“An inability to view Hinduism on its own terms has shaped the study of comparative religion…”—Gauri ViswanathanFootnote 1

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, political scientists have begun to rediscover the importance of religion in political life.Footnote 2 After a long period in which scholars adhered to a “secular understanding of the political world” (Wald and Wilcox Reference Wald and Wilcox2006, 523), the study of religion has once again become a growing area of focus in political science. This change can be seen in the 2008 founding of the journal Politics and Religion by the American Political Science Association's Religion and Politics organized section (Kettell Reference Kettell2016), and in the fact that scholars have recently advanced the study of religious politics along many different fronts. Kalyvas (Reference Kalyvas1996) explores the pattern of Christian political party formation in Western Europe. Hurd (Reference Hurd2007) studies the social construction of secularism and its impact on international relations. Tepe (Reference Tepe2008) examines the growth of religious parties in Israel and Turkey. Both Katznelson and Jones' (Reference Katznelson and Jones2010) edited volume and Toft, Philpott, and Shah's (Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011) book explore the global resurgence of religion. Putnam and Campbell (Reference Putnam and Campbell2010) analyze the changing religious landscape of contemporary America. Grzymala-Busse (Reference Grzymala-Busse2015) examines the political influence of churches.

As with any new—or in this case, renewed—research program, there are bound to be omissions, and in this case one in particular stands out: the study of religion outside the context of the Abrahamic traditions (Cadge, Levitt, and Smilde Reference Cadge, Levitt and Smilde2011, 440). Most American political scientists have focused on the Abrahamic, monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—mainly just Christianity—and therefore their work has often centered around factors such as “faith” and “doctrine,” or the power of churches.Footnote 3 But many of the so-called “Asian religions”Footnote 4—e.g., Hinduism, Buddhism, Shinto—are both “orthoprax” (practice-centered, where rituals and rites of passage take precedence over issues of belief) and non-congregational. If the goal is for political science to “take religion seriously” (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012), then understanding these overlooked traditions must be considered a pressing task.Footnote 5

Many of our most pertinent questions about religion and its effect on politics—e.g., How does religion affect voting behavior? Are individuals secularizing?—require valid measures of religiosity. For the Abrahamic faiths, social scientists have usually used survey questions that ask whether an individual believes in god and attends religious services to operationalize what is a notoriously tricky concept (Huntington Reference Huntington1996; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2004). But, as I detail, these same measures are less valuable for measuring religiosity in other traditions. The Asian religions are distinctive enough to require a new set of indicators for social scientists, and, more generally, a substantively different way of thinking about religion.

This article examines the measurement of religiosity through a case study of Hinduism, the world's oldest and third most populous religious tradition, as well as the world's most populous Asian religion. This particular tradition constitutes a “hard case” for this topic: I think Hinduism worthy of this moniker because it has been variously described as a religion, a family resemblance of religions, an ethnic identity, a “way of life” (according to the Supreme Court of India), and a set of ethical maxims. As Dube (Reference Dube, Dube and Basilov1983, 1) once noted: “Birth and minimal cognitive participation are enough to identify one as belonging to the Hindu faith.” A pious Hindu can just as easily be a meat-eating atheist who never sets foot in a temple as a vegetarian monotheist who goes to temple daily. How should scholars approach measuring religiosity in a tradition that has been described as “an impenetrable jungle, an all-absorbent sponge, a net snaring everything…” (Michaels Reference Michaels2004, 3)?

The few existing quantitative measures of Hindu religiosity tend to draw on questions from India's National Election Study (NES).Footnote 6 Chhibber (Reference Chhibber1997; Reference Chhibber2014), for example, recognizing the orthoprax nature of Hinduism, focuses on religious practice, measuring Hindu religiosity via questions on the frequency of prayer, going to temple, and participating in religious services. Thachil (Reference Thachil2014, 460) similarly constructs an index measure of Hindu piety from these three questions, but adds a question on how often individuals keep religious fasts. The validity of these measures, however, is up for debate: they include certain activities (going to temple) that are not compulsory, while at the same time exclude other activities (adhering to norms of purity and auspiciousness) that most scholars of Hinduism have highlighted as highly significant (Narayanan Reference Narayanan, Pechilis and Raj2013; Flueckiger Reference Flueckiger2015).

This article uses a comparative survey of 100 households in India to test the validity of existing measures of Hindu religiosity. My methodological approach involves randomizing two versions of a survey across and within the population of two similar villages in the north Indian state of Bihar. Recognizing that there is no single authoritative view of Hinduism, I surveyed men and women, as well as those from a variety of different caste groups. The first survey uses closed-ended questions, drawing on examples from previous work on Hinduism undertaken in India by the NES, as well as the World Values Survey (WVS). These questions represent the standard social science understanding of Hindu religiosity. The second survey uses similar questions but with open-ended responses, providing an opportunity for Hindus to describe their religion in any way they desire. The primary point of this exercise is to determine how the academic understanding of Hinduism compares with Hindu self-understandings. I aim to provide the kind of rich ethnographic detail about Hindu religiosity that is normally the province of religious studies scholars and anthropologists, except systematized in the form of survey responses that social scientists use to construct indices of religiosity.

A comparison of survey responses yields several noteworthy albeit rather messy findings. First, most respondents struggled to understand the open-ended questions. The definition of terms that are considered central to how we understand religion in social science—for example, as basic a term as “religious rituals”—were often completely unclear to respondents. This highlights the problem of translating terms (“ritual” has at least 10 Hindi translations), as well as issues surrounding survey enumeration in societies with low levels of education.

