The main reason for having part of my assets managed by a company incorporated in Luxembourg was the fact . . . that this country would always protect private property and that in the past foreign deposits were never subject to any restrictions. Originally, I had the intention to form a Swiss corporation for this purpose, but I abandoned the idea in favour of a company incorporated in Luxembourg, owing to the much lower corporation taxes in Luxembourg.Footnote 1

This short excerpt is not from a recent report published following one of the many scandals that have shaken the Luxembourg financial centre in the last ten years; it dates from the late 1940s and reveals practices from the interwar period. The Panama Papers and LuxLeaks, to name but two recent leaks, as well as the financial crisis of 2007, brought the issues of inequality and tax justice back to the forefront of both the media and the academic literature.

A great number of journalists and social scientists have devoted increasing attention to the emergence of practices such as tax avoidance, tax evasion and legislative devices related to the financial globalisation that has characterised Western countries from the 1970s onwards.Footnote 2 Historians have recently argued that there should be a focus on these phenomena in the interwar period.Footnote 3 The First World War and its financial implications led almost all European countries to substantially increase taxation, including for assets that were previously not taxed very much or at all. Conversely, several countries opted instead to enhance the attractiveness of their fiscal environment for foreign companies and individuals interested in escaping these new tax regimes. One of the most efficient tools used for this purpose was holding companies. These companies made it possible to conveniently transfer capital from countries with high taxation to countries where it would be taxed less. Although in the late nineteenth century holding companies were initially used as a legal construct aimed at ensuring more efficient overarching control structures for major regional and national infrastructure projects (electricity, gas, railways, etc.),Footnote 4 from the post-First World War period onwards they also became a means of tax avoidance.Footnote 5

Switzerland was the most dynamic country in this respect. Swiss holding companies were widely used during these years as capital deposit and investment platforms for French and German capital.Footnote 6 But other European and non-European countries were also moving in the same direction, sometimes copying the Swiss regime directly. In 1926, Liechtenstein introduced favourable national legislation for holding companies.Footnote 7 Monaco made similar arrangements in 1934 and 1935. Panama, Tangier and Curaçao followed suit in the late 1930sFootnote 8 – and Luxembourg also followed the same path.

The Holding Act, introduced in Luxembourg in July 1929, was therefore one of these legal artefacts which, behind the legitimate claim of solving double taxation issues, also provided a privileged route to deflect fiscal revenues from countries with high taxation regimes to countries with typically limited territorial extension and small populationsFootnote 9 that were interested in collecting additional fiscal resources in the post-war context.

Although the Act is regularly mentioned as central to the subsequent development of the financial centre,Footnote 10 its applications during the interwar period tend to be underestimated. One historian claims that the economic crisis of 1929 prevented the use of its tools.Footnote 11 Another argues that tax benefits only began to play a role in Luxembourg in the 1980s.Footnote 12 But some contemporary observers were already pointing out how the prevailing economic climate favoured tax avoidance through holding companies.Footnote 13 And the Swiss authorities were concerned about the development of the Luxembourg holding company system in the interwar period, seeing it as a major competitor.Footnote 14

This article therefore has a twofold objective. On the one hand, it aims to include Luxembourg in a nascent international historiography of offshore financial centres (OFCs).Footnote 15 While Switzerland is relatively well studied today,Footnote 16 the rest of the world map remains a historiographical void. On the other hand, it also takes issue with an interpretation that describes the development of the Luxembourg financial centre as a ‘fluke’ and suggests that its real expansion only began in the 1960s.Footnote 17

Holding Companies’ Code of Capital

The Holding Act of 1929 (H29), after a rapid debate in two sessions, was approved on 31 July in the Luxembourg Chamber of Deputies, with thirty-two votes in favour and eleven against.Footnote 18 It was the first law on the matter in Luxembourg and it filled a legislative void in the national legal framework.Footnote 19 While only applying to pureFootnote 20 holding companies, H29 was presented as a solution to avoid double taxation for multinational companies interested in concentrating their geographically dispersed assets under the management of Luxembourg-resident holding companies.Footnote 21 In effect, though, it provided a tool to establish a low taxation regime for the capital managed by holding companies.

The origins of the law remain partly unclear. The literature of the time points to Pierre Braun, director of the fiscal registration office (Administration de l'enregistrement et des domaines; AED), as the instigator of the law.Footnote 22 There is no doubt that he was the civil servant who led the project within the administrative apparatus. But contemporary sources do not explain how a civil servant at the head of a small administration came up with such a legal construction.Footnote 23 Documentary evidence suggests it was the Luxembourg steel conglomerate Aciéries Réunies de Burbach-Eich-Dudelange (ARBED) that launched the idea of a new piece of legislation for holding companies.Footnote 24 At the time, ARBED was experiencing economic difficulties, with French and Belgian interests trying to take over the group. Transferring control of the majority of the group's shares to a holding umbrella was seen as a potential way of sheltering the company from hostile takeovers.Footnote 25

An Alternative Code of Capital

However, independently of ARBED's prior lobbying pressures, Luxembourg lawmakers seem to have been interested in pursuing a broader target, namely, ensuring additional fiscal revenues to the state through the holding system. This idea had indeed been explicitly stated on multiple occasions by several political figures from the main party leading the liberal governments in 1929 and during the 1930s, the Catholic Party of the Right (Parti de la droite, which would subsequently become the CSV). For example, in a report dated 15 July 1929 by the Section Centrale of the Chamber – with President of the Chamber Émile Reuter as first signatory and Auguste Thorn as rapporteurFootnote 26 – we read that: ‘The consideration of the Holding Companies plan must be approached with the firm intention of . . . looking at the question from above and considering the great moral advantages and the general interest of the country, as well as the immediate fiscal interest.’ Pierre Dupong, Minister of Finance in the first government led by Joseph Bech, in one of his speeches during the debate on H29 in the Chamber, said: ‘If it were possible for us to create here a kind of free port for all the taxpayers who could come to us in exchange for a fee that would be of interest to our country, we would not hesitate for a moment to do so.’Footnote 27 The notary and legal expert Bernard Delvaux, in his theoretical analysis of the holding system in Luxembourg published in 1933, was also rather explicit in this regard: ‘The purpose [of the Holding Act], although its theoretical interest is debatable, is clear: to create new resources for the tax authorities.’Footnote 28

