A comparison of the organ and orchestral programs at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 offers a fascinating case study in nineteenth-century concert programming. Theodore Thomas, director of the fair's Bureau of Music, sought to present a hierarchical model of orchestral music that ultimately failed disastrously before the fair was half over. In his book, Sounds of Reform, Derek Vaillant asserts, “The collapse of the music bureau under Thomas produced a Hobson's choice between sacralized or popular music that left no official space for alternative models as a facet of group identity and civic belonging.”Footnote 1 However by examining the series of solo organ concerts that commenced just as the orchestral program terminated, we see that this statement is not entirely true. Although they have been largely overlooked in modern musicological scholarship, the series of organ concerts in Festival Hall were an important part of the musical life of the World's Columbian Exposition, and they were successful in engaging a variety of listeners.Footnote 2 I argue that they occupied the space between the binary categories of “artistic” and “popular” concerts adopted by Thomas, thus providing an important example of a successful alternative programming model for classical music in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 3

The organ recital series at the World's Columbian Exposition was the most prestigious and well-publicized series of organ concerts that had taken place in the United States to date. From July 31 through October 31, 1893, twenty-one of the leading U.S. organists, along with Alexandre Guilmant of Paris, performed sixty-two solo organ recitals on a new four-manual instrument built by Farrand & Votey of Detroit for the exhibition's 7000-seat Festival Hall.Footnote 4 Clarence Eddy, the nation's preeminent organ virtuoso, himself a Chicagoan, was given free rein to design the exhibition instrument and organize the recital series.

Eddy's leadership of the organ series provides a stark contrast to that of Theodore Thomas, the head of the fair's Bureau of Music and director of its Exposition Orchestra. Thomas and Eddy both embraced the overarching mission of the fair as a testimony to “progress” and endeavored to program music that would both entertain and educate fair audiences. In turn, they were both supported and encouraged by respected contemporary music critics such as W. S. B. Mathews, George P. Upton, and Everett Truette. However, unlike Thomas's symphony series, Eddy's organ series was an overwhelming success. The organ series effectively balanced the dual aims of education and entertainment by offering a slate of accomplished performers, accessible programming, and performance practice guided by the notion of “progress.” By examining the repertoire performed, interpretative choices made, and reviews and criticism penned in contemporary journals, we see that Eddy and his colleagues were open to embracing accessible programming that would serve as an influential model for secular organ concerts in the United States.

Scope of Music at the Fair

Originally planned to mark the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage to the Americas, the primary theme of the World's Columbian Exposition was “progress.” All departments strove to create exhibits and programs that demonstrated human progress and, in particular, the United States’ development from a collection of settlements to a thriving industrial society with a respectable arts scene.Footnote 5 The idea of progress—no doubt related to the acceptance of Charles Darwin's new ideas of evolution in this period—transferred nicely to the discipline of music. Chicago music critic and editor of the magazine Music, W. S. B. Mathews, articulated this belief in his eloquent descriptions of his hopes for music at Chicago's Fair: “Now the prevalent doctrine of human progress is that of evolution. Were such a hypothesis well founded in no art should there be more brilliant evidence of it than in the highly specialized art of music.”Footnote 6 The progress of music would be highlighted in various ways at the fair. In the exhibition halls, U.S. musical instrument makers would display their technical achievements. In the music halls, U.S. orchestras would demonstrate the “evolution” of musical style by performing works of great composers at the highest level. In the symposia of the World's Congress Auxiliary, musicologists would gather to present lectures on the development of musical style.Footnote 7

The head of the World's Columbian Exposition planning team, director general George R. Davis, shaped the fair's mission as a demonstration of progress. He also confidently stated that the many educational exhibits and programs would spark the “cultivation of taste” in the United States.Footnote 8 The official guide to the exposition reinforced this focus on cultural education: “It is presumed at the outset that the great majority of visitors are those who seek to enlighten themselves regarding the progress which the world has made in the arts, sciences and industries. To him who enters upon an examination of the external and internal exhibits of this the greatest of World's Fairs a liberal education is assured.”Footnote 9 Davis and his colleagues believed the fair would attract new audiences for the arts that would then result in what they considered to be a more civilized society.Footnote 10 In an era of increasing industrialization, the fair was also to be an opportunity to educate the growing working class.Footnote 11

The Bureau of Music, under the leadership of Theodore Thomas, and faithfully supported by Mathews, fully embraced the fair's mission of progress and education from the start. In its first official announcement, the Bureau of Music articulated its goals for the music program:

(1) To make a complete showing to the world of musical progress in this country in all grades and departments, from the lowest to the highest.

(2) To bring before the people of the United States a full illustration of music in its highest form, as exemplified by the most enlightened nations of the world.Footnote 12

The Bureau then outlined an ambitious plan of concerts, classified into ten categories according to location, ensemble type, and style. The crown jewel of the official program was the Exposition Orchestra under the direction of Thomas. This group would perform “semi-weekly orchestral concerts in Music Hall” on the symphony series and would serve as the primary orchestra for oratorios and choral concerts in Festival Hall.Footnote 13 On the days when the orchestra was not already performing, it would offer “popular concerts of orchestral music” in Festival Hall.Footnote 14 The Bureau also hosted official series featuring international guest ensembles, singing societies, children's choruses, chamber music groups, and organists. In addition, the Bureau invited various brass bands and wind ensembles to play in an unofficial capacity on the bandstands and exposition grounds.Footnote 15

Thomas knew from his previous experience with national exhibitions and his concert travels that exposition attendees would want to be entertained when they visited the fair.Footnote 16 However, his passion lay with what the Bureau of Music announcement termed music of “the highest form.” Thomas sought to emphasize this theme in his programming, at least in the orchestral sphere, where he had exclusive artistic responsibility. In a calculation that would have later implications for the success of the music program, Thomas chose to make a clear programming distinction between the two types of orchestral concerts. Programs would either be what he termed “popular,” as in the “Popular Concerts of orchestral music in Festival Hall,” or “artistic,” as in the “Semi-weekly orchestral concerts in Music Hall.”Footnote 17 The location for the concerts also implied a “serious” or “popular” tone. The smaller Music Hall, with its 2,200 seats, was designated for “serious” music, while the 7,000-seat Festival Hall could house programs of large choruses and ensembles that, in the words of the Bureau, would be “appealing to universal tastes and talents.”Footnote 18 Additionally, concert etiquette in the two halls differed. Music Hall concert-goers would be asked to pay an extra one dollar admission fee and were expected to quietly sit for the entire concert, whereas the Festival Hall matinees did not require an admission charge and attendees would be allowed to come and go in between pieces. In this way, the larger venue served a similar purpose to the fair's exhibit halls, where people could engage with the content at their own schedule and pace. Festival Hall's close proximity to the train station allowed for greater foot-traffic and visibility, but also meant that the accompanying noise precluded close listening.Footnote 19

This decision to organize the fair's orchestral concerts into “popular” programs or “artistic” ones was duly noted and accepted by the press and shared with potential concertgoers. Mathews outlined the distinction in his commentaries leading up to the fair:

Naturally there will be a vast amount of music which is purely incidental—for spectacle, and amusement. In all this there will be an occasional thread of something better than mere amusement, but entertainment will be the ruling motive. Under this head will be the bands, and the processions, the popular concerts of orchestral music and the like. But besides this there will be a great deal of the very highest and most finished performances of symphonies and other high-class music.Footnote 20

After receiving the Bureau's memo, the Chicago Daily Tribune (George P. Upton, music editor) jubilantly announced plans for the music program with the headline, “Splendid Program Arranged by the Bureau of Music.” It highlighted the two distinct categories of orchestral concerts, noting that the “popular” matinees would carry a “musical educational value which cannot be overstated. There will be in attendance thousands of persons whose only knowledge of instrumental music consists of such as has been gained by listening to the playing of the country brass band.”Footnote 21 Presumably, he expected the exposure to orchestral music would elevate the tastes of the “masses” and provide them with a more cultivated alternative to the music-making they were used to.

