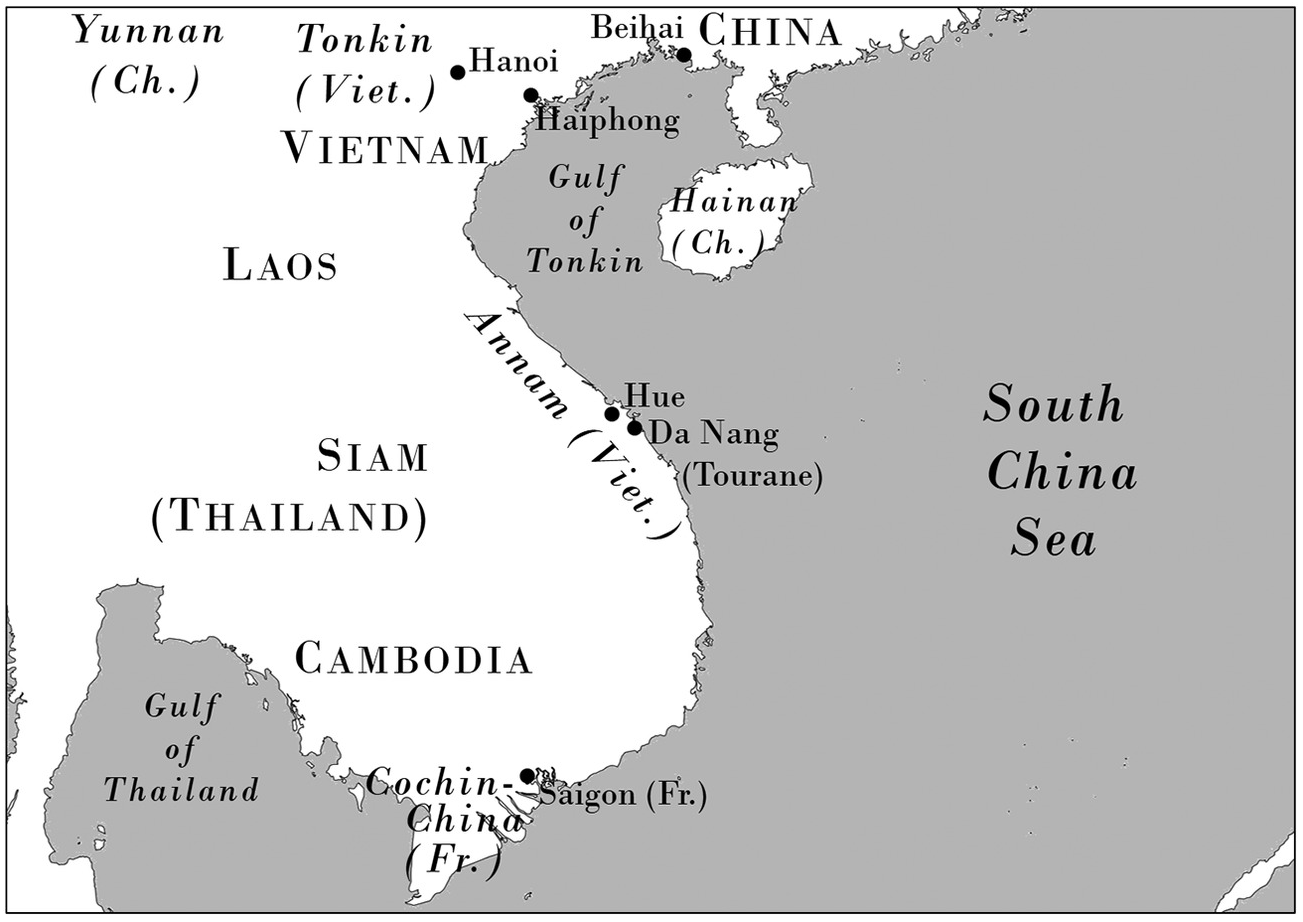

Just like the Sulu Sea and the Strait of Malacca, the coast and waters off present-day Vietnam have a long history of piratical activity. Maritime raiding was an important part of the political dynamic of Champa, a loosely integrated kingdom of largely independent polities in central and southern Vietnam between the second and seventeenth centuries, and maritime raiding played a similar role in Champa as in the Malay world. Much of the raiding was aimed at capturing slaves, and it was both a means of waging war and an important source of social, economic and political power for the Cham rulers.Footnote 1

In addition to Cham raiders, freebooters from northern Vietnam also frequently harassed the commercial traffic between Vietnam and southern China in precolonial times. Many of the pirates who throughout history raided the coasts of China originated from Vietnam, and, conversely, many Chinese raiders were active in Vietnamese waters. The European maritime influence, by contrast, was limited for much of the early modern period, and it was not until the second half of the eighteenth century that the increased maritime trade in East and Southeast Asia and the influx of European firearms began more directly to stimulate piratical activity in Vietnamese waters.Footnote 2

Chinese, Vietnamese and French Pirates

Toward the end of the eighteenth century maritime raiding surged in Vietnamese and southern Chinese waters as a result of the political instability in Vietnam. In 1771 the Tay Son Rebellion, a popular uprising that led to the fall of the ruling Le Dynasty, broke out. Within a few years the Tay Son leaders had gained control over most of the country and set about to redistribute land and to eliminate official corruption. Meanwhile, opposition against the Tay Son was led by the Nguyen family, who, aided by Siamese and Chinese troops, struggled for three decades to overthrow the rebels.Footnote 3

Map 4: Indochina

In order to enhance their military capacity, the Tay Son leaders enlisted the support of maritime mercenaries, mainly of Chinese origin. In European sources these mercenaries were usually called ‘Chinese pirates’, but arguably they were more akin to what Europeans called privateers. The Tay Son provided the Chinese raiders with official recognition, land bases and markets in exchange for military and financial support. This accommodation led to the development of a plunder-based economy in which Chinese raiders constituted the backbone of the Tay Son’s maritime forces and contributed substantially to the revenues of the regime. Under the protection of the Tay Son, the raiding bands thus thrived and grew in size and strength. After the rebellion collapsed in 1802 the raiders lost their official support but continued to engage in piratical activities, and the vast fleets were still for several years a formidable maritime force in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Tonkin.Footnote 4

The Chinese and Vietnamese authorities, aided by British and Portuguese bounty hunters, tried for several years during the first decade of the nineteenth century in vain to defeat the pirates. In 1809, however, a series of defeats spelled the beginning of the end for the raiders, and over the next couple of years the Qing authorities, through a double strategy of coercion and appeasement, and aided by internal dissension among the pirate bands, managed more or less to end large-scale piratical activity in Chinese waters. With the restoration of peace and the consolidation of the Nguyen Dynasty in Vietnam, moreover, the bands were deprived of their markets and safe havens. The result was that for close to fifty years, until the middle of the nineteenth century, the Gulf of Tonkin and most of the Vietnamese coast were relatively free from organised piratical activity, even though petty coastal depredations continued to occur.Footnote 5

During the Tay Son Rebellion, the French interests also increased in Vietnam. Although contacts between France and Vietnam dated back to the seventeenth century, it was only after a French missionary, Pierre-Joseph-Georges Pigneau de Béhaine, assisted the Nguyen Dynasty in defeating the Tay Son that a more permanent French presence in the form of Catholic missions was established in the country. Once in power, however, the conservative Nguyen Dynasty proved mostly hostile to the French missionaries’ attempts to spread Christianity. After 1820 the Nguyen emperors pursued a vehemently anti-Christian policy and tried to hinder the expansion of European interests in East and Southeast Asia. Several officially sanctioned waves of persecution of Christians took place, for example in the 1830s and 1850s, which led the French Navy to intervene in order to protect the French missions.Footnote 6

Toward the middle of the nineteenth century piratical activity began to increase in Vietnamese waters after the relative calm following the defeat of the Chinese bands that had supported the Tay Son. Again the perpetrators were mainly Chinese, and the reasons were the same as those that led to the outbreak of junk piracy in the Strait of Malacca and in the vicinity of Singapore around the same time, that is, the end of the Opium War and the decline of the Qing Dynasty in China. The increased China trade in the aftermath of the war also combined with the corruption and inefficiency of the British authorities in Hong Kong to create favourable conditions for piracy in the South China Sea. Moreover, as we have seen, arms and munitions were readily available in the British free ports of Hong Kong and Singapore, where many of the heavily armed pirate junks that roamed the South China Sea were fitted out. The situation was further exacerbated by the disorder that resulted from the Taiping Rebellion after the middle of the century.Footnote 7

