The Questions

Antinatalism is an emerging philosophy and I am an antinatalist philosopher—or, at least, I think I am.Footnote 1 Being antinatalist means, to me, that I do not have children, I do not intend to have children, and I would be pleased if everyone acted like me in this respect. Being a philosopher means, to me, that I must understand the isms that I foster. The philosopher in me demands me to define what my antinatalism means. A major part of this understanding, and definition, is to explicate why, how, and to what degree I would be pleased if everyone acted like me.

I would be pleased to see no one to have children, because that would be a rational thing to do. Reproduction carries risks to the possible future individuals. All lives are occasionally miserable, some lives are predominantly miserable, and individuals may think, justifiably, that their lives have no meaning.Footnote 2 , Footnote 3 , Footnote 4 , Footnote 5 , Footnote 6 , Footnote 7 , Footnote 8 My reason suggests that it would be unwise and unkind to bring new people into existence and thereby expose them to these risks. Arthur Schopenhauer agreed with me, many others have disagreed.Footnote 9 , Footnote 10

Better-known antinatalist philosophers like Julio Cabrera,Footnote 11 , Footnote 12 David Benatar,Footnote 13 , Footnote 14 Karim Akerma,Footnote 15 , Footnote 16 and Théophile de GiraudFootnote 17 have explicated in detail these and related arguments against having children; while self-confessed proponents of cautious pronatalism Rivka Weinberg and David Wasserman, as well as (allegedly) neutral commentators, have identified flaws in them.Footnote 18 , Footnote 19 Seana Shiffrin has added to the mix the remark that future individuals cannot give their consent to being born.Footnote 20

I have presented interpretations and analyses of these views and arguments elsewhere and will not return to them here. Instead, I will concentrate on one feature of antinatalism that can be seen either as its cornerstone or its stumbling block. It is that if no one has children, humankind will inevitably go extinct. Can this be accepted? If it can, what practices would antinatalism promote? If it cannot, what are the alternatives within the creed?Footnote 21

Attitudes to Extinction

Let me begin by mapping, in Figure 1, some interpretations of antinatalism according to their attitudes toward extinction, axiology, and life’s continuation in some nonstandard form. The catalogue is not complete and significant variants of the creed may be missing, but this partial classification enables me to clarify my own thinking on the matter.Footnote 22

Figure 1. Forms of antinatalism.

The main dividing line in Figure 1 is between views that reject or accept the possibility of extinction. If it is accepted, a further question is, for humankind only or also for other species? In answering the second question, the choice of axiology, or theory of value, is a prominent factor. If it is sentiocentric, in other words, if the prevention, removal, and mitigation of suffering are seen as the only intrinsic values, then all sentient life should be ended. If it is anthropocentric or biocentric, that is, draws a distinction between human and nonhuman beings in some respect or values all life alike, only people may be included. On the nonextinctionist side, further divisions concern the future of bioreproduction, bioimmortality, and virtual human continuity. I will get to these differences and their implications momentarily.

Self-reflection reveals that I occupy three different spaces on the map. First, I am a voluntary human extinctionist. Secondly, I think that factory farming and animal production should be stopped. Thirdly, I believe that virtual human continuity without sentience could, with strict specifications, be acceptable. I know from experience that I can build a theoretical framework to support this combination but I also know that it is not conceptually elegant, let alone watertight. It is a patchwork and, as such, qualifies as the winning approach only if more solid alternatives are not available. Let me see how the other views in the classification fare first and only then return to the pros and cons of my own reading.

Conditional Nonextinctionist Antinatalism

Beginning from the generally most palatable view on offer, some believe that reproduction should be restricted but that it does not need to be banned altogether. Maybe we should not have children now; but in the future, when times are not as bad, it could be allowed. Or maybe we should not have children; but some others, who can take care of them more adequately, could. In this model, humankind is not threatened by extinction, on the contrary. Perhaps fewer people could live better lives on a planet of limited natural resources. The view can be called conditional nonextinctionist antinatalism.Footnote 23

The inclusion of this view in the family of antinatalisms requires some conceptual maneuvering. According to a very permissive interpretation, pronatalism states that we have a right, and possibly a duty, to have children; while antinatalism states that we have a right, and possibly a duty, not to have children. Within these definitions, the competing isms share common ground in the “right” area, governed by the principle of reproductive autonomy. People are entitled to their own choices in childbearing.Footnote 24

Since “antinatalism” and related words have not been accepted to major English dictionaries, there is no official way to challenge such loose usages of the terminology. In fact, the most authoritative French source, Larousse, defines “antinatalist” as “Qui vise à réduire la natalité”— who or which aims to reduce natality.Footnote 25 This neutral definition could make antinatalism compatible with reproductive autonomy as a policy in modern societies. Freedom of choice can, depending on other cultural and political trends, reduce natality in the global north.

Yet most other sources agree that some kind of a distinctly negative verdict is also needed. Antinatalism as a philosophy, according to popular understanding, does not only discourage childbearing but also claims that it is morally wrong.Footnote 26 Conditional antinatalists can, in the face of this, say that while some instances of childbearing are immoral, others are not, depending on the expected quality of life of the future individuals. We are allowed to have children, they can argue, if or when we can guarantee their freedom, happiness, and well-being, although otherwise it would be wrong.