H29 was indeed a ‘purely fiscal’ law.Footnote 29 Its purpose was not to introduce new legal institutions but instead to bring about a change in terms of the legal coding of capital.Footnote 30 In H29, a holding company is defined as a company that does not directly participate in any industrial or commercial activities; its main purpose is to manage a portfolio of shares in other companies with the aim of exerting forms of control over them or as a type of investment in pooled securities.

The case of Switzerland in the interwar years had shown to Luxembourg's policy makers how swift and fruitful for the state treasury the growth of the holding sector could be. It was no coincidence that in the preparatory draft of the law, Pierre Braun evoked a fully-fledged fiscal race to the bottom against Switzerland and Liechtenstein.Footnote 31 According to Braun's report, the two countries were able to attract international holding companies to their fiscal system essentially because of their low tax burden compared to Luxembourg. In particular, the Luxembourg tax on profits of 9 per cent and other residency taxes of 13 per cent that were levied on an annual basis on the total capital asset stock of a holding company could be identified as the principal obstacles hindering Luxembourg's competitiveness in this area. Braun's drafted proposal – later approved by the Chamber and included in the Act – was therefore to limit the annual tax contribution of a holding company domiciled in Luxembourg to the sole subscription tax on company financial assets of 0.16 per cent of the capital stock.Footnote 32 According to Braun's calculations, for example, a holding company with a total capital stock of 20 million Luxembourg francs would pay 32,000 francs in Luxembourg, as opposed to 38,000 in Switzerland or Liechtenstein.Footnote 33 Once the law was implemented, the director of the AED expected a capital inflow related to companies of this type accounting for 1.5 to 2 billion Luxembourg francs – a forecast that was already exceeded in 1933, when the total capital assets of the holding companies domiciled in Luxembourg reached the value of 2.2 billion Luxembourg francs.Footnote 34

H29: A ‘Liberal’ Act

According to contemporary observers, the low taxation regime was not the only factor that made Luxembourg's holding system highly competitive.Footnote 35 The stability and predictabilityFootnote 36 of Luxembourg's legal framework on holding companies were also appealing factors for international investors in the 1930s.Footnote 37 The Party of the Right, which remained in government between 1926 and 1940, played a primary role in building this reputational image for Luxembourg's holding companies. The party led by Pierre Dupong won the debate for the adoption of the Act in 1929 and was able to limit any critical voices from socialist circles in subsequent years.Footnote 38 During the debate in the Chamber,Footnote 39 socialist deputies such as René BlumFootnote 40 and Pierre Krier had already raised concerns about the introduction of legal loopholes for tax avoidance.Footnote 41 Blum offered a vivid image of the consequences of the creation of an offshore platform in Luxembourg: ‘What we are doing is creating a real tax privilege. One could even go further and say that we are creating a tax immunity. . . . This principle, which we are going to enshrine, clashes head on with the principle of equality of all Luxembourgers before the law. . . . A kind of capitalist feudalism will be created in our country.’Footnote 42

During the 1930s, the parliamentary opposition voiced (with waning strength) its criticisms of the Act in the Chamber's legislative committees and also in local press outlets. The newspaper Escher Tageblatt stressed the negative consequences for Luxembourg's reputation at the international level.Footnote 43 In March 1931, the Tageblatt led with the headline: ‘In all other countries, holding companies pay general partner tax. But not in our country. We are, thanks to our government, the Eldorado for big business.’Footnote 44 It is important to note that this left-wing criticism was accompanied by xenophobic and antisemitic overtones. In a long article on the front page of the Tageblatt in 1934 a journalist complained about a holding company whose board of directors was composed of ‘Luxembourg-based German Finanzjuden [Jewish financiers]’.Footnote 45 During the governmental negotiations of 1937, the Socialist Party described this regime as ‘immoral’ but stated that it was ‘not opposed to it’.Footnote 46

The Party of the Right and the Liberal Party, on the other hand, became more and more involved in the holding system. Several members of parliament were notaries, administrators and stakeholders in holding companies. For the Party of the Right, these included Edmond Reiffers, François Altwies, Aloyse Hentgen, Nicolas Jacoby, Auguste Thorn, Emile Reuter and Fernand Loesch, and for the Liberal Party Robert Brasseur and Gaston Diderich. The lawyer Fernand Loesch was, moreover, at the forefront of the successful opposition to the creation of a department within the AED in 1936 that would have been solely dedicated to matters involving holding companies.Footnote 47 Other members of the two parties sat on the boards of banks involved in the holding sector.