Thomas, Mathews, and Upton all wanted to generate an avid audience for classical music in Chicago, and they believed that could be achieved with a hierarchical program. It is interesting that Thomas chose to forgo the more democratic approach to audience engagement that he had established with his earlier Chicago Summer Nights Concerts. From 1877 to 1890, Thomas successfully presented nearly 400 orchestral concerts in the multi-use “Exposition Building” on Lake Michigan to an audience of mixed social and economic backgrounds.Footnote 22 As Derek Vaillant has shown, the Chicago musical aesthetes were not altogether comfortable with the concept of mixed audiences for high art music.Footnote 23 Thomas himself dismissed the programming as “of a lighter character.”Footnote 24 Presenting “popular” concerts seemed to be something Thomas merely endured. In the frontispiece to his 1905 autobiography, he wrote, “The master works of instrumental music are the language of the soul and express more than those of any other art. Light music, ‘popular’ so-called is the sensual side of the art and has more or less the devil in it.”Footnote 25 When he established the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1891, Thomas began pushing for more challenging programs, which would then necessitate stricter concert etiquette.Footnote 26 The separation of “popular” and “artistic” at the fair would allow connoisseurs to enjoy the great masterworks in Music Hall, while the masses would be unwittingly educated every time they attended a “popular” concert.

Despite the Bureau's claim that the official concerts would present a showing of all music “from the lowest to the highest,” the scope of the concerts in Music Hall and Festival Hall, and the orchestral concerts in particular, was quite narrow. A whole host of music presented at the fair fell outside the Bureau of Music's purview. The Bureau of Music managed the music in the fair buildings, but there were countless performances in outdoor bandstands, on the Midway Plaisance, and in surrounding commercial establishments that contributed to the rich musical life at the fair.Footnote 27 Thomas described these musical offerings as “popular,” but he also used the term to describe a particular type of orchestral concert.Footnote 28 So what did the Bureau of Music mean when they described a classical music program as “popular?” A brief comparison of the programming at the ticketed symphony concerts and the free orchestral matinees offers a clue.Footnote 29

Before his resignation, Thomas led the Exposition Orchestra in sixteen ticketed symphony concerts on the Music Hall Series. These programs tended to feature instrumental genres Thomas believed to be of a more serious nature: complete symphonies, concertos, symphonic poems, and orchestral overtures. The program from May 3, 1893 offers a good example of Thomas's approach to programming in this venue:Footnote 30

- Symphony No. 3, “Eroica”

Beethoven

- Concerto for Piano, in A minor

Schumann

- (Mr. Paderewski, pianist)

- Symphonic Variations, op. 78

Dvorak

- Hungarian Fantasia

Liszt

- (Mr. Paderewski, pianist)

Music Hall programs also reveal Thomas's fondness for presenting programs of a single composer in order to give a complete picture of a composer's output and style. Thomas devoted programs to Schubert (May 5), Brahms (May 9), Beethoven (May 12), Raff (May 26), and Schumann (June 9).Footnote 31 The programs on the whole primarily featured Austrian and German composers, although Thomas also sought to promote the achievements of U.S. composers with three mixed programs on May 23, July 6, and July 7.Footnote 32 Thomas included the music of only two French composers and excluded Italians from these programs altogether.Footnote 33

In contrast, a daily “popular” matinee in Festival Hall looked something like this program from May 6, 1893:

- March, “Rakoczy”

Berlioz

- Overture, Der Freischütz

Weber

- Allegretto from Symphony No. 7

Beethoven

- Hungarian Dances, 17 to 21

Brahms (Orchestration by Antonin Dvořák)

- March Funèbre

Chopin (Orchestration by Theodore ThomasFootnote 34)

These free orchestral matinees generally included five to ten works in a diversity of genres. Marches, overtures, dances, opera scenes, and movements from familiar symphonies (as opposed to complete symphonies) were the main fare. French and Italian composers appeared more frequently, so the result was a more even representation of European nationalities instead of the Austro-Germanic dominance exemplified on the symphony programs. Thomas had ample experience programming “popular” concerts with success on his many national tours. His “popular” programs at the fair more closely mirrored those of the earlier Chicago Summer Nights Concerts.Footnote 35 He believed the familiar works of shorter length and a variety of styles and composers would be more accessible for the “universal masses” while the programs of longer symphonic works would appeal to the musical elite.

Adrienne Fried Block's analysis of concert programming in nineteenth-century New York offers important insights as to why and how nineteenth-century concert organizers distinguished between “popular” and “serious” music. Block argues that the nineteenth-century practice of categorizing a piece of instrumental music as “popular” or “serious” related to the aesthetics of idealism that was prevalent particularly among German critics and later among German immigrants to the United States. In this thinking, pieces that were based on thematic elements, such as a sonata-form structure, appealed to the intellect and were therefore thought to have a higher artistic quality. Operatic or orchestral overtures, marches, and dances were thought to appeal to a broader audience.Footnote 36

Thomas's writings and programming decisions at the fair bear out Brock's analysis. Interestingly, Thomas believed there would be enough like-minded music-lovers at the fair to support the cost of a full-time Exposition Orchestra. The financial success of the orchestral program depended on robust ticket sales for the symphony concerts. Given the relative novelty of well-attended symphony concerts with strict concert etiquette in Chicago, Thomas's plan seems inconsistent with the times.Footnote 37 Even though a committed musical elite with financial capital had lured Thomas to Chicago, mixed reports of the initial Chicago Symphony seasons hardly presented overwhelming evidence of a large audience for such programs.Footnote 38 No doubt Thomas knew the plan to be risky, but perhaps the idealism of the day that touted progress and edification was too tempting.

Unfortunately, the plan turned out to be wishful thinking. In the end, Thomas was not able to realize his ambitious program of music for the fair. He had been confident that his symphony programs would generate enough revenue to support the salaries for the orchestral musicians, but fairgoers seemed loath to pay the one–dollar admission to the concerts, on top of the 50-cent general admission price, and then devote almost two hours of their day at the fair to a concert.Footnote 39 It seemed that people would much rather come and go as they pleased at the free “popular” matinees, and in fact there were reports that these were well-attended.Footnote 40 To be fair, the disappointing attendance at symphony concerts was probably not all due to programming. Bad weather, the onset of a nationwide financial crisis, and reports that some of the fair's exhibits were not yet complete (notably the Ferris Wheel, which was not ready until mid-June)Footnote 41 made for disappointing general admission turnout in the first three months.Footnote 42

For all Thomas's grand ambitions, his directorship unfortunately ended up a catastrophe. A dispute over which piano the great virtuoso Paderewski planned to use for his exhibition performances—soon known as the “piano war”—damaged Thomas's relationship with the fair's governing bodies early on.Footnote 43 His brusque manner and reluctance to issue any details about the music program led to frequent attacks by the Chicago press. The inadequate attendance for the symphony concerts and the resulting financial implications for the music program was the straw that broke the camel's back. Thomas finally resigned effective August 12, due to budget cuts that made it impossible to pay his exhibition orchestra.Footnote 44 In his resignation letter, excerpted in the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean, a humbled Thomas conceded that his plan had not worked:

For the remainder of The Fair, music shall not figure as an art at all, but be treated entirely on the basis of an amusement. More of this class of music is undoubtedly needed at The Fair, and the cheapest way to get it is to divide our two fine bands into two small ones for open-air concerts, and our exposition orchestra into two small orchestras, which can play such light selections as will please the shifting crowds in the buildings and amuse them.Footnote 45

Thomas would later comment in his autobiography on the hard lesson learned from his involvement with the United States’ two nineteenth-century world's fairs: “It proved then [in Philadelphia]—as it has since [in Chicago]—that people go to a World's Fair to see and not to hear, to be amused, not to be educated.”Footnote 46 Thomas had outlined an ambitious and idealistic program for the fair and years later he still chafed at not fulfilling his mission. George P. Upton continued to lament Thomas's unrealized series with his editorial comments in the conductor's autobiography, stating, “had he been enabled to carry it out according to his original design, [the symphony concerts] would have presented a summary of the progress of music during the last two or three centuries.”Footnote 47 Upton believed the few programs that Thomas had been able to perform demonstrated “the dignity and importance of the purpose he had in view.”Footnote 48 Thomas's and Upton's sympathies lay with “high-class” music, and they were disappointed that the hierarchical model had not worked. Perhaps if Thomas had curtailed his ambitions and focused on developing the “popular” orchestral model, things would have turned out differently.

