Many China watchers maintain that Xi Jinping 习近平 has concentrated power in his own hands in a manner unprecedented since the death of Mao Zedong 毛泽东 and Deng Xiaoping 邓小平. Evidence of this includes Xi installing himself as the head of various central leading groups and commissions, his designation as “core leader,” his eponymous ideology inserted into the Party Constitution, his domination of the military, his prominent position in media coverage, the end of term limits that could apply to him and his massive anti-corruption drive.Footnote 1 Other scholars argue, however, that rather than establishing “one-man rule,” Xi maintains a system of collective leadership based on factional power balancing, which has prevailed throughout the reform era.Footnote 2 This article assesses whether Xi's purported consolidation of power is visible in factional politics by examining the strength of his faction in comparison with those of his two immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin 江泽民 and Hu Jintao 胡锦涛.

For top Chinese leaders, informal connections with supporters are a source of power at least as important as their formal positions.Footnote 3 Official positions are insufficient to guarantee power for top leaders, as witnessed with the downfall of three heads of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the post-Mao era, Hua Guofeng 华国锋, Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 and Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳. Post-revolutionary leaders who lack charismatic authority need to rely on informal networks of followers. The introduction of a retirement age and term limits marked progress towards institutionalization.Footnote 4 Yet the extent to which institutionalization trumps informal power appears limited, as was made clear by Xi's 2018 abolition of a term limit for his own position.Footnote 5 The rules for appointing personnel remain obscure, especially at higher levels, and this under-institutionalization of personnel appointments gives top Chinese leaders many opportunities to promote clients. Thus, Lucian Pye's 40-year-old observation that “personal appointments are pure power questions, and as such they represent the final outcome of all factional conflicts” is still valid, at least for high-level positions.Footnote 6

We investigate Xi's power by examining the strength of his faction in comparison to those of his two immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. The incumbent head of the CCP has the influence to place supporters in high-ranked positions and promote them to even higher positions. However, this influence could be checked within the Party by blocking the appointment of some of his clients and balancing his appointments with those of members of other factions. Recent history has shown that the most likely check on the power of the current head of the Party would come from a faction connected to a retired Party head who could exert influence, especially through his clients in the Standing Committee of the Politburo. We measure the strength of a faction by its share of positions in the top four ranks of the party-state, including the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the Politburo, provincial Party secretaries and provincial governors. Further, we investigate whether a dominant faction is emerging under Xi Jinping, replacing the power balance between factions from the Hu and Jiang eras.

The number of faction members in high-ranked positions is both a signal and source of factional power. Thus, the head of the CCP would want to promote as many of his own clients as possible. Empirically, studies have verified this by finding that factional ties to Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao had positive effects on provincial leaders’ chances of promotion.Footnote 7 But while the head of the CCP is likely to exert influence on personnel decisions, his ability to do so would vary depending on the strength of his faction relative to rivals. Success in factional promotion should be self-reinforcing: the more a leader promotes members of his own faction, the stronger his position will be to do so in the future. If Xi Jinping, less constrained by rival factions or individuals, was able to bestow significantly larger advantages to his trusted favourites, compared with Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, this would both demonstrate and reinforce the dominance of his faction. Our statistical analysis of provincial leaders’ chances for promotion from 1989 to 2018 finds that Xi's clients, in comparison to those of Jiang and Hu, had greater chances for promotion.

This article broadens the understanding of Chinese elite politics in several ways. First, whereas previous studies view factional politics through the lens of power balancing, we propose an alternative model: a dominant faction.Footnote 8 This theoretical and empirical innovation is needed because Xi Jinping's dominance seems to have ushered in a new era in Chinese politics, not just in terms of factions or elite politics but across Chinese domestic politics and in many areas beyond.

Second, existing studies of factional configurations during the Xi Jinping era are generally confined to analysis of top leadership positions. Considering that power is concentrated at the very top in Chinese politics, the importance of these studies cannot be exaggerated. However, owing to the small number of top leadership positions, scholars interpret the distribution of factional power differently. Of the seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee in the 19th Party Congress, three are in Xi's camp (Xi Jinping, Li Zhanshu 栗战书 and Zhao Leji 赵乐际), two belong to the Chinese Youth League (CYL) faction headed by Hu Jintao (Li Keqiang 李克强 and Wang Yang 汪洋), one belongs to the Shanghai faction headed by Jiang Zemin (Han Zheng 韩正), and one is not part of any faction (Wang Huning 王沪宁).Footnote 9 While Young Nam Cho considers this to be a power balance among different factions, Joseph Fewsmith argues that it reveals the dominance of Xi's faction.Footnote 10 If we confine our analysis to this level, it is difficult to resolve the debate. By incorporating factional affiliations of Politburo members and provincial leaders, we demonstrate that Xi Jinping has been more successful at strengthening his factional base than Jiang and Hu.

Third, in a separate line of research, scholars have investigated whether the promotional prospects of provincial leaders are affected by factional connections or by economic performance. Findings are mixed: some conclude that economic performance matters for promotion,Footnote 11 whereas others show that only political connections are significant.Footnote 12 Still others find that both political connections and economic performance are essential.Footnote 13 Our study suggests that the importance of factional connections for the promotion of provincial leaders could depend on the power of their faction relative to rival factions. If a faction is less constrained by a strong rival faction or figures, then membership is likely to bestow a greater advantage in terms of promotion.

