Introduction

An enigmatic drawing attributed to Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) in the Louvre represents three views of a mausoleum set in a hilly landscape, crowned with a centrally planned temple (fig. 1).Footnote 1 Variously described as the design for a princely mausoleum or a whimsical archaeological study, the work has long raised questions about its authorship, content, and purpose. In 1977, Etruscologist Marina Martelli observed similarities between the drawing and sixteenth-century descriptions of an Etruscan tomb said to be unearthed in January 1507 at Castellina in Chianti, a village in the Sienese hills about forty-five kilometers south of Florence. She posited that the discovery inspired the controversial drawing, noting that Leonardo traveled to Florence from Milan in September 1507, making a visit to Castellina possible.Footnote 2 Scholars have subsequently accepted Martelli’s thesis, and Leonardo’s authorship of the piece and its link to the Etruscan tomb at Castellina are generally no longer questioned. The drawing has since appeared in numerous publications on Leonardo’s work as an imaginative interpretation of the Etruscan tomb with little further commentary.

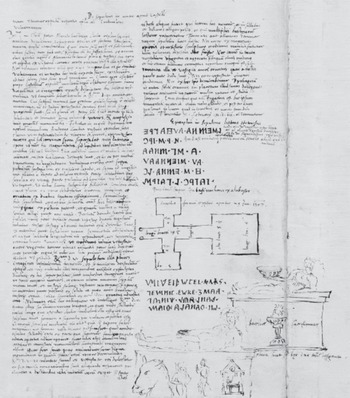

Figure 1. Leonardo da Vinci. Drawing of an Etruscan mausoleum. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Despite this consensus, problems remain concerning the master’s interpretation of Etruscan architecture and its place within his broader oeuvre. First, the mausoleum differs from known Etruscan funerary monuments in its precise symmetry and organization, and the temple crowning the structure would appear more at home in Renaissance Rome than ancient Etruria. These elements are usually attributed to the artist’s architectural ideals and the influence of Roman rather than Etruscan monuments. Such interpretations, however, overlook sixteenth-century ideas about the Etruscans and their architecture, which were shaped as much by regional pride as by the period’s nascent Etruscan archaeology and reading of the ancient authors.Footnote 3 Before assessing Leonardo’s rendering of the Etruscan tomb, therefore, one must consider what he and his contemporaries knew and thought about Etruscan architecture. Second, the drawing is curiously unlike anything else in Leonardo’s oeuvre, even when one accounts for its unusual subject matter. The work’s singularity among Leonardo’s architectural drawings raises questions about the artist’s broader engagement with Etruscan history, art, and architecture.

In addition to these issues, past scholarship has not fully acknowledged the reaction in Florence to the news of the discovery at Castellina and its implications for the Louvre work. In fact, early sources related to the discovery reveal a fascinating picture of one of the best-documented archaeological finds of the sixteenth century.Footnote 4 The tomb is mentioned in numerous sixteenth-century documents, the earliest penned only twelve days after its discovery. The sources attest to a dynamic discussion about the tomb among some of Florence’s leading citizens, including the Florentine chancellor Marcello Virgilio Adriani (1464–1521), Luigi Guicciardini (1478–1521), Cardinal Francesco Soderini (1453–1524), and Giovanni Cavalcanti (1480–1542). Their letters describe the wonder inspired by the tomb’s architecture, as well as by the grave goods and inscriptions found there. A generation later, Florentine scholars Pierfrancesco Giambullari (1495–1555), Piero Vettori (1499–1585), and Santi Marmocchini (d. 1548) continued to discuss the sensational find. Aside from a few scattered references, the modern literature on the Louvre drawing has overlooked this remarkable history. Although texts documenting the discovery have been available in print for some time, none has been the subject of an in-depth investigation, nor have they been considered as a group.

To address these matters, this study offers a new interpretation of the Louvre drawing through a contextual examination of the drawing itself, the sixteenth-century documents concerning the tomb at Castellina, and contemporary views of Etruscan architecture. It situates the work within the lively discourse prompted by the archaeological discovery at Castellina, revealing that it was just one of several representations of the tomb circulating in Florence during the early sixteenth century. These and the texts that accompany them offer clues to the drawing’s intended audience, and resolve some of the outstanding problems concerning its origin, content, and purpose. Next, an analysis of the drawing against contemporary knowledge and attitudes toward Etruscan architecture permits a better understanding of the artist’s conception of the tomb design. Consideration of this material thus provides insight into Leonardo’s work, as well as into contemporary beliefs about the Etruscans and a major episode in the Renaissance recovery of antiquity.

A Singular Drawing

The unusual monument presented on the Louvre sheet has long interested scholars of both Leonardo and Etruscan archaeology, but it has not been the topic of a comprehensive study.Footnote 5 It is, therefore, necessary to begin with a visual analysis and an overview of the scholarly literature in order to position the drawing among Leonardo’s graphic works. Rendered in brown ink and wash over an underdrawing in black chalk, the drawing presents a conical monument from a bird’s-eye view that occupies the top half of a horizontal sheet measuring approximately 20 × 28 cm (7.83 × 10.55 inches). The structure rises at a forty-five-degree slope toward its summit, where it is crowned by a centrally planned shrine reminiscent of Bramante’s Tempietto. Stepped ramps climb from the ground toward the temple on the monument’s left and right sides. About halfway up, a narrow walkway allows access to three post-and-lintel doorways visible on the mausoleum’s front side. On the lower half of the sheet, in direct alignment with the bird’s-eye view above, a circular plan of the uppermost section is organized in concentric rings, with six cross-shaped tomb complexes arranged around a central core. Each tomb consists of three discrete, square chambers connected by a corridor, two smaller lateral ones, and a larger main chamber. Each larger chamber has a small rectangular object at its center, representing perhaps a pillar, burial, or altar. To the right of the plan, another drawing illustrates a sectional view of one of the smaller side chambers, built from courses of long masonry slabs that form a corbeled arch. Inside the chamber, a bench circling the perimeter of the room holds cinerary urns in the shape of vases and rectangular chests.

