Introduction

The area of perinatal mental health is a major public health concern. Mental health difficulties experienced during the perinatal period make a significant contribution to maternal and infant morbidity and mortality, as well as having potentially long-term adverse impact on children’s development (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum and Pariante2014; Howard & Khalifeh, Reference Howard and Khalifeh2020). Perinatal mental health services that address parental mental health problems and optimise the parent-infant relationship are expected to be highly cost effective because of the benefits for parent’s physical and mental health, and for the long-term developmental outcomes for children (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Parsonage, Knapp, Iemmi and Adelaja2014).

The estimated rates of perinatal mental health disorder in Ireland are based on data from the UK population and are thought to range between 22.4–24.4% of maternities (postpartum psychosis 0.2%; chronic serious mental illness 0.2%; severe depressive illness 3%; mild-moderate depressive illness and anxiety states 10–15%; Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) 3%; 15–30% adjustment disorders and distress) (HSE, 2017). A recent review of studies looking at prevalence rates of perinatal mental health problems in the Irish context reported that a significant number of women in Ireland are affected by perinatal mental health problems, but the prevalence rates differ significantly between studies (Huschke et al. Reference Huschke, Murphy-Tighe and Barry2020) indicating a need for more robust epidemiological research in this area.

In Ireland, perinatal mental health services have recently begun development. In 2016, following on from the publication of the first National Maternity Strategy (Department of Health, 2016), the Health Service Executive (HSE) developed a model of care for specialist perinatal mental health services (SPMHSs) (HSE, 2017) and its implementation is ongoing. Within this model, a national clinical pathway for the provision of perinatal mental health services is proposed, of which the SPMHS is a component. The SPMHS is focused primarily on the needs of women with moderate to severe mental health problems which is estimated to occur in approximately 3.5% of maternities in Ireland. Of note, a recent report from the Royal College of Psychiatrists has recommended expansion of the service in the UK for 10% of mothers who have recently delivered (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2021). Other components of the PMH clinical pathway include general practitioners, primary care teams, maternity hospitals, generic and specialist adult mental health (AMH) services, specialist parent-infant mental health (IMH) services, disability services and other agencies. It is recommended that there is an integrated PMH care pathway across all health and social care services providing care to people and their families using these services, so that there is a consistent, co-ordinated, timely and evidence-based care response.

One of the principles of good quality PMH service provision is the dual function of assessing and treating maternal mental health difficulties and actively supporting the parent-infant relationship (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2021). Currently, service development is orientated towards addressing maternal mental health care needs and less attention has been given to the parent-infant relationship and the infant’s mental health. Perinatal-IMH services provide specialist support and therapeutic interventions for parent-infant relationships in pregnancy and the early years and are a component of the PMH clinical pathway as described in the model of care (HSE, 2017). However, they are not widely available in Ireland, and this is acknowledged as a significant and important gap to address (HSE, 2017). Given the potential impact of parental mental health difficulties on the attachment relationship and developing infant, it is critical for an effective and quality PMH care pathway that consideration is given to both maternal and IMH needs. It is vital that these needs are screened for, assessed and appropriately responded to by all components, including AMH services, involved in the perinatal care pathway. The provision of high quality perinatal mental health services requires education and skills training programmes on perinatal and IMH for members of the workforce in each of the components of the care pathway, including AMH services.

Rationale for implementing an IMH model to AMH services

At the time of this study, SPMHS teams were in the early stages of development and were not operational in some of the hospital groups. The responsibility of care for women with moderate to severe mental health difficulties lay primarily within community AMH teams. However, a recent audit carried out in Ireland indicated that women with perinatal mental health difficulties referred to psychology within AMH services in Ireland waited an average of 35 weeks for their initial appointment (Doyle & Tierney, Reference Doyle and Tierney2018). This is significantly longer than the timeframe of 1 month recommended by NICE guidelines (NICE, 2014). Due to these extensive waiting times and considering the importance of early intervention in perinatal and IMH care, it is necessary that all AMH team members have the knowledge and skills to identify these difficulties and provide evidence-based preventative care and interventions for these women and infants. As a result, the interdisciplinary IMH approach is both appropriate and necessary within AMH teams in secondary care.

