in a sense satisfied Russia's need for South and represented a turning point in this process. Incredulity and amazement overwhelmed the Russian elite, when ‘it became possible … to familiarise oneself with ancient sites not only in the Mediterranean but also in Southern Russia’ (Tunkina Reference Tunkina, Guldager Bilde, Hojte and Stolba2006, 304). With Crimea's acquisition ‘Russia received its portion of antique heritage, which gave her the right to stand beside civilised European countries’ (Zorin Reference Zorin2004, 100). However, because Crimea was mainly inhabited by a population of Muslim nomadic Tatars, for the imperial government it was necessary to ‘polish’ and ‘domesticate’ it, to manage the Crimean steppes, actuating a major work of physical and symbolic appropriation.

‘The Russian state did not conquer the steppes by military force alone, but used a variety of methods to annexe, incorporate and subjugate parts of the region and its inhabitants’ (Moon Reference Moon2013, 11). Symbolic appropriation of space, beginning with toponymy, was one of these methods. Catherine II ordered the renaming of places from Tatar to Greek-sounding Russian words. ‘To confine and eradicate the memory of barbarians’ (Zorin Reference Zorin2004, 49), Krym was named Tauride, Akht Mechet – Simferopol’, Kafa – Feodosia, Kozlov – Eupatoria, Enikal’ – Panticapaeum, Taman’ – Fanagoria, at the site of Kherson's ancient ruins appeared as Sevastopol.’ The annihilation of Tatar presence reinforced the idea that the local Turkic population was unable to use the land, and that therefore Crimea was a sort of tabula rasa, a virgin area to be cultivated. This myth, commonly generated by colonial misrecognition of native land-management practices, was necessary to justify the empire's transformative activity on the territory. Therefore, although gardens existed also at the Tatar Khan's court, the Russian state ignored and overpowered them, declaring that the whole Crimean peninsula was to become the paradisiacal garden of the Russian Empire (Zorin Reference Zorin2014, 92–120).

Gardens served as representation of power. They communicated ‘a more perfect approximation of the king's ideals, than in his control and subjugation of people’ (Elias Reference Elias1983, 227–8). In this sense, Crimea reflected Russia's imperial greatness and Tsarist enlightenment (Masoero Reference Masoero and Rossi2015), where the garden represented ‘a sign of autocratic intervention [as well as] benevolent rule’ (Schönle Reference Schönle2007, 4). According to the Empress, ‘in the Tauride,Footnote 1 the principal task will undoubtedly be the cultivation of land [and] one of the principal objectives … could be that of gardens’ (Catherine II Reference Catherine1880, 361). For that purpose, she added, ‘competent foreign gardeners were much needed.’ Italian immigrants were perceived exactly as that: gardeners the Crimea needed, the enlightened colonists who would vehicle civilisation and modernisation into the Empire's tamed south.

Among the earliest and best-documented foreign agents of modernisation was a ‘solo pioneer’, a Genoese adventurer who eventually fell into historical oblivion, Raffaele Scassi (Rojas Gomez Reference Rojas Gomez, Guignard and Seri-Hirsch2019). Scassi arrived in the Crimea in the 1820s, similarly to the Italian settlers of North and South America, and transformed what was a ‘sterile and denuded land’ (Jones Reference Jones1827, 211) on the outskirts of Kerch into a superb and modern garden. Thanks to an ingenious draining system, ‘a canal unwinding through his plantation, [that drawing from] two or three small streams procured a good running water’ (Svinin Reference Svinin1828, 22), Scassi turned the typically dry steppe landscape of Eastern Crimea into a fertile area. To the great amazement of the local population, Scassi set up a vineyard and orchard that featured ‘the best type of trees of various type, ordered from Italy and Provence’ among which were: 1,400 grape trees from Burgundy, Côte-Rôtie and Bordeaux (Svinin Reference Svinin1828, 22), 6,000 fruit trees from southern France and 2,000 unusual species (Sanzharovets Reference Sanzharovets2015, 258) and also wild American trees, figs and Chinese trees of the mulberry family (Svinin Reference Svinin1828, 22–3).

Raffaele Scassi's contribution went far beyond land management. It proved essential in three different areas. One was the construction of an antique heritage preservation system, laying the basis for archeological research and for the institution of the Museums of Antiquities. The second was the colonisation of the northern Caucasus, though a mercantilist approach totally innovative for Russia. Finally, the third was the urban and commercial development of Kerch, thanks to the realisation of Scassi's main project, the construction of a port that was sanctioned in 1821. This last event paved the way for the second flux of migration from the Italian peninsula to Kerch 50 years later, linked to seafaring and commerce. In fact, given Kerch's position on the strait between the Black and the Azov seas, similar to Constantinople's between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, the establishment of a port and a quarantine there was greatly beneficial to the city's economy and to all commercial activities in the Sea of Azov (Vigel’ Reference Vigel’1893, 61) that, between 1830 and 1890, was Europe's main emporium for grain trade.

Moreover, with the activation of Kerch's port, Scassi envisioned the wider commercialisation of Astrakhan and Angora wool, provided by the numerous sheep flocks present both in Eastern Crimea and on the opposite shore, in Circassia. Also abundant in the waters of the Sea of Azov were sturgeons and other fish caviar ready to be commercialised. The same applied to raw materials suitable for industrial and manufactural production, coming from slate quarries, the region's many clay hills, ochre mines, sulphuric waters, and the salt pans abundant in Kerch's environs. The activation of commerce, with respect to export and import goods from the Mediterranean region, stimulated considerable cabotage activity (Scassi Reference Scassi1821, 2–3) that would be especially important for the arrival and settlement of the Apulian seamen and market gardeners in Kerch, as mentioned above. Raffaele Scassi's activity was therefore central to the urbanisation of Kerch, the city which tormented governor Filip Vigel’ with its barbaric monotony, emptiness and solitude (Vigel’ Reference Vigel’1893, 56–7). Scassi understood that the activation of commerce ‘will stabilise [in Kerch] an industrious population’ (Scassi Reference Scassi1821, 2), which would continue to shape it and its environs in the decades to come.

In the following years Crimea continued to attract similar solo migrants who creatively interacted with the environment. One of these agents’ footprints reached 20 kilometres north-east from Kerch, to the village of Kurortnoe, where there is a mud lake that in the summer becomes pink. Its name is Chokrak, from the Tatar language ‘spring’, ‘source’. Every year, even today, it attracts thousands of people, thanks to the healing properties of its mud, which were discovered in the 1880s by Franz Semenovich (Francesco, son of Simone) Tommasini, among the richest Italian merchants in nineteenth-century Kerch. He designed a Chokrak healing centre, overruling the local authorities who wanted to gain jurisdiction and control over it. The dispute emerges from Tommasini's correspondence with the two main conflicting political parties, represented by the respective governors of the Tauride and the Kerch-Enikale administrative units, who eventually lost the battle.Footnote 2 Tommasini was able to further develop his enterprise, exploiting and spreading knowledge about this Eastern Crimean natural resource, similarly to Iosif (Giuseppe) Bianchi, a Genoese merchant, market gardener and political figure, 20 years later, in the nearby city of Feodosia.

