Societal inequality is related to an increased risk of poor mental health. Reference McDaid and Knapp1 Promotion of equality has been proposed as a cost-effective, preventive intervention that reduces dissatisfaction and anxiety about one's place in society. Reference Geaney2 Article 3 of Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) states that countries ‘undertake to hold free elections at reasonable intervals by secret ballot, under conditions which will ensure the free expression of the people in the choice of the legislature’. The right to vote is therefore a powerful symbol of inclusion or exclusion from society. However, laws intended to ensure that the voting public are capable of making informed political decisions have historically excluded those in hospital with mental health difficulties, even though in-patient voting patterns are little different from those of the community at large. Reference Howard and Anthony3 Previous studies have indicated that although the Representation of the People Act 1983 allowed informal in-patients (i.e. not detained under the Mental Health Act 1983) to register in principle, in practice patients remained disenfranchised, with procedural complexities leading to low turnout (3–8%) Reference Humphreys and Chiswick4,Reference Stanners, Kite, Hargreaves and Burn5 despite high interest (80%). Reference Stanners, Kite, Hargreaves and Burn5 Subsequent changes to the law now allow patients to register from hospital (particularly relevant for those in long-stay units, for example in rehabilitation settings), allow patients detained under the civil provisions of the Mental Health Act and those remanded to hospital under the Act to vote (Representation of the People Act 2000), and allow people to vote in person from hospital (Electoral Administration Act 2006). 6 This study aims to explore whether these changes have helped in-patients exercise their voting rights and to consider how to overcome any barriers to registration that may remain.

Method

Westminster is an inner London borough in which the UK Houses of Parliament are situated. It was awarded city status in 1965 and is therefore also known as the City of Westminster. From 1997 onwards the borough has been represented in parliament, currently by the constituencies of Westminster North and Cities of London and Westminster.

A total of 152 in-patients resident in Westminster were identified across 12 general adult psychiatry wards within Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust. The sites surveyed included nine acute general adult in-patient wards, one in-patient eating disorder unit and two community-based rehabilitation units. A clinician-completed survey on patient voting rights was carried out with each patient between 23 April 2010 and the day of the election, 6 May 2010. Patients unavailable or not able to participate in the initial phase were identified and surveyed again during a second phase, which lasted from 7 to 21 May 2010. The questionnaire asked between 7 and 16 questions guided by patient responses. Patients who reported that they had registered for the general election were followed up to see whether they had subsequently cast their vote. Where a questionnaire was incomplete, all available answers were added to the study data. Total sample sizes therefore varied slightly for individual questions, whereas overall participation was defined as a questionnaire where at least two-thirds of questions had been answered. Patients on extended Section 17 leave, those absent without leave, or those on day leave on at least two occasions were considered partially or completely community based and excluded from the study.

We used the χ2-test with Yates’ correction (GraphPad Prism 5.04 software for Windows) to compare registration and voting rates within the sample population with Westminster and national populations, and to compare registration rates between short- and long-stay in-patient groups.