Finally, the position of Luxembourg's industry on H29 was basically along the same lines as that of the Catholic and liberal parties. During the failed campaign led by the socialist MP Clément in 1937 to amend certain parts of H29 – so as to avoid ‘pushing tax liberalism to the point where it degenerates into a real incentive for fraud’Footnote 48 – the industrial press took a clear stand in the debate. For example, in the liberal Luxemburger Zeitung, Jules Hayot, secretary of the association of Luxembourgish industrialists, was extremely critical about the potential changes. Even in newspapers less connected to industry, such as the Obermoselzeitung, an editorialist stressed the importance of the competitive advantage given to Luxembourg at the international level by the current version of the law at the time.Footnote 49

Catholics, liberals and most economic stakeholders unconditionally supported the liberal character of H29 and its interpretation. In his aforementioned theoretical study of the law, Delvaux describes the Act as ‘brilliant and liberal’ multiple times and praises its ‘liberal spirit’.Footnote 50 Moreover, the Act was extremely short, thereby offering leeway for subsequent flexible interpretations of the text under the aegis of the AED, which were more often than not qualified as ‘liberal’ by contemporary commentators.Footnote 51

Holding Practices

The essence of the holding regime was concealment. Attempting to reveal its practices will therefore always remain an incomplete exercise. We have chosen three points of view that allow us to identify the actors and their practices in this ‘coding of capital’ (Pistor) that enables the tax base to be reduced in a more or less hidden way: typologies of holding companies, infrastructures of concealment, and the advertising of holding companies. Before addressing these three aspects, however, it is useful to provide a few factual elements on the quantitative evolution of holding companies.

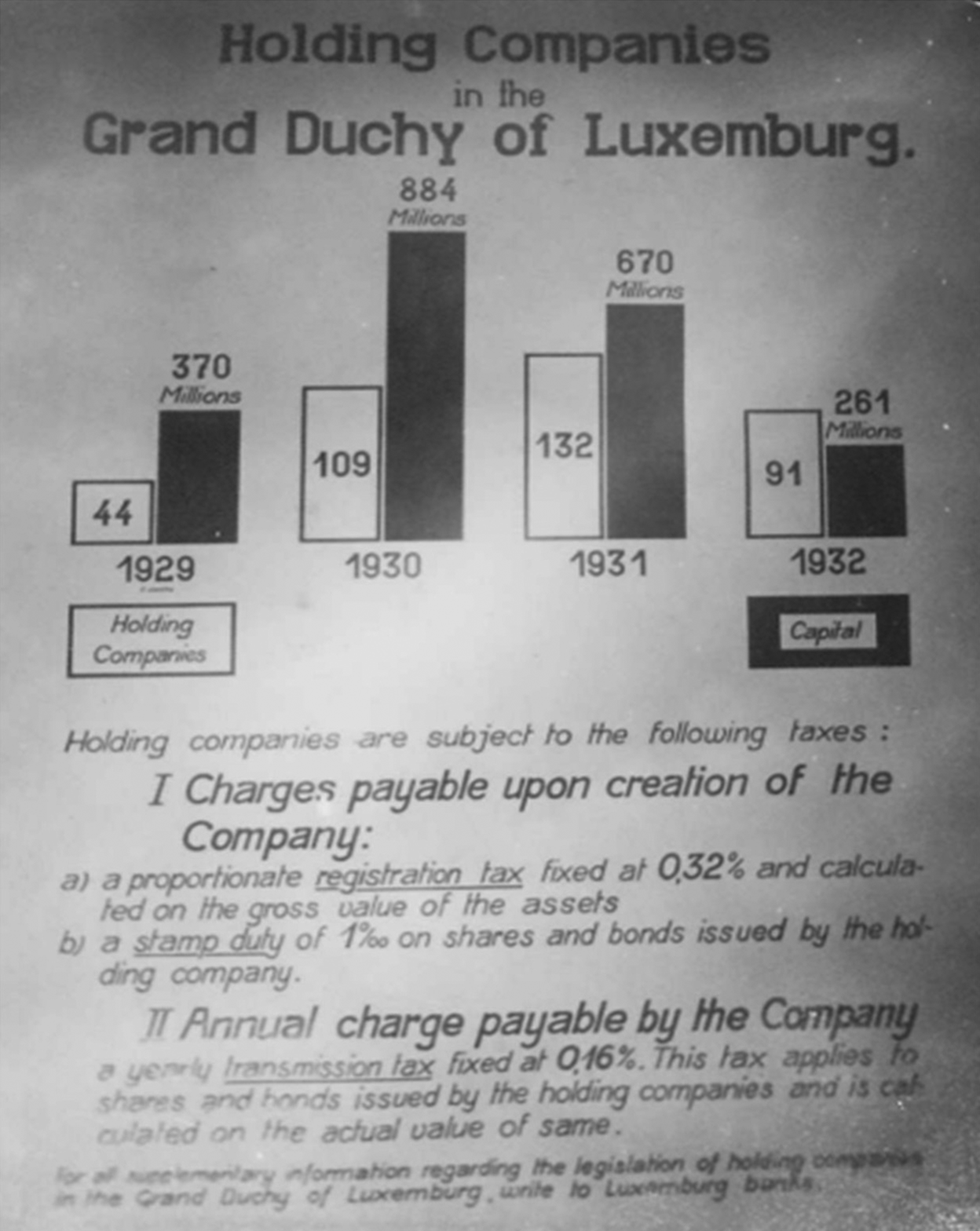

The holding company system in Luxembourg was a real success. A purely quantitative assessment gives an initial idea. The number of registered companies rose regularly from forty-three in 1929 to 1,072 in 1937 before stagnating slightly above 1,100 during the two last years before the war. A total of about 1,500 holding companies were created in Luxembourg between 1929 and 1939. This represented a significant increase in business creation, bearing in mind that between 1919 and 1933 only 250 (non-holding) companies were formed in Luxembourg (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Capital invested in Luxembourg holding companies (in Luxembourg francs). ANL, Chef der Zivilverwaltung (CdZ), box A-6596, Kurzgefasste Betrachtungen über die Holdinggesellschaften in Luxemburg – Jan. 1941 (author unknown).

