Introduction

Despite the enduring popular fascination with shoplifting—evidenced from the eighteenth century in literature, plays, and later films—it remains one of the least explored property crimes. There are few historical studies of shoplifting, and these mainly focus on either the history of the kleptomania diagnosis and defense or use evidence from contemporary newspaper reports.Footnote 1 Similarly, there have been relatively few contemporary academic studies.Footnote 2 Thorstein Sellin, writing in 1937, noted that, compared with other crimes, “There is a singular lack of shoplifting studies. Business houses have been found reluctant to give information.”Footnote 3 More than eighty years later, despite some notable contributions, this topic remains underexplored.Footnote 4

Popular interest in shoplifting largely stems from the distinctive characteristics of the typical shoplifter. Evidence has consistently shown that, in contrast to other crimes of material gain (with the exception of prostitution), shoplifters were overwhelmingly female. Moreover, typical shoplifters were “amateurs” (stealing for their own use, rather than to sell on the merchandise), and members of the middle and upper classes were considerably overrepresented.

This article examines interwar shoplifting from department stores and variety chain stores in the United States and Britain. The interwar era has been almost entirely neglected in historical accounts of shoplifting, which generally focus on the nineteenth century, or earlier periods, in contrast to the significant body of recent work on other aspects of interwar crime.Footnote 5 In addition to the standard sources, this study also uses archival data for U.S. and British retailers; reports from their trade associations; legal texts; articles in the retailing trade press; and a contemporary academic study of a U.S. professional shoplifter.

Patterns of shoplifting in the United States and United Kingdom had strong similarities—with stores facing a predominantly female, and often prosperous, army of amateur shoplifters, together with a much smaller corps of professional thieves. The methods used to deter shoplifters were also similar, as were typical legal penalties. However, America had one critical difference—the much higher incidence of a type of store criminal who specialized in deliberately getting caught, so that she/he could sue the store for false arrest and, often, false imprisonment, slander, and related charges. This reflected both the higher damages typically awarded by U.S. courts compared with Britain, together with a system—at least in some U.S. cities—whereby corrupt lawyers and judges connived in shoplifting acquittals that paved the way for lawsuits.

This study first examines the development of large store, open display retailing formats in the United States and Britain, focusing on department stores and variety chain stores, which—together with some clothing stores—were the prime targets for shoplifters. After outlining the incidence and characteristics of interwar shoplifting, it discusses why affluent women were disproportionately represented among the ranks of amateur shoplifters. This is followed by exploration of an underexamined related phenomenon—people deliberately getting arrested for shoplifting, so they could bring lawsuits against the store—and how this tempered efforts to control shoplifting and shifted policing activities from apprehension to deterrence.

Department Stores, Variety Chains, and the Expansion of Open Display Retailing

Shoplifting has traditionally been associated with store formats selling high-value, high-status items using open display techniques, such as bazaars, “bargain shops,” emporiums, and department stores.Footnote 6 A widely perceived trend of rising shoplifting from the 1870s to the 1930s was popularly associated with the rise of large, palatial shops using open display methods; particularly department stores—which became a significant force in both the United States and Britain during the third quarter of the nineteenth century.Footnote 7

Open display had always been an essential element of the U.S. department store business. However, by the 1890s, display technique was taken to a new level, using innovations in plate glass, mirrors, lighting, synthetic colors, and more coordinated sales floor and departmental layouts, to accentuate the appearance of their stores and merchandise.Footnote 8 Innovations in display continued into the interwar era, seeking to imbue merchandise with transformative messages and associations that would increase its value in the eyes of customers.Footnote 9 Meanwhile, department stores had grown substantially in size, making it more difficult for sales staff to recognize and monitor their customers, who increasingly expected to handle the merchandise without asking the shop assistant. Other innovations, such as cut-price sales, bargain counters, and bargain basements, were also associated with increased shoplifting, partly owing to the crowds they generatedFootnote 10

The new department stores developed an intensified commercial culture, largely based around luxury goods with strong “positional” characteristics—showing the person’s status by their instant recognition as “symbolic” status markers by their peer group.Footnote 11 Several studies have noted the social significance of goods typically stolen by middle-class female shoplifters—such as lace, silk handkerchiefs, and a variety of small, fashionable items—items instrumental in enhancing the person’s appearance, as recognized markers of social status. From a middle-class female perspective, these were not luxuries, but “necessities” for asserting or enhancing social status—not individually, but as part of a coordinated assemblage, that reflected on both the person and her family.Footnote 12 Mary Cameron’s 1964 study highlighted the dominance of highly visible status goods in shoplifting cases. Her analysis of women’s court data showed that women’s coats and suits; women’s dresses; other women’s clothing; dress accessories; and purses collectively featured in 97.3 percent of all cases; while data from a major local department store showed that these goods, plus jewelry, featured in 89.8 percent of cases (though in both samples some women had stolen multiple categories of goods).Footnote 13

While British and American department stores emerged at around the same time, open display techniques became significant in Britain during the 1910s (despite some moves in this direction during the Edwardian era).Footnote 14 Rapid diffusion was triggered by the examples of Gordon Selfridge, who opened a grand American-style department store in London’s fashionable West End in 1909, and F. W. Woolworth, who opened his first UK store in the same year.Footnote 15 Both were spectacularly successful, especially UK Woolworths, which became Britain’s largest retailer by the 1930s.Footnote 16 Woolworths’ methods and success inspired Marks & Spencer (hereafter M&S) to transform from a “penny bazaar” into an American-style variety chain during the second half of the 1920s. However, to avoid head-on competition with Woolworths, it adopted the price and merchandise polices of American “to a dollar” stores such as W. T. Grant and Kresge, with a maximum price point of five shillings (roughly equivalent to a dollar), which made it more attractive to shoplifters than Woolworths 3d and 6d items.Footnote 17

In 1935 there were some 4201 U.S. department stores, accounting for 10 percent of retail sales.Footnote 18 However, they were facing increasing competition from the chain stores, particularly “variety store” chains such as Woolworths, Kresge, and W.T. Grant, many of which (with the notable exception of Woolworths) had abandoned their 10¢ maximum price point and now sold goods priced up to $1, or in some cases $5, with some abandoning any price limit.Footnote 19 This allowed them to tap into the growing market for cheap women’s ready-to-wear clothing and other fashion goods, using display methods similar to those of department stores.Footnote 20 They were also looking, and behaving, more like low-end department stores; for example, using promotional techniques such as cut-price sales, supported by full-page newspaper ads, heavy with prices.Footnote 21

The Incidence of Interwar Shoplifting

The extent of shoplifting is impossible to measure with any precision, because most thefts went unreported. Even those that were detected were often not acted on by store detectives and other staff, because they were typically instructed not to take action unless they were certain theft had been committed. Even when shoplifters were apprehended, most first-time offenders were not formally arrested, and even fewer cases reached the courts. Considerations of cost, risk, and adverse publicity acted as strong disincentives to prosecution.Footnote 22 Moreover, most estimates of retailers’ losses are problematic, as they often include not only shoplifting, but employee theft (and, in some cases, the costs of store detectives).