This is not the time or the place to settle the underlying terminological disputes. I would suggest, however, that “selective pronatalism” might be a better epithet to the view described as conditional antinatalism just now. It does, after all, encourage further—albeit fewer—births. This conceptual move would make it clearer that eugenic and otherwise discriminatory population policies are pro- rather than antinatalist.Footnote 27

Having said that, I must repeat that my aim here is not to act as a word police. The advantage of conditional antinatalism or selective pronatalism is that it is a logical—and the only realistic—choice for those who want to avoid human extinction but, at the same time, reduce birth rates, in line with the French dictionary definition.

Antinatalism with Biological Immortality

Moving on to less realistic, at the moment science-fiction, solutions, the next port of call is antinatalism with biological immortality. We could decide not to have children but develop technologies that would help us to live forever.Footnote 28 In theory, this would avoid the immediate threat of extinction while not creating new suffering-prone lives. In practice, the best we can achieve is probably considerable longevity, more-than-a-thousand-year lifespans, but it would at least postpone the demise of the species. Stalling ageing and making massive progress in curing diseases, we could make accidents and violence our only causes of death, and even those might be reduced by preemptive policies.Footnote 29

The antinatalism of this view is not in question, analytically speaking. It is compatible with the conviction that childbearing is always wrong. And it does not commit its champions to the claim, unpalatable to so many, that human extinction is our moral duty.Footnote 30 , Footnote 31 There are interpretations of antinatalism that would reject attempts at immortality on axiological grounds, but I will come to those later. Off the top of my head, the only objection to this approach is that it might coerce people to drag on their meaningless existence. But that objection can be averted by a further specification.

Human bioimmortality can be combined with a right-to-die clause. If it is, and if the projected immortals would be entitled to end their lives at will, maybe with proper medical assistance, my concern would evaporate. People who want to live for as long as technology allows could do so while the ones who get bored or are hit by existential anxiety could exit voluntarily whenever they wish. The arrangement would call for changes in attitudes,Footnote 32 but we are talking about a science-fiction scenario here already, so maybe that could be imagined.

If human bioimmortality is not combined with a right-to-die clause, things are different. By exposing the population to longevity, possibly making it a norm not to be deviated from, and denying a decent exit route, we would convict people to a futile existence, violate their self-determination, and inflict suffering on them. This is not a form of nonextinctionist antinatalism that I would find attractive.

From Biological to Physical Immortality

Biological immortality as such can be a forlorn dream, as the physical world we live in is not eternal, but prolonging human lives considerably has been firmly on the scientific agenda for decades. The SENS Research Foundation, for one, claims that different methods of curing and preventing diseases and cleansing and replacing cells and body parts will gradually move humankind closer to longevity.Footnote 33 , Footnote 34 The realism of the Foundation’s promises is a side issue in my current narrative, as the only question from the viewpoint of antinatalism is, will new people be born? As long as we stay in our own bodies during the longevity treatments, this does not seem to be the case. Already existing individuals go on living but new ones are not created. All is well.

One definitely science-fiction solution must be brought up at this point, because it can be interpreted as producing new humans. The method is destructive teleportation, brought into general attention by the Star Trek saga of movies and television series. Starship crew members and others are caught in a transmitter beam, they evaporate, and they reappear somewhere else looking exactly the same. What happens during the transition is not entirely clear from the viewpoint of science, but a rough description is possible. The travelers are scanned, their blueprint and possibly the material they consist of is sent to the desired destination, and a new copy of them is produced in the new place, either out of atoms and physical parts also transmitted or out of local materials.

A further feature of the process is that it can include corrections and amendments. In the Star Trek adventures, viruses and other undesired elements have at times been filtered out of the end result. This could, in principle, provide a route to considerable longevity. When we are injured or develop illnesses, teleportation could sieve and remove imperfections and a better individual could continue the life of the damaged one.

This method, called destructive teleportation because the original is dismantled and possibly discarded in the process, raises questions of identity that are relevant to the feasibility of nonextinctionist antinatalism. If the result of the transmission is an individual made of completely new molecules and components, both the physical and mental continuity of what was destroyed is compromised. The original human being disappears and someone else is created instead. The situation could be slightly better with the materials sent and rebuilt into a copy of the dismantled individual. The scientific and technological side of the process, however, would then be even more mind-boggling.

The point here is that the alleged immortality achieved by corrective, destructive teleportation may well be a mere front for creating new humans. If antinatalism is about not exposing possible future individuals to the risks of manipulation and suffering, teleportation is not compatible with the aim. Letting oneself die in the process does not necessarily produce problems but letting the new being emerge can easily be counted as posthumous procreation. That, from the viewpoint of antinatalism, is most probably unacceptable, unless some kind of a complicated conditional view is assumed.

Virtual Human Continuity

Another way to avoid extinction yet remain childless is offered by virtual reality. We are already connected to all manner of smart gadgets and new ones enter the market every day. If this trend continues, we could, sooner or later, depart our biological existence altogether and become voluntary parts of a virtual world, or so some like to think.

Science enthusiasts talk about mind uploading lightly, perhaps thinking of a game world that we can immerse in temporarily. The real thing, I suspect, would be different from anything that we can currently comprehend. We have no scientific understanding of what it would be or feel like. But I may be looking at the wrong direction. Perhaps the lackadaisical approach stems from our more deeply rooted unscientific, possibly religious or philosophical beliefs.Footnote 35

Bodily resurrection is a doctrine so familiar to many of us that it does not raise any eyebrows, although it arguably should. When our bodies die, our souls remain alive, maybe asleep, maybe in purgatory, until the two are joined again to live eternally and blissfully in heaven. Science enthusiasts could see mind uploading as an analogous process. We leave our material bodies, get organized into digital, immaterial form, and then enter computer paradise and live happily ever after.