The previous scholarship on the Louvre piece consists mainly of a series of brief references, in exhibition catalogues, catalogues of Leonardo’s drawings, discussions of Leonardo’s architectural designs, and studies about the knowledge of Etruscan artifacts during the Renaissance. The earliest of these, from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, tend to focus on the questions of authorship and the models that might have informed the artist’s conception. The sheet came to the Louvre in 1856 from the collection of Giuseppe Vallardi, who described it as the “project of a grandiose sepulchral monument in the Ionic order” in his catalogue of Leonardo’s drawings in his possession.Footnote 6 Art historians initially accepted Leonardo’s authorship without controversy, and the drawing was included as the work of the master in the studies of Jean Paul Richter, Heinrich von Geymüller, Eugène Müntz, Giovanni Poggi, and others.Footnote 7 Adolfo Venturi first challenged the attribution in his Storia dell’arte italiana (1938), and in a subsequent publication argued that the drawing did not appear to be Leonardo’s because its hatching runs from right to left. Leonardo’s modeling, he observed, was normally executed with strokes running diagonally downward from left to right, indicating that the artist worked with his left hand. Venturi ascribed the work instead to Francesco di Giorgio on the grounds that the Sienese master’s treatise on architecture contains “very similar drawings.”Footnote 8 A few years later, Allen Stuart Weller noted Venturi’s opinion that Francesco di Giorgio made the work, speculating that it was intended as a project for the mausoleum of Federico da Montefeltro.Footnote 9 André Chastel also doubted the attribution to Leonardo in his Art et humanisme à Florence (1959), adding that he found the drawing “rather cold”; he too posited Francesco di Giorgio as its creator.Footnote 10

Despite the uncertainty raised by Venturi and others, the drawing continued during the mid-twentieth century to appear in publications as Leonardo’s work. Ludwig Heydenreich upheld the attribution in two studies of Leonardo’s architecture, and Geneviève Monnier included it in a volume on architectural drawings in the Louvre.Footnote 11 Carlo Pedretti in particular has insisted on Leonardo’s authorship in multiple publications, and has argued for a date of 1507/08 on the basis of style. He has noted that the quality of the line is similar to some of Leonardo’s other architectural studies of the early 1500s.Footnote 12

A general consensus was reached after 1977, when Martelli first connected the sheet with Renaissance descriptions of the Etruscan tomb uncovered at Castellina in Chianti in the early sixteenth century. She observed that the early sources speak of a cross-shaped tomb constructed with corbeled vaulting, and of the presence of urns with gabled lids of the kind visible in the Louvre piece. She noted that Francesco di Giorgio died in 1502, roughly five years before the purported discovery of the tomb in January 1507, effectively nullifying the attribution to that artist. Leonardo, she suggested, had returned to Florence in September of that year, about eight months after the tomb was unearthed. The Etruscan burial thus provided Leonardo with the general inspiration for his design, which, Martelli writes, he realized without much interest in creating a faithful rendering of the archaeological details.Footnote 13

Since the publication of Martelli’s study, leading Leonardo scholars have come out in favor of attributing the drawing to Leonardo and identifying the tomb at Castellina as the impetus for the design. The work was featured in several significant exhibitions of Leonardo’s oeuvre. It appeared in Leonardo da Vinci, Engineer and Architect, held at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 1987, and was shown in an exhibition of the master’s drawings organized by Martin Kemp and Jane Roberts at the Hayward Gallery, London, in 1989. It was later included in an exhibition of Florentine Renaissance drawings held at the Uffizi Gallery (1992), and in major shows of Leonardo’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2003), and the Palazzo Reale, Milan (2015).Footnote 14 In his book on Leonardo’s architecture, Pedretti notes that the date of 1507, given by Martelli for the discovery at Castellina, is consistent with the drawing’s style, which he had previously assigned to 1507–08. He further stresses the similarities between the work and known drawings by Leonardo, both in the treatment of the landscape and the mausoleum itself.Footnote 15 More recently, Françoise Viatte has remarked that the technique and quality of the draftsmanship are characteristic of the master’s drawings.Footnote 16

As Pedretti and Viatte have emphasized, the Louvre drawing is entirely consistent with Leonardo’s work in technique, style, and quality. The sophistication of the draftsmanship, especially in the lightness of touch in the landscape background, appears foreign to Francesco di Giorgio’s work, whose drawings are comparatively severe, with stronger contours and harsher modeling. It is, however, similar to Leonardo’s landscape studies of ca. 1506, such as Windsor RL (Royal Library) 12405r, which exhibits a comparable looseness in the quality of the line.Footnote 17 Compositionally, the drawing follows an arrangement common in Leonardo’s studies for centrally planned churches, a topic of special interest to the artist in the late 1480s. For example, the church designs on a sheet from Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, MS B, similarly present a centrally planned structure from a bird’s-eye view, together with the plan of the building on the same sheet (fig. 2). Leonardo’s tomb plan is divided into eight segments—six formed by the cross-shaped tomb complexes and the remaining two by the ramps—in a manner that is also analogous to the ground plans of the artist’s centrally planned church designs, which are also often divided into eight parts.Footnote 18

Figure 2. Leonardo da Vinci. Studies for a centrally planned church. Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, MS B 95v (formerly Ashburnham MS 2037, fol. 5v). © RMN (Institut de France) / Art Resource, NY.

While clearly Leonardesque in these general ways, the work also presents details that suggest a date close to the time of the tomb discovery, as Pedretti has argued. The use of pen and ink to reinforce a preliminary drawing in black chalk is common in his later drawings, as Leonardo began to turn away from red chalk in the early 1500s.Footnote 19 Although it is true that drawings from throughout his career present the left-to-right diagonal hatching that Venturi and others observed, around 1500 the artist began experimenting with the technique of modeling with curved, parallel lines that follow the forms of his subjects.Footnote 20 This method of shading is visible throughout the Louvre drawing, but especially along the mausoleum’s right side. It was precisely this approach to hatching that led Venturi to reject the attribution to Leonardo, but the technique is employed in numerous drawings undisputedly by the master’s hand. A series of anatomical studies of 1510 at Windsor (RL 19005), for example, show little trace of the artist’s characteristic diagonal left-to-right hatching, but were modeled instead with relatively short strokes that follow the longitudinal direction of the figure’s muscles.Footnote 21 Closer examples are found in the diagrams of siphons that illustrate the Codex Leicester, which Leonardo began in 1508.Footnote 22 Here, the curved, parallel strokes of the Louvre mausoleum are employed to suggest the objects’ three-dimensional, cylindrical form (fig. 3). Pedretti long ago argued that the architectural precision of the Louvre work is like that of the fortress in the Codex Atlanticus; it can be added that the curved hatching in the towers is also similar.Footnote 23

Figure 3. Leonardo da Vinci. Drawings of siphons. Codex Leicester, detail of sheet 3B (back), fol. 34r. Collection of Bill Gates, Seattle, Washington. © bgC3.