Clarence Eddy and the Organ Program

Clarence Eddy's leadership of the organ concerts at the fair demonstrates a pragmatic approach that contrasts with Thomas's handling of the orchestral concerts. A respected member of the Chicago musical elite, Eddy was invited by Thomas to oversee the organ program at the fair, including designing an instrument for Festival Hall, and organizing a slate of performers from the United States and abroad.Footnote 49 As a member of the Bureau of Music, Eddy was familiar with the concept of progress and the goal of using music to edify audiences, but he was also eager to encourage a broader appreciation for organ music and a growing market for solo recitals. He hoped the prediction of Everett Truette, editor of the Boston-based monthly, The Organ, would hold true: “Thousands of people will visit the fair and see this organ who have never heard a concert piece played on an organ of any size, and good organ music will be a revelation to them.”Footnote 50 While Thomas concentrated on creating a product that would appeal to the musical elite, Eddy was less concerned with stratification and more focused on developing a wider audience for the instrument through varied programming.

By all accounts, Clarence Eddy was a consummate musician and accomplished organ virtuoso. Born in Greenfield, Massachusetts in 1851, he received early training with composer/organist Dudley Buck before heading off for the requisite “finishing” education abroad. Eddy spent the bulk of his two-year stint in Berlin studying piano with Carl Albert Löschhorn and organ with Carl August Haupt, an internationally recognized pedagogue who taught dozens of U.S. organists during his career. While in Europe, Eddy travelled extensively and began to develop a network of musicians that included William T. Best, Alexandre Guilmant, Charles-Marie Widor, Jules Massenet, Camille Saint-Saëns, César Franck, and Franz Liszt.Footnote 51 Throughout his career, he frequently championed the work of these acquaintances by performing United States premieres or providing editions for U.S. organists.Footnote 52

Upon his return to his home country in 1874, Eddy settled in Chicago and set about establishing himself as a church musician, pedagogue, chamber musician, and touring concert organist. During his nearly twenty-year stay in Chicago before moving to Paris, Eddy held positions as organist at the First Congregational Church and the First Presbyterian Church, taught at the Hershey School of Musical Art and the Chicago Conservatory of Music, served as consultant for a number of large new organ installations, and maintained a performing schedule that took him all over the Midwest and Northeast.Footnote 53 He developed his persona as a well-connected member of the Chicago musical elite by participating in musical societies such as the Apollo Club and the Wagner Club. He contributed regularly to discussions of pedagogy, programming, and organ building in numerous music journals during this period,Footnote 54 and he was recognized at home and abroad as a virtuosic performer with a formidable pedal technique and a vast repertoire.Footnote 55

Over the course of his career leading up to the Chicago Exposition, Eddy had begun to experiment with changes in organ concert programming. Secular organ concerts were a relatively new phenomenon in the United States in this period. In many ways, the 1863 dedication of a large organ built by the German firm E. F. Walcker Orgelbau for Boston Music Hall served as the catalyst for the establishment of the public organ concert in the United States.Footnote 56 In the decades following, construction of organs in concert halls and a more relaxed attitude to hosting concerts in houses of worship contributed to the rise of the public organ concert. Early concerts usually took the form of a mix of solo organ pieces and a few selections where the organ accompanied a vocal or instrumental soloist.Footnote 57 Eddy's 100 programs for the Hershey School in 1877–1879 fall into this category.Footnote 58 At Hershey, Eddy also experimented with themed programs with his 1881 set of “National Programs,” concerts in which he performed music by composers of one nationality.Footnote 59 However, by the late 1880s and early 1890s, Eddy had settled on a decidedly varied and accessible program model that featured a solo organist exclusively. The fair was an opportunity to share this programming philosophy with a wider audience.

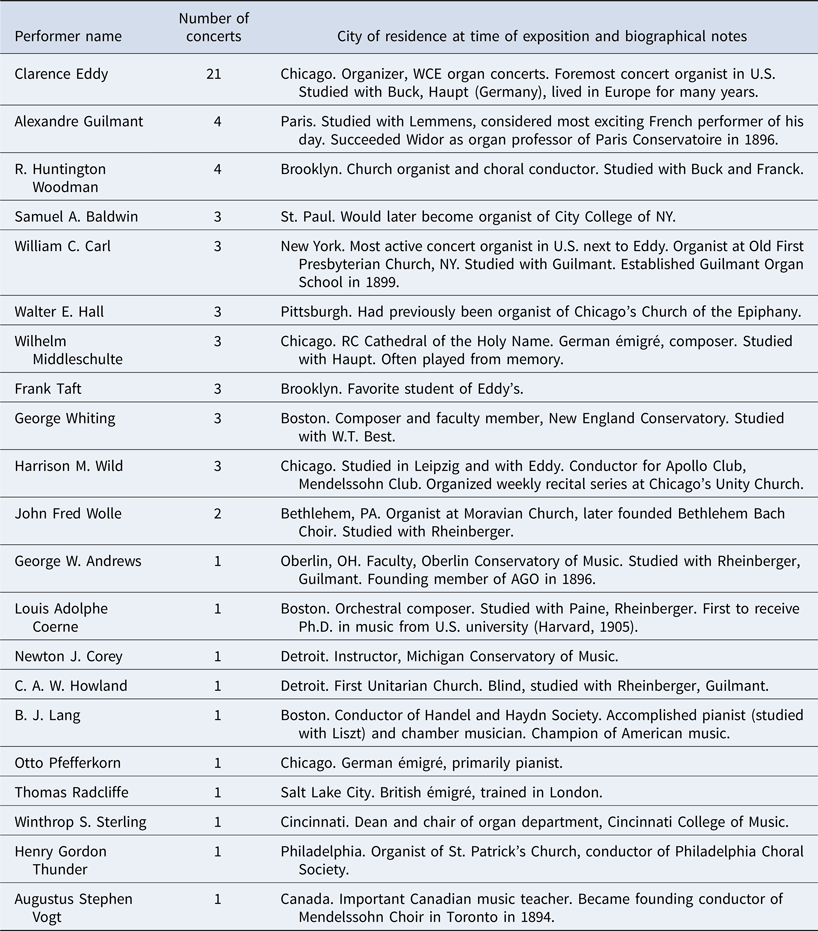

Although Eddy had a substantial repertoire and had demonstrated he was capable of marathon series, he decided to enlist colleagues in presenting the fair's organ concerts. His choice of performers reveals his programming philosophy as well as an underlying expectation for U.S. musicians. As with orchestral musicians in this period, European musical training of organists held a certain cachet. Fourteen of the twenty-one recitalists at the Exposition had received musical training in Germany, France, or England. For example, Clarence Eddy and the German émigré Wilhelm Middleschulte had studied with August Haupt in Berlin, R. Huntington Woodman with César Franck, B. J. Lang with Franz Liszt, and William C. Carl with Alexandre Guilmant (see the Appendix for a list of organ recitalists, their city of residence at the time of the exposition, and biographical notes).Footnote 60 In addition to featuring U.S. performers with European pedigree, Eddy sought to secure international names to headline the series and was ultimately successful in contracting one of the world's leading organists, the Frenchman Alexandre Guilmant.Footnote 61

We get an idea of why Eddy chose Guilmant from an 1896 article titled “Leading Organists of France and Italy” that Eddy wrote for the magazine, Music as a foreign correspondent in Paris. In Eddy's mind, Guilmant was a leader among organists:

As the head of the organist profession in Paris I place Guilmant, because he is more catholic in his taste, has a broader scope, plays in all schools, and is an organ virtuoso of the first rank….. He has done more for organ music than any one else in France, to popularize the instrument and bring it before the public.Footnote 62

When it came to securing a European star to headline the organ series at the fair, Eddy believed that Guilmant's “catholic taste,” virtuosity, and good-natured personality would have the most appeal among U.S. audiences. He was familiar with Guilmant's efforts to “popularize the instrument” in his home country and had hopes that he could do the same in the United States.

