This article examines the growth of Chinese exports to the Indian Ocean from 1684 until the mid eighteenth century. It argues that from that year until about 1715 the bulk of the Chinese goods that eventually entered the Indian Ocean were channelled through Southeast Asian entrepôts. Around 1715 this situation began to change. During the decade that followed, several disparate factors combined to encourage more merchants based in South Asia to sail directly to Chinese ports. The growing number of these direct voyages shifted commerce away from the indirect entrepôt system by prompting the development of trade routes that bypassed Southeast Asian port cities.

The crucial context in which trading links between China and South Asia began to redevelop in the latter part of the seventeenth century was the expansion of maritime commerce in both regions. The mid to late seventeenth century saw a boom in Indian Ocean trade, marked by the emergence of several important entrepôts that dominated commerce in their own sub-regions, including Surat in Gujarat, and Madras, Porto Novo, and San Thome on the Coromandel coast. Footnote 1 In these centres, groups of Hindu, Muslim, and Christian Armenian merchants expanded their trading networks to the shores of the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the western edge of the Bay of Bengal. These traders were also joined by private European merchants who had become a respectable force in the region’s systems of exchange by the last quarter of that century. Footnote 2 On the other side of the Malay peninsula, the critical factor was the Qing Kangxi emperor’s decision to legalize maritime trade in 1684. This move prompted an almost immediate surge in the numbers of Chinese merchant vessels sailing abroad, initially primarily to Japan and Luzon, but within a few years to a number of important commercial hubs in Southeast Asia as well. These hubs formed the basis of a new trading network in the region that distributed goods from China to other markets within Southeast Asia and beyond it. Footnote 3

After 1684, the two Southeast Asian cities that became instrumental in channelling Chinese trade goods into the Indian Ocean were Johor, a sultanate at the southern tip of the Malay peninsula, and Ayutthaya, the capital of Siam. Both were major centres within the western part of the post-1684 Chinese maritime system in Southeast Asia, and at the same time they were connected to the trading networks of the Indian Ocean. Vessels based out of Xiamen, Guangzhou, and Ningbo sailed to the two places to acquire Southeast Asian products in exchange for their Chinese goods, which included tea, porcelain, silk, zinc, and copper. Some of the Chinese goods were consumed within Siam and Johor themselves, while others were re-exported to their smaller surrounding markets in the Melaka Strait region, western Borneo, the upper Malay peninsula, and Cambodia. Another portion of the goods were traded to South Asian-based merchants who came either directly to Johor and Ayutthaya or to secondary centres within their sub-regions, such as Aceh and Mergui. These goods were then reshipped into the Indian Ocean, destined for the consumer markets of South Asia.

From 1684 onwards, small numbers of ships sailing from South Asia also began to arrive in China to trade directly for goods. These ships were initially primarily British-owned private vessels from Madras, and their numbers were usually limited to two or three per year. However, around 1715 a number of factors converged to prompt a growth in this direct trade and a diversification in the origins of the South Asian-based ships. First, there were political changes in both Johor and Siam that undermined their abilities to act as emporia. Johor became the object of a three-way war that involved a dangerous amount of maritime raiding, while the management of foreign trade in Siam fell under the control of a venal bureaucrat. Second, in 1716, the Qing Kangxi emperor prohibited Chinese ships from sailing to most of Southeast Asia. The ban was only rigorously enforced from 1717 to 1722, but the absence of Chinese ships during these years encouraged other merchant groups to step into the breach. Finally, the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) ended, which increased the availability of silver for European companies and private merchants, while also making the sea routes to and through Asia much safer.

Consequently, direct trade between China and South Asia began to grow rapidly, while indirect trade through Johor and Ayutthaya stagnated or declined. The private (meaning non-East India Company) British merchants from Madras, who had had the direct trade more or less to themselves from 1684 to about 1715, were joined by several other groups after the mid 1710s. Private British merchants based out of other parts of South Asia, especially Bombay, noticed the success of their counterparts in Madras and sought to emulate their business in China. Macau’s merchant community also began to use Madras as a base in South Asia to collect silver and cargoes of Southeast Asian goods, while buying pepper for the China market on the Malabar coast as well. Likewise, French traders, mostly based out of Pondicherry, entered the fray by beginning almost annual voyages to Guangzhou in the early 1720s. Other national groups contributed to a lesser extent, and together these merchants gradually built up a trading system based on the direct transport of goods between China and South Asia that continued through the course of the eighteenth century.

