In the early 1900s, a young woman called Siranush Shirinyan lived in the town of Sivas, in central-eastern Anatolia, where she worked as a carpet weaver in Albert Aliotti's carpet factory. She was born in Sivas in 1898, barely two years after anti-Armenian violence had swept the entire region. One of eight siblings, the violence of 1896 left her father unable to work, so the responsibility for the family's subsistence fell primarily on the young shoulders of Siranush and her three older sisters, who stayed at home to work as weavers. Siranush began working to earn a crust at the age of eight – not especially young for the period – when she went to carpet magnate Albert Aliotti's factory, recently established in the city.Footnote 1 Siranush thus became just one of many Armenian girls and young women in Sivas whose labour became the main source of income for the violence-stricken community.

While keeping in mind the stories of Siranush and many other Armenian young women and girls, in this article I shall examine the relationship between violence and different labour regimes and the discourses built around them in various regions in Anatolia after the anti-Armenian violence in the late Ottoman Empire, before World War I. The violence was one result of complex developments in the context of an Ottoman state that was modernizing and centralizing, and of the deeds of various social actors in the second half of the nineteenth century. It included social, economic, demographic, and diplomatic dimensions, which stemmed from the power vacuum in the regions inhabited by the Armenians and was affected by the period's increasing militarization. Moreover, an Armenian mercantile bourgeoisie was on the rise, replacing older hierarchies, and Armenians were increasingly criminalized in state discourse and practice. All that had the effect of transforming the “Armenian Question” from a diplomatic to a socio-political matter, ultimately only to be “solved” during World War I.

The gendered political economy of the geography of anti-Armenian violence is under-examined, despite the expanding scholarship on such topics as the dynamics of ethnic violence in 1895–1896 and in 1909,Footnote 2 land grabs and the transfer of capital from Armenians to other groups,Footnote 3 how women were affected by mass violence particularly during World War I and how they recovered from it,Footnote 4 Armenian orphans and the struggles over their bodies,Footnote 5 and the discussion of anti-Armenian violence in Ottoman-Turkish historiography.Footnote 6 In this article, I aim to analyse the reconstruction of Armenian communities after ethnic violence as a constant characteristic of broader Ottoman social and economic history. I will seek to establish a relationship between violence, the expansion of markets and global commodity chains, and to understand how and why the Ottoman economy's “reindustrialization” – that is, the growth in its manufacturing output after a period of decline – coincided with the destruction wrought by mass violence in the final decades of the empire's existence. To answer the question, I investigated the rise of oriental carpets as the most important commodity and the one manufactured in the most labour-intensive way and by the greatest proportion of women. I considered the question primarily in relation to the geography of anti-Armenian violence in the late Ottoman Empire, and I believe that the rise in production of oriental carpets and their emergence as a global commodity were firmly linked to market-based efforts to reconstruct the violence-stricken Armenian communities in Anatolia. While gaining relative power in their communities thanks to their central role in the expansion of the trade, Armenian women and children in post-violence communities were simultaneously integrated into the global market for oriental carpets as a cheap but vulnerable and organizationally weak workforce. The process of their incorporation into that market, justified in the name of improving disadvantaged lives, was similarly closely associated with changing definitions of the work ethic and morality, and reproduced women's and children's subordination to social and economic hierarchies beyond their immediate reach.

CARPET-MAKING AND FEMALE LABOUR IN THE LATE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

The history of the Ottoman economy in the nineteenth century has been examined mainly from the perspective of the integration of Ottoman markets into the European economic core.Footnote 7 According to that paradigm, by signing free-trade treaties with the Great Powers from the late 1830s onwards the Ottoman Empire, like other non-Western players, opened up its markets to European merchandise – but to its own disadvantage.Footnote 8 Small and artisanal production collapsed in the face of the influx of European goods that entered the Ottoman market with the benefit of the favourable tariffs of the trade treaties. The Ottoman economy did, however, learn to adjust enough for the downward trend in manufacturing to have slowed by the 1860s, but it was able to “reindustrialize” only from 1896 after the end of the economic crisis.Footnote 9 Reindustrialization consisted of increasing output and growing numbers of employees in poorly capitalized manufacturing sectors driven by low technology, particularly in textiles, silk thread-making, and the weaving of oriental carpets, all of which were labour-intensive industries employing large numbers of women.Footnote 10

Currently accepted explanations for that phenomenon are based on classical economic theory with its firm belief in equilibrium between supply and demand, a “free” labour force, and the labour theory of value. They emphasize the rising demand at the time from Europe for carpets and technological and organizational developments in production. Econometric explanations claim that the import of yarn, which relieved women from spinning, created an excess of labour which could be employed in weaving.Footnote 11 Some argued, too, that certain characteristics of the Ottoman manufacturing sector played a role in its reindustrialization, mainly its interdependence with the agricultural sector's labour market. By the end of the economic crisis in 1896, therefore, falling agricultural prices might have led excess agricultural labour to move into manufacturing, resulting in an increase in output. However, such purely economic explanations disregard the interwoven relationships between elements such as local context, market relations, and cultural understanding of work and female labour in the period. That disregard has come about despite parallels with the well-discussed scholarship on post-1980s Turkey, where political economy and gender are once again at the centre of analysis.Footnote 12 Moreover, a preconceived understanding of the Ottoman Empire as an agrarian economy leaves such approaches failing to seek any explanation for the role of the urban economies, which were the real motive force behind the reindustrialization of the Ottoman economy. My examination of late-Ottoman-Empire carpet production therefore not only historicizes those relations but, more importantly, approaches the economy of the late Ottoman Empire as something ingrained in Ottoman society, both shaping and shaped by local social and cultural dynamics while interacting closely with global trends.