Second, the survey indicated some major discrepancies between what academics and Hindus think of as religion. While some of the responses did not vary across both sets of surveys (e.g., almost all respondents used the term “Hindu” to describe themselves), other responses were radically different. For example, most existing surveys ask about temple worship because attending religious services is important in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. When presented with this option, more than 90% of respondents indicated they went to temple. But in an open-ended format, only 16% of respondents mentioned this activity as one of their rituals. Clearly what Hindus consider a ritual differs considerably from our social scientific understanding of this concept. Similarly, some activities (like puja, i.e., worship) were listed as rituals, beliefs, and customs. Scholars must, of course, create categories to interpret and make sense of the social world, but clearly the content of religious categories, as well as the boundaries between them in this case, varies significantly between the researcher and the subject.Footnote 7

Finally, the surveys also offer fresh insights into what being religious means in non-Western cultures. For example, respondents listed eating yogurt and sweets at specific times during the day, feeding cows, and obeying rules about purity/pollution and auspiciousness/inauspiciousness as rituals.

There are two caveats to mention here. First, the point of this article is not to compile a list of differences between Hindu and non-Hindu traditions, or to exotify Hinduism,Footnote 8 but rather to highlight what is missing in existing survey work: the range and diversity of what is considered religious in the Hindu tradition far outstrip what social scientists—especially those reared in Christian societies—are used to examining. Second, my goal is also not to construct a new measure of Hindu religiosity and connect it (using statistical analysis, e.g.) to political outcomes. That is an important task for future research, but my ambition here is more limited. I am primarily interested in seeing whether existing measures of religiosity accurately mesh with Hinduism on the ground. This may be a question about “mere description” (Gerring Reference Gerring2012), but properly describing the Hindu religion is itself a valuable task.

This article makes three contributions to the study of religion in political science, with a goal toward productively challenging and retooling how scholars have traditionally approached this topic. The first contribution deals specifically with the study of Indian politics. As Hindu nationalism since the 1980s has become a major force in Indian politics, many scholars have sought to explain the success of this movement (Jaffrelot Reference Jaffrelot1998; Hansen Reference Hansen1999). One common finding is that voting for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the main Hindu party in India, is either not predicted by religiosity (Chhibber Reference Chhibber1997) or weakly predicted by it (Thachil Reference Thachil2014). But this argument assumes that going to temple and attending religious services are valid metrics of Hindu religiosity. The survey work in this article, however, indicates that this is not what many Hindus think of as the constituent elements of their religion. This article represents a first step toward validating and improving our metrics of Hindu religiosity, a task that must precede examining how religion affects political behavior.

Outside the specific context of India, this study illustrates that social scientists should not assume that the same metrics that have been used to study religiosity in Abrahamic societies also work outside these settings. Studies of Hinduism—as well as Sikhism, Shinto, or the myriad indigenous African, South American, and North American traditions—need different indicators that capture the complexity and diversity of these traditions. It may be “seductive” to quantify all religions in the same way for cross-national comparisons (Merry Reference Merry2016), but an ethnographically rich understanding of Hinduism demonstrates why some Abrahamic assumptions about what religion is can lead to serious misunderstandings. Finally, in a more practical sense, scholars who use survey questions to construct religiosity measures for Asian traditions are advised to pay attention to issues of translation, context-specificity, and self-understandings of what religion is and what it means to be religious.

RELIGION AND POLITICAL SCIENCE: BEYOND AN ABRAHAMIC WORLDVIEW

In the post-World War II period, the study of religion in political science could best be described as moribund. Despite a renewal of interest in the last two decades, religion remains understudied, especially compared to its study in cognate disciplines like sociology (Kettell Reference Kettell2012) and economics (Iyer Reference Iyer2016). In their article discussing (the lack of) religion articles published in the American Political Science Review, Wald and Wilcox (Reference Wald and Wilcox2006, 526) argue that one of the reasons for this research deficit might be the complexity of the subject and how to measure it. This has been a long-standing problem. Max Weber, who made seminal contributions to the social scientific study of religion, notably avoided providing a definition at all: “To define ‘religion’, to say what it is, is not possible at the start of a presentation such as this. Definition can be attempted, if at all, only at the conclusion of the study” (Weber Reference Weber1965, 1).

As political scientists have begun to focus again on religion and religiosity, it is clear that these topics have largely been viewed through an Abrahamic lens. The classification of the world's religions is a contentious topic, but the moniker “Abrahamic” has been applied to the religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam because they all trace their lineage to the prophet Abraham (Silverstein, Stroumsa, and Blidstein Reference Silverstein, Stroumsa and Blidstein2015). The Abrahamic religions are also combined together for other important reasons: they constitute the three main monotheistic traditions (Stark Reference Stark2001), they each have individual founders, and they are “religions of the book,” meaning they subscribe to one central text—in fact, their holy books build on one another. This emphasis on textual traditions means that doctrine and belief derived from the text are fundamental and central to the tradition. These are orthodox religions; the doctrine (doxa) is most important. All three traditions are also congregational religions and religious leaders (rabbis, priests, imams) play critical social roles for the broader religious community, and form a centralized power structure within the tradition and/or denomination.

Most of our basic definitions of religion and religiosity are influenced by an Abrahamic worldview. Common definitions of religion in political science, for example, tend to centrally focus on belief. Gill (Reference Gill2001, 120) describes religion as “belief systems that provide ordered meaning and prescribe actions.” In Toft, Philpott, and Shah's (Reference Toft, Philpott and Shah2011, 21) book, religion is said to have seven characteristics, beginning with belief in supernatural being(s). Grzymala-Busse (Reference Grzymala-Busse2012, 422) defines religion as “a public and collective belief system that structures the relationship of the individual to the divine and the supernatural.”

An Abrahamic bent also pervades how religiosity is measured, again beginning with an emphasis placed on belief. A classic measure of religiosity comes from the work of Glock (Reference Glock1962), who argued for five dimensions: belief, knowledge, experience, and practice (private and public).Footnote 9 Hill and Hood (Reference Hill and Hood1999) provide an exhaustive summary of various measures of religion used in social science, and the majority of them are focused on Christianity. Finke and Bader (Reference Finke and Bader2017; Bader and Finke Reference Bader and Finke2014) examine how to measure religion using the Association of Religion Data Archive's (ARDA) massive collection of surveys, but few of these focus on Asian traditions. Aside from belief, most existing religiosity metrics also stress the importance of attendance at religious services. One example of this is the debate over secularization in Britain, the subject of a small academic cottage industry.Footnote 10 One of the main issues in this debate is whether the rate of British churchgoing—the central measure of religiosity in this instance—has declined over the past several centuries, a question that has led scholars to carefully reconstruct measures of church attendance going back several hundred years.