Beyond the problem of attribution, Martelli’s study sheds important light on the drawing’s content by identifying the Etruscan tomb at Castellina as its subject. While it seems clear that this tomb inspired the artist’s conception, Leonardo’s mausoleum differs from real Etruscan architecture in important ways. The careful symmetry, regularity, and organization of the tomb, crowned by a round peripteral temple, seem more akin to High Renaissance architectural ideals, especially that of the centrally planned church. The organization of the six cross-shaped tomb chambers, tightly ordered around a single circular core, is also unlike anything excavated from ancient Etruria. Probably for these reasons, scholars have proposed various other sources for Leonardo’s conception, from specific ancient monuments to the artist’s imagination. Heydenreich, for instance, refers to the work as deriving from Leonardo’s fantasia razionale, or rational imagination, and proposes Bramante’s Tempietto as an inspiration for the work.Footnote 24 Kemp similarly suggests that in the drawing Leonardo aimed “to surpass the builders of the seven wonders of the world, such as the architect of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, and even to rival the engineering feats of nature herself.”Footnote 25 Kemp posits that Leonardo was also inspired by Roman models, particularly the great imperial mausolea of Hadrian (now the Castel S. Angelo) and especially of Augustus, which has a comparable tiered structure and radial chambers.Footnote 26 Various scholars have also noted that the low, stepped dome with an open oculus of Leonardo’s tempietto is without precedent in Etruscan architecture, but resembles the roof of the Pantheon.Footnote 27

Whatever their views on Leonardo’s particular antique and Renaissance sources, all of these interpretations present a similar narrative of the drawing’s genesis: Leonardo, inspired by an exciting discovery, created the work as a hypothetical exercise in which he juxtaposed non-Etruscan forms with a vague idea of Etruscan architecture. One is left imagining that the artist, driven by his boundless curiosity, journeyed to Castellina to investigate the ruins. Then, following Roman models and his architectural vision, he created an ideal restoration of a monument for no other purpose than to explore an idea.Footnote 28

The interpretation of the drawing as a hypothetical or even whimsical study poses several problems. First, the piece does not fit neatly among the architectural studies with which it is usually compared. In fact, it does not appear to be a study at all; it is finished and lacks Leonardo’s characteristic notes. The composition, with its careful alignment of plan and elevation, is atypical of the artist’s architectural drawings, as is the landscape setting. These elements are hard to reconcile with the comparatively rough sketches that comprise Leonardo’s images of centrally planned churches. The drawing’s singularity among Leonardo’s architectural works is, moreover, inconsistent with the artist’s tendency to return to a theme repeatedly in order to explore it in depth. Of the thousands of Leonardo’s drawings that survive, only this one concerns the Etruscans, and few deal with the excavation of ancient monuments at all.Footnote 29

These issues suggest that the drawing was conceived neither as a theoretical architectural study nor solely to satisfy his personal curiosity about the Etruscan tomb. Its level of finish and precise organization, the absence of annotations, and its landscape setting all point to a finished work that Leonardo made for someone else. In fact, Leonardo made a number of similarly finished drawings throughout his career, each likely for a specific recipient and purpose. Several of his maps of Tuscany (RL 12278, RL 12683), for example, are richly detailed and accented with color, and the towns are labeled in a precise left-to-right script, versus Leonardo’s usual right-to-left, all of this suggesting that they were intended for an audience other than Leonardo himself.Footnote 30 That Leonardo should have created such a drawing of an Etruscan subject is not surprising; Renaissance collectors often called upon artists to provide their expertise on matters concerning antiquities. As Francis Ames-Lewis has discussed, Leonardo is known to have created drawings of antique and other themes for this purpose. In 1502, Isabella d’Este asked her agent to find an artist in Florence “such as Leonardo” to make drawings of four antique hardstone vases that were formerly in the collection of Lorenzo de’ Medici. Writing from Mantua, Isabella was interested in purchasing one or more of the vases, and relied on Leonardo’s abilities as a draftsman to reach a decision. Leonardo not only provided the requested drawings, which are now lost, but also offered his judgment on the quality of the vases.Footnote 31

Rather than a hypothetical study, the Louvre drawing should be understood alongside such consulting projects. One can easily imagine that, in the aftermath of the discovery at Castellina, Leonardo was called upon to re-create the tomb in graphic form. In fact, the sixteenth-century accounts of the discovery at Castellina in Chianti present a clear cultural context for such an assignment. A contextual examination of these accounts reveals the circumstances surrounding the creation of Leonardo’s work, as well as their value as evidence for the tomb itself.Footnote 32 Together they document the enthusiastic response that the Castellina tomb prompted among Florentines in the first half of the sixteenth century, and provide further clues to the intended function and audience of Leonardo’s work.

A Sensational Find

The body of sixteenth-century texts that record the discovery at Castellina is small but illuminating. The best known accounts are from two Florentine treatises dating to the 1540s: Pierfrancesco Giambullari’s Il Gello, published in 1546 and revised in 1549, and Santi Marmocchini’s Dialogo in defensione della lingua toschana (Dialogue in defense of the Tuscan language), an unpublished work of about 1547.Footnote 33 The two texts are dialogues on the origin and development of the Florentine vernacular, a popular topic among Florentine men of letters in these years. Giambullari was a member of the Florentine Academy and a client of Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (r. 1537–74). Together with his colleague Giambattista Gelli, after whom his treatise is named, he sought to demonstrate that the Etruscans founded the city of Florence before the ascendancy of Rome, and that its vernacular descended from Aramaic via its early Tuscan settlers.Footnote 34 To this end, Giambullari appeals to Etruscan inscriptions, arguing that the right-to-left orientation of the Etruscan script and its perceived similarity to Hebrew show that it was based on Aramaic. He points to Etruscan inscriptions found on “many very ancient stones” from “different places in Tuscany,” including Gubbio, Volterra, and Viterbo.Footnote 35 In this context, the academician offers his brief account of the discovery of the tomb at Castellina in Chianti. “In 1507,” Giambullari writes, “on January 29, near Castellina, during the digging of a vineyard, an underground chamber was discovered, twenty braccia long, five high, and three wide, with certain parts protruding on either side, where statues, ashes, ornaments, and Etruscan inscriptions were found. And I would be happy to show you, if you like, a copy of them, which our most learned Piero Vettori has shown and given to me.” Giambullari then turns to the next Etruscan inscriptions on his list, found on “many tablets, also with Etruscan letters.”Footnote 36

A second, more detailed account of the tomb, from Marmocchini’s Dialogo, survives in one known manuscript copy in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.Footnote 37 An outsider to the Florentine Academy and the ducal milieu, Marmocchini was a Dominican friar and expert on ancient languages who resided at the convent of Santa Maria Novella. In his dedicatory letter to Cosimo I, Marmocchini affirms his purpose to defend the Tuscan language from Latinists who claim that it “comes from the Latin language and has been corrupted by women, children, servants and slaves, Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Lombards, the French, and other ultramontanes.”Footnote 38 Like Giambullari, he sought to demonstrate the vernacular’s origin in ancient Semitic languages through the Etruscan founders of Florence. He also appealed to Etruscan antiquities to illustrate his points, and his treatise is remarkable for the information he provides about these ancient works. His description of the tomb is considerably more detailed than Giambullari’s. At Castellina, he writes,

there is a hillock where, in the year of our lord 1507, on January 29, at the eighteenth hour, a certain di Lando was planting a vineyard and making a hole with an iron shovel in order to plant a vine, when the shovel fell into an ancient tomb of the Etruscans, and a fetid odor emerged from the chasm. Toward the road, a door was discovered sealed with slabs of alberese stone, along with a room in the shape of a cross. [The tomb’s] length was twenty braccia, and there was a corridor three braccia wide where nothing was found. On the left side there was a chamber, five braccia in width, length, and height, with clay vases filled with the ashes of people of low class, as well as certain vases where the bodies were burned. To the right, the nobles were buried, and on a table [there were] the ornaments of a queen.