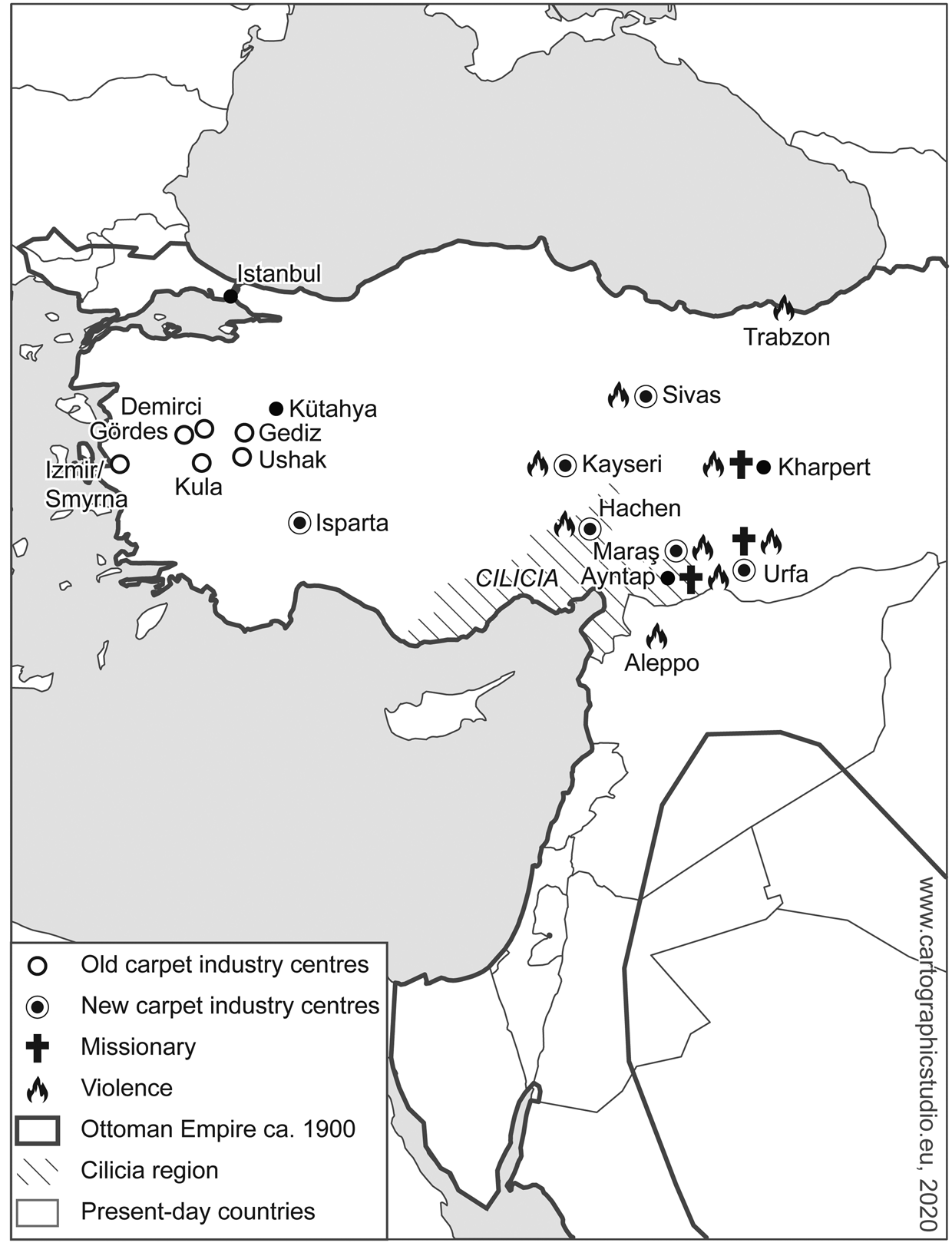

Carpets have been considered the commodity that best exemplifies the trends mentioned above, with their workshop- and home-based manufacture and chiefly female production. Production of carpets in the late Ottoman Empire grew in a context of closer trade with Western markets during the second half of the nineteenth century, and by that century's end carpets had become the empire's leading manufacturing export. In the early days, as exports rose, the “traditional” carpet centres in western Anatolia – chiefly Ushak, which had been associated with carpet weaving and export to Europe for centuries, but also including Gördes, Kula, and Demirci – were prominent in the market, and Izmir/Smyrna was the chief port from which carpets for export were despatched.Footnote 13 However, on closer examination production figures show that while the Ottoman Empire's rug exports grew from 1,000 bales in 1857 to 8,800 in 1913, the centre of gravity of production shifted eastwards, away from western Anatolia (Figure 1). In that period, the proportion of carpet exports accounted for by Ushak declined from 77 per cent in 1873 to 23 per cent in 1910, while total exports reached unprecedented heights, and the labour force employed in carpet-making in central and eastern regions of the empire grew unprecedentedly.Footnote 14 New carpet-weaving centres emerged in a number of places in Anatolia in the late nineteenth century and particularly in the early twentieth, while the importance of the historic production centres diminished.