Rebirth presents a similar analogy. The soul of a living being survives biological death and migrates into a new body of the same or of another species. This allows the life to be quite different from the original, as in the case of mind uploading. Whether we can genuinely understand what it would mean to be reborn as a bat is another matter. And rebirth is, for good reason I believe, depicted as a curse rather than a blessing. This could, in fact, be a warning story against the dream of virtual existence.

Philosophically, the primacy of the immaterial aspect of our being is a recurring theme in the European tradition at least since Plato. According to him, only souls can live in the superior reality of perfect ideas. Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas echoed the idea in the Christian teaching and Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd in the Islamic tradition. The semisecularization of the soul by René Descartes perpetuated the mind–body dualism that is still tangible in many brands of Western thinking. After Descartes, subjective idealists like George Berkeley dropped out the body altogether.

From the viewpoint of antinatalism, the question to be answered is, would mind uploading preserve personal identity or would it create a new individual? Due to the uncertainty of what the end product would be, I believe we have reasonable grounds to think that the emerging entity would be a novel, different human or posthuman being. Like in the case of destructive teleportation, the material foundation would be different and there would be a marked discontinuity in the immaterial dimension, as well. Mind uploading would, then, kill us and produce a life of its own, resembling us in some respects but not identical to us.Footnote 36

If this is a fair assessment, mind uploading would not be the model of immortality-without-procreation that could support nonextinctionist antinatalism. Depending on our axiological choices, however, a thin chance of rescuing the position remains. If we could guarantee that our virtual existence would be nonsentient, or that it would contain no suffering, proponents of convenient theories of value could be appeased. But this is highly improbable and I would not count on it. And I am getting ahead of myself. More on the axiologies as the narrative progresses to the other side of Figure 1. First, however, a summary of my findings so far and a note on some further distinctions that could be useful.

Nonextinctionist Views Assessed Against My Initial Criteria

To repeat my own initial position, I would be pleased if no one had children—or, more generally, if no new individuals were brought into existence. It should come as no surprise, then, that I do not particularly like the thought of conditional or modified antinatalism in any of its guises. There are two or three almost-qualifying candidates but, on the whole, I would not endorse any of the suggested solutions.

The idea of producing only happy people from here on is not only patently unrealistic but also, as I have said, a potential source of injustice. In addition to the risk of suffering in any life, arrangements that allow some but not all to reproduce are seen as discriminatory. And I believe that selective pronatalism would be a better name for a policy that encourages childbearing and merits to be called antinatalist only in the weak French dictionary sense.

Bioimmortality with a right-to-die clause would be genuinely antinatalist and respect people’s autonomy at the same time. Its challenge is that human beings are not immortal, not really. The SENS Research Foundation may be able to prolong some lives considerably, to a thousand years and beyond. But no one lives forever, not in this world. That is why so many religions thrive by teaching the immortality of the soul after the death of the body. Biological longevity would not prevent the eventual extinction of humankind.

Destructive teleportation is comparable to the only-happy-people model both in being unrealistic and in allowing the production of new individuals. The procedure is suggested by science fiction, so its distance from reality is a given. To understand its reproductive nature, we only need to see that in the process, as described, the person “transmitted” dies and a new person is born. Birth rates are reduced but sentient and conscious lives are still brought into existence. And the challenge of human extinction is present also in this scenario. Individuals—as types rather than tokens—remain in existence for as long as they stay alive or at least their blueprint remains safely in store. But when people die and the blueprint goes missing, they will meet their end.

Virtual human reality, insofar as we can grasp the idea in the first place, falls into the same trap as destructive teleportation. The entity that appears in the new artificial environment is not identical to us, instead, it is its own being, and that goes against the requirement of not creating novel individuals. I cannot see how we could guarantee a life free of suffering for those individuals, so the risk argument prohibits bringing them into being. Virtual lives could, with a stretch of imagination, be nonsentient but in that case what would the motivation of producing them be?Footnote 37

One more feature of all forms of conditional and modified antinatalism deserves to be recorded. It is that while they all shun human extinction, none of them is particularly committed even to the French dictionary’s weak notion of reducing birthrates. Once the present or future population is healthy, happy, and long-lived, conditional and modified views seem to imply, we can reassess the situation and open up the reproductive floodgates again. This, from the viewpoint of antinatalism, is confusing.

