The National Conference of Niger, which was meant to lay the foundations for a democratic regime in the country, took place between 29 July and 3 November 1991. It brought together representatives from various sections of Nigerien society and was the culmination of several years of mobilization against the violence of the existing military regime and its economic and social direction. The reduction in public expenses that followed the signature of an initial structural adjustment programme (SAP) with international financial institutions in the early 1980s had led to major demonstrations that were violently repressed by the authorities. Demonstrations increased in the early 1990s, when the government announced new austerity and liberalization measures and the adoption of a new SAP. It was therefore not unexpected that the delegates to the National Conference would reject any new adjustment policy in 1991, at the same time as the country was undertaking a process of democratization. The first free, multi-party elections in the country's history were held in February 1993. A few months later, the elected government, which was made up in part of people who had marched against the military regime and its liberalization policies in the previous decade, announced that negotiations with the financial institutions would be restarted with a view to adopting a new SAP. When the devaluation of the CFA franc led to a sudden increase in prices in January 1994, the social climate became plagued with deep tensions, intensified by partisan struggles. The new regime was overturned by the army in January 1996, with most people not mobilizing to protect the democratic institutions.Footnote 1

This story brings others to mind. In the early 1990s, many countries in sub-Saharan Africa experienced social revolts against authoritarian regimes that had imposed structural adjustments, which produced democratization processes, the pursuit of adjustments by the democratically elected governments, and the overturn of those elected governments a few years later.Footnote 2 Parallels can also be drawn with the Arab Spring revolts that broke out in 2011, founded on aspirations for democracy and improved living conditions, but leading to great disappointment and eventually the restoration of authoritarian rule. As far as Europe is concerned, it might be reminiscent of the trajectory of Greece in 2015, at least in its early stages, when it experienced significant social movements and the installation of a new government that ultimately was forced to bend to international demands and establish a policy that its members had fought against before coming to power.

Every story has its own specific elements, but there is one that links them all: they bring different opposing rationales into play. In the 1990s, a return to an adjustment policy seemed to many Nigeriens to be inconsistent: how could a democratic government that had just been installed close down public services, reduce wages, devalue the currency, increase prices, and generally do the opposite of what it had been elected to do? At the same time, the adoption of an adjustment programme seemed to the international financial institutions to be extremely rational, given the catastrophic state of Nigerien public expenses: how could a poor country continue to spend more than it earned? It is not a question of treating these different rationales – economic and political – as separate, watertight spheres: military coups d’état could also have an economic cost, as prior debates on the relationship between democracy and development suggest.Footnote 3 It is more a question of anchoring them within actual rivalries in order to see how, by whom, and in what form they were strenuously contested during the democratization process of the 1990s, before “the right thing” was imposed. This will lead us to reflect more generally on the question of rationality and politics. While the idea that there are no other possible policies – the famous “there is no alternative” – has lent legitimacy to the adoption of liberal economic reforms in many democratic societies for about forty years, it is important to see how what is rational from one standpoint can seem totally absurd from another, and how what are perceived as legitimate rationales may be the result of conflicts and power relations.

In this article, I will also seek to provide a social history of adjustments, with a particular focus on how they have been received by the people, following the “politics from below” approach.Footnote 4 Structural adjustment programmes have been subjected to numerous critical interpretations of their social effects, in particular through the prisms of education or health.Footnote 5 Their propensity for making the poor even more fragile has been widely highlighted, including – retrospectively – by the people who initiated them.Footnote 6 However, this critical interpretation, which is based on sources mobilized by international institutions to understand the effects of their policies, has essentially remained a history from within.Footnote 7 There are scarcely any popular histories of adjustments that might make it possible to reflect on how they were connected to local political dynamics, and in particular to aspirations for democracy.Footnote 8 It is to this area of thought that this article wishes to contribute, starting with the case of Niger, where adjustments have reconfigured antagonism, produced violence and left traces in the political imaginary in a way that still seems particularly enlightening today.

This work is based on a number of different forms of research conducted in Niamey over a period of ten years, the most recent of which, in 2019, specifically examined the association between democratization and structural adjustments. I have relied on written Nigerien sources, in particular the transcriptions of the discussions at the National Conference, and the press, which was opening up with unprecedented pluralism at the time: these archives reflect not only social mobilizations and grand political plans, but also the general atmosphere and sentiment, and a spirit of the time made up of hopes, expectations, and disappointments. I will also draw on interviews conducted with individuals who took part in the social struggles of the 1980s and 1990s, in particular members of associations and trade unions, as well as people who did not belong to political organizations but who experienced the moment through discussions on street corners and events in their daily lives.Footnote 9 Using these different sources as my starting point, the challenge, from a narrative standpoint, is to tell a story with an unhappy ending, albeit one punctuated by moments of popular joy. While inviting an “eventful conception” of temporality,Footnote 10 I will also focus on each of these moments individually, without interpreting them in the light of what happened later.

WHEN “ADJUSTED” PEOPLES ASPIRED TO DEMOCRACY

In present-day Niamey, it is not easy to imagine a time when, for a large number of Nigeriens, democracy offered the prospect of not only greater participation in political life by everybody, but also an improvement in living conditions. It is more common to recall the democratization of the 1990s as a catastrophe from this standpoint. In order to imagine a moment such as this, one must plunge back into the social revolts and everyday discontent that marked the end of the authoritarian regime, distinguishing between this story and the memories its protagonists may have of it, informed by what happened subsequently. More broadly, contrary to any retrospective constructivism, it means asking what makes it possible from the sources to understand what other futures might have been possible and envisaged by those who lived through those times.Footnote 11

The torments of the “conjoncture”

At the beginning of the 1980s, Niger was under an authoritarian government. The single-party regime that had been established under President Diori Hamani at the time of independence was overturned by a coup d’état in 1974, and the country passed into the control of a Supreme Military Council (CMS) led by Lieutenant Colonel Seyni Kountché until 1987. During this period, visible protests were limited: opposition parties were banned, mobilizations were strictly monitored, and the workers’ unions, which were part of the Union des Syndicats des Travailleurs du Niger (USTN), practiced “responsible participation”, to use its leaders’ terminology.Footnote 12 This did not prevent ordinary anger from being displayed towards the regime, although its forms and purposes are hard to decipher because it was essentially situated outside the most expected political spaces, and cannot be inferred from mobilizations.Footnote 13

We will begin with the fact that the 1980s corresponded with a period of greater material difficulties for the Nigerien working classes, compared with the second half of the 1970s. Following the fall of President Diori Hamani, the country's economy had enjoyed a relative boom thanks to uranium, its main extractive resource, exports of which had quadrupled, with prices rising to five times between 1974 and 1980. In the first place, this benefited foreign companies, which owned almost seventy per cent of the share capital of the uranium mines, but it also translated into a significant increase in the Nigerien state's resources, enabling it to build schools and clinics, support manufacturing, and develop public services, while also greatly increasing wages, with the minimum wage more than doubling over five years.Footnote 14 By contrast, some data identify a stagnation, or even a deterioration, in living conditions in the 1980s. Whereas the number of primary school teachers doubled between 1975 and 1980, it increased by just twenty-five per cent between 1981 and 1986, which only made it possible to keep the average number of pupils per class at forty-three.Footnote 15 The number of Nigerien doctors peaked in 1980, and fell during the remainder of the decade, while the number of nurses grew slower than the population.Footnote 16 Domestic household water consumption, which increased steadily during the 1970s, fell suddenly in the 1980s, while a drop in food production led to a famine in the middle of the decade.Footnote 17