Figure 1. Traditional carpet production centres in the Ottoman Empire and the centres established in the Armenian inhabited districts following mass-violence in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Current scholarship explains the expansion of carpet weaving into new regions as the result of more efficient production methods introduced by multinational foreign enterprises in response to growing demand from the European and American markets. European and particularly British capital held the dominant position in the organization and production of oriental carpets as London combined with Istanbul as the hub for the European and the US markets.Footnote 15 Among European capitalists the efforts of the London and Smyrna-based Oriental Carpet Manufacturers, Ltd. (OCM) and its financial networks to standardize, control, and dominate carpet production are well documented.Footnote 16 Yet, that explanation, which heavily prioritizes the role of foreign capital in the organization and stimulation of global interest in the trade in oriental carpets during the late 1890s and early 1900s, fails to address certain of its aspects, leaving out of account the growing number of Armenian carpet dealers both in Europe and the US with direct links to local markets and producers in their native land.Footnote 17 Moreover, and, more relevantly, to the thrust of this article, no current scholarship addresses the local conditions that prepared the ground for foreign firms like OCM, which was established in 1908. The question remains therefore unanswered of whether it was mere coincidence that newly emerging carpet-weaving cities like Sivas, Kayseri, Urfa, and Cilicia in eastern-central and southern Anatolia were all heavily Armenian-populated regions, all of which were hit by anti-Armenian violence in the late 1890s and early 1900s.

I would argue that, in the late Ottoman Empire, the oriental carpet sector, which included various actors such as local and regional merchant-entrepreneurs, multinational companies, and transnational actors, such as missionaries, began to intertwine with society both to promote trade and to offer solutions to the ills arising during post-violence reconstruction. What I have observed for the period after 1896, and again after 1909, in Anatolia is similar to what we now call “disaster capitalism”. In the Ottoman case, certainly, unregulated markets and rampant exploitation of human and material resources, coupled with economic and financial weakness, created both the material institutions and discourses for acceptance of the private sector's role in the recovery of post-disaster Armenian communities.Footnote 18

The role of violence in the creation of a vulnerable female labour force and new relationships of production was by no means unique to the Ottoman Empire, for places like Morocco, Bosnia, and the south-western US of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries offer comparable cases of close relationships between violence, expansion of markets, and accompanying discourses. Anthropologists, ethnographers, and – although to a lesser degree – historians have examined the transformation of native/local crafts in those regions in the age of colonialism into museum artefacts displayed around the world, as representative of conquered cultures.Footnote 19 In the US context, the relationship between violence and the development of capitalism in certain regions is equally evident. Navajo textiles, for instance, are the most prominent example of such connections, being transformed from essentially native goods to “Indian-made” commodity; first violence and then the ensuing systemic poverty among the Navajo completely altered relationships of production among the native tribes as they were exposed to the forces unleashed by the expanding US market.Footnote 20 Thus, following major social and political transformations, such objects were commodified to serve the growing appetite of the European and American white middle classes for “authentic” goods originating from “others”.

However, unlike the cases of France, Austria-Hungary, and the US, the Ottoman state was not a strong state with expanding power; rather, its role in the expansion of oriental carpet production after instances of violence was limited primarily to regulating – or more often to not regulating – new market relations, and to providing favourable legal and trade conditions such as low trade tariffs, and welcoming investments and certain economic and social institutions in the provinces. Thus, by examining hitherto unused Armenian local sources, business magazines and newspaper accounts, committee reports, and testimonies of survivors of mass violence, this article tells a story of capitalist development in the Ottoman Empire from the perspective of various non-state Ottoman actors who participated in the reconstruction of the post-violence Ottoman economy. Although the article does not provide an overarching history of carpet production, it will draw on cases from different regions over a period of two decades in the midst of the expansion of the sector to show the intricate relationship between violence and capitalism, and the central role of female labour in the economy of the late Ottoman Empire.

CARPET WEAVING AS A MEANS OF RECOVERY FROM VIOLENCE

Anti-Armenian violence began in Trabzon on the Black Sea coast in 1895 and spread, plague-like, to the towns and through the countryside all the way down to northern Syria. The massacres reached Sivas too, where, according to official Ottoman figures, the violence cost the lives of 599 Armenian men and left 118 wounded, while 800 shops and four khans were plundered.Footnote 21 The immediate loss of those 599 men and the incapacity for work of many others – like the father of the young Siranush whom we met at the opening of this article – directly resulted in many more young women needing to work, greatly accelerating the arrival of women onto the job market. For them, carpet weaving was the most accessible sector.

Carpet weaving had actually begun in Sivas a few years before the massacres, as a part of the general boom in the trade in oriental carpets. Initially, it was a minor endeavour, limited to the families of a few entrepreneurial men who used household labour to produce carpets. “The governor of Sivas, Memduh Bey, […] following the example of the August Ruler [the Sultan], is also considered a protector of crafts”, as one Armenian commentator noted, when the Ottoman governor invited the womenfolk of the Armenian Altiparmakyan family to his mansion to weave a carpet.Footnote 22 The mother and her two daughters were bestowed with gifts in appreciation of their skill and the quality of their product, but making a beautiful carpet for a bureaucrat is one thing; turning expensive carpets into a commodity and Sivas into a competitive centre of production – what economists would call a “cluster” – was something else again. However, following in the footsteps of Mkrtich Altiparmakyan's household enterprise, about sixty to seventy workshops were established in Sivas, each employing anything from five to ten girls who did their best to be “useful for themselves and their country”.Footnote 23 The Armenian commentator, who gave examples from different carpet-producing countries, called for the establishment of a joint-stock company to bring all the workshops under one roof to reduce overheads. However, craft production was not to be turned into mass production quite so easily as the commentator proposed; costs could not be reduced sufficiently for production to be competitive in the world market, and trade gradually declined over the rest of the 1890s. Indeed, it was only in the early 1900s that other economic actors, owners of both local and global capital, found it lucrative enough to invest in Sivas, for by that time its labour market was overflowing with cheap labour in the form of girls like Siranush Shirinyan and other survivors of the massacres.