Results

Sample

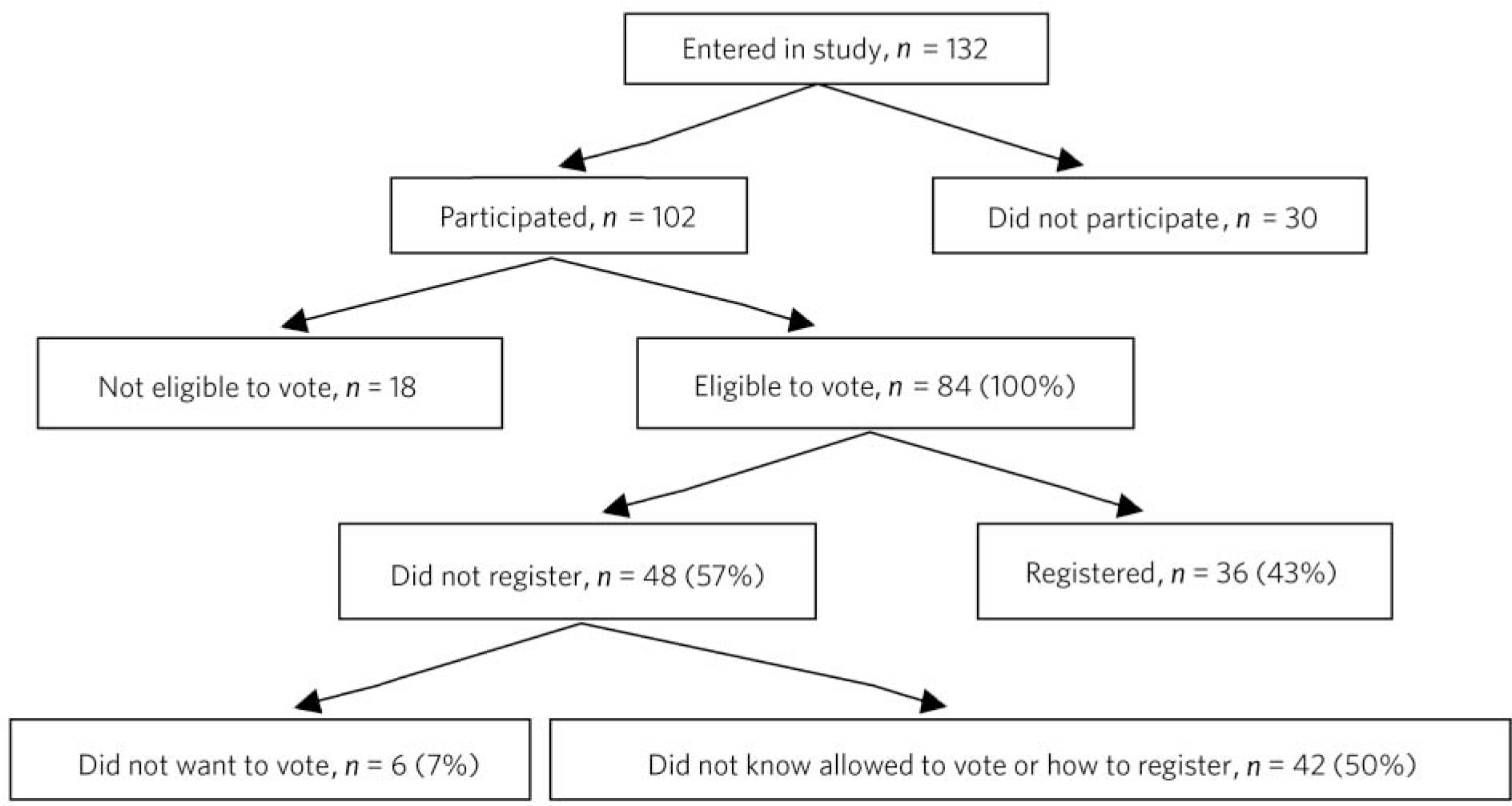

A total of 152 nominal ‘hospital’ patients were identified on 23 April 2010, of which 20 were in the process of transition to the community and were excluded from the in-patient study. Of the 132 resident patients, 102 (77%) participated. Among the remaining 30 patients, 20 refused to participate, 6 were too unwell and 4 were recurrently unavailable. Of the 102 patients who participated, 84 were eligible to vote and 18 were not, either because they did not meet nationality requirements or because they were detained as a result of criminal activity (Fig. 1).

Fig 1 Voting behaviour of Westminster in-patients.

Demographics

Of the 84 eligible participants, 46 (55%) were male and 38 (45%) female. The median age was 39 years (range 20–71; interquartile range (IQR) 30–49). Over half (n = 54, 64%) were White, 17 (20%) were Asian/Arab, 11 (13%) were Black African/Caribbean and for 2 (2%) ethnicity was not recorded (Fig. 2). As regards nationality, 54 participants (64%) were British (including Arab, Bangladeshi, Caribbean, African, White, other), 28 (33%) were not British and for 2 (2%), nationality was undefined. A higher proportion of ethnic minority groups were represented in this in-patient sample than in the Westminster population as a whole, where in the 2001 census 74% were identified as White and 26% as Black and minority ethnic. 7

Fig 2 Ethnic background of study participants.