Although the performers and their choice of programming would be an important factor for the success of the organ series, the concerts had an additional draw: the exposition instrument. The four manual, sixty-three-stop organ built by Farrand & Votey Organ Company of Detroit was lauded as a mechanical and tonal masterpiece.Footnote 63 Months before the exposition opened, Farrand & Votey had been fortunate enough to receive the valuable patents, machinery, and craftsmen from the Roosevelt Organ Firm when the firm's president decided to retire.Footnote 64 Roosevelt's innovations assimilated into the Farrand & Votey instrument represented the cutting edge in organ building, making it easier to play virtuosic repertoire: electric action, pneumatic couplers, adjustable combination pistons, and a crescendo pedal.Footnote 65 The organ's tonal concept favored flue and reeds at unison (8′) pitch, which made it more suitable for concert repertoire and orchestral transcriptions than the average church instrument.Footnote 66 Plus, it was large! The instrument was designed not only as a solo instrument but was also meant to support performances with massed choirs and orchestras.Footnote 67 The exposition instrument represented the epitome of progress, innovation, and creativity in the United States. Whereas thirty years prior, Boston had looked to Europe for the highest craftsmanship and innovation in organ building for Boston Music Hall, now U.S. builders demonstrated first-class workmanship with the latest technology.Footnote 68

Eddy endeavored to build an audience for solo pipe organ concerts in the United States by featuring leading U.S. organists and a European headliner, a large instrument in a secular space, and a varied and “catholic” approach to concert programming. Judging by the reception in musical magazines of the day and the box office receipts, the series was a success. Honoraria for performers came in just under the $2,000 allotted in the music budget, and the box office receipts from the twenty-five cent admission price grossed a little over $6,700.Footnote 69 Thus, close to 27,000 people must have paid admission to hear these performances over the course of three months, while countless others probably attended with complimentary passes.Footnote 70 While the numbers only represent a small percentage of the overall general admission to the fair, news of the recitals reached a far wider audience via articles and reviews in major newspapers, music magazines, and organ periodicals.Footnote 71 Chicago's organ program was the first national large-scale recital series of varied performers that exclusively featured solo repertoire for the instrument and it furthered the rise of the solo organ recital in the United States. The discussion that follows presents an analytical examination of the sixty-two concert programs as a way to understand the driving factors behind programming at the fair and the particular way organists approached their audiences at this event.Footnote 72

More Popular than Profound?

It was amidst the firestorm leading up to Thomas's eventual resignation that the Farrand & Votey organ was finally ready for its unveiling. On July 31, Clarence Eddy inaugurated the instrument for an audience of 1,200–1,500 peopleFootnote 73 with the following program:

- Toccata in F Major

J. S. Bach

- Variations on “The Star Spangled Banner”

Dudley Buck

- “A Royal Procession”

Walter Spinney

- “Pilgrims’ Chorus”

Richard Wagner

- Funeral March and Seraphic Song

Alexandre Guilmant

- Offertory in C Minor (“Saint Cecilia”), Op. 7

Antoine Batiste

- Grand Fantasie in E Minor

Jacques Lemmens

- Overture to Oberon

Carl Maria van WeberFootnote 74

Newspapers from as far afield as Dallas, New York, and Wheeling, West Virginia ran articles describing the July 31 event and contemporary reviews highlighted its popular nature. A write-up in The American Art Journal noted that Eddy's first program “served two excellent purposes: first, to illustrate the strong points of the new instrument; secondly, to gratify a miscellaneous audience.”Footnote 75 A writer for The Presto wrote: “the program offered was a pleasing one, rather popular than profound, as organ programs generally are.”Footnote 76 Part of the reason for the more accessible approach on this first program was no doubt due to the “miscellaneous audience” that the new instrument was expected to attract in the huge hall. The following analysis of the repertoire shows that the organ programs, under the astute leadership of Clarence Eddy, on the whole embraced the idea of accessibility by offering a blend of “popular” and “profound.” Performers endeavored to bridge this binarism between edification and entertainment with their program choices and their performance practice. While Thomas tried to separate “artistic” and “popular” into two different halls with two different audiences, organists found a way to engage the miscellaneous audience and the connoisseur in the same program, sometimes within the same piece.

Categories of musical genres carried a “popular” or “artistic” connotation on organ concerts, just as they did in the orchestral world. Some programs had a higher percentage of pieces in “popular” categories, as in the opening program, but an analysis of the series on the whole reveals a balance between “popular” and “artistic” elements. The following discussion will focus on overall programming tendencies at the fair, namely the composers and nationalities featured, the genres represented, the number of original organ works versus transcriptions, the works’ dates of composition, and the inclusion of improvisations.

As was the case with most official concerts at the fair organized by the Bureau of Music, organ concerts exhibited a preference for the works of European composers. Given that the majority of the performers had studied in Europe, and given Americans’ tendency to look to Europe for cultural legitimacy, the breakdown does not come as a surprise. Nonetheless, organists eschewed the model of Thomas's symphony concerts at the fair—programs featuring music of primarily Austrian or German composers—instead opting for a more balanced sampling of national styles. Table 1 shows programs featured works by German composers most often, followed by the French at a close second, and those from the United States at a distant third. Fourth place went to England, fifth to Belgium, and Italy, Poland, Hungary, Norway, Denmark, Austria, The Netherlands, Denmark, Canada, and Alsace were each represented in small numbers. The proportion of French and U.S. composers on these programs more closely mirrors programming on Thomas's orchestral matinees.

Table 1. Frequency of pieces played, sorted by composers’ country of birth

*Unknown composers include entries for a “Communion” by an unlisted composer on program number 7 and a “Concert Fantasia” attributed to a “Leopold du Prins” on program number 14, nationality unknown.

The fact that U.S. composers fared as well as they did was related to the fair's mission to laud the United States’ progress in all areas. While organists believed in the superiority of the European masterworks and the necessity of European musical training, like Thomas, they wanted to recognize the achievements of native composers. The majority of them did this by including one or two works by U.S. composers on a varied program, similar to the “popular” orchestral matinees. Some of the pieces performed most frequently were those based on familiar tunes, such as Dudley Buck's variation sets on “The Star-Spangled Banner” and “The Last Rose of Summer.” One notable exception to this trend was Chicago's Harrison M. Wild, who performed a program devoted exclusively to U.S. composers:Footnote 77

- Triumphal March

Dudley Buck

- Allegretto, Op. 29, No. 2

Arthur Foote

- a. Romanza, Op. 17, No. 3

Horatio Parker

- b. Scherzo, Op. 32, No. 3

- Processional March

Samuel B. Whitney

- “Vorspiel” to Otho Visconti

Frederic Gleason, arr. Clarence Eddy

- Concert Variations on an American Air

Isaac Flagler

- Pastorale

George E. Whiting

- Serenade

Harry Rowe Shelley

- An Autumn Sketch

John Hyatt Brewer

- Fugue on “Hail Columbia,” Op. 22

Dudley Buck

This program was the only organ program that featured composers of a single nationality. The only other program that embraced the theme model was Frederick Wolle's all-Bach program on October 13, 1893.Footnote 78

Table 2 lists composers according to the frequency with which their works appeared on fair programs. The top three composers—Bach, Guilmant, and Buck—represent the top three countries represented. The pride of place afforded Bach on these programs is a testament to the efforts of nineteenth-century Bach-devotees such as Mendelssohn, Liszt, Widor, and Guilmant. By the end of the nineteenth century, Bach's organ works were widely available in modern editions and concerted efforts to increase the level of organ playing in Europe and the United States had produced performers who were ready to tackle these difficult works. Bach's organ works with obbligato pedal offered performers a chance to prove their mettle. The virtuosic element could fascinate a broad audience while the trained listener could appreciate the masterful counterpoint. As early as 1831, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy had reflected on the broad appeal of Bach organ works in a letter to his teacher, Carl Friedrich Zelter. In a visit to an organ loft in Weimar, the host organist asked him if he wanted to hear “something learned or something for the people (because he said that for the people one had to compose only easy and bad music).” After listening to the organist play “something learned” that was “not much to be proud of,” Mendelssohn got on the bench and “let loose with the D-minor toccata of Sebastian [Bach] and remarked that this was at the same time learned and something for the people, too, at least some of them.”Footnote 79 Even in the early stages of the Bach revival, performers recognized the appeal of Bach's organ works for a broad range of listeners.

Table 2. Composers represented most frequently (top 35)

That so many organ works could be considered on some level both “popular” and “profound” makes it difficult to determine how much of a program fell into each of these categories. However, sorting according to genre does offer some insights into programming trends. For example, fugues by Bach appeared on more than half of all organ programs at the fair. Most of these instances were the 30 performances of prelude and fugue, toccata and fugue, or fantasy and fugue pairs, but organists also played Bach fugues as stand-alone pieces eight times.Footnote 80 The frequent appearance of fugues shows organists embracing a “serious” genre with a long association with their instrument. Even Thomas did not go as far as programming fugues on his symphony programs.