The 1980s was also the exact period when an SAP was implemented in Niger. Faced with a decline in the price of uranium, the Nigerien government saw its external debt quadruple between 1980 and 1982, becoming a third of the country's gross domestic product.Footnote 18 This led Niger to enter into negotiations with international financial institutions, which, following a process of ideological transformation, had made liberalization the first condition for the development of the African continent.Footnote 19 In 1982, an initial “stabilization programme” signed with the IMF imposed significant budget cuts and economic liberalization measures, while allowing the government to restructure its external debt. Four similar agreements were signed between 1983 and 1986, which, taken as a whole, constituted Niger's first SAP.Footnote 20

While this period has remained in the collective memory as a time of great difficulties, there is nothing to indicate that the Nigerien people attributed their problems to the adjustment policies at the time. The first SAP was barely mentioned in the press, except retroactively some years later,Footnote 21 and the very concept of “adjustment” was still unknown to many people.Footnote 22 It was another term with economic connotations that became used as a popular way to describe the difficulties affecting the population, or the “conjuncture” (“downturn”). Initially used by Nigerien political leaders to mean an “economic downturn” after the years of development supported by income from uranium, “conjuncture” rapidly became part of the vocabulary of daily life. One also sees it being used in the press and in university writings from the early 1980s,Footnote 23 as well as in ordinary, everyday conversations, including those in Djerma, Tamasheq, and Peul (the country's main languages). Everyone used the word “conjuncture”, even if they did not speak French. In the words of a retired former government official, “everyone [understood] everyone who said, ‘there's the conjoncture’, ‘there's the conjoncture’”.Footnote 24 The great popularization of the word in Nigerien society showed a popular propensity for appropriating economic objects and giving them a new meaning associated with its own reality.Footnote 25

Not everyone shared the same concept of what the “conjuncture” was, however. Everybody had had a particular experience of it, even though one person's memory would partially reflect someone else's and produce a shared memory for both of them. One of its great manifestations, which is cited repeatedly, is that “there was no money” or that “it wasn't circulating”.Footnote 26 In the 1980s, the “conjuncture” therefore became a customary reason for rejecting requests for material assistance from one's family circle. A usual way of addressing these requests was to say in Haoussa: “abokina yanzou babou koudi, conjoncture tche” (“My friend, there's nothing, there's a downturn”).Footnote 27 This lack of money in circulation limited opportunities for remunerative business activities as well as informal solidarity relationships, which was inconsistent with people's moral representations of the proper functioning of the economy.Footnote 28

Another way in which the “conjuncture” manifested itself markedly was through price increases or, more covertly, through operations aimed at camouflaging the increase by changing the weight or volume of consumer goods. Hence the “conjuncture” is sometimes recalled as a moment when litres stop being “real litres” and kilos stopped being “real kilos”.Footnote 29 These operations left a trace in the vernacular names given to consumer goods. The best-known example is the bottle used for Braniger, the most widely consumed beer in the country: in 1986, it went from 66 to 48 centilitres with no change in price, which led its consumers to call it “the conjoncture”.Footnote 30 Another example was bread: consumption had increased since the 1970s under the influence of international aid, but its per-unit price was changed regularly by official decree. Today, if one asks a bread seller for a “quarter of a baguette”, he cuts it into three pieces and takes a piece: in other words, a whole baguette is made up of three “quarters” (both in French and in the local languages). This can lead to assumptions about the past, as we see in this interview with a man who was born during the “conjuncture”, and his wife:

Me: How many quarters are there in a loaf of bread?

The wife: Three.

Her husband interrupts: No, no, four. “Quarters” means that it's divided into four.

She replies: Yes, but there are three quarters in a baguette, no? I'm talking about bread. As for the rest, I don't know [laughter]. Maybe when you were small, baguettes were bigger.Footnote 31

One last frequently cited manifestation of the “conjuncture” was the increased difficultly in attaining salaried status, which has a tangible and moral resonance that goes beyond just the salaried workers. After independence, the development of salaried employment gave rise to strong expectations, not only because its tangible repercussions had multiplied due to redistribution, but also because it supported shared ways of expressing expectations of justice from the authorities, particularly in urban spaces.Footnote 32 The “conjuncture” years corresponded to a period when these salary resources dried up: while the number of salary earners quadrupled in the private sector during the 1970s, it declined in the 1980s.Footnote 33 The number of government employees increased tenfold between 1961 and 1984, before stagnating.Footnote 34 Even today, this drop in salary resources is still remembered – through repeated failures to pass the civil service entrance examinations, the scarcity of offers of employment, or the loss of a family member's job – as is the resentment this caused towards the regime of the time.Footnote 35

The fact that this decade-long downturn period meant years of material problems was nothing exceptional in itself: the previous decade had also been noteworthy for the most significant episodes of drought and famine since the beginning of the twentieth century, which associated the whole of Sahel with great poverty in collective perceptions for many years.Footnote 36 What was new about the 1980s, which led to the popularity of the word “conjoncture”, was more the fact that a central significance in these problems, which were experienced by most people on a daily basis, was attributed if not to the direction of the economic policies, then certainly to the economy itself.

Economic anger, political anger

Although this powerful economic resentment translated into only a limited number of protests in an extremely authoritarian context, they were not totally non-existent. At the time, the principal protest force was the Union des Scolaires Nigériens (USN). Formed in 1960, it initially brought together the country's college and high-school students, as well as Nigerien students abroad. With the opening of the University of Niamey in 1973, the USN experienced a growth that led to a larger number of strikes and protests in the country that went far beyond teaching issues.Footnote 37 A study of these mobilizations reveals an increasingly close association between challenging the repressive dimension of the military government and its economic direction in the context of the adjustments: the USN played an important role in this combined rejection of authoritarianism and liberalization policies during the 1980s.

The tracts written by the USN offer a good overview of its activities. They were carefully collected by the French consular services as part of the surveillance of the former colony, making it possible to utilize them today to gauge the evolution of the union body during a period of adjustment. In the 1970s and 1980s, the tracts focused on living conditions, not only in schools and universities, but also in the country as a whole due to the impact of repeated droughts. Significantly, the most important movements led by the USN in this period took place in 1973, 1976, and 1983, all years of significant national food shortages.Footnote 38 During these years, the image of a “hungry people” was a recurring one in the tracts distributed in Niamey, along with scholarships, student housing, and the organization of examinations. This image had a literal significance in the country as a significant segment of the population suffered from hunger and malnutrition, but it also had a more metaphorical meaning, in that the authorities’ responsibility for the production of food and the image of the granary state are a fundamental register of political legitimacy.Footnote 39

In the 1980s, the government's economic direction, apart from the question of people's living conditions, became a more significant motive for mobilizations by school and university students. The first stabilization programme, which was signed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1982, imposed significant budget cuts for the civil service. The effects of this were immediately visible in the education sector: the government adopted a declaration known as “Zinder”, which proposed that the State's education costs be transferred to the parents of pupils and to local governments.Footnote 40 This was when the World Bank and the IMF made their first appearance in USN tracts, signalling a notable development in its discourse. Although it had always had an international dimension, France had been the focus of criticism up to that time, whether it was a question of its “companies [giving up] the country to imperialism”,Footnote 41 its “neo-colonial” government,Footnote 42 or its head of state, who was presented as the “President of the French Republics of Africa”.Footnote 43 In the early 1980s, the Bretton Woods institutions became a new target of the USN, which accused the CMS of “delivering the country bound hand and foot into the jaws of the IMF” after it signed a new stabilization agreement in 1983.Footnote 44

This new development overlapped with a growing rejection of authoritarianism, while Seyni Kountché's regime hardened its attitude towards protests. In May 1983, against the backdrop of the rejection of the Zinder declaration, the USN's mobilizations gave rise to extensive repression. Starting from a highly localized conflict,Footnote 45 they led to the largest protest demonstration Niamey had seen since independence, bringing together “a thousand people”,Footnote 46 according to the French Embassy, and “several thousand” according to the USN.Footnote 47 The authorities reacted violently: dozens of students were imprisoned in a military camp, while others were forcibly recruited into the government administration and sent to regions far from the capital. One of them, Amadou Boubakar, died during interrogation due to “isolation after a slightly overlong march”, according to the official version relayed by the French Ambassador, so that there was “no reason to doubt it”.Footnote 48 This repression put an end to the USN's demonstrations for several years. Officially, it was dissolved, but it continued its struggle against the reductions in public expenses and government violence, the central focus of tracts that continued to be written clandestinely.