While some components of the Abrahamic worldview translate to non-Western contexts, many do not. For example, consider the issue of god. Stark (Reference Stark2017) has argued that belief in god(s) is the central feature of all religions, but this view inaccurately represents religions like Buddhism and Jainism that were atheistic in their origins, as well as Hinduism, which had several atheistic schools. Another problem is the focus on belief. As Asad (Reference Asad1993) has famously argued, religion as belief is a specifically “liberal Protestant” view that is falsely taken to be universal. In many Chinese folk religions and in Shinto traditions, for example, there is a clear precedence placed on rituals. Some practices that remain central to Hinduism, such as nature worship or astrology, may appear strange to many mainstream Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Western world. While the Abrahamic traditions also have rituals, they are traditionally not considered to be more important or authoritative than the text, which is not true in many non-Abrahamic traditions. All of this suggests that studying and measuring religiosity in the Asian traditions requires different ways of thinking about religion, and Hinduism serves as a prime example of this challenge.

Measuring Hindu Religiosity

There are several reasons that Hinduism should be considered distinctive from the Abrahamic faiths:Footnote 11 it is not monotheistic,Footnote 12 has no single founder, no universal text, is non-conversionary, and is orthoprax rather than orthodox.Footnote 13 A few examples can illustrate the difference. It is not common to hear one call themselves a “Christian atheist” or “Muslim atheist,” but this would not seem strange in Hinduism, and in fact many of the orthodox schools (darsanas) of Hindu philosophy rejected the idea of a creator god (Chattopadhyaya Reference Chattopadhyaya1959). Likewise, attending church and mosque are central practices in Christianity and Islam, but, by contrast, temple worship is not compulsory in Hinduism.

At least since several Muslim dynasties reigned in north India during the medieval period, outsiders have struggled to understand the form, content, and boundaries of Hinduism. One of the earliest attempts to produce systematic knowledge of Hinduism came from the Muslim scholar Al-Biruni in the 11th century, who focused his exhaustive research on Hindu practices (e.g., life-cycle rituals), polytheism, as well as metaphysical concepts (e.g., reincarnation). During colonialism in the 19th century, the British began devoting significant resources to understanding Hinduism, viewing it largely through the lens of their own Christian heritage. Scholars (‘Indologists’) like Max Mu¨ller delved into the study of Sanskrit texts to understand the “classical” roots of Hinduism, whether or not these supposed roots had any connection to the modern religion.

In postcolonial India, there are still important debates about what exactly is Hinduism. For instance, some scholars argue that Hinduism connotes a Western construct and not a religion at all (see Smith Reference Smith1998 on this view). Significantly, this position has been embraced by the Supreme Court of India, which famously wrote in 1966 that:

When we think of the Hindu religion, we find it difficult, if not impossible, to define Hindu religion or even adequately describe it. Unlike other religions in the world, the Hindu religion does not claim any one prophet, it does not worship any one god, it does not subscribe to any one dogma, it does not believe in any one philosophic concept, it does not follow any one set of religious rites or performances, in fact, it does not appear to satisfy the narrow traditional features of any religion or creed. It may broadly be described as a way of life and nothing more.Footnote 14

Despite its enormous complexity, most existing survey work on Hinduism has tended not to stray too far from how Christian or Muslim religiosity is measured: in short, one is a pious Hindu if they pray and attend religious services. For example, research teams involving Leslie Francis have constructed indices to measure Hindu religiosity via surveys in London,Footnote 15 Karnataka (India),Footnote 16 and Bali.Footnote 17 These measures, however, were originally developed for Christian societies and then translated for Jewish, Muslim, and ultimately Hindu communities (Francis et al. Reference Francis, Santosh, Robbins and Vij2008, 612). Among political scientists, the main measures of Hindu religiosity come from NES questions on prayer, going to temple, fasting, and attending religious services (Chhibber Reference Chhibber1997; Reference Chhibber2014; Thachil Reference Thachil2014). Other studies, such as the WVS,Footnote 18 ask substantively similar questions.Footnote 19 But the NES was intended to study elections, not religiosity. The WVS built on the European Values Study, and therefore began from a European conception of religiosity.Footnote 20 Both of these surveys are also interested in standardization and comparison, but in a diverse religion like Hinduism, that means missing nuance and complexity.

A religious studies scholar or an anthropologist who works on Hinduism, for example, might be befuddled at existing surveys—both at what is included and excluded. I noted previously that temple worship is not a mandatory practice. Moreover, when Hindus go to temple, there is often no priest present or sermon to be heard. The NES and WVS might simply be assuming that temple worship is important because Christians go to church and Muslim (men) to mosque. Similarly, as Narayanan (Reference Narayanan2000) has argued, one of the most important aspects of Hinduism is auspiciousness (e.g., eating the right kind of lentils for a given occasion), a topic that gets scant attention on the NES and WVS questionnaires. My point is not that existing measures are wrong per se, but that they may lack “construct validity” and “face validity”—they may not, in short, accurately measure the concept they purport to measure (Cronbach and Meehl Reference Cronbach and Meehl1955; Nevo Reference Nevo1985). They also may not help us appreciate how Hinduism functions as an everyday religious tradition.Footnote 21 Not understanding what Hindu religiosity means, then, naturally complicates drawing connections between religion and political outcomes. I argue that the best way to investigate the issue of Hindu religiosity is to ask: what does being a Hindu mean to Hindus? And how do these self-understandings of Hinduism differ from our social scientific understanding?