An Armenian entrepreneur named Zakaria Tashciyan, who was a carpet merchant in Sivas, has left us the story of the genesis of what took place in the early 1900s, which seems to have been a veritable boom. Mass-production carpet weaving was reintroduced there in the early 1900s when three partners – a financier, a carpet-master, and a designer – joined forces to set up a workshop. Their enterprise was still a small one, and to expand they needed more capital so went into partnership with the famous Takavor Spartali[yan] family of Izmir, one of the most important carpet merchants in the Ottoman Empire during the boom years of the 1890s and 1900s. The Spartaliyans would be one of the founders of the OCM in 1908.Footnote 24

In the early 1900s, Albert Aliotti, son-in-law of the Spartali[yan]s, established three factories, and that is how mass production of carpets began in Sivas.Footnote 25 By 1907, there were a total of eight firms in the city, four of them with very extensive subcontracting networks with small workshops throughout the city and all of them working for international merchants in Izmir. The entire workforce grew substantially in the period, until there were 3,000 young women and children weaving, 1,000–1,500 spinners – they too were women – and about 200 clerks. And Tashciyan hoped to see those numbers double within the year.Footnote 26

In November 1895, Kayseri/Caseria was one of the centres hit by anti-Armenian violence, which, according to missionary reports, killed approximately 1,000 Armenians there.Footnote 27 Just as in Sivas, an immediate problem concerned provision of means for the survivors to secure their livelihoods, something naturally especially difficult for women and children. In the succinct view of Earl Percy, who visited the town in about 1900, the solution was “the [carpet] industry […] started after the massacres as a means of relief for the people”.Footnote 28 Percy was quite right.

In Kayseri, there had been earlier attempts to join the carpet boom already under way in the western Ottoman Empire, but all failed. According to Arshak Alboyaciyan, a survivor of the Armenian deportations and historian of the Armenian towns in Anatolia before 1915, attempts had been made in the early 1890s to establish carpet workshops in Kayseri. Before then, the carpet market of Kayseri was filled with products from Kirsehir made by Kurdish and Avshar tribes, but things changed in 1890–1891, when the Greek metropolit of the St. John Monastery in the Greek village of Zincidere began to teach carpet-making in their boarding school, for which they brought in a woman from the Incesu village of Kirsehir as master weaver. Later, Krikor Agha Kundakciyan of Kayseri, who had learned of their enterprise, went into the business himself, with a tezgah in Kayseri to make silk carpets. However, the first to take up the business in an orderly way was Mgrdich Yaziciyan, in 1894;Footnote 29 a few others barely managed to survive, but most failed utterly.

What is striking is that immediately after 1895 the number engaged in the business grew a hundredfold. According to a letter published in the Armenian paper Buzandion in Istanbul, there were 2,000 looms in 1898 and by 1901 one account – although probably with some exaggeration – was putting the number at around 5,000 in the entire Kayseri region. We can certainly be sure from various sources that each loom was operated by a young woman as chief weaver and that she had two or three children between the ages of six and ten to assist her.Footnote 30 Unlike the case in Sivas, in Kayseri home-based production dominated. Groups of weavers might pool their resources to rent premises locally, while others worked at home, although in both cases most of the actual looms were provided by the merchants and both types of workspace were called işlik. By 1902, the average annual revenue for the city was estimated at 35,000–40,000 Ottoman gold liras, 10,000 of it profit that was shared by the merchants, workshop owners, and workers.Footnote 31

The sudden increase in the trade and its growing revenues led the local government in Kayseri to establish a carpet commission in 1898, consisting of the leading merchants of the town, with five Armenian members but led by a Muslim Turk. The goal of the commission was to improve the quality of the carpets produced in the city and regulate relations between workers and merchants. The commission set the wages for each worker and collected a tax of half a mecidiye on each wool loom and one mecidiye on each silk loom, with the revenue intended to be used only for the development of the craft. The commission provided training and certificates in the use of natural dyes to a small number of dyers, and established a dye-house. It was thus possible to regulate the workforce to ensure the quality of the carpets produced in the town and thereby safeguard revenues.Footnote 32

Carpet production received significant attention in the aftermath of a period of violence in Urfa, also in the northern part of the province of Aleppo. It was claimed that in Urfa alone, a city of 30,000, in late December 1896 approximately 5,000 Armenians were killed of the approximately 10,000 who had lived there before the massacres; most of the dead were men.Footnote 33 Such an enormous figure was seen by many Protestant and Catholic missionaries almost as an “opportunity” to increase their influence and power in the communities while assisting them,Footnote 34 and as part of their efforts mission industries, as Hans-Lukas Kieser posits, became particularly important in allowing the violence-stricken population to earn a living following massacres.Footnote 35 The carpet factory established by the German missionaries in Urfa was indeed a successful example of such a mission industry.

The German Orient Mission was established in Urfa in 1897 by none other than the famous Dr Johannes Lepsius, who the year before had founded Deutsche Orient-Mission (DOM) and whose book on the horrors of the deportations during World War I is considered one of the most courageous of all attempts to publicize the mass violence against Armenians during the Great War. Less well known is that Dr Lepsius was a Christlicher Unternehmer who specialized in oriental carpets.Footnote 36

Economic calculations were embedded in Dr Lepsius's humanitarian mission from the beginning, as the lines blurred for many of the missionary enterprises in Anatolia after the violence against Armenians in the mid-1890s.Footnote 37 Dr Lepsius had established the German Hilfsbund für Armenien, later the Deutsche Orient-Mission, which, in the late 1890s, opened a carpet factory in Urfa and alongside it an orphanage, workshops for orphans, and a hospital – although the factory was soon afterwards detached from the mission (Figure 2).Footnote 38 Lepsius's carpet factory provided jobs to violence-stricken women in the town, just as the Capuchin sisters did with their home-based employment networks of lace-making, or Corina Shattuck, the famous missionary of the American Board for Foreign Missions, who, in addition to her “Industrial Institute” for orphans, had established a workshop for women in Urfa who worked there hemstitching linen handkerchiefs.Footnote 39 The carpet factory's expansion from the late 1900s until World War I was quite striking, as it entered into various agreements and sub-contracting arrangements with multinational companies. These included the factory's contract with the Austro-Orientalischen Handels-Aktiengesellshaft, which was pivotal in supplying the Central European markets with carpets produced by Urfa's Armenian women.Footnote 40

Figure 2. The weaving section of the “Industry House” of the German Orient Mission in Urfa. The carpet weaving section would soon begin to act independently from the Mission and expand its activities.