“Structural adjustment” was still a relatively abstract notion, however, even among the most militant pupils and students. The latter saw the changes in economic policies through their daily realities far more than through the prism of an ideological struggle against liberalism. Immediately after the signature of the stabilization programme, the Nigerien government put a stop to free school supplies in primary schools and decided to end boarding at colleges and high schools, which was a very real penalty for all the young people who needed to find accommodation because they had come from their villages to study in the city. A similar measure that has remained in the memory shows the way in which liberalization policies were perceived in practice as being relevant to both a new economic direction on the part of the government and the brutality of power:Footnote 49 stopping boarding meant both reducing public expenses and putting an end to potential hotbeds of dissent in the country, because it was often in these places that pupils and students met to write their tracts and prepare their demonstrations.

The implementation of a policy to ease tension by General Ali Saibou, who came to power after the death of Seyni Kountché in 1987, encouraged renewed mobilizations. Local chapters of the USN, which no longer had any legal existence, re-formed in schools and universities. The Union des Etudiants Nigériens de l’Université de Niamey (UENUN), in particular, became the spearhead of the protest movement. The Nigerien government therefore embarked on the “Education III” project, which was established in 1987 by the World Bank for sub-Saharan countries, and which led to new budget reductions in the education sector.Footnote 50 The criteria for granting scholarships were revised to be more selective, and the “programme policy”, which guaranteed that students would be recruited into government jobs when they went to university, was abandoned. This had a powerful impact because of the challenges access to the Civil Service by a family member posed for his or her family. This project gave greater visibility to the role of international financial institutions in the country's economic policies. As the country's first independent newspaper explained some years later: “The World Bank entered the Nigerien vocabulary at the time of Education III.”Footnote 51 Aside from the education issue, economic liberalization became the target of USN tracts, which castigated a “structural adjustment policy [that] leads to the privatization of a certain number of companies and state offices and to the closure of certain sectors that are judged by the international financial bodies to be unprofitable”.Footnote 52

At the end of the day, the mobilizations of the 1980s reveal the tangible profile the adjustment gradually acquired among the people who were most invested in the protests within Nigerien society, as well as the political meaning they initially attributed to it. As we know, in many countries, the new liberal doxa was imposed in authoritarian contexts, “the export of liberalism” by international institutions having preceded the call for democracy.Footnote 53 It is also important to understand, however, what this chronology means through people's representations: in Niger, neoliberal policies were first seen as the product of a military regime before later being associated with democracy.

From anger to revolt: 1990

On 9 February 1990, Niger experienced a day of insurrection that undoubtedly marks the history of the country to this day, first because of the bloodshed (three demonstrators killed by soldiers and many others injured), but also because of its effects: the day played a key role in the democratization of the country. It was therefore an “event”: that is, to use Sewell's approach, facts that modified the structure of the society within which they were produced.Footnote 54 By retracing what happened on that day, the various motives that drove its participants, the elements that made it possible, and its immediate ramifications, it becomes possible to show that the revolt was against both authoritarianism and structural adjustment, to the point where it is difficult to distinguish which of them inspired the protesters that year.

At the beginning of 1990, the student activism led by the USN was thriving. Among the most common issues of concern were rejection of the Education III project promoted by the World Bank and the question of scholarships, accommodation, and employment opportunities, as well as political freedoms and rejection of the brutality of the military regime, memories of which were very much alive on the university campus. General assemblies were held in an area that had been baptized “Place AB” in memory of Amadou Boubakar, who had been killed in 1983. A large demonstration was planned for 9 February 1990 in defence of a five-point platform of demands that included access to university works for all students, access to registration, teacher recruitment, the withdrawal of the Education III project, and legal recognition of the USN, which was still officially banned.Footnote 55 One of the practical challenges for the organizers was how to cross the bridge linking the University District on the right bank to the rest of the city. Many saw it as an “insurmountable obstacle”:Footnote 56 in previous years, students had made a habit of crossing it by night in small groups on the eve of demonstrations and then assembling in Place de la Concertation, which began to emerge as a “place of anger”.Footnote 57

On the morning of 9 February, there was a widespread feeling of danger on campus: in addition to the memory of Amadou Boukaré, the fate reserved for similar demonstrators on the continent was a feature of all the discussions. Less than a year earlier, the repression of a demonstration in Lubumbashi in Zaire had led to the death of a student (according to the official report).Footnote 58 Some elected “to drink […] a litre of whisky or pastis before days of action, [as that] gives you more courage on the marches”.Footnote 59 In the centre of the city, an initial gathering in Place de la Concertation was dispersed at dawn with truncheons, and the bridge was guarded by around a hundred police officers, who were ordered not to let the demonstrators through.Footnote 60

When the demonstrators arrived at the police barrier, a delegation asked the officers to allow them through, but the authorities refused, instead ordering them to disperse. Tear gas was used, and the students responded by throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails, while covering their faces with wet handkerchiefs so they could breathe.Footnote 61 The police called in reinforcements from the Republican Guard, the Gendarmerie, and the Fire Service, in line with the “foreseen plan of action”, as those responsible for operations in the field explained later.Footnote 62 The troops opened fire. For many students, it was the first time they had heard the crack of gunfire, and when they saw demonstrators falling, they understood that they were real bullets.Footnote 63 Panic set in, and the demonstrators retreated towards the university campus. Three protesters were killed on the bridge: Alio Nahanchi; Maman Saguirou; and Issaka Kaïné.

The day was a tipping point in protests against the regime. After what the government organ called a “regrettable blunder”,Footnote 64 protests intensified and spread to other sectors of society. The three students who had been killed on 9 February were buried the following day, after a silent march that included not only students, but also their families and parent associations, as well as locals who had no ties to the victims. Some people recall that as their first demonstration, although they were just children at the time.Footnote 65 On 16 February, there was another protest march, which the USTN joined, marking a turning point in the history of the country's biggest workers’ trade union. This demonstration was given a religious dimension, with the trade unionists referring to a Muslim practice of reciting verses from the Koran in memory of the dead a week after their deaths. This allowed people to express their “support along the way, murmuring ‘Allahou Akbar’”.Footnote 66 Although many do not recognize themselves in this practice, because a good number of trade unionists looked more to historical materialism than they did to spirituality,Footnote 67 it nonetheless contributed to the expansion of a struggle to which everyone was able to attribute their own meaning.

