Our troubles are too much with us. Battles over who counts as a citizen, who, if anyone, deserves protection from abject poverty, how to handle affirmative action, what to do about racial wealth gaps, and what to do about predatory financial practices animate our public and private debates. Yet though such discussions may seem recent, we researchers in social science and history know that the problems of late came soon, unfolding over a long period. What can an interdisciplinary approach to studying the past tell us about how we got here and where we might go? What can it reveal about the pathways to disadvantage and how their course can be altered?

This presidential address will walk a well-worn path. Eighty-two years ago, Robert K. Merton revisited history in his essay “The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action” (Reference Merton1936) to demonstrate why expected outcomes sometimes fail to materialize, and why thoughtful plans to eliminate disadvantages can instead exacerbate them. Merton’s approach epitomized a contrarian regard for the workings of social life and warned against our attempts to rationalize them. Sixty-four years later, Alejandro Portes (Reference Portes2000: 3) revived Merton’s framework in “The Hidden Abode,” reminding us to look, as Karl Marx did, “behind the appearance of things” so that over time we could observe how social realities emerge, are modified, and sometimes take unexpected turns before hardening. Just a few years before Portes revived Merton, however, Charles Tilly challenged Merton’s view. In “The Invisible Elbow,” he (Reference Tilly1996: 592) applauded Merton, noting that his approach to unanticipated consequences “struck a resounding gong” but “only played half the tune … [because he had] left untouched the problem’s other half: how purposive social action nonetheless produces systematic, durable social structure.” For Tilly, it was the set of social relationships (evident in network structures) and the power of culture, rather than situational idiosyncrasies and constraints on rationality, that made the paths to disadvantage so durable and bedeviling.

Culture is a powerful driver of disadvantage, to the extent that we know it when we see it (Lamont, Beljean, and Clair Reference Lamont, Stefan and Clair2014). Historical records capture culture “externalized in the form of public symbols and discourses” as well as in narratives and classifications (Lizardo Reference Lizardo2017: 93). Indeed, “every nation has a story—a public narrative it tells to explain its place … in the flow of history … and to give meaning to its economic policies and practices” (Somers and Block Reference Somers and Block2005: 280). Institutions and groups of individuals orient their actions in line with, or as a barrier against, these narratives and classifications even when the actors have no consistent understanding of what the narratives mean or how the classifications should be applied. These “rules of social life” are cultural schemas that sometimes become codified as rules (that can be disadvantaging) or at other times as guidelines for behavior that do not require the force of state law for their recognition or their enactment (Sewell Reference Sewell1992). Margaret Somers and Gloria Gibson (Reference Somers, Gibson and Calhoun1994: 3) note, for example, that “stories guide action; that people construct identities (however multiple and changing) by locating themselves or being located within a repertoire of emplotted stories; that ‘experience’ is constituted through narratives; that people make sense of what has happened and is happening to them by attempting to assemble or in some way to integrate these happenings within one or more narratives.”

In his comparison of the way in which the United States, Britain, and France forged their railroad industries between 1825 and 1900, Frank Dobbin too argues that “national traditions influence policy-making by contributing to collective understandings of social order and instrumental rationality. History has produced distinct ideas about order and rationality in different nations, and modern industrial policies are organized around those ideas” (Dobbin Reference Dobbin1994: 2). The same can be said for policies that affect labor, education, and social policy, among other things. Inheritance laws likewise vary from country to country, due not to a technological or material imperative, but rather to the set of meanings (evident in stories) over which actors struggle and the privileges they seek to effect (Beckert Reference Beckert2008). Likewise, economic knowledge proves to be subject to societal dynamics, as societies affect the discipline of economic science while that discipline reshapes the societies where they reside and those to which they are otherwise tied (Fourcade Reference Fourcade and Healy2009). In short, when actors develop, defend, or attack policies that have disadvantaging distributional effects on the already disadvantaged, they must contend with the narratives that make sense of these policies. Such contentions often unfold in the public sphere (Bandelj, Spillman, and Wherry Reference Bandelj, Spillman and Wherry2015).

As the story of disadvantage is played out in the public sphere, we witness deception, plot twists, and dramatic irony. Not all the characters populating it, however, carry the same moral weight. Some social characters (or population subgroups) are said to be different from “the normals” in a disqualifying way; they are discredited. Others need to manage their difference, acting as though it were irrelevant to their relationship with “the normals” or as though their differences are not immediately apparent and that they can therefore “pass.” Their social status as “discreditable” rather than “discredited” offers them affordances, the ability to apply for roles that might place them in advantageous jobs or neighborhoods. The situation of the discredited, however, leaves them vulnerable to “justifiable” deceit or unlucky turns of events; the general public (“the normals”) will not cry out for justice for those who possess a stigma—“an undesired differentness”—that renders them “not quite human” and a danger to the rest (Goffman Reference Goffman1963: 2). These processes now play out in the receipt and use of a credit rating (a credibility score) that has severe implications for the life chances of individuals and the communities where they live (Fourcade and Healy Reference Fourcade2013; O’Brien and Kiviat Reference O’Brien and Kiviat2018; Wherry, Seefeldt, and Alvarez Reference Wherry, Seefeldt and Alvarez2019). A new humanizing vocabulary may do the work of crediting the disadvantage; so too may the separation of the discredited from the others to affirm a different basis for credibility. With all the world a stage, casting and performance matter.