The friar goes on to recount a lavish array of grave goods, including a silver mirror, silver and gold jewelry, a chest full of rings, and the bust of a woman carved from alabaster, adorned with gold. He then describes “a sculpture of a woman with a bowl in hand, and her name was there, in Etruscan characters.” There were also “precious stones and leaves of silver of such a quantity that they were sold in Siena, and I spoke to the goldsmith who bought them.” The tomb itself was “vaulted without mortar, with great, wide slabs, which, from one course to another, little by little and one above the other, got closer together until they met at the center.”Footnote 39

On the manuscript page below Marmocchini’s description, a simple drawing records the cruciform plan of the tomb (fig. 4). The burial chamber extends from left to right across the page, its dimensions given as twenty braccia long, five high, and three wide, or about 11.5 × 29 × 1.75 meters.Footnote 40 Two side chambers, connected to the rest of the tomb by short, narrow corridors, form the transept of the cross, their dimensions marked “br. 5 per ogni verso” (“five braccia in each direction”). To the right of the plan is the suggestion of another, larger chamber, the width of which extends as far as the smaller side chambers on the east and west sides. On the left side, the entrance to the tomb is labeled “janua ad meridiem” (“entrance to the south”). Additional notes on the drawing transcribe Etruscan inscriptions and describe where in the tomb they were found.

Figure 4. Santi Marmocchini. Dialogo in defensione della lingua toschana, ca. 1541–47. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Fondo Magliabechiano, Classe XXVIII, cod. 20, fol. 14r. Courtesy of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. All rights reserved.

Archaeologists have looked at Giambullari and Marmocchini in an effort to identify the specific Etruscan tomb that was discovered in the early sixteenth century. As evidence for the tomb itself, however, the two authors must be treated with caution. Their treatises were penned in the 1540s, more than thirty years after the events they describe. Additionally, they appear to be derivative sources, relying on evidence received secondhand; Giambullari states openly that he acquired his information from the Florentine philologist Piero Vettori, “a most diligent investigator of antique things.”Footnote 41 Vettori was a child at the time of the discovery, so he too could have had only indirect knowledge of the events surrounding the discovery and the tomb’s contents. Parts of Marmocchini’s description are also unlikely to be from direct observation, despite its liveliness and detail. The treatise itself is written in the vernacular, and the work’s major premise concerns the primacy of the vernacular over Latin. But the annotations on his diagram of the tomb are in Latin, suggesting that Marmocchini consulted a source in that language that was available at the time. Additionally, he indicates that he spoke with the Sienese goldsmith who purchased some of the grave goods, but not that he visited the tomb itself; this is significant because his purpose in this part of the treatise is to demonstrate his firsthand experience with Etruscan objects. In any case, Giambullari and Marmocchini were neither antiquaries nor even impartial observers of Etruscan artifacts, which they manipulated to support their scholarly theses about the Florentine vernacular.Footnote 42

As sources, however, Giambullari and Marmocchini provide clear testimony to the lasting impression the discovery at Castellina made on Florentine scholars. They show that information about the tomb was still circulating in Florence nearly four decades after the discovery, and was available to an elderly friar and ducal client alike. Their descriptions are in fact similar enough to suggest that they relied on the same earlier source or sources. Details concerning the date of the find and the accidental discovery during the digging of a vineyard suggest that a narrative of the discovery had crystalized by the time of their writing. The dimensions they give for the monument are also the same, something hardly to be expected if each had conducted his own investigation of the tomb chamber. Both express an interest, even wonder, in the array of grave goods before turning to the inscriptions that were their primary concern.

A page of the Codex Pighianus, a collection of antiquarian material in the Staatsbibliothek of Berlin, preserves evidence closer to the find, and might even have informed the sources used by Marmocchini and Giambullari.Footnote 43 The codex was compiled by Stephanus Winandus Pighius (1520–1604), a Dutch antiquary who made drawings of ancient sculpture and copies of inscriptions in Rome in the mid-sixteenth century. The page presents a transcription in Pighius’s hand of a letter addressed to “The Cardinal of Volterra.”Footnote 44 It is signed Florence, 10 February 1507, leaving the author unnamed. The cardinal of Volterra named as the recipient can be identified as Francesco Soderini, the brother of Piero Soderini, gonfaloniere a vita of the Florentine Republic from 1502 to 1512. Francesco was bishop of Volterra from 1478 until 1509 and was appointed cardinal of the Roman Church in 1503.Footnote 45 Part archaeological description, part meditation on the transience of civilization, the letter appears to fall into that category of humanist epistolary intended not for the recipient alone, as attested by its scholarly Latin language and the existence of the copy.Footnote 46

The author begins by extolling the wealth and power of the Etruscans, observing that Livy and other “renowned and credible authorities” attest to the excellence of the Etruscans in politics, wealth, and fortune. Yet he posits that archaeological remains, “excavated from the innermost parts of the earth in our lands and towns,” provide even better evidence of Etruscan greatness. To illustrate this point, he turns to “a tomb very recently unearthed in the Chianti, near the town of Castellina,” relating how Andreas Landus, “well known for his work in farming,” unearthed a vaulted cavern while preparing a patch of ground for a vineyard.Footnote 47 Like Marmocchini, he describes the vault of the tomb as created without mortar, from courses of stone arranged in layers so as to adjoin at the apex. Among other things he notes “seemingly unlimited” clay urns topped with peaked lids, images of youths engaged in sport and embracing, and the effigy of a woman, decorated with gold leaf, holding a golden bowl.Footnote 48 Marveling at the numerous Etruscan inscriptions, the author appeals to the cardinal to “see if by chance there is anyone [in Rome] conversant with these characters, and could deduce their meaning.” The letter closes, Ozymandias-like, with musings on the ravages of time: “I certainly believe from the majesty of the work and its craftsmanship that the burial belonged to men of great fortune… . And yet, for all their preparation and care, except for a few small ashes … nothing was discovered of their mortals remains.”Footnote 49

At the lower right of the page, a drawing displays the cruciform plan of the tomb, along with copies of Etruscan inscriptions and the sketches of two sarcophagi (fig. 5). The plan’s horizontal orientation matches the diagram in Marmocchini’s manuscript. An opening on its left is labeled ad meridiem, indicating the tomb’s south-facing entrance. As in Marmocchini, two side chambers extend to the east and west, forming the transept of the cross. Their width is marked as five braccia, while the two small corridors leading into them are listed as 2⅓ braccia. To the right/north side, there is the larger, nearly square chamber only hinted at in Marmocchini, its dimensions given as 5½ × 6 braccia. The length of the entire tomb from entrance to far wall is given as 19½ braccia—versus Marmocchini’s and Giambullari’s twenty—while the width of the main corridor matches the later authors’ width of three braccia. Along with these measurements, notes record Etruscan inscriptions and, as in Marmocchini, where they were found. A note immediately above the plan indicates the date the tomb was discovered as 29 January 1507.