The Nguyen Dynasty, weakened by internal dissension and French incursions, had limited means at their disposal by which to secure their coasts and river deltas in the face of the depredations. In 1850, a French missionary stationed in Tonkin, Monsignor Retord, reported that the whole coast of Tonkin and Cochinchina was infested by pirates organised in fleets that each numbered between fifty and sixty small boats (barques). These fleets consisted of both large and heavily armed boats that were used for attacks and smaller vessels that carried women and children and were used for the transportation of pillaged goods. Fortunately, according to Retord, two British steamers arrived to search for the pirates and destroyed or sank over sixty pirate vessels, killing and drowning many people.Footnote 8

After the departure of the British steamers, however, the surviving pirates began to reunite and recommenced their exploits. Over the following years the situation deteriorated, and in 1852 another French missionary stationed in Tonkin, Abbé Taillandier, reported that the pirates conducted horrible ravages, attacking local merchants and even vessels belonging to the Vietnamese emperor. At the same time, moreover, bands of Chinese and Vietnamese brigands were growing in strength in the northern parts of the country, where the imperial forces were unable to control the territory.Footnote 9

There are relatively few surviving firsthand accounts of the attacks by Chinese pirates in the South China Sea in the 1850s. An exception is the account by a French woman, Fanny Loviot, who experienced an attack at sea in 1854 and later published a book about her experiences. There she vividly described the night attack on the Caldera, on which she was a passenger:

Three junks, each manned by thirty or forty ruffians, surrounded the ‘Caldera’. These creatures seemed like demons, born of the tempest, and bent upon completing our destruction. Having boarded the ‘Caldera’ by means of grappling-hooks, they were now dancing an infernal dance upon deck, and uttering cries which sounded like nothing human. The smashing of the glass awoke our whole crew, and the light which we had taken for a fire at sea was occasioned by the bursting of fiery balls which they cast on deck to frighten us. Calculating upon this method of alarming their victims, they attack vessels chiefly in the night, and seldom meet with any resistance … They were dressed like all other Chinese, except that they wore scarlet turbans on their heads, and round their waists broad leather belts garnished with knives and pistols. In addition to this, each man carried in his hand a naked sword.Footnote 10

Loviot survived the attack and her captivity among the pirates, apparently without being physically abused or harmed. She was rescued, quite undramatically, along with the rest of the Caldera’s crew by a British steamer less than a fortnight after the attack. Many other victims were less fortunate, however, and it was feared that Europeans were especially susceptible to being killed in order for the pirates to avoid persecution or revenge by the colonial authorities.Footnote 11

The missionary testimonies about the surge in piracy in Vietnamese waters around the middle of the century are corroborated by reports in the colonial press. For example, in 1855 the Pok Heng, a junk from Hylam, Johor, carrying livestock, salt, fish, rice, lard, eggs, oil and tamarinds, with eighteen passengers and thirteen crew members on board, was attacked and hijacked by Chinese pirates off the coast of Cochinchina. The junk landed in Singapore a few days later, apparently still in the hands of the pirates. The ship was identified by the nakoda (captain) and some members of the original crew, who had escaped the attack by jumping into the water and swimming ashore. According to the Straits Times:

They left Anam on the 6th day of the 2nd Moon and on the 17th day when abreast of Chin Sey, on the coast of Cochin China, a Junk came up to them having on board about 40 Macao Chinese; they went close along side, threw stink pots and boarded the Hylam Junk; and being well armed, they commenced an attack upon the crew. The mate and three of the passengers were killed and thrown overboard, all the others jumped overboard. Seven of the crew succeeded in reaching the shore by clinging to a large plank which fell from the Pirate vessel, but what became of the rest is not known: the attack was made within a very short distance of the shore, and the whole of the rest must have perished or those that reached the shore must have seen something of them.Footnote 12

The attack largely followed the pattern of the junk piracy in the waters around Singapore at the same time. The pirates seem to have operated all along the western rim of the South China Sea, from Hainan to Singapore, and, as we have seen, their depredations brought about a sharp decline in the volume of the junk trade between Singapore and Cochinchina in the 1850s.

To the French, however, the piratical activity was of less importance than the persecution of French missionaries in Vietnam. The French Navy was charged with the task of protecting them, but it was in a weak position to do so. In 1840 an attempt was made to strengthen French sea power in East Asia through the creation of the Naval Division of the Chinese Seas (Division navale des mers de Chine), but the capacity of the division was limited, and France still lacked a permanent naval base in East Asia. Consequently, and because of the naval hegemony of the Royal Navy, any action that the French might contemplate in Asia depended on the consent of the British.Footnote 13

Following an abortive move in 1845 to gain a foothold in the southern Philippines, French interests in Southeast Asia shifted decisively toward Cochinchina (southern Vietnam), which was seen as a possible target for French colonisation.Footnote 14 The increasing trade with China after the end of the Opium War in 1842 and the Treaty of Whampoa in 1844, which opened up the Chinese market to French commercial interests, fuelled calls in France for the establishment of a colony in East or Southeast Asia as a means of supporting French commercial activities. The Chamber of Commerce in Marseilles presented a vision of Saigon as a French Singapore in the region, and an official Commission for Cochinchina was established in 1857, charged with the task of drawing up a blueprint for strengthening the French colonial presence in southern Vietnam. The purpose was to ensure that France kept up with Britain and other colonial powers in the race for political and economic advantage in Asia.Footnote 15

In the 1850s pressure from commercial and Catholic groups in France thus combined with the interests of the Navy to push the balance toward a more interventionist policy in Indochina. The French naval engagement in Asia was also part of a broader effort to strengthen the French Navy and to transform it into a powerful marine force with a global reach. This was achieved through a series of major naval building programmes around the mid nineteenth century, which turned the French Navy into a modern navy comparable, at least numerically, to the British.Footnote 16

Before the last years of the 1850s French expansion in Vietnam was subordinated to the efforts to advance French interests in China. Consequently, to the extent that piracy is mentioned in the reports and correspondence of the French Navy in East Asia around the mid nineteenth century, it refers mainly to the situation in and around the coasts of China.Footnote 17 The main task of the French Navy in Indochina was instead the protection of the Catholic missions, and for these purposes French warships visited Vietnam on several occasions during the 1840s and 1850s. Even though the persecutions continued, the demonstrations of French military supremacy had a deterrent effect on the anti-Christian campaigns of the Vietnamese regime.Footnote 18 In contrast to the British, thus, the gunboats of the French Division of the Chinese Seas did not prioritise the suppression of piracy in Vietnamese waters.Footnote 19

The difference in priorities and concerns between the French and the British was linked to the difference in commercial interests and the extent to which maritime security was seen as an important objective in itself. Whereas Britain had strong commercial interests in Asia that depended on the security of trade and navigation at sea – not only for British vessels but also for the local traders who were crucial for the commercial success of the Straits Settlements − there were few immediate reasons for the French to uphold maritime security in Indochina. With no permanent base in the region and relatively small commercial interests, the major aim of French naval operations in Vietnam before the end of the 1850s was instead to put pressure on the Nguyen regime to guarantee the security of the Catholic missionaries in the country.Footnote 20

As for the Nguyen Dynasty, their capacity for and interest in the suppression of piracy were limited. In the first decades of the nineteenth century the suppression of piracy, particularly with regard to the supporters of the Tay Son, had been an important objective of the new dynasty. Its first emperors gave high priority to the country’s marine forces, which probably consisted of close to a thousand armed vessels of different sizes. After the South China Sea had been cleared of pirates, however, there seemed to be little reason for the Vietnamese government to maintain a large standing navy, and as a result the naval capacity of Vietnam deteriorated quickly after the 1820s. By the middle of the century the Vietnamese government no longer had the capacity to suppress piracy and maritime raiding around its coasts.Footnote 21

From the point of view of the Nguyen Dynasty the main security threats were not the ravages of the Chinese pirates on the Vietnamese coast, but, on the one hand, internal rebellions on land, mainly in the north, and, on the other the European – particularly the French – incursions on the coasts. Several French naval visits to Vietnam in the 1840s resulted in tense standoffs and at times in violence, such as in April 1847, when the French sank five European-style vessels and about one hundred junks belonging to the Vietnamese Marine in the Bay of Da Nang (Tourane).Footnote 22 The event obviously contributed further to a decline in naval capacity on the part of the Vietnamese authorities.