METHODOLOGY

My methodological approach to answering these questions involves using a comparative survey design. One survey consisted of closed-ended questions about religion that are based on previous survey work done in India by the NES and the WVS. The second survey consisted of similar questions but open-ended. This allowed a comparison of our academic categories and conceptions of Hinduism to be contrasted with Hindu self-understandings. The two versions of the survey were then randomly assigned across and within two demographically similar villages in Bihar with a sample of 100 Hindus.

Survey Design

My survey focused on five conceptual areas: religious identification, intensity, rituals, beliefs, and customs. Religious identification is simply what term respondents use to describe their religion. Intensity refers to how respondents describe their personal level of religiosity. Rituals refers to Hindu religious practices, specifically things like puja, temple worship, fasting, etc. Beliefs refers to belief in god, as well as Hindu concepts like karma and reincarnation. Finally, I ask about customs because these are presumed to be secular—things like Hindu men wearing a long loincloth called a dhoti.

Formulating the open-ended questions was not simply a matter of copying the exact wording of NES or WVS questions, as this was not always possible. For example, the NES conducted a survey in 2015 in India on “Religious Attitudes, Behaviour, and Practices” that asked respondents in Hindi (literal translation): “How often do you do these things?” with a list that included several rituals like giving religious donations or fasting. That question wording is too broad to have been used in an open-ended format, however, so I opted to use a question that asked which “religious rituals” (dhaarmik rasmon) individuals performed. I tried to use the same language across both versions of the survey.Footnote 22

This point also highlights one major difficulty in undertaking these surveys, which was the issue of translation. This was an issue for even the most basic terms. For instance, in the Indic languages, there is no word strictly equivalent to “religion.” Dharma comes closest, and has in contemporary India become synonymous with religion, but it has a more expansive meaning: it is the root of Hindu moral identity, referring to both the Hindu cosmic order and the “duty” or “correct practices” of individuals (determined by caste, gender, or life-stage) to maintain that order. Another example is the word “puja,” which is used in the NES and WVS surveys and translated as “prayer.” But puja is more expansive than prayer in the Christian or Islamic sense, and is better translated as worship (Michaels Reference Michaels2004, 227). Prayer is one of the many components of puja. I discuss my specific question translations in subsequent sections.

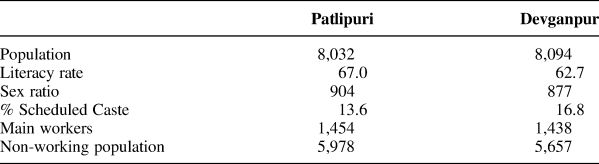

Sampling Procedure and Enumeration

I employed the Indian survey firm Across Research and Communications, and the survey team consisted of one manager and four enumerators. Everyone had experience conducting surveys previously, and I oversaw their training, including piloting the questions, in the days prior to the survey's implementation. Bihar was chosen as the location for this project because its Hindu demography is similar to India's as a whole—around 82% Hindu while the national average is around 80%—and because it has a number of important Hindu pilgrimage sites. I also chose to conduct the survey in a village setting because close to 70% of India's population lives in rural areas. I selected the villages of Patlipuri and Devganpur,Footnote 23 located roughly an hour away from the state capital of Patna. Though the Indian government does not make village-level religious demographic information available, a field site visit determined that both villages were made up overwhelmingly of Hindus. I selected these two villages because they are similar on a number of factors—population, literacy rate, sex ratio, percentage of Scheduled Castes,Footnote 24 and occupational status, as shown via 2011 Indian Census data in Table 1. The caste breakdown of the survey is shown in more detail in Table A4; both villages had a mix of different castes, which enabled me to learn about a diversity of viewpoints, as well as move beyond standard “Brahminical” (the most elite caste) views of Hinduism.

Table 1. Field sites

I selected these two similar villages to ensure that drawing a random sample from both would create comparable groups. Aside from these reasons, these research sites were also beneficial because of their proximity to Patna, which meant that the villages were not too remote and cut off from outside influence. These locales featured a mix of people who worked entirely in the village as well as those that traveled to Patna on a semi-daily basis.

The survey assignment (closed- or open-ended questions) was randomized both within and across the two villages. That is, each village was given roughly 25 closed-ended and 25 open-ended surveys.Footnote 25 We began in Patlipuri, and each enumerator was given a random mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions in a packet, with the instruction to deliver whatever version came next in their enumeration. Only Hindu homes were surveyed; all others were excluded from the sample. Because a good number of men worked outside the village, this ensured that Hindu women were included in the sample. It has been noted that a female perspective is often marginalized in studies of religion, especially Hinduism (Narayanan Reference Narayanan2000). Using a random sample (more on the specific enumeration procedure below) taken from both field sites yielded two groups, displayed in Table 2, that are quite similar in several respects, although with some important differences. Both survey samples were similar in average age, caste rank,Footnote 26 income, and health, all of which are standard covariates used in the study of individual-level religiosity. Two notable differences were that more women were included in the closed-ended sample, and these respondents also had, on average, a lower level of education.

Table 2. Comparison of random samples

The first step of the survey enumeration was to produce a Google Earth image of each village, shown in Figures 1 and 2, to discern their geographic layouts. A local landmark—a large middle school—was chosen as the starting point of the survey (denoted by the white building in the top right in Figure 1) in Patlipuri. A main road curved through the entire village, and enumerators began at the middle school on the first day of fieldwork and worked down this road and side streets, knocking on each 8th door (chosen as proportionate with the number of households needed from the village population, and to ensure spatial diversity). The next day they began again on the main road (where they had left off previously) and used the same method. In the case that someone was not home, they were instructed to try to do a survey at the house on the left, then the right. In Devganpur, as Figure 2 shows, there was no main road but rather a number of small streets that went into the village. Enumerators began off the highway and combed down several of these small thoroughfares in both directions, using the same procedure described above.