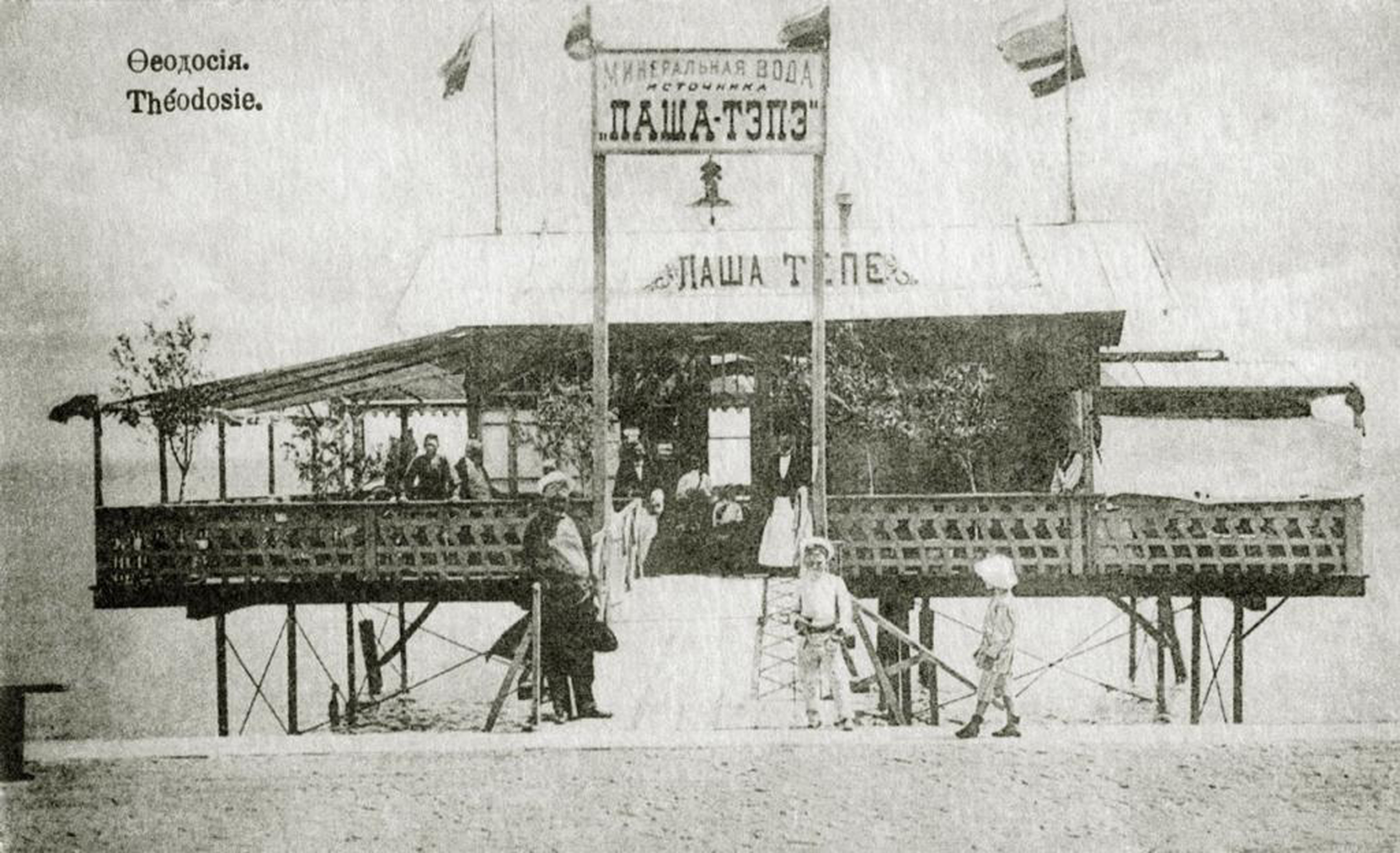

Drilling the land to improve the watering of his vineyards, on the southern slope of the Lysaia mound (from the Russian for ‘bald mound’), at a depth of 64 metres, Bianchi discovered a water with an unusual smell and taste. Analyses carried out by the Odessa Chemical Laboratory confirmed it was a mineral water. The water had a sodium chloride content close to the famous Essentuki 20 water and a sodium carbonate content equal to the Austrian mineral water Obersalzbrun of Kronen Quelle spring (Bogdanov Reference Bogdanov1960, 5). Convinced of the waters’ qualities, in 1906 Bianchi set up its industrial extraction, calling the spring Pasha Tepe, from the Tatar words for ‘great peak’. A floating shop on Feodosia's embankment was organised for the sale of the water (Figure 1) and with it, Bianchi initiated one of Crimea's most long-lasting commercial activities. The Pasha Tepe mineral water gained success in the Caucasus and finally in Europe where, in 1916, it won the gold medal at the international fair in the city of Spa, Belgium. The water was renamed ‘Feodosiiskaia’ (Feodosian) in 1929, when the city's brewery renewed its production. In Crimean sanatoria, pump-rooms with the Pasha Tepe mineral water were organised and are still used today to treat various ailments, such as diseases of the liver and bile duct, chronic colitis, kidney disease, and gout (Kokhanovich Reference Kokhanovich1964, 88–89).

Figure 1. ‘Mineral water from the spring Pasha Tepe’ on Feodosia's embankment. https://www.crimeantatars.club/history/just-fact/pasha-tepe-krymskaya-mineralnaya-voda pokorivshaya-belgiyu

Like Raffaele Scassi and Franz Tommasini, Iosif Bianchi gave his contribution as land-manager and entrepreneur, paving the way to a different approach of bio-valorisation of the local territory's resources. This approach, originating in Italian experience, met the ambitions and designs of the Imperial Russian government for Crimea. Whilst the lack of sources may make these characters appear as solo agents, this should not imply that their work lacked synchrony. It is in fact important to acknowledge the interactions of the Italians with the other migrant groups and autochthonous people, in the making of Eastern Crimea. Such interaction does not overshadow, but rather acknowledges, the Italians’ creative application of their environmental know-how to the hosting territory, and its transformative power. Their ‘failure’ in being remembered in time is in fact a confirmation of their amalgamation into the place's history, almost as organic material that eventually decays into the earth. Retrieving their individual stories is important not only to restore their agency, but also to appreciate the history of that ‘romance’ between men and nature, across and regardless of national borders, that contributed to a continuous flow of human knowledge about space, place and nature.

Scassi, Tommasini and Bianchi belonged to a migration flow of merchants, all single men and mainly from Genoa, that was linked to grain trade and adventurism: Donna Gabaccia (Reference Gabaccia2003) identifies these as the carriers of civiltà italiana abroad. Their stories allow exploration into the ‘individual part’ of the Italian interaction with Eastern Crimea's environment, along with the stories of many more migrants who, as autonomous men of culture, populated the shores of the Russian Black Sea since the early nineteenth century (Varvartsev Reference Varvartsev1994) without shaping an Italian national diaspora (Clementi Reference Clementi, Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2002). Only in the 1870s, with the arrival of a group of Apulians in Kerch, the concept of Crimean Italians appeared and incorporated all previous Italian migrants in the region. Aspects of their collective identity and footprint are discussed in the following section.