The IMH model

The IMH approach, based on the pioneering work of Selma Fraiberg in the early 1980s, has become an increasingly prominent field of both research and clinical practice worldwide (Fraiberg et al. Reference Fraiberg, Adelson and Shapiro1975, Fraiberg, Reference Fraiberg1980). The IMH model is a multidisciplinary approach to supporting the social and emotional development of infants aged 0–3 years. IMH focuses on infant development within the context of early caregiving relationships and places an emphasis on encouraging and strengthening parental caregiving capacity and early relationship development (Weatherston & Browne, Reference Weatherston and Browne2016). The Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health (MI-AIMH) has led the way in developing a model of training and service development for IMH practitioners which embodies these foci. The resultant MI-AIMH model supports the training of staff from across multiple disciplines, such as psychology, nursing, social work or psychiatry, to become IMH practitioners, develop their reflective practice and to learn specific skills and competencies which are essential within IMH service provision (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Maguire, Carolan, Dorney, Fitzgerald, Scahill and Kelly2015). The IMH framework outlines different levels in which IMH practitioners can intervene in order to support families and their children. These include: concrete assistance; emotional support; developmental guidance; early relationship assessment and support; advocacy and infant-parent psychotherapy (Weatherson, Reference Weatherson, Shirilla and Weatherson2002). Each of these aspects are briefly summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Dimensions of IMH service provision

Development of the North Cork IMH model

In 2003, clinical psychologists working as part of the North Cork Child, Adolescent and Family Service had identified a significant gap in service delivery and the absence of a framework for service provision for infants and toddlers and their caregivers in the 0–3 age group. To address this gap, two clinical psychologists from the service pursued MI-AIMH Endorsement® and were awarded the qualification of ‘Level 3 IMH specialist’ in 2006 (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Maguire, Carolan, Dorney, Fitzgerald, Scahill and Kelly2015). To be awarded this endorsement, candidates must develop and demonstrate substantial competency across several areas identified by the MI-AIMH such as theoretical knowledge; law, regulation and agency policy; working with others; communication and reflective practice (MI-AIMH, 2011).

To address the gap within the wider service delivery for the 0–3 year age group within Ireland, a national framework for the delivery of IMH training was developed and piloted within this North Cork service. A 3-day IMH masterclass was facilitated by Dr Deborah Weatherston, an international IMH supervisor and mentor along with two local IMH specialists in 2006. This masterclass was guided by the MI-AIMH Competency Guidelines® and aimed to disseminate awareness of the IMH model to interdisciplinary staff working in child and family services within the region. The topics covered within this masterclass included: the theoretical underpinnings of IMH, understanding the parent-infant relationship, assessment and intervention strategies, the development of therapeutic relationships and reflective practice. In order to facilitate sustainability of the IMH approach and provide staff with the opportunity to consolidate and develop their skills in this area, an IMH network group (IMH-NG), comprised of the ten professionals who had attended the masterclass was established in November 2006.

Following the success of the initial IMH-NG, in 2009 two further IMH-NGs were established in North Cork through replication of the IMH training model. These newly established IMH-NGs were expanded to include wider members of the North Cork community working with young infants and their families which included staff working in childcare, community-based family resource centres and domestic violence services. An evaluation of NG members’ experiences of participating within these groups revealed significant improvements in IMH knowledge, clinical skill, service policy and delivery and an increased understanding of the importance of caregiver relationships in promoting the social and emotional health of young children (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Maguire, Carolan, Dorney, Fitzgerald, Scahill and Kelly2015).

Development of a perinatal and IMH network group

In 2016, some of the clinicians participating in this study who had previously worked in an IMH service, recognised a need for promotion and education of perinatal and IMH principles and practices within AMH teams within the region. A 2-day masterclass was organised and delivered to a number of AMH service staff in June 2017. In August 2017 the perinatal and IMH (PIMH) network group was established. In line with the North Cork model, the focus of this PIMH-NG was to provide staff with the opportunity for continuous development of IMH knowledge and to provide a space for discussion around the application of this knowledge to clinical practice. The PIMH-NG structure consists of a 1.5 hour meeting on the first Thursday of every month. To date, as the group is being established, it is co-ordinated and facilitated by three psychologists who have previously worked in an IMH service. The group received guidance and resources from a local IMH specialist during its formation. The aim of the PIMH-NG is to provide a reflective space in which staff can consolidate their learning and develop a wider knowledge base around IMH through group discussion using evidence-based literature. The PIMH-NG also aims to enhance staff clinical practice and professional skill in the IMH model and provide of a shared language and understanding in which young children and their relationship with their caregivers can be conceptualised (Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Maguire, Carolan, Dorney, Fitzgerald, Scahill and Kelly2015). This PIMH-NG had been in operation for 1.5 years when the facilitators of the group made the decision to evaluate members’ experiences of participating within the group in order to consolidate future goals and inform future group content and structure.

