The Brexit legislative process generated the most hectic parliamentary phases in the recent history of UK politics. In contrast to its tradition of solidity, the executive suffered several cabinet resignations, was defeated in a series of consecutive divisions, experienced a record number of rebellions among its backbenchers and lost control of the agenda.

Shortly after Prime Minister Theresa May lost the second meaningful vote on her European Union (Withdrawal) Act and was compelled to ask for an extension of the initial deadline of Article 50 of the EU Treaty, she had to give way to the House of Commons in trying to find an alternative solution to the Brexit conundrum. The government lost by a substantial margin a vote on the so-called Letwin amendment, named after a senior Conservative MP, which gave the legislature precedence over the executive in discussing and voting on its own motions regarding Brexit.

This interference was potentially much more invasive than previous instances of parliamentary scrutiny of the withdrawal process (Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Christiansen and Fromage2019; Thomson and Yong Reference Thomson, Yong, Christiansen and Fromage2019). The prime minister, on announcing the opposition of her government to the Letwin amendment, said that parliamentary control of House business ‘would set an unwelcome precedent, which would overturn the balance between our democratic institutions’ (Hansard 2019a: 25 March, col. 24). However, three of her ministers resigned to vote in favour, together with another 27 Conservative backbenchers and a more compact opposition, with only eight Labour MPs supporting May's position. This opened the possibility of holding a series of eight indicative votes on 27 March 2019 in the House of Commons and then another four indicative votes a few days later.Footnote 1

These 12 divisions can shed some interesting light on the political dynamics of a traditional Westminster democracy when its cornerstone, the cabinet, loses its grip on the legislature and on the structure of the party government. What guides the choices of the MPs in those circumstances? If their representation duties are no longer filtered by their party membership, how do they fulfil them? How do they ‘act for’ those who elected them, balancing the diverse roles associated with the possible interpretation of their mandate (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967)?

In answering these questions, this article is structured as follows. First, we illustrate the content of the motions put to a division and describe the results of those votes. Next, we discuss some theoretical assumptions regarding the voting behaviour of MPs in those circumstances, especially considering their responsiveness to their electorates, and derive some testable hypotheses. We then reconstruct the political space that characterized the House of Commons during those 12 indicative votes and test those expectations. In the conclusion, we verify the possible electoral consequences of those behaviours in the subsequent 2019 general election and discuss the prospects for British politics.

Theory: responsive or compromising

Democracies are classed as such because they respond to the preferences of their citizens. Hence, we expect the voting behaviour of MPs in the House of Commons to reflect the preferences of their principals. However, there are two problems with applying that expectation directly to the parliamentary Brexit process. The first has to do with the fact that this type of vote was clearly exceptional in this institutional context, while the second concerns the multiplicity of non-overlapping principals.

Typically, the responsiveness of Westminster democracies depends on the fact that, as a consequence of competition along a single dimension in a two-party system, the position of the cabinet overlaps with that of the median voter (Golder and Lloyd Reference Golder and Lloyd2014). In this context, and due to the chain of delegation of a well-enforced party government (Strøm Reference Strøm and Strøm2006), ‘most cutting lines will split governing members against opposition members’ (Hix and Noury Reference Hix and Noury2015: 252). However, this did not happen during the Brexit process, as testified by the large number of rebels on both sides.Footnote 2

Over the years, the extent of the integration of the UK within the European Union had been a highly problematic and divisive issue (Hobolt Reference Hobolt2016; Thompson Reference Thompson2021). It introduced a second cross-cutting cleavage in British politics that made the entire representation process extremely complicated. Moreover, it was a polarizing issue, making it harder to find a median solution. Finally, the fact that the government party was split over the EU (Heppell et al. Reference Heppell2017; Lynch and Whitaker Reference Lynch and Whitaker2017) prevented the usual aggregation of preferences in the context of a well-functioning party government.

The second problem has to do with the existence of multiple principals or, from a different perspective, of different styles and foci of representation (Eulau et al. Reference Eulau1959). MPs may interpret their representative role with different degrees of freedom, acting more as delegates or as trustees, and thinking more at a local level or a larger national public. According to Heinz Eulau et al. (Reference Eulau1959), ‘politicos’ are exactly those who seek to reconcile those opposite role orientations, responding to a range of potentially contrasting demands. In a Westminster democracy, this outcome is generally favoured by the typical dynamics of party government that help pragmatically solve the contradiction between local and general interests, between being an ambassador of the constituency and being a representative of the nation (Burke Reference Burke1999).

Nonetheless, Brexit also put this cornerstone of British politics under pressure, with several MPs from opposite sides of the House confronted by a real dilemma regarding whom they should represent, and how they should interpret that mandate. In announcing his vote against the prime minister's agreement, Sir William Cash ordered the potentially divergent principals by quoting another prime minister: ‘As Churchill once said, and as I was reminded at the time of Maastricht by my constituents, we should put our country first, our constituency second, and our party third’ (Hansard 2019b: 15 January, col. 1050). Another Conservative MP, Justine Greening, agreed that ‘Brexit is not about party politics’; she eventually voted against her frontbenchers but recognized the problems that she faced in representing the preferences of her electorate:

All of us are genuinely asking ourselves how we can represent our communities and do what is in the best interest of this country. … I represent many Remainers in my constituency who think that if we are still following so many rules, we should be around the table setting them. I also represent the many Brexiteers in my community, and they simply do not believe that this is the Brexit they felt they were voting for. (Hansard 2019b: 15 January, col. 1067)

Labour MPs had similar problems, as acknowledged explicitly by Adrian Baley:

I represent a constituency that voted 70% Brexit, and I am a Remainer. I do not pretend that that is a comfortable position to be in. I voted to trigger article 50 because I felt that I had to honour the referendum result, and I have been lobbied heavily to say that, as a representative, I should do what my constituency wanted. (Hansard 2019b: 15 January, col. 1099)

Resul Umit and Katrin Auel (Reference Umit and Auel2020: 2) find confirmation of these contrasting perspectives in their analyses of legislative speeches in the aftermath of the Brexit referendum. They recognize that ‘where there is no consensus among their principals over a policy, MPs cannot avoid defying one or more of these principals with their vote in parliament. As a result, they become dissenters by default – irrespective of their own preferences’. As Conservative MP Simon Hoare put it, ‘I do not possess the judgment of Solomon. None of us does. All I can do is assure [my constituents] that I am trying to do my best for them and for our country. I am conscious that in so doing I will not please everyone, but I do not think that that is the purpose of politics’ (Hansard 2019b: 15 January, col. 1107).