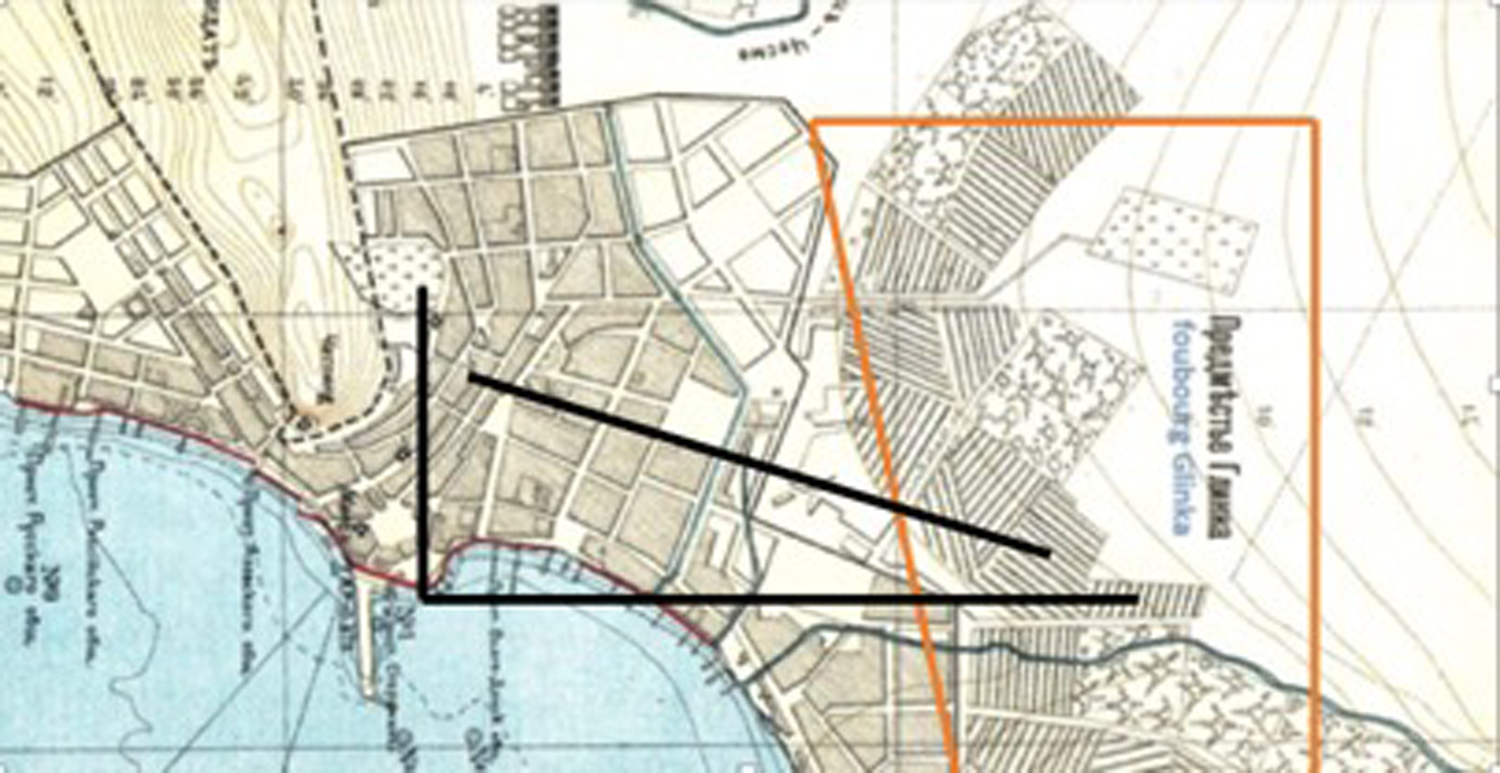

Trani-Kerch: a brief environmental rationale of a migration

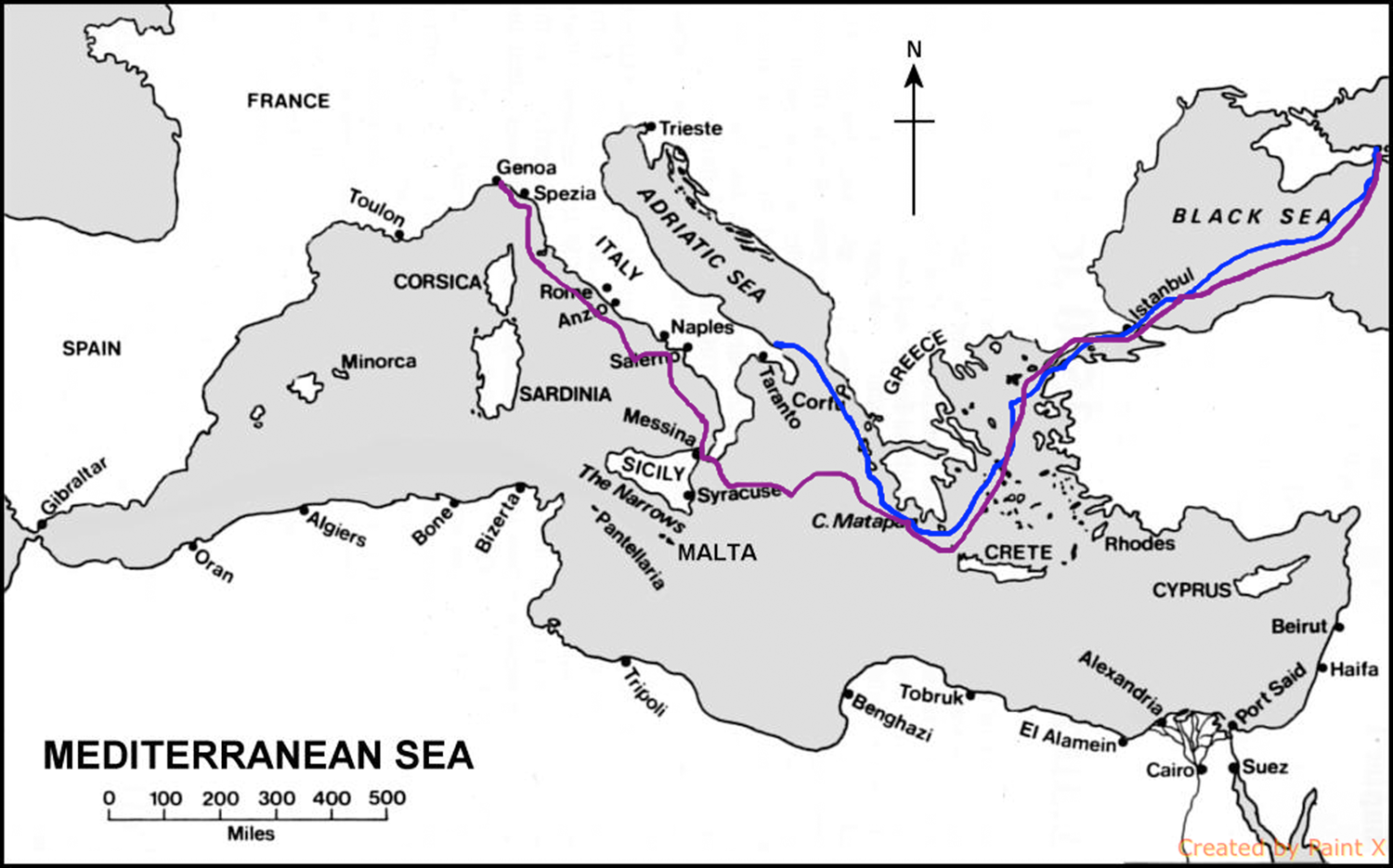

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the community of Italians in Kerch constituted nearly 70 per cent of Italian speakers in the Russian Empire2 and amounted to about 2,000 individuals.Footnote 3 Although not a large population in comparison to other migrant and minority groups in the same region, it was a qualitatively significant one to the extent that the Italian government was compelled to consider and treat it as a ‘national colony’. This community was composed in its majority by migrants from the Apulian Adriatic coast, specifically from Terra di Bari, primarily employed in coastal navigation (cabotage) as fishermen, sailors or ship owners, secondarily in horticulture.Footnote 4 Fewer members of the community were originally from Genoa and Tuscany but merged with their southern countrymen via intermarriage or simply through professional partnerships linked to maritime activity (see the two main migrant trajectories in Figure 2). The Apulian core, on which the community built its collective identity, was the only socially cohesive group of Italians in Russia. It did not fully assimilate with the local population as Italians in Russia normally did (Clementi Reference Clementi, Bevilacqua, De Clementi and Franzina2002) but retained features of its cultural (including linguistic) baggage for almost a century (Shyshmarev Reference Shyshmarev1975).

Figure 2. Map of the two above-mentioned flows of Italian migration to the northern Black Sea region in the nineteenth century: the blue line shows the Genoese merchants’ itinerary (1820s), and the red one the Apulian seamen's route (1870s).

Collectively, the Italians in Eastern Crimea contributed to the development of activities including horticulture, dock works, the fish industry, and the management and exploitation of natural resources. Just as they had an impact on the hosting environment, socio-economic and environmental factors had had an impact on them and on their decision to migrate. Following the core's migratory itinerary, I trace their path back to the port cities of Trani and Bisceglie, which were historically the Apulian cities with the highest concentration of emigrants (Assante Reference Assante1978). In Apulia, as in all Italy's southern regions, the disintegration of the Bourbons’ kingdom brought about a long period of crisis. Within the new Italian state, in the late 1870s, these mainly agricultural regions also faced troubles linked to a general European agrarian crisis that eventually hit Italy (Zamagni Reference Zamagni1993, 62), causing a slump in the price of wheat and agricultural products.

Apulia was severely affected by this crisis, especially in its northern internal area of the Tavoliere,Footnote 5 where wheat had been extensively cultivated since 1865. This situation eventually produced masses of landless peasants who, along with labourers, fled in great numbers (Snowden Reference Snowden1986, 62). However, the migratory movement did not start among the peasant population of the Tavoliere, but in the Adriatic coastal area, the marina, precisely from the cities of Trani, Bisceglie and Molfetta (Snowden Reference Snowden1986, 13). Here, the cultivation of commercial crops such as grapes, olives, almonds, and vegetables, usually grown by small peasant cultivators, was also intensive (Assante Reference Assante1978, 318). Characterising this migrant group, Franca Assante writes that it was made up of mainly poor people, almost entirely from Trani, and farmers and workers employed in small industries and commerce, largely from Bisceglie (1978, 318). The emigrant sailors, mostly natives of Trani, were compelled to seek their fortune away from home because of the depreciation of ship rental in the 1870s and 1880s and the blow inflicted to maritime transportation by the construction of railways.

With its still fragile economic system, united Italy could not offer a place to all its new citizens, forcing many to emigrate. In contrast to the classic destinations chosen by most, such as North and South America, the tranese and biscegliese chose a well-known sea route, leading to the Black Sea shores of the Russian Empire. The reason for this seemingly unusual choice was the commercial connection established between the two places in the late eighteenth century. In fact, in Apulia, once considered ‘the Netherlands of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies’ (Sirago Reference Sirago2004, 102), the ports of Trani, Bisceglie and Molfetta were particularly active and growing centres for the trade of oil, wine and wheat, especially with Genoa, France, Germany, Holland and Russia (Sirago Reference Sirago2004, 107). Since 1826, Trani had even hosted a deputy-consul for commercial affairs with Russia.Footnote 6

The special connection between Apulia and the Russian south was stimulated in particular by the wheat trade, which engaged the local mercantile class. One prominent example was the Pavoncelli family, led by the young entrepreneur and wheat merchant Giuseppe Pavoncelli. Among the most powerful Apulian landlords, Pavoncelli rapidly edged out rival Genoese merchants in the region's market and made his fortune during the Crimean War, when he won a contract to supply the British, French and Sardinian armies with wheat (Di Rienzo Reference Di Rienzo2012). However, despite this success, this trade never grew into a national economic activity under the flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Whilst offering a vibrant maritime life, the vessels used by the marina people continued to be the small allibbi suitable for cabotage and for transporting goods onto bigger ships. For this reason, maritime trade from the Apulian Adriatic coast was practised mainly on foreign vessels (Giura Reference Giura1967) on which seamen found employment. These circumstances, along with the established sea networks, eventually promoted and eased migration for many inhabitants of Trani and Bisceglie to Crimea.