A Power Balance versus a Dominant Faction

Dennis Belloni and Frank Beller define a faction as “any relatively organized group that exists within the context of some other group and which (as a political faction) competes with rivals for power advantages within the larger group of which it is a part.”Footnote 14 They provide three ideal types of factions, depending on the extent of institutionalization and the importance of horizontal and vertical ties. The first type, a factional clique, forms to pursue a single issue. In these groups, recruitment is ad hoc and leadership is based upon charisma, rather than clientelist ties. The second type, a personalized faction, is based upon clientelism and consists of followers of a prominent leader. In these factions, a leader of a faction plays a crucial role in recruiting factional members, and chains of command are vertical. For this factional type, the importance of horizontal networks among followers is minimal. The final type, an institutionalized faction, develops organizations and recruits members on a non-personal basis. Horizontal networks among members are essential and factional members share a common identity.Footnote 15

The CCP bans the formation of factions within the Party so CCP members are not able to form institutionalized factions. Additionally, factional cliques do not usually form to pursue a single issue. We therefore investigate personalized factions, which, at the top of Chinese politics, are generally led by heads or former heads of the CCP. Personalized factions are based on patron-client relationships, which involve four core attributes: interest exchange, longevity, face-to-face contact and power inequality.Footnote 16 In other words, patron-client relations entail interest exchange between individuals with unequal power who have known each other for a long time through face-to-face contact. While patronage and clientelism are often used interchangeably, patronage entails an additional attribute, the “discretionary distribution of public office” to one's clients.Footnote 17

Some scholars have disputed how useful the concept of factions is for understanding Chinese politics. Sceptics provide two justifications. First, Frederick Teiwes claims that “the utility of the concept of ‘factionalism’ is limited” because objective criteria such as age, qualifications and tenure have gained importance in personnel decisions.Footnote 18 It is undeniable that these factors also play an important role in determining promotions in the upper echelons of the CCP. However, given that there are far fewer positions than officials who could be promoted to occupy them, especially at the highest levels, there is still tremendous variation among who might be promoted. From 1989 to 2018, for example, only 21 per cent of officials serving as provincial Party secretaries were promoted above that level. Additionally, our findings outlined in the subsequent sections corroborate past findings that factional ties play a crucial role in determining the chance for promotion of provincial leaders, even controlling for age, qualifications, performance and tenure. Our study, therefore, empirically verifies the importance of factions in Chinese politics.

Second, sceptics contend that factions are a constant and therefore too static to illuminate changes in Chinese elite politics. Indeed, scholars have applied factional models to Chinese politics since the era of Mao Zedong.Footnote 19 Why, then, are factions endemic in Chinese elite politics? Lucian Pye attributes the reason to Chinese cultural traits of relying on superiors.Footnote 20 On the other hand, Jing Huang claims that a single-party system breeds factionalism because competing groups do not have an exit option to create a new party.Footnote 21 The ongoing influence of culture and the one-party system, therefore, mean that factions continue to be relevant to Chinese elite politics. While the existence of factions within the CCP is a relative constant, however, power configurations among factions may change in important ways that help us to understand corresponding changes to Chinese politics more broadly, as our study demonstrates.

Existing studies on factional politics suggest that factions tend to form a balance of power.Footnote 22 Building a deductive model, Andrew Nathan argues that “politicians in a factional system are ‘condemned to live together’.”Footnote 23 He claims that if one faction becomes stronger, other factions would make an alliance against it because the main concern of a faction is survival.Footnote 24 Examining the factional connections of Central Committee members from 1921 to 2007, Victor Shih and colleagues find that power sharing has been the usual power configuration, with a couple of exceptions when the CCP faced serious external threats such as civil war.Footnote 25 Several empirical studies demonstrate that factional politics during the Hu Jintao era were characterized by a power balance between Hu Jintao's and Jiang Zemin's factions.Footnote 26

To date, no scholarship on factions in China has clearly defined what would constitute a dominant faction. Therefore, we propose the rough rule of thumb that the dominant faction's share of positions among the top ranks must, on average, near or surpasses twice that of all competing factions combined. When a faction has double the number of highly placed clients of its rival factions, it prohibits those other factions from effectively balancing out the dominant faction's power. By contrast, if rival factions together control nearly as many top-ranked positions, this would indicate a balance of power between factions. This serves as a general guideline rather than a hard rule; however, by defining and applying this standard, we can show a balance of power in the Hu era and a clear shift with the strengthening of Xi's faction marking the emergence of a dominant faction.

We hypothesize that Xi has strengthened his faction by promoting more of his clients than his predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, did. We test our hypothesis primarily through an analysis of turnover of provincial Party secretaries and governors, which are the top two positions at the provincial level. Under the one-level down personnel appointment system in China, top national leaders have the authority to appoint and dismiss provincial leaders. The position of provincial Party secretary is often seen as an important stepping stone to moving into a top leadership position on the Politburo or other key position within the regime. Provincial governorships are, in turn, an important step towards provincial Party secretaryships. The two positions act as a bridge between local and national positions. Provincial Party secretaries and governors, as the top two officials in a province, also play an important role in channelling the centre's directives to localities. A leader's ability to distribute these highly desirable positions to clients and advance them to higher positions is a key facet of his power and an important channel through which to build support.