Figure 5. Letter to Cardinal Francesco Soderini, 10 February 1508, as transcribed in the Codex Pighianus. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Manuscript Department, MS Lat. fol. 61, fol. 55v.

In the literature on the Castellina find, the author of the Pighianus letter is generally described as anonymous, but his identity is revealed in two letters that Cardinal Soderini wrote in reply. The first of these was published by Angelo Maria Bandini in 1752.Footnote 50 It is signed “Cardinal Soderini of Volterra” and bears the date 23 February 1508. In it, Soderini expresses gratitude and appreciation for the detailed portrayal of the tomb, praising both “the antiquity of the discovery” and “the exceptional eloquence” of the letter itself, noting that “nothing in that ancient work could be so finely fashioned … that it could not be equaled, or even surpassed, by your description of it.” The cardinal assures the recipient that he will make every effort to find someone able to read the Etruscan inscriptions, but cautions that it will “be an exceedingly difficult task.”Footnote 51 Italy had faced such incursions, he writes, that Latin itself had nearly been lost, and was only restored through the careful study of Latin texts. But no Etruscan books or speakers remained to mount a similar study of that language. Furthermore, Leon Battista Alberti, “the most learned man of our age,” declared the language undecipherable; if Alberti couldn’t read Etruscan, Soderini writes, “I judge that my efforts, and yours, will come to naught.”Footnote 52

Soderini’s epistle is addressed to “the most excellent and outstanding scholar Lord Marcello, Secretary of Florence, my dear friend.” This can only be Marcello Virgilio Adriani (1464–1521), first chancellor of the Florentine Republic from his appointment to the post in 1498 until the return of the Medici from exile in 1512. Although less known today than his more famous colleague Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), who served alongside Adriani as second chancellor, Adriani was a significant figure in his own right. He had been a pupil of Cristofero Landino (1424–98) and Angelo Poliziano (1454–94), and, after Poliziano’s death, he was appointed chair of the Florentine Studio. His scholarly work consists mainly of official documents, orations, and academic lectures, most of which remain unpublished, and a Latin translation of Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica, which was published in 1518.Footnote 53

A second letter, dated 1 January 1509, confirms Adriani as the author of the Pighianus missive; it is addressed “to the magnificent and outstanding scholar Lord Marcello Virgilio, Secretary of Florence.” Soderini relates that he has had no success finding a translator of the Etruscan inscriptions: “[I have sent them] through all of Italy,” he states, “but I’ve found no-one who could decipher them.” Instead, the cardinal offers a different gift to reciprocate the chancellor’s earlier epistle, an excerpt from Tacitus’s Annals in which Florence is mentioned, so that Adriani might “rejoice with me in the antiquity of our fatherland.”Footnote 54

While the correspondence between the first chancellor of Florence and Cardinal Soderini provides the best evidence of Florentine responses to the tomb at Castellina, further testimony comes from a letter written by Giovanni di Lorenzo Cavalcanti from Rome to Luigi Guicciardini in Florence, dated 26 February 1508. Cavalcanti was a merchant from one of Florence’s oldest and most prestigious families, who years earlier had sent Guicciardini notice of the memorable discovery of the Laocoön, in January 1506.Footnote 55 In return, he had received from Guicciardini a drawing of the Etruscan tomb. Guicciardini’s original missive and drawing remain untraced, but Cavalcanti’s reply nonetheless provides another clue that both descriptions and drawings of the Etruscan tomb were circulating among interested Florentines in the aftermath of the discovery. Cavalcanti writes that he has “received … the drawing of the burial found at Castellina with certain Etruscan inscriptions, which, as ignorant as I am, gave me much satisfaction.” To continue their exchange, Cavalcanti offers Guicciardini a gift of a “booklet that deals with similar topics, which I am sending … with this letter to thank you for your kindness and friendship.”Footnote 56

The letters of Adriani, Soderini, Cavalcanti, and Guicciardini together attest to the enthusiasm with which Florentines greeted the news from Castellina and to the dynamic conversation that it generated.Footnote 57 They illustrate that the Florentine interest in ancient Etruria was not exclusively a Medicean phenomenon, even though more scholarly attention has been given to the appropriation of Etruscan themes in Florence under Medici rule. As the historiography of the foundation of Florence makes clear, Florentines had long been interested in their region’s Etruscan heritage. A tradition extending at least to the thirteenth century held that, although established by the Romans, the ancient city of Florentia was inhabited by Romans and Etruscans alike, the latter having settled in the new city after the Romans destroyed their nearby home of Fiesole.Footnote 58 In the 1420s, Leonardo Bruni celebrated the legacy of Etruria and praised Etruscan wealth, power, and religious piety in his Historiae, and Florentine humanists from Salutati to Machiavelli all emphasized the role of the Etruscans in founding the city.Footnote 59

In addition to this long-standing narrative, the Etruscans achieved new importance around 1500 thanks to the work of Annius of Viterbo, erstwhile papal theologian and notorious forger of ancient texts. Annius’s Antiquitates, a lengthy compendium of forgeries dealing with Italy’s prehistory, was published in Rome in 1498, just a decade before the discovery at Castellina.Footnote 60 Annius’s work presented new, if spurious, evidence of Florence’s Etruscan past. In a protracted narrative, the text traces the origin of Etruria to the biblical Noah, who for Annius was the same as the pagan god Janus. After the biblical Flood, Noah/Janus and his plentiful offspring repopulated the Italian Peninsula, founding cities and civilizing the people. Florence in turn was established by Hercules “the Egyptian,” scion of the Egyptian king Osiris, and settled by the Etruscan people of the Fiesole and Arignano. This narrative granted Florence both an illustrious founder and a legacy far more ancient than Rome; indeed, Rome was relatively new in Annius’s version of Italian history. The Antiquitates stirred excitement, contempt, and often confusion among Florentine scholars of the sixteenth century. Even as respected humanists denounced the work as a forgery, Annian ideas appeared in the work of Florentine authors, including Bernardo Cerretani and Fra Mariano da Firenze, of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Even Poliziano cited an (earlier) Annian forgery in his letter to Piero de’ Medici on the origin of Florence.Footnote 61 Later, in the 1540s, Gelli, Giambullari, and Marmocchini made use of Annius’s texts in their treatises about the foundation of Florence and the development of its language. Whether embraced or despised, the Antiquitates drew renewed attention to Italy’s Etruscan past, establishing a legacy to compete with and even surpass that of Rome.