MPs have their own ideological preferences, which may or may not overlap with those of the party to which they belong (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1993), and the way in which they campaigned for the 2016 referendum can represent a proxy of the preferences guiding their legislative behaviour (Aidt et al. Reference Aidt2021). However, it is unlikely that MPs simply followed their idiosyncratic understanding of the Brexit issue or, better, that their position was not framed by the way in which they perceived their role as parliamentarians (Trumm et al. Reference Trumm2020). There are a set of factors that the literature identifies as capable of framing the way in which an MP understands her or his role as an agent (Blomgren and Rozenberg Reference Blomgren and Rozenberg2012; Moore Reference Moore2018). We summarize them in three main categories: political, socioeconomic and institutional factors.

The most evident political factor that affects voting behaviours in a parliamentary democracy is party membership, especially when it is enforced by whipping practices. However, Theresa May's agreement was voted down in the House of Commons three times, despite pressure by the government to support it, and ‘Brexit caused a wedge in party politics’ (Intal and Yasseri Reference Intal and Yasseri2021). Indicative votes usually enjoy wider margins of freedom, and the Conservative Party actually did not put forward any directives on these votes, not least because it was also the most divided party in terms of motion proposals. However, opposition parties such as Labour and the Scottish National Party (SNP) whipped on, or more informally supported, some of the motions put to a division. Philip Cowley and Mark Stuart (Reference Cowley and Stuart1997) convincingly demonstrated that party divides matter, even in the case of free votes, and a fortiori, we expect such divides to explain a non-marginal share of voting behaviour in the discussion of the alternatives to the government's exit agreement.

If, because of the exceptionality of the situation, parties might not represent the primary force shaping parliamentary behaviours, constituencies can be considered the genuine principals. In fact, during the debates on the Brexit agreement, constituencies were invoked by many MPs to justify their voting decisions, despite the contradictory beliefs held by the public on the specific form that the exit should take (Vasilopoulou and Talving Reference Vasilopoulou and Talving2018). The relationship between a representative and his or her electoral constituency is certainly bidirectional. MPs are chosen because they somehow reflect the preferences of their constituency, and once in office they contribute to shaping those preferences, particularly in regard to individual issues or decisions. This was in fact the case with the Brexit referendum, so MPs often cited their election in a Brexit or Remain district to explain their position during the parliamentary divisions. Indeed, when MPs defy a publicly expressed preference, such as the referendum result, they feel compelled to explain at length the reasons for their lack of compliance (Umit and Auel Reference Umit and Auel2020).

However, many districts were extremely divided at the time of the referendum; approximately one-quarter of the electorate did not turn out to the polls. Demographic change (an important divide in this circumstance) had already shifted the electoral base by the time of the votes three years later, and new information as well as the details of the negotiated exit agreement could have changed voter opinions (Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt2020). For all these reasons, MPs might still have sought to pursue their constituencies' interests but at the same time felt that the result of the referendum in their district could not be considered a reliable signal in this regard (Auel and Umit Reference Auel and Umit2020).

Such interests are probably shaped by the underlying socioeconomic structure of districts. First, socioeconomic divides typically define the electoral geography of a country, especially in settings characterized by a relatively homogeneous political culture such as the UK. Second, preferences on leaving or remaining in the European Union have been convincingly connected to socioeconomic cleavages (Carreras et al. Reference Carreras2019; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Evans and Menon Reference Evans and Menon2017; Watson Reference Watson2018). We can thus expect that constituencies' preferences and interests, either as expressed during the referendum or in relation to the deeper structure of the respective constituencies, affected MPs' voting behaviour in some way.

Personal beliefs can enter the equation when representatives feel that they have a clear point to make or a superior collective interest to serve. This condition applies perfectly to the context of the Brexit indicative votes, when the traditional shortcuts of Westminster politics proved unable to force a solution, and when the outcome clearly had to do with contrasting interpretations of the common good of the country. Political autonomy may concern individual characteristics, such as age, education or gender (Heppell et al. Reference Heppell2017), but it most likely reflects some institutionally derived trait, such as parliamentary seniority, margin of election or ministerial career (Aidt et al. Reference Aidt2021; Benedetto and Hix Reference Benedetto and Hix2007). We expect these factors to have a conditional impact on voting behaviour during the indicative votes.

Eight opportunities, plus another four

Indicative votes are designed to assess whether there is any policy solution that commands a majority in parliament. They mark the failure of the cabinet to provide a viable course of action and constitute a litmus test of the parliament's capacity to reaffirm its centrality. As such, indicative votes are not frequent in a Westminster democracy like the United Kingdom, and they often do not prove particularly effective. Theresa May herself was understandably doubtful in this regard: ‘I must confess that I am sceptical about such a process of indicative votes. When we have tried this kind of thing in the past, it has produced contradictory outcomes or no outcome at all’ (Hansard 2019a: 25 March, col. 24).