Although we have been speaking of a primarily maritime population, migrating from Apulia to Kerch, a study conducted in the 1930s by the Soviet linguist Vladimir Shyshmarev revealed the rural nature of this group. Shyshmarev's work, primarily a study in dialectology, revealed a wider analysis of the Romanic people and their languages in the southern regions of the Soviet Union (along the Pontic littoral and in the Caucasus). Shyshmarev was interested in the remnants of a southern Italian dialect, the biscegliese, which, according to his findings, had mingled interestingly with the Russian language in Kerch and its environs. In parallel with his dialectological study, Shyshmarev also carried out historical and ethnographic research of the target Apulian population, in which he observed a rare case of rural Italians established in Russia (Shyshmarev Reference Shyshmarev1975).

The definition of ‘rural Italians’ seems imprecise and opens a discussion that helps to define a group identity for Kerch Apulians. The designation ‘rural Italians’ is limited by a binary understanding of environment as either natural or urban. By integrating nature into urban settings, Italian migrants around the globe break this dichotomy. For Italian migrants, agricultural activities like fruit and vegetable farming were not an exclusively rural prerogative. In fact, practices of urban horticulture were also exported by migrants across the Atlantic Ocean during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries where, as Gilberto Mazzoli (Reference Mazzoli2019) noted, ‘portable nature was a form of resilience and adaptation to the new environment’, or a recipient of memory and Italian-specific spatial knowledge (Inguanti Reference Inguanti and Sciorra2011).

Although with differences, the same situation applied to the Apulians who arrived in Kerch in the 1870s. They were in fact all registered as burghers (meschane), both when they settled around the port quarantine area, in the city centre, and on the outskirts of Kerch, in a garden area named Glinka. While the first group was mainly occupied in maritime activities, the second group was indeed primarily engaged in horticulture. In his research, Shyshmarev focused on the latter because, by the 1930s, most of the Apulian seamen had left the Soviet Union, mainly during the Russian Civil War (1918–20), or had ultimately merged with the local population. In so doing, Shyshmarev missed the complexity of the urban-rural dichotomy characterising the Kerch Italians.

Through Shyshmarev's observations, and Franca Assante's descriptions and further research of civil registry data, it emerges that there was a clear-cut occupational distinction between the families from Trani, primarily of sailors, and those from Bisceglie, active mainly in the horticultural and agricultural sector. Analysing the data available for the period 1850–1920, I noted that biscegliese surnames Dell'Olio, De Pasquale, De Piero, Di Pinto and Giannuzzo always appear in combination with vegetable and fruit farming, while others, like De Benedetto, De Martino, Fabiano are always linked to seafaring. As Donna Gabaccia wrote, to fully understand the Italian migrant groups, it is necessary to see them as ‘many temporary and changing diasporas’ (Gabaccia Reference Gabaccia2003, 6), profoundly connected to ‘face-to-face communities of family, neighbourhood or native town’ (3).

Thanks to a focus down in scale, performing a micro-analysis, it is possible to see that the social structure of the very close-by, and yet distinct, places of origin of the migrants was exported and reproduced in the even smaller community of Kerch. Indeed, along with professional came social differentiation. Most Italians active in the agricultural and horticultural sector were less wealthy than those employed in maritime work. Acknowledging this internal diversity allows a better presentation and evaluation of the multiple impacts that Italians had on Kerch and of the way they inscribed themselves in the hosting environment. Outlining it briefly, one could define the rural impact as more silent and less visible, while the urban impact was more documented and accessible. Mapping Italian presence on the space of their settlement reveals an over-representation of the maritime community and an under-representation of the market gardeners.

Kerch and the Italian factor

Italian presence in Kerch is mapped between 1851 and 1941, to provide a cross-temporal view of the community's geo-distribution in the city.Footnote 7 I consider and compare four time-spans of about 20 years each: 1853–79, 1880–99, 1900–19 and 1920–41. The first and last dates were determined by the available archival records on Italian households in Kerch.Footnote 8 The legend of Figure 3 below indicates that each symbol on the map represents a different time-span, corresponding to a different geo-distribution pattern. For the years 1853–79, only some data could be retrieved about the Italians’ location in Kerch and its environs. In that period, although according to archival records 223 Italians checked in at Kerch's port, only two of them indicated a residence address within the city's urban area. Those were the 38-year-old seaman Mauro Scagliarino, domiciled in Karantinnoe Road, and 46-year-old seaman Giuseppe Galante, hosted at the merchant Kislanov's house in Remeslennaia Street. Their choice, or necessity, to inhabit the port quarantine was directly linked to their maritime profession.

Figure 3. Approximate geo-distribution of Italian households in Kerch, 1853–1941. Author's elaboration.