It goes without saying that the share capital of the holding companies did not represent all the funds that were managed by these companies. The Caisse d’Épargne de l’État estimated that in the interwar period some holding companies managed capital that was up to twenty times larger than their share capital. Proposals to tax this capital were rejected by both holding company lobbyists and the registration authority.Footnote 52 During the discussions in 1929, the capital of the country's holding companies had been estimated to reach 1.2 to 2 billion Luxembourg francs, and just three years after the Act was adopted this level had already been attained. In Switzerland the aggregate size of holding companies was 3.03 billion Swiss francs in 1931, considered as a peak year.Footnote 53

For the Luxembourg government, holding companies provided regular fiscal revenues until the war. According to the Belgian economist Luc Hommel, between 31 July 1929 and 31 December 1939 revenues from holding companies amounted to 62 million Luxembourg francs out of a total of 3.9 billion over these years: during the first decade after the Act was adopted, holding companies therefore accounted on average for 1.6 per cent of tax revenues.Footnote 54 This represents an average of 6 million each year, far exceeding the initial estimates. It is therefore not very surprising that holding company revenues regularly featured in annual budget discussions. For some, this result was the proof of a successful policy. In 1934, Pierre Dupong emphasised their role as one of the factors contributing to a balanced budget.Footnote 55 However, the benefits for Luxembourg were not just limited to direct tax revenues. As the Belgian economist Hommel notes: ‘The direct profit of the holding companies in Luxembourg went to the indigenous banks, which were entrusted with at least some of the financial services of these organisations. . . . It went to the notaries and lawyers. A large part went to the hotel industry and to Luxembourg tourism. These are invisible revenues which, in proportion to the balance of accounts of Luxembourg, are appreciable.’Footnote 56

The practices of concealment make it difficult to determine the specific nationality of the beneficiaries for each holding company. We have nevertheless used various data to identify which countries the main beneficiaries of these holding companies were from in order to sketch a geographical picture of Luxembourg as an OFC.Footnote 57 France (36 per cent) and Belgium (24 per cent) alone account for almost two-thirds of the holding companies for which we have identified the origin of the capital.Footnote 58 This large share can be explained by the close economic links between the three countries since the end of the First World War, particularly in banking, and also by the fact that France and Belgium underwent a major overhaul of their tax systems between the wars compared with the pre-war period. In France, for example, the higher tax rate rose from 2 per cent in 1914 to 72 per cent in 1924. At the same time, the taxable population base increased significantly in the interwar period.Footnote 59 Luxembourg's other neighbouring country, Germany, was initially present but to a lesser extent (around 10 per cent) before almost completely disappearing when the Nazi Party came to power. The third most represented country is Switzerland (16 per cent). It can be assumed that behind this capital identified as Swiss there were other nationalities. Indeed, Switzerland became the main European OFC in the interwar period.Footnote 60 And with the Banque Alfred Lévy & Cie, for example – half owned by a holding company based in the canton of Glarus – part of the capital coming from Switzerland had a structure through which these transfers could be organised. This Swiss presence seems to indicate that, as early as the interwar period, there was a fiscal layering that characterised OFCs from the 1980s onwards. The presence of capital identified as Dutch (9 per cent), although lower than the level of Swiss capital, is another indication of the establishment of layers of concealment, the Netherlands having become a country of refuge for German capital in the interwar period.Footnote 61

Infrastructures of Concealment

Even if these holding companies, by their very nature, were characterised by the absence of any industrial activity and were essentially legislative shells without any significant administrative activity in Luxembourg, they needed legal and financial infrastructures. At the forefront was a banking sector that evolved in seemingly contradictory directions in the interwar period. On the one hand, it was characterised by a certain dynamism and the arrival of Belgian and French capital in Luxembourg. New foreign banks appeared, such as the Banque Générale du Luxembourg (BGL) in 1919, supported by the Société Générale de Belgique, and the Crédit Industriel d'Alsace et de Lorraine in 1920. On the other hand, Luxembourg actors, particularly from the Catholic milieu, also invested in the financial sector by creating two banks, Fortuna and Luxembourgeoise, both of which were founded in 1920. This dynamism can be seen in the significant growth in the size of the balance sheets: for example, the BGL balance sheet increased 4.7 times between 1921 and 1929. The 1929 crisis nevertheless hit the financial sector hard. Some branches of foreign banks and stockbrokers left Luxembourg. Those that remained were faced with a significant drop in business and staff for several years. Between 1929 and 1939, the number of employees at the BGL fell by 25 per cent. It was in this economically tense context that certain financial institutions relied on the holding company market, especially the Banque Internationale à Luxembourg (BIL), the Banque Commerciale and the Banque Alfred Lévy.

The BIL was the most active. Although it was founded in 1856 with German capital, French and Belgian capital became the majority after the First World War. This bank was by far the biggest private player on the Luxembourg financial market. As early as 1930, it emphasised in its annual report the important role that the creation of holding companies played in its activities. The reports indeed underlined that income from holding companies enabled it to counterbalance the decline in other services.Footnote 62 Several contemporary observers estimate that the BIL captured about a quarter of Luxembourg's holding companies. These figures are partly confirmed by the FINLUX database – one-fifth of the holding companies had dummy directors, acting as figureheads, from the BIL, including members of its board of directors.Footnote 63 The two other significant banks in the holding market were smaller players in the financial centre and were mainly investment banks. The Banque Alfred Lévy & Cie was created in 1926 through cooperation between two foreign financial institutions, the bank A. Spitzer et Cie from Paris and the Banque Privée de Glaris in Switzerland. The Banque Commerciale was created in 1921 by German bankers. Like the Banque Alfred Lévy & Cie, the Banque Commerciale was also a small player in the Luxembourg financial centre, but again it was an important player in the holding market. The Banque Commerciale managed 12 per cent of the holding companies in Luxembourg. Other banks were less successful. The Crédit National du Luxembourg, an essentially French-owned bank that was created in the summer of 1929 specifically for holding companies, did not take off.Footnote 64