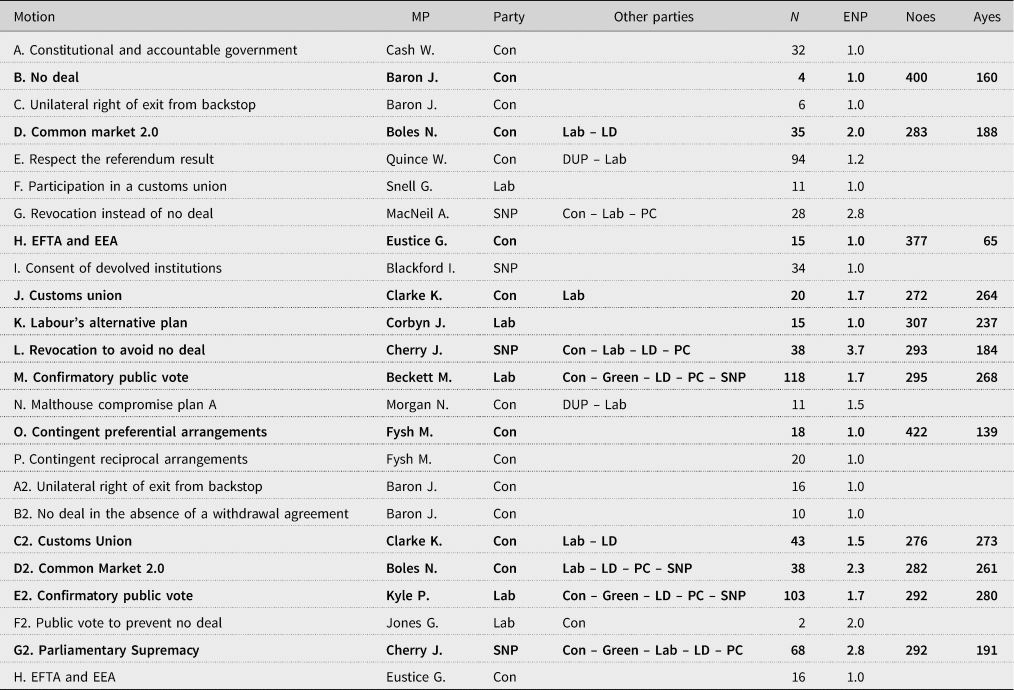

Having obtained control of the agenda, MPs presented to the speaker 16 different motions representing a broad spectrum of alternatives, ranging from an exit without a deal to the revocation of Article 50. Details of these proposals, together with those presented for the second round of indicative votes on 1 April, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Motions Tabled for the First and Second Round of Indicative Votes

Note: Bold indicates motions that were put to a division. Con = Conservative Party; Lab = Labour Party; LD = Liberal Democrats; SNP = Scottish National Party; PC = Plaid Cymru; DUP = Democratic Unionist Party.

Column 1 in Table 1 states the title of the proposal, followed by its first proponent and party group; columns 4 and 5 list the other parties and the total number of MPs who signed the motion; column 6 shows the effective number of parties that tabled the proposal, as a measure of cross-partisanship; finally, columns 7 and 8 give the number of MPs who voted against and in favour if the motion was put to a division.

In selecting the proposals for the debate, Speaker John Bercow balanced both their party origins and the representation of the entire range of opinions. At the same time, since the only chance of reaching a majority in support of any solution was to gain bipartisan support, Bercow implicitly privileged motions that had been signed by MPs belonging to different parties. The mean effective number of signatory parties is 1.6 for the eight selected motions, with an average of 33 MPs who signed them, compared to just 1.3 signatories with an average of 20 advocates for the eight non-selected alternatives. The choice was even more evident in the second round of indicative votes, when all four of the selected proposals had signatories belonging to between three and six different parties, while the four that were discarded were mostly single-party motions.

Oliver Letwin anticipated the need for cross-partisanship in the debate during which the legislature managed to modify the cabinet's business motion, noting that ‘one thing we will all have to do is seek compromise. We almost know that if we all vote for our first preference, we will never get to a majority solution’ (Hansard 2019a: 25 March, col. 82). His suggestion was not entirely disregarded by his colleagues. Almost three-quarters of the House voted for at least two different alternatives, with more than 28% voting for four or more proposals and a record case of one MP supporting all the solutions apart from the no-deal exit and the minimalist preferential agreements option. However, this effort was not enough. All eight motions were voted down in the House of Commons on 27 April, indirectly confirming the scepticism of the prime minister. Limited cross-party trust was the first cause of this failure, as shown by the data reported in Table A.1 in the Online Appendix.

As the speaker said, it was ‘not utterly astonish[ing] that after one day's debate, no agreement [was] reached’ (Hansard 2019a: 27 March, col. 462). The procedure adopted in fact favoured tactical voting, especially among those who backed a soft solution to the issue. Some MPs preferred not to support proposals that they probably considered better than a hard Brexit or May's deal, to increase the probability of a better relative positioning of their preferred option. This was anticipated by the father of the House, Kenneth Clarke, who suggested before the first round of indicative votes that ‘the single transferable vote is the best way to steer people to one conclusion. It will force compromise, except from those who will vote only for their first preference’ (Hansard 2019a: 27 March, col. 83). MP Margaret Beckett, who herself advanced one of the most supported motions, hoped to have an ordinal ballot at least in the second round, expecting that ‘we would first let 1,000 flowers bloom and see where we went … and that then we would seek to proceed to see whether ranking things in an order of importance made a difference’ (Hansard 2019a: 27 March, col. 462).

However, this outcome did not materialize, and parallel independent votes prevented parliament from obtaining anything different from the results of the first round of indicative votes also in the second round. The cross-party proposal of a confirmatory referendum obtained the highest amount of support, but it was the motion of the father of the House in favour of a customs union that came closest to success, falling short of a majority by just three votes. Clarke bitterly commented,

I have got a damn sight nearer to a majority in this House than anybody else has so far …. Three votes is quite near. We cannot go on with everybody voting against every proposition. The difficulty is that there are people who want a people's vote who would not vote for my motion because they thought they were going to get a people's vote. There were people – the Scottish nationalists – who wanted common market 2.0, so would not vote for my motion. All of them had nothing against mine. If they continue to carry on like that, they will fail …. We would lose more than we would gain. Those Members should accept that they do not have a majority yet for the people's vote and vote for something that they have no objection to as a fall-back position. That is politics. (Hansard 2019a: 27 March, col. 881)

Clarke addressed his criticisms mostly to the opposite side of the House, while Conservative Nick Boles, the proponent of the common market 2.0 motion, pointed the finger at his fellow party colleagues, eventually opting to resign from the Conservative parliamentary party: ‘I have given everything to an attempt to find a compromise that can take this country out of the European Union while maintaining our economic strength and our political cohesion. I accept that I have failed. I have failed chiefly because my party refuses to compromise. I regret, therefore, to announce that I can no longer sit for this party’ (Hansard 2019a: 27 March, col. 880).