The Nguyen Dynasty consistently rejected French invitations to establish diplomatic relations and tried, often unceremoniously, to curb French attempts to increase their influence in the country. For example, ahead of a French embassy to Da Nang in 1856, Emperor Tu Duc (r. 1847−83) issued a memorandum to his senior officials in which he ordered the French to be denied any official honours. In accordance with the memorandum, a French request that a letter be delivered to the emperor was refused under humiliating circumstances. The French Navy retaliated by attacking and capturing the fort at Da Nang but was forced to withdraw after a month without having succeeded in forcing the Vietnamese into submission. The withdrawal was seen as a major victory by the Vietnamese, and as the French departed, they displayed large signs that echoed the words of Emperor Tu Duc ahead of the French visit: ‘The French bark like dogs and flee like goats.’Footnote 23 The emperor also accused the French of piracy, saying that the French ‘roam the seas like pirates, establishing their lair on deserted islands, or hide on the coasts, in the depth of valleys, and from there foment troubles and revolutions in the neighbouring countries’.Footnote 24

The persecution of Christian missionaries and converts intensified after the debacle at Da Nang, and Monsignor Retord now urged the French government to abandon such half-measures that, according to him, only aggravated the plight of the missionaries. France, Retord argued, should either intervene decisively or leave the missionaries in Vietnam to their unhappy fate.Footnote 25

The trigger for a more decisive French intervention occurred in mid 1857, when the Vietnamese authorities had a Spanish Dominican missionary decapitated. The French government ordered Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly to lead a major naval expedition to Cochinchina in order to seek redress and to establish favourable conditions for French interests in the country. In a letter to the Minister for the Marine, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alexandre Colonna-Walewski, specifically emphasised two grievances of the French in Vietnam: the persecution of French missionaries and the constant refusal of the Vietnamese government to establish relations of friendship and commerce. Rigault de Genouilly’s instructions were broad: he was to occupy Da Nang, but he was then given the mandate to decide, in view of the situation, whether to establish a French protectorate over Cochinchina or to negotiate a treaty with the Vietnamese.Footnote 26 Piracy, on the other hand, was not mentioned in the instructions or in the official letters preceding the expedition, despite the prevalence of junk piracy in the region at the time. The French expedition in 1858 was thus not charged with the task of combatting piracy and seems not to have undertaken any such operations.

French troops again seized the fort at Da Nang in August 1858, but Rigault de Genouilly was unable to achieve either of the objectives of establishing a protectorate or negotiating a treaty with Vietnam. The admiral then decided to attack Saigon, which, in contrast to the Vietnamese capital, Hue, was within reach of French naval forces. The renewed war in China, however, forced the French to abort the intervention and sail for China in March 1860.Footnote 27 Once again, the Vietnamese celebrated what they saw as a victory over the French, and in a widely published decree issued shortly after the French departure, Tu Duc gave his opinion of the French: ‘Pirates, equally incompetent and cowardly, they were defeated by our valiant soldiers and saved themselves like dogs with their tails between their legs.’Footnote 28

Describing his enemies as pirates (and dogs) obviously served the rhetorical purposes for the Nguyen Dynasty, but in view of the French incursions and acts of aggression in the preceding years it was not an unreasonable accusation. The attacks on Da Nang and Saigon in 1858–60 reinforced the Vietnamese perception that the French were sea bandits or rebels rather than lawful enemies. Similar accusations were later repeated in appeals to resistance against the French after their invasion of Tonkin in 1883.Footnote 29 The notion that European navigators were pirates had a long history in Asia, dating back, as we have seen, to the onset of European maritime expansion in Asia in the sixteenth century. Against that background, the characterisation of the French as pirates probably made more than just rhetorical sense in Vietnam around the middle of the nineteenth century.

Colonial Expansion and River Piracy in Cochinchina

The Vietnamese triumph after the French evacuation of Da Nang turned out to be short-lived. Following the signing of the peace treaty with China in October 1860, French warships returned to Vietnam. Saigon was captured in early 1861, and French gunboats began to penetrate the river system of Cochinchina. The imperial troops were pushed back, and the Nguyen Dynasty, which also was under pressure from unrest in the north, was forced to negotiate with the French. In June 1862 the Treaty of Saigon was signed on terms that were highly unfavourable to the Vietnamese. Vietnam was forced to cede three of her southern provinces to France, which came to form the colony of French Cochinchina, and to give up her nominal sovereignty (shared with Siam) over Cambodia. The treaty also opened up three Vietnamese ports to French and Spanish commercial interests, and granted freedom of navigation for all French vessels, including warships, on the Mekong and its tributaries. This provision was important to the French because they hoped that the Mekong would provide direct access to the interior of China, a prospect that seemed to hold great commercial potential. The treaty also gave all French, Spanish and Vietnamese subjects the right to practise the Christian faith in Vietnam and set a large indemnity to be paid by Vietnam over ten years. In contrast to the treaties made by other colonial powers in Southeast Asia at the time, however, the Saigon Treaty did not mention any obligation on the French or the Vietnamese to cooperate in the suppression of piracy. The only mention of piracy in the treaty was in Article 9, according to which the two countries promised to extradite to the other country all ‘brigands, pirates or trouble makers’ who caused mischief in one territory and then escaped to the other.Footnote 30

The first governor of French Cochinchina, Admiral Louis-Adolphe Bonard, initially tried to implement a system of indirect rule, according to which low-ranking Vietnamese officials and village heads were to continue to exercise local authority, supervised by French inspectors. The scheme was difficult to implement, however, because most of the mandarins who were the backbone of the civil administration in Vietnam chose to leave Cochinchina as the French took over power. In order to fill their places, inspectors and other high-ranking officials in the colony were recruited among the officers of the French Navy. However, most naval officers had no experience of civil administration, and virtually none of them had any deeper knowledge about or understanding of region’s culture or language. The only interpreters available were the missionaries and their students, some of whom knew a bit of Latin. French administration of indigenous affairs in Cochinchina was thus often conducted in Latin during the first years of the colonial period.Footnote 31

The colonial administration tried to downplay the security problems in the new colony, and piracy was described as a matter of minor concern. An official report in early 1863 optimistically claimed that piracy, the ‘scourge of the Far East’, probably still existed in some parts of the colony, but that it would not be able to resist long the energy of the French marines, who penetrated all rivers and creeks with their small gunboats in pursuit of the pirates. ‘The destruction of these bandits can thus no longer be but a matter of perseverance’, the report claimed.Footnote 32 Another report, published a few years later in the official journal of the Ministry for the Marine and the Colonies, praised the stable, patriarchal social system of Vietnamese society and concluded that those who took to piracy did so out of extraordinary local circumstances and because they lacked traditional ties to family and village. The pirates, according to the report, were thus degenerates, such as exist, unfortunately, in all societies, even in those with the most advanced levels of civilisation.Footnote 33

In reality, however, the inexperience, inefficiency and lack of legitimacy of the new regime resulted in a sharp deterioration of the security situation and the breakdown of law and order in many parts of the colony, particularly in the region around the Mekong Delta. River piracy, extortion, banditry and violent attacks on French officials and interests were common. In order to police the Mekong and its delta and tributaries, the French relied on a system set up by the Nguyen Dynasty, which consisted of a fleet of small sailing junks, lorchas. Under the French administration the lorchas were charged specifically with the task of suppressing piracy. Each lorcha was manned by an indigenous crew and commanded by a junior French naval officer (enseigne or maître de la flotte). Captured pirates were sentenced − usually to immediate execution without the possibility of appeal − by the inspectors or other district officers holding judicial powers.Footnote 34 Harsh and arbitrary sentences passed on loose grounds by junior officers who had little knowledge of legal matters were common. The following case, presented to the governor of Cochinchina by a local French official, is one of several examples collected by Charles Le Myre de Vilers, who served as the first civilian governor of French Cochinchina from 1879 to 1882:

Considering that the three accused have come to surrender themselves, but only two days after the execution of Huan [an alleged rebel executed by the authorities] and that, judging from their physical constitution [leur physique], they seem to have been born to piracy and rebellion, and that they have made but incomplete confessions;

[We] declare them guilty of rebellion, etc., etc., and judge all three of them to decapitation and ask that their punishment be commuted to ten years’ detention at Poulo-Condore.

