As a new constitution comes to be embedded socially and legally, the landscape of power and relevance shifts. Some actors will prefer the previous status quo over the incoming system defined by new rights protections, new citizen expectations, and new judicial roles. As a result, these actors will have incentives to push back against constitutional embedding. This chapter explores power struggles in the midst of constitutional embedding in Colombia, examining how actors within the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government attempted to contest the growing power of the social constitutionalism in the country, particularly in its most visible features: the Constitutional Court and the tutela procedure. To date, these actors have failed to curb the impact of the 1991 Constitution, in large part because of the extent to which social and legal embedding have taken root and continued to reinforce one another.

In the early 1990s, the newly created Constitutional Court was one of four apex courts, and while tutela decisions ended at the Constitutional Court, other kinds of legal claims were understood to be settled upon decisions rendered by the Supreme Court, the Council of State, or the Superior Council of the Judiciary. As the years progressed, these various high courts jockeyed for position at the height of the judicial system. Each of these clashes became known as a “choque de trenes” (literally, a train wreck). In addition to increasing its power by facilitating tutela claims related to social rights (Taylor 2020a), the Constitutional Court also expanded its role by allowing tutela claims against judicial decisions (tutela contra sentencias) and by developing the idea of an unconstitutional state of affairs (estado de cosas inconstitucional), which could then be remedied through structural decisions (Rodríguez Garavito Reference Rodríguez Garavito2009, 2011). These maneuverings (which we might understand as successful efforts at legal embedding), alongside popular support (which is the result of successful social embedding), allowed the Court and the new constitutional order to weather criticisms and conflict within the judicial system. While some of these criticisms may be valid, my goal in this chapter is not to evaluate the relative merits of the criticisms of the Constitutional Court or the 1991 Constitution. Instead, I intend to track how the Court and the Constitution managed to maintain prominent positions in social and legal life in Colombia.

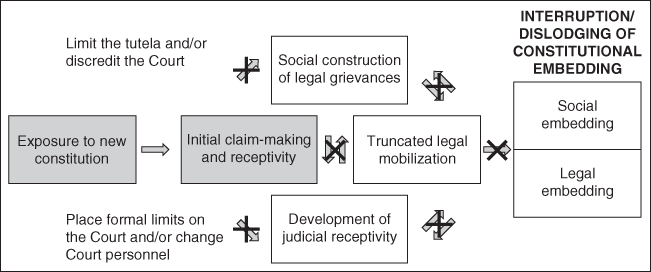

At various times, executive and legislative branch actors likewise attempted to limit the impact of the 1991 Constitution, particularly the tutela procedure and the Constitutional Court. These efforts took the form of outspoken criticisms, proposals to reduce the scope or even eliminate the tutela, and what some observers describe as attempts to game the appointment system for the Constitutional Court. Once again, however, the constitutional order has – at least so far – weathered these challenges, due to the institutional culture developed within the Court (a byproduct of legal embedding) and popular support, or what David Landau (2014) describes as the creation of a “middle-class constituency” for the Court and the tutela procedure (again, evidence of social embedding). Figure 7.1 shows how these various power struggles could interrupt or dislodge constitutional embedding, inhibiting the further social construction of legal grievances, the development of judicial receptivity, and/or the interplay between the two, effectively truncating the positive feedback process described in Chapter 2 that is integral to stable or longstanding constitutional embedding.

Figure 7.1 Powerful actors’ efforts to thwart constitutional embedding.

Constitutional embedding could be interrupted along the upper path (because of successful efforts to discredit the Constitutional Court in the eyes of everyday citizens or to limit the scope of access mechanisms, in this case, the tutela), the lower path (successful efforts to limit the Constitutional Court’s power relative to other branches of government and/or change out personnel), or both. The rest of this chapter turns to these efforts by the judiciary beyond the Constitutional Court and the other branches of government to limit the power of the constitutional order. It closes with a discussion of how social constitutionalism in Colombia endured despite these challenges.