Der Christliche Orient, March-April 1901.

Dr Lepsius's own business enterprises in Germany must have been crucial in the development of his endeavour in Urfa, for he was himself a carpet manufacturer. He owned a workshop in Friesdorf, which had been established both to provide income to the peasants of the village and to generate revenue for the expenses of the mission in the East.Footnote 41 Dr Lepsius later dismantled the workshop and relocated it to Urfa. Before coming to Urfa, Dr Lepsius stated that he wished to establish “a future mission industry in the Orient […] following a trip to Turkey that would also serve to explore the condition of the Armenians”.Footnote 42 Among his reasons for choosing Urfa were the availability of cheap labour after the massacre there and the future prospect of reaching markets easily thanks to the German-initiated Berlin-Baghdad railway, to say nothing of Germany's imperial ambitions in northern Syria.Footnote 43 Lepsius provided the relief organization with the entire facility and a trained management staff of four Germans whom he sent to Urfa to teach new techniques. And so it came about that a carpet factory was established as part of the Orient-Mission in Urfa. The workshop began work with about ninety women in the late 1890s and in 1904 was able to purchase from the DOM the land it stood on, so establishing itself as a company independent from the missionaries and relieving them of the financial pressure of supporting the factory. The new carpet company was called Deutsche Orient-Handels und Industrie-Gesellschaft (DOHIG), with Dr Lepsius's investment of 16,000 marks making him the largest shareholder, with six other shareholders each holding 4,000 marks’ worth. Meanwhile, other wealthy Armenophiles and aid organizations in Germany and Switzerland purchased bonds.Footnote 44 The company's labour force expanded from 200 young women in 1899 to 600 working actually onsite by 1913,Footnote 45 although including women who wove at home on looms provided by the factory the true number of employees was much higher.

However, Dr Lepsius and his carpet factory was not the only case where missionaries organized carpet production. Other missionaries too undertook similar attempts, although none as successfully as the German enterprise in Urfa. For instance, the American missionary orphanages in Ayntap (Antep) and Kharpert (Harput) had a few looms in their facilities alongside other “industrial work”.Footnote 46 In Hachen (Haçin, Saimbeyli), in the Cilicia region, a British subject working for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions named John Martin established a carpet-weaving workshop in 1898. He brought in an Armenian designer from Sivas and employed Kurdish women to teach weaving to Armenians, but his enterprise soon closed. However, Martin's workshop for producing the regional fabric called manusa was more successful, as was the case in other instances such as the Armenian Relief Committee, which used manusa production in the same period to provide assistance to widows.Footnote 47 Production of manusa or other local products required less capital and so appeared to the US missionaries to be preferable forms of industrial activity. Only a few, such as the Corina Shattuck already mentioned, had the necessary organizational ability and connections to become players in international markets, so although they produced very valuable and internationally sought-after carpets, enterprises requiring substantial capital investment like Dr Lepsius's were rarely attempted by US missionaries. However, fifteen years after Martin's attempts in Hachen following the Hamidian massacres, international capital would once again revitalize carpet weaving following another instance of violence.

The massacres in Cilicia, known as the Adana Massacres, took place in April in the context of the 31 March/13 April counter-coup in Istanbul. Divisions within the Committee of Union and Progress, anti-Armenian agitation in the newspapers, and rumours of Armenians arming themselves combined with long-standing ill-will over the contrasting wealth of Armenian industrial and merchant capital owners and poverty among Muslim seasonal cotton workers to ignite an ethnic clash in the town. According to the official numbers, about 6,400 were killed, about 1,200 of them Muslims and most of the rest Armenians.Footnote 48 As with the massacres in the mid-1890s, Armenian widows and orphans embodied a major dilemma in the immediate aftermath in 1909. After the Armenian Massacres in Cilicia, in September 1910, the Armenian Patriarchate and the Administration of the Armenian Community in Istanbul created a Committee for Widow Relief and Care (Ayriakhnam Handznazhoghov) and sent it to the violence-stricken region. Its primary goal was to create jobs for widows by which they could support themselves and their fatherless children.Footnote 49

The Patriarchate's Widows Committee was keen to establish workshops to make local craft products in the hope that they could be exported, so the efficiency of such undertakings and their need to make a profit were never far from Committee members’ minds. After preliminary investigations, the Committee decided to invest in workshops producing not only carpets but other textiles, like dresses and socks. Some, like the sock workshop in Hachen, soon enjoyed considerable success. In its early days, in March 1911, the Hachen sock workshop housed seven sock-making machines, but before long it was accommodating forty-two.Footnote 50 The Committee established carpet workshops, too, although they faced many problems from competition and the priorities of the actors in the export-oriented carpet market. For instance, the Committee, after investigating the region's potential, decided in March 1911 to establish a carpet workshop in Hachen. In search of advice and expertise to assist with the initial setting-up of production and marketing, they first applied to the OCM and then to Karapet Efendi Kehyayan of Aleppo, a prominent oriental carpets merchant. Unfortunately for the Committee, both the OCM and Kehyayan rejected their requests for assistance.