Figure 1. Patlipuri village

Figure 2. Devganpur village

The survey occurred over 5 days, and the team was usually in the village from 11 AM to 4 PM. I personally worked with the survey team during all 5 days, and therefore was able to gauge how respondents perceived the questions and whether or not they understood them. Enumerators began by asking to speak with the head of the household, then the next oldest person available (over the age of 18) if the household head was not home. All interviewees were given a copy of the informed consent form, were explained the topic of the survey and all procedures, and verbal consent was received before the survey began. The overall response rate for the survey was very high at 93%, which I attribute to both the small sample size and the fact that religion is a common topic of everyday conversation in India.

FINDINGSFootnote 27

Before discussing the results of the survey, one important overarching point to note is that almost all respondents struggled to understand the open-ended responses. This was something I witnessed repeatedly, and was a surprising finding. I had expected that most respondents would at the least understand key terms like “ritual” or “belief,” and this made interpreting responses much more difficult. This also posed practical problems. If the survey was open-ended, enumerators were instructed to explain any question at length that a respondent did not understand, but they were told not to provide examples of responses. For instance, if a respondent did not understand the question: “How religious would you say you are?” rather than provide an example of a standard response—“Some people say they are very religious”—the enumerator said something along the lines of, “Imagine you meet a new person in the village who is Hindu. How would you describe how religious they are? Now, how would you describe yourself in comparison?” However, during the piloting, enumerators stated that respondents still did not understand the questions, so they were therefore allowed to provide one example, albeit indirectly. For instance, if a respondent did not understand what was meant by a religious ritual, the enumerator might mention that the respondent's home contained a puja shelf (where small idols or images of deities are located) in order to provide assistance. As another example, if a respondent did not understand what a religious belief was, but had earlier said they do puja, the enumerator would say, “You do puja, so does that mean you believe in god?” I showcase the results of my survey in the following subsections, concluding with a discussion of some general observations of the survey enumeration in the field and implications for future research.

Religious Identification

The first question for all respondents was: “What is your religion (dharma)?” All respondents in the closed-ended survey recorded their religion as Hindu when given this option. In the open-ended survey enumeration, all of the respondents also used the term Hindu except for one (upper-caste) man who used the term sanatana, which translates as “eternal.” This is a reference to another name given to Hinduism: the “eternal religion” (sanatana dharma). While this specific term dates back to medieval Hindu literature, it has an ambiguous meaning, and was popularized by Hindu movements in the 19th century that were orthodox and opposed to reform (Warrier Reference Warrier2003, 238, fn. 37).

Intensity

One of the most common ways of measuring religiosity is to simply ask respondents how religious they are. I used the following closed-ended question and responses: “How religious (kitnaa dhaarmik) would you say you are? (3) Very religious, (2) Somewhat religious, (1) Not at all religious.” This question and the responses are based on the 2015 NES religion survey, and the WVS asks a similar question about whether one considers themselves a “religious person.” Among the closed-ended sample, the average score was 2.43, indicating that most respondents viewed themselves as religious. In fact, only one respondent—an 18-year old male—gave the response “Not at all religious.”

The open-ended version of this question was not understood by most respondents. Being asked to describe and judge their own religiosity did not seem to make intuitive sense. The exact open-ended responses were as follows: “Very” (24), “Very 100%” (1), and “Somewhat” (24). But these answers are still difficult to interpret. Uncertainty around this question may have been caused by the fact that the term dhaarmik can also mean “virtuous” or “moral,” and therefore many respondents may have wanted to answer modestly. Overall, however, the way religious intensity is measured by surveys did not seem to be matched by any analogous local way of thinking about the topic.

Religious Rituals

Hinduism is often described as an orthoprax religion because of its extensive litany of rituals. As many scholars of Hinduism have taken pains to note, practice takes precedence over belief. The NES asks a question about what respondents do, but in an open-ended format, the term “ritual” had to be used. Translating this term was difficult, and I opted for dhaarmik rasmon, literally religious rituals, rites, or ceremonies. For the closed-ended survey, I used the same responses from the NES question: visiting temple, participating in religious performances (like kathas, the recitation of religious stories), giving religious donations, keeping fasts, visiting other sacred sites (like a shrine), consulting pandits (priests or religious scholars), and consulting vastu (architectural) experts (who design buildings in accordance with Hindu precepts). Because I was not completely sure a priori what rituals people followed or how they would define this term, I also added three additional options that have been mentioned in many books on Hinduism: puja, darshan (seeing the image of the divine),Footnote 28mantras (a hymn or word repeated during rituals). Table 3 below displays the top five closed-ended and open-ended survey responses.

Table 3. Hindu rituals (top five answers)

Puja is clearly the most important ritual in these villages, mentioned overwhelmingly by Hindus in both samples. Beyond that, however, there are not many other similarities. Giving religious donations, visiting temple, participating in religious performances, and consulting the pandit were all noted by over 88% of the closed-ended sample. These are the things that Hindus report doing on a regular basis. But none of those answers was common among the open-ended sample. Instead, Hindus given the open-ended survey mentioned other rituals, such as celebrating festivals, or rituals dealing with their attire: wearing kalawa (a red thread on the wrist), dhotis, and putting sindoor (a mark of red powder) on one's forehead (for married women). Fasting and going to temple were mentioned, but quite infrequently. Another ritual listed was obeying parents/worshipping ancestor deities (usually mentioned together).

One important caveat here is to not misinterpret the large disparity between the percentages across both versions of the survey. In the closed-ended survey, for example, roughly 88% of the respondents stated that they took part in religious performances. In the open-ended survey, no one mentioned anything about these performances. This does not mean that these respondents do not partake in these activities, however. It could be the case that respondents did not instinctively think of this as a ritual, or (given their general confusion about the questions) were not sure if this should be listed as a ritual. Alternatively, it could also be the case that respondents given the closed-ended version of the survey were satisficing, i.e., inflating their religious practices (Krosnick, Narayan, and Smith Reference Krosnick, Narayan and Smith1996).