Given this background, it is no wonder that the tomb at Castellina, brimming with gems, precious metals, and inscriptions, provoked such amazement in Florentine observers. The early sources on the tomb discovery also have a number of more specific, previously unrecognized implications for Leonardo’s drawing. They establish the year of the discovery as 29 January 1508, and not 1507 as universally given by modern art historians and archaeologists. The Florentine calendar began on March 25, the feast of the Incarnation, so a date of January 1507 corresponds to 1508 in modern terms.Footnote 62 The date in the Pighianus letter in fact bears the words ab incarnatione (since the Incarnation), so there can be no doubt about the year the author intended. Soderini’s first reply, dated 23 February 1508, is addressed from Rome, which did not follow the ab incarnatione system; it was therefore written roughly two weeks after the Pighianus missive. Understanding the correct year is crucial because Leonardo was in Florence in January 1508, but not in January 1507. He had returned to Florence from Milan between 15 August and 18 September 1507, in order to settle a dispute with his brothers over their father’s estate, and he remained there until the following April.Footnote 63 Leonardo was thus in Tuscany at the peak of the excitement about the discovery and not eight months later, as formerly thought, after the enthusiasm might have cooled and the grave goods were dispersed. The drawing must date to the first months of 1508, since it is unlikely that the artist should have pursued the subject after his return to Milan. Leonardo’s drawing is thus exactly contemporary with the earliest documented responses to the discovery at Castellina.

In addition to establishing a general context, the letters circulating about the tomb provide insight into the Louvre drawing’s purpose. The correspondence of Adriani, Soderini, Cavalcanti, and Guicciardini was above all an exchange of antiquarian material, offered between friends as tokens of affection. Adriani’s letter offers news of the discovery, presented in eloquent Latin prose, to which Soderini responds with a promise to assist Adriani with the Etruscan inscriptions. When his efforts are unsuccessful, the cardinal offers a manuscript of Tacitus in lieu of the hoped-for translations. Next, there is the lost letter about the tomb from Guicciardini to Cavalcanti, which itself reciprocates a letter about the discovery of the Laocoön that Cavalcanti sent some years before. Cavalcanti, in turn, counters with a libretto, now lost, “with similar topics”—probably Etruscan inscriptions. Each offering is accompanied by declarations of friendship and a fair amount of flattery: Soderini gushes about the beauty of Adriani’s prose, and Cavalcanti offers his gift as an expression of gratitude for Guicciardini’s “kindness and friendship.”

Crucially, both Adriani and Guicciardini included drawings of the tomb as part of this exchange. Adriani’s letter mentions four such drawings: a diagram (diagramma), an image (imago), and the illustrations of two sarcophagi. Cavalcanti acknowledges that he has received “the drawing of the burial found at Castellina” (“il disegno della sepoltura trouata alla Castellina”) from Guicciardini. Although the original drawings are lost, these references to them express the desire among these men to visualize the tomb in text and image, and show that they too were considered important signs of friendship. Given this context, surely Leonardo’s drawing was intended for such a purpose, for one of the individuals who responded enthusiastically to the discovery and who wished to share news of it with a friend or colleague.

In the first decade of the 1500s, Leonardo had access to a network of learned men who would have appreciated such a drawing. A page in the Codex Arundel indicates that in March 1508 Leonardo was lodging at the house of Piero di Braccio Martelli (1468–1525), a Florentine art patron and author of several books on mathematical themes.Footnote 64 Martelli is often cited as the link between Leonardo and the sculptor Gian Francesco Rustici, who was living in the same house. From a prominent Florentine family, Martelli was also in a position to offer Leonardo access to some of Florence’s leading political and literary men.Footnote 65 He was active in the meetings of the Orti Oricellari between 1502 and 1506, a series of gatherings hosted by Bernardo Rucellai in his garden on Via della Scala where men of letters discussed historical, literary, and antiquarian topics. The participants in this phase of the meetings included such scholars as Francesco da Diacceto, Giovanni Corsi, Francesco Vettori, and Pietro Crinito.Footnote 66 Much has also been made of Leonardo’s acquaintance and possible friendship with Niccolò Machiavelli, whom he had the occasion to meet during his service with Cesare Borgia in 1502–03. References in the work of these men place the Etruscans among their historical and antiquarian interests: Crinito’s De honesta disciplina (1504) includes two chapters on the Etruscan religion,Footnote 67 and Machiavelli would later discuss the role of the Etruscans in his account of the foundation of Florence.Footnote 68

Leonardo’s drawing might have been made for one of these men, but the most likely recipient was perhaps Adriani himself. As first chancellor, Adriani certainly had the stature to acquire a work by Leonardo, who was internationally famous by 1508. Given the interest and pride in the Etruscans expressed in his letter to Soderini, Adriani would have appreciated Leonardo’s image of the tomb at Castellina since, as discussed above, his letter refers to four such drawings. One passage is particularly compelling: “I have included with this letter,” writes the chancellor, “a diagram and an accurate drawing [imaginem exacte descriptam], so that all might be perceived as if it were before the eyes of His Most Reverend Lordship.”Footnote 69 While the copy of Adriani’s letter in the Codex Pighianus includes a plan, no other drawing of the tomb is to be found. Either Pighius chose not to record the second image in his copy, or the drawing had been separated from the letter by the time Pighius transcribed it. Either way, Adriani’s “accurate drawing” remains unaccounted for, raising the possibility that it was Leonardo’s. The drawing must have been detailed enough to allow the cardinal to envision the tomb “as if it were before the eyes,” perhaps requiring the use of a separate sheet and the skill of a professional artist such as Leonardo. Leonardo had the occasion to meet Adriani while he was working on his fresco of the Battle of Anghiari just a few years earlier for the Great Council Chamber of the Palazzo della Signoria; Alessandro Cecchi has in fact argued that the first chancellor developed the subject matter of Leonardo’s painting.Footnote 70 Having abandoned this commission in order to work for the French governor of Milan just a few years before, Leonardo now found himself in the awkward position of having returned to Florence for personal reasons, a situation surely noticed by the officers of the Florentine Republic. Leonardo might have wished to appease a disgruntled Adriani with a reconstruction of the Etruscan tomb.

Unfortunately, Adriani’s original letter to Soderini remains untraced, along with the drawings that accompanied it. But whoever the recipient, Leonardo’s grand, conical monument is clearly no isolated drawing of an Etruscan tomb. Although singular in the artist’s body of work, it finds counterparts in the visual and textual descriptions of the Castellina tomb that circulated in Florence in the first half of the sixteenth century. Offered as gestures of friendship, they expressed their authors’ amazement at the tomb and its contents, and appealed to Florentine pride in the ancient history of Tuscany. So too must have Leonardo’s drawing: the grandeur of the structure reflects wonder at the power of the Etruscans. But as much as anything, the drawing and the letters reveal their authors’ desire to visualize the Castellina tomb so, as Adriani claimed, “all might be perceived as if it were before the eyes.”