Some Further Distinctions

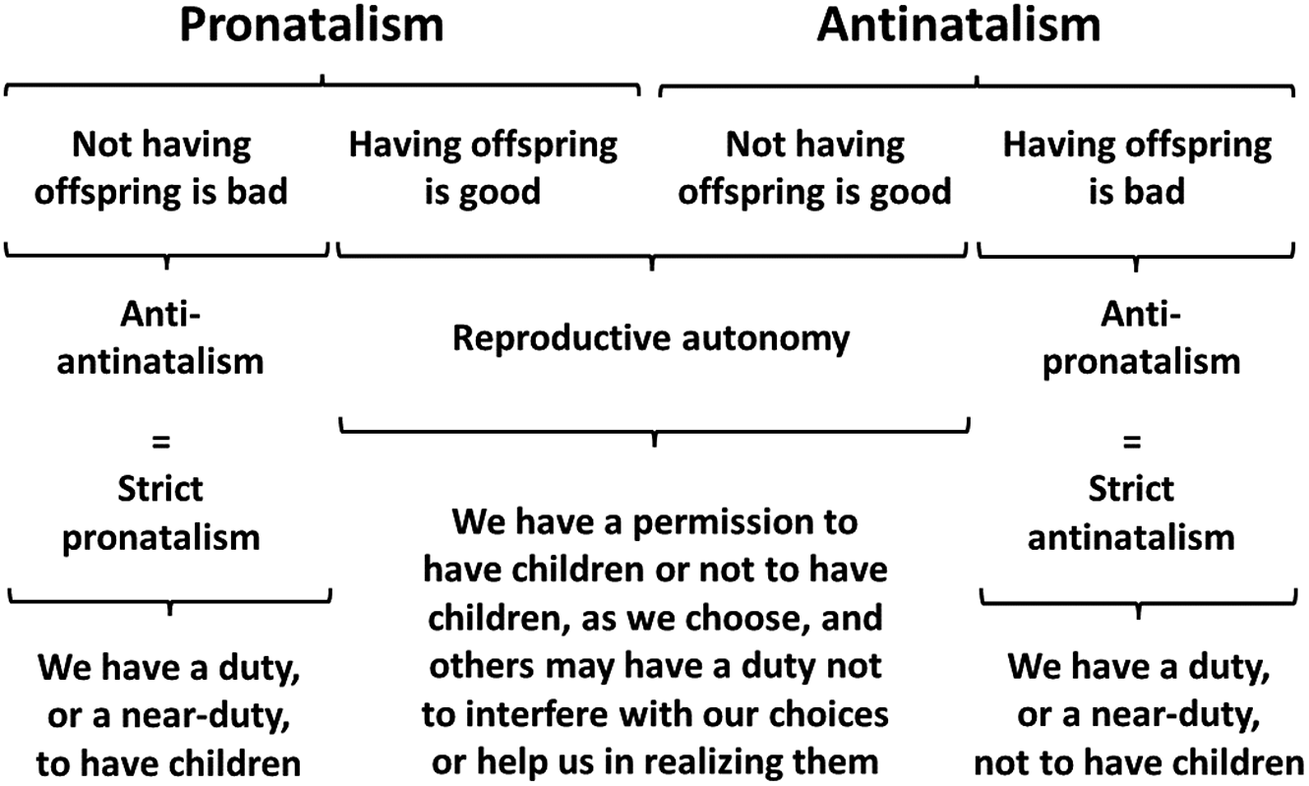

Another way of classifying the isms involved, already mentioned briefly, could clarify the situation. In the shared conceptual space of reproductive autonomy, pronatalists believe that having offspring is good while antinatalists believe that not having offspring is good. This does not need to be much more than a difference of opinion or choice of a lifestyle, Deeper disagreement is, however, also possible, when the parties consider each other’s views and decisions. Pronatalists can claim that not having offspring is bad and antinatalists that, on the contrary, having it is bad. The options are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Shades of pro- and antinatalism.

According to Figure 2, then, there is a division not only between pro- and antinatalism but also between stricter and more lenient versions of both creeds. Strict pronatalists, who could also be called anti-antinatalists, can hold that we have a duty, or a near-duty, to have children. Strict antinatalists, or anti-pronatalists, can maintain that we have a duty, or a near-duty, not to have children.Footnote 38 In the middle ground, less ardent pro- and antinatalists can argue that, in the name of reproductive autonomy, we should be allowed to make our own choices about having or not having children; and that we should possibly also be helped to achieve what we have chosen. The help in question covers many practices like the availability of contraception, terminations of pregnancies, fertility treatments, and assisted reproduction. Due to the normative openness of the principle, this is, inevitably, a mixed bag with internal contradictions when it comes to support for the various practical solutions.

Conditional and modified antinatalists can initially defend their claim to the antititle by being suspicious of producing more unhappy people into clearly unwelcoming environments; but the requirement of reproductive autonomy on which they rely can easily turn the tables if better lives and better living conditions are on offer. As indicated by the word “conditional”, they can then seamlessly convert into pronatalism and cease to observe the rules that I set for my own antinatalism. This means, if nothing else, that I have to continue my search for a proper niche in Figure 1. In that search, it should be kept in mind that the main advantage all conditional formulations have over many extinctionist ones is that they do not assign us a categorical obligation to wipe out our own species. The majority of people do not seem to take kindly to that idea.

Three Value Bases for Antinatalism and Extinction

The theories of value at the foundation of antinatalist argumentation can be roughly divided into three groups. Anthropocentric views place value on humanity and on abilities and features that distinguish members of homo sapiens from other organisms. Biocentric views stress the value of life, all life without species- or ability-based discrimination. Sentiocentric views identify the capacity to suffer as the most important criterion in our treatment of others.

If the axiology is anthropocentric, abstinence from childbearing can be justified in two main ways. Deontological philosophers like Cabrera can argue that it would be against human dignity to bring new people into an existence of dependency and manipulation. By having children, parents treat them as mere means to their own ends; and this is at odds with our rationality and moral agency. Consequentialist ethicists can point out, as Benatar does, that human lives are bad and that it would be wrong of us to create more of them. Both these approaches condone, and potentially encourage, voluntary human extinction. I will come back to the similarities and differences of “condoning” and “encouraging” after the theories of value have been initially described.