The present study

The present study explored the experiences of the members of the PIMH-NG and what they felt were the benefits and challenges of participating within this group. Data was collected from a 1-hour focus group in which seven members of the PIMH-NG responded to open-ended questions about their experiences of participating in the group. All participants also completed a 12-item questionnaire incorporating demographic and descriptive information regarding their attendance of the group as well as their employment experience.

Method

Participants

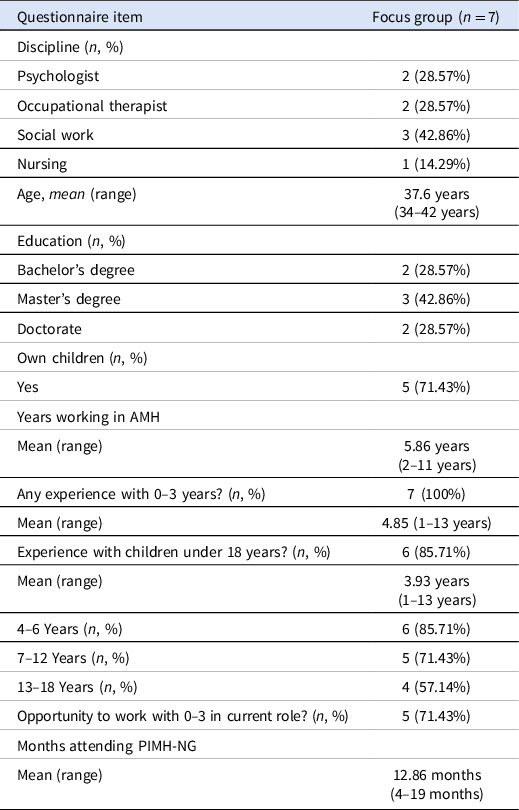

Seven of the nine active members of the PIMH-NG took part in the focus group for this study. At least one member of each discipline was represented in the group. All participants were working in community-based AMH services within the same region in Ireland. Demographic data from the sample is presented in Table 2. Although specific information was not gathered as part of the questionnaire, the opportunities that staff had to work with the 0–3 age group in their current roles included parent and infant groups, direct therapeutic work with parents and their children as well as individual therapeutic work with parents in which the parent-infant relationship was integrated throughout.

Table 2. Demographic data of the focus group participants

Data collection

Focus group

The researcher completed a 1-hour focus group with seven out of the nine active members of the PIMH-NG, two of whom were facilitators of the group. To explore the experiences of participating in a PIMH-NG within an AMH service, the researcher asked a series of open-ended questions. These questions asked participants to discuss what they felt were the benefits and challenges of participating in the group, what the barriers or facilitators to the work within the group were, what improvements could be made, and what their vision was for the future of the group. The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed. Data analysis was performed on the transcript.

Demographic Questionnaire

A 12-item questionnaire was administered to gather descriptive information about the seven participants. The items included age, gender, discipline, level of qualification, work experience with the 0–3 age group and other age groups, number of own children and duration of group membership.

Data analysis

The focus group was transcribed and analysed using Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun, Clarke, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012). Analysis was comprised of six stages:

-

i. Familiarisation with the data following multiple readings of the transcript

-

ii. Generating initial codes via open coding

-

iii. Searching for themes

-

iv. Reviewing potential themes

-

v. Defining and naming themes

-

vi. Consolidation of themes

In addition to the above six steps, the themes and supporting quotes were reviewed by the second author in order to ensure rigour and trustworthiness of the data.

Reflexive positioning

The first author has previously been employed as researcher within the field of perinatal mental health and, as such, places great value on raising awareness of the IMH model as well as increasing service user access to interventions based on this model. The author’s reflexive positioning was considered throughout all stages of the data collection and analysis.