Concertos or movements of concertos arranged for solo organ appear ten times. Nine of these came from the collection of Handel organ concertos. The other instance was a Concerto for Organ and Orchestra by Adolph Coerne that the U.S. composer adopted for solo organ after the Exposition Orchestra disbanded and the original premiere was no longer possible. Organ sonatas also featured prominently on programs; whole sonatas or movements appear forty-three times (see Table 3). Organists performed movements of symphonies thirteen times. Six of these instances were transcriptions of Beethoven symphony movements and seven were movements from solo organ symphonies by Charles-Marie Widor.

Table 3. Sonatas or sonata movements performed at the exposition

Note: The last four official programs are numbered 59, 59A, 60 and 61. This paper and database follow Friesen's numbering, with the last four using numbers 59, 60, 61, and 62.

Organists seemed comfortable programming purely instrumental genres: preludes, fugues, fantasies, sonatas, and symphonies with no formal associations with vocal, dance, or church music. This body of repertoire makes up close to forty percent of the total pieces performed at the fair (192 pieces of the total 505, see Table 4). Bach was well represented in this category. Fifty-six of the sixty-two programs included at least one example of a Bach “free” work—a prelude, toccata, fantasy, or fugue not based on a chorale melody—or at least one movement from a sonata. Thirty-seven of these programs had more than one example of these genres.

Table 4. List of instrumental genres performed at the exposition

However, pieces with extra-musical associations made up the majority of pieces on the organ programs. For instance, there were sixty-four marches of all stripes: funeral, pontifical, religious, wedding, coronation, processional, regal, for Schiller, of the magi, priests, crusaders, peasants, and so on. Pastorales appeared twenty-five times, including three performances of Rheinberger's Pastoral Sonata, op. 88, another example of a piece that straddles the two categories of “popular” and “artistic.” Performers favored these pieces with extramusical associations because they provided listeners with context or narrative. Many works by French composers bore titles such as Offertoire, Communion, Elevation, Benediction, Sortie, and Meditation that related to their alternate function as music appropriate for the Roman Catholic liturgy. French organ music in this period tended to be harmonically conservative, which probably had something to do with its liturgical connection as well as its reliance on elements of color and texture for impact. Both of these factors made them easier for the novice listener to digest. Funeral and wedding music abounded, as did Christmas music, and variation sets on familiar tunes. While the frequent appearance of fugues and sonatas on almost every program pointed to organists’ willingness to include serious genres, the abundance and variety of genres with extra-musical associations showed they also embraced accessible repertoire.