7.1 Choque de Trenes and the Rise of the Constitutional Court

As noted earlier, when the 1991 Constitution went into effect, there were four apex courts in Colombia: the newly created Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, the Council of State, and the Superior Council of the Judiciary. Under this configuration, there is arguably a hardline separation between matters of ordinary and administrative jurisdiction and constitutional matters. The Supreme Court is the highest authority in matters of ordinary (i.e., civil, criminal, and labor) law, the Council of State in matters of administrative law, and the Constitutional Court for constitutional matters. However, the tutela procedure, as set out in Article 86 of the 1991 Constitution, could be used to assert potential fundamental rights violations (though act or omission) by any public institution in the country.

As early as 1992, some Colombians tried to use the tutela procedure in response to judicial decisions they disagreed with: they “tutela-ed” the other apex courts, asking the Constitutional Court to reconsider some element of the decision another court reached or the process by which it reached that decision. In fact, the first tutela decision reviewed by the Constitutional Court, T-006/92, included a challenge to a Supreme Court decision. As the majority of the three-justice panel, Eduardo Cifuentes and Alejandro Martínez (José Gregorio Hernández, dissented) revoked the Supreme Court’s decision, noting that “excluding the tutela action regarding the sentences of one of the Chambers of the Supreme Court of Justice means that, in this field of public action, so closely related to the protection of fundamental rights, there is no means of control of its constitutional behavior.”Footnote 1 Six other T-cases (tutelas) and one C-case (abstract review cases) dealing with the notion of tutelas against prior judicial decisions came before the Court in that year (T-223, T-413, T-474, T-492, T-523, T531, and C-543).Footnote 2 These decisions set out what became known as the vía de hecho doctrine.Footnote 3 Cifuentes was involved in six of these T-cases, Alejandro Martínez in four, and Ciro Angarita in three.Footnote 4

José Gregorio Hernández, writing for the majority in C-543/92, outlined the possibility for constitutional review of prior judicial decisions under certain circumstances, namely when a judge has allowed or created an unjustified delay in coming to a decision, when fundamental rights are ignored or threatened, and when “irremediable damage” may occur.Footnote 5 He cautioned, though, that “it is not within the powers of the tutela judge to interfere in a judicial process already in progress, adopting decisions parallel to those previously issued, since such a possibility undermines the concepts of functional autonomy and independence.”Footnote 6 In this particular case, Hernández believed that these conditions were not met. Eduardo Cifuentes, Ciro Angarita, and Alejandro Martínez – the three justices on the Transitional Court who came from academic backgrounds (as discussed in Chapter 5) – offered a dissenting view, arguing that this tutela should proceed, precisely because this claim suggested a potential violation of fundamental rights through the previous decision. In other words, their view was that this particular claim did not reopen a settled legal matter, but instead posed a new question relating to fundamental constitutional rights.

This kind of claim came to be known as the tutela contra sentencias,Footnote 7 which reflects that the dissenting view eventually won out. In fact, during the following year, Cifuentes, Hernández, and Martínez, in T-079/93, allowed a tutela claim against a prior judicial decision to move forward, though they ultimately affirmed the Supreme Court’s decision. At least five other decisions in 1993 by the Constitutional Court further bolstered the possibility of tutelas contra sentencias. In T-158/93, Justices Vladimiro Naranjo, Jorge Arango Mejía, and Antonio Barrera reiterated the vía de hecho doctrine, which holds that “the tutela action is appropriate when it is exercised to prevent public authorities, through de facto means, from violating or threatening fundamental rights.”Footnote 8 By 1994, all members of the First Court (1993–2000), regardless of left–right ideology, affirmed the possibility of the tutela contra sentencias.Footnote 9 Just over ten years later, in C-590/05, the Constitutional Court issued a decision that expanded the list of appropriate instances of the use of the tutela contra sentencias to eight situations.Footnote 10