Leonardo and the Response to Etruscan Building

If, like the other drawings circulating about the tomb discovery, Leonardo’s work was an antiquarian gift intended to re-create the tomb for a learned recipient, then it follows that it reflects the artist’s or the recipient’s actual ideas about Etruscan tomb architecture. Clearly, the drawing represents a much grander structure than that suggested in the Renaissance accounts. The sources document the discovery of only one tomb complex, not six, and there is no mention of a shrine crowning the structure. In his efforts to restore the entire monument in visual form, therefore, Leonardo had to rely on sources other than the single tomb complex uncovered in 1508. As discussed above, scholars usually assume that these sources were Roman monuments and ideas about the centrally planned church. Few scholars have looked beyond the Castellina tomb for Etruscan models, however, and contemporary views of Etruscan architecture have not been taken into account.Footnote 71 It is therefore necessary to examine the drawing’s relationship with real Etruscan architecture, beginning with the Castellina tomb, and also with ideas about Etruscan building as gleaned from Pliny and Vitruvius.

The drawing presents clear affinities with the early descriptions of the Castellina tomb. As Martelli has discussed, each of the six cross-shaped tomb complexes has a similar shape to the plan illustrated in the Codex Pighianus, with its square main chamber and two smaller side spaces. While Martelli observed that they are less like the plan given by Marmocchini, the discrepancy is easily resolved when one recognizes that Marmocchini’s drawing is not to scale.Footnote 72 In addition, the corbeled entrance of the chamber in Leonardo’s drawing recalls Marmocchini’s description of a tomb “vaulted without mortar, with great, wide slabs, which, from one course to another, little by little and one above the other, got closer together until they met at the center.” Adriani also describes the vault as constructed with “overlapping stones lying on top of one another so as to be self-supporting.”Footnote 73 He further mentions a structure, “raised on a vertical base, narrowing at the top,” in the center of the burial chamber. Here Adriani seems to be referring to a large pillar, a feature of such Etruscan burials as the tomb of La Montagnola, near Florence, and the Inghirami tomb, Volterra. If so, it could correspond to the square object that Leonardo drew in each of the larger chambers of his tomb complexes. A look into the side chamber is also revealing. Marmocchini describes a mensa on which grave goods were placed, similar to the bench shown in the drawing. While it is true that Leonardo has not included the richly sculpted sarcophagi that prompted wonder in Adriani and Marmocchini, the rectangular urns within the chamber do recall Adriani’s description of “clay urns, seemingly unlimited in number … topped by two tiles, like a gabled roof.”Footnote 74 Marmocchini describes the left chamber as containing modest “clay vases full of ashes” intended for the poor,Footnote 75 a description not unlike the simple, undecorated urns presented in Leonardo’s work.

In addition to the sixteenth-century accounts, a comparison between the Louvre drawing and known Etruscan monuments reveals the archaeological nature of Leonardo’s work. Scholars have long observed the similarities between Leonardo’s monument and the Etruscan tumulus of Montecalvario, a great Orientalizing mausoleum of the seventh century BCE, excavated near Castellina in the early twentieth century.Footnote 76 The two tombs are similar enough that many scholars believe that Montecalvario, which had been looted before the twentieth-century excavation, was the tomb discovered in 1508 (fig. 6).Footnote 77 Like the structure depicted in the Louvre drawing, Montecalvario is an imposing conical monument, about fifty-three meters in diameter, built over multiple cross-shaped tomb complexes organized according to the cardinal directions. Each chamber is constructed of roughhewn alberese limestone, like the tomb described in the Renaissance sources, and is roofed with a corbeled vault comparable to the ones depicted in Leonardo’s drawing (fig. 7). Although Montecalvario has only four tombs in contrast to Leonardo’s six, it is possible that Leonardo understood that it had multiple burial complexes but simply misjudged their number.

Figure 6. Tumulus of Montecalvario, plan, Castellina in Chianti. Luigi Pernier, “Montecalvario, presso Castellina in Chianti: Grande tumulo con ipogei paleoetruschi sul poggio di Montecalvario.” Notizie degli Scavi 13 (1916): fig. 2, page 265.

Figure 7. Tumulus of Montecalvario, section of the western hypogeum, Castellina in Chianti. Luigi A. Milani, “Montecalvario-Ipogeo paleoetrusco di Montecalvario presso Castellina in Chianti.” Notizie degli Scavi 2 (1905): fig. 5, page 229.

Despite this evidence, the identification of Montecalvario with the tomb discovered in 1508 poses numerous problems, which Nancy de Grummond has outlined in a recent study.Footnote 78 An Etruscologist specializing in the Chianti area, De Grummond notes that the measurements taken by Pernier during his excavation of the site in 1915 do not match those given in the Renaissance sources. Additionally, the corbeling in Leonardo’s drawing runs in a direction contrary to that of the tombs at Montecalvario, and no benches like the ones lining Leonardo’s burial chamber have been found anywhere at Montecalvario. Above all, the Renaissance sources describe grave goods from the Hellenistic period only; at Montecalvario, in contrast, both the fragments found during the twentieth-century excavations and the monument itself are securely dated to the Orientalizing period, and no Hellenistic objects were discovered. Although the Etruscans are known to have reused much older tomb monuments for their burials, such extensive reuse is not known to have occurred, and there is no evidence that Montecalvario was reused in this way.Footnote 79

Whatever the case, it is not necessary to trace the specific tomb that was discovered in 1508 to recognize that the conical form with its cross-shaped chambers finds its closest precedents in Etruscan tomb architecture, especially Orientalizing tumuli. In addition to the corbeled vaulting and cross-shaped burial complexes, numerous features of Leonardo’s work find parallels in these grand Etruscan monuments. The upper section of the structure, formed by a wall capped by an earthen mound, is a feature of many tumuli, such as the second Great Tumulus at Cerveteri (fig. 8). The post-and-lintel entryways through the wall also have precedents in the necropoleis of Cerveteri. Stepped ramps, carved in tufa or built with stone blocks, leading to the top of tumuli, have been found across Etruria. Etruscologists, for example, have recently reconstructed a grand stairway from remains found at the Melone del Sodo II, a sixth-century BCE tumulus at Cortona (fig. 9). They believe that this structure served as an altar, but also led to an aedicule on the tumulus itself.Footnote 80

Figure 8. Great Tumulus II, Banditaccia Necropolis, Cerveteri. Scala / Ministero per i Beni e le Attività culturali / Art Resource, NY.

Figure 9. Melone del Sodo II Tumulus, Cortona. Author’s photo.