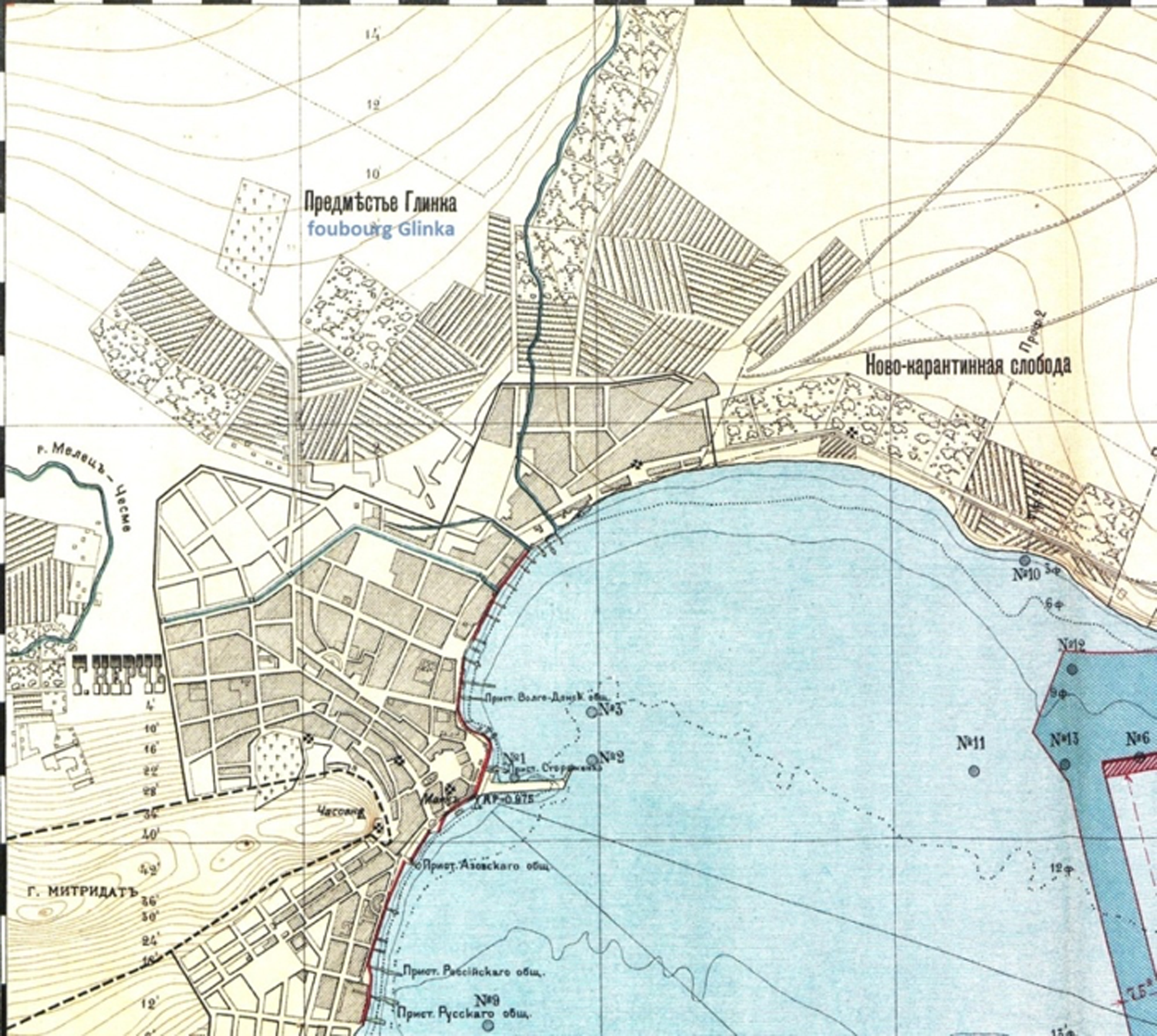

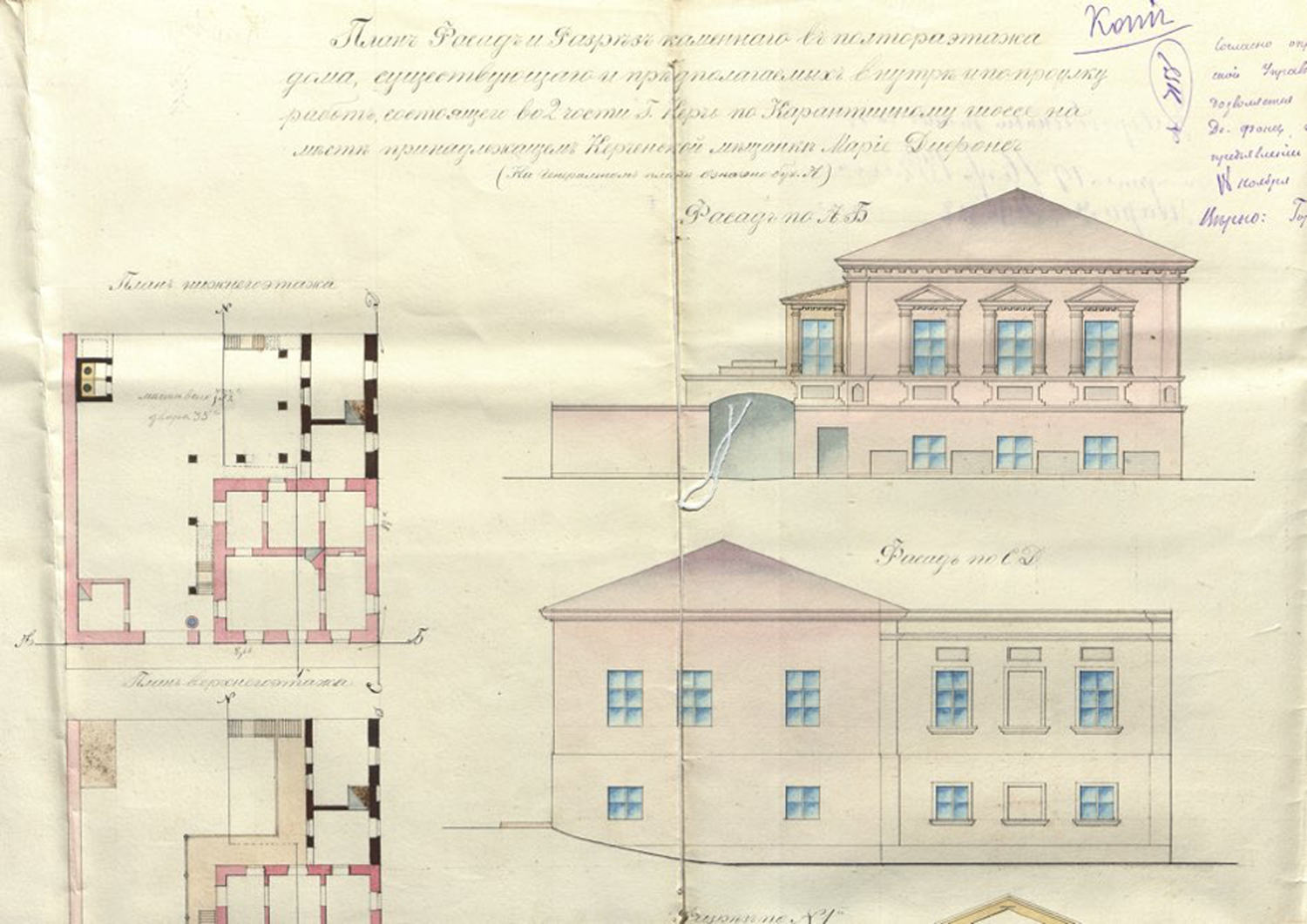

During the period 1880–99 the situation changes (Figure 4). Not only is there more data available, but the geo-distribution pattern reveals a new area of Italian settlement further from the sea: Glinische or Glinka. As suggested by the word itself, from the Russian glina (clay), this area corresponds to a fertile territory in the north-east outskirts of the city, that was used, and still is today, for vegetable and fruit farming. This area was therefore characterised by a large number of urban gardens of various sizes, both independent and adjacent to houses. The last option was the most commonly chosen among Italian market gardeners. Since their settlement, the Apulian fruit and vegetable farmers contributed to the shape of the cityscape and the city's soil in a way displayed in Figure 5 below, where the striped and spotted squares indicate respectively vegetable plots and fruit gardens.

Figure 4. Approximate geo-distribution of Italian households in Kerch, 1880–99.

Figure 5. Detail of ‘Plan of Kerch's port, in the surveys of 1893–1896’ by V. Ju Rummel, 1896. St Petersburg: Technic auto-lithographist engineers Dobroumov, De Kelsh.

A wider Italian presence in Glinka is registered at the beginning of the twentieth century (Figure 6). From the total Italian households registered between 1800 and 1899, 35 per cent were located there. In the following 20-year period, 1900–19, this percentage rises to 47 per cent. In the late 1920s, in the Egorovo village area, directly north of Glinka, a collective Soviet farm (kolkhoz) called ‘Sacco and Vanzetti’ was organised by Soviet authorities, local Italian political activists and Italian political immigrants, mainly re-directed to Kerch from Moscow, who constituted in Kerch a new Italian ‘diasporic’ group (see Dundovich, Gori and Guercetti Reference Dundovich, Gori, Guercetti, Dundovich, Gori and Guercetti2004). The Italian political émigrés acted according to Soviet directives: therefore, in terms of environmental impact, their contribution does not overcome the official state framework and is almost entirely linked to the kolkhoz land management.

Figure 6. Approximate geo-distribution of Italian households in Kerch in 1900–19.

Because of its marked national component, the kolkhoz was locally known as ‘Italian’ (Baranov Reference Baranov1935, 262). Its production was mainly horticultural and developed in a garden area of 70 hectares, of which one was planted with vines. It was the major producer of vegetables in Eastern Crimea and a significant grain grower. In 1933, the farmers’ collective salary per working day consisted of 4,314 kg of wheat and 18 kg of vegetables (Baranov Reference Baranov1935, 262).

In the years between the two world wars, we can observe a sharp change in the Italian geo-distribution pattern (Figure 7). Between 1920 and 1941 the Italian community moves from two separate clusters localised in the Quarantine area and in Glinka, to settlements scattered across the whole urban area, covering almost every quarter: today's city centre, Kerch port, Avtovokzal, Gor'kogo-Gagarina, Steklotarnyi and Abissinka, along with adjacent Egorovo village. As the Italian community scattered, references to Italian politics were inscribed into Kerch's suburban setting by the creation of two commemorational places. One was the above-mentioned Sacco and Vanzetti kolkhoz, named after two anarchists and migrant Italian workers, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti who, in Massachusetts, USA, had been controversially convicted for murder and sentenced to death in 1927. The other was the quarter Abissinka, from the Russian for ‘little Abyssinia’, that celebrated the Ethiopian victory over Italy. The Russian imperial authorities had supported Menelik II against Italian colonialism (Rupprecht Reference Rupprecht2018), and the Soviet state continued this policy. There is no direct evidence to prove that the inclusion of Italian political references into urban semiotics was prompted by the presence of a local Italian community, even one of political émigrés. However, it is noteworthy that the interaction between the environment and its migrant population was matched by the production of relevant meaning.

Figure 7. Approximate geo-distribution of Italian households in Kerch in 1920–41.