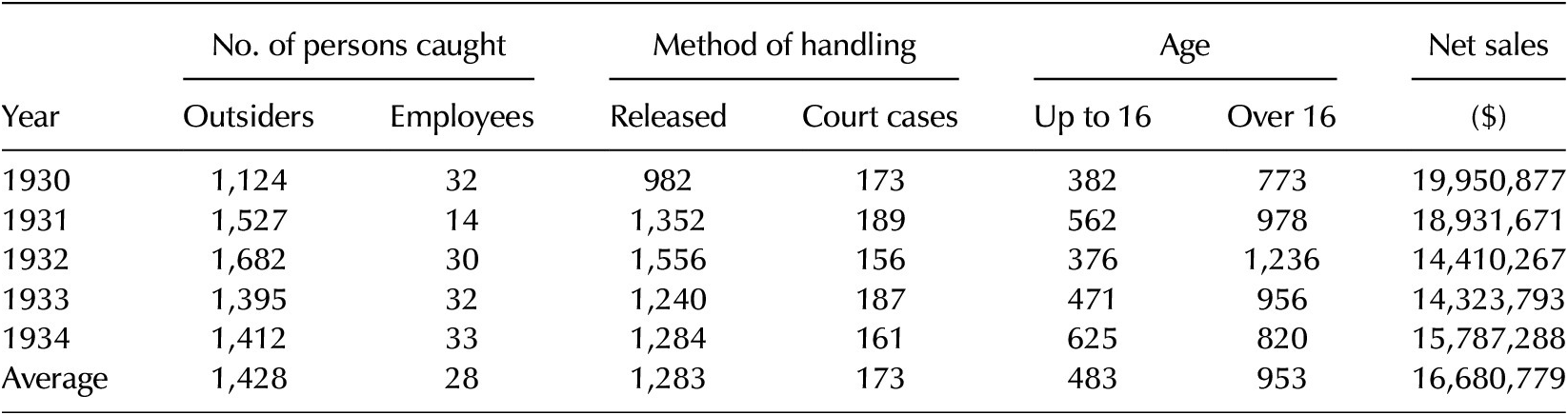

However, two U.S. analyses provide indicative figures. The first concerned a local department store chain, operating five stores in a large midwestern metropolitan area, mainly serving customers earning under $2000 per year.Footnote 23 As shown in Table 1, over 1930–1934, an average of 1428 “outsiders” (shoplifters) were caught, together with 28 dishonest employees. Employee theft was said to be harder to identify, but the figures suggest that shoplifting greatly outweighed staff pilfering, in contrast to modern estimates that around half of all store thefts are down to employees.Footnote 24 Some 34 percent of those apprehended were sixteen or under and—assuming no juveniles were prosecuted—18 percent of adults would face prosecution.

Table 1. Number of persons caught stealing from “Middle-Western Department Stores” (pseudonym), 1930–1934.

Source: Duncan, “Control of Stock Shortages,” 18, 281.

Table 2 provides data for three Philadelphia department stores. Known thefts averaged 5314 over 1928–1933, of which 1432 involved arrests. However, successful prosecutions amounted to only 16 percent of those apprehended, or 4.3 percent of known thefts. The table also casts doubt of the usefulness of police data, which show an average of only 4402 known shop thefts per year in Philadelphia (excluding those convicted), which is lower than thefts from just these three stores. Trade estimates put shoplifting losses for the major New York stores at around $1 million (claimed to be a conservative estimate), though this included employee theft and the costs of detectives.Footnote 25 Meanwhile, in March 1936, the National Retail Dry Goods Association (representing department stores) estimated national shoplifting, fraud, and allied thefts in department stores at $10 million.Footnote 26

Table 2. Shoplifting data for three Philadelphia stores, 1928–1933.

a Includes data for the entire city, excepting the numer of persons “prosecuted and convicted.”

Source: Thorstein Sellin, Research Memorandum on Crime in the Depression, Social Science Research Council Bulletin 27, 1937, p. 69.

New York Police Department (hereafter NYPD) data showed 1184 women and 239 men arrested for shoplifting in 1929 (2.1 per ten thousand population), compared with 943 women and 221 men in 1924—though this may also include store employees.Footnote 27 However, a detective at a major New York store reported in 1925 that eight hundred to one thousand arrests for shoplifting were made annually in his store, half of them on Saturdays, again suggesting that proportionately few went to court.Footnote 28 Figures for Greater London, for the broader category of “recorded cases,” show an average of 1.8 per ten thousand population from 1933 (the first available year) to 1938, with no clear trend. The figures suggest that London had a lower incidence of shoplifting than New York, though of the same broad order of magnitude.Footnote 29 However, shoplifting in New York and London is likely to have been more widespread than in provincial cities, as professional thieves could avoid recognition by moving from store to store.Footnote 30

There is no strong evidence of a spike in shoplifting during the Depression. New York’s “Stores Mutual Protective Association,” encompassing sixteen of the largest New York stores, plus some smaller firms, noted that before 1930 it had added an average of 3500 new shoplifters to its files each year, while the Depression increased this to around 4000.Footnote 31 However, New York attracted professional shoplifters from all parts of the United States, owing to its large number of department stores, enabling thieves to shoplift for weeks without becoming known to store detectives. Tables 1 and 2 show only a mild increase in shoplifting across the Depression. One career shoplifter reported that the Depression adversely impacted professional shoplifters, as the resale value of stolen merchandise fell sharply, while the costs of bribing their way out of imprisonment when arrested remained as high as ever.Footnote 32 Meanwhile, thefts of food by destitute people would be very unlikely to leave any record, as a typical grocer could not afford to spend half a day testifying in court.

Boosters and Snitches

The most important distinction within the shoplifting community, recognized by stores, courts, and shoplifters themselves, was between the professional shoplifter, known colloquially in the United States as “the booster,” and the amateur pilferer or “snitch.”Footnote 33 A June 1920 New York Times article reported that only 10 percent of shoplifters in New York stores were “hardened thieves,” and 90 percent were women.Footnote 34 “Professional shoplifters” (typically defined as anyone who stole to sell on) included a higher proportion of men than amateur shoplifters, though women appear to have also dominated this category.