X …

Judgement approved without commutation of punishment: proceed immediately to execution.

GOVERNORFootnote 35

The arbitrary administration of justice continued throughout the era of naval administration in Cochinchina. Even in the 1870s alleged pirates and other criminals of Asian descent − in contrast to French citizens and fellow Europeans − did not have the right to appeal for mercy to the President of the Republic. This provision was justified by the extraordinary security situation in the colony and was abolished only with the transition to civil rule in Cochinchina in 1879.Footnote 36

The authorities also took measures to ensure that the sentences passed on pirates and other brigands received as much publicity as possible. Indigenous courts were instructed to translate extracts from all sentences passed on those sentenced to death for piracy or brigandage into Vietnamese and Chinese and display them on high-visibility coloured paper in all villages in their district, in the most public places.Footnote 37

Governor Bonard asked for reinforcements from Paris in order to deal with the security problems, but he was on the whole unable to establish an efficient administration in most of the colony during his two years in office.Footnote 38 In several letters to the Minister of the Marine, the governor expressed his despair at the chaotic situation and even asked to be relieved of his duties. He did not, however, explicitly mention in his letters piracy as a major cause of the troubles but rather pointed to ‘brigands and rebels’ who terrorised the population.Footnote 39

Although there was a good deal of confusion initially among French colonialists as to who was a brigand and who was a rebel, some of the more experienced officers tried to clarify the distinction based on the motives and social background of the perpetrators. According to Lieutenant Francis Garnier, a naval officer who served in Cochinchina and published two influential reports on the social, economic and political situation in the colony in the 1860s, the rebel leaders were educated men (lettrés), who had preserved their prestige among the population and had not at all ‘descended, as elsewhere, to the simple rank of pirates and common murderers’.Footnote 40

Regardless of the motives and character of the alleged pirates and other troublemakers, the French colonial authorities became convinced that in order to establish efficient control over the Mekong basin they had to control Cambodia. Essentially, thus, the French pursued the same tributary strategy with regard to Cambodia that the Vietnamese emperors had done since the eighteenth century.Footnote 41 Meanwhile, Cambodia’s King Norodom (r. 1860–1904) fought to save his dynasty against a series of internal rebellions and his country from being divided between Vietnam and Siam. To that end he approached the French and asked to be placed under French protection, and in August 1863 a Treaty of Friendship and Commerce was signed between the two countries. In contrast to the peace treaty with Vietnam signed the year before, the one with Cambodia contained two detailed and reciprocal but otherwise identical articles on the suppression of piracy:

In the case of French vessels being attacked or plundered by pirates in waters governed by the Kingdom of Cambodia, the local authority in the closest location, as soon as it gains information about the event, shall actively follow the perpetrators and not spare any effort in order that they be arrested and punished according to the law. The seized cargo, regardless of in which place it is found or in what condition, shall be returned to the owners, or, in their absence, to the hands of a French authority that will take responsibility for its return. If it is impossible to seize those responsible or to recover all of the stolen objects, the Cambodian officials, after having proved that they have done their utmost to obtain this goal, shall not be held financially responsible.Footnote 42

The pledges of the Cambodians to do their utmost to suppress piracy, however, were of little practical value, because the Cambodian government lacked the means by which to control the country. The French authorities were also unable to uphold security, and piracy was rife on the Mekong and its tributaries, particularly in Dinh Tuong (My Tho; today the province of Tien Giang), which formed the central province of French Cochinchina and potentially was one of the richest parts of the colony. According to Garnier, Dinh Tuong suffered heavily from attacks by pirates, who took refuge and found protection in Cambodia.Footnote 43

Despite wearying and costly gunboat patrols, the French authorities were unable to protect the population of the region from the depredations, arsons and killings committed by the river pirates. The result was that after four years of French rule more than half of the population of the province had fled to Vietnamese territory, and whole villages and towns were deserted. There was no denying, Garnier argued, that these unfortunate circumstances derived more or less from the peculiar borders of the French possessions in Cochinchina. The solution, he advocated, was the extension of French sovereignty in southern Vietnam in order to improve the security situation.Footnote 44

Such a course of action was adopted in mid 1866, when Bonard’s successor as governor, Admiral Pierre-Paul de la Grandière, backed by the French Emperor Napoleon III, but not by the Foreign Ministry, suddenly occupied the Vietnamese western provinces of the Mekong Delta. Ignoring the protests of the Nguyen court, de la Grandière then went on to annex the southernmost three Vietnamese provinces, Vinh Long, Chau Doc and Ha Tien, thereby considerably extending the territory under French control in Indochina.Footnote 45 The governor justified his move with reference to the security needs of the French colony, claiming that the three provinces under Vietnamese domination had served continuously as a refuge for rebels, both against the Cambodian government and the French colony, and provided them with both manpower, arms and munitions.Footnote 46 The Governor did not mention piracy in his official explanation, but it was widely reported in the French press that the provinces had served as a refuge for pirates and other troublemakers.Footnote 47

The treaty with Cambodia and the annexation of the three Vietnamese provinces were meant to bring about an improvement in the security situation in French Cochinchina. To some extent this objective was achieved, and in 1871 the governor, Admiral Marie-Jules Dupré, claimed that the colony enjoyed perfect tranquillity with no signs of trouble or agitation on any side.Footnote 48 Although the claim was probably somewhat exaggerated, piracy began to be brought under control in the colony from the beginning of the 1870s.Footnote 49

Piracy and Banditry in the North

Whereas piracy thus declined in the French-controlled southern part of Vietnam, the situation in the northern parts became increasingly unstable. The Nguyen Dynasty was weakened because of internal rebellions and an influx of Chinese bandits linked directly or indirectly to the Taiping Rebellion, particularly after the rebels were defeated in China in 1864. The Chinese government dispatched regular troops to assist Vietnam in quelling the anarchy. The reliance on foreign troops, however, served to further erode the authority of the Nguyen Dynasty in the northern parts of the country, and the support of the Chinese troops added to the financial difficulties of the regime.Footnote 50

With the Nguyen Dynasty thus occupied with rebellions and banditry in the north and with trying to counter the French invasions in the south, Chinese pirates congregated in increasingly large numbers on the Vietnamese coast and on the islands of the Red River Delta from where they launched attacks on maritime traffic and coastal villages. The purpose of the raids was both robbery and the abduction of people, particularly Vietnamese girls and women, who were trafficked to China, where they were sold as concubines, prostitutes or domestic slaves.Footnote 51 Pirate bands based on Hainan also harassed the junk trade between Cochinchina and Tonkin.

The increase in piratical activity in the Gulf of Tonkin and around Hainan was in part due to the increasingly efficient suppression of piracy in other parts of Asia, particularly in the South China Sea, along the South China coast and in the Strait of Malacca.Footnote 52 Pressured from both sides, Chinese pirates thus took refuge to Hainan and the coasts and islands of Tonkin, where no major naval power undertook to uphold maritime security.

In early 1872, however, the French sent the dispatch boat (aviso) Bourayne to Tonkin. Officially the mission was to gather information about the geography and political situation in northern Vietnam, but covertly the expedition was to prepare for a possible French military intervention in Tonkin. Many of the senior naval officers stationed in Cochinchina, including Governor Dupré, believed that only the wholesale annexation of the rest of Vietnam would produce political stability and favourable conditions for trade and investment in Indochina. Piracy, in that context, was less of an obstacle to maritime commerce than a convenient pretext for territorial expansion.Footnote 53

While surveying the Cat Ba Archipelago off the Red River Delta in early February 1872, the Bourayne encountered a fleet of pirate junks at sea. The French took up the chase and captured one of the junks after it was abandoned by the crew, whereas another junk was crushed against the cliffs after being hit by French cannon fire. The chase led the Bourayne to a natural port, sheltered by the islands surrounding it, where between 150 and 200 junks were anchored. According to the commander of the Bourayne, Captain Senez, the place was well known to local officials and people in general as a major nest of Chinese pirates. The port was completely hidden from sight from the sea, however, and impossible to find without prior knowledge of the location of the entrance. One could not, Senez claimed, find a more suitable location for the development and protection of piracy. He argued that the first step to be taken in order to eradicate piracy in the area must be to occupy Cat Ba, or at the very least make such frequent appearances in the archipelago that the pirates should no longer feel safe.Footnote 54