In making these arguments, this article consciously attempts to transcend the boundaries of traditional regionalization and see the evolution of the trading patterns between China and South Asia from a global historical perspective.Footnote 4 Despite a growing appreciation for the new possibilities that global historical perspectives bring to the questions of trade and other sorts of economic entanglement, relatively little work has been done tracing trans-regional connections from China’s shores to the Indian Ocean during the early modern period.Footnote 5 The most significant work is still that of K. N. Chaudhuri, who took Fernand Braudel’s study of the Mediterranean as his model and sought to describe the deeper structures of interaction that bound together a greater Indian Ocean, stretching from the Cape of Good Hope to Japan, over the longue durée.Footnote 6 Since Chaudhuri, very few studies have attempted to bring both early modern maritime China and South Asia into one narrative. Thanks to the pioneering works of Leonard Blussé, Anthony Reid, and other Southeast Asianists, the commercial impact of Chinese trade across that region, especially after 1684, is now widely appreciated.Footnote 7 A smaller number of South Asianists and Southeast Asianists have also shown how merchants from the Coromandel coast, Gujarat, and Bengal began to trade in various parts of Southeast Asia at the same time.Footnote 8 However, the tendency to focus on a particular group of merchants rather than the flow of goods and silver has meant that the ways in which China and South Asia were connected through Southeast Asia are rarely analysed. This article seeks to bridge the gap between these separate regional perspectives by showing how the interactions between a number of different groups across the three regions (private merchants in Madras and Bombay, the Macanese, the Qing government, Bugis invaders in Johor, Siamese officials charged with managing trade, and so forth) interacted with one another and transformed trans-regional trading patterns.

Although the article follows Chaudhuri’s call to find the connections between the far-flung parts of maritime Asia, it is explicitly not a study set in a Braudelian longue durée. The key argument here is that a very specific series of events combined to create the economic connections between maritime China and South Asia at the end of the seventeenth century and beginning of the eighteenth, starting with the Qing empire’s decision to legalize maritime trade in 1684. The processes that began to connect the two regions were unique to that historical moment, and were the product not of deeper structural forces re-emerging, but of the particular political and economic conditions existing in China, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.

In regard to the question of globalization itself, the growth and transformation of the trading patterns between China and South Asia described in this article can be compared to the development of trade between Europe and other parts of Asia in the same period. The current debate over the question of globalization, summarized nicely by Jan de Vries in 2010, is primarily focused on the connections between Europe and Europe’s American colonies, Asia, and Africa. The debate is over the questions of when and if these connections between Europe and the rest of the world were sufficient to be considered an early modern ‘globalization’.Footnote 9 Proponents of a ‘hard’ definition of globalization, especially Jeffrey Williamson, Kevin O’Rourke, and Peter Lindert, claim that, in the case of Europe’s connections to Asia, although there was an intensification of trade over the course of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, the prices of different products in the two regions did not converge until the nineteenth century. In their view, this lack of price convergence meant that these spatially separated markets were insufficiently integrated for the trade to be considered a globalization. According to them, price convergence failed to happen partly because the trade was dominated by monopolistic European companies who managed the supply of high-value-per-bulk Asian goods in their home markets in order to maintain a healthy mark-up on prices, and partly because the imported Asian goods usually did not compete with local European products.Footnote 10 Historians arguing for an earlier ‘soft’ definition globalization admit the lack of price convergence between Europe and Asia before the nineteenth century, but argue that a broader definition of globalization is more useful. Essentially, rather than relying on one statistical measure, such as price convergence, they look for sustained economic interaction between different parts of the world that ‘deeply and permanently linked them’.Footnote 11

In the case of the trade that developed between China and South Asia after 1684, the fact that it was dominated by private merchants from a wide variety of backgrounds rather than the large record-obsessed companies means that demonstrating a hard globalization through price convergence will be extremely difficult. This article focuses on the development of trade routes and does not attempt an analysis of prices or consumption patterns. However, it shows that during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries the growing diversity of participation in the trade and the absence of monopolies meant that the primary reason why Williamson and his co-authors believe that price convergence did not happen between early modern Europe and Asia does not apply to the China–South Asian trade. If the monopolization of imports by companies was truly the primary obstacle to price convergence between Europe and Asia, then trade between China and South Asia may have come closer to satisfying the criteria for the advent of a harder globalization. At the very least, the emergence of regular direct trade between China and port cities in several different parts of South Asia (Madras, Bombay, Surat, and Cochin, especially) indicates that there was a sustained economic interaction at least equivalent to the soft globalization processes occurring between Europe and China, and Europe and South Asia.