The map of parliamentary behaviour

The primary data that we used to identify patterns of parliamentary voting behaviours were the division records for the 12 indicative votes collected online for each MP in the House of Commons Hansard.Footnote 3 An aye was coded with ‘1’, a no with ‘−1’ and abstentions or absences with 0. Assigning a nil to the last option is common practice in the literature on parliamentary voting whenever abstention is a feasible and meaningful alternative. This was certainly the case with the indicative votes that we analysed, keeping in mind that even ministers took part in the divisions.Footnote 4

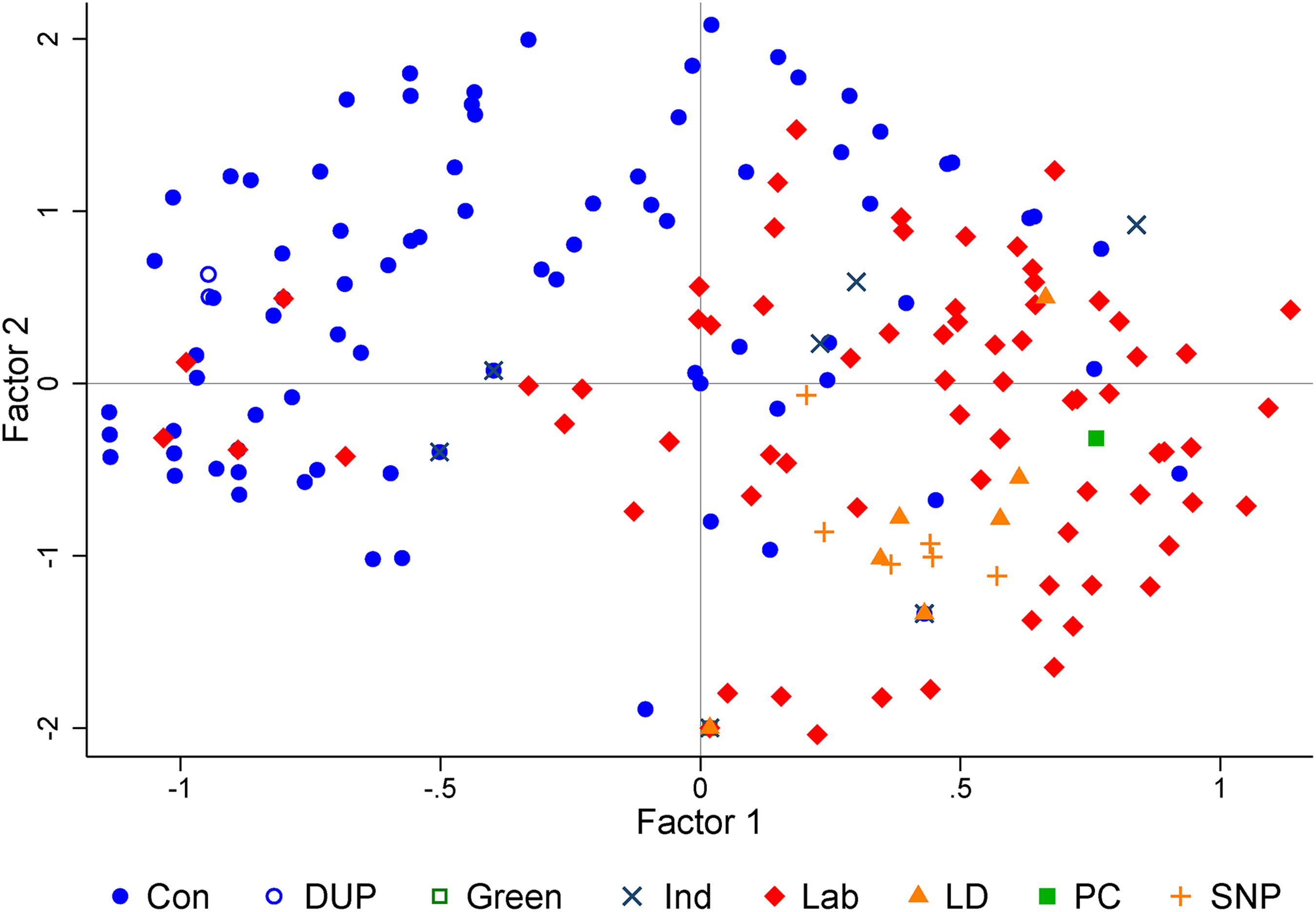

Since we wanted to explore different voting patterns, instead of the reaction to any single exit option, we proceeded by identifying the latent dimensions framing the behaviour of MPs in the 12 divisions. Given the restricted and implicitly ordinal nature of our data, we ran a factor analysis based on a polychoric correlation matrix. Retaining the factors with eigenvalues larger than 1, we were left with just two dimensions explaining more than 90% of the variation in voting behaviour. We plotted the respective factor scores of each MP on the map reported in Figure 1, where different markers are used to identify party membership.Footnote 5

Figure 1. Map of MPs on the Indicative Votes

The political space of a Westminster democracy should be characterized by a single government–opposition divide (Hix and Noury Reference Hix and Noury2015). The fact that we needed two dimensions to characterize the behaviour of MPs already shows how Brexit – and more generally all issues connected to the European Union (Wheatley Reference Wheatley2019) – involved a more complex and variegated environment. We further discuss the possible reading of MPs' behaviour as the effect of a single curvilinear space, together with its consequences for our overall interpretation, in the Online Appendix. More importantly, several MPs on both sides joined the opposite party or, rather, decided to compromise and voted in favour of more than one proposal, so that there was a visible blurring of the party line, and cross-cluster interaction was obvious and apparent (Intal and Yasseri Reference Intal and Yasseri2021). From a different perspective, although some parties also whipped their MPs on selected indicative votes, there was no homogeneous party behaviour, with unusually low indices of agreement.Footnote 6

As with any spatial representation of voting behaviours, the plotted coordinates are open to interpretation. The first dimension, on the x-axis in the map, reflects the different exit preferences and explains more than 78% of MP behaviour. On the left-hand side of the continuum are supporters of a hard Brexit, while on the right-hand side are those who preferred to reconsider the original choice with a second referendum or accept a softer departure. This first factor is also systematically associated with the number of ayes in the 12 votes (see Online Appendix), implicitly suggesting a more favourable disposition towards compromise.