The broader legal establishment was slower to adopt the tutela contra sentences. In a careful analysis of tutela claims involving the Supreme Court and the Council of State during the 2000s, Manuel Quinche Ramírez (2007: 292) concludes that these “judges, when faced with the dilemma of choosing between substantive law and the interpretation of form, prefer[red] the latter, even if fundamental rights are violated with the choice.”Footnote 11 In fact, he notes that two chambers of the of the Supreme Court, the Labor Cassation Chamber and the Criminal Cassation Chamber, were especially reticent. Citing Óscar Dueñas Ruiz (Reference Dueñas Ruiz1997: 42–59), Quinche Ramírez explains that the “ideological tendency” of judges who sat in these chambers had “historically been in favor of restricting the rights of Colombians” (Quinche Ramírez Reference Quinche Ramírez2007: 291).Footnote 12 The Supreme Court and the Council of State made five main arguments as to why the tutela contra sentencias should be limited (Quinche Ramírez Reference Quinche Ramírez2007: 307–9). I paraphrase those arguments here:

1. There is no defined hierarchy among the “high courts.” Therefore, each high court should have the final say on whatever matters fall within their jurisdictions. The tutela contra sentencias thus undermines the structure of the judiciary.

2. The principle of res judicata ought to stand: if a matter has been decided, it should not (or cannot) be reopened by the same parties. The tutela contra sentencias does exactly that.

3. Judges should have functional autonomy. The tutela contra sentencias allows for (unconstitutional) interference by constitutional judges into matters than have already been examined and interpreted.

4. Judges have independent legal specialties and functions. Those specialties (e.g., administrative law) have their own universe of norms and arguments. With the tutela contra sentencias, constitutional judges could revise or reverse a process that had been constitutionally compliant (that fell outside of their specialty).

5. The Constitution and constitutional principles must be defended. The tutela contra sentencias can violate constitutional principles and specifically allows for impunity.

Quinche Ramírez highlights a provocative statement issued by the full chamber of the Supreme Court on March 24, 2006 to illustrate the fifth argument:

Faced with the new gap opened by the Constitutional Court to impunity, the Supreme Court of Justice calls on the judges across the country, without being discouraged, to continue to apply the Constitution and the law with full independence and autonomy, and absolute respect to the human story of the accused, whatever it may be, but guided by the impartiality imposed on them by their condition as representatives of the Estado Social de Derecho [social state under the rule of law] that governs us.Footnote 13

Here, the Supreme Court not only grumbled about the tutela contra sentencias, but explicitly called on judges sitting on lower courts to adopt an alternative view of constitutionalism and rights protections than the one promoted by the Constitution Court.

In a similar vein, the Council of State, following a tutela against one of their sentences in November 2015, claimed that actions of the Constitutional Court “constitute[d] a de facto route and lack[ed] validity.” The Council of State further argued that their original decision “is unchangeable, unchallengeable and definitive.” They even called for copies of their statements to be sent to “the Commission of Accusations of the House of Representatives, so that they could initiate a criminal process against the magistrates of the Constitutional Court” (Quinche Ramírez 2020: 97). Rather than addressing the broader judicial community, here the Council of State appealed (unsuccessfully) to members of Congress to check the Constitutional Court’s power.

In the face of these criticisms, the Constitutional Court continued to affirm the vía de hecho doctrine and the legitimacy of the tutela contra sentencias. From the perspective of justices on the Constitutional Court, the Constitution explicitly tasked the Court with defending fundamental rights, and the new constitutional order gave primacy to constitutional legal matters over all others. Examining a violation of due process during a proceeding does not reopen settled questions of law from the proceeding; instead, it allows for the narrow consideration of whether or not fundamental rights were protected. For example, Manuel José Cepeda, writing in SU-1219/01,Footnote 14 held:

The [Constitutional] Court notes that the judges are independent and autonomous. It also underlines that this independence is to apply the rules, not to stop applying the Constitution. A judge cannot invoke his independence to avoid the rule of law, much less, to stop applying the supreme law that is the Constitution. The alternative, unacceptable in a constitutional democracy, is that the meaning of the Constitution changes according to the opinion of each judge.Footnote 15

Read uncharitably, this view would seem to contradict a 1992 tutela decision referenced in Chapter 5 (emphasis added):