There are more explanations for how some are cast in a more disadvantageous position compared with others than I can provide here. Yet those I discuss in the following text are the ones most likely missing from or misunderstood by readings of history that treat stigma—particularly as it pertains to race—as either incidental or an epiphenomenon of a more important materialist dialectic. I begin first with the ways in which deception deepens inequality. I then turn to the question of how disadvantages emerge in midcourse with new, unanticipated distributions of resources, sanctions, and opportunities. Next I examine the role of rules in deepening disadvantage, before examining how organizational processes generate isomorphic inequalities. (By mimicking what other policy commissions around the globe are doing about the same social problem, policy makers can worsen inequalities in their own country.) Finally, I interrogate how unlucky turns of events depend on more than mere chance to make disadvantages durable. My presidential address concludes with the implications for reparations and social repair.

Disadvantage through Deception

Deception is the act of convincing someone to accept as true something that the deceiver knows to be false. Deceptions range from hiding one’s intentions and capacities to double-dealing and outright fraud. When individuals deceive, they rely on narratives not only to accomplish the deception but also to justify to themselves and to their socially significant others why they needed to behave in ways generally perceived to be dishonorable. The deceiver performs a dramaturgical role in the narrative and may well believe in the part that she is playing (Goffman Reference Goffman1959)—a part that may come with an idle boast, a false show, a big little lie, or worse. These stories about the motives behind deception and the forms that such deception takes help deepen disadvantage by providing cover for fraudulent actors while stigmatizing the deceived or “empowering” the duped by insisting on their freedom to choose.

Deception is rife in economic and political life, but it is not framed as a path to disadvantage. Consider Uri Gneezy’s classification of lies based on their consequences: (1) lies that benefit both sides (no harm done); (2) lies that are neutral for the liar but benefit the other side (euphemisms, “little white lies,” and altruistic outcomes); (3) lies that can harm both sides, often motivated by “a spiteful reaction to unfair behavior” (Gneezy Reference Gneezy2005: 385); and (4) “lies that increase the payoff to the liar and decrease the payoff to the other party” (ibid.). According to this formulation, spiteful reactions to unfair behavior occur against racially unspecified, ahistorical others. Furthermore, historically constructed identities do not justify acceptable harms, and the salience of identities is not manipulated (or compared) to demonstrate whether some liars are more likely to face sanctions than others by virtue of the identities rendered salient in the deception.

By contrast, I reformulate the role of deception in deepening disadvantage to demonstrate that community-level meanings matter. First come deceptions that have no manifest intention to harm the deceived. These “white lies” include the policy of praising students for work well done when that work is below average. While these may make students feel good about such positive feedback, they may suffer from disappointment when trying to use their acquired credentials in an environment that judges them harshly. The intention of such deception depends on the salience of the student’s identity: Is she creditable as a student, as someone able to learn, or has she been written off as beyond reform? Judgments such as these build up over time, are shared across a community, are believed to be more relevant to some identities than others, and are ultimately consequential for maintaining disadvantage.

Second, imagine a scenario in which the deceiver harms the deceived but does not benefit from the deception. In such a case, the deceiver may believe that her deception will benefit the total welfare of society (“for the greater good”). This occurred with the policy of forced sterilization, which targeted African Americans and immigrants, who were viewed as the categorical opposites of Scandinavians (characterized by “chastity” and “self-control”) and Germans (typically “thrifty,” “intelligent,” and “honest”) (Bruinius Reference Bruinius2007). When Charles Davenport established his laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, he believed that he was working for the greater national good as he attempted to promote “good genes” and to slow the spread of bad ones. President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) established and charged the national “Heredity Commission” (1906) with this very objective. Davenport was also a member of the American Breeders’ Association and convinced the association to set up a Eugenics Section that included among its members Alexander Graham Bell, David Starr Jordan (the president of Stanford University), and other respectable members of the scientific community. (The Eugenics Section, in fact, served on the Heredity Commission.) Those promoting sterilizations (sometimes without the consent or knowledge of the sterilized) and others who conducted experiments on the dissemination of disease (e.g., the Tuskegee syphilis experiments conducted on African American men), targeted social identities that were socially discredited and therefore regarded as disposable by scientists. With recent advancements in the social life of DNA (Nelson Reference Nelson2016), such identifications of the unfit and their suppression for the greater good may not be that far in our future (Duster Reference Duster2015; Panofsky and Bliss Reference Panofsky and Bliss2017; Reardon Reference Reardon2017). Across these cases, the benefits to the many have been used to justify the disadvantages imposed on the “unfit” few.