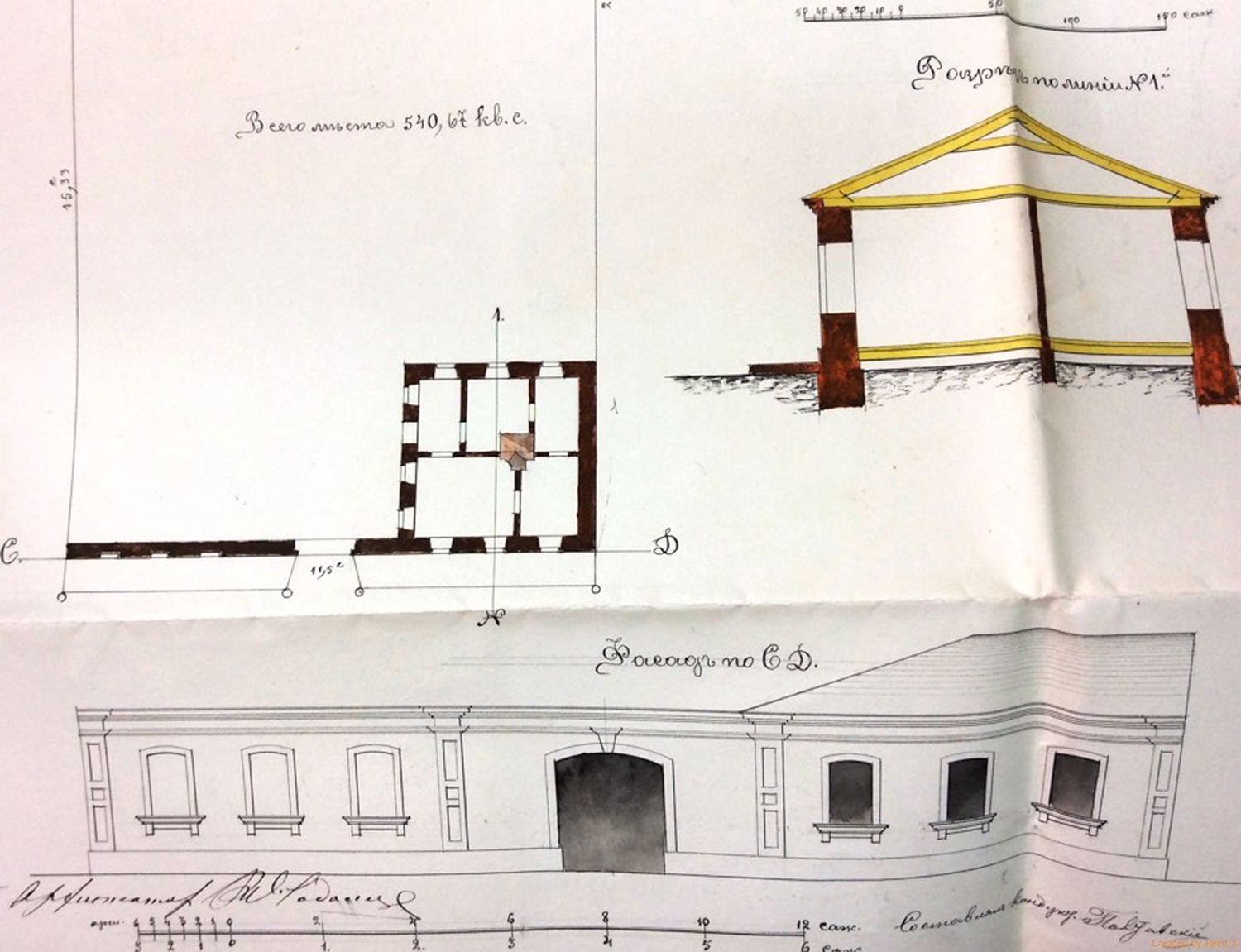

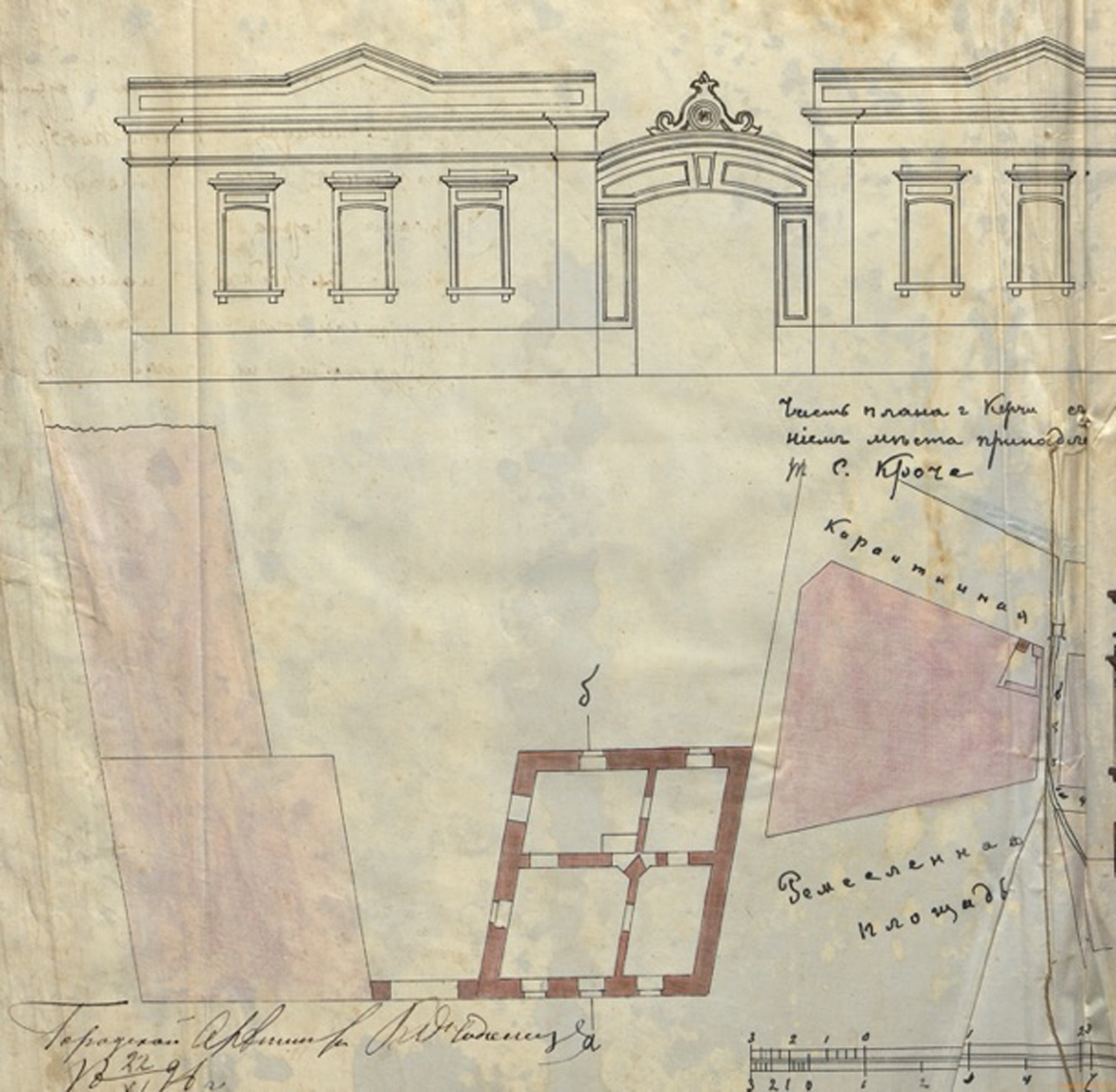

Zooming into the garden quarter of Kerch, spatial transformation becomes visible also on an architectural level. The micro-environment of the Apulian migrant families in Glinka was shaped by a delimited area with a plot and a house, usually a simple one-storey construction made of stone,Footnote 9 as in the case of Giovannina Scagliarino (see Figure 8). Located on the road to Adzhimushkai, her house was defined as a ‘hut’ (khata) in its architectural plan and had an estimated value of 100 roubles. This value can be considered low, as the average value of Italian estates in Kerch was 1,100 rubles. The plan, however, reveals a quite elaborate façade forming the access to the garden. In the top right-hand corner of the full plan, a coloured sketch corresponds to the section along the line N-1 of the plan. In the area below, a detailed drawing illustrates the entrance façade, correspondent to line C-D of the plan. The remaining empty rectangular area of the plan corresponds to the garden, whose size was 540.67 square sazhen’, approximately 1,080 square metres.