Results

The analysis of the transcript of the focus group identified four major themes: (i) Bringing the knowledge out: Influences on clinical practice and service delivery, (ii) The benefits of group-based learning for developing IMH knowledge, (iii) External factors that facilitate the PIMH-NG and (iv) Evaluating and re-defining the focus of the network group. These could be further elaborated into sub-themes as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes emerging from the PIMH-NG focus group

Theme 1: Bringing the knowledge out: Influence on clinical practice and service delivery

Enhanced clinical practice

Participants reported that they utilised the knowledge they had developed around IMH and attachment within their everyday clinical practice. It was noted that participation in the NG had helped participants to see their clients, or the behaviour of their clients, from a developmental perspective. Being familiar with the models of attachment and IMH due to their discussion within the NG also aided with case conceptualisation and in developing an understanding of client behaviour. This knowledge allowed participants to view their clients’ difficulties from a different perspective. PX2:‘…you’re asking more, what happened to them, what went on in their life rather than what’s wrong with them’. Participants also described that it was beneficial to discuss attachment concepts with clients as it helped clients to understand their own difficulties and thus served as a motivating factor for change. This was affirmed by PX6 who noted that ‘sometimes people need to develop a little bit of awareness as to the reason why they do the things they do and then that can evoke change’. PX2 also described that some of the models of attachment that were learned about within the group provided them with a language with which they could talk to clients about attachment. PX2: ‘it’s given me a kind of an easy way to talk to clients and I suppose other clients as well about attachment concepts’.

Dissemination of IMH knowledge

It was identified by participants that they were helping to raise wider awareness of IMH and attachment by discussing these concepts amongst their colleagues and at team meetings. Participants illustrated that this knowledge was shared by discussing their own individual cases amongst the team and also by contributing and framing wider case discussions within the team from an attachment perspective. PX2 outlined that: ‘there is a value in just being able to talk about this stuff at team meetings even if we aren’t working directly with any of the cases, that we bring that way of talking about what’s going on, that, you know, even in adult mental health how people are behaving, to bring that perspective’. Several participants agreed that disseminating IMH knowledge in this manner could shape how other team members interacted and thought about their own clients. PX6 described that ‘if we’re bringing that message to our teams from being in this reflective space, that in essence is shaping how interventions and how people are dealing with people who come to the service’.

Increased reflective practice

It was agreed by all participants that the PIMH-NG group provided an opportunity for them to develop their reflective practice. Participants discussed how this was beneficial in their clinical work as it allowed them to not get caught up in the presenting behaviour of clients. PX7 described that ‘It’s very easy to get caught up in that whereas if you can take the step back and realise as PX6’s saying, you know, if they’re doing it for a reason, it’s their answer, it’s their way to cope’.

Theme 2: The benefits of group-based learning for developing IMH knowledge

Continuous learning

Focus group participants identified that regular PIMH-NG attendance provided them with the ongoing opportunity to develop and build knowledge around IMH and attachment. Monthly attendance allowed participants the opportunity to continuously learn and develop competencies in these areas and reflect on how to apply it to their clinical practice. PX1: ‘…you have the model of attachment and you have here constantly reminding you and helping you to learn about it’.

Reflective group discussion

All participants identified that they particularly valued the reflective space that the group provided. The process of reflective discussion within the group allowed for sharing different or alternative perspectives on the articles and materials provided. PX7 described: ‘So I know I leave feeling re-energised. I feel, yes, I’ve reflected on something, I could see a different perspective. I think we get so caught in our own viewpoint’. Participants reported that the fact that the group was comprised of multidisciplinary colleagues was beneficial for the learning as each member brought something different to the table. A number of participants agreed that having different perspectives facilitated the reflective aspect of the group, the further development of IMH skills and helped inform participants of how to implement IMH practice within the wider AMH service. PX1 stated: ‘you really need, you know, a group of colleagues, multidisciplinary colleagues around you, thinking about it, reflecting in order to, em, in order to develop your own skills…’.

The network group as a ‘secure base’

It was highlighted that being involved in the network group provided participants with ongoing peer support in developing IMH knowledge and applying it to practice. PX3: ‘…it’s when you’re in a team and some people don’t have an interest in perinatal they don’t really want to hear about the attachment or the bond or anything like that, do you know whereas here I suppose the interest is here. You can discuss it here’. It was identified by several participants that the work would be difficult to do alone and it was noted that meeting regularly as part of the PIMH-NG was beneficial within the work. PX1 reported: ‘I think having a group of like-minded interested people who are, who want to do it too, em, I think those bits are really important like they were saying earlier, you can’t kind of do it alone’. Participants reported that attending the group and having the support from other members whilst also being reminded of the evidence base of attachment and IMH research helped them to keep IMH at the forefront of their clinical practice and in the agenda of discussions with other members of the teams. This was highlighted by PX1: ‘at least you have the model of attachment to look and you have here constantly reminding you and helping you to learn about it and it helps you to formulate my clients’.