Before proceeding to the body of the article, I need to acknowledge its debts to the earlier studies of two historians. First, I rely on George Bryan Souza’s examination of Macanese traders in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean to evaluate their contribution to the development of direct Chinese–South Asian trade. Souza shows that the traditional Macanese trade in East and Southeast Asia was badly compromised by the legalization of private Qing trade in 1684. The Macanese therefore began searching for new markets and products that would allow them some competitive space as importers to and exporters from the Chinese market. One solution they hit upon was to focus a substantial part of their activity carrying trade between the coast of China and the Indian Ocean, where Chinese ships did not sail.Footnote 12 Souza’s analysis, though focused exclusively on the Macanese, illustrates one example of the shift from indirect to direct trade between China and South Asia. In the present article, I will attempt to situate his findings within the development of the larger patterns of trade between China, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean, and show how South Asian-based merchants joined the Macanese in the development of direct trading routes between the two macro-regions.

Second, the article draws upon and modifies Sinnappah Arasaratnam’s description of the basic changes occurring in the organization of trade between Southeast Asia and the Coromandel coast beginning in the 1720s. According to Arasaratnam’s assessment, in that decade a triangular trade developed between the Coromandel coast, China, and Southeast Asia, in which merchant ships, especially British ones, began to sail in increasing numbers directly to China to purchase goods for South Asian markets. In the meantime, merchants from the Coromandel coast participated by trading in Southeast Asia for local products, especially tin, which were then brought back to their home ports and sold for re-export on the British ships headed to China.Footnote 13 Arasaratnam’s general description of this new system is well supported by the evidence, but he offers little in the way of explanation of the specific mechanisms that brought about these changes in Asia’s trade. The goal of this article, therefore, is the identification of those mechanisms within the political and economic histories of China, South Asia, and western Southeast Asia. It also concludes that the shift probably began a bit earlier than Arasaratnam’s conservative estimate of the 1720s, and that, although direct trade from the Indian Ocean to China did begin primarily with British ships sailing from the Coromandel coast, participation quickly became more diverse.

The eclipse of the indirect routes through Southeast Asia

In the late seventeenth century Ayutthaya, the Siamese capital, and the sultanate of Johor on the tip of the Malay peninsula became critical trading emporia for both Indian Ocean merchants and the Chinese trading network. Johor was probably the more important of the two routes. It was an extremely attractive destination for China-based merchants because it was then the commercial hub of the Melaka Strait sub-region. Short-distance traders connected it to the major pepper- and tin-producing areas on the east coast of Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and the islands between them, making these two types of highly marketable goods readily available to the Chinese ships that docked in its harbours. Johor’s link through the Strait of Melaka to the port city of Aceh on the north-western tip of Sumatra was its other major advantage. Aceh was a relatively large market by Southeast Asian standards, and it was also an emporium in its own right, linking Southeast Asia to the Indian Ocean. In the late seventeenth century, some of the Chinese goods that were unloaded in Johor each year were typically reshipped to Aceh on smaller vessels commonly operated by ethnic Chinese merchants based in the Melaka Strait region. There, South Asian merchants would trade for the Chinese goods and then reship them to their home markets on the Coromandel coast, the Malabar coast, Bengal, or Gujarat.Footnote 14

For Johor, this advantageous position between the South China Sea and Aceh meant that, as long as its rulers were able to maintain a stable commercial environment, the Johorese were able to control much of the trade passing between the two oceans. Despite occasional political upheaval, from the late 1680s until the late 1710s the stability of the commercial environment in Johor seems to have endured. However, the situation changed in 1718 when a pretender to Johor’s throne, known in history as Raja Kecil, invaded from Sumatra. Had this pretender been able to establish his rule swiftly and firmly in Johor, the old patterns of trade might have continued with only a short interruption. Unfortunately for him, and for all the merchants who had a stake in the region’s commerce, his invasion began a long and destructive struggle for control of the sultanate’s former territory between his forces and those of a number of opportunistic Bugis warlords who had immigrated from Sulawesi and established themselves in the southern Malay peninsula.Footnote 15 Both sides committed piracy, hampering commerce in general, and, according to a nineteenth-century Malay history of the Bugis rule of Johor, Raja Kecil himself actively attempted to disrupt trade in an effort to deny his opponents its benefits.Footnote 16 Raja Kecil was finally defeated in 1728, and the same Malay history tells us that, from that time, Johor once again began to prosper as a commercial hub.Footnote 17 A Chinese guide to foreign lands published in 1730 agrees that there was then enough trade annually to accommodate the business of three or four long-distance trading vessels from China.Footnote 18