If the axiology is biocentric, producing more people is wrong if or since humans pose a threat to other life forms. With the ongoing mass extinction of species brought on by climate change and other human-induced environmental assaults, the case for less childbearing seems to be a foregone conclusion. How much less and for how long, however, is open to dispute. Conditional antinatalists can attempt to strike a balance between humanity’s survival and reasonable living conditions for other species. They can hold that caring for other life is essential to human flourishing, too, in which case their biocentrism is instrumental and their true value basis anthropocentric. Unconditional antinatalists, in their turn, can stress the intrinsic value of all life. Armed with this conceptual tool, they can argue that homo sapiens should either radically shrink or permanently step aside and leave the rest of the nature alone.

If the axiology is sentiocentric, reproduction is wrong because it creates more beings who can suffer and inflict suffering on others. In an attempt to avoid the almost inevitable extinctionist corollary of this view, David Pearce and others have argued that since humans are the only ones who can effectively reduce misery in the world, we have an obligation to live on and assume this agenda.Footnote 39 The chances of that happening either now or in the future are scanty, though. Most sentiocentric antinatalists concede that reducing the number of humans and eventually letting the species go extinct are more realistic alternatives. Many of them also advocate putting an end to nonhuman reproduction in the animal industry, perhaps even in the wild.

Condoning, Encouraging, and the Doctrine of Double Effect

Let me pause for a moment to reflect on the relationship between condoning and encouraging in this context. Antinatalist philosophers do not always come all that clean regarding their commitment (or not) to extinction, human or otherwise.Footnote 40 The idea is so unpopular that many of them avoid the issue and thereby signal that they are not actively promoting the demise of humankind although they reluctantly accept it as an unintended side effect. This line of argument does not necessarily stand up to closer scrutiny, as a brief explication of the underlying doctrine of double effect shows.

According to the doctrine of double effect,Footnote 41 an act that has two outcomes, a good one and a bad one, is permissible if and only if (i) it is in and of itself morally good or at least neutral; (ii) the bad outcome is not directly willed or intended; (iii) the good outcome is not a consequence of the bad outcome; and (iv) the good outcome is proportionate to the bad outcome. I am permitted to rescue people from a burning house even if arms and legs are broken in the operation, because (i) rescuing people is good; (ii) I would avoid doing the damage if I could; (iii) the broken bones do not cause the survival of the rescued; and (iv) saving lives at the cost of inflicting reparable harm is proportionate.

When it comes to antinatalism, however, the applicability of the doctrine can be questioned. For universal abstinence, with the ensuing demise of humankind, to be permissible, all four conditions should be met, but they are not. The first and fourth may pass the test, but the second and third present challenges.

-

(i) For antinatalists of any kind, not having children is in and of itself morally good or at least neutral. Strict pronatalists disagree, but no one asks them in this antinatalist face-saving exercise.

-

(iv) The same applies, in theory, to weighing the outcomes. Antinatalists, especially unconditional ones, should see the compelling importance of eliminating manipulation, harm, and suffering; and they should see the demise of our species as a proportionate price to pay for that. They could, in fact, reach this conclusion more directly by assuming a negative utilitarian moral outlook and simply comparing the extent of the damage involved in the two outcomes. Since getting rid of suffering is a major gain and the demise of humankind only a minor loss, the coast is clear for openly extinctionist antinatalism. Except that this is exactly what colleagues seem to be afraid to say out loud; hence the hiding behind side effect talk and the doctrine of double effect.

-

(ii) This move is not, however, straightforward. For extinction to count as a mere excusable side effect, it has to be something not directly willed or intended by the champions of universal abstinence. According to a standard reading of the doctrine, we do not intend a secondary outcome if we would not miss it or pursue it further in case it is not realized. In my earlier example, this criterion was met. Had limbs miraculously not been broken in the course of my rough heroics, I would have had no wish to break them afterwards. The outcomes are, at least conceptually, distinct. Not so in the case of universal antinatalism and extinction. If our aim is to eliminate the coming to existence of manipulated, harmful, or suffering beings, our work is not done before manipulated, harmful, and suffering beings cease to be born. The outcomes cannot be separated.Footnote 42

-

(iii) I am less confident about the correct interpretation of the third criterion. The doctrine’s application to medical end-of-life decisions is twofold. Physicians are allowed to relieve pain with medication that hastens the patient’s death but not to administer a lethal drug to end the pain. In the first case, pain-relief causes death and this is fine; in the second, induced death causes pain-relief and this is not acceptable. Similarly, we could say in the antinatalism-and-extinction case that it is alright to cause humankind’s demise by stopping reproduction but not to cause the end of reproduction by eliminating the species. This is not necessarily mere terminological trickery.

While the intention clause (ii) already tripped the antinatalists who do not want to be counted as extinctionists, a closer look at the causation clause (iii) reveals a different dimension of their thinking that I am slightly more at ease with personally. This is the dimension of the Big Buttons, but even that comes with some twists and turns.