The banks fulfilled several roles, the most overtly displayed being that of domiciliation, which was provided for in the Act and which they openly advertised (see next section). They then provided the real beneficiaries with nominees, who appeared to be the shareholders of the holding company but who transferred these shares to people wishing to remain anonymous as soon as the holding company was set up. Sometimes this transfer was managed by an agreement. In the case of the Neverst holding company created in 1936 with the help of the BIL, the seven bank employees signed an agreement transferring the shares to the real beneficiary on the same day that the holding company was set up.Footnote 65 But there often seemed to be no written record: this transfer of shares was based on the trust that customers placed in the bank and its employees. This lack of written codification posed a problem after the Second World War when it had to be proved that the holdings were not owned by Germans. When the Swiss bank Charles Perreau was asked to provide such documents, it took issue with the BIL:

. . . like all the companies that were set up at the time, on the basis of information given to us by the Luxembourg banks, the banks managing the capital intervened as a constituent shareholder, by transferring their shares to the interested parties. . . . You know very well that at the time there was no reason to provide authenticated deeds of this nature. The companies were set up on your premises in the presence of Mr Hamelius,Footnote 66 to whom we handed over the funds, and this was the case for Sofinter so that the notary could draw up the incorporation deed.Footnote 67

This game of deception was without any consequences for dummy Luxembourgish directors who might have been worried by the tax authorities when submitting their tax returns. However, as the management of the Luxembourg branch of Société Générale Alsacienne de Banque explained: ‘the competent administration . . . is fully aware of the reasons why promoters of limited companies wish to remain anonymous’. Dummy directors were not ‘worried by the administration because, at an Ordinary General Meeting, they appear on the attendance list X of shares in a company which they do not mention in their wealth tax return’.Footnote 68 They therefore did not have to pay taxes for shares since ‘everybody’ knew that they were not the real shareholders.

In addition to the banks, another professional group in Luxembourg played an essential role, namely notaries. They were a very small group of legal experts, appointed for life. At the beginning of the 1930s, the notarial community was undergoing a major crisis, with several firms being liquidated because they had engaged in disastrous financial affairs.Footnote 69 Like banks, notaries saw holding markets as a potential source of revenue at a time of financial difficulties. And like banks, some notaries were specialised in drafting contracts for holding companies. Of the thirty-two notaries involved in the creation of holding companies in the 1930s, five accounted for three-quarters of them: Paul Kuborn alone recorded a quarter of the holding companies created between 1929 and 1939. On 11 September 1933, he drafted the deeds for ten companies on one day. The other four – Edmond Reiffers, Joseph Neuman, François Altwies and Tony Neuman – each managed approximately 10 per cent of the holding companies created.

A certain amount of know-how and a financial network abroad was necessary to venture into this field. The image of the notary who only authenticated deeds is too simplistic. These notaries did a threefold job. First, although this was not recorded in the official state journal, they were involved in drawing up legal documents. The international nature of the clients required a greater administrative effort than the drafting of legal acts involving only Luxembourg residents. The second element that stands out in this serial source is the service of concealment that the notary offered by giving the names of his clerks as nominees in order to hide the real beneficiaries of the shell companies, a service similar to that offered by banks. Thus a French client wrote to Reiffers: ‘Only three subscribers consent to their names being published. The others want secrecy. It will therefore be necessary for four declarants to subscribe in their place, as previously stated, at least one (or several if you prefer) share(s) and to retrocede them to me.’Footnote 70 Thus Nikolas Krier, who worked for the notary Reiffers, was a shareholder in six of the thirty-five holding companies set up by his firm between 1929 and 1931. Auguste Klein was a notary's clerk in the Altwies law firm in the early 1930s and was a stakeholder in twelve of the fifty-five holding companies established by Altwies. Notaries themselves were not allowed to perform these functions. Finally, some notaries also offered domiciliation services to deal with the annual administrative acts required by law.

These central figures were well connected to political and economic elites. Edmond Reiffers played the most visible and public role, not only through his editorial activity.Footnote 71 During the First World War he served a short-lived spell (two months) as Finance Minister in the government led by the Party of the Right. After the war, he was actively engaged in the foundation of financial institutes supported by the Catholic pillar in Luxembourg.Footnote 72 François Altwies was part of the same network. Also a member of the Party of the Right, he was president of the Chamber of Deputies from 1917 to 1925. The three others, Paul Kuborn, Joseph Neuman and his son Tony, were closely linked to ARBED. Tony Neuman was even elected Chairman of the Board of Directors of the steel company in the 1960s.Footnote 73

The Luxembourg ecosystem was not limited to a network of banks and notaries, however. Small financial institutions such as the Union Financière Luxembourgeoise, a French-owned company that had moved to Luxembourg in January 1929 to act as a stockbroker at the newly created stock exchange, were involved in helping to set up holding companies. Some lawyers (including Bernard Delvaux and Alex Bonn) began to specialise in holding companies, either in conflicts between shareholders or in the management of bankruptcy filings, but their role was still a minor one at this stage compared to their development in the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 74 Real estate agencies offered buildings that could be used as mailboxes for holding companies, located among others on the Boulevard Royal, the road that would be referred to as Luxembourg's Wall Street in the 1970s.Footnote 75 For some newspapers, especially the Luxemburger Wort, publication of the minutes of general meetings of holding companies was a source of regular income. And finally, there was also a hotel and tourist infrastructure that existed on and around holding companies. The Hôtel Brasseur, located on Avenue de l'Arsenal in the centre of Luxembourg City, was the venue for many general meetings – it had an ‘assembly room’ that could be used for such events. But other hotels also began to take advantage of this opportunity, both in Luxembourg City (Hôtel de la Bourse, Hôtel Staar, Hôtel Alfa, Hôtel Sporting, etc.) and in other more touristy towns such as Vianden and Esch-sur-Sûre.