The Committee had meanwhile begun perforce to spend its emergency fund for the daily needs of the widows, so they decided to open their own workshop. Accordingly, seven looms were installed and masters were brought in from Kayseri in March 1911. Nevertheless, even the Committee recognized that the workshop's early products were inadequate; the masters proved neither adept in all the fine details of the craft, nor were they versed in the latest technical and scientific developments in carpet production.Footnote 51 The real challenge, however, was none other than the OCM itself, for soon after the Committee established its workshop in Hachen the OCM opened its own workshop, larger, better capitalized, and with superior equipment.Footnote 52

As various observers noted, the women and children in the violence-stricken region were quite simply involved in a fight for market share. First, Hampardzum Boyacıyan, a politician from the socialist Hnchaks with family ties to Hachen, visited the town and suggested that the Committee expand its sock workshop and sell the carpet workshop to the OCM. However, the Committee was powerless to act on Boyacıyan's suggestion without its Inspector Jaques Sayapalyan's report, but perhaps fortunately that too presented sale to the OCM as the only solution. The OCM had centralized its system for dyeing yarn, allowing it to produce yarns of higher quality, and its looms too were better enabling them to make carpets for the upper end of the market. The Committee's workshop would therefore either have to upgrade their looms or accept that they were producing for the lower end of the market. Moreover, the OCM's marketing network enabled its products to reach European and American markets, whereas the Committee lacked any such commercial connections.Footnote 53 Yet, for the Inspector, the most important motivation to sell the workshop to the OCM was related to its workforce. Carpet making primarily employed not elderly widows but young girls, who were not the Committee's target population in Hachen. It is interesting here to point out that the Inspector presented his finding about the ages of the women as if it were something that had only recently emerged in the face of competition from the OCM – as if it had not been known that many young women who had been affected by the recent violence were working at the Committee's carpet-making facility to help their families. At any rate, eventually the workshop did indeed change hands, and the Committee even praised the Inspector for the bargain he struck with the OCM, under which he was able to sell the workshop with all its equipment and products to the multinational “at a small loss”.Footnote 54

In all cases, carpet production that began as a relief effort in the violence-stricken regions soon became a major industry employing hundreds of women in a variety of labour regimes unknown to them before the massacres. The expansion of the industry went hand in hand with the circulation of discourses in both the Armenian community and the broader society aimed at justifying the view that individuals were responsible for their own and their family's well-being, that their welfare was not the entire community's responsibility.

INVESTMENT IN PHILANTHROPY AND THE DEBATE OVER MORALITY

The expansion of the market for oriental carpets and the growth of the economic actors’ power to reconstruct post-violence Armenian communities combined to create a distinct social-cultural environment. In the violence-stricken regions, capital owners, community leaders, and many of the destitute women who joined the workforce formed what David Harvey calls “structured coherence”, creating material institutions and discourses to bolster their community and strive for its solidarity.Footnote 55 In an increasingly market-dominated society, the exploitation of women and children through low wages and long hours began to be viewed as culturally acceptable – in fact, as the “the moral way” to earn income.Footnote 56 It was presented as if it were the only means to alleviate the women's wretched condition, that they must help themselves and their families and so serve their community. Any opposition was labelled laziness and even perfidiousness.

The discourses about the ethics of the new capitalist relationships in general and of carpet production in particular parallel the changes in the understanding of the work ethic associated with the development of economic thought and the new relationships between the body and morality. As hard work came to be emphasized in the late Ottoman Empire as an element of the corporeal morality of the individual, simultaneously the categories of “the needy” and “the lazy” were created, transforming values and norms alongside the needs of capitalist modernity.Footnote 57 The debate among intellectuals, merchants, community leaders, and missionaries about the effects of the carpet market that began to grow following the violence is a good place to start to examine how such discourses, framed as the reconstruction of communities through labour, slowly opened the way to the acceptance and diffusion in the Ottoman Empire of exploitative market relationships as the norm in the empire's role as part of the global economy.

In fact, the imperial context was already ripe for such a development. The Ottoman economy, after its bankruptcy in the mid-1870s and following two decades of economic crisis, was in need of revitalization. Attracting foreign capital for infrastructural developments was one aspect of its redevelopment, one example of it being the Berlin-Baghdad railway. On the manufacturing side, revitalization of small-scale labour-intensive local industries was on the agenda, and, as we have seen, carpets were the most export-oriented commodity the empire produced. The Ottoman state therefore promoted carpet production in Anatolian towns by exhibiting their products at the various World's Fairs,Footnote 58 and when the Ottoman government attempted to establish an industrial base in the Sivas region carpet production was one of the industries it promoted by assisting entrepreneurs in the establishment of the first carpet factory in Sivas and then continuing actively to support it.Footnote 59 In Kayseri, the need to increase both the quality and quantity of carpet production mentioned earlier motivated the governor to establish another carpet commission.

The new economic goals and new labour regimes and work environments were accompanied by talk of providing jobs for the poor which justified the establishment of them. For instance, the notion of providing work to the needy was invoked in connection with the sultan's personal endeavours in the capital, where, in the same period, carpet-weaving workshops were established under his auspices specifically to provide work for the urban poor.Footnote 60 Missionaries, too, contributed to the discourses of community building, promoting solidarity based on industrial work and the moral values associated with earning wages, with for instance violence-stricken Urfa's new carpet factory appearing prominently in missionary publications of the period.Footnote 61 Interestingly, discourses about philanthropic investment were used not only in public but also among interested parties in smaller circles, such as those of the European shareholders of the carpet factory in Urfa. In 1910, for instance, as the factory faced financial difficulty the bond holders of the DOHIG in Europe were asked to convert their bonds into capital contributions. A draft of the company report summarized the situation as follows:

the previous shareholders have no capital interest in the enterprise, but wished to serve in the human interest of the economic development of the plundered and impoverished Armenian population. Thus, the shareholders have agreed to limit the net-return of their capital to between 4% and 5%, so that future net profit of the consolidation and expansion of the company can be used [in humanitarian direction].Footnote 62