Some of the most expert shoplifters—admired by both the criminal fraternity and the store detectives—were women. For example, London had an elite group of professional shoplifters, known as “hoisters.” The most famous were the “Forty Thieves” (also called the “Forty Elephants,” on account of their rotund appearance once they had hidden merchandise in various concealed pockets in their clothing), who were well connected with London’s underworld and targeted high-end shops and expensive items such as furs and jewelry. The gang was both staffed and led by women, who dressed like society ladies to blend in with the customers of exclusive stores and made carefully planned raids on extremely expensive items, using distraction and similar techniques.Footnote 35 However, professional shoplifters represented a broad spectrum, including criminals who switched to shoplifting only during sales, when the looting was easy, and drug addicts and alcoholics seeking means to finance their habits. Professional shoplifters sometimes worked in teams, using accomplices to take stolen goods from the store, in case they were stopped and searched. One American store manager stated that, in nine out of ten cases of professional shoplifting of small items, the person who carried them from the store was not the one who stole them.Footnote 36

According to research by Ralph L. Woods, professionals accounted for only around 10 percent of U.S. shoplifters in the late 1930s.Footnote 37 Mary Cameron’s study gives a similar estimate (though the average value of thefts was typically much higher).Footnote 38 Many “amateur” shoplifters were habitual ones, with a degree of skill, sometimes being caught with shoplifting “equipment” such as suitable bags and concealed pockets to hide the goods, scissors to remove price tags, and “shopping lists” of goods to steal.Footnote 39 However, they were sometimes naïve in their methods—for example, amateurs often stole multiple items during the same visit, while professionals stole only single items—as being caught with multiple stolen items was harder to explain away as forgetfulness or a wish to compare the item with others in the store.Footnote 40

All sources concur that affluent women were overrepresented in the U.S. shoplifter population.Footnote 41 The gender bias may partly reflect the dominance of women in the stores’ customer base, but research for this study has not found any examples of shoplifting by male middle-class amateurs in this era. A similar overrepresentation of middle/upper-class shoplifters was evident in Britain. For example, in October 1933, Lily Smith, arrested for stealing a 15s. handbag, was shown in court to be a rich widow, with £40,000 invested in Argentina, a house in Cardiff, and a boarding house in London. After being told she had over £60 (around ten weeks’ salary for a clerk or teacher) in her possession when arrested, she was fined £5.Footnote 42 However, other British judges were less lenient on middle-class shoplifters. In 1920, Emie Kennedy (the wife of an ex-officer holding a responsible position in the Admiralty), together with a “lady accomplice,” pleaded guilty to nine months of shoplifting. The pair had been apprehended at London’s elite Harvey Nichols store, and the subsequent police investigation found large quantities of apparel, which the defendants admitted stealing from West End stores. The magistrate sentenced both to six month’s imprisonment.Footnote 43

Shoplifting was usually highest in the run-up to Christmas and at Easter, when crowds thronged the stores. The NYPD publicized the dangers of Christmas shoplifting during the 1920s with mass trials, reported at length in the newspapers. For example, on January 12, 1921, some 176 alleged shoplifters appeared in the New York Court of Special Sessions, 62 of whom were arrested in a single department store. It required two courtrooms to accommodate them, and about an acre of spacious vestibule to hold their children, relatives, and friends, plus witnesses. Almost all were women, aged sixteen to eighty-two, and very few were reported to give an outward appearance of poverty. Some were said to be magnificently dressed. Ninety-eight pleaded guilty, though Chief Justice Kernochan said that he thought not more than three or four were professional criminals. Yet of those who pleaded guilty, about twenty were said to have robbed two or three stores before being apprehended. Most were fined $50 and a total of $2275 was collected on the day, every fine being paid. Twenty who had shoplifted from more than one store, but had no criminal record, were sent for imprisonment in “The Tombs” for a day (a common deterrent strategy in New York).Footnote 44

Sentencing in Britain and the United States was broadly similar, with a trend away from prison sentences for first offenders after World War I, following gradually more lenient sentencing over the nineteenth century.Footnote 45 Repeat offenders could face short prison terms, with longer sentences for persistent shoplifters. However, from 1926, habitual New York shoplifters faced life imprisonment under “Baumes laws,” which made this mandatory for a fourth offense (a precursor of the 1980s “three strikes and you’re out” legislation). Ruth St. Clair became the first person to receive a life sentence under this law, in December 1929, for a fourth shoplifting conviction. This sparked a major controversy, and in 1937, after serving seven years, she received a conditional pardon from the state governor, only to be arrested again for shoplifting in July 1939.Footnote 46

Employee theft was also said to be substantial, but has left fewer records, as most retailers regarded dismissal and recovery of the goods an adequate sanction. The New York State Department of Labor found that this was particularly problematic in variety stores, owing to low wages and high labor turnover.Footnote 47 As a retail executive told Chain Store Age in 1926, “We never try a case in court. Most of our offenders are young fellows whose lives we do not want to spoil. And we could not get any more than a conviction, suspended sentence on parole or the like. We doubt if a trial by jury except in an aggravated case would do us any good. Juries are usually prejudiced against corporations.”Footnote 48

A complicating factor was a tradition, in older independent stores, of clerks taking stock for personal consumption—though variety and department stores did not tolerate this practice.Footnote 49 However, some clerks undertook much larger thefts, sometimes in conjunction with customer accomplices.Footnote 50 Staff falling under suspicion were often dismissed, even on weak evidence. For example, H.L. Green, a variety chain with 130 stores, stated, “It is commonly-accepted good policy to dismiss a sales clerk whose actions are suspicious, rather than attempt to catch her with the goods.”Footnote 51

Why Did Affluent Women Shoplift?

Three popular explanations have been proposed for the disproportionate number of apparently prosperous women shoplifters: illness; “need,” in terms of having insufficient control over money to keep up appearances; and being “entrapped” by irresistible displays of sumptuous goods.

Kleptomania had been a popular early explanation. The “kleptomania defense” reached its zenith in the late nineteenth century, vigorously promoted by a medical profession that could free a prosperous woman from shoplifting charges by medical diagnosis. By the interwar era, the definition of kleptomania had strayed beyond the specific medical condition that nineteenth-century psychiatrists claimed to have identified. It was now typically expressed in terms of impulsiveness, stress, or mental illness, only the last of which could meet the original clinical definition. Some female defendants even asserted they had stolen impulsively, for the excitement—extending the definition to a form of “extreme shopping,” which they felt was justified by their motivation. Even this variant of kleptomania received some support from a medical profession that was indirectly profiting from shoplifting, using arguments that the dazzle and luxury of palatial department stores aroused uncontrollable desires for possession.Footnote 52 However, this was a particularly middle-class defense, as only affluent women could afford expert medical testimony. Moreover, as Elaine Abelson noted, while it offered a way of reconciling shoplifting with middle-class respectability, it “profoundly undermined the self-respect of women as individuals and as a group,” transforming the female shoplifter into a childlike figure who could not control her own impulses.Footnote 53

By the interwar era, kleptomania was wearing thin with most judges, who increasingly rejected the distinction between the middle-class “kleptomaniac” and the working-class “thief.” Kerry Segrave argues that the kleptomania defense had largely disappeared by 1920 in the United States.Footnote 54 Newspaper reports suggest that it was still used occasionally in British courts, but that judges often gave it short shrift. For example, in July 1934, Phyllis Cochrane pleaded guilty to stealing a frock and a dress from two leading London stores. Sir Henry Curtis Bennett, KC, defending, noted that she had recently lost her husband, a man of “some position,” and that her mental state had become unstable. However, the magistrate sentenced her to three months’ imprisonment (concurrently) on each charge, stating that, if she had been a poor woman, she would not have been able to brief eminent counsel and call evidence as to her state of mind. He must regard her as a person responsible for her actions.Footnote 55