While the consulted archives do provide a partial picture of Luxembourgish infrastructures, this is less true for the foreign companies that channelled their clients to Luxembourg. Traces of these intermediaries are rare and remain anecdotal. The company Deloitte, Plender, Griffiths & Co – the forerunner of Deloitte, one of the Big Four today – used Luxembourg for several clients, including Liebig's Extract of Meat Company Ltd, through the holding company Société Auxiliaire de Finance & l'Industrie, managed in Luxembourg, and the fortune of a rich British citizen domiciled in the Channel Island of Jersey through the holding company Comptoir financier et d'administration, managed in Luxembourg. Lazard Brothers & Co, today the world's largest independent investment bank, was also present in Luxembourg.Footnote 76 In the 1930s, the most prestigious law and accountancy firms in the City began investing in the international tax avoidance market, and Luxembourg proved to be an attractive location for investment. Almost 25 per cent of the income that was legally avoided by Britain's millionaires was realised through holding companies registered overseas. In 1936, the Inland Revenue, the British government department responsible for tax collection, identified Luxembourg, alongside the Channel Islands, the Isle of Man and Switzerland, as one of the main jurisdictions for this form of tax avoidance.Footnote 77

Infrastructures for Advertising

Although the holding company regime served to conceal the beneficiaries of profits, it was nevertheless necessary to raise awareness of the possibilities offered by holding companies. Several actors played an important role in publicising this new way of coding capital in Luxembourg. The most central public player was without doubt the Luxembourg government. It used its diplomatic networks to spread the word about the advantages of this legal construct. In the annual brochure Le Grand-Duché de Luxembourg industriel et commercial, published by the Luxembourg Embassy in Brussels, articles by the lawyer Maurice Sewenig praising the advantages of the holding company system were regularly published.Footnote 78 The Luxembourg government also used international fairs as a sales venue. At the World's Fair in Chicago in 1933, the Luxembourg national stand gave pride of place to the new financial centre. Two banks, the BIL and the Société Générale Alsacienne de Banque, presented their services there. There was also a dedicated exhibition table providing information about holding companies. And the Luxembourg government paid for a special issue of the Chicago Tribune in which three of the nine articles were devoted to the financial centre, including two on holding companies, one written by Paul Bastian and the other by Conrad Stümper, director of the AED. The latter declared the Luxembourg system as ‘the most liberal in the entire world’. Two years later, in 1935, at the World Exhibition in Brussels, the holding company regime was less prominent in the exhibition but in the brochure accompanying the national stand the system was again highlighted in two contributions, one by Jérôme Anders and one by Léon Metzler. A year later, in 1936, Fred Gilson, secretary of the Luxembourg Consulate in the United States, represented Luxembourg at a congress of international companies, held in Chicago, where he reserved particular praise for holding systems.Footnote 79

Banks were far less prominent public promoters of the holding system. The two small banks – the Banque Commerciale and the Banque Alfred Lévy & Cie – seemed not to place advertisements, unlike the BIL. During the 1930s, the BIL pursued a policy of regularly showcasing its know-how in the field of holding companies in the general press and also in tourist guides (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Touring Club Luxembourgeois 1936, Luxembourg, Imprimerie P. Linden, 1936, 109.

Figure 3. Pamphlet advertising Luxembourg holding companies that Paul Bastian distributed during his ‘study trip’ to the United States in 1933. ANL, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, box 3676, Rapport de M. Bastian, directeur de l'agence économique et financière, sur un voyage d’études aux Etats-Unis.

The press in neighbouring countries also covered Luxembourg's holding legislation. In Belgium, the liberal and right-wing press regularly reported on developments in Luxembourg holding companies in the 1930s. This was also an opportunity to criticise the Belgian tax system and the ‘politicians of all democratic persuasions who are imbued with tax mysticism’.Footnote 80 In France, too, the economic press reported positively on this new legal instrument (giving the system free publicity in the process). In 1931, the Bulletin de la Société d’Études et d'Information Économiques published a report which was later taken up by other media.Footnote 81 The Swiss and German press also followed developments with an attentive and benevolent eye.Footnote 82 While other Luxembourg tax arrangements gave rise to media scandals regarding the Luxembourg financial centre from the 1970s onwards,Footnote 83 this was not the case in the interwar period.

Finally, a book published by two legal experts, Bernard Delvaux and Jean Reiffers, was a great success and another way of publicising the new fiscal possibilities. It was first published in 1933 by Luxembourg publisher Victor Bück and was reprinted in the same year by a Parisian publisher. The book received extensive coverage in specialised press outlets such as the Journal des sociétés civiles et commerciales, the Revue de science et de législation financière, the Chronique Hebdomadaire du Recueil Sirey, the Bulletin de la Chambre de commerce de Paris, the Revue de droit bancaire and the Revue des Sociétés. A second edition was published in 1938.

Holding Companies: Open Secrets

Most holding companies were set up in the form of a limited company (société anonyme), to limit shareholder liability. In the literature from the period under study, most authors distinguished between four ideal types of holding company: control holding companies, investment holding companies, asset holding companies and patent holding companies. There was, however, a heuristic gap between these archetypes and the effective functioning of the companies, which were designed to conceal the ways in which capital was recoded in order to produce tax savings. As well as the creation of economies of scale and scope through the financial concentration of geographically dispersed assets, there were indeed other advantages for firms coalescing under a holding umbrella. These included the separation of liability between the parent holding and its controlled subsidiaries or facilitated forms of profit-and-loss consolidation among the holding company's parts.Footnote 84 Some have also argued that investing foreign capital in Luxembourg-domiciled holding companies and converting it to Luxembourg francs could potentially create profit by means of speculation, given the peculiar status of the national currency in Luxembourg and the fact that state financial institutions had scarce, if any, control over it (there was no issuing central bank and it was not listed for trading on the stock markets).Footnote 85 However, at this time, tax avoidance appeared to be the main rationale behind the transfer of financial assets to holding companies in Luxembourg.