Figure 8. Plan of G. Scagliarino's house, 1887. GAARK, f. 455, op. 1, d. 2033, ll. 1,3

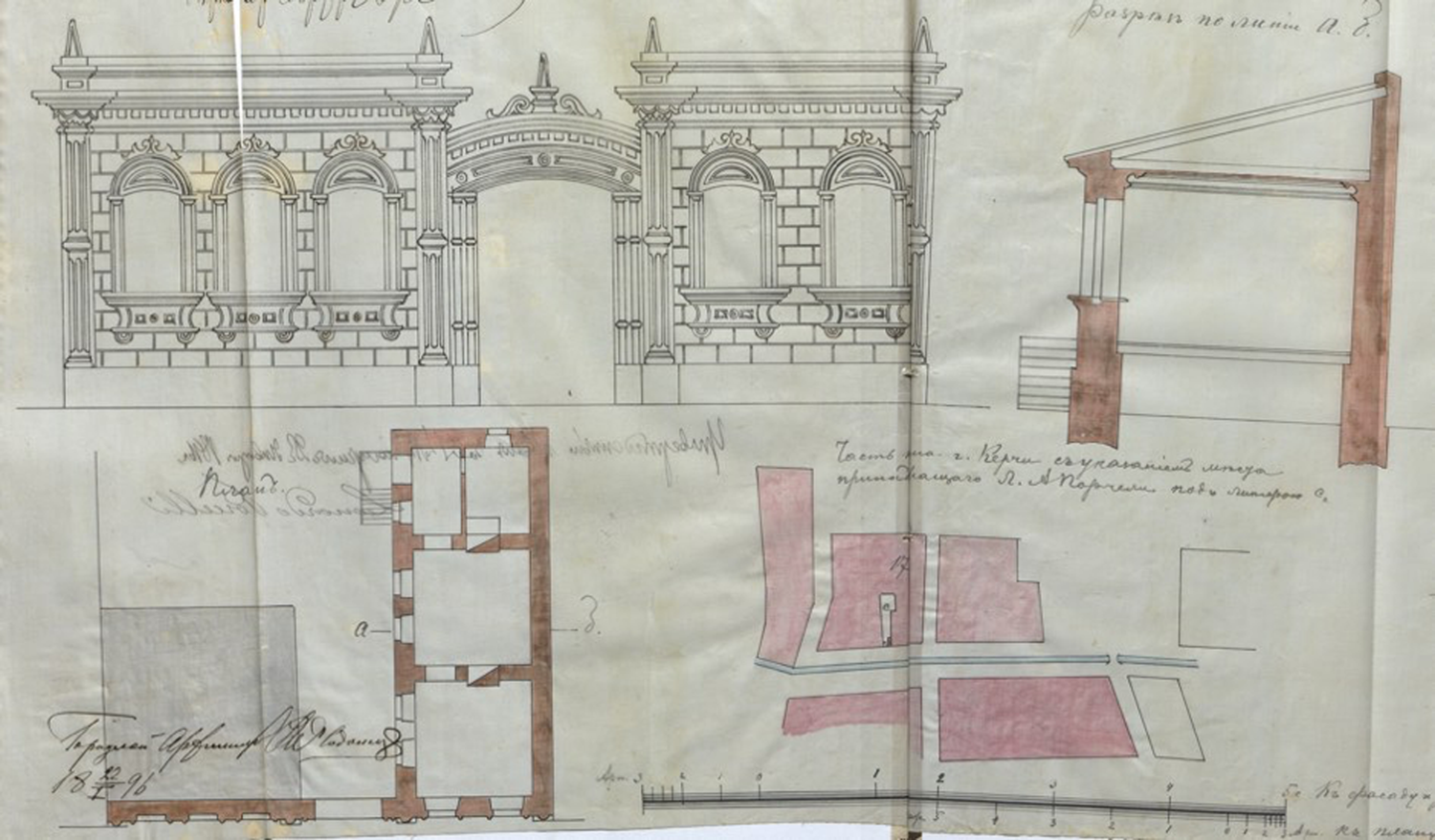

The size and structure of each of the Italian houses in Glinka was similar, although the architectonic details varied, usually according to the wealth of the landowner. For example, Alessandro De Martino's house on Second Bulganakskaia Street was also a one-storey building of stone, but the façade appears more elaborate, thanks to the introduction of decorative elements: two columns at the sides of the gate and circular details below the windows. Much finer buildings were those of the inhabitants in the urban centre, in the port and quarantine area of Kerch. They feature more decorative elements, visible especially on faҫades. A comparison between the house of Alessandro de Martino in Glinka and those of Croce, Di Fonso and Porcelli in the quarantine area (see Figures 9, 10, 11, 12), suggests a degree of social disparity among the members of the Italian community in Kerch, which is confirmed by the data available on the values of Italian estates across the city.Footnote 10

Figure 9. Plan of De Martino's house, 1887. GAARK, f. 455, op. 1, d. 4429, ll. 2ob., 3

Figure 10. Plan of Croce's house, 1887. GAARK, f. 455, op. 1, d. 5263, ll. 4, 13, 16.

Figure 11. Plan of Porcelli's house, 1887. GAARK, f. 455, op. 1, d. 4430, ll. 2ob, 3

Figure 12. Plan of Di Fonso's house, 1887. GAARK, f. 455, op. 1, d. 1213, ll. 5ob., 6

The richest Italian family in Kerch in the 1880s were the Tommasini, whose estate in the city's noble and wealthier quarter (Vorontsov, Stroganov and Dvorianskaia Streets) had a total value of up to 86 000 rubles. Aside from their exceptional wealth, the average range of Italian assets was estimated at between 700 and 1,500 roubles. Italians typically lived in the port and quarantine area, mainly around Shosseinaia Street, along the coastal line north of Kerch city centre proper. They owned houses, annexes, shops and even taverns, like the Patruno: women also appear as owners, including Felice Fabiano's wife, Rosalia De Martino, Maria Defonso and Maria Scagliarino, whilst there is no evidence of female owners in Glinka. These data lead us to the conclusion that, in Italian Kerch's geography, the further we go from the sea, the lower the wealth level becomes.