However, the most important arena within which to observe the spread of such public discourses, and a testing ground for their acceptance, was the newspapers, which discussed the significant role of providing work not only through the philanthropic institutions of the government or the sultan, but through the market and private capital. Indeed, in most cases the importance of carpet production to the recovery of the violence-stricken poor was promoted by people who themselves had stakes in the carpet business. Tashciyan, for instance, in Sivas, himself invested in the system in his capacity as a merchant, observing that carpet production “has been very beneficial to the poor folk of the city”.Footnote 63 Shavarsh Yeseyyan, from Kayseri, a carpet designer, likewise condemned the declining quality of the carpets produced there, justifying the work of the carpet commission in maintaining the trade. However, Yeseyyan's major concerns were that the city was losing a source of wealth and that the poor were being deprived of their main source of income.Footnote 64 He noted that the wealth was shared among the silk merchants who provided the raw material, the merchants who sold the carpets, and the poor workers and peasant families. He concluded therefore that the situation, “causes them a peaceful, happy and moral life; those who have jobs are spared from evil by living morally and happily […] they do not become a burden to their nation, to their city or neighbourhood”.Footnote 65 Private capital's role as the motive force organizing the business and the government's as its supporter and the regulator of its market were justified by a discourse of enabling the needy to assist themselves, thus lessening the responsibility of the local community and state for the poor in their current condition, let alone the latter's role in the violence that had brought them to it.

The new labour regime initiated in the post-violence geographies did not go uncontested, although the criticisms never became general nor were they a reaction to the transformation from community-provided assistance for the poor to the idea of personal and communal salvation through individual hard work. A debate concerning the carpet factory in Sivas published in the Istanbul daily Arewelk is a case in point. The first letter was signed by “A.P.” from Sivas and the second, in response, was written by Robert Orberyan, a rug-merchant from Izmir. Both letters date from May 1902 – immediately after Albert Aliotti established his carpet factory in Sivas. A.P. turns out to have been a somewhat lowly religious dignitary in Sivas, and he began his criticism by clearly stating that he was not against competition in the market, but against its consequences – thus establishing himself firmly in favour of the new capitalist order even while criticizing Aliotti's factory, on various grounds. A.P. claimed that one Mr Ekizler, an agent of Aliotti, had rented the Armenian Community School in Sivas and refused to move out, despite protests. More importantly, Mr Ekizler was refusing to improve the poor working conditions in the factory. A.P. then went on to say this:

[…] And their factory? Oof! Don't ask. In the small rooms of the school 30–40 girls are placed next to each other or on top of each other. Once I had the honour to be invited inside – a real honour, it should be said, as no one has been accepted inside the workshop. When I proposed to open a window to change the air, the girls looked at me stupefied, objecting that they would catch cold. There was every kind of infection. Dust particles were waltzing in the air. I covered my mouth and nose with my handkerchief; I almost suffocated. That has to be improved, because the poor are spending their physical being for the profit of others […] Is it also necessary to lose their morality?Footnote 66

Such criticism of the material conditions of the carpet workshops – particularly in Sivas – was common and observed in later eras too.Footnote 67 However, the role of market relations was never raised in discussions of poor working conditions, and the suggestion was always that the various tensions arising in the community consequent on the rapidly growing carpet sector could be solved only through capital. We can better understand that by examining Orberyan's response to “A.P.”.

Oberyan made it clear that the government was behind the Aliotti enterprise in Sivas. The factory representative “was accepted with indescribable well-wishes by the officials of the government, who on every occasion helped in the success of the enterprise. It is impossible not to mention the sympathetic encouragements of the [governors], the late Haci Hasan Pasha, and the newly appointed Reshat Bey”. In a long letter, Orberyan openly pondered the carpet entrepreneurs’ role in the development of the poor and now violence-stricken regions:

That [carpet] trade brings blessing with it everywhere […] I would like to ask, “Where is that bread which [Aliotti] wanted to grasp from the hand of the poor Armenian woman?” […] The moralist A.P. and people like him consider the morality of poor and orphan girls to have been lost when they go to work to produce [carpets] for their daily bread. From my heart, I wish that there were not one but ten who would go and establish houses [i.e. workshops] for the betterment of the economic condition.Footnote 68

Finally, addressing the criticism of the low wages and poor working conditions, Orberyan used an analogy well-known in Anatolia: “Someone gives a cucumber to a poor man whose breath reeks of hunger, but the hungry man rejects it, saying ‘This cucumber is crooked!’” [or “beggars can't be choosers” as we say in English].Footnote 69

Providing a “moral” income was a central aspect to the discourses. Modern scholarship has tended to interpret “morality” primarily as “sexual honour” and the protection of male patriarchal codes. Yet, the quotes above, including Oberyan's analogy, at least hint that a complementary meaning of “morality” was developing, that of having the “honour” to earn a living instead of being dependent on charity. In other words, individual labour that lifted from the shoulders of the community the burden of looking after the needy was depicted as “moral” work. That was most visible when such “moral” income was juxtaposed with its opposite – with laziness and dependence on charity.