Previous studies suggest that dominant factions are rare, if not unheard of, in the CCP. Under what conditions, then, would a dominant faction be likely to emerge? Although our data provide compelling evidence that a dominant faction has emerged under Xi Jinping, it is less clear why this has happened. While more research will ultimately be needed, we argue that a combination of three factors contributes to the emergence of a Xi dominant faction. According to Nathan, it is unlikely that a dominant faction would emerge, owing to the reason that other factions would join forces against it.Footnote 27 However, this external balancing is feasible only when there are several reasonably strong factions. If there are only two significant factions competing with each other, there is no possibility for either to form an alliance. Each faction must rely on internal balancing, i.e. strengthening its own faction, which may not be easy. If one faction fails to do so, it is possible that a dominant faction could emerge. When Xi took power, there were only two rival factions, the Shanghai faction led by Jiang Zemin and the CYL faction led by Hu Jintao. Xi had the backing of the Shanghai faction. Additionally, by failing to name a successor, Xi Jinping has prevented an obvious nucleus around which a new rival faction could form. Hu's faction could not form an alliance with other factions to check the rise of a strong faction in this bi-factional context.

Second, when Xi assumed the mantle of general secretary of the CCP, he enjoyed a relatively favourable power configuration at the top, compared with his two predecessors. Considering that the general secretary of the CCP had a two-term limit (ten years) and that the CCP has rules that insist on the step-by-step promotion of officials, rather than jumping levels of hierarchy, favourable initial conditions could provide a significant advantage to the heads of the CCP in empowering their factions. When Jiang Zemin suddenly took the position of CCP general secretary following the suppression of the Tiananmen movement in 1989, his power was constrained by the revolutionary generation led by Deng Xiaoping. Similarly, when Hu began to govern in 2002, five of the-then nine members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the most influential positions in the CCP, belonged to Jiang's faction.Footnote 28 In contrast, when Xi took power in 2012, only one of the seven members of the Standing Committee was from Hu's faction. As we would expect, Xi's faction was generally weaker than Hu's faction when Xi became CCP leader in 2012. However, because Jiang's faction supported Xi and still had a powerful presence in the Standing Committee, Xi actually enjoyed more influence in the Standing Committee on his first day in office than Hu ever did. Moreover, Xi took the position of chairman of the Central Military Commission at the same time as he became general secretary in 2012. In contrast, Hu only assumed this position two years after becoming the general Party secretary. These conditions may have provided Xi with an opening to build up his faction quickly.

Third, Xi Jinping launched a massive anti-corruption campaign that targeted both “tigers” (high-level officials) and “flies” (lower-level officials). By punishing Zhou Yongkang 周永康, a previous member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo, Xi signalled that a top leadership position was no longer protection against corruption investigations. Intimidating high-ranking leaders with the possible threat of corruption charges probably helped Xi to undermine opposition to his consolidation of power, strengthen his own faction and weaken his rivals’ factions.

Measurement

Measuring the strength of factions is challenging, but considering that factional struggle is fierce in personnel appointments, the proportions of official positions taken by factions indicate the strength of a faction. We examine four top-ranking positions within the Chinese hierarchy: the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the Politburo, provincial Party secretaries and provincial governors. The Politburo comprises the CCP's top leaders. In practice, the power of the Politburo is concentrated in its Standing Committee. For the sake of clarity, we use the term Standing Committee to refer to Politburo members who are on the Standing Committee and the Politburo to refer to those who are not.

Since the significance of official positions varies by rank, we give more weight to positions in higher ranks by calculating the proportions of factional members in each rank and then computing the average of these proportions. A higher rank has fewer positions than a lower rank. Thus, one additional seat occupied by a factional member at a higher rank contributes more to the strength of a faction than one at a lower rank. This simple measurement provides a rough measure of factional strength.

It is challenging to identify factional ties in Chinese elite politics since the official policy of the CCP is that factions are prohibited.Footnote 29 We follow Cheng Li in identifying factional ties that are formed based largely on experience of working in the same unit during an overlapping period of time.Footnote 30 This criterion clearly satisfies three of the four core attributes of the concept of factions: face-to-face interaction, longevity and power inequality. The fourth criterion, interest exchange, is less clear owing to its clandestine nature. In order to identify every factional member in the four ranks, we reviewed the secondary literature on factional affiliations as well as the biographies of provincial leaders to determine whether they had worked with Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao or Xi Jinping. If so, we coded them as belonging to one of these factions.

Jiang Zemin's faction evolved mostly through the ties he cultivated during his time in Shanghai. Faction members include not only those who worked with Jiang in Shanghai before his appointment as general secretary of the CCP but also those who spent most of their careers in Shanghai, such as Han Zheng, and who worked with Jiang Zemin in the First Machine Building Ministry, for example Jia Qinglin 贾庆林. In addition, analysts identify several provincial leaders as Jiang's clients even though they did not work with Jiang Zemin prior to 1989. We therefore include the following five leaders in Jiang's faction as they are usually classified as Jiang's clients: Zhang Dejiang 张德江, Yu Zhengsheng 俞正声, Li Changchun 李长春, Li Hongzhong 李鸿忠 and Xi Jinping (when he was still a provincial leader).Footnote 31 If we excluded these leaders, we would then run the risk of underestimating the strength of Jiang's factional ties. We use this broader interpretation of Jiang's faction to ensure that we do not bias our data in favour of our hypothesis that Xi's faction is stronger than Jiang's faction was.