Similarly, in June 1920, Elizabeth Barker, aged forty-four, stood accused at North London Police Court of shoplifting a man’s suit of clothes. Her barrister claimed that Barker “had arrived at that point of life when women did curious things” (a reference to kleptomania being associated with the onset of the menopause). However, a detective-sergeant testified that she had been previously convicted of shoplifting and that he believed her to be an expert thief. Despite the court being informed that her husband was “a most respectable man,” she was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment with hard labor.Footnote 56

Explanations framed around “need” appear to have been honestly advanced and probably contained some truth in a proportion of cases—though the definition of “need” was broad, based on maintaining a lifestyle expected by her peer group. Late nineteenth-century U.S. sources reviewed by Abelson noted that apparently affluent women did not have control over their own money and, allotted insufficient cash by their husbands or fathers, turned to shoplifting to “keep up” socially.Footnote 57 Similar explanations were put forward in the interwar era. A 1930 New York Times article suggested, “Perhaps a woman, having received an allowance from her husband, has gambled it away at bridge and must yet be able to give some other account of how she spent the money. She goes to a department store and steals lingerie, hosiery, cheap jewelry, or dresses.”Footnote 58

Similar explanations were advanced in Britain. A commissionaire at a large London department store reported hearing “any number of cases of ladies who, as far as appearances go, are well to do, but in reality they are kept very short of ready money, and to those ladies the possibility of being able to get a roll of ribbon or a pair of gloves for nothing is a temptation.”Footnote 59 However, this would not explain why prosperous women would have greater “need” to steal than their lower-middle-class and working-class counterparts, for whom making ends meet was a much harder task.

Arguments drawing on consumer culture theory explain shoplifting in terms of the intense commercial culture of department stores, which “entrapped” customers with irresistible displays, calculated to generate the very desire that turned otherwise respectable women into thieves. Similar explanations were common from the late nineteenth century.Footnote 60 Some British judges became unlikely advocates of this explanation. For example, in March 1937, several shoplifters at the M&S Brixton (south London) store, were brought before magistrate Claude Mullins—who had famously denounced M&S’s open display format (Figure 1).Footnote 61 J. D. Cassells, representing M&S, said that each week about fifteen to twenty thousand people visited their Brixton store, which was protected by shop assistants, managerial staff, seven floorwalkers, and one or two detectives. Some women came with the deliberate intention of stealing, and it was difficult for the firm to protect itself.

Figure 1. Open display at the M&S Birmingham store, January 1933.

Source: Reproduced by kind permission of the M&S Company Archive (image P1/1/29/11).

Mullins replied: “This modern method of display is … more than average human nature can resist. Most of these people are not really criminals, and I feel that the people who place temptation in their way are, to some extent, responsible.”Footnote 62 Similarly, a Sheffield magistrate suggested in 1935 that firms such as M&S should have a system of grids, as in the Post Office, to deter shoplifters. He argued that M&S made no “effort whatever to protect their goods … They collar the thief and send him here for the Bench to waste time on their behalf.”Footnote 63

In 1933, London magistrate Ivan Snell visited several stores where shoplifting was rife. His predecessor had unsuccessfully tried to reduce shoplifting by imposing prison sentences (except in exceptional circumstances). Snell’s visits convinced him that the stores were at fault. In court, having imposed fines from £2 to £5 on six women shoplifters, he announced that rather than being dressed as ordinary customers, detectives should wear distinctive uniforms to show that a watch was being kept. In apparently unpoliced stores, “decent law-abiding women, wives and mothers, are being tempted … by their methods of display.”Footnote 64

Snell also suggested that there should be notices to the effect that detectives were watching and shoplifters would be prosecuted.Footnote 65 However, a Times article argued that such methods would put off customers: “There is a natural dislike of going into a place where it seems that the virtuous and the unvirtuous are regarded alike as potential criminals. Nor when the art of displaying goods has reached its present pitch is it certain that proposals for diminishing its ingenuity are likely to be acceptable; less liberal display might … be regarded by many shopkeepers as a retrograde step.”Footnote 66 Deterrence was thus not allowed to get in the way of creating the right customer environment and thereby maximizing sales.

American judicial condemnations of open display were rare, probably due to such methods having been used since the 1870s, while in Britain they only really took off in the 1910s. However, criticism was not entirely absent. In November 1920, New York justice John Freschi noted, “My experience on the bench has shown that seven out of every ten shoplifters are tempted by the display of articles, apparently unprotected. Like Snell, he recommended large warning signs and uniformed detectives.Footnote 67 His two fellow judges concurred, arguing that store proprietors should seek to prevent shoplifting rather than confine their efforts to arrest and prosecution.

However, explanations based on stores beguiling and entrapping female customers into theft have similarities with the interwar version of the kleptomania defense—fundamentally casting women as impulsive, childlike figures, who were distinguished from men by their inability to resist the lure of attractive merchandise.Footnote 68 A more convincing explanation was proposed by Cameron, whose book, based on her doctoral thesis, was one of the first substantial sociological investigations of shoplifting. She argued that amateur shoplifter practices such as bringing shoplifting equipment, having plans for evading detection, and destroying evidence such as price tags, did not suggest a sudden loss of control.Footnote 69 Amateur shoplifters, she argued, suffered from what we would now call cognitive dissonance, whereby the perpetrators—usually having a self-image of a law-abiding citizen—did not regard their thefts as crimes, until they faced arrest. However, the shame associated with arrest and potential prosecution led to a radical re-assessment of their behavior, especially as—unlike professional criminals—their actions would be unlikely to find support from their peer group. This, Cameron argued, accounted for the low re-offending rate among amateur shoplifters.Footnote 70

Cameron concluded that amateur shoplifting was essentially another form of “white-collar crime,” a phenomenon typically ascribed to men, for whom it encompassed behaviors such as embezzling, overcharging clients, padding expenses, and stealing office supplies—activities similarly not seen as “crimes” by the perpetrators. This was corroborated by the types of merchandise amateur shoplifters stole—typically items that could be worn as status symbols.Footnote 71 It also explains the frequent statements of apprehended shoplifters that they stole because everyone else was doing so,Footnote 72 an argument often used by male white-collar criminals, who regarded packing expenses claims or taking office supplies as a widespread and accepted “perk.” The “entitlement” justification of thefts by regular store customers was captured by the slang term “five-finger discount,” that had come into popular parlance by the 1960s.Footnote 73

While male white-collar criminals sought higher income, and the social status flowing from this, by stealing primarily money to gain advantage in the race of “getting on,” women did so more directly, by taking the status items they desired. Thus, rather than rejecting middle-class norms, they were trying to gain a better position in the middle-class hierarchy by pilfering items that were, in Bourdieu’s terminology, “symbolic” to their peer group.Footnote 74 This also resonates with the “need” explanation, outlined earlier, which focuses not on absolute needs, but status-driven needs. Shoplifting can thus be seen as the extreme end of a spectrum of opportunistic shopping practices, such as buying a dress to wear once and then returning it.Footnote 75

However, another significant element of middle-class amateur shoplifting was omitted in Cameron’s analysis—the thrill reported by its practitioners, which appears to have represented a significant subsidiary motive. As Wood noted in 1939, for many affluent women, shoplifting represented, “a lark, an adventure, and only secondarily a crime,” again demonstrating cognitive dissonance between the person’s actions and their implications.Footnote 76 It thus had a strong “ludic” element (enjoyment from playing the game)—akin to gambling, except that the stake was the player’s social reputation and, possibly, liberty.