The shift also lent support to the very purpose of the mobilizations. Up to that time, it had been above all about opposing the violence of the regime while struggling for better living conditions. After 9 February, the establishment of democratic institutions became a full-blown cause. It was driven by a favourable international climate due to similar struggles taking place in neighbouring countries, led by Benin, where a National Conference declaring itself to be sovereign had just been formed.Footnote 68 The mobilized populations referred primarily to local realities, however. Although the university year was declared to be “white” (meaning that no diplomas would be validated), students and workers increased the numbers of demonstrations to denounce the government's responsibility for the “massacre of 9 February”, while also demanding political openness. Ali Saibou's government was obliged to retreat in the face of these protests, giving the USN legal recognition and allowing greater freedom of expression. In May, the first independent newspaper, Haské (“Clarity” in Haoussa) saw the light of day. On 15 June 1990, the Higher Council for National Orientation, the country's principal government authority, recommended a revision of the Constitution with a view to the development of democratic pluralism.Footnote 69 It was five days before the Franco-African Summit in La Baule, which went virtually unnoticed in Niamey.Footnote 70

The demand for democracy, however, was closely linked to material expectations that expressed themselves through an increasingly widespread rejection of structural adjustment policies, even as pressure from international financial institutions increased. After a visit to Niger by a World Bank-IMF mission, the prime minister announced the adoption of a framework economic policy document in September 1990, prior to the signature of a new SAP calling for the “reduction of the wage bill”, “the privatization of public enterprises”, and “the dissolution of those for which it has been determined that there is no possibility of a turnaround”.Footnote 71 The protests against the regime, where it was now possible to hear slogans like “the SAP will not pass!”,Footnote 72 multiplied and increasingly radical methods were adopted. In Niamey, road transport trade unions blocked traffic, leading to violent clashes between the police and protesters, several of whom were arrested.Footnote 73 In other towns, students attacked symbols of the state, including the police station in Maradi, which was stoned, and the Court in Arlit, which was attacked with clubs.Footnote 74 For its part, the USTN organized a five-day inter-profession strike, during which Niamey saw its largest protest since independence. Some days later, Ali Saibou proclaimed a multi-party system, and announced that a National Conference would shortly be summoned. Haské enthusiastically proclaimed that these were “days that will turn everything around”:

Today's establishment of a multi-party system in Niger is the result of the pressure put on the government by the latest five-day strike. The strike is, of course, part of a series of protest movements driven principally by the trade unions and students, the most dramatic of which was the massacre of 9 February. But due to the extent of its outcome (a virtually total paralysis of all the country's activities) and the demonstration of strength to which it gave rise (almost a hundred thousand people took to the streets in Niamey alone), [this mobilization] shows that the social instability is […] an expression of profound discontent.Footnote 75

At the beginning of the 1990s, virtually the whole of sub-Saharan Africa experienced a wave of democratization following the events in Niger. Contrary to analyses that stress the role played by exogenous factors, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the summit in La Baule, it is now acknowledged that these transformations were more fundamentally related to local dynamics that revealed the historical narrative of democratic practices on the African continent.Footnote 76 However, only very rarely has any study had the objective of studying the actual course of mobilizations (especially if one makes a comparison with what was done at the same time in other parts of the world, in particular Eastern Europe), or studying the “crowd” phenomena taking place in the streets, almost experimentally revealing how these mobilizations can “take off” and, in a manner of speaking, “stick”.Footnote 77 In the case of Niger, a new look at this process clearly reveals a close connection between democratic struggles, state violence, and structural adjustments, to the point where rejection of the SAP became an important element of political legitimacy for those who took to the streets against the military regime.

THE FALL

From 29 July 1991 to 27 January 1996: these two historic dates are barely four and a half years apart. The former is when the Nigerien Conference opened at a time of shared optimism,Footnote 78 while the latter is the date of a military coup d’état that led to a sense of resignation, and even drew some support among a good part of the population.Footnote 79 Here, it is not a question of putting the internal and external causes into perspective – following a dialectic of inside and outside – in the fall of Nigerien democracy less than five years after it had been established. The issue is to show that this emerging democracy saw immediately what was possible, albeit impeded by the liberal economic policy that was imposed on it, not only because it limited the ability of the new leaders to act, but also because it conflicted with the political imaginaries that had led to the social revolt against the military regime in the first place.

Starting from joy

It was a beautiful scene, so much so that some spectators report that its main protagonist slightly overplayed his role.Footnote 80 It was 15 August 1991 and André Salifou had just been appointed to lead the presidium charged with coordinating the work of the National Conference. He rose to speak to thank his opponent, who had withdrawn in his favour. His voice broke, and he crouched down and hid his eyes while the over 1,000 delegates who had gathered in a packed sports hall stood to applaud.Footnote 81 The scene reveals a particular moment in Nigerien history, one charged with emotion, which is not easy to retrace if one only uses oral memories. When this moment is invoked in the streets of Niamey, the accounts related about it often devalue or deride it. What took place later influences these accounts, because we know what happened after the conference, i.e. four and a half years of social tension, opposition along party lines, and disappointments, culminating in a coup d’état. When listening to various sources, the whole problem lies with recreating the emotional tone of the initial moment without weighing it down with the feelings that came later.

In the months preceding the conference, events that would have seemed unthinkable just a few years earlier reflected people's high spirits. One of the most remarkable of these was the women's marches demanding a greater place in future debates. When the National Committee for the Preparation of the National Conference (CNPCN) met in May 1991, it had only one female participant, who resigned in protest against the male hegemony. A large march organized on 13 May from Place de la Concertation brought thousands of women together (see Figures 1 and 2). There were banners that read “No to the Conference without women”, “Discrimination” and “We defend our rights”.Footnote 82 Four days later, a group of women blocked the discussions at the CNPCN, booing the participants who were already in the building and preventing others from accessing it. One of the initiators of this action, who was a trade unionist, castigated the idea that a preparatory committee should only include men on the pretext that it was “technical”.Footnote 83 Six new women were eventually admitted to the committee.Footnote 84

Figures 1 and 2. Women's demonstration before the National Conference. Photographs published in Haské, 1–30 May 1991 and Le Sahel, 14 May 1991.

The selection of the delegates to the National Conference was also a matter of controversy at times. At the end of its work, the CNPN called for 1,204 delegates representing the political parties, the trade unions (nearly all of which were affiliated with the USTN or the USN), employers, and the government.Footnote 85 Although most of the delegates were selected internally by their own organizations, their selections also gave rise to public opposition, particularly as regards the representatives from the so-called rural world. The CNPN had only provided for sixty-four delegates for each of the country's rural districts, explaining that the farmers were “politically unorganised, and therefore fragile and easily corrupted” by the government.Footnote 86 They were the only members of the National Conference whose representation was territorial rather than organizational. In certain districts, there was a rivalry among farmers caused by the ongoing transformations and cooperatives, which were the main organized rural structures and answered to the prefectures. The delegate from Gouré, Aliou Aboubakar, explained that he had succeeded in having himself appointed before the cooperatives from the district tried to send their own candidate to Niamey. At the conference, he became the best-known representative of the rural world, to the point where he pursued his future political career under the name “Monde Rural”, which he kept until the end of his life.Footnote 87

On 29 July 1991, President Ali Saibou “declared the conference of the living forces of the nation open”.Footnote 88 It rained hard that day. A USN representative who was staying on the university campus alongside delegates from the rural world recalls them showing their joy, mocking a military regime that was able to block everything, “even the rain for the harvests”.Footnote 89 The following day, the headline in Haské read “How great democracy is”, while discussing the “conference of every hope”, with photos showing the smiling faces of women and men with raised fists.Footnote 90 Even the government organ Le Sahel had to acknowledge that “joy could be read on every face”.Footnote 91 On the second day, the National Conference declared itself sovereign, thereby relegating Ali Saibou and his government to the background.Footnote 92 The Seyni Kountché Sports Complex, where the conference was held, was renamed the Stade du 29 Juillet, while the crossroads giving on to the Niger Bridge was named Place des Martyrs in memory of the great demonstration that had been brutally suppressed a year and a half earlier.Footnote 93

Apart from these most significant initial decisions, the period of the conference was characterized by a totally new kind of freedom of expression in a country where one might have been afraid of picking up a tract a few years earlier. As the co-founder of the first Nigerien satirical magazine, Le Paon africain, recalls, “[p]eople were not afraid to talk; it was new. Even [in government bodies] there was a free tone; you could find caricatures of the Head of Government […]. It had never been seen before”.Footnote 94 That an acting president should have to step aside before a conference that proclaimed itself sovereign, that a head of state should be obliged to explain his actions, that military officers could be challenged by civilians – these were all things even the most optimistic activists would not have been able to imagine at the beginning of the decade.Footnote 95 Even those who are now the most critical of the conference retain a lingering sense of how exceptional it was, which permeates their interviews almost in spite of themselves. An elderly inhabitant of the area around the Petit Marché started out talking about “deceit” and “settling accounts” before comparing the National Conference of Niger to those taking place in other West African countries at the same time:

Ours was an exceptional conference. It wasn't like the others. […] It lasted at least, almost three months. It was the longest, longer than Benin or Mali. In Lomé [Togo], when it began, it was one month. Only one month. Eyadema said: “One month, and that's all, and your sovereignty, that's in the hall down there, and it stays down there”. Here, they sacked the President of the Republic. They got someone else. The President of the Republic didn't represent anything. The President was separate. They did what they liked.Footnote 96

Of course, the conference did not enjoy the same reception from every sector of society in 1991. It was monitored especially closely at the university, where students decided to remain on campus for the entire summer. General meetings were arranged in the evenings to talk about the discussions of the day and prepare for the next one with the USN representatives. As one explained, “we built fires in front of the buildings, we drank tea, we quoted Che Guevara and Marx, and we had the feeling that we were heirs to the revolutionaries”.Footnote 97 Civil servants, even those who worked far from Niamey, also followed the Conference very closely. Many said they had listened to the meetings on the radio every day, including one teacher in a village in the centre of the country: “All the civil servants had a lot of hope”, he explained, and “this did not only include the civil servants, as their wages helped many family members to live, apart from their wives and children”.Footnote 98 The widespread distribution of newspapers also testifies to the interest these workers took in the discussions that were under way: the circulation of Haské reached 15,000 copies during the National Conference (compared with 5,000 earlier), figures that no Nigerien news organization has ever seen since.Footnote 99

The welcome the conference received went beyond the social classes who were originally the most directly concerned, however, this is harder to measure. The Office de Radiodiffusion et de Télévision du Niger (ORTN) broadcast the meetings daily in the country's various national languages, which enabled those who did not speak French to follow the discussions. What was new about these broadcasts compared to the usual news relays needs to be assessed. Up to then, it had little room for the unexpected, because it was monitored and censored by the authorities, and when something unexpected arose that might cause problems for the government, it took days for news to spread throughout the entire country, as the (fixed) telephone system was underdeveloped.Footnote 100 The National Conference gave many Nigeriens the chance to learn about things in real time for the first time in the country's history. The extraordinary return of a former adviser to Kountché who had left to take refuge in Belgium after an attempted coup d’état aroused especially keen interest, to the point where audiocassettes of his declarations would be sold in the country's markets the following year.Footnote 101 Across the whole country, revelations about the past and decisions to be taken on the future were the subjects of informal discussions. It was in this context that “fada”, or informal meeting groups of young people, developed. The word refers more to a subordinate position than to a certain age range – where everyday events and politics were discussed over tea.Footnote 102

The anticipated decisions included both the implementation of democracy and the direction to be taken by economic policies, as rejection of the structural adjustment had played a significant role in the fall of the military regime. At the conference, the SAP went through numerous interventions, beginning with Ali Sabou's opening address, in which he justified its adoption even before declaring the meeting open.Footnote 103 Conversely, every – or nearly every – party rejected it in its general policy statement, in particular the Parti Nigérien pour la Démocratie et le Socialisme (PNDS), the party that would win the legislative election a year later, which submitted “the unsuitability of the economic model proposed by the Bretton Woods institutions” as evidence.Footnote 104 The statement by Amadou Cissé, a World Bank official speaking in the name of the international organizations, was one of the only ones to be heckled, if we are to believe the messages from the rapporteurs, who took note of everything that happened in the hall in the same way as they did with discussions in the National Assembly.Footnote 105 One whole day, 2 October 1991, was dedicated entirely to the adjustment. The rapporteur-general introduced discussions by stating that “the plenary assembly has not provided sufficient concrete alternative measures to the structural adjustment, whereas the public finance deficit is estimated to be 100 billion CFA francs”.Footnote 106 The participants who took turns at the podium advocated counting on the country's own resources, including taxing the informal sector, renegotiating uranium prices, recovering debts incurred by domestic companies with the state, and, above all, recovering funds diverted by senior members of the military regime. At the end of the day, the Chair of the Economic Committee reached the following conclusion:

the structural adjustment in its current form is rejected by a majority, and the discussions have only confirmed this. Together with the structural adjustment, lowering of the wage bill, privatization of domestic companies and staff reductions are also rejected.Footnote 107

The National Conference ended on 3 November 1991. In his closing speech, the new Prime Minister, who was elected by the delegates to lead a transition government until the elections, stated that the conference had “achieved […] cardinal reforms that will make Niger a country that has signed an unlimited lease with democracy”.Footnote 108 One might find these words ludicrous today, in a country that saw three military coups d’état and a constitutional coup in the twenty following years. However, apart from the fact that other futures might have been possible, one might also view the Nigerien National Conference as the culmination of social struggles that could never have been predicted to be possible a few years earlier. This moment needs to be interpreted in relation to its past, not only to what came after. As the Nigerien political scientist Malam Souley Adji remarked when suggesting that we look at how this event was perceived at the time it unfolded: “The important thing is that it happened, because [that it would happen] was not at all evident. The fact that things didn't work later is a different story.”Footnote 109

TINA in Niger

A public debt can be measured, but how is it possible to measure the cost of popular disaffection with a regime that emerged out of social movements? On the one hand, there are the cold, hard facts of budget statistics that clearly show what needs to be done, while on the other there are things that cannot easily be quantified, such as political feelings and social violence. By putting into effect a liberalization policy similar to the one that had been put in place at the end of the military regime, the government that emerged from the National Conference did what budgetary rationality, with the support of international financial institutions, instructed it to do. But it also dismissed the exercise of power by people whose roles had been decisive in the democratization process, and who expected something quite different from it. If one looks at the forces at work, one might say retrospectively that there was no alternative to this political decision (the famous TINA),Footnote 110 if one clearly understand it as the outcome of a power relationship: after the fall of the military regime, several different rationalities that opened up to a number of possible ones stood in opposition to each other in Nigerien society.

In the wake of the National Conference, the transition government enjoyed the benefit of a social truce with the trade unions, but not a financial truce with its funders. Barely a month after the conference had ended, the IMF decided to suspend its support for the country, taking the view that it had breached the structural adjustment agreements entered into with the previous government. This led to reprisals from a number of financial partners: the cost of debt service, which represented over half the state's tax revenues, suddenly increased by twenty per cent, and in 1992, the Nigerien government had to repay 11 billion CFA francs that had not been budgeted for at the beginning of the year. More fundamentally, Niger found itself “almost entirely cut off from the various [forms of] budgetary aid that had previously enabled it to attend to its most urgent matters”, in the words of a study carried out for the OECD.Footnote 111 The consolidation of public accounts was the first task the Nigerien authorities set themselves. The resources the National Conference had counted on to carry out this consolidation turned out to be far smaller than it had initially hoped, however. Renegotiation of uranium prices with foreign companies was a failure, and prices continued to fall.Footnote 112 The approach taken to recover the funds diverted by former dignitaries, which had raised so many expectations, did not have the expected returns.Footnote 113 The only significant windfall came from international aid. The Nigerien government's recognition of Taiwan – which is still recalled today by the evocative phrase “Taiwan or chaos” – had an immediate impact, although it did not offset the reduction caused by the break with international financial institutions.Footnote 114

At the outset, the regime was supported by the principal social forces involved in the National Conference, as witnessed by the reactions to a military uprising in February 1992. Troops took over the national radio and the airport, arresting four ministers and the President of the High Council of the Republic to demand that one of their own be freed and that their back wages be paid.Footnote 115 In response, the USTN organized a “dead city” day – that is, a total halt to all business activities – in Niamey. The same evening, a crowd of thousands of people, including workers and students, in support of the new regime gathered in Place de la Concertation, where they stood up to the soldiers, who fired into the air to disperse the crowd.Footnote 116 When the night ended, the mutineers freed their prisoners and returned to their barracks. According to the government newspaper, the mutiny “made it possible to revitalize the spirit of the National Conference: […] popular meetings organized throughout the country, a two-day strike and dead city operations allowed the democratic forces (associations, political parties and trade unions) first to save, and then even possibly to take back control of, the democratic process”.Footnote 117