There is a new strategy to achieve the effectiveness of fundamental rights. The coherence and wisdom of the interpretation and, above all, the effectiveness of the fundamental rights in the 1991 Constitution, are ensured by the Constitutional Court. This new relationship between fundamental rights and judges means a fundamental change in relation to the previous Constitution. This change can be defined as a new strategy aimed at achieving the effectiveness of rights, which consists of giving priority for the responsibility for the effectiveness of fundamental rights to the judge, and not to the administration or the legislator. In the previous system, the effectiveness of fundamental rights ended up being reduced to their symbolic force. Today, with the new Constitution, the rights are what the judges say through the tutela.Footnote 16

More charitably, we might understand these two positions as in congruence, suggesting that only constitutional judges should be involved in the interpretation of constitutional rights and constitutional law. Beyond these constitutional defenses, the Court also pointed to the principle of universal jurisdiction and the practices of international courts as well as courts in other Latin American countries as undercutting the arguments against the tutela contra sentencias that involved reopening settled matters.Footnote 17

Many of the judges and lawyers who I interviewed expressed some sympathy for the positions of the Supreme Court and Council of State, if not outright agreement, even when they were otherwise limited in their criticisms of the Constitutional Court and the new constitutional order. For example, Hernando Herrera, who had served as an assistant during the Constitutional Assembly and later as a conjuez, or alternate justice, in the Council of State, explained that the Constitutional Court has become a “super court,” because the tutela contra sentencias allows it to revise the decisions of other courts. He outlined the perspectives of both sides in the following way:

It is all very well for citizens to disagree, but not for magistrates and judges to fight, and this is a war of scope [or competence]. I understand the concern of the Supreme Court and the Council of State … “If I am the most important body in my jurisdiction, how can another judicial body come and tell me that what I did was wrong? With respect to what I am doing, nobody is supposed to handle it better, to the extent that there are specialized jurisdictions here.” And on the other hand, the Constitutional Court says, “yes, but I have the job of guaranteeing the rights of all citizens and the constitution gives me the possibility of reviewing tutela claims, and then I can choose the tutelas related to sentences of the high courts.”Footnote 18

José Bonivento – who had served as a justice on and president of the Council of State, the Civil Cassation Chamber of the Supreme Court, and the Superior Council of the Judiciary, in addition to being nominated but not selected for the Constitutional Court in 1993 – reflected on the tutela contra sentencias and the choque de trenes, saying:

That was indeed one of the great disputes, confrontations … [The Supreme Court and the Council of State] consider that their decisions cannot be touched and that there is no room for tutela, but the [Constitutional] Court has done it. It is being done haphazardly and piercing everything. And the truth is that today the Constitutional Court reviews.Footnote 19

He draws a clear connection between the tutela and the power to review the decisions of other courts. In his view, the Constitutional Court has embraced this function and has claimed the status of the superior court. Juan Carlos Esguerra highlighted a further critique of the Court, stating that, essentially, “lawsuits do not end in Colombia … [because there are] seven opportunities to decide the same thing.”Footnote 20 Constitutional Court justices might push back against Esguerra’s characterization, but undoubtedly, the tutela contra sentencias does provide another opportunity to challenge the process underlying legal cases.

That said, as Manuel Quinche Ramírez explained to me in an interview in 2016, while the “tutela contra sentencias had once been considered sacrilegious, now it is something common and accepted.”Footnote 21 Lina Mogollón, who has experience working at each of the three high courts that figure prominently in this chapter – the Constitutional Court, Supreme Court, and Council of State – concurred, saying:

Right now, it’s a little easier. It was very difficult at the beginning. I think that is because of the nature of the judges. We had very established judges, who had studied law from a positivist perspective, only the law … At the beginning it started many clashes. They [the different high courts] delegitimized each other … [But] it has been twenty-six years, and the perspective is already changing – a little because the judges [on the bench now] are new judges. They are judges who have been studying constitutional law since the 1991 Constitution.Footnote 22

This view comports with that of Juan Carlos Henao, who served as a justice on the Constitutional Court between February 2009 and April 2012. He recollected feeling “discomfort, obviously, because the other magistrates [on the other high courts] do not like it, no way … but that is the way the system has worked in Colombia. That is developed by very clear jurisprudence and the legislator has never wanted to change that. It has always allowed the Constitutional Court to have that possibility [of reviewing tutelas contra sentencias].”Footnote 23 The process by which Henao arrived at the Constitutional Court is notable: he was nominated by the Council of State, after having been both a clerk and an alternate justice in that body.