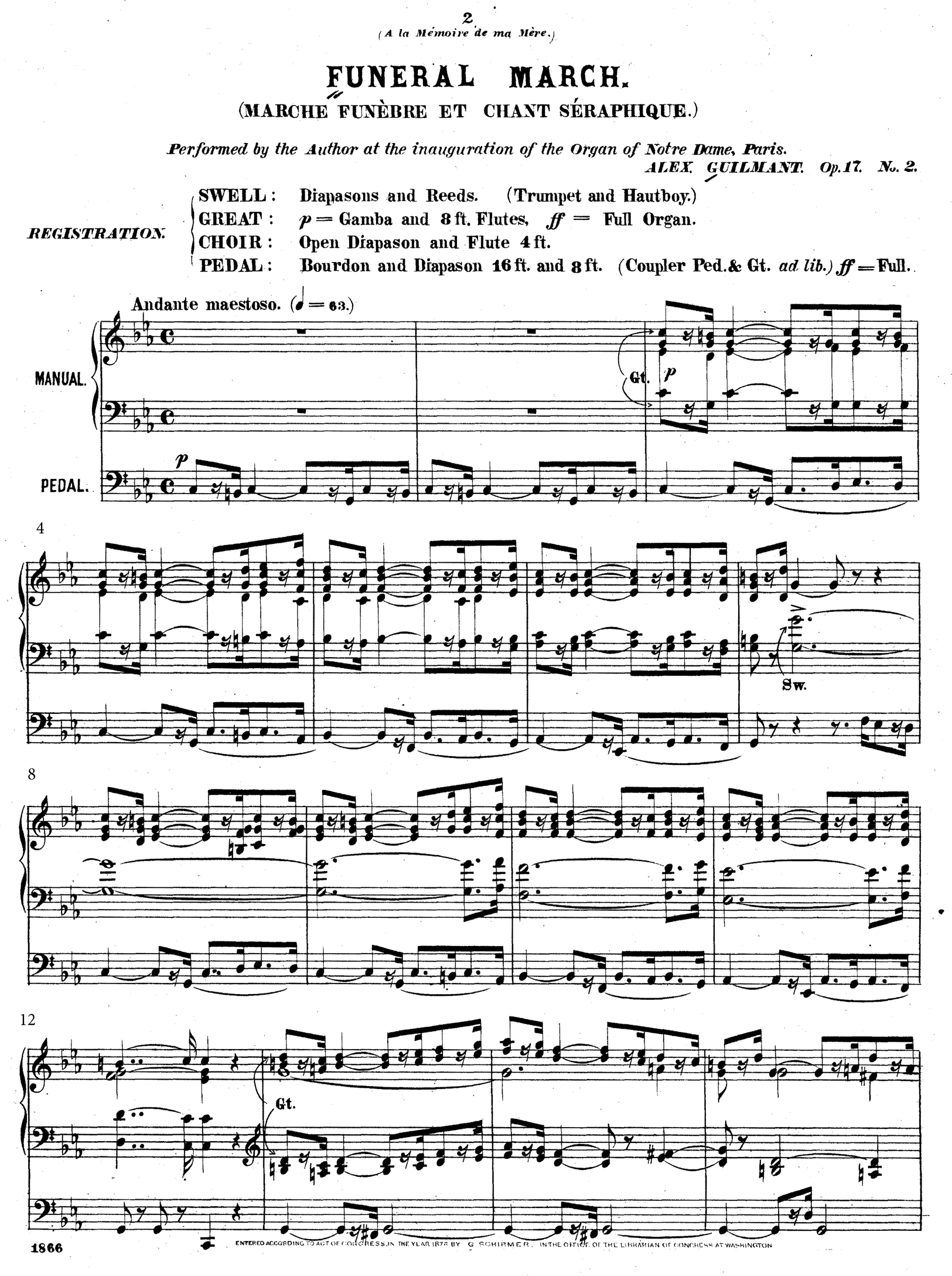

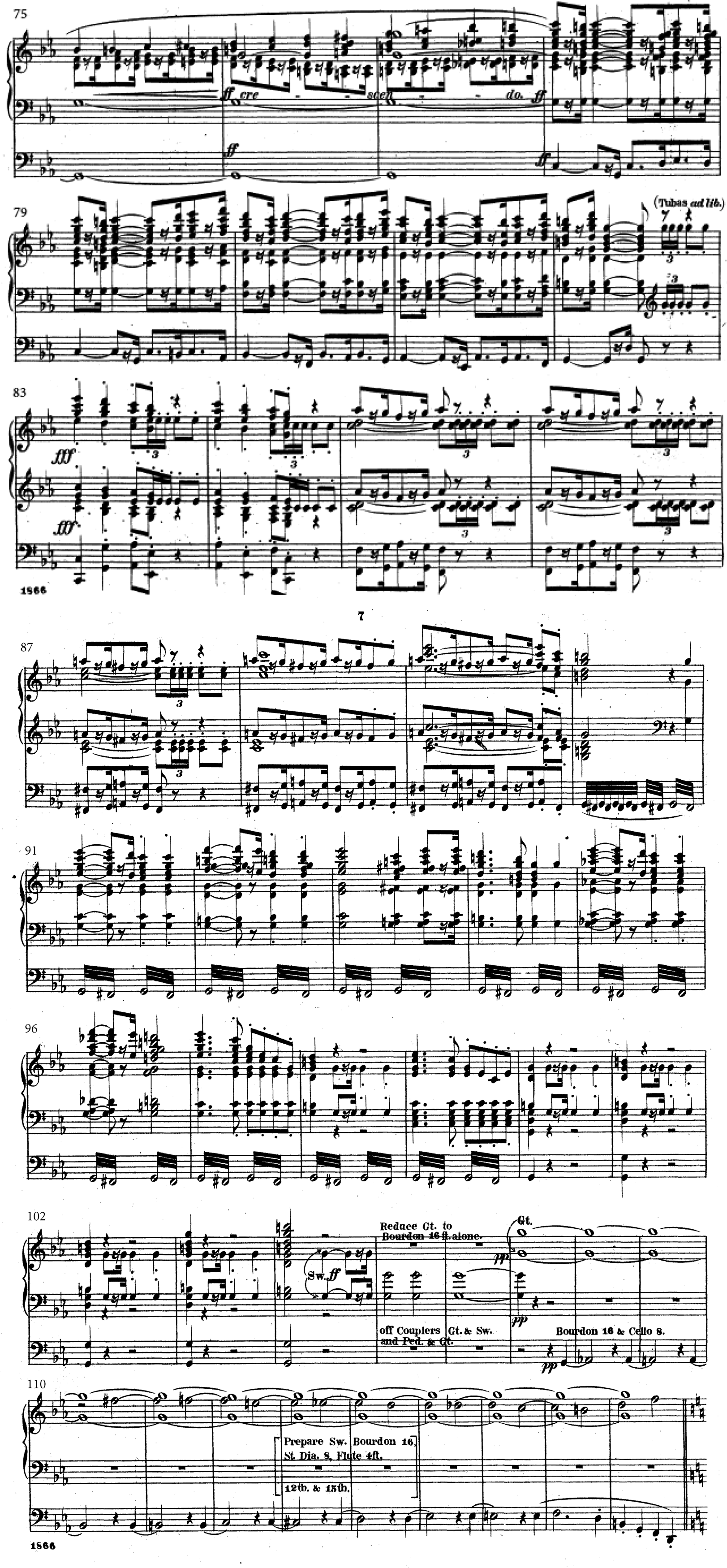

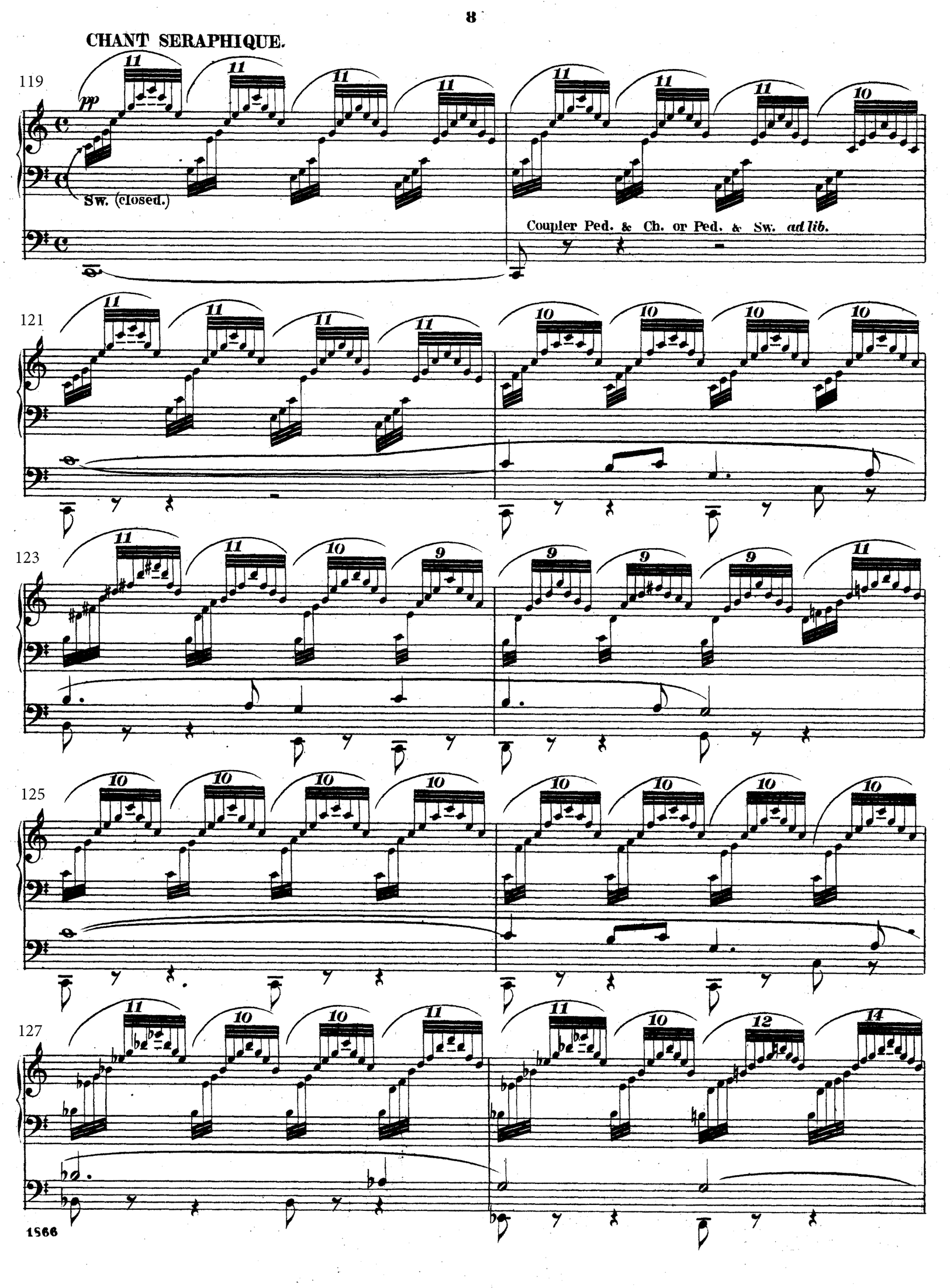

A good example of this type of accessible work is Guilmant's “Funeral March and Hymn of Seraphs” (“Marche Funèbre et Chant Séraphique,” Op. 17, No. 3). This piece was performed five times by five different artists, including the composer himself.Footnote 81 One of the elements that would have made this piece appealing to the miscellaneous audience at the fair was its programmatic connection. Chopin's Funeral March from Sonata No. 2 in B flat Minor was tremendously popular in this period, and Guilmant borrows the march-trio format for his piece. Guilmant's Funeral March presents two clear themes: a slow dotted march rhythm that opens the piece, and a second sustained melody on the trumpet stop that accompanies the opening theme beginning in measure 7 (Example 1). The melody assigned to the dotted rhythm is diatonic, easy to hum, harmonized with parallel thirds, and repeated often. In addition to having clear, memorable melodies, the piece lends itself to a large organ with a wide range of timbres and dynamics. For instance, the trio calls for constant dialogues between the Hautbois of the Swell, the flues on the Great, and the Diapason on the Choir (measures 54–57, Example 2). A dramatic crescendo to tutti in measures 75–104 and octaves played on a solo Tuba stop provide excitement and an opportunity to show off the power of the instrument (Example 3). The soft pianistic arpeggios over a sustained lyrical melody in the pedal for the concluding “hymn of the seraphs” (measure 119 to the end) are an opportunity to highlight the virtuosity of the performer (Example 4). The clear formal structure and expert use of the tonal resources of the organ would earn it praise from the musically savvy, while the extramusical association, clearly defined rhythms, singable melodies, conservative harmony, and dramatic use of dynamics would keep the attention of a less-learned audience.Footnote 82 The piece is a prime example of how nineteenth-century French organist-composers skillfully manipulated the organ's ability to effect contrasts in timbre, dynamics, and texture. All of these features combined to create a piece that both connoisseurs and novice listeners appreciated and enjoyed.Footnote 83

Example 1. Alexandre Guilmant, Funeral March, measures 1–15.

Example 2. Alexandre Guilmant, Funeral March, measures 51–59.

Example 3. Alexandre Guilmant, Funeral March, measures 75–118.

Example 4. Alexandre Guilmant, Funeral March, measures 119–28.

Organ transcriptions of works for other instruments were another important body of repertoire at the fair, making up ninety-seven of the total 505 pieces.Footnote 84 Some of the more conservative contemporary critics, such as Everette Truette, the editor of the Boston-based monthly, The Organ, believed this repertoire was inferior to “legitimate” original works for organ and dismissed it as overly “popular.”Footnote 85 But, like Bach's preludes and fugues, this repertoire blurred the lines of “popular” and “profound.” On the one hand, transcriptions were considered “popular” because they offered a chance to present familiar works, such as Rossini's Overture to William Tell and Chopin's Funeral March from his Piano Sonata in B Minor (two pieces that also appeared on Thomas's “popular” orchestral series, including Thomas's own arrangement of the Chopin). Many of these pieces were arrangements of operatic works, such as Wagner overtures or scenes, and therefore connected to a narrative. In addition, when presented in a transcription, the performer's skill in orchestration offered an added level of interest for the average concertgoer. Part of the thrill was hearing how a single performer could take the place of a multi-voice orchestra. A large organ at the hands of a skillful orchestrator could rival the timbral and dynamic capabilities of an orchestra. In this respect, transcriptions were crowd pleasers. On the other hand, transcriptions offered organists a chance to provide substantive masterworks from the orchestral repertoire. Organ concerts embraced the dual function transcriptions of these pieces carried, allowing the performer to present the “popular” and “profound” within a single piece.