Third, the deceiver knowingly imperils her own welfare and that of the deceived, perhaps out of hatred, spite, or resentment. Believing that she has been wronged and that she lacks the institutional means of redress, or else that the state of the world is unfixable due to a misbehaving group, the deceiver puts a curse on both houses, deepening existing problems while creating new ones. Imagine a person trapped by invaders in her own home. The outsiders have entered out of necessity and assured her that they will only take a few things and will leave her and her family alone. These outsiders have a reputation for staying true to their word, but she finds their behavior outrageous and their persons objectionable. She may decide to set the house on fire from the inside with the doors barred, knowing that neither she nor her family will survive the conflagration.

The extended metaphor of “a curse on both houses” applies well to the history of international migration to the United States. Establishing policies that make migrants feel unwelcome leads to what Portes and Rumbault (2006) define as a process of dissonant acculturation in which the children of immigrants are more likely to be socialized into “underclass roles” in the new society and adopt adversarial stances toward mainstream societal norms, goals, and institutions. If that same set of immigrants meets with a favorable reception, their children are more likely to embrace mainstream norms and institutions. By adopting policies that treat immigrants as outsiders who cannot acculturate to a new society, policy makers forge the very attitudes and behaviors that they most fear (Portes and Rumbaut Reference Portes and Rumbaut2006). Worse yet, when confronted with evidence indicating that these policies will lead to the very outcomes that they are designed to prevent, the policy makers who evaluate the evidence as well as the voters supporting them may demonstrate a willingness to damn their own side to ensure the downfall of the other.

Finally, individuals deceive others to benefit themselves and thus, unsurprisingly, push them down the path to disadvantage. The deception occurs alongside narratives justifying it. It is neither naked greed nor cold calculation that motivates the deceivers or protects them from any moral sanctions established by socially significant others; they need something more—a way of performing a morally upright role, no matter how close it is to the margins of the unseemly. If the deception is legally permissible and the deceived are discreditable, the path to disadvantage may be accelerated (Wherry, Seefeldt, and Alvarez Reference Wherry, Seefeldt and Alvarez2019). In 1973, for example, a debate ensued in the California state assembly over whether car dealerships were engaging in deceptive advertising that disadvantaged the Spanish-speaking community. The dealerships were posting billboards in Spanish and sending Spanish-language mailings to homes where they expected to find Spanish monolinguals. After attracting these potential consumers to their dealerships, however, the dealers did not provide them with a Spanish-language version of the loan terms, and were not required to do so, even upon request. What was happening in the case of auto loans was also happening with home mortgages. As a result, these minority consumers were deceived into overpaying for the same goods and services, while experiencing greater risks of repossession (Carrillo Reference Carrillo2008).

Although State Assemblyman Richard Alatorre introduced a bill to end these deceptions, Governor Ronald Reagan initially vetoed it. As the governor explained, “[A] significant number of television, radio, newspapers and other businesses would be forced by financial considerations to eliminate their Spanish-language advertising in the Spanish-language media” (quoted in ibid.: 11). By 1974 the legislature had developed a bill that the governor was willing to sign: the California Civil Code section 1632. While eliminating language-based deception in the case of auto purchases, it left the practice untouched for mortgages and home equity loans. The legislative solution was as good as none at all: buyer beware. The discredited consumer presumably got what she deserved (Wherry Reference Wherry2008).

In war there is a good and bad side—a symbolic opposition that clarifies which side gets its just deserts (Alexander Reference Alexander2013; Smith Reference Smith2010). During World War II, the Allies deceived the Germans into believing that Allied forces would assemble in Calais. The ruse worked; the Allies surprised and overwhelmed the Germans in Normandy on D-Day. Misrepresenting their intentions was necessary to place the Germans at a disadvantage and make D-Day possible. Each side was sending signals, aware that the other side would be suspicious of whatever signals it received (Crawford Reference Crawford2003). While this example sets in contrast the signals sent between enemies, one could imagine a longer-term scenario in which each side feigns friendship over an extended period, building up trust one day to betray it (Sobel Reference Sobel1985).

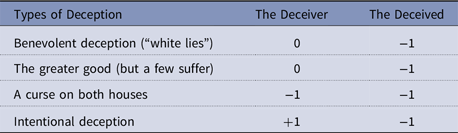

In sum, the way deception leads to disadvantage differs as much by the motive of the deceiver as it does by the social identity of the deceived: (1) the deceiver’s motives are well-meaning; the deceived is discreditable; (2) the deceiver’s motives are malicious or mercilessly rational; the deceived is discredited; (3) the deceiver’s motives are malicious; the deceived is discredited; and (4) the deceiver is instrumentally rational but not apparently malicious; the deceived are discreditable or already discredited. Finding deception in historical records can be difficult, in part because an individual’s written account may run counter to their observed behaviors; as they talk of social equality, they engage in privileges that put others at a disadvantage (Khan and Jerolmack Reference Khan and Jerolmack2013). Deceivers can believe deeply in the parts they are playing (Goffman Reference Goffman1959). Table 1 summarizes how deception leads to disadvantage for the deceived as well as sometimes for the deceiver.