Mario Cajas, a law professor and historian of the Colombian Supreme Court at the Universidad ICESI, suggested that the tension was real, but perhaps not reflective of actual confrontations between the high courts. He told me:

When one reviews the jurisprudence, the cases are not that many. Some work that a colleague of ours did in 2008 showed that there were forty sentences in a year of a thousand and something that were produced. There were not that many and the cases where the [Constitutional] Court reversed Supreme Court decisions were much less than 10 percent. What happens is that these cases are cases of prominence.Footnote 24

These high-profile cases shape discourse, if not everyday practice. Cajas further noted that in practice the Supreme Court has seemed to shift in its approach to these kinds of cases:

If you do a review of those twenty-odd years you can also see where, for example, the Criminal Chamber has tended to get closer to the constitutional guidelines. The Labor Chamber is the one that is furthest away, and the Civil Chamber is in the middle. But we went from a moment where the three were far apart [from constitutional guidelines] and now they are getting closer.Footnote 25

Francisca Pou Gimenez (2018) has also documented the shift of the other high courts to fall more in line with the Constitutional Court’s stance relative to rights protections, specifically with respect to the rights of nature (or of rivers and forests being rights-bearers).

Nothing about the initial discourse between the other high courts and the Constitutional Court suggested that either was likely to back down from their oppositional positions. However, the Supreme Court and Council of State could not eliminate the tutela contra sentencias on their own. That would require legislative action.

7.2 Political Attacks on the Constitutional Court and Tutela

In addition to facing skepticism and even hostility from the other high courts, the Constitutional Court and the new constitutional order were also subject to challenges from the executive and legislative branches of government, particularly during the presidencies of Ernesto Samper (1994–1998) and Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010). Samper’s proposals focused on eliminating the tutela contra sentencias and the ability of the Constitutional Court to review declarations of states of “internal commotion” (which would allow the executive a broader range of powers to deal with the emergency situation). As David Landau (2014) documents, however, the Samper administration only had narrow majorities in both houses of the legislature and could not count on disciplined party voting.Footnote 26 Samper faced an impeachment vote in 1996 and his popularity plummeted as evidence connecting his campaign to the Cali cartel mounted.Footnote 27 His proposed reforms did not make it out of the committee stage without fundamental revision. The Council of State and Supreme Court sponsored their own reform proposals, which made it past the committee stage, but could not garner the required majority of House votes. The then-president of the Council of State, Juan de Dios Montes, vented publicly about feeling disrespected by members of the House and his frustration that the president of the Constitutional Court, Antonio Barrera, had framed the proposal as “a conspiracy against the tutela,” “inciting the population” in the process (Gutierrez Reference Gutierrez1997).

The story of the Uribe-era reforms is much the same. Rodrigo Uprimny (Reference Uprimny2005: 8) summarizes five strategies undertaken by the Uribe administration to reduce the power of the Constitutional Court:

1. Exclude the high courts from processing tutelas, due to the congestion that afflicts these courts;

2. Limit the tutela in the case of social rights, due to the economic imbalances caused by judicial interventions in this field;

3. For reasons of legal certainty, prohibit the tutela contra sentencias;

4. Limit the use of the tutela in labor matters; and

5. Prohibit tutela decisions from involving modifications to budgets or national or local development plans.Footnote 28

The most notable of these ultimately unsuccessful efforts were mounted in 2002, 2004, and 2006. Looking to Legislative Act 10 of 2002 in the Senate as an illustrative example, the act sought to reconfigure the judicial realm, its practices, and its appointment procedures. Quinche Ramírez (Reference Quinche Ramírez2007: 321) explains that the part of this reform oriented toward the 1991 Constitution seemed to have “a single objective: to make the tutela a merely nominal action of minimal effectiveness.”Footnote 29 The reform would limit due process claims through the tutela and the tutela contra sentencias, in addition to eliminating tutela claims for social and economic rights, specifically undercutting the conexidad doctrine.Footnote 30