The chart visually confirms what the agreement indices already suggested – that is, that this dimension does not capture the typical government–opposition divide. Despite the Labour Party whipping for some of the softer options, some of its MPs appear on the left part of the map, while a substantial portion of Conservative MPs are on the opposite side.Footnote 7 This interpretation is further confirmed in the Online Appendix by Figure A.5, which shows how this dimension is also partially correlated with the degree of flexibility exhibited during the divisions. The left side of the same map is in fact occupied by those who rigidly voted against all options or exclusively for their absolute first preference, while the right side is occupied by those who chose to compromise – that is, who voted in favour of a larger set of alternatives.

The interpretation of the second dimension, explaining an additional 13% of voting behaviour, is less straightforward. After a first exploration, we found that larger values of this second factor were also systematically associated with the support of Theresa May's exit agreement, with MPs characterized by different attitudes to the EU yet backing the prime minister's willingness to deliver Brexit.Footnote 8 Among them, for example, were the Conservative members Nick Boles and George Eustice, both also advocates of alternative projects voted in the indicative divisions, the Labour MP Ian Austin and the independent representative (originally Liberal-Democrat) Stephen Lloyd. As in the case of the previous dimension, this divide does not perfectly respect the government–opposition cleavage, although meaningful votes were most divisive for the Conservative Party.

Thus, in regard to the positions on the map, starting from the bottom-left part of the plot and moving clockwise, we encounter the following:

• Tory MPs close to the European Research Group, headed by Jacob Rees-Mogg, together with most Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) members and some Labour Brexiteers like Graham Stringer and Kate Hoey, all opposing May's agreement as well as any soft exit option or possibility of a second referendum;

• Eurosceptics preferring (or accepting) a no-deal, and yet not opposing, if not explicitly supporting, the prime minister's plan to deliver Brexit: among them, several government members and opposition MPs such as John Mann and Kevin Barron, who, like the colleagues of the previous group, rebelled twice against the party whip on a confirmatory public vote;

• Conservative and Labour Party supporters of Theresa May's agreement such as Conservative Oliver Letwin and Labour Ian Austin who, for different reasons, disregarded their respective parties' instructions and ended the legislative term as independent MPs;

• Negotiating MPs such as the father of the House, Kenneth Clark, who voted in favour of seven of the motions put forward in the 12 indicative votes and loyally supported the government's agreement but later had the whip removed by Boris Johnson; Labour MPs who opposed Theresa May and were open to a wide range of solutions, including soft exit options like common market 2.0 and more radical ones like the whipped confirmative second referendum;

• The majority of SNP MPs, together with some Liberal Democrats, who voted down Theresa May and supported only a more limited range of alternatives to her agreement;

• Conservative Remainers such as Heidi Allen and Anna Soubry, who left their party to first join the Independent group and then founded the new Change UK parliamentary group.

Covariates and expectations

As stated in the theoretical section, we expected to find some systematic pattern associated with the location of each MP along the two dimensions of the map. If the traditional government–opposition divide cannot explain those placements exhaustively, it does not mean that parties are irrelevant. Partisanship was a necessary control variable precisely because we also expected something else to contribute to MP behaviour.

To check for the influence of the socioeconomic structure of the constituency, we referred to 2011 census data.Footnote 9 The fact that our source of information dated back to five years before the Brexit referendum and eight years before the divisions that we examined was a great advantage. On the one hand, statistically speaking, these data helped avoid any risk of backward causation. On the other hand, more substantially, they made us less susceptible to short-term explanations and allowed us to establish a link with the representation of long-lasting features of MPs' electoral districts.

We retrieved data connected to the typical political geography of the United Kingdom, considering issues – such as national identity, migration and so-called ‘left behind’ groups – that have been widely regarded as associated with Brexit and electoral behaviour (Boyle et al. Reference Boyle2018; Johnston et al. Reference Johnston2018). We considered demographic characteristics such as the population density, urban structure and age profile of the district, focusing on the share of people aged between 15 and 24; identity-connected characteristics such as being born in the UK or declaring oneself to be Christian; economic characteristics such as the share of people working in the manufacturing sector, holding a routine occupation or living in a deprived household; and educational characteristics such as the share of people with a university degree.

Our expectation was that even after we controlled for partisanship, these variables would affect MP behaviour. More specifically, we expected MPs elected in urban, younger, less deprived and comparatively more educated districts to ask for a confirmatory referendum or opt for softer exit options – those represented in the right-hand part of the graph with positive scores on the first dimension. Conversely, we expected MPs elected in less cosmopolitan districts, with higher shares of voters holding manufacturing and routine occupations, with larger Christian population shares, to advocate in favour of a harder Brexit. It was less clear whether to expect any relationship with support for Theresa May's agreement, our second dimension, and we left the issue for empirical investigation.

Alternatively, the most evident expression of the specific preferences of a constituency, often mentioned in parliamentary speeches, is the district result of the Brexit referendum. Chris Hanretty (Reference Hanretty2017) estimated the share of voters who opted for Leave in England, Scotland and Wales, remedying the fact that local counting areas did not correspond to the electoral districts. We complemented these data with the results for Northern Ireland, which are directly available at the constituency level. Our expectation was obviously that the larger the share of Leavers, the more likely an MP is to be placed on the left-hand side of the map. A slightly less precise and less demanding index is to consider simply whether the Leave option prevailed in the constituency, thus reducing the original share of voters to a much simpler dummy variable.

Once again, our expectations about the relationship with the second dimension were uncertain. On the one hand, May's agreement could have been seen as the most feasible way to deliver Brexit – that is, to fulfil the expectations of constituencies that voted to leave. On the other hand, May's solution could have been seen as insufficient or the prime minister herself not entirely capable of delivering Brexit, especially if we consider her defeat in the 2017 general election. Again, we leave the relationship between the vertical location on the map and the preferences in the referendum to the empirical exploration.