Table 1. Deception and disadvantage, benefits and harms by type

Midcourse-Emergent Disadvantage

The goals of policy makers can change in the middle of enacting a policy, affecting the shape, timing, and severity of a disadvantage. Let us take what we now call affirmative action, for example. This policy neither began nor was implemented in a straightforward manner, and thus resulted in unanticipated turns for its supporters and its detractors. As Anthony S. Chen reminds us in The Fifth Freedom (Reference Chen2009), many roads were available but not taken in the promotion of fairness. Before “equal opportunity” became an important cultural resource for the promoters of affirmative action, the cultural codebook for activists centered on “fair employment practices.” According to Chen (ibid.: Loc 209 of 6295):

The court-based regulatory system in place today—of which affirmative action forms a small but controversial part—was never the sole historical possibility. Years ago, key numbers of policymakers sought statutory authority for a very different form of government involvement in which the equal treatment of individuals in the labor market—and nothing more than equal treatment—would be enforced through an administrative process based in the executive branch, with the courts playing only a supporting rather than a primary role.

In its original formulation, rather than having litigants fight employment discrimination in courts, an agency similar to the National Labor Relations Board was to have the power to order employers and unions to stop engaging in racial discrimination against individuals and to mandate compensation for individuals who had been economically harmed by discriminatory practices.

As a wide range of actors fought over fair employment legislation, new cultural resources became available and new ways of formulating the problem along with unexpected points of contention emerged amid the unfolding interactions. The most generative years were probably those of the Truman administration, when Congress came closest to taking legislative action. Nonetheless, things did not turn out as planned. A coalition of Southern Democrats and conservative Republicans succeeded in obstructing the passage of the Fair Employment Law and thus paved the way for a policy that they were to loathe even more, namely, what would eventually come to be known as affirmative action. At the same time, conservative opposition to fair employment practices in the states allowed new political vocabularies to enter the fray, changing the course of disadvantage. It was during the fight over New York State’s law in 1945 that conservatives learned to accuse liberals of promoting racial quotas even though these were nowhere to be found in the letter of the law.

Consider this: the historical sociologists Nicholas Pedriana and Robin Stryker explain the evolution of affirmative action as the result of different interpretations of equal opportunity, with narratives and counternarratives on the fairness of repair versus the unfairness of an “unnatural” equality. These narratives served as the cultural resources used by the courts and policy makers as they developed federal contracting employment policies. Recognizing that “policies, once enacted, restructure subsequent political processes” (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992: 58), Pedriana and Stryker (Reference Pedriana and Stryker1997) demonstrate how actors can use cultural resources to shift a policy’s direction in midcourse.

At the beginning, an anchoring policy affects the administrative capacities of the state. Those who are kept out of the implementation process, or who see themselves as disadvantaged by the policy, begin to reassess their capacities, their intentions, and their social identities as the policy unfolds. Its initial implementation feeds forward, placing problem solving on a structured but contestable path. This unfolding process gives way to goals and capacities not initially envisioned.

In their analysis of affirmative action, Pedriana and Stryker (Reference Pedriana and Stryker1997) have focused on Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, known as the “equal employment opportunity” title. They note that the term “affirmative action” as initially expressed in Executive Order 11246, was “seen as an unproblematic boiler plate phrase expressing the courts’ ordinary equitable/remedial powers” (ibid.: 650). Anthony Chen confirms that affirmative action “originally referred to administrative orders requiring employers or unions to hire, reinstate, or promote individual workers who were the proven victims of discriminatory behavior” (Chen Reference Chen2009: loc 246). How then did it become a set of plans that employers and unions had to write down as part of their bid for federal contracts, while specifying the ways in which they were guaranteeing equal opportunity and nondiscrimination?

Pedriana and Stryker center their analysis on the 1969 Philadelphia Plan, developed between 1967 and 1969, the final revision of which Jill Quadagno (Reference Quadagno1992) described as “the first effective use of affirmative action to implement civil rights legislation directing employers to guarantee equal employment opportunities” (Quadagno Reference Quadagno1992: 629, quoted in Pedriana and Stryker Reference Pedriana and Stryker1997: 635). The 1969 plan focused on goals, hiring ranges, and “good faith efforts.” Senator Ervin, a Democrat from North Carolina, led the 1969 hearings on the Philadelphia Plan, which framed the national narrative on affirmative action. These narratives were among the cultural resources used “to define the future reach of federal equal employment law” (Pedriana and Stryker Reference Pedriana and Stryker1997: 660) to create new forms of disadvantage while attempting to rectify existing ones.

Had the Philadelphia Plan been more focused on individuals rather than classes of individuals, it may have proven more palatable in the long term. For example, the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission (EEOC) began with an emphasis on case-by-case claims of discrimination, but because the NAACP and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) complained about the inadequacy of treating a collective issue as if it were a private one, and the EEOC did not have adequate staffing to deal with the mounting case load, new organizational intentions emerged. As Pedriana and Stryker point out, “The EEOC realized it would be more efficient and effective to target widespread industrial practices that affected large numbers of minorities” (ibid.: 651).

The apprenticeships that fed into union jobs unfairly disadvantaged blacks, who, in 1960, amounted to less than 1 percent of the building trades union membership (Quadagno Reference Quadagno1992). This put labor unions in the awkward position of supporting Democratic Party policies in general, but finding that they were now the target of corrections. The unions cried foul. With race quotas in place, what would happen to the existing seniority system? How would changing the pipeline of apprentices undermine the power and the solidarity of the unions?

Realizing that the coalition among employers, organized labor, civil rights groups, and federal government advocates was beginning to fray, the Johnson Labor Department desisted. The troubles now confronting Democrats were too good to be left alone, however, so under Nixon, the Labor Department restarted the program. The president splintered affirmative action supporters by making the lessening of inequality necessarily disadvantageous. In a scenario in which infighting within the coalition ensued, supporters were transformed into saboteurs. As we shall see in the following section, rules promoting equality can be transformed into the bulwarks of inequality.

Rule-Based Disadvantage

The legal scholars Nicholas Bagley and Eli Savit would have none of it. In May 2018, they wrote a searing editorial in the New York Times decrying the racial disadvantages to which Michigan’s new work requirements would lead. The state legislature had inserted a work requirement for anyone applying for health insurance through Medicaid, but unemployed whites had a better chance of being exempted from it than did unemployed blacks. Why? Because more whites lived in counties with an unemployment rate greater than the proposed 8.5 percent cutoff specified by the law. In fact, Michigan’s three largest cities—Detroit, Muskegon, and Flint—with overwhelmingly black populations, were ineligible for the waiver. Flint, for example, is located in Genesee county, which has an overall unemployment rate of 5.8 percent. Yet the city of Flint has an unemployment rate of 10.4 percent, so its residents would have to work, or else. Bagley and Savit warned that though the new rule appeared to be race neutral, it would have a “discriminatory effect on individuals because of their color.” Somehow, the disparate impacts had not been acknowledged by those proposing the policy.

Bradley Hardy, Trevon Logan, and John Parman (Reference Hardy, Logan, Parman, Shambaugh and Nunn2018), in turn, used the case of Michigan Senate Bill 897 to illustrate how rules that appear to be neutral may deepen racial inequalities. In the Midwest, they note, 96 percent of blacks live in metropolitan areas as compared to 75 percent of whites. In some states, such as Michigan, the unemployment rate in nonmetropolitan areas is higher than in metropolitan areas. Thus rules based on a single, “neutral” metric (unemployment rate) prove to be nonneutral in the outcomes they facilitate and thus amplify the effects of higher unemployment on racial minorities. These racial disparities depend greatly on the rules that often cloak the mechanisms of disadvantage (Flynn et al. Reference Flynn, Holmberg, Warren and Wong2017).

Work requirement rules have a long history of disadvantage. In The Invention of Free Labor (Reference Steinfeld1991), Robert Steinfeld reminds us that labor law in the American colonies and in seventeenth-century England allowed the imprisonment of workers who left their places of employment before the agreed upon period of the work contract. Even after indentured servitude ended in the United States, employers maintained indirect legal control over those they employed. Other scholars studying cases across the globe have observed that vagary laws prevented potential workers from withholding their labor, even when they were “free” to withhold it. The choice was to work or be jailed. The potential laborers did not engage in invidious comparisons of economic advantage between themselves and those who had jobs. Instead, the economic, political, and cultural institutions of powerful countries and the dominant class of capitalists they represented penetrated the lives of those on the periphery. In South Africa, a new, state-imposed poll tax that had to be paid in legal tender meant that villagers who wanted to retain their own economic arrangements could no longer both do so and pay the taxes that would allow them to remain on their lands. Instead, they had to work in mines (Portes and Walton Reference Portes and Walton1981). The number of disadvantaging rules we could cite are many, so let us turn to those whose effects stretch well beyond their intentions.

Rules meant to keep groups apart have made them more likely to experience violence when they come into contact. Between 1882 and 1930, for example, blacks in the United States were more likely to be lynched in areas with higher racial residential segregation. This finding was by Lisa Cook, Trevon Logan, and John Parman (Reference Hardy, Logan, Parman, Shambaugh and Nunn2018) based on their use of the Logan-Parman measure of segregation, which assesses intergroup contact according to the aggregation of adjacent residences (by race) rather than the proportion of households of each race in a given census tract as do the indices of dissimilarity and isolation. Cook and her collaborators argue that because lynching occurred largely in rural areas, urban-based measures of segregation needed to be replaced by a more appropriate measure of racial integration. Based on data from the Historical American Lynching Project (1882 to 1930), they concluded that: “Understanding the relationship between segregation and racial violence in America’s past helps us understand the dynamics of segregation in the rural communities that … continue to confront complex issues related to race, trust, political participation, and economic performance to this day” (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Logan and Parman2018: 668).

Finally, rules meant to overcome the disadvantages of segregation often get bypassed in favor of those responding to the disparate impacts wrought by segregation. Using a quasiexperimental design, Sanaz Mobasseri (Reference Mobasseri2019) has found that while employers are generally less likely to call back black than white job applicants, when a violent crime occurs in the vicinity of the establishment in question, callback rates for blacks dip an additional 10 percentage points though the same does not hold true for white or Hispanic applicants. Ironically, the rules that protect against employment discrimination do not necessarily apply to the day-to-day decision making of employers aiming at the best “fit” for the job, regardless of race. When Devah Pager (Reference Pager2003) examined how employers used rules of thumb such as criminal records to disadvantage blacks in relation to whites, she discovered that though a criminal record made it more difficult for anyone to obtain employment, the chances that whites with a criminal record would receive a callback were roughly similar to those of blacks without one. In a later study, Pager, Western, and Bonikowski (Reference Pager, Western and Bonikowski2009) discovered that the job applicants may not perceive that they have been treated unfairly, even in cases in which researchers found that they had been categorically denied an opening despite their qualifications, or had been channeled downward into a lower paying or less prestigious position while their similarly qualified white counterparts had obtained a position better than the one advertised. It is my interpretation that ritualized rules of engagement have effectively “cooled the mark out,” with the target of bias, “the mark,” “expected to go on his way, a little wiser and a lot poorer” (Goffman Reference Goffman1952: 451).

Isomorphic Disadvantage

Rules emanate from organizational design, and these designs make some disadvantaging policies more likely than others. Here I draw on Walter Powell and Paul DiMaggio (Reference Powell and DiMaggio1991), who elaborated the concept of isomorphism to explain why organizations tend to develop similar forms and practices when operating in the same field. I do so to explain why similar policies of disadvantage do not need a puppet master with disadvantaging intentions to spread. In Social Science History, Rick Rodems and Luke Shaefer (Reference Rodems and Shaefer2016) use the case of the 1935 Social Security Act to demonstrate the workings of isomorphic disadvantage. In that era, the majority of the African American workforce were agricultural laborers or domestic servants. Their occupations were therefore categorically excluded from “social security” (also known as old age insurance) and unemployment insurance. According to the policy makers involved, the decision to exclude was based on occupation rather than race. Although the policy had the effect of creating a “racially bifurcated welfare state” (ibid.: 387), it may have been implemented because this was what other policy commissions were doing on an international scale. Rather than focusing on whether these policies would lead to greater disadvantages for some groups within their own country, the policy makers sitting on the policy commission in any one country focused on whether their policies were consistent with those undertaken in the population of policy commissions across the globe.

While policy makers seem to orient their attention to the best available blueprints in their field, they do not have a static and entirely stable population of blueprints from which to draw. Indeed, some policy commissions may decide to update their inclusion criteria as technological advances and political pressures make those updates salient. While isomorphism may explain the initial conditions of disadvantage, it does not explain why some policy commissions resist updating their policy decisions and why they are not subject to political and normative pressures to coerce new accommodations.

Rather than argue that certain exclusionary policies resulted either from racial struggles or isomorphism, let us consider how difference in race or other relevant status may affect isomorphism. When nation-states begin to talk similarly to and resemble their “neighbors,” some things are lost and others amplified in the transition. What types of considerations can then “go without saying because they came without saying” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1977: 167)?

Rodem and Shaefer (Reference Rodems and Shaefer2016: 389) write that if racism were the only reason for the exclusion, we would expect there to be “something in the historical record suggesting explicit Southern support for the exclusion of agricultural and domestic workers from [unemployment insurance].” However, did senators and congressmen in the mid-1930s explicitly discuss race when engaging in racial strategies of exclusion? Should we assume that racial exclusion was “entirely the result of the machinations of Southern congressmen”? And are there investigative strategies to help us capture implicit bias in the historical records? Or, as Tilly asked, why are errors corrected in some cases but not others? When it comes to antilynching and other legislation with clear racial intent, could we rank politicians more generally based on their voting records? And might those rankings be instructive for what can later go without saying? In other words, if an excluded group is regarded as both an out-group and administratively difficult, are future fixes less likely?

We must bear in mind that in their 1992 article in Social Science History, Andrew Abbott and Stanley DeViney argued that welfare policies could be examined as transnational phenomena, with the policy decisions made in one state affecting those in others. The sequence of social protection programs in highly industrialized countries have followed identifiable stages, with some late adopters moving through them faster than earlier ones. The more countries have been connected through trade flows, religious institutions, and similar labor policies, the more they have resembled each other in the sequence of their key welfare programs.

Isomorphic disadvantage can change course, however, as some countries are unwilling to instantly mimic what other countries do; such countries, which have a higher threshold, can take a wait-and-see approach and break ranks. As Abbot and DeViney (Reference Abbott and DeViney1992: 269) write:

Assume that countries are watching others as a wave of contagious adoption takes place. At a certain point, some likely country conspicuously fails to adopt. (The “conspicuous” character arises in local political processes; welfare policies are actively debated, and decisions about them are generally quite public.) Such a conspicuous non-adoption could generate its own wave of non-adoptions; non-adoption, that is, might be contagious as well. As a wave of non-adoption brings adoption to a halt, the situation is defined as one of “wait and see.” Then eventually a country breaks rank and starts the next wave of (contagious) adoption.

One may imagine a higher threshold for exclusion when the disadvantaged parties seem to be people who matter. Technical or administrative difficulties may evoke effusive apologies and a range of fixes to lessen the disadvantages brought about by exclusion. By virtue of who loses, new questions about the loss may be asked.

The Unlucky Turn of Events

Sometimes disadvantages are amplified in the long term thanks to unfortunate, external events. Consider the missed communications that escalate tensions during legislative reconciliations, the ill-timed distraction of sorrow that paralyzes leadership and provides a chance for the opposition to make a fresh move, or the unexpected exodus of a truly disadvantaged group after the levies fail during a natural disaster. These are accidents of history, of course, but the willingness and the capacity to respond are patterned. Briefly, I turn to two such unlucky turns: one, an assassination with long-term political and economic consequences; the other, a weather-related disaster.

As Abraham Lincoln settled into his seat at the Booth Theater, it seemed that disadvantages were being wiped away, though not without complaint. Union General William T. Sherman had distributed 400,000 acres of coastal land among former slaves, land grants providing them with seed capital were in the works (“40 acres and a mule”), and pensions for them (similar to those offered Union soldiers) were under consideration. The provision of 40 acres came with the following stipulations: “‘not more than 40 acres’ of land was to be provided to refugee or freedman male citizens at three years’ annual rent not exceeding 6 percent of the value of the land based on appraisal of the state tax authorities in 1860” (Darity Reference Darity2008: 660). In addition, the Southern Homestead Act of 1866 provided for the purchase of 80 acres in the Southern states at a price of $5 for freedmen (ibid.). With the untimely death of Lincoln and rising opposition to Black Reconstruction (DuBois Reference DuBois1995; Foner Reference Foner1982), these policies, which were meant to reverse the course of disadvantage, withered away. The newly affirmed President Andrew Johnson rescinded General Sherman’s Special Field Order no. 15, thereby securing those coastal lands for their incumbents. The pension plan, too, was never enacted, in part because Pension Bureau officials feared that it would “set the negroes wild” (Logue and Blanck Reference Logue and Blanck2008: 388). Deemed discredited by nature, blacks could be depicted as contaminated and contaminating. Their disadvantage would allow the national body politic to remain healthy; the leadership arguing otherwise lacked luck.

Because of this unlucky turn of events, former Confederate General Robert V. Richardson noted, “The emancipated slaves own nothing, because nothing but freedom has been given to them” (quoted in Foner Reference Foner1983: 55). The stratification economist William Darity uses this history of dispossession to make an economic and moral argument for reparations, which he articulates as acknowledgement, redress, and closure:

Acknowledgment refers to the public recognition of a grievous injustice committed by the institution or group that bears responsibility for it. This includes a formal apology. … Redress refers to compensatory actions taken to mitigate, to the extent possible, the long-term consequences of the grievous injustice. With respect to reparations due African Americans, this would involve the design and implementation of a program that would eliminate historically generated racial disparities in the United States caused by slavery, legal segregation, and ongoing discrimination. Closure refers to a settling of accounts, a healing process brought to fruition. (Darity Reference Darity2008: 656–57)

Darity’s means-end argument recognizes that increasing wealth (X) provides a pathway to decreasing disadvantage (Y), and that wealth immorally extracted or stolen from an entire group of people needs to be returned for the chasms to close and the emotional rifts to heal. Nonetheless, a number of factors might get in the way of X leading to Y, and it is the penchant of historians and interpretive social scientists to explain why things may not go according to plan. In principal, over a long period, even well-laid tracks become stressed, their switchmen, unruly. How does this happen?

Those who avow reparations may conceal their unwillingness to support it in the way they vote or manage the policies and procedures necessary for implementation.

The cost-benefit calculus relies on the unacknowledged role that social identity plays in giving weight to the costs vis-à-vis the benefits tied to socially discreditable beneficiaries.

The existing financial ecosystem and the regulatory environment may allow those with capital to devise schemes to recoup their resources at the expense of the intended beneficiaries (Baradaran Reference Baradaran2015).

Historical conditions may lead to reactions against reparations that their promoters did not anticipate and that either amplify or derail the planned benefits of the program. (Unintended consequences, by definition, may be positive or negative.)

These scenarios do not justify any lack in effort to rectify past wrongs. Instead, they place promoters and opponents on alert to the factors that might alter the predictions from either side—good and bad luck being what they are.

While presidents and their policies become unlucky when wiped out by an assassin’s bullet, entire communities can be shriveled by heat waves, deluged by the effects of breached levies, downed by tornadoes and hurricanes, or wiped out by the migration of hungry beetles. Although such disasters are random acts of nature (“acts of God”) and thus beyond human control, their effects are not. In Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, Eric Klinenberg advocates for social analyses of disasters to illuminate why some populations or geographic clusters experience more ill effects than do others during the same disaster. In 1995, Chicago saw 465 heat-related deaths in one week and an “excess death” rate of 739 above the norm. These casualties exceeded the 300 deaths of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and other disasters of more recent memory. Klinenberg points to family ties, the structure of the buildings in which people lived, and the social cleavages across the city as the unnamed culprits that directed the course of disadvantage. These disregarded conditions and processes had implications for the disadvantages forged in both the moment and the future:

First, the social morphology and political economy of vulnerability that determines disaster damage; second, the role of the state in determining this vulnerability at both structural and conjunctural levels; and third, the tendencies of journalists and political officials to render invisible both the political economy of vulnerability and the role of the state in the reconstructions of the disasters they produce. (Klinenberg Reference Klinenberg1999: 242)

The very representations of disasters have helped guide the scientists and planners studying not only them but also the ways in which the municipality can prepare itself to deal with future calamities. How sources of disadvantage are rendered helps strengthen the disadvantaging responses (or nonresponses) in future rounds of action.

Remembrance, Reparations, and Repair

What are policy makers and their publics willing to repair? That depends, in part, on what they recollect in ritual. As Lyn Spillman (Reference Spillman1998: 468) explains: “The intrinsic meaning of past events imposes a pattern on later collective memories and constrains memory entrepreneurs: persistent collective memories are robust because they are charismatically meaningful.” I use the term “repair” rather than “reparations” because the latter implies that we are trying to “put things back where they were,” while the former focuses on solidarity. Repair implies that there may exist what Gregoire Mallard calls “a social debt that needs to be paid back in order to maintain the existence of social bonds (or solidarity)” (Mallard Reference Mallard2011: 228). Mallard’s treatment of reparations and social debts allows us to reimagine reparations as a ritual that, instead of paying for past wrongs or sanctioning wrongdoers, opens up an opportunity for communication. The economic transactions involved in repair represent relational work (Zelizer Reference Zelizer2005) accomplished with the state and the market as mediating parties and with the shared goal of “restoring a sense of larger community … mak[ing] visible a new political alliance between and across formerly warring parties and neutral bystanders” (Mallard Reference Mallard2011: 239–40).

Rituals and monies indicate who belongs. If we engage in deceptive activities, we may tell at least ourselves that we did so to protect something valuable, something beyond money. We may be protecting the rule of law, a sense of fairness, a thing tied to the universal. The fact that the rules are disadvantaging may be difficult for us to process cognitively, even where overwhelming evidence proves the case. When we follow the same types of policies as does everyone else, the replication of “best practices” may mask the dynamics of who wins and who loses, the places beyond the decision maker’s control or her responsibility in maintaining disadvantage. These decisions often emerge from a ritual of fact finding, public hearings, and harmonization with existing policies and procedures. Consequently, anything that seems to break these rituals becomes more difficult to legitimize.

Finally, money cannot bring about closure, at least not on its own. (And some hurts are so traumatizing that closure cannot be hoped for, only a meaningful working through.) It is possible to compensate for a loss with the right amount of money but nonetheless distribute it in a way that rends the social fabric further (Bandelj, Wherry, and Zelizer Reference Bandelj, Wherry, Zelizer, Bandelj, Wherry and Zelizer2017; Wherry Reference Wherry, Bandelj, Wherry and Zelizer2017; Zelizer Reference Zelizer2010). Are recipients of reparations treated as if they could be a danger to themselves (discreditable or discredited), or are they treated like autonomous adults whose financial choices are likely to be legitimate (creditable)? Does the distribution process for the money honor its recipients, or does it degrade them (Sykes et al. Reference Sykes, Križ, Edin and Halpern-Meekin2015; Wherry et al. Reference Wherry, Seefeldt and Alvarez2019)? What are the various meanings attached to the money and the manner of its transfer? And how might the distribution of monies be attached to existing rituals about social identity that affirm these rituals along with the monies now associated with them (Wherry Reference Wherry, Bandelj, Wherry and Zelizer2017)? And finally, what are the other objects (media of exchange) that should be bundled with cash payments to make these monies meaningful (Bandelj et al. Reference Bandelj, Wherry, Zelizer, Bandelj, Wherry and Zelizer2017; Zelizer Reference Zelizer1994)? In short, using financial compensation to effect social repair requires that we attend to the dynamics of relational work and symbolic matching, and that these dynamics serve as ends as well as means.

Conclusion

To conclude, to disadvantage is to place one group in an unfavorable position in relation to another. Disadvantaging is a collective act, even when its culprits do not recognize their actions as tied to institutional rules or to social networks that recreate and enforce disadvantaging conditions. There is more than one way either to arrive at an unfavorable position or to have the deficits of a position amplified. It is the job of the social analyst to identify those pathways and to interpret the role of motives, social identities, meaningful relations, and resources. Once these factors set disadvantage on its rails, the Matthew Effect manifests itself: those who already have are given more, and from those who do not have, more is taken away.

There are at least two ways to misinterpret what can be done about disadvantage on the policy side and how this can be studied by academics. The first is to identify the pathways to disadvantage across history in the hope that these will provide a blueprint for its reversal; the second, is to abandon all hopes for precision in the study of disadvantage because so much could have emerged midcourse or simply been concealed. Instead, the message is this: history draws us to the precise details of social interactions and debate, illuminating what makes a disadvantage durable and why rational attempts to reverse it have failed. The dynamics are complex, not because we theorize them to be so, but because our empirical tradition reveals what lies beneath the surface. History makes us mindful of the paths not taken and of alternatives that were available but not perceived by those who needed them most. Being skeptical of common sense and remaining somewhat humble in our theoretical ambitions, we are able to establish the conditions under which the well laid blueprints that seemed solid at first, were more likely to melt into thin air. As the mists begin to clear, we may discern the silhouette of the newly possible.