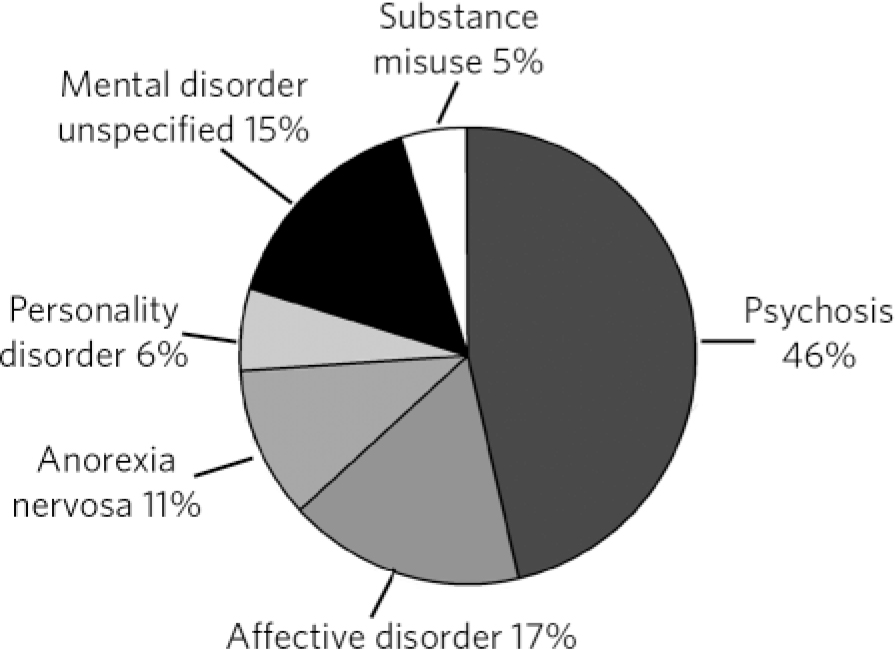

The most common diagnosis in the sample was psychotic disorder in 39 patients (46%), followed by affective disorder in 14 (17%), unspecified mental disorder in 13 (15%), anorexia nervosa in 9 (11%), personality disorder in 5 (6%) and a disorder secondary to substance misuse in 4 (5%) (Fig. 3).

Fig 3 Study participant diagnosis.

Just over half of participants (n = 47, 56%) were detained under Section 3 of the Mental Health Act, 29 (34%) were informal, 8 (10%) were detained under Section 2, and no one was detained under the forensic sections which leave the person eligible to vote: 35, 36, and 48. (In England and Wales offenders detained under sections 37, 38, 44, 51(5), 45A, 46, 47 are not eligible to vote under Part 1, Section 2 of the Representation of the People Act 2000. This Act further details those sections under which patients detained in Scotland and Northern Ireland are deemed legally incapable of voting.) There were 67 patients on general adult wards, 9 on the eating disorder unit, and 8 on the rehabilitation units. Median length of admission prior to survey was 2 months (IQR = 1–5.75).

2005 election

In the 2005 election, 32 (38%) of the 84 patients eligible to vote had voted. This compares with a national turnout in the general population of 61.3%, and 50.7% in Westminster (the Cities of London and Westminster constituency). 8

2010 election

In the 2010 election, 55 (65%) of the 84 patients eligible to vote said they were interested in voting. However, only 36 (43%) had actually registered, whereas 48 (57%) had not. Of the 36 patients who had registered, 34 responded to questions on voting options: no one had registered to vote from the hospital address or used the proxy voting option, 6 elected to vote by post, whereas most (n = 28) had organised to vote in person, an option not available for in-patients before 2006.

Patients not registered to vote

Of the 45 people who had not registered to vote and 3 who were unsure (n = 48), only 6 (12%) had made an active decision not to register, either because they ‘did not believe’ in politics, did not want to vote, or did not believe there were any good candidates. The remaining 42 (88%) cited a lack of relevant knowledge.