The Testimony of the Big Buttons

Antinatalist discussion is rife with a variety of doomsday scenarios, encapsulated in thought experiments involving Big Buttons. Pressing the biggest one—often red—usually annihilates the entire world; while pressing the smaller ones—green, yellow, and so on—remove people, sentient beings, or living beings, as specified. Since I have made up my mind about the big one already twenty-five years ago, I take the liberty of defining the buttons for this narrative myself.Footnote 43

By the Big Red Button I mean one that, if pressed, will immediately make one of the following disappear: human life; sentient life; all life; planet Earth; or the universe. In assessing the position of antinatalists who shirk the idea of extinction, it does not necessarily matter what else disappears as long as humankind would be gone. The question, of course, is: Would I press the button?

My take on the matter has for a quarter of a century been as follows. I would probably press the Big Red Button but I cannot tell anyone that I would. I cannot tell lest it sounds like advocacy and encourages people to develop their own practical devices to destroy the planet somehow. That is doomed to go wrong and inflict unnecessary suffering. The thought experiment cannot and should not be extended to real life. If I could stop all suffering just like that, I would like to do so. I cannot, so no real-life implications.

The antinatalists who evoke the doctrine of double effect can say, if pushed, that they would not press the button. A charitable reading of this is that they are talking about the actual world and simply agreeing with me. They may believe, like I do, that people should not be provoked to make a mess of things. Their view on the thought experiment, unlike mine, remains hidden, but on the level of reality we are in agreement. Another button reveals, however, a possible disagreement.

By the Big Blue Button I mean, following Efil Blaise’s lead, one that, if pressed, would remove people’s reproductive ability once and for all.Footnote 44 Since the possibility of rendering humans unable to have offspring is more realistic than the sudden elimination of the species, I can skip the thought experiment aspect and say forthwith that I would not press it. The antinatalists who seek protection from the doctrine of double effect can reach the opposite conclusion. The generation-long delay can make this proposition more acceptable to them than the abrupt solution offered by the Big Red Button. Maybe the prolonged exit would be easier to will and to intend.

For me, favoring the new proposal is a sign of unnecessary hesitation in the face of an inevitable end. The intentional delay provided by the Big Blue Button may make the scenario more palatable but it will also leave space for futile suffering.Footnote 45 I may be wrong and my cautious colleagues might not even prefer Blue to Red, but if they do, our paths depart. The conceptual background of the split can be clarified by a further plunge into the axiologies that support extinctionist antinatalism in its many forms.Footnote 46

Sentiocentric Proportionality

A sentiocentric axiology would streamline considerations on proportionality, especially if combined with the moral theory of negative utilitarianism.Footnote 47 , Footnote 48 The avoidance, reduction, and prevention of suffering would be the only hallmark of commendable action; and the rightness and wrongness of practices and policies could be decided empirically. My own erstwhile view was placed into this category by Richard Ashcroft who in 2009 chronicled my changing positions by writing:

While in 1999 there is an ambiguous note to his suggestion that voluntary extinction be “condoned,” … by 2004 the ambiguity has passed and Häyry is advocating quite explicitly a voluntarily extinctionist position. … In retrospect, his admirably liberal and humane, dare I say Enlightenment, version of utilitarianism of 1994 has now been fully driven out by a Schopenhauerian version of utilitarianism, in which the only reason not to annihilate the human race (and other sentient creatures) is that doing so coercively would create even more anguish, through the violation of autonomy and the frustration of certain basic, if irrational, needs.Footnote 49 , Footnote 50 , Footnote 51 , Footnote 52

This describes my 2004 thinking as accurately as I had been able to express it, but sentiocentric negative utilitarianism in its purest form would have to go further. Annihilating the human race and other sentient creatures coercively would produce anguish, but the amount would be negligible when compared to the alternative: the survival of the species, with innumerable future generations of suffering beings. On purely negative utilitarian grounds, the demise would be justified despite the temporary cost. I have recently elaborated my view further but let me examine the implications of sentiocentrism before I go into that.

In addition to promoting voluntary and involuntary human extinction, sentiocentric negative utilitarianism also supports the elimination of all other life forms. Sentient beings are on the list self-evidently. Nonhuman as well as human beings must be included in the spirit of Jeremy Bentham’s dictum, “the question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”Footnote 53 The inclusion of all life, in its turn, can be justified indirectly. As long as the carbon-based structures we call life exist, the potential of sentience re-emerging remains. In fact, as long as Earth-like planets exist, the threat persists.

These last observations make sentiocentric negative utilitarianism an unlikely candidate for widespread general appeal. While hardened extinctionists may not flinch at the prospects of Carbogeddon and Terrageddon, the majority of people will. To make matters worse, sentiocentric negative utilitarianism seems to teach that we are not only permitted to advance all these extinctions; but that it is our solemn moral duty to do so. Unless the other axiologies on offer generate similarly counterintuitive norms, this one may have to be abandoned or at least refined.

Biocentric Scenarios

Biocentric axiologies and their implications present interpretive challenges. From the viewpoint of extinctionist antinatalism, the most natural reading is the so-called misanthropic argument. Humankind is an impediment to the thriving of other species; its demise is the only reliable way to remove the impediment; therefore, humankind must be made to exit. This argument leaves, however, ambiguities and questions in its trail. The first concerns the natural course of events. If life, as it spontaneously exists in all its forms, is good, why should we interfere with its evolution? The dinosaurs had their go, mammals replaced them, and now humans have their turn. Live and let die. Life goes on. What complaints could proponents of biocentrism have against this?