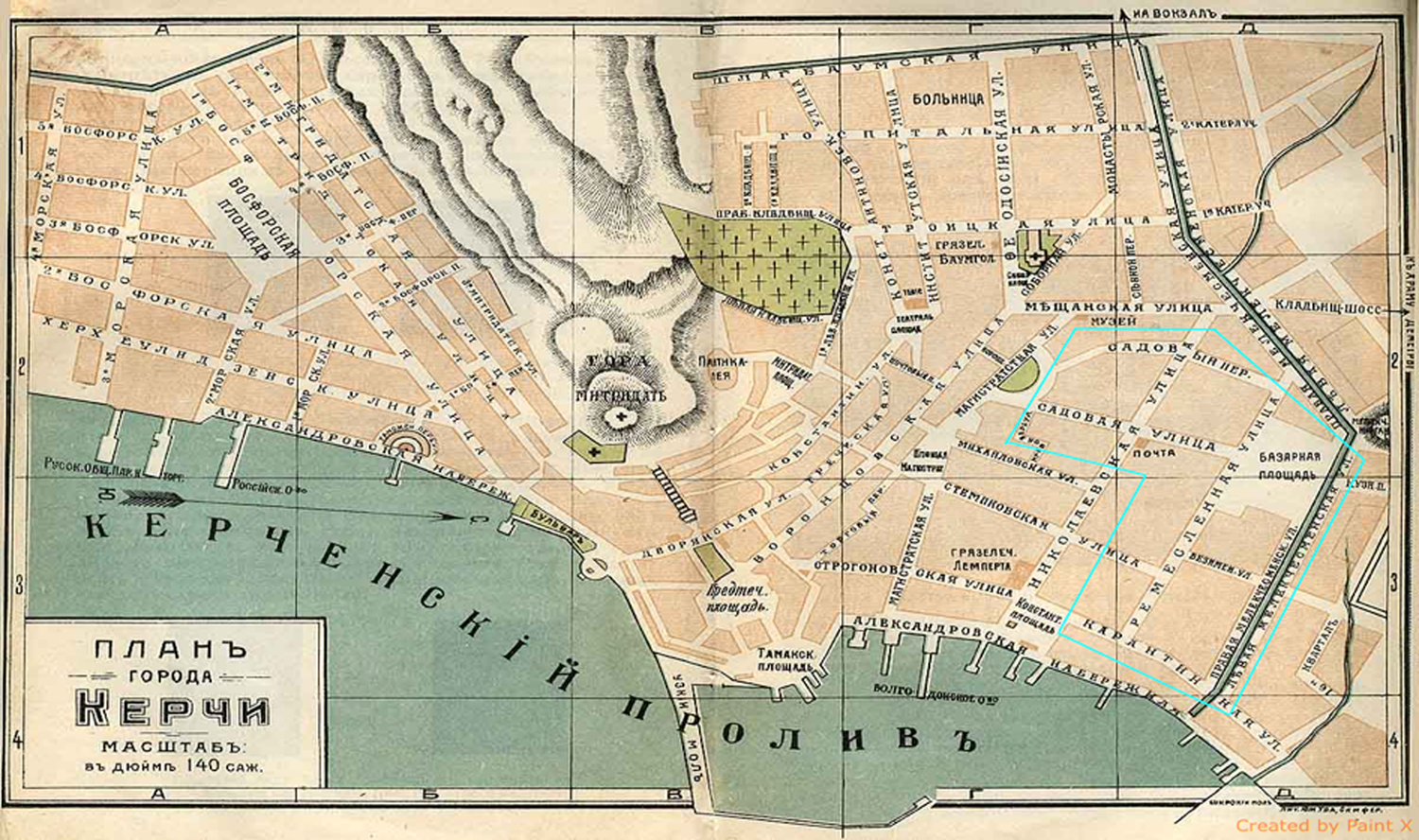

The port and quarantine quarter registered the highest concentration of Italian-owned estate, as shown by the geo-distribution maps presented earlier, from the 1870s to the 1940s. It constituted the core and the social centre of the community, as well as a focal point of better documented Italian activity, which impacted both the physical and the social dimension of Kerch in its modernisation process. The map in Figure 13 shows Kerch's urban centre in 1914. Within it, is the port and quarantine quarter in the lower right-hand corner, where the Italians’ settlement area is highlighted, delimited by the market square, Levaia Melekchesmenskaia Street to the east, Karantinnaia Street to the south, Magistratskaia Street to the west and Sadovyi Alley to the north.

Figure 13. Kerch city centre, 1914. Lithography by the Southern Association, scale 1: 100 000. From Crimea: A Guide, edited by K. Bumberg, L. Vagin and N. Klepinin, Simferopol, 1914. http://www.retromap.ru/show_map.html?mcode=14191420

As in Glinka, the Italian community in this quarter was physically compact, because the Apulian seamen families tended to settle next to each other. This phenomenon emerges from the land-granting documents, providing evidence that the collocation of the Italians’ houses was not casual or imposed but intentionally requested. Between 1900 and 1904, on Remeslennaia Square, the families Pergolo, Croce, Maffione, De Pierro and Giacchetti were granted almost equal plots, in some cases acquired from previous non-Italian owners, to finally occupy a common area beside Kerch's port.

On 7 August 1900, the widowed Teresa Pergolo requested one plot in the 15th quarter, the Quarantine, facing Remeslennaia Square.Footnote 11 There, on 28 September of the same year, Donato Maurovich Croce would also be granted a plot of 203.4 sazhen’, approximately 607 square metres (see Figure 14). Immediately next to Croce, Maffione acquired a plot of equal size. In November, Iosif Markovich De Pierro, an Italian subject, was also applying for a similar plot of land on Remeslennaia Square, between Gnezdilovich's and Weisberg's plots. We learn from later documents that on A. Giacchetti succeeded Gnezdilovich in 1917, thus making the sequence of plots on Remeslennaia Square almost totally Apulian-owned.

Figure 14. Kerch's urban centre in 1914. Lithography by the Southern Association, Simferopol’. From Krym, Putevoditel’, edited by K. Bumberg, L. Vagin and N. Kelpinin. Simferopol’: 1927.

The intention of occupying the same physical space shows how the Apulians, like many Italian migrants across the globe, constituted a distinct body in the local space, based on the existence and maintenance of close social networks (Moretti Reference Moretti1999). Their internal cohesion was not so much based on a nationality principle but rather on their constant interaction and interdependence. After the individual contribution of Raffaele Scassi, other contributions to the transformation of Kerch are to be understood as a product of this interdependence, as collective endeavours. The gardening activity was one example that eventually resulted in the creation of an Italian kolkhoz. On the other hand, the development of cabotage in the area was imported directly by the local Apulian and Greek migrant communities (Vigel’ Reference Vigel’1893).

Another major contribution that shaped the port area, essential for the port's smooth functioning, was conceived and conducted by a partnership between Italian immigrants: the dock for the lifting and fixing of ships on Konstantinovskaia Square. The idea was conceived, realised and managed by Matteo Tarabocchio, a former Hapsburg subject, with Pantaleo Porcelli (from Apulia) and Maria Kufudaki (a Russian subject of Greek descent). From the documents it emerges that they did not own but rented the space of the dock for the city of Kerch to practise their profession, ship fixing. Their petition to the city administration explains:

On the shore in front of the Kufudakis’ house, right beside the wide jetty, there is a dock on which we have been working for the past 20 years. On this dock, we have installed all the necessary equipment and infrastructure: every year we spend large sums (a few hundred roubles) both on the maintenance of the shore and on the deepening of the seabedaround the dock.Footnote 12

In 1913, a time of escalating crisis and instability, they had the dock's usufruct rights cancelled by the municipality, which rented it to another person (Ivan Kirkhadzhi). This unexpected event shook the port's ecosystem and provoked general protest from local maritime circles. The two partners, Tarabocchio and Porcelli, wrote a petition protesting against the new dispositions of the Kerch municipality and a compromise was finally achieved for a rental regime of single exploitation. However, they soon became victims of a dramatic inflation of dock rentals, dictated by the crisis of the First World War. In October 1916, an 18-month rental cost 1,000 roubles;Footnote 13 on June 1917, it was raised to 5,000 roubles, while the next year, it reached 90,000 roubles. In a final attempt to oppose these new conditions, and supported by the local maritime élite, Tarabocchio began a legal battle against the city administration.Footnote 14The role of the Italians’ dock enterprise proved to be crucial for the economy of the whole city:

… given Kerch's position, on the crossroads between two seas, it is essential to have the infrastructure for the pulling and lifting of ships because Mariupol's floating dock serves Novorossiisk and Rostov's is overloaded with work; bеsides, the presence of a dock in Kerch helps the city administration in its struggle against unemployment … The impossibility of fixing the ships wrecked in June …, that would have been lifted at Kerch dock, obliged the shipowners to turn to Genichesk, in this way depriving Kerch's workers of salaries [totalling] about half million roubles […]. (Council of Kerch port operations, 1919)Footnote 15

Notwithstanding the aknowledgement of their work's importace, Tarabocchio and Porcelli were ultimately overpowered by the state machine and obliged to shut down their enterprise. The same fate would be soon shared by the rest of the business- and land-owning population, with the establishment of the Bolshevik regime in Crimea, in 1921. Nevertheless, the Italian contribution to the (trans)formation of the local environment via land-management and structural adjustments in Eastern Crimea, endured.

Conclusion

Until the Bolshevik revolution and the subsequent civil war (1918–21), Italians had inhabitated and substantially influenced Eastern Crimea from various perspectives: rural and urban, infrastructural and commercial, individually and collectively. They could do so quite freely thanks to the initial adoption of policies, by the Russian state, that promoted immigration and immigrant contribution to the local territory's ‘modernisation’. With the consolidation of the Soviet regime, possibilities of individually and spontaneously moulding the space were significantly restricted and eventually the Italians, along with other national minorities, were totally cut off from these processes. Being largely a land-, estate- and assets-owning group, many Italians were first accused of social treason, of being enemies of the Soviet state and kulaks (Vignoli Reference Vignoli2012, 39–82). With the deterioration of Soviet-Italian relations after 1935, many more Italians (even including political émigrés) became victims of the Soviet conspiracy-paranoia, therefore of the Stalinist terror and the Great Purge in 1936–8, mainly accused of espionage for Fascist Italy (Fabre Reference Fabre1990). Finally, during the Second World War, the Italian community of Kerch suffered its most tragic blow: in January 1942 they were deported to Kazakhstan and confined to rural areas of ‘special settlement’, where they lost their civil rights and were exposed to the harshest conditions (Giacchetti-Boico Reference Giacchetti-Boico2016). This episode, a turning point in their identity history, decimated the community and marked the end of their Crimean life for many decades to come.

Regardless of their deportation and later dispersal across the wide geography of the USSR, the impact of the Italian contribution to Kerch's environment in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is still visible today. In fact, beneath the faҫade of the enormous Soviet transformation of space, often disregarding the peculiarities of places and the fragility of the ecosystems, the Italian micro-footprint was able to adapt and stimulate further change for its own preservation. Fruit gardens and vegetable plots still serve Kerch's internal economy; the port has greatly expanded, as have maritime traffic and commercial exchages. Local natural amenities, such as Feodosiiskaia mineral water and the Chokrak mud lake, still constitute a lively part of Eastern Crimea's economy. The Italian community's contribution to these processes is today almost entirely ignored, but this is the point: ‘Italian loyalties developed more from love for a place than identity with people’ (Gabaccia Reference Gabaccia2003, 33), so it is the place, and not Italianness, that we are eventually left with.