Two conditional factors could partially mitigate the relationship posited above. The first has to do with the electoral confidence of representatives. The wider their electoral winning margins, the more they could diverge from the specific preferences of their principals on the Brexit issue. The second factor is related to MP seniority. Senior representatives are no less tied to their constituencies, but their authority and long-lasting relationship with the electorate could grant them a greater degree of freedom (Aidt et al. Reference Aidt2021), so that we might expect them to have positions both more extreme and more moderate than those predicted by their constituencies.

Results and some further consequences

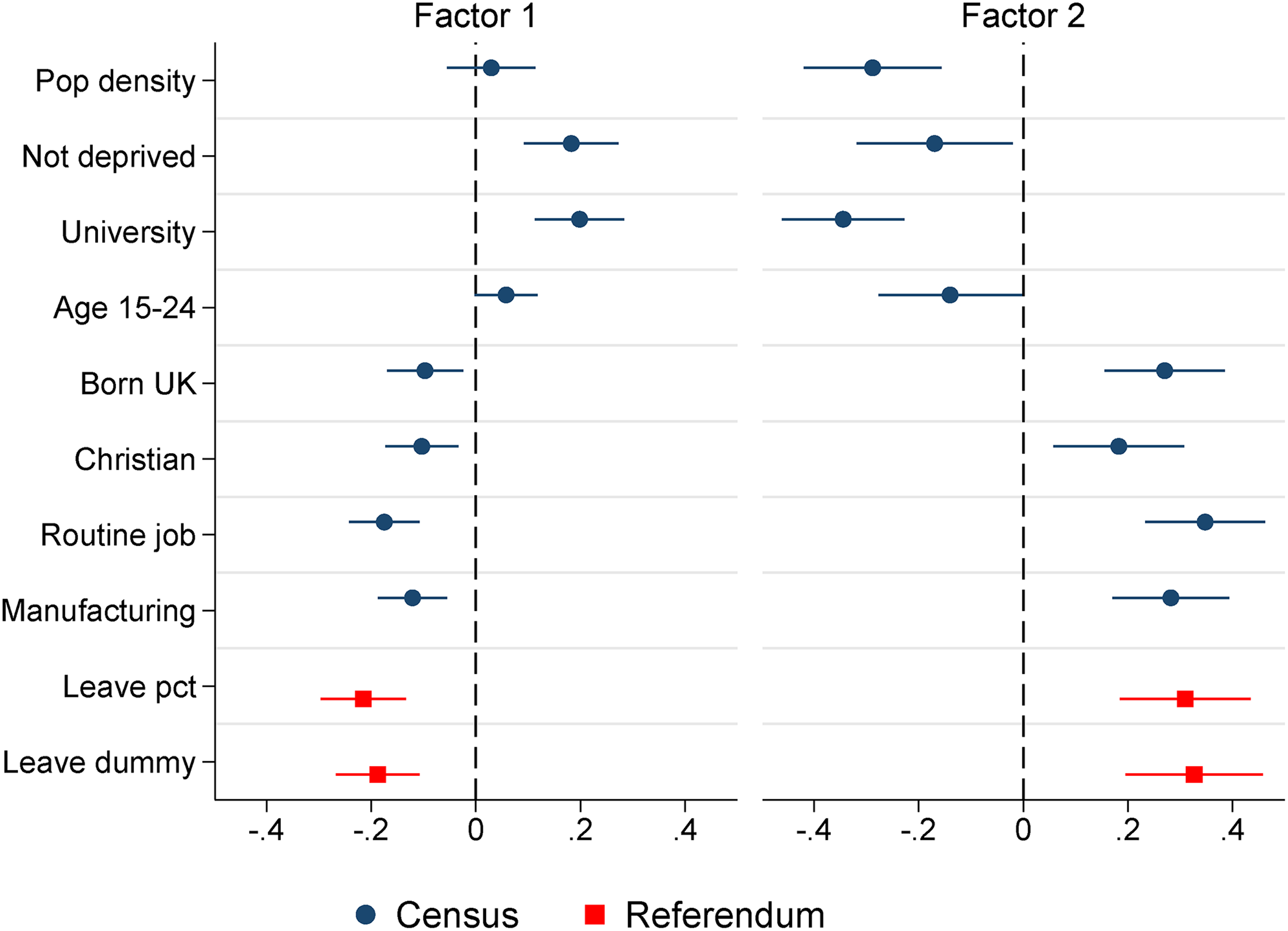

In Figure 2, we report the standardized coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for the aforementioned series of regression models, all having the party membership of each MP as a control variable and robust standard errors.Footnote 10 On the left-hand side, we evaluate the determinants of the scores on the first dimension of the previous map, while on the right-hand side we compare the corresponding values for the second dimension.

Figure 2. Regression Coefficients of Census and Referendum Data with 95% Confidence Intervals

Interestingly, regressing the two dimensions on the same set of covariates produces perfectly symmetrical signs in the coefficients, though those in the left-hand panel have much smaller confidence intervals that reflect more robust evidence and a much larger explained variance (on average 72%, compared to only 10% for the models on the second dimension).

Our data confirmed the contrast between younger, educated and relatively more affluent constituencies, and – to use the now popular image – left-behind and more traditional districts shaken by globalization on the other (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018). These results corroborate the expectations we had regarding the MPs' position on the first dimension, as well as the significance of the integration–demarcation conflict structure, with its twofold economic and cultural logic (Grande and Kriesi Reference Grande, Kriesi and Kriesi2012). At the same time, they suggest that the socioeconomic structure of the district seems to be associated, though less robustly, also with MPs' attitudes to the prime minister's effort to deliver Brexit.

Highly significant is also the more proximate effect of the referendum results on MP behaviour. Interestingly, it is not just the black-and-white impact of a Leave or Remain result that matters; it is also the degree of the respective victories that has a proportionate influence on the more or less radical positions advocated by constituencies' representatives, and on the support given to the original exit agreement in the three meaningful votes.