Hu Jintao's faction was born from his links with the CYL and is therefore sometimes called the CYL faction. Following Cheng Li, we identify Hu as having factional ties with those who had positions in the CYL above the provincial level during the years that Hu served as the secretary of the CYL.Footnote 32 We identify 23 provincial leaders who satisfy this criterion. Among those who were not members of the CYL, we include Guo Jinlong 郭金龙 and Sun Chunlan 孙春兰 as Hu's clients, following Cheng Li's classification.Footnote 33 One of Hu's clients, Li Keqiang, was designated as the successor to the second most powerful position in China (premier) in 2007. Li shares the same factional basis as Hu Jintao, the CYL. It is likely that Hu tried to strengthen his faction by incorporating Li's clients into his faction. Following the logic of identifying Hu's clients, we identify Li Keqiang's clients as those who had positions in the CYL above the provincial level while Li served as secretary in the CYL. We identify 17 provincial leaders as Li's clients. Of these, seven also belonged to Hu's faction. Besides the CYL connections, Chen Quanguo 陈全国 and You Quan 尤权 were included as Li's clients since Chen had worked with Li in Henan province and You Quan worked with Li in the State Council.Footnote 34 We combine both Hu's and Li's clients to create a joint Hu–Li faction. Joining two groups of clients runs the obvious risk of overestimating the strength of the Hu–Li faction. However, given that our hypothesis is that this faction is relatively weak compared to Xi's faction, we want to maximize our inclusion of possible factional members.

We use Cheng Li's analyses of Xi Jinping's inner circles to identify Xi's clients. He points to three bases for Xi's connections: Shaanxi, friends from Xi's formative years and work experience.Footnote 35 Shaanxi is where Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋, Xi Jinping's father, was born and raised and worked in the early years of his career. Xi Jinping himself spent several years in Shaanxi during the Cultural Revolution as a “sent-down youth.” Among provincial leaders, Zhao Leji and Li Xi 李希 can be regarded as Xi's followers, based upon their Shaanxi connections.Footnote 36 Chen Xi 陈希 is included in the Xi faction on the basis of having become acquainted with Xi while both attended Tsinghua University.Footnote 37 The provincial leaders in the Xi faction developed a relationship with Xi when he worked in several provinces, including Hebei, Fujian, Zhejiang and Shanghai.Footnote 38 We identify those who had overlapping work experience with Xi in these regions as his clients. In total, we identify 23 provincial leaders to be Xi's clients.

The Strength of Factions and Factional Power Configurations

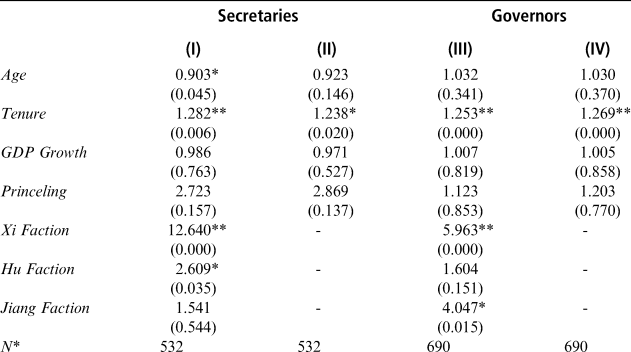

In Figure 1, we compare the strength of factions led by the ruling head of the CCP with those led by the former head of the CCP in the Hu and Xi eras. The number represents the proportions of factional members out of the total number of positions at that level. We also show the years the Party Congress was held, which is when the Politburo and its Standing Committee changed personnel. Staff turnover of provincial leaders occurs throughout each term of the Party Congress. Finally, we show 2018 to use the most recent available data.

Figure 1: The Proportions of Factional Members by Different Ranks (%)

These figures indicate a similarity in the life cycle of factions. When a leader first becomes head of the CCP, his faction is relatively weak at the highest levels. During his time in power, his faction gains in strength. The strength of Jiang's and Hu's factions peaked the years they retired, 2002 and 2012, respectively. Following their retirement, their factions began to weaken. This is typical for personalized factions because they depend on clientelist ties between the faction head and followers. Figures from 1A to 1D compare Hu's faction with Jiang's faction in the Hu era; figures 1E to 1J compare the Hu–Li faction with Xi's faction during the Xi era. After 2012, Hu's faction incorporated Li's because Li became the second highest leader in the Party and allied with Hu.

The growth of the Jiang faction during his rule, which is not presented in these figures, shows similar dynamics. At the 14th Party Congress in 1992, the appointments to the Politburo and its Standing Committee reflected the will of the older leaders. By appointing Hu Jintao to the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the older generation of leaders intended that Hu would be a successor to Jiang; Liu Huaqing 刘华清, a top-ranking general, would exert influence on the military; and Qiao Shi 乔石 and Li Ruihuan 李瑞环 were already well established in the top leadership. This old guard constrained the power of Jiang's faction in a manner similar to that in which his faction would constrain Hu. Faced with these limitations, Jiang gradually tried to consolidate his power. In the 15th Party Congress in 1997, Jiang promoted four of his clients to positions on the Politburo. By 2002, when Jiang yielded the position of general secretary of the CCP, his clients held more than half of the positions on the Standing Committee.