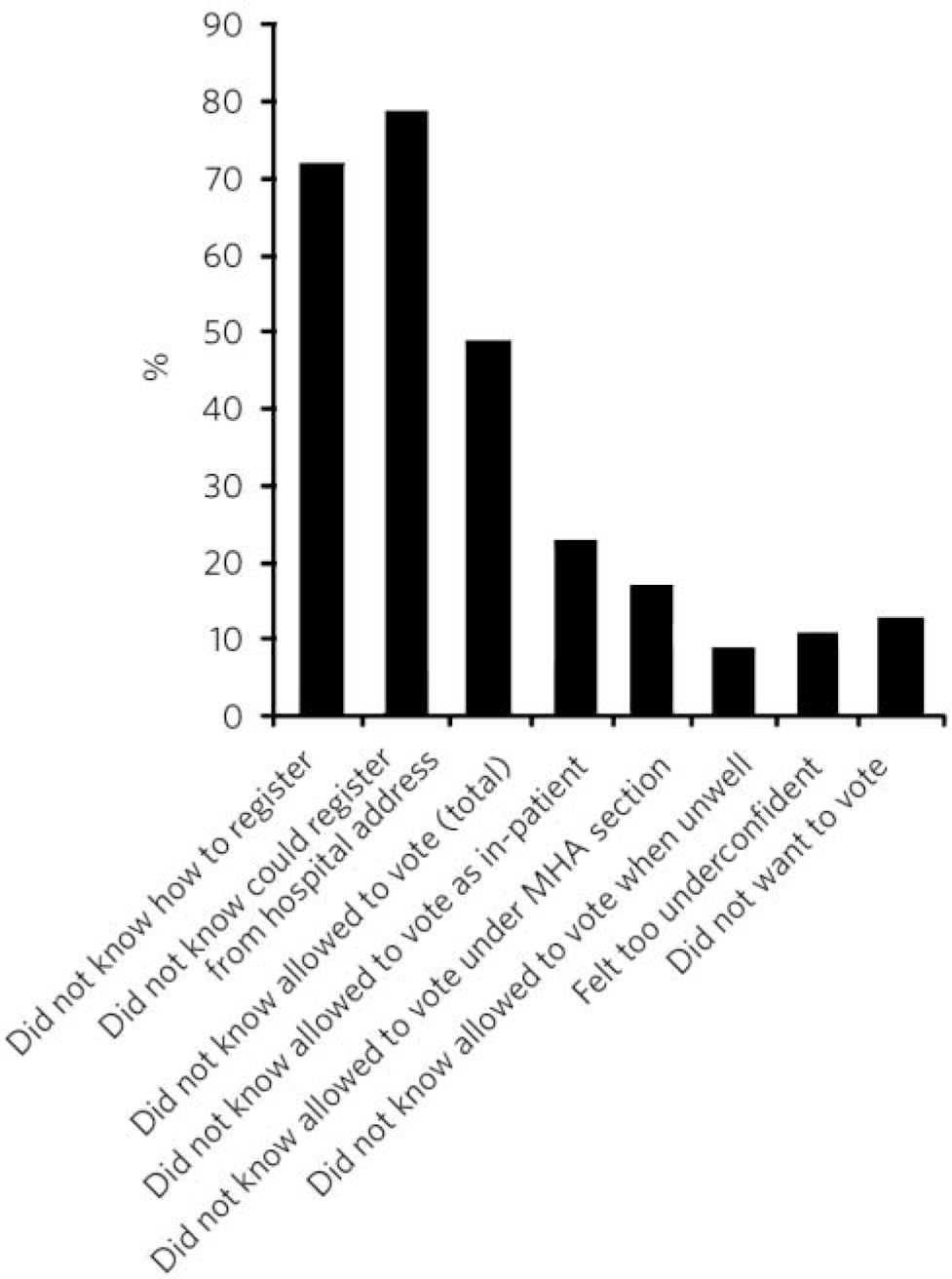

The patients who had not registered to vote or were unsure whether or not they had registered tended to describe several areas of confusion regarding their eligibility to register or the registration process. To sum up, 34 (71%) did not know how to go about registering to vote, 37 (77%) did not know they could register using the hospital address, 23 (48%) did not know they were allowed to vote and 5 (10%) did not want to vote because they felt they did not know enough about the candidates and politics, and so did not feel confident to make a decision (Fig. 4). Patients who did not know they were allowed to vote (n = 23) cited various reasons why they believed this was so: 11 (50%) thought they were not allowed to vote while an in-patient, 8 (35%) thought they could not vote while detained under a section of the Mental Health Act and 4 (20%) thought that it was when they were unwell with a mental illness. Overall, 24 (50%) of the 48 people who had not registered or were unsure said they would have done so if they had known how.

Fig 4 Reasons for in-patients not registering to vote in the 2010 UK general election. MHA, Mental Health Act.