However, this recovery in Johor does not seem to have undone all the damage that the decade of warfare in the region had caused. In particular, the once crucial trade with Aceh never revived. In part this may have been because of political turmoil that occurred in Aceh around 1727, when a separate group of Bugis took power there as well.Footnote 19 But the Bugis takeover was probably not the main reason; European and South Asian ships continued to arrive in Aceh during the 1720s and 1730s despite the unsettled political situation.Footnote 20 The problem seems to have been that the logic of Asia’s maritime trade had changed by the end of the long war for control of Johor. When the British East India Company employee Charles Lockyer visited Aceh in 1704, he found the city glutted with Chinese products, and suggested that the company could purchase them there.Footnote 21 Two decades later it was the British who were selling rather than buying Chinese goods in Aceh. A memorandum from 1719 or 1720 in the notes of the private Madras-based merchant John Scattergood lists Chinese goods that he intended to buy in Guangzhou for resale in Aceh.Footnote 22

The absence of Chinese goods in Aceh and Melaka is also attested to by an essay on Bengal’s trade with other parts of Asia written by an anonymous employee or associate of the Ostend company sometime in the late 1720s or early 1730s. According to this writer, for South Asian-based merchants Aceh supplied gold, pepper, benzoin (an incense made from tree resin), camphor, and other drugs, while Melaka could supply tin, rattans, benzoin, dammer (a tree resin used in place of pitch), camphor, pepper, gold, and goods that had been brought from Batavia. In neither case does the writer mention Chinese goods or the participation of Chinese merchants, and tellingly there is no discussion of Johor in his essay at all.Footnote 23 Even as late as the 1760s, when Johor had once again become a major emporium for Chinese trade, Aceh was still outside the Chinese maritime trading network in Southeast Asia. Thomas Forrest, who visited Aceh intermittently in the late eighteenth century beginning in 1762, states that he never saw any Chinese in the city, and suggests that this may have been because they had been commercially outcompeted by Muslim South Asian merchants.Footnote 24 His statement implies that Aceh had been cut off from even the ethnic Chinese immigrant communities in Southeast Asia who had previously been responsible for carrying much of the trade between Johor and Aceh.

There were several reasons, therefore, that trade between Johor and Aceh did not recover. Increasing commercial activity in South Asia during the mid eighteenth century probably reoriented Aceh’s economy away from the Chinese trading network towards the Indian Ocean, as Forrest suggests.Footnote 25 Raja Kecil and his followers were also a persistent problem for trade through the Melaka Strait. Despite his defeat and withdrawal to eastern Sumatra in 1728, the pretender remained a threat to the new regime in Johor until the 1740s, frequently raiding its territories from Sumatra.Footnote 26 Consequently, lightly armed merchant vessels operating out of Johor would have found the passage north through the strait to Aceh much riskier in 1730 than they had in 1710. Finally, Aceh’s potential role as an entrepôt that made Chinese goods available for South Asian-based merchants was greatly reduced by a large increase in direct trade between Guangdong and various South Asian ports that occurred after the 1710s, as we will see.

In Siam, Ayutthaya was also an important emporium visited by both Chinese and South Asian merchants after 1684.Footnote 27 In the kingdom there was no political or military disturbance in the early eighteenth century that disrupted trade comparable to what occurred in Johor. The obstacle to the relay of Chinese goods through Ayutthaya towards the Indian Ocean that arose in the second decade of the eighteenth century came from the state’s administration of trade. The main culprit was an ethnic Chinese phraklong, or harbourmaster,Footnote 28 who gained his office thanks to the favour of the Siamese king Somdet Phrachao Sua (r. 1703–09), but achieved the height of his power during the reign of Sua’s successor, Thai Sa (r. 1709–32). During Thai Sa’s reign, this phraklong used his position as the principal authority over both foreign relations and the administration of trade to shift the relatively fair and open policies that had prevailed before the Thai Sa period to ones that made business difficult for certain merchants and merchant groups. Dutch and French observers accused him of a national bias, claiming that he championed the interests of Chinese merchants at the expense of traders from other regions.Footnote 29