When Hu Jintao began to rule, his power was seriously constrained by Jiang's faction. Over the years, however, Hu also strengthened his faction. In 2007, when Hu's second term started, his faction held only 22 per cent of the seats on the Standing Committee of the Politburo. However, Hu had more factional members than Jiang in the levels below the Standing Committee. In comparison, in 2007, although Jiang's faction occupied 44 per cent of the seats on the Standing Committee, his faction held only a few positions below this level. When Hu relinquished his positions to Xi at the end of 2012, Hu's faction occupied a significant proportion of the positions at the Politburo and provincial Party secretary levels but was less successful in placing its factional members on the Standing Committee.

When Xi took power, his faction was generally as weak as his predecessors’ had been. However, Xi strengthened his faction much more quickly than his two immediate predecessors did. In 2018, Xi's faction took 43 per cent of the seats on the Standing Committee of the Politburo; 56 per cent of the seats on the Politburo; 42 per cent of provincial Party secretaryships, and 26 per cent of provincial governorships. Even when we compare Hu's faction and Xi's faction in the first year of their second terms (See Figure 1, C and H), we find that Xi's faction held much higher shares of the seats in each rank – except among provincial governors, the lowest rank among the four.

Interestingly, the proportions of factional members vary significantly by rank. In 2002, Jiang's faction took a significant share of the seats on the Standing Committee of the Politburo but it held smaller proportions of lower-level positions. On the other hand, in 2012, Hu's faction took a small share of the seats on the Standing Committee of the Politburo but held substantial proportions at lower levels. This suggests that investigating only one rank can paint a misleading picture of the strength of factions. It is noteworthy that Xi's faction has achieved considerable proportions at all levels, which indicates the relative strength of Xi's faction.

Considering that power is concentrated at the top in Chinese politics, the head of any faction who wishes to increase his power would focus on securing positions for his clients among the upper ranks. But he would also be interested in placing his clients in lower positions – because by doing so, the head of a faction could broaden his factional power base, strengthen his influence in the provinces and lay the groundwork for future promotions to higher levels. Also, if faced with strong opposition from competing factions when trying to appoint his own followers to positions in the upper echelons, the head of a faction might promote his clients to lower ranks as a second-best strategy. This appears to have been the case for Hu Jintao. Constrained by the Jiang-dominated Standing Committee of the Politburo, Hu's second-best option was to manoeuvre his own clients into positions below that level.

Figure 1 shows smaller shares of Jiang Zemin's faction among provincial-level positions. What accounts for this? First, it may be that Jiang was more constrained by other power sources when appointing his followers to provincial leadership positions. In the1990s, Jiang's influence was severely curtailed by powerful leaders such as Qiao Shi and Li Ruihuan as well as by the elderly generation of leaders who still held authority owing to their roles in the revolution. Then, from the early 2000s, Jiang's power was constrained by the rise of Hu Jintao's faction. Second, Jiang Zemin had a narrower base of support than was the case for Hu Jintao or Xi Jinping. Prior to his appointment as CCP general secretary, Jiang's career was mostly confined to Shanghai. On the other hand, Hu Jintao's power base was the CYL, a nationwide organization. Xi Jinping had a wider pool of connections partly because he was a princelingFootnote 39 and partly because he had worked in different locations including Hebei, Fujian, Zhejiang and Shanghai. Given his narrow base of support, it seems likely that Jiang focused on appointing his clients to top leadership positions.

Table 1 shows the strength of factions calculated by the average proportions of all four ranks held by factional members. In 2002, when Jiang relinquished the post of general secretary of the CCP to Hu Jintao, Jiang's faction held 25 per cent of the positions in the top four ranks on average, whereas the share held by Hu's faction was 12 per cent. After five years of Hu's rule, the average share of positions held by his faction increased to 24 per cent, while that of Jiang's faction decreased to 19 per cent. During this period, the strengths of Hu's and Jiang's factions were similar if shifting, creating a balance of power. In 2012, when Hu retired at the end of year, his factional power peaked with an average of 33 per cent of the positions in the top four ranks. By this time, Jiang's faction had weakened, holding only 12 per cent of seats. Since Jiang's faction backed Xi to succeed Hu, it is reasonable to assume that Jiang's and Xi's factions allied at that time. In total, these two factions took 24 per cent of the seats in the top four ranks in 2012, enabling them to check the Hu–Li faction. After five years of rule, however, Xi had dramatically strengthened his faction, on average taking 39 per cent of the seats in the top four ranks. This is a much higher proportion than the 24 per cent of seats that Hu's faction occupied during the middle of his administration. By 2018, Xi's faction occupied, on average, 42 per cent of the seats in the top four ranks. At the same time, the Hu–Li faction had rapidly diminished, holding only 13 per cent of seats. As Xi's faction overwhelmed and quickly marginalized the Hu–Li faction, the balance of power was tipped and Xi's faction became dominant.