Organisational structure of the group

Focus group participants identified that they found the organisation and structure of the monthly meetings facilitated their ability to attend regularly and to continue to build on their IMH knowledge within each session. Participants outlined that they appreciated the work that the facilitators put into booking the meeting room and sending out the reading material in advance. PX4 noted: ‘it’s brilliant like having articles kind of provided for you. You know that you don’t have to kind of go looking for them’ It was identified that these elements, as well as the 80% attendance rule, facilitated their regular attendance.

Theme 3: External factors that facilitate the PIMH-NG

IMH masterclass

Participants agreed that the IMH masterclass, facilitated by a local IMH specialist, was the precipitating factor for the establishment of the PIMH-NG. PX5: ‘I suppose if you’re looking back to what facilitated the group I suppose it’s the masterclass really like, we wouldn’t be here only for the masterclass’. Additionally, having an IMH specialist in the area who provided the reading materials, which were mapped on to specific IMH competencies, guided the structure and content of the initial PIMH-NG meetings. This was highlighted by PX2: ‘having an infant mental health specialist in our general area who has provided the masterclass and that and has, it’s really important then providing the reading materials’.

Management support

All participants had been supported at a managerial level to allocate 1.5 hours of their monthly schedule to attend the PIMH-NG. There was acknowledgement among participants that in order for the work of the group to continue, that ongoing support at a managerial level would be required. PX2: ‘going forward that’ll be really important that they, that there’s continual support of it’.

Links with other NGs in the area

Focus group participants discussed that when the PIMH-NG had been established for 1 year, they had linked in with another network group in the area which had been running for a number of years. It was described that linking in with another network group had supported them to evaluate their objectives and described that this had energised the group again. PX1: ‘we’d kind of been set up a year and we were like where are we, what are we doing and we brought in one of the other teams network groups whose been running for years and even I think that energised us all again’.

Theme 4: Barriers to carrying out the work of the PIMH-NG

Staff movement

It was acknowledged by the participants of the group that staff movement could be both a positive and a negative aspect. During the focus group it was described that a number of members had moved or had experienced changes to their roles of employment within the AMH service. As a result of this, some of the members had left the PIMH-NG and it was noted that this was something that impacted on the group and on service development. Other participants who had changed role but were still attending the group reported that they had sometimes questioned whether it was still appropriate to attend the NG due to this. PX1: ‘I’ve moved roles once or twice, it’s kind of like, oh god, should I be attending…can I justify it, is it helpful’. On the other side of that it was also discussed that staff movement could be seen as a positive aspect, particularly for the indirect aspect of the work, where NG members were able to further share IMH knowledge within different teams. Moving roles also gave some participants the opportunity to reflect on how successful their work around raising awareness of IMH had been when they found that the new team weren’t as familiar or up to date with IMH research or attachment concepts. PX1: ‘I think I took for granted that all teams were shaped like that’. It was identified by participants that, moving forward, it would be important to invite new members to join the NG to maintain the structure of the group and replace those members who had left.

Supervision

It was suggested by a number of participants that, moving forward, PIMH-NG facilitators would need ongoing supervision from an IMH specialist. The function of this supervision would be to guide the structural aspects of the group such as sourcing materials and readings for developing IMH competencies as well as providing clinical supervision so that the PIMH-NG facilitators could create and provide the reflective space for other NG members. PX2 affirmed that: ‘whoever is kind of facilitating the group will need supervision or some support in directing that piece as well so that we have that parallel process of whoever is facilitating the group has supervision and so help create that reflective space…’.

Development of IMH initiatives

It was identified within the group discussion that as part of the work was raising awareness and understanding about IMH and attachment, the next step was further service development in the form of therapeutic groups that ran adjunct to the AMH service. With the increase in knowledge and awareness of IMH it was also discussed that new groups or IMH initiatives would be needed to meet the forecasted growth of demand of referrals or requests for PIMH support within the AMH service. PX2 outlined that: ‘sometimes I think it was helpful that we were able to set up some of the…initiatives so that we can bring it up in the team and that then we can say, ‘yeah actually you can go maybe to this group’ and I think it just, em, it’s important that there’s also that bit happening’.