Despite the Bourayne’s victorious encounter with Chinese pirates, the expedition did little to improve the general maritime security situation in the waters of Tonkin. In May 1872 pirate fleets reportedly blocked most of the ports on the Vietnamese coast south of the Red River Delta.Footnote 55 At the same time, French business interests pressed for the extension of French control over northern Vietnam. The Red River seemed to hold great prospects for an expansion of French commercial interests to the interior of China, particularly Yunnan Province. The British, however, also appeared to be interested in the river, through which they hoped to be able to connect their interests in China with those in India and Burma. Imperial rivalry in Tonkin was further enhanced by Chinese military intervention in the north and – as in the Strait of Malacca around the same time − fears of German advances in the region.Footnote 56

One of the keenest advocates of French intervention in Tonkin was Jean Dupuis, a businessman, adventurer and longtime resident of East Asia. Stopping in Cochinchina on his way from Paris in 1872, Dupuis persuaded the Acting Governor to dispatch yet another naval expedition to Tonkin for the purpose of further exploring the possibilities of a French intervention, but now also officially for the suppression of piracy.Footnote 57 In October 1872 the Bourayne was thus once again despatched to Tonkin, where it cruised for fifty days and engaged on three occasions in combat against Chinese pirates. The fiercest battle took place on 21 October, when two pirate junks opened fire on the Bourayne off the island of Hon Tseu. The French retaliated and eventually, after a battle that lasted for two hours, sank one of the junks and captured the other. According to Senez, the pirates fought with unexpected vigour and a ‘bravery worthy of a better cause’. Three hundred pirates perished in the battle, whereas only two Frenchmen were wounded. Six days later, the Bourayne once again encountered and sank four small pirate junks, killing an estimated 120–50 Chinese, and the following morning yet another junk was destroyed, killing between 100 and 120 men.Footnote 58 Proudly summarising the results of the expedition, Senez claimed that it had rendered the Vietnamese government a service by unblocking its ports and ‘beaten, sunk or burnt seven pirate junks carrying altogether more than 100 cannons and manned by 700 or 800 men, more than 500 of whom were killed’.Footnote 59

The news of the outcome of the expedition was greeted enthusiastically in France. Senez was promoted and widely praised in the press for having exterminated the pirates for no more than seven wounded French soldiers.Footnote 60 The contrast is striking with the criticism that James Brooke’s expeditions in north Borneo had provoked in Britain some twenty years earlier, or the controversy surrounding the British (much less violent) intervention in Selangor the year before. In France there was hardly any questioning of the loss of life involved among the alleged pirates, despite the fact that many leading politicians and intellectuals were strongly opposed to further colonial adventures, wishing instead to concentrate on strengthening France’s international standing in Europe in the wake of the humiliating defeat in the Franco–Prussian War of 1870–71.

The perceived success of the expedition of the Bourayne notwithstanding, it seemed to have little effect on piratical activity in Vietnamese waters. The year after the expedition, an apostolic missionary stationed in eastern Tonkin reported:

The pirates are mainly Chinese, but there are also Vietnamese among them. Their base is around a port called Cat-Ba, close to Dâu-son [Dô-son]. When these bandits want to make their expeditions they assemble a greater or smaller number of boats [barques] according to the difficulty of the enterprise. Then they enter abruptly the rivers, without fear either of the mandarins or the royal troops, and they go from village to village, wherever it pleases them to carry out their depredations. If the people resist, they burn, pillage, massacre, causing countless calamities; nevertheless they spare and abduct in captivity the beautiful women and children.Footnote 61

Intervention in Tonkin

Despite the overwhelmingly positive response that the expedition of the Bourayne received in France, there was still no official support for military intervention in or annexation of northern Vietnam. Jean Dupuis, however, was determined to open up the Red River for commerce, with or without official French support. To that effect he assembled a private force, consisting of two gunboats, a steamship and a junk manned by altogether 175 men, and without bothering to secure the authorisation of the Vietnamese authorities, he headed off upstream on the Red River.

Most of the river and the territory around it was under the control of two rival bands of Chinese bandits, the Black Flags and the Yellow Flags, both of which had their origins in the defeated Taiping Rebellion. Even though he was a longtime resident of the region and spoke fluent Chinese, Dupuis failed to understand the complexity of the situation in upper Tonkin. By siding with the Yellow Flags – which before Dupuis’ intervention was a relatively obscure band that for several years had been fighting a losing battle against the Black Flags – Dupuis managed to further alienate Vietnamese officials, who already regarded him as a pirate and a troublemaker. Obviously unbeknown to Dupuis, moreover, the Nguyen Dynasty covertly sanctioned the Black Flags in order to maintain at least nominal control over northern Vietnam in the face of open rebellions, the defiance of senior officials and Chinese incursions. Dupuis also mistakenly believed that the Yellow Flags were in the business of protecting the local highland population and claimed that they sought to live in peace with the Vietnamese. By contrast, he regarded the Black Flags as composed for the most part of ‘pirates and bandits’ who terrorised the local population.Footnote 62

Dupuis’ attempt to open up the Red River for commerce ended in failure as his mission came in conflict with the Black Flags. Although this should have made him aware of the power of the Black Flags, he managed to convince the French Navy that the band did not constitute any significant threat. He also secured unofficial support from Paris for his plans to open up commerce with China on the Red River, despite the generally cautious attitude of the French government (particularly the Foreign Office) at the time with regard to engagements in further imperialist adventures. At the same time Governor Dupré, advised by the ambitious and pro-imperialist Francis Garnier, was keen to intervene in Tonkin. An intervention seemed motivated by the weakness of the Nguyen Dynasty and its obvious impotence in dealing with the rebels, bandits and pirates in the country, some of whom spilled over into the French colony in the form of smuggling, piracy, and social and political unrest. In addition, a priority for Dupré was to terminate the protracted negotiations with Hue over the formal cessation of the French provinces in Cochinchina, which had been achieved de facto in 1867, but had not been settled by treaty. A further reason for intervention were the indications of increasing British as well as German interest in Vietnam.Footnote 63

In this situation a window of opportunity opened up for the French Navy to intervene in Tonkin. In July 1873 the Vietnamese government sent two requests to Governor Dupré asking for his assistance to expel the troublesome Dupuis. Ignoring the hesitation of the central government in Paris, the governor dispatched a small expeditionary corps to Tonkin under the command of Lieutenant Garnier. Officially the object was to assist the Vietnamese government to expel Dupuis, by force if necessary. In addition, however, Dupré secretly instructed Garnier to occupy the citadel of either Kecho or Hanoi and one of the Vietnamese strongholds on the coast in order to put pressure on the Vietnamese government to agree to a settlement of the territorial question. Although they were premeditated, the occupations were to be represented as sprung from necessity in order to quell the anarchy and rebellions that plagued the country, which the Vietnamese authorities were unable to deal with.Footnote 64

The small and ill-equipped expedition, initially consisting of fewer than a hundred men and two small vessels, one of which sank on the way, reached Hanoi at the end of October. Within a few weeks Garnier got in touch with Dupuis, stormed and occupied the citadel at Hanoi – allegedly because of the uncooperative attitude of the Vietnamese officials – and unilaterally declared the Red River open to commerce. As the French had hoped, popular disaffection with the Nguyen Dynasty surged, and pro-French elements, mainly consisting of people loyal to the former Le Dynasty and Catholics, took control over the coastal provinces.Footnote 65

By early December the intervention appeared to have achieved its objectives, and the Vietnamese government seemed willing to settle the territorial question. The Vietnamese, however, tried to weaken the French by using the Black Flags to assault them, and on 21 December a band of Black Flags attacked the citadel at Hanoi. The attack was repulsed, but Garnier, who led a small detachment in pursuit of the attackers, was killed in an ambush, along with three French soldiers. The event prompted the end of French intervention in Tonkin. The expedition withdrew, and the occupied citadels and other strongholds were returned to the Vietnamese.Footnote 66