Religious Beliefs

The next survey question dealt with religious beliefs, translated literally as: “religious things (dhaarmik baton) you believe in.” It is true that in Hinduism ritualism takes precedence over belief, but this should not be taken to mean that beliefs are unimportant. I asked respondents about their belief in the following things, based on an NES survey question: sun sign/astrology, reincarnation, life after death, ghosts, and jinn (spirits or supernatural beings in Islam). I also offer additional responses based on a similar WVS question: belief in god and the soul. Finally, I added two entirely new items I have often seen mentioned in books on Hinduism: belief in karma and the evil eye (Michaels Reference Michaels2004).

Table 4 details that, in the closed-ended sample, Hindus believed in karma, god, the soul, astrology, and the evil eye, all mentioned by over 50% of the population. The top answers for the open-ended sample also include god and karma. Although atheism and Hinduism are compatible, practically speaking, the respondents from both villages were overwhelmingly theistic. Some of the additional responses that emerged in the open-ended sample were a belief in puja (ostensibly a ritual), reading scripture, parents/ancestors, and worshiping the tulsi plant, an Indian variant of the basil plant that is considered holy.

Table 4. Hindu beliefs (top five answers)

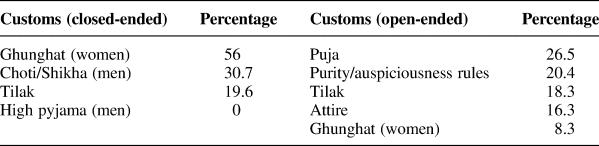

Customs

The final question involved customs (riiti-rivaaz, without the word religious preceding it),Footnote 29 which I included because it is presumed to be a secular category. Scholars who work on Christianity, for example, have often analytically divorced Christian beliefs from the broader culture of society. However, as other scholars have pointed out, the line between what is religious and what is a custom is not at all clear in Hinduism (Singer Reference Singer1972, chapter 5). Many of the customs that, in Western traditions, are considered secular—what one wears, their appearance—may be considered religious in the Hindu tradition. This question is based on an NES question, and it offers four responses. The first is only for women: ghunghat, or veiling, a Muslim tradition that became adopted and indigenized over time by Hindus. The next two are only for men: wearing a choti (keeping only a small tuft on hair on the back of one's head), and wearing a high pyjama (a South Asian form of loose-fitting pants). Wearing a tilak (a mark worn on the forehead) was the final option, which can be done by men and women.

Table 5 showcases that none of the listed customs was done by a majority of Hindus in the closed-ended sample except veiling. Furthermore, the only closed-ended responses that also appeared as common open-ended responses were veiling and wearing the tilak. In the open-ended format, puja was the most common response, clearly a religious activity. Other common responses included those dealing with issues of purity/pollution and auspiciousness/inauspiciousness, central features of Hinduism (Srinivas Reference Srinivas1966; Narayanan Reference Narayanan2000; Michaels Reference Michaels2004). For example: not getting one's hair cut on inauspicious days, and shaving one's head and not entering a temple after the death of a family member. Respondents given the open-ended survey also mentioned attire, but in different ways than the closed-ended responses: for example, women mentioned wearing bangles, anklets, and putting colored dye on their feet. Some of the answers for customs were also described by respondents as rituals. Puja was mentioned by more than 70% of the open-ended sample as a ritual, but also by 26.5% as a custom. Attire was mentioned by 20.4% of the sample as a ritual and 16.3% as a custom. Fasting (16.3% as a ritual) was also listed as a custom (6.1%). Overall, the open-ended responses clearly indicate that the term custom was not viewed as distinct from religion.

Table 5. Customs (top five answers)

Gender and Caste Dynamics

As many scholars have noted, Hindu religiosity is mediated by two important factors: gender and caste (Narayanan Reference Narayanan2000). Women and men often have very different religious experiences, and some religious practices are tied to specific castes. Therefore, I broke all survey responses down by these two subgroups. Because of space limitations, these tables appear in the Appendix. Tables A1–A3 begin by showing the closed-ended and open-ended responses (religious rituals, religious beliefs, and customs) broken down by gender. Note that the subgroups are very small, so limited inferences should be drawn from these tables. Tables A1 and A2 show similarities across gender in the closed-ended version of the survey, but some important differences in the open-ended version. Women were more likely to mention fasting and going to festivals as rituals; likewise, they were less likely to emphasize belief in god and karma.

The survey responses were then broken down by caste, which is a social hierarchy of endogamous birth groups traditionally tied to specific occupations. Table A4 lists all of the castes included in the survey as well as their self-reported ranking, which was verified using official lists from the Bihar government. Castes were ranked into three groups. First, “General Castes” are the three castes at the top of the hierarchy: Brahmins (priests, educators), Kshatriyas (rulers, warriors), and Vaishyas (artisans, merchants). The other groups are “Other Backward Classes” (OBCs; mainly the Shudras, laboring castes) and “Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes” (SCSTs; the former untouchables and the poorest tribal communities). Yadavs, a politically-influential OBC caste in Bihar, were the largest surveyed group and constitute 40% of the sample.

Tables A5–A7 display the closed-ended and open-ended responses ranked by caste. Rituals and beliefs in the closed-ended sample do not appear to differ much across caste groups, but there are some differences in customs: groups lower on the caste hierarchy are less likely to wear the tilak, veil (women), and wear the choti (men). The open-ended sample displays some interesting differences among caste groups. Attire was mentioned more often among the general castes, and puja was rarely mentioned among SCSTs. In terms of beliefs, general castes were the only group to mention ghosts. Across both rituals and customs, general castes were more likely to mention rules about purity and auspiciousness. Finally, regarding customs, general castes were much more likely to mention their attire.

Table A8 then displays responses for Yadavs, as this group has had a long history of “Sanskritization” (Srinivas Reference Srinivas1952), a term connoting the process of lower castes mimicking the habits and customs of dominant castes in order to improve their social status. As Table A8 shows, Yadavs do have certain similarities with higher castes: they mention rules about purity and auspiciousness (as rituals and customs) in the open-ended version of the survey.