Although Leonardo probably did not know these specific examples, there is evidence that Etruscan tombs were known in Renaissance Italy. The tomb of La Mula, an Etruscan tholos tomb near Sesto Fiorentino, was known at least since the late fifteenth century, as indicated by an inscription above the right doorjamb of the entrance.Footnote 81 Like the tomb discovered in 1508, La Mula is a corbeled construction of alberese slabs. Further evidence of the knowledge of Etruscan tombs comes from a letter from the humanist Antonio Ivano da Sarzana to Nicodemo Tranchedini da Pontremoli, which documents the discovery of a tomb near Volterra in 1466 holding carved stone cinerary urns and clay vases. John Spencer published part of the letter in 1966, observing that the author’s dispassionate tone, expressing little surprise, suggests that it was not the first such discovery.Footnote 82 Adriani himself wrote to Soderini that Etruscan objects were continuously being unearthed in Tuscany, no doubt from Etruscan tombs, and alludes to his familiarity with them. As noted above, his letter begins with a reference to the many Etruscan antiquities unearthed in Tuscany, so many in fact that “I do not wish to give an account here of everything ever found, both at Volterra and our own city, since I believe that a tomb recently unearthed in the Chianti near the town of Castellina will suffice.”Footnote 83 Indeed, scholars have long recognized that Etruscan urns were known in fifteenth-century Italy, and very likely earlier as well, and all of them had to come from a tomb at one point or another.Footnote 84

Leonardo, therefore, had access to Etruscan tombs from which to draw information about Etruscan funerary architecture. He and his contemporaries could easily recognize these monuments as Etruscan by the inscriptions on the grave goods they housed; it had been known at least since the time of Alberti that the Etruscan language and alphabet differed from those of Greece and Rome.Footnote 85 While there is no evidence that any of the tombs known in the early sixteenth century were tumuli, this is not surprising since there are no descriptions of the exterior tomb architecture in any of the early sources, and, with the notable exception of La Mula and possibly Montecalvario, none of them has ever been traced. The letters of Antonio da Sarzana, Adriani, and others clearly show that Florentine humanists followed such discoveries with interest.

The conical form of Leonardo’s monument, the cross shape of the tomb complexes, and the corbeled vaulting thus all find precedents in Etruscan architecture. The colossal size of the monument, suggested by its scale with respect to the surrounding hills, also might derive from Renaissance ideas about Etruscan, rather than Renaissance or Roman, architecture. In his letter, Adriani states that the burial was so lavish that it was worthy of a king, and urges Soderini to see if the sarcophagi or cinerary urns belonged “to Tarchon or other Etruscan kings, for I certainly believe from the majesty of the work and its craftsmanship that these remains belong to men of great fortune.”Footnote 86 In the Renaissance the only Etruscan royal burial known from the ancient authors was the tomb of Lars Porsenna, king of Etruscan Clusium and Rome’s great adversary. Pliny describes the colossal structure in his Natural History, drawing on a now-lost passage of Varro. Built at Clusium, Porsenna’s mausoleum included a labyrinth so great that anyone who entered it would never emerge. Above it stood fourteen pyramids on three levels, from which hung bells that chimed with the wind. The structure was so grand that Pliny denounced it as “insane folly … to have courted fame by spending for the benefit of none and to have exhausted furthermore the resources of a kingdom.”Footnote 87 Pliny’s account captured the imagination of Renaissance architects Filarete, Antonio da Sangallo, and Baldassare Peruzzi, who attempted to reconstruct the mausoleum in their drawings.Footnote 88 More generally, the size of Leonardo’s mausoleum is consistent with Renaissance ideas about the great power and wealth of the Etruscans.

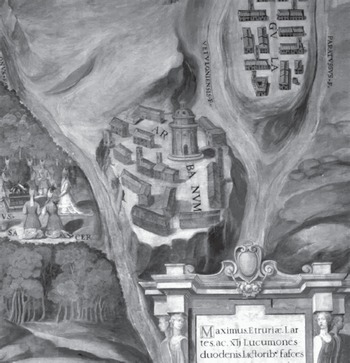

Even the tempietto crowning the structure, which is usually compared to Roman or Renaissance architecture, may reflect sixteenth-century ideas about Etruscan building. A look at Renaissance editions of Vitruvius suggests some confusion about the Roman architect’s discussion of Etruscan temples, as they invariably place the Roman author’s passages on circular temples in book 4, chapter 7, “De tuscanicis rationibus aedium sacrarum” (“On the Tuscan manner of sacred temples”). This arrangement is first evident in the 1486 editio princeps of Giovanni Sulpizio, and it continues to appear throughout the sixteenth century. In contrast, most modern editions of Vitruvius place round temples in their own chapter, so that round temples are discussed in book 4, chapter 8.Footnote 89 That Renaissance editors of Vitruvius included round and Etruscan temples in the same chapter could suggest that they believed the round temple had its origin in Etruria. Sixteenth-century readers of Vitruvius, moreover, might conclude that the round temple was an Etruscan form. Sebastiano Serlio seems to have understood round temples this way: in a description of a Tuscan portal from his Extraordinario libro di architettura (Extraordinary book of architecture, 1551), he notes, “its columns are ten widths in height, since this is how Vitruvius describes them on Tuscan work on the circular temple.”Footnote 90 A round temple is found in a fresco narrating the Etruscan origins of Viterbo, located in the Palazzo Comunale of the same city (fig. 10). Painted by Baldassare Croce in 1588, the fresco portrays a circular temple dominating the image of an early Etruscan settlement. Ingrid Rowland has argued that the most famous round peripteral temple of all, Bramante’s Tempietto, on the Janiculum Hill in Rome, was imbued with Etruscan significance during the sixteenth century. Located on the left bank of the Tiber, the Janiculum was considered geographically part of Etruria, and was described thus in both ancient and Renaissance texts. Annius of Viterbo describes the hill’s founder, Janus, as a kind of protopontiff and mythological type of Peter, whose crucifixion the Tempietto commemorates. Like Peter, Janus’s attribute is the key, and he is described in Renaissance sources as the bearer of the keys to heaven.Footnote 91 Rowland does not go so far as to suggest that the round form itself was perceived as Etruscan, but Jack Freiberg makes such an interpretation in his book on Bramante’s Tempietto. Freiberg draws attention to a drawing from the circle of Francesco di Giorgio in which the temple of the Capitoline, famously built under Rome’s last Etruscan king, is depicted as a round, peripteral structure.Footnote 92

Figure 10. Baldassare Croce. Detail of Etruscan City of Viterbo, 1588. Palazzo Comunale, Viterbo. De Agostini Picture Library / S. Vannini / Bridgeman Images.

Conclusion

The round temple appears in too many different contexts to have been a signifier of the Etruscan civilization alone. On the other hand, given the erudite antiquarian context from which Leonardo’s drawing emerged, it is reasonable to conclude that a careful reading of Vitruvius’s text informed the design of the round temple. It is logical that Leonardo would look to the textual accounts of Pliny and Vitruvius for direction, because these are precisely the sources with which humanists like Adriani and Soderini were familiar. Those texts reveal an image of Etruscan architecture that conforms to Leonardo’s design: a colossal mausoleum designed for an Etruscan king, crowned by a round, peripteral temple in the Etruscan manner. In early 1508, in the wake of the sensational discovery at Castellina in Chianti, Leonardo thus created something quite different than a whimsical interpretation of a tomb that captured his imagination. Rather, he made a reasoned restoration of a real Etruscan monument, informed by textual sources and known Etruscan remains, to satisfy the archaeological interests and the dynamics of friendship of the work’s recipient.