Turning the Tables: Shoplifters Suing Stores

In both Britain and America, nineteenth-century shoplifting cases involving rich and powerful women graphically illustrated the perils that stores faced when pressing prosecutions. This reflected not only the power-distance between such women and the typically lower-middle-class shopkeepers who made the allegations, but a more general belief that a “lady” of high position and feminine respectability was incapable of such crimes.Footnote 77 One particularly influential case involved Jane Tyrwhitt, a wealthy married woman with connections to the aristocracy, accused of stealing an inexpensive microscope from London’s Soho Bazaar in November 1844. Despite strong evidence against her and her only defense being that she would have no reason to commit such a crime, she was nevertheless acquitted.Footnote 78 Moreover, the retailer endured ferocious public condemnation, including a letter-writing campaign in The Times. In addition to arguments that a woman of her station would be incapable of such a crime, some correspondents inferred that it must have been planted on her by the shopkeeper.Footnote 79

Despite an allegedly more egalitarian culture in the United States, elite Victorian Americans reacted in the same way when one of their own was caught shoplifting, as seen in December 1870, when five women, including the wealthy philanthropist Mary Phelps, were arrested for shoplifting at Macy’s. All charges were dismissed at the Special Sessions Police Court, while Macy’s, its management, and its employees were denounced in newspaper articles and letters—again on the “evidence” that the women’s social position and good character made such behavior unthinkable. Thereafter, for many years, Macy’s and other prominent New York stores were generally unwilling to prosecute “lady” shoplifters.Footnote 80

Stores also faced direct financial costs. In 1878, a Mrs. Davis was awarded $150 in damages for being wrongly accused of stealing a purse from a New York store, leading to her being forcibly detained and searched.Footnote 81 Over the following decades, the damages requested and received for wrongful arrest (often in conjunction with false imprisonment and slander) in the United States multiplied, acting as a significant deterrent to apprehension, unless there was an airtight case. An extreme example involved Mrs. Theresa Kirches, who in March 1929 sued F. & W. Grant Company in New York’s Queens Supreme Court for $100,000 for false arrest and the resulting humiliation and mental anguish. The incident involved the alleged theft of two nightgowns, charges that she was later acquitted of. Unfortunately, the New York Times, which carried the story of the first day of the trial, did not report the outcome.Footnote 82

By the 1920s, department stores had become wary of criminals who sought to be falsely accused so that they could bring a case against a store.Footnote 83 Variety stores were particularly attractive targets, given the deep pockets of the major variety chains and strong antagonism from local business communities—who often dominated juries. It was widely perceived that the expanding chains were driving independent retailers out of business. Several states and municipalities introduced taxes on chain stores, together with restrictions on their selling and pricing policies.Footnote 84 Opposition intensified during the Depression, as the variety chains, facing market saturation for their traditional five-and-dime merchandise, moved into higher-value goods, in direct competition with department stores that were often regarded as local institutions.