With a handful of exceptions, the most notable being Bach, organ music at the fair featured living composers or those who had died within the last fifty years. Fourteen of the sixty-two programs list at least one work as being “new” or in manuscript copy. Additionally, fourteen programs announce that the composer has dedicated this or that work to the performer. William C. Carl was one performer who took special pains to seek out new works and list them as such in his programs. The program from August 7, 1893 noted that Carl was the dedicatee for two of the eight pieces: “Noel” by Théodore Dubois and “Allegretto” by Theodore Salomé. “Noel” is listed as “new.” Carl's request to Chicago composer Frederick Grant Gleason from 1891 for a new piece for a program of U.S. music shows the performer actively seeking out new repertoire.Footnote 86 This close relationship between composer and performer contributed to the frequency of contemporary pieces on organ concerts. Another reason for this phenomenon is that nineteenth-century organists were trained as improvisors and composers. In the French tradition, the organ class was an extension of the composition curriculum, rather than part of a separate performance-based curriculum.Footnote 87 While both the symphony and “popular” orchestral programs made an effort to feature contemporary works, the large number of performer-composers represented on the organ programs was a trend unique to organ concerts at the fair.

Organists also included a higher percentage of pre-nineteenth-century music on their programs, compared to either of the orchestral series. As we have seen, works of Bach were important staples on the organ programs. By and large, organists tended to opt for the more accessible or virtuosic part of Bach's oeuvre (see Table 5 for a list of Bach works performed at the fair). The fact that the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor was the most popular Bach work (and in fact, the most frequently performed work at the fair overall) exemplifies this tendency. Organists chose to share the loud and extroverted toccatas and fantasias and the virtuosic “Spiel” or “Gigue” fugues rather than the slower “Alla Breve” or “Art” fugues.Footnote 88 Organists rarely shared chorale preludes or trio sonatas, which called for softer registrations and (for the chorale preludes) an audience's familiarity with Lutheran chorale tunes. The sheer power of the full organ called for in the “free” works impressed audiences, whereas an ornamented chorale tune would be lost on most listeners.

Table 5. Works by Johann Sebastian Bach performed at the exposition

Organists seemed committed to Bach and Handel, but only rarely did they perform music from earlier periods. The only pre-Bach works performed at the fair were two pieces by Dieterich Buxtehude, the Fugue in C Major and Ciacona in E Minor, played by Guilmant; “Choral” by Samuel Scheidt, played by Coerne; and a Trio attributed to Giovanni Pierluigi de Palestrina, played by Taft. Notably, Guilmant chose to play Buxtehude's sprightly “Gigue” Fugue and a variation set on a ground bass rather than any of the multi-sectional praeludia. This was not to say that performers did not have earlier pieces in their repertoire. By examining his Hershey School programs, we know that Eddy had the praeludia of Buxtehude, toccatas of Girolamo Frescobaldi, and trio sonatas and chorale preludes of Bach in his repertoire.Footnote 89 For his part, Guilmant had distinguished himself as an early-music pioneer in France with his Historical Organ Concert Series at the Trocadéro in 1889 and the subsequent edition of the works he performed on these recitals.Footnote 90 In 1893 he had already begun issuing a twenty-five volume set of early music from the French, German, Austrian, and Italian traditions called École Classique de L'orgue. However, both Eddy and Guilmant knew their role at the fair was to engage a broad audience, and as a result, they curtailed their performances of early music.

When they did play early music, organists at the fair updated these works for contemporary audiences by subjecting them to modern performance practice. Pre-nineteenth century composers rarely included registration indications in their works, relying on shared practice and a close relationship with a particular instrument type to lead the performer in these choices. A handful of the Bach works carried the designation “organo pleno,” to indicate full organ registration, and terraced dynamic indications and manual changes exist in his Prelude in E-flat and Dorian Toccata, respectively, but the majority of the manuscript copies leave registration up to the performer. The absence of registration information invited multiple solutions as performers reengaged with these works in the mid- and late nineteenth century. For example, the manuscript copy of Buxtehude's Fugue in C Major that Guilmant played at the fair carries no registration indications, but a published edition by the performer gives us a clue as to how he might have orchestrated this piece at the event. In an 1898 collection put together by his student William Carl, Guilmant's registration markings for this piece prescribe a gradual crescendo alternately opening swell boxes and adding specific registers on a three-manual organ.Footnote 91 Registering a fugue to build to a crescendo was a favorite nineteenth-century technique, as was orchestrating these contrapuntal works in such a way that the average listener could easily hear subject entries and structural points. The noted pianist and pedagogue Emil Liebling, in his account of the organ concerts at the fair in the magazine Music, highlighted this practice: “Mr. [Harrison] Wild displayed considerable orchestral sense in the manner by which the different entrances of the theme [of Bach's Fantasie and Fugue in G Minor] were introduced.”Footnote 92

Organists of the period also used a new legato technique, with the full integration of heel and toe pedal playing, to recast older works in a modern light. The new electric actions were much lighter than traditional mechanical key and pedal actions, making it easier to play legato at quicker tempos. Eddy, in a written response to a paper on organ pedaling given by Gerrit Smith at the 1892 Music Teacher's National Association, provides insight as to how he and others approached old music from a performance practice standpoint:

An absolutely free and independent use of the heel in pedal playing is seldom found, and yet it is as important as a skillful employment of the thumb upon the manuals. The old school said avoid using the heels; but the new school says, use every means to obtain artistic results.Footnote 93

This motto, “use every means to obtain artistic results,” reflected nineteenth-century performers’ belief in the progression of performance practice. By opting for registrations for modern organs and legato technique, they felt they were updating the old works, giving them a better chance for understanding among modern audiences.

One feature of organ programming that had no parallel in the orchestral program at the fair was the presence of improvisations. There were six instances of improvisations at the World's Columbian Exposition: Guilmant included improvisations on each of his four programs, and the U.S. performers B. J. Lang and Winthrop Sterling included one each.Footnote 94 In France, organ inaugurations always included improvisations because they were the best vehicle for displaying the features of the new instrument. As a representative of the French school of organ playing, Guilmant saw fit to uphold his country's traditions by improvising on a new exposition instrument. Improvisations also offered a special opportunity to engage an audience because an organist could tailor their performance to the particular time, place, instrument, and context. Guilmant's choice of themes shows he viewed his improvisations as a way to connect with the audiences at the fair. He opted for secular themes on popular U.S. and French tunes—”Hail Columbia,” “Suwanee River,” “Marseillaise Hymn,” and “John Brown's Body”—that would be familiar to his U.S. audience.Footnote 95 One contemporary reviewer was especially impressed with Guilmant's treatment of the chosen themes, commenting that the performance “took a wide range, and readiness of resource no less than musical phantasy were evident all through.”Footnote 96 Another reviewer remarked that Guilmant's improvisations were “both spontaneous and scholarly.”Footnote 97 Through his improvisations, Guilmant was able to connect with his audience using familiar themes while simultaneously impressing fellow organists and musicians by demonstrating his skill at invention and demonstrating composition in the moment.

The analysis above shows organists at the fair embracing an accessible programming model. The variety of composers featured, the high frequency of pieces with extra-musical associations, and the inclusion of transcriptions mirrored programming on the “popular” orchestral matinees. However, the high percentage of organ fugues, sonatas, concertos and symphonies suggests that these programs also aimed to engage the serious listener and fellow organist. Influential music critics praised the organ concerts as having represented high artistic standards, filling the void left by the Thomas orchestra. At the close of the fair, Mathews wrote in Music, “The place of honor must be given to the organ programmes, which have been important in themselves, as illustrations of all schools in this department, and by reason of the eminence of the artists who have co-operated in them.”Footnote 98 Truette used his column in the January 1894 edition of The Organ to praise the “taste of our organists” for championing original compositions for organ on their programs as opposed to transcriptions. He also made a point of listing the number of performances of Bach works, and the number of sonatas and fugues that appeared on the programs.Footnote 99 Both of these members of the musical elite saw the organ concerts as representing a high-quality cultural product worth extolling. That organists were able to please influential critics like Mathews and Truette while also appealing to the fair's “miscellaneous audiences” speaks to their pragmatism and willingness to cast a wide net. No doubt their approach was a major reason why the concerts were successful on the whole.