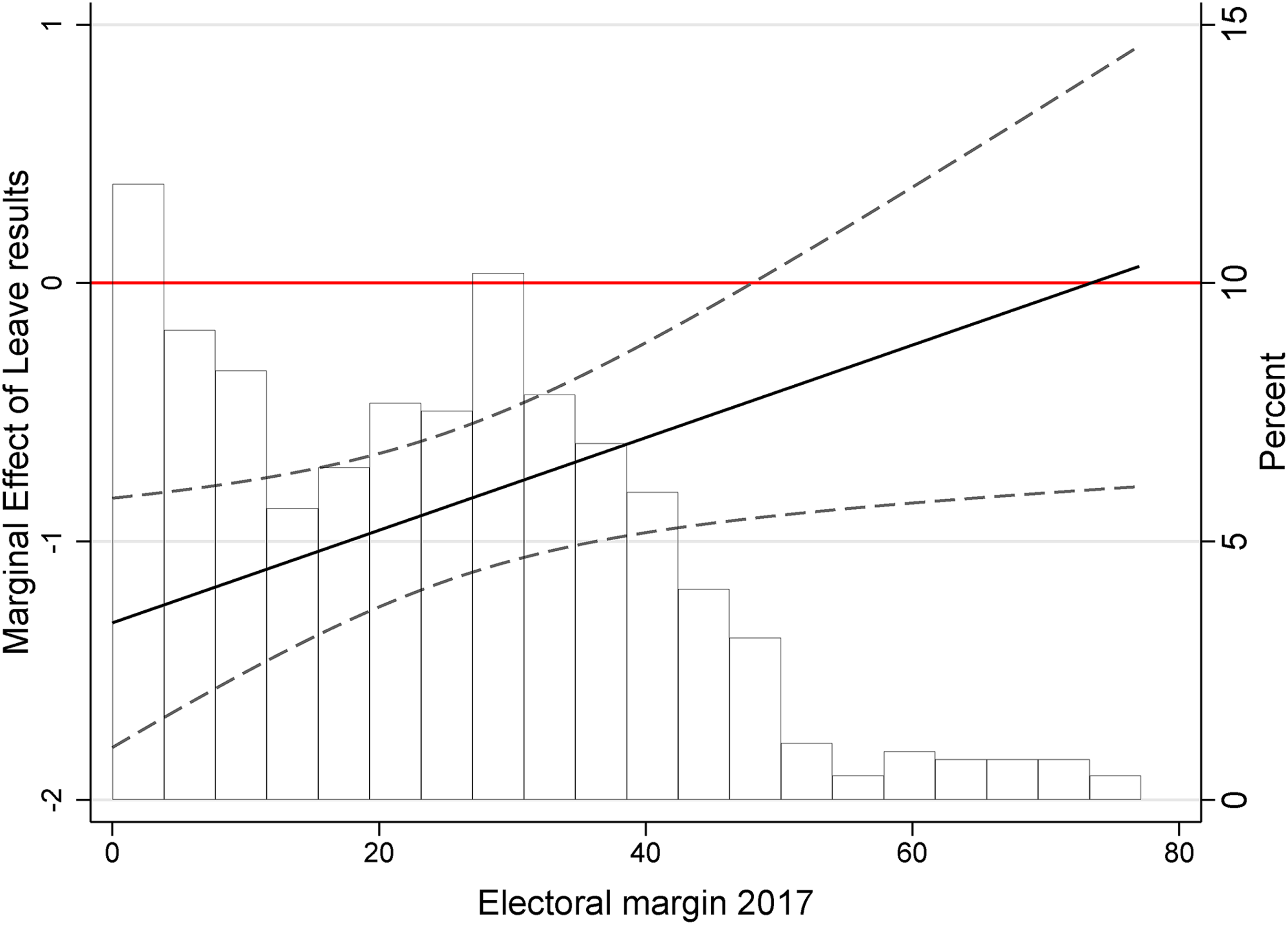

Focusing solely on the models with larger explanatory potential and robust evidence – those regarding the first dimension – we evaluated the confounding effect of parliamentary seniority and electoral uncertainty in two different ways: by conducting a heteroskedastic regression, with the variation around the mean modelled by the year of an MP's first election and the electoral margin, and by interacting the two factors with the share of Leave voters. We report the full results in the Online Appendix, although what we found confirms that senior representatives enjoy greater behavioural freedom, acting more as trustees than as delegates. Furthermore, the influence of the constituents' Brexit preferences decreases, and eventually stops being relevant, the larger an MP's electoral margin against the closest contender in the preceding 2017 election (see Figure 3). The likelihood of a re-election is confirmed to be another factor favouring free agency.

Figure 3. Marginal Impact of the Share of Leave Votes on MPs' Scores on the First Dimension at Different Degree of Electoral Certainty (Winning Margin in 2017), with 95% Confidence Intervals

To come full circle, we needed to complete the final step of our analysis. Since the 2019 general election was called because of the Brexit saga, and de facto closed it, what were its consequences for the positions advocated during the 12 divisions under consideration (Axe-Browne and Hansen Reference Axe-Browne and Hansen2021)? The election was an undisputed success for Boris Johnson's strategy and a landslide victory for the Conservative Party, with ‘Brexit fundamentally reshap[ing] the nature of electoral competition’ (Prosser Reference Prosser2021: 10). It also demonstrated the diverse capacities of the two major parties to adapt to the changing post-referendum political environment (Hayton Reference Hayton2021). Our data enabled us to take a closer look at this issue from the perspective of the relationship between each representative and his or her constituency.

Since we confirmed that the behaviour of MPs was systematically linked to the exit preferences of their constituencies, were there any consequences for having somehow betrayed them or for having taken a more compromising attitude during the indicative votes? While the former question can also be answered simultaneously for all legislators, testing the hypothetical impact of non-responsiveness on support for the 2017 district incumbent, the effect of compromising behaviour needs to be checked separately for each party. Because only two parliamentary groups satisfied the minimum number of observations required for a statistical analysis, we restricted this latter investigation to the two major parties.

Compromise was effectively captured by the first dimension of the map of MPs' behaviour, whereas we measured the lack of responsiveness by taking advantage of the residuals of the regression model plotted in Figure 3. The larger the residuals – that is, the less our main covariates (including partisanship and referendum results) are able to explain the representative behaviour – the more the constituency's preferences were somehow ‘betrayed’.Footnote 11 We then regressed the 2019 district results of the incumbents on our measures of responsiveness and compromise using a set of control variables: the estimated proportion of Leave votes, to keep the original exit preferences of each constituency constant; the electoral margin in the previous election, to capture any strategic incentives for MPs in districts with slim majorities; and the change in turnout at the district level, to evaluate the potentially mobilizing/demobilizing effect on the electorate of the lack of responsiveness or willingness to compromise displayed by MP behaviour (Cutts et al. Reference Cutts2020).