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of the members of a PIMH network group and what they felt were the benefits and challenges of participating in a continuous learning and reflective practice group. The data gathered from the focus group indicated that participant involvement in the PIMH-NG enhanced their clinical skill, reflective practice and supported the dissemination of IMH knowledge throughout their respective teams. The PIMH-NG facilitated this work by providing the opportunity for continuous learning, reflective group discussion and ongoing peer support. Lastly, the group identified a number of barriers that had arisen since the group’s inception. These barriers included: staff movement, the need for supervision from an IMH specialist moving forward as well as the need for training and the further development of IMH initiatives.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Maguire, Carolan, Dorney, Fitzgerald, Scahill and Kelly2015) who reported that staff who participated in IMH-NGs demonstrated increased clinical knowledge and skill in the area of IMH as well as increased capacity for reflective practice. This study also highlighted that multidisciplinary input and support from higher management were facilitating factors for this work. However, Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Maguire, Carolan, Dorney, Fitzgerald, Scahill and Kelly2015) reported that disseminating information to other colleagues who were not informed by IMH was a significant challenge for the participants in their study whereas the participants in the current study reported no difficulties in this regard. In fact, the dissemination of IMH knowledge was a significant benefit of their participation within the group. In line with the findings of the current study, an evaluation of Cork City Parent-Infant NG (Reaney Reference Reaney2017) also reported that both the multidisciplinary and peer support aspects of the group facilitated NG members’ promotion of the IMH model. This discrepancy may have been due to the inclusion of a broader range of disciplines based across a wider range of community-based programmes and services in the North Cork IMH-NG study rather than solely the inclusion of mental health services as per the current study. Furthermore, both peer support and regular attendance have previously been highlighted as facilitating factors for those participating in collaborative peer supervision groups for staff working within the IMH field (Thomasgard et al. Reference Thomasgard, Warfield and Williams2004). This study contributes to the developing evidence base surrounding the benefits of bring IMH knowledge into AMH practice. A further study of the impact of IMH specific training for staff working in an AMH context also reported that the development of expertise in IMH allowed them to foster a greater understanding of their adult clients as well as an insight into the intergenerational pathways of mental health difficulties (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, McGlade and Killick2019).

Staff working within generic and specialist AMH services are well placed to prevent, identify and intervene in cases where either IMH or the parent child relationship are at risk. Psychiatrists, as clinical leads and drivers of service development within mental health services, have a key clinical and leadership role to play in the promotion, prevention and early intervention of PIMH difficulties. It is crucial that all staff are provided with opportunities to develop PIMH knowledge and skills that are evidence based and within this, it is important that reflective practice is included as an essential component of professional development. As such the IMH-NG model of training and education is a useful approach to developing workforce knowledge and skills.

Strengths and Limitations

A notable strength of this study was the exploration of the experiences of staff who participated in a PIMH-NG but who were employed in an AMH setting. Previous studies within this area have primarily reported on the experiences of staff participating in NGs while working within child and family settings whereas this study focused on the experiences of staff applying the IMH model within an adult context. This study therefore provides a unique and novel perspective within this area of research. Although the sample size was small, it was appropriate for the exploratory nature of this study. Some limitations of this research include the use of focus group methodology, which is sensitive to the biases of a group setting, the wide range in the duration of which members were attending the group (4–19 months) and the unequal representation of staff members from a nursing background. These factors may have had an impact on the nature of the themes which emerged during the focus group discussion.

Future Directions

A number of future directions have been identified by the network group. Firstly, the group aims to diversify the current membership. The inclusion of diverse perspectives from different disciplines as well as other services and agencies working within the PMH care pathway would enrich the learning environment within the network group. To this end, members of the network groups are providing IMH workshop trainings to diverse cohorts of professionals which will generate interest in IMH-NG membership. According to the Irish Association for Infant Mental Health, there are currently up to 15 similar network groups meeting across the country. A further aim of the PIMH-NG is to create links with a ‘network of network groups’ which will support all network groups within Ireland to ensure that they are aligned to their role, function and practice to support IMH knowledge and skills acquisition among members in alignment with international best practice and fidelity.

Conclusion

To date, the North Cork IMH network group model has successfully been expanded to a number of different regions within Ireland (Irish Association for Infant Mental Health, n.d.). As the PIMH network group who participated in the current study is comprised of staff who are predominantly working within AMH services, this group does not represent the traditional model of the IMH network group approach. However, this study highlights that staff participation in an IMH continuous learning group can have benefits for staff, service users and overall service delivery and development. This study contributes to the evidence base supporting the development of knowledge of the IMH model, associated theory and practice implications for staff working within AMH services.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Psychology Research Ethics Committee of University College Cork. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.