In fact, however, the “spirit of the National Conference” was already long gone, and democratization was proceeding in a context of growing tensions associated with the government's budgetary policy. While a new Constitution was submitted in 1992 for a referendum, there was a growing number of strikes and demonstrations to protest against unpaid salaries in the civil service. The threat that examinations in the education sector would be invalidated, which was brandished by the government at the end of the year to stop the strikes, led to an escalation of the protests. In January 1993, thousands of demonstrators, including students, parents, and teachers, gathered in Place de la Concertation to proclaim their rejection of the “white year”. Government and police vehicles were damaged and the courtyard of the presidential palace was invaded by demonstrators, who forced the main door open, leading the police to intervene with truncheons and tear gas.Footnote 118 It was one month before the presidential election and the general election between the Mouvement National pour la Société de Développement (MNSD), which had emerged out of the former military regime, and the main parties of the National Conference, which had joined together in the Alliance des Forces pour le Changement (AFC), whose principal political slogan was “Canji!” (“change” in Haoussa). The adjustment hung over the campaign, even as the Nigerien state was under pressure from international financial institutions. Just before the elections, “guidelines”, including a salary freeze and another reduction in public spending in particular, were “made known to the transition government by the IMF”.Footnote 119 Without advising people how to vote, the USN warned voters against any step backwards in this tract:

Niger is preparing for the first presidential elections in its history. […] Our country is embarking on a decisive phase towards pluralist democratization. […] For the USN, the MNSD [would represent] a backward step for our country. For the USN, the return of the MNSD means the SAP, catastrophe. […] It would be the first sign of a return to the old order.Footnote 120

What made this tract special is that it was undoubtedly one of the last political leaflets in which it was still possible to associate the adjustment with the “old order” of the military regime. The AFC defeated the MNSD in the elections, and the new government took office in April under the leadership of Mahamadou Issoufou. A month later, he announced budget economy measures, while also indicating his willingness to reach an agreement with the World Bank and the IMF. Civil service salaries were frozen, even though several civil service bodies were already facing significant arrears. The retirement age was reduced, which was viewed as social regression in Niger. The high school and university academic years were also declared “white”, because teachers had been on strike for too many days.Footnote 121

These decisions, which were taken by the first democratic government in the country's history immediately after its election, consummated the break with the social forces that had led the struggle against the military regime. It also led to a radicalization of protest methods. In May, university and high-school students, members of the USN, attacked the headquarters of the political parties making up the AFC, destroying all of them except one, which was protected by militants armed with batons, and bows and arrows.Footnote 122 In June, the energy sector trade unions began an indefinite strike after a World Bank manager announced that it was “unfortunately obliged to suspend disbursements in the electricity sector” in order to defend the “rationale of the adjustment”. “This depends above all on the Nigeriens”, the manager explained in the Nigerien press.Footnote 123 In July, there was another military uprising in Zinder, the country's second largest city, where the Prime Minister was paying a visit. Soldiers tried to arrest him in order to have their back wages paid and to obtain better treatment. As a reaction, a meeting was organized in Place de la Concertation to “save democracy”, but this time it only involved the AFC parties: the trade unions had given up the fight.Footnote 124

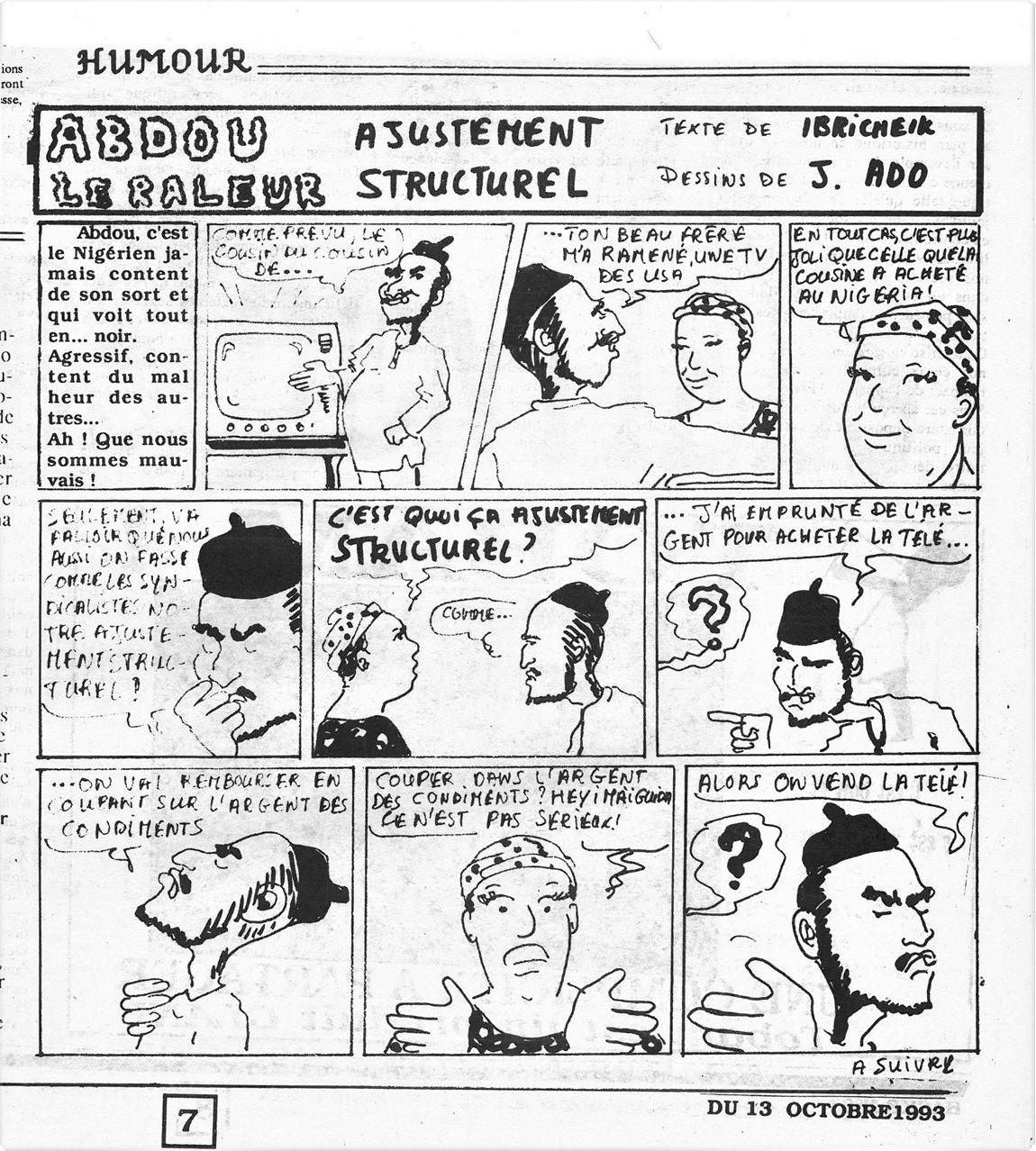

In fact, it was the government's economic policy rather than the democratic institutions that now became the central issue for social struggles. These struggles indirectly opposed the protagonists of unequal forces. On the one hand, the trade unions battled against the liberalization policies imposed by international financial institutions, while their field of action was being limited by their own government. In September, a law authorized “the collective or individual requisitioning of civil servants in the event of strikes triggered in a vital strategic sector”. Unionists were now “obliged not to undertake anything that might frustrate the provision of a minimum level of service”.Footnote 125 This law also restricted the purpose of strikes to professional interests, which led the government newspaper to proclaim that “every strike of a political nature is illegal”.Footnote 126 On the other hand, the international institutions and Niger's principal funders multiplied their injunctions to pursue economic orthodoxy. In October, the French Minister of Finance demanded the “return of all African countries into the international financial community”, announcing that “not even one cent will be paid to countries that have not made the necessary effort to obtain the signature of an agreement with the Bretton Woods institutions”.Footnote 127 At the heart of this long-distance struggle was the SAP, which was now a frequent presence in daily discussions far beyond militant circles.Footnote 128 Cartoons on the adjustment became more frequent in the newspapers, like the one in which a man explains that he is going to have to choose between the television and condiments (see Figure 3): the SAP itself had become a subject of public debate, and even more, one of the favoured prisms through which to understand the country's political development.