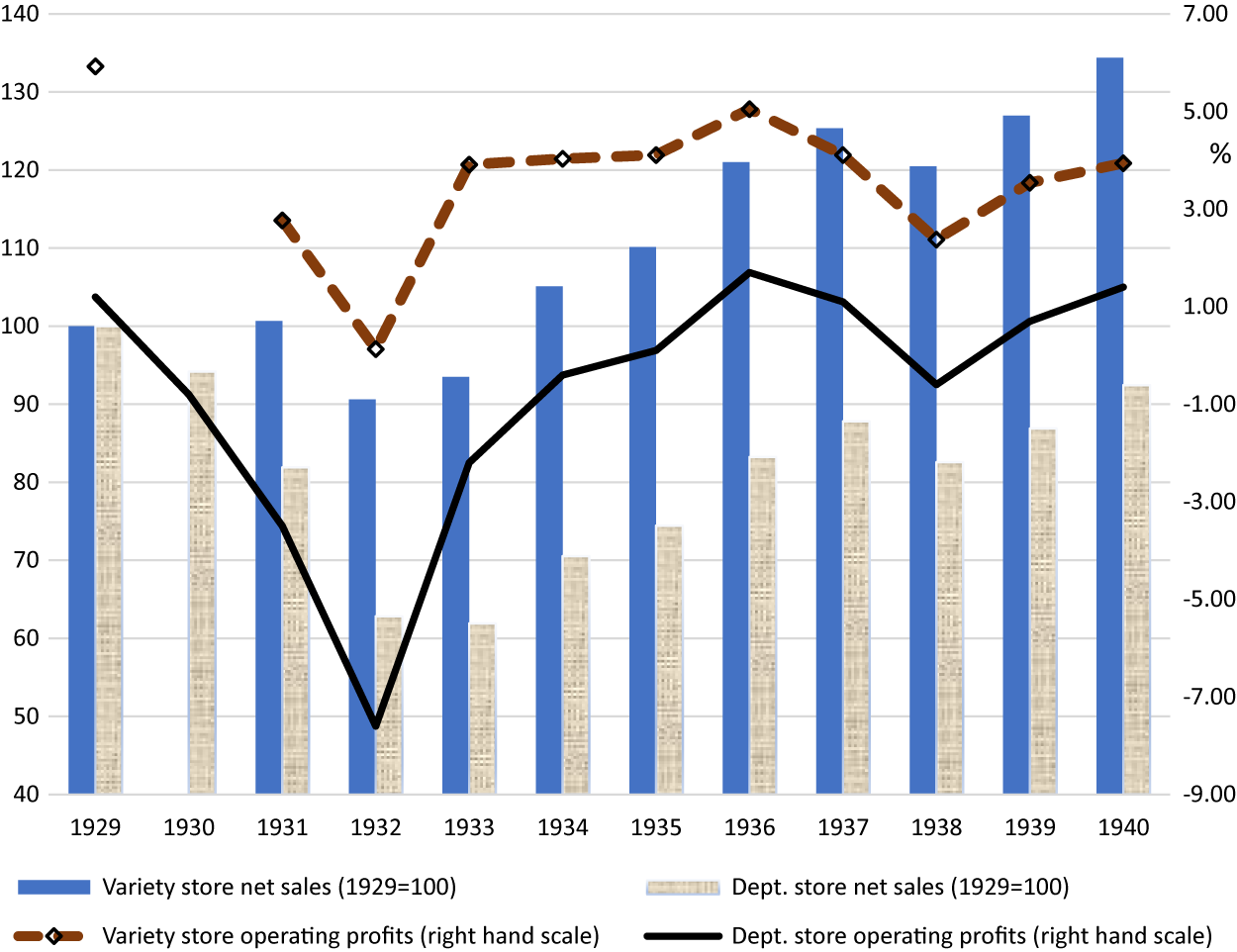

Department stores were already struggling to generate an acceptable profit during the 1920s.Footnote 85 However, the Depression saw department store operating profits collapse to a low of −7.6 percent of sales revenue in 1932, while the sector reported losses in six of the eleven years from 1930 to 1940, in contrast to healthy profits for the variety stores. Meanwhile, department store and variety store sales, set at 1929 = 100 (see Figure 2), diverged substantially during the 1930s, with the variety stores’ sales index climbing to 110.1 by 1935, while the department store index fell to 74.4.Footnote 86

Figure 2. Data on net sales (1929 = 100) and operating profits (percentage of net sales) for identical samples of fifteen variety store chains and seventy-six department stores, 1929–1940.

Sources: Variety stores: Teele, “Expenses and Profits of Limited Price Variety Chains in 1938,” 5, 8; Burnham, “Expenses and Profits of Limited Price Variety Chains in 1942,” 32–33. Department stores: McNair and May, “American Department Store,” 26–27.

Variety store chains perceived themselves to be under siege from criminals who could get considerable damages, sometimes for alleged thefts involving goods costing only a few cents. These included not only criminals, but people genuinely falsely arrested, as the large payouts for such cases were prominently reported in the newspapers. Meanwhile the criminal community was well informed of new rackets such as this, as there were strong information flows between criminal gangs, even rival ones.Footnote 87 As a Kresge 1935 memorandum to all their stores noted:

We have just lost a suit for assault and slander allegedly committed by a floorman resulting in a verdict of $2,500 plus expenses of over $600. Another case is pending because an assistant manager falsely accused [a customer] and placed his hands upon the wrong party. Our attention has been called to a verdict against one of our competitors for damages amounting to $5,700 because of the humiliation and suffering resulting in a false arrest. The theft of a ten-cent item was the issue.Footnote 88

The letter urged store managers to use utmost discretion; to avoid accusing anyone of stealing under any circumstances; to not place hands on or search customers; and to not ask anyone to sign confessions or releases. Suspects should instead be asked courteously and without accusation if they wished to have the merchandise wrapped, noting that all merchandise must be wrapped before leaving the store.Footnote 89 Similarly, the Butler Brothers chain advised its staff that in apprehending shoplifters, “you have thrown yourself open to liability for damages in event you lose your case. Conscientious and sincere merchants have more than once sustained heavy losses in such damage suits.”Footnote 90

A 1953 review of cases stretching back to the 1930s noted that shoplifting false arrest judgments for several thousand dollars were fairly common, while many cases were settled out of court for substantial amounts.Footnote 91 It also noted the prevalence of bogus false arrest frauds.Footnote 92 Stores that detained alleged shoplifters could face charges of assault and battery, slander, or insulting language.Footnote 93 However, the main charge was typically unlawful arrest, for which damages could include loss of time, physical discomfort and injury, mental anguish from humiliation, and injury to reputation.Footnote 94

Even obtaining the services of a policeman was no safeguard against lawsuits. One U.S. variety store, plagued by shoplifters who operated on Saturday afternoons and evenings when the store was busy, asked the chief of police to assign a uniformed officer at those times—paying $10 a day for his services. Shortly afterward, the policeman detected an alleged shoplifter, who ran from the door on seeing him. The suspect was eventually apprehended after the policeman had fired his gun. However, the case was dismissed on account of insufficient evidence, and he sued the store for $50,000, being awarded $5700 by the jury.Footnote 95 Local attitudes toward chains moving into town were said to have unduly impacted the size of damages. As the article continued, “We ask our managers to remember that whenever a chain is involved in a court action by a resident of a small city it runs the danger of facing an unfriendly jury.”Footnote 96 Anti-chain prejudice was also noted in the academic law literature.Footnote 97

While some suits involved genuine false arrest, many were perpetrated by skilled thieves. In 1934, a store manager reported, “Several forms of racket based on possession of merchandise, such as the bringing of merchandise into the store in an effort to bait the manager into making a false accusation.”Footnote 98 Even the most low-key approach to a suspected shoplifter could be presented very differently in court, where “a quiet inquiry by the merchant as to the contents of the plaintiff’s shopping bag may become a shouted accusation of theft overheard by everyone in the store, and a tap on the shoulder may become a violent seizure resulting in grave mental suffering.”Footnote 99 Similarly, a request to have the goods wrapped should be carefully worded to ensure there was no accusation, direct or implied. The traditional practice of taking a suspect into a closed room for an interview was also unsafe, as it might be construed as an “arrest,” especially by a jury that “is disposed to favor the culprit because of antagonism to the chains.”Footnote 100

Some scams involved accomplices, such as the “information racket.” One recited case involved a woman who told an assistant manager a particular man had picked up a pocketbook and hidden it under his coat. The assistant manager, seeing a suspicious bulge on the man’s person, trailed him out of the store. On the strength of the woman’s charge, he stopped the man and was allegedly tricked into making an accusation. There was no pocketbook on the suspect, and when the assistant looked for the informant, she had disappeared, leading to a lawsuit “that was expensive for us.”Footnote 101

A simpler but effective stratagem was to steal an item and then pass it to an accomplice. One such account involved a gang of shoplifters, with a blind man making the initial theft. This led to a lawsuit for heavy damages, given that the manager had made a direct accusation and searched the suspect. Investigation disclosed that managers of other stores had noticed the blind man and his party and felt certain he was a thief. Yet the company realized that it was an extremely dangerous case, with insufficient proof, and therefore settled out of court for a sum “that cut heavily into the store’s net profits for December.”Footnote 102

The Fix

In addition to local anti-chain bias, legal system corruption was also a factor in damages suits, at least in certain localities. For example, Mary Felder, aged eighteen, was arrested leaving S. Klein’s store in New York wearing a dress she had not paid for (her old dress being concealed in a cardboard box she carried). She admitted taking the dress on arrest and at the police station. Felder was arraigned before New York magistrate Jesse Silbermann. Her attorney, Mark Alter, who specialized in Women’s Court litigation, was a close friend of Silbermann. Silbermann discharged the case, after which a perplexed Samuel Klein sought an interview with Silbermann, then his superiors, regarding the decision. The case was reheard, under Silbermann, who again dismissed the charges.Footnote 103