Although piracy was mentioned in the correspondence between Dupré and the Minister of the Marine as a reason for the military intervention of 1873, it was not officially identified as a major reason for the intervention. In Dupré’s instructions to Garnier the suppression of piracy was mentioned merely as a secondary task, to be exercised only if opportunity arose.Footnote 67 Following the death of Garnier, however, the French colonial and metropolitan press eagerly seized on the theme of piracy. The Courrier de Saïgon, for example, claimed that Garnier had been obliged to take control over Hanoi and other provinces in order to make the pirates and rebel bands respect the authority of the Vietnamese king, even though the Black Flags were described as a band of Chinese rebels rather than pirates.Footnote 68 The official gazette of the French Republic, meanwhile, claimed that the attack on the citadel in Hanoi was prompted by the concentration of pirates and rebels interested in plunder, and the Black Flags who had attacked the citadel on 21 December 1873 were described as ‘Chinese pirates’. The gazette also reported that the expedition had sunk twenty-six pirate junks at the entrance of the Red River.Footnote 69

The French withdrawal from Tonkin was followed by diplomatic negotiations, resulting in the signing in March 1874 of the Giap Tuat Treaty between France and Vietnam, which in effect replaced the Saigon Treaty of 1862. For France, the major gain was Hue’s unconditional acknowledgement of French sovereignty over the southern provinces and several provisions that served to open up Vietnam to French economic interests. The treaty implied a French protectorate over Vietnam, but the very word protectorate was not mentioned in the treaty text. France acknowledged the full sovereignty and independence of Vietnam while pledging to ‘render necessary support [to the Vietnamese king] for him to maintain order and peace in his territory, to defend him against any attack and to destroy the piracy that ravages part of the coasts of the Kingdom’. Such support was to be given only at the request of the Vietnamese king and for free. The Vietnamese government was also to receive from France (again for free) five fully armed steamers for the purpose of suppressing piracy along the Vietnamese coast.Footnote 70

In Paris, however, Parliament was reluctant to ratify the new treaty. Garnier’s death and the failure of his expedition seemed to demonstrate the perils of further colonial expansion in Indochina. The government, on the other hand, presented the new treaty as a necessity in order to assist the Vietnamese king to uphold law and order. According to the motivation, read by Senator Admiral Bénjamin Jaurès to Parliament in July 1874:

The Kingdom of Annam is today exposed to two types of dangers that paralyse all its resources. Tonkin, the richest of its provinces, has for some years been penetrated both by Chinese rebels pushed out of their territory and by regular Chinese troops dispatched to pursue them. The coasts are at present forbidden to commerce, less because of legal prohibitions that ban its access than by the pirates who form veritable naval squadrons in these provinces and against whom we ourselves, on several occasions, for the security of the seas, have had to undertake costly and bloody expeditions.Footnote 71

The suppression of piracy, moreover, was framed both in highly securitising terms and as part of the French and European civilising mission. Continuing the plea, Jaurès said:

France, after having, in concert with England, opened new ports in China to European commerce, has recently continued its work of civilisation and progress by obtaining the opening of ports in Vietnam. This kingdom will, moreover, be the first to reap the fruits of its concession; for everywhere European commerce penetrates, it carries with it peacefulness and respect for property as well as transactions. The south of Tonkin will soon see the disappearance of these bands of insurgents who there have brought about a state of permanent disorder.

Our protective vessels will soon have finished off this pirate fleet which, since time immemorial has carried out ravages on the coasts and prevented all sorts of vessels, all commerce and even the fishing from which the populations of the littoral to a great extent make their living, descending in hordes of bandits who penetrate the interior and engage in pillaging of all sorts, abducting the men to deliver them to the coolie recruiting agents and selling the women in order to fill the houses of debauchery in China.Footnote 72

The conservative majority that dominated Parliament, however, was tied to the policy of so-called continental patriotism, meaning that the main foreign policy priority for France should be to defend her interests in continental Europe. In addition, the conservatives were strongly opposed to colonial expansion in Vietnam because it might lead to a conflict with China.Footnote 73 Among left-wing politicians, opposition to colonial expansion was even more pronounced. One of the most vocal anti-imperialists in Parliament, the Radical Socialist Georges Périn, argued that the task of maintaining peace and order among an estimated 15 to 20 million Vietnamese would be insurmountable and foolhardy. Why, Périn asked, should France risk the lives of her soldiers in order to police the Kingdom of Vietnam? The task, according to Périn, was not just to keep order among the Vietnamese, but also among the foreigners, in particular the pirates who infested the entrance of the Red River. ‘When we shall have defended the south of Tonkin against the pirates, we shall have to defend the north, on the border to Yunnan, against the Chinese Muslims, who the Chinese Buddhists try to push toward Tonkin.’Footnote 74

Despite the protests the treaty was ratified and shortly afterwards followed up by a commercial treaty, signed on 31 August 1874, which in turn was ratified the following year. In the commercial treaty, France renewed its promise to assist the Vietnamese government in the suppression of piracy. However, whereas the first treaty, as we have seen, spoke of suppressing the ‘piracy that ravages part of the coasts of the Kingdom’ – thus limiting the mandate to the sea and coastal regions − the commercial treaty spoke of the French obligation to ‘make all efforts to destroy the pirates of the land and the sea, particularly in the vicinity of the towns and ports open to European commerce’.Footnote 75 The difference may not have seemed like a major one to the Vietnamese, because there was little distinction in the Vietnamese language between bandits on land and pirates or bandits at sea. The provision of the commercial treaty nevertheless gave France a stronger mandate to intervene in the affairs of Vietnam in the (likely) event that the Vietnamese government would prove unable to uphold security on land or at sea.

The five steamers that France had promised to donate to the Vietnamese government were delivered in July 1876, and at the request of the Vietnamese each of the five vessels was put under the command of a French captain, recruited from the merchant navy.Footnote 76 Relations between the French captains and the Vietnamese officials, however, were from the outset plagued by cultural and linguistic misunderstandings and mutual distrust, which effectively prevented the steamers from fulfilling their purpose. The commander of one of the gunboats, Scorpion, Jules-Léon Dutreuil de Rhins, found it extremely difficult to know whether a junk was a pirate vessel or not. According to the captain, the Vietnamese themselves could not see a junk without suspecting that it was engaged in piracy, and for his own part he believed that all of them were, given the opportunity. He was also convinced that Vietnamese officials colluded with the pirates, particularly the Chinese pirates, who were more feared than the Vietnamese and who seemed to enjoy complete impunity. When a pirate junk was captured, Dutreuil de Rhins asserted, the perpetrators were taken before the authorities in Hue, where they were immediately released on condition that they agreed to put their forces at the government’s disposal and henceforth only pillage ‘in good company’, as the captain put it.Footnote 77

In contrast to the spectacular battles of the Bourayne a few years earlier, the five gunboats that France gave to the Vietnamese government do not seem to have encountered or defeated any pirates. All five captains resigned within a few months, allegedly because of the misconduct of Vietnamese officials. The boats were subsequently either abandoned or wrecked along the Vietnamese coast.Footnote 78

Piracy and Trafficking

Although the fiasco of Garnier’s expedition was held up as warning against further colonial expansion by anti-imperialists in France, the 1870s saw a gradual strengthening of procolonial sentiments in France. Toward the end of the decade the colonial project showed an unprecedented capacity to mobilise supporters, thereby setting the stage for the occupation of what remained of the Vietnamese Kingdom.Footnote 79

Piratical activity continued in Vietnamese waters throughout most of the 1870s but fluctuated and seems at times to have been relatively sparse. With little naval capacity of its own, the Vietnamese government had little choice but to welcome the assistance given by France, and the Vietnamese came to rely almost exclusively on French patrols to maintain a reasonable level of maritime security. In 1877, Hue even asked France to build a fort with a permanent garrison on Cat Ba, the major base for the pirates off the Tonkinese coast.Footnote 80 The French government – reportedly to the great disappointment of the Vietnamese – declined but continued to patrol Vietnamese waters. The naval presence seems to have brought about a substantial decrease in piratical activity. According to a French naval report, largely based on information provided by Vietnamese officials, piracy around Cat Ba and other places along the Tonkinese coast seemed to have all but disappeared in 1878:

The 9 [February 1878] at 9 o’clock in the morning we again dropped anchor at Cacba [Cat Ba], where the tranquillity still was perfect. According to the French missionaries and the Annamite mandarins, no pirate had been seen in these waters for several months; this fortunate development is generally attributed, on the one hand certainly, to the cruises of the French warships, but more particularly to the destruction of the village of Traly, the centre for selling stolen goods, procurement and the place of refuge for the pirates.Footnote 81

The problem soon resurfaced, however, and several naval expeditions were dispatched from Cochinchina to Tonkin in 1879–80. The expeditions destroyed several pirate junks and killed or captured some of the perpetrators, but the depredations nevertheless continued. According to the French consul in Haiphong, government officials and some Chinese businessmen seemed to be colluding with the pirates, and the consul suspected that the pirates who were captured by the French expeditions and turned over to the Vietnamese authorities for punishment were frequently allowed to escape or bribe themselves free.Footnote 82 The French cruises thus appeared to have the effect of containing some of the piratical depredations but did little to disrupt the networks and support that underpinned them.Footnote 83

The most lucrative part of the pirates’ business was the trafficking of abducted people, and this trade involved the complicity of both Chinese and Vietnamese businessmen and officials, as well as European merchants and ship captains in East Asia. The surge in piratical activity in Vietnam can thus not be understood in isolation, or just as the last vestiges of the civil unrest in China around the middle of the century. The raiding and the abductions were deeply embedded in regional and even global commercial networks, and local businessmen and notables often profited from the piratical activity. In contrast to the situation in the Straits Settlements, thus, pressure to end piracy and trafficking in Vietnam did not come so much from the local business community as from local missionaries and humanitarians in France.