Figure 3. Structural adjustment through a press cartoon in 1993. Cartoon published in Haské on 13 October 1993.

There are different ways to describe these few years in Nigerien history. One is to explain that the initial objective of the transition government to count on domestic financial resources alone was profoundly absurd, given the country's debt ratio and its dependence on outside aid. The other is to take the view that the Nigerien government could not commit itself to a policy the questioning of which had played a fundamental role in its accession to power – and also in the production of political legitimacy – without cutting itself off from the social bases that had striven the most for democratization and still remained indispensable to the functioning of an under-administered state.Footnote 129 Whatever the version may be, what emerges on both sides is an impression of a conflict of rationales – or absurdities, depending on the point of view one chooses – that cross through the political struggles during those times.

From devaluation to demobilization

In the end, it was the IMF that won. In 1994, Niger returned to a new round of negotiations with international financial institutions that ended with the signature of a “confirmation agreement” in March, just after the CFA franc had been devalued two months earlier.Footnote 130 This return cannot be the only explanation for the military coup d’état in 1996. However, it had a lasting effect on the devaluation of the democratic ideal, while also coinciding with extensive political demobilization, which, as has been shown in other contexts, also obeys a form of rationality.Footnote 131

The decision to devalue the CFA franc, which was made official by the West African Heads of State in Abidjan on 11 January 1994 in the presence of the French Minister of Cooperation and the Managing Director of the IMF, caught the Nigerien population completely unawares. There had been no debate in Niger on this measure, which had a powerful effect on daily lives, even though the country had just had its first free elections. Even the very idea of a devaluation had only appeared in the Nigerien press a few weeks earlier, and only a few people understood the meaning of the word in the streets of Niamey.Footnote 132 The Nigerien historian Boureima Alpha Gado, who had been a delegate at the National Conference, wrote a column in Haské with the evocative title “It's democracy that's being devalued”.Footnote 133 The measure immediately resulted in a considerable increase in the prices of consumer products, despite government decrees that allegedly froze prices, and in a lack of cash and food, as retailers suspended transactions while they waited for prices to go up even more.Footnote 134 The shock affected everyone's spirit: devaluation is one of those events that do not occur very frequent in one's lifetime, but everyone remembers where they were when they found out about it. This is what one resident of Niamey, who was ten years old at the time, had to say about it:

I was small, I remember, we were sent to the mill [to grind millet]. […] When we arrived, the guy said: “Ah, there's devaluation now, and prices have doubled”. We didn't understand any of this […]. We said: “OK, here's what we've been given”. [He thinks] It should have been 25 francs, because I had a hundred francs for four tias to be ground. The guy said: “The prices have doubled. I'm not going to do it like that”. At this point, an old man heard us. He listened calmly and didn't say anything. And when he saw the guy insisting, he came over and said: “Ah, it's because they are young that you're cheating them. The devaluation doesn't affect you at all. Because up to now, the diesel you're paying for hasn't changed. So it doesn't affect you. You need to grind it like that”. [He laughs]. The guy was ashamed, and he did it like that. He paid the price I wanted. That's really what I remember.Footnote 135

In addition to the many tensions in everyday interactions, devaluation coincided with an increase in violence during mobilizations. Just before it was made official, small groups of pupils and students armed with rocks and Molotov cocktails stoned government buildings and burned vehicles belonging to international organizations.Footnote 136 The protests went on for several months before they were brutally put down by the police. On 10 March 1994, the police went on to the university campus, where students were preparing a demonstration. One student, Harouna Tahirou, was killed when a tear gas grenade was fired straight at his head.Footnote 137 This drew a strong reaction at the university and in the rest of the city. Some of the students who had been recruited by the PNDS at the time of the National Conference burned their cards in public.Footnote 138 Others delivered an ultimatum demanding the resignation of the Mayor of Niamey. An open letter was written for the attention of “Monsieur le criminel” to denounce his responsibility for Tahirou's death, as well as the fate reserved for the political forces that had worked the hardest for the democratization process: “You say we worked together for change. No: WE worked for change, but you, you are just an opportunist who came from nothing, who kills our militants as a way of thanking us.”Footnote 139 This death, which occurred just three years after 9 February massacre, had a lasting effect on the students in view of its similarity to the excesses of the military regime. A portrait of Tahirou (see Figure 4) still hangs in front of the UENUN offices today.

Figure 4. Portrait of Tahirou hanging in front of the UENUN offices. Photo: author.

In contrast to what had happened three years earlier, however, Tahirou's death did not lead to a rally of dissatisfied people or create the potential conditions for a political crisis.Footnote 140 In the months that followed, the workers’ unions increased the number of demonstrations demanding wage increases that would make it possible to face the price increases, before beginning an “indefinite strike” on 1 June 1994. The strike lasted fifty-five days, the longest the country had ever seen, but it ended in failure.Footnote 141 The students clearly leaned towards demobilization too, even though it was the worst year they had seen since the beginning of the decade in terms of the deterioration in living conditions and physical repression of protesters. A final general meeting was organized in July 1994 on the Niamey campus, just before the end of the university year. According to the handwritten notes taken by the secretary of the meeting, there was a very lively debate on the tactics to be adopted:

The differences emerged in broad daylight when the question was asked about the method to be adopted for the struggle. Some believe that blocking the bridge on the road leading to the campus was a measure of no consequence, because those who would suffer the most would be the people whose support we needed, and not the government. This is why they decided that the best method would be to organize a march and a sit-in at the Prime Minister's office. If the police intervened, we should withdraw and block the bridge. […] This demobilization is […] a real handicap for the movement. […] In the face of this paradox between growing misery and the demobilization, or even the resignation of the base, there was a tendency towards resignation. […] In any event, it would be perilous to continue with the movement with a number of comrades that borders on the shameful and the ridiculous. This is even more justified in the case of arrests, when all our comrades risk being left to their own destiny.Footnote 142