Felder then sued Klein’s for false arrest and imprisonment, though the suit was later withdrawn when it was discovered that her mother had been convicted twice for shoplifting. This case featured in the famous “Seabury investigations” into corruption in the New York judicial system and police force, with Seabury charging that Mary Felder had been acquitted in order to create the damages suit, in which Alter had a financial interest.Footnote 104 Silbermann was also investigated regarding the acquittal of Minnie Hansaty, another alleged shoplifter at Klein’s, in what the firm considered an airtight case, contributing to his removal from the bench.Footnote 105 A hint regarding similar practices may underlie Woods’s 1939 comment that “Macy’s discovered that too often first offenders who were prosecuted were ‘sprung’ by lenient judges and that lawsuits for false arrests sometimes followed.”Footnote 106

False arrest claims and the acquittals that preceded them were facilitated by a preexisting form of legal system corruption: “the fix.” Career criminal Chic Conwell claimed, in the classic criminology text The Professional Thief, that “fixers” could arrange for professional shoplifters to escape conviction (or get away with a fine) in virtually all parts of the United States. This involved bribing the arresting officer or, where this was not possible, the prosecutor or (more rarely) the judge. This service was only available to professional thieves, while the much larger number of amateur shoplifting cases provided “cover” for fixed cases by maintaining satisfactory conviction rates for police and prosecutors.Footnote 107 He also claimed that store detectives could be bribed, their corruption again being camouflaged by high conviction rates for amateur shoplifters.Footnote 108 Detectives provided by the major agencies were also said to be open to bribery, except the Pinkerton’s, who worked for “honour more than money.”Footnote 109 The prevalence of the fix was also discussed in a 1953 Yale Law Review article on shoplifting and the law of arrest.Footnote 110 Cameron reported that the fix was still rife in Chicago in the 1960s, with specialist fixer attorneys being paid regular retainers for this service.Footnote 111

In Britain, by contrast, while many judges were not above bias and favoritism, there is no evidence of the type of wholesale financial corruption for low-level career criminals that occurred in some U.S. cities.Footnote 112 Moreover, Britain had a tradition of paying more modest damages, which were sufficiently high to deter store malpractice, but did not pose so large a threat that managers felt intimidated from apprehending in clear cases of theft. In May 1935, Gwendoline Humfrey was awarded £800 ($3920) damages from Woolworths UK for false imprisonment, slander, and assault following an unsuccessful shoplifting prosecution, which, she claimed, resulted in her losing the chance of a position as a governess. However, there were exceptional circumstances—as Woolworths had persisted in their charge, taking advantage of court privilege, therefore “damages must be heavy to prove to the world her innocence.”Footnote 113 All other successful cases reviewed by the author involved smaller damages, from £20 to £300 ($98 to $1470).Footnote 114 Thus both the incentives for and the capability to engineer bogus false arrest claims were substantially weaker in Britain than in the United States.

However, Britain was not completely free of bogus arrest suits. On October 19, 1936, Rebecca (a.k.a. Rene) Stone, a taxicab proprietor, visited the West End department store Swan & Edgar. Stone moved between departments for about an hour without making any purchase. A female store detective became suspicious and observed her picking up a pink garment before leaving the store. The detective apprehended her and asked her to come back to the store, but she refused, stating that the goods she carried had been given to her by a friend, whose name she declined to divulge. The police were called, and she was arrested and taken to Vine Street police station. Several items were found on her person, including two slips (one pink) but the store staff were unable to identify any of them as store property. She was released, with an apology.

It emerged that Stone had previously obtained a settlement of £500 from the catering chain J. Lyons & Company on account of illness after her mouth was cut with a piece of tin found in their baked beans. Meanwhile Swan & Evans received an anonymous letter, stating that Stone was planning to make false allegations against the store and disclosing the Lyons settlement—though this arrived some nine days after the arrest. Stone sued for assault and false imprisonment; despite the police strongly suspecting that she had “arranged her own arrest,” Swan & Edgar settled the case out of court for £250, plus costs, partly to avoid bad publicity.Footnote 115

Deterrence

Both the risk of unlawful arrest suits and the financial and staff time costs of prosecutions incentivized increased use of deterrence rather than legal remedies, where possible. New York’s S. Klein’s store—the world’s largest women’s clothing store and a New York institution famous for its low prices—was an extreme example, using large, prominently displayed signs with slogans such as “The Penalty for Dishonesty Is Jail” in several languages.Footnote 116 However, as with many of Klein’s retail practices, it was an exception, with most stores using more subtle methods that would deter shoplifters while not upsetting other customers.

The key personnel in the war against the shoplifter, imposter (who charged goods to someone else’s account), and dishonest employee were the plainclothes store detectives. Private detective agencies emerged in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century and experienced rapid growth in the postbellum era, receiving much business from the new corporations. Much of their work involved monitoring workers’ honesty and union activities through undercover surveillance. Detectives were soon hired by the big stores, either through agencies or, more commonly, as direct employees.Footnote 117 Employee detectives were sometimes drawn from the ranks of police officers, but more typically from the sales staff. Macy’s hired its first female store detective in 1870, but men comprised the bulk of store detectives until after 1945.Footnote 118 London also had female store detectives before1914, described in a 1911 article as being “so skillful in their disguises that even the most notorious female shop thieves often fail to recognize the detective, even when she is standing close behind them in a crowd.”Footnote 119

Squads of store detectives in New York were reported in 1930 to vary from half a dozen in the smaller stores to 100 in one very large department store, thus representing a significant business cost.Footnote 120 This was partly a seasonal trade, with extra detectives recruited around Thanksgiving.Footnote 121 Detectives relied heavily on salespeople, who they viewed as shrewd judges of their customers, to point out suspicious behavior. Some stores incentivized sales staff via monetary rewards for items retrieved, in proportion to their value, a technique used in Marshall Field’s by 1911.Footnote 122

Stores also banded together for mutual protection. From the eighteenth century, British retailers had organized to protect themselves from shoplifting and fraud via “trade protection societies” that shared knowledge of fraudulent practices and circulated the names, dates, locations, descriptions, and modus operandi of offenders. These sometimes also offered rewards for the apprehension of shoplifters and financial support for prosecutions.Footnote 123

New York’s Stores Mutual Protective Association both worked directly to suppress shoplifting and acted as a clearinghouse for information on active shoplifters.Footnote 124 From its establishment in around 1918 to 1933, it had amassed fifty-five thousand names of offenders. Stores could check apprehended shoplifters against their records; if no record was found, they might be released following a confession, but those already listed usually faced prosecution. By 1933, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Los Angeles, and Atlanta had similar systems.Footnote 125