Despite these accusations, the phraklong was probably not primarily a Chinese chauvinist. He was an investor in maritime trade himself, and his primary goal was likely not an expression of Chinese solidarity but the promotion of his own commercial interests at the expense of his potential competitors.Footnote 30 He was interested in promoting trade between China and Siam because his own ships were among those plying that trade route, as the British East India Company discovered in 1715 after a British merchant seized a ship that happened to belong to the phraklong in Xiamen’s harbour.Footnote 31 He appears to have had a similar stake in trade with Japan. The crew of a Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) ship reported to the interpreter in Nagasaki that the phraklong was already using his position in the Siamese government to dominate the animal hide trade to Japan with his own vessels by 1707, presumably to the detriment of both the Dutch company and other Chinese merchants who traded in Nagasaki.Footnote 32

In some cases, certain non-Chinese traders seem to have benefited from the phraklong’s interests. Alexander Hamilton, a private British merchant who visited Siam in 1719, claimed (without referring to the phraklong directly) that the administrators of trade there had colluded with John Powney, another private British merchant who was serving as the agent of Joseph Collett, the president of the East India Company’s establishment in Madras. According to Hamilton, their plot was to make trade in Siam prohibitively expensive to all British merchants not affiliated with Powney and Collett.Footnote 33 Powney, as it happened, was then Collett’s representative in the negotiations concerning the seizure of the phraklong’s ship in Xiamen in 1715. Collett was hoping to arrive at a mutually acceptable settlement with the phraklong, and had thus authorized Powney to offer him compensation for the loss of his ship. For the phraklong, the desire for compensation was an obvious inducement to maintain a good relationship with Powney, but it did not give him any reason to encourage Hamilton or other any private British merchants.Footnote 34

This favouritism, whether on behalf of Chinese or European affiliates of the phraklong, appears to have been bad for trade with the Indian Ocean’s merchants in general. Despite Siam’s relatively large population and deep markets, there was rarely more than one British merchant from Madras or Bengal that came to Siam each year.Footnote 35 The VOC’s agents in Ayutthaya frequently complained that operating their factory in the kingdom almost always brought a net loss, but they acknowledged that the British and ‘Moor’ (Muslim South Asian) merchants were generally treated even worse than they were.Footnote 36 French missionaries in Siam likewise reported to their compatriots in Pondicherry that under the phraklong’s regime there was little hope for successful French trade in Siam.Footnote 37 The consequence was that, while trade between Siam and China remained healthy during Thai Sa’s reign, fewer South Asian-based ships visited Siam compared to earlier periods. This circumstance meant that Ayutthaya’s function as a conduit for Chinese goods into the Indian Ocean did not expand and may well have declined during Thai Sa’s reign when the phraklong had a free hand in the management of the kingdom’s foreign trade.Footnote 38

As Johor and Ayutthaya’s roles as entrepôts for trade between South Asia and China became limited for these internal reasons, the Qing Kangxi emperor also unintentionally prompted the shift away from indirect trade with South Asia in the last years of his reign. Concerned about the possibility of anti-Manchu conspiracies being hatched between overseas Chinese traders and Europeans, as well as the export of rice and ships, the emperor placed a ban on all voyages by Chinese vessels to Southeast Asia in late 1716. The ban was only strictly enforced until the emperor’s death in 1722, but it naturally disrupted the trading system that had developed after 1684.Footnote 39 Consumers across Southeast Asia who had come to rely on annual deliveries of Chinese goods found themselves suddenly cut off, while merchants in China were unable to export their cargoes. Despite the emperor’s concern about Europeans working to undermine his government, their ships, as well as South Asian ones, were still allowed to dock in Qing ports. So naturally the problems in Johor and Siam and the sudden absence of Chinese merchant ships in the late 1710s all combined to limit the flow of trade goods from China to South Asia through Southeast Asian emporia, and this consequently encouraged South Asian-based traders to increase the intensity of the direct trade between the two regions.

The growing dominance of direct shipping after 1715

The decline in the abilities of Johor and Siam to link the economies of China and South Asia in the second decade of the eighteenth century coincided with an expansion of direct trade between the two regions. Three main national groups of long-distance merchants appear to have been instrumental in this expansion. The first two were British and French private merchants based in South Asia. They both benefited from the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, which made sea lanes safer and increased the availability of American silver to European traders. Macau’s merchant community also took advantage of these circumstances and used its position at the edge of the Qing empire to profit from the demand for Chinese goods in South Asian markets, as well as the demand for some South Asian goods, especially pepper, in China.