Table 1: The Average Proportions of Factional Members in the Top Four Ranks

Factional Promotional Advantages among Provincial Leaders

In order to strengthen their factions, the heads of the CCP are likely to provide promotional advantages to their followers in order to manoeuvre them into the higher ranks. We test the hypothesis that Xi bestowed stronger promotional advantages to his clients compared with his two immediate predecessors. To develop the data on cadre promotions, we first make some choices on how to represent promotions. For the provincial leaders we examine, we code one of four outcomes for each year. The first is that no change of position occurs: the official continues to serve in the same role with no movement in the official hierarchy. This status quo outcome, which includes lateral moves to a different province, is by far the most common for any official in any given year. The second outcome is that an official is promoted at some point during the year. For provincial Party secretaries, this means taking a national leadership position, such as becoming a member of the Politburo. For provincial governors, this means taking a ministry-level position including a provincial Party secretaryship. Third, an official is retired when his or her term ends and age prevents the official from remaining in position or being promoted to the level above. Officials who are retired in this way usually end up taking an honorary position such as the chairmanship of a provincial people's congress. Fourth, an official is removed or demoted, including for corruption or other offences, before the retirement age.

In total, 188 people served as provincial Party secretaries from 1989 to 2018. Of these, 39 (21 per cent) were promoted during this time. Of the 48 provincial Party secretaries with factional ties, 26 (54 per cent) were promoted. In comparison, only 9 per cent of provincial Party secretaries without factional ties were promoted. Thus, factional members were six times more likely to be promoted past Party secretary than were non-factional members, which clearly demonstrates the enormous importance of factional ties.

A total of 242 people served as provincial governors from 1989 to 2018. Among them, 103 (43 per cent) were promoted. The chances of promotion are much higher for provincial governors than for provincial Party secretaries. This is because the position of provincial governor is lower ranked and there are the same number of provincial governorships and Party secretaryships. There were 56 provincial governors with factional ties. Of these, 66 per cent were promoted, whereas only 35 per cent of those who did not have factional connections were promoted. Factional ties clearly provide promotional benefits for governors, but they are not as important as they are for provincial Party secretaries.

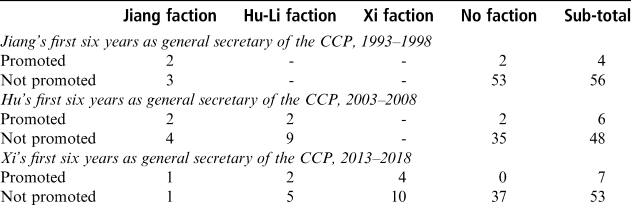

In order to examine whether Xi's faction had a greater advantage in promotion than Jiang's and Hu's factions, we compared the promotions of provincial leaders in the first six years that the heads of factions ruled. It would be ideal to examine the whole period of rule. However, at the time of data collection, the most recent year was 2018, the sixth year of Xi's rule. For Jiang Zemin, we regarded 1993 as the first year of rule because he assumed the role of general secretary in the middle of the Party Congress term.

Table 2 shows that from 1993 to 1998, 56 provincial Party secretaries failed to gain promotion. Among the four who were promoted, half were Jiang's clients. This clearly shows the disproportionately high chance for promotion that factional membership provided. During the first six years of Hu's rule, six provincial Party secretaries were promoted while 48 were not. Among those promoted, two belonged to Hu's faction, two were affiliated with Jiang's faction and two had no factional ties, indicating not only the power of factional affiliation but also a power balance between factions. Table 2 shows that Xi's clients netted four out of the seven promotions handed out from 2013 to 2018, while two of Hu's clients and one of Jiang's clients were promoted during this period. In short, Xi promoted twice as many of his clients to Politburo-level positions as did Jiang Zemin or Hu Jintao during the equivalent period of their rule.

Table 2: Provincial Party Secretaries Promoted (by Factional Affiliation), 1993–2018

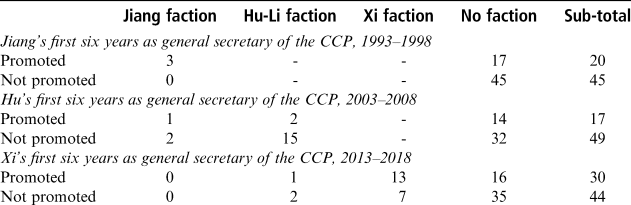

The uniqueness of the Xi era is even more noticeable at the gubernatorial level, as shown in Table 3. In the first six years of the Jiang administration, only three of Jiang's gubernatorial clients were promoted whereas 17 governors without factional ties were promoted. Similarly, in the first six years of the Hu era, only two out of Hu's 17 gubernatorial clients were promoted while 14 governors without factional ties gained promotion. In contrast, in the first six years of the Xi administration, his gubernatorial clients obtained 13 promotions. These figures offer clear evidence that Xi's clients are more likely to be promoted.

Table 3: Provincial Governors Promoted (by Factional Affiliation), 1993–2018

There are two alternative explanations for our findings, although we do not believe either detract from our main finding. The first is that promotions make factional allegiance more legible – if an official is promoted, more attention may be paid to their background and they are thus more likely than non-promoted officials to be considered factionally affiliated. This does not detract from our findings for two reasons. First, the data on factional affiliation were coded before the authors coded promotions; promoted officials received the same biographic scrutiny as non-promoted officials. Second, we are primarily concerned with the question of whether the Xi faction is more dominant than previous factions. If factional affiliation becomes more legible owing to promotions, this phenomenon should apply approximately equally to every faction. It would not influence the finding that Xi's clients are being promoted at a higher rate than are the members of other factions.