However, stores were also in competition on deterrence to develop “a wholesome respect for the store!” in the eyes of the professional shoplifting community.Footnote 126 Many anti-theft devices were simple and invisible to the ordinary customer, such as wrapping all merchandise at the point of sale (to show it had been paid for) or using standardized, symmetrical displays (so that any removed article would be immediately noted).Footnote 127 However, adjusting display techniques to guard against shoplifting was not allowed to get in the way of maximizing sales. As one shop executive noted, “The advertising value of the high ornamental [display] structures … is often of sufficient importance to warrant use in spite of a subsequent increase in shoplifting.”Footnote 128

Another anti-theft device involved wiring merchandise to bells beneath the counters. A cord was run around the bottom articles in the bin, then down through the bottom of the counter, where it was wired to an electric alarm bell. This was designed to catch professional shoplifters who cleared out an entire merchandise bin in one go. This was said to be an effective deterrent, as even if the shoplifter left with some goods, he or she would be unlikely to return.Footnote 129 Prevention was key; as another retail executive explained, “As a general rule we do not want our managers to go any further than the quiet questioning of suspects and the securing of signed statements. We want them to prevent theft rather than to prosecute it.”Footnote 130

Professional shoplifters were more likely to be prosecuted than amateurs, but were also often dealt with by other means, partly to avoid lawsuits. As one executive explained, “Two things enable us to handle the specialists in … [a] somewhat summary way without inviting lawsuits against us. First, there is the technique we use in catching them without laying ourselves open to trouble. We don’t accuse them of stealing. We note where they have hidden the article or articles, point to the location and say, ‘Would you like to have the articles wrapped which you have there?’ After the opening step the rest is easy because the petty thief of this type, caught dead to rights, is so frightened that he is amenable to almost any suggestion.” Footnote 131

Authority to take action against shoplifters was typically restricted to only a few, well-trained staff. A 1934 W. T. Grant training manual instructed salesgirls: “NEVER ACCUSE ANYONE OF THEFT OR DISHONESTY. If you suspect anyone of trying to shop lift, you may approach her and say, ‘Do you wish me to wrap that scarf?’ or ‘Do you wish me to wait on you?’ If you are suspicious of anyone in the store, report all the facts PROMPTLY AND QUIETLY to the floorman.”Footnote 132 Even when policemen were invited into the store to help deter shoplifters, they were carefully briefed by the manager:

pointing out the danger of making an arrest inside the store, the danger of accusing, directly or by inference, anyone who may be taking goods to daylight for closer examination or who may be comparing goods on one counter with those on another to match colors … the policeman cannot be forbidden to make arrests because it is his sworn duty to arrest anyone he sees committing a crime. The manager must, however, discuss with the policeman the policies we follow in handling shoplifting cases, pointing out that we are far more interested in preventing theft than in prosecuting thieves.Footnote 133

British stores appear to have been somewhat more ready to bring prosecutions, possibly due to the lower typical damages in false arrest suits compared with the United States. In 1934, M&S employed 14 detectives, who were responsible for some 1048 shoplifting prosecutions (359 of whom were apprehended in Glasgow) in its 199 stores and for discovering 156 cases of staff dishonesty.Footnote 134 During 1937, they made 2338 apprehensions, comprising 1986 adults and 352 juveniles. The vast majority of adult shoplifters were prosecuted.Footnote 135 Most M&S store detectives were permanently based at the larger stores where shoplifting was rife, but a number worked in a mobile capacity, spending a few weeks at each store (called in at the request of the branch accountants).Footnote 136 Woolworths UK also switched to a more aggressive policy toward shoplifting from August 1928, in the face of extensive thefts by gangs of juveniles.Footnote 137

Conclusions

The retailers’ dilemma was that the very attributes that made a visit to a department store or large variety store enjoyable—its leisure appeal, with no obligation to purchase and freedom to browse a wide variety of attractive goods without the sales assistant breathing down their necks—were the same factors that attracted the shoplifter. Moreover, the greatest threat to the retailers’ merchandise came from the ranks of their own customers—many of whom regarded occasional pilfering in the stores they frequented as legitimate—an extension of shopping behaviors such as opportunistically buying a dress with the aim of returning it after it had been worn for a prestigious event, or even buying and returning it just before a sale, with an expectation that it could be repurchased at a sale discount.

Open display was integral to department and variety store business models, influencing every aspect of the business, from store layout to the numbers and roles of staff. Moreover, open display reduced staff costs, while increasing stockturn, thereby raising profitability. However, this system had changed the “ecosystems” of the stores, creating ecological niches for not only shoplifters, but other criminals, such as pickpockets and imposters, to flourish. To address this, the big stores had introduced store detectives and a variety of other measures to diminish stock “shrinkage,” but always with an eye to the bottom line. Stores made a clear distinction between the professional shoplifter who stole goods for sale, often targeting high-value merchandise, and the “amateur” who was often a regular customer. The latter should be deterred from stealing but not necessarily from patronizing the store, unless they proved persistent. Even then, being blacklisted was often used in preference to the costly business of prosecution.

However, the high damages awarded for false arrests and related charges in the United States proved an increasing threat. This incentivized litigation from both professional criminals who designed scams that would lead to their arrest and people who had genuinely been wrongly accused but might have been satisfied with an apology if they had not been aware of the generous damages sometimes awarded by the courts. America was (and is) a much more litigious society than Britain, with lawyers comprising 0.113 percent of the 1930 population, compared with only 0.047 for England and Wales in 1931, partly owing to Britain’s lower financial incentives for lawsuits.Footnote 138 Moreover, in Depression America, damages were inflated by the antagonism of local business elites—who featured prominently on juries—to variety chains that were squeezing local retailers’ profits. Furthermore, at least in some large cities, legal system corruption paved the way for bogus false arrest suits.

In the United States, fears of litigation deterred stores from apprehending suspects, even in clear-cut cases. Conversely, such lawsuits were much less common in Britain, probably due to the lower damages typically awarded, a less litigious culture, and no equivalent of the fix as a means of engineering shoplifting acquittals that opened the door to false arrest suits. However, while some British stores, such as M&S and Harrods, “considered it the best form of insurance to prosecute,” this does not appear to have acted as a substantial deterrent.Footnote 139 Like the office worker who knows that expense claims are rarely checked by the line manager, many shoppers continued to regard a counter of desirable items with no apparent oversight as an invitation to tip the balance of trade with the store in their favor by avoiding the bothersome intermediation of the cash till.

Acknowledgement

Grateful thanks for help with sources are due to the staff of the Baker Library, Harvard Business School; the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan; Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester Massachusetts; and the National Building Museum, Washington, D.C.; together with the following UK repositories: John Lewis & Partners Heritage Centre, Cookham; Harrods Archives, London; M&S Company Archive, Leeds; The History of Advertising Trust; the National Archives, Kew; and University of Reading Archives. I also thank Vicki Howard, Peter Miskell, and Nicole Robertson, participants of the Henley Business School International Business and Strategy seminar, and three anonymous referees, for comments on earlier drafts. All errors are mine.