Marash was another Cilician town hit by the 1909 massacres, and the introduction of carpet-making there too nicely illustrates that reasoning. The massacres of 1895–1896 left 152 women as widows while there were a further 148 widows after the massacres in 1909, leaving a total of 300 widows, ninety of whom were unable to work. The OCM arrived in Marash before the Armenian Relief Committee for Widows, opening a workshop in 1910 so that by the time of the Committee Inspector's visit to the town a few years later there were already 150 looms operating in Marash, with about 600 girls working at them. Yet, as the Committee's Inspector noted, there were only a few widows among the workforce, their absence considered interesting in that a number of young women were among the widows who could have worked in the OCM workshop, but it appeared that many were unwilling to do so. The Inspector's explanation was simple: the cause of the phenomenon must have been laziness – certainly not the OCM's policies nor the working conditions!Footnote 70 The Inspector had ready a long story detailing what he called “the development of laziness” among the people of Marash. It was not inherent in them, he opined, but was a result of the missionaries’ activities in the region after the massacres of 1895. To the Inspector, missionary activity after the massacres of 1895–1896 was, with the possible exception of a missionary industrial plant, primarily religious propaganda, and the people of Marash preferred to obtain money by simply converting to one or other variety of Christianity rather than by earning an income by the sweat of their brows. The Inspector claimed brusquely that the missionary material assistance “clearly weakened the population, made [them become] lazy and lose [their] morals (mezkatsutsatz, tzulatsutsatz, anbaroyakatsustatz e zhoghovorde)”.Footnote 71 He advised a number of girls to go to work at the OCM workshop, but they did not, despite their having at first agreed to; clearly this must have been for no other reason than that they were accustomed to receiving assistance without working. By blaming the people and their laziness for their problems, the Inspector shifted attention from the massacres as the main cause of the situation to individual moral failure and lack of work ethic. Conveniently, too, his diagnosis eased the burden on the community administration which had failed to provide assistance. Hard work was seen as the only solution that could elevate their status, morality was now closely associated with an individual's work, which was seen as the means by which violence-stricken communities could repair themselves. The growing dominance of market-based definitions of hard work and laziness left any of Armenian women who were by choice without work deprived of that choice's potential as an act of resistance to changing work regimes and social conditions.

CONCLUSION: LABOUR CAUGHT BETWEEN SURVIVAL AND COMMUNITY BUILDING

The cases of Sivas, Kayseri, Urfa, and Cilicia demonstrate how various labour markets were opened as cheap production sites following anti-Armenian violence in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Various agents – bureaucrats, missionaries, local merchants, and multinational companies – were all part of that development both materially and through the discourses they disseminated in public. Labour regimes and those various discourses, particularly that of “morality”, were related to the new economic and social environments in the post-violence communities, especially their role in legitimizing the rule of market forces and withdrawal of community institutions from supporting the poor, paving the way for the subsequent use of the cheap labour of women and children during the reconstruction of the local economies. I have argued here that the growth of the overall Ottoman economy and its reindustrialization in the early twentieth century and the turning of oriental carpets into a globally sought-after commodity were enmeshed with the expansion of the labour market after anti-Armenian and gendered violence.

Our focus on the labour regime and the discourses around it should not blind us to a practice that became widespread in the period and was in fact a radical solution to the problems of violence-stricken communities, especially the problems faced by women. It not only posited and accepted women as breadwinners for the surviving members of their families, it also lessened the burden of widow and orphan care by relieving the community of it. With the shift in responsibility, the relationship between individuals and their communities were reconfigured, as the ingrained relationship of dependence and social control began to take on different forms in the more market-based context of the post-violence era. Women's new participation in the labour force and their economic empowerment in their community – however limited it might have been – was all the same occurring amid systematic poverty and with constant and unavoidable dependence on fragile local and global economic dynamics.

This understanding of self-sufficiency became even more central to the reconstruction of the communities in the following years, as in the years 1915 to 1922 the survivors now became refugees. Some Armenian weavers were able to live by their skills and were able to pass them on; they could find work too in their new circumstances as refugees. Survivors from Sivas – including Siranush – have testified that some who could weave carpets were effectively deported from their hometown to work in the carpet factory at Aleppo,Footnote 72 while others stayed in Anatolia to weave carpets in orphanages and institutions for widows opened there and in Syria by missionaries and the occupying forces after the war.Footnote 73 Kuenzler, a Swiss missionary at Urfa, moved the German carpet factory in Urfa to Ghazir in Lebanon, where it served as a shelter for hundreds of Armenian orphans.Footnote 74 It was in the workshop of that orphanage that Armenian orphans learned the skills that enabled them to produce the famous Orphan Rug, which was sent to the White House in 1925.Footnote 75

The story of carpet production in the Armenian communities in the late Ottoman Empire allows us to challenge the limits to Ottoman history and historiography set by the absence of discussion of violence, and of anti-Armenian violence in particular. My aim here was to adduce the case of carpet-making to problematize why and how the violence in 1895–1896 and in 1909 destroyed more than just the property of the thousands of Armenians whose lives the violence claimed. These were people accepted chiefly as the artisanal sector in Anatolian towns, and the massacres shattered too their existing commercial networks and market relationships, which then allowed capitalism to make inroads into regions previously relatively detached from global markets while almost incidentally pulling women into the labour market. The case of oriental carpets in the late Ottoman Empire shows that it was not, as Rosa Luxembourg once famously stated, the violence inherent in capitalism which expanded its limits, but rather the destruction violence brought that made the required room for capitalism to expand its borders into the world of the late Ottoman Empire. The empire's transformation into a capitalist society came after violence, as recovery both created the material conditions for market relationships to be extended and stimulated the discourses which encouraged broader society's acceptance of them. For its part, the Ottoman state stepped in only to support the new developments. Thus, the oriental carpet's transformation into the most important commercial product of the Ottoman Empire and by the turn of the century a true global commodity stands as a case clearly highlighting the prime role of violence in transforming the Ottoman Empire into a capitalist society.