In an interview with Everaldo Lamprea, Manuel José Cepeda, who served on the Constitutional Court between 2001 and 2009, reported that all of the justices on the Court came together regardless of their ideological positions to oppose these reforms. They took a proactive approach, attending academic events and issuing statements to the media about the value of the tutela procedure.Footnote 31 For example, the president of the Court at the time, Eduardo Montealegre, gave an interview with El Tiempo (Amat Reference Amat2003), in which he critiqued these proposals, holding that Minister of the Interior Fernando Londoño’s real goal was to “end the Constitutional Court”:

But the road goes further: Minister Londoño intends to break the Constitution, with a clear strategy of dismantling the fundamental principles of the Constitution of ’91. I say dismantle because he is doing it in parts, in pieces. If one begins to join those pieces, one discovers that he is going after a totally different model of state.

The efforts of the Constitutional Court justices were successful: none of these proposed reforms ever became law.Footnote 32 Though Uribe retained much more popular support than Samper, and though his political coalition was often successful in pushing policy through Congress, his attempts to reform the constitutional order also failed. The Uribe administration withdrew the 2002 and 2004 proposals before either was put to a vote (Landau 2014).

That the Uribe administration opposed the Constitutional Court’s power and actively undertook efforts to limit it should not be read as implying a harmonious relationship with the other high courts. Javier Revelo-Rebolledo (Reference Revelo-Rebolledo2008) has documented the extent to which the Uribe administration attempted to influence the working of the Supreme Court in particular, from changing the law as it pertains to sedition (to counteract a Supreme Court decision finding that the crime of sedition did not apply to paramilitary actors) to Uribe himself calling the president of the Supreme Court, César Julio Valencia, to “check on” the status of investigations into the conduct of his cousin. What’s more, the Department of Administrative Security (DAS), the state security and intelligence agency, surveilled and illegally wiretapped Supreme Court justices while those justices were opening up investigations on members of Congress for their connections to paramilitary groups.Footnote 33 Rodrigo Uprimny (Freedom House Freedom House 2011) reports that:

By July 2011, more than 110 members of Congress were being investigated by the judiciary, especially by the Supreme Court, which is charged with conducting criminal investigations of legislators: 36 have been convicted, 41 were on trial, and 36 more were under formal investigation. Most, though not all, of the investigated or convicted politicians formed part of President Uribe’s coalition. Uribe and other officials responded with frequent, vociferous rhetorical attacks on the court – and with or without the president’s knowledge – retaliation by the DAS.

Thus, while the Uribe administration and the Supreme Court and Council of State may have shared some goals (e.g., the elimination of the tutela contra sentencias and the reduction in the Constitutional Court’s powers), they did not form a stable coalition to push for these changes.

In more recent years, as many of the lawyers and legal academics that I interviewed noted, members of Congress who supported these reform efforts seem to have developed a new strategy to try to reduce the power or effect of the Constitutional Court, through “mediocrity-packing.” In other words, rather than trying to limit the Court through changes in the institutional structure or through the nomination of formalistic or conservative judges, some members of Congress have tried to cut off the sense of connection between the Constitutional Court and the people by nominating judges who are not viewed as “superstars.”Footnote 34 It remains to be seen whether or not this strategy will pay off. For now, though, the Constitutional Court and its proponents have won social and political battles throughout the 1990s and 2000s that have ensured that social constitutionalism has remained embedded in Colombia.

7.3 Pais de Tutela and the Endurance of the Constitutional Order

So, what exactly happened? Why did these criticisms and proposed reforms ultimately fail to meaningful alter the power of the Constitutional Court, the scope of the tutela, or the stability of the constitutional order? In short, constitutional embedding had occurred, in both its social and legal forms. The social element reinforced the legal, as citizens conveyed broad support for the tutela and the Constitutional Court, and the legal element reinforced the social, as judges (especially the justices of the Constitutional Court) legitimated citizen use of the tutela and spoke out in favor of the constitutional order. Attitudes and interests overlapped and compounded one another, such that relatively powerful actors in the legal and political spheres could not chip away at or disembed social constitutionalism in Colombia.