Discussion and Implications

As I noted at the outset of this article, the results of this comparative survey are messy. However, there are some broader points to take away, especially from the open-ended answers. In terms of religious identification, the term Hindu is widely used in these villages, but even this was not universal. In terms of religious intensity, this question provoked widespread confusion. This calls into question self-reported measures of religiosity in Hinduism, as many respondents did not seem to be making these distinctions (e.g., “somewhat religious,” or “very religious”) internally. With regard to religious rituals, the term in Hindi provoked considerable confusion, and many respondents did not know what to say. Temple worship, considered so important in surveys of Hinduism, was rarely mentioned among respondents who received the open-ended survey. There was also a large disconnect between Hindu beliefs in the two versions of the survey. This suggests that Abrahamic “belief-centered” views of religion are not easily applicable to Hindus, as beliefs seem to be quite fluid in Hinduism. Finally, there was no clear sense that “customs” indicated a secular category, as many of the customs listed in the open-ended survey seemed to be religious in character.

So what does this survey reveal about how respondents think about Hinduism? Of the four main survey questions that have been used to measure Hinduism from existing political science research—frequency of prayer, going to temple, participating in religious services, how often individuals keep religious fasts—I would argue that only puja seems to be widespread. Going to temple and fasting were not important to most respondents, and “religious services” is too broad to have any real meaning. As for what is missing from existing surveys, Hindus seem to care about belief in god (despite the unique possibility of Hindu atheism), and some of them place importance on their attire, diet, and rules about purity and auspiciousness.

Given these findings, how should we approach surveys on Hinduism going forward? I will mention three broad areas of inquiry scholars should explore, but they are certainly not exhaustive: future surveys should take into account theism; the relationship of Hindus to their family, ancestors, and community; and whether Hindus obey norms governing purity and auspiciousness. First, existing surveys like the NES do not ask questions about god(s). But almost all of the Hindus I spoke with were theists. Future surveys should ask Hindus whether they believe in god(s), and also which god(s), as there may be differences by sect. By including these questions, future studies can also explore how Hindu theism compares and contrasts with Abrahamic theism.

Second, future surveys should explore community-level norms that may govern religious groups and act as a way of maintaining boundaries (see Pepinsky, Liddle, and Mujani Reference Pepinsky, Liddle and Mujani2018, chapter 2). Hinduism is an ethnicized religion rather than a universal religion like Christianity or Islam, and that must be accounted for in surveys. For instance, one open-ended survey respondent listed marrying someone of the same religion as an important ritual, and this suggests that future surveys should ask questions about whether respondents would consider having an interreligious—and an intercaste—marriage. Future surveys could also ask parents whether they believe it is important to teach their children about Hinduism. This question would be valuable because so many respondents in the open-ended version of the survey mentioned obeying parents and ancestors. In fact, many younger respondents (when the head of the household was not home) told me that they knew less about religion than their parents or grandparents, who were considered the family authority.

Finally, future surveys need to grapple with issues of purity and auspiciousness, two distinctive features of Hinduism. For example, Hindus could be asked about temple entry: e.g., would you enter a temple after someone in your family died (an impure time)? Or: do you believe that you need to consult with a pandit or astrologer before selecting (an auspicious) wedding date? That certain things are pure or auspicious is a well-known fact in the Hindu worldview, but existing surveys are not capturing this key set of beliefs.

One additional point is that Hindu religiosity is, as I mentioned earlier, mediated by gender and caste. This does not necessitate, however, having separate measures of religiosity for men and women, high and low castes, or even divorcing individual-level piety from community-enforced norms. Rather, what we need is a scale of Hindu religiosity but an inclusive one: it should try to capture the behaviors, beliefs, and sense of community belonging prevalent among men and women, as well as different caste groups. For instance, fasting is more important to women, but obeying parents is more important to men. Similarly, attire is more important to high-caste groups, but this is not as true for low-caste groups. Questions on all of these issues can, when combined together, be meaningful for understanding Hindu religiosity across a broader population.

My findings in this article also have important political ramifications. Given that we do not yet have a convincing measure of Hindu religiosity, studying its effect on politics—voting behavior, the rise of Hindu nationalism, etc.—is a precarious task. To illustrate what I mean, existing measures of Hindu religiosity place importance on going to temple, yet my work in these Bihari villages indicates that very few Hindus considered this an important practice. It may be that going to temple is simply a social event that lacks religious significance. Therefore, going to temple being uncorrelated or weakly correlated with the rise of the BJP—one of the more important recent political developments in India—may be a spurious finding. But if we measure Hinduism differently—for example, via norms about obeying your parents or marrying within the community—it is possible to see how Hinduism could be linked to voting for the BJP, as the party often tries to mobilize Hindus by pledging to protect the religion from “outsiders” (e.g., Muslims or Christians). Future research could use new individual measures—for example, caste-maintaining practices—and see if they correlate with the BJP vote, or could develop new scale measures that include a wide variety of beliefs and practices prevalent among Hindus to see how that correlates with religious voting.

Just as I suggest we try to contextualize our understanding of Hinduism via survey questions, we should likewise contextualize our understanding of Indian politics in the questions we ask. One of the most important political issues in India today is the future of secularism. But the Indian model of secularism is quite different from the American model (separation of church and state) and the French model (diminishing religious influence in the public sphere). The Indian model of secularism is about (a) “principled distance” (Bhargava Reference Bhargava2010), i.e., maintaining a distance (but not a wall) between the state and religion, and (b) dharmnirpekshta (“religious neutrality”). Therefore, to gauge how Hindus feel about politics requires more than just asking about “secularism,” a term with which some may not even be familiar, but rather asking whether they support specific policies: the equal treatment of all religions, and whether the government should support the maintenance of temples and non-Hindu religious sites like mosques and churches.