Patients registered to vote

Of the 84 participants eligible to vote, 36 (43%) had registered. After the election, 33 of those registered were traceable for follow-up: 11 voted and 22 did not, which gives a 33% voting rate among this group. The remaining three patients had moved out of area, moved abroad or requested to have no further contact with mental health services following the initial survey. Assuming patients not contactable at follow-up had the same voting rate as the 33 who participated, then 33% of the 36 registered patients would have voted (n = 12). This represents 14% of the original 84 eligible in-patients.

Psychiatric in-patients in this study were half as likely to be registered as the general population (43% v. 97%), 9 and if registered, half as likely to cast their vote (33% v. 67%). 9 Ultimately, voting rates among in-patients in our survey are a quarter that of the general population (14% v. 65%). 9 Registration and voting rates appear lower in the Westminster than the UK general population: 71% of the Westminster electorate (133 228 of 188 471) registered, and of those, 43% (57 233) voted. 10 This may reflect a relatively transient population (16% resident for less than 2 years), 11 a higher proportion of people from an ethnic minority background (26% v. 8% nationally), a higher young adult population (56% of 17- to 25-year-olds are not registered to vote), 12 and lower over-60s population 7 (95% of those over 60 are registered to vote). 12

Statistical analysis of factors

The difference in registration rates between psychiatric in-patients in our sample (43%) and the total population figures for the 2010 general election 9 (97%) was statistically significant (χ2-test, P<0.0001); and it was also significant (χ2-test, P = 0.0002) in comparison with the registration rate of the Westminster population (71%).

The difference in voting rates between registered psychiatric in-patients (33%) and the voting rates of the registered general population (67%) was significant (χ2-test, P = 0.0014). Although voting rates of registered in-patients were also lower (33%) than those of the registered Westminster population (43%), this did not reach statistical significance (χ2-test, P = 0.35). This indicates that the main barrier to voting for psychiatric in-patients in this study was the registration process.

Registration rates between patients resident <3 months (defined as short stay) and those resident >3 months (defined as long stay) varied and the difference was significant (χ2-test, P = 0.01). The median stay was 1 month in the registered group (IQR = 1–3) and 3 months in the non-registered group (IQR = 1–8). There was no significant difference found in registration rates between different ethnic groups: White v. Black and minority ethnic (χ2-test, P = 0.52), British v. other nationalities (χ2-test, P = 0.47).

Discussion

Promoting voting rights of people in hospital with a mental illness supports the human right to be part of free elections, and may help to diminish a sense of exclusion and inequality that many people with mental health difficulties experience. In this context, the right to vote and the process of voting may be considered a Vygotskian sign, Reference Leiman13 conveying meaning both to a person carrying the burden of mental illness and to society as a whole that one is of value not only when ‘in remission and well’ but also when one's illness is active.

The implications of ‘the right to free and fair elections’ under the ECHR were reviewed in Hirst v United Kingdom at the European Court of Human Rights 14 with regard to the rights of convicted prisoners to vote. The Court indicated that the right to vote was not absolute, yet it stressed that under Article 3 of Protocol 1, ‘the right to vote was a right and not a privilege’ and that ‘any limitations on the right to vote had to be imposed in pursuit of a legitimate aim and be proportionate’. Furthermore, there was no question that a prisoner should forfeit their Convention rights merely because of their status as a detainee following conviction, and consequently a blanket ban was unlawful.

With regard to mentally ill offenders, the first government consultation on this issue asked whether voting rights given to prisoners detained in mental hospitals should be determined on the same basis as for ordinary prisoners, or whether there were categories that should be treated exceptionally. Disappointingly, the majority of the 88 respondents to this consultation exercise chose to submit a ‘not applicable’ answer, which was felt to reflect limited clinical knowledge. 15 Factors contributing to an offence (e.g. whether or not the offence was related to mental illness) and the aim of detention (punishment and rehabilitation of an offender v. the assessment and treatment of a mental disorder) are different for the offender with and without a mental illness. Unfortunately, it appears that little thought is being given to the need to consider the right to vote for forensic patients separately from that of the general prison population, and mentally ill offenders are likely to continue to risk being caught up in future measures designed to justify punitive disenfranchisement of prisoners.