In his 2014 dissertation, David Landau identifies and catalogues the ways in which the Constitutional Court was able to garner public support and weather politically motivated attacks on its power. He explains that “the Court cultivated a number of different bases of support, and these bases of support – elements of the academic community, civil society, and the general public – have protected the Court at key moments” (Landau 2014: 129). Efforts to cultivate these bases of support included direct and indirect efforts at communication with the public, through symbolic decisions, public audiences, and monitoring commissions of civil society groups. The use of these mechanisms allowed the Court to “construct a mobilization of civil society that [would] then pressure the other branches of government” (Landau 2014: 210). In other words, these efforts – rather than “independence by design” or the existence of political fragmentation – enabled the Court to exercise judicial independence and protect itself from both court-curbing and court-packing efforts.

The Constitutional Court also sought to broaden its powers to issue structural decisions in response to tutela claims, through something called the “estado de cosas inconstitucional,” or state of unconstitutional affairs (Rodríguez Garavito Reference Rodríguez Garavito2009, 2011). The underlying idea is that the individual tutela claims that make it to the Constitutional Court reflect deeper, structural conditions of rights violations – so a structural decision is necessary to remedy those violations. Eduardo Cifuentes wrote the decisions that outline such a state. First, in SU-559/97, a case regarding pensions for educators, he noted that the situation under investigation amounted to a “state of affairs that is openly unconstitutional.”Footnote 35 In T-153/98, Cifuentes settled on the language of the estado de cosas inconstitucional:

[The Court] has used the unconstitutional state of affairs in order to seek a remedy for situations of violation of fundamental rights that are of a general nature – insofar as they affect a multitude of people – and whose causes are of a structural nature – that is to say that … their solution requires the joint action of different entities. Under these conditions, the Court has considered that given that thousands of people are in the same situation and that if they all resorted to the tutela, they could unnecessarily congest the administration of justice, the most appropriate thing to do is to issue orders to the competent official institutions with the so that they put into action their powers to eliminate this unconstitutional state of affairs.Footnote 36

Eleven other decisions in 1998 invoked the unconstitutional state of affairs (C-229, SU-250, T-068, T-289, T-296,T-439, T-535, T-559, T-590, T-606, T-607). T-024 of 2004, a case having to do with the rights of internally displaced persons, solidified the figure of the unconstitutional state of affairs. Further, as described in Chapter 5, the Court also issued a structural decision on the healthcare system with T-760/08 (without declaring an unconstitutional state of affairs). Each of these structural decisions undoubtedly impacted public policy and government spending,Footnote 37 at once propelling the Constitutional Court into debates typically resolved in the legislature rather than the courts and demonstrating to the Colombian citizenry that the Court could be responsive even when other branches of government faltered.

The Court could not have made such aggressive moves in countering the Supreme Court, Council of State, and various presidential administrations had citizens not embraced the Court, which they did primarily through the tutela mechanism. In the early 1990s, citizens did not necessarily understand the purpose, promise, or limits of the tutela, but nonetheless experimented with it. As Julieta Lemaitre describes, “it was more an expression of despair and hope than anything.”Footnote 38 Yet, as documented in Chapter 4, citizens moved beyond the experimentation stage quickly and adopted use of the tutela into their everyday practices. In an interview in 2016, Diana Fajardo – who worked as a clerk at the Constitutional Court between 2009 and 2013, and who would be appointed to the Court as a justice in 2017 – explained to me that:

The citizens took ownership of the Constitution, which had never happened before. That is, before only law students read the Constitution. No more. Now you have the common citizen, everyone. It is impressive, they feel their constitution as a birthright, and the tutela is even more untouchable for the Colombian citizen.Footnote 39

In other words, the citizenry embraced the tutela, which rendered the tutela politically untouchable (which in turn ensured a large role for the courts in Colombian life). In an op-ed in El Espectador in 2010, Alejandro Gaviria – then the minister of health – lamented that Colombia had become “el país de la tutela,” or the country of the tutela.Footnote 40 Whether one supports the tutela or finds it troubling, its centrality in the Colombian social and legal imaginaries cannot be disputed. The combination of the newly empowered Court and newly empowered citizens – or, stated differently, the combination of legal and social embedding – safeguarded the expansive model of social constitutionalism in Colombia.