Control Holding Companies

Even for the most archetypal form of holding company, control holding companies, tax avoidance was the main rationale for their existence. Of those domiciled in Luxembourg during this period, the best known is undoubtedly that of Ford Europe. The Ford Investment Company was created in May 1930 to minimise the taxes that Ford Europe, located in Great Britain, had to pay. Initially, Ford Europe used a holding company set up in January 1930 in Liechtenstein, but this did not seem to have worked.Footnote 86 In Luxembourg, Ford called upon both well-known and lesser-known frontmen for its board of directors. One of these was Auguste Thorn, who came from a powerful Luxembourg family and was a member of parliament for the Party of the Right; he was the rapporteur for the Holding Act and was on several boards of directors, including that of the Banque Belgo-Luxembourgeoise. The Ford board also contained less publicly known dummy directors provided by the Banque Internationale à Luxembourg. For the BIL this was a lucrative business, not only because of the costs associated with creation and management but also because Ford decided to rent two floors of a new office building that the BIL had just built in the city centre.Footnote 87

This legal construct greatly reduced Ford's tax bill. While for income from sales in the United States, the company used various devices including a structure in Delaware, a US state that had also specialised in tax avoidance over the years,Footnote 88 in Europe, the company's financial affairs were managed by British subsidiary Ford Motor Company Limited, which indirectly owned all Ford's European companies through the Ford Investment Company. This latter entity had been set up in the early 1930s in Luxembourg as a holding company, with the aim of avoiding paying UK tax on the dividends of these continental companies while instead benefitting from the tax exemptions provided by the Luxembourg Holding Act. As Herman L. Moekle, who began working in the Auditing Department of the Ford Motor Company in the late 1920s, put it: ‘It was an operation done solely for tax purposes.’Footnote 89 The holding company was not only used to collect dividends, however; it also served to make loans to Ford Germany and to purchase factories in France. The fact that Ford chose Luxembourg was an important boost to the ongoing publicity campaign led by Luxembourg authorities abroad. In the supplement published alongside the Luxembourg stand at the 1933 World's Fair in Chicago, the article on holding companies mentioned Ford no fewer than four times.Footnote 90 In 1939, the Ford Investment Company was liquidated as a result of the increasing geopolitical turbulence. Its assets were transferred to the Ford Investment Company Limited, located in another offshore financial centre: Guernsey, in the Channel Islands.

Although Ford's holding company has been the largest in Luxembourg, other industrial and financial groups also made use of the Luxembourg system. European subsidiaries of the car manufacturer Citroën were present in Luxembourg through a Swiss company which managed a Luxembourg holding company.Footnote 91 Liebig's Extract of Meat Company Ltd, a food producer based in London, managed subsidiaries set up in other countries via a holding company in Luxembourg. Société Générale de Belgique, a major Belgian company, created Copalux in 1936 to manage ownerships of other companies. However, rumours of the establishment of groups with more substance – in 1938 the Obermoselzeitung reported on the possible establishment of a German-American trust with 300 employees and 500 engineers – proved to be unfounded.Footnote 92

Investment Trusts

From the outset it was thought that H29 would offer considerable leeway for ‘liberal’ interpretation. By looking at the related documents included in the material for the draft Holding Act,Footnote 93 it is indeed immediately clear that it was aimed at a wider range of applications than just more traditional types of holding companies. The holdings (intended here as the financial assets that constitute a holding company) could be ‘in whatever form [original emphasis] . . . these general terms include shares, bonds, advances of funds in the various kinds of companies such as a limited liability company in a foreign country’.Footnote 94 These references to a possible extensive use of the 1929 Act did not fall on deaf ears. As early as 1930, investment trusts began to be listed as holding companies in Luxembourg.

Initially introduced in the United Kingdom and the United States from the second half of the twentieth century,Footnote 95 investment trusts offered their shareholders a form of financial investment in pooled securities issued by companies that, unlike control holding companies, were not necessarily linked to the management choices of a single industrial group or family. Furthermore, investors were given (in principle) a fixed number of shares, which could only be redeemed through the equity market. These are basically the features of what is known nowadays as a ‘closed-end’ investment fund. For example, already in April 1931, the Union Internationale de Placements was listed in the Luxembourg Business Register as a holding company. An analysis of its articles of association and listing dossier, managed by the notary Paul Kuborn,Footnote 96 shows that this company was considered as an investment trust – the New York Times would later refer to the Union Internationale as a closed-end private equity fund.Footnote 97 Behind this fund, there was a group of financiers and financial institutions from France and Germany, including eminent Jewish entrepreneurs from the two countries. Other investors included the Bonnet family behind the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez and the Warburg family that owned the eponymous bank in Hamburg.Footnote 98The redemption scheme of the Union Internationale was de facto closed-end (so with no direct refund of the fund's shares, unlike with open-end funds). Basically, therefore, Luxembourg-domiciled trusts such as the Union Internationale were used as safety deposit boxes for ‘harvesting’ low-taxed capital.

Family Holding Companies

Family holding companies can be considered as a type of holding company that could combine some of the characteristics of a control holding company and an investment trust. Some European capitalist families used Luxembourg as a platform to make tax savings not only on their industrial assets but also on their private wealth. The Pirelli family, for example, managed its cooperation in the telephone infrastructure with Germany's Siemens partly through Luxirti, a Luxembourg holding company founded in 1931.Footnote 99 The French Wendel family administered part of its fortune through the holding company Sopar, created in 1933, and the Swedish Wallenberg family through a system of several holding companies including Luxor, Eskil, Udden and Waseb, all created in 1929.