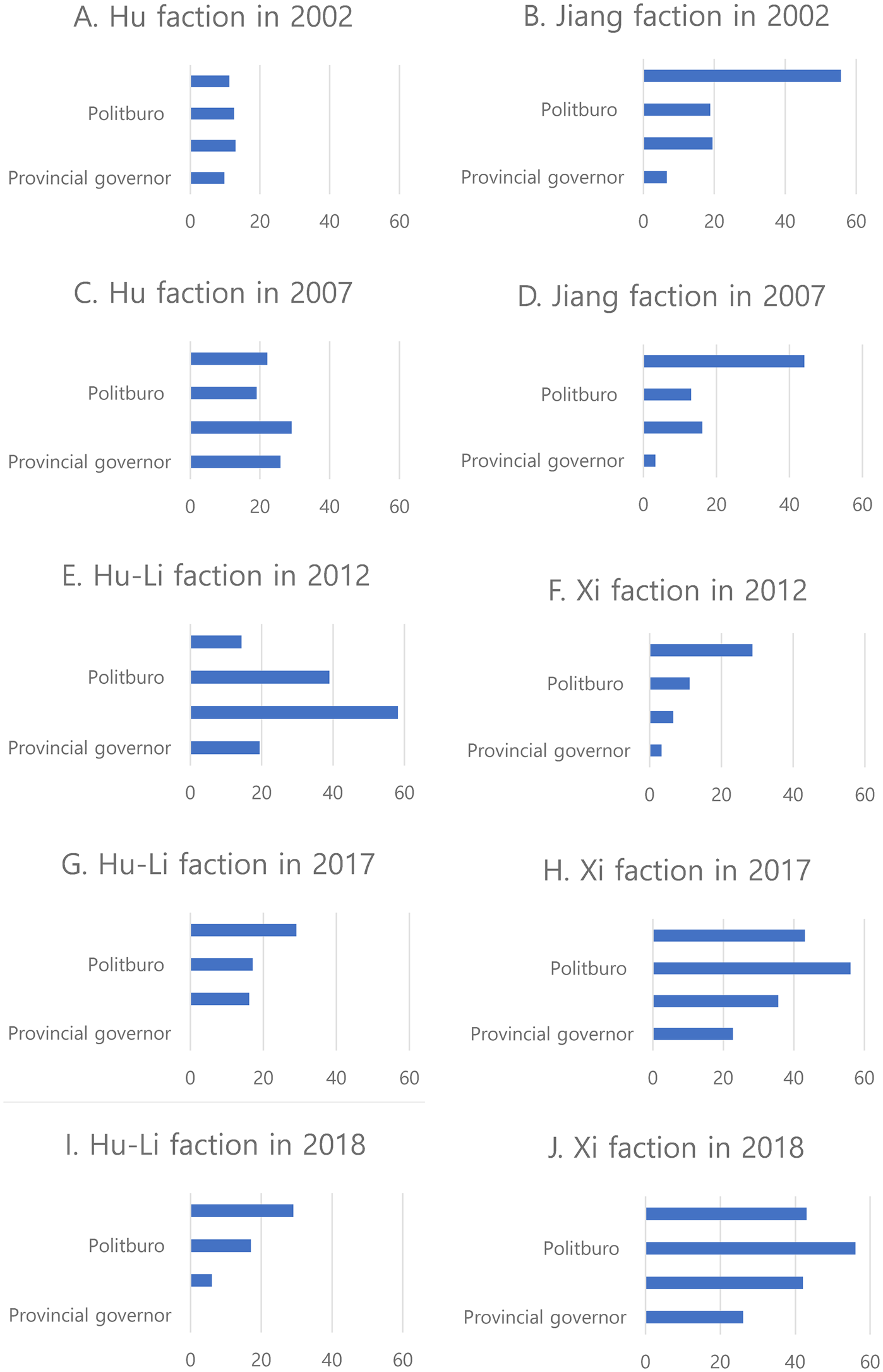

The second, alternative explanation is that Xi's clients are being promoted at a greater rate owing to their personal characteristics – perhaps they are more capable, more experienced or perform better than Hu–Li's clients and this explains their higher promotion rate. To test this explanation, officials identical in every relevant characteristic, the only difference being factional affiliation, should be compared. Typically, regressions are used to approximate this type of comparison – regressions estimate the impact of isolating the key predictor variable (factional membership) on promotion by holding all other variables (age, tenure, GDP growth, province and princeling status) equal. A coefficient plot of such a regression predicting promotion is shown in Figure 2. The plot demonstrates that even while controlling for tenure, age, princeling status and average GDP growth during their time in the post, Xi's clients appear to have a greater advantage, and this is statistically significant for both Party secretaries and governors.

Figure 2: Regression Results on Promotion Chances, 1989–2018

The details of the functional form of our regression and full results are presented in the Appendix. Higher log odds (X Axis) indicate that a variable is estimated to lead to a higher predicted chance of promotion. A 95 per cent confidence level is displayed by the bars that connect to the point estimates. If the confidence interval includes zero, one should interpret the coefficient as statistically indistinguishable from having no impact on the odds of promotion. Overall, this model adds support to our argument that the Xi faction has been distinctively successful in increasing the promotion odds of its members. At both the level of governor and Party secretary, the point estimate for the Xi faction is larger than that of either of the other two factions. Additionally, only Xi's faction shows a statistically significant effect for both governors and Party secretaries. Because of the small n size, the confidence intervals are relatively large, so we do not wish to place undue emphasis on the results of this regression. However, the point estimate differences are substantively quite large and lend further support to the findings of the descriptive analysis above.