One answer could be that homo sapiens is such a hegemonic and harmful species that it threatens all other life forms. This is a concern that we hear in ecologically oriented circles but it is a futile concern. We do not have a real-life Big Red Button. In its absence, we have, figuratively speaking, tried climate change and environmental degradation, but life on the planet will survive those in one way or another. Existence may become demanding and horrible, like depicted in doomsday movies, yet life, even human life, prevails. We may one day try to create a world-wide nuclear holocaust—I would not advise it, but we might nonetheless—but to what avail? Cockroaches, if not people, will survive the nuclear winter. Business as usual, biocentrically speaking.

Another answer could be that we value diversity as it now is and that we must therefore remove the destructive force, homo sapiens, from the equation. But what would be so special about the current diversity? It might, of course, be the best one for the survival of humankind, but if we make this appeal, the argument becomes anthropo- rather than biocentric. Also, with the weight given to human survival, the antinatalism of the line of thought seems to evaporate.

Unfazed, some self-identified proponents of biocentric antinatalism, including Patricia MacCormack, can turn to a view that I have called abolitionist vitalism.Footnote 54 All species are equal and humankind must shrink and adjust to accommodate the needs of all. Homo sapiens, as it now is, will disappear and a new, more harmonious kinship between nonhuman and human animals (and machines) will emerge. People do not have children; yet life goes on in a world where hegemonies are abolished and a novel vitality flourishes.

This view, if I have understood it correctly, is both antinatalist and extinctionist in important ways. It takes the French dictionary definition to its limit by reducing purely human birthrates to zero. And it prophesies the demise of homo sapiens as we know it. It does not, like sentiocentric negative utilitarianism, take the extra step of promoting the elimination of other life forms, but then, as a form of biocentrism, it would not. It does, like the human bioimmortality and virtual human continuity approaches, have a science-fiction quality, but considering the topic here, human extinction, that is perhaps to be expected. All in all, it is a feasible narrative for those who believe that the lion can lie down with the lamb—and who are in awe of life.

Anthropocentric Awe

The aspect of awe blurs the boundaries between bio- and anthropocentric views. Albert Schweitzer famously—and Fritz Jahr before him less famously—advocated reverence for life, making biological existence the priority yet allowing human judgment to be the ultimate measure of value.Footnote 55 , Footnote 56 , Footnote 57 Their views can be seen as an extension of Immanuel Kant’s humanity principle: “Act in such a way that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never merely as a means, but always at the same time as an end.”Footnote 58 The logic, employed explicitly at least by Jahr, is to say “life” where Kant said “humanity” (“animality” would also work in animal ethics). The difference aside, I would classify both views as anthropocentric. They are, after all, based on the latter part of Kant’s adage: “Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, …: the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.”Footnote 59

The possible category mix of isms notwithstanding, the widening of the circle beyond homo sapiens is a welcome and radical trend. Some other philosophers, notably Cabrera, have chosen, in this respect, a less radical approach to Kantian antinatalism, arguing that only humankind is a legitimate recipient of immediate moral concern. These philosophers do not advocate cruelty to nonhuman animals, but they do not hold our fellow creatures in awe, either. Sentiocentric antinatalists criticize this ilk of anthropocentrists, of course, insisting that the elimination of suffering is more important than respect for rational agency. For what it is worth, I seem to have a foothold in both camps.

Cabrera argues that people treat their children as mere means by bringing them into an existence that is inevitably manipulated and controlled by the parents. Since this is a violation of the humanity principle, we have a categorical duty not to have children; with the implication that Cabrera need not necessarily take extinction—as a “second effect”—into account at all. In Kant’s infamous example, we are not allowed to tell a lie even if truth-telling would gravely harm others. The harm is regrettable but we are not to blame for it. Similarly, abstinence can be our duty regardless of the consequences. The species may go extinct and that may be unfortunate but it is not our fault.

These considerations confirm that both strictly consequentialist and strictly nonconsequentialist moral theories, sentiocentric negative utilitarianism and anthropocentric Kantianism, can reach the offensive conclusion: that we indeed have an obligation to abstain and cause humankind’s extinction. I would be more cautious about assigning such duties and I have over the years honed a philosophical narrative that justifies my position, at least to me.

Copathy, Dissense, and Just Being Kind

I recognize in myself a moral sense that has two aspects, one for the recognition of similarity and togetherness, the other for the recognition of dissimilarity and boundaries. I call these aspects copathy and dissense. Copathy is a calm sensation or awareness that I am one with all other sentient beings, and that I should not by my actions or choices make their lot worse.Footnote 60 It is a fellow feeling. Dissense is a realization that other living beings have their own life directions and that I should not impose my own ways of thinking and being upon them. It is a reminder to respect limits.Footnote 61

I claim no wider validity for these feelings. They constitute the foundation of my thinking on rational morality, but I do not expect every other person in the world to share them. That would go against the idea of dissense. I am only using this dual moral sense to define what antinatalism means to me, which was the goal set in the beginning of this analysis.

The precept for action and behavior that emanates from copathy and dissense is, I think, simple: “Just be kind!” To put this differently, I should try, to the best of my understanding and ability, to be kind and not to be unkind. It is a balancing act, not a straightforward calculation. I have attempted to express roughly the same duality and fuzziness before, under the epithets “liberal utilitarianism,”Footnote 62 “just better utilitarianism,”Footnote 63 and “conflict-responsive need-based negative utilitarianism,”Footnote 64 but in these more public-morality endeavors I have always been forced to reach the same conclusion: one size does not fit all; commands and prohibitions remain, possibly apart from a few clear-cut cases, open-ended.