Of these merchant groups who became the connective tissue between the economies of China and South Asia, the most important from the late seventeenth century to the nineteenth were the British. In a recent article, Jessica Hanser has shown how the dominance of private British trade between China and South Asia reached its apogee in the latter half of the eighteenth century, after the British conquest of Bengal in 1757.Footnote 40 Long before the Battle of Plassey though, there were private British ships arriving in China whose crews were taking the first steps in forming the connections that Hanser describes. In fact, private British ships began arriving in Xiamen from Madras in larger numbers than the British East India Company’s own vessels almost immediately after the 1684 legalization of maritime trade in the Qing empire. Chinese captains and crews from that port reported the arrivals of British ships to the Chinese interpreters in Nagasaki in all but three years between 1684 and 1700 for a total of thirty-eight ships (see table 1), about four times as many as the number of documented company voyages to China in the same period.

Table 1. Yearly arrivals of British ships at Xiamen, 1684–1700

Sources: For the ‘All ships according to Chinese reports’ column, the references are from Hayashi Shunsai, Hayashi Hoko, and Ren’ichi Ura, eds., Kai Hentai. For the ‘Company ships’ column, the numbers are from Hosea Ballou Morse, The Chronicles of the East India Company Trading to China, 1635–1834 (Taipei: Ch’eng-Wen, 1966), vol. 1.

From 1700 to about 1720, Madras was still the main centre for private British trade to China. Sitting along the Coromandel coast, it had the best possible location for voyages from the subcontinent to Chinese ports. It also lay within a trading network that stretched across the Bay of Bengal, giving it access to some of the Southeast Asian products that were marketable in China, such as tin and ivory.Footnote 41 In 1717, Robert Hedges, the East India Company’s president in Bengal, wrote that ‘Madras has the China, Syam, Tonqueen, Pegu, Manilha, Java, and Sumatra trades most to themselves’, highlighting the city’s control of trade with both China and much of Southeast Asia.Footnote 42 Hedges’ statement also hints at the other major attraction that Madras held for businessmen interested in sending their ships to China, which was the ready supply of silver it offered. Besides the silver that the East India Company imported from Europe, Madras enjoyed regular shipments from Manila in the Spanish Philippines.Footnote 43 Because silver remained the most reliably acceptable import for the Chinese market, this gave Madras-based merchants an advantage in the South Asian–Chinese trade.

Between 1702 and 1716, Madras’s access to silver from the Philippines was especially important because the East India Company was suffering from a shortage in its European supply of bullion, almost certainly as a result of the War of the Spanish Succession.Footnote 44 Within a few years of the war’s conclusion, trade between Spain and Britain recovered, and the East India Company began pouring greater volumes of silver into its South Asian outposts.Footnote 45 This inflow of silver attracted even more private merchants interested in the China trade to Madras, and in 1723 the presidency even began encouraging private commerce with China through their port by offering resident merchants generous loans in silver bullion explicitly for that purpose.Footnote 46

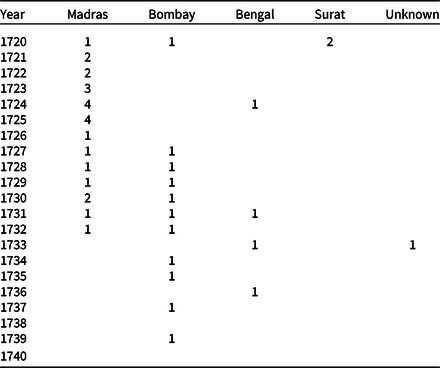

In the meantime, the company’s other establishments on the subcontinent were enjoying easier access to silver after the end of the war. Charles Boone, the president of Bombay from 1715 until 1722, consciously attempted to make his port imitate Madras’s success trading with China. His efforts revealed that Bombay actually had some advantages in the China trade.Footnote 47 The Bombay merchant fleet’s gradual penetration of the trading network of the western Indian Ocean during the first decades of the eighteenth century opened new markets for Chinese goods. In addition, the growing Guangdongese demand for raw cotton, a product that was widely cultivated in Gujarat, encouraged private merchants to begin regular voyages to Guangzhou directly from Bombay.Footnote 48 By the mid 1730s, these factors had helped Bombay surpass Madras as the main British port for private trade with China (see table 2).

Table 2. The origins of private British ships in Guangzhou, 1720–40

Sources: BL, IOR/G/12/8, IOR/G/12/21–48; Records of Fort St. George, 1720–1740; Morse, Chronicles of the East India Company, vol. 1., ‘Table of English Ships which Traded to China for the East India Companies, from 1635–1753’.