CONCLUSION

While Max Weber is best known for The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Reference Weber1905), it is less widely known that in 1916 [1958], he wrote an intriguing book called The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism. In it, he tried to explain why India had not had its own industrial revolution (he also wrote a book on China examining the same topic). Weber argued that those who followed Hinduism and Buddhism were too otherworldly and focused on the next life to have spurred the development of capitalism. Weber (Reference Weber1958, 118) noted that:

All Hindus accept two basic principles: the samsara belief in the transmigration of souls and the related karman doctrine of compensation. These alone are the truly “dogmatic” doctrines of all Hinduism, and in their very interrelatedness they represent the unique Hindu theodicy of the existing social, that is to say caste system.

Weber, however, had never visited India, and his rather anemic view of the Hindu religion was based on the reading of classical Sanskrit texts that discussed and debated belief in the high concepts of karma, rebirth, and reincarnation. Several decades later, the anthropologist Edward B. Harper went to India to study village religious life. He noted (Harper Reference Harper1959, 229) a quite different story from Weber's account: the “lower castes,” he pointed out, “frequently were completely unfamiliar with the term for, as well as the concept of, rebirth (punarjanma).”

This anecdote highlights the danger of taking preconceived notions of what religion is and using them as the basis for social scientific measures of religiosity. Weber's belief-centered view of Hinduism, based largely on his Christian understanding of what constituted religion, was completely unrelated to the Hinduism of the Indian masses. This is what Narayanan (Reference Narayanan2000) has termed the “diglossic” nature of Hinduism: Weber's view focused on liberation while most Hindus focused on lentils.

This article has attempted to provide an ethnographic perspective of what Hinduism is by asking Hindus themselves. While the study of religion has become a growth industry in political science, it is still overwhelmingly dominated by the study of the Abrahamic religions, just as it was in Weber's day. We have ample studies of belief and doctrine focused on a wide range of Christian and Muslim societies, but much of what constitutes religion in the Abrahamic faiths gives us less insight into the popular Asian traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, or Chinese folk religions.

Using a comparative survey design, I randomized closed-ended and open-ended questions about religious identification, intensity, rituals, beliefs, and customs across a population of 100 Hindus taken from two similar villages in the north Indian state of Bihar. This allowed a comparison of our academic understanding of religion with the self-conceptions of Hindus, and the surveys revealed some major disparities between the two. My three major findings can be summarized as follows: (a) many respondents did not understand the open-ended questions, even terms as basic as religious rituals or beliefs; (b) many respondents did not differentiate between a ritual, a belief, and a custom; and (c) many respondents thought of their religion in ways that are much more expansive than Christian or Muslim conceptions of religion.

Beyond the Indian case, this article makes two broader contributions to the study of religion in political science. This survey of Hindus clearly demonstrates that many (although not all) of the metrics that have been used to study religiosity in Abrahamic contexts do not easily translate outside these contexts—in fact, they may not even work in all Abrahamic contexts. Taking religion seriously in political science means not overlooking influential traditions like Buddhism and Hinduism while simultaneously recognizing that studying these religions will require a broader way of thinking about what religion is and how we should measure it. A related point here is that this study should not be taken to mean that Hinduism is incomparable to the Western religions, a perspective that led the Indian Supreme Court to deny that Hinduism was even a religion at all. But the court's logic does not prove that Hinduism is not a religion—only that it does not conform to Abrahamic conceptions of religion that are taken to be normative. My opinion, in contrast, is that Hinduism is different but not dissimilar from the Abrahamic faiths. Future survey work must recognize but not reify this difference.

Finally, this survey shows that scholars should pay attention to issues of translation, context-specificity, and self-understandings of religion. Many of the most basic terms that we use in social science present translational difficulties for non-Western cultures, including the term religion itself. Many of the things we assume religious people do and think may not correspond to life on the ground. Without engaging with other cultures on their own terms, thinking through translation, recognizing that some religions rely on dispersed authority and therefore contain a broad range of beliefs and practices, and observing how religion operates in everyday life, scholars run the risk of clinging to misconceived notions of what religion means, and, by extension, how it influences political behavior.

Appendix: Questionnaires

Closed-Ended Questions on Religion

1. What is your religion?

a. Hindu

2. How religious would you say you are?

a. Very religious, Somewhat religious, Not at all religious

3. Do you perform the following rituals (rasmon)?

a. Puja

b. Visiting temple

c. Participating in kathas/sangats/bhajan-kirtans/jalsas

d. Giving donations for religious activities

e. Keeping fasts, rozas

f. Visiting shrine/mazar/sacred tree/animal

g. Consulting pandit/maulvi about auspicious timing

h. Consulting vastu experts

i. Darshan

j. Reciting mantras

4. How much do you believe in the following things (baton par vishwas karte hain)?

a. To a great extent, To some extent, Not at all

b. God

c. Karma

d. Sun sign/astrology

e. Reincarnation

f. Life after death

g. Soul

h. Evil eye

i. Ghosts

j. Jinn Jinnat

5. Do you perform the following customs (riiti-rivaaz)?

a. Wearing a ghunghat

b. Keeping a choti/shikha

c. Wearing a high pyjama

d. Going outside home with a tilak on forehead

Open-Ended Questions on Religion

1. What is your religion?

2. How religious would you say you are?

3. Which religious rituals (dhaarmik rasmon) do you perform?

4. Which religious things (dhaarmik baton) do you believe in?

5. Which customs (riiti-rivaaz) do you perform?

Table A1. Hindu rituals by gender (top five answers)

Table A2. Hindu beliefs by gender (top five answers)

Table A3. Customs by gender (top five answers)

Table A4. Caste groups in the survey

Table A5. Hindu rituals by caste group (top five answers)

Table A6. Hindu beliefs by caste group (top five answers)

Table A7. Customs by caste group (top five answers)

Table A8. Hindu religiosity of the Yadavs (top five answers)