Ways of being kind and unkind come in different packages, but I can list some general-level candidates (there can be more):

-

1) It is kind to remove or alleviate suffering.

-

2) It is kind to prevent suffering.

-

3) It is kind to bring joy.

-

4) It is unkind to inflict or increase suffering.

-

5) It is unkind to allow preventable suffering.

-

6) It is unkind to curb joy.

-

7) It is unkind to impose.Footnote 65 , Footnote 66

As said, this is not an aggregative utilitarian model. I have to take into account and balance all types of kindness and unkindness to reach a decision that I can act by and live with without guilt or shame.

As for advocating antinatalism, here are my main considerations so far (by “breeders” I mean voluntary actual and potential reproducers and I have defined “prereproductive stress syndrome” elsewhere):Footnote 67 , Footnote 68

-

1) If prereproductive stress syndrome inflicts suffering on breeders, it is kindest to console them by the rationality of not having children.Footnote 69

-

2) Since reproduction would inflict suffering on the future individuals and their offspring, it is kindest not to bring them into existence.Footnote 70

-

3) Although reproduction may bring joy to breeders, balancing the joy against the suffering inflicted tips the scales in favor of abstinence.Footnote 71

-

4) Since blaming-and-shaming breeders makes them suffer, using it as a tactic is not kind and should be balanced with other factors.Footnote 72

-

5) The unkindness specified in 2 would outweigh 4, but then blaming-and-shaming should change minds, and this is unlikely.Footnote 73

-

6) When breeders celebrate their children, it would be unkind and probably counterproductive to curb their joy.Footnote 74

-

7) It would be unkind to force breeders to abstain. It is unkind to manipulate new beings into accepting the breeders’ morality.Footnote 75

While I recognize gray areas in this balancing act, I can fully and without any self-blame or shame advocate antinatalism.

My Antinatalism and Its Rivals

What kind of antinatalism, though? And how does it fare in comparison with the other identified forms of the creed? Armed with 1–7, I can confirm my own niches in Figures 1 and 2.

I am an anti-pronatalist, or strict antinatalist (Figure 2) and I support (on the Extinction side of Figure 1) stopping human reproduction and animal production, including but not limited to factory farming. I would be pleased to see no more suffering-prone beings created by people. Voluntary human extinction and factory animal extinction would follow from these and I would have no qualms about them. If homo sapiens can find the kindness and the courage to break the cycle of sentience that currently holds the species in its grip, excellent. And even barring that, or if a palatably phased human demise takes its time, liberating factory animals from their suffering would be a welcome advance action. Copathy would motivate these developments.

Abiding by the notion of dissense (and still on the Extinction side of Figure 1), I do not advocate involuntary human or wild animal extinction. I would not mourn the loss of any or all species as such, but I do not want to impose my own will upon a self-conscious collective that wants to live (humans) or groups of self-directing, possibly sentient, beings whose drive for survival is beyond my comprehension (nonhumans in the wild). As a thought experiment, I might press the Big Red Button and justify this to myself (poorly, if I take dissense at its full value)Footnote 76 by the fact that afterwards there would be no one to complain. The Big Red Button does not exist, however, and I would not encourage anyone to try to invent it.

Many conclusions that I have drawn here are, of course, open to counterarguments. I believe, however, that my preceding narrative has justified them to all those who share my premises and intuitions. External critiques, objections based on different values and worldviews, fall outside my present scope.

Moving on (to the nonextinction side of Figure 1), I cannot find any decisive fault in human bioimmortality (a form of transhumanism) with a right-to-die clause as a conceptually plausible form of antinatalism. I would rule out all conditional attempts, virtual human continuation, and the imaginary destructive teleportation as not being antinatal. New individuals would still be born; or at least be brought into existence by technological means. I would reject human bioimmortality without a right-to-die clause on grounds of kindness (my model) and reduction of suffering (sentiocentrism), but cannot, in a purely terminological analysis, deny its antinatalist status.

All in all, the ranking of the candidates for my preferred form of antinatalism is as follows:

The winner is, of course, my own stop-human-and-production-animal reproduction model, based on copathy, dissense, and just being kind. It responds to the need of reducing, and eventually eliminating, suffering; and it respects the difference and self-direction of my fellow human and nonhuman beings.

The equal runners-up are sentiocentric negative utilitarianism and Cabrera’s Kantian approach. The former is a little too trigger-happy for my dissense sensibilities in its wild-life extinction view; and the latter seems to ignore the plight of production animals too lightly to satisfy my feeling of copathy.

Other semifinalists include human bioimmortality with a right-to-die allowance and sentiocentric abolitionist vitalism, both antinatalist to a degree but also both a little too diffuse for my taste of philosophical clarity. Considerable longevity is still but a dream, and kinship with other life and machines is difficult to conceptualize clearly.

The last two are not on my list of favorites but they are close enough to keep an eye on for future developments. The rest of the field are not contenders and can be dismissed from my considerations.

And this concludes my quest here. I know now what my antinatalism means and that I can stand by it. Questions, comments, and criticisms are more than welcome.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported financially by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland—project decision VN/2470/2022 “Justainability.”

Competing interest

The author has no competing interests to declare.