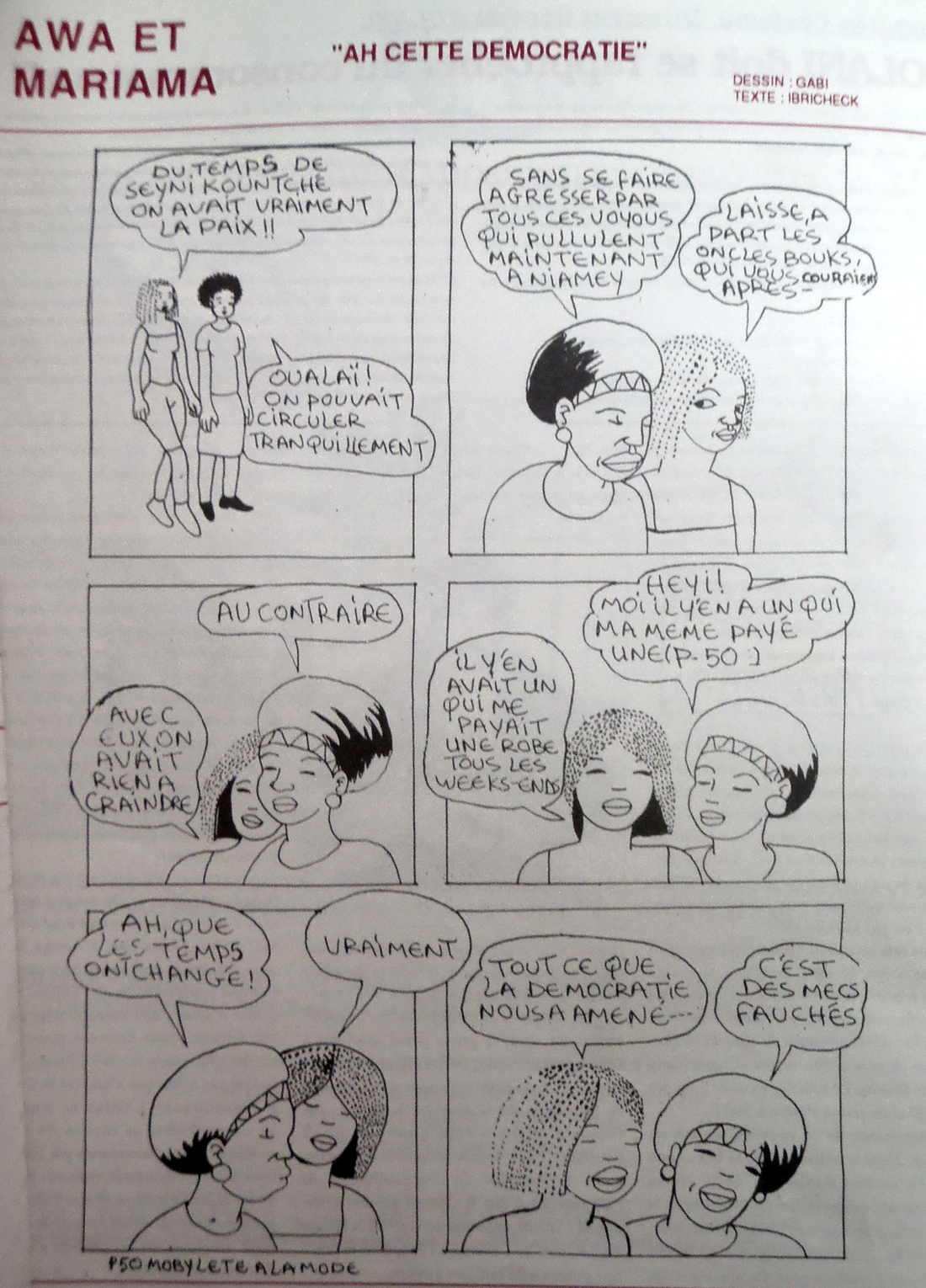

Most of the people who attended this general meeting had experienced the victorious mobilizations that had led to the fall of the military regime a few years earlier and the effervescent spirit of the National Conference. Some years later, the era of the possible had ended; it was a time of disillusionment, including among the social groups who had initially been the main drivers of the democratization process. This was symbolized in 1995 by a cartoon that appeared in Haské (see Figure 5), which is emblematic of the opening up to pluralism. It shows two women reminiscing, “in Kountché's time, [they had] real peace”, before saying “all democracy has brought us is broke guys”.Footnote 143

Figure 5. Democracy through a press cartoon in 1995. Cartoon published in Haské magazine, special edition no. 2, 1995.

On 27 January 1996, Colonel Ibrahim Maïnassara Baré, the Chief of Staff, seized power in a coup d’état.Footnote 144 The National Assembly was dissolved, political parties were suspended and a state of emergency was proclaimed. This coup undoubtedly did not represent the inevitable culmination of this story; other outcomes had been possible. It also took place within a shorter timeline marked by the exacerbation of partisan struggles in 1995, which led to the regime's institutions being blocked.Footnote 145 It was not a return to the past in the strict sense of the word, as if nothing had happened in the past five years, and the new head of state was quick to give a democratic form to his seizure of power by promising early elections. On the other hand, it marked an evaporation of the political aspirations that had developed at the beginning of the decade: in Niamey, no one took to the streets to defend the government under attack, unlike in February 1992 and July 1993. By contrast, the international financial institutions energetically condemned the coup d’état. The day after, Boukary Adji, who had been responsible for implementing the first SAP under Kountché, was named Prime Minister.Footnote 146 He would be succeeded by Amadou Cissé, soon after the latter had led a mission to the World Bank to finalize the implementation of the second SAP,Footnote 147 which was ready to be signed.

CONCLUSION: RATIONALITY AND ABSURDITY IN POLITICS

A number of questions arise on the conclusion of this story that go beyond the case of Niger alone.

The first regards what populations revolt against, and what drives us as researchers to define it, what these populations explicitly define and what implicitly leads them to act. If we look at the meanings protestors attach to their actions, it is not truly possible to qualify the acts of revolt discussed in this article as “IMF riots”, unlike in other countries at the time.Footnote 148 Even though the SAPs gradually revealed themselves to be a cause of the anger in Nigerien society, everybody saw their existence much more through concrete realities than through the prism of an ideological struggle against external forces. All along, it was “the state” rather than “international organizations” or “liberalism” that was the preferred target of popular anger, and in this respect it appears to be fairly nation-centric and state-focused, as was the case with other movements I have studied in West Africa.Footnote 149 However, this does not mean that the adjustment did not work as a backdrop to this anger even more than I had imagined before I began this research. In this respect, it is undoubtedly an important part of the social history of other African revolts, one that it is important to investigate further.

The second question touches on the political economy of democracy as it has affirmed itself in Africa in the past forty years or so. In a good number of African countries, the political liberalization of the 1990s went hand-in-hand with economic liberalization. There was nothing obvious about this convergence: it was even quite paradoxical for the time, including economically, if one considers the increasingly powerful voices that made democratization an important condition for development.Footnote 150 As it happens, liberalization weakened the nascent democracies, and if these voices are to be believed, it had an adverse effect on the economy. The most important thing, however, is that liberal reforms had already been under way before the political regimes became democratic in many parts of the continent, and even played an important role in the protests against the authoritarian regimes, as in Niger. In other words, when the years of democratization are today commonly devalued on the streets of Niamey, Bamako, and Ouagadougou as having led to a privatization of the state, a loss of the old rules, and a deterioration in living conditions, it is doubly unjust: on the one hand the transformations people blame were already under way, and on the other there was nothing a priori that made it inexorable for the new regimes that were born out of the social revolts to pursue them.

The third question, which is more controversial and more subjective, concerns the rationale used by the international financial institutions. It is admitted that “things are more complicated than people may believe” and that there is no reason to question the morality of events in a scientific article. Notwithstanding this, when I returned to this moment in Niger's history and decided to look at the sequence of events in depth from the perspective of the sociology of the events, I was surprised to discover the extent to which this story, although it had a clear rationale from an accounting perspective, also simultaneously harboured elements that might legitimately seem absurd if one adopts the point of view of the rebels and their aspirations for democracy. I was also surprised to discover how closely the most violent moments of repression by the Nigerien state during this period were connected with the chronology of the adjustments, to the point where it is hard not to think that the international financial institutions co-produced the conditions that made this violence possible, even though it was not their intention to do so. Finally, I was surprised that today, these somewhat strange actions – increasing the burden of debt just after democratic institutions had been installed, forcing devaluation the day after unprecedented free elections – do not seem to be more absurd, not only from the standpoint of the material consequences, but also through the prism of the deep traces they left in political imaginaries and the practical impact this could have. Considering that conflicts of rationales such as this are always possible, it seems to me to be important to reflect on it.