The opportunity and expectation to vote is an example of a wider process that may be worth emphasising as it indicates a role for promotion of health by acceptance and expectation rather than intervention. Social labelling theory Reference Waxler16 considers that a sick person, for whom symptoms are usually a new and inexplicable experience, takes cues from those around him or her and so plays a culturally expected role. Consequently, higher functional expectations of society may ‘allow’ a better outcome. This is consistent with the finding that the lowest-income countries (per capita gross national product of less than US$2966) which have a higher expectation of those with mental illness appear to have a better prognosis in terms of recovery and recurrence rates. Reference Saha, Chant, Welham and McGrath17

Apart from a role in promoting social inclusion, voting gives people a political voice and allows them to exert political pressure. A vote in this context is more than a choice of party or candidate; it is a motivation for politicians to understand and support issues relevant to those with mental illness. Reference Fitch, Daw, Balmer, Gray and Skipper18

Procedural complexities in the registration and voting system for people being treated in a psychiatric hospital were, in previous studies, considered a major contributory factor in the disparity between high levels of voting interest among patients (80%) Reference Stanners, Kite, Hargreaves and Burn5 and low registration rates (4.8–6.3%). Reference Dyer19 A number of procedural barriers to in-patient voting have been lifted over the past decade: people can now register from a hospital address, register while detained under civil provisions and while on remand, and can vote in person from hospital. These changes appear to be reflected in our survey in a higher than in previous elections number of patients who have been able to register independently (43% v. 4.8–6.3%), Reference Dyer19 a higher proportion who were eligible to vote (65% of participants were detained under the Mental Health Act and would not have previously been eligible), and a higher proportion who could vote in a manner they felt comfortable with (80% wanted to vote in person, whereas only post or proxy options were available to psychiatric in-patients before 2006).

Informational barriers still remain. A minority of people in the study had registered (43%) to vote, in contrast with 97% of the eligible general population 9 and 71% of the Westminster population. 10 The discrepancy in registration rates was associated with a reported lack of knowledge: in our survey, nine out of ten of those not registering were unaware either that they could vote or how to go about the registration process (Fig. 4). Furthermore, only seven people (8%) received relevant information prior to the election, and only one (1%) in writing. This may reflect a lack of knowledge not only on the part of the patients but also on the part of the professionals involved in their care. Reference Rees20

Of those who registered, only a third then voted. This represents an improvement from previous elections where 3–8% of in-patients voted. Reference Humphreys and Chiswick4,Reference Stanners, Kite, Hargreaves and Burn5 In comparison, two-thirds of the registered general population (67%) 9 and 43% of the Westminster population 10 cast their vote. This implies that to vote patients have to overcome a further barrier. This may be related to symptoms of illness such as paranoia, anxiety and reduced motivation, a lack of confidence in making a voting decision, or a belief that the political system will ignore their concerns and does not value them – a psychological barrier. It may also indicate the presence of physical barriers to voting such as staffing and transportation issues on the day of the election, which may have prevented some patients from attending a polling station.

There is a statistically significant correlation in our sample between prolonged length of stay (>3 months) and decreased electoral registration. It is also notable that no one in the study opted to register from their hospital address, and no one on the rehabilitation wards, where the mean stay was 15 months, had registered. Long-stay patients may not be able to register from a home address and do not take up their right to vote from hospital.

Ethnic minorities also have low rates of electoral registration. Reference Nash21 However, we found no significant difference in registration rates based on ethnicity. This may be a reflection of the small sample size. People with dementia or an intellectual disability have also been identified as a group in which many may have wanted to vote and had the capacity to do so, but may not have had the opportunity. Reference Redley, Hughes and Holland22 There may be other reasons that affect registration behaviour that we have not recognised, and there are barriers to voting once registered that remain unclear. There appears to be a role here for qualitative research to further explore these factors.

This study demonstrates that people with mental health difficulties remain engaged with the political system. However, many patients and staff remain unaware of the rights of mental health in-patients to vote and may remain ignorant of the registration process. Reference Rees20 We encourage in-patient facilities to provide timely written guidance to both staff and patients on eligibility criteria, voting rights and the process of registration well before future elections. Patients will then require support and encouragement to turn their polling card into a vote. We believe that the government and the Care Quality Commission have a responsibility to support and monitor this process.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Naz Daniels and Dr Ajay Vijaykrishnan for their help gathering data for this study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.