The trade in humans seems to have begun in the 1860s and quickly developed to become the major source of revenue for the pirates.Footnote 84 The trafficking of young women and girls for the purpose of prostitution or other forms of sexual abuse was particularly repulsive to the French missionaries in Indochina. They frequently reported on the problem in letters, many of which were published in France, thus drawing public attention to the problem in the metropole.

Hundreds and possibly thousands of people were abducted from Vietnam each year from the 1860s until the end of the nineteenth century. Many victims were simply seized by force while fishing or travelling by boat, or when working, walking or playing on the beach, whereas others were tricked into captivity. The methods employed by the pirates to capture their victims varied. According to Monsignor Colomer, some Chinese pirates colluded with Vietnamese brokers – ‘perverse Annamites’, as he called them – who out of vile interests tricked their brothers into traps where they were caught and delivered as slaves to Chinese buyers.Footnote 85 One gang of pirates, captured in 1880, sent forward a female member of the band to capture children onshore, a method that was seen as particularly objectionable both in Vietnamese and French eyes. The woman was found guilty to a higher degree than her accomplices by the Vietnamese court that handled the case, and she was sentenced to execution by strangling, rather than decapitation, which was the punishment that the other members of the band received.Footnote 86

Colomer claimed that the majority of the victims were women and children, and most contemporary reports – both by missionaries and naval officers – seem to corroborate this impression. The trafficking of women was much more profitable than the trafficking of men, as young women commanded substantially higher prices. Young women who were considered attractive could be sold at a premium of up to two or three times as much as young men, according to the information obtained by a French gunboat commander.Footnote 87 The vast majority of freed victims were also women and children, including both boys and girls.Footnote 88

Even though the majority of victims were thus probably women and children, it is likely that a large number of captured men went underreported. Kidnapped men were more difficult to identify because of the flourishing coolie trade in East and Southeast Asia, by which poor people, mostly men from southern China and India, were recruited as indentured labourers to work on plantations, mines and construction sites on the West coast of America or in the European colonies in the Caribbean, Southeast Asia and East Africa and elsewhere. Asian brokers were engaged by European and American merchants who transported the coolies to their destination. Whereas the trade in coolies generated large profits for the merchants and brokers, it was often less advantageous for the coolies. Many were made to sign long contracts, typically ranging from five to eight years, usually for a modest one-off payment in cash, and to labour under slave-like conditions.

According to contemporary missionary reports, the onset of the abductions in the 1860s was linked to the boom in the coolie trade.Footnote 89 Chinese pirates operating in Vietnam realised that they could make larger profits if they bypassed the brokers and did away with all appearances of a voluntary arrangement. Instead they simply abducted Vietnamese men and transported them as captives on their junks to colonial ports or treaty ports in China, where they were sold on to European and American coolie traders. Vietnamese men who had been abducted by Chinese pirates were taken to Macau, where they had their heads shaved in order to pass off more easily as Chinese. From Macau the coolies were promptly dispatched to Cuba or California, from where no one, according to a contemporary observer, ever returned. Other major ports for the coolie trade in East and Southeast Asia, apart from Macau, were Canton, Penang and Singapore.Footnote 90

In contrast to the men, most of the abducted women and children were trafficked to China, where demand was great for domestic servants, concubines and prostitutes. According to André Baudrit, who wrote the first systematic study of human trafficking in Indochina and China, there were four principal reasons the Chinese turned to Vietnam for the supply of human cargo, apart from the geographical proximity and the existing networks of trade and contacts. First, the abducted Vietnamese were generally unfamiliar with the geography, language and culture of China and thus unlikely to fend for themselves or try to escape. Second, many Chinese looked upon the Vietnamese as an inferior and less civilised race, and consequently saw them as suited to low-status occupations, such as prostitution and domestic servitude. Third, the Chinese owners of Vietnamese slaves could mistreat their subjects with impunity, because neither neighbours nor the authorities were likely to take an interest in their fate. Last, it was cheaper to buy a Vietnamese wife or domestic servant than a Chinese one due to the racial prejudices against the Vietnamese in China.Footnote 91

The abductions, however, cannot be understood only from the Chinese perspective. The trafficking of Vietnamese in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was linked to the colonial networks of maritime commerce and traffic, regionally as well as intercontinentally. The governor of Cochinchina, Charles Le Myre de Vilers, for example, suspected that, apart from Vietnamese officials, European captains participated in the trafficking of Vietnamese.Footnote 92 At the very least, European coolie merchants, like the authorities in Macau and other colonial ports, turned a blind eye to any indication that the coolies delivered by Chinese pirates might have been forcibly abducted rather than made to sign a disadvantageous but legally binding and in theory voluntary contract.

On several occasions French vessels seized pirate junks and freed dozens of Vietnamese, mainly women and children who had been abducted in raids on local boats or on the coast and islands of Tonkin. The commander of the gunboat La Massue, L. Gros-Desveaux, described the conditions that the abducted Vietnamese of one pirate junk, captured in Tonkin in 1880, were forced to endure during the passage to China:

These 44 women and children were squeezed in one upon another, on stones, half dead from bad treatment, misery and hunger. These unfortunates, who between them occupied but a fifth of a junk of 11 meters, had not got ten any air or daylight except but by a hole of 4 square centimetres drilled in the deck since they were torn from their homes a fortnight ago, some by violence and some by trickery … Three of them had perished from suffocation since departure.Footnote 93

Although French patrols probably reduced the number of raids and abducted people somewhat, the French Navy only had one dispatch boat and two gunboats permanently stationed in Indochina, which clearly was insufficient to uphold maritime security. In Paris, meanwhile, efforts to secure additional funding for the Navy in Indochina met with resistance, both in the government and in Parliament. A further problem was that the French, according to the 1874 Treaty with Vietnam, did not have the right to search foreign vessels in Tonkinese ports.Footnote 94

In July 1881 Parliament eventually decided to approve an increase in funds for the Navy in Tonkin by adding two dispatch boats, two gunboats and three river boats, all heavily armed. The purpose was for France to fulfil her obligations according to the 1874 Treaty, particularly with regard to the suppression of piracy, and to render safe communications with the interior of China on the Red River, which was still blocked by the Black Flags.Footnote 95

The decision to release the funds was contested because it seemed to set France on the path of a more aggressive policy of colonisation in Indochina, thereby adding to the expansionist policies already pursued in North and West Africa. Georges Périn again emerged as the most vocal opponent of the bill in the Chamber of Deputies. He argued that France should not continue its course toward an increasingly colonial foreign policy. ‘Our politics must not be colonial to the point that it ceases to be continental’, Périn argued rhetorically in a bid to appeal to the conservative majority of the Chamber. In response to Périn’s question as to why France should seek to extend her territory overseas, the Minister for the Marine and the Colonies, Vice-admiral Georges Charles Cloué, vehemently denied that the government had any plans to conquer Tonkin. The government, according to Cloué, only wished to have an ‘honourable situation’ in which law and order prevailed. The debate was followed by a vote in which an overwhelming majority of 310 deputies voted for the bill and only 86 against.Footnote 96

Piracy and Colonial Expansion in Tonkin

For those in France who favoured further colonial expansion, the fact that piracy and the trafficking of women and children continued in Tonkin served as a strong argument for invention. A Republican politician and author, Paul Deschanel, for example, wrote a pamphlet entitled ‘The question of Tonkin’ in which he lamented the insufficient efforts on the part of the French Navy to suppress piracy in Vietnamese waters. Upholding maritime security in Tonkinese waters, Deschanel argued, was both a matter of dignity for France and a matter of furthering her interests in Eastern Asia. He also worried that the prevalence of piracy in Indochinese waters might serve as a pretext for other countries, notably Britain or Germany, to intervene and thus threaten French hegemony in the region.Footnote 97 In the view of Deschanel and other proponents of colonial expansion, the suppression of piracy and human trafficking in Indochina thus united several of the key objectives of France in the East: the assertion of national dignity and the spread of French civilisation, the promotion of French economic interests, and the furthering of the country’s geopolitical interests, particularly in relation to other imperialist nations in Europe.