For the industrial families listed above, holding companies tended to take the form of control holding companies for their industrial assets, of which the family was usually the main shareholder. At the same time, holding companies of this type could have smaller capital size and essentially pool together the financial wealth (not necessarily deriving from industrial assets) of a single family or groups of families – often distributed among the householder, the spouse and even young children. For both categories, tax minimisation was again the principal reason for transferring the tax residency. Contemporary observers all agreed that this was the most widely used model in Luxembourg.Footnote 100 Luc Hommel referred to these holding companies as the ‘middle class’ of holding companies. It was this type of holding company that worried the Belgian authorities in particular. Maurice Houtart, Belgian Minister of Finance between 1926 and 1932, feared an exodus of capital and used the argument of holding companies in Belgian domestic politics to make the case against an increase in taxation in Belgium.Footnote 101 A note from the National Bank of Belgium estimated that in the 1930s, 60 per cent of the capital invested in Luxembourg holding companies came from Belgium.Footnote 102 But family holding companies are also the type of holding company about which the least is known, because they hardly produced any sources.

Patent Holding Companies

Although inextricably linked to industry, patent holding companies should be considered as ‘an appropriate means of acquiring financial participation’.Footnote 103 The capital stock of these holding companies is indeed based on a portfolio of patents. Around one-tenth of all holding companies can be conclusively identified as patent holding companies, typically in the field of engineering patents – especially chemical, mining and electrical. They were in some ways a type of ‘borderline’ (in terms of compliance with H29) holding company. Although the 1929 Act explicitly prohibited any commercial or industrial activities, the whole point of encoding the intangible capital of patent assets through a patent holding company was ultimately commercial. By licensing patents in return for a periodic royalty or percentage fee, patent holding companies were carrying out an operation that could have been interpreted as commercial. However, the purpose of shifting the fiscal situs of the patents of a mining company, for example, was clearly to take full advantage of a system of tax dodging for profits made by a company domiciled in a higher-taxation country through a holding company (which owned the intellectual property) located in a country with low taxation.Footnote 104

Epilogue

Contrary to the conventional historiographical narrative,Footnote 105 the 1929 Holding Act was not a failure because of the economic crisis of the 1930s; quite the contrary. At a time when European states were facing an economic crisis and therefore also a significant increase in their expenditure, they were all trying to increase their revenues. In all of Luxembourg's neighbouring countries, governments were making changes to tax regimes, increasing both tax rates and the number of people taxed. In a way, the economic crisis could even be seen as one of the reasons for the success of the Luxembourg legal solution. The fact that ‘[t]ax avoidance was moving from an activity dominated by a small group of well-advised super-rich individuals to a mainstream upper-middle-class practice’Footnote 106 in several European states during the 1930s is one of the reasons for the rapid growth of the holding company market in Luxembourg. While there was an increasing demand for legal devices that allowed tax avoidance, an offer of national tax friendly codes of capital developed during the interwar period. After the adoption of the 1929 Holding Act, Luxembourg saw the development of a network of lawyers, banks and notaries closely linked to the local political elite that was able to create and maintain an infrastructure of regulatory codes, legal expertise and shell companies that became attractive on a European market of tax avoidance. The strong presence of French and Belgian capital can be explained by Luxembourg's economic integration into this economic sphere after the First World War.

The German occupier decided not to use the Luxembourg holding company system in the financial organisation of its occupation regimes; the archives offer no indication of why this was so. After the war, interest in the scheme was revived. At the beginning of 1945, there were only 473 holding companies with a total of 4.7 billion Luxembourg francs, but this figure increased steadily. In 1952, there were 1,109 holding companies (6.5 billion francs) in Luxembourg.Footnote 107 In 1955, the Banque Générale du Luxembourg, which had been a minor player in the interwar period, created a wholly-owned subsidiary, Crédit Général du Luxembourg, exclusively dedicated to the formation, management and administration of holding companies.Footnote 108 Four years later, the Luxembourg tax authorities took the important administrative decision of granting holding company status to open-ended investment funds, which differed from closed-ended investment holding companies in that they could be exited at any time. This was the beginning of what is now known as the investment fund industry, in which Luxembourg would be the second largest centre in the world by 2023.

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, we can see key elements that can be traced back to Luxembourg's early days as an OFC. On the one hand, there was an innovative and permanent capacity for capital coding, provided for by a specific legislative apparatus combined with large areas of arbitrary power left to the administration and a wide array of private stakeholders such as notaries and business lawyers. In this respect, the lobbying activity of the steel conglomerate ARBED in the 1920s for the adoption of a law ensuring tax avoidance for stock companies can be interpreted as an early expression of a recurrent phenomenon in the history of capital coding in Luxembourg: namely, private companies harnessing the government's law-making power. On the other hand, there was also a close interweaving between the political world (mainly Christian social but also liberal) and concealment infrastructures that allowed liberal fiscal engineering. Catholic-liberal politicians were not only fervent supporters of a holding system designed to enhance state fiscal revenues as an outcome of the tax shopping practices of international stakeholders and companies. They were also directly involved as managers and shareholders of Luxembourg-domiciled holding companies. The development and success of the Luxembourg holding company system, fuelled by a combination of favourable economic conditions, tax avoidance demand, and political involvement, laid the foundation for the country's emergence as a global financial centre in the second half of the twentieth century.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the participants in the Business and Financial History Seminar at the Paris School of Economics for their thoughtful comments, and to the three anonymous reviewers for their very helpful suggestions on a previous version of this article. The article is based on research that is part of ‘Letterbox: Making shell companies visible: Digital history as a tool to unveil global networks and local infrastructures’, a project funded by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) (grant number CORE-C21-SC-15850642).