While Bombay gradually became the centre of British private trade to Guangzhou, Madras retained its connection to China thanks to the increasing activity of Macanese merchants in the Indian Ocean. The story of Macanese trade in the western Pacific and Indian oceans has been told in exquisite detail by George Bryan Souza. Here, it will suffice to demonstrate how this history fits into the development of Chinese–South Asian trade in the eighteenth century. Souza’s reconstruction of Macau’s commercial development shows that, across Southeast Asia, the Macanese traders were shouldered aside by Chinese merchants in the decades following the 1684 legalization of maritime trade in the Qing empire. East of the Strait of Melaka, the Macanese were relegated to secondary roles in the trade from China to Batavia and a number of other less important ports by the 1690s.Footnote 49 This situation of course prompted the Macanese to look for ways to maintain the commercial relevance of their port. The most successful strategy they employed was sending ships farther afield, beyond the extent of the newly arisen Chinese trading system. Macanese ships could sail beyond Melaka into the Indian Ocean, which was something no Qing-based vessels did, and this afforded them opportunities to trade without competing directly with Chinese merchants.

The Macanese sent ships semi-regularly to Goa and other Portuguese-controlled ports in the Indian Ocean, but these do not appear to have been their most commercially important destinations in the early eighteenth century. Instead, after about 1710 Madras became a common port of call for the Macanese in South Asia. From that year up until the end of our period, the Fort St George council diary records the arrival or departure of at least one ship for Macau almost every year until the end of our period (see Table 3). The council in Madras, writing in defence of their openness to foreign traders, told the company’s directors in 1739 that ‘As to the Maccao Men, they sold their China Cargoes & took in their returns here, This is a trade which has been carried on longer than any one of us can remember.’Footnote 50

Table 3. Ships sailing between Macau and South Asia, 1700–40

Sources: For the first two columns, Records of Fort St. George, 1700–1740; for the third column, Souza, Survival of Empire, 159.

Macanese merchants also began trading in several other South Asian ports around the same time, including Cochin and Tellicherry on the Malabar coast, and Galle on Ceylon. Of these, Cochin was likely the most important. Souza, using shipping lists kept by the Dutch factors in Cochin between 1720 and 1742, shows that in almost every year from 1723 to the end of the period there were between two and six Portuguese ships that arrived there.Footnote 51 These would have included both Macanese ships and those from other Portuguese ports, but the testimony of Jacobus Canter Visscher, a Dutch chaplain in Cochin, suggests that the Macanese were consistent visitors before Souza’s list begins. Visscher wrote that, while he was in Cochin between 1717 and 1723, ‘The Macao merchants have for some years kept up a brisk intercourse with Batavia, the Chinese junks having kept aloof. But not more than one or two ships visit Goa during the course of the year, and these part with most of their cargo, consisting principally of Chinese luxuries, as silks, tea, sweetmeats, and sugar, at Cochin and Ceylon.’Footnote 52

Visscher’s mention of the absence of Chinese ships at Batavia during the late 1710s hints at the reason why the trade between Macau and the Malabar coast became significant then. The Chinese merchants were of course not just ‘keeping aloof’. They were not sailing to Batavia during this period because of the Qing ban on voyages from China to most of Southeast Asia from 1717 until the end of the ban’s enforcement in 1723. The ban did not apply to the Macanese, which gave them the opportunity to step into the breach and dominate the Batavia–China trade route during those years. It also allowed them to temporarily become the major pepper and sandalwood suppliers for Guangdong, and perhaps the rest of China as well. Both of these trade goods were available on the Malabar coast, and trading for them in Cochin or Tellicherry also allowed the Macanese merchants to become important suppliers of Chinese goods to that part of India as the traditional flows through Siam and the Melaka Strait region were ebbing.Footnote 53

The last major group to take advantage of the decline in the westward trades of Johor and Ayutthaya were the French merchants based out of Pondicherry on the Coromandel coast. French ships began arriving in Guangzhou in 1698, and continued to visit that port intermittently through the course of the War of the Spanish Succession. Several of these sailed across the Pacific Ocean, delivering silver fresh from the mines of Peru.Footnote 54 No French ships that visited Guangzhou before the 1720s appear to have come from Pondicherry or any other South Asian port though; sea lanes through the Indian Ocean were too dangerous, and European silver supplies were too unreliable during the war. It was only after the declaration of peace in 1714 that the French were able to participate significantly in intra-Asian trade. In 1719 they founded a new East India company, the Compagnie des Indes, and joined the British and Macanese ships sailing directly between South Asia and China.Footnote 55

The Compagnie des Indes initially hoped that its own ships could monopolize trade between Pondicherry and Guangzhou, so it disallowed private traders from participating until 1728. One company ship made the voyage every year between 1723 and 1727 (see table 4). After 1727 the company discontinued its voyages from South Asia to China. A five-year hiatus followed in which no French ships sailed between the subcontinent and China, and then French private traders began sending their own vessels to Guangzhou, mostly from Pondicherry, but occasionally from Madras.Footnote 56 From 1727 on, private French merchant vessels joined British and Macanese ones as regular participants in the direct Sino-South Asian trade route.