Reinforcing the Trends

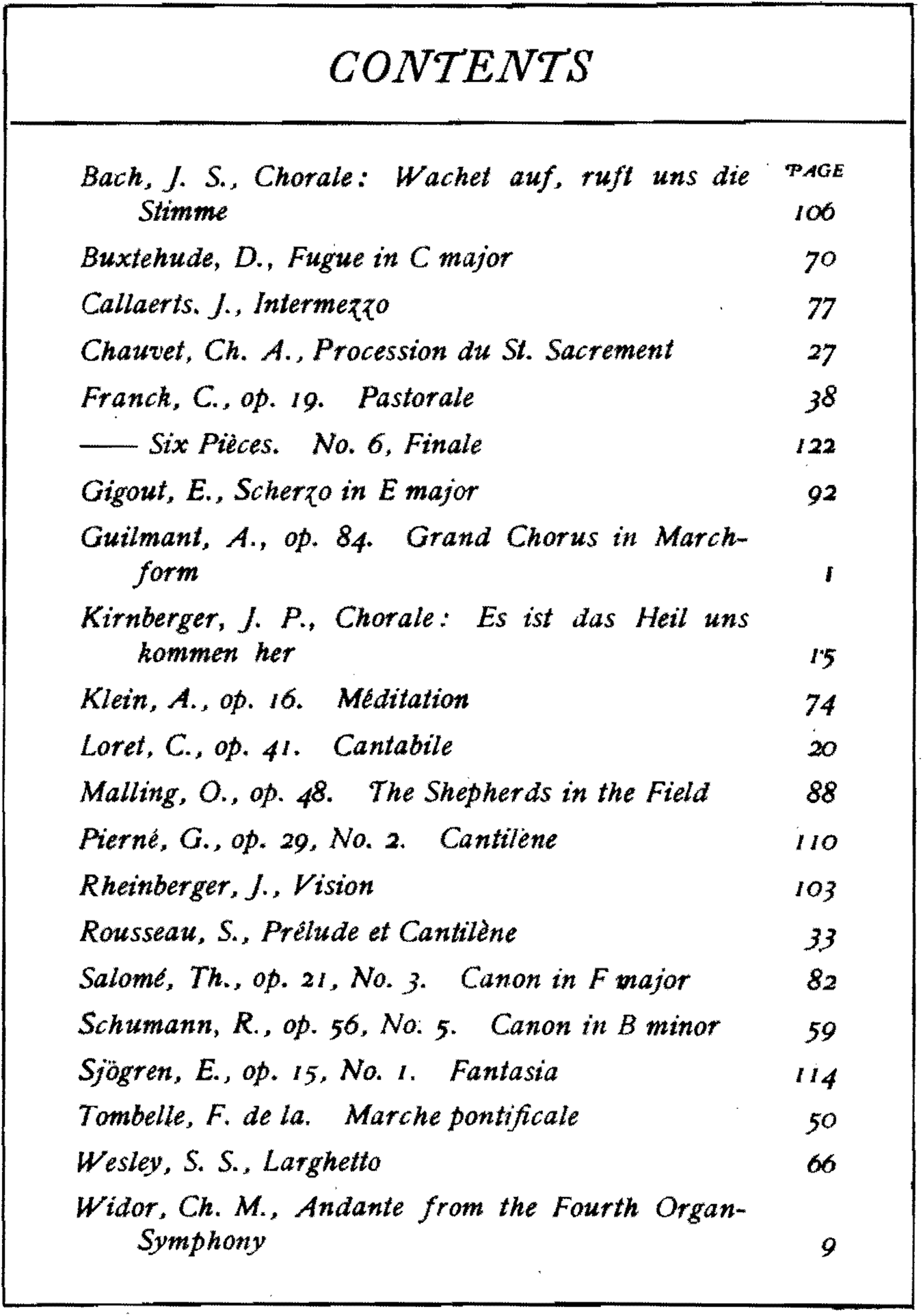

After the close of the fair, organists shared resources that reflected the success of the approach to organ concert programming at the fair. Two published collections by performers at the fair, one by Carl and one by Eddy, both demonstrated and reinforced this model. Published in 1898, Carl's volume, Masterpieces for the Organ: A Collection of Twenty-one Organ-works, Selected Chiefly from the Programs of Alexandre Guilmant, capitalized on his teacher's successful United States debut in 1893 and subsequent concert tour of 1898 (see Figure 1). Carl's preface clearly outlines the function of the anthology: “In compiling this Collection of Original Organ pieces, I have endeavored to bring together those which will especially serve for Recitals and Concert-work.”Footnote 100 Like Guilmant, who famously wrote in 1898, “I am utterly opposed to the playing of orchestral works on the organ,”Footnote 101 Carl believed in the appropriateness of original organ music over transcriptions. The table of contents (see Figure 2) lists many of the same composers that were frequently performed at the fair, the majority of them French. It also reflected the attitude of both Carl and Guilmant about what constituted suitable concert repertoire.

Figure 1. Title page from William Carl's edited volume, Masterpieces for the Organ: A Collection of Twenty-one Organ-works, Selected Chiefly from the Programs of Alexandre Guilmant.

Figure 2. Table of Contents from William Carl's edited volume, Masterpiecs for the Organ: A Collection of Twenty-one Organ-works, Selected Chiefly from the Programs of Alexandre Guilmant.

Eddy also used his own editions to promote a slightly different philosophy of concert programming. He published a four-volume set between the years 1881 and 1909 titled The Church and Concert Organist: A Collection of Pieces with Registration, Fingering and Pedal Marking; Adapted for Church and Concert Use. Schuberth & Co., the publisher of Eddy's anthologies, issued a promotional booklet to coincide with the release of the 1909 volume. In the preface to this pamphlet, Twenty-five Organ Recital Programs by Clarence Eddy, the respected performer shared his approach toward programming for a larger audience:

These programmes have been carefully selected and arranged with special regard to effective contrasts and progressive interest, the intention being to combine some of the most pleasing and grateful works by the old masters with the best of modern compositions for the organ.

Each programme should occupy about one hour and a half, and it is the hope of the arranger that they will prove of value, and possibly serve as a guide to his fellow organists.Footnote 102

All but one of the twenty-five programs feature a free work by Johann Sebastian Bach and eight to ten pieces by mid- to late-nineteenth-century composers from a variety of nationalities. A quarter of the pieces are transcriptions, most of them arranged by Eddy himself.Footnote 103 They thus mirror the programming model he established at the fair. Eddy's volumes were reissued numerous times throughout the twentieth century, proving that organists continued to accept and promulgate his philosophy and tastes long after the fair was over.

The World's Fair at Chicago and the publications that had stemmed from it provided the benchmark for organ programming in the decades that followed. Organizers at subsequent expositions in the United States adopted the organ concert series and programming models Eddy established in Chicago with great success.Footnote 104 Eddy himself was invited to perform at multiple expositions in the early 1900s and Guilmant returned to perform forty recitals at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904.Footnote 105 As the new century got underway, organ concerts had become a staple of musical life in the United States and it was not uncommon for virtuoso organists to draw audiences in the thousands.Footnote 106 As the new century opened, solo organ recitals and touring virtuosos became more and more common and, as a result, choices about concert repertoire became a focal topic. Organists of all persuasions shared philosophies on what constituted a good organ program, prompting a lively debate on the merits of transcriptions versus original organ works in music trade journals such as The Etude, The Musical Courier, and The Diapason in the early twentieth century.Footnote 107 At the close of Eddy's career, concert organists began to push their audiences toward a more serious product, mirroring the shift Theodore Thomas had initiated in the symphony concerts at the fair.Footnote 108 Nevertheless, the desire to entertain has remained an undeniable aim of the U.S. concert organist and can be counted as one of the myriad legacies of the World's Columbian Exposition.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196322000013.

Appendix

Organ Recitalists at the World's Columbian Exposition