The weakness of the Nguyen Dynasty and the continuing unrest in Tonkin combined with the increasing imperial scramble among the European powers to set the stage for further French colonial expansion in Indochina. In France the policy of colonial expansion began to acquire more of a clear sense of direction from the end of the 1870s, notwithstanding the protestations of the anticolonial opposition. The influence of these critical voices, however, weakened as pressure for further colonial expansion mounted from several influential and partly overlapping groups: naval and army officers, businessmen, missionaries, scientific societies and politicians.Footnote 98

As the colonial camp thus gained momentum, the central question shifted from whether or not France should extend its influence in Indochina to by what means and how quickly colonial expansion should progress. Indochina was a distant and relatively obscure place for most people in France, and although it occupied centre stage in the debates about colonialism in the 1870s and 1880s, it was far from the top foreign policy priority. French cabinets, moreover, were mostly short-lived, and changes in government led to frequent shifts in foreign policy orientation. As a consequence, official French policy in Indochina often lacked a clear sense of purpose and was largely formulated more or less ad hoc as events unfolded.Footnote 99

By the beginning of the 1880s it seemed clear, both to the advocates of colonial expansion and to its detractors, that the middle position that France occupied in Indochina – with a colony in the south and a quasi-protectorate in the north – was untenable in the long run.Footnote 100 The dream of developing the commercial potential of the Red River and reaching the interior of China was also strong but failed to materialise, apparently because of the lack of social and political stability in Tonkin and the control that the Black Flags had over the river.

Against this background, Governor Le Myre de Vilers began to argue for a restrained and peaceful, as far as possible, intervention in Tonkin. He was convinced that France needed to take swift action in order to prevent other imperial powers from establishing a foothold in Vietnam or for the country to disintegrate completely, which he believed were the two most likely scenarios should France abstain from intervention. His proposition, put forth in a letter to the Minister for Commerce and the Colonies in 1881, was to send a small force of marine infantry to Hanoi, where they would occupy the citadel – like Francis Garnier had done in 1873 – and take over the administration of the city and its environments. The governor, optimistically, estimated that the customs and farm revenues from Hanoi and its hinterland would be enough to cover the cost of the French intervention. The Vietnamese government would probably protest, Le Myre de Vilers foresaw, but this was of little consequence, given its weakness. Other European powers, meanwhile, would probably be uninterested or, in the case of Britain, even approve. The only major power that might object was China, but the country would probably abstain from intervening, given that France was not to declare war and could justify her intervention with reference to the 1874 Treaty. The only major foreseeable obstacle to the success of the expedition, according to Le Myre de Vilers, were the Black Flags, who controlled much of Hanoi and the Red River. These were to be dealt with through the inflicting of serious punishment early on. He suggested shelling one or two of their strongholds with gunboat artillery while avoiding disembarking or engaging the Black Flags in close combat, because, the governor argued, even ‘the smallest defeat could be harmful to us’.Footnote 101

Assuming that he had the support of the government, Le Myre de Vilers proceeded to dispatch a small armed force to Tonkin in early 1882. In his instructions to the commander of the expedition, Captain Henri Rivière, the governor emphasised the need to avoid any contact, direct or indirect, with the Black Flags. If such contact nevertheless could not be avoided, the instructions were specific: the Black Flags were to be dealt with as pirates, yet treated humanely in order to demonstrate the magnanimity and good intentions of France:

You must not have any relations, direct or indirect, with the Black Flags. To us, they are pirates, and you shall treat them as such, if they place themselves in your way; however, as we must demonstrate that we spare human lives, instead of executing them, you shall dispatch them to Saigon and I will have them imprisoned at Poulo-Condore.Footnote 102

In contrast to his previously laid-out plan, however, the governor did not instruct Rivière to occupy the citadel at Hanoi, and he was to use as little force as possible. Rivière was also to survey the Red River, but the instructions did not explain how Rivière was to proceed on the river without confronting the Black Flags.Footnote 103

Rivière arrived in Hanoi in March 1882 with 400 men. Officially his mission was to ensure the security of French citizens in Vietnam. In a letter that Rivière delivered to the Vietnamese emperor, the governor drew attention to the anarchy in Tonkin, and he specifically mentioned the harassment of two French mining engineers in January by the leader of the Black Flags, Luu Vinh Phuoc (Liu Yongfu), whom Le Myre de Vilers described as the ‘Chinese pirate chief’.Footnote 104

As tensions mounted between the Vietnamese and the French in Hanoi in the weeks following the arrival of the French troops, Rivière decided to take the citadel with force. He did so in April but was unable to move against the Black Flags. Neither could he undertake the planned survey expedition on the Red River because the water was too low for the French gunboats. For several months Rivière and his troops were thus confined to the citadel at Hanoi, awaiting, on the one hand, further instructions from Paris or Saigon and, on the other, the rains that would flood the river and make it navigable for the French vessels. Meanwhile, the French troops were besieged by the Black Flags, and it seemed to the French that the country was teeming with pirates.Footnote 105 On 18 May 1883 Rivière instructed one of his subcommanders to concern himself as little as possible with piracy. ‘In a country where everybody is a pirate, it is a question which constantly reappears and which bores me’, he wrote, obviously somewhat despondently.Footnote 106

The day after he wrote the letter Rivière was killed when he led a sortie against the Black Flags, not far from where Garnier had fallen under similar circumstances ten years earlier. In contrast to the swift withdrawal of the French expedition after Garnier’s death, however, the killing of Rivière hardened French resolve to intervene in Tonkin. A month before the commander’s death the French government had laid a bill before the Chamber of Deputies demanding additional credit for the expedition in Tonkin. As in 1881, the object of the intervention was motivated in terms of the need to uphold peace and order, which was expressly linked to the national pride and dignity of France. The French government was careful not to represent the intervention as directed against the Vietnamese government, but instead emphasised that the object was to suppress piracy on the Red River and thereby secure freedom of commerce and traffic. According to the motivation of the bill, which the Minister of Foreign Affairs Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour read to the Chamber:

The Red River has never, in fact, been open to commerce, its banks continuing, in several places, to be occupied by the pirates known by the name of Black Flags, who prevent the traders from moving freely. On several occasions, French travellers, having entered the country after having complied with all requirements of the treaty, have been molested, without our chargé d’affaires in Hue having been able to obtain satisfaction …

With the authorization of the joint instructions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Marine, the Governor of Cochinchina had, in the month of January 1882, decided upon certain measures for the purpose of emphasizing our protectorate over the Annamite Empire. It was not, however, about a conquest of Tonkin, or even a venture that could lead us to intervene in the internal administration of this country. The proposition was only to dispatch on the Red River the naval forces necessary to go after the Black Flags, who occupy the river banks, and thereby to secure commercial freedom. It was thus not, properly speaking, a military expedition that we undertook, because our troops were only to act against the pirates.Footnote 107

Pursuing the argument, the government’s demand for a further increase in funding for the Navy in Tonkin – this time of 5,300,000 francs, more than twice the amount approved by the Chamber in 1881 – was also motivated in terms of the need to maintain the peace and specifically to rid Tonkin of all ‘bands of pillagers and fleets of pirates that oppress it’.Footnote 108 The bill was passed, first before the death of Rivière, with a vote of 351 for and 48 against, and then once more after his death, unanimously, with even vocal anti-imperialists such as Périn closing ranks behind the government and demanding that the death of Rivière be avenged.Footnote 109