Table 4. French Intra-Asian trading voyages to China, 1723–40

Source: Manning, Fortunes à faire, 236.

Along with the French, Macanese, and British, several other national groups with footholds in South Asia took advantage of the declining business environments in Ayutthaya and Johor and the effects of the short-lived Qing ban on domestic trade to Southeast Asia. None participated as consistently as the three main groups outlined above, but all helped to strengthen the direct trade route between the two major economic regions. On at least two occasions in the first half of the eighteenth century, there was a ship owned by Armenian merchants sent to China from South Asia. This ship, called the London in British records, was reported as arriving in Guangzhou in 1722 and again in 1723 by the British company’s agents.Footnote 57 In addition, ships from the Malabar coast sent by local rulers or merchants to trade pepper arrived on at least two occasions in Guangzhou during the 1720s.Footnote 58 Finally, the most prominent non-European participants in Sino-South Asian trade after the 1710s were the Surat-based family of the famous merchant Abdul Ghafur.Footnote 59 Ghafur and his successors sent ships to Guangzhou in 1715, 1716, 1719, 1722, 1724, 1727, 1731, 1738, and 1739, or about three a decade during our period.Footnote 60 In the remainder of the eighteenth century, Surat-based merchants continued to send ships to China on a semi-regular basis, likely benefiting from the Guangdongese demand for cotton, just as the Bombay merchants did.Footnote 61

Conclusions

The rising importance of the direct trade routes between China and South Asia in the early eighteenth century was matched by the growing importance of direct trade between China and Europe. The standardization of the Qing empire’s administration of trade in Guangzhou, as described by Paul Van Dyke, helped both types of commerce to grow after about 1715.Footnote 62 This expansion of direct trade reduced the roles played by Thai and Malay centres that had previously been instrumental in the relay of goods between the two larger economic regions. From the 1720s onwards, Johor’s and Ayutthaya’s contributions were primarily a supply of Southeast Asian products (tin, ivory, and sappanwood, among other things) to South Asian ports for re-export to China.

At the same time, it should be recognized that the reduction of Johor’s and Siam’s role in Sino-South Asian trade was not indicative of a decline in the overall importance of Southeast Asia within the early modern global economy. Although the Qing empire’s domestic trade fleets became marginal in the chain of supply leading from Chinese production centres to South Asian markets during the ban from 1716 to 1722, they quickly recovered their role as the dominant force in trade between every major Southeast Asian region and their home markets afterwards.Footnote 63

The narrative offered here therefore does not suggest that either Johor or Ayutthaya became closed ports or even became less important commercial hubs within Southeast Asia over the longer term. In Siam, there is every indication that the relative decline in participation by South Asian and European merchants (who never entirely ceased trading there anyway) was matched by a growth in trade between Siam and China, thanks to the machinations of the Chinese phraklong and the ethnic Chinese business communities along the Chao Phraya river. Similarly, after more than a decade of warfare in the Melaka Strait, Johor recovered under Bugis rule in the 1730s. Both Chinese and South Asian ships began to call again, drawn by the availability of pepper and tin from nearby production centres on the peninsula and Sumatra.Footnote 64

Instead, the larger argument here is that Indian Ocean commerce in the early eighteenth century was becoming enmeshed in a global trading system that did not respect distance or regional boundaries in the same way that previous commercial networks had. A collection of factors, including a greater demand for luxury goods in South Asia, an increased availability of American silver, and an opening of the Chinese market to foreign trade after 1684, encouraged the development of long-distance transcontinental trade routes at the expense of intermediary entrepôts. Johor and Ayutthaya would thus likely have gradually lost their roles as emporia between the two oceans as the century progressed even without the situations described in this article. But the approximate coincidence of the rapacious Siamese phraklong, the Johorese war, the Qing ban on voyages to Southeast Asia, and the increase in silver imports to the Indian Ocean after the War of the Spanish Succession effectively made the period from about 1715 to 1725 a turning point in the way that Asia’s maritime trade functioned.

Ryan Holroyd is a postdoctoral research associate in the Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan. His research is focused on the maritime expansion of Chinese commercial networks and the distribution of Chinese goods globally in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.