Conclusion

There has been intense scholarly and popular interest in whether the Xi Jinping era is a break with previous administrations or should be seen as a continuation of past trends. Our analysis exhibits both continuity and change in factionalism in Chinese elite politics. All three recent general secretaries (Jiang, Hu and Xi) developed personalized factions. Power relations between factions, however, changed – from a power balance under Hu and Jiang to the emergence of a dominant faction under Xi. We show that Xi strengthened his faction by providing his clients with greater promotional advantages than those offered to the clients of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao.

We suggest that a combination of three factors – the lack of an external balancing option for the Hu–Li faction, initially favourable conditions for Xi at the top when he began to rule, and massive anti-corruption campaigns – contributed to the emergence of a dominant faction under Xi. Whether Xi's success in strengthening his faction is owing to advantageous initial conditions, his organizational acumen, or some other unobserved factor, we cannot say conclusively. These are important follow-up research questions: why have previous factional heads not been able to promote members of their faction as effectively as Xi has? To what extent is this down to less favourable initial conditions, as our study suggests? Regardless of the reason, the data are clear that the current rules of promotion strongly favour Xi's clients to an extent not seen in previous administrations.

Nathan argues that a balance of power among factions leads to policy deadlock.Footnote 40 While other factors also affect policymaking, it would be interesting to investigate whether the rise of a dominant faction leads to significant policy changes in the Xi era. Some evidence of bolder policies that seem more likely to emerge under a dominant faction are already evident, such as Xi's unprecedented anti-corruption drive. Indeed, Elizabeth Economy goes so far as to call Xi's reforms a “Third Revolution.”Footnote 41 Although we demonstrate that a dominant faction has emerged under Xi, this raises many more questions and avenues for future research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rachel Stern, Yang Zhang, Zach King, Ryan Schrock, Yuchen Cao and our reviewers. Eun Kyong Choi gratefully acknowledges the research fund provided by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical notes

Eun Kyong CHOI is a professor in the department of Chinese foreign affairs and commerce at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Korea. Her research interests include elite politics, the politics of revenue extraction and social welfare provision.

John Wagner GIVENS is a professor in the School of Government and International Affairs at Kennesaw State University. His research interests include online politics and media, legal advice websites and smart cities, as well as Chinese politics, law and foreign policy. He previously held positions at Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Louisville and the University of the West of England. He also works as an expert in China-related legal cases.

Andrew MACDONALD is an assistant professor at Duke Kunshan University. He was previously at University of Louisville and holds a DPhil from the University of Oxford. His research focuses primarily on public opinion in authoritarian countries.

Appendix

Full regression details and results

For our regression form, we use a fixed effects panel data logit approach. A fixed effects panel data model means that any unique features of a province that affect promotion are controlled for. Our unit of analysis is each cadre's chance, each year, of being promoted. We organize our regression and data this way for two reasons. First, because officials' chance of promotion changes each year as their tenure increases, their age increases, and their economic performance changes each year, so do their odds of promotion. We use a panel data approach to capture the fact that observations are not truly independent – the odds of being promoted in year two versus year three of tenure are, in fact, related. A panel data approach helps to account for both of these factors. Regressions of similar form have been widely employed in the literature on leadership politics, both within China and without.Footnote 42

Previous studies suggest that economic performance affects provincial leaders’ chances of promotion. Thus, we include this variable in our models in order to control its effect.Footnote 43 For the economic performance of provincial leaders, we calculate the annual GDP growth rates of the province, adjusted for inflation.Footnote 44 We use the average of the GDP growth rates over the years that a provincial Party secretary governed the province. For example, the GDP growth rate in the second year of a provincial Party secretary's term is the average of the first year and second year growth rates. Other variables are standard controls for overall turnover rate, age of the official and length of tenure of the official. We also include a variable for princelings to examine whether the sons and daughters of high-ranking officials have advantages in promotion.

The results displayed in Table 1A show that Xi's faction is uniquely successful at promoting its clients, while the Hu–Li and Jiang factions are estimated to be only moderately successful at promoting their members. Provincial Party secretaries in Xi's faction are estimated to be roughly 12 times as likely to be promoted, all else being equal, when compared to provincial Party secretaries not in Xi's faction. Provincial governors in Xi's faction are estimated to be six times more likely to be promoted. Being a member of the Hu–Li faction increases the odds of promotion for a provincial Party secretary by roughly 2.6 times, but the odds of being promoted for a governor are statistically insignificant. The odds of promotion for governors in the Jiang faction is about four times higher than for those outside it. However, for a provincial Party secretary, being in Jiang's faction did not confer a statistically significant advantage in terms of promotion. The Hu–Li faction appears to be more successful in promoting provincial Party secretaries while the Jiang faction appears to have been more successful in promoting governors. However, both factions’ promotional power pale in comparison to the increase in promotion odds afforded to members of the Xi faction.

Table 1A: Fixed Effects Panel Data Regression Results on Promotion Chances, 1989–2018