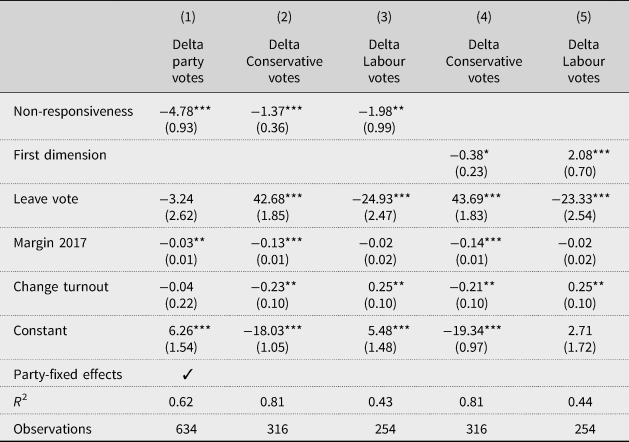

According to Model 1 presented in Table 2, a lack of responsiveness on Brexit was systematically sanctioned among all MPs in the 2019 general election. A set of post-estimation diagnostics confirm the absence of omitted variables and the correctness of the model specification. The effect is confirmed also in Models 2 and 3, limiting the analyses to the subsets of Conservative and Labour groups, with the cost of non-responsiveness being larger for the latter. The negative effect of the ‘betrayal’ was counterbalanced by the Leave preferences in the Conservative districts, while it was reinforced by that same factor in Labour constituencies. Interestingly, all other things being equal, increasing turnout depressed support for the incumbent party in Conservative districts while boosting it in Labour districts, whereas electoral uncertainty played a role only in the former ones.

Table 2. The Electoral Costs of Non-Responsiveness and Compromise

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Regarding the cost of compromise, Models 4 and 5, the party differences are also striking. For a Labour MP, to embrace several alternatives was coherent with the party line, even though not all of the options were whipped by party leader Jeremy Corbyn, so that voting in favour of multiple exit options was eventually positively welcomed by the respective constituencies. With a weaker statistical significance, the opposite occurred for Conservative MPs, for whom supporting multiple options proved electorally detrimental (Alexandre-Collier Reference Alexandre-Collier2020).Footnote 12

Conclusion

The Brexit parliamentary process, with its government defeats, backbencher rebellions and cross-party bargaining, has been rather unusual for a Westminster democracy. Even in that extraordinary period, MPs did not act randomly on the basis of some inexplicit personal belief. They interpreted their role as representatives reflecting the structural features of the district in which they were elected, and the more proximate preferences expressed by their constituencies during the Brexit referendum.

Recalling the categories proposed by Eulau et al. (Reference Eulau1959), many MPs acted as ‘politicos’, behaving as local delegates when their choices reflected the results of the referendum, but also as local trustees when they further interpreted what should be in the interest of their constituents. Some senior representatives, or MPs elected in safe districts, allowed themselves to shift the focus of their representative role towards a larger public, choosing to distance themselves from the pressures and needs expressed by their electoral districts, in the name of some superior interest of the country. We further demonstrated how the positions that MPs advocated were later connected to their electoral performance in the 2019 general election with, ceteris paribus, less responsive legislators on the crucial Brexit issue being punished in the ballot.

The fact that political divides did not follow the usual government–opposition pattern throughout these events was certainly not indicative of a weakness in the British political system. In fact, the good news is that the legislators mostly remained responsive to their constituencies, even when they decided not to follow the party whip and compromised with MPs from the other side of the House. On average, they remained faithful to their main electoral principals, trying to accommodate their preferences within a party government framework, something that confirms previous findings by Hanretty et al. (Reference Hanretty2017).

The fact that MPs refrained from following the norms of the usual adversarial disciplined politics does not entail that they massively adopted the more cooperative style that has sometimes been invoked as a solution to the Brexit stalemate. The failure of the 12 indicative votes clearly indicates a lack of familiarity with those cooperative dynamics, starting from the choice of voting procedures. It is probably fair to say that if the parties had more experience with consensual practices – that is, if they had been more used to compromising to avoid the worst outcomes – the story might have had a different outcome.

There is no obvious counterfactual, and it is still unclear if this unusual period will have political aftershocks or if Johnson's landslide victory will complete the restoration of more traditional Westminster dynamics (Baldini et al. Reference Baldini2021; Giuliani Reference Giuliani2021). The swift parliamentary approval of the exit agreement immediately at the beginning of the new legislative term seems consistent with the second hypothesis, and yet the fact that MPs' behaviour can be explained by structural features of their constituencies measured almost a decade earlier suggests a more cautious position may be warranted. Indeed, we agree with those who see Brexit not as a hiccup in the normal dynamics of a majoritarian democracy, but as ‘the expression of conflicts which have been building in the electorate for decades’ (Sobolewska and Ford Reference Sobolewska and Ford2020: 1), and the choices of the representatives during the indicative votes reconnect them better to those deeper multifaceted issues revealed by the exit process.

If this interpretation is correct, a more cooperative approach may even be useful for a resolute prime minister like Boris Johnson, and for British politics at large (Richardson Reference Richardson2018). In fact, the head of government did not unilaterally cut the Gordian knot of the deal between the United Kingdom and its former EU counterparts in December 2020, as he did internally one year previously by calling a snap election. The agreement required some give and take and a compromising attitude: the same kind of attitude that, since then, has been required for its implementation, whether it be on fishery issues, diplomatic representation, vaccine export or the revision of the Northern Ireland protocol. Moreover, the constitutional tensions exposed during the process have not been cancelled by the 2019 election results (Blick and Salter Reference Blick and Salter2021); in this regard too a less assertive and adversarial policymaking style could help.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.61

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors and the three referees of the journal for their useful and accurate comments. I presented a first analysis of Brexit divisions in the 2019 annual conference of the Italian Political Science Association, and the suggestions received on